1. Introduction

Systemic therapies, including chemotherapy and endocrine therapy, have significantly improved the overall survival of patients with early-stage breast cancer [

1,

2]. Anthracycline-based and taxane-based chemotherapy regimens are widely employed in adjuvant settings for early-stage breast cancer. Additionally, patients with certain intrinsic subtypes exhibit high sensitivity to neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) [

3]. NAC aims to downstage the disease, potentially enabling breast-conserving surgery as an alternative to mastectomy. However, chemoresistance remains a critical challenge in breast cancer recurrence and metastasis [

3,

4,

5]. Identifying markers that predict a patient's response to NAC can significantly improve patient outcomes [

6].

Progesterone receptor membrane component 1 (PgRMC1) is a progesterone-binding protein, initially purified from liver membrane fractions [

7]. PgRMC1 exhibits diverse subcellular localizations, including the plasma membrane, endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, and nucleus [

8,

9]. Recent studies have highlighted elevated PgRMC1 expression in various cancer cells, including ovarian, liver, lung, colon, and breast cancer cells [

10,

11,

12]. Notably, PgRMC1 expression correlates with cancer development, chemoresistance, and poor prognosis [

9,

13,

14].

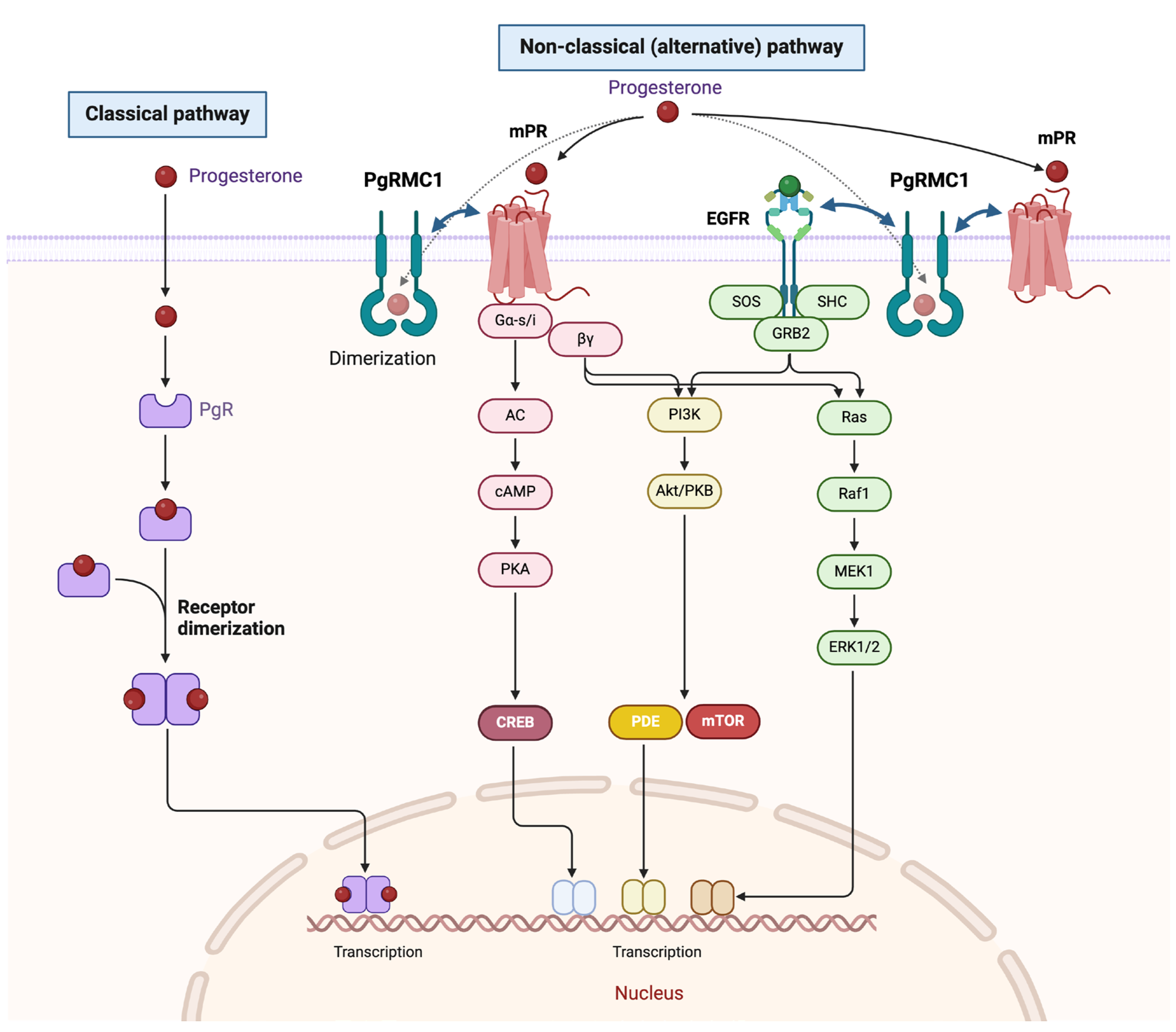

Functional investigations have revealed that PgRMC1 plays a role in cell proliferation, independent of the classical progesterone receptor (PgR) pathway [

15,

16]. Furthermore, PgRMC1 interacts directly with P450 proteins, including CYP3A4, plasminogen activator inhibitor mRNA-binding protein 1 (PAIR-BP1), and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) [

8]. Notably, PgRMC1 undergoes unique haem-dependent dimerization, further enhancing its binding to EGFR and cytochrome P450, thereby promoting tumor cell proliferation and chemoresistance [

17].

To clarify the biological function of PgRMC1 in breast cancer, we examined PgRMC1 expression in human breast cancer specimens and its association with response to NAC in operable breast cancer. We also investigated the mechanisms underlying PgRMC1-related chemoresistance in breast cancer cell lines.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Endoribonuclease-prepared siRNAs (esiRNAs) for PgRMC1, and their negative controls were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Progesterone (P8783) was purchased from Merck (Sigma-Aldrich®, St. Louis, MO). Rabbit antibodies against PgRMC1(D6M5M), phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2)(Thr202/Tyr204)(#9101), and phospho-Akt(Ser473)(D9E) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). The CONFIRM anti-estrogen receptor (ER) (SP1) rabbit monoclonal antibody (ultraView kit, no. 790-4324), anti-PgR (1E2) rabbit monoclonal antibody (ultraView kit, no.760-2223), and PATHWAY anti-HER-2/neu (4B5) rabbit monoclonal antibody (no.790-2991) were purchased from Ventana (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Monoclonal mouse anti-human Ki-67 antibody (clone MIB-1) was obtained from Dako (Agilent Technologies Company, Santa Clara, CA).

2.2. Patients and Samples

Breast cancer surgical specimens were obtained from patients with invasive breast cancer who were treated at Kyorin University Hospital between 2008 and 2011 (n=112,

Table 1). Approximately 125mm

3 of cancer tissues were excised and frozen at -80°C, then used for gene expression analysis. The rest of the tissues were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 48h and embedded in paraffin. Core needle biopsy samples from patients treated with NAC at Kyorin University Hospital between 2014 and 2017 (n=27) were also used for association analyses with chemotherapy response. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Kyorin University School of Medicine (approval no. 287 and no. 616 in Japanese).

