Submitted:

10 June 2024

Posted:

12 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Design

2.1. Patients

3. Procedure

3.1. Sample Preparation

3.2. UHPLC and HRMS

3.3. Metabolomic Data Analysis

4. Results

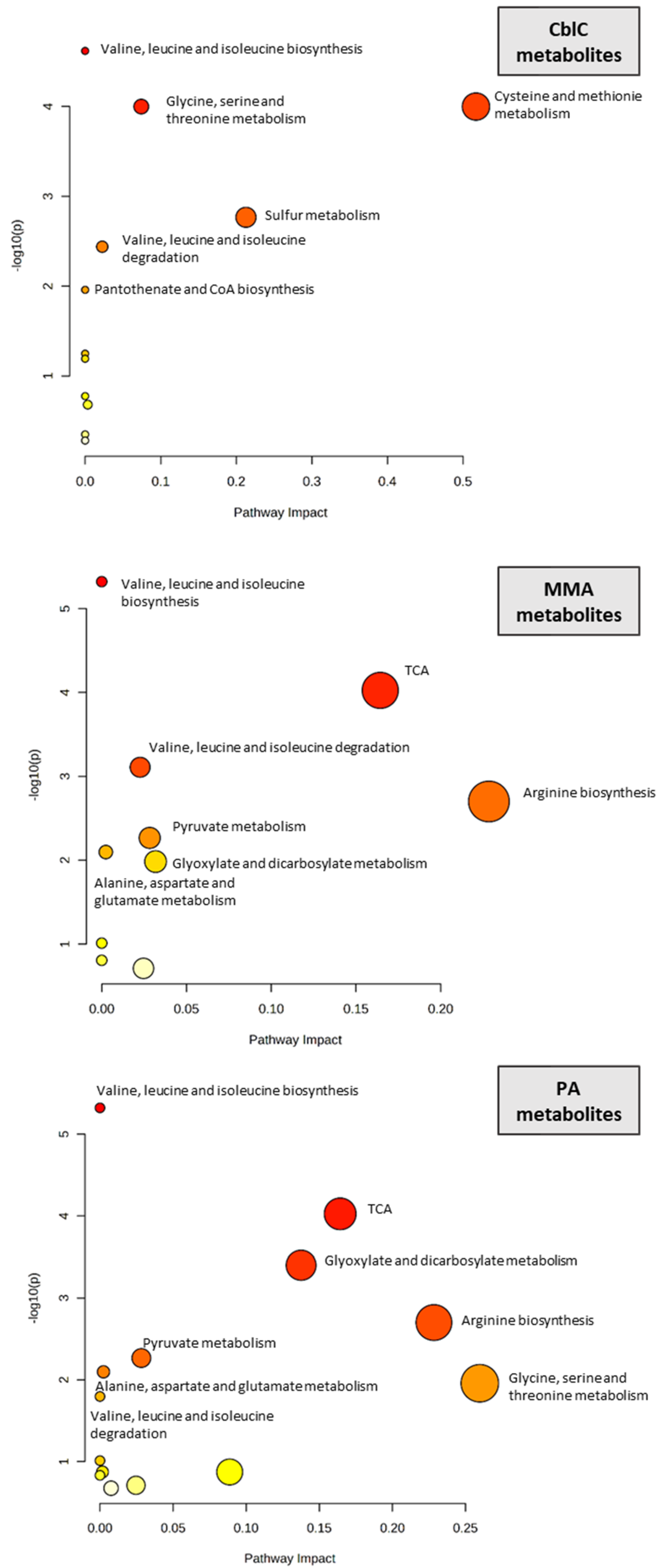

4.1. Significantly Different Metabolites

4.1.1. Organic Acids and Ketones

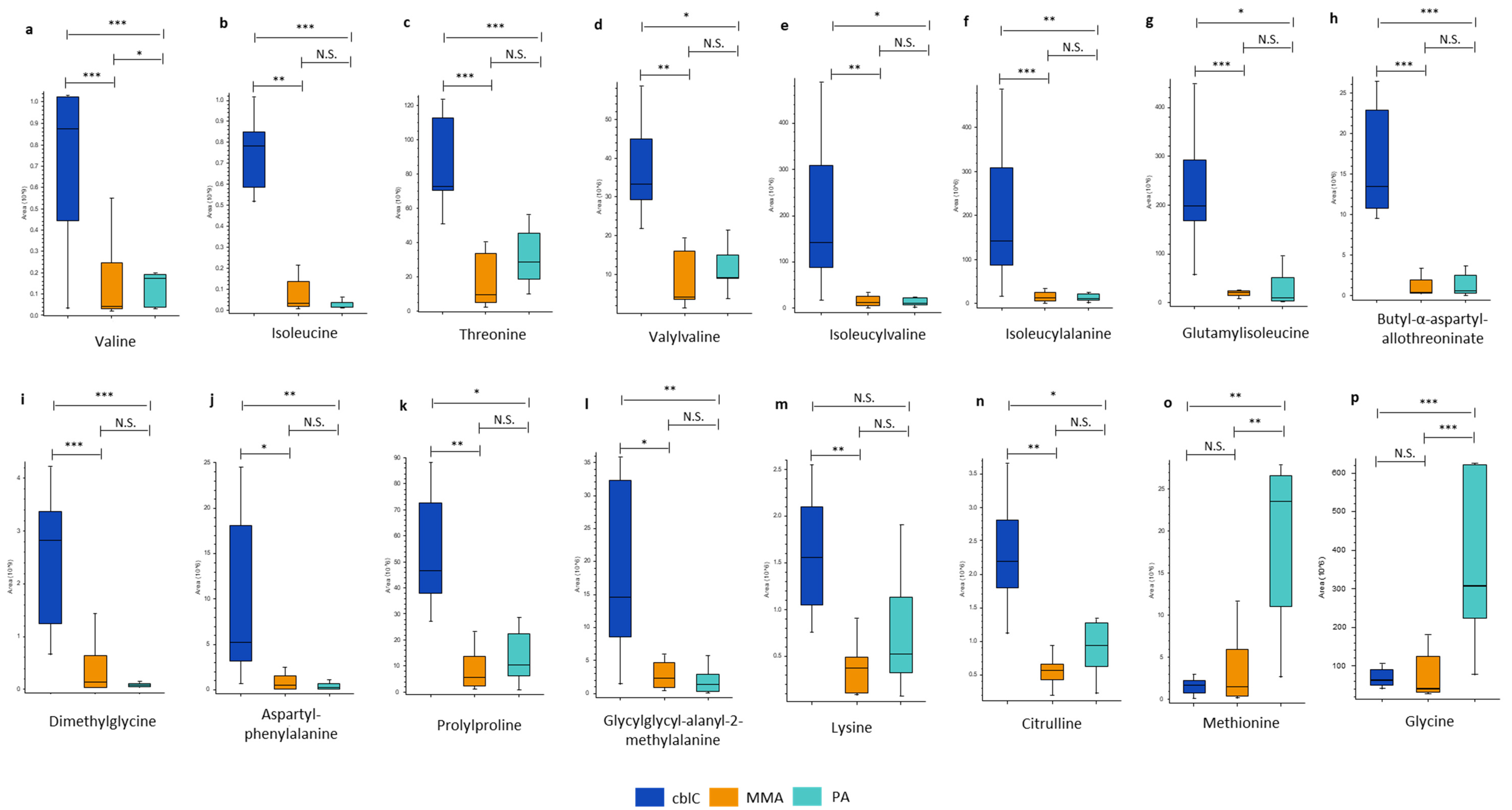

4.1.2. Amino Acids and Peptides

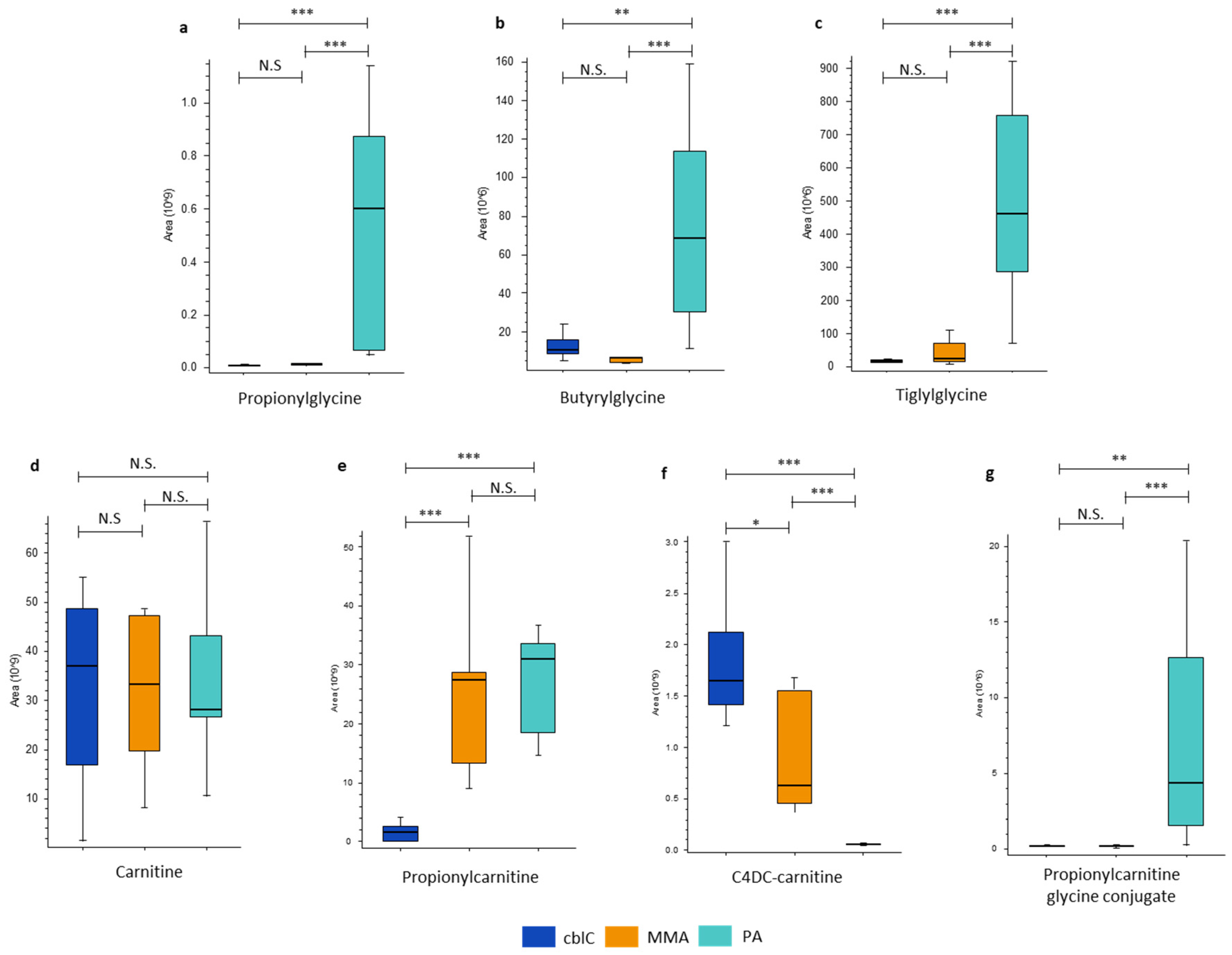

4.1.3. Glycine and Carnitine Conjugates

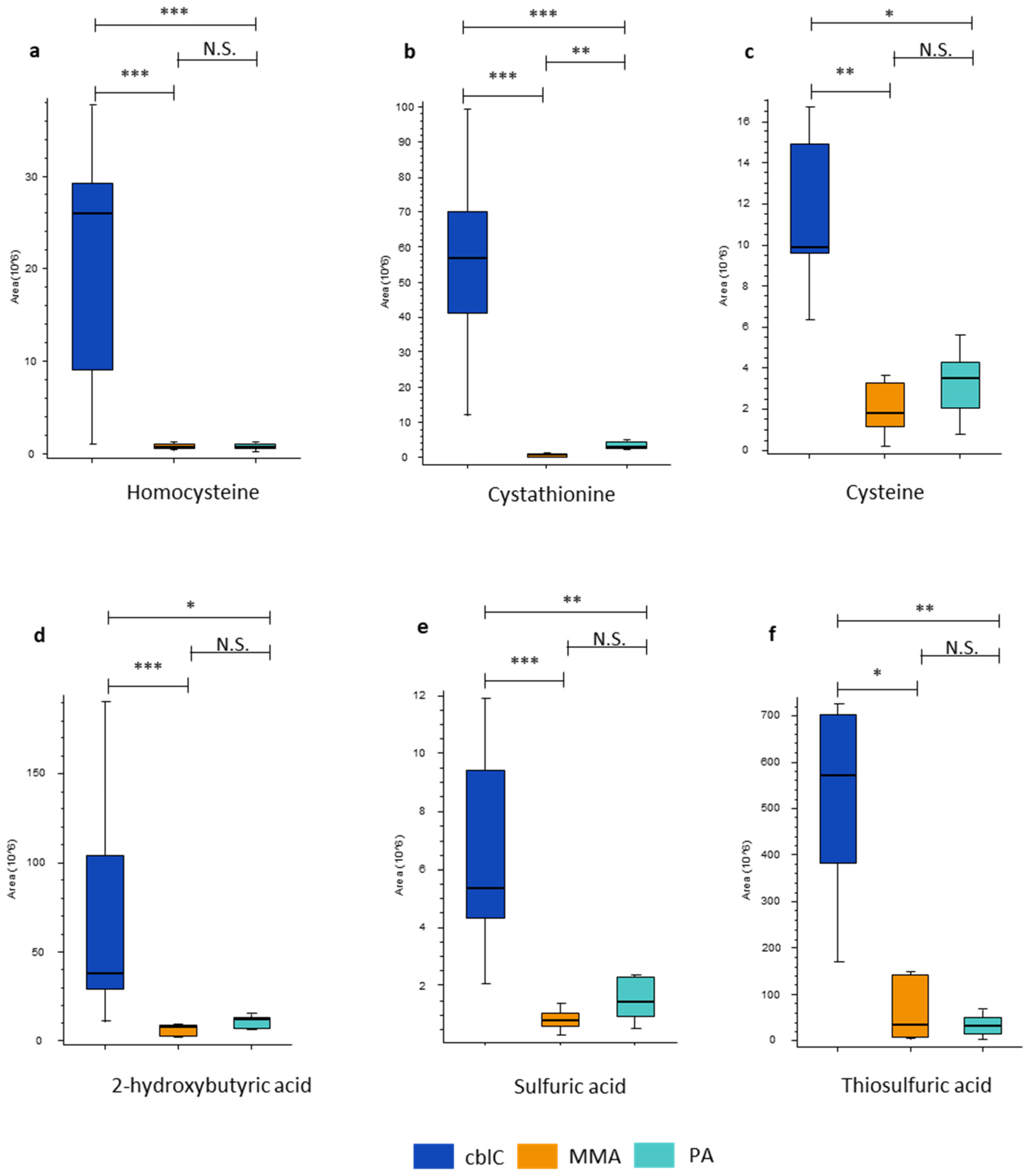

4.1.4. Transsulfuration Pathway Metabolites

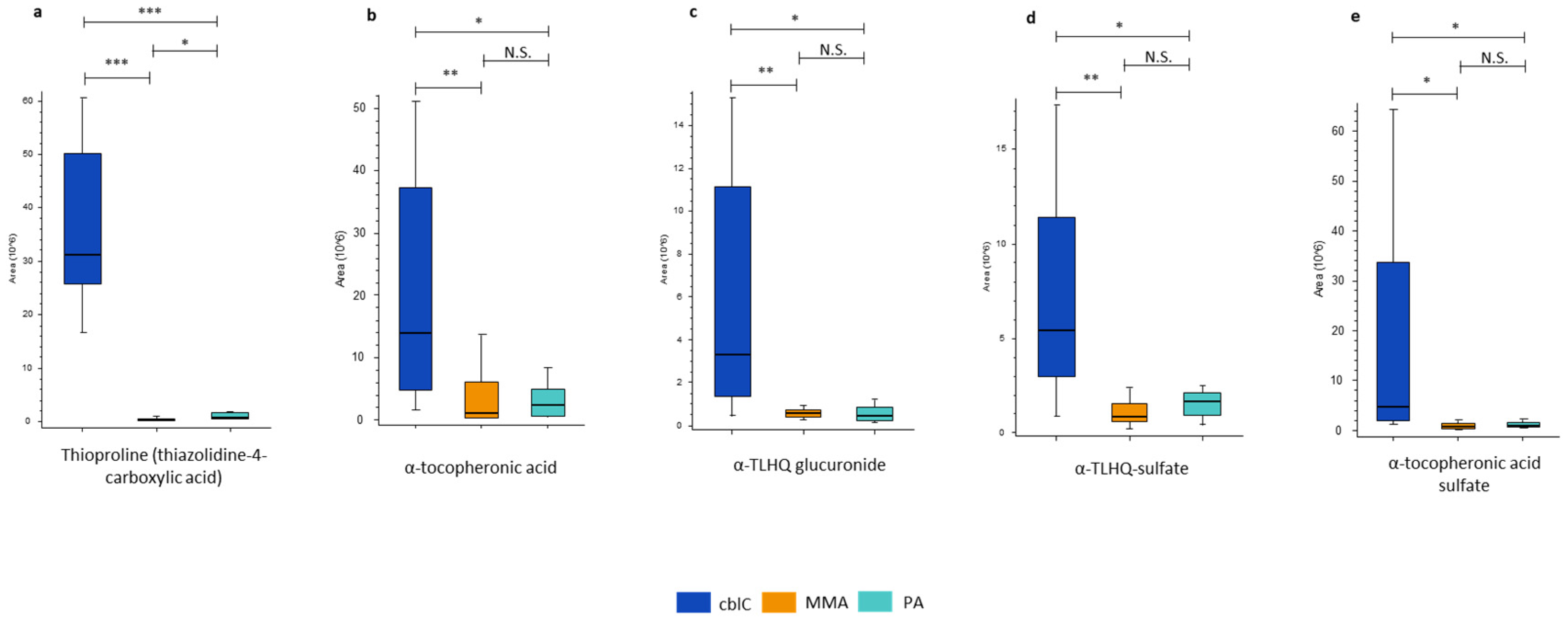

4.1.5. Biomarkers of Oxidative Damage

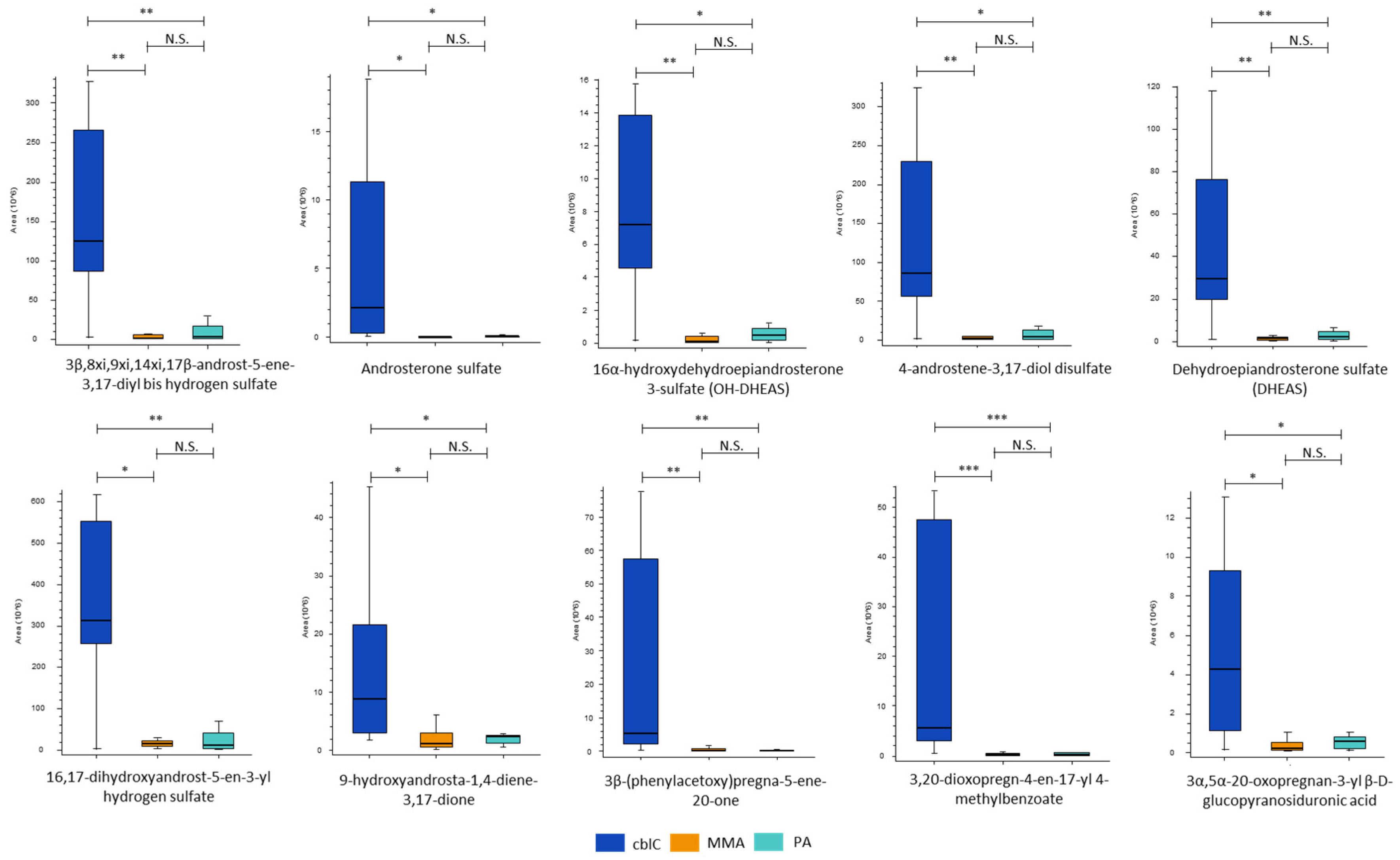

4.1.6. Steroid Hormones

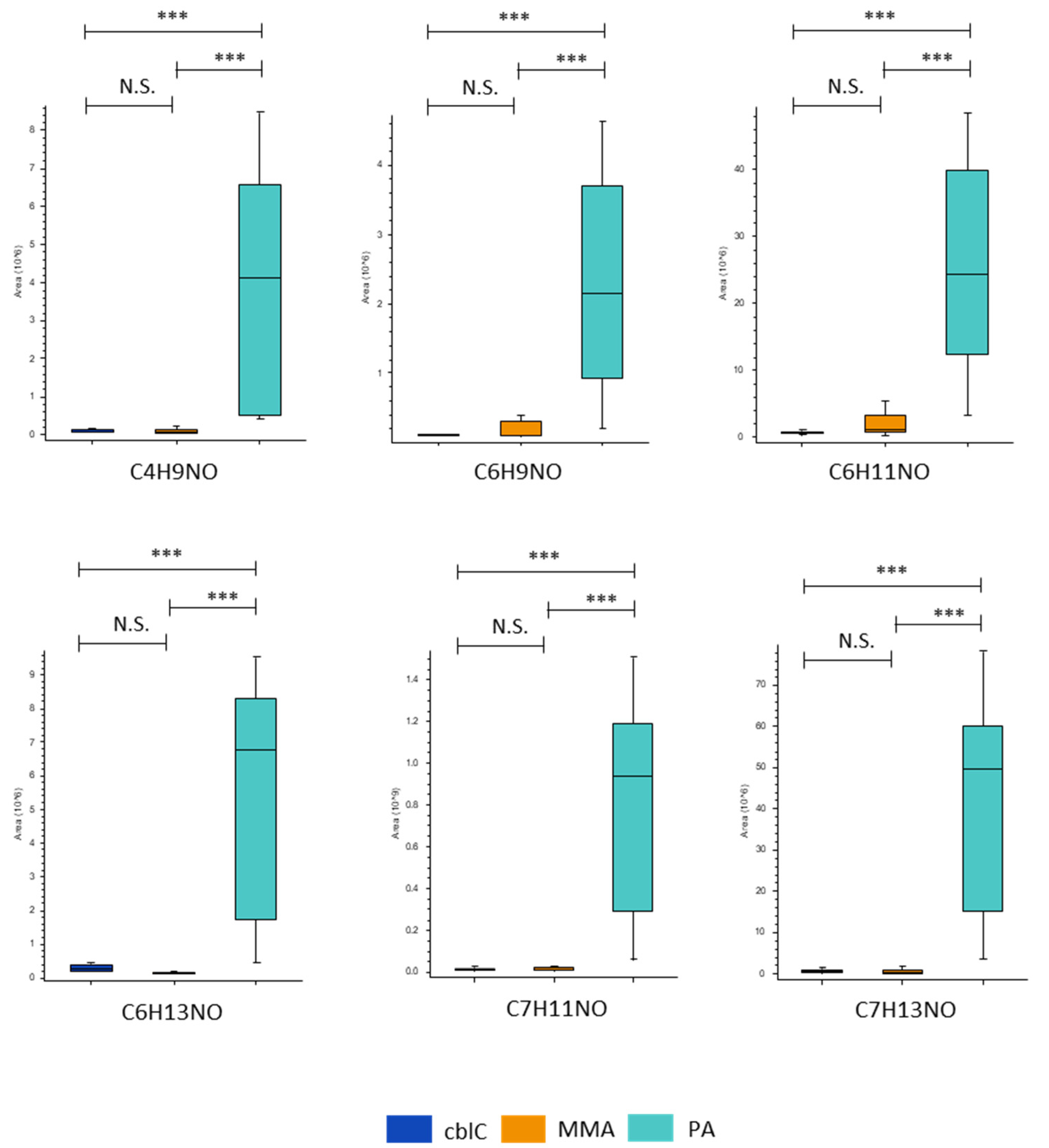

4.1.7. Non-Annotated Metabolites CxHyNO in PA

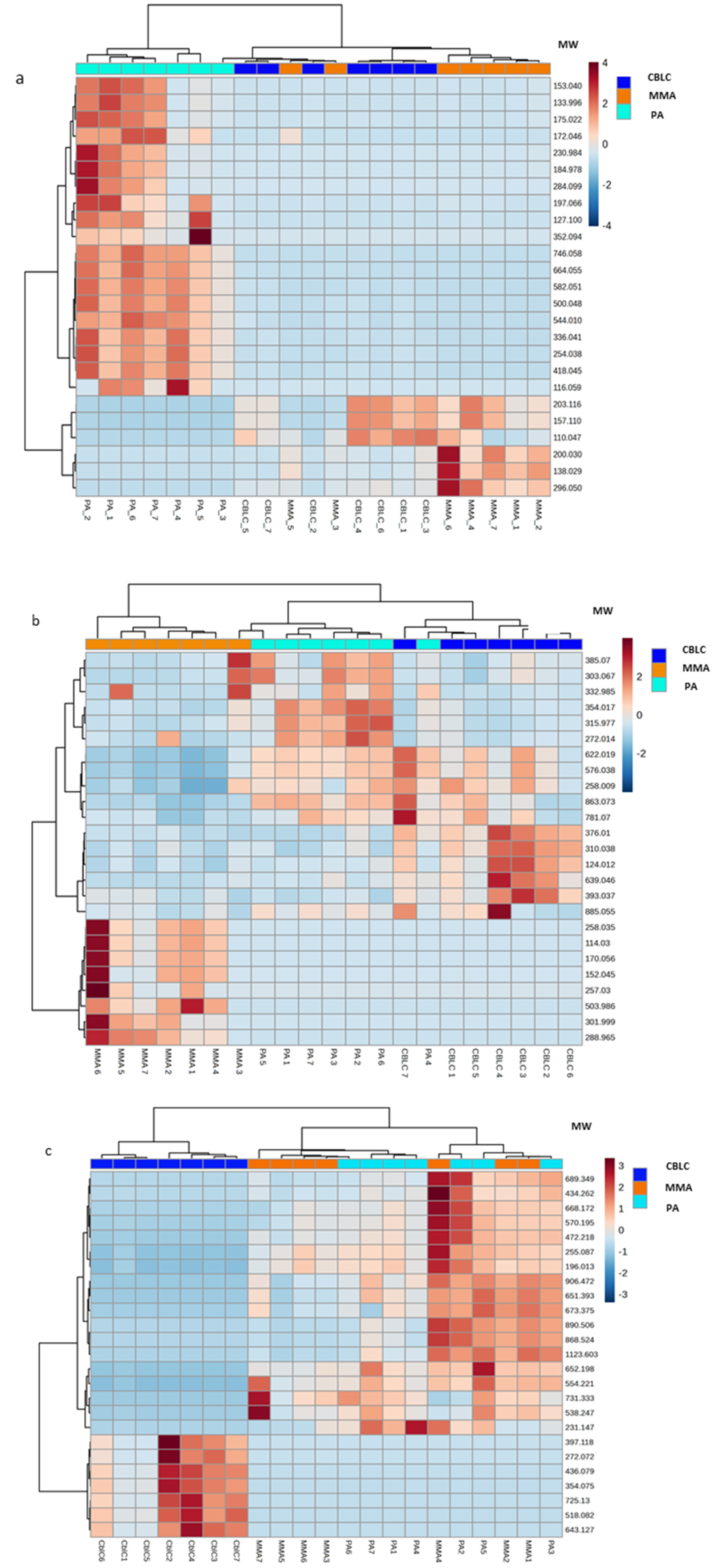

4.1.8. The Most Dysregulated Non-Annotated Features

5. Discussion

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Deodato F, Boenzi S, Santorelli FM, Dionisi-Vici C. Methylmalonic and propionic aciduria. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2006 May 15;142C(2):104-12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huemer M, Diodato D, Schwahn B, Schiff M, Bandeira A, Benoist JF, Burlina A, Cerone R, Couce ML, Garcia-Cazorla A, la Marca G, Pasquini E, Vilarinho L, Weisfeld-Adams JD, Kožich V, Blom H, Baumgartner MR, Dionisi-Vici C. Guidelines for diagnosis and management of the cobalamin-related remethylation disorders cblC, cblD, cblE, cblF, cblG, cblJ and MTHFR deficiency. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2017 Jan;40(1):21-48. Epub 2016 Nov 30. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Huemer M, Diodato D, Martinelli D, Olivieri G, Blom H, Gleich F, Kölker S, Kožich V, Morris AA, Seifert B, Froese DS, Baumgartner MR, Dionisi-Vici C; EHOD consortium; et al. Phenotype, treatment practice and outcome in the cobalamin-dependent remethylation disorders and MTHFR deficiency: Data from the E-HOD registry. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2019 Mar;42(2):333-352. Epub 2019 Feb 17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longo N, Sass JO, Jurecka A, Vockley J. Biomarkers for drug development in propionic and methylmalonic acidemias. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2022 Mar;45(2):132-143. Epub 2022 Jan 26. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Maines E, Catesini G, Boenzi S, Mosca A, Candusso M, Dello Strologo L, Martinelli D, Maiorana A, Liguori A, Olivieri G, Taurisano R, Piemonte F, Rizzo C, Spada M, Dionisi-Vici C. Plasma methylcitric acid and its correlations with other disease biomarkers: The impact in the follow up of patients with propionic and methylmalonic acidemia. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2020 Nov;43(6):1173-1185. Epub 2020 Aug 23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forny P, Hörster F, Ballhausen D, Chakrapani A, Chapman KA, Dionisi-Vici C, Dixon M, Grünert SC, Grunewald S, Haliloglu G, Hochuli M, Honzik T, Karall D, Martinelli D, Molema F, Sass JO, Scholl-Bürgi S, Tal G, Williams M, Huemer M, Baumgartner MR. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of methylmalonic acidaemia and propionic acidaemia: First revision. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2021 May;44(3):566-592. Epub 2021 Mar 9. Erratum in: J Inherit Metab Dis. 2022 Jul;45(4):862. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Manoli I, Gebremariam A, McCoy S, Pass AR, Gagné J, Hall C, Ferry S, Van Ryzin C, Sloan JL, Sacchetti E, Catesini G, Rizzo C, Martinelli D, Spada M, Dionisi-Vici C, Venditti CP. Biomarkers to predict disease progression and therapeutic response in isolated methylmalonic acidemia. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2023 Jul;46(4):554-572. Epub 2023 Jun 6. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Johnson CH, Ivanisevic J, Siuzdak G. Metabolomics: beyond biomarkers and towards mechanisms. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016 Jul;17(7):451-9. Epub 2016 Mar 16. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wurth R, Turgeon C, Stander Z, Oglesbee D. An evaluation of untargeted metabolomics methods to characterize inborn errors of metabolism. Mol Genet Metab. 