1. Introduction

There has been a surge in clinical application of optical surface guidance in radiotherapy over the past decade [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Surface guidance (SG) is used to reduce imaging dose while maintaining precision in tumor targeting during Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy (SBRT). A set of optical cameras detecting harmless, non-ionizing light, are used to track a region of skin in three-dimensional space and real time. Since there is a correlation between skin and lesion motion, it is possible to infer the position of the lesion based on the position of the monitored skin region. This way, real-time information on tumor location is acquired without additional X-ray imaging. SG is used for patient setup and incidental motion detection, and has been shown to provide the same or better results when used for patient positioning and motion tracking as compared to traditional methods (lasers and markers or tattoos) [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

Surface guidance is also used for gating tumors subject to respiratory-induced motion, for instance, using breath-hold (BH) or phase gating techniques. A therapeutic beam is delivered while the patient's skin is within a certain tolerance window since it can be verified that while the skin is within that window, the lesion remains within the planned volume. Optical surface guidance is not only efficient for gated treatments of targets near the skin surface, for example breast [

12,

13,

14], but also for gated treatments of intrathoracic and abdominal targets, such as lung or liver lesions [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21].

It has been demonstrated, however, that not all skin segments are equally suitable surrogates for lesion motion management.

Bry et al. noted that different shapes and sizes of ROIs selected for surface guided treatments of patients immobilized using open-face masks can affect the incidence of false positional corrections reported by surface guidance systems [

22].

Sauer et al. have reported that different placements and sizes of ROIs used during breast radiotherapy in breath-hold (BH) technique can significantly affect the success of motion management [

23].

Zeng et al. analyzed patients treated for left sided breast cancer using surface guidance and breath inspiration technique. They found that different ROIs should be used when treating patients with different breathing behaviors (thoracic vs abdominal breathing) [

24].

Laaksomaa et al. compared three different ROIs used for patient setup during surface guided radiotherapy of the breast and found a small difference exists between them [

25].

Cui et al. [

26] and Chen et al. [

27] have both developed ROI selection algorithms for surface guided breast radiotherapy.

Yulin Song et al. analyzed several skin markers placed in areas of the abdomen used as surrogates for thoracic lesions treated in breath-hold (BH) technique and found that the markers inferior to the rib cage had a better correlation to the diaphragm movement compared to those placed in the area of the rib cage [

29].

Aside from the ROI selection, Jiateng Wang et al. noted that the correlation between tumor and skin motion can vary greatly between tumors and patients, implying that, when planning lung and liver SBRT motion management, individual patient and tumor characteristics should always be considered [

28].

The existing studies on the selection of optimal skin surface surrogates for lung lesion tracking are primarily focused on selected small regions of the thorax or the abdomen, and marker-to-lesion, rather than ROI-to-lesion respiratory motion correlation. Furthermore, while focusing on respiratory motion correlation, skin respiratory motion magnitudes are often neglected. Since optical surface monitoring systems with beam-hold allow beam-on only while the skin segment is within some tolerance window, the relative magnitude of respiratory motion to this window should also be taken into consideration.

Heinzerling et al. found that surface guidance may be a less reliable patient setup tool when used for patients with increased volumes of adipose tissue [

30]. It remains unclear how the adipose tissue distribution affects respiratory ROI magnitudes and ROI-to-lesion correlations.

In this study, four-dimensional computed tomography (4DCT) images of patients acquired for the purposes of treatment planning were used to generate correlation maps between the patient's skin and a tracking structure (TS) in the lower right lung lobe. Respiratory magnitude maps of the whole thorax and abdomen were also generated and used to determine the areas of skin best correlated to the lower lung lobe structure motions. Different ROIs were compared by correlation and amplitude to determine those best suited to be used as surrogates for lower lung lobe structures. Significant differences between ROIs were detected, both in terms of respiratory magnitudes and ROI-to-TS respiratory correlations.

Possible connections between respiratory ROI magnitudes and ROI-to-TS correlations and patient gender, subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue volumes were analyzed

2. Materials and Methods

4DCT images of 57 patients (31 female, and 26 male), with an average age of 68 years (range 43-91), acquired at our institution for treatment planning purposes were used in this study.

