Submitted:

14 June 2024

Posted:

14 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

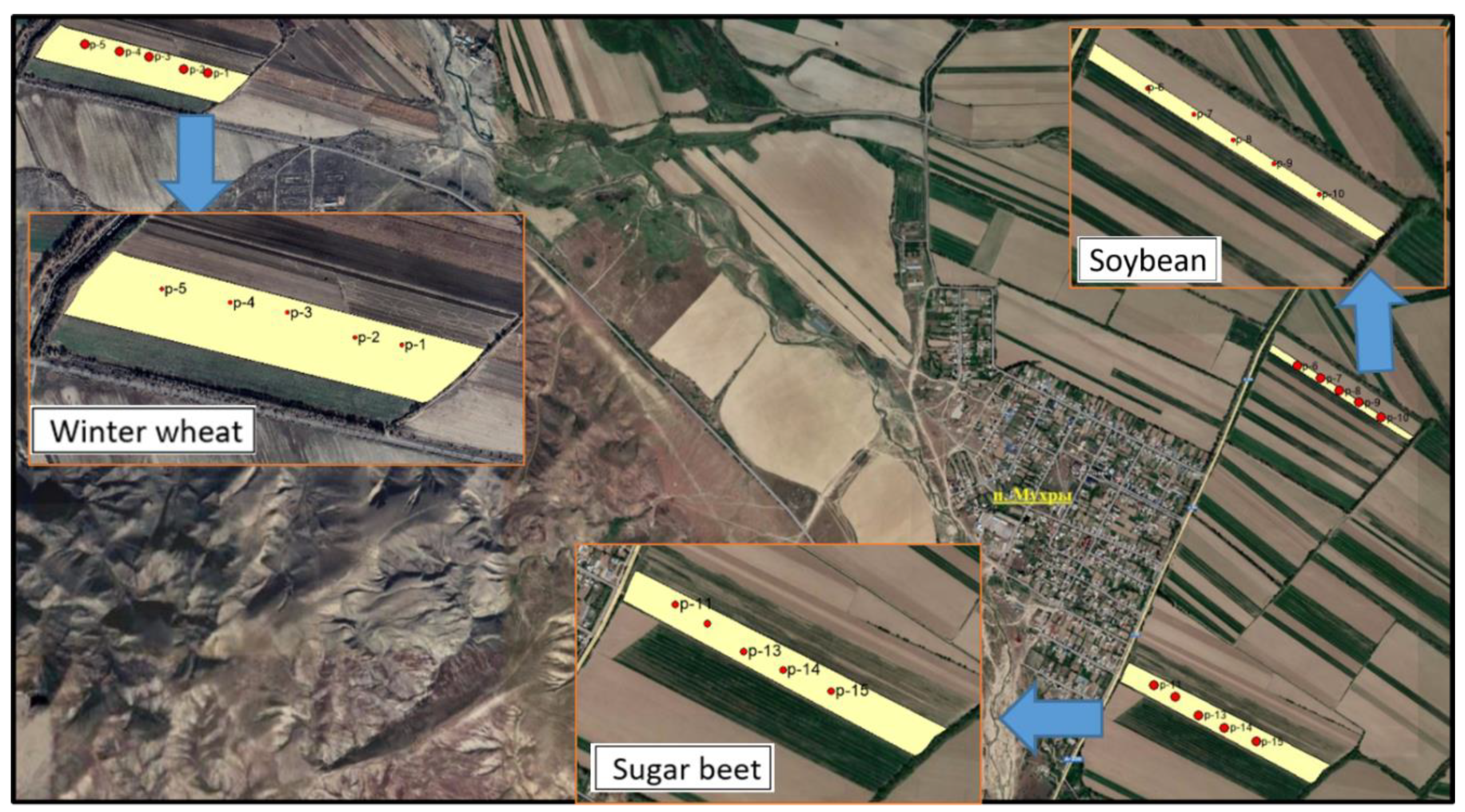

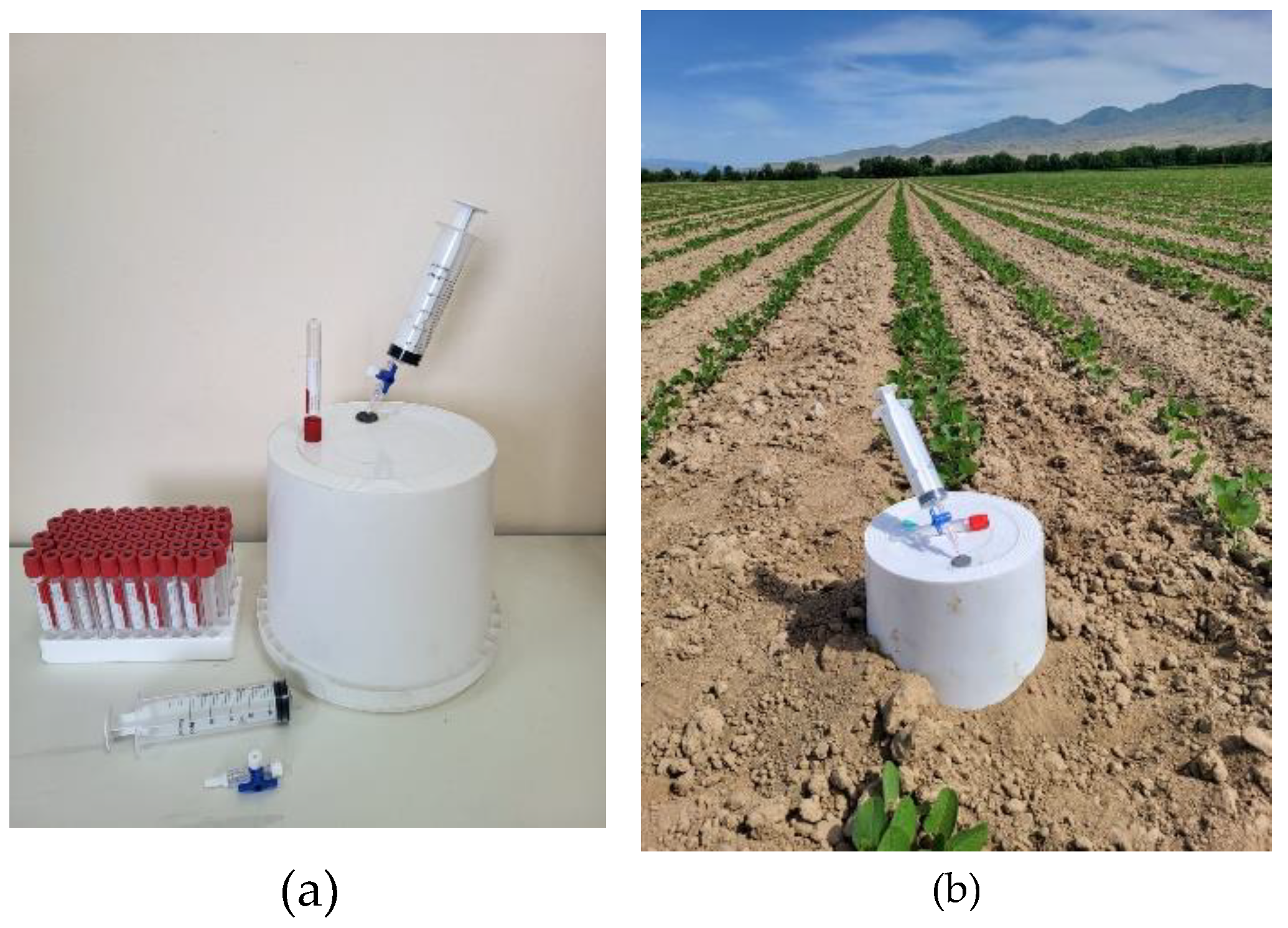

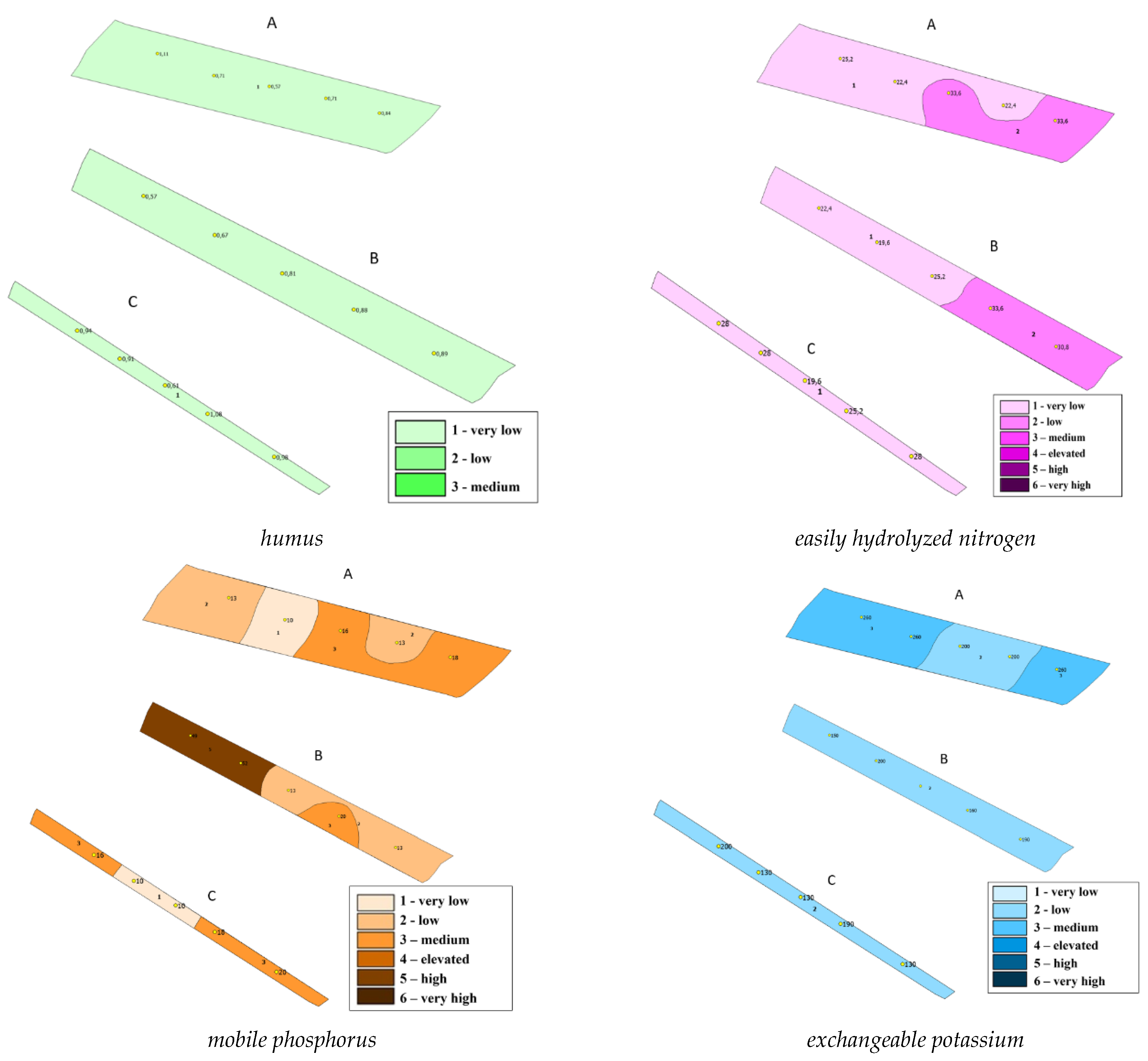

2. Materials and Methods

Research Methods

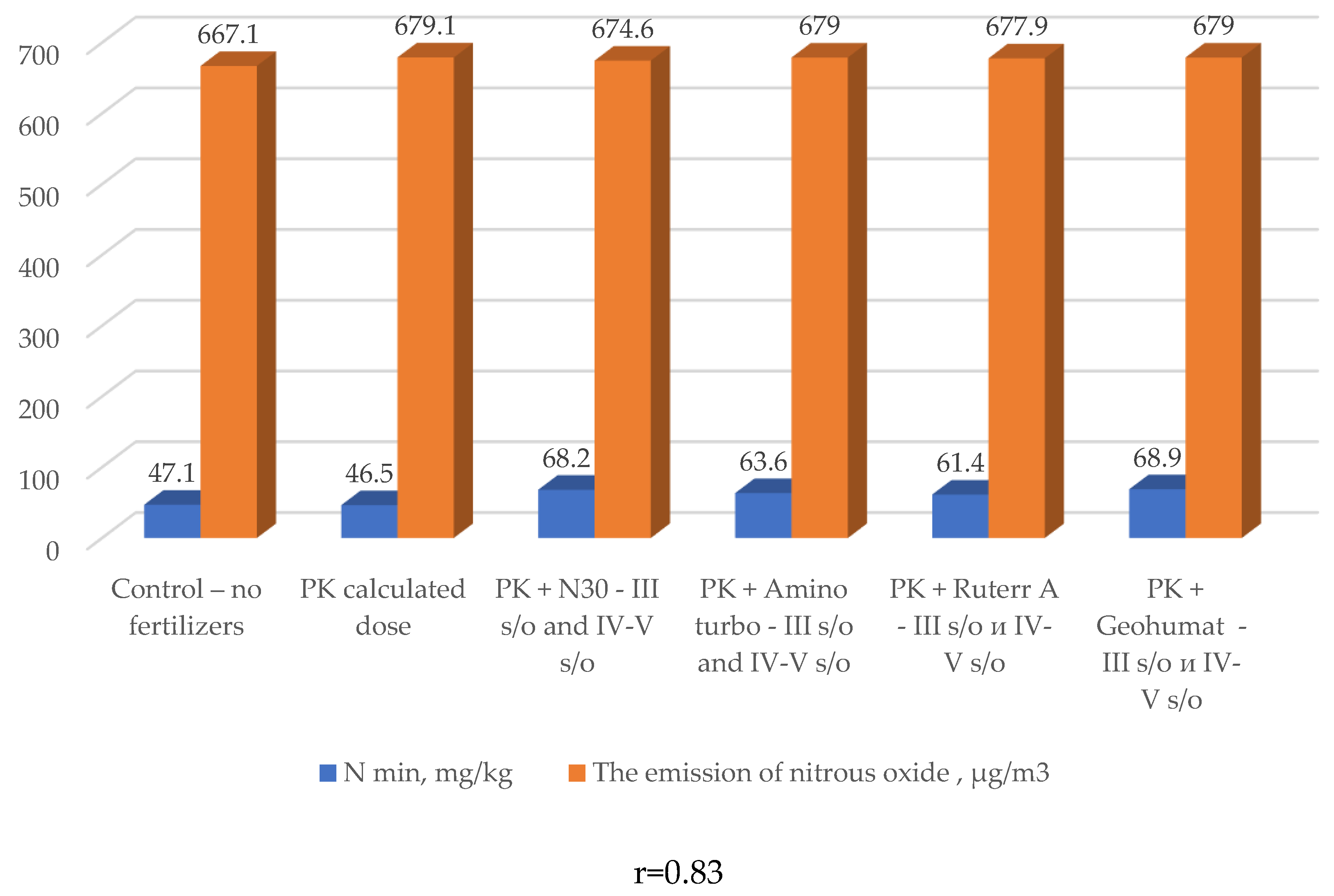

3. Results and discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ali, NA.; Elshiekh, OM.; Sidahmed, OA.; Badreldin, AM. Influence of the nitrogen form on soil nitrate and nitrite and nitrate reductase-activity of cotton grown under Sudan Gezira conditions. Agrochimica 1992, 36, 406–412. [Google Scholar]

- Ermohin, YU.İ. <italic>Optimizatsiya mineralnogo pitaniya selskohozyaistvennyh kultur</italic>. FGOU VPO «OmGAU»: Omsk, Russia, 2005; 284.

- Xing, Y.; Jiang, W.; He, X.; Fiaz, S.; Ahmad, S.; Lei, X.; Wang, X. A review of nitrogen translocation and nitrogen-use efficiency. J Plant Nutr 2019, 42, 2624–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, N.Q.; Lin, H.X. Higher yield with less nitrogen fertilizer. Nat. Plants 2020, 6, 1078–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Jardin, P. The Science of Plant Biostimulants–A bibliographic analysis, Ad hoc study report, 2012.

