1. Introduction

Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer and a leading cause of cancer-related death in women, accounting for one in four cancer cases and one in six cancer deaths [

1]. Locally advanced breast cancer (LABC), a heterogeneous group defined by large tumors, regional lymph node involvement, or invasion of the chest wall or skin without distant metastasis, poses distinct clinical challenges [

2]. Its standard management involves neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC), which aims to downstage the tumor, enable breast-conserving surgery, and assess early treatment response [

3]. Achieving pathological complete response (pCR) after NAC correlates with better disease-free and overall survival, especially in triple-negative and HER-2 positive subtypes [

4,

5]; however, many patients respond poorly to NAC, resulting in worse outcomes [

6]. Therefore, identifying reliable predictive and prognostic biomarkers remains essential to guide therapy and improve prognosis.

The Hippo signaling pathway, a key regulator of organ size and tissue homeostasis, has emerged as a critical player in cancer biology due to its involvement in proliferation, survival, and therapeutic resistance [

7,

8]. At the center of this pathway is Yes-associated protein-1 (YAP1), a transcriptional coactivator that promotes oncogenic transcriptional programs when translocated into the nucleus via interaction with TEAD transcription factors [

7]. Aberrant activation of YAP1 has been implicated in the initiation and progression of various cancers, including lung, mesothelioma, gastric, and colorectal cancers, where it is associated with poor prognosis and resistance to targeted therapies [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13].

Beyond its oncogenic role, YAP1 has shown predictive value in neoadjuvant settings; its overexpression has been linked to worse outcomes in esophageal and prostate cancers following preoperative treatment [

14,

15]. These findings position YAP1 as a pan-cancer marker of treatment resistance and progression.

In breast cancer, YAP1 expression is particularly enriched in high-grade, hormone receptor-negative tumors, including triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) [

16,

17]. YAP1 contributes to chemoresistance by modulating anti-apoptotic pathways, drug efflux mechanisms, and cancer stem cell maintenance [

17,

18,

19]. Inhibition of YAP1 reverses taxane resistance in TNBC models, underscoring its role in sustaining drug tolerance [

18]. The upstream WISP1–YAP–TEAD4 axis has also been shown to drive chemoresistance, with its inhibition resulting in YAP inactivation and reduced tumor growth [

20]. Additionally, YAP1-driven transcriptional responses may enable tumor cells to adapt to chemotherapy-induced stress, particularly in the neoadjuvant context [

21].

On the other hand, novel strategies aimed at modulating Hippo pathway activity or disrupting YAP–TEAD interactions are currently under investigation and may offer a path toward personalized treatment approaches in aggressive breast cancer subtypes [

22,

23].

Given these contexts, this study aimed to evaluate YAP1 expression patterns in patients with LABC who received NAC and to investigate its association with clinicopathologic features and pathological treatment response. Specifically, the study assessed both pre- and post-NAC YAP1 expression levels to explore the potential impact of chemotherapy on YAP1 dynamics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

Seventy-three patients with LABC who were evaluated by a multidisciplinary tumor board and scheduled to receive neoadjuvant treatment between January 1, 2023 and January 1, 2025 were initially screened. Patients with complete medical records and available pre-treatment core biopsy and post-treatment surgical specimens were included in the final analysis. The exclusion criteria were being clinically node-negative at diagnosis, any history of cancer, and any history of immunosuppressive treatment.

Data were gathered from patient charts, including their age, histopathological type and molecular subtype, tumor location, initial and postoperative Ki-67 index, and the NAC regimen. All patients underwent surgery and analysis of surgical specimens following NAC.

The radiological staging was evaluated by the American Joint Committee on Cancer/Union for International Cancer Control version 8 [

2].

Pre-treatment core biopsy specimens were available and assessed for 50 patients who were enrolled in the study. Out of these 50 patients, post-NAC surgical specimens were accessible for only 30 patients due to pCR (n=11) or near-complete response (n=9).

2.2. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Protocol

The patients in the luminal group were treated with four cycles of adriamycin (60 mg/m²) combined with cyclophosphamide (600 mg/m²) (AC/EC) every two weeks, followed by 12 cycles of paclitaxel (80 mg/m²) administered weekly. Patients whose tumors were HER-2 positive received AC/EC followed by docetaxel with dual blockage (trastuzumab 8 mg/kg loading dose, followed by 6 mg/kg; pertuzumab 840 mg loading dose, followed by 420 mg; every three weeks). TNBC patients received four cycles of AC every two weeks, followed by 12 cycles of paclitaxel (80 mg/m²) with or without carboplatin 2 AUC on a weekly basis.