4DCTs with artifacts in the area of the lower lung, as well as those with Skin Structure that did not encompass the patient's skin from the upper half of the sternum to below the umbilicus (below L4), were not included in this study. Patients whose breathing was affected by paresis of the diaphragm were not included in this study.

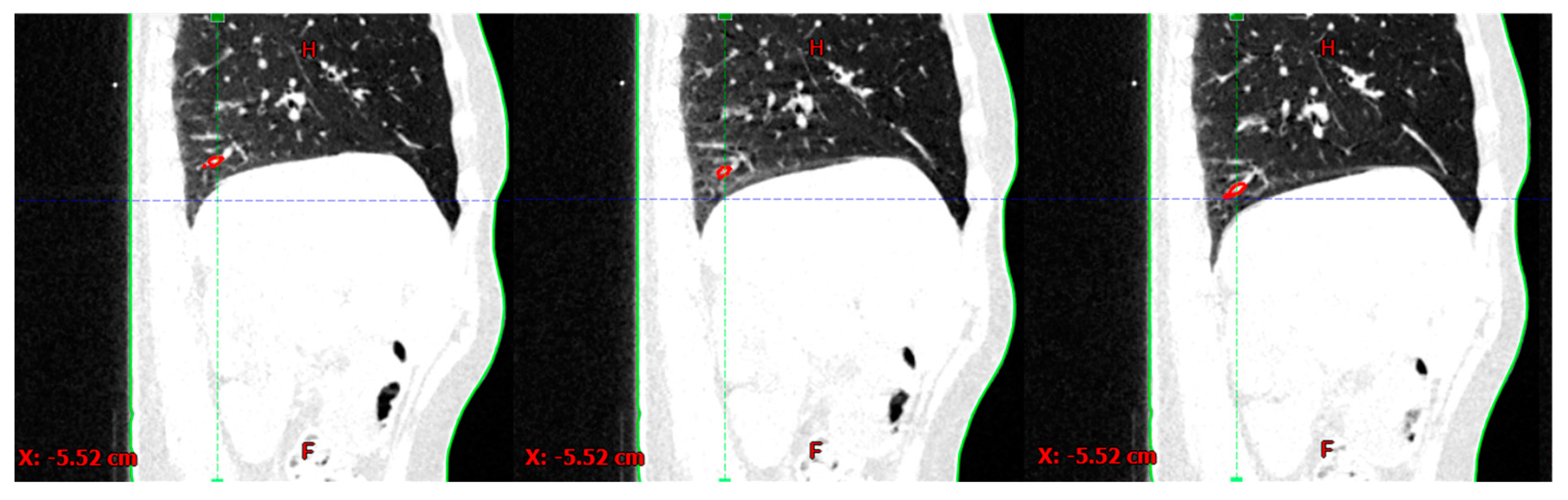

Using Eclipse treatment planning system (TPS) (Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, CA), a segment of a blood vessel in the lower right lung lobe, the Target Structure (TS), and the patient’s skin (Skin Structure) were generated on the first of the 10 4DCT phases and propagated to the other phases

Figure 1.

Using an in-house developed computer program, a centroid for Skin contour was determined at each slice. The least-square method was applied to skin centroids in order to generate a central cranio-caudal axis. For each of the CT slices (1 mm thickness), a set of radial beams at 1° intervals from 0° to 180° (total of 180 beams) connecting the axis to the Skin Structure were generated

Figure 2(

a). The beam length variations between respiratory phases were used as a measure of skin respiratory motion. TS centroid coordinate variations in craniocaudal direction between respiratory phases were used as a measure of TS motion. Only the craniocaudal direction was considered since it is the predominant motion direction for lower lung lobe structures.

Skin was divided into left, right and central regions based on the angle of the radial beams corresponding roughly to regions left, between, and right of the parasternal lines, respectively, as shown in

Figure 2(

b).

Figure 2.

(a) Radial beams originating from the craniocaudal axis. Only beams at intervals of 10° are shown. (b) Right, central, and left skin regions correspond to beam angles in the ranges of 30°-75°, 75°-105°, and 105°-150°, respectively.

Figure 2.