- Halpern, M.; Bar-Tal, A.; Ofek, M.; Minz, D.; Muller, T.; Yermiyahu, U. The Use of Biostimulants for Enhancing Nutrient Uptake. In <italic>Advances in agronomy</italic>, Donald L. Sparks, Academic Press: Newark, United States 2015; 130, 141-174. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.H.; Wang, M.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, S.X.; Zhang, Y.L.; Wang, X.D. Effect of composted manure plus chemical fertilizer application on aridity response and productivity of apple trees on the loess plateau, China. Arid. Land Res. Manag. 2017, 31, 388–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikorska, A.; Gugała, M.; Zarzecka, K. The impact of different types of foliar feeding on the architecture elements of a winter rape (Brassica Napus L.) field. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res, 2020, 18, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, R.H.; Jat, G.; Jain, D. ; Impact of foliar application of different nano-fertilizers on soil microbial properties and yield of Wheat. J. Environ. Biol., 2021, 42, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, P.; Dong, X.; Lu, L.; Fang, M.; Ma, Z.; Du, J.; Dong, Z. Wheat yield and nitrogen use efficiency enhancement through poly (aspartic acid)-coated urea in clay loam soil based on a 5-year field trial. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 953728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bărdaş, M.; Rusu, T.; Russu, F.; Șimon, A.; Chețan, F.; Ceclan, O.A.; Rezi, R.; Popa, A.; Cărbunar, M.M. The Impact of Foliar Fertilization on the Physiological Parameters, Yield, and Quality Indices of the Soybean Crop. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrea, A.; Rezi, R.; Urda, C.; Pacurar, L.; Teodor, R. Soybean yield and quality response to foliar fertilization. AgroLife Sci J. 2022, 11, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwman, A.; Germon, J. Soil and Global Change (Special Issue) Introduction. Biol. Fert. Soil, 1998, 27, 219–22. [Google Scholar]

- Charles, A.; Rochette, P.; Whalen, J.K.; Angers, D.A.; Chantigny, M.H.; Bertrand, N. Global nitrous oxide emission factors from agricultural soils after addition of organic amendments: A meta-analysis. Agr. Ecosyst. Environ 2017, 236, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuebbles, D.J. Nitrous oxide: no laughing matter. Science 2009, 326, 56–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizhiya, E. Y.; Olenchenko, E. A.; Pavlik, S. V.; Balashov, E. V.; Buchkina, N P. Effect of mineral fertilizers on crop yields and N2O emission from a loamy-sand Spodosol of North Western Russia. Cereal. Res. Commun. 2008, 36, 1299–1302. [Google Scholar]

- Abrol, I.P.; Gupta, R.K.; Malik, R.K. <italic>Conservation Agriculture. Status and Prospects</italic>. Centre for Advancement of Sustainable Agriculture: New Delhi, India, 2009; 242.

