Submitted:

11 June 2024

Posted:

11 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Regarding the Malaysia geographic and environment, the correlation between weather variables and the load consumption that influences the forecasting process is analyzed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient method where the findings will influence the direction of the next generation research.

- A novel Improved Bacterial Foraging Optimization Algorithm (IBFOA) is proposed to optimize the important parameters of the LSSVM model and enhance the forecasting accuracy of the actual electricity load demand in reflecting the sustainable power market in Malaysia.

- A full support validation accuracy measures are incorporated into the proposed model to evaluate performance of the IBFOA while giving such accurate load profile demand for the power network sustainability in Malaysia.

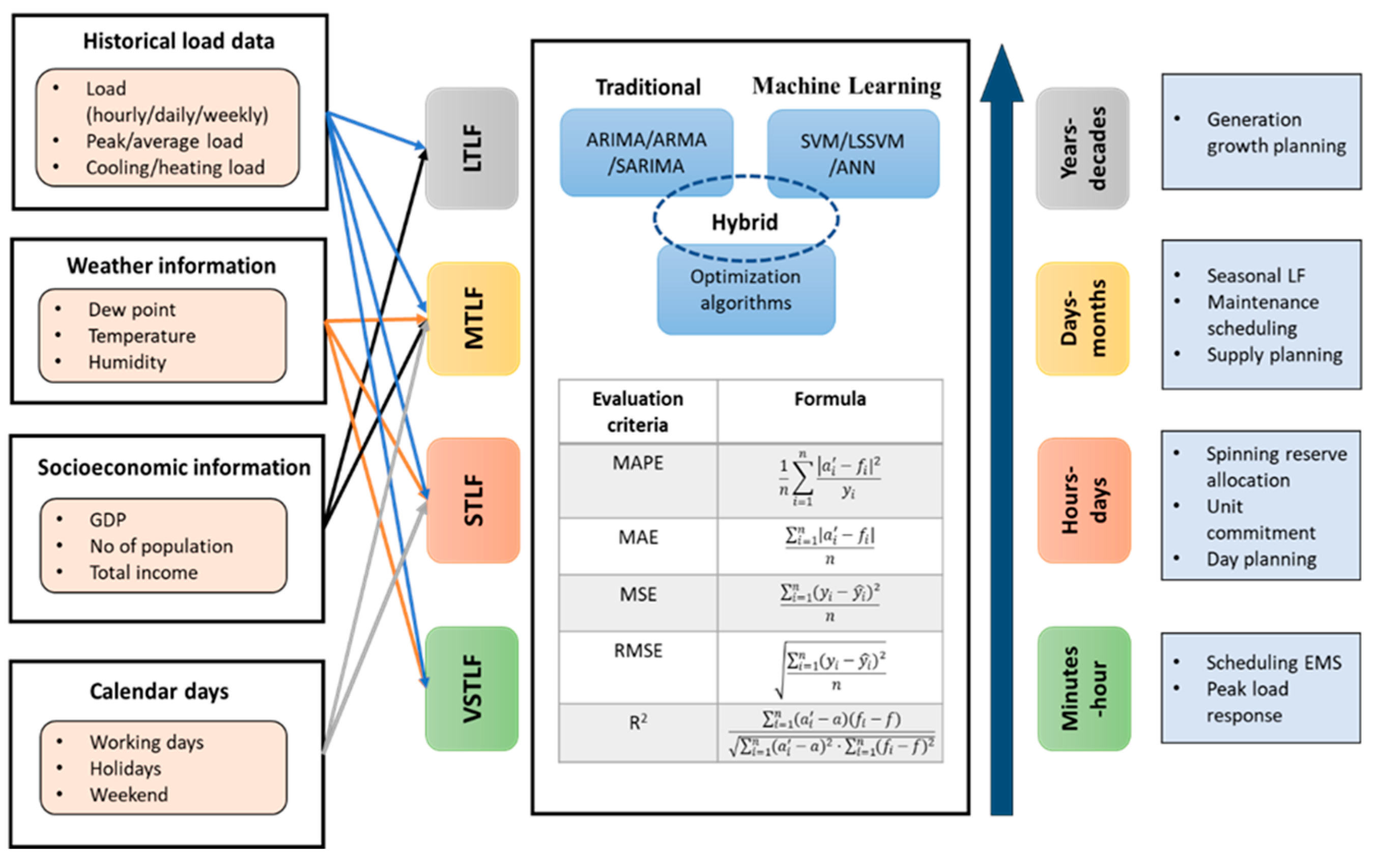

2. Review of Related Work

3. Methodology

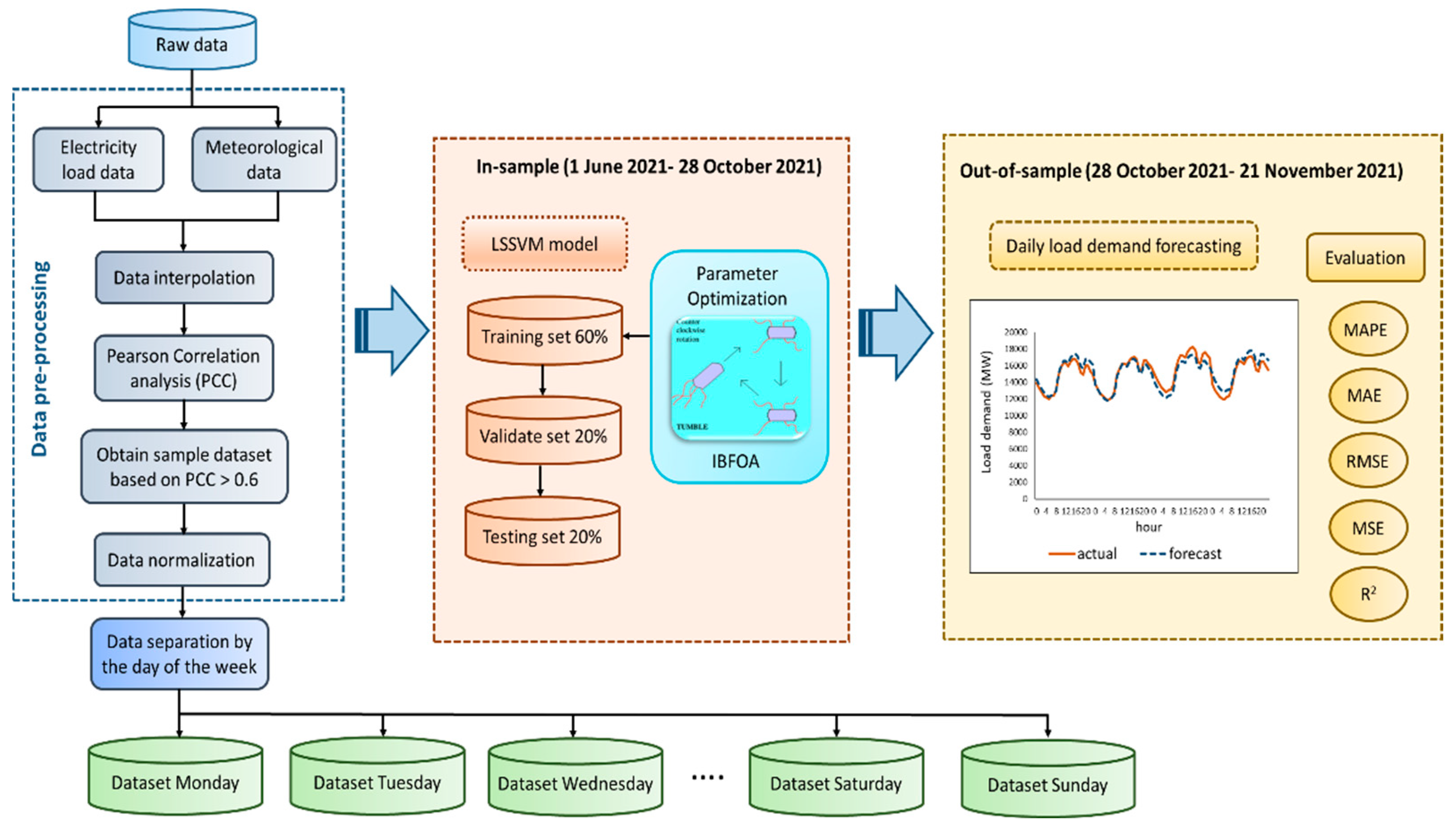

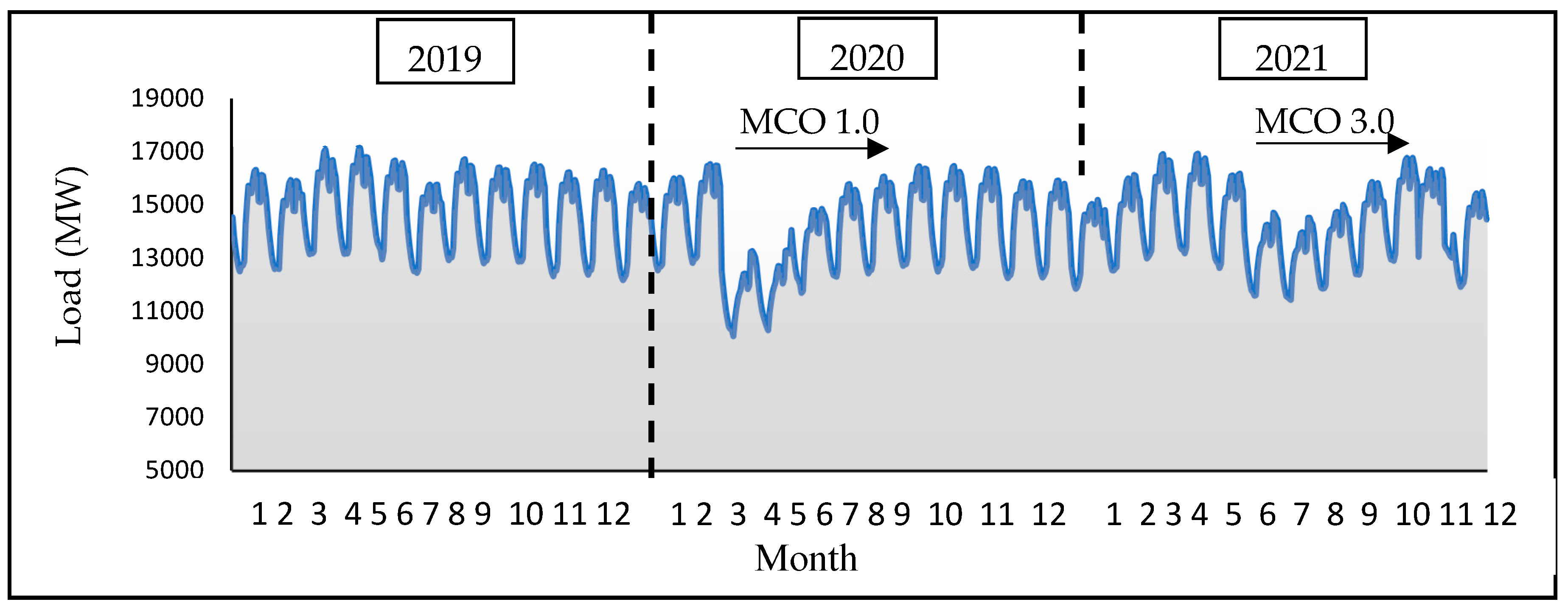

3.1. Data Pre-Processing

3.1.1. Data Interpolation

3.1.2. Pearson Correlation Analysis

