Submitted:

20 July 2024

Posted:

24 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

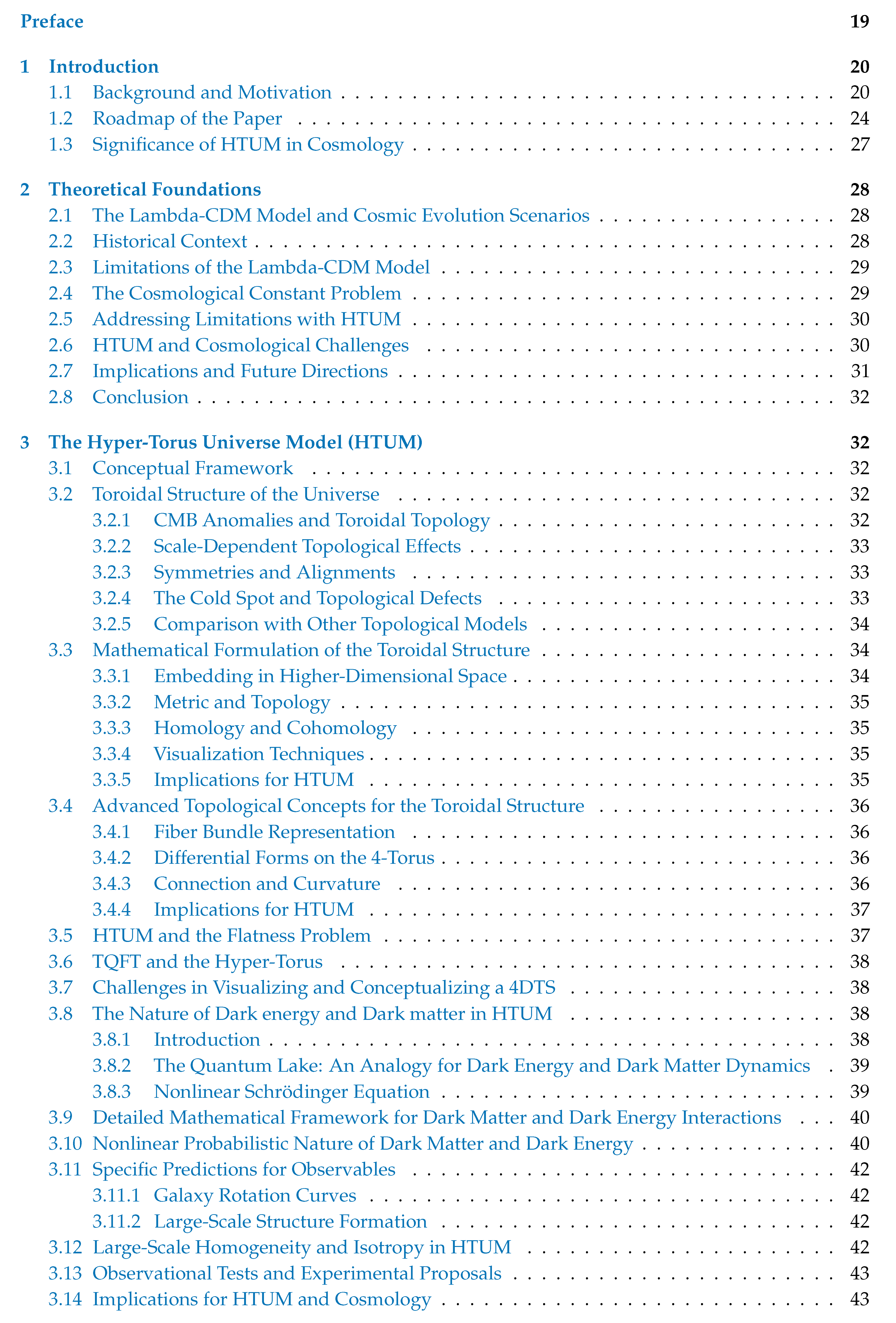

Preface

On the Scope and Structure of This Manuscript

- Unification: HTUM’s core principle of unity demands a holistic treatment that encompasses a wide range of physical phenomena, from quantum mechanics to cosmology. This manuscript aims to present a cohesive picture of how these diverse areas interconnect within the HTUM framework.

- Mathematical rigor: To fully develop HTUM’s theoretical foundations, we include detailed mathematical formulations, including a complete theory axiomatization. This level of rigor is crucial for establishing HTUM as a robust and testable scientific model.

- Interdisciplinary implications: HTUM’s unique perspective has significant implications for various fields, including particle physics, quantum gravity, and cosmology. Each area requires a thorough examination to elucidate HTUM’s potential contributions.