2024 Jan;141(1):108115. Epub 2023 Dec 15. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Anzmann AF, Pinto S, Busa V, Carlson J, McRitchie S, Sumner S, Pandey A, Vernon HJ. Multi-omics studies in cellular models of methylmalonic acidemia and propionic acidemia reveal dysregulation of serine metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2019 Dec 1;1865(12):165538. Epub 2019 Aug 23. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wikoff WR, Gangoiti JA, Barshop BA, Siuzdak G. Metabolomics identifies perturbations in human disorders of propionate metabolism. Clin Chem. 2007 Dec;53(12):2169-76. Epub 2007 Oct 19. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forny P, Bonilla X, Lamparter D, Shao W, Plessl T, Frei C, Bingisser A, Goetze S, van Drogen A, Harshman K, Pedrioli PGA, Howald C, Poms M, Traversi F, Bürer C, Cherkaoui S, Morscher RJ, Simmons L, Forny M, Xenarios I, Aebersold R, Zamboni N, Rätsch G, Dermitzakis ET, Wollscheid B, Baumgartner MR, Froese DS. Integrated multi-omics reveals anaplerotic rewiring in methylmalonyl-CoA mutase deficiency. Nat Metab. 2023 Jan;5(1):80-95. Epub 2023 Jan 26. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Haijes HA, Jans JJM, van der Ham M, van Hasselt PM, Verhoeven-Duif NM. Understanding acute metabolic decompensation in propionic and methylmalonic acidemias: a deep metabolic phenotyping approach. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2020 Mar 6;15(1):68. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liu N, Xiao J, Gijavanekar C, Pappan KL, Glinton KE, Shayota BJ, Kennedy AD, Sun Q, Sutton VR, Elsea SH. Comparison of Untargeted Metabolomic Profiling vs Traditional Metabolic Screening to Identify Inborn Errors of Metabolism. JAMA Netw Open. 2021 Jul 1;4(7):e2114155. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Miller MJ, Kennedy AD, Eckhart AD, Burrage LC, Wulff JE, Miller LA, Milburn MV, Ryals JA, Beaudet AL, Sun Q, Sutton VR, Elsea SH. Untargeted metabolomic analysis for the clinical screening of inborn errors of metabolism. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2015 Nov;38(6):1029-39. Epub 2015 Apr 15. Erratum in: J Inherit Metab Dis. 2016 Sep;39(5):757. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Warrack BM, Hnatyshyn S, Ott KH, Reily MD, Sanders M, Zhang H, Drexler DM. Normalization strategies for metabonomic analysis of urine samples. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2009 Feb 15;877(5-6):547-52. Epub 2009 Jan 14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen Vollmar AK, Rattray NJW, Cai Y, Santos-Neto ÁJ, Deziel NC, Jukic AMZ, Johnson CH. Normalizing Untargeted Periconceptional Urinary Metabolomics Data: A Comparison of Approaches. Metabolites. 2019 Sep 21;9(10):198. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dieterle F, Ross A, Schlotterbeck G, Senn H. Probabilistic quotient normalization as robust method to account for dilution of complex biological mixtures. Application in 1H NMR metabonomics. Anal Chem. 2006 Jul 1;78(13):4281-90. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun J, Xia Y. Pretreating and normalizing metabolomics data for statistical analysis. Genes Dis. 2023 Jul 7;11(3):100979. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gallagher EM, Rizzo GM, Dorsey R, Dhummakupt ES, Moran TS, Mach PM, Jenkins CC. Normalization of organ-on-a-Chip samples for mass spectrometry based proteomics and metabolomics via Dansylation-based assay. Toxicol In Vitro. 2023 Apr;88:105540. Epub 2022 Dec 20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barr DB, Wilder LC, Caudill SP, Gonzalez AJ, Needham LL, Pirkle JL. Urinary creatinine concentrations in the U.S. population: implications for urinary biologic monitoring measurements. Environ Health Perspect. 2005 Feb;113(2):192-200. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Miller RC, Brindle E, Holman DJ, Shofer J, Klein NA, Soules MR, O'Connor KA. Comparison of specific gravity and creatinine for normalizing urinary reproductive hormone concentrations. Clin Chem. 2004 May;50(5):924-32. Epub 2004 Mar 11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies SE, Iles RA, Stacey TE, Chalmers RA. Creatine metabolism during metabolic perturbations in patients with organic acidurias. Clin Chim Acta. 1990 Dec 24;194(2-3):203-17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younessi D, Moseley K, Yano S. Creatine metabolism in combined methylmalonic aciduria and homocystinuria disease revisited. Ann Neurol. 2009 Apr;65(4):481-2; author reply 482-3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuck PF, Rosa RB, Pettenuzzo LF, Sitta A, Wannmacher CM, Wyse AT, Wajner M. Inhibition of mitochondrial creatine kinase activity from rat cerebral cortex by methylmalonic acid. Neurochem Int. 2004 Oct;45(5):661-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shchelochkov OA, Manoli I, Sloan JL, Ferry S, Pass A, Van Ryzin C, Myles J, Schoenfeld M, McGuire P, Rosing DR, Levin MD, Kopp JB, Venditti CP. Chronic kidney disease in propionic acidemia. Genet Med. 2019 Dec;21(12):2830-2835. Epub 2019 Jun 28. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fowler B, Leonard JV, Baumgartner MR. Causes of and diagnostic approach to methylmalonic acidurias. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2008 Jun;31(3):350-60. Epub 2008 Jun 19. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frenkel EP, Kitchens RL. A simplified and rapid quantitative assay for propionic and methylmalonic acids in urine. J Lab Clin Med. 1975 Mar;85(3):487-96. [PubMed]

- Frenkel EP, Kitchens RL. Applicability of an enzymatic quantitation of methylmalonic, propionic, and acetic acids in normal and megaloblastic states. Blood. 1977 Jan;49(1):125-37. [PubMed]

- Truscott RJ, Pullin CJ, Halpern B, Hammond J, Haan E, Danks DM. The identification of 3-keto-2-methylvaleric acid and 3-hydroxy-2-methylvaleric acid in a patient with propionic acidemia. Biomed Mass Spectrom. 1979 Jul;6(7):294-300. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalmers R. A., Lawson A. M. (1982) Organic Acids in Man. The Analytical Chemistry, Biochemistry and Diagnosis of the Organic Acidurias, London: Chapman & Hall.