3.1.3. Data Division

3.1.4. Data Normalization

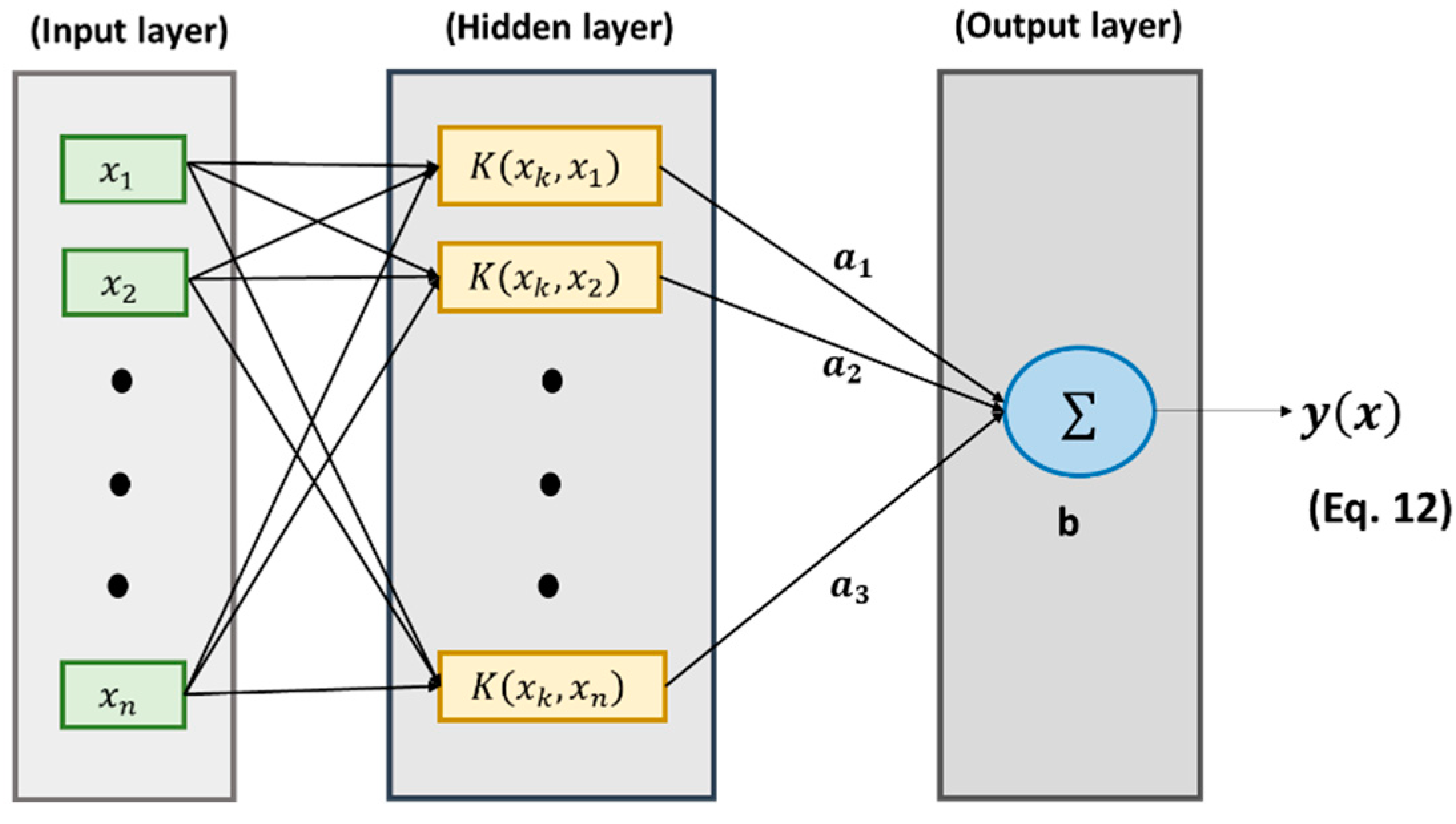

3.2. Least Square Support Vector Machine (LSSVM)

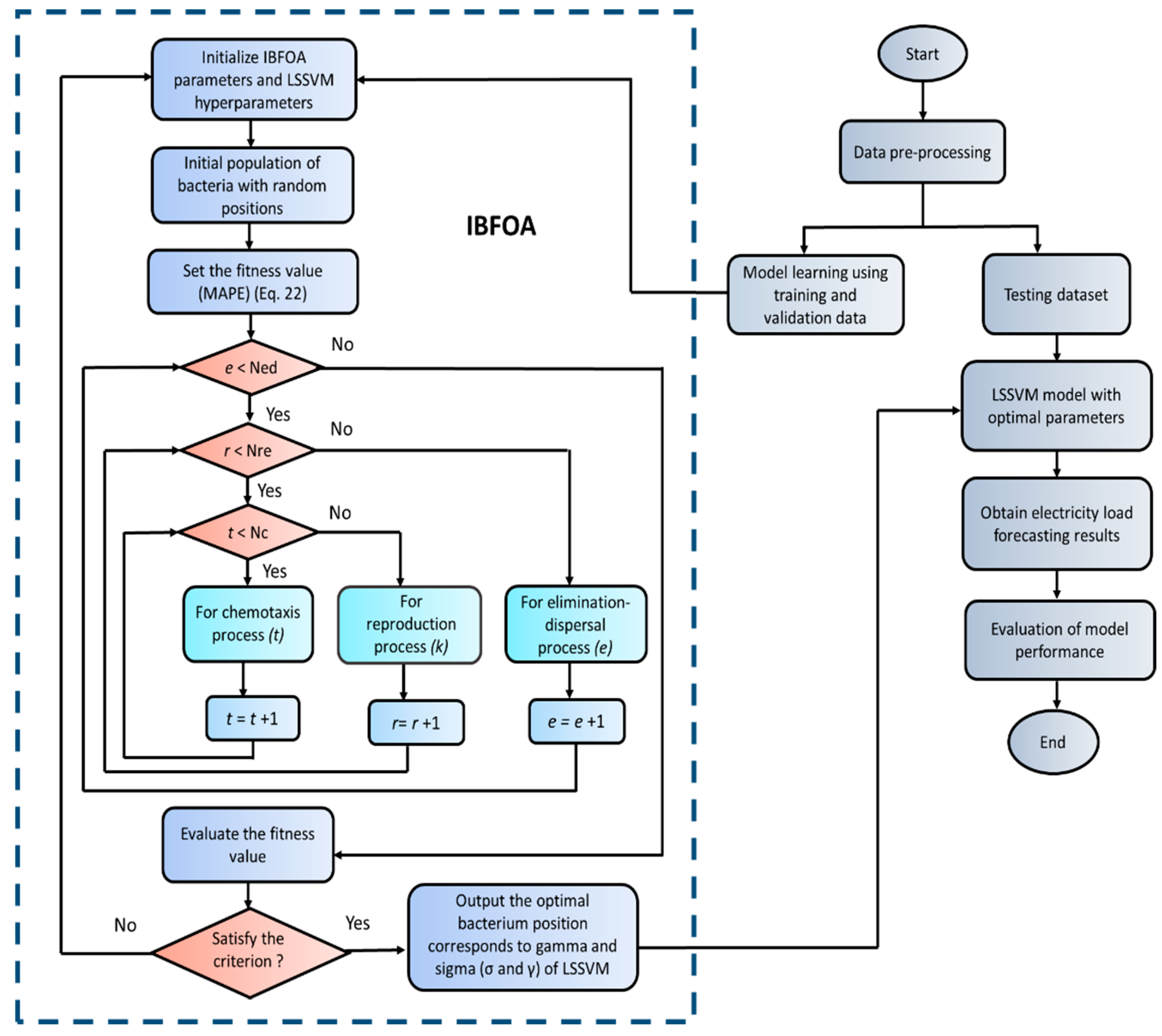

3.3. Bacterial Foraging Optimization Algorithm

- Chemotaxis: It is a process by which bacteria navigate their environment in response to chemical gradients. This behavior allows them to locate favorable conditions, such as nutrient sources. Bacteria achieve chemotaxis through a series of short runs (swims) and tumbles. Flagellar rotation determines their movement: swimming in a defined direction or tumbling to explore new areas. A unit-length random direction vector as described in Equation (15) representing a tumble for the n-th bacterium at the t-th chemotactic step, r-th reproductive step, and e-th elimination dispersal step. This vector describes the direction change after a tumble.

- Swarming: Swarming is a collective behavior in bacteria that promotes their movement towards areas with higher nutrient concentrations. This phenomenon is modeled by introducing an additional cost function term (Jcc) that influences the overall cost function (J) experienced by each bacterium. The swarming cost (Jcc) considers both the local bacterial density and the distance between individual bacteria. The mathematical representation for swarming process is expressed by Equation (17):

- Reproduction: Reproduction step happens after following a predefined number of chemotactic steps (Nc). This step promotes the propagation of “fitter” bacteria within the population. Bacteria with higher health values, typically determined by a fitness function have a greater chance of reproducing. Conversely, bacteria with lower health values will be eliminated. This mechanism ensures a constant population size while favoring individuals with better foraging abilities. The health value of the bacterium obtained as below:

- Elimination-dispersal: Elimination-dispersal simulates the dynamic nature of the bacterial environment, where local events can drastically affect bacterial populations. This process can either eliminate all bacteria in a local region or disperse them to new locations, potentially disrupting chemotaxis progress but also aiding in exploration by placing bacteria near potential food sources.

