Submitted:

04 January 2025

Posted:

07 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Antibodies

2.2. Preparation of cell lines

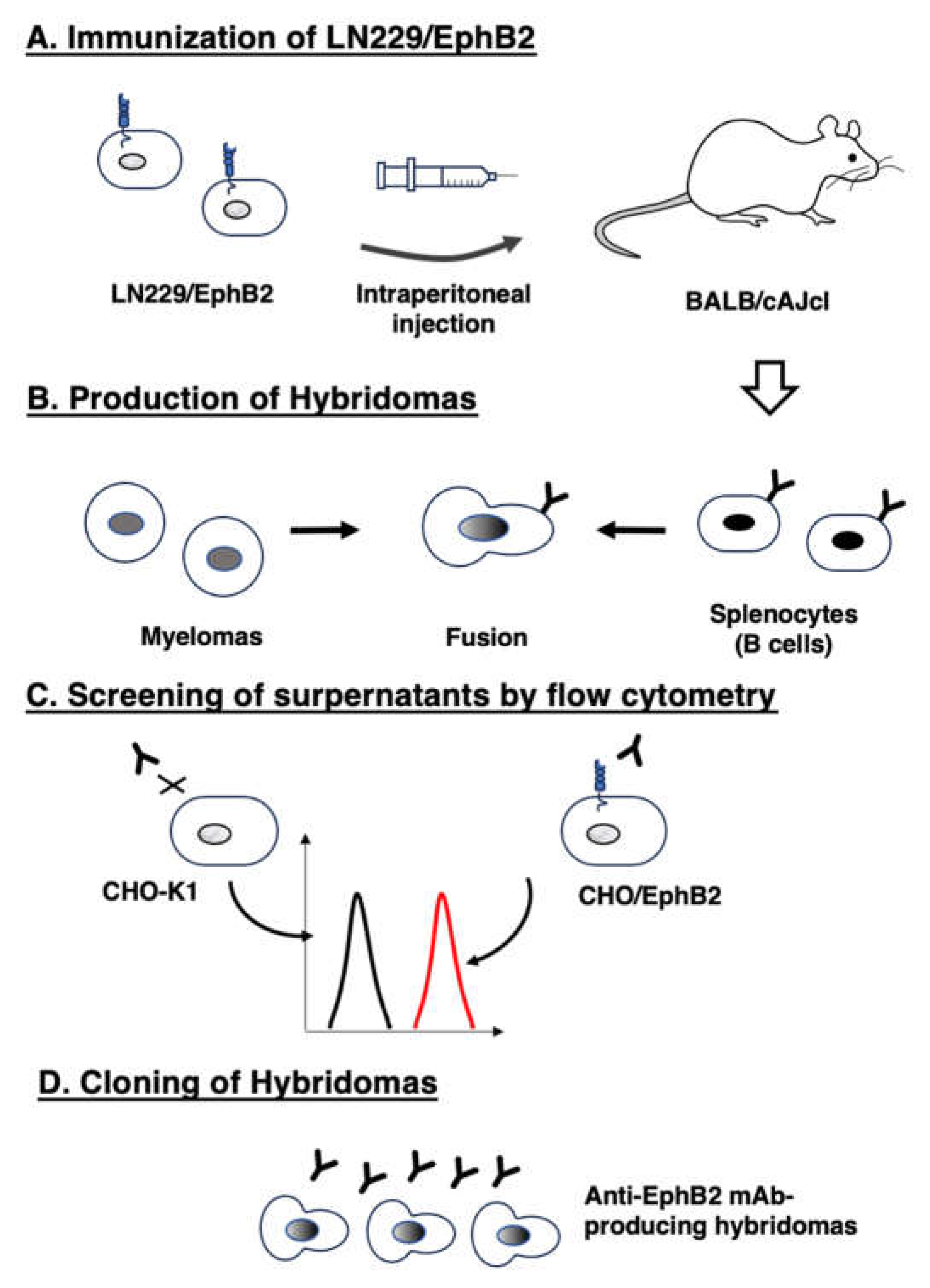

2.3. Development of hybridomas

2.4. Flow cytometric analysis

2.5. Determination of dissociation constant (KD) by flow cytometry

3. Results

3.1. Development of anti-EphB2 mAbs using the CBIS method

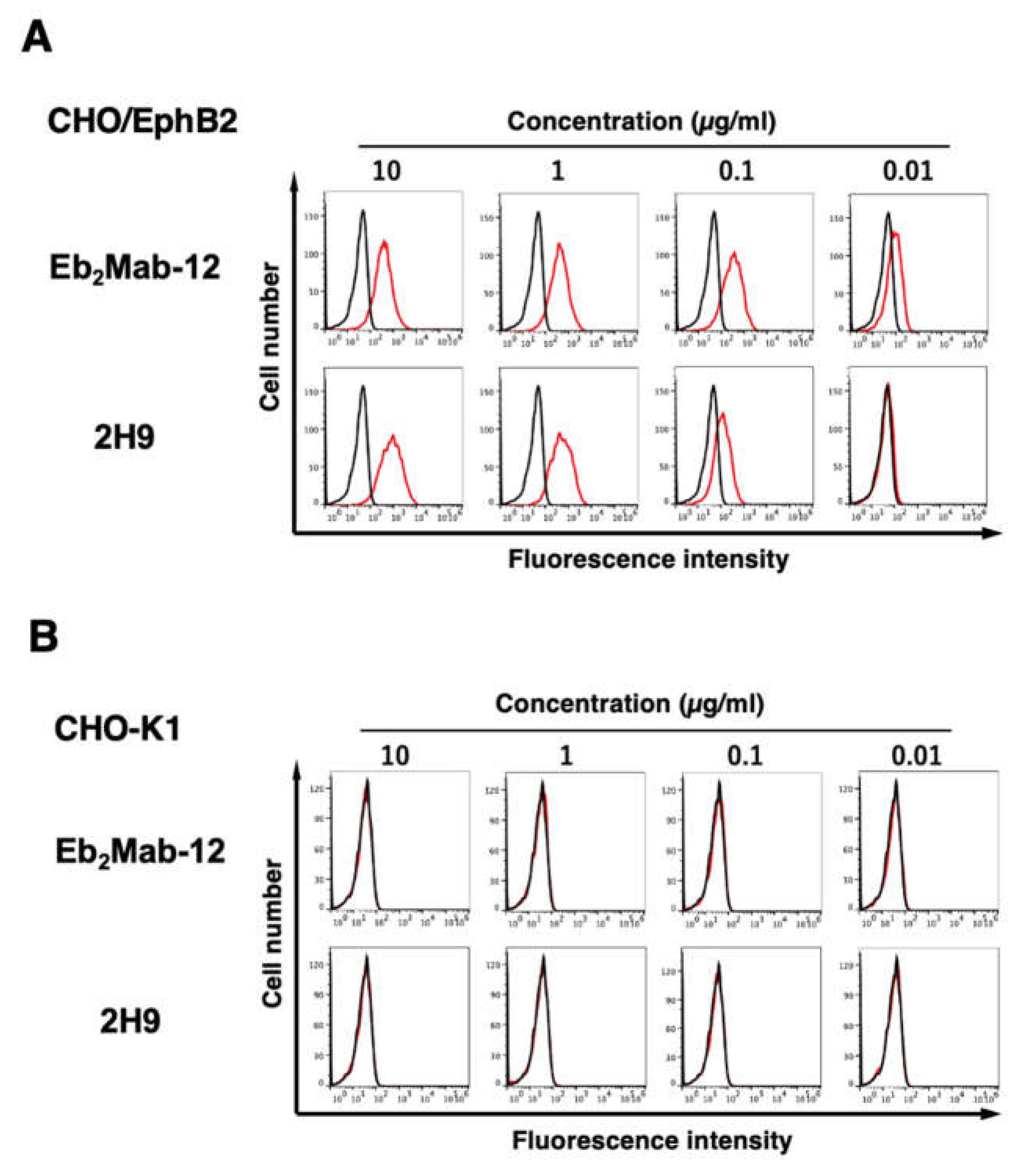

