1. Introduction

Globally, South Africa has been classified as the sixth largest coal producer and exporter, and the mining industry contributes almost 27% of the mineral resource sales, and therefore contributes significantly to the economy of this country (Webb, 2015; Hassan, 2023). Many countries including South Africa mainly depend on coal for power generation, largely due to the fact that it is the most available fossil fuel and affordable means of supplying electricity to consumers (Zou et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2020). Due to the enormous economic contributions made by coal mining over the past few decades, it has gained prominence among the world economies. In 2019, coal generated almost 37% of the world’s electricity, up from 27% in 2007. This supported the prediction that between 2007 and 2020, the world’s coal consumption would increase by an average of 1.1% per year and by an average of 2.2% annually for the period 2020-2035 (IEO, 2020). Coal remains the main non-renewable source of generating electricity in South Africa and Eskom (national electricity supply utility) generates almost 90 per cent of usable electricity in the country from coal (Hancox, & Götz, 2014; DoE, 2016). Depending on the coal combustion methods and emission controls, large quantities of solid waste that include coal fly ash (CFA), boiler slag, bottom ash and fluidized-bed combustion are generated (Ahmedi, & Kusari, 2012).

Coal combustion waste accounts for 5-20 wt.% of burned coal and includes coarse bottom ash (BA) (5-20 wt.%) and fine CFA represents 80-95 wt.% of the ash produced (Yao et al., 2015; Bhatt et al., 2019; Vilakazi et al., 2022). Approximately 600 million tons of CFA is produced per year, dominated by China, India, USA, Germany, and South Africa contributing more than 300 million tons and it is estimated that CFA production will increase yearly by 5% (Dwivedi, & Jain, 2014; Bhatt et al., 2019). Of the CFA produced globally, more than 200 million tonnes remain unused and is stored in ash dumps, thereby presenting serious environmental pollution problems. In South Africa, approximately 28 million tons of CFA is produced annually with utilization rate of less than 10% (ESKOM, 2018; Reynolds-Clausen, & Singh 2022; Vilakazi et al., 2022). Therefore, approximately 26 million tons of CFA are stored in disposal facilities, this presenting serious risks to the health of humans, animals and the environment. Many power stations are currently running out of ash disposal sites and there is a need to expand the disposal facilities (SACCA, 2021), this suggesting that more CFA will be produced and the issues of pollution will continue to be a burden. CFA storage in disposal facilities results to air pollution in windy seasons, groundwater and surface contamination, and affecting soil quality and human health (He et al., 2012). The tiny spherical particles of CFA ranging between 1 and 100 µm in size suspend in air for longer periods and sometimes reducing atmospheric visibility (Karun, & Sridhar, 2016; Maiti, & Prasad, 2016). Human mortality and morbidity, different chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, hypertension, kidney disease, cardiopulmonary disease, and cancers were reported in people who live in the vicinity of coal-fired power plants (C-FPPs) due to the inhalation of coal nanoparticles, micro-particles and its by-products (Saikia et al., 2020; Gasparotto, & Martinello, 2021). All fossil fuels when they are burnt can release carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases leading to global warming. The CFA is disposed of as slurry which is stored in dumping areas and can be released directly into nearby surface water body (Muriithi, 2009). Due to the fact that its reusability rate is lower than its production, its disposal still remains an issue to many countries where they reach to the point all space near the C-FPPs has been used and this suggesting increase in the number of degraded lands (Reynolds-Clausen, & Singh, 2019). Long-term storage can result to leaching of toxic heavy metals and organic contaminants from CFA, ultimately contaminating groundwater and the underlying soils (Muriithi, 2009; Vilakazi et al., 2022). Although CFA is predominantly composed of carbon, it also contains nitrogen, Sulphur, organometallic compounds, toxic metals such as mercury, chromium, cadmium, arsenic, and lead and organic pollutants that are harmful to the whole biosphere and can lead to serious health issues including the nervous system and cancer impacts such as developmental delays, cognitive deficits and behavioral problems (Gasparotto, & Martinello, 2021). Furthermore, they can also cause respiratory distress, gastrointestinal illness, heart damage, kidney and lung diseases, reproductive problems, impaired bone growth, and birth defects in children (USEPA, 2010; Speight, 2021). Because of all these problems, CFA is classified as a health hazard in South Africa. The management of CFA is an important environmental challenge which requires sustainable strategies to reduce air contamination by suspended particulate matters and prevent water and soil pollution through curbing movement of inorganic and organic pollutants into aquatic systems and restore degraded lands (Karun, & Sridhar, 2016; Maiti, & Prasad, 2016).

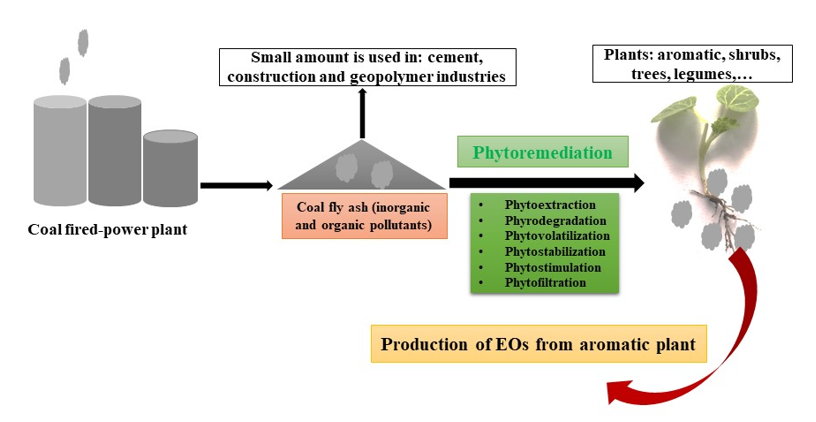

Among conventional and sustainable remediation methods of polluted areas, phytoremediation is a strategy that applies various plant species to transfer, stabilize, remove, and lower availability of pollutants in the soil, groundwater and other waste products (Tripathi et al., 2019; Golubev, 2011; Nedjimi, 2021). It is the most eco-friendly and cost-effective strategy as the plants can colonize the ash dumps, by establishing a self-sustaining vegetative layer for recovery of the ecosystem health (Gajic´ et al., 2018). The polluted area is restored gradually over time, and this results to reduction of pollutants in the environment. Although, there are many reports on phytoremediation of polluted sites, investigations regarding the potential use of phytoremediation strategies for restoration of ash dams is rather sparse. This review aims to discuss the pollution problems related to CFA, production and physicochemical properties of CFA, conventional clean-up methods, CFA disposal methods, various means of CFA utilization and their limitations and we explore the use of plants for addressing pollution problems due to CFA disposal and the economic opportunities that restoration of CFA disposal sites may present. Commercialization is relevant for developing countries, as this will not only solve pollution problems, but will also address societal challenges. Guidance is provided for future studies in selecting suitable species for phytoremediation strategies. In an attempt to suggest suitable species, many studies focus on species that grow in the vicinity of ash disposal sites. However, these plants grow in soils polluted with CFA and therefore may not adapt to 100% CFA media, hence there is sparse vegetation on the CFA disposal sites. To support plant growth, the physicochemical properties of CFA must be altered. In this review, we highlight the advantages offered by the legumes, aromatic plants and grasses due to their capabilities in altering the properties of CFA, making it favourable for plant growth.

2. Production of CFA

Ash is produced inside the boiler furnace from the unburnt carbon and unburnt inorganic components of coal (Wang et al., 2015; Speight, 2021). The ash produced differ based on how they are formed and exit from the boiler. The bottom ash has a gritty and sandy texture fraction that falls into the grates below the boilers where it is mixed with water and pumped to ponds. The CFA is composed of very fine spherical glassy nanoparticles that are formed due to incomplete combustion of coal (Ghassemi, 2004). Powdery CFA is captured before reaching the atmosphere by highly efficient electrostatic precipitators or by a variety of other devices such as baghouses or wet scrubbers (Vilakazi et al., 2022; Molchanov et al., 2023). CFA is the solid by-product produced from the burning of inorganic materials mainly composed of iron and alumina oxides, silica with low levels of magnesium oxide, calcium oxide, unburned carbon, sulphur oxides, and other substances (Fu, 2010). The production of ash rich in minerals is linked to the type of coal used (Kgabi et al., 2009). The ash yields of coal samples collected from different coal mines in South Africa range between 20.0% and 49.6% (Hancox, & Götz, 2014; Matjie et al., 2016). According to Yang (2019), a reasonably clean coal should contain an ash content less than 12.5%, this indicating that much of the coal used is of poor quality, hence high production of ash.