- Alluvione, F.; Bertora, C.; Zavattaro, L. ; Grignani, C Nitrous oxide and carbon dioxide emissions following green manure and compost fertilization in corn. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2010, 74, 384–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, RC; Bremer, DJ. Nitrous oxide emissions in turfgrass systems: a review. Agron. J. 2018, 110, 2222–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.; Marschner, P. Soil respiration, microbial biomass C and N availability in a sandy soil amended with clay and residue mixtures. Pedosphere 2016, 64, 3–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakoor, A.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Chen, N.; He, F.; Zuo, H.; Yin, H.; Yan, X.; Ma, Y.; Yang, S. Effects of fertilizer application schemes and soil environmental factors on nitrous oxide emission fluxes in a rice-wheat cropping system, east China. Plos One 2018, 13, 0202016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Liu, G.; Jing, M.; Hua, X.; Yagi, K. Effect of controlled-release fertilizer on nitrous oxide emission from a winter wheat field. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosys. 2012, 94, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudeyarov, V. N. ; Nitrous oxide emission from soils under conditions of fertiliser application. Soil Science 2020, 10, 1192–1205. [Google Scholar]

- Velthof, G.L.; Oenema, O. Nitrous oxide fluxes from grassland in the Netherlands: I. Statistical analysis of flux-chamber measurements. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 1995, 46, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, N.C.; Weil, R.R. <italic>The Nature and Properties of Soils</italic>, 14th edition. Pearson Publishing Int.: London, UK, 2008.

- FAO Stat. Available online: http://faostat.fao.org/static/syb/ syb_5000.pdf 32 (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- Shapoval, O.A.; Mozharova, I.P.; Ponomareva, A.S. Effectiveness of polyfunctional fertilizers with the inclusion of amino acids on grain crops. Fertility 2018, 5, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabadi, D.; Aguero, M. S.; Perez-Amador, M. A.; Carbonell, J. Arginase, Arginine Decarboxylase, Ornithine Decarboxylase, and Polyamines in Tomato Ovaries (Changes in Unpollinated Ovaries and Parthenocarpic Fruits Induced by Auxin or Gibberellin). Plant Physiol. 1996, 112, 1237–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forde, B.G. Lea, P. J. Glutamate in plants: metabolism, regulation, and signalling. J. Exper. Bot. 2007, 58, 2339–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Rogers, L. M.; Song, Y.; Guo, W.; Kolattukudy, P. E. Homoserine and asparagine are host signals that trigger in planta expression of a pathogenesis gene in Nectria haematococca. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 4197–4202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, G.A.; Jander, G. Plant Immunity to Insect. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2008, 59, 41–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, S.; Lin, Y.; Ye, G.; Fan, J.; Hu, H.W.; Jin, Sh.; Duan, Ch.; Zheng, Y.; He, J.Z. Long-term manure amendment reduces nitrous oxide emissions through decreasing the abundance ratio of amoA and nosZ genes in an Ultisol. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2023, 184, 104771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Ding, B.; Pei, Sh.; Cao, H.; Liang, J.; Li, Zh. The impact of organic fertilizer replacement on greenhouse gas emissions and its influencing factors. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 905, 166917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akiyama, H.; Tsuruta, H. Nitrous Oxide, Nitric Oxide, and Nitrogen Dioxide Fluxes from Soils after Manure and Urea Application. J. Environ. Qual. 2003, 32, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Ding, J. Xu, Ch. Zheng, Q. Zhuang, Sh. Mao, L. Li, Q. Liu, X. Li Y. Evaluation of N2O sources after fertilizers application in vegetable soil by dual isotopocule plots approach. Environ. Res. 2020, 188, 109818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, A.; Rochette, P.; Whalen, J. K.; Angers, D.A.; Chantigny, M.H.; Bertrand, N. Global nitrous oxide emission factors from agricultural soils after addition of organic amendments: A meta-analysis. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2017, 236+, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebed, L.V.; Eserkepova, I.B.; Iorgansky, A.I.; Koshen, B.M.; Ramazanova, S.B.; Shchareva, E. Dinamika panikovyh gazov dlya pahotnyh ugodii v Kazahstane. Pochvovedenie Agrohim. 2015, 1, 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kunanbaev, K.K. Emissiya zakisi azota v Severnom Kazahstane na 4-polnyh sevooborotah. Realizatsiya metodologicheskih i metodicheskih idei professora B.A. Dospehova v soverşenstvovanii adaptivno-landşaftnyh sistem zemledeliya. Moscow-Suzdal, Russian Federation, 26-29 June 2017.

- Kussainova, M. , Toishimanov, M., Iskakova, G., Nurgali, N., Chen, J. Effects of different fertilization practices on CH4 and N2O emissions in various crop cultivation systems: A case study in Kazakhstan. Eur. J. Soil. Sci. 2023, 12, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchkina, N.P.; Balaşov, E.V.; Rijiya, E.Ya.; Pavlik, S.V<italic>. Metodicheskie rekomendatsii monitoring emissii zakisi azota iz selskohozyaistvennyh pochv</italic>. Sankt-Peterburg, Russian Federation, 2008; 17.

- Manual on measurement of methane and nitrous oxide emissions from agriculture. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), Available online:. Available online: https://inis.iaea.org/collection/NCLCollectionStore/_Public/24/019/24019160.pdf. (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- Dospehov, B.A. Metodika polevogo opyta: (s Osnovami Statisticheskoi Obrabotki Rezultatov Issledovanii); Alyans: Moskva, Russia, 2011: 352. Available online: https://search.rsl.ru/ru/record/01005422754 (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- Novoa, R.; Tejeda, H. Evaluation of the N2O emissions from N in plant residues as affected by environmental and management factors. Nutr Cycl Agroecosyst 2006, 75, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, E. A. Fluxes of nitrous oxide and nitric oxide from terrestrial ecosystems. In: <italic>Microbial production and consumption of greenhouse gases: methane, nitrogen oxides, and halomethanes</italic>, Rogers, J. E., Whitman, W. B. Eds., American Society for Microbiology: Washington, USA, 1991; 219–235.