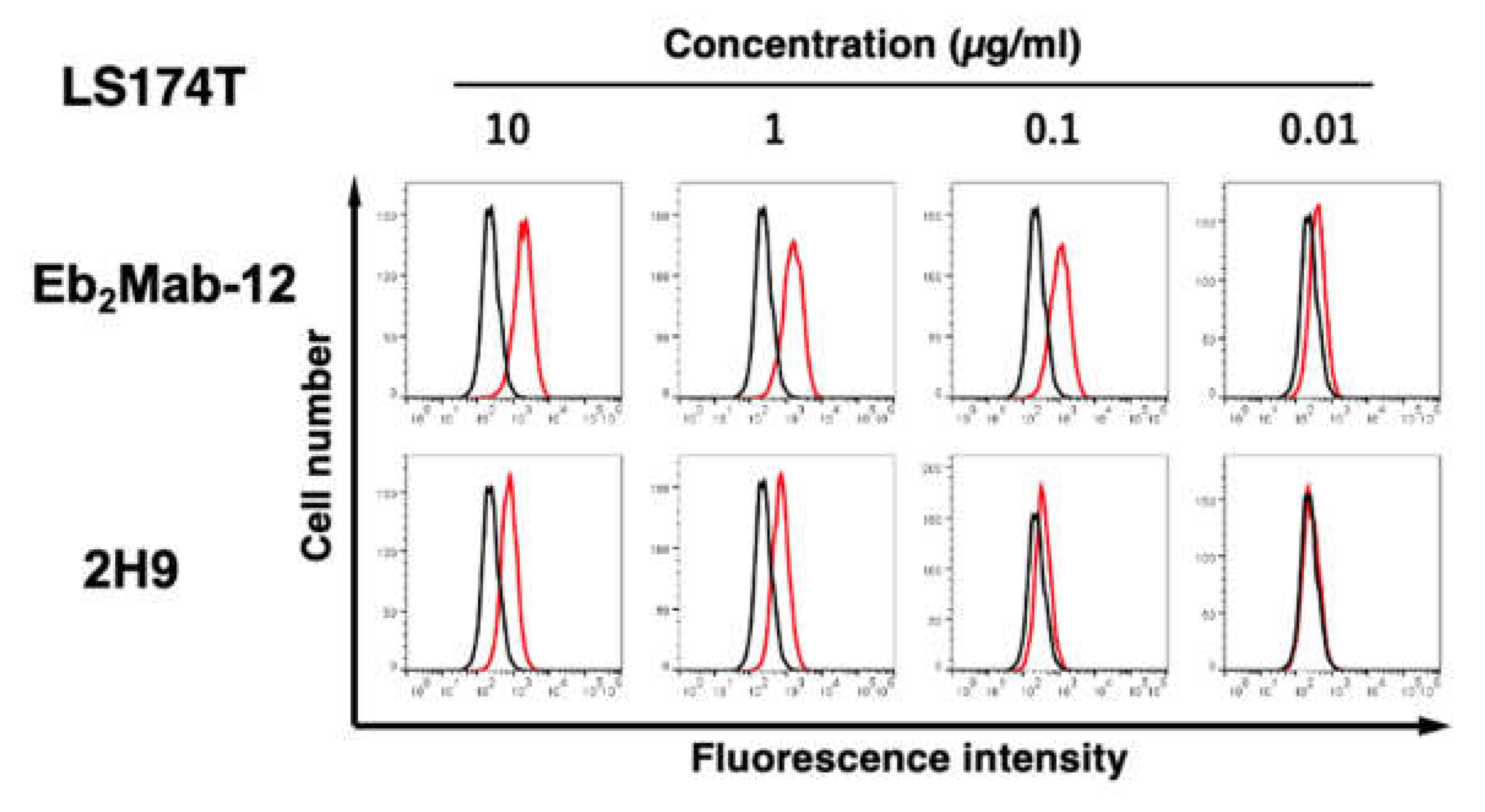

3.2. Flow cytometric analysis using anti-EphB2 mAbs

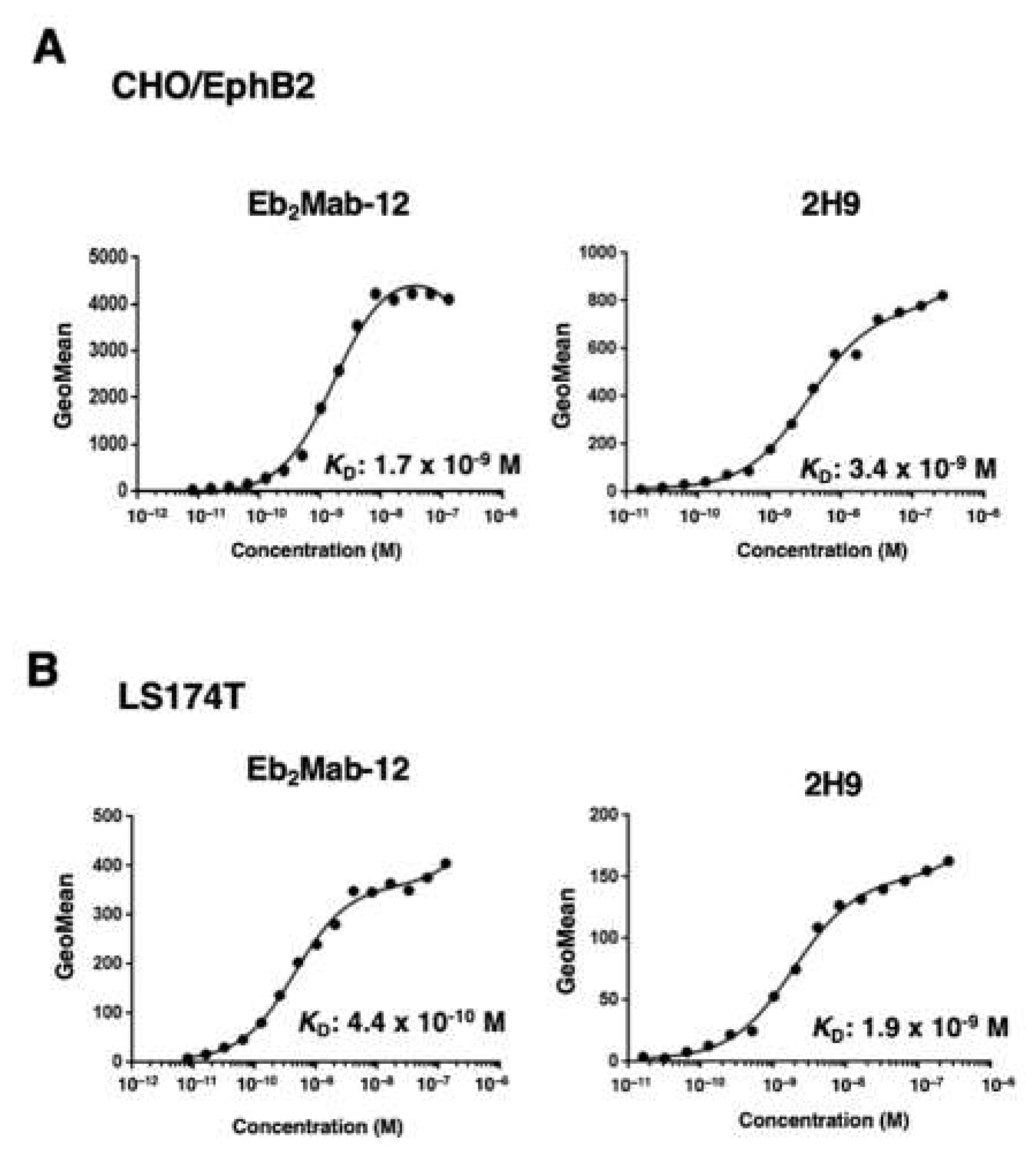

3.3. Determination of the binding affinity of Eb2Mabs and 2H9 using flow cytometry

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhu, Y., S. A. Su, J. Shen, H. Ma, J. Le, Y. Xie, and M. Xiang. "Recent Advances of the Ephrin and Eph Family in Cardiovascular Development and Pathologies." iScience 27, no. 8 (2024): 110556. [CrossRef]

- Pasquale, E. B. "Eph Receptor Signaling Complexes in the Plasma Membrane." Trends Biochem Sci 49, no. 12 (2024): 1079-96. [CrossRef]

- "Eph Receptors and Ephrins in Cancer Progression." Nat Rev Cancer 24, no. 1 (2024): 5-27.

- Anderton, M., E. van der Meulen, M. J. Blumenthal, and G. Schäfer. "The Role of the Eph Receptor Family in Tumorigenesis." Cancers (Basel) 13, no. 2 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Liang, L. Y., O. Patel, P. W. Janes, J. M. Murphy, and I. S. Lucet. "Eph Receptor Signalling: From Catalytic to Non-Catalytic Functions." Oncogene 38, no. 39 (2019): 6567-84. [CrossRef]

- Pasquale, E. B. "Eph Receptors and Ephrins in Cancer: Bidirectional Signalling and Beyond." Nat Rev Cancer 10, no. 3 (2010): 165-80. [CrossRef]