Coal combustion for generation of energy is expected to continue to grow in South Africa due to consumer demands and therefore the generation of CFA production will certainly increase. The coal reserves remaining are estimated for 116 years and therefore will remain a valuable resource for the economy of South Africa. Coal is the dominant source of energy for South Africa, comprising more than 80 percent of the country’s system load. Generating electricity through coal combustion results to the production of solid residues with environmental problems. More than 119 million tons of coal has been consumed between 2014 and 2015, resulting to approximately 35 million tons of CFA (Reynolds-Clausen, & Singh, 2019). Currently, the worldwide generation of ash is estimated at approximately 750 million tons (Szwalec et al., 2022), suggesting that more than 500 million tons is CFA. Though several alternative energy sources have been proposed and implemented, the rate at which the coal is being used as the main source of energy cannot be counterbalanced (Basu et al., 2009; Verma et al., 2014).

3. Characterisation of CFA

CFA can be defined as a fine powder material mostly composed of silica and almost all particles are spherical. The particles result from the burning of pulverised coal at high temperatures that range between 1400 and 1700 °C (Bayat, 1998; Nyale et al., 2013).

It is a heterogeneous material that poses health problems due to its chemical and physical composition. Its composition depends on combustion and cooling procedures, the type of coal (bituminous, subbituminous, lignite and pozzolanic) used, geographical origin of coal, emission control measures, ash collection methods and other factors which impact to a considerable extent, its suitability of applications and remediation processes (van der Merwe et al., 2014; Kelechi et al., 2022). The broad variety of the CFA composition makes it a complex material to be characterized (Alterary, & Marei, 2021). CFA is classified into two classes C and F, as highlighted by American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) (Alterary, & Marei, 2021; Saljnikov et al., 2022). Class C is derived from subbituminous and lignite coals and is used as the replacement material in cement. Class C is mainly composed of calcium, alumina and silica and its calcium oxide content is 20% or more and has cementitious properties (Bentz et al., 2011; Yousaf et al., 2020). Class F has lesser content of calcium oxide as compared to Class C and is mainly pozzolanic in nature with no value in cementing. The total amount of ferric oxide, silicon dioxide and aluminium oxide is greater than 70% for class F, while Class C is characterised by contents between 50-70% of these minerals (Bhatt et al., 2019). Classification, crystallinity, shapes, mineralogy, morphology, and chemical composition reveal the properties of this material and these provide guideline for its reusability and potential as a source of valuable metals (Alegbe et al., 2018).

Physical properties of CFA include particle size distribution, specific surface area, permeability, angle of friction, thermal stability, colour, optimum moisture, specific gravity, and bulk density (Pandian et al., 1998; Mishra, & Das, 2010; Bhatt et al., 2019). CFA consists of fine grey powder of which the particles are principally sphere-shaped of aluminosilicate glass, some hollow and others solid, and mostly amorphous in nature while carbonaceous fraction consists of angular particles (Ghosal, & Self, 1995; Ahmaruzzaman, 2010). The hollow spheres in CFA, commonly known as cenospheres range between 45 and 150 μm (Ngu et al., 2007). CFA particles have a smooth outer surface, which is due to the occurrence of the aluminosilicate glass phases (Inada et al., 2005; Nyale et al., 2013). The particle surface area and the size distribution are important in determining the activity of CFA. For example, particle size and distribution are important factors for geo-polymerization process. Mishra and Das (2010) conducted a study to determine the particle size, shape, chemical composition and mineralogical phase of CFA. They found that CFA is spherical in shape and the bulk ash is porous in nature, mineralogical phase was composed of mullite, quartz and hematite while CFA was predominantly composed of alumina, silica, iron oxide and a little amount of calcium oxide. The South African CFA sample is classified as class F and is mainly composed of crystalline phases quartz (6.1%) and mullite (31.8%) and an amorphous silica-alumina glass phase (62.1%) and has been confirmed to be a good substrate for silica nanoparticle and zeolite syntheses (Musyoka, 2009; Imoisili, Nwanna, & Jen, 2022). Besides the above physical properties, optimal moisture content value for CFA varies between 11% and 53%, with maximum dry density values between 1 and 1.78 g/cm3. CFA is not plastic and it does not swell when used as a base material for buildings (Cokca, & Yilmaz, 2004). CFA has a high specific surface area and low bulk density (Bhatt et al., 2019). The amount of iron and unburned carbon (UBC) impacts the colour of CFA, which varies from orange to deep red or brown and white to yellow. The grey colour of CFA is usually explained by the percentage of unburnt carbon. In small amounts, the presence of ferrous ion-containing compounds can cause a brown coloration, which changes the colour from bluish-grey to grey (Kang et al., 2013).

The chemical properties of CFA highly depend on the origin of coal and the power plant mode of operation. CFA is composed of three main groups including inorganic compounds constituted of crystalline and amorphous phases, organic materials and fluid materials occurring in both inorganic and organic compounds (Alterary, & Marei, 2021). CFA contains minerals and elements in various amounts. The most abundant materials in CFA are inorganic compounds, formerly present in the raw coal, which remain after the coal burning process with a small amount of unburnt carbon that remains from incomplete combustion (Bayat et al., 1998; Nyale et al., 2013; Ingelsson et al., 2020). The most abundant elements found include Si, O2, Ca, Fe, Al, C, K, Na, Ti, P, Mg, and Ba (El-Mogazi et al., 1988; Styszko-Grochowiak et al., 2004; Vassilev, & Vassileva, 2007; Akinyemi et al., 2012). The major oxide constituents in CFA include CaO, quartz (SiO2), Al2O3, and hematite (Fe2O3) (Mainganye et al., 2013). The calcium-bearing minerals include anorthite, akermanite, gehlenite and various calcium aluminates and silicates identical to those found in Portland cements (Snellings, 2012). CFA particles are dominated by Ca-rich plagioclase feldspars, Mg-rich phases, complex Ca-Mg-Al-Si-Ti-Fe grains, trace elements, base metals and trace amounts of rare earth elements (Alegbe et al., 2018; Hower et al., 2022). The CFA with a range of calcium oxide content extending above 15% indicates its self-cementing properties. Other available minerals are sodium oxide, potassium oxide and magnesium oxide which are very important for plant development. The pH values of CFA differ depending on the sulphur/calcium ratio. Depending on pH, CFA is classified as acidic ash (pH 1.2-7), mild alkaline ash (pH 8-9) and strongly alkaline ash (pH 11-13) (Kolbe et al., 2011; Bhatt et al., 2019; Saljnikov et al., 2022). The amount of mercury is usually in the range of 0.01-1.00 mg/L for bituminous coal. The concentrations of other trace elements vary as well according to the type of coal combusted to generate it (Speight, 2017). The constituents of CFA include also a small number of radioisotopes such as 235U, 226Ra, 222Rn, 238U, 232Th, and 40K, which present radiation risk depending on distribution and concentrations (El-Magazi et al., 1998). Acceptable radioactivity level is a key environmental factor to consider for safe utilization of solid wastes (Zielinski, & Finkelman, 1997; Barescut et al., 2011). The toxicity of CFA is normally indicated by the occurrence of toxic heavy metals such as Cd, Ni, As, Ba, and Pb among others, alongside with organic substances (Anjum, 2017). Higher amount of As, Cr, Pb and Hg were reported in CFA than in raw coal, highlighting serious health risks due to CFA disposal (Altıkulaç et al., 2022). The organic matter found in CFA include unburned carbon and various organic compounds. During the coal combustion and pyrolysis processes, chemical and physical changes occur resulting to the formation and emission of various compounds including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) which are known carcinogens (Liu et al., 2008). Relatively higher amounts of PAHs are found in CFA than that in the raw coal (Liu et al., 2000). Low molecular weight-PAHs are the ones that predominate in CFA samples (Sahu et al, 2009). Research also found that polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), aliphatic hydrocarbons and small number of dioxins are also present in CFA (Shibayama et al., 2005; Nomura et al., 2009; Alterary, & Marei, 2021). These organic compounds adsorbed on CFA particles can be dispersed into the environment and therefore posing a risk of contamination and can result to serious health challenges (Ribeiro et al., 2014).

4. Coal Fly Ash Disposal

The disposal of high volume of CFA from C-FPPs consumes too much water and land area. There are two main CFA disposal mechanisms that are used by several C-FPPs worldwide, namely the wet and dry method (Mbugua, 2012). In case of dry disposal system, CFA is directly disposed of in basins and landfills covering several areas of valuable land near the power plants, while in the wet system the CFA slurry is allowed to settle in ash dams, ponds and lagoons and the water is recovered through channelling (Qadir et al., 2019). Disposal of CFA requires huge amount of water burdening the already stressed water systems (Paliwal, 2013). Although wet ash handling systems are closed circuits allowing for the ash water to be recycled, the recirculating is lost through seepage, evaporation and absorption on the ash (Eskom, 2018). The ashes can be dispersed due to wind in the surroundings which affect respiratory system and other human parts leading to cancer, bronchitis, anemia and asthma (USEPA, 2007). To reduce the spread of CFA dust, suppression systems or water sprinklers are installed but these is not a sustainable strategy due to high water consumption. Furthermore, even covers are placed onto the damping site to prevent the carrying away to tiny CFA dust. Watertight covering precautions have also been approved to protect the discarded CFA from the rainwater (Jain, & Tembhurkar, 2022). These common disposal practices are regarded as unsightly, converting lands to non-productive sites, environmentally unsafe and are not feasible financially due to long term conservation (Menghistu, 2010; Mainganye, 2013). CFA contains a high concentration of heavy metals and metalloids that leach out into the environment, which further cause soil or water contamination in the surroundings of power stations (Pandey et al., 2011). It also contains various persistent organic pollutants (POPs) that may lead to the contamination of soils, air and water (Jala, & Goyal, 2006). Large volumes of land are used for CFA disposal and this has become a global concern.