(a) Radial beams originating from the craniocaudal axis. Only beams at intervals of 10° are shown. (b) Right, central, and left skin regions correspond to beam angles in the ranges of 30°-75°, 75°-105°, and 105°-150°, respectively.

Pearson’s correlation between beam lengths and TS’s craniocaudal coordinates in 10 4DCT phases was computed for each of the beams, generating a skin correlation map. Beam length variation magnitudes (i.e. maximum skin excursions) were used to generate a respiratory magnitude map (

Figure 3).

Average respiratory magnitudes and correlations to TS respiratory motion were computed for nine regions shown in

Figure 3, c). The results were compared between regions using Friedman test and Dunn Bonferroni post-hoc test.

A single CT slice of abdominal fat estimate was performed at the level of L4 [

31,

32]. Subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT), visceral adipose tissue (VAT), and total adipose tissue (TAT) surfaces were measured, and their relative values to total CT slice surface computed. To evaluate the connection between adipose tissue and ROI’s respiratory magnitudes and correlations to TS, Spearman’s Rho was used.

Differences in ROI respiratory magnitudes and ROI-to-TS correlations between men and women were tested using Mann-Whitney U-test.

3. Results

Respiratory motion skin magnitude maps and skin-to-TS-Pearson’s-R correlation maps were generated. Median magnitude and correlations were computed for nine skin ROIs. The magnitude of respiratory motion was measured for all target structures.