- Grankova A.U., Stepanov A.L., Umarov M.M. Enzyme activity of carbon and nitrogen microbial cycles during the self-regeneration of agroecosystems. Proceeding, Enzymes in the Environment, Activity, Ecology and Applications, Granada, Spain, July 12- 15,1999.

- Stepanov, A.L. Mikrobnaya transformatsiya zakisi azota v pochvah: Avtoref Diss. PhD Thesis, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mladenova, Y.I.; Rotcheva, S.; Vinarova, K. Changes of growth and metabolism of maize seedlings under NaCl stress and interfering effect of Siapton leaf organic fertilizer on the stress responses. In: 20th Ann. ESNA Meeting, Lunteren 1989, (NL), Oct. (poster).

- Islam, M.M.; Hassan, M.U.; Ishfaq, M.; Farhana, A.R.; Nadeem, F.; Ahmad, Z.; Xu, J.; Ning, P.; Li, X. Foliar Glutamine Application Improves Grain Yield and Nutritional Quality of Field-Grown Maize (Zea mays L.) Hybrid ZD958. J Plant Growth Regul. 2024, 43, 624–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marhoon, I.; Kadhim, M. Effect of Foliar Application of Seaweed Extract and Amino Acids on Some Vegetative and Anatomical Characters of Two Sweet Pepper (Capsicum Annuum L. ) Cultivars. IJRSAS 2015, 1, 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bezuglova, O.S.; Gorovtsov, A.V.; Polienko, E.A.; Zinchenko, V.E.; Grinko, A.V.; Lykhman, V.A.; Dubinina, N.M.; Demidov, A. Effect of humic preparation on winter wheat productivity and rhizosphere microbial community under herbicide-induced stress. J Soils Sediments 2019, 19, 2665–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitriatin, B.N.; Febriani, S.; Yuniarti, A. Application of biofertilizers to increase upland rice growth, soil nitrogen and fertilizer use efficiency. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Bogor, Indonesia, 16-. 18 September. [CrossRef]

- Korotkova, I.; Marenych, М.; Hanhur, V;, Laslo, О.; Chetveryk, О.; Liashenko, V. Weed Control and Winter Wheat Crop Yield With the Application of Herbicides, Nitrogen Fertilizers, and Their Mixtures With Humic Growth Regulators. Acta Agrobot. 2021, 74, 748. [CrossRef]

- Sedri, M.H.; Roohi, E.; Niazian, M.; Niedbała, G. Interactive Effects of Nitrogen and Potassium Fertilizers on Quantitative-Qualitative Traits and Drought Tolerance Indices of Rainfed Wheat Cultivar. Agronomy 2022, 12, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozek, O.; Fecenko, J.; Mazur, B.; Mazur, K. The effect of foliar application of humate on wheat grain yield and quality. Rostlinna Vyroba 1997, 43, 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Bărdaş, M.; Rusu, T.; Popa, A.; Russu, F.; Șimon, A.; Chețan, F.; Racz, I.; Popescu, S.; Topan, C. Effect of Foliar Fertilization on the Physiological Parameters, Yield and Quality Indices of the Winter Wheat. Agronomy 2024, 14, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latifinia, E.; Eisvand, H.R. Soybean Physiological Properties and Grain Quality Responses to Nutrients, and Predicting Nutrient Deficiency Using Chlorophyll Fluorescence. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2022, 22, 1942–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhar, S.; ul Haq, M.A.; Akhtar, J.; Waraich, E.A. Nitrogen Nutrition Effects on Growth, Protein and Oil Quality in Soybean (Glycine max) Genotypes under Saline Conditions. Int. J. Agric 2020, 24, 1715–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirova, E. Effect of nitrogen nutrition source on antioxidant defense system of soybean plants subjected to salt stress. Comp. Rend. Academ. Bulg. Sci. 2020, (2), 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Cordeiro, C. F.; Lopes, B. P.; Batista, G. D.; Araujo, F. F.; Tiritan, C. S.; Echer, F. R. Inoculation and Nitrogen Fertilization Improve Nitrogen Soil Stock and Nutrition to Soybeans in Degraded Pastures with Sandy Soil. Comm. Soil Sci. Plant Analy. 2021, 52, 1388–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, B.; Zhou, W.; Zhong, X.; Fu, C.; Cao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, X. Effect of nitrogen application levels on photosynthetic nitrogen distribution and use efficiency in soybean seedling leaves. J. Plant Physiol. 2023, 287, 154051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jong Hyuk, K.; Kang, C.K.; Rho, I.R. ; Growth and yield responses ofsoybean according to subsurface fertigation. Agronomy J. 2023, 115, 1877–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, F.C.; Camargo, de R; Lana, R.M.Q.; Franco, M.H.R.; Stanger, M.C.; Pereir, V.J. Azospirillum brasilense and organomineral fertilizer co-inoculated with Bradyrhizobium japonicumon oxidative stress in soybean. Inter. J. Recycl. Organ. Waste Agricul. 2022, 11, 229–245. [CrossRef]

- Zaitseva, N.N.; Fadeeva, N.A.; Vasilev, O.A. İspolzovanie bioudobrenii v kormoproizvodstve. Nauchno-obrazovatelnye i prikladnye aspekty proizvodstva i pererabotki selskohozyaistvennoi pro-duktsii. Cheboksary, Russia, 15 november 2018. pp. 59–69.

- Borges, W.L.; Garcia, J.P.; Oliveira Junior, A.; Teixeira, P.C.; Polidoro, J.C. Agronomic efficiency of fertilizers with aggregate technology in the Brazilian Eastern Amazon. Rev. Brasil. Ciênc. Agrár. 2023, 18, 2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, A.; Liu, D. Effect of Phosphorus Supply Levels on Nodule Nitrogen Fixation and Nitrogen Accumulation in Soybean (Glycine max L.). Agronomy 2022, 12, 2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzanov, İ.F. Sposoby povyşeniya saharistosti saharnoi svёkly. Sahar. Promyşl. 1952, 6, 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Orlovskii, N.İ. <italic>Biologiya i selektsiya saharnoi sv</italic><italic>ё</italic><italic>kly</italic>. Kolos: Moscow, Russia, 1968; 481.

- Zubenko, V.F. <italic>Saharnaya sv</italic><italic>ё</italic><italic>kla. Osnovy agrotehniki</italic>. Urojai: Kiev, Ukraine, 1979; 416.