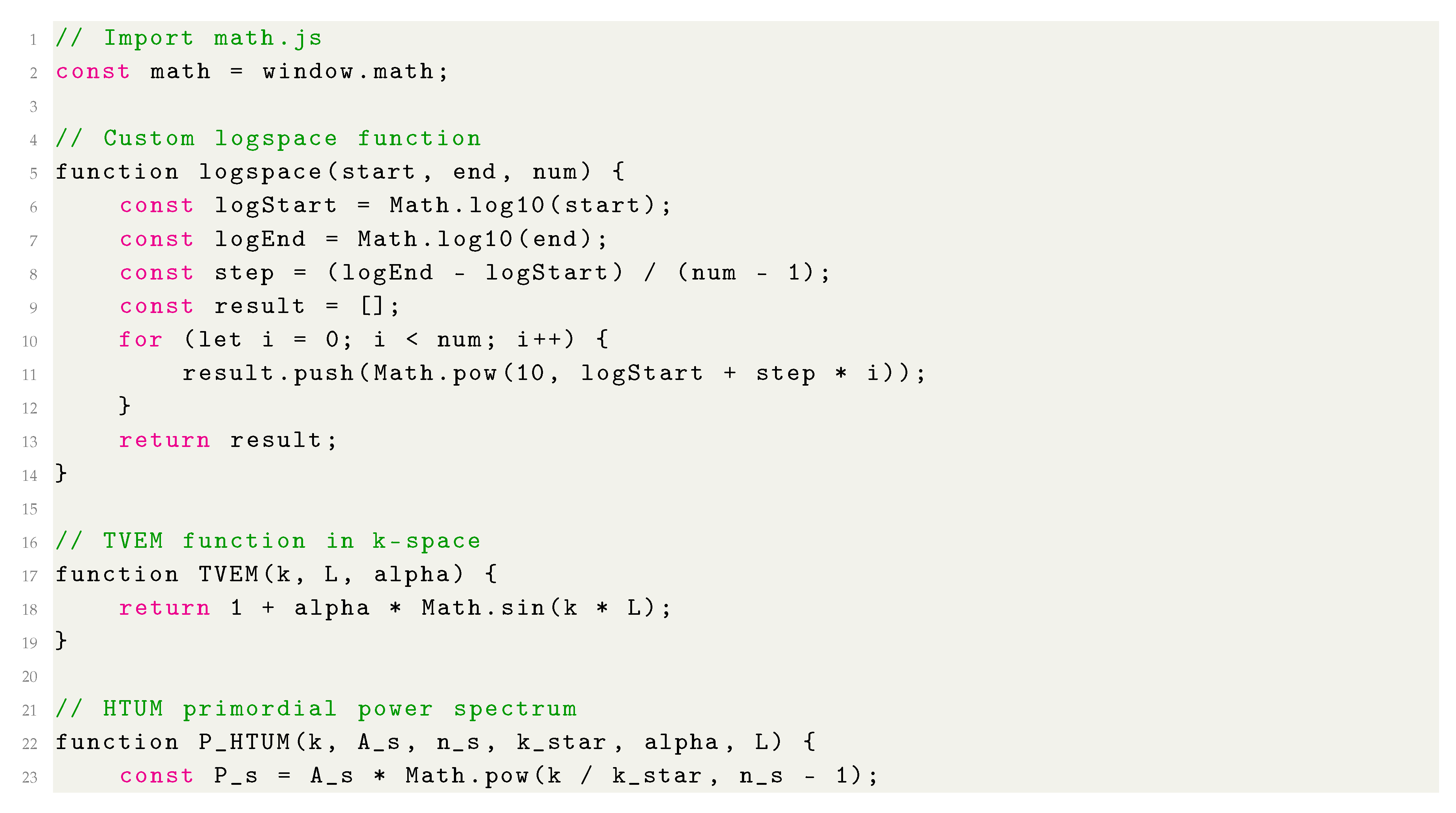

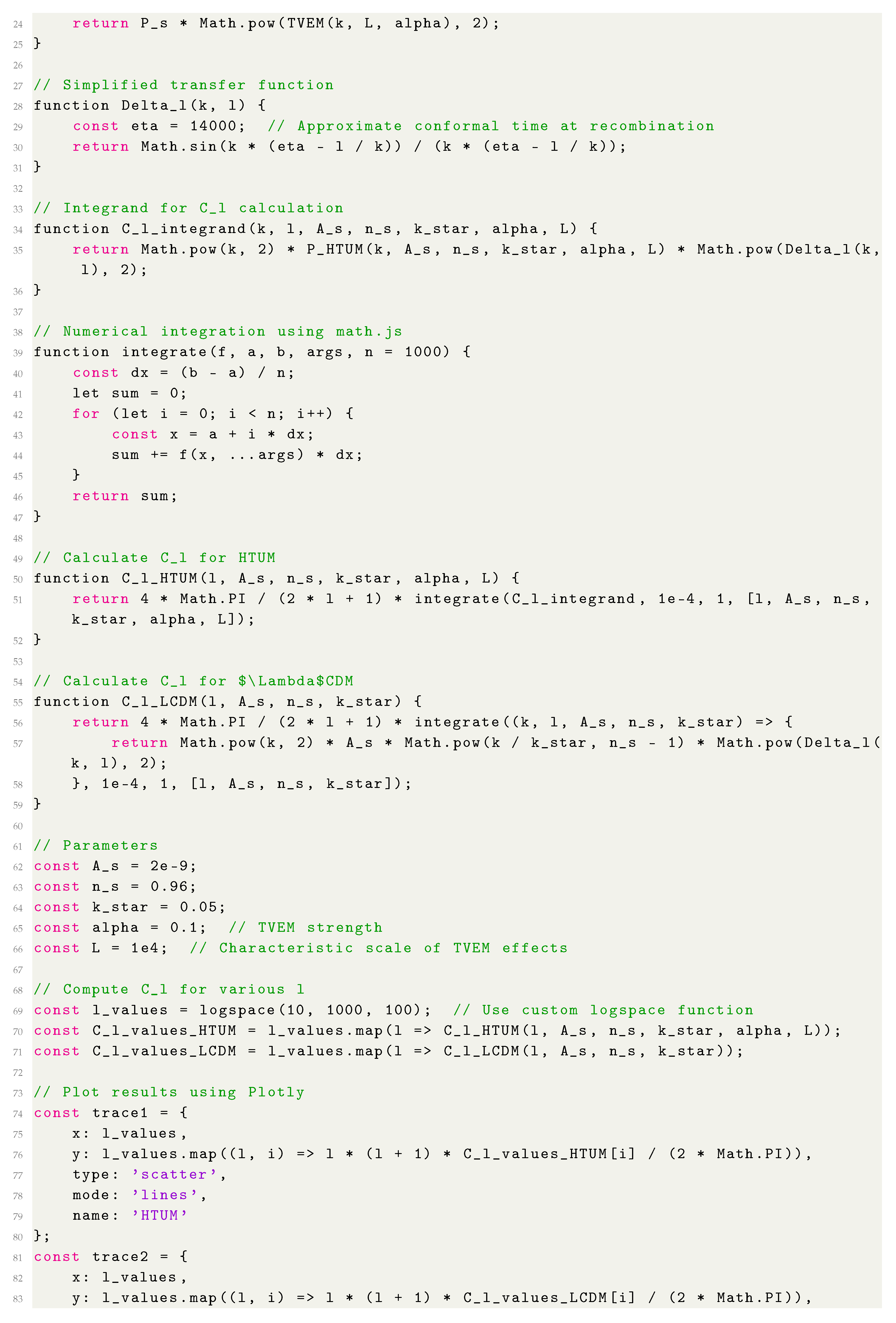

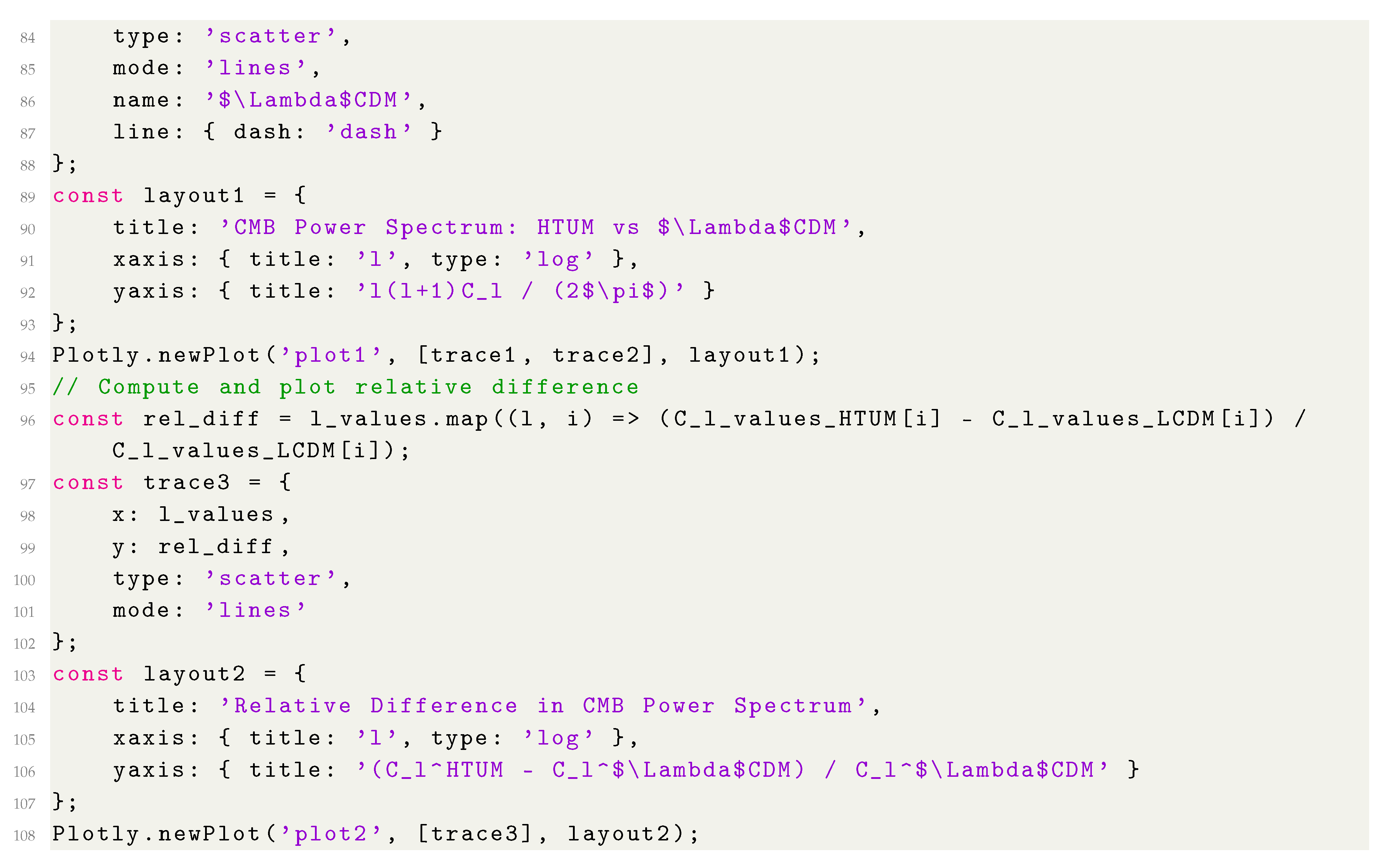

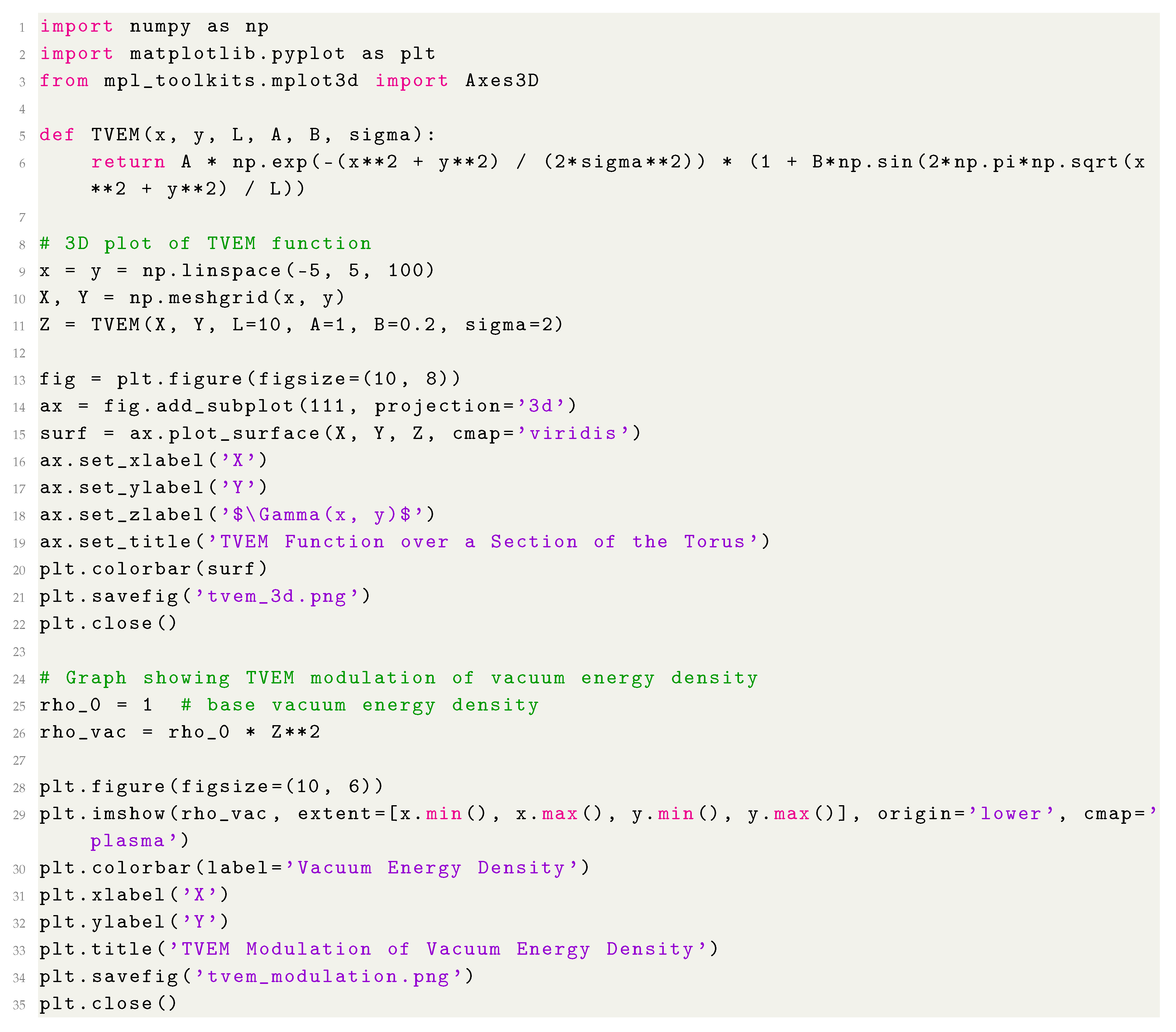

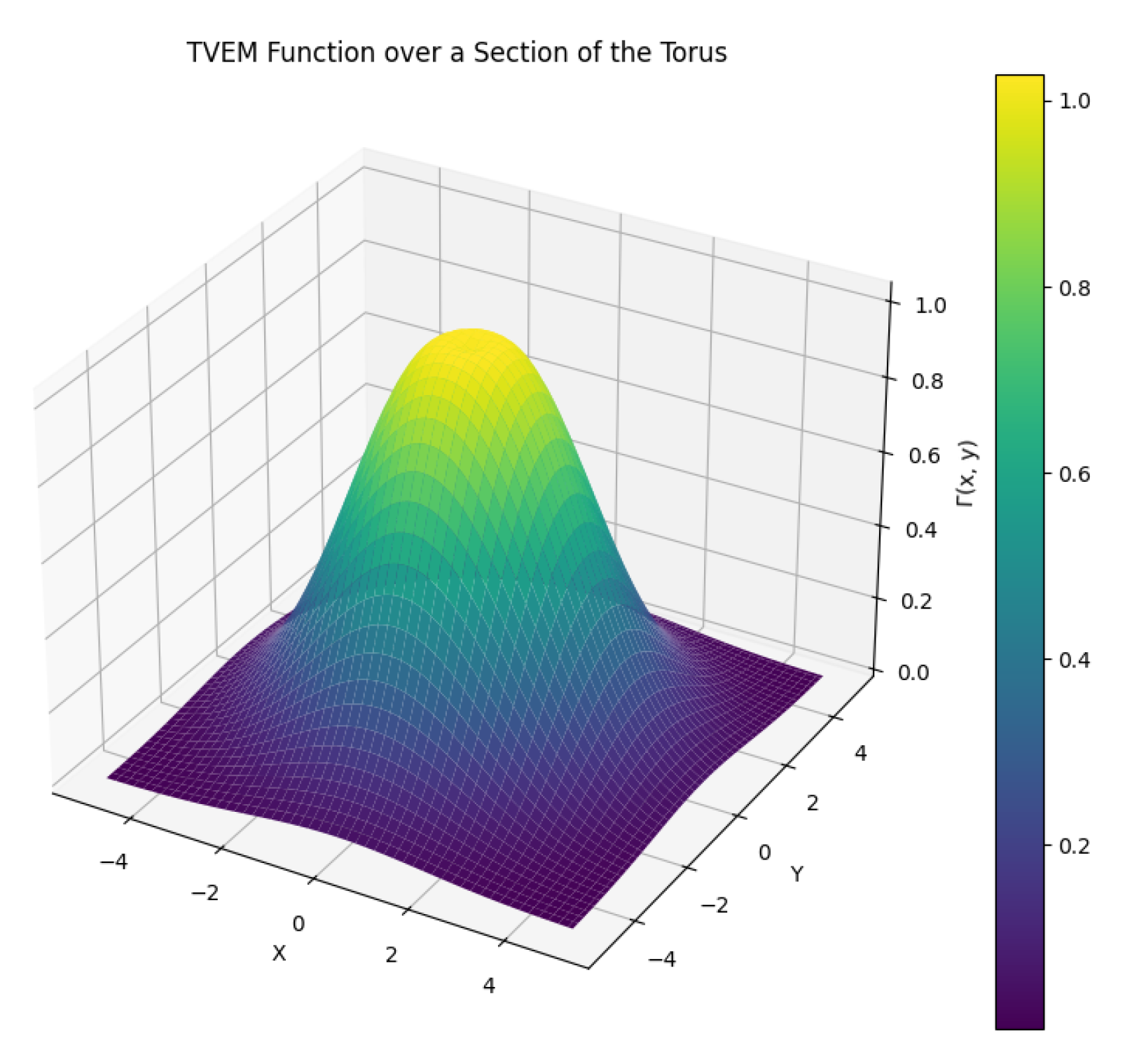

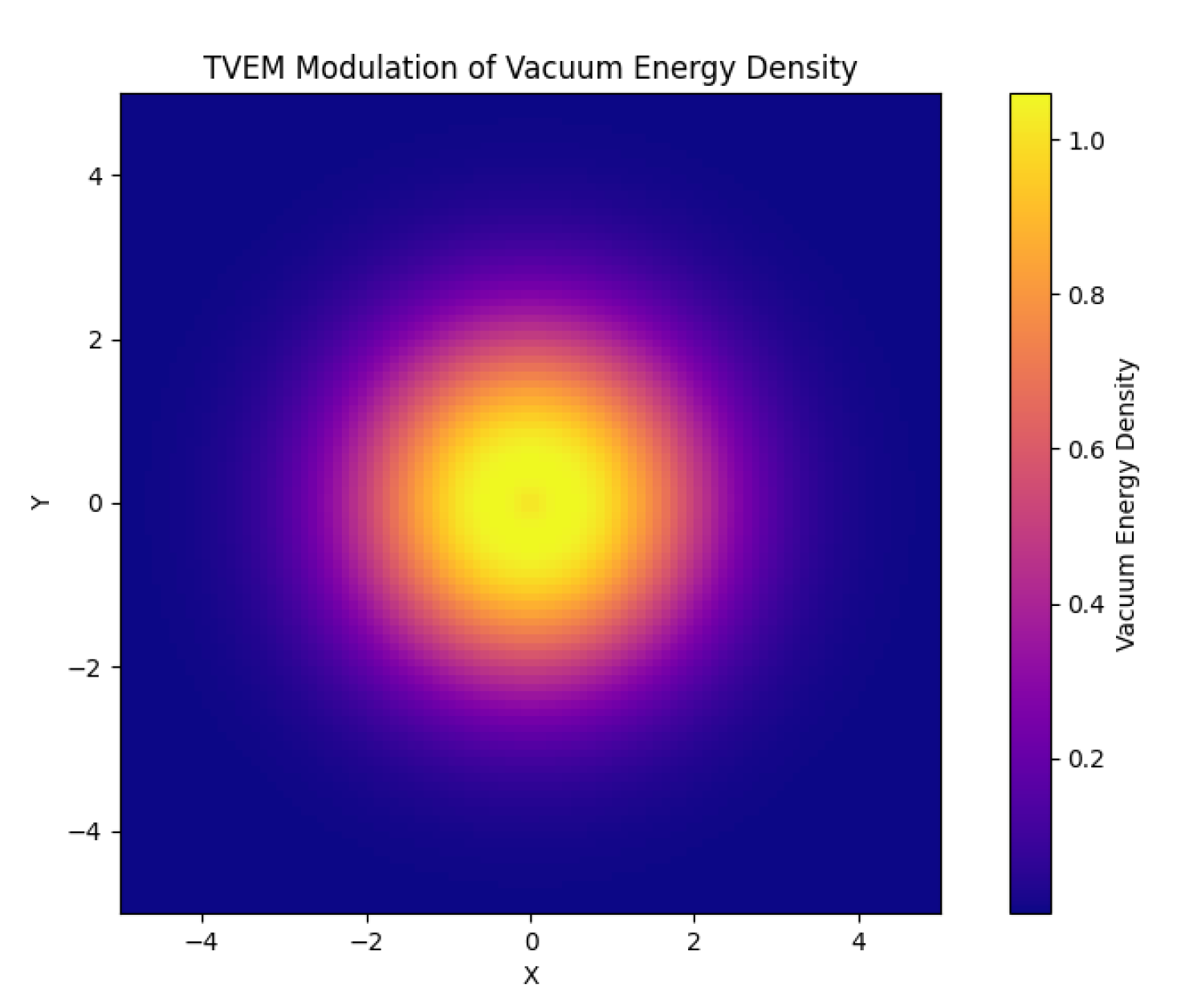

- Novel concepts: Several new ideas introduced by HTUM, such as the Topological Vacuum Energy Modulator (TVEM) function, necessitate extensive explanation and exploration of their consequences.

- Comparative analysis: To contextualize HTUM within the broader landscape of theoretical physics, we provide detailed comparisons with existing theories and models.

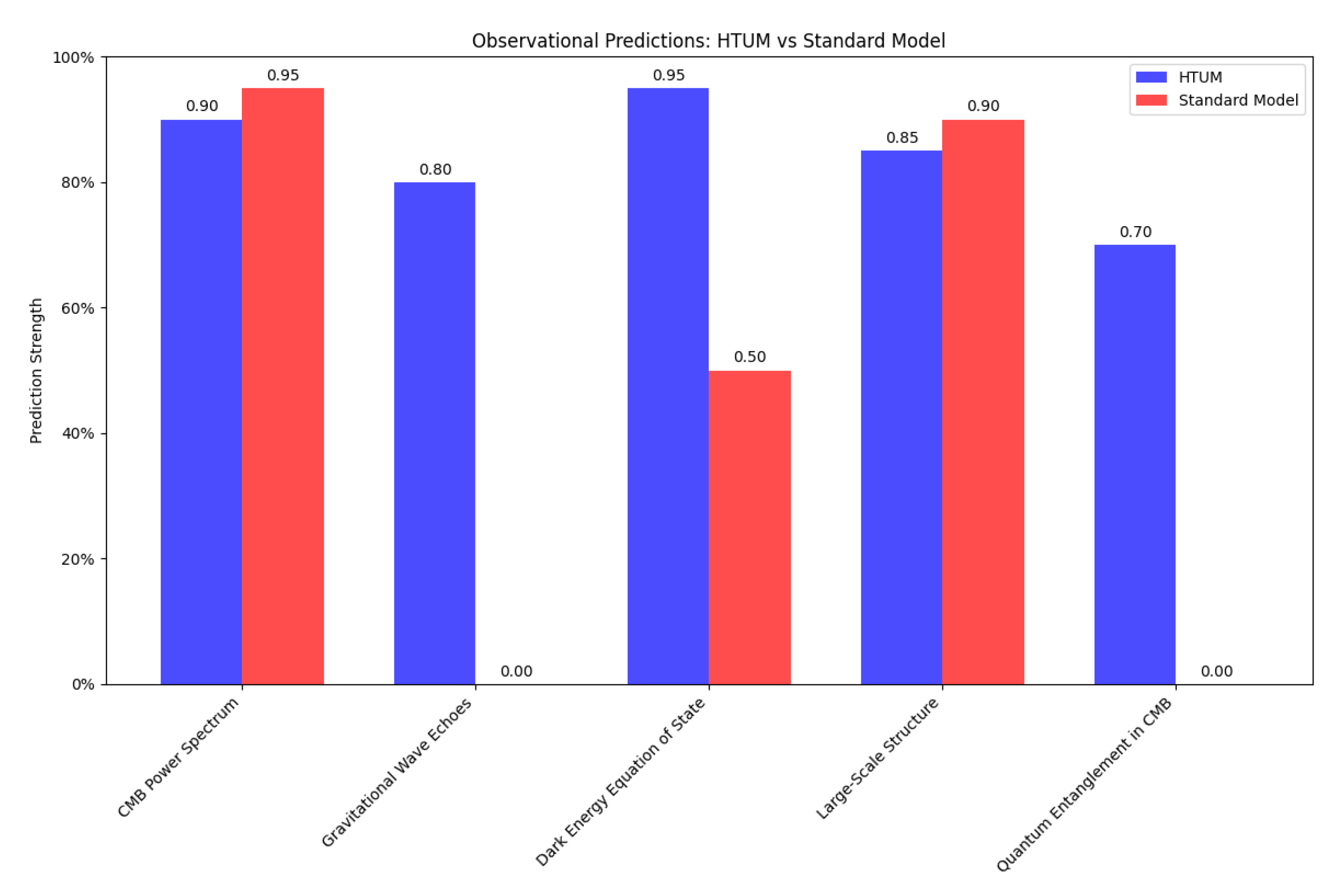

- Experimental predictions: A significant portion of this work is dedicated to deriving and explaining the observational and experimental consequences of HTUM, crucial for its empirical validation.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

- Timeless singularity: Just as objects appear frozen at a black hole’s event horizon, HTUM proposes that the entire universe exists in a state of timelessness. This concept challenges our traditional understanding of time as a linear flow and aligns with the idea of a four-dimensional structure where all moments coexist.

- Interconnectedness: The idea that all matter, regardless of when it enters the black hole, eventually reaches the same timeless state reflects HTUM’s concept of a deeply interconnected universe where all points in space and time are fundamentally linked.

- Emergence of time: The apparent flow of time for an outside observer in the black hole analogy can be likened to how HTUM views time as an emergent property arising from causal relationships within the universe’s structure.

- It provides a potential explanation for the ubiquity of black holes in the universe, suggesting they play a fundamental role in maintaining cosmic structure.

- It offers a new perspective on the information paradox, as information crossing these "walls" might be preserved within the overall structure of the universe rather than truly lost.

- It suggests a deep connection between the minor quantum scales and the most significant cosmic structures, as black holes bridge these extremes in current physics.