3.1. Magnitude and Correlation Maps

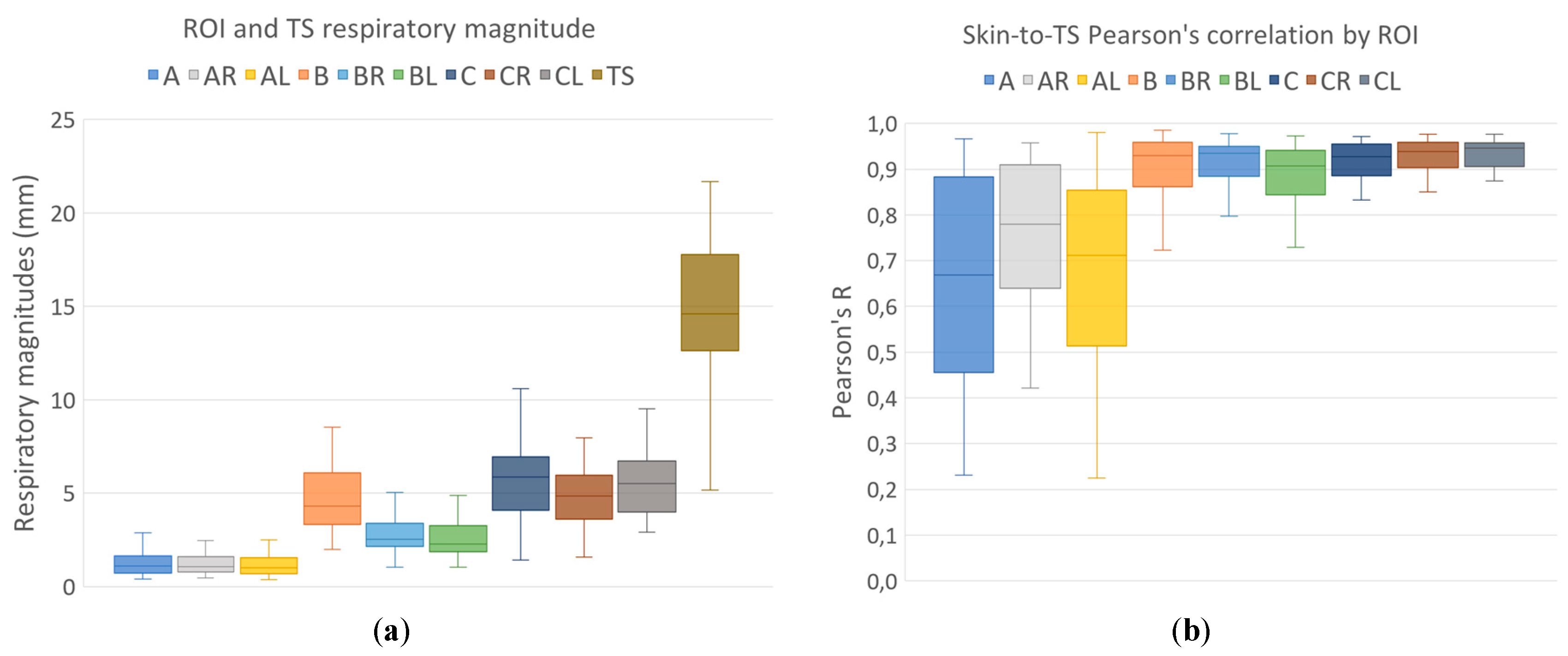

Respiratory magnitudes and ROI-to-TS correlations for different regions are shown in

Figure 4. Differences in respiratory magnitudes assessed using Friedman nonparametric test for repeated measurements were found to be significant (Chi

2(8) = 372.2; p<0.001). Post-hoc Dunn-Bonferroni test results for differences in respiratory magnitudes are presented in

Table 1.

Differences in ROI-to-TS correlations between different ROIs were also tested using Friedman nonparametric test for repeated measurements and were found to be significant (Chi

2(8) = 221.7; p<0.001). Post-hoc Dunn-Bonferroni test results for differences in ROI-to-TS correlations are shown in table

Table 1.

3.2. Magnitude and Region of Interest-to-Tracking Structure (ROI-to-TS) Correlations Related to Patient’s Sex

Respiratory magnitudes and ROI-to-TS correlations are presented in

Table 2. No difference in ROI-to-TS correlation between ROIs of patients of different sex has been detected.

A small effect size in differences between respiratory magnitudes of ROIs A, AR and AL for men and women, with magnitudes tending to be larger for women, was not statistically significant.

Medium effect size in respiratory magnitude differences between men and women, with magnitudes tending to be larger for men, were detected in regions B (U=253; z= -2.4; p=0.02; effect size r=0.32), BR (U=266.5; z=-2.19; p=0.03; r=0.29), C (U=255, z=-2.4; p=0.02; effect size r=0.31), CR (U=258, p=0.02, effect size r=0.31) and CL (U=175, z =-3.65; p<0.001; effect size r=0.48).

The difference in tracking structure respiratory magnitudes between men and women was tested using t-test for independent samples, but no significant difference was found (t(55) = -1.12; p = 0.27; 95% confidence interval [-3.52, 1.00]; Cohen’s d = 0.30).

Table 2.

A comparison of ROI respiratory magnitudes and ROI-to-TS correlations for men and women: median value (interquartile range). The differences were tested using Mann-Whitney U-test, with the exact p-values listed. Differences found significant at 5% significance level are printed in bold.

Table 2.

A comparison of ROI respiratory magnitudes and ROI-to-TS correlations for men and women: median value (interquartile range). The differences were tested using Mann-Whitney U-test, with the exact p-values listed. Differences found significant at 5% significance level are printed in bold.

| |

Median magnitude/mm, (IQR) |

p |

Median Pearson’s R, (IQR) |

p |

| Object |

Men: |

Women: |

|

Men: |

Women: |

|

A

AR

AL

|

0.92 (0.72) |

1.14 (0.74) |

0.24 |

0.71 (0.45) |

0.66 (0.34) |

0,88 |

| 0.89 (0.55) |

1.22 (0.96) |

0.11 |

0.82 (0.18) |

0.74 (0.27) |

0,41 |

| 0.92 (0.73) |

1.04 (0.80) |

0.08 |

0.73 (0.36) |

0.71 (0.27) |

0,54 |

B

BR

BL

|

5.20 (2.70)

2.85 (1.91) |

3.81 (1.80)

2.41 (0.99) |

0.02 |

0.93 (0.04)

0.92 (0.07) |

0.94 (0.01)

