Submitted:

14 June 2024

Posted:

18 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.1.1. Types of Electric Vehicles

- a.

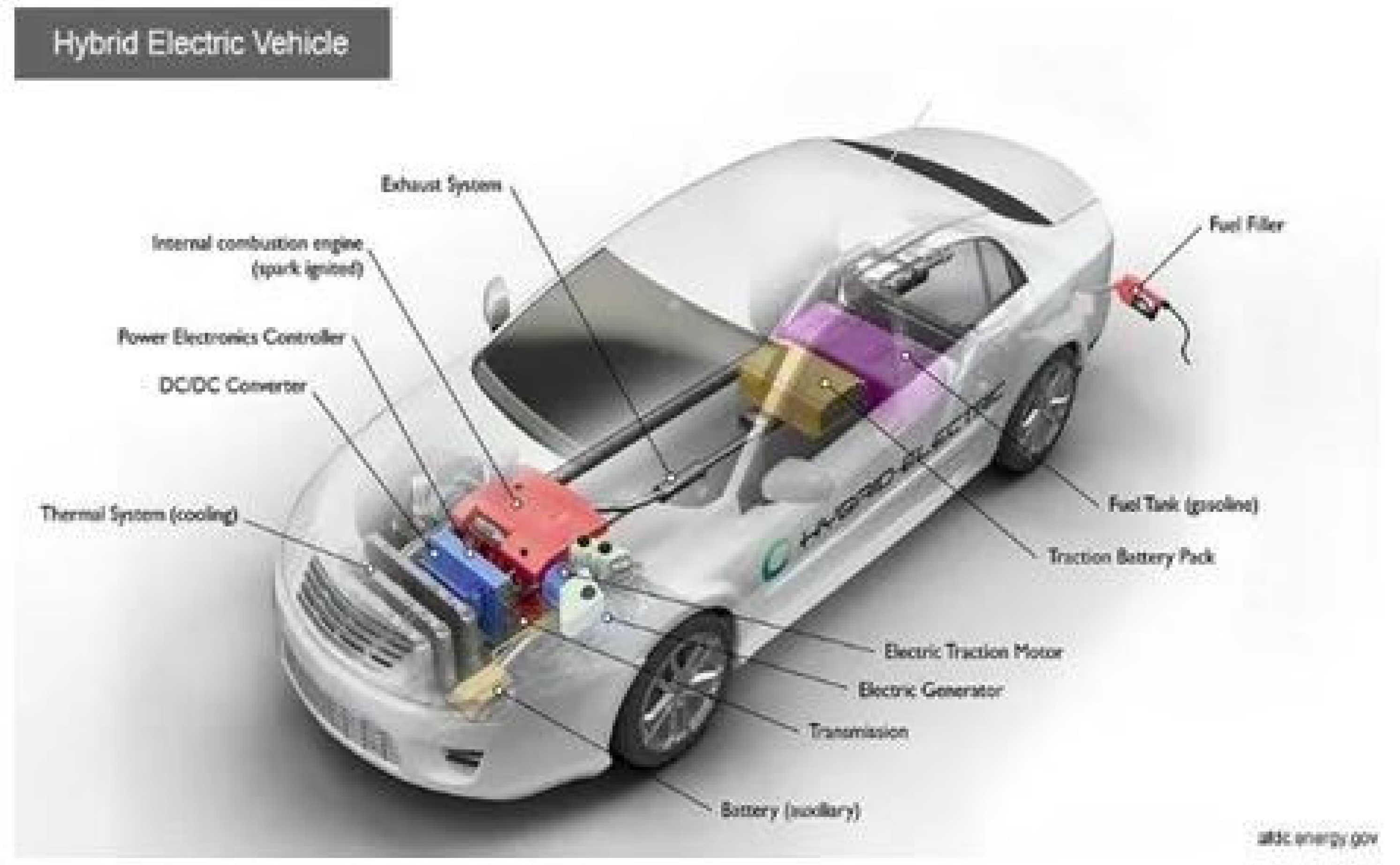

- An engine plus an electric motor make up a hybrid electric vehicle. Here, as seen in Figure 2 below, the engine and the energy produced during braking and deceleration are used to charge the batteries. Within them.