2.3. Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed as previously described [

18]. Briefly, 4µm-thick sections were prepared on silane-coated glass slides. Samples were incubated with appropriate primary antibodies (PgRMC1, dilution 1:1000; Ki-67, 1:100). Immunoreactivity was visualized with diaminobenzidine (DAB) using an Envision IHC kit from DAKO (Carpinteria, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. PgRMC1 expression levels were evaluated according to the Allred scoring system (total score [TS] 0-8 = proportion score [PS] 0-5 + intensity score [IS] 0-3). ER, PgR, HER2, and Ki-67 IHC were evaluated following the ASCO/CAP guidelines [

19] and tumors were classified into surrogate intrinsic subtypes: luminal A (ER/PgR+, HER2-, low Ki-67), luminal B (ER/PgR+, HER2+; or ER/PgR+, HER2-, high Ki-67), HER2 (ER/PgR-, HER2+), and triple-negative (ER/PgR-, HER2-).

2.4. Real-Time qPCR Analyses

Total RNA was extracted from frozen tissue samples. Real-time qPCR was performed as previously described [

20]. In brief, total RNA was prepared from FFPE sections using the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit from Qiagen, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription was carried out using the ReverTra Ace kit from TOYOBO (Osaka, Japan). RT-PCR was performed using Fast SYBR® Green Master Mix from Applied Biosystems under the following conditions: denaturation at 95°C for 30s, annealing at 60°C (PgRMC1 62.5°C) for 30sec, and extension at 72°C for 60s, repeated 40 cycles (primer sets used in the study are indicated in

Table 2). Primer sequences are given in

Table 1. The relative mRNA expression was determined by the 2−∆∆Ct method with GAPDH mRNA for normalization.

2.5. Cell lines, Cell Culture, and Transient Transfection

We used six human breast cancer cell lines: luminal subtype cell lines (MCF7 and T47D), HER2 subtype cell line (SKBR3), and triple-negative cell lines (MDA-MB231, MDA-MB453, and MDA-MB-468). All cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) (Sigma-Aldrich®) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Bio West, Nuaillé, France), supplemented with 50U/mL penicillin and 100µg/mL streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich®) at 37°C and 5% CO2.

For transient transfection, 1 × 106 cells were seeded in each well of a 6-well plate the day before transfection and transfected with 2.5μg PgRMC1 vector (ORIGENE, Rockville, MD) and empty backbone vector using Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For PgRMC1 knockdown, 1 × 106 cells were transfected with 30pmol of esiRNAs targeting PgRMC1 (Sigma-Aldrich®) or negative controls (Sigma-Aldrich®) using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

For cytotoxicity assays, cells with or without overexpression/knockdown of PgRMC1 were seeded at 3×103 cells/well in 96-well plates. Cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with charcoal-treated FBS (10%) and 1nM E2+10nM progesterone, together with the indicated concentrations of adriamycin, paclitaxel, and docetaxel for 48 hours. We added the CCK-8 (WST-8) solution (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc., Rockville, MD) to detect relative cell viability and measured the absorbance at 450 nm using a microplate reader.

2.6. Immunoblot Analysis

Immunoblot analyses were carried out as previously described [

19]. Briefly, 20μg of protein was subjected to normal SDS-PAGE with 8%–16% precast polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and was transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Bio-Rad). Membranes were soaked with appropriate primary antibodies at 4°C overnight (PgRMC1, 1:1000; β-actin, 1:5000; p-ERK1/2, 1:1000; p-Akt, 1:2000). Immunogenic bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Super Signal Western Blot Enhancer; Thermo Scientific) and ChemiDoc XRS+ System (Bio-Rad).

2.7. KM Plotter Analysis

The prognostic values of PgRMC1 in breast cancer were determined using the KM survival plotter (

www.kmplot.com), an online database containing gene expression profiles and clinical data from public databases [

21]. KM survival plots were used to compare the overall survival (OS) of the low and high expression groups.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as means and standard deviations. Non-parametric tests were used to compare between two or more groups. Statistical analyses were performed using JMP® 13 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.9. Illustrations

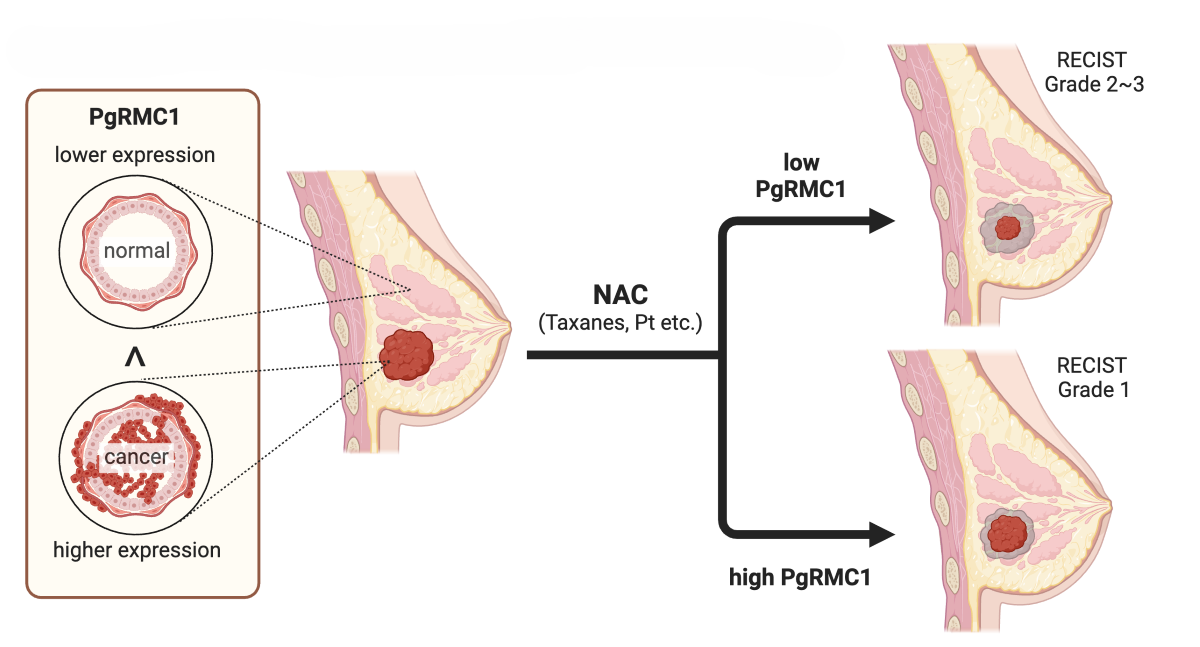

The graphical abstract and

Figure 8 were created with BioRender.com.