2.3. Pathological Evaluation

The histopathological classification was based on immunohistochemistry (IHC). Tumors were considered luminal if they were HER-2 negative and estrogen receptor (ER)-positive. Luminal A and B subtypes were distinguished by Ki-67 index, with luminal A defined as Ki-67 < 20% and luminal B as Ki-67 ≥ 20%. HER-2 positivity was assigned to cases with IHC 3+ or confirmed gene amplification by SISH. The Miller-Payne regression score assessed the pCR in histopathological specimens, where a pCR was characterized by the absence of residual invasive cancer in breast tissue, corresponding to the Miller-Payne score [

24].

2.4. Immunohistochemical Evaluation of YAP1 Expression

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded breast carcinoma tissue samples—including both tru-cut biopsies and post-neoadjuvant resection specimens—were sectioned at 3 μm thickness. After incubation at 60°C for 1 hour, slides were deparaffinized with xylene and rehydrated through graded ethanol series. Antigen retrieval was performed using a 1:10 diluted citrate buffer (pH 6.0) in a PT module. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked using 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 minutes, followed by protein blocking. Sections were incubated with primary anti-YAP1 antibody (Bio SB, BSB-146, 1:50 dilution) for 2 hours at room temperature. Detection was achieved using a polymer-based detection system with enhancer and HRP polymer steps, and visualization was performed using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) chromogen. Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted with Entellan. All immunohistochemical staining was carried out using the Sequenza automated IHC system.

As shown in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, a blinded pathologist evaluated YAP1 expression under 400× magnification. Both nuclear and cytoplasmic staining were assessed, with internal control based on the staining intensity of myoepithelial and luminal cells within terminal duct lobular units.

The AUC for nuclear expression was 0.569 (95% CI: 0.405–0.733; p = 0.411), and for cytoplasmic expression was 0.483 (95% CI: 0.318–0.649; p = 0.843). Despite the lack of statistical significance in univariate ROC curves, we identified optimal dichotomization thresholds (≥70% for nuclear, ≥80% for cytoplasmic) based on their combined association with axillary pCR in bivariate analyses. Hence, tumors with ≥70% nuclear and ≥80% cytoplasmic staining were categorized as YAP1-positive. However, due to the limited availability of post-treatment tissue in cases of complete or near-complete pathological response, ROC-based cutoff determination was not feasible for post-treatment specimens. Therefore, post-treatment YAP1 expression data were analyzed as continuous variables without categorization.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 24 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic and clinicopathological data. The distribution of continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Since none of the continuous variables followed a normal distribution, non-parametric tests were applied for all relevant analyses. Associations between categorical variables were evaluated using Pearson’s chi-square test/Fisher’s exact test. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare continuous variables between independent groups. Pre- and post-treatment changes in YAP1 expression were assessed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for paired samples. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was conducted to define optimal cutoff values for YAP1 expression predicting the pCR status in breast and axillary tissue. A two-tailed p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

A total of 50 patients with LABC were included, with a median age of 49.5 years (range, 24–72). Among them, 24 (48%) were premenopausal. 27 patients (54.0%) had hormone receptor (HR) positive/HER-2 negative tumors (luminal type). Seven patients (14.0%) exhibited co-expression of hormone receptors and HER-2 (HR positive/HER-2 positive), seven patients (14.0%) had HER-2 enriched tumors (HER-2 positive/HR negative), while nine patients (18.0%) were classified as TNBC (

Table 1).

In our cohort, YAP1 positivity was observed in 1 out of 27 patients (3.7%) with HR positive/HER-2 negative tumors (luminal type). In contrast, YAP1 expression was detected in 5 out of 7 patients (71.4%) with HR positive/HER-2 positive tumors and in 1 out of 7 patients (14.3%) with HER-2 enriched tumors. Among patients with triple-negative breast cancer, 2 out of 9 patients (22.2%) exhibited YAP1 positivity (p=0.001). Pre-treatment YAP1 expression was present in 6 HER-2 positive and 3 HER-2 negative tumors, while none of the HER-2 low tumors showed YAP1 positivity (p=0.01) (

Table 2).