3.4. Proposed Improved Bacterial Foraging Optimization Algorithm

3.5. Forecasting Process by Hybrid LSSVM-IBFOA

3.6. Evaluation Metrics

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Correlation Analysis

4.2. Case Study

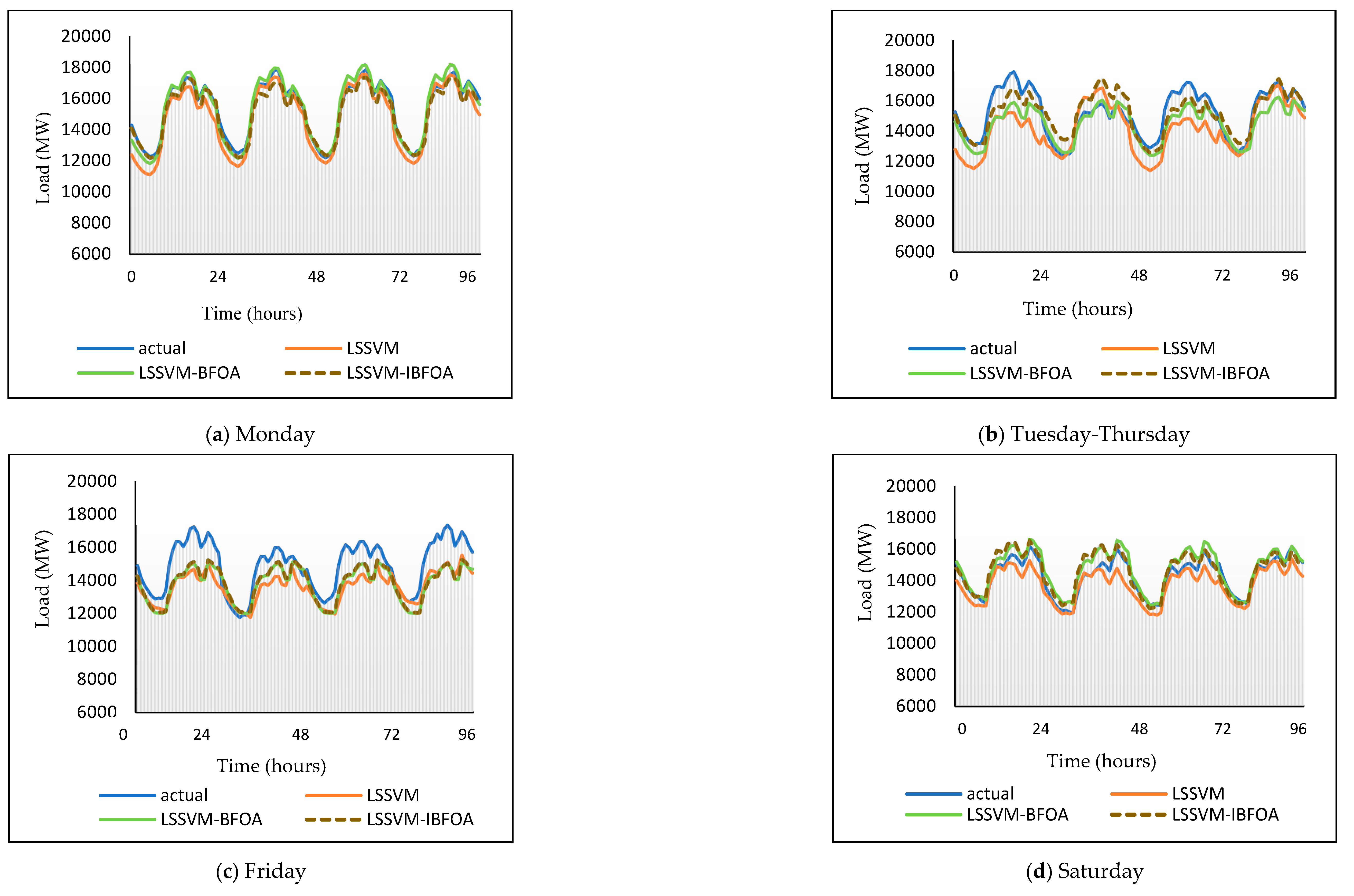

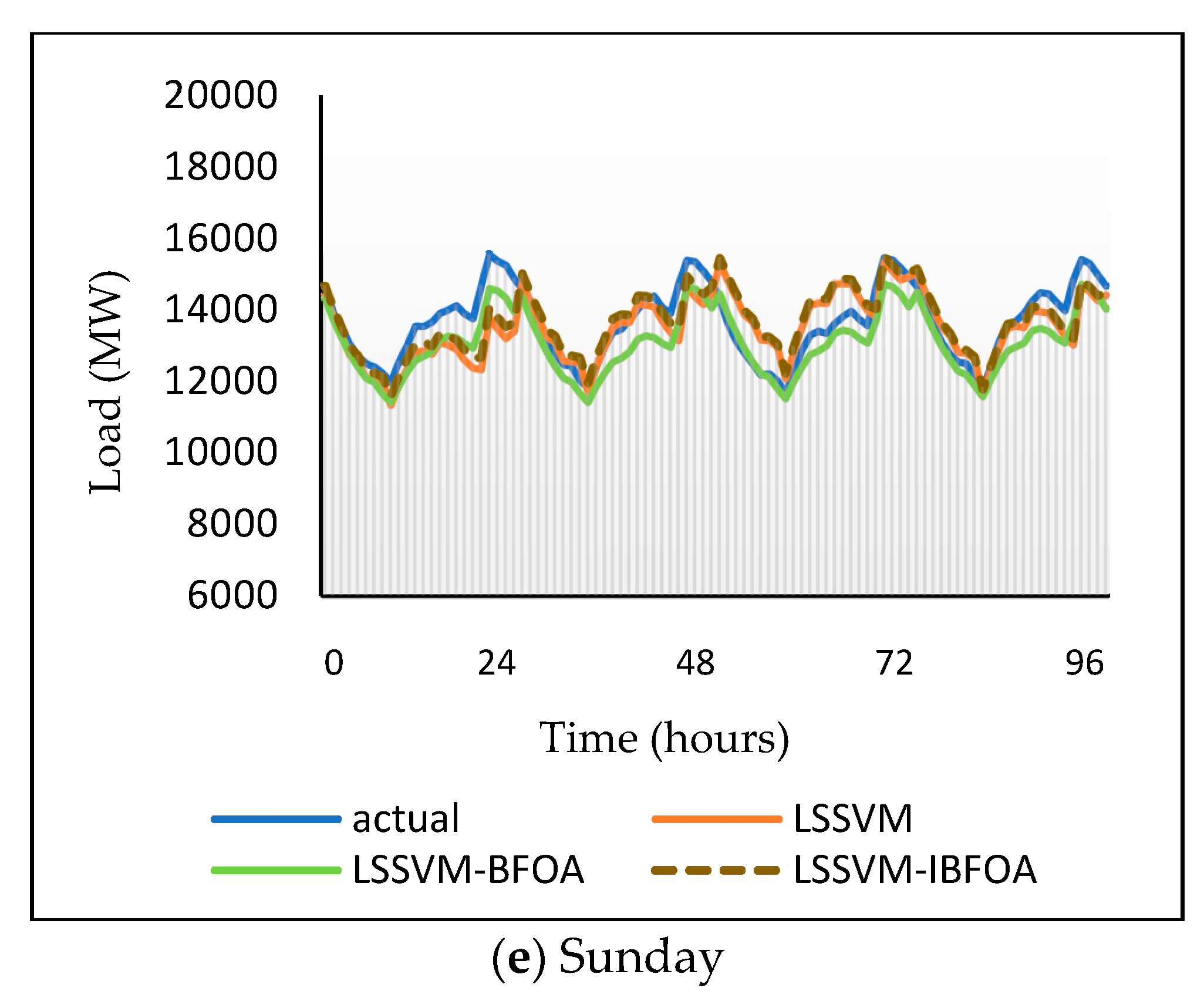

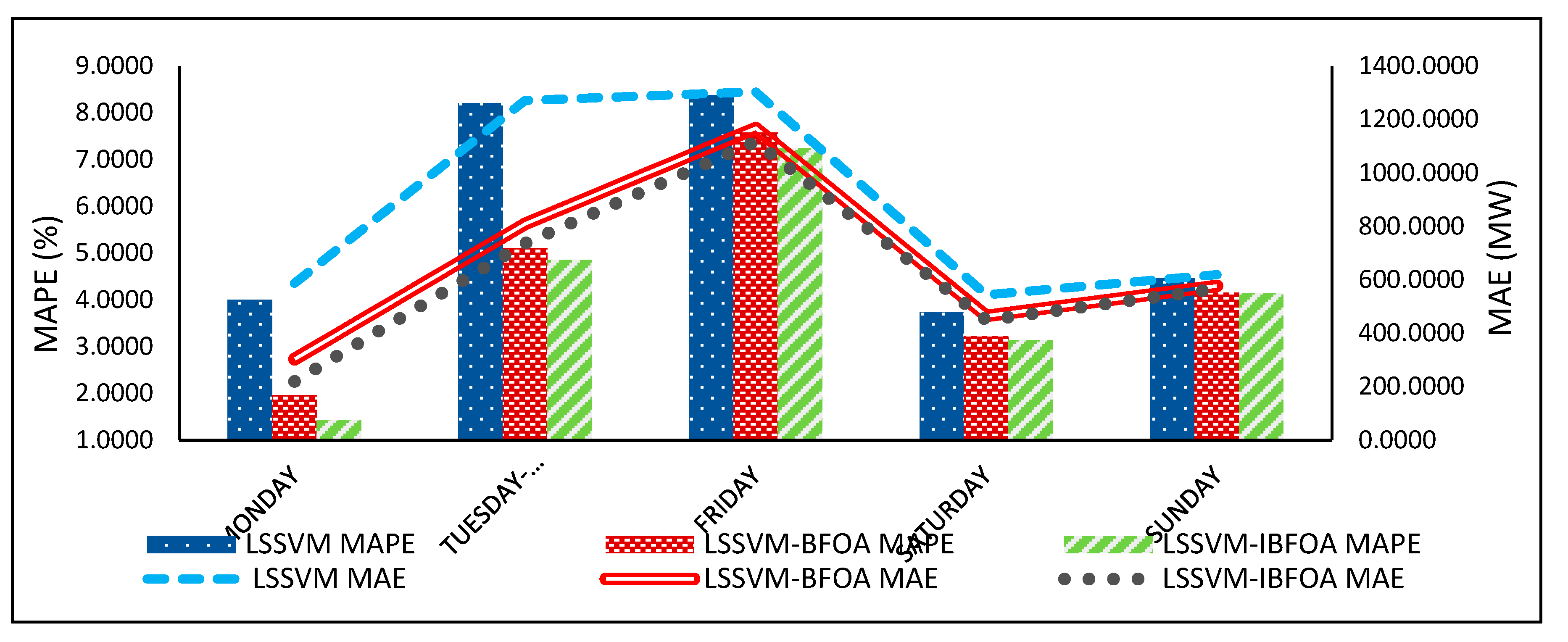

4.3. Load Forecasting Results

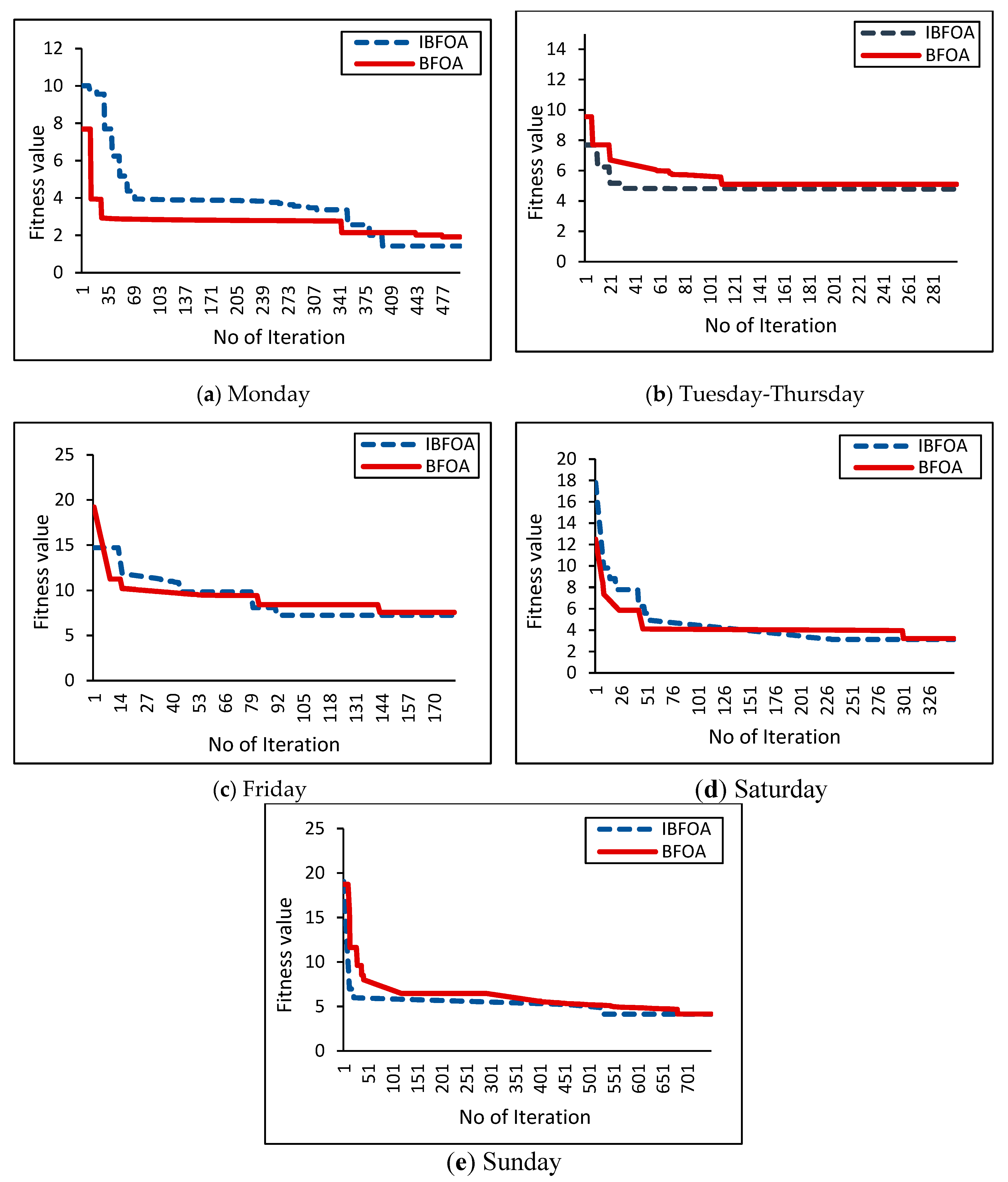

4.4. Algorithm Performance

5. Conclusions

- a)

- Increasing the size of the dataset to one year or more to see the performance of LSSVM in training the data,

- b)

- Application for LSSVM-IBFOA for load forecasting on a smaller load aggregation such as residential or building,

- c)

- Test different combinations of feature/input sets which represent the primary consumption,

- d)

- Hybridizing the LSSVM model with other newly nature-inspired algorithms, data decomposition techniques, and feature selection methods to improve ML forecasting performance.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Z. Zulkifli, “Malaysia Country Report,” 17 th AsiaConstruct Conf., no. 72, pp. 170–190, 2021.

- IRENA, Malaysia energy transition outlook. International Renewable Energy Agency, Abu Dhabi, 2023. [Online]. Available: www.irena.org.

- L. Aswanuwath, W. Pannakkong, J. Buddhakulsomsiri, and J. Karnjana, “An Improved Hybrid Approach for Daily Electricity Peak Demand Forecasting during Disrupted Situations : A Case Study of COVID-19 Impact in Thailand,” Energies, vol. 17, no. 78, 2023.

- F. Abd. Razak, M. Shitan, A. H. Hashim, and I. Z. Abidin, “Load Forecasting Using Time Series Models,” J. Kejuruter., vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 53–62, 2009. [CrossRef]

- L. Hock-Eam and Y. Chee-Yin, “How accurate is TNB’s electricity demand forecast?,” Malaysian J. Math. Sci., vol. 10, pp. 79–90, 2016.