3. Results

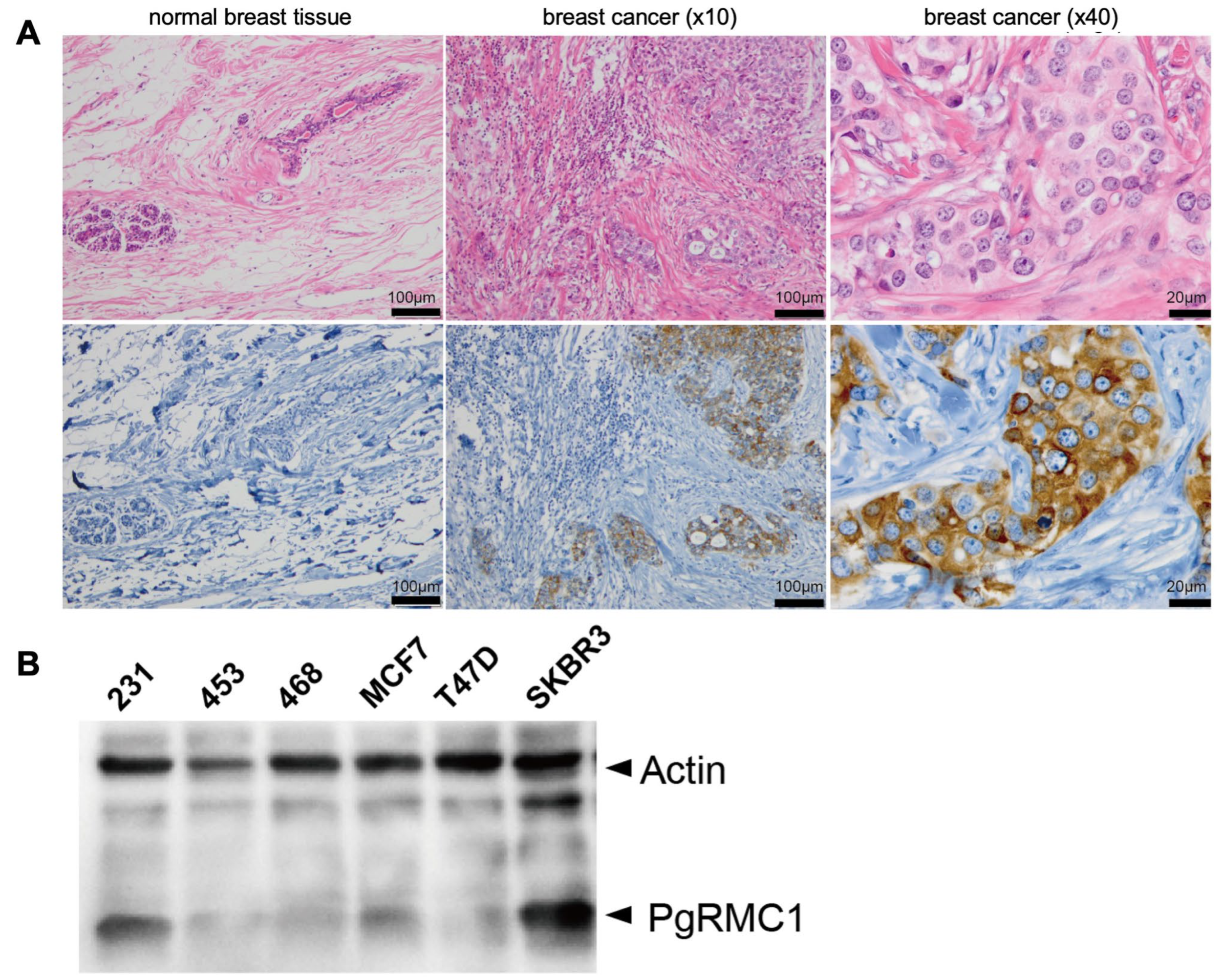

3.1. PgRMC1 Is Expressed in Breast Cancer Cells

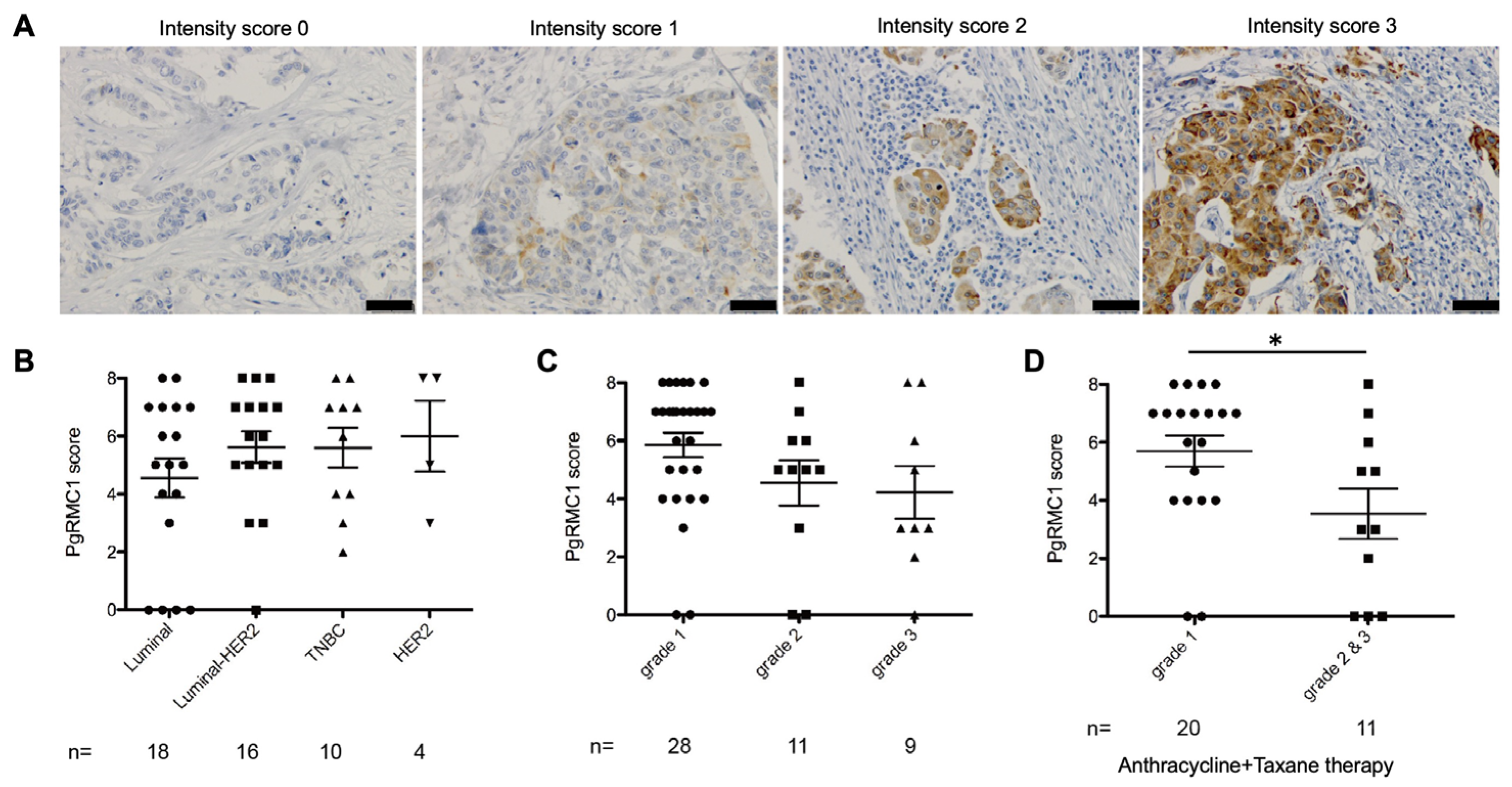

PgRMC1 expression was examined by immunohistochemistry (IHC) in normal human breast tissue and breast cancer specimens (

Figure 1A). The expression of PgRMC1 was confirmed in breast cancer tissues, while almost no PgRMC1 was detected in normal breast tissue under the conditions. PgRMC1 is diffusely located in the cytoplasm of breast cancer cells and focally detected on the plasma membrane and perinuclear region.

Next, we performed immunoblot analyses of PgRMC1 in several breast cancer cell lines (

Figure 1B). We detected higher PgRMC1 expression in SKBR3 cells (HER2 subtype) and MDA-MB231 (triple-negative subtype) than those in other cell lines (

Figure 1B).