- "Eph Receptor Signalling Casts a Wide Net on Cell Behaviour." Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6, no. 6 (2005): 462-75. [CrossRef]

- Arora, S., A. M. Scott, and P. W. Janes. "Eph Receptors in Cancer." Biomedicines 11, no. 2 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Lau, A., N. Le, C. Nguyen, and R. P. Kandpal. "Signals Transduced by Eph Receptors and Ephrin Ligands Converge on Map Kinase and Akt Pathways in Human Cancers." Cell Signal 104 (2023): 110579. [CrossRef]

- Toracchio, L., M. Carrabotta, C. Mancarella, A. Morrione, and K. Scotlandi. "Epha2 in Cancer: Molecular Complexity and Therapeutic Opportunities." Int J Mol Sci 25, no. 22 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Scarini, J. F., M. W. A. Gonçalves, R. A. de Lima-Souza, L. Lavareze, T. de Carvalho Kimura, C. C. Yang, A. Altemani, F. V. Mariano, H. P. Soares, G. C. Fillmore, and E. S. A. Egal. "Potential Role of the Eph/Ephrin System in Colorectal Cancer: Emerging Druggable Molecular Targets." Front Oncol 14 (2024): 1275330. [CrossRef]

- Guo, X., Y. Yang, J. Tang, and J. Xiang. "Ephs in Cancer Progression: Complexity and Context-Dependent Nature in Signaling, Angiogenesis and Immunity." Cell Commun Signal 22, no. 1 (2024): 299.

- Stergiou, I. E., S. P. Papadakos, A. Karyda, O. E. Tsitsilonis, M. A. Dimopoulos, and S. Theocharis. "Eph/Ephrin Signaling in Normal Hematopoiesis and Hematologic Malignancies: Deciphering Their Intricate Role and Unraveling Possible New Therapeutic Targets." Cancers (Basel) 15, no. 15 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Papadakos, S. P., N. Dedes, N. Gkolemi, N. Machairas, and S. Theocharis. "The Eph/Ephrin System in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma (Pdac): From Pathogenesis to Treatment." Int J Mol Sci 24, no. 3 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Psilopatis, I., E. Souferi-Chronopoulou, K. Vrettou, C. Troungos, and S. Theocharis. "Eph/Ephrin-Targeting Treatment in Breast Cancer: A New Chapter in Breast Cancer Therapy." Int J Mol Sci 23, no. 23 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Psilopatis, I., A. Pergaris, K. Vrettou, G. Tsourouflis, and S. Theocharis. "The Eph/Ephrin System in Gynecological Cancers: Focusing on the Roots of Carcinogenesis for Better Patient Management." Int J Mol Sci 23, no. 6 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Psilopatis, I., I. Karniadakis, K. S. Danos, K. Vrettou, K. Michaelidou, K. Mavridis, S. Agelaki, and S. Theocharis. "May Eph/Ephrin Targeting Revolutionize Lung Cancer Treatment?" Int J Mol Sci 24, no. 1 (2022).

- Papadakos, S. P., L. Petrogiannopoulos, A. Pergaris, and S. Theocharis. "The Eph/Ephrin System in Colorectal Cancer." Int J Mol Sci 23, no. 5 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Liu, W., C. Yu, J. Li, and J. Fang. "The Roles of Ephb2 in Cancer." Front Cell Dev Biol 10 (2022): 788587.

- Chen, X., D. Yu, H. Zhou, X. Zhang, Y. Hu, R. Zhang, X. Gao, M. Lin, T. Guo, and K. Zhang. "The Role of Epha7 in Different Tumors." Clin Transl Oncol 24, no. 7 (2022): 1274-89. [CrossRef]

- Goparaju, C., J. S. Donington, T. Hsu, R. Harrington, N. Hirsch, and H. I. Pass. "Overexpression of Eph Receptor B2 in Malignant Mesothelioma Correlates with Oncogenic Behavior." J Thorac Oncol 8, no. 9 (2013): 1203-11. [CrossRef]

