Submitted:

10 June 2024

Posted:

11 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Research Area

2.2. Data Acquisition and Pre-Processing

- Digital Elevation Model (DEM): The data overview map of the research area is made using data from the ASTER GDEM 30m product available on the Geospatial Data Cloud (http://www.gscloud.cn)[9];

- Monthly total precipitation and average temperature are sourced from the National Tibetan Plateau Data Center (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn). The data has a resolution of 1 km and is stored in nc file format[10,11];

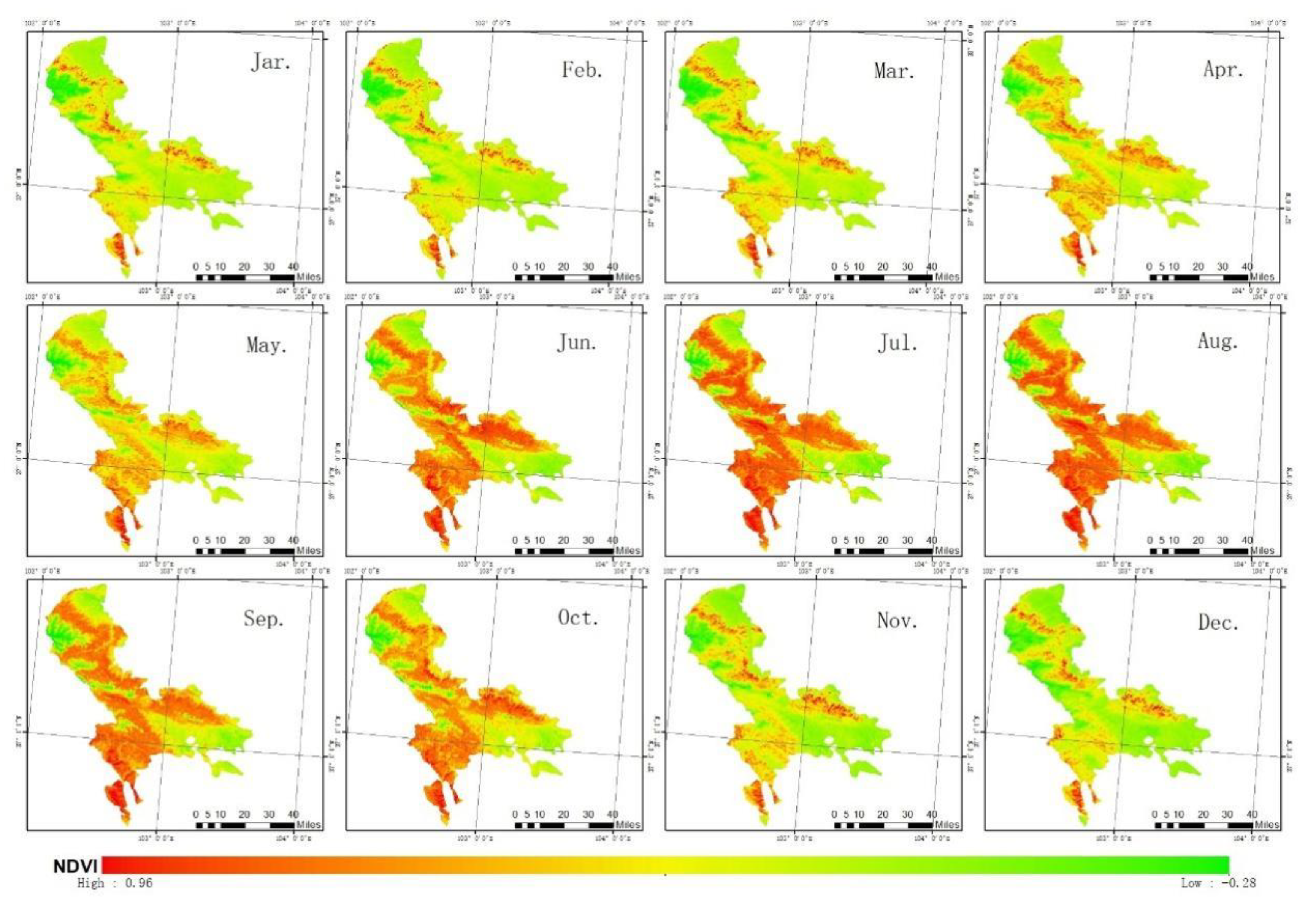

- Monthly NDVI for 2020 is sourced from the National Tibetan Plateau Data Center (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn). The data has a spatial resolution of 250 meters and is synthesized using the monthly maximum value composite method based on the 16-day composite monthly products provided by the MOD13Q1 product of the Aqua/Terra-MODIS satellite sensor[12];

- Monthly total solar radiation data is sourced from the single-level ERA5 hourly data from 1940 to the present provided by Copernicus Climate Change Service of European Space Agency (https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/). The data is stored in GRIB file format and has a resolution of 0.1° × 0.1°[13];

- The MODIS17A13v061 product is sourced from the MODIS/Terra Gross Primary Productivity 8-Day L4 Global 500m SIN Raster V061. This data was distributed by the NASA’ s Earth Observing System Data and Information System (NASA EOSDIS) in 2021[14].

- Forest resource data is sourced from the Management Center of Gansu Qilian Mountain National Nature Reserve;

| Data Name | Data Type | Format | Data Resource |

| DEM | Raster | Tif(30m×30m) | Geospatial Data Cloud(http://www.gscloud.cn) |

| Monthly Average Temperature Monthly Total Precipitation |

Raster | nc(1km×1km) | National Tibetan Plateau Data Center (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn) |

| NDVI | Raster | nc(250m×250m) | National Tibetan Plateau Data Center(https://data.tpdc.ac.cn) |

| Monthly Total Solar Radiation | Raster | GRIB(0.1°×0.1°) | Copernicus Climate Change Service of European Space Agency (https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/) |

| MODIS17A | Raster | hdr | NASA’s Earth Observing System Data and Information System (https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/) |

| Forest Resource Inventory | Vector | Shp | Zhangye Branch of the Gansu Administration Bureau, Qilian Mountain National Park |