- Pacuta, V.; Cerny, I.; Pulkrábek, J. Influence of Variety and Foliar Preparations Containing Bioactive Substances on Root Yield, Sugar Content and Polarized Sugar Yield of Sugar Beet. Listy cukrovarn. reparske 2013, 129, 337–340. [Google Scholar]

- Pytlarz-Kozicka, M. The effect of nitrogen fertilization and anti-fungal plant protection on sugar beet yielding. Plant Soil Environ. 2005, 51, 232–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Sui, N.; Ding, T.; Zhang, X.; Song, J.; Wang, B. Effects of Salinity and Nitrate Nitrogen on Growth, Ion Accumulation, and Photosynthesis of Sugar Beet. <italic>Advan. Environ. Technol</italic>. <bold>2013</bold>, <italic>726-731,</italic> 4371-4380. [CrossRef]

- Minakova, O.A. , Tambovtseva L.V., Aleksandrova L.V. Produktivnost i vynos NRK gibridami saharnoi svekly otechestvennoi i inostrannoi selektsii na razlichnyh fonah osnovnoi udobrennosti. Sahar. svekla 2014, 5, 40–42. [Google Scholar]

- Uvarov, G.İ.; Juravlёva, N.V.; Juravlёv, K.N.; Solovichenko, V.D. Priёmy povyşeniya urojainosti i kachestva korneplodov v Belgorodskoi oblasti. Sahar. Svёkla 2007, 2, 22–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kenenbaev, S.B.; Aldekov, N.A. Kulkeev, E.E. Primenenie biostimulyatorov rosta rastenii na posevah saharnoi svekly, 2017.

- Kuk, Dj.U. <italic>Regulirovanie plodorodiya pochv</italic>. Kolos: Moscow, Russia, 1970; pp. 255–260.

- Kosyakin, P.A.; Borontov, O.K.; Manaenkova, E.N.; Minakova, O.A. Dinamika rosta, potrebleniya elementov pitaniya i urojainost saharnoi svekly v zavisimosti ot udobrenii i obrabotki chernozema vyщelo-chennogo v sevooborote tsentralno-chernozemnogo regiona. Agrohimiya 2019, 7, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, T.M.; Hamze, H.; Golabi Lak, I. Impact of biofertilizers and zinc nanoparticles on enzymatic, bio-chemical, and agronomic properties of sugar beet under different irrigation regimes. Zemdir. Agriculture. 2023, 110, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosaad, I.S.M.; Serag, A.H.I.; Sheta, M.H. Promote sugar beet cultivation in saline soil by applying humic substances in-soil and mineral nitrogen fertilization. J. Plant Nutr. 2022, 45, 2447–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pačuta, V.; Rašovský, M.; Briediková, N.; Lenická, D.; Ducsay, L.; Zapletalová, A. Plant Biostimulants as an Effective Tool for Increasing Physiological Activity and Productivity of Different Sugar Beet Varieties. Agronomy 2024, 14, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| № п/п | Variants | Nl.g. | N-NO3 | N-NH4 | N min, ∑ |

