Submitted:

10 June 2024

Posted:

11 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Field Oriented Architecture of Induction Motor System

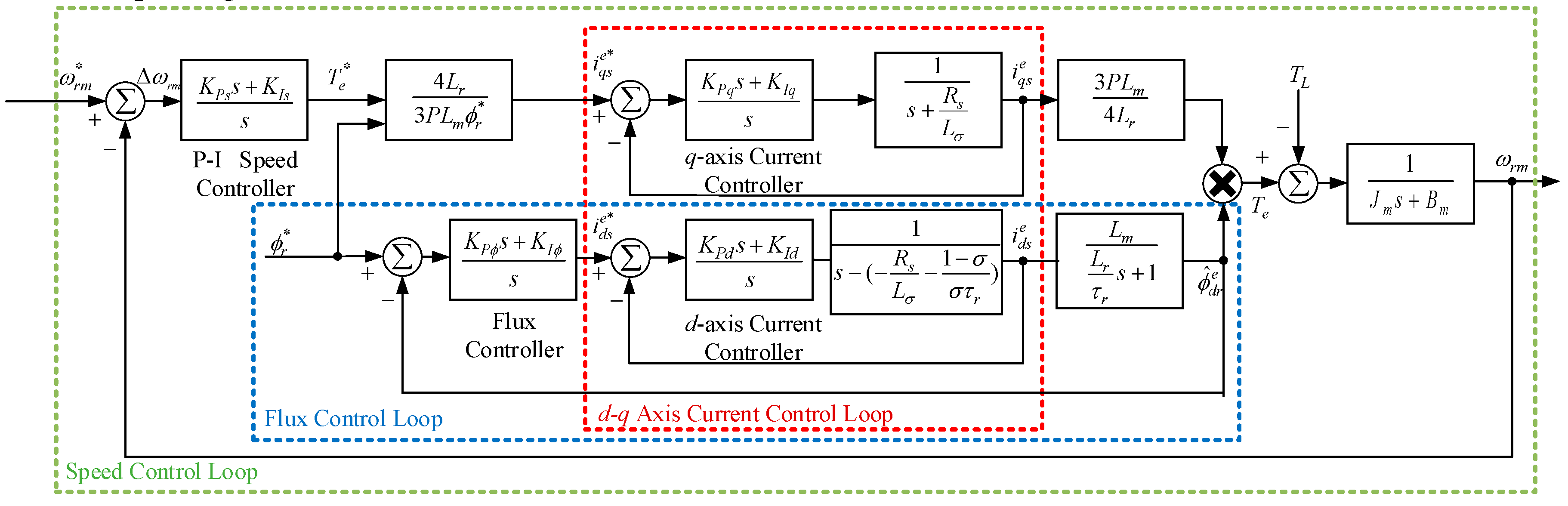

2.1. Dynamic Equation of FOC

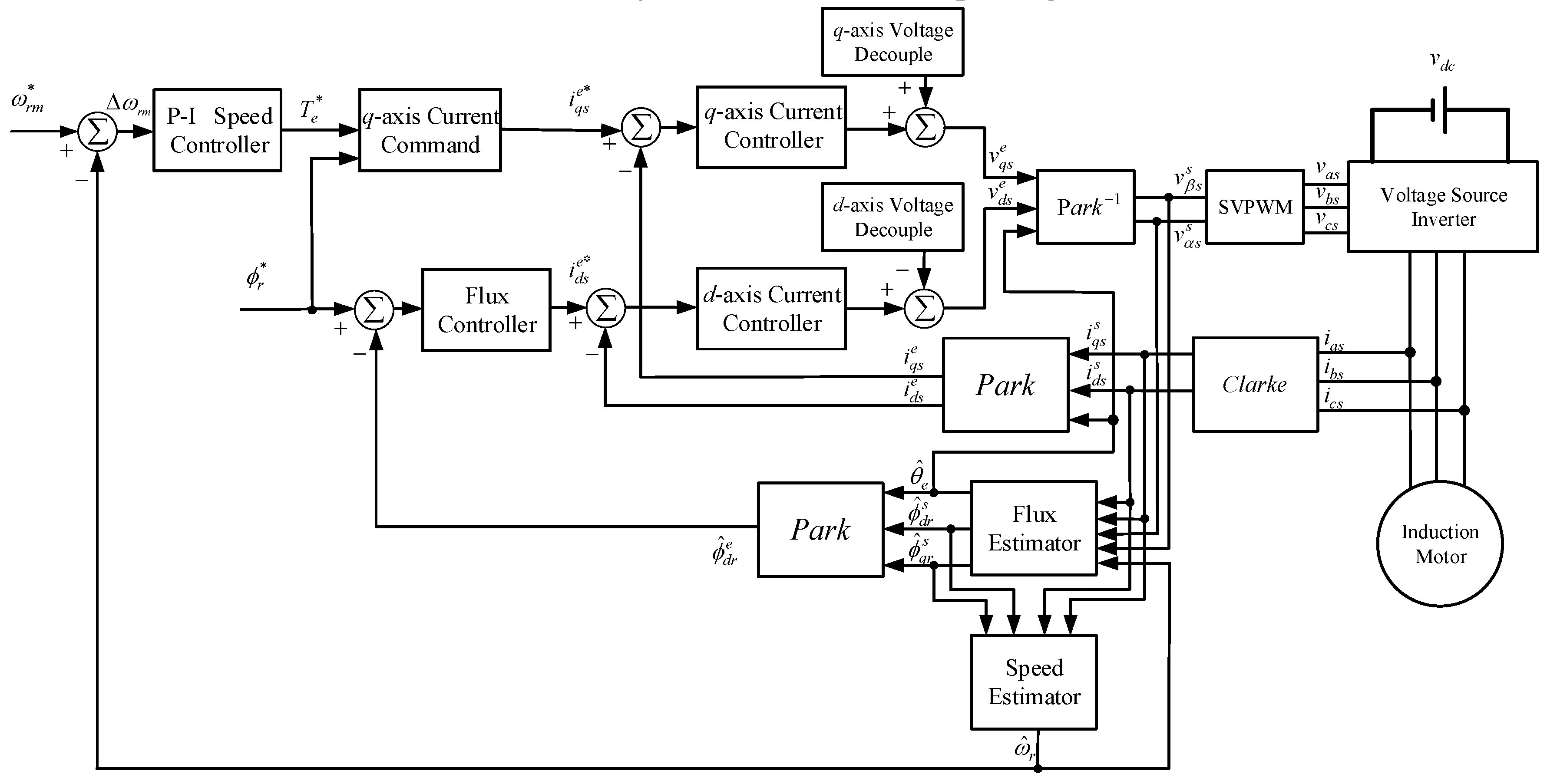

2.2. Sensorless FOC System for Induction Motors