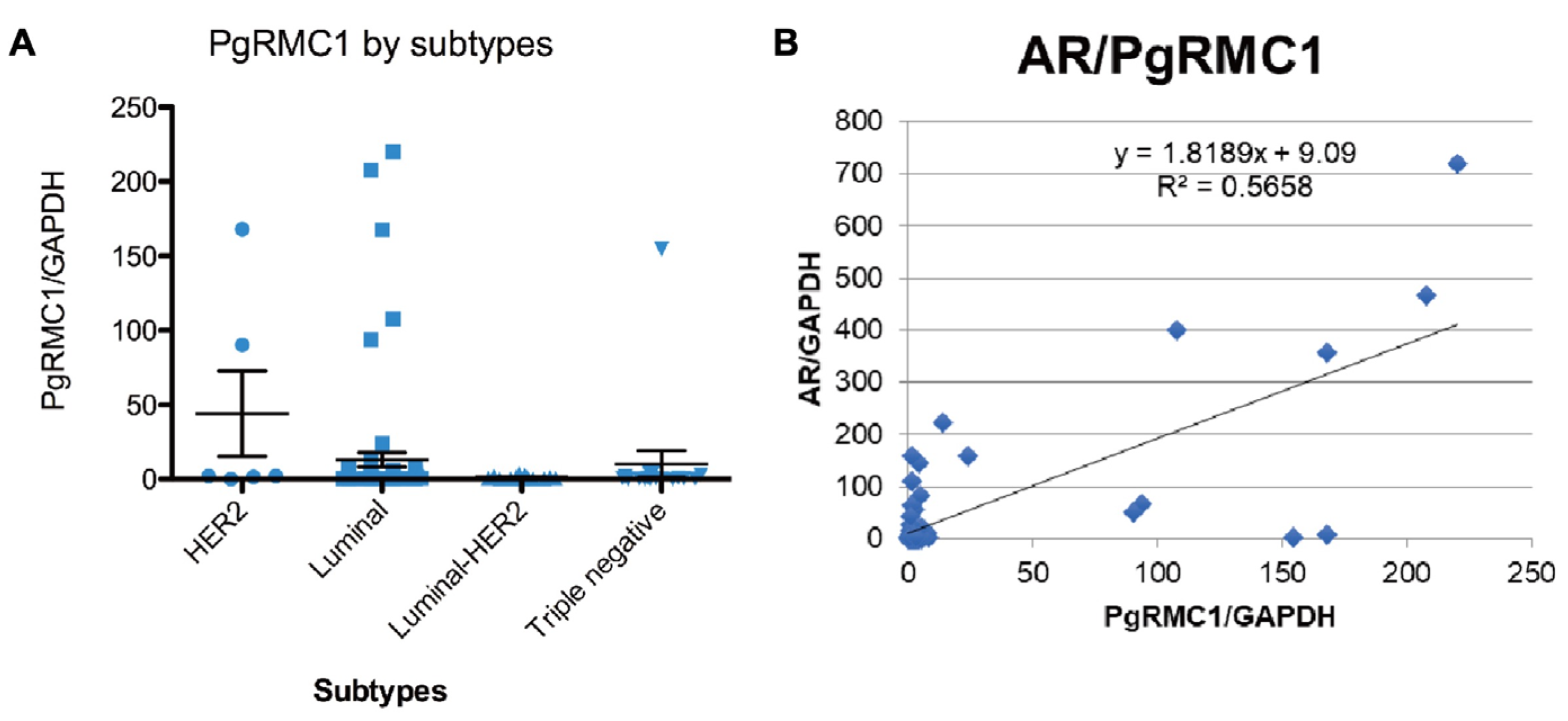

3.2. Expression Levels of PgRMC1 in Core Needle Biopsy Specimens Correlated with Responses to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy

The mRNA expression levels of ER, PgR, HER2, AR, and PgRMC1 were determined by real-time qPCR from frozen breast cancer tissue samples obtained from 112 patients (

Figure 2A). PgRMC1 mRNA expression levels were higher in luminal and HER2 subtypes (Kruskal–Wallis; p =0.0054). PgRMC1 mRNA expression levels were significantly correlated with AR expression levels (Spearman’s rank correlation ρ, p<0.0001) (

Figure 2B).

Next, we examined whether PgRMC1 expression levels in core needle biopsy (CNB) specimens correlated with pathological therapeutic response to NAC (

Figure 3). We collected 27 invasive breast cancer patients treated with anthracycline or anthracycline plus taxane regimens for NAC, whose surgical specimens excised after NAC were pathologically evaluated according to the RECIST 1.1 (Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors) guidelines [

22]. PgRMC1 expression levels were not significantly different among intrinsic subtypes, although PgRMC1 showed tendency toward increase in lumina B (lumina-HER2), HER2, and triple-negative subtypes (

Figure 3B). PgRMC1 expression levels were slightly higher in samples of lower WHO histological grades (

Figure 3C). Patients with poor pathological therapeutic responses to NAC (grade 1) showed significantly higher PgRMC1 expression levels than those with better pathological responses (garade2&3) (Kruskal–Wallis; p =0.0174) (

Figure 3D).

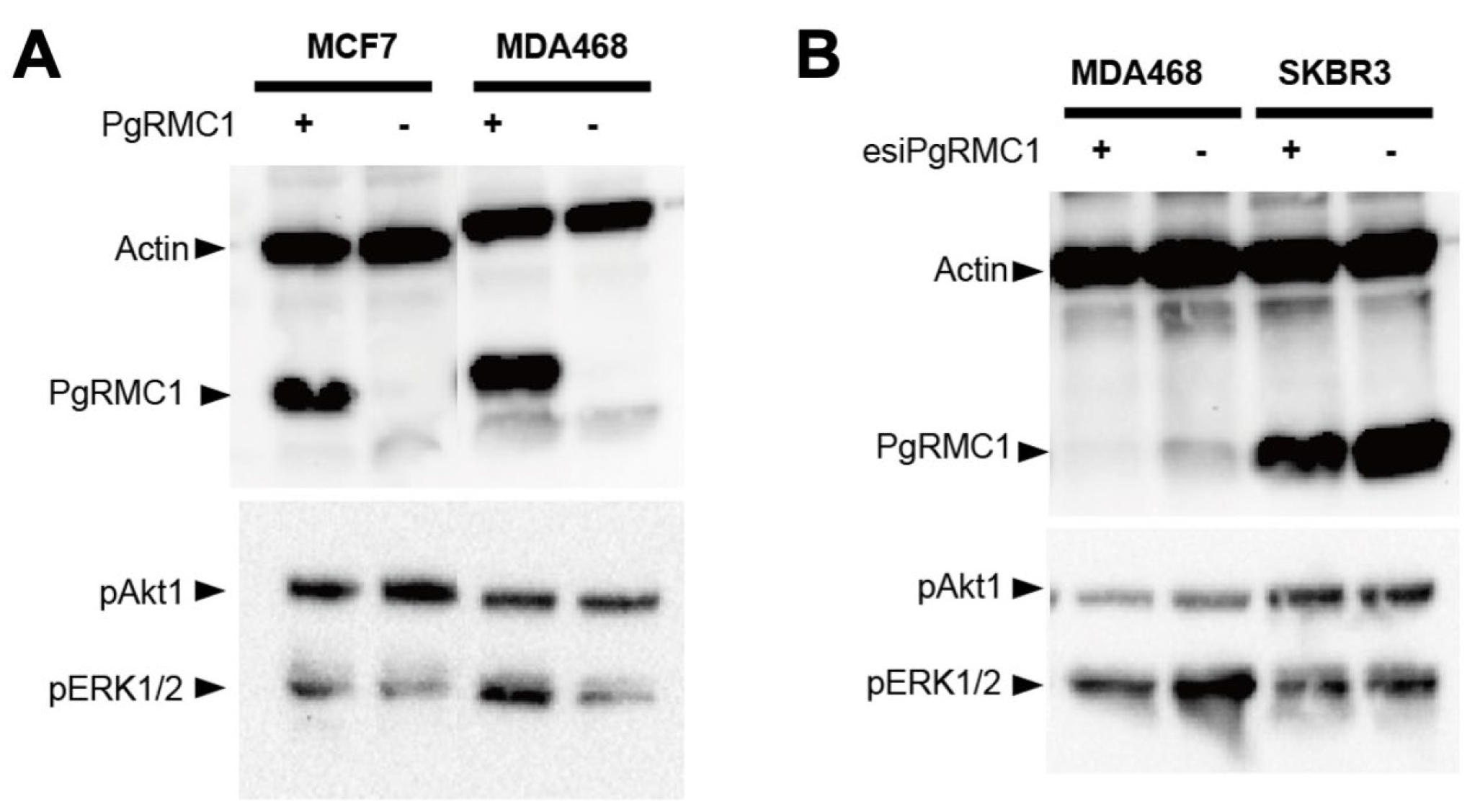

3.3. PgRMC1 Augments Resistance to Chemotherapeutic Drugs in Breast Cancer Cell Lines

We first examined the effects of forced ectopic overexpression and knockdown of PgRMC1 by lipid-mediated transient transfection in breast cancer cell lines. As shown in