Following NAC, 20 patients (40%) achieved axillary pCR and 11 achieved breast pCR. The post-NAC final pathology report revealed that 25 (50.0%) had lymphatic invasion and 23 (46.0%) had vascular invasion.

YAP1 positivity significantly predicted axillary pCR (OR = 7.54, 95% CI: 1.37–41.41; p = 0.01). In YAP1-positive patients, 77.8% achieved axillary pCR compared to 31.7% in YAP1-negative patients, though the YAP1 status and breast pCR association were insignificant.

As shown in

Table 2, among patients with YAP1-positive tumors, 4 out of 9 (44.4%) achieved breast pCR, compared to 7 out of 41 (17.1%) in the YAP1-negative group, which showed a trend toward higher pCR rates in YAP1-positive tumors (OR = 3.89, 95% CI: 0.83–18.24; p = 0.07).

Breast pCR was achieved in 8 premenopausal and three postmenopausal patients, while 16 and 23 patients in each group, respectively, did not achieve pCR (p=0.06) (

Table 1).

Lymph node invasion was present in 23 of YAP1-negative patients (62.2%) and in 2 of YAP1-positive patients (22.2%) (p=0.03). Vascular invasion was observed in 22 of YAP1-negative patients (59.5%) and in 1 of YAP1-positive patients (11.1%) (p=0.009).

As expected, breast pCR rates significantly differed among breast cancer subtypes (p=0.001). Among patients with a luminal tumor type, only 1 out of 27 (3.7%) achieved pCR, whereas higher pCR rates were observed in the luminal/HER-2 co-expressing (5/7; 71.4%), HER-2 only (3/7; 42.9%), and triple-negative (2/9; 22.2%) subtypes.

The Mann-Whitney U test indicated that higher Ki-67 values were significantly associated with positive pre-NAC YAP1 expression (p=0.028). In contrast, there was no association between ER, progesterone receptor (PR) status and tumor size (all p values > 0.05) (

Table 2). Pre-NAC YAP 1 expression also was not associated with pre-T (p=0.8) and N status (p=0.6).