0.93 (0.11) |

1 |

| 0.36 |

0,35 |

| 2.77 (1.51) |

2.06 (1.12) |

0.03 |

0.90 (0.11) |

0.91 (0.09) |

0,74 |

C

CR

CL

|

6.39 (2.58) |

5.67 (2.01) |

0.02 |

0.93 (0.06) |

0.92 (0.07) |

0,81 |

| 5.59 (2.25) |

4.40 (2.24) |

0.02 |

0.95 (0.05) |

0.93 (0.06) |

0,35 |

| 6.27 (2.08) |

4.00 (1.96) |

<0.001 |

0.95 (0.05) |

0.94 (0.05) |

0,27 |

3.3. ROI Magnitudes Related to Patient’s Adipose Tissue

Adipose tissue was measured on a single CT slice at the level of L4. The tissue in the range of -20 to -150 Hounsfield units was delineated and total adipose tissue (TAT) was separated into visceral (VAT) and subcutaneous (SAT) adipose tissue, as shown in Figure 5. Total slice surface area was also measured. The percentage of total (TAT%), visceral (VAT%) and subcutaneous (SAT%) adipose tissue was determined.

Figure 5.

An example of subcutaneous (magenta) and visceral (orange) adipose tissue delineated on a single CT slice at the level of L4. Areas of the delineated surfaces relative to the total slice surface area were used to compute subcutaneous, visceral and total adipose tissue percentages (SAT%, VAT% and TAT%, respectively).

Figure 5.

An example of subcutaneous (magenta) and visceral (orange) adipose tissue delineated on a single CT slice at the level of L4. Areas of the delineated surfaces relative to the total slice surface area were used to compute subcutaneous, visceral and total adipose tissue percentages (SAT%, VAT% and TAT%, respectively).

An overall negative correlation between adipose tissue percentage and ROI respiratory magnitudes has been detected, as seen in

Table 3.

3.4. ROI-to-TS Correlation Related to Patient’s Adipose Tissue—Correlations

For adipose tissue and ROI-to-TS correlation, the connection was not an overall negative one, as seen in

Table 3. For ROIs in the upper part of the thorax, a negative correlation between adipose tissue and ROI-to-TS correlation was detected. The effect was low to moderate in strength when total population was viewed, but it varied between ROIs, men, and women.

When men and women were assessed cumulatively, a moderate negative correlation between ROI-to-TS respiratory correlation and VAT% was observed for region A (Rho =-0.38; p=0.004), AR (Rho =-0.34; p = 0.01) and AL (Rho=-0.34; p=0.01), BR (Rho =-0.33; p=0.01) and BL (Rho=-0.30; p=0.02).

A moderate negative correlation between ROI-to-TS respiratory correlation and TAT% was observed for region A (Rho=-0.35; p=0.007), AR (Rho=-0.39; p=0.003) and AL (Rho=-0.43; p=0.001).

4. Discussion

While respiratory motion amplitudes of both lung structure and skin varied greatly between patients and ROIs, all of the nine ROIs observed in this study showed a high correlation to tracking structure respiratory motion.

Large differences in respiratory magnitudes were observed between the regions with and without rib support (A, AR, AL, BR, BL, and B, C, CR, CL, respectively; p < 0,001), but also between the regions with rib support – magnitudes of hypochondriac regions (BR, BL) had significantly larger amplitudes (p = 0,002 or less) than mammary and sternal regions in the upper thorax (A, AR, AL).

The observed correlations between respiratory ROI and tracking structure motion were significantly lower for upper thoracic skin regions (A, A

R, A

L) than for the rest of the ROIs (p < 0,001), in accordance with the findings of Yulin Song et al. [

18] No other differences in ROI-to-TS correlations between skin ROIs were detected.

No differences between men and women in ROI-to-TS correlation maps were detected. ROI respiratory magnitudes were overall higher for men than for women, however, this was a relatively small effect size and should not affect clinical decisions.

Total, subcutaneous, and visceral adipose tissue percentages had different correlations to ROI respiratory magnitudes and to ROI-to-TS correlations. Overall, a moderate negative correlation between ROI respiratory magnitudes and VAT% and TAT% was detected for regions with rib support.

A moderate negative correlation between ROI-to-TS correlation and VAT% and TAT% was observed, indicating that patients with increased total adipose tissue volumes and increased visceral adipose tissue volumes could benefit from tracking the regions without rib support. The negative correlation between adipose tissue and respiratory magnitudes and ROI-to-TS correlations is in accordance with Heinzerling et al. [

24] report that initial setup accuracy based on surface guidance deteriorates as the body mass index (BMI) of the patient increases. However, this study shows that different distributions of adipose tissue affect ROIs in different ways. Specifically, visceral adipose tissue seemed to have a stronger negative correlation to ROI characteristics than subcutaneous adipose tissue.