Figure 4, the PgRMC1 vector, and esiRNAs for PgRMC1 were successfully introduced into the cell lines. PgRMC1 overexpression induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation in MCF7 and MDA-MB468 cells (

Figure 4A), while PgRMC1 knockdown mildly reduced ERK1/2 phosphorylation in MDA-MB468 and SKBR3 cells (

Figure 4B).

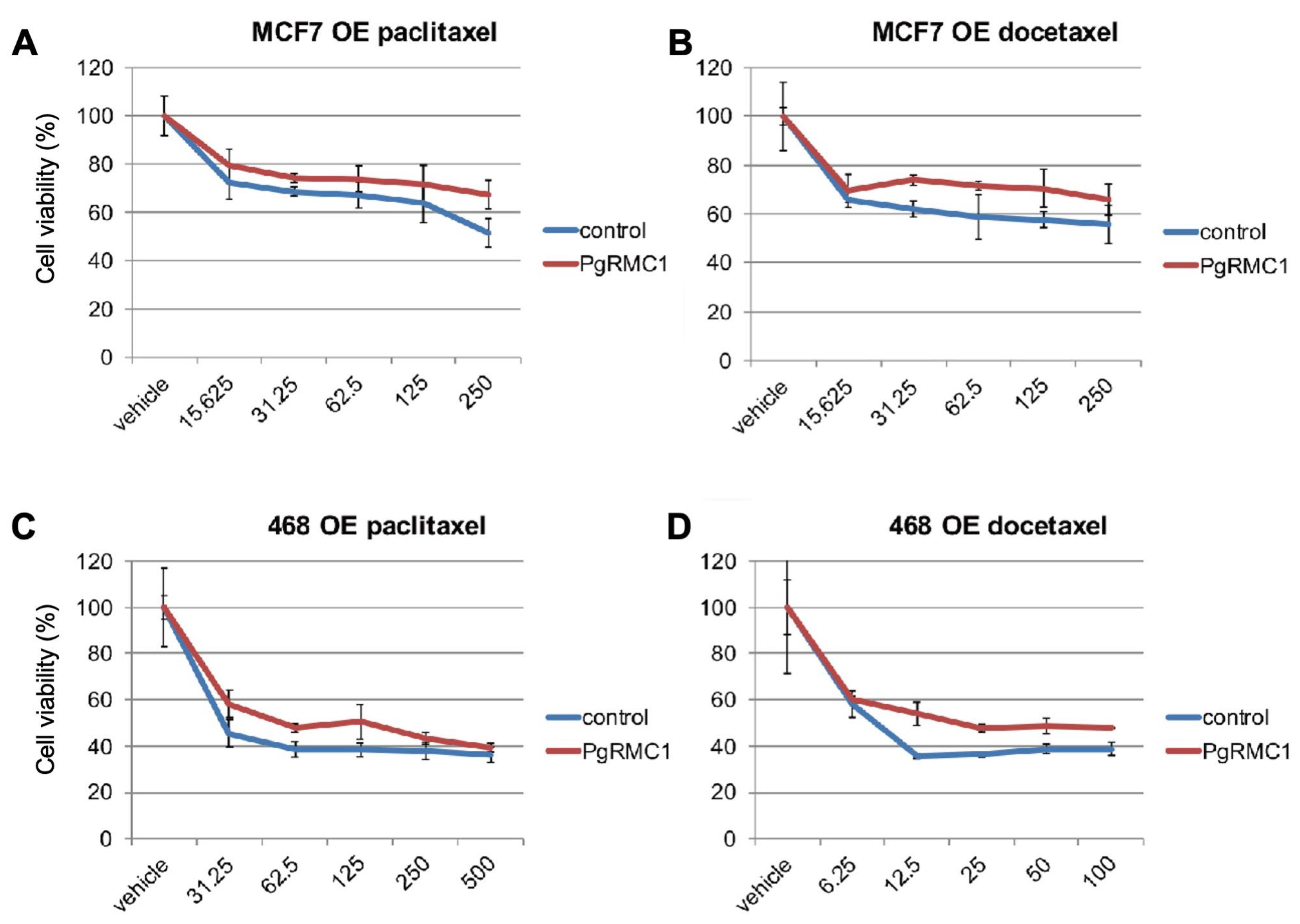

3.4. PgRMC1 Affects Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Luminal Differentiation in Breast Cancer Cell Lines

To explore whether PgRMC1 expression in breast cancer cells affects their sensitivity to chemotherapeutic drugs in vitro, we examined the effect of doxorubicin, paclitaxel, and docetaxel in cell lines transiently overexpressing PgRMC1 under E2 and progesterone supplemented conditions. Cell viability was measured by CCK-8 (WST-8) assays (

Figure 5A-D). PgRMC1 overexpression resulted in reduced sensitivity to chemotherapeutic drugs in MCF7 and MDA-MB468 cells.