- Wongkittichote P, Cunningham G, Summar ML, Pumbo E, Forny P, Baumgartner MR, Chapman KA. Tricarboxylic acid cycle enzyme activities in a mouse model of methylmalonic aciduria. Mol Genet Metab. 2019 Dec;128(4):444-451. Epub 2019 Oct 17. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Longo N, Price LB, Gappmaier E, Cantor NL, Ernst SL, Bailey C, Pasquali M. Anaplerotic therapy in propionic acidemia. Mol Genet Metab. 2017 Sep;122(1-2):51-59. Epub 2017 Jul 12. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Parfait B, de Lonlay P, von Kleist-Retzow JC, Cormier-Daire V, Chrétien D, Rötig A, Rabier D, Saudubray JM, Rustin P, Munnich A. The neurogenic weakness, ataxia and retinitis pigmentosa (NARP) syndrome mtDNA mutation (T8993G) triggers muscle ATPase deficiency and hypocitrullinaemia. Eur J Pediatr. 1999 Jan;158(1):55-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramanian C, Frank MW, Tangallapally R, Yun MK, Edwards A, White SW, Lee RE, Rock CO, Jackowski S. Pantothenate kinase activation relieves coenzyme A sequestration and improves mitochondrial function in mice with propionic acidemia. Sci Transl Med. 2021 Sep 15;13(611):eabf5965. Epub 2021 Sep 15. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Almannai M, El-Hattab AW. Nitric Oxide Deficiency in Mitochondrial Disorders: The Utility of Arginine and Citrulline. Front Mol Neurosci. 2021 Aug 5;14:682780. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zecchini V, Paupe V, Herranz-Montoya I, Janssen J, Wortel IMN, Morris JL, Ferguson A, Chowdury SR, Segarra-Mondejar M, Costa ASH, Pereira GC, Tronci L, Young T, Nikitopoulou E, Yang M, Bihary D, Caicci F, Nagashima S, Speed A, Bokea K, Baig Z, Samarajiwa S, Tran M, Mitchell T, Johnson M, Prudent J, Frezza C. Fumarate induces vesicular release of mtDNA to drive innate immunity. Nature. 2023 Mar;615(7952):499-506. Epub 2023 Mar 8. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Head PE, Myung S, Chen Y, Schneller JL, Wang C, Duncan N, Hoffman P, Chang D, Gebremariam A, Gucek M, Manoli I, Venditti CP. Aberrant methylmalonylation underlies methylmalonic acidemia and is attenuated by an engineered sirtuin. Sci Transl Med. 2022 May 25;14(646):eabn4772. Epub 2022 May 25. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Haijes HA, van Hasselt PM, Jans JJM, Verhoeven-Duif NM. Pathophysiology of propionic and methylmalonic acidemias. Part 2: Treatment strategies. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2019 Sep;42(5):745-761. Epub 2019 Jul 9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roe CR, Bohan TP. L-carnitine therapy in propionicacidaemia. Lancet. 1982 Jun 19;1(8286):1411-2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krieger I, Tanaka K. Therapeutic effects of glycine in isovaleric acidemia. Pediatr Res. 1976 Jan;10(1):25-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzo C, Boenzi S, Inglese R, la Marca G, Muraca M, Martinez TB, Johnson DW, Zelli E, Dionisi-Vici C. Measurement of succinyl-carnitine and methylmalonyl-carnitine on dried blood spot by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Clin Chim Acta. 2014 Feb 15;429:30-3. Epub 2013 Nov 22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sloan JL, Achilly NP, Arnold ML, Catlett JL, Blake T, Bishop K, Jones M, Harper U, English MA, Anderson S, Trivedi NS, Elkahloun A, Hoffmann V, Brooks BP, Sood R, Venditti CP. The vitamin B12 processing enzyme, mmachc, is essential for zebrafish survival, growth and retinal morphology. Hum Mol Genet. 2020 Aug 3;29(13):2109-2123. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hoss, G. R. W., Poloni, S., Blom, H. J., & Schwartz, I. V. D. (2019). Three main causes of homocystinuria: CBS, cblC and MTHFR deficiency. What do they have in common? Journal of Inborn Errors of Metabolism and Screening, 7, e20190007.

- Sbodio JI, Snyder SH, Paul BD. Regulators of the transsulfuration pathway. Br J Pharmacol. 2019 Feb;176(4):583-593. Epub 2018 Aug 23. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Stipanuk MH, Ueki I. Dealing with methionine/homocysteine sulfur: cysteine metabolism to taurine and inorganic sulfur. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2011 Feb;34(1):17-32. Epub 2010 Feb 17. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mc Guire PJ, Parikh A, Diaz GA. Profiling of oxidative stress in patients with inborn errors of metabolism. Mol Genet Metab. 2009 Sep-Oct;98(1-2):173-80. Epub 2009 Jun 14. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rivera-Barahona A, Alonso-Barroso E, Pérez B, Murphy MP, Richard E, Desviat LR. Treatment with antioxidants ameliorates oxidative damage in a mouse model of propionic acidemia. Mol Genet Metab. 2017 Sep;122(1-2):43-50. Epub 2017 Jul 25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallego-Villar L, Rivera-Barahona A, Cuevas-Martín C, Guenzel A, Pérez B, Barry MA, Murphy MP, Logan A, Gonzalez-Quintana A, Martín MA, Medina S, Gil-Izquierdo A, Cuezva JM, Richard E, Desviat LR. In vivo evidence of mitochondrial dysfunction and altered redox homeostasis in a genetic mouse model of propionic acidemia: Implications for the pathophysiology of this disorder. Free Radic Biol Med. 2016 Jul;96:1-12. Epub 2016 Apr 12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu Y, Wang S, Zhang X, Cai H, Liu J, Fang S, Yu B. The Regulation and Characterization of Mitochondrial-Derived Methylmalonic Acid in Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Oxidative Stress: From Basic Research to Clinical Practice. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022 May 24;2022:7043883. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Richard E, Jorge-Finnigan A, Garcia-Villoria J, Merinero B, Desviat LR, Gort L, Briones P, Leal F, Pérez-Cerdá C, Ribes A, Ugarte M, Pérez B; MMACHC Working Group. Genetic and cellular studies of oxidative stress in methylmalonic aciduria (MMA) cobalamin deficiency type C (cblC) with homocystinuria (MMACHC). Hum Mutat. 2009 Nov;30(11):1558-66. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastore A, Martinelli D, Piemonte F, Tozzi G, Boenzi S, Di Giovamberardino G, Petrillo S, Bertini E, Dionisi-Vici C. Glutathione metabolism in cobalamin deficiency type C (cblC). J Inherit Metab Dis. 2014 Jan;37(1):125-9. Epub 2013 Apr 9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo J, Hashimoto Y, Martens LG, Meulmeester FL, Ashrafi N, Mook-Kanamori DO, Rosendaal FR, Jukema JW, van Dijk KW, Mills K, le Cessie S, Noordam R, van Heemst D. Associations of metabolomic profiles with circulating vitamin E and urinary vitamin E metabolites in middle-aged individuals. Nutrition. 2022 Jan;93:111440. Epub 2021 Jul 29. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallert M, Schmölz L, Galli F, Birringer M, Lorkowski S. Regulatory metabolites of vitamin E and their putative relevance for atherogenesis. Redox Biol. 2014 Feb 19;2:495-503. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sharma G, Muller DP, O'Riordan SM, Bryan S, Dattani MT, Hindmarsh PC, Mills K. Urinary conjugated α-tocopheronolactone--a biomarker of oxidative stress in children with type 1 diabetes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013 Feb;55:54-62. Epub 2012 Oct 27. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ham YH, Jason Chan KK, Chan W. Thioproline Serves as an Efficient Antioxidant Protecting Human Cells from Oxidative Stress and Improves Cell Viability. Chem Res Toxicol. 2020 Jul 20;33(7):1815-1821. Epub 2020 Apr 30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morellato AE, Umansky C, Pontel LB. The toxic side of one-carbon metabolism and epigenetics. Redox Biol. 2021 Apr;40:101850. Epub 2020 Dec 28. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Barroso, M., Handy, D. E., & Castro, R. (2019). The link between hyperhomocysteinemia and hypomethylation: Implications for cardiovascular disease. Journal of Inborn Errors of Metabolism and Screening, 5, e160024.