- A. A. Mir, M. Alghassab, K. Ullah, Z. A. Khan, Y. Lu, and M. Imran, “A review of electricity demand forecasting in low and middle income countries: The demand determinants and horizons,” Sustain., vol. 12, no. 15, 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. Koukaras, N. Bezas, P. Gkaidatzis, D. Ioannidis, D. Tzovaras, and C. Tjortjis, “Introducing a novel approach in one-step ahead energy load forecasting,” Sustain. Comput. Informatics Syst., vol. 32, no. August, p. 100616, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Moon, S. Jung, J. Rew, S. Rho, and E. Hwang, “Combination of short-term load forecasting models based on a stacking ensemble approach,” Energy Build., vol. 216, p. 109921, 2020. [CrossRef]

- B. U. Islam, M. Rasheed, and S. F. Ahmed, “Review of Short-Term Load Forecasting for Smart Grids Using Deep Neural Networks and Metaheuristic Methods,” Math. Probl. Eng., vol. 2022, 2022. [CrossRef]

- I. K. Nti, M. Teimeh, O. Nyarko-Boateng, and A. F. Adekoya, “Electricity load forecasting: a systematic review,” J. Electr. Syst. Inf. Technol., vol. 7, no. 1, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Hammad, B. Jereb, B. Rosi, and D. Dragan, “Methods and Models for Electric Load Forecasting: A Comprehensive Review,” Logist. Sustain. Transp., vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 51–76, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Pelekis et al., “A comparative assessment of deep learning models for day-ahead load forecasting: Investigating key accuracy drivers,” Sustain. Energy, Grids Networks, vol. 36, p. 101171, 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Luo, H. Zhang, and J. Wang, “Ensemble power load forecasting based on competitive-inhibition selection strategy and deep learning,” Sustain. Energy Technol. Assessments, vol. 51, no. June 2021, p. 101940, 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Tarmanini, N. Sarma, C. Gezegin, and O. Ozgonenel, “Short term load forecasting based on ARIMA and ANN approaches,” Energy Reports, vol. 9, pp. 550–557, 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. Amjady and F. Keynia, “A new neural network approach to short term load forecasting of electrical power systems,” Energies, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 488–503, 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. Jawad et al., “Machine Learning Based Cost Effective Electricity Load Forecasting Model Using Correlated Meteorological Parameters,” IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 146847–146864, 2020. [CrossRef]

- G.-T. L. F. of the G. E. S. Stamatellos and T. Stamatelos, “Short-Term Load Forecasting of the Greek Electricity System,” Appl. Sci., vol. 13, no. 4, 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Ahmed, D. H. Vu, K. M. Muttaqi, and A. P. Agalgaonkar, “Load forecasting under changing climatic conditions for the city of Sydney, Australia,” Energy, vol. 142, pp. 911–919, 2018. [CrossRef]

- T. Ahmad, H. Chen, J. Shair, and C. Xu, “Deployment of data-mining short and medium-term horizon cooling load forecasting models for building energy optimization and management,” Int. J. Refrig., vol. 98, pp. 399–409, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang et al., “Short-term load forecasting for industrial customers based on TCN-LightGBM,” IEEE Trans. Power Syst., vol. 36, no. 3, pp. 1984–1997, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Yang, W. Li, and X. Yang, “Short-term electricity load forecasting based on feature selection and Least Squares Support Vector Machines,” Knowledge-Based Syst., vol. 163, pp. 159–173, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- I. Antonopoulos et al., “Artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches to energy demand-side response: A systematic review,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 130. Elsevier Ltd., Sep. 01, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Dai, X. Yang, and M. Leng, “Forecasting power load: A hybrid forecasting method with intelligent data processing and optimized artificial intelligence,” Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change, vol. 182, no. July, p. 121858, 2022. [CrossRef]

- I. A. W. A. Razak, W. S. W. Abdullah, and M. F. Sulaima, “Enhanced Short-term System Marginal Price (SMP) Forecast Modelling Using a Hybrid Model Combining Least Squares Support Vector Machines and the Genetic Algorithm in Peninsula Malaysia,” Int. J. Intell. Syst. Appl. Eng., vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 289–298, 2023.

- C. Zhang, J. Zhou, C. Li, W. Fu, and T. Peng, “A compound structure of ELM based on feature selection and parameter optimization using hybrid backtracking search algorithm for wind speed forecasting,” Energy Convers. Manag., vol. 143, pp. 360–376, 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Li et al., “Short-term electrical load forecasting using hybrid model of manta ray foraging optimization and support vector regression,” J. Clean. Prod., vol. 388, p. 135856, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yang, Y. Chen, Y. Wang, C. Li, and L. Li, “Modelling a combined method based on ANFIS and neural network improved by DE algorithm: A case study for short-term electricity demand forecasting,” Applied Soft Computing Journal, vol. 49. Elsevier Ltd., pp. 663–675, Dec. 01, 2016. [CrossRef]

- W. Aribowo, “Optimizing Feed Forward Backpropagation Neural Network Based on Teaching-Learning-Based Optimization Algorithm for Long-Term Electricity Forecasting,” Int. J. Intell. Eng. Syst., vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 11–20, 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Liang, T. Le-Hung, and T. Nguyen-Thoi, “Energy consumption prediction of air-conditioning systems in eco-buildings using hunger games search optimization-based artificial neural network model,” J. Build. Eng., vol. 59, no. August, p. 105087, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Askari and F. Keynia, “Mid-term electricity load forecasting by a new composite method based on optimal learning MLP algorithm,” IET Gener. Transm. Distrib., vol. 14, no. 5, pp. 845–852, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. Bacanin et al., “Multivariate energy forecasting via metaheuristic tuned long-short term memory and gated recurrent unit neural networks,” Inf. Sci. (Ny)., vol. 642, no. January, p. 119122, 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Kottath and P. Singh, “Influencer buddy optimization: Algorithm and its application to electricity load and price forecasting problem,” Energy, vol. 263, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. J. Sadaei, P. C. de Lima e Silva, F. G. Guimarães, and M. H. Lee, “Short-term load forecasting by using a combined method of convolutional neural networks and fuzzy time series,” Energy, vol. 175, pp. 365–377, 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. F. Chen, S. K. Lo, and Q. H. Do, “Forecasting monthly electricity demands: An application of neural networks trained by heuristic algorithms,” Inf., vol. 8, no. 1, 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. Jahani, K. Zare, and L. Mohammad Khanli, “Short-term load forecasting for microgrid energy management system using hybrid SPM-LSTM,” Sustain. Cities Soc., vol. 98, no. July, p. 104775, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Emami Javanmard and S. F. Ghaderi, “Energy demand forecasting in seven sectors by an optimization model based on machine learning algorithms,” Sustain. Cities Soc., vol. 95, no. October 2022, p. 104623, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Barman, N. B. Dev Choudhury, and S. Sutradhar, “A regional hybrid GOA-SVM model based on similar day approach for short-term load forecasting in Assam, India,” Energy, vol. 145, pp. 710–720, 2018. [CrossRef]