2.3. Research Method

2.3.1. Classification of Forest Vegetation

2.3.2. CASA Model

3. Pixel-Scale Calculation of NPP, Carbon Density, and Carbon Storage

3.1. Calculation of NPP with CASA Model

3.2. Estimation of Carbon Storage and Carbon Density

4. Discussion and Findings

4.1. Discussion

4.2. Findings

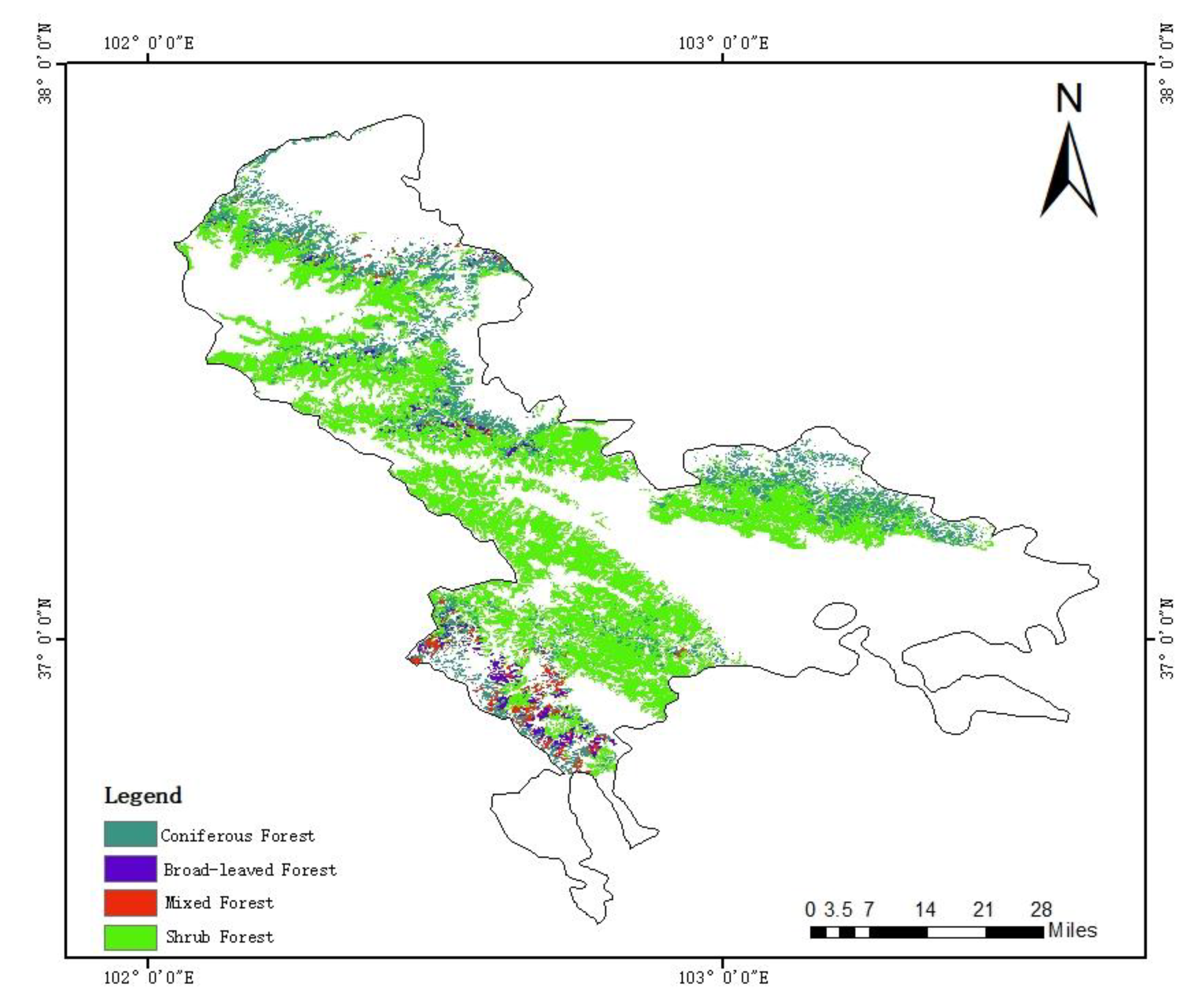

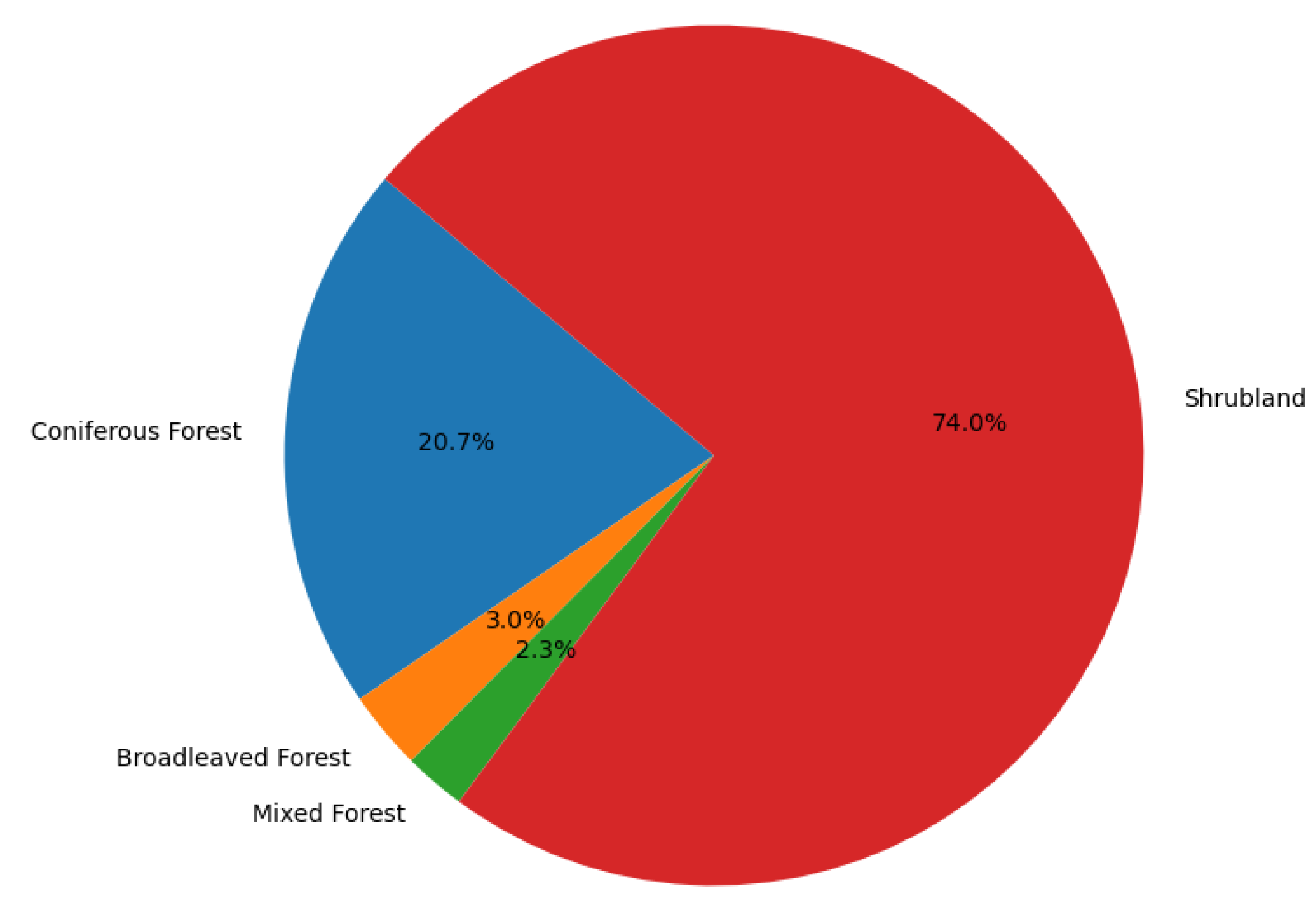

- The total forest area in Tianzhu County is 25,606.325 km². Coniferous forests, broad-leaved forests, mixed forests, and shrub forests make up the majority of the vegetation types; they make up 20.69%, 2.78%, 2.34%, and 74% of the total area, respectively.