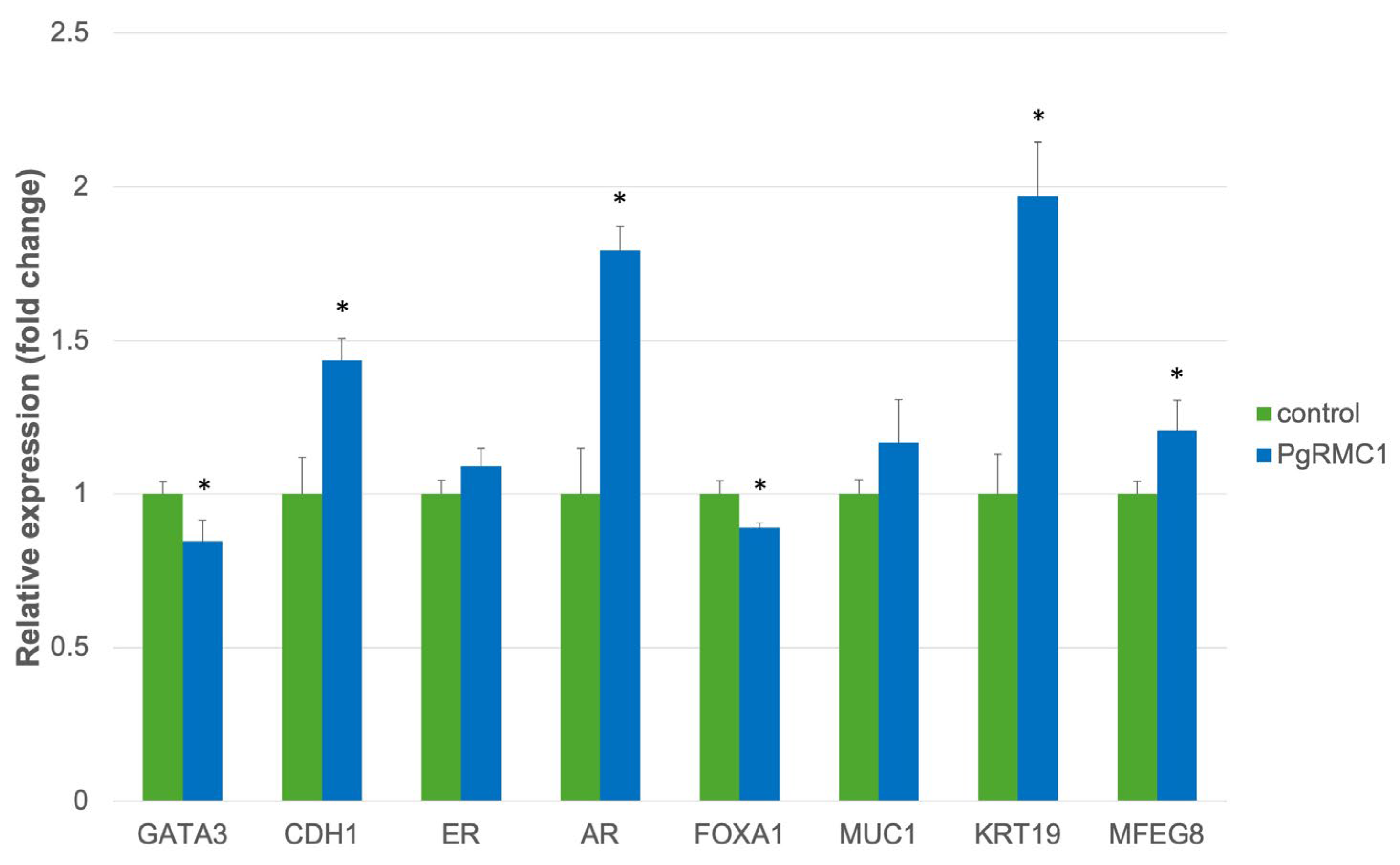

We further examined the effects of forced PgRMC1 expression on the gene expression profiles of MCF7 cells, focusing on mammary epithelial differentiation by real-time qPCR analyses (

Figure 6). PgRMC1 led to upregulation of genes such as CDH1, AR, KRT19, and MFGE8, and mild decrease in genes such as GATA3 and FOXA1, suggesting that PgRMC1 might suppress epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and promote mammary luminal epithelial differentiation.

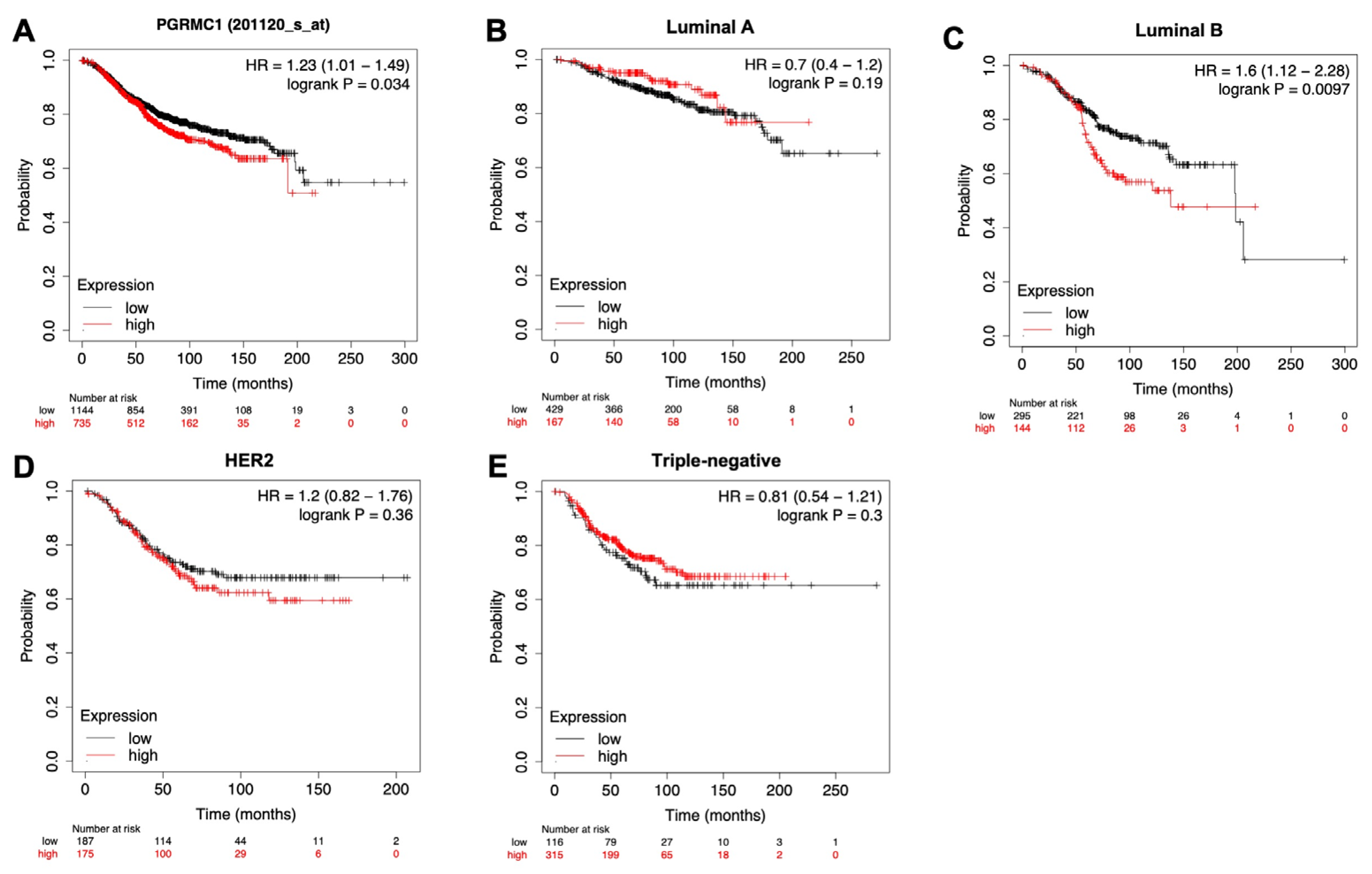

3.5. PgRMC1 Expression Levels Are Correlated with Overall Survival of Breast Cancer Patients

To examine whether PgRMC1 expression levels are correlated with the survival of breast cancer patients, we utilized the public online gene expression database named “Kaplan–Meier plotter (

http://kmplot.com/analysis/)” [

22]. Kaplan–Meier curves revealed a significant prolongation of survival of breast cancer patients with lower PgRMC1 expression in all subtypes, luminal A subtypes, and HER2 subtypes (

Figure 7A, B, and D). There was also a tendency towards prolonged survival in breast cancer patients with lower PgRMC1 expression such as luminal B and HER2 subtypes (

Figure 7C and D).

4. Discussion

We herein demonstrated that PgRMC1 expression levels are high in breast cancer tissues, which might be related to chemoresistance

in vivo, and that cancer cells with PgRMC1 overexpression can withstand treatment with chemotherapeutic drugs

in vitro. Progestogens, as well as estrogens, increase the risk of breast cancer. This risk might not only be dependent on the classical genomic mechanism of PgR but also involve non-classical progesterone-binding molecules such as PgRMC1 (

Figure 8).