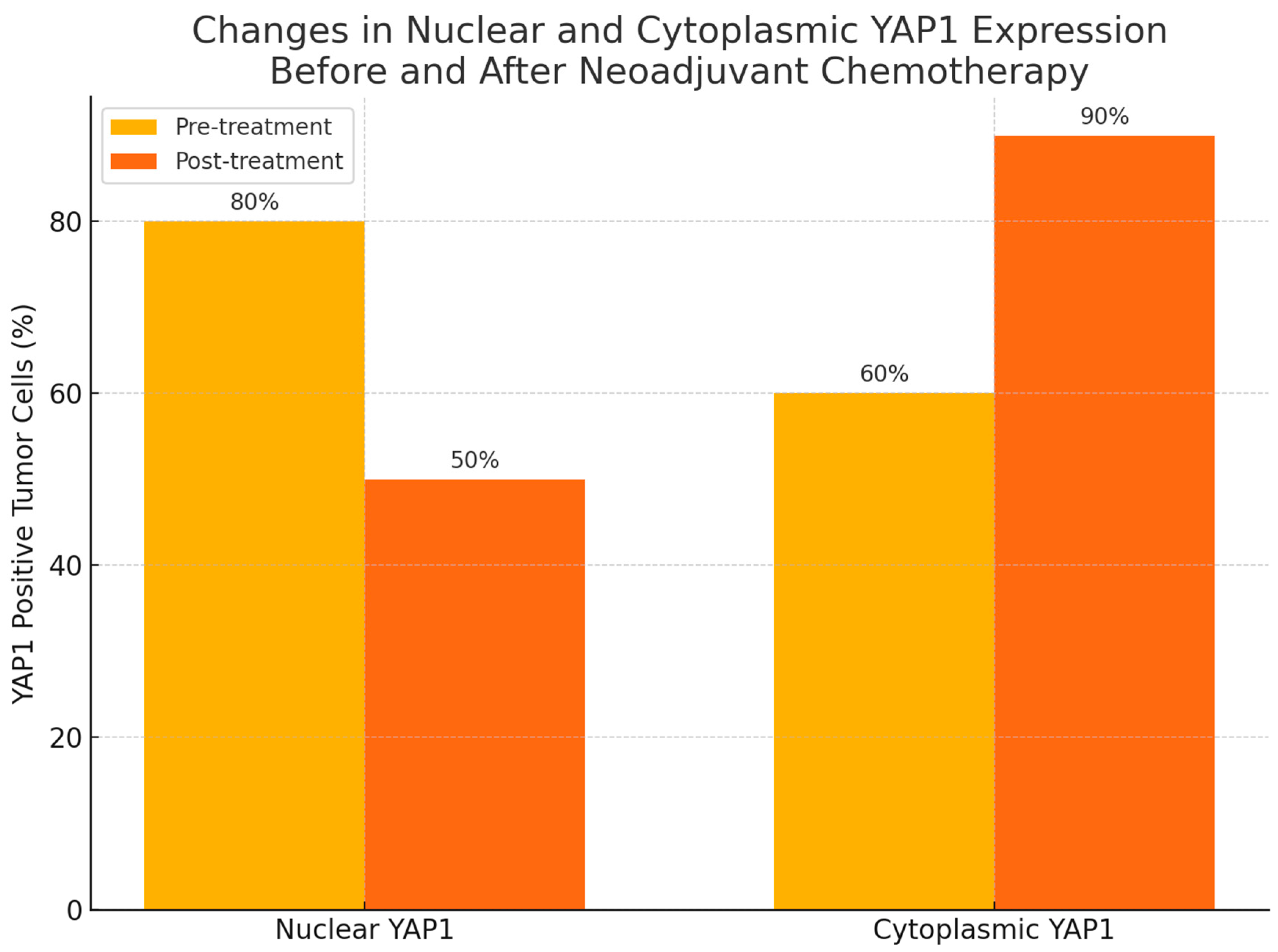

Following treatment, there was a statistically significant change in YAP1 expression, with nuclear staining decreasing (p=0.004) while cytoplasmic staining increased (p=0.002), as shown in

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5. Post-NAC YAP1 expression did not show significant correlation with ER, PR or Ki-67 (all p values > 0.1).

4. Discussion

YAP1 is a key protein in the Hippo pathway that supports cancer growth and survival, particularly in aggressive breast cancers like triple-negative tumors [

7,

8,

16]. Its increased expression is linked to poor response to chemotherapy, making it a potential marker for treatment resistance and a target for new therapies [17, 20-22]. This study primarily aimed to determine the clinical relevance of YAP1 by examining its association with key clinicopathologic parameters and pathological treatment response and to explore the impact of neoadjuvant chemotherapy on YAP1 expression by comparing its levels in pre- and post-treatment tumor tissues of patients with LABC.

Several previous studies have concluded with conflicting results regarding the prognostic and predictive role of YAP1 in breast cancer; Cha et al. demonstrated that high nuclear YAP1 expression was associated with HR negativity, increased Ki-67 index, lymph node metastasis, and inferior distant metastasis-free and disease-free survival (DFS), particularly in TNBC patients (HR for DFS: 3.208, p=0.0105; HR for DMFS: 2.384, p=0.0367) [

16]. Similarly, Ding et al. reported that high nuclear and total YAP expression in primary breast tumors predicted worse DFS in TNBC and was identified as an independent prognostic factor in multivariate models [

25]. In contrast, Cao et al. showed that YAP1 was mainly expressed in luminal A tumors and associated with favorable prognosis, including improved DFS in luminal subgroups [

26]. These discrepancies may reflect subtype-specific roles of YAP1, as also highlighted in the meta-analysis by Li et al., which showed that YAP expression was significantly higher in TNBC compared to normal tissue (OR: 18.23, p<0.001), while non-TNBC tumors exhibited lower YAP1 positivity (OR: 0.15, p<0.001) [

27]. In our study, we demonstrated that YAP1 positivity was significantly associated with axillary pathological complete response (p=0.01), HER-2 enriched tumor subtype (p=0.001), and high Ki-67 index (p=0.028). YAP1 expression was most frequently detected in luminal/HER-2 and HER-2 only tumors and least in the luminal A subtype.