- Cha, J. H., L. C. Chan, Y. N. Wang, Y. Y. Chu, C. H. Wang, H. H. Lee, W. Xia, W. C. Shyu, S. P. Liu, J. Yao, C. W. Chang, F. R. Cheng, J. Liu, S. O. Lim, J. L. Hsu, W. H. Yang, G. N. Hortobagyi, C. Lin, L. Yang, D. Yu, L. B. Jeng, and M. C. Hung. "Ephrin Receptor A10 Monoclonal Antibodies and the Derived Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells Exert an Antitumor Response in Mouse Models of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer." J Biol Chem 298, no. 4 (2022): 101817. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, T., Y. Xiao, W. Wang, Y. Y. Tang, Z. Xiao, and M. Su. "Targeting Epha2 in Cancer." J Hematol Oncol 13, no. 1 (2020): 114. [CrossRef]

- Tang, F. H. F., D. Davis, W. Arap, R. Pasqualini, and F. I. Staquicini. "Eph Receptors as Cancer Targets for Antibody-Based Therapy." Adv Cancer Res 147 (2020): 303-17. [CrossRef]

- London, M., and E. Gallo. "Critical Role of Epha3 in Cancer and Current State of Epha3 Drug Therapeutics." Mol Biol Rep 47, no. 7 (2020): 5523-33.

- Janes, P. W., M. E. Vail, H. K. Gan, and A. M. Scott. "Antibody Targeting of Eph Receptors in Cancer." Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 13, no. 5 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Buckens, O. J., B. El Hassouni, E. Giovannetti, and G. J. Peters. "The Role of Eph Receptors in Cancer and How to Target Them: Novel Approaches in Cancer Treatment." Expert Opin Investig Drugs 29, no. 6 (2020): 567-82. [CrossRef]

- Saha, N., D. Robev, E. O. Mason, J. P. Himanen, and D. B. Nikolov. "Therapeutic Potential of Targeting the Eph/Ephrin Signaling Complex." Int J Biochem Cell Biol 105 (2018): 123-33. [CrossRef]

- Taki, S., H. Kamada, M. Inoue, K. Nagano, Y. Mukai, K. Higashisaka, Y. Yoshioka, Y. Tsutsumi, and S. Tsunoda. "A Novel Bispecific Antibody against Human Cd3 and Ephrin Receptor A10 for Breast Cancer Therapy." PLoS One 10, no. 12 (2015): e0144712. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F., B. Wang, H. Wang, L. Hu, J. Zhang, T. Yu, X. Xu, W. Tian, C. Zhao, H. Zhu, and N. Liu. "Circmelk Promotes Glioblastoma Multiforme Cell Tumorigenesis through the Mir-593/Ephb2 Axis." Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 25 (2021): 25-36.

- Lam, S., E. Wiercinska, A. F. Teunisse, K. Lodder, P. ten Dijke, and A. G. Jochemsen. "Wild-Type P53 Inhibits Pro-Invasive Properties of Tgf-Β3 in Breast Cancer, in Part through Regulation of Ephb2, a New Tgf-Β Target Gene." Breast Cancer Res Treat 148, no. 1 (2014): 7-18.

- Leung, H. W., C. O. N. Leung, E. Y. Lau, K. P. S. Chung, E. H. Mok, M. M. L. Lei, R. W. H. Leung, M. Tong, V. W. Keng, C. Ma, Q. Zhao, I. O. L. Ng, S. Ma, and T. K. Lee. "Ephb2 Activates Β-Catenin to Enhance Cancer Stem Cell Properties and Drive Sorafenib Resistance in Hepatocellular Carcinoma." Cancer Res 81, no. 12 (2021): 3229-40.

- Nakada, M., J. A. Niska, H. Miyamori, W. S. McDonough, J. Wu, H. Sato, and M. E. Berens. "The Phosphorylation of Ephb2 Receptor Regulates Migration and Invasion of Human Glioma Cells." Cancer Res 64, no. 9 (2004): 3179-85. [CrossRef]

- Nakada, M., J. A. Niska, N. L. Tran, W. S. McDonough, and M. E. Berens. "Ephb2/R-Ras Signaling Regulates Glioma Cell Adhesion, Growth, and Invasion." Am J Pathol 167, no. 2 (2005): 565-76.

- Xi, H. Q., X. S. Wu, B. Wei, and L. Chen. "Eph Receptors and Ephrins as Targets for Cancer Therapy." J Cell Mol Med 16, no. 12 (2012): 2894-909. [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, J., M. Genander, M. M. Halford, C. Annerén, M. Sondell, M. J. Chumley, R. E. Silvany, M. Henkemeyer, and J. Frisén. "Ephb Receptors Coordinate Migration and Proliferation in the Intestinal Stem Cell Niche." Cell 125, no. 6 (2006): 1151-63. [CrossRef]

- Batlle, E., J. T. Henderson, H. Beghtel, M. M. van den Born, E. Sancho, G. Huls, J. Meeldijk, J. Robertson, M. van de Wetering, T. Pawson, and H. Clevers. "Beta-Catenin and Tcf Mediate Cell Positioning in the Intestinal Epithelium by Controlling the Expression of Ephb/Ephrinb." Cell 111, no. 2 (2002): 251-63.