The findings of this study also suggest possible differences between the effects of adipose tissue on correlation and magnitude maps between men and women, but due to the small sample size, this requires further investigation.

5. Conclusions

Since all forms of surface tracking use a threshold within which the skin surrogate needs to remain for the beam to be on, breathing magnitude, along with respiratory motion correlation between skin region and lesion, should be key when choosing the skin surrogate. If skin ROI is strongly correlated to target structure, but its respiratory motion magnitude is comparable to or smaller than the gating window, it may not be a good choice for gated SBRT. The results of this study imply that regions A, AR and AL should only ever be tracked to detect incidental motion, as regions BR, BL and especially B, C, CR, CL are more suitable as skin surrogates for gated treatments of lower lung lobe lesions both in terms of respiratory magnitudes and ROI-to-TS correlations. This could be especially important for patients with high amounts of adipose tissue.

Due to large variations observed between the patients, the choice of skin surrogate, and especially tolerances if tracking ROI for a gated treatment, should be assessed individually.

It should also be noted that these findings relate to the free-breathing technique only – correlation maps and magnitude maps for patients treated using breath-hold technique may behave differently and require further investigation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Domagoj Kosmina and Vanda Leipold; methodology, Fran Stanić, Ivana Alerić, Vanda Leipold, Mihaela Mlinarić, Mladen Kasabašić, Hrvoje Kaučić; software, Fran Stanić, Damir Štimac, Vanda Leipold; validation, Karla Schwarz, Igor Nikolić, Denis Klapan, Dragan Schwarz, Mladen Kasabašić, Damir Štimac, Hrvoje Kaučić; formal analysis, Vanda Leipold, Mladen Kasabašić; investigation, Ivana Alerić, Igor Nikolić, Denis Klapan, Karla Schwarz and Vanda Leipold; resources, Vanda Leipold, Ivana Alerić, Mihaela Mlinarić, Igor Nikolić, Denis Klapan, Karla Schwarz; data curation, Ivana Alerić, Mihaela Mlinarić, Fran Stanić, Domagoj Kosmina, Giovanni Ursi and Vanda Leipold; writing—original draft preparation, Vanda Leipold; writing—review and editing, Mladen Kasabašić, Mihaela Mlinarić, Damir Štimac, Ivana Alerić, Karla Schwarz, Giovanni Ursi, Hrvoje Kaučić; visualization, Vanda Leipold; supervision, Domagoj Kosmina, Dragan Schwarz, Vanda Leipold, Mladen Kasabašić, Damir Štimac; project administration, Vanda Leipold, Mladen Kasabašić; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study did not require ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Hrvoje Brkić, Vesna Ilakovac, Joshua Naylor, Adlan Čehobašić and Ana Kovačić for their precious time, good will and advice.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Al-Hallaq, H.A.; Cerviño, L,; Gutierrez AN, Havnen-Smith, A,; Higgins, S.A.;, Kügele, M. et al. AAPM task group report 302: Surface-guided radiotherapy. Medical Physics 2022, 49, 82-112. [CrossRef]

- Mast, M.; Perryck, S. Introduction to: Surface Guided Radiotherapy (SGRT). Tech Innov Patient Support Radiat Oncol. 2022; 22, 37-38. [CrossRef]

- Li, G. Advances and potential of optical surface imaging in radiotherapy. Phys Med Biol. 2022, 67. [CrossRef]

- Freislederer, P.; Kügele, M.; Öllers, M. et al. Recent advanced in Surface Guided Radiation Therapy. Radiat Oncol. 2020, 15, 187-198. [CrossRef]

- Freislederer, P.;Batista, V.; Öllers, M. et al. ESTRO-ACROP guideline on surface guided radiation therapy. Science Direct 2022, 173, 188-196. [CrossRef]