In terms of therapeutic response, the current evidence supports a potential role of YAP1 in chemoresistance across different tumor types. Yuan et al. demonstrated that YAP1 overexpression was associated with poor neoadjuvant chemotherapy response in TNBC, mediated via the MMP7/CXCL16 axis. In this model, YAP1 upregulation suppressed CXCL16-driven CD4+/CD8+ TIL recruitment and increased MMP7 expression, resulting in elevated RCB scores and reduced tumor remission [

21]. Similarly, Vici et al. reported that while YAP or TAZ alone did not impact pathological response, the combined expression of YAP in both tumor and stromal compartments was independently associated with decreased likelihood of achieving pCR (OR: 7.13, p = 0.029) and shorter disease-free survival (HR: 3.07, p = 0.016) in TNBC patients [

28]. Furthermore, in a chemohormonal setting, Matsuda et al. observed that elevated nuclear YAP1 in residual tumor tissue after neoadjuvant docetaxel-based therapy in prostate cancer was an independent predictor of biochemical recurrence [

15]. On the other hand, a prior study by Isaogullari et al. failed to demonstrate a significant association between YAP and pCR [

29]. In our study, while the association between YAP1 and breast pCR did not reach statistical significance, a trend toward higher pCR rates in YAP1-positive tumors was noted (44.4% vs. 17.1%, p=0.07). The reason for not achieving pCR in breast tissue might be explained by the molecular heterogeneity and limited sample size. Another explanation might be the role of YAP1 in regulating cell motility, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), and cytoskeletal remodeling. YAP1-driven EMT programs and integrin signaling may enhance tumor cell plasticity and promote clearance of micrometastases, particularly from lymphatic compartments (30-33). This mechanistic axis could partially explain the differential impact of YAP1 on axillary versus breast pCR observed in our cohort.

Breast pCR rates were highest in luminal/HER-2 (71.4%) and HER-2 positive (42.9%) subtypes, consistent with the distribution of YAP1 positivity and supporting its link with treatment response in these groups. These findings are in line with those reported by Goktas Aydin et al., who observed pCR rates of 3.7% in luminal A, 21.1% in luminal B/HER-2 positive, 24.7% in HER-2 positive/ER negative, and 32.9% in TNBC subtypes (p < 0.001)

[34]. Although not statistically significant (p=0.06), breast pCR tended to be higher in premenopausal patients, suggesting a possible influence of hormonal status on treatment response.

Interestingly, in our study, YAP1 negativity was associated with more aggressive pathological features post-NAC, including significantly higher rates of lymphatic and vascular invasion. This finding aligns with emerging evidence suggesting that nuclear YAP1 activity may exert a tumor-suppressive role by maintaining epithelial integrity. Cordenonsi et al. demonstrated that nuclear YAP1 preserves epithelial architecture, and its loss triggers epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and enhances invasive behavior [

17]. Similarly, studies by Barry et al. and Zhou et al. highlighted that cytoplasmic retention of YAP1 correlates with increased motility, invasion, and impaired cell-cell adhesion, promoting tumor progression [

35,

36].

Kim et al. showed that nuclear YAP expression was significantly correlated with high Ki-67 in colorectal adenocarcinoma (p=0.002), while cytoplasmic YAP expression showed an inverse relationship [

37]. In contrast, Cao et al. reported an inverse correlation between YAP and Ki-67 expression in breast cancer, where YAP positivity was more frequent in luminal A tumors with low proliferative index [

26]. Our results also demonstrated a significant association between high Ki-67 index and YAP1 positivity (p=0.028), suggesting a potential link between YAP1 activity and proliferative capacity in breast tumors. Due to the small sample size, this correlation was not observed in the post-treatment setting.

In our cohort, neoadjuvant chemotherapy led to a statistically significant decrease in nuclear YAP1 expression (p=0.004) and a concomitant increase in cytoplasmic localization (p=0.002), suggesting dynamic spatial modulation of YAP1 in response to treatment. This shift may reflect altered transcriptional activity and therapeutic vulnerability. Pharmacologic inhibitors such as verteporfin, which disrupt the YAP–TEAD interaction, have shown efficacy across multiple breast cancer subtypes [

38], while upstream modulators like RNF187 have been proposed as potential targets in triple-negative disease [

39]. The strong association between pre-treatment YAP1 expression and HER-2 positive subtype in our study further supports its relevance as both a biomarker of response and a candidate for molecular targeting, particularly in aggressive tumor types.