- It aligns with the HTUM’s cyclical nature, where matter and energy flowing through these "walls" could contribute to the universe’s self-sustaining structure.

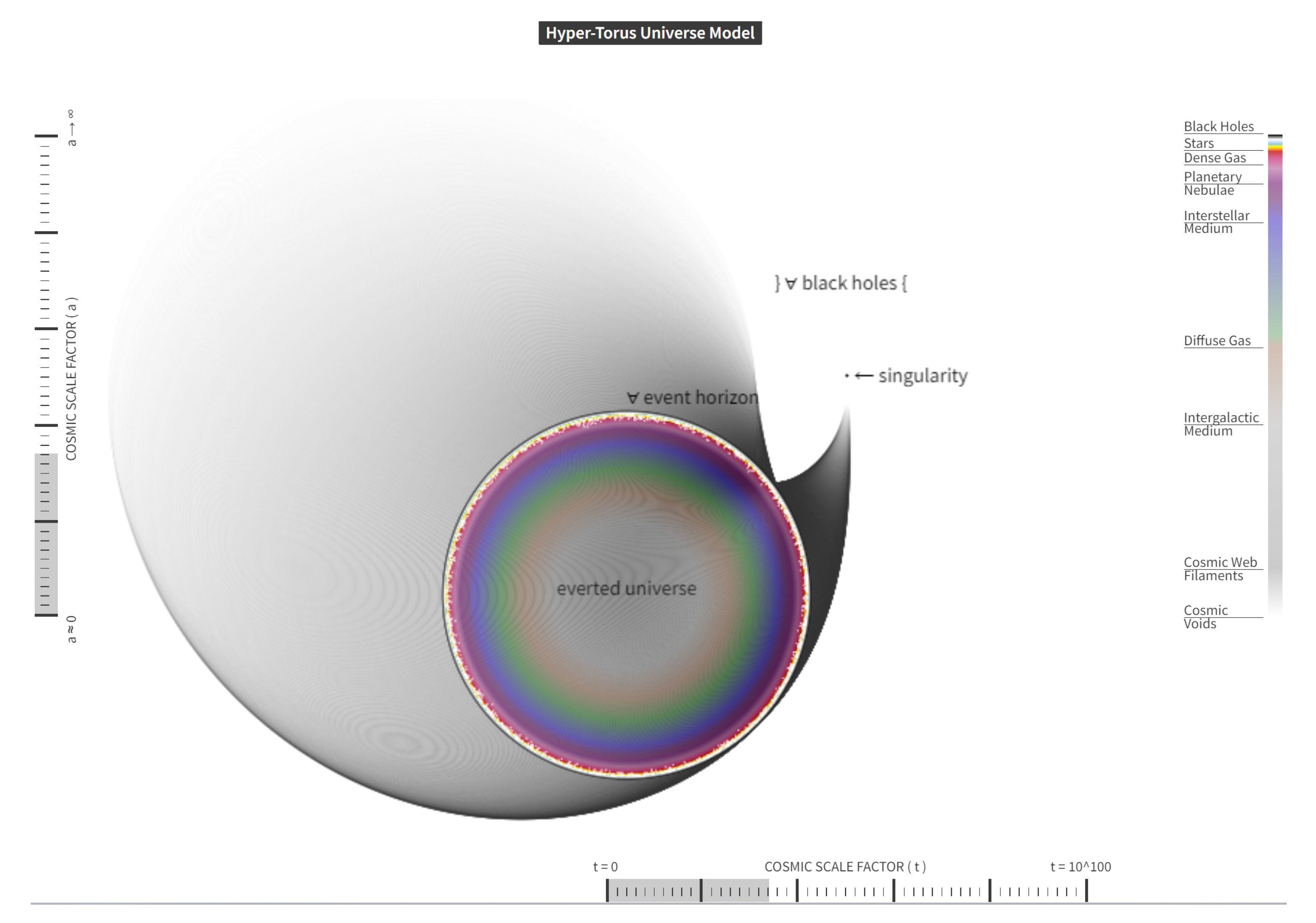

- Toroidal structure: The circular cross-section represents a slice through the 4D torus at an instance of space-time, showcasing the model’s fundamental geometry.

- Everted universe and black holes: Central to the image is the "everted universe," surrounded by a distinct event horizon. Beyond this horizon, HTUM proposes a region composed entirely of what the model considers to be a singular, unified black hole continuum. This concept illustrates HTUM’s unique perspective that all black holes are fundamentally interconnected, forming a continuous boundary of the observable universe. This approach challenges conventional views of black holes as separate entities, instead presenting them as integral parts of the universe’s toroidal structure.

- Matter distribution: Color gradients within the everted universe visualize the spatial distribution of matter across cosmic structures. The gradient progresses from the densest structures near the torus "walls" (composed entirely of event horizons) to the least dense regions at the center.

- Cosmic components: The legend identifies various components such as stars, dense gas, planetary nebulae, and interstellar medium, providing an intuitive understanding of density variations across the slice.

- Temporal representation: This static image represents a single moment in the model. The full simulation depicts Temporal evolution by animating slices moving through the 4D structure.

1.2. Roadmap of the Paper

- Section 2: Theoretical Foundations - This Section delves into the limitations of the Lambda-CDM model and provides a historical context for developing cosmological concepts, including the discovery of dark matter and dark energy. It sets the stage for understanding why a new model like HTUM is necessary.

- Section 3: The Hyper-Torus Universe Model (HTUM) - Here, we present a detailed explanation of HTUM, including the mathematical formulation of the toroidal structure and its properties. We also discuss the challenges in visualizing a four-dimensional toroidal structure (4DTS).