5. Coal Fly Ash Utilization

Alternative to CFA disposal, many countries are reusing it and this has been beneficial for the environment and contributes to economic growth. The biggest producers of CFA include China, India and USA contributing up to approximately 390 million tons of CFA per year as shown in

Table 1 and the production of CFA increases by about 5% yearly. In China, CFA utilization is reported to account 45% and mainly used in production of building materials, paving, mine backfilling and low-end building (Luo et al., 2021). More than 70% of produced CFA is recycled in the USA and is mainly used to produce cement products (Lu et al., 2023). According to Yousef (2020), India produced 217 million tonnes between 2018-2019 and utilized 168.40 million tonnes of CFA for cement production, construction of dams and road, suggesting a utilization of more than 70%. The EU has reported utilization rate over 90%, which can be attributed to small volumes produced and the involvement in projects aimed at turning waste into valuable materials. Countries including Netherlands, Denmark and Italy use up to 100% of the produced CFA followed by Japan which utilizes 96.4% (Kelechi et al., 2022).

CFA is considered as a value-added material in construction and building industry (concrete and cement) including grout, block and brick development, geopolymers, environmental management such as backfilling and mine drainage treatment, land reclamation and soil amelioration, road construction, agriculture, raw material for glass-ceramics production, and recovery of valuable minerals (Dwivedi, & Jain, 2014; Wang, & Chen, 2014). The cement and concrete industries contribute greatly to the recycling of CFA accounting to 44.19% of its utilization, followed by the road construction (15.25%) and 12.49% is reported for remediation of landfills (Loya, & Rawani, 2014). The use of 40% CFA in replacing cement resulted to cost reduction in the process of producing concrete production (Kelechi et al., 2022). Supplementing with CFA results to hardened concrete through pozzolanic and hydraulic activity. An even higher amount of CFA up to 60% can be used in structural uses (Scott, & Thomas, 2007). CFA is also used to synthesize zeolite that can be used in agricultural activities and water treatment processes. CFA-based zeolites have the ability to retain water and cation exchange capacity and therefore widely used for the controlled release of fertilizers in agriculture (Harja, 2016). Zeolites are minerals principally composed of ferro-aluminosilicate elements containing both crystalline and amorphous phases and have stable structures. The characteristics of zeolite include noteworthy ion-exchange capacity, high surface area and unique pore characteristics and therefore have been applied for treatment of ionic and heavy metals from industrial sludges, acid mine drainage and wastewater activities (Zhang et al., 2021; Parra-Huertas et al., 2023). Zeolites have high sorption capacity due to the smaller particle size that increases the specific surface area ranging between 2500 and 4000 cm2/g (Alonso, & Wesche, 1991). Consequently, widely used as a sorbent to clean wastewater containing toxic metals, pigments, dyes, and flue gas of toluene vapors, NOx and SOx (El-Mogazi et al., 1988). Moreover, CFA has been identified as a suitable material for photocatalysis and adsorption of p-nitrophenol because it contains metal oxides such as TiO2, SiO2, Fe3O4 and Al2O3, which are effective in these processes (Park, & Bae, 2019). For example, synthesised zeolite doped with silver nanoparticles was used for mercury (II) removal and about 90% removal efficiency was achieved (Tauanov et al., 2018). In another study, CFA coated with carbon hybrid nanocomposite was synthesised from CFA for the effective removal of cadmium ion from wastewater and the spent adsorbent was reused in the photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue (Umejuru et al., 2020). Furthermore, geopolymeric materials synthesized from CFA can offer valuable solutions to emerging environmental as they can immobilize toxic heavy or radioactive metals through process such as physical encapsulation and chemical stabilization (Adewuyi, 2021). CFA can be applied as a geopolymer concrete binder material due to its wide availability, greater potential and low cost for preparing geopolymers (Pavithra et al., 2016; Feng et al., 2019; Wulandari et al., 2021). However, CFA-based geopolymer materials may be affected by many parameters which are considerably related to the primary materials and their physical and chemical properties such as chemical composition, fineness and glassy phase content (Bouaissi et al., 2018; Feng et al., 2019). The FA/kaolinite ratio, the water content and metal silicates utilized significantly affect the final geopolymer product (Ahmed et al., 2021). CFA is considered as an alternative source of various valuable resources. While natural resources are decreasing with time, CFA contains a variety of beneficial metals and mineral substances whose demand is increasing in industries (Sahoo et al., 2016). CFA is a potential alternative source for rare earth elements (REEs) and carbon nanoparticles, which are important components in various applications including high-technology (micro- and nano-technology) products and a variety of consumer goods such as cell phones, computers, fluorescent lighting, catalysis, permanent magnets, advanced defense technology, and medical devices (Dai et al., 2016; Silva et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2022).

CFA has demonstrated potential in agriculture due to its efficiency in modification of soil health and crop performance. It is valuable for soil amendment, thereby providing plant and animal nutrients and improving its chemical and physical characteristics. CFA can serve as a fertilizer for agricultural activities as it may contain essential elements such as Ca, P, K, S, Na, Mg, Zn, Fe, Cu, Co, Mo, and B that are beneficial for crop development (Mupambwa et al., 2015; Belviso, 2017). Unfortunately, although CFA is characterized by high total concentration of nutrients, its application in agriculture is limited by low bioavailability of these nutrients (Mupambwa, 2016). Furthermore, this product is characterised by toxic metals that may be taken-up by plants. Chemical and physical properties of CFA affect their options for re-usability. For example, 75% of the CFA must have carbon content, measured by the loss on ignition (LOI) of less than 4% and have a fineness of 45 μm or less. Some countries such as India and China have made significant progress with CFA utilization, but the amount remaining is still high and this remains an environmental risk. In South Africa, approximately 10% of the produced CFA is recycled and therefore the amount stocked is increasing daily due to much dependency on coal for generation of electricity. Million tons of stocked CFA is a potential hazard to the environment, hence it is paramount to find alternative means to mitigate environmental health challenges associated with its disposal. In South Africa, Eskom has embarked on CFA utilization project aimed at identifying markets that can require high usage of CFA and have proposed four applications including mine drainage treatment and backfilling, soil amelioration and land reclamation, road construction, and brick and cement development (Reynolds-Clausen, & Singh, 2019). The building and construction industry use CFA as a cement extender (blended cements) or as a supplementary cementation material. Substituting with CFA has significant economic benefit and it also enhances the concrete performance, allowing the use of less water (SACCA, 2021). Other sectors utilizing CFA in South Africa are the polymer and rubber industry and agriculture (Krueger, & Krueger, 2005). Converting CFA into reusable materials is an excellent strategy of reducing high volumes that need to be dumped into landfills, and consequently reducing the need for more storage space that is costly (Umejuru et al., 2020). However, presently far less CFA is recycled and these low utilization rate in South Africa and many other countries highlight the need for effective strategies to prevent further degradation of the ecosystem.

6. Treatment Methods of Contaminated Sites

Several remediation strategies are being applied for clean-up of contaminated soils and ash disposal sites but most of them are ineffective and expensive (Koul, & Taak, 2018; Sharma et al., 2018). Methods for the treatment of contaminated sites include biological, physical and chemical methods which have advantages and disadvantages as well. Remediation methods are dependent on the contaminant and environmental factors, therefore there is no single or combined treatment methods that can be effective for remediation of all pollutants under same environmental conditions (Yeung, 2010). In addition to the use of landfills, the major treatment and disposal strategies of CFA include stabilization and solidification, chemical treatment and heat treatment (Sharma et al., 2018; Liu, & Ren, 2021). The chemical and thermal techniques are technically difficult and not suitable for practical applications, because are often associated with high cost, poor efficiency and are dependent upon the pollutants in the substrate (Negri et al., 1996).