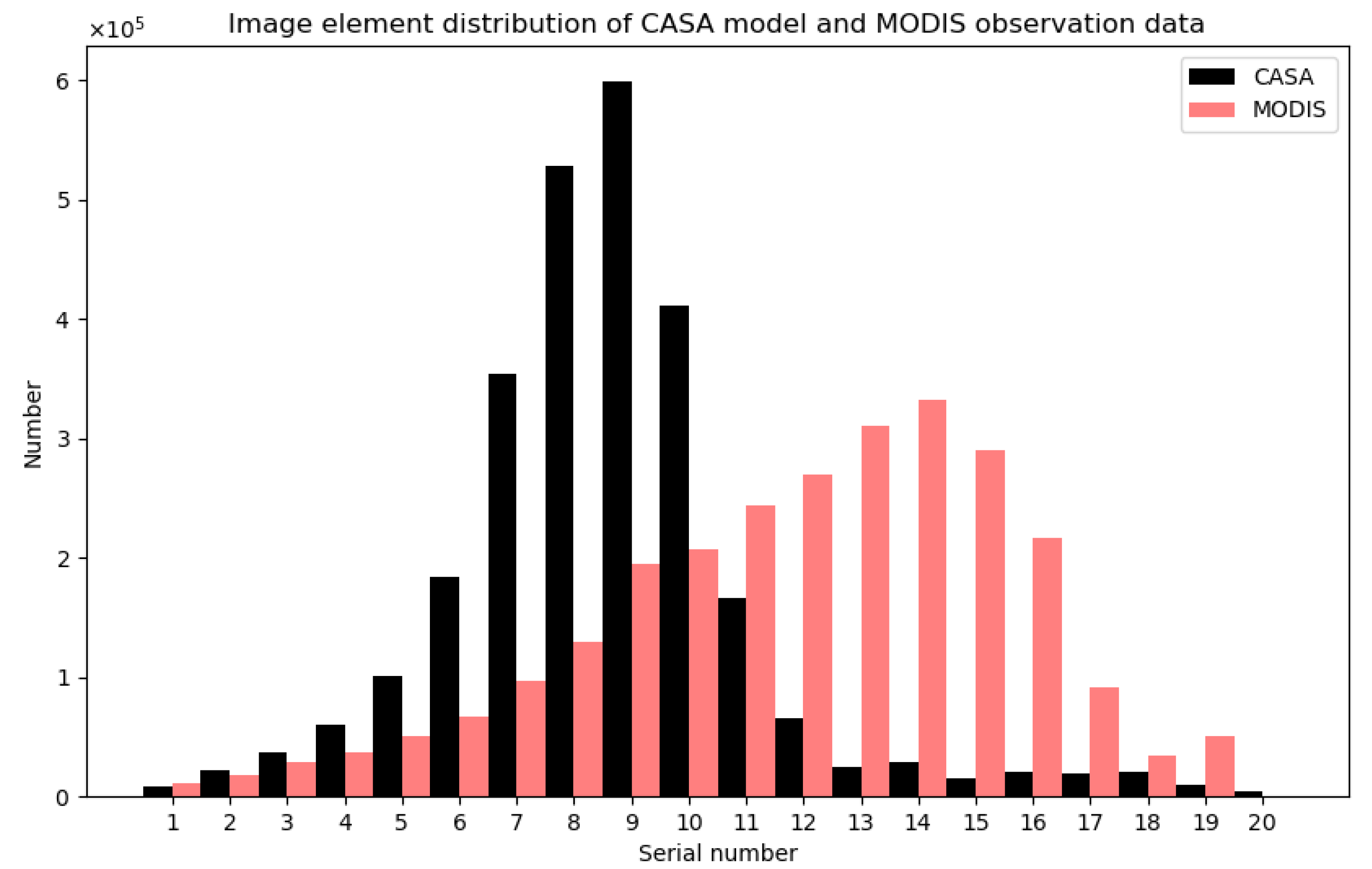

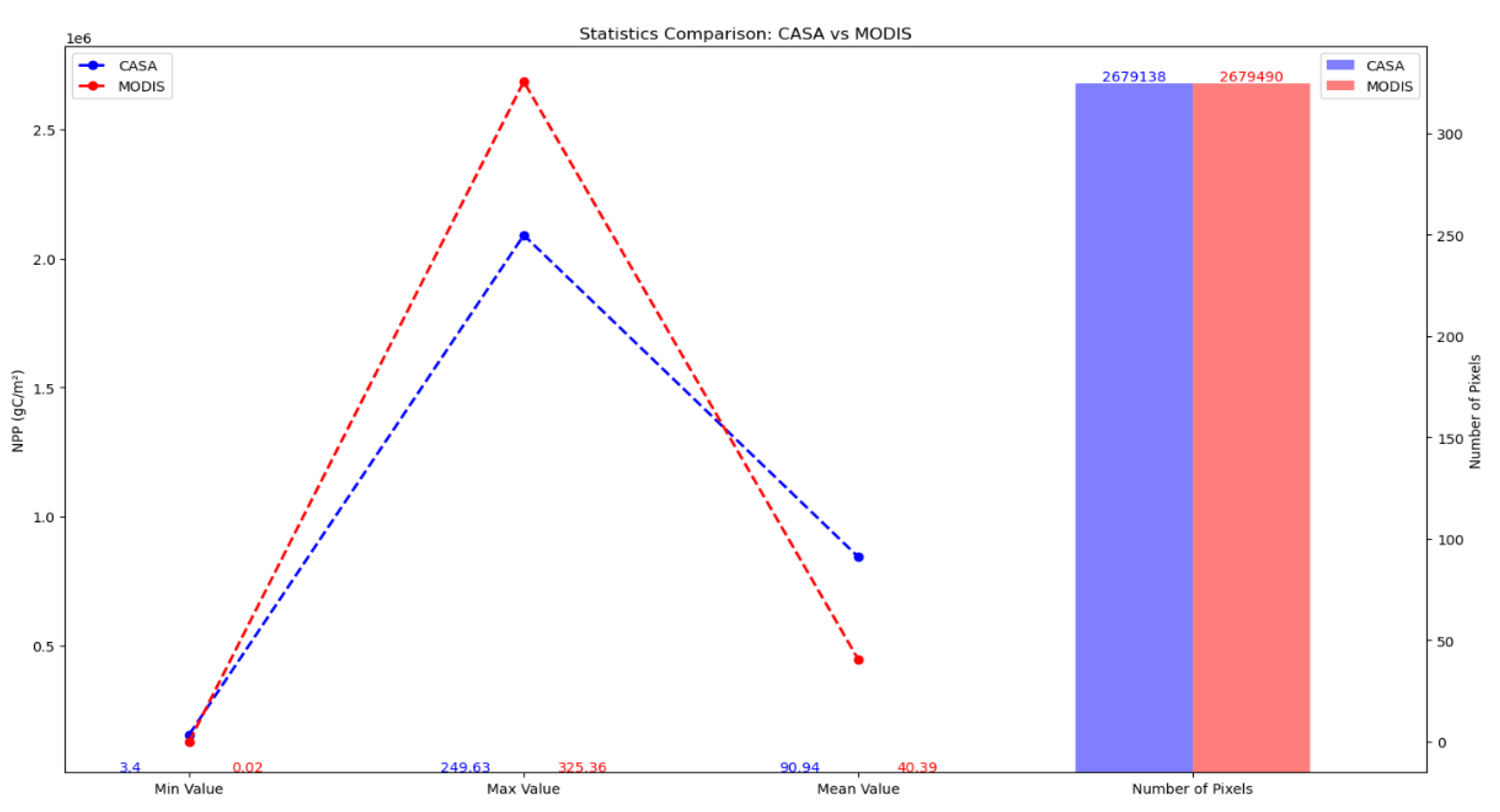

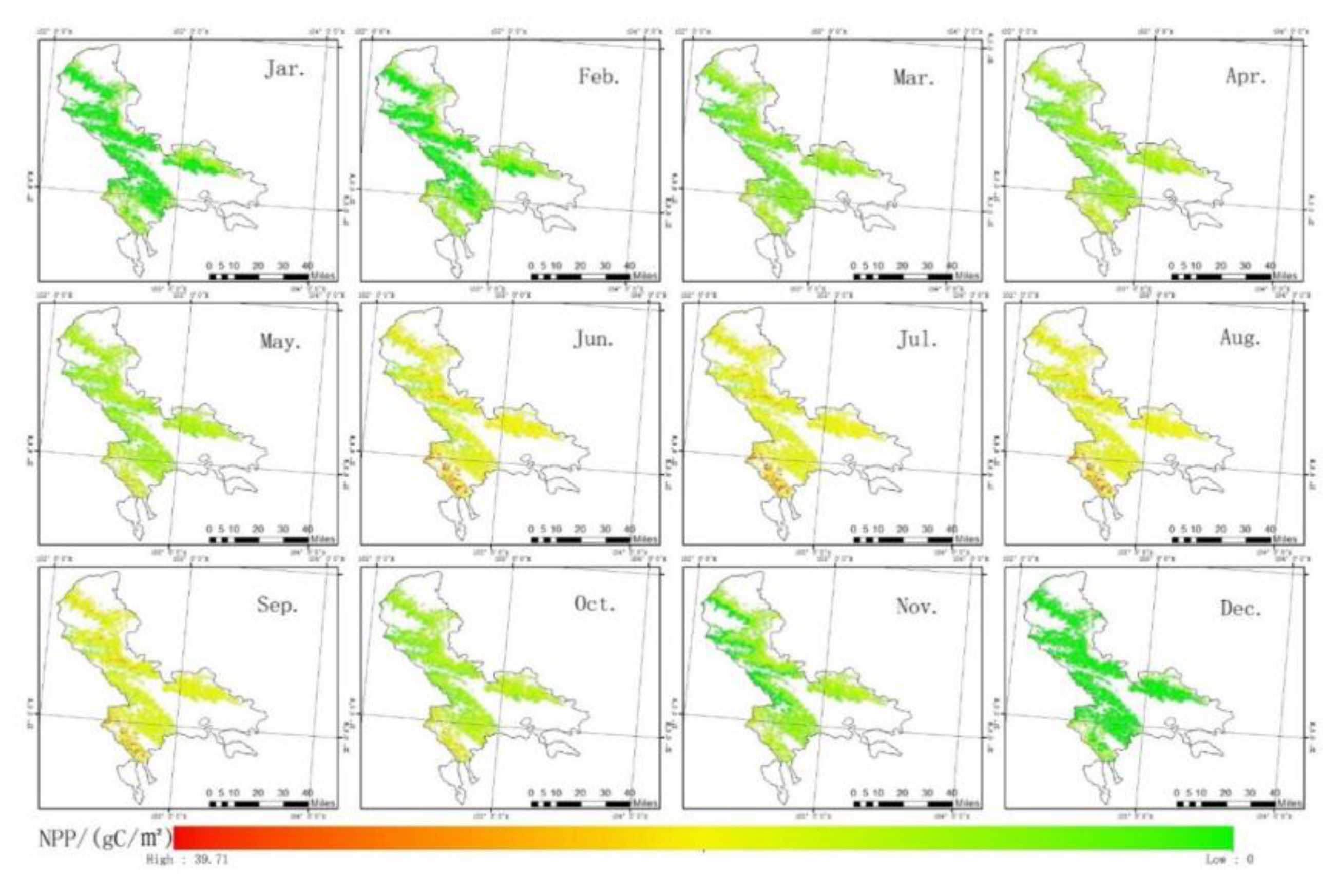

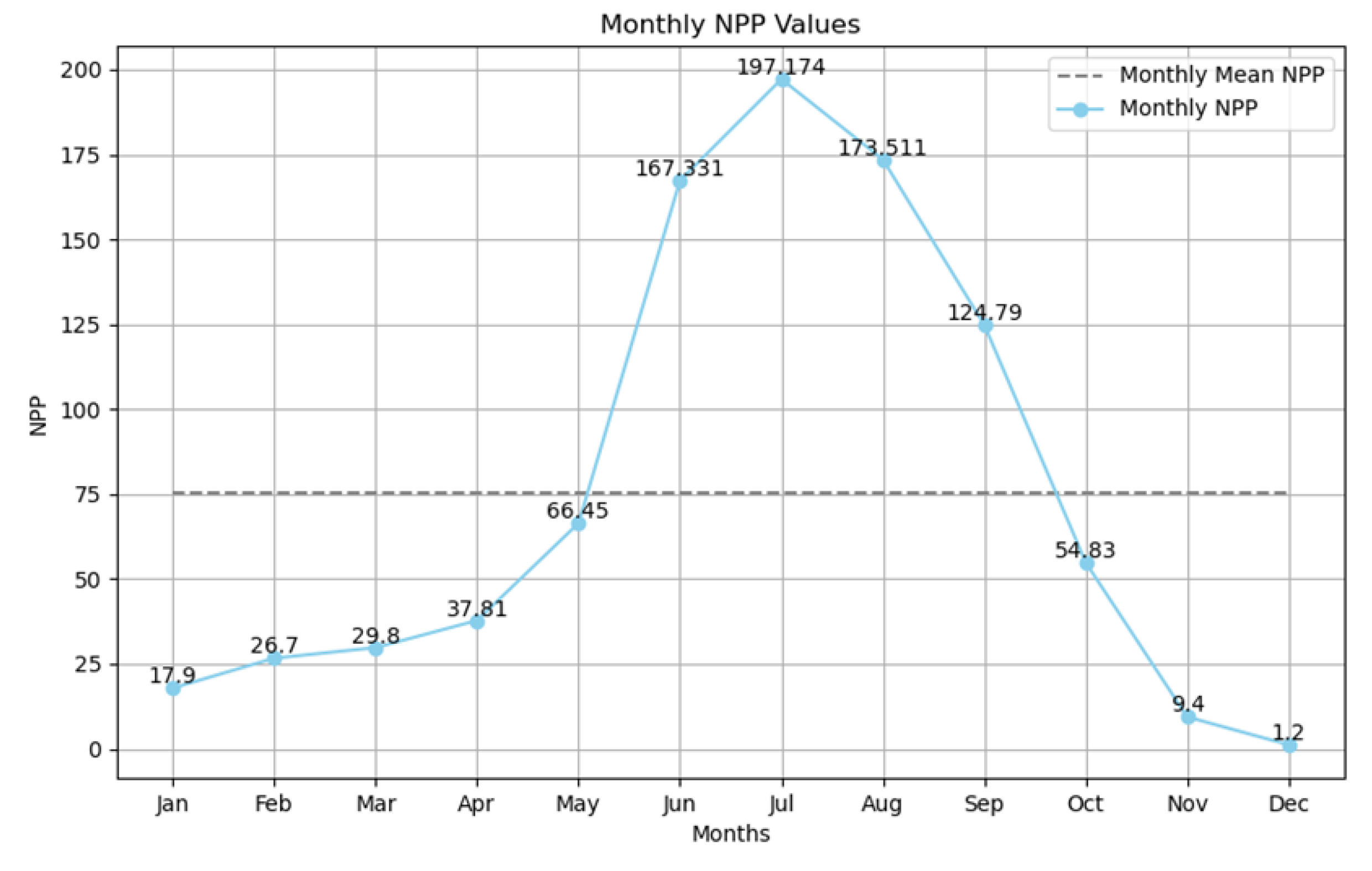

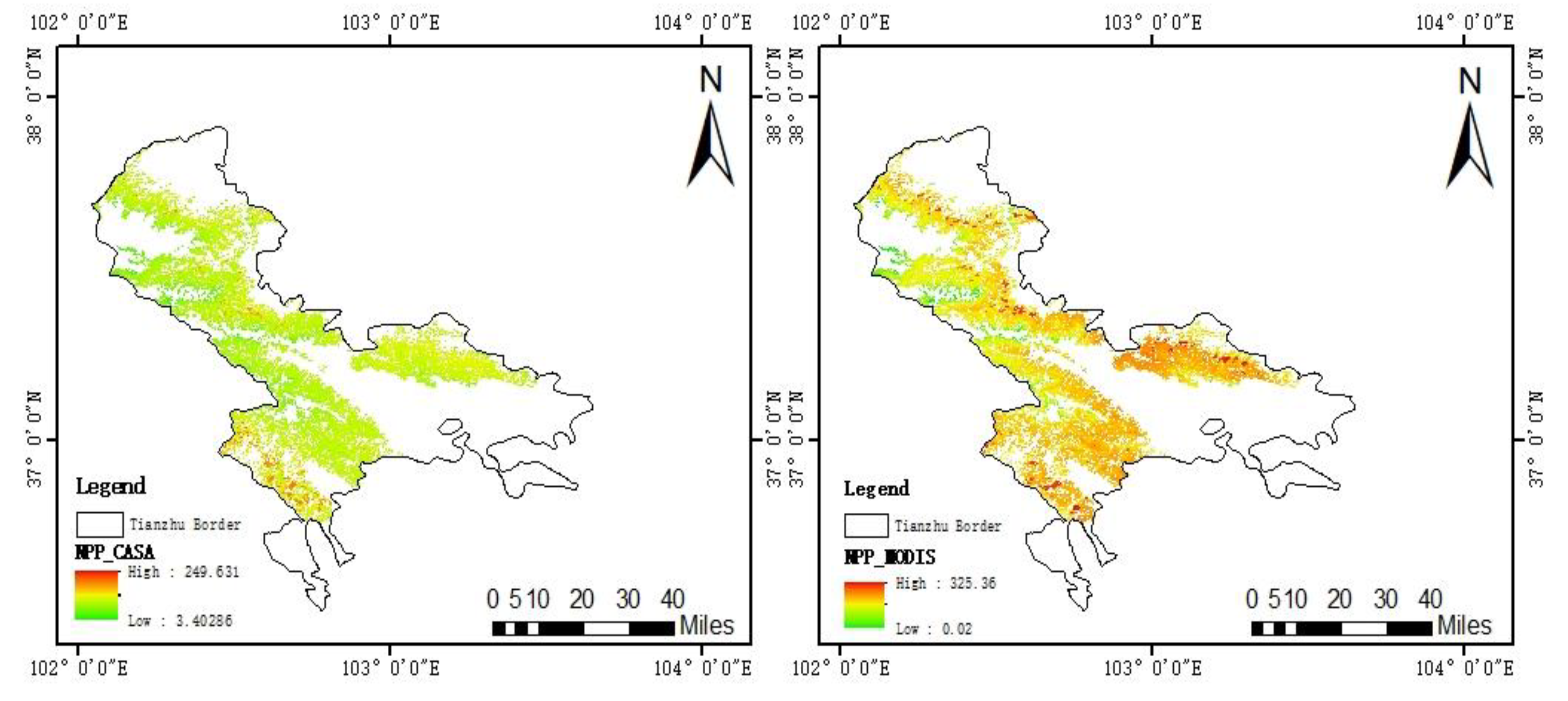

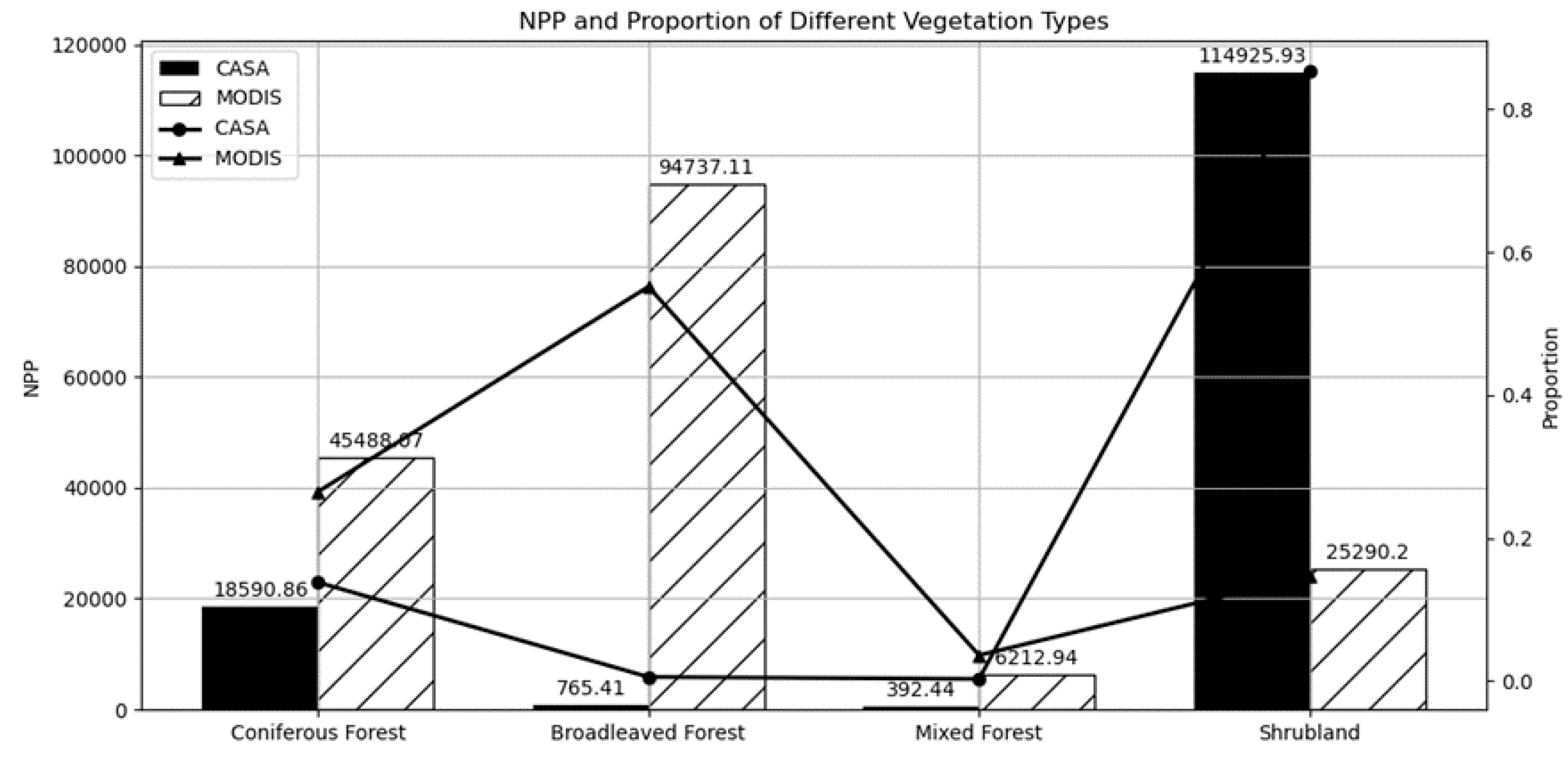

- According to the CASA model calculations, the annual cumulative NPP in Tianzhu County for 2020 ranged from a maximum of 249.63 gC/m² to a minimum of 3.40 gC/m², with a total forest net primary productivity of 134,674.65 tons of carbon. Of these, shrub forests accounted for 114,925.93 tons of carbon, representing 85.34% of the total; coniferous forests accounted for 18,590.86 tons of carbon, representing 13.80%; broad-leaved forests accounted for 765.41 tons, representing 0.57%; and mixed forests accounted for 392.44 tons, representing 0.29%. Based on MODIS17A observational data, the annual cumulative NPP ranged from a maximum of 325.36 gC/m² to a minimum of 0.02 gC/m², with a total forest net primary productivity of 171,728.32 tons of carbon. Of these, broad-leaved forests accounted for 94,737.11 tons of carbon, representing 55.17%; coniferous forests accounted for 45,488.07 tons of carbon, representing 26.47%; mixed forests accounted for 6,212.94 tons, representing 3.62%; and shrublands accounted for 25,290.20 tons, representing 14.73%.