- Section 4: Axiomatization of HTUM: Addressing Hilbert’s Sixth Problem - This section provides a comprehensive HTUM axiomatization, significantly contributing to the model’s theoretical foundation.

- Section 5: Early Universe Evolution and Inflation in HTUM - This section delves into how HTUM addresses the early universe and cosmic inflation. It explores the transition from quantum to classical states within the HTUM framework and presents a unique perspective on inflation that arises naturally from the toroidal structure. The section demonstrates how HTUM can explain critical cosmological phenomena without requiring additional fields or mechanisms.

- Section 6: Gravity and the Collapse of the Wave Function - This Section explores the wave function’s significance in quantum mechanics and discusses the measurement problem, highlighting how HTUM addresses these issues.

- Section 7: Yang-Mills Theory and Mass Gap in HTUM - This section provides a detailed exploration of Yang-Mills theory within the HTUM framework, including its implications for particle physics and cosmology.

- Section 8: Time Dilation and Causal Processing: A Unifying Perspective - This section presents HTUM’s novel interpretation of time dilation as a manifestation of causal processing within the universe’s structure. It introduces the concept of manifold actualization latency and explores how this framework unifies gravitational and special relativistic time dilation effects. The section includes a thought experiment, the Quantum Gravity Observatory, demonstrating HTUM’s unique predictions. It also provides a comparative analysis with other time dilation interpretations, highlighting HTUM’s contributions to our understanding of time, gravity, and quantum phenomena. The section concludes by addressing practical challenges in testing these predictions and discussing future research directions.

- Section 9: Information Theory and Holography in HTUM—This section explores the implications of HTUM for information theory and holography. We discuss how the universe’s toroidal structure affects the encoding and processing of information and examine the connections between HTUM and holographic principles. The section also addresses the black hole information paradox within the HTUM framework and proposes novel approaches to quantum error correction based on the model’s unique geometry.

- Section 10: HTUM and the Computational Universe - This section explores the interpretation of HTUM as a model of a computational universe. We examine how the 4-dimensional toroidal structure (4DTS) can be viewed as a cosmic-scale quantum computer, discuss information processing within this framework, and explore the algorithmic complexity of the universe. The section also investigates quantum error correction in the toroidal structure, connections to digital physics, and the implications of viewing the universe as a vast information processing system. We discuss this computational perspective’s observational and experimental implications, providing testable predictions that could validate HTUM’s computational aspects.

- Section 11: Beyond Division: Unifying Mathematics and Cosmology - This Section examines HTUM’s implications for the foundations of mathematics, discussing the nature of mathematical truth and the role of intuition.

- Section 12: The Singularity and Quantum Entanglement - We explain quantum entanglement, its implications for singularity, and the challenges in experimentally verifying these concepts.

- Section 13: The Event Horizon and Probability - This Section focuses on the mathematical formulation of the event horizon and its properties, discussing HTUM’s implications for our understanding of black holes.

- Section 14: The Universe Observing Itself - We explore the mechanism of self-observation and its relationship to the collapse of the wave function, addressing the experimental challenges involved.

- Section 15: Consciousness and the Universe - We discuss the relationship between consciousness and quantum measurement, incorporating this relationship into HTUM and addressing experimental challenges.

- Section 16: Consciousness and the Singularity: A Unified Perspective - We propose a radical hypothesis unifying consciousness and the singularity within the HTUM framework. This section explores this unified perspective’s theoretical foundations, mathematical formulations, philosophical implications, and potential experimental tests. We also address potential criticisms and discuss future research directions in this speculative but promising area of inquiry.

- Section 17: Advanced Formalism of Consciousness in HTUM - Here, we delve deeper into the mathematical framework for integrating consciousness within HTUM. We present an enhanced formalism that describes the interface between consciousness and quantum states, propose testable predictions for consciousness-quantum interactions, and explore the implications for quantum measurement theory. This section also examines how the toroidal structure of HTUM influences conscious experience and discusses the philosophical and metaphysical consequences of this advanced formalism.

- Section 18: Relationship to Other Theories - This Section compares HTUM with other theories of quantum gravity and discusses the potential for integration with different theoretical frameworks.

- Section 19: Unification with Particle Physics - We explore how HTUM can be extended to incorporate and explain phenomena in particle physics. We discuss the potential emergence of Standard Model particles from the toroidal structure, examine predictions for high-energy particle physics, and propose a framework for unifying fundamental forces within HTUM. This section demonstrates how HTUM’s unique geometric approach could provide new insights into particles’ nature and interactions.

- Section 20: The Higgs Field in HTUM - We integrate the Higgs mechanism into the HTUM framework, providing a comprehensive analysis of its implications. We introduce novel concepts such as Toroidal Higgs Loop Helix (THLH) configurations and explore the interplay between the Higgs field and the Topological Vacuum Energy Modulator (TVEM). We examine the cosmological implications of this integration, including modified inflation dynamics and new dark matter candidates. The section also presents experimental signatures, proposes tests, and compares HTUM’s approach to other models. We conclude with a rigorous mathematical formalism, including proofs and derivations in an appendix, demonstrating HTUM’s potential to unify particle physics with quantum gravity and cosmology.