6.1. Chemical Remediation

This technology aims to alter the chemical characteristics of pollutants to decrease their hazardous properties. The most commonly known chemical remediation methods include chemical oxidation and extraction, nano-remediation, ion-exchange, soil amendment, precipitation, and chemical leaching (Sharma et al., 2018). Chemical fixation fixes toxic heavy metals in the contaminated site through adsorption resulting to less availability of them. It is not a permanent treatment as heavy metals can get released into the environment under conducive conditions of weathering. It also consists of addition of reagents into the polluted sites to form slightly insoluble materials (Yang, 2005; Dhaliwal et al., 2020). Chemical leaching is based on dissolving heavy metal ions into the acids such as H2SO4, HCl or HNO3 and extracting them out (Dermont et al., 2008). The limitation of this method is the need of large quantities of acids, which later require pre-treatment and therefore too costly. In the soil amendment technique which also called chemical fixation, the mobility and solubility of toxic heavy metals are reduced using chemical reagents such as FA (Sharma et al., 2018). Nano-remediation is suitable for clean-up of hazardous elements in industrial waste. The technology involves the complex formation of heavy metals with modified nanoparticles, followed by co-precipitation, and ultimate removal of toxicants from the contaminated media (Li et al., 2018; Sharma et al., 2018). The chemical oxidation is a remedial technique applied ex-situ and in-situ effectively used for treatment of organic pollutants (Oprea et al., 2009; Ranc et al., 2016; Liao et al., 2019). These methods require the use of oxidizing agents such as ozone, potassium permanganate, chlorine dioxide, hypochlorite, and hydrogen peroxide. The limitations of these methods include the production of secondary pollutants or by-products that need further processing and the need to use chemical reagents (Nam et al., 2008; Rada et al., 2019). Furthermore, the use of these treatments is associated with high costs (Istrate, 2009).

6.2. Physical Remediation

The treatment of contaminated sites via physical remediations include soil replacement, excavation and off-site disposal technology, vitrification and heat treatment (Zhou et al., 2004; Yeung, 2010; Sharma et al., 2018). Soil replacement technique is based on the reduction of contaminant levels through completely or partially replacing the polluted soils. Physical technique for migrating contaminated land and disposal in landfills is labour-intensive, quite expensive, time consuming and not commercially sustainable (Dhaliwalet al., 2020). Vitrifying technology consists of removing heavy metals through weathering process of organic matter by maintaining high temperature in the soils. This is a complicated technique which requires more energy, making it expensive and it has limited application Thermal desorption is suitable for treatment of most semi-volatile and volatile pollutants such as PCBs and PAHs. In this method, these organic pollutants in contaminated media are heated first to an appropriate temperature by indirect or direct heating under vacuum or into carrier gas to separate target pollutants from the substrate. The advantages of this technique include possibility of recycling soil and contaminants, high safety, high efficiency, short treatment period, and capability to treat different types of pollutants. However, this method produces off gases which can result in secondary contamination. This treatment method requires soil excavation and transportation that can create new contamination sources such as rainwater contamination, dust and noise (Kristanti et al., 2022). In addition, the other limitation is the high energy consumption and the resulting costs. In the excavation and off-site disposal technology, polluted soils are physically excavated and transported to disposal sites and treatment facilities, but this technology is not cost-effective (Yeung, 2010). Incineration method is a complex system representing an integrated system of components for waste preparation, feeding, combustion, and emission control. Thermal technology such as incineration method is a complex system that require utilizing electricity and therefore not a viable option for South Africa which is currently experiencing energy crisis. Remediation of polluted sites by biological methods can be advantageous to other methods as it does not require chemicals, cost-effective and no possibility of producing secondary pollutants. Bioremediation techniques involve the use of several animals, microorganisms and plants for remediation and has advantages over the traditional methods and therefore should be explored.

7. Phytoremediation Technology

Phytoremediation is emerging sustainable, esthetically suitable technology applicable to large areas, environmentally-friendly, and economical strategy compared to the conventional methods (Pandey et al., 2009; de Abreu et al., 2012; Asante-Badu et al., 2020). Phytoremediation processes involve the use of native or indigenous plant species (shrubs, trees, herbs, aquatic plants, and grasses) and associated microorganisms, together with agronomic and chemical techniques (chelating agents) for decontamination of contaminated sites in the environment (Del Rı́o et al., 2002; Asante-Badu et al., 2020). Different phytoremediation mechanisms include phytoextraction, phytostabilization, phytovolatilization, phytodegradation, and rhizodegradation (Park et al., 2011; Franchi et al., 2019). Understanding mechanisms involved in phyto-strategies is fundamental for success in implementing these technologies. Metal-contaminated sites are mainly rehabilitated using phytoextraction and phytostabilization. In phytoextraction, plants referred to as hyperaccumulators are used to remove toxic metals or organic pollutants from the soil by accumulating them in the aboveground parts of the plant (Elless et al., 2000; Xiang et al., 2022). Phytoextraction technology can be achieved via natural means and the chemically enhanced phytoextraction, which involve the use of chemical agents (Lombi et al., 2001). Phytostabilization processes makes use of plants to limit the movement of pollutants, thereby localising them in the roots (Lorestani et al., 2013). The phytostabilisation process can be aided through incorporation of amendments into the soil to reduce the labile pollutants and phytotoxicity prior to establishment of suitable species (Mench et al., 2006). Vegetation is effective in restricting the spread of pollutants, reducing wind dispersion and water erosion. While conventional methods disturb the physical properties of soil, the use of phyto-strategies maintains and improves the soil quality and structure (Salt et al., 1995; Perronnet et al., 2000). Phyto-technologies maintain soil development processes, stabilises microbial communities, therefore promoting soil ecosystem roles through reduction/stabilization of pollutants (Mench et al., 2010). Experimental trials, studying plant tolerance towards metals toxicity and tests under various amendments are essential before establishing a field-scale system. The ability to accumulate toxic metals varies greatly between species, and even between cultivars within a species (Salt et al., 1995; Chehregani et al., 2009). For the successful practical application of phytoremediation, the production of biomass, the metal content of the plant material and the time span (number of annual crops) needed to achieve the desired degree of remediation of the soil are considered (Robinson et al., 1998). In phytodegradation, organic pollutants such as PAHs are taken by roots and broken down into less toxic substances, such as CO2 and H2O through metabolic processes. Organic pollutants are also removed or reduced from the environment by phytovolatilization process in which organics are absorbed from the substrate and converted to gaseous substances that are released into the atmosphere through transpiration (Abhilash et al., 2009; Benavides et al., 2021). Rhizodegradation is a phytoremediation strategy that uses roots of plants that enhance microbial and fungal activity in the rhizosphere and breakdown organic pollutants (Ma et al., 2011). Plants facilitate degradation of organic pollutants by stimulating microbial activity releasing a class of defensive secondary metabolites (organic acids, sugars, amino acids, phenolics, and enzymes dehalogenase, nitroreductase, peroxidase, laccase (Ma et al., 2011). To enhance this process, a specific inoculum of microbes can be added to contaminated soils.

The effectiveness of phytoremediation technology depends on the selection of suitable plant species and a variety of environmental factors. Spatial variability of soil factors, e.g. total concentrations and labile pools of contaminants, texture and depth of soil layers, nutrient and water availability, problems with the homogeneous input of amendments, differences in rooting depth and density, variability of soil moisture, impacts of pests, pathogens and herbivores can affect both treatment efficiency and plant responses in the field (Friesl et al., 2006).

7.1. Challenges of Establishing Vegetation in CFA Polluted Sites

Revegetation has been reported as an efficient approach for stabilization and restoration of polluted sites, thereby protecting the environment. However, studies on CFA polluted sites are still poorly reported, possibly due to unfavorable physicochemical properties of CFA that do not support plant development. CFA contains nutrients, but are not bioavailable due to high pH values resulting from presence of hydroxides, carbonates, calcium and low Sulphur content (Pandey, & Singh, 2010; Ram, & Masto, 2014). Its alkaline pH limits the availability of nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus that are associated with plant growth (Gajić et al., 2018). The available phosphorus content in CFA is usually 0.05-0.2% due to complexation with Al and Fe. Nitrogen is estimated to be below 0.05% as most of it, is lost by volatilization and therefore restricting plant growth (Siddaramappa et al., 1994). Although cations including Ca, Na and K are available for plant physiological processes, high concentration of soluble salts is the plant growth limiting factor and requires a washing step, in order for plants to thrive. CFA is characterized by low water holding capacity, low organic carbon, lower numbers of microorganisms and fungi and presence of unacceptable levels of toxic elements (Haynes, 2009; Gajić et al., 2018). The challenge of growing plant on soils amended with FA is boron (B) toxicity because it contains high concentrations of B (Lee et al., 2008). Such plants accumulate high levels of B in its tissues due to excessive uptake and therefore resulting to phytotoxicity (Manoharan et al., 2010). The fine particles of FA forms compacted layers which leads to low aeration and water infiltration (Yang et al., 20220). Alkalinity of CFA can lead to excessive concentrations of selenium and that may hinder plant growth, results in chlorosis, burning of leaves, and oxidative stress (Sahoo et al., 2016). CFA is associated with limited microbial population which produces organic acids that increases bioavailability of nutrients. CFA also contains considerable amounts of toxic elements that can enter into the food chain (Izquierdo, & Querol, 2012). Depending on the coal used, CFA may have high levels of metals such As, Be, B, Cd, Cr, Co, and Pb which are potential threats to humans and the environment. Unacceptable levels of metals including Zn, Pb, Cu, Ni, Fe, Mn, As, Cr, and Cd are concentrated in CFA particles, and therefore its application on land is very risky (Kisku et al., 2018; Banerjee et al., 2020; Tang et al., 2021). The use of CFA in agriculture is therefore restricted because its repeated applications to the soil may lead to build-up of toxic metals over time.