| Winter wheat, sowing 2022 | |||||

| 1 | Control – no fertilizers | 26,1 | 18,8 | 2,2 | 47,1 |

| 2 | PK calculated dose | 28,0 | 16,8 | 1,7 | 46,5 |

| 3 | N30 - III s/o and IV-V s/o | 33,6 | 25,5 | 9,1 | 68,2 |

| 4 | Amino turbo - III s/o and IV-V s/o | 33,7 | 23,3 | 6,6 | 63,6 |

| 5 | Ruter AA - III s/o and IV-V s/o | 34,5 | 20,4 | 6,5 | 61,4 |

| 6 | Geohumat - III s/o and IV-V s/o | 34,5 | 25,3 | 9,1 | 68,9 |

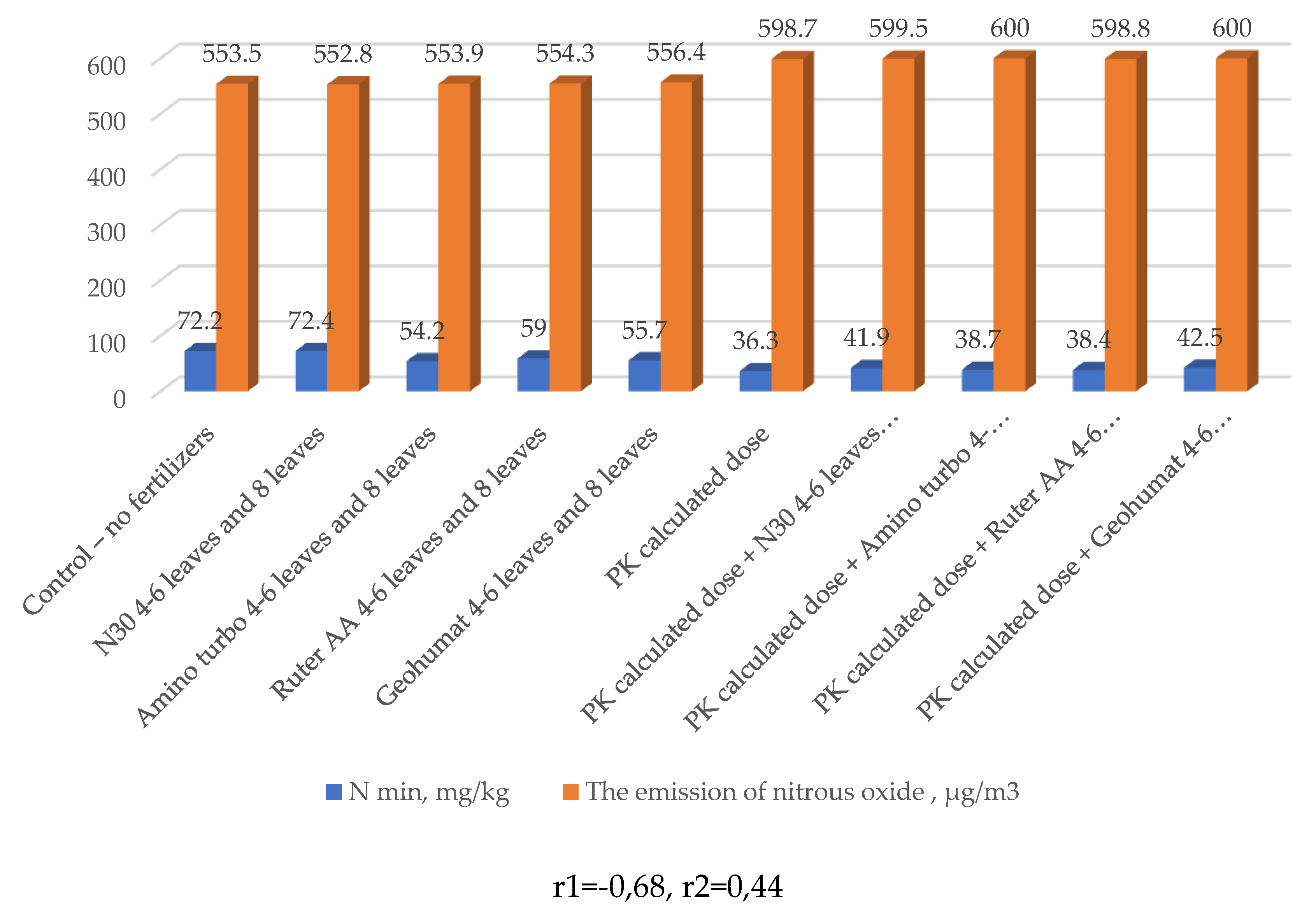

| Sugar beets, sowing 2023 | |||||

| 1 | Control – no fertilizers | 27,1 | 27,3 | 17,8 | 72,2 |

| 2 | N30 4-6 leaves and 8 leaves | 33,6 | 31,8 | 7,0 | 72,4 |

| 3 | Amino turbo 4-6 leaves and 8 leaves | 26,1 | 25,6 | 2,5 | 54,2 |

| 4 | Ruter AA 4-6 leaves and 8 leaves | 30,8 | 25,7 | 2,5 | 59 |

| 5 | Geohumat 4-6 leaves and 8 leaves | 29,9 | 22,7 | 3,1 | 55,7 |

| 6 | PK calculated dose | 20,5 | 13,3 | 2,5 | 36,3 |

| 7 | PK calculated dose + N30 4-6 leaves and 8 leaves | 22,4 | 14,1 | 5,4 | 41,9 |

| 8 | PK calculated dose + Amino turbo 4-6 leaves and 8 leaves | 22,4 | 14,3 | 2,0 | 38,7 |

| 9 | PK calculated dose + Ruter AA 4-6 leaves and 8 leaves | 19,6 | 16,9 | 1,9 | 38,4 |

| 10 | PK calculated dose + Geohumat 4-6 leaves and 8 leaves | 25,2 | 14,9 | 2,4 | 42,5 |