In this study, PgRMC1 was observed in the cytoplasm and focally detected on the plasma membrane and perinuclear region of breast cancer specimens. In consistence, several studies have reported that PgRMC1 is more highly expressed in breast cancer cells than in benign or normal breast tissue [

12,

23,

24,

25,

26]. PgRMC1 is generally expressed in reproductive organs such as the ovary and placenta. The reason for its increased expression in breast cancer cells is not yet known. It is also possible that individuals with elevated PgRMC1 expression, potentially due to underlying sex hormone dysfunction, are at increased risk of developing breast cancer. We observed that PgRMC1 expression is not fully dependent on certain intrinsic breast cancer subtypes. The regulation of PgRMC1 expression remains a challenge.

PgRMC1 expression levels in the CNB specimens were significantly related to drug sensitivity in patients receiving NAC regimens, including anthracyclines and taxanes. Consistent with the clinical data, PgRMC1 overexpression induced chemoresistance in breast cancer cell lines, while knockdown of PgRMC1 with esiRNA recovered the sensitivity of cancer cells to anthracycline and paclitaxel. Several mechanisms have been suggested, including the hypotheses that PgRMC1 induces cancer cell proliferation [

12,

27,

28], protects cancer cells from anticancer drugs [

25,

29], and promotes the survival of cancer stem cells [

30]. PgRMC1, a heme-binding protein, interacts with P450 enzymes to facilitate sterol synthesis. This process might contribute to a protective effect against DNA damage caused by chemotherapeutic drugs [

31].

To delineate the mechanisms underlying PgRMC1-induced chemoresistance, we performed immunoblot analyses and real-time qPCR analyses focusing on EMT and differentiation markers [

17,

23,

25,

29]. We observed phosphorylation of ERK1/2 following PgRMC1 overexpression, while Akt phosphorylation was not significantly altered. PgRMC1 may induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation through interaction with membrane progesterone receptors (mPRs) and/or EGFR [

32,

33] (

Figure 8). In qPCR analyses, PgRMC1 induced the expression of some differentiation markers, such as CDH1, KRT19, and MFGE8, thus implying that PgRMC1 expression suppressed EMT and induced luminal epithelial differentiation

in vitro. This observation is consistent with previous reports that the pathological complete response (pCR) rate is very low in the well-differentiated luminal A subtype [

34,

35]. In addition, PgRMC1 induced the expression of AR in breast cancer cells. AR has been reported to be strongly associated with ER positivity and poor pathological response to NAC [

36].

To test our hypothesis that PgRMC1 expression is associated with poor outcomes in breast cancer patients, we analyzed data from the Kaplan-Meier Plotter, an online public database platform. Clinical data from this platform confirmed a correlation between higher PgRMC1 expression and poorer patient outcomes. Interestingly, the association between higher PgRMC1 expression and worse prognosis was particularly strong in intrinsic subtypes with inherently low PgR expression, such as luminal B and HER2-subtypes. This observation was further supported by data from another online public database platform, GEPIA (

http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/) [

26].

There are several limitations in this study. Only a limited number of clinical cases were analyzed, especially for NAC resistance. Clinical studies with more cases are needed to confirm the results of this study. As to in vitro experiments, we only used breast cancer cell lines under conventional culture conditions, and further analyses using spheroid culture, primary culture, or organoid culture of human breast cancer cells are needed.

Figure 8.

Classical and non-classical (alternative) progesterone signaling pathways are depicted.

Figure 8.

Classical and non-classical (alternative) progesterone signaling pathways are depicted.

5. Conclusions

In summary, our study showed that PgRMC1 expression is higher in breast cancer tissue and that PgRMC1 expression in CNB samples might predict resistance to NAC and that the expression of PgRMC1 confers chemotherapy resistance to breast cancer cells, partly due to PgRMC1-mediated EMT suppression and luminal differentiation. These results suggest that PgRMC1 is a putative biomarker for adjuvant chemotherapy sensitivity.

Author Contributions

M.T. performed histological, cytological, and biochemical experiments and analyzed and interpreted the data. T.C., T.U., and S.I. designed, analyzed, and interpreted the data. C.S. and T.K. performed histological and cytological analyses. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Funding

This work was partly supported by scholarship donations from Taiho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Eisai Co., Ltd, and Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd.