7.2. Selection of Plant Species

Depending on the substrate and pollutants, selection of suitable plants species is a foundational need to be addressed. Species suitable for phytoremediation processes should be tolerant to the heavy metal toxicity and be able to produce a large biomass (Berti, & Cunningham, 2000). Fast growing species offer an advantage as they form massive green cover in reasonable less time and conserve moisture (Maiti, & Maiti, 2015). Plant that require less maintenance under field conditions and adapt to environmental factors including low water availability, low nutrients availability is more desirable (Burges et al., 2018). Native plants have the advantage of tolerance to local growth medium condition. For restoration of CFA deposits, it is more desirable to select species that limit movement of metals depending on the pollution load. In the avoidance strategy, plants limit uptake of heavy metals and restrict their movement into aerial parts through mechanisms including root sorption, metal ion precipitation and metal exclusion (Dalvi, & Bhalerao, 2013). Excluders restrict or limit the roots to uptake metals and translocation in high concentration of pollutants inside the plant tissue over a wide range of growth medium (soil or CFA) or substrate concentrations (Baker, 1981; Shi et al., 2016; Lam et al., 2018; Lago-Vila et al., 2019). They stabilise metals in the growth medium (phyto-stabilization), reduce the mobility and bioavailability of organic and inorganic pollutants, preventing pollution of surface and groundwater and subsequent entry into the food chain (Nwoko, 2010; Kostić et al., 2022). Studies have profiled a number of species growing in the vicinity of CFA dams, but these should be tested in the field trials for longer periods in order to determine their effectiveness in phytoremediation processes. It is also important to select species based on their ecological importance, dominance at the site under investigation and socio-economic importance for community upliftment (Pandey et al., 2014).

7.3. Nanotechnology-Assisted Phytoremediation

Phytoremediation, in combination with nanotechnology, has potential for efficient clean-up of polluted sites (Pandey et al., 2023). Nano-phytoremediation is a new emerging technology and gaining interest for restoration of polluted sites through the use of biosynthesized nanoparticles (Das et al., 2022). Nanomaterials have unique physicochemical properties such as large surface area, more active sites, and high adsorption efficiency that enhance the application of phyto-strategies for clean-up of polluted substrates (Gul et al., 2023). This approach has shown potential to enhance biomass production for plants growing in a polluted environment and improve plants capability to accumulate toxic metals in their tissues (Srivastava et al., 2021; Sánchez-Castro et al., 2023). Nanoparticles can enhance plant growth and stabilize contaminants through augmenting antioxidant activities (Ojuederie et al., 2022). A variety of laboratory trials have been reported for the application of nanomaterials on plants for removal of toxic pollutants (Srivastav et al., 2019). Silicon nanoparticles application is effective in increasing wheat grain biomass and yield while reducing toxicity of Cd in plants (Hussain et al., 2019). Nanoscale zero-valent iron has proven to be effective in phytoremediation processes and therefore widely investigated in remediation of contaminated soil and groundwater (Song et al., 2019). Huang et al. (2018) discovered that application of zero-valent iron nanomaterials improved Pb accumulation in ryegrass, therefore enhancing the removal of Pb from the environment. Although nanomaterials have demonstrated advantages in restoration processes, they are potential environmental hazards, especially in soil microbial communities (Simonin et al., 2015; Song et al., 2019). Although there are toxicity concerns with the use of nanomaterials in phytoremediation processes, this can be a beneficial strategy and therefore further research is needed to develop effective and safer approaches for rehabilitation of polluted sites.

8. Approaches in Phytoremediation of CFA-Polluted Sites

The occurrence of naturally-growing plants near CFA dumpsites has opened doors for opportunities to explore phytoremediation strategies for reclamation of these unproductive sites (Saljnikov et al., 2022). Plants growing on coal combustion waste landfill were evaluated for their phytoremediation potential. The tree species (Betula pendula Roth, Populus tremula L.) and the herbaceous species (Solidago virgaurea L.) were effective at accumulating Cd and Zn, but low accumulation for Pb and Cu highlighting the species are specific at accumulating pollutants and therefore the tested species have potential in eco-restoration of ash deposits polluted with Cd and Zn (Szwalec et al., 2022). Studies on plants that can tolerate such harsh conditions, pave a way for identification of species that can solve problems associated with CFA disposal. Plantation will remediate CFA dump areas and also add to the sparse vegetation on the disposal sites. The undesirable properties of CFA restrict the establishments of vegetation in CFA disposal site, but these can be overcome by identifying ideal species and the use of organic amendments, which have no health risks associated with their use. Plant growth in CFA is limited due to undesirable characteristics including restricted movement of water to plants, low availability of nutrients, high pH values, water holding nature, low organic matter and microbial activities. Plant-microbe interactions contribute significantly to improved soil structure, nutrient cycling and nutrient uptake (Rosario et al., 2007).

Various amendments are required to improve unfavorable CFA physicochemical properties such as high pH that is linked to unavailability of nutrients and low organic matter content (Larney, & Angers, 2012; Pandey, & Singh, 2012). Organic matter sources include fertilizers, sewage sludge, compost, sludges, and manures from wastewater treatment plants, bacterial inoculum and dairy sludge (Jain, & Tembhurkar, 2022). Organic matter plays a variety of roles including improved soil structure, reduced erosion, and it also increases infiltration. The organic matter may be composed of wood chips, straw, biosolids, composted municipal waste. Organic matter such as leaves or wood improving porosity allowing unrestricted movement of air and water (Carlile et al., 2010). The organic matter retain moisture, allow slow release of nutrients and is the source of food for microorganisms. Depending on the organic matter source applied, the addition of organic matter can lead to increased amounts of nitrogen and phosphorus which are lacking in CFA. Nutrient support through fertilizers and manures provides the possibility of effective remediation and the nutrients to the matrix combination within a lesser time. The use of compost as an organic amendment effects the plants differently for each species. In composting, the compost consisting of nutrients for the native microbes present in the polluted substrate and can increase the water-holding capacity and the cation exchange capacity (Chen et al., 2015). The composts can act as both bioremediation technique and soil amendment agents, in which the microbes employ these nutrients for the remediation of pollutants present. Amendment through the addition of compost results in improved toxic metal uptake (González et al., 2019). Application of fertilizers in phytoremediation can improve plant biomass and improve the plant absorption of toxicants (Wu et al., 2019). It is noteworthy to mention that native vegetation is often adapted to low nutrients conditions and tends to respond negatively to increased nutrients levels due to fertilizer input (Piha et al., 1995). To increase efficiency, contaminated sites were found more effectively remediated by implementing the microbes isolated from the polluted sites. Microbes assist in increasing the absorptive surface area of the plant species. The addition of bioinoculants and microbes can establish an ecological system including complex substrates and plants (Jain, & Tembhurkar, 2022). Plants growing on weathering CFA provide favorable conditions for plant growth (Weber et al., 2015; Gajić, & Pavlović 2018). In weathering CFA, electrical conductivity values are higher, the nutrients levels are increased, the organic content is lower and the pH is decreased (Gajic et al. 2016). Amendments are an effective means for further research and development of phyto-strategies for preservation of the ecosystem (Jain, & Tembhurkar, 2022). It is important to note that, amendment can cause further environmental pollution problems through leaching of ions, resulting to groundwater contamination. Treatments such as the addition of fertilizers, composts, and manure are effective in enhancing the availability of nutrients, but can also increase levels of toxic metals that will be source of pollution problems over time (Zhang et al., 2010) and therefore the safety of the selected amendment should be established prior to application.

9. Plant Species with Potential in the Phytoremediation of CFA Polluted Sites

Solid waste management including CFA disposal has resulted in significant loss of flora and destruction of the ecosystem. Pollution stress due to CFA negatively impacts the plant normal physiological processes and hence the selection of plant species is an important factor in phytoremediation processes (Qadir et al., 2016). There are no plants that have universal applications for phytoremediation processes due to differences in site conditions. A variety of plant species naturally grow in close proximity of ash disposal sites and this paved the way for researchers to explore phytoremediation technology for restoration of CFA polluted lands and potential generation of revenues. Native plants have developed survival mechanisms appropriate to the environmental conditions. Plant species that are naturally growing in CFA deposits open doors for selection of suitable candidates for restoration processes as they are mostly reported to contain high levels of toxic metals in their plant tissues. Ideal plant species should be able to self-propagate successfully with no additional inputs (Mendez, & Maier 2008).