YAP1 expression was associated with greater nodal clearance, particularly in HER-2 positive tumors. Although previous studies have linked YAP1 to chemoresistance and poor outcomes, especially in triple-negative or basal-like breast cancer, our findings suggest that YAP1 may exert context-dependent effects. In HER-2 positive tumors, YAP1 may enhance HER-2 driven signaling and increase chemosensitivity through PI3K/AKT/mTOR modulation [

27,

28]. Conversely, in TNBC, YAP1 overexpression has been associated with EMT and stem-like phenotypes that promote therapeutic resistance [

29].

Despite the novel insights provided, our study has several limitations. First, the relatively small sample size, particularly for post-treatment surgical specimens (n=30), may have limited the statistical power for some subgroup analyses and reduced the ability to draw definitive conclusions about post-treatment expression patterns. This study did not assess survival, which could represent another limitation. While post-treatment YAP1 expression could not be dichotomized due to the limited availability of residual tumor tissue, this did not undermine our primary aim, which was to evaluate the chemotherapy-induced change in YAP1 localization. The functional assays were not performed to confirm that cytoplasmic retention of YAP1 reflects transcriptional inactivation, nor were dynamic changes in YAP1 localization correlated with downstream target gene expression. However, if validated in larger cohorts, YAP1 immunohistochemistry could be integrated into routine diagnostic workflows utilizing pre-treatment core biopsy specimens. In HER-2 positive breast cancer, high YAP1 expression may serve as a surrogate marker of nodal chemosensitivity, potentially informing surgical decision-making or the intensity of axillary management.

5. Conclusions

Our findings suggest that YAP1 expression, particularly its subcellular localization, may serve as a promising predictive biomarker in patients with locally advanced breast cancer undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The association between pre-treatment YAP1 positivity and axillary pCR, along with the observed shift from nuclear to cytoplasmic localization post-treatment, underscores YAP1's potential role in modulating therapeutic response. Furthermore, the higher incidence of lymphovascular invasion in YAP1-negative tumors may indicate a distinct biological behavior of residual disease. Further functional studies are warranted to determine whether this shift correlates with reduced oncogenic transcriptional output and whether such changes can be therapeutically exploited in YAP1-expressing breast cancers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.E., S.G.A.; methodology, O.E., S.G.A.; software, O.E.; validation, S.G.A., M.A.; formal analysis, A.A.; investigation, O.E., O.Y., T.E. and S.D.; resources, O.E.; data curation, O.E., O.Y., S.G.A., S.D. and T.E.; writing original draft preparation, O.E.; writing review and editing, O.E, S.G.A.; Pathologic evaluation: T.E. visualization, O.E. A.A., and S.G.A.; supervision, S.G.A., M.A.; project administration, O.E., S.G.A., T.E., O.Y., A.A., S.D. and M.A.; funding acquisition, O.E., O.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding Statement: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was carried out in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients or their caregivers. The Local Ethics Committee of Istanbul Medipol University approved the study (decision date: February 2, 2025, number: E-10840098-202.3.02-1391).

Informed Consent Statement

All subjects provided written informed consent after getting a comprehensive explanation to participate in the study.

Data availability statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| LABC |

