Submitted:

17 June 2024

Posted:

18 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The H

3. The Red and Blue Flares Cannot Be Glimpses of the Accretion Disk

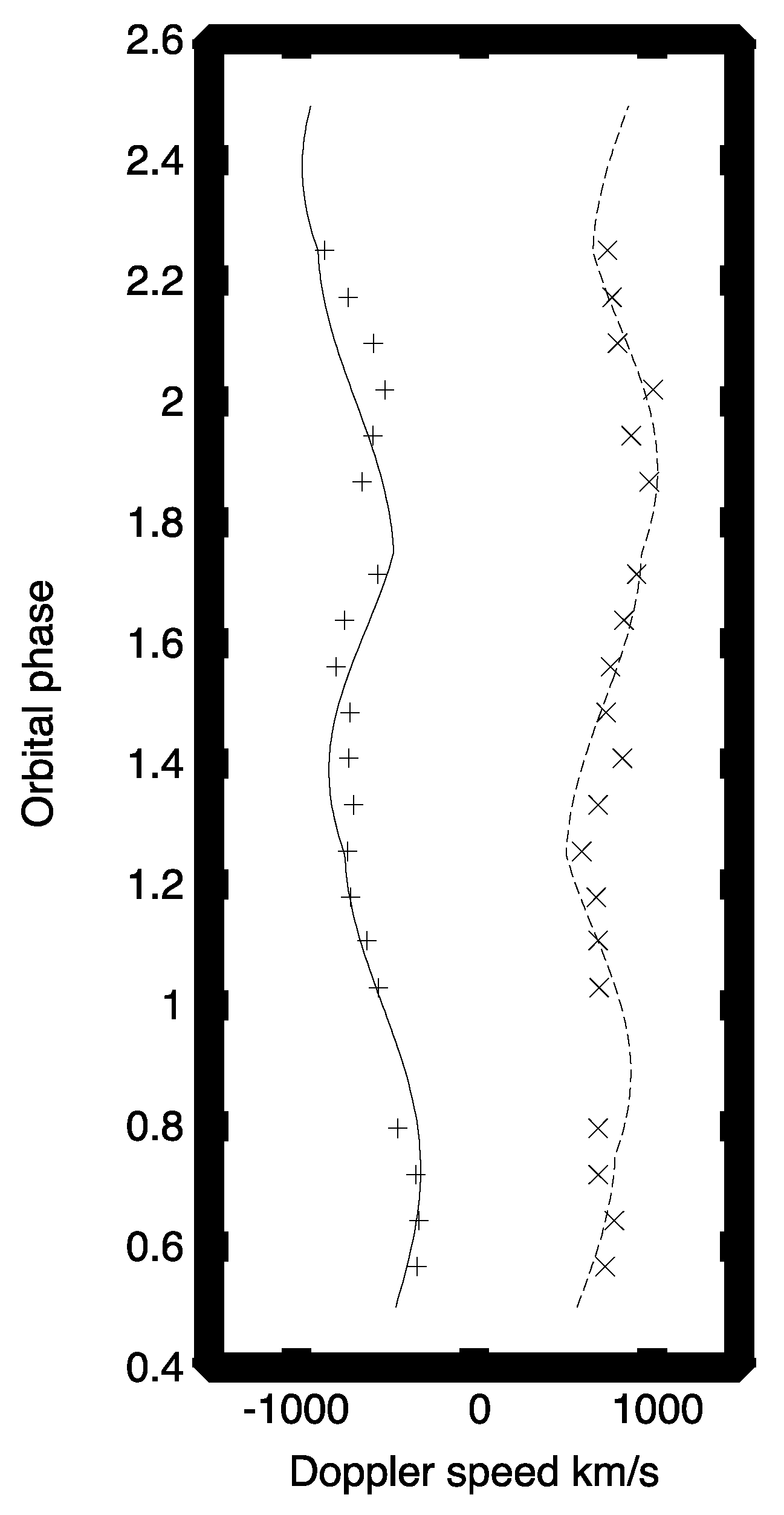

4. Qualitative Analysis of Figure 1

5. Quantitative Analysis

6. Relation to Other Calculations

7. Conclusions

References

- Olivera-Nieto, L. et al. Acceleration and transport of relativistic electrons in the jets of the microquasar SS 433. Science. 2024, 383, 402-406 (HESS). [CrossRef]

- Bowler, M. G. & Keppens, R. W50 and SS 433. A&A. 2018, 617, A 29 1-7.

- Bowler, M. G. W50 morphology and the dynamics of SS 433 formation. arXiv:2008.10042v2, 2024 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Blundell, K. M. et al. SS433’s accretion disc, wind and jets: before, during and after a major flare. MNRAS. 2011, 417, 2401-2410.

- Schmidtobreick, L. & Blundell, K. M. The emission distribution in SS433. PoS 2006 (MQW6) 094 ,1-5.

- Bowler, M. G. SS 433: the accretion disk revealed in Hα. A&A 2010 516, A24 1-6.

- Bowler, M. G. SS 433 Optical Flares: A New Analysis Reveals Their Origin in Overflow Episodes. Galaxies 2021 9, 46 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Waisberg, I. et al. Super-Keplerian equatorial outflows in SS 433. A&A. 2019, 623, A47 1–13 (GRAVITY). [CrossRef]

- Bowler, M. G. Interpretation of observations of the circumbinary disk of SS 433. A&A. 2010, 521, A81 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Bowler, M. G. SS 433: Two robust determinations fix the mass ratio. A&A. 2018, 619, L4 1-4. [CrossRef]

- Fabrika , S. N. An extended disc around SS 433. MNRAS. 1993, 261, 241-245.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).