- Tianzhu County has 361,700 tons of total forest carbon stored at the pixel level. With 313,600 tons, or 86.70% of total carbon storage, shrub forests have the highest carbon storage capacity. Coniferous forest vegetation has a carbon storage of 46,500 tons, accounting for 12.86%. Broad-leaved forest and mixed forest have a carbon storage of 1,100 tons and 500 tons, respectively, accounting for 0.30% and 0.14%.

References

- Li, L. Estimation of Forest Carbon Storage and Response of NPP to Climate Change in the Altai Mountains [D]. Xinjiang Agricultural University, 2019. [CrossRef]

- We, D. Temporal and Spatial Changes of Forest Biomass in China and Its Response to Climate Change [D]. Nanjing Forestry University, 2018.

- Binglun, W.; Ming, C.; Sixiang, Q.; et al. Assessment and Analysis of Forest Ecosystem Carbon Storage in the Ecological Green Heart Area of the Chang-Zhu-Tan Urban Agglomeration [J/OL]. Journal of Northwest Forestry University Retrieved April 29, 2024. 1–10.

- Yuqing, X.; Fengjin, X.; Li, Y. Review of the Spatiotemporal Distribution of Net Primary Productivity in Chinese Forest Ecosystems and Its Response to Climate Change. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 2020, 40, 4710–4723. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, F.; Yongjie, Y.; Pengwu, Z. Research Progress on Forest Carbon Storage Accounting and Carbon Sequestration Potential Evaluation under the Carbon Neutral Vision [J/OL]. Journal of Inner Mongolia Agricultural University (Natural Science Edition) Retrieved April 29, 2024. 2024, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Wenyao. Making Facility Agriculture the “Engine” for Promoting Scientific Development in Tianzhu—Thoughts on the Development of Facility Agriculture in Tianzhu County. Gansu Agriculture 2010, 60–63. [CrossRef]

- He Junsheng, Gong Dajie, Huang Qitong, et al. Study on the Diversity and Zoogeography of Terrestrial Wild Vertebrates in Tianzhu County, Qilian Mountains. Journal of Arid Land Resources and Environment, 2020, 34, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang Meiwen. Study on the Environmental Status of the Wushaoling Area in the Qilian Mountains Based on the PSR Model [D]. Huazhong University of Science and Technology, 2019. [CrossRef]

- The data set is provided by Geospatial Data Cloud site, Computer Network Information Center, Chinese Academy of Sciences. (http://www.gscloud.cn).

- Peng, S. (2020). 1-km monthly precipitation dataset for China (1901-2022). National Tibetan Plateau / Third Pole Environment Data Center. [CrossRef]

- Peng, S. (2020). 1-km monthly maximum temperature dataset for China (1901-2022). National Tibetan Plateau / Third Pole Environment Data Center. [CrossRef]

- Gao, J. , Shi, Y., Zhang, H., Chen, X., Zhang, W., Shen, W., Xiao, T., Zhang, Y. (2023). China regional 250m normalized difference vegetation index data set (2000-2023). National Tibetan Plateau / Third Pole Environment Data Center. https://cstr.cn/18406.11.Terre.tpdc.300328. [CrossRef]

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Biavati, G.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Rozum, I.; Schepers, D.; Simmons, A.; Soci, C.; Dee, D.; Thépaut, J.-N. (2023): ERA5 hourly data on single levels from 1940 to present. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS). [CrossRef]

- Running, S. Mu, M. Zhao. <italic>MODIS/Terra Gross Primary Productivity 8-Day L4 Global 500m SIN Grid V061</italic>. 2021, distributed by NASA EOSDIS Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center.

- Wenquan, Z.; Yaozhong, P.; Jinshui, Z. Remote Sensing Estimation of Net Primary Productivity of Terrestrial Vegetation in China. Chinese Journal of Plant Ecology 2007, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenquan, Z.; Yaozhong, P.; Hao, H.; et al. Simulation of Maximum Light Use Efficiency for Typical Vegetation in China. Chinese Science Bulletin 2006, 700–706. [Google Scholar]

- Simulation of Maximum Light Use Efficiency for Some Typical Vegetation Types in China. Chinese Science Bulletin 2006, 457–463.

- QGIS.org, 2024. QGIS Geographic Information System. QGIS Association. http://www.qgis.org.

- R Core Team (2024). _R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing_. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/.

- Hijmans R (2023). _raster: Geographic Data Analysis and Modeling_. R package version 3.6-26, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=raster.

- Pebesma, E.; Bivand, R. (2023).Spatial Data Science: With Applications in R. Chapman and Hall/CRC. [CrossRef]

- Bivand, R.; Keitt, T.; Rowlingson, B. (2023). _rgdal: Bindings for the 'Geospatial' Data Abstraction Library_. R package version 1.6-7, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rgdal.

- Python Software Foundation. (2024). Python (Version 3.12) [Software]. Available from https://www.python.org/.

- JetBrains. (2024). PyCharm Community Edition (Version 2024.1.1) [Software]. Available from https://www.jetbrains.com/pycharm/.

- Anaconda, Inc. (2024). Anaconda Distribution (Version 24.4.0) [Software]. Available from https://www.anaconda.com/.

- Microsoft Corporation. (2024). Microsoft Excel (Version 2024) [Software]. Available from https://www.microsoft.com/.

- Microsoft Corporation. (2024). Microsoft Word (Version 2021) [Software]. Available from https://www.microsoft.com/.