- Cortina, C., S. Palomo-Ponce, M. Iglesias, J. L. Fernández-Masip, A. Vivancos, G. Whissell, M. Humà, N. Peiró, L. Gallego, S. Jonkheer, A. Davy, J. Lloreta, E. Sancho, and E. Batlle. "Ephb-Ephrin-B Interactions Suppress Colorectal Cancer Progression by Compartmentalizing Tumor Cells." Nat Genet 39, no. 11 (2007): 1376-83.

- Jubb, A. M., F. Zhong, S. Bheddah, H. I. Grabsch, G. D. Frantz, W. Mueller, V. Kavi, P. Quirke, P. Polakis, and H. Koeppen. "Ephb2 Is a Prognostic Factor in Colorectal Cancer." Clin Cancer Res 11, no. 14 (2005): 5181-7. [CrossRef]

- Takei, J., M. K. Kaneko, T. Ohishi, M. Kawada, H. Harada, and Y. Kato. "A Novel Anti-Egfr Monoclonal Antibody (Emab-17) Exerts Antitumor Activity against Oral Squamous Cell Carcinomas Via Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity and Complement-Dependent Cytotoxicity." Oncol Lett 19, no. 4 (2020): 2809-16. [CrossRef]

- Goto, N., H. Suzuki, T. Tanaka, K. Ishikawa, T. Ouchida, M. K. Kaneko, and Y. Kato. "Emab-300 Detects Mouse Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor-Expressing Cancer Cell Lines in Flow Cytometry." Antibodies (Basel) 12, no. 3 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Kato, Y., T. Ohishi, M. Sano, T. Asano, Y. Sayama, J. Takei, M. Kawada, and M. K. Kaneko. "H(2)Mab-19 Anti-Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 Monoclonal Antibody Therapy Exerts Antitumor Activity in Pancreatic Cancer Xenograft Models." Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 39, no. 3 (2020): 61-65. [CrossRef]

- Ouchida, Tsunenori, Hiroyuki Suzuki, Tomohiro Tanaka, Mika K. Kaneko, and Yukinari Kato. "Development of Highly Sensitive Anti-Mouse Her2 Monoclonal Antibodies for Flow Cytometry." International Journal of Translational Medicine 3, no. 3 (2023): 310-20. [CrossRef]

- Asano, T., T. Ohishi, J. Takei, T. Nakamura, R. Nanamiya, H. Hosono, T. Tanaka, M. Sano, H. Harada, M. Kawada, M. K. Kaneko, and Y. Kato. "Anti-Her3 Monoclonal Antibody Exerts Antitumor Activity in a Mouse Model of Colorectal Adenocarcinoma." Oncol Rep 46, no. 2 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Nanamiya, R., H. Suzuki, M. K. Kaneko, and Y. Kato. "Development of an Anti-Ephb4 Monoclonal Antibody for Multiple Applications against Breast Cancers." Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 42, no. 5 (2023): 166-77.

- Qiu, W., S. Song, W. Chen, J. Zhang, H. Yang, and Y. Chen. "Hypoxia-Induced Ephb2 Promotes Invasive Potential of Glioblastoma." Int J Clin Exp Pathol 12, no. 2 (2019): 539-48.

- Genander, M., M. M. Halford, N. J. Xu, M. Eriksson, Z. Yu, Z. Qiu, A. Martling, G. Greicius, S. Thakar, T. Catchpole, M. J. Chumley, S. Zdunek, C. Wang, T. Holm, S. P. Goff, S. Pettersson, R. G. Pestell, M. Henkemeyer, and J. Frisén. "Dissociation of Ephb2 Signaling Pathways Mediating Progenitor Cell Proliferation and Tumor Suppression." Cell 139, no. 4 (2009): 679-92. [CrossRef]