- W. Guo, L. Che, M. Shahidehpour, and X. Wan, “Machine-Learning based methods in short-term load forecasting,” Electr. J., vol. 34, no. 1, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z. Wang, X. Zhou, J. Tian, and T. Huang, “Hierarchical parameter optimization based support vector regression for power load forecasting,” Sustain. Cities Soc., vol. 71, no. April, p. 102937, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Li, Y. Lei, and S. Yang, “Mid-long term load forecasting model based on support vector machine optimized by improved sparrow search algorithm,” Energy Reports, vol. 8, pp. 491–497, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Yang, S. Yang, S. Li, R. Zhang, F. Liu, and L. Jiao, “Coupled compressed sensing inspired sparse spatial-spectral LSSVM for hyperspectral image classification,” Knowledge-Based Syst., vol. 79, pp. 80–89, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Q. Ge et al., “Industrial Power Load Forecasting Method Based on Reinforcement Learning and PSO-LSSVM,” IEEE Trans. Cybern., vol. 52, no. 2, pp. 1112–1124, 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Wang, X. Wang, Z. Wang, C. Ma, and Z. Song, “A VMD-CISSA-LSSVM Based Electricity Load Forecasting Model,” Mathematics, vol. 10, no. 1, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Zhang, N. Zhang, Z. Zhang, and Y. Chen, “Electric Power Load Forecasting Method Based on a Support Vector Machine Optimized by the Improved Seagull Optimization Algorithm,” Energies, vol. 15, no. 23, 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. Khan, K. Redae, E. Gidey, O. P. Mahela, I. B. M. Taha, and M. G. Hussien, “Optimal integration of DSTATCOM using improved bacterial search algorithm for distribution network optimization,” Alexandria Eng. J., vol. 61, no. 7, pp. 5539–5555, 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Awad and A. Hafez, “Optimal operation of under-frequency load shedding relays by hybrid optimization of particle swarm and bacterial foraging algorithms,” Alexandria Eng. J., vol. 61, no. 1, pp. 763–774, 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. M. V. Nguyen, T. T. Phung, T. N. Le, N. A. Nguyen, Q. T. Nguyen, and P. N. Nguyen, “Using an improved Neural Network with Bacterial Foraging Optimization algorithm for Load Shedding,” Proc. 2023 Int. Conf. Syst. Sci. Eng. ICSSE 2023, pp. 281–286, 2023. [CrossRef]

- W. S. Tounsi Fokui, M. J. Saulo, and L. Ngoo, “Optimal Placement of Electric Vehicle Charging Stations in a Distribution Network with Randomly Distributed Rooftop Photovoltaic Systems,” IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 132397–132411, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Panwar, G. Sharma, I. Nasiruddin, and R. C. Bansal, “Frequency stabilization of hydro–hydro power system using hybrid bacteria foraging PSO with UPFC and HAE,” Electr. Power Syst. Res., vol. 161, pp. 74–85, 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. Kumar, S. Diwania, R. Singh, H. Ashfaq, P. Khetrapal, and S. Singh, “An intelligent Hybrid Wind–PV farm as a static compensator for overall stability and control of multimachine power system,” ISA Trans., vol. 123, pp. 286–302, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Zadehbagheri, T. Sutikno, M. J. Kiani, and M. Yousefi, “Designing a power system stabilizer using a hybrid algorithm by genetics and bacteria for the multi-machine power system,” Bull. Electr. Eng. Informatics, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 1318–1331, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, Y. Lv, and Y. Zhou, “Research on Economic Optimal Dispatching of Microgrid Based on an Improved Bacteria Foraging Optimization,” Biomimetics, vol. 8, no. 2, p. 150, 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. I. de A. C. Carlos Henrique Valério de Moraes, Jonas Lopes de Vilas Boas, Germano Lambert-Torres, Gilberto Capistrano Cunha de Andrade, “Intelligent Power Distribution Restoration Based on a Multi-Objective Bacterial Foraging Optimization Algorithm,” Energies, vol. 15(4), p. 1445, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Han, H. Xiong, and D. Wei, “Short-term load forecasting of BP network based on bacterial foraging optimization,” IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng., vol. 569, no. 5, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhou, G. Wu, and X. Zhang, “Short-term Load Forecasting Model Based on IBFO-BILSTM,” IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci., vol. 440, no. 3, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, L. Wu, and S. Wang, “Bacterial foraging optimization based neural network for short-term load forecasting,” J. Comput. Inf. Syst., vol. 6, no. 7, pp. 2099–2105, 2010.

- Y. Jiang et al., “Medium-long term load forecasting method considering industry correlation for power management,” Energy Reports, vol. 7, pp. 1231–1238, 2021. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhi, S. Yuexin, M. Jin, Z. Lujie, and D. Zijian, “Research on the Pearson correlation coefficient evaluation method of analog signal in the process of unit peak load regulation,” ICEMI 2017 - Proc. IEEE 13th Int. Conf. Electron. Meas. Instruments, vol. 2018-Janua, pp. 522–527, 2017. [CrossRef]

- K. Gao, X. Xu, and S. Jiao, “Prediction and visualization analysis of drilling energy consumption based on mechanism and data hybrid drive,” Energy, vol. 261, no. PA, p. 125227, 2022. [CrossRef]

- X. Yuan, C. Chen, Y. Yuan, Y. Huang, and Q. Tan, “Short-term wind power prediction based on LSSVM-GSA model,” Energy Convers. Manag., vol. 101, pp. 393–401, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang and Y. Lv, “Research on electrical load distribution using an improved bacterial foraging algorithm,” Front. Energy Res., vol. 11, no. February, pp. 1–12, 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Y. Lee et al., “Hybrid algorithm based on simulated annealing and bacterial foraging optimization for mining imbalanced data,” Sensors Mater., vol. 33, no. 42, pp. 1297–1312, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Sharma, “Adaptive bacterial foraging optimization based task scheduling in cloud computing,” J. Green Eng., vol. 10, no. 11, pp. 10189–10202, 2020.

- S. Mohammad et al., “Sine based Bacterial Foraging Algorithm for a Dynamic Modelling of a Twin Rotor System,” Int. Conf. Control. Autom. Syst., vol. 2019-Octob, no. Iccas 2019, pp. 131–136, 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. Ahmad, Y. Ghadi, M. Adnan, and M. Ali, “Load Forecasting Techniques for Power System: Research Challenges and Survey,” IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 71054–71090, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Hong and S. Fan, “Probabilistic electric load forecasting: A tutorial review,” Int. J. Forecast., vol. 32, no. 3, pp. 914–938, 2016. [CrossRef]

- E. Vivas, H. Allende-Cid, and R. Salas, “A systematic review of statistical and machine learning methods for electrical power forecasting with reported mape score,” Entropy, vol. 22, no. 12, pp. 1–24, 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Sekhar and R. Dahiya, “Robust framework based on hybrid deep learning approach for short term load forecasting of building electricity demand,” Energy, vol. 268, no. September 2022, p. 126660, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Moradzadeh, S. Zakeri, M. Shoaran, B. Mohammadi-Ivatloo, and F. Mohammadi, “Short-term load forecasting of microgrid via hybrid support vector regression and long short-term memory algorithms,” Sustain., vol. 12, no. 17, 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. F. Fan, L. Z. Zhang, M. Yu, W. C. Hong, and S. Q. Dong, “Applications of random forest in multivariable response surface for short-term load forecasting,” Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst., vol. 139, no. May 2021, p. 108073, 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Tsalikidis, A. Mystakidis, C. Tjortjis, P. Koukaras, and D. Ioannidis, “Energy load forecasting: one-step ahead hybrid model utilizing ensembling,” Computing, no. 0123456789, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Groß, A. Lenders, F. Schwenker, D. A. Braun, and D. Fischer, “Comparison of short-term electrical load forecasting methods for different building types,” Energy Informatics, vol. 4, no. Suppl 3, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Kök, E. Yükseltan, M. Hekimoğlu, E. A. Aktunc, A. Yücekaya, and A. Bilge, “Forecasting Hourly Electricity Demand Under COVID-19 Restrictions,” Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 73–85, 2022. [CrossRef]

| Condition | Description |

|---|---|

| = +1 | linear and perfect positive correlation |

| < 1.0 | very strong linear correlation |

| < 0.8 | strong linear correlation |

| < 0.6 | moderate linear correlation |

| < 0.4 | weak linear correlation |

| = 0 | no correlation exists between the two variables |

| = -1 | linear and perfect negative correlation |

| Dataset | Period (Year 2021) | Total days |

|---|---|---|

| Training set | week 1 of June – week 4 of August | 192 days |

| Validation set | week 1 of September – week 4 of September | 64 days |

| Testing set | week 1 of October – week 4 of October | 64 days |

| Number of Steps | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Collecting the historical power load data for the analysis and stored in a MATLAB file format (.mat). The load function in MATLAB is then employed to import this data into the workspace |