- Pietzke M, Burgos-Barragan G, Wit N, Tait-Mulder J, Sumpton D, Mackay GM, Patel KJ, Vazquez A. Amino acid dependent formaldehyde metabolism in mammals. Commun Chem. 2020 Jun 16;3(1):78. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tulpule K, Dringen R. Formaldehyde in brain: an overlooked player in neurodegeneration? J Neurochem. 2013 Oct;127(1):7-21. Epub 2013 Jul 15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaudry H, Ubuka T, Soma KK, Tsutsui K. Editorial: Recent Progress and Perspectives in Neurosteroid Research. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022 Jul 27;13:951990. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Strac DS, Konjevod M, Perkovic MN, Tudor L, Erjavec GN, Pivac N. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and its Sulphate (DHEAS) in Alzheimer's Disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2020;17(2):141-157. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz C, Karali K, Fodelianaki G, Gravanis A, Chavakis T, Charalampopoulos I, Alexaki VI. Neurosteroids as regulators of neuroinflammation. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2019 Oct;55:100788. Epub 2019 Sep 9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chik MW, Hazalin NAMN, Singh GKS. Regulation of phase I and phase II neurosteroid enzymes in the hippocampus of an Alzheimer's disease rat model: A focus on sulphotransferases and UDP-glucuronosyltransferases. Steroids. 2022 Aug;184:109035. Epub 2022 Apr 8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd-Evans E, Waller-Evans H. Biosynthesis and signalling functions of central and peripheral nervous system neurosteroids in health and disease. Essays Biochem. 2020 Sep 23;64(3):591-606. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bianchi VE, Rizzi L, Bresciani E, Omeljaniuk RJ, Torsello A. Androgen Therapy in Neurodegenerative Diseases. J Endocr Soc. 2020 Aug 21;4(11):bvaa120. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Naylor JC, Hulette CM, Steffens DC, Shampine LJ, Ervin JF, Payne VM, Massing MW, Kilts JD, Strauss JL, Calhoun PS, Calnaido RP, Blazer DG, Lieberman JA, Madison RD, Marx CE. Cerebrospinal fluid dehydroepiandrosterone levels are correlated with brain dehydroepiandrosterone levels, elevated in Alzheimer's disease, and related to neuropathological disease stage. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008 Aug;93(8):3173-8. Epub 2008 May 13. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Marx CE, Trost WT, Shampine LJ, Stevens RD, Hulette CM, Steffens DC, Ervin JF, Butterfield MI, Blazer DG, Massing MW, Lieberman JA. The neurosteroid allopregnanolone is reduced in prefrontal cortex in Alzheimer's disease. Biol Psychiatry. 2006 Dec 15;60(12):1287-94. Epub 2006 Sep 25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troisi J, Landolfi A, Vitale C, Longo K, Cozzolino A, Squillante M, Savanelli MC, Barone P, Amboni M. A metabolomic signature of treated and drug-naïve patients with Parkinson's disease: a pilot study. Metabolomics. 2019 Jun 10;15(6):90. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao Y, Li T, Liu Z, Wang X, Xu X, Li S, Xu G, Le W. Comprehensive metabolic profiling of Parkinson's disease by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Mol Neurodegener. 2021 Jan 23;16(1):4. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nuzzi R, Caselgrandi P. Sex Hormones and Their Effects on Ocular Disorders and Pathophysiology: Current Aspects and Our Experience. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Mar 17;23(6):3269. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nishikawa Y, Morishita S, Horie T, Fukumoto M, Sato T, Kida T, Oku H, Sugasawa J, Ikeda T, Nakamura K. A comparison of sex steroid concentration levels in the vitreous and serum of patients with vitreoretinal diseases. PLoS One. 2017 Jul 13;12(7):e0180933. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schellevis RL, Altay L, Kalisingh A, Mulders TWF, Sitnilska V, Hoyng CB, Boon CJF, Groenewoud JMM, de Jong EK, den Hollander AI. Elevated Steroid Hormone Levels in Active Chronic Central Serous Chorioretinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019 Aug 1;60(10):3407-3413. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Jin Ju, Hyeong Gon Yu, and Seung Yup Ku. "Sex Steroid Hormone and Ophthalmic Disease." Korean Journal of Reproductive Medicine 37.2 (2010): 89-98.

- Nuzzi R, Scalabrin S, Becco A, Panzica G. Gonadal Hormones and Retinal Disorders: A Review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2018 Mar 2;9:66. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Onal H, Kutlu E, Aydın B, Ersen A, Topal N, Adal E, Güneş H, Doktur H, Tanıdır C, Pirhan D, Sayın N. Assessment of retinal thickness as a marker of brain masculinization in children with congenital adrenal hyperplasia: a pilot study. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2019 Jul 26;32(7):683-687. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrell EK, Chen Y, Barazanji M, Jeffries KA, Cameroamortegui F, Merkler DJ. Primary fatty acid amide metabolism: conversion of fatty acids and an ethanolamine in N18TG2 and SCP cells. J Lipid Res. 2012 Feb;53(2):247-56. Epub 2011 Nov 16. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Šebela M, Rašková M. Polyamine-Derived Aminoaldehydes and Acrolein: Cytotoxicity, Reactivity and Analysis of the Induced Protein Modifications. Molecules. 2023 Nov 4;28(21):7429. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Patient | Onset | Cardiac involvement |