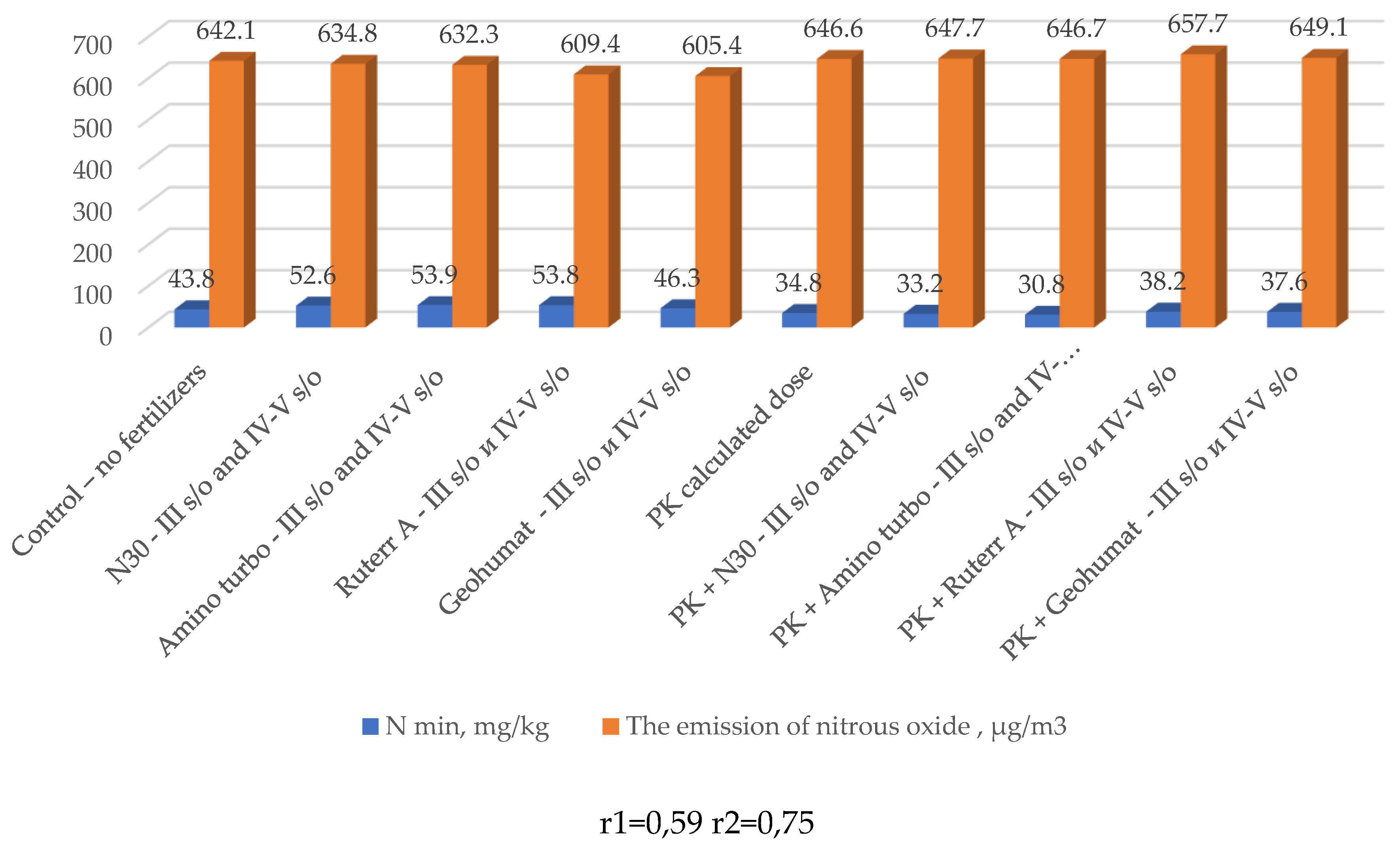

| Soybeans, sowing 2023 | |||||

| 1 | Control without fertilizers | 24,1 | 17,4 | 2,3 | 43,8 |

| 2 | N30 - III s/o and IV-V s/o | 34,5 | 15,9 | 2,2 | 52,6 |

| 3 | Amino turbo - III s/o and IV-V s/o | 33,6 | 18,3 | 2 | 53,9 |

| 4 | Ruter AA - III s/o and IV-V s/o | 33,6 | 18,8 | 1,4 | 53,8 |

| 5 | Geohumat - III s/o and IV-V s/o | 26,1 | 17,7 | 2,5 | 46,3 |

| 6 | PK calculated dose | 28,9 | 3,9 | 2,0 | 34,8 |

| 7 | PK calculated dose +N30 III s/o and IV-V s/o | 25,2 | 5,2 | 2,8 | 33,2 |

| 8 | PK calculated dose + Amino turbo III s/o and IV-V s/o | 25,2 | 3,9 | 1,7 | 30,8 |

| 9 | PK calculated dose + Ruter AA III s/o and IV-V s/o | 22,4 | 13,9 | 1,9 | 38,2 |

| 10 | PK calculated dose + Geohumate III s/o and IV-V s/o | 20,5 | 13,8 | 3,3 | 37,6 |

| Variants | Yield capacity, c/ha | Average | Increase | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c/ha | % | ||||||

| І | ІІ | ІІІ | |||||

| Control – no fertilizers | 25,80 | 30,40 | 31,40 | 29,2 | 0,0 | - | |

| PK calculated dose | 42,00 | 41,00 | 30,70 | 37,9 | 8,7 | 29,8 | |

| N30 - III s/o and IV-V s/o | 39,50 | 40,30 | 37,70 | 39,2 | 10,0 | 34,2 | |

| Amino turbo - III s/o and IV-V s/o | 37,80 | 38,10 | 33,20 | 36,4 | 7,2 | 24,7 | |

| Ruter AA - III s/o and IV-V s/o | 44,70 | 40,20 | 43,10 | 42,7 | 13,5 | 46,2 | |

| Geohumat - III s/o and IV-V s/o | 35,10 | 37,20 | 38,60 | 37,0 | 7,8 | 26,7 | |

| LSD0,05, c/ha | 5,4 | ||||||

| Variants | Yield capacity, c/ha | Average, c/ha | Increase, | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| І | ІІ | ІІІ | c/ha | % | ||

| Control | 33,6 | 36,5 | 28,3 | 32,8 | 0 | |

| P94 calculated dose | 43,2 | 38,4 | 36,7 | 39,4 | 6,6 | 20,1 |

| P94 calculated dose + N30 - III s/o and IV-V s/o | 39,6 | 40,4 | 45,3 | 41,8 | 9,0 | 27,4 |

| P94 calculated dose + Amino turbo III s/o and IV-V s/o | 44,8 | 43 | 42,7 | 43,5 | 10,7 | 32,6 |

| P94 calculated dose +Ruter AA III s/o and IV-V s/o | 42,5 | 41,6 | 48,5 | 44,2 | 11,4 | 34,8 |

| P94 calculated dose + Geohumat III s/o and IV-V s/o | 40,4 | 48,1 | 44,2 | 44,2 | 11,4 | 34,8 |

| LSD0,05, c/ha | 6,1 | |||||

| Variants | Yield capacity, c/ha | Average, c/ha | Increase | |||

| І | ІІ | ІІІ | c/ha | % | ||

| Control | 33,6 | 36,5 | 28,3 | 32,8 | 0 | |

| P94 calculated dose | 43,2 | 38,4 | 36,7 | 39,4 | 6,6 | 20,1 |

| N30 - III s/o and IV-V s/o | 39,5 | 38,5 | 39,8 | 39,3 | 6,5 | 19,8 |

| Amino turbo - III s/o and IV-V s/o | 38,9 | 37,1 | 39,9 | 38,6 | 5,8 | 17,7 |

| Ruter AA - III s/o and IV-V s/o | 38,2 | 37,8 | 37,3 | 37,8 | 5,0 | 15,2 |

| Geohumat - III s/o and IV-V s/o | 39,5 | 38,1 | 37,2 | 38,3 | 5,5 | 16,8 |

| LSD0,05, c/ha | 3,5 | |||||

| Variants | Yield capacity, c/ha | Average, t/ha | Increase, t/ha | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| І | ІІ | ІІІ | t/ha | % | ||

| Control | 54,4 | 53,1 | 56,8 | 54,8 | - | - |

| P84K351 calculated dose | 63 | 63,1 | 60,8 | 62,3 | 7,5 | 13,7 |

| N30 4-6 leaves and 8 leaves | 68,4 | 66,2 | 66,8 | 67,1 | 12,4 | 22,4 |

| Amino turbo 4-6 leaves and 8 leaves | 80,9 | 80,9 | 70,4 | 77,4 | 22,6 | 41,2 |

| Ruter AA 4-6 leaves and 8 leaves | 63,4 | 85,2 | 70,1 | 72,9 | 18,1 | 33,0 |

| Geohumat 4-6 leaves and 8 leaves | 61,1 | 85,8 | 67,9 | 71,6 | 16,8 | 30,7 |

| LSD0,05, c/ha | 10,9 | |||||

| Variants | Yield capacity, c/ha | Average, t/ha | Increase, t/ha | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| І | ІІ | ІІІ | t/ha | % | ||

| Control | 54,4 | 53,1 | 56,8 | 54,8 | - | - |

| P84K351 calculated dose | 63 | 63,1 | 60,8 | 62,3 | 7,5 | 13,7 |

| N30 4-6 leaves and 8 leaves | 63,2 | 66 | 60,4 | 63,2 | 8,4 | 15,3 |

| Amino turbo 4-6 leaves and 8 leaves | 62,5 | 62,3 | 57,9 | 60,9 | 6,1 | 11,1 |

| Ruter AA 4-6 leaves and 8 leaves | 60,2 | 64,8 | 62,8 | 62,6 | 7,8 | 14,2 |

| Geohumat 4-6 leaves and 8 leaves | 62 | 59 | 65 | 62,0 | 7,2 | 13,1 |

| LSD0,05, c/ha | 4,1 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).