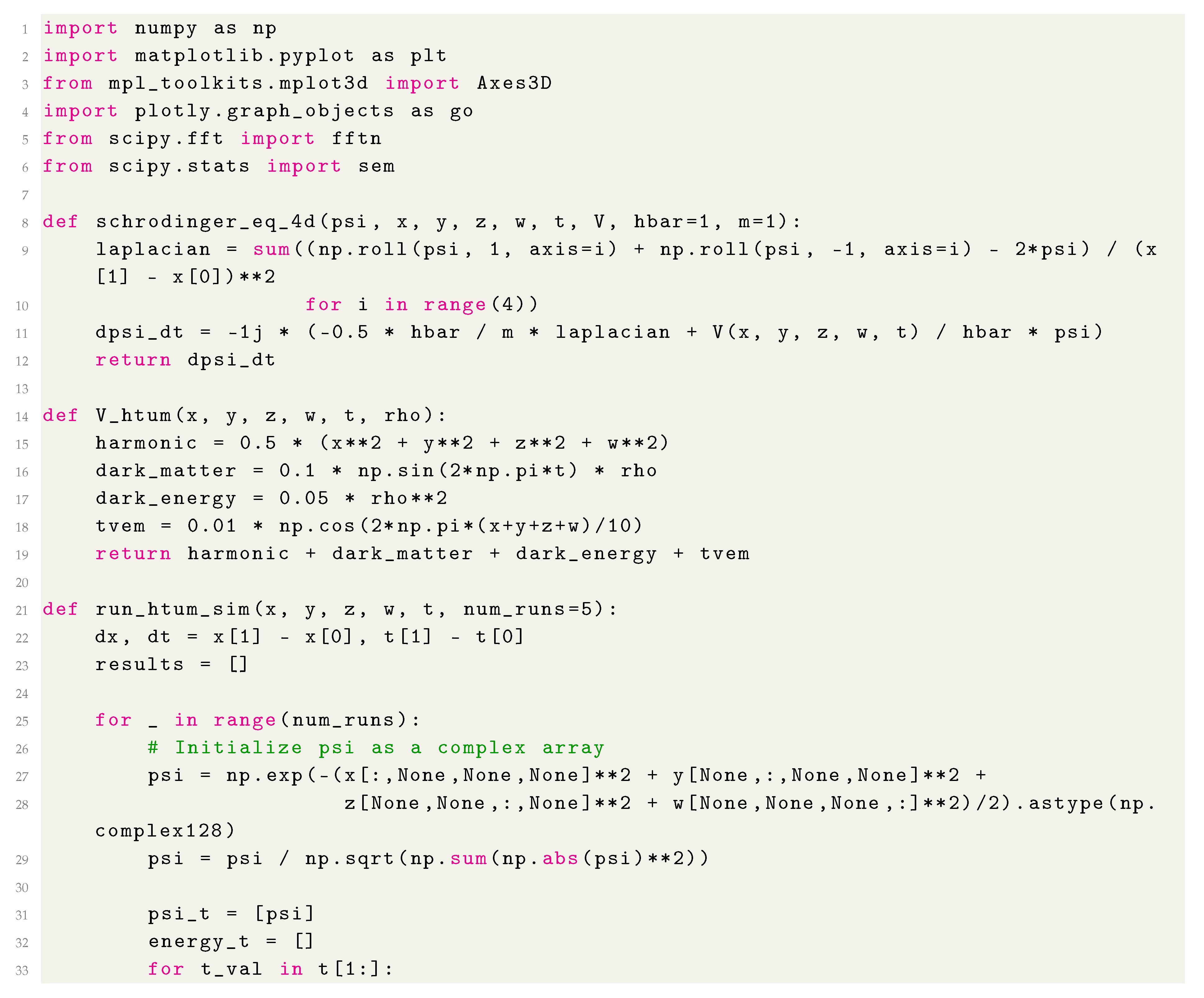

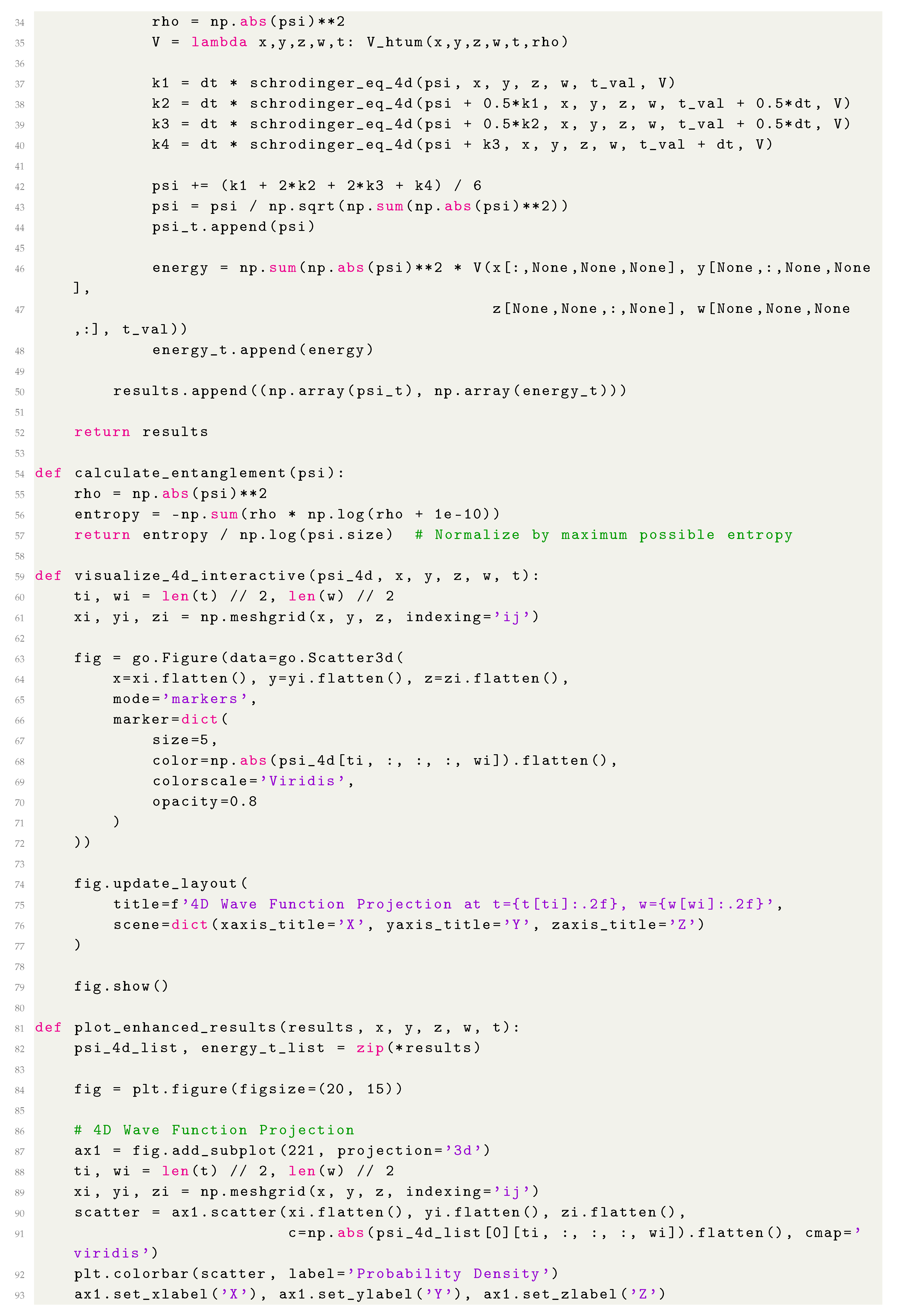

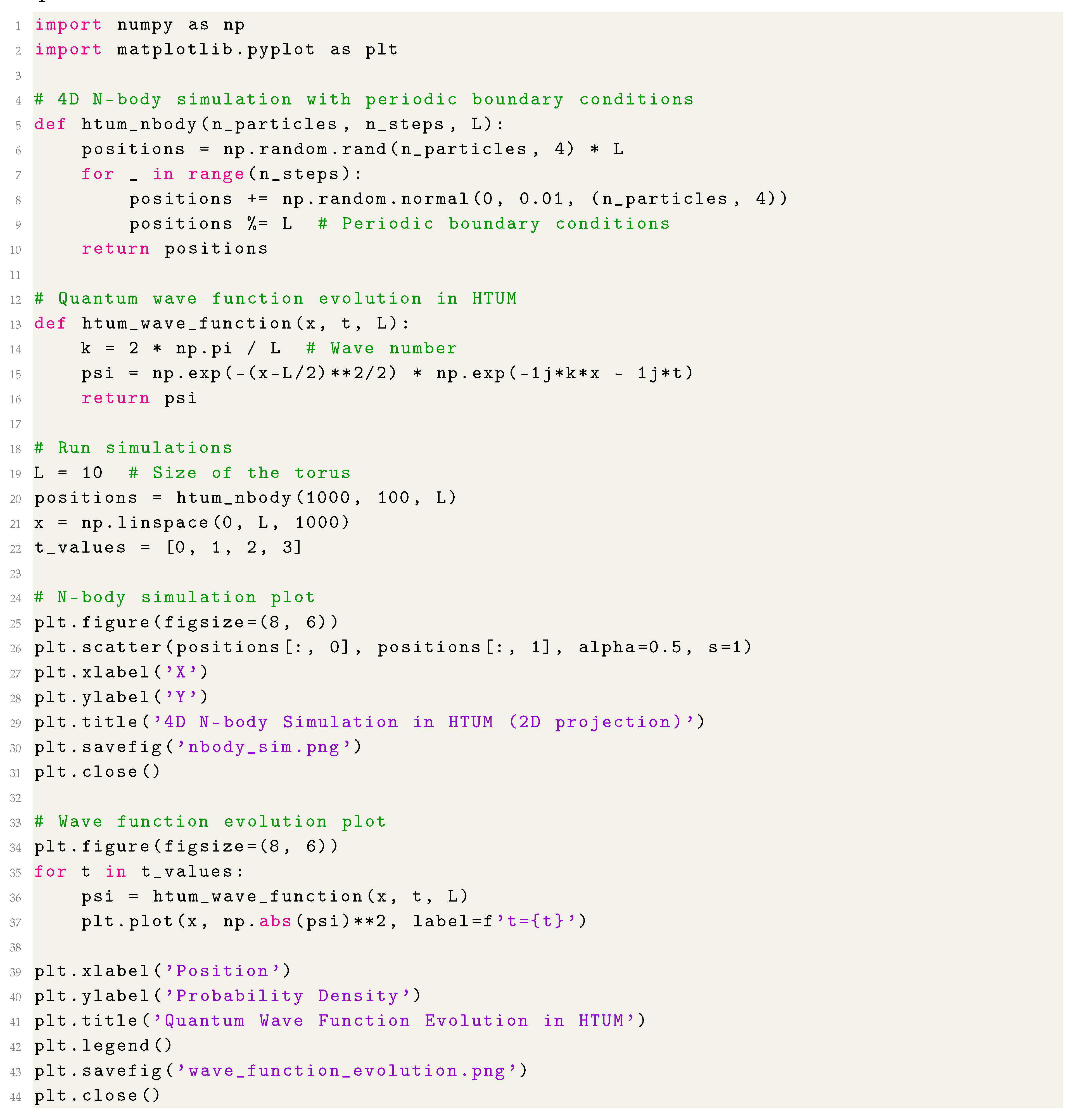

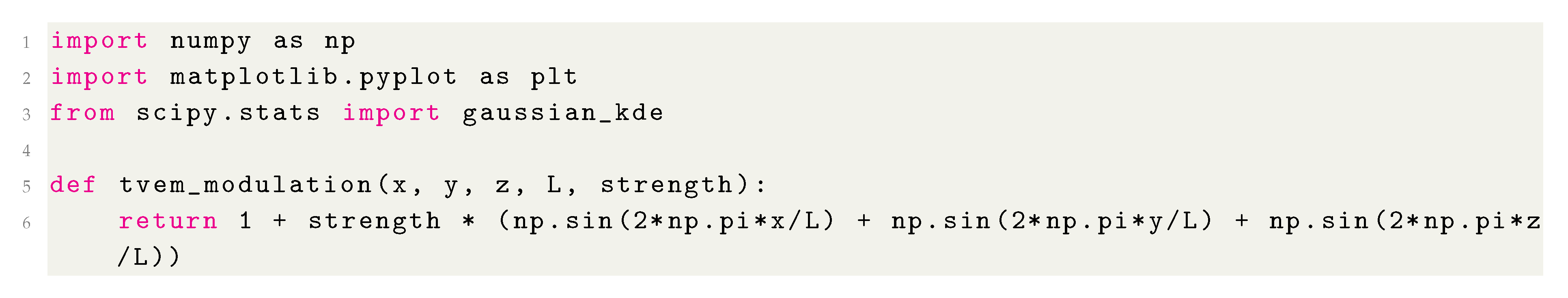

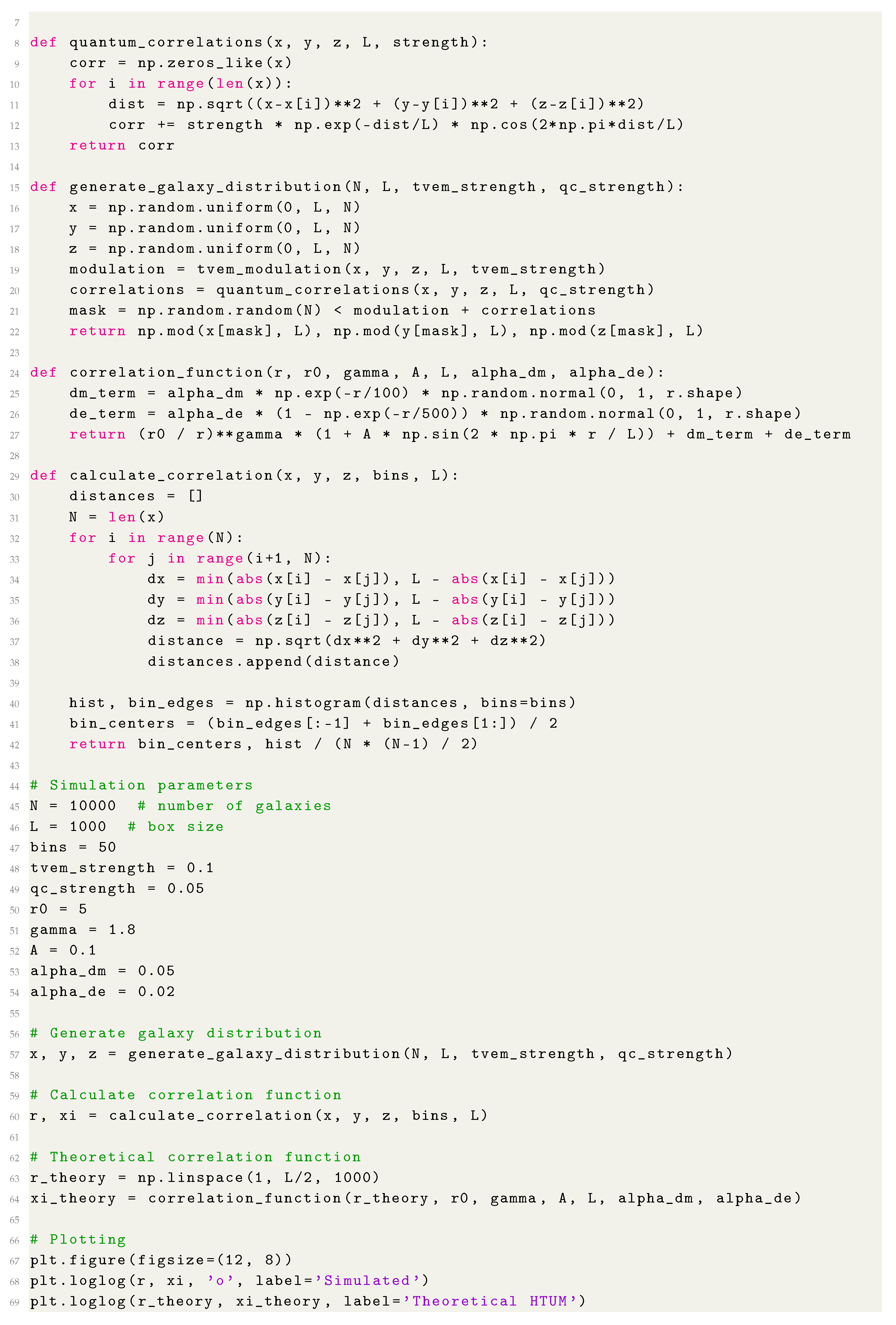

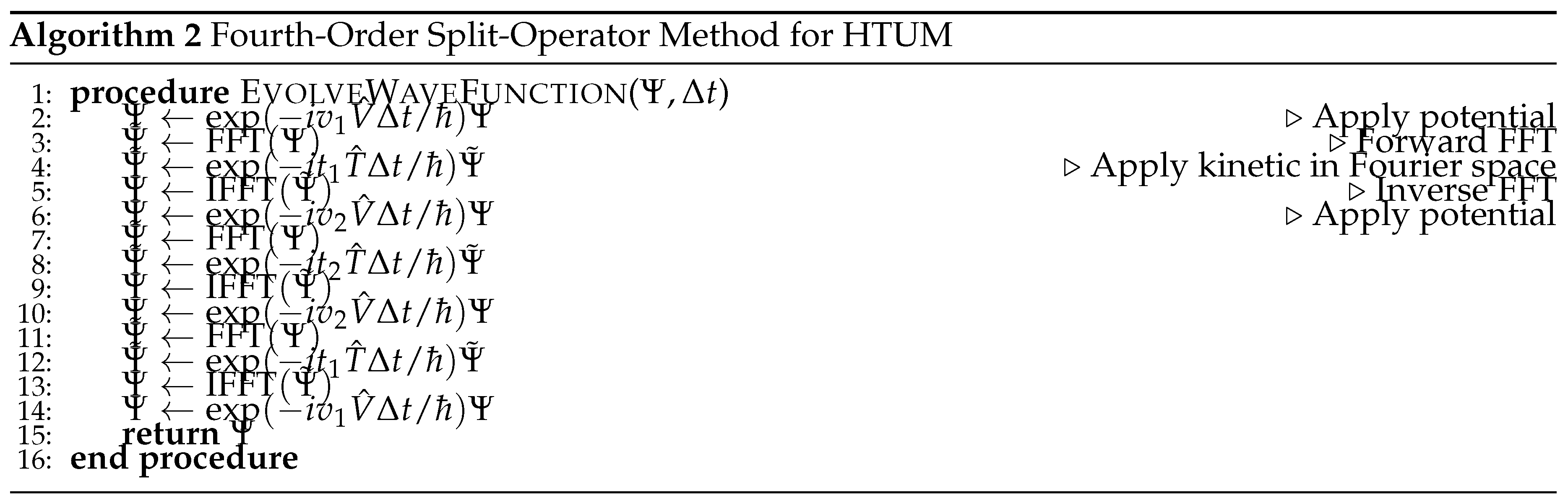

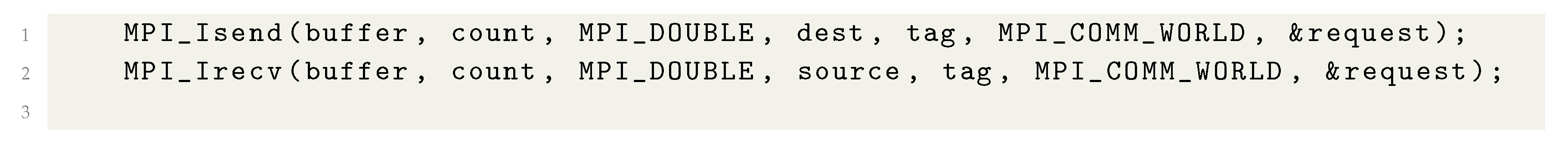

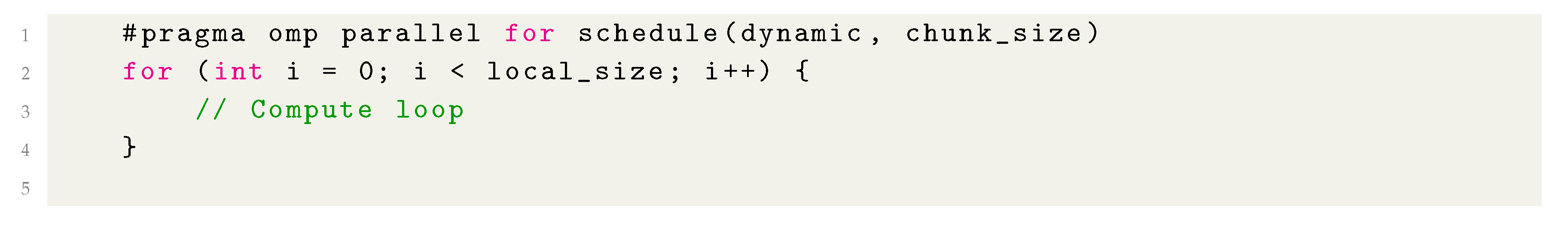