- b.

- As a result of combining an electric motor and a combustion engine as a power converter, these cars are currently known as hybrids. Hybrid electric vehicle technology is widely used because of its many benefits, including providing modern performance without the need for charging reliance on infrastructure. Through the concept of electrification of the powertrain, they can also significantly lower fuel consumption.various HEVa series hybrids, power-split hybrids, and parallel hybrids. The electric motor in a series hybrid is the only source of power for the wheel. Either the generator or the battery provides the motor with power. Here, an IC engine is used to charge the batteries so that an electric motor can run. The computer determines how much power comes from the engine/generator or the battery. The battery pack is energized by both the use of regenerative braking and the engine/generator [2]. Larger battery packs and massive motors paired with small internal combustion engines are typical features of the HEV series. They are supported by ultra-caps, which work to increase the battery’s efficiency and reduce loss.

- i.

- The electric motor’s ideal torque-speed characteristic eliminates the need for several gears.

- i.

- The internal combustion engine and drive wheels can work within their specific, small optimum region thanks to a mechanical decoupling mechanism. Still.

- i.

- As a result of the energy being transferred twice—from mechanical to electrical and back again—the total efficiency will be lowered.

- ii.

- Because it is the only source of torque for a driven wheel, a large traction motor and two electric machines are needed in this situation. Due to their ample area for their big engine/generator combination, these vehicles are frequently employed military vehicles, buses, and commercial vehicles [3].Compared to a series HEV drivetrain, there is less flexibility in the mutual positioning of powertrain components and less energy waste when the engine of a parallel hybrid is directly connected to the wheels. In this case, the engine, the motor, or the combustion of the engine and motor provide the power.