Locally advanced breast cancer |

| NAC |

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy |

| pCR |

Pathological complete response |

| YAP1 |

Yes-associated protein-1 |

| TNBC |

Triple-negative breast cancer |

| IHC |

Immunohistochemistry |

| ER |

Estrogen receptor |

| HR |

Hormone receptor |

| PR |

Progesterone receptor |

| ROC |

Receiver operating characteristic |

| OR |

Odds ratio |

| DFS |

Disease-free survival |

| OS |

Overall survival |

| EMT |

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition |

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024, 74, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.B.; Greene, F.L.; Edge, S.B.; Compton, C.C.; Gershenwald, J.E.; Brookland, R.K.; et al. The Eighth Edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more "personalized" approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017, 67, 93–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortazar, P.; Zhang, L.; Untch, M.; Mehta, K.; Costantino, J.P.; Wolmark, N.; et al. Pathological complete response and long-term clinical benefit in breast cancer: the CTNeoBC pooled analysis. Lancet. 2019, 393, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Minckwitz, G.; Untch, M.; Blohmer, J.U.; Costa, S.D.; Eidtmann, H.; Fasching, P.A.; et al. Definition and impact of pathologic complete response on prognosis after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in various intrinsic breast cancer subtypes. J Clin Oncol. 2012, 30, 1796–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, D.; Sagona, A.; De Carlo, C.; Fernandes, B.; Barbieri, E.; Di Maria Grimaldi, S. Pathologic response and residual tumor cellularity after neoadjuvant chemotherapy predict prognosis in breast cancer patients. Breast. 2023, 69, 323–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Yoo, T.K.; Lee, S.B.; Kim, J.; Chung, I.Y.; Ko, B.S.; et al. Prognostic value of residual cancer burden after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer: a comprehensive subtype-specific analysis. Sci Rep. 2025, 15, 13977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.X.; Zhao, B.; Guan, K.L. Hippo Pathway in Organ Size Control, Tissue Homeostasis, and Cancer. Cell. 2015, 163, 811–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanconato, F.; Cordenonsi, M.; Piccolo, S. YAP/TAZ at the Roots of Cancer. Cancer Cell. 2016, 29, 783–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Chen, M.; Wang, M. Hippo pathway in non-small cell lung cancer: mechanisms, potential targets, and biomarkers. Cancer Gene Ther 2024, 31, 652–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhong, H.; Shi, Q.; Ruan, R.; Huang, C.; Wen, Q.; et al. YAP1-CPNE3 positive feedback pathway promotes gastric cancer cell progression. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2024, 81, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Fan, L.; Tang, J.; Chen, S.; Du, G.; Zhang, N. Advances in research on the carcinogenic mechanisms and therapeutic potential of YAP1 in bladder cancer (Review). Oncol Rep. 2025, 53, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Shang, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, R. YAP1 expression in colorectal cancer confers the aggressive phenotypes via its target genes. Cell Cycle. 2024, 23, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Dai, Y.J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z. YAP1 activates SLC2A1 transcription and augments the malignant behavior of colorectal cancer cells by activating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Cell Div. 2025, 20, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Shao, Y.W.; Tong, X.; Wu, X.; Pang, J.; Feng, A.; et al. YAP1 amplification as a prognostic factor of definitive chemoradiotherapy in nonsurgical esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 1628–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, Y.; Narita, S.; Nara, T.; Mingguo, H.; Sato, H.; Koizumi, A.; et al. Impact of nuclear YAP1 expression in residual cancer after neoadjuvant chemohormonal therapy with docetaxel for high-risk localized prostate cancer. BMC Cancer. 2020, 20, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, Y.J.; Bae, S.J.; Kim, D.; Ahn, S.G.; Jeong, J.; Koo, J.S.; et al. High Nuclear Expression of Yes-Associated Protein 1 Correlates with Metastasis in Patients With Breast Cancer. Front Oncol. 2021, 11, 609743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordenonsi, M.; Zanconato, F.; Azzolin, L.; Forcato, M.; Rosato, A.; Frasson, C.; et al. The Hippo transducer TAZ confers cancer stem cell-related traits on breast cancer cells. Cell. 2011, 147, 759–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wei, X.; Zhang, S.; Song, Z.; Chen, X.; et al. Role of inhibitor of yes-associated protein 1 in triple-negative breast cancer with taxol-based chemoresistance. Cancer Sci. 2019, 110, 561–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.D.K.; Yi, C. YAP/TAZ Signaling and Resistance to Cancer Therapy. Trends Cancer. 2019, 5, 283–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, T.; Liu, L.; You, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, F.; Li, S.; et al. WISP1 inhibition of YAP phosphorylation drives breast cancer growth and chemoresistance via TEAD4 activation. Anticancer Drugs. 2025, 36, 157–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.Q.; Zhang, K.J.; Wang, S.M.; Guo, L. YAP1/MMP7/CXCL16 axis affects efficacy of neoadjuvant chemotherapy via tumor environment immunosuppression in triple-negative breast cancer. Gland Surg. 2021, 10, 2799–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Zou, H.; Guo, Y.; Tong, T.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, Y.; et al. The oncogenic roles and clinical implications of YAP/TAZ in breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2023, 128, 1611–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.Q.; Ding, N.H.; Xiao, Z. The Hippo Transducer YAP/TAZ as a Biomarker of Therapeutic Response and Prognosis in Trastuzumab-Based Neoadjuvant Therapy Treated HER-2 Positive Breast Cancer Patients. Front Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 537265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sejben, A.; Kószó, R.; Kahán, Z.; Cserni, G.; Zombori, T. Examination of Tumor Regression Grading Systems in Breast Cancer Patients Who Received Neoadjuvant Therapy. Pathol Oncol Res. 2020, 26, 2747–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, N.; Huang, T.; Yuan, J.; Mao, J.; Duan, Y.; Liao, W.; et al. Yes-associated protein expression in paired primary and local recurrent breast cancer and its clinical significance. Curr Probl Cancer. 2019, 43, 429–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Sun, P.L.; Yao, M.; Jia, M.; Gao, H. Expression of YES-associated protein (YAP) and its clinical significance in breast cancer tissues. Hum Pathol. 2017, 68, 166–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Luo, J.; Fang, J.Y.; Zhang, R.; Ma, J.B.; Zhu, Z.P. Expression characteristics of the yes-associated protein in breast cancer: A meta-analysis. Medicine 2022, 101, e30176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vici, P.; Ercolani, C.; Di Benedetto, A.; Pizzuti, L.; Di Lauro, L.; Sperati, F.; et al. Topographic expression of the Hippo transducers TAZ and YAP in triple-negative breast cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2016, 35, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaogullari, S.Y.; Topal, U.; Ozturk, F.; Gok, M.; Oz, B.; Akcan, A.C. The relationship of patients, giving or not giving a pathological full response, with YAP (Yes Associated Protein) in breast cancer cases to which neo-adjuvant chemotherapy is applied. Ann Ital Chir. 2022, 92, 263–70. [Google Scholar]