- Psarras, M.; Stasinou, D.; Stroubinis, T.; Protopapa, M.; Zygogianni, A.; Kouloulias, V.; Platoni, K. Surface-Guided Radiotherapy: Can We Move on from the Era of Three-Point Markers to the New Era of Thousands of Points?. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 1202-1222. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Paxton, A.; Sarkar, V.; Price, R.G.; Huang, J.; Su, F.F.; Li, X.; Rassiah, P.; Szegedi, M.; Salter, B. Surface-Guided Patient Setup Versus Traditional Tattoo Markers for Radiation Therapy: Is Tattoo-Less Setup Feasible for Thorax, Abdomen and Pelvis Treatment?. Cureus 2022, 14, e28644. [CrossRef]

- Penninkhof, J.; Fremeijer, K.; Offereins-van Harten, K. et al. Evaluation of image-guided and surface-guided radiotherapy for breast cancer patients treated. in deep inspiration breath-hold: A single institution experience. Tech Innov Patient Support Radiat Oncol. 2022, 21, 51-57. [CrossRef]

- Rudat, V., Shi, Y., Zhao, R. et al. Setup accuracy and margins for surface-guided radiotherapy (SGRT) of head, thorax, abdomen, and pelvic target volumes. Sci Rep. 2023, 13, 17018. [CrossRef]

- Covington, E.L.; Stanley, D.N.; Sullivan, R.J.; Riley, K.O.; Fiveash, J.B.; Popple, R.A.; Commissioning and clinical evaluation of the IDENTIFYTM surface imaging system for frameless stereotactic radiosurgery. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2023, 24, e14058. [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, W.; Leech, M. Feasibility of surface guided radiotherapy for patient positioning in breast radiotherapy versus conventional tattoo-based setups- a systematic review. Technical Innovations & Patient Support in Radiation Oncology 2022, 22, 39-49. 10.1016/j.tipsro.2022.03.001.

- Huijskens, S.; Granton, P.; Fremeijer, K.; van Wanrooij, C.; Offereins-van Harten, K.; Schouwenaars-van den Beemd, S.; Hoogeman, M.S.; Sattler, M.G.A.; Penninkhof, J. Clinical practicality and patient performance for surface-guided automated VMAT gating for DIBH breast cancer radiotherapy, Radiotherapy and Oncology 2024, 195, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hoisak, J.D.P.; Pawlicki, T. The Role of Optical Surface Imaging Systems in Radiation Therapy. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2018, 28, 185-193. [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Lu, W.; O'Grady, K.; Yan, I.; Yorke, E.; Arriba, L.; Powell, S.; Hong, L. A uniform and versatile surface-guided radiotherapy procedure and workflow for high-quality breast deep-inspiration breath-hold treatment in a multi-center institution. Journal of Applied Clinical Medical Physics 2022, 23, e13511. 10.1002/acm2.13511.

- Dieterich, S.; Green, O.; Booth, J. SBRT targets that move with respiration. Phys Med. 2018, 56, 19-24. [CrossRef]

- Naumann, P.; Batista, V.; Farnia, B.; Fischer, J.; Liermann, J.; Tonndorf-Martini, E.; Rhein, B.; Debus, J. Feasibility of Optical Surface-Guidance for Position Verification and Monitoring of Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy in Deep-Inspiration Breath-Hold. Front Oncol. 2020, 10, 573279. [CrossRef]

- Aznar, M. C. et al.ESTRO-ACROP guideline: Recommendations on implementation of breath-hold techniques in radiotherapy Radiotherapy and Oncology, 2023, 185, 109734. 10.1016/j.radonc.2023.109734.

- Paolani, G.; Strolin, S.; Santoro, M.; Della Gala, G.; Tolento, G.; Guido, A.; Siepe, G.; Morganti, A.G.; Strigari, L. A novel tool for assessing the correlation of internal/external markers during SGRT guided stereotactic ablative radiotherapy treatments. Phys Med. 2021, 92, 40-51. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Lu, W.; Reyngold, M.; Cuaron, J.J.; Li, X.; Cerviño, L.; Li, T. Intrafractional accuracy and efficiency of a surface imaging system for deep inspiration breath hold during ablative gastrointestinal cancer treatment. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2022, 23, e13740. [CrossRef]