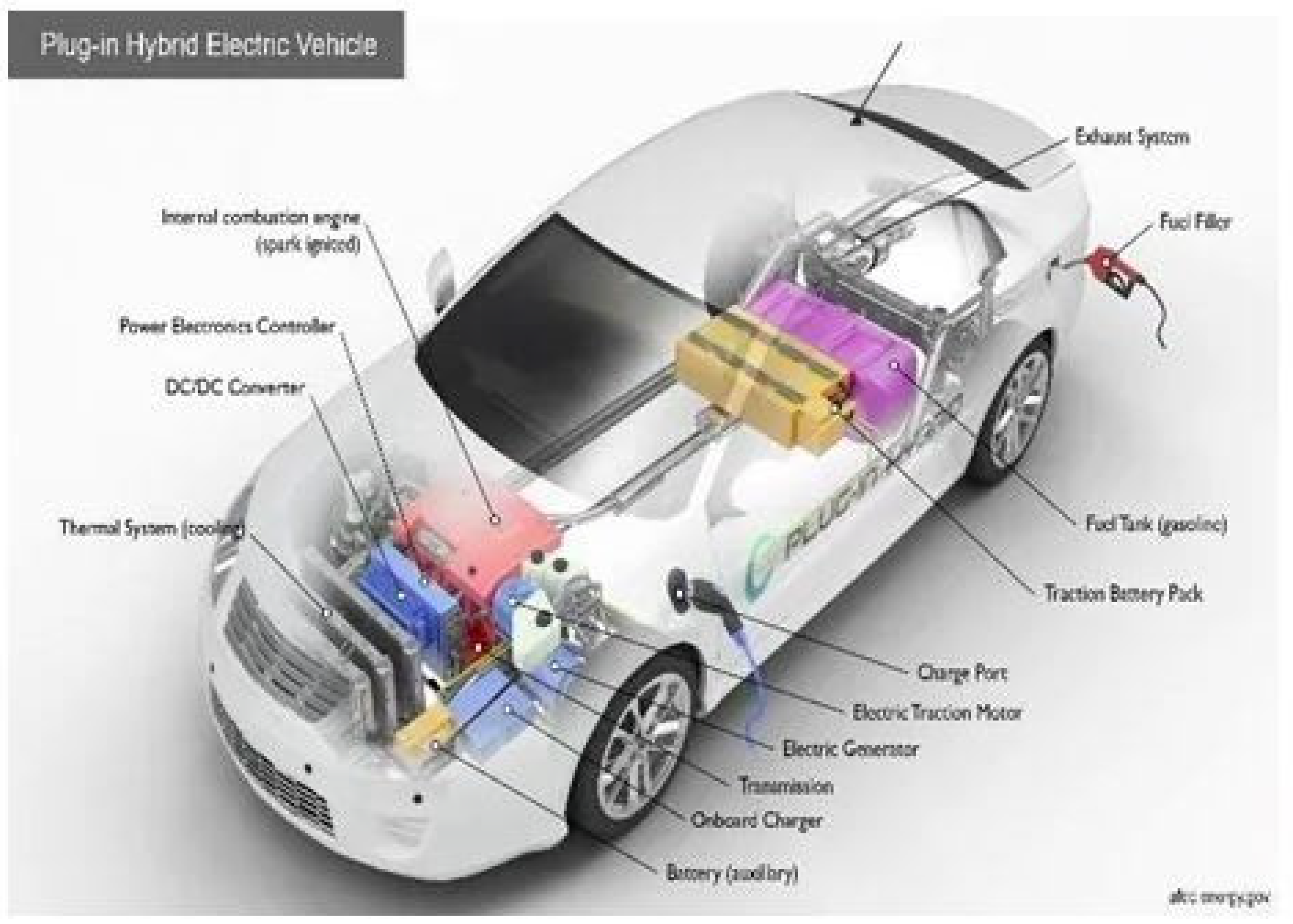

- Plug-in hybrid electric vehicle

- b. Battery electric vehicle

1.2. Hybridisation Factor

2. Objective of the Research

2.1. To Identify the Existing Situation of Electric Electrical Vehicles

2.2. The Problem Concerning the Rise of Electric Vehicle Technology worldwide

- Vehicle servicing

- High capital cost

- Consumer perception.

- Raw materials for batteries

- Battery lifespan/efficiency

2.3. Driving Range of Electric Vehicle

- Safety requirements of electric vehicle

- Charging infrastructure

- Battery recycling

3. Research Scope

4. Methodology

5. Result and Discussion

5.1. Less Petroleum Use

5.2. Recharging Takes Time

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ICEV | Internal Combustion Engine Vehicles |

| HEV | Hybrid Electric Vehicles |

| BEV | Battery Electric Vehicle |

| AEV | All-Electric Vehicles |

| EVs | Electric Vehicles |

| PEVs | Plug-in Electric Vehicles |

| PHEVs | Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles |

| FY | Fiscal Year |

| OEM | Original Equipment Manufacturer |

| MBNOs | Model-Based Non-Linear Observers |

| PMSM | Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor |

| MTTE | Maximum Transmissible Torque Estimation |

| V2G | Vehicle-to-Grid |

| UBIS | User–battery interaction style |

| EDV | Electric Drive Vehicle |

| SOC | State-of-Charge |

| SOF | State-of-Function |

| SOH | State-of-Health |

| DOD | Depth of Discharge |

| NiMh | Nickel Metal Hydride Battery |

| LOLIMOT | Locally Linear Model Tree |

| CP | Convex Programming |

| DP | Dynamic Programming |

| SDP | Stochastic Dynamic Programming |

| TWDPNN | Time weighted dot product based nearest neighbor |

| MPSF | Modified Pattern Sequence Forecasting |

| SVR | Support Vector Regression |

| RF | Random Forest |

| BTMS | Battery Thermal Management System |

| HF | Hybridisation Factor |

References

- M.D. Galus, G. Andersson Demand management of grid connected plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEV) IEEE energy, 2030 (2008), pp. 1–8,.

- R.A. Waraich, M.D. Galus, C. Dobler, M. Balmer, G. Andersson, K.W. Axhausen Plug-in hybrid electric vehicles and smart grids: investigations based on a microsimulation Transp. Res. Part C: Emerg. Technol., 28 (2013), pp. 74–86,.

- X. Yu, T. Shen, G. Li, K. Hikiri Regenerative braking torque estimation and control approaches for a hybrid electric truck Proceedings of the 2010 American Control Conference, IEEE (2010), pp. 5832–5837.