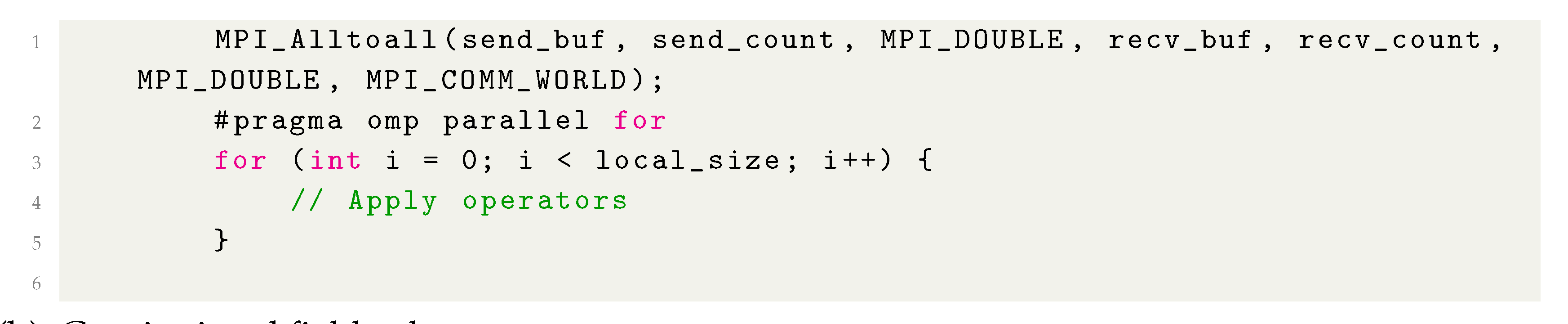

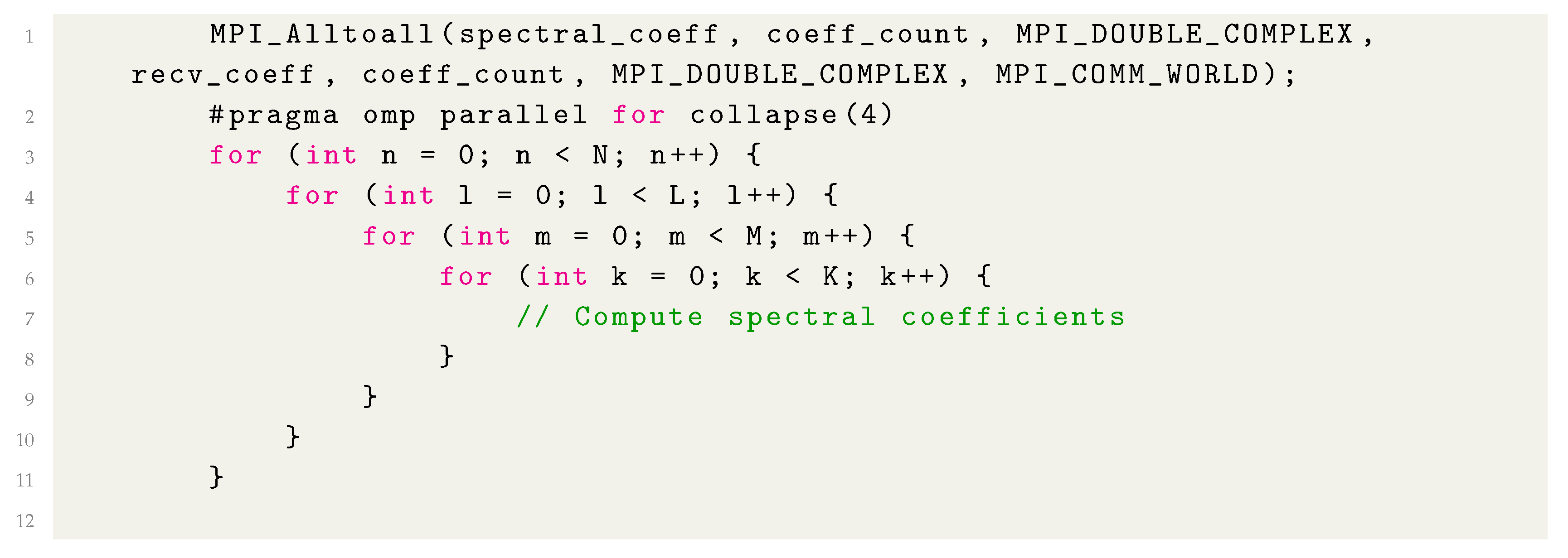

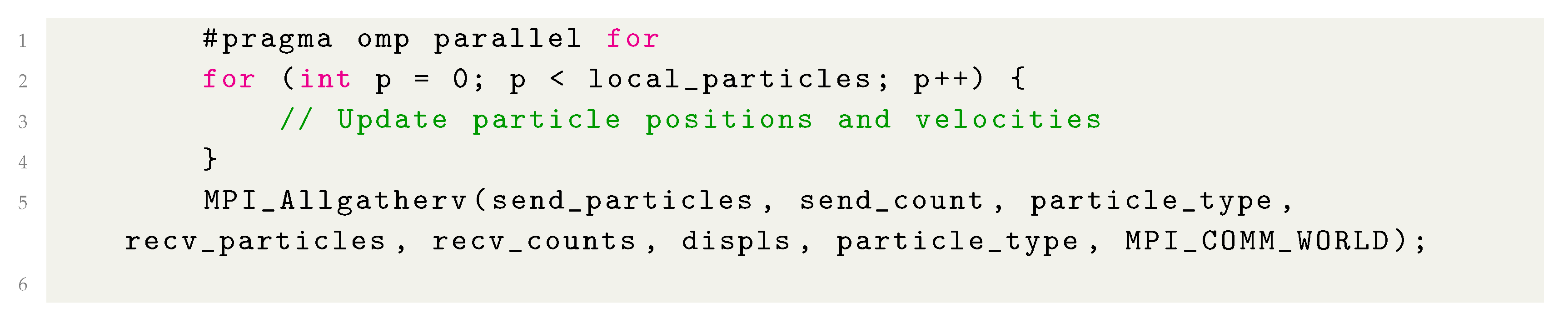

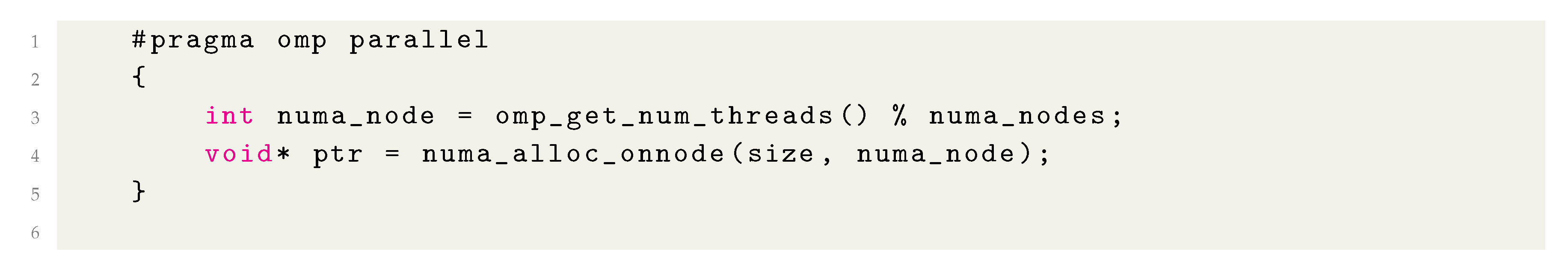

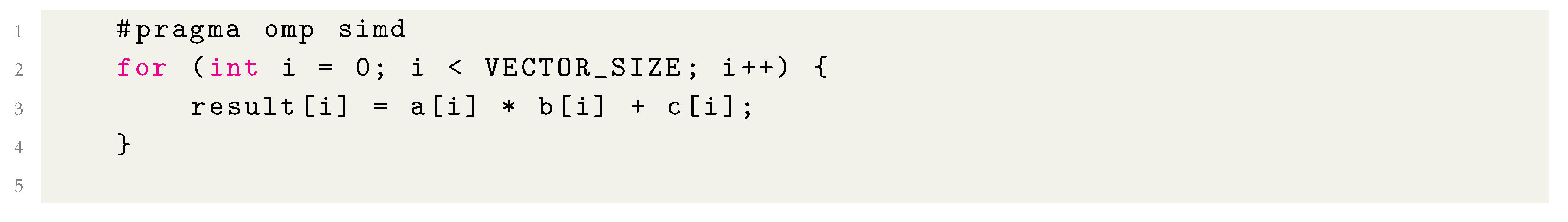

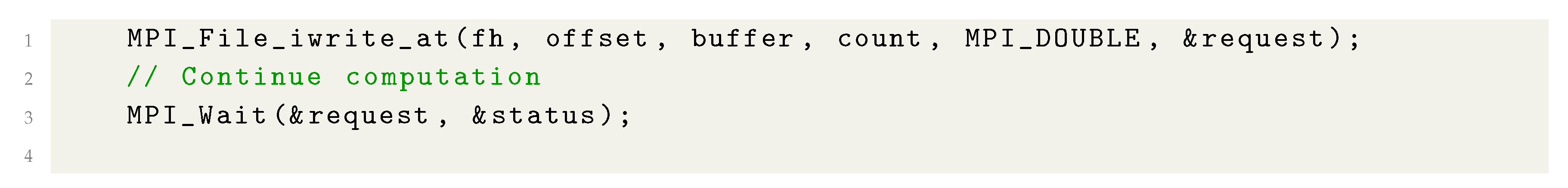

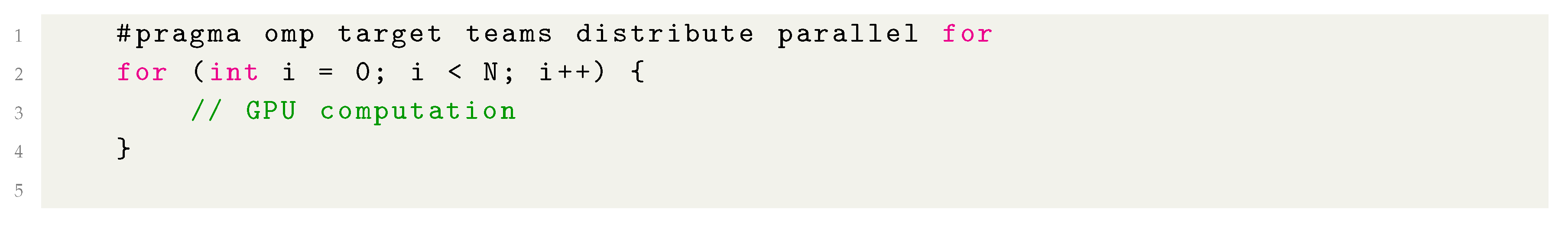

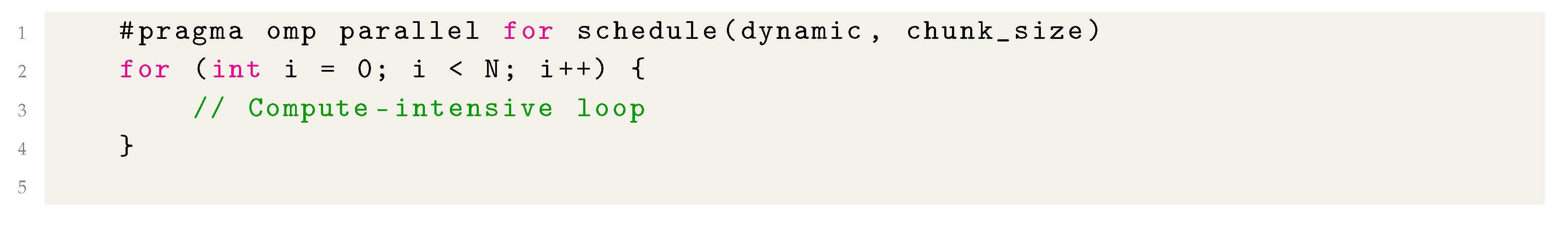