Table 2 lists a number of colonizing plants of CFA dumping sites with potential in rehabilitation processes. The naturally colonizing plants were examined based on their wide occurrence, their capabilities in improving the properties of the rhizospheric CFA to support plant growth and ecological significance for their potential in restoration of CFA dumping sites (Yadav et al., 2022). This information can be useful in identifying species that can be explored for phytoremediation processes, especially in countries having high volumes of CFA remaining, posing serious environmental health risks. Selection of suitable species depends mostly on the concentration of pollutants, environmental conditions and restoration aims in terms of both intended use of land and financial return (Mench et al., 2012). Although CFA dumpsites are known to contain low levels of nutrients and organic matter, vegetation by

S. spontaneum resulted to increased organic matter, N, P and K, which is attributed to fine root decay of the grass and the presence of phosphate solubilizing bacteria or mycorrhizal communities in revegetated sites (Pandey et al., 2014).

Grasses, legumes, shrubs and trees have gained interest from researchers for their potential in restoration of CFA deposits due to their potential in changing the properties of CFA, thus increased biomass, tolerance towards metal toxicity and potential economic benefits.

9.1. Grasses

In the initial stage of phytoremediation processes, the species selected must be tolerant or resistant to pollutants present or conditions in the substrate. Grasses have wide fibrous root systems, which prevent erosion and tolerate harsh growing conditions such as in CFA and therefore suitable for restoration strategies (Maiti, 2013). They stabilize toxicants through absorption in their roots and translocation to the aerial parts and therefore their cultivation can diminish water, land and air pollution and prevent dust flow. Cynodon dactylon pers. (L.) (Bermuda grass) demonstrated phytoremediation potential for the phytoextraction of Cd and degradation of PAHs (Song et al., 2022). This species was reported to be amongst the species that naturally colonised CFA damps and accumulated toxic concentration of Cd (Maiti, & Pandey, 2021). Cyperus rotundus L., is a metal-tolerant plant species which grows well on metal-contaminated CFA deposits (Mukhopadhyay et al., 2018). The phytoremediation potential of Azolla caroliniana (water fern), which naturally occur in CFA dams was demonstrated by high bioconcentration factor (BCF) values for Pb, Fe, Mn, Ni, Cr, Zn, Cd, and Cu that ranged from 1.7 to 18.6 (Pandey et al., 2012). Vetiver (Vetiveria zizanioides) demonstrated phytostabilization potential after being grown on CFA for a period of three months and the plant had massive growth of roots (Chakraborty, & Mukherjee, 2011). The high porosity and low density of CFA facilitate root growth in Vetiver zizanioides, which is a commercial part of these plant. Higher biomass may be obtained from CFA dumps as compared to other wastelands because poor soil structure restricts root development and growth, and root breakage occurs during its digging (Verma et al., 2014). Field trial by Pandey et al. (2012) showed that Saccarum munja grows well on abandoned FA lagoons and its roots increased from 3.48 to 4.57 m deep and produced high biomass. Similarly, Kumar et al. (2015) reported the accumulation and translocation of Ni, Zn, Cu, Fe, and Pb by Cynodon dactylon and S. munja. Saccharum spontaneum is a tall (100-600 cm) perennial grass with deep roots and high biomass productivity that is suitable for restoration and stabilization of ash deposits (Pandey et al., 2014). Vegetation with S. spontaneum improves porosity, water holding capacity, decrease pH and conductivity and consequently enhances nutrients availability. Grasses can be mixed with trees, as they present financial gains. It is imperative that planting is approached in a manner that minimize competition for water and nutrients between trees and grasses.

9.2. Legumes

CFA is characterised by a variety of essential nutrients including Ca, Fe, K, Mn, Na, S, and P, which play important roles in plants physiological processes. However, it is known to contain very low levels of nitrogen and reduced nitrogen-fixing microorganisms restricting plant growth. Although some nutrients are present in high levels, their unavailability is due to high pH, but that can be overcome by the use of leguminous species that release hydrogen ions that can reduce the pH of the substrate. Legumes have gained interest in phytoremediation strategies due to the nitrogen fixing capabilities, which will change the physicochemical properties of the CFA (Teng et al., 2015). Legumes change soil properties through the symbiotic association with microorganisms, such as rhizobia, which fix the atmospheric nitrogen and therefore increasing the available nitrogen in soil (Kebede, 2021). Leguminous species are heavy-metal resistant and can significantly reduce organic pollutants such as PCBs, PAHs and herbicides by degradation mechanism (Lee et al., 2008; Teng et al., 2015; Rai et al., 2021; Xiang et al., 2022). Ideal species for phytoremediation should possess the characteristic of fast growth and accumulation of biomass, but studies report unavailability of nutrients as the limiting factors for plant growth on CFA media. This problem is overcome by nitrogen-fixing legumes that decreases the pH of CFA, thereby allowing increasing bioavailability of nutrients. The presence of ammonium ions and nitrates contributes greatly to plant development. Studies on legumes’ potential for phytoremediation strategies have demonstrated that, these species modify the substrate properties and therefore making the growth media conducive for plants to thrive. Legumes have great potential in phytoremediation processes because they enhance the number of microbial populations and can make fixed nutrient available to other crops (Gajić et al., 2018).

The use of legumes in phytoremediation strategies provides economically feasible and environmentally-friendly strategy to reduce the use of chemical amendments in a bid to improve soil characteristics. A variety of species have been tested for clean-up of polluted soils, but little attempts made for CFA deposits restoration. For examples,

Lotus corniculatus belonging to the Leguminosae family was successfully used for soil restoration contaminated with crude oil (Morariu et al., 2016).

Medicago lupilina has phytostabilization potential due to its ability to accumulate high concentration of Pb, Ni and Zn in its root tissues and high biomass production (Amer et al., 2012; Lajayer et al., 2017). Legumes have been widely reported in phytoremediation strategies and their capabilities to change the properties of CFA highlight immense potential in the restoration of CFA deposits. The few species listed in

Table 3 have proven capabilities in restoration of polluted soils and therefore are promising candidates that deserves to be explored for their application in the restoration of CFA dams as they have an advantage of improving soil fertility without any external input as compared to non-leguminous species. These species were tested in metal-contaminated soils and mine tailings and therefore are ideal for restoring lands that are currently storing CFA.

Acacia nilotica is an ecologically, economically and socially important Leguminosae tree species that has phytoremediation potential of contaminated soils with Cd (Rahat et al., 2018; Amadou et al., 2020). The products derived from this species such as fuel, gum, fodder, and drugs can be used as green manure to enhance soil fertility, to adapt to climate change and to fight against societal poverty in the rural areas (Amadou et al., 2020). Such approach is beneficial for sustainable development of communities.

9.3. Grass-Legume Mixture

Strategies are being explored with the use of microbial inoculants and inclusion of different plants such as legume-grass mix and inclusion of wastewater (Jain, & Tembhurkar, 2022). Grass-legume mix is efficient as they can readily colonize the polluted site and develop a thick vegetation cover within a reasonable timeframe. The advantage of these combination is the creation of nitrogen balance in the substrate. By comparing with other species grown in low nutrient media, legumes have a higher decomposition over grasses and therefore thrive much better (Agbenin, & Adeniyi, 2005; Pérez-Esteban et al., 2014). Legumes survive harsh conditions caused by contaminants better than grasses (Lee et al., 2008b). The grass-legume mixture is effective in the restoration of waste disposal site with the inclusion of topsoil and coir-mat (Maiti, & Maiti, 2015). This approach has shown potential in restoration of CFA deposits, and therefore should be explored for the benefit of the environment and restoration of the ecosystem.

9.4. Aromatic Plants

Phyto-strategies are now being approached in a manner that enable solving problems simultaneously, i.e restoration and revenue generation. Aromatic grasses are perennial in nature with multiple harvests, commercial/industrial crops, unpalatable, and tolerant to stress conditions such as drought, heavy metal toxicity and unfavourable pH (Gupta et al., 2013). Aromatic plants offer a novel option for use in phytoremediation of heavy metal polluted sites (Panda et al., 2018; Banda et al., 2023). These species are gaining interest in phytoremediation strategies as they can grow in metal-contaminated sites and can also produce high value essential oils (EOs) (Verma et al., 2014; Pandey et al., 2019). The EOs from aromatic crops are being used in perfumery, detergent and soap manufacturing, insect repellents, personal care product and cosmetic industries. Aromatic grasses such as Vetiveria zizanioides, Vetiveria nigritana, Cymbopogon martinii, Cymbopogon winterianus, and Cymbopogon flexuosus are high-value plants due to their high biomass production and abilities to produce EOs (Bhuiyan, Chowdhury, & Begum, 2008; Chandrashekar, & Prasanna, 2010; Verma et al., 2014). Vetiver zizanoides and Mentha arvensis were effectively planted in CFA used in conjunction with mycorrhiza and 20% farmyard manure (Adholeya et al., 1997; Sharma et al., 2001; Kumar, & Patra, 2012). Aromatic grasses synthesize EOs in their specific plant parts like leaves and inflorescence (C. martinii), roots (V. zizanioides) and leaves (C. flexuosus and C. winterianus) (Verma et al., 2014; Panda et al., 2018). The EOs are extracted through hydrodistillation and therefore the oil produced is free from metals (Zheljazkovm et al., 2006; Lal et al., 2013; Pruteanu, & Muscalu, 2014). Shrubs have been tested in phytoremediation strategies and have shown their effectiveness in many phyto-strategies. Many field trials have focused on monoculture, limiting survival of species and vegetation cover. These challenges can be overcome by establishing a diverse plant community and inoculation of various microorganism. Aromatic shrubs can be grown together with grasses as they provide vegetation cover, immobilizing pollutants, whilst shrubs are being established. Shrubs and trees establish a deeper root network to prevent erosion and they may enhance nutrient availability for grasses, whilst reducing water deficiency and improving soil properties (Mendez, & Maier, 2008).