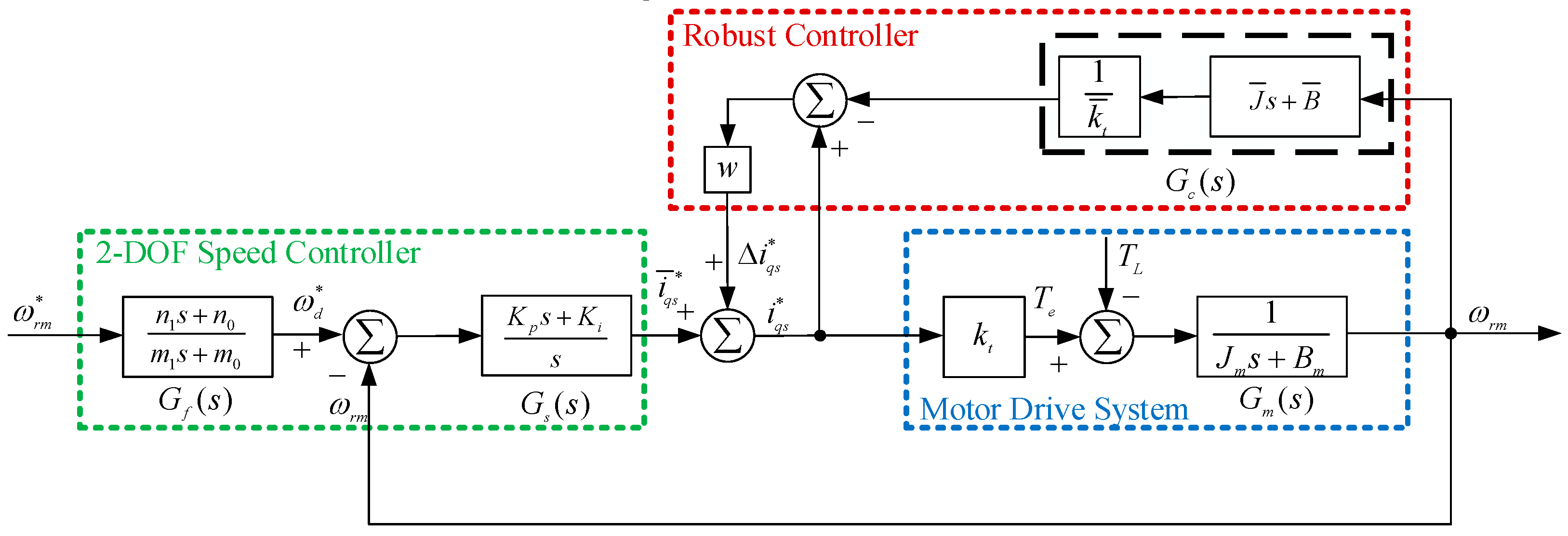

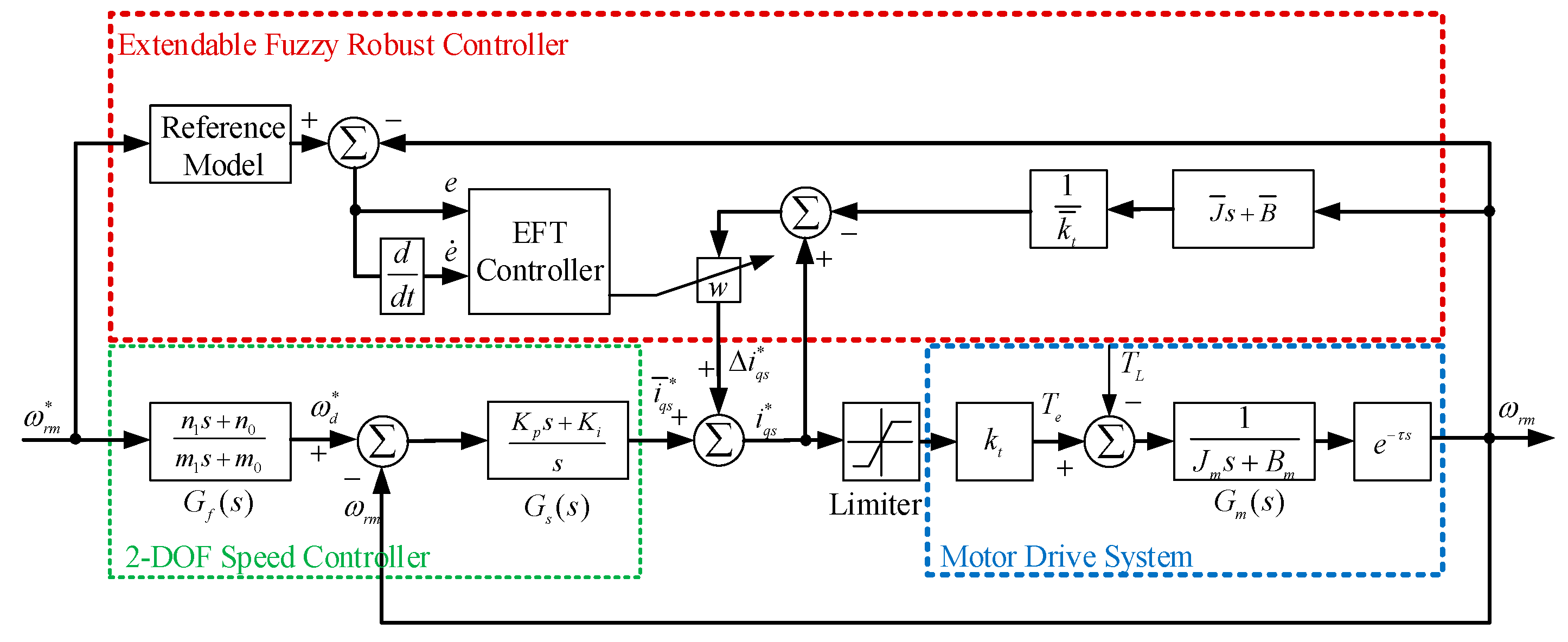

3. The Design of Robust 2DOF Controller with EFT Proposed

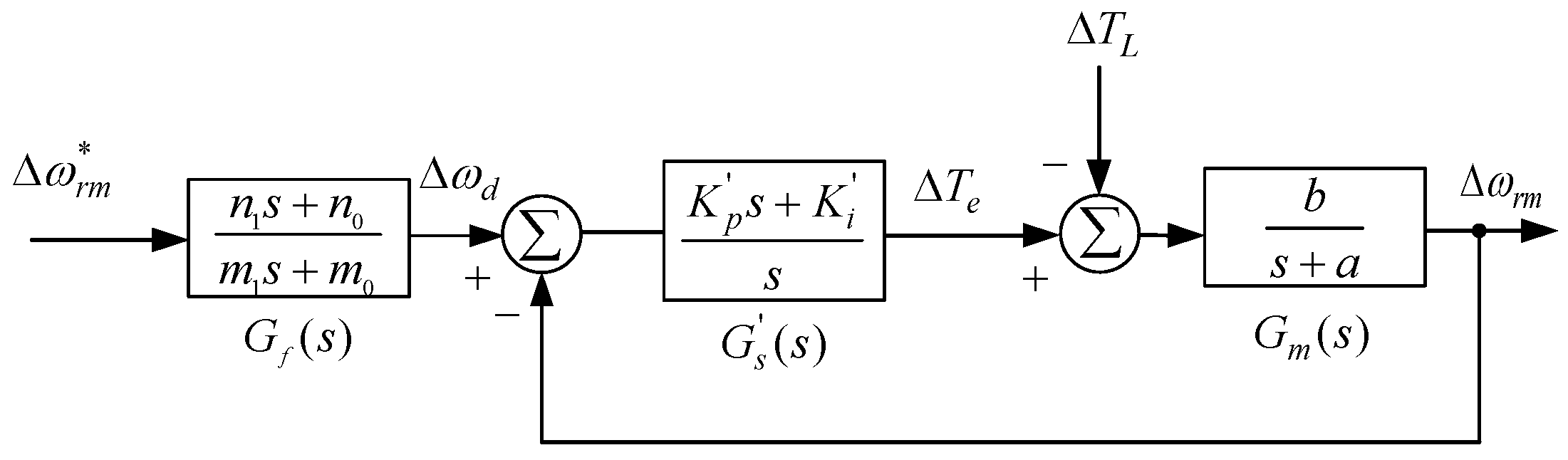

3.1. Quantitative Design of 2DOF Speed Controller

- (1)

- The steady-state error of step response for speed command and load disturbance was zero.

- (2)

- There was no overshoot in step response for speed command.

- (3)

- The response time for the step command following was defined as the time required = 0.15s for the response to rise from zero to final value.

- (4)

- The maximum speed drop caused by variation of unit step load was = 30rpm.