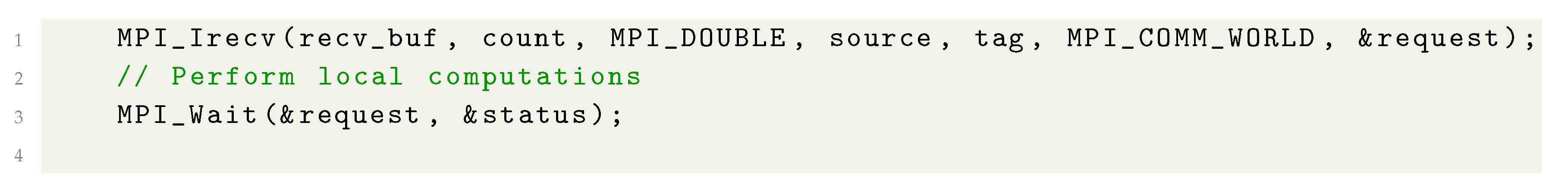

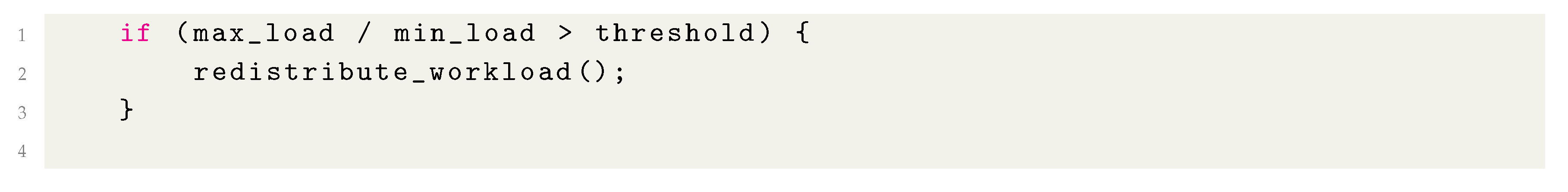

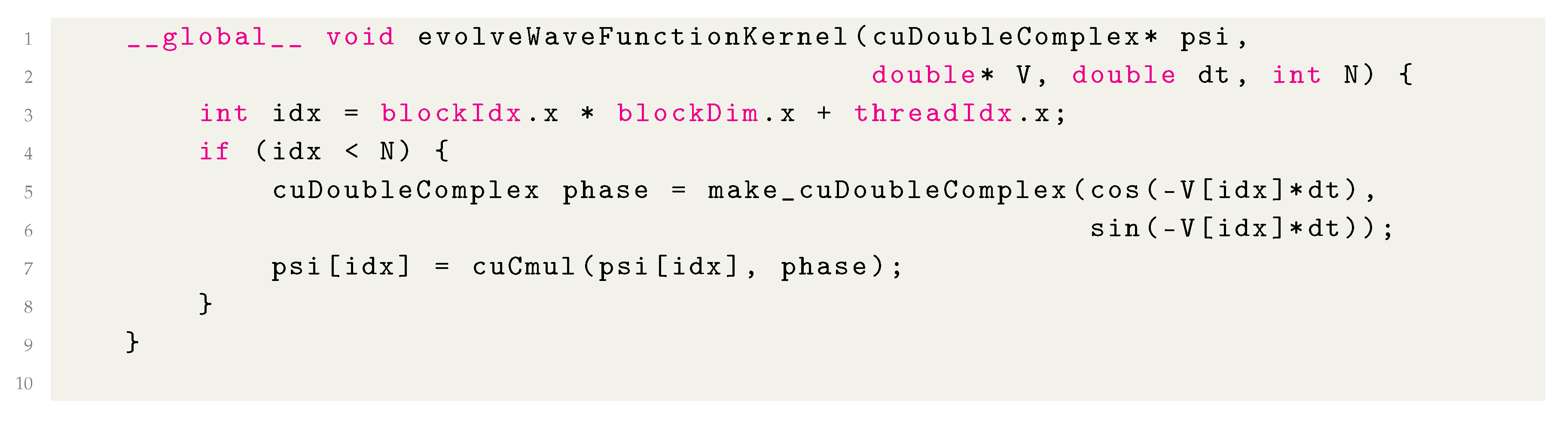

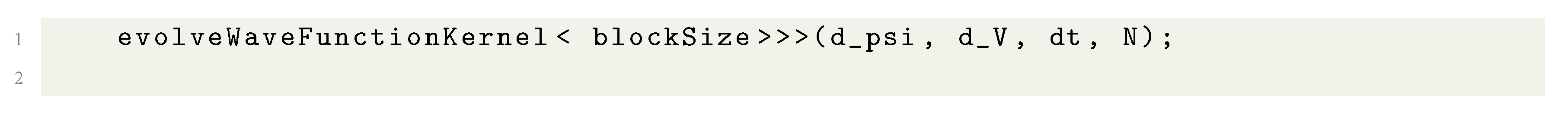

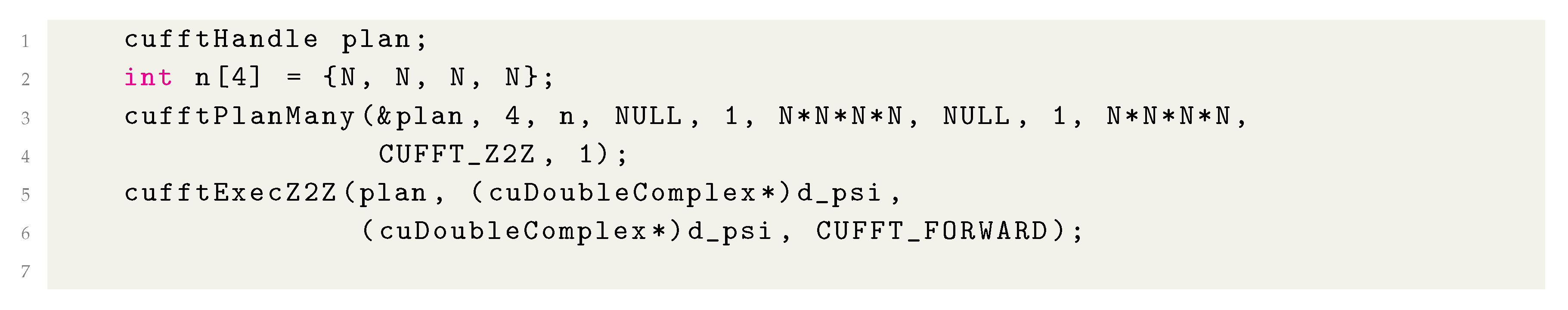

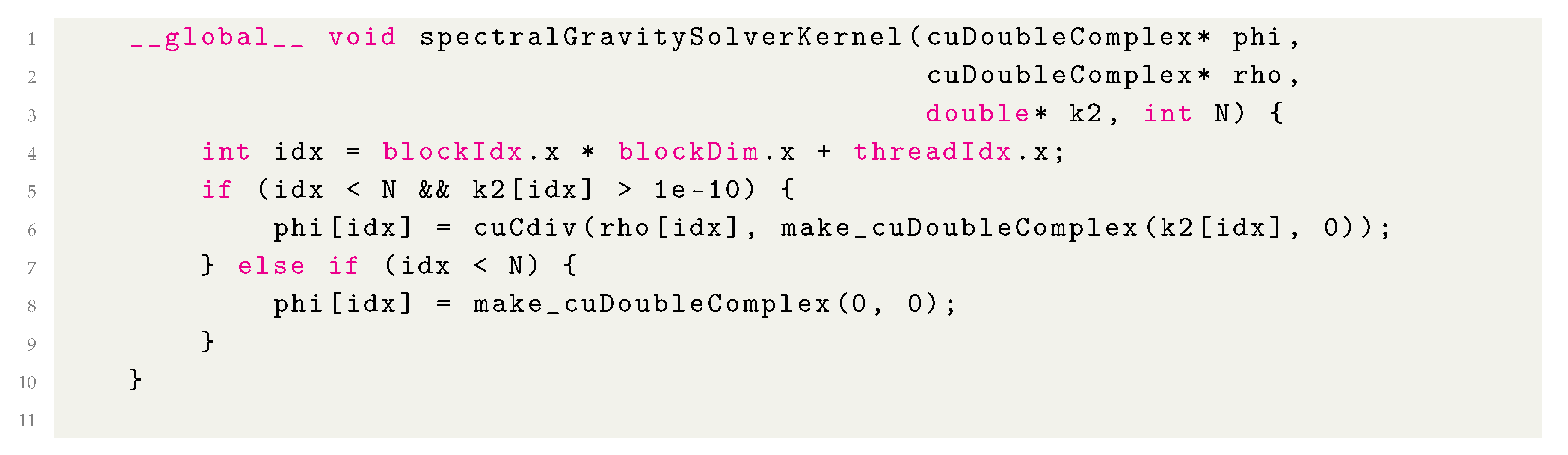

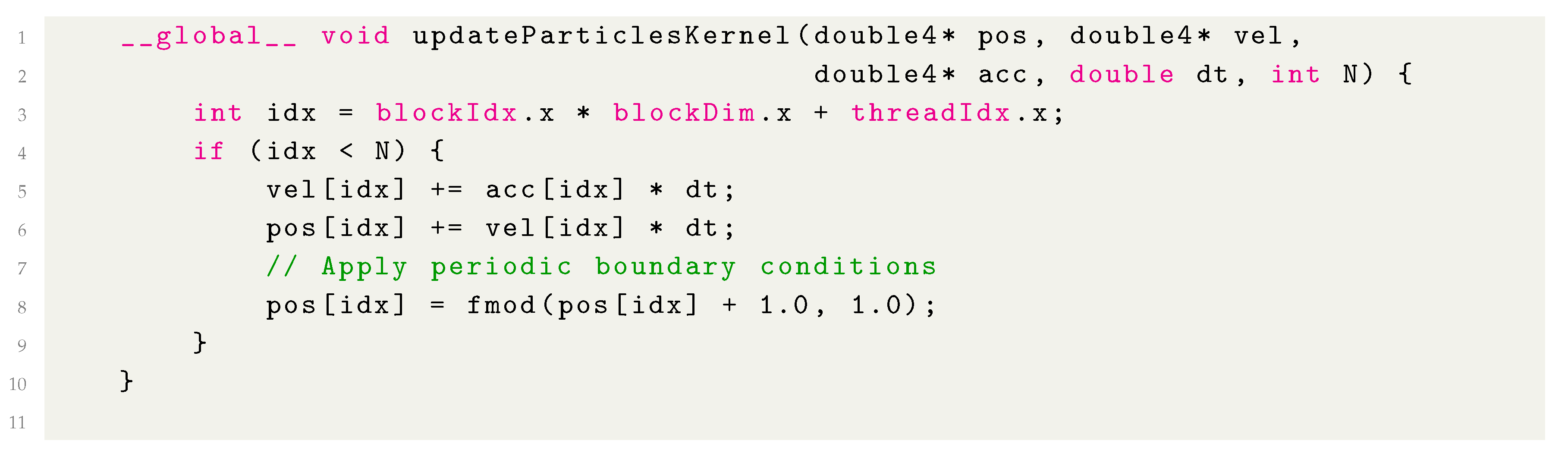

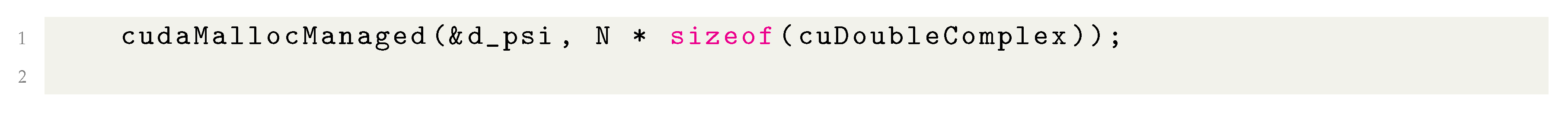