- Mao, W., E. Luis, S. Ross, J. Silva, C. Tan, C. Crowley, C. Chui, G. Franz, P. Senter, H. Koeppen, and P. Polakis. "Ephb2 as a Therapeutic Antibody Drug Target for the Treatment of Colorectal Cancer." Cancer Res 64, no. 3 (2004): 781-8. [CrossRef]

- Sano, M., M. K. Kaneko, T. Aasano, and Y. Kato. "Epitope Mapping of an Antihuman Egfr Monoclonal Antibody (Emab-134) Using the Remap Method." Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 40, no. 4 (2021): 191-95. [CrossRef]

- Asano, T., M. K. Kaneko, J. Takei, N. Tateyama, and Y. Kato. "Epitope Mapping of the Anti-Cd44 Monoclonal Antibody (C(44)Mab-46) Using the Remap Method." Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 40, no. 4 (2021): 156-61. [CrossRef]

- Okada, Y., H. Suzuki, T. Tanaka, M. K. Kaneko, and Y. Kato. "Epitope Mapping of an Anti-Mouse Cd39 Monoclonal Antibody Using Pa Scanning and Riedl Scanning." Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 43, no. 2 (2024): 44-52. [CrossRef]

- Sharkey, R. M., S. V. Govindan, T. M. Cardillo, J. Donnell, J. Xia, E. A. Rossi, C. H. Chang, and D. M. Goldenberg. "Selective and Concentrated Accretion of Sn-38 with a Ceacam5-Targeting Antibody-Drug Conjugate (Adc), Labetuzumab Govitecan (Immu-130)." Mol Cancer Ther 17, no. 1 (2018): 196-203.

- Li, G., H. Suzuki, T. Ohishi, T. Asano, T. Tanaka, M. Yanaka, T. Nakamura, T. Yoshikawa, M. Kawada, M. K. Kaneko, and Y. Kato. "Antitumor Activities of a Defucosylated Anti-Epcam Monoclonal Antibody in Colorectal Carcinoma Xenograft Models." Int J Mol Med 51, no. 2 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, M. K., H. Suzuki, and Y. Kato. "Establishment of a Novel Cancer-Specific Anti-Her2 Monoclonal Antibody H(2)Mab-250/H(2)Casmab-2 for Breast Cancers." Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 43, no. 2 (2024): 35-43.

- Suzuki, H., T. Ohishi, T. Tanaka, M. K. Kaneko, and Y. Kato. "A Cancer-Specific Monoclonal Antibody against Podocalyxin Exerted Antitumor Activities in Pancreatic Cancer Xenografts." Int J Mol Sci 25, no. 1 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Kato, Y., and M. K. Kaneko. "A Cancer-Specific Monoclonal Antibody Recognizes the Aberrantly Glycosylated Podoplanin." Sci Rep 4 (2014): 5924. [CrossRef]

- Hosking, Martin, Soheila Shirinbak, Kyla Omilusik, Shilpi Chandra, Angela Gentile, Stephanie Kennedy, Lorraine Loter, Samad Ibitokou, Chris Ecker, Nicholas Brookhouser, Lauren Fong, Loraine Campanati, Xu Yuan, Karina Palomares, Yijia Pan, Shohreh Sikaroodi, Mika K Kaneko, Tatsuo Maeda, Daisuke Nakayama, Betsy Rezner, Eigen Peralta, Peter Szabo, Laura Chow, Raedun Clarke, Ramzey Abujarour, Tom Lee, Susumu Yamamoto, Yukinari Kato, and Bahram Valamehr. "268 Development of Ft825/Ono-8250: An Off-the-Shelf Car-T Cell with Preferential Her2 Targeting and Engineered to Enable Multi-Antigen Targeting, Improve Trafficking, and Overcome Immunosuppression." Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer 11, no. Suppl 1 (2023): A307-A07.

| Isotype | Cross-reactivity | KD (× 10−9 M) | |

| Eb2Mab-1 | IgG1, kappa | − | 5.9 |

| Eb2Mab-2 | IgG1, kappa | − | 6.4 |

| Eb2Mab-3 | IgG1, kappa | EphA3, EphB1, EphB3 | 1.1 |

| Eb2Mab-4 | IgG1, kappa | 3.3 | |

| Eb2Mab-7 | IgG1, kappa | 5.2 | |

| Eb2Mab-8 | IgG1, kappa | EphB3 | 9.5 |

| Eb2Mab-10 | IgG1, kappa | EphB3 | 3.4 |

| Eb2Mab-12 | IgG1, kappa | − | 1.7* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).