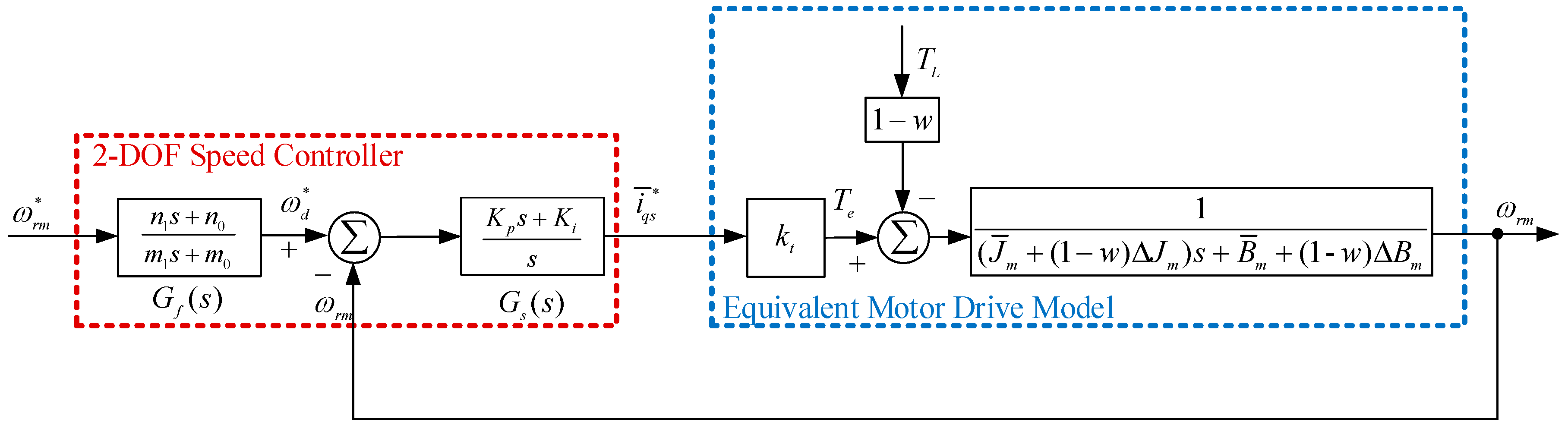

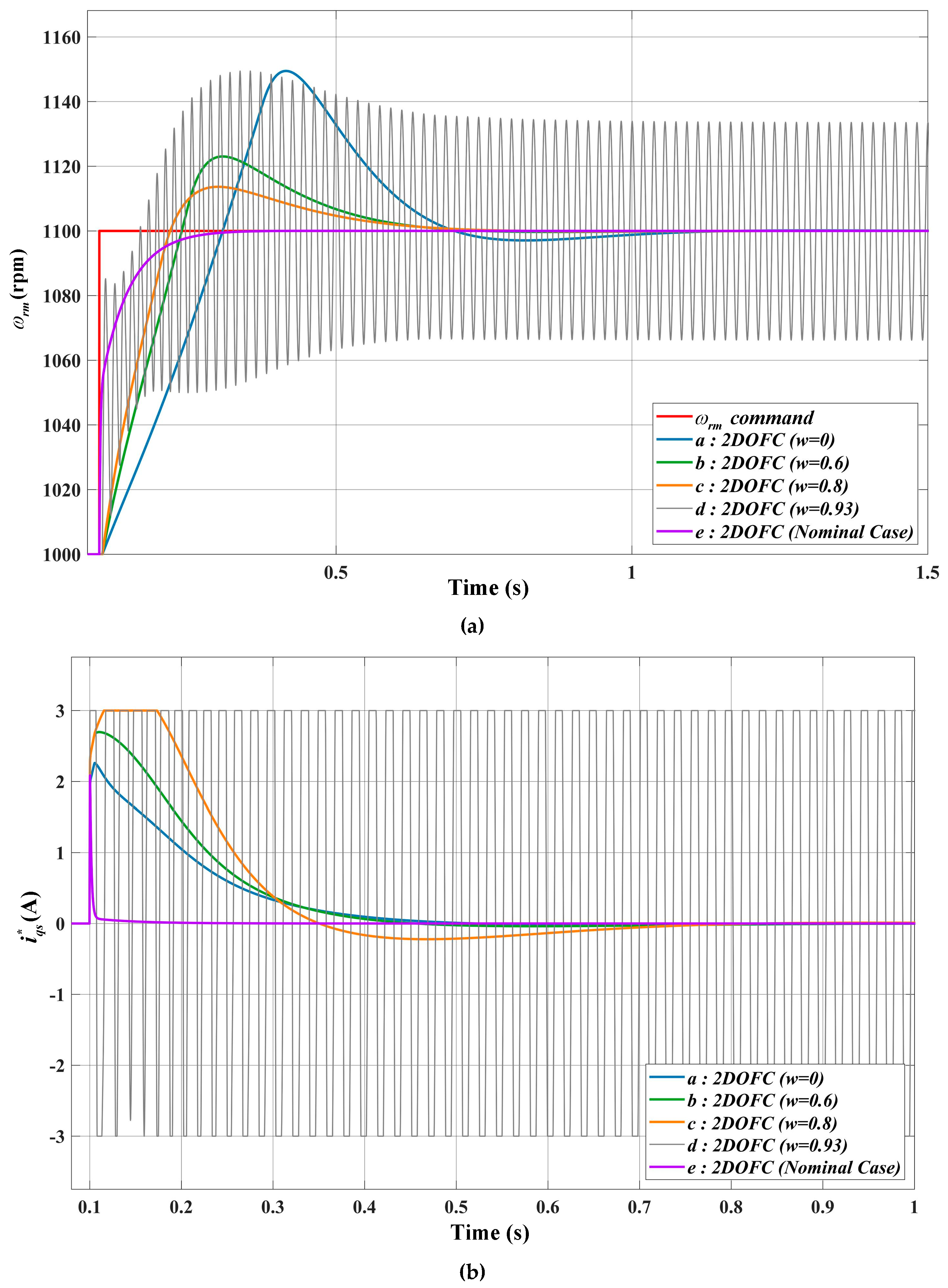

3.2. Robust 2DOF Controller with Fixed Weighting Factor

3.3. Extendable Fuzzy Theory (EFT)

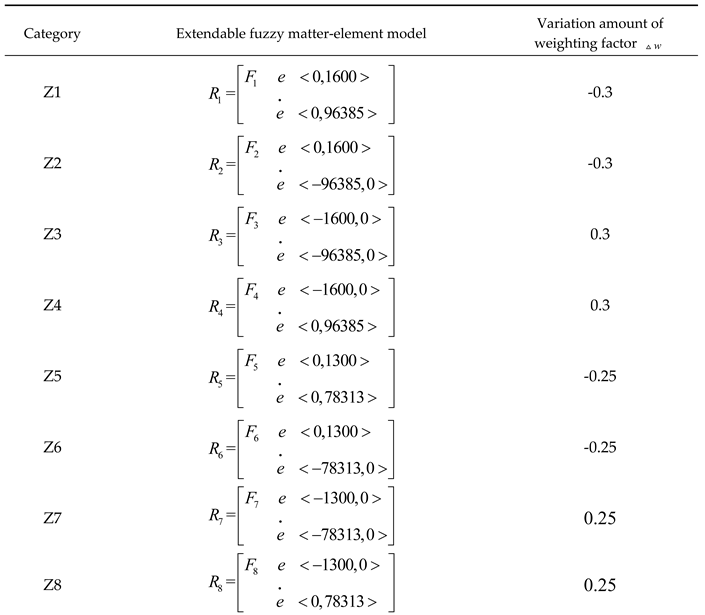

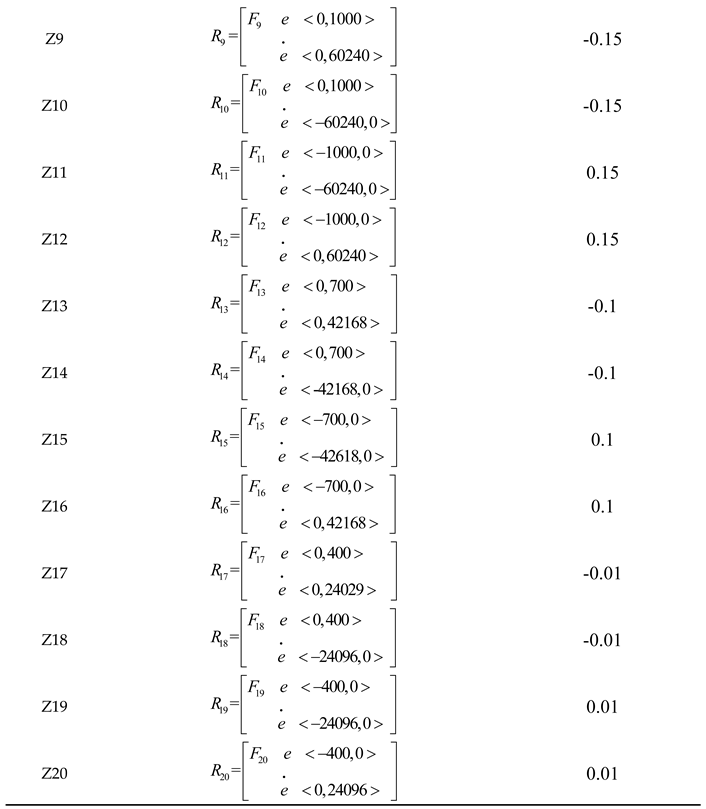

3.3.1. Extendable Fuzzy Matter-Element Model

3.3.2. Definition for Classical Domain and Neighborhood Domain of EFT

3.3.3. Distance and Rank Value

3.3.4. Correlation Function

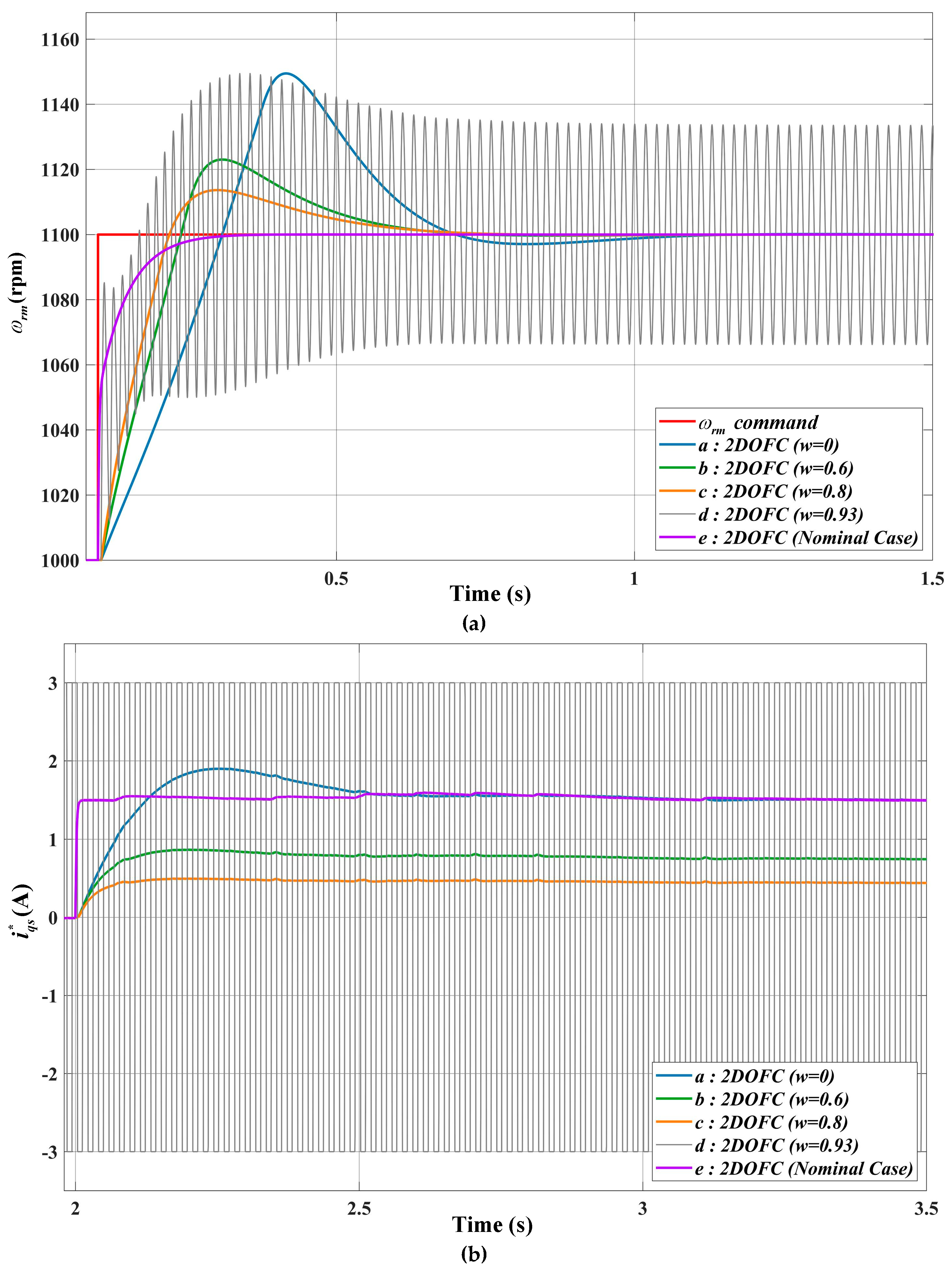

3.4. Selection of Variable Weighting Factor Characteristics for Induction Motor Drive System

3.5. Procedures of EFT-Based Dynamic Adjustment on Weighting Factors