- Khalil, A.A.; Smits, D.; Haughton, P.D.; Koorman, T.; Jansen, K.A.; Verhagen, M.P.; et al. A YAP-centered mechanotransduction loop drives collective breast cancer cell invasion. Nat Commun. 2024, 15, 4866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Es, H.A.; Cox, T.R.; Sarafraz-Yazdi, E.; Thiery, J.P.; Warkiani, M.E. Pirfenidone Reduces Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Spheroid Formation in Breast Carcinoma through Targeting Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts (CAFs). Cancers 2021, 13, 5118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Huang, Q.; Jia, W.; Feng, S.; Liu, L.; Li, X.; et al. YAP1 induces invadopodia formation by transcriptionally activating TIAM1 through enhancer in breast cancer. Oncogene. 2022, 41, 3830–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, G.R.; Sethi, I.; Sadida, H.Q.; Rah, B.; Mir, R.; Algehainy, N.; et al. Cancer cell plasticity: from cellular, molecular, and genetic mechanisms to tumor heterogeneity and drug resistance. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2024, 43, 197–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goktas Aydin, S.; Bilici, A.; Olmez, O.F.; Oven, B.B.; Acikgoz, O.; Cakir Tet, a.l. The Role of 18F-FDG PET/CT in Predicting the Neoadjuvant Treatment Response in Patients with Locally Advanced Breast Cancer. Breast Care (Basel). 2022, 17, 470–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, E.R.; Morikawa, T.; Butler, B.L.; Shrestha, K.; de la Rosa, R.; Yan, K.S.; et al. Restriction of intestinal stem cell expansion and the regenerative response by YAP. Nature. 2013, 493, 106–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Hu, T.; Xu, Z.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Feng, T.; et al. Targeting Hippo pathway by specific interruption of YAP-TEAD interaction using cyclic YAP-like peptides. FASEB J. 2017, 31, 1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, O.J.; Huang, S.M.; Kwon, J.L.; Kim, J.M.; et al. Differential expression of Yes-associated protein and phosphorylated Yes-associated protein is correlated with expression of Ki-67 and phospho-ERK in colorectal adenocarcinoma. Histol Histopathol. 2013, 28, 1483–90. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, C.; Li, X. Verteporfin inhibits cell proliferation and induces apoptosis in different subtypes of breast cancer cell lines without light activation. BMC Cancer. 2020, 20, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Kong, Q.; Su, P.; Duan, M.; Xue, M.; Li, X.; et al. Regulation of Hippo signaling and triple negative breast cancer progression by an ubiquitin ligase RNF187. Oncogenesis. 2020, 9, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).