Pancreatitis | Renal disease | Visual dysfunction | Epilepsy | Abnormal MRI |

Developmental delay/ intellectual disablity |

Deafness | Age at urine sampling (years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA 1 | Neonatal | - | - | - | - | - | + | + | + | 2.1 |

| PA 2 | 7 months | + | - | - | - | - | + | + | - | 9.9 |

| PA 3 | 3 months | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 20.4 |

| PA 4 | Neonatal | + | - | - | - | - | - | +/- | + | 15.2 |

| PA 5 | Neonatal (NBS symptomatic) | - | - | - | - | - | - | +/- | - | 0.4 |

| PA 6 | Neonatal (NBS symptomatic) | - | - | - | - | - | + | + | - | 0.8 |

| PA 7 | Neonatal | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 7.0 |

| MMA 1 | Neonatal | - | - | ++ | - | - | +/- | - | - | 0.6 |

| MMA 2 | Neonatal | - | + | +/- | - | - | +/- | + | + | 1.2 |

| MMA 3 | Neonatal | - | - | - | - | - | ++ | + | NA | 10.6 |

| MMA 4 | 17 months | - | - | ++ | + | - | - | - | - | 20.6 |

| MMA 5 | NBS (asymptomatic) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.3 |

| MMA 6 | Neonatal (NBS symptomatic) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | NA | 3.7 |

| MMA 7 | 6 months | - | + | ++ | + | - | ++ | - | - | 22.2 |

| cblC 1 | Neonatal (NBS symptomatic) | + | - | - | + | - | - | +/- | - | 0.4 |

| cblC 2 | Neonatal | - | - | + | + | + | + | + | - | 3.7 |

| cblC 3 | 2 months | + | - | + | + | + | ++ | ++ | - | 2.8 |

| cblC 4 | Neonatal | - | - | - | + | + | + | + | - | 3.3 |

| cblC 5 | 5 months | - | - | - | + | ++ | + | ++ | - | 13.7 |

| cblC 6 | Neonatal | - | - | -/+ | + | - | + | +/- | - | 13.2 |

| cblC 7 | 3 months | ++ | - | + | - | + | +/- | +/- | - | 17.1 |

| Metabolite | cblC/MMA | cblC/PA | PA/MMA | KEGG Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic acids and ketones | ||||

| Citric and isocitric acids | 3.3** | 2.5** | ns | • Tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) • Glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolsim • Alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism |

| 2-butanone | 0.5* | 0.13*** | 3.9*** | |

| Fumaric acid | 0.3* | 0.2*** | ns | • TCA • Arginine biosynthesis • Pyruvate metabolism • Alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism |

| Malic acid | 0.2* | 0.08*** | ns | • TCA • Glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism • Pyruvate metabolism |

| Methylmalonic acid | 0.06*** | 19*** | 0.003*** | • Valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation • Propanoate metabolism • Pyrimidine metabolism |

| MW 74.036 (propionic acid isobar) | 0.05*** | 12*** | 0.004*** | |

| 2-methylcitric acid | ns | 0.2*** | 4.3*** | • Propanoate metabolism |

| 2-methyl-3-hydroxy-valeric acid | ns | 0.3*** | 5.4*** | |

| 3-oxo-valeric acid | ns | 0.21*** | 3.4*** | |

| 2-methyl-3-oxo-valeric acid | ns | 0.09** | 8.3** | |

| 3-pentanone | ns | 0.06*** | 10*** | |

| Glycine and carnitine conjugates | ||||

| C4DC-carnitine | 2.1* | 348*** | 0.006*** | |

| Propionylcarnitine | 0.06*** | 0.05*** | ns | |

| Propionylglycine | ns | 0.01*** | 60*** | |

| Propionylcarinitine glycine conjugate | ns | 0.05** | 23*** | |

| Tiglylglycine | ns | 0.07*** | 21*** | |

| Butyrylglycine | ns | 0.2** | 11*** | |

| Amino acids and peptides | ||||

| Threonine | 83*** | 36*** | ns | • Glycine, serine and threonine metabolism • Valine, leucine and isoleucine biosynthesis |

| Butyl-α-aspartyl-allothreoninate | 28*** | 20*** | ns | |

| Isoleucine | 24** | 50*** | ns | • Valine, leucine and isoleucine biosynthesis • Valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation |

| Dimethylglycine | 21*** | 36*** | ns | • Glycine, serine and threonine metabolism |

| Isoleucylalanine | 15*** | 3.4** | ns | |

| Aspartylphenylalanine | 9.6* | 23.4** | ns | |

| Glutamylisoleucine | 9.4*** | 19* | ns | |

| Prolylproline | 8.0** | 4.4* | ns | |

| Valylvaline | 7.7** | 3.6* | ns | |

| Glycylglycyl-alanyl-2-methylalanine | 6.7* | 11** | ns | |

| Isoleucylvaline | 5.0** | 4.9** | ns | |

| Lysine | 4.1** | ns | ns | • Biotin metabolism |

| Citrulline | 3.9** | 2.3* | ns | • Arginine biosynthesis |

| Valine | 3.8*** | 2.4*** | 1.6* | • Valine, leucine and isoleucine biosynthesis • Valine, leucine and isoleucine degradation • Pantothenate and CoA biosynthesis |

| Methionine | ns | 0.07** | 16** | • Cysteine and methionine metabolism • 2-oxocarboxylic acid |

| Glycine | ns | 0.04*** | 33*** | • Glycine, serine and threonine metabolism • Glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism • Glutathione metabolism • Lipoic acid metabolism • Porphyrine metabolism |

| Transsulfuration pathway metabolites | ||||

| Cystathionine | 78*** | 20*** | 3.8** | • Glycine, serine and threonine metabolism • Cysteine and methionine metabolism |

| Homocysteine | 37*** | 39*** | ns | • Cysteine and methionine metabolism |

| Thiosulfuric acid | 17* | 18** | ns | • Sulfur metabolism |

| Cysteine | 5.7** | 3.5* | ns | • Glycine, serine and threonine metabolism • Pantothenate and CoA biosynthesis • Glutathione metabolism • Thiamine metabolism |

| 2-hydroxybutyric acid | 5.0*** | 3.2* | ns | • Propanate metabolism |

| Sulfuric acid | 4.2*** | 2.5** | ns | • Sulfur metabolism |

| Biomarkers of oxidative damage | ||||

| Thioproline | 96*** | 45*** | 2.1* | |

| α-tocopheronic acid | 14** | 5.9* | ns | |

| α-TLHQ glucuronide | 8.0** | 4.7* | ns | |

| α-TLHQ sulfate | 6.8** | 3.3* | ns | |

| α-tocopheronic acid sulfate | 5.9* | 4.9* | ns | |

| CxHyNO features | ||||

| C4 H9 N O | ns | 0.02*** | 48*** | |

| C6 H9 N O | ns | 0.05*** | 21*** | |

| C6 H11 N O | ns | 0.06*** | 30*** | |

| C6 H13 N O | ns | 0.04*** | 44*** | |

| C7 H11 N O | ns | 0.01*** | 72*** | |

| C7 H13 N O | ns | 0.01*** | 142*** | |

| IUPAC or common names of putatively annotated structures | ChemSpider ID | Hierarchical class | Ratio (CblC)/(MMA) | Ratio (CblC)/(PA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3β,8xi,9xi,14xi,17β -Androst-5-ene-3,17-diyl bis hydrogen sulfate (androstendiol disulfate) | 21403154 | androstane | 114.5 | 32.9 |

| Androsterone sulfate | 140383 | androstane | 97.4 | 37.1 |

| 16α- hydroxydehydroepiandrosterone-3-sulfate (OH-DHEAS) | 24850136 | androstane | 53.4 | 15.9 |

| 4-androstene-3β,17β -diol disulfate (androstendiol disulfate) | 58163615 | androstane | 34.3 | 20.0 |

| Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) | 12074 | androstane | 24.7 | 15.4 |

| 16,17-Dihydroxyandrost-5-en-3-yl hydrogen sulfate | 133127 | androstane | 20.1 | 29.4 |

| 9-Hydroxyandrosta-1,4-diene-3,17-dione | 211114 | androstane | 8.2 | 3.8 |

| 3β -(Phenylacetoxy)pregna-5-ene-20-one | 58539760 | pregnane | 40.4 | 33.7 |

| 3,20-Dioxopregn-4-en-17-yl 4-methylbenzoate | 9180030 | pregnane | 34.9 | 28.5 |

| 3α,5α-20-Oxopregnan-3-yl beta-D-glucopyranosiduronic acid (3α-allopregnanolone 3β-D-glucuronide) | 68025990 | pregnane | 19.2 | 7.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).