- X. Yu, T. Shen, G. Li, K. Hikiri Model-based drive shaft torque estimation and control of a hybrid electric vehicle in energy regeneration mode Proceedings of the 2009 ICCAS-SICE, IEEE (2009), pp. 3543–3548.

- Y. Zou, H. Shi-jie, L. Dong-ge, G. Wei, X.S. Hu Optimal energy control strategy design for a hybrid electric vehicle Discr. Dyn. Natl. Soc., 2013 (2013), pp. 1–2.

- X.Hu,C.M.Martiez, Y. YangCharging, power management, and battery degradation mitigation in plug-in hybrid electric vehicles: a unified cost-optimal approach Mech. Syst. Signal Process, 87 (2017), pp. 4–16.

- X. Wu, X. Hu, X. Yin, S. MouraStochastic Optimal energy management of Smart home with PEV energy storage IEEE Trans. Smart Grid, 9 (3) (2016), pp. 2065–2075.

- Z. Hu, J. Li, L. Xu, Z. Song, C. Fang, M. Ouyang, et al. Multi-objective energy management optimization and parameter sizing for proton exchange membrane hybrid fuel cell vehicles Energy Convers. Manag., 129 (2016), pp. 108–121.

- S. Bashash, S.J. Moura, J.C. Forman, H.K. Fathy Plug-in hybrid electric vehicle charge pattern optimization for energy cost and battery longevity J. Power Sources, 196 (1) (2011), pp. 541–549.

- S.W. Hadley, A.A. Tsvetkova Potential impacts of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles on regional power generation Electr. J., 22 (10) (2009), pp. 56–68.

- J.C. Kelly, J.S. MacDonald, G.A. Keoleian Time-dependent plug-in hybrid electric vehicle charging based on national driving patterns and demographics Appl. Energy, 94 (2012), pp. 395–405.

- A.K. Srivastava, B. Annabathina, S. Kamalasadan The challenges and policy options for integrating plug-in hybrid electric vehicle into the electric grid Electr. J., 23 (3) (2010), pp. 83–91.

- A.M. Andwari, A. Pesiridis, S. Rajoo, R. Martinez-Botas, V. Esfahanian A review of battery electric vehicle technology and readiness levels Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., 78 (2017), pp. 414–430.

- N.C. Wang, Y. Qin Research on state of charge estimation of batteries used in electric vehicle Proceedings of the Asia-Pac Power Energy Eng Conference (2011).

- N. Watrin, B. Blunier, A. Miraoui Review of adaptive systems for lithium batteries state-charge and state-of-health estimation Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Transportation Electrification Conference and Expo (ITEC), IEEE (2012),.

- W.Y. Chang The state of charge estimating methods for battery: a review ISRN Appl. Math., 2013 (2013).

- J. Zhang, J. Lee A review on prognostics and health monitoring of Li-ion battery J. Power Sources, 196 (15) (2011), pp. 6007–6014.

- S.M. Rezvanizaniani, Z. Liu, Y. Chen, J. Lee Review and recent advances in battery health monitoring and prognostics technologies for electric vehicle (EV) safety and mobilityJ. Power Sources, 256 (2014), pp. 110–124.

- T. Wang, M.J.J. Martinez, O. Sename Hinf observer-based battery fault estimation for HEV application Eng. Powertrain Control Simul. Model., 3 (2012), pp. 206–212.

- H.G. Park, Y.J. Kwon, S.J. Hwang, H.D. Lee, T.S. Kwon A study for the estimation of temperature and thermal life of traction motor for commercial HEV Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Vehicle Power and Propulsion Conference, IEEE (2012), pp. 160–163.

- Ip, S. Fong, E. Liu Optimization for allocating BEV recharging stations in urban areas by using hierarchical clustering Proceedings of the 2010 6th International conference on advanced information management and service (IMS), IEEE (2010), pp. 460–465.

- M.U. Cuma, T. Koroglu A comprehensive review on estimation strategies used in hybrid and battery electric vehicles Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., 42(2015), pp. 517–531.

- S.F. Tie, C.W. Tan A review of energy sources and energy management system in electric vehicles Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., 20 (2013), pp. 82–102.