https://search.crossref.org/funding. Any errors may affect your future funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study protocol was conducted in accordance with the provisions of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, in line with the Ethical Guidelines for Epidemiological Research by the Japanese government and the Good Clinical Practice guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonization. All clinical experiments were approved by the internal review board of the Faculty of Medicine Research Committee at Kyorin University (approval number 287, 616).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Department of Breast Surgery and Pathology, Kyorin University Hospital, for their essential assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG). Polychemotherapy for early breast cancer:an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet 1998, 352, 930–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG). Relevance of breast cancer hormone receptors and other factors to the efficacy of adjuvant tamoxifen:patient-level meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet 2011, 378, 771–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boughey, J.C.; McCall, L.M.; Ballman, K.V.; Mittendorf, E.A.; Ahrendt, G.M.; Wilke, L.G.; Taback, B.; Leitch, A.M.; Morton, T.F.; Hunt, K.K. Tumor biology correlates with rates of breast-conserving surgery and pathologic complete response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer:findings from the ACOSOG Z1071(Alliance)Prospective Multicenter Clinical Trial. Ann. Surg. 2014, 260, 608–614;discussion 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mieog, J.S.; van der Hage, J.A.; van de Velde, C.J. (2007) Preoperative chemotherapy for women with operable breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2007, 2007, CD005002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group (EBCTCG). Long-term outcomes for neoadjuvant versus adjuvant chemotherapy in early breast cancer: Meta-analysis of individual patient data from ten randomised trials. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heil, J.; Kuerer, H.M.; Pfob, A.; Rauch, G.; Sinn, H.P.; Golatta, M.; Liefers, G.J.; Vrancken Peeters, M.J. Eliminating the breast cancer surgery paradigm after neoadjuvant systemic therapy: Current evidence and future challenges. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falkenstein, E.; Meyer, C.; Eisen, C.; Scriba, P.C.; Wehling, M. Full-length cDNA sequence of a progesterone membrane-binding protein from porcine vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996, 229, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, A.L.; Powell, D.W.; Bard, M.; Eckstein, J.; Barbuch, R.; Link, A.J.; Espenshade, P.J. Dap1/PGRMC1 binds and regulates cytochrome P450 enzymes. Cell Metab. 2017, 5, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cahill, M.A.; Jazayeri, J.A.; Catalano, S.M.; Toyokuni, S.; Kovacevic, Z.; Richardson, D.R. The emerging role of progesterone receptor membrane component 1 (PGRMC1) in cancer biology. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1866, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, H.; Chuang, T.D.; Luo, X.; Chegini, N. Endometrial miR-181a and miR-98 expression is altered during transition from normal into cancerous state and target PGR, PGRMC1, CYP19A1, DDX3X, and TIMP3. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 97, E1316–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H.W.; Ho, C.L.; Cheng, S.W.; Lin, Y.J.; Chen, C.C.; Cheng, P.N.; Yen, C.J.; Chang, T.T.; Chiang, P.M.; Chan, S.H.; Ho, C.H.; Chen, S.H.; Wang, Y.W.; Chow, N.H.; Lin, J.C. Progesterone receptor membrane component 1 as a potential prognostic biomarker for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 24, 1152–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubauer, H.; Ma, Q.; Zhou, J.; Yu, Q.; Ruan, X.; Seeger, H.; Fehm, T.; Mueck, A.O. Possible role of PGRMC1 in breast cancer development. Climacteric 2013, 16, 509–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, I.S.; Rohem, H.J.; Twist, K.E.; Craven, R.J. Pgrmc1 (progesterone receptor membrane component 1) associates with epidermal growth factor receptor and regulates erlotinib sensitivity. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 24775–24782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peluso, J.J.; Gawkowska, A.; Liu, X.; Shioda, T.; Pru, J.K. Progesterone receptor membrane component-1 regulates the development and Cisplatin sensitivity of human ovarian tumors in athymic nude mice. Endocrinology 2009, 150, 4846–4854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bali, N.; Arimoto, J.M.; Iwata, N.; Lin, S.W.; Zhao, L.; Brinton, R.D.; Morgan, T.E.; Finch, C.E. Differential responses of progesterone receptor membrane component-1 (Pgrmc1) and the classical progesterone receptor (Pgr) to 17ß-estradiol and progesterone in hippocampal subregions that support synaptic remodeling and neurogenesis. Endocrinology 2012, 153, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, C.; Cunningham, R.L.; Rybalchenko, N.; Singh, M. Progesterone increases the release of brain-derived neurotrophic factor from glia via progesterone receptor membrane component 1 (Pgrmc1)-dependent ERK5 signaling. Endocrinology 2012, 153, 4389–4400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabe, Y.; Nakane, T.; Koike, I.; Yamamoto, T.; Sugiura, Y.; Harada, E.; Sugase, K.; Shimamura, T.; Ohmura, M.; Muraoka, K.; Yamamoto, A.; Uchida, T.; Iwata, S.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Krayukhina, E.; Noda, M.; Handa, H.; Ishimori, K.; Uchiyama, S.; Kobayashi, T.; Suematsu, M. Haem-dependent dimerization of PGRMC1/Sigma-2 receptor facilitates cancer proliferation and chemoresistance. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, T.; Yamada, M.; Hashimoto, Y.; Sato, M.; Sasabe, J.; Kita, Y.; Terashita, K.; Aiso, S.; Nishimoto, I.; Matsuoka, M. Development of a femtomolar-acting humanin derivative named colivelin by attaching activity-dependent neurotrophic factor to its N terminus: Characterization of colivelin-mediated neuroprotection against Alzheimer's disease-relevant insults in vitro and in vivo. J. Neurosci. 2005, 25, 10252–10261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, K.H.; Hammond, M.E.H.; Dowsett, M.; McKernin, S.E.; Carey, L.A.; Fitzgibbons, P.L.; Hayes, D.F.; Lakhani, S.R.; Chavez-MacGregor, M.; Perlmutter, J.; Perou, C.M.; Regan, M.M.; Rimm, D.L.; Symmans, W.F.; Torlakovic, E.E.; Varella, L.; Viale, G.; Weisberg, T.F.; McShane, L.M.; Wolff, A.C. Estrogen and progesterone receptor testing in breast cancer: ASCO/CAP guideline update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 1346–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, T.; Yamada, M.; Sasabe, J.; Terashita, K.; Shimoda, M.; Matsuoka, M.; Aiso, S. Amyloid-beta causes memory impairment by disturbing the JAK2/STAT3 axis in hippocampal neurons. Mol. Psychiatry 2009, 14, 206–222 Epub 2008 Sep 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, A.; Lanczky, A.; Menyhart, O.; Gyorffy, B. Validation of miRNA prognostic power in hepatocellular carcinoma using expression data of independent datasets. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenhauer, E.A.; Therasse, P.; Bogaerts, J.; Schwartz, L.H.; Sargent, D.; Ford, R.; Dancey, J.; Arbuck, S.; Gwyther, S.; Mooney, M.; Rubinstein, L.; Shankar, L.; Dodd, L.; Kaplan, R.; Lacombe, D.; Verweij, J. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur. J. Cancer 2009, 45, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willibald, M.; Wurster, I.; Meisner, C.; Vogel, U.; Seeger, H.; Mueck, A.O.; Fehm, T.; Neubauer, H. High Level of Progesteron Receptor Membrane Component 1 (PGRMC 1) in Tissue of Breast Cancer Patients is Associated with Worse Response to Anthracycline-Based Neoadjuvant Therapy. Horm. Metab. Res. 2017, 49, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyorffy, B.; Lanczky, A.; Eklund, A.C.; Denkert, C.; Budczies, J.; Li, Q.; Szallasi, Z. An online survival analysis tool to rapidly assess the effect of 22,277 genes on breast cancer prognosis using microarray data of 1809 patients. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2010, 123, 725–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.T.; May, E.W.; Chang, J.F.; Hu, R.Y.; Wang, L.H.; Chan, H.L. PGRMC1 contributes to doxorubicin-induced chemoresistance in MES-SA uterine sarcoma. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2015, 72, 2395–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Ruan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Cai, G.; Ju, R.; Yang, Y.; Cheng, J.; Gu, M. Comprehensive Analysis of the Implication of PGRMC1 in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 22, 714030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neubauer, H.; Adam, G.; Seeger, H.; Mueck, A.O.; Solomayer, E.; Wallwiener, D.; Cahill, M.A.; Fehm, T. Membrane-initiated effects of progesterone on proliferation and activation of VEGF in breast cancer cells. Climacteric 2009, 12, 230–239. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.; Ludescher, M.; Poschmann, G.; Stühler, K.; Wyrich, M.; Oles, J.; Franken, A.; Rivandi, M.; Abramova, A.; Reinhardt, F.; Ruckhäberle, E.; Niederacher, D.; Fehm, T.; Cahill, M.A.; Stamm, N.; Neubauer, H. PGRMC1 Promotes Progestin-Dependent Proliferation of Breast Cancer Cells by Binding Prohibitins Resulting in Activation of ERα Signaling. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13, 5635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crudden, G.; Chitti, R.E.; Craven, R.J. Hpr6 (heme-1 domain protein) regulates the susceptibility of cancer cells to chemotherapeutic drugs. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006, 316, 448–455 doiorg/101124/jpet105094631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, K.K.; Stewart, R.; Napier, D.; Claudio, P.P.; Craven, R.J. PGRMC1 Elevation in Multiple Cancers and Essential Role in Stem Cell Survival. Adv. Lung Cancer (Irvine) 2015, 4, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohe, H.J.; Ahmed, I.S.; Twist, K.E.; Craven, R.J. PGRMC1 (progesterone receptor membrane component 1): A targetable protein with multiple functions in steroid signaling, P450 activation and drug binding. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 121, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, P. Membrane Progesterone Receptors (mPRs, PAQRs): Review of Structural and Signaling Characteristics. Cells 2022, 11, 1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wendler, A.; Wehling, M. Many or too many progesterone membrane receptors? Clinical implications. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 33, 850–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Minckwitz, G.; Untch, M.; Blohmer, J.U.; Costa, S.D.; Eidtmann, H.; Fasching, P.A.; Gerber, B.; Eiermann, W.; Hilfrich, J.; Huober, J.; Jackisch, C.; Kaufmann, M.; Konecny, G.E.; Denkert, C.; Nekljudova, V.; Mehta, K.; Loibl, S. Definition and impact of pathologic complete response on prognosis after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in various intrinsic breast cancer subtypes. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 1796–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lips, E.H.; Mulder, L.; de Ronde, J.J.; Mandjes, I.A.; Koolen, B.B.; Wessels, L.F.; Rodenhuis, S.; Wesseling, J. Breast cancer subtyping by immunohistochemistry and histological grade outperforms breast cancer intrinsic subtypes in predicting neoadjuvant chemotherapy response. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2013, 140, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loibl, S.; Muller, B.M.; von Minckwitz, G.; Schwabe, M.; Roller, M.; Darb-Esfahani, S.; Ataseven, B.; Bois, A.; Fissler-Eckhoff, A.; Gerber, B.; Kulmer, U.; Alles, J.U.; Mehta, K.; Denkertet, C. Androgen receptor expression in primary breast cancer and its predictive and prognostic value in patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2011, 130, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).