- Jiyuan, L.; Zengxiang, Z.; Shuwen, Z.; et al. Review and Prospect of Remote Sensing Research on Land Use Change in China—Guided by the Academic Thought of Chen Shupeng. Journal of Geo-Information Science 2020, 22, 680–687. [Google Scholar]

- Potter, C.S.; Randerson, J.T.; Field, C.B.; et al. Terrestrial ecosystem production: A process model based on global satellite and surface data. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 1993, 7, 811–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilong, P.; Jingyun, F.; Qinghua, G. Estimating Net Primary Productivity of Vegetation in China Using the CASA Model. Chinese Journal of Plant Ecology 2001, 603–608. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Z.; Guangsheng, Z.; Yuhui, W. Dynamic Simulation of Net Primary Productivity of Typical Grassland Vegetation in Inner Mongolia Based on the CASA Model. Chinese Journal of Plant Ecology 2008, 32, 786–797. [Google Scholar]

- Wenrui, L.; Xiaoting, L.; Tong, L.; et al. Analysis of the Characteristics of Forest Vegetation NPP Changes and Their Influencing Factors in Yichun City Based on MODIS and CASA Model. Chinese Journal of Ecology, 2022, 41, 150–158. [Google Scholar]

- Zhe, L.; Xudong, G.; Chun, G.; et al. (2016). Inversion of Grassland Photosynthetic Effective Radiation Absorption Rate Based on Hyperspectral Absorption Characteristics. National Remote Sensing Bulletin 2016, 20, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhenyu, Z. Estimation and Spatial Distribution of Forest Carbon Storage in Qingpu District Based on Forest Resource Inventory and Remote Sensing Data [D]. Shanghai Normal University, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kajimoto, T.; Matsuura, Y.; Sofronov, M.A.; et al. Above- and belowground biomass and primary productivity of a Larix gmelinii stand near Tura, central Siberia. Tree Physiology 1999, 19, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar JI, N.; Sajish, P.R.; Kumar, R.N.; et al. Biomass and Net Primary Productivity in Three Different Aged Butea Forest Ecosystems in Western India, Rajasthan. Iranica Journal of Energy & Environment 2011, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, E.D.; Lieth HF, H. Patterns of Primary Production in the Biosphere. Journal of Ecology 1978, 68, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roxburgh, S.H.; Berry, S.L.; Buckley, T.N.; et al. What is NPP? Inconsistent accounting of respiratory fluxes in the definition of net primary production. Functional Ecology 2005, 19, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengjing, H. Remote Sensing Estimation of Natural Grassland Productivity in China and Study on the Causes of Its Spatiotemporal Changes [D]. Lanzhou University, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Shanghai Landscaping and City Appearance Administrative Bureau. DB31/T 1234-2020 Technical Regulations for Carbon Sequestration Measurement and Monitoring of Urban Forests [S]. Beijing:Standard Press of China, 2020.

- Yurong, Z.; Zhenliang, Y.; Shidong, Z. Carbon Storage and Carbon Balance of Major Forest Ecosystems in China. Chinese Journal of Plant Ecology 2000, 518–522. [Google Scholar]

- Weijie, Z.; Weikai, B.; Bing, G.; et al. (2007). Carbon Content and Characteristics of Terrestrial Higher Plants. Chinese Journal of Ecology 2007, 307–313. [Google Scholar]

- National Forestry Administration. Guidelines for Carbon Sequestration Measurement and Monitoring of Afforestation Projects (LY/T 2253-2014) [S]. Beijing: Standard Press of China, 2014.

| Primary Classification | Secondary Classification | Third-level Classification |

| Forestland | Arboreal Forest | Coniferous Forest Broad-leaved Forest Mixed Forest |

| Shrub Forest | Dominant Shrub Other Shrubs |

| Code | Forest Type | NDVImax | NDVImin | SRmax | SRmin | Emax |

| 1 | Coniferous forest | 0.665 | 0.023 | 4.993212 | 1.05 | 0.437 |

| 2 | Broad-leaved Forest | 0.680 | 0.023 | 5.265886 | 1.05 | 0.839 |

| 3 | Mixed Forest | 0.672 | 0.023 | 5.131049 | 1.05 | 0.638 |

| 4 | Shrub Forest | 0.639 | 0.023 | 4.540166 | 1.05 | 0.429 |

| No. | Range | No. | Range | No. | Range | No. | Range |

| C1 | 3.40-22.71 | C11 | 102.86-11.55 | M1 | 0.02-11.29 | M11 | 38.27-40.02 |

| C2 | 22.71-35.27 | C12 | 111.55-125.07 | M2 | 11.29-16.1 | M12 | 40.02-41.63 |

| C3 | 35.27-45.89 | C13 | 125.07-140.52 | M3 | 16.1-19.98 | M13 | 41.63-43.18 |

| C4 | 45.89-56.51 | C14 | 140.52-153.07 | M4 | 19.98-23.36 | M14 | 43.18-44.72 |

| C5 | 56.51-67.13 | C15 | 153.07-165.62 | M5 | 23.36-26.43 | M15 | 44.72- 46.42 |

| C6 | 67.13-75.82 | C16 | 165.62-177.21 | M6 | 26.43-29.35 | M16 | 46.42-48.54 |

| C7 | 75.82-83.55 | C17 | 177.21-185.90 | M7 | 29.35-32 | M17 | 48.54-52.64 |

| C8 | 83.55-89.35 | C18 | 185.90-194.59 | M8 | 32 -34.30 | M18 | 52.64-58.35 |

| C9 | 89.35-95.13 | C19 | 194.59-204.25 | M9 | 34.30-36.35 | M19 | 58.35-159.52 |

| C10 | 95.13-102.86 | C20 | 204.25-249.63 | M10 | 36.35-38.27 | M20 | 159.52-324.46 |

| Code | Dominant Tree Species | CF |

| 120 | Qinghai spruce | 0.52 |

| 150 | larch | 0.521 |

| 200 | Chinese pine | 0.511 |

| 350 | Qilian juniper | 0.51 |

| 421 | poplar | 0.49 |

| 490 | Other hardwood broadleaved forests | 0.497 |

| 530 | birch | 0.496 |

| 590 | Other softwood broadleaved forests | 0.485 |

| 610 | Coniferous and mixed forest | 0.51 |

| 620 | Broad-leaved and mixed forest | 0.495 |

| 630 | Coniferous and broad-leaved mixed forest | 0.498 |

| 904-999 | Shrub forest | 0.483 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).