4. Simulation Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yuze, W.; Wei, Z.; Chengliu, A.; Kai, W.; Haifeng, W. The Cooperative Control of Speed of Underwater Driving Motor Based on Fuzzy PI Control. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Electrical Machines and Systems (ICEMS), Hamamatsu, Japan, 24–27 November 2020; pp. 647–651. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.; Li, Y.; Shi, L.; Fan, M.; Kong, G.; Liu, J. Robust Two-Degree-of-Freedom Sliding Mode Speed Control for Segmented Linear Motors. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Electrical Machines and Systems (ICEMS), Zhuhai, China, 05–08 November 2023; pp. 280–285. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, K.-H.; Li, J.-Y. An Intelligent Controller Based on Extension Theory for Batteries Charging and Discharging Control. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falconi, F.; Capitaneanu, S.; Guillard, H.; Raïssi, T. A Novel Robust Control Strategy for Industrial Systems with Time Delay. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Control and Fault-Tolerant Systems (SysTol), Saint-Raphael, France, 29 September–01 October 2021; pp. 372–377. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, K.-H.; Chang, L.-Y.; Hung, C.-Y. Design and Control of Brushless DC Motor Drives for Refrigerated Cabinets. Energies 2022, 15, 3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, O.E.; Kucher, E.S. Synthesis of Induction Motor Adaptive Field-Oriented Control System with the Method of Signal-Adaptive Inverse Model. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference of Young Specialists on Micro/Nanotechnologies and Electron Devices (EDM), Chemal, Russia, 29 June–03 July 2020; pp. 470–474. [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke, C.J.; Qasim, M.M.; Overlin, M.R.; Kirtley, J.L. A Geometric Interpretation of Reference Frames and Transformations: dq0, Clarke, and Park. IEEE Trans. Energy Conv. 2019, 34, 2070–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-H. AC Motor Control: The Principles of Vector Control and Direct Torque Control, 4th ed., Tonghua Books Co. Ltd., Taipei, Taiwan, 2007; pp. 33–217.