- Kiser, K.; Schiff, J.; Laugeman, E.; Kim, T.; Green, O.; Hatscher, C.; Kim, H.; Badiyan, S.; Spraker, M.; Samson, P.; Robinson, C.; Price, A.; Henke, L. A feasibility trial of skin surface motion-gated stereotactic body radiotherapy for treatment of upper abdominal or lower thoracic targets using a novel O-ring gantry, Clinical and Translational Radiation Oncology 2024, 44, 100692. [CrossRef]

- Kaučić, H.; Kosmina, D.; Schwarz, D.; Mack, A.; Čehobašić, A.; Leipold, V.; Avdičević, A.; Mlinarić, M.; Lekić, M.; Schwarz, K.; Banović, M. Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy for Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer Using Optical Surface Management System - AlignRT as an Optical Body Surface Motion Management in Deep Breath Hold Patients: Results from a Single-Arm Retrospective Study. Cancer Manag Res. 2022, 14, 2161-2172..

- Bry, V.; Licon, A.L.; McCulloch, J.; Kirby, N.; Myers, P.; Saenz, D.; Stathakis, S.; Papanikolaou, N.; Rasmussen, K. Quantifying false positional corrections due to facial motion using SGRT with open-face Masks. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2021, 22, 172-183. [CrossRef]

- Sauer, T.O.; Ott, O.J.; Lahmer, G.; Fietkau, R.; Bert, C. Region of interest optimization for radiation therapy of breast cancer. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2021, 22, 152-160. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Fan, Q.; Li, X.; Hong, L.; Powell, S.; Li, G. A Potential Pitfall and Clinical Solutions in Surface-Guided Deep Inspiration Breath Hold Radiation Therapy for Left-Sided Breast Cancer Advances in Radiation Oncology 2023, 8, 101276. [CrossRef]

- Laaksomaa, M.; Moser, T.; Kritz, J.; Pynnonen, K.; Rossi, M. Comparison of three differently shaped ROIs in free breathing breast radiotherapy setup using surface guidance with AlignRT((R)). Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2021, 26, 545-552. 10.5603/RPOR.a2021.0062.

- Cui, S.; Li, G.; Kuo, H-C.; Zhao, B.; Li, A.; Cerviño, L.I. Development of automated region of interest selection algorithms for surface-guided radiation therapy of breast cancer. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2024, 25, e14216. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chen, M.; Lu, W. et al. Deep-learning based surface region selection for deep inspiration breath hold (DIBH) monitoring in left breast cancer radiotherapy. Phys Med Biol. 2018, 63, 245013.. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Song, X.; Li, G. et al. Correlation of Optical Surface Respiratory Motion Signal and Internal Lung and Liver Tumor Motion: A Retrospective Single-Center Observational Study. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2022, 21, 15330338221112280. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y., Zhai, X.; Liang, Y.; Zeng, C.; Mueller, B.; Li, G. Evidence-based region of interest (ROI) definition for surface-guided radiotherapy (SGRT) of abdominal cancers using deep-inspiration breath-hold (DIBH), J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2022, 23, 13748. [CrossRef]

- Heinzerling, J.H.; Hampton, C.J.; Robinson, M.; Bright, M.; Moeller, B.J.; Ruiz, J.; Prabhu, R.; Burri, S.H.; Foster, R.D. Use of surface-guided radiation therapy in combination with IGRT for setup and intrafraction motion monitoring during stereotactic body radiation therapy treatments of the lung and abdomen. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2020, 21, 48-55. [CrossRef]

- Pescatori, L.C.; Savarino, E.; Mauri, G.; Silvestri, E.; Cariati, M.; Sardanelli, F.; Sconfienza, L.M.. Quantification of visceral adipose tissue by computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging: reproducibility and accuracy. Radiol Bras. 2019, 52, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Jacobi, V.; Steinkamp, M.; Kirchner, J.; Fischer, H.; Diedrich, C. F.; Kollath, J. The Computed Tomographic Determination of Intra-Abdominal Fat Volume by Single-Layer Measurement. RoFo: Fortschritte Auf Dem Gebiete Der Rontgenstrahlen Und Der Nuklearmedizin 1997, 166 (2), 115–119. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Spearman’s Rho = +1.

Spearman’s Rho = +1.