| Step 2 | The power load forecasting dataset is divided into training data, validation data and testing data according to the ratio 60:20:20, and the data is normalized. |

| Step 3 | Parameters setting: p, n, S, Nc, Ns, Nre, Ned, Ped Where p is the number of parameters to be optimized, S is the number of bacteria, Ns is the swimming length, Nc is the maximum number of iterations in chemotaxis, Nre is the maximum number of reproduction, Ned is the maximum number of elimination dispersal, Ped is the probability of elimination-dispersal |

| Step 4 | Generate the initial population of bacteria with random positions |

| Step 4.1 | Create an initial population of bacteria with random positions where each bacterium’s positions encode the LSSVM parameters. |

| Step 5 | Set the fitness function |

| Step 5.1 | For each bacterium, train an LSSVM model with the corresponding parameters on historical load data. Evaluate the fitness of each bacterium based on the Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) value: Fitness = MAPE = (23) Where is the actual value of data, is the forecasting value obtained, , and n is the total number of sample sets. |

| Step 6 | Elimination-Dispersal: e= e+1 |

| Step 7 | Reproduction loop: r= r+1 |

| Step 8 | Chemotaxis loop: t=t+1 |

| Step 8.1 | Update the positions of bacteria based on BFOA’s chemotaxis mechanism (Equation (20)) |

| Step 9 | Go to step 8 if t < Nc |

| Step 10 | Perform reproduction |

| Step 10.1 | Select bacteria for reproduction based on their fitness value |

| Step 10.2 | Go to step 7 if r < Nre |

| Step 11 | Perform elimination-dispersal |

| Step 11.1 | Eliminate and disperse each bacterium with probability of Ped. Go to step 6 if e < Ned |

| Step 12 | Evaluate fitness and selection |

| Step 12.1 | Train LSSVM models using the updated positions of bacteria. Evaluate the fitness of the updated bacteria by using Equation (23) |

| Step 13 | Use the LSSVM-IBFOA to forecast the test data and select MAPE as the objective function for forecasting (23) |

| Step 14 | Inverse normalize the forecasting results |

| Step 15 | Output the accuracy measures for evaluation |

| MAPE (%) | Forecasting Capability |

|---|---|

| <10 | Highly accurate forecasting |

| 10-20 | Good forecasting |

| 20-50 | Reasonable forecasting |

| >50 | Inaccurate forecasting |

| Measures | Criteria | Description | Equation | No of equation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAPE | Mean absolute percentage error |

Reflects the degree of data dispersion and accurately captures the actual forecasted data [70]. | 24 | |

| Measures | Criteria | Description | Equation | No of equation |

| MAE | Mean absolute error | Shows the mean distance between the actual and forecasted values | 25 | |

| MSE | Mean square error |

Reflects the degree of dispersion of the dataset [70]. | 26 | |

| RMSE | Root mean square error | Captures the average error between the forecasted value and the actual value [70]. | 27 | |

| R2 | Determination coefficient | Determines the proportion of the variance in the dependent variable that is predictable from the independent variables [71]. | 28 | |

| NRMSE | Normalized root mean square error | Normalizes the RMSE by dividing it by the average of the actual values. Prone to the influence of large outliers [72]. | 29 |

| No | Variables | Pearson correlation coefficient (r),(load and model inputs) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Last day relative humidity (%) | -0.4351 | |

| 2 | Last two days’ relative humidity (% | -0.4965 | |

| No | Variables | Pearson correlation coefficient (r), (load and model inputs) |

|

| 3 | Last week relative humidity (%) | -0.5302 | |

| 4 | Last day temperature (℃) | 0.4874 | |

| 5 | Last two days’ temperature (℃) | 0.5653 | |

| 6 | Last week temperature (℃) | 0.5676 | |

| 7 | Last day dew point (℃) | -0.0945 | |

| 8 | Last two days’ dew point (℃) | -0.2429 | |

| 9 | Last week’s dew point (℃) | -0.0421 | |

| 10 | Last day load (MW) | 0.7762 | |

| 11 | Last two days’ load (MW) | 0.7256 | |

| 12 | Last week load (MW) | 0.6457 | |

| Model | MAPE(%) | MAE (MW) | RMSE (MW) | MSE (MW) | NRMSE | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monday | |||||||

| LSSVM | 4.0025 | 586.6865 | 710.5824 | 504927.3971 | 0.0464 | 0.9593 | |

| LSSVM-BFOA | 1.9592 | 303.1394 | 374.5812 | 140311.0720 | 0.0244 | 0.9824 | |

| LSSVM-IBFOA | 1.4324 | 220.2668 | 280.5340 | 78699.33177 | 0.0183 | 0.9880 | |

| Tuesday-Thursday | |||||||

| LSSVM | 8.2086 | 1270.5557 | 1536.8228 | 2361824.3854 | 0.1013 | 0.5614 | |

| LSSVM-BFOA | 5.1020 | 809.2579 | 897.7997 | 806044.3621 | 0.0591 | 0.8357 | |

| LSSVM-IBFOA | 4.8542 | 735.9945 | 861.9280 | 742919.9222 | 0.0568 | 0.9451 | |

| Friday | |||||||

| LSSVM | 8.3786 | 1303.5522 | 1503.8283 | 2261499.7912 | 0.1010 | 0.8292 | |

| LSSVM-BFOA | 7.5746 | 1167.3021 | 1338.5298 | 1791662.0492 | 0.0899 | 0.8834 | |

| LSSVM-IBFOA | 7.2436 | 1116.3861 | 1292.7109 | 1671101.5480 | 0.0868 | 0.8901 | |

| Saturday | |||||||

| LSSVM | 3.7320 | 543.9430 | 661.4871 | 437565.1258 | 0.0462 | 0.8876 | |

| LSSVM-BFOA | 3.2253 | 464.7921 | 563.3847 | 317402.3313 | 0.0393 | 0.9295 | |

| LSSVM-IBFOA | 3.1348 | 449.5594 | 562.3752 | 316265.9746 | 0.0393 | 0.9606 | |

| Sunday | |||||||

| LSSVM | 4.4664 | 618.7235 | 789.2292 | 622882.7987 | 0.0577 | 0.4719 | |

| LSSVM-BFOA | 4.1507 | 577.6956 | 725.2978 | 526056.9152 | 0.0530 | 0.7405 | |

| LSSVM-IBFOA | 4.1427 | 566.0997 | 652.6199 | 425912.8607 | 0.0477 | 0.9479 | |

| Average | |||||||

| LSSVM | 5.7576 | 864.6922 | 1040.3900 | 1237739.8996 | 0.0705 | 0.7419 | |

| LSSVM-BFOA | 4.4024 | 664.4374 | 779.986 | 716295.3460 | 0.0532 | 0.8743 | |

| LSSVM-IBFOA | 4.1615 | 617.6613 | 730.0336 | 646979.9275 | 0.0498 | 0.9464 | |

| Day-type | Algorithm | Convergence time (minutes) |

|---|---|---|

| Monday | BFOA | 44.6826 |

| IBFOA | 38.1281 | |

| T Tuesday-Thursday | BFOA | 31.2697 |

| IBFOA | 26.9290 | |

| Friday | BFOA | 25.8514 |

| IBFOA | 16.5285 | |

| Saturday | BFOA | 35.5887 |

| IBFOA | 21.7109 | |

| Sunday | BFOA | 33.8185 |

| IBFOA | 31.6932 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).