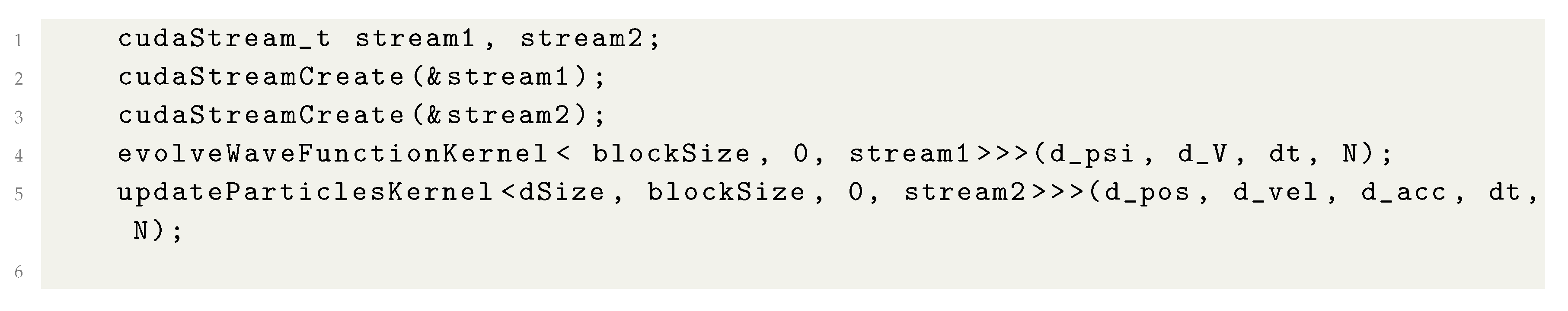

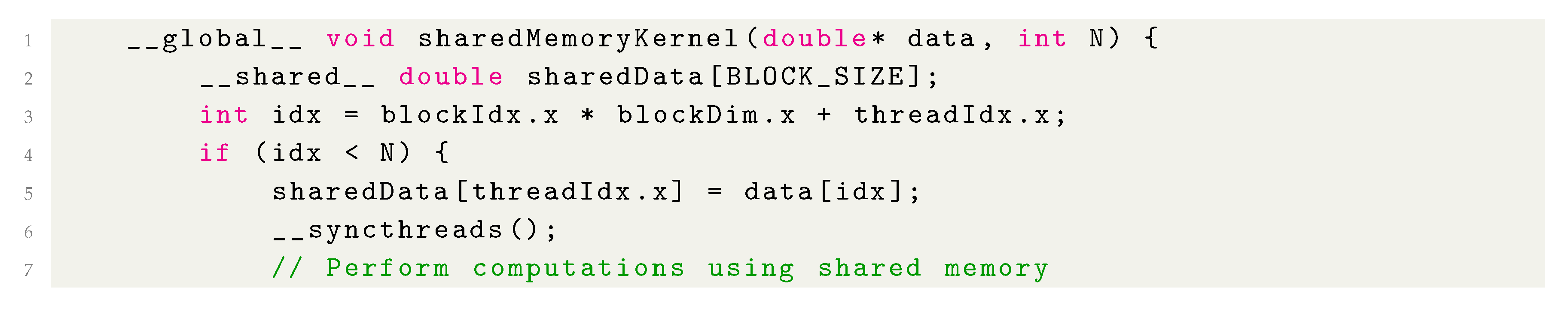

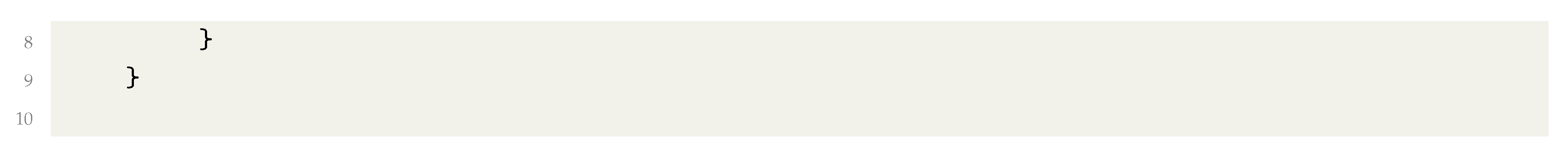

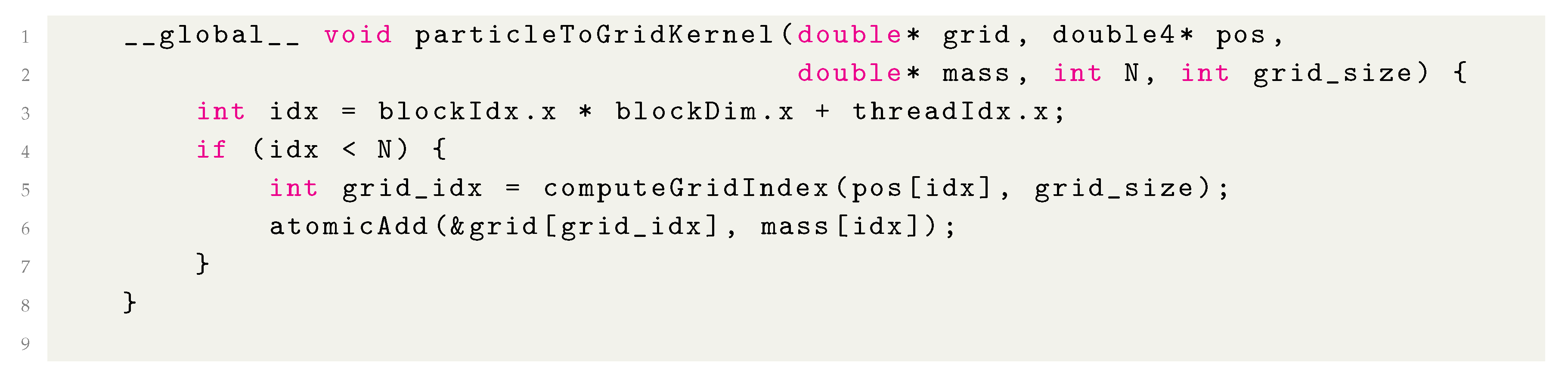

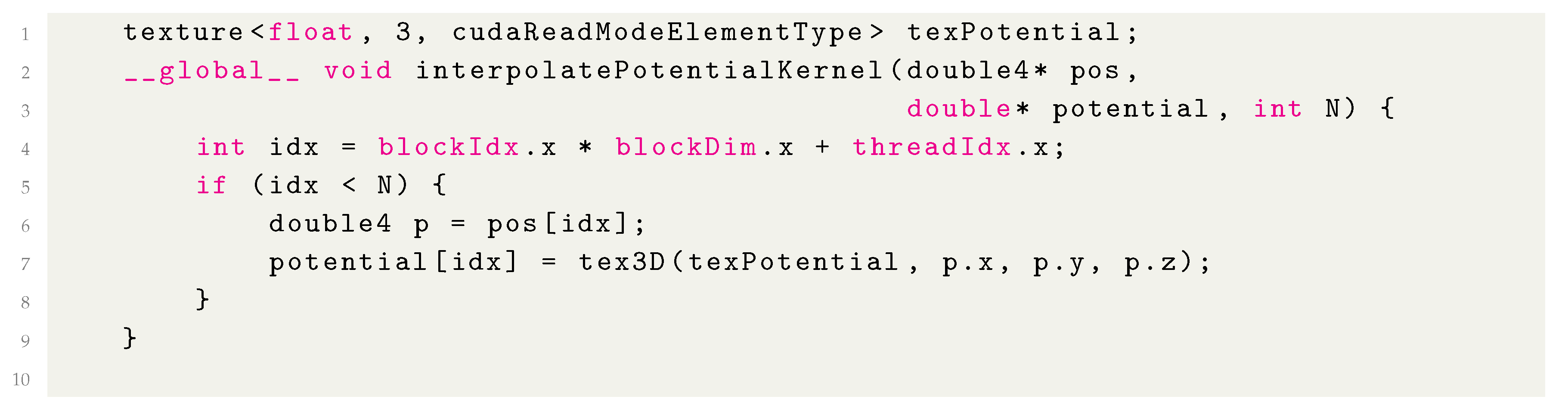

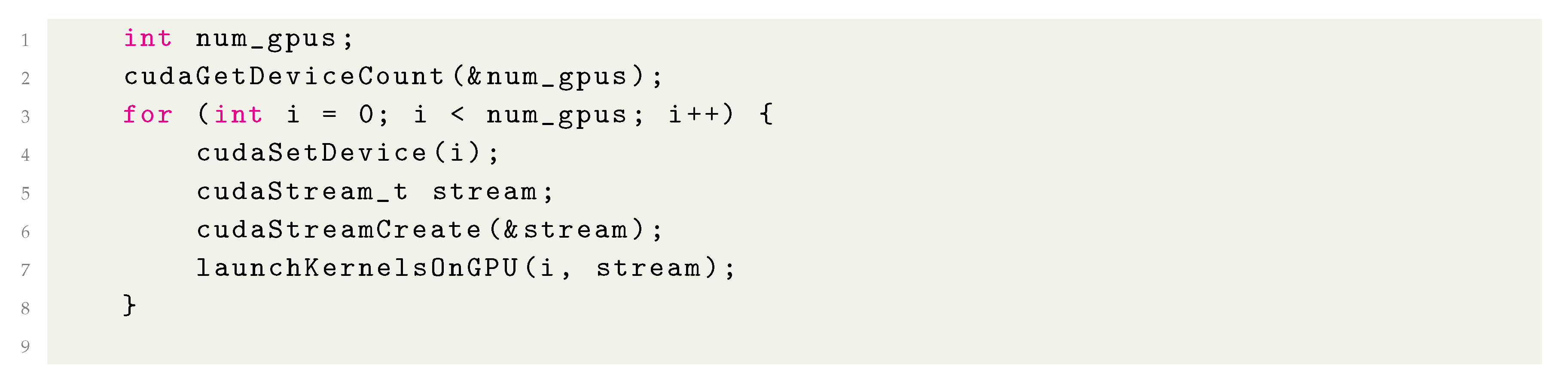

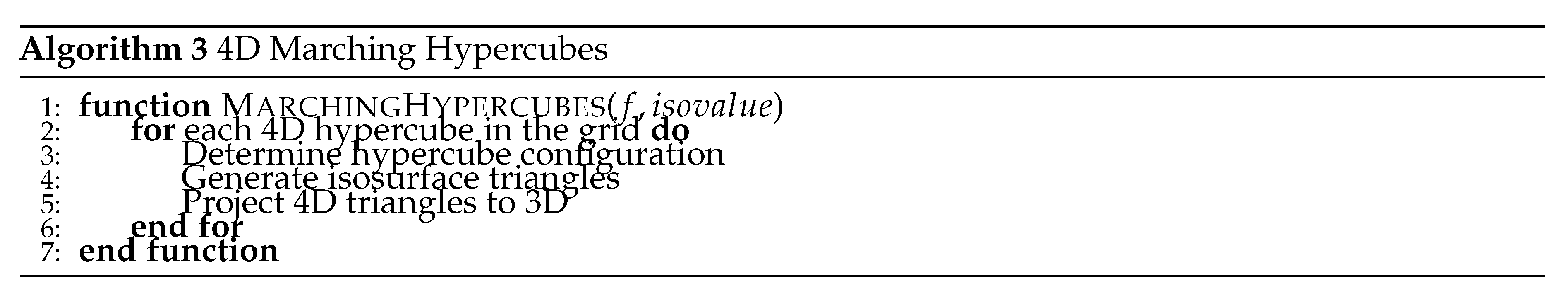

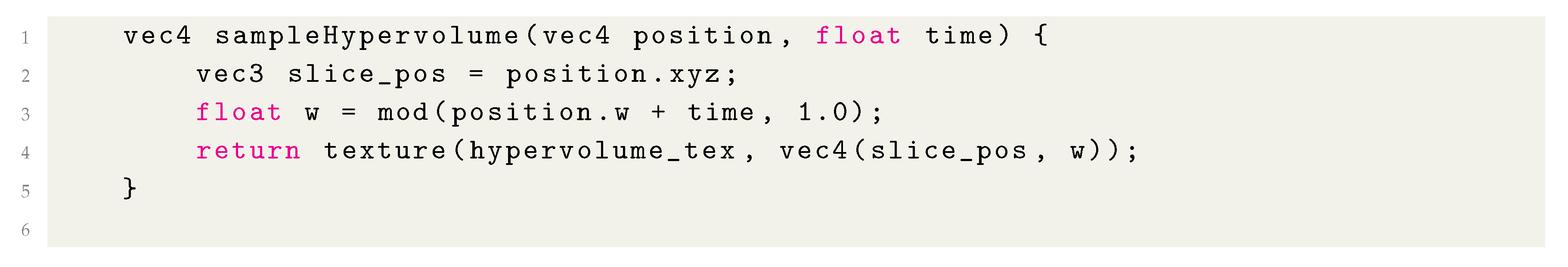