Aromatic plants are not edible and are not being consumed directly by animals and humans like vegetables, pulses and cereals and therefore there is a low risk of entering the food chain. Furthermore, grazing animals do not feed on aromatic plants due to their essence and are therefore abundant and can be used on a large scale (Gupta, 2013). Global request of herbal products, in which EOs from aromatic herbs contribute considerably, is exponentially growing and it is projected to reach 5 trillion U.S. dollars by the end of year 2050 (Verma et al., 2014). Tests should be conducted on EOs produced to ensure the safe use of these products. Cultivation of aromatic plants on CFA dumping sites is economically viable and recommended (Banda et al., 2023). This is an environment-friendly approach and economically feasible for the management of CFA landfills. Although there are economic advantages and low contamination risk of growing EO producing plants on CFA disposal sites, research on these species is poorly investigated and deserves attention.

9.5. Biomass Producing Plant-Energy Resources

Plants producing oil or biomass for biofuel, fibres (e.g. flax, Miscanthus and hemp) and quality hardwood can provide a financial return (Vangronsveld et al., 2009). The forestry sector uses CFA damping sites for growing trees that have economic benefits such as paper and pulp trees, timber wood, biodiesel crops, etc. as a way to preserve the environment in a sustainable manner (Pandey, & Singh, 2009; Maiti, & Prasad, 2016). Rapeseed varieties have been successfully reported as oil crops and biofuel resources represent a sustainable option for land use (Vangronsveld et al., 2009). Seeds and oil are known to be characterised by negligible concentration of toxic metals and therefore food chain contamination is limited.

Conclusion and Future Prospects

The production of CFA will continue to increase globally due to much dependency on coal combustion for energy generation. Although CFA utilization is reported, more than 200 million tons of CFA remain untreated yearly and problems related to their disposal will continue to pose environmental problems. CFA disposal leads to land degradation, loss of vegetation, worsening of air quality and negatively affecting the health of humans, animals and the environment. The use of phytoremediation strategies by cultivating plants on CFA dumpsites has great potential for reclamation of degraded lands and possibly converting them to valuable sites and restoration of the ecosystem. More studies are needed to assess the suitability of various plants species for phytoremediation strategies. An engineered sustainable ecosystem should be developed with the aid of tolerant plant species which would provide vegetative cover. Unfavorable conditions limiting plant development, can be overcome by a mix of legumes with other species as they can improve CFA properties to support the growth of plants. Furthermore, organic amendments can overcome problems relating to nutrient deficiency, while exploring nanotechnology can assist in enhancing plant growth and reducing toxicity of metals in plants. The use of aromatic plants offers an advantage as they produce commercially valuable essential oils which can convert unproductive lands to valuable sites. Phytotechnologies can offer cost-effective tools and environmentally-friendly solutions for restoration of polluted sites, tools to reduce global warming through carbon sequestration, means for recovery of valuable products that can contribute to sustainable development of communities. The insights provided in this review is relevant in guiding future research for restoration of CFA dumping sites, particularly in countries that report low usage.

References

- Abhilash PC, Pandey VC, Srivastava P, Rakesh PS, Chandran S, Singh N, Thomas, AP (2009). Phytofiltration of cadmium from water by Limnocharis flava (L.) Buchenau grown in free-floating culture system. J Hazard Mater 170(2-3):791-797. [CrossRef]

- Adewuyi YG (2021). Recent Advances in Fly-Ash-Based Geopolymers: Potential on the Utilization for Sustainable Environmental Remediation. ACS Omega 6 (24):15532-15542. [CrossRef]

- Adholeya A, Verma A, Bhatia NP (1997). Influence of media gelling agents on root biomass and in vitro VA-Mycorrhizal symbiosis of carrot with Gigaspora margarita. Biotropia 10:63-74. [CrossRef]

- Agbenin, J. O., & Adeniyi, T. (2005). The microbial biomass properties of a savanna soil under improved grass and legume pastures in northern Nigeria. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 109(3-4), 245-254. [CrossRef]

- Ahmaruzzaman, M. (2010). A review on the utilization of fly ash. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science, 36(3), 327-363. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H. U., Mohammed, A. A., Rafiq, S., Mohammed, A. S., Mosavi, A., Sor, N. H., & Qaidi, S. M. (2021). Compressive strength of sustainable geopolymer concrete composites: a state-of-the-art review. Sustainability, 13(24), 13502. [CrossRef]

- Ahmedi, F., & Kusari, L. Coal Combustion Byproducts and Their Usage–Water Field. SEEU Review, 8(2), 16-26. [CrossRef]

- Alegbe J, Ayanda OS, Ndungu P, Alexander N, Fatoba OO, Petrik LF (2018). Chemical, mineralogical and morphological investigation of coal fly ash obtained from Mpumalanga Province, South Africa. https://hdl.handle.net/10210/271555. Accessed 23 September 2023.

- Alonso JL, Wesche K (1991). Characterization of fly ash. Fly ash in concrete. London: Taylor and Francis, 3-23.

- Alterary SS, Marei NH (2021). Fly ash properties, characterization, and applications: A review. J King Saud Univ Sci 33(6):101536. [CrossRef]

- Altıkulaç A, Turhan Ş, Kurnaz A, Gören E, Duran C, Hançerlioğulları A, Uğur FA (2022) Assessment of the Enrichment of Heavy Metals in Coal and Its Combustion Residues. ACS Omega 7:21239-21245. [CrossRef]

- Amadou I, Soulé M, Salé A (2020). An overview on the importance of Acacia nilotica (L.) willd. ex del.: A review. Asian J Res in agricultur for 5(3):12-18. [CrossRef]

- Amer N, Chami ZA, Bitar LA, Mondelli D, Dumontet S (2013). Evaluation of Atriplex halimus, Medicago lupulina and Portulaca oleracea for phytoremediation of Ni, Pb, and Zn. Int J Phytoremediation 15(5):498-512. [CrossRef]

- Andrade SA, Abreu CA, De Abreu MF, Silveira APD (2004). Influence of lead additions on arbuscular mycorrhiza and Rhizobium symbioses under soybean plants. Appl Soil Ecol 26(2):123-131. [CrossRef]

- Anjum NA, Gill SS, Tuteja N (2017) Enhancing clean-up of environmental pollutants. Cham, Switzerland. [CrossRef]

- Asante-Badu B, Kgorutla LE, Li SS, Danso PO, Xue Z, Qiang G (2020) Phytoremediation of organic and inorganic compounds in a natural and an agricultural environment: a review. Appl Ecol Environ Res 18(5). [CrossRef]

- Baker AJ (1981) Accumulators and excluders-strategies in the response of plants to heavy metals. J. Plant Nutr 3(1-4):643-654. [CrossRef]

- Banda M, Munyengabe A, Augustyn W (2023) Aromatic Plants: Alternatives for Management of Crop Pathogens and Ideal Candidates for Phytoremediation of Contaminated Land. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee R, Jana A, De A, Mukherjee A (2020) Phytoextraction of heavy metals from coal fly ash for restoration of fly ash dumpsites. Bioremediat J 24(1):41-49. [CrossRef]

- Barescut J, Lariviere D, Stocki T, Pandit GG, Sahu SK, Puranik VD (2011) Natural radionuclides from coal fired thermal power plants–estimation of atmospheric release and inhalation risk. Radioprotection 46(6):173-179. [CrossRef]

- Basu M, Pande M, Bhadoria PBS, Mahapatra SC (2009) Potential fly-ash utilization in agriculture: a global review. Prog Nat Sci 19:1173-1186. [CrossRef]

- Bayat O (1998). Characterisation of Turkish fly ashes. Fuel, 77:1059-1066. [CrossRef]

-

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-2361(97)00274-3.