- M. Peng, L. Liu, C. Jiang A review on the economic dispatch and risk management of the large- scale plug-in electric vehicles (PHEVs)-penetrated power systems Renew. Sustain Energy Rev., 16 (2012), pp. 1508–1515, 10.1016/j.rser.2011.12.009.

- S. Amjad, S. Neelakrishnan, R. Rudramoorthy Review of design considerations and technological challenges for successful development and deployment of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles Renew. Sustain Energy Rev., 14 (2010), pp. 1104–1110. [CrossRef]

- S. Sato, A. Kawamura A new estimation method of state of charge using terminal voltage and internal resistance for lead acid battery Proceedings of the Power Conversion Conference-Osaka 2002 (Cat. №02TH8579), 2, IEEE (2002), pp. 565–570.

- A.R.P. Robat, F.R Salmasi State of charge estimation for batteries in HEV using locally linear model tree (LOLIMOT) Proceedings of the 2007 International Conference on Electrical Machines and Systems (ICEMS), IEEE (2007), pp. 2041–2045.

- F. Pei, K. Zhao,Y. Luo, X. Huang Battery variable current-discharge resistance characteristics and state of charge estimation of electric vehicle Proceedings of the 2006 Sixth World Congress on Intelligent Control and Automation, 2, IEEE (2006), pp. 8314–8318.

- M. Becherif, M.C. Péra, D. Hissel, S. Jemei Estimation of the lead-acid battery initial state of charge with experimental validation Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Vehicle Power and Propulsion Conference, IEEE (2012), pp. 469–473.

- T.W. Wang, M.J. Yang, K.K. Shyu, C.M. Lai Design fuzzy SOC estimation for sealed lead-acid batteries of electric vehicles in Reflex TM Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE International Symposium on Industrial Electronics, IEEE (2007), pp. 95–99.

- W. Chen, W.T. Chen, M. Saif, M.F. Li, H. Wu Simultaneous fault isolation and estimation of lithium-ion batteries via synthesized design of Luenberger and learning observers IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol., 22 (1) (2013), pp. 290–298.

- J. Kim, G.S. Seo, C. Chun, B.H. Cho, S. Lee OCV hysteresis effect-based SOC estimation in extended Kalman filter algorithm for a LiFePO 4/C cell Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Electric Vehicle Conference, IEEE (2012), pp. 1–5.

- P.R. Shukla, S. Dhar, M. Pathak, K. Bhaskar Electric vehicle scenarios and a roadmap for India. Promoting low carbon transport in India Centre on Energy, Climate and Sustainable Development Technical University of Denmark (2014) UNEP DTU Partnership.

- R.J. Bessa, M.A. Matos Economic and technical management of an aggregation agent for electric vehicles: a literature survey Eur. Trans. Electr. Power, 22 (3) (2012), pp. 334–350.

- N. Daina, A. Sivakumar, J.W. Polak Modelling electric vehicles use: a survey on the methods Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., 68 (2017), pp. 447–460.

- F. Koyanagi, Y. Uriu Modeling power consumption by electric vehicles and its impact on power demand Electr. Eng. Jpn., 120 (4) (1997), pp. 40–47.

- J.E. Kang, W.W. Recker An activity-based assessment of the potential impacts of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles on energy and emissions using 1-day travel dataTransp. Res. Part D: Transp. Environ., 14 (8) (2009), pp. 541–556.

- J. Dong, C. Liu, Z. Lin Charging infrastructure planning for promoting battery electric vehicles: an activity-based approach using multiday travel data Transp. Res. Part C: Emerg. Technol., 38 (2014), pp. 44–55.

- C. Weiller Plug-in hybrid electric vehicle impacts on hourly electricity demand in the United States Energy Policy, 39 (6) (2011), pp. 3766–3778 Proceedings of the 2010 American Control Conference, IEEE (2010), pp. 5832–5837.

- J. Axsen, K.S. Kurani Anticipating plug-in hybrid vehicle energy impacts in California: constructing consumer-informed recharge profiles Transp. Res. Part D: Transp. Environ., 15 (4) (2010), pp. 212–219.

- Sundström, C. Binding Charging service elements for an electric vehicle charging service provider Proceedings of the Power and Energy Society General Meeting, 2011, IEEEIEEE (2011), pp. 1–6.