- Ye, C.-C. AC Motor Control and Simulation Technology: A Guidance on Mastering the Core Algorithms of Electric Vehicles and Variable Frequency Technology, 1st ed., Wunan Books, Taipei, Taiwan, 2023; pp. 11–151.

- Gupta, S.; George, S. ; Awate,V. In PI Controller Design and Application for SVPWM Switching Technique Based FOC of PMSM, In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Trends in Electrical, Electronics, Bangalore, India, 23–24 August 2023, and Computer Engineering (TEECCON); pp. 172–177.

- Vemparala, R.R.B.; Titus, J. Performance Evaluation of an Si+SiC Based Hybrid VSI Using a Modified Space Vector Switching Pattern in a Grid Connected Inverter Application. In Proceedings of the 48th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Brussels, Belgium, 17–20 October 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Tapia-Olvera, R.; Beltran-Carbajal, F.; Aguilar-Mejia, O.; Valderrabano-Gonzalez, A. An Adaptive Speed Control Approach for DC Shunt Motors. Energies 2016, 9, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiev, Z.; Trushev, I.; Chervenkov, A. Laplace Transform Method to Transient Analysis in Magnetically Coupled Electrical Circuits. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference on Computer Science (COMSCI), Sozopol, Bulgaria, 18–20 September 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.; Cao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yan, Y.; Shi, T.; Xia, C. Speed Controller Design for Electric Drives Based on Decoupling Two-Degree-of-Freedom Control Structure. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 38, 15996–16009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, G.-J.; Choi, J.-W. Rotor Flux Estimator Design with Offset Extractor for Sensorless-driven Induction Motors. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 4497–4510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indriawati, K.; Widjiantoro, B.L.; Rachman, N.R. Disturbance Observer-based Speed Estimator for Controlling Speed Sensorless Induction Motor. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Seminar on Research of Information Technology and Intelligent Systems (ISRITI), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 10–11 December 2020; pp. 301–305. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, R.-S. A Variable Weighting Robust 2DOF Speed Controller for Induction Motor, National Tsinghua University, Taiwan, Master thesis, 1999.

- Chao, K.-H.; Liaw, C.-M. Fuzzy Robust Speed Controller for Detuned Field-orientated Induction Motor Drive. IEE Proceedings - Electric Power Appl. 2000, 147, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Li, Q.; Su, J.; Yan, L. Integration of Information Models for Industrial Intemet Based on Extenics. In Proceedings of the 5th IEEE International Symposium on Smart and Wireless Systems within the Conferences on Intelligent Data Acquisition and Advanced Computing Systems (IDAACS-SWS), Dortmund, Germany, 18–20 June 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Z.; Lang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Xing, S. Comprehensive Evaluation of Emergency Situation after Collisions at Sea Based on Extenics. In Proceedings of the 4th IEEE Advanced Information Management, Communicates, Chongqing, China, 18–20 June 2021, Electronic and Automation Control Conference (IMCEC); pp. 2042–2048.

| Compared item | Cantor set | Fuzzy set | Extendable fuzzy set |

| Research objects | Data variables | Linguistic variables | Contradictory problems |

| Model | Mathematics model | Fuzzy mathematics model | Matter-element model |

| Descriptive function | Transfer function | Membership function | Correlation function |

| Descriptive property | Precision | Ambiguity | Extension |

| Range of set | {0,1} | [0,1] | (-∞, ∞) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).