- Bhatt A, Priyadarshini S, Mohanakrishnan AA, Abri A, Sattler M, Techapaphawit S (2019) Physical, chemical, and geotechnical properties of coal fly ash: A global review. Case Stud. Constr. Mater 11:00263. [CrossRef]

- Belviso C, Cavalcante F, Lettino A, Fiore S (2011). Effects of ultrasonic treatment on zeolite synthesized from coal fly ash. Ultrason Sonochem 18:661-668. [CrossRef]

- Benavides BJ, Drohan PJ, Spargo JT, Maximova SN, Guiltinan MJ, Miller DA (2021) Cadmium phytoextraction by Helianthus annuus (sunflower), Brassica napus cv Wichita (rapeseed), and Chyrsopogon zizanioides vetiver). Chemosphere 265:129086. [CrossRef]

- Bentz DP, Durán-Herrera A, Galvez-Moreno D (2011) Comparison of ASTM C311 strength activity index testing versus testing based on constant volumetric proportions. J. ASTM Int 9:1-7. [CrossRef]

- Berti WR, Cunningham SD (2000) Phytostabilization of metals. Phytoremediation of toxic metals: using plants to clean up the environment. Wiley, New York, 71-88.

- Bhuiyan MNI, Chowdhury JU, Begum J (2008). Essential oil in roots of Vetiveria zizanioides (L.) Nash ex Small from Bangladesh. Bangladesh J Bot 37:213-215.

- Bilski J, McLean K, McLean E, Soumaila F, Lander M (2011) Environmental health aspects of coal ash phytoremediation by selected crops. Int J Environ Sci 1:2028-2036.

- Bilski J, Jacob D, Mclean K, McLean E, Lander M (2012) Preliminary study of coal fly ash phytoremediation by selected cereal crops. Adv Biomed Res 3:176-180.

- Bouaissi A, Li LY, Abdullah MM, Ahmad R, Razak RA, Yahya Z (2020) Fly ash as a cementitious material for concrete. Zero-Energy Buildings-New Approaches and Technologies. [CrossRef]

- Burges A, Alkorta I, Epelde L, Garbisu C (2018) From phytoremediation of soil contaminants to phytomanagement of ecosystem services in metal contaminated sites. Int. J. Phytoremediation 20:384-397. [CrossRef]

- Carlile A, Nadiger S, Burken J (2013) Effect of Fly Ash on Growth of Mustard and Corn. Biosci Biotechnol Res Asia 10:551-557. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty R, Mukherjee A (2011) Technical note: Vetiver can grow on coal fly ash without DNA damage. Int J Phytoremediation 13:206-14. [CrossRef]

- Chandrashekar KS, Prasanna KS (2010) Analgesic and anti-inflammatory activities of the essential oil from Cymbopogon flexuosus. Pharmacogn J 2:23-25. [CrossRef]

- Chehregani A, Noori M, Yazdi HL (2009) Phytoremediation of heavy-metal-polluted soils: Screening for new accumulator plants in Angouran mine (Iran) and evaluation of removal ability. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 72:1349-1353. [CrossRef]

- Chen M, Xu P, Zeng G, Yang C, Huang D, Zhang J (2015) Bioremediation of soils contaminated with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, petroleum, pesticides, chlorophenols and heavy metals by composting: applications, microbes and future research needs. Biotechnol Adv 33:745-755. [CrossRef]

- Cokc, E, Yilmaz Z (2004) Use of rubber and bentonite added fly ash as a liner material. Waste Management 24:153-164. [CrossRef]

- Dai, S., Graham, I. T., & Ward, C. R. (2016). A review of anomalous rare earth elements and yttrium in coal. Int J Coal Geol 159:82-95. [CrossRef]

- Dalvi AA, Bhalerao SA (2013) Response of plants towards heavy metal toxicity: an overview of avoidance, tolerance and uptake mechanism. Ann Plant Sci 2:362-368.

- Das S, Mondal UM, Paul S (2022) Nanophytoremediation technology: A better approach for environmental remediation of toxic metals and dyes from water. Elsevier, pp 459-481. [CrossRef]

- de Abreu CA, Coscione AR, Pires AM, Paz-Ferreiro J (2012) Phytoremediation of a soil contaminated by heavy metals and boron using castor oil plants and organic matter amendments. J Geochem Explor 123:3-7. [CrossRef]

- Del Rı́o M, Font R, Almela C, Vélez D, Montoro R, Bailón ADH 2002. Heavy metals and arsenic uptake by wild vegetation in the Guadiamar river area after the toxic spill of the Aznalcóllar mine. J Biotech 98:125-137. [CrossRef]

-

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1656(02)00091-3.

- Department of Energy (DoE) (2016). https://www.energy.gov.za/files/Annual%20Reports/DoE-Annual-Report-2016- 17.pdf. Accessed on the 3rd October 2023.

- Dermont G, Bergeron M, Mercier G, Richer-Laflèche M (2008) Soil washing for metal removal: a review of physical/chemical technologies and field applications. J Hazard Mater 152:1-31. [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal SS, Singh J, Taneja PK, Mandal A (2020) Remediation techniques for removal of heavy metals from the soil contaminated through different sources: a review. Environ Sci Pollut Res 27:1319-1333. [CrossRef]

-

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-06967-1.

- Diaz G, Azcón-Aguilar C, Honrubia M (1996) Influence of arbuscular mycorrhizae on heavy metal (Zn and Pb) uptake and growth of Lygeum spartum and Anthyllis cytisoides. Plant Soil 180:241-249. [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi A, Jain MK (2014) Fly ash–waste management and overview: A Review. Recent Recent Res Sci Technol 6(1).

- Elless MP, Blaylock MJ, Huang JW, Gussman CD (2000) Plants as a natural source of concentrated mineral nutritional supplements. Food Chem 71:181-188. [CrossRef]

- El-Mogazi D, Lisk DJ, Weinstein LH (1988) A review of physical, chemical, and biological properties of fly ash and effects on agricultural ecosystems. Sci Total Environ 74:1-37. [CrossRef]

- Engqvist LG, Mårtensson A, Orlowska E, Turnau K, Belimov AA, Borisov AY, Gianinazzi-Pearson V (2006) For a successful pea production on polluted soils, inoculation with beneficial microbes requires active interaction between the microbial components and the plant. Acta Agric Scand B Soil Plant Sci 56:9-16. [CrossRef]

- Eskom Report (2018). http://www.eskom.co.za/IR2018/Documents/Eskom2018IntegratedReport.pdf. Accessed 03 October 2023.

- Faisal M, Hasnain S (2006) Growth stimulatory effect of Ochrobactrum intermedium and Bacillus cereus on Vigna radiata plants. Lett Appl Microbiol 43:461-466. [CrossRef]

- Feng Y, Zhang Q, Chen Q, Wang D, Guo H, Liu L, Yang Q (2019) Hydration and strength development in blended cement with ultrafine granulated copper slag. PLoS One 14:0215677. [CrossRef]

- Franchi E, Cosmina P, Pedron F, Rosellini I, Barbafieri M, Petruzzelli G, Vocciante M (2019) Improved arsenic phytoextraction by combined use of mobilizing chemicals and autochthonous soil bacteria. Sci Total Environ 655:328-336. [CrossRef]

- Fu J (2010) Challenges to increased use of coal combustion products in China. MSc dissertation.

- Ghassemi M, Andersen PK, Ghassemi A, Chianelli RR (2004) Hazardous waste from fossil fuels. [CrossRef]

- Gajaje K, Ultra VU, David PW, Rantong G (2021) Rhizosphere properties and heavy metal accumulation of plants growing in the fly ash dumpsite, Morupule power plant, Botswana. Environ Sci Pollut Res 28:20637-20649. [CrossRef]

-

https://doi:10.1007/s11356-020-11905-7.

- Gajić G, Djurdjević L, Kostić O, Jarić S, Mitrović M, Stevanović B, Pavlović P (2016) Assessment of the phytoremediation potential and an adaptive response of Festuca rubra L. sown on fly ash deposits: Native grass has a pivotal role in ecorestoration management. Ecol Eng 93:250-261. [CrossRef]

- Gajić G, Djurdjević L, Kostić O, Jarić S, Mitrović M, Pavlović P (2018) Ecological potential of plants for phytoremediation and ecorestoration of fly ash deposits and mine wastes. Front Environ Sci 6:124. [CrossRef]

- Gajić G, Pavlović P (2018) The role of vascular plants in the phytoremediation of fly ash deposits. Phytoremediation: methods, management and assessment pp151-236.

- Gasparotto J, Martinello KDB (2021). Coal as an energy source and its impacts on human health. Energy Geosci 2:113-120. [CrossRef]

- Ghosal S, Self SA (1995) Particle size-density relation and cenosphere content of coal fly ash. Fuel 74:522-529. [CrossRef]

- Golubev IA (2011) Handbook of phytoremediation. Hauppauge, NY, USA: Nova Science Publishers.

- González Á, García-Gonzalo P, Gil-Díaz MM (2019) Compost-assisted phytoremediation of As-polluted soil. J Soils Sediments 19:2971-2983. [CrossRef]

-

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-019-02284-9.

- Gul MZ, Rupula K, Beedu SR (2022) Nano-phytoremediation for soil contamination: An emerging approach for revitalizing the tarnished resource, Phytoremediation, Academic Press, pp 115-138. [CrossRef]