- M.D. Galus, M.G. Vayá, T. Krause, G. Andersson The role of electric vehicles in smart grids Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Energy Environ., 2 (4) (2013), pp. 384–400.

- J. Brady, M O’Mahony Modelling charging profiles of electric vehicles based on real-world electric vehicle charging data Sustain. Cities Soc., 26 (2016), pp. 203–216.

- P. Morrissey, P. Weldon, M. O Mahony Future standard and fast charging infrastructure planning: an analysis of electric vehicle charging behavior Energy Policy, 89 (2016), pp. 257–270.

- Foley, B. Tyther, P. Calnan, B.O. Gallachoir Impacts of electric vehicle charging under electricity market operations Appl. Energy, 101 (2013), pp. 93–102. v.

- R.T. Doucette, M.D. McCulloch Modeling the prospects of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles to reduce CO2 emissions Appl. Energy, 88 (2011), pp. 2315–2323.

- Y. Hai, T. Finn, M. Ryan Driving pattern identification for EV range estimation Proceedings of the IEEE International Electric Vehicle Conference (IEVC) (2012), pp. 1–7.

- G. Hayes John, R.P.R. Oliveira de, V. Sean, G Egan Michael Simplified electric vehicle power train models and range estimation Proceedings of the IEEE Vehicle Power and Propulsion Conference (VPPC) (2011), pp. 1–5.

- F. Salah, J.P. Ilg, C.M. Flath, H. Basse, C. Van Dinther Impact of electric vehicles on distribution substations: a Swiss case study Appl. Energy, 137 (2015), pp. 88–96.

- N. Hartmann, E.D. Ozdemir Impact of different utilization scenarios of electric vehicles on the German grid in 2030 J. Power Sources, 196 (4) (2011), pp. 2311–2318.

- F. Yang, Y. Sun, T. Shen Nonlinear torque estimation for vehicular electrical machines and its application in engine speed control Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE International Conference on Control Applications, IEEE (2007), pp. 1382–1387.

- X. Yu, T. Shen, G. Li, K. Hikiri Regenerative braking torque estimation and control approaches for a hybrid electric truck A comprehensive review on estimation strategies used in hybrid and battery electric vehicles Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., 42 (2015), pp. 517–531.

- X. Yu, T. Shen, G. Li, K. Hikiri Model-based drive shaft torque estimation and control of a hybrid electric vehicle in energy regeneration mode Proceedings of the 2009 ICCAS-SICE, IEEE (2009), pp. 3543–3548.

- X. Yu, T. Shen, G. Li, K. Hikiri Model-based drive shaft torque estimation and control of a hybrid electric vehicle in energy regeneration mode Proceedings of the 2009 ICCAS-SICE, IEEE (2009), pp. 3543–3548.

- D. Yin, Y. Hori A novel traction control of EV based on maximum effective torque estimation Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE Vehicle Power and Propulsion Conference, IEEE (2008), pp. 1–6.

- D. Yin, Y. Hori A new approach to traction control of EV based on maximum effective torque estimation Proceedings of the 2008 34th Annual Conference of IEEE Industrial Electronics, IEEE (2008), pp. 2764–2769.

- D. Yin, S. Oh, Y. Hori A novel traction control for EV based on maximum transmissible torque estimation Proceedings of the IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electron (2009).

- L. Lu, X. Han, J. Li, J. Hua, M. Ouyang A review on the key issues for lithium-ion battery management in electric vehicles J. Power Sources, 226 (2013), pp. 272–288 ics, 56(6), 2086–2094.

- Panday, H.O. Bansal A review of optimal energy management strategies for hybrid electric vehicle Int. J. Veh. Technol., 2014 (2014), pp. 1–19.

- Y. Yong, V.K. Ramachandaramurthy, K.M. Tan, N. Mithulananthan A review on the state-of-the-art technologies of electric vehicle, its impacts and prosp,ects Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., 49 (2015), pp. 365–385.

- D.B. Richardson Electric vehicles and the electric grid: a review of modeling approaches, Impacts, and renewable energy integration Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., 19 (2013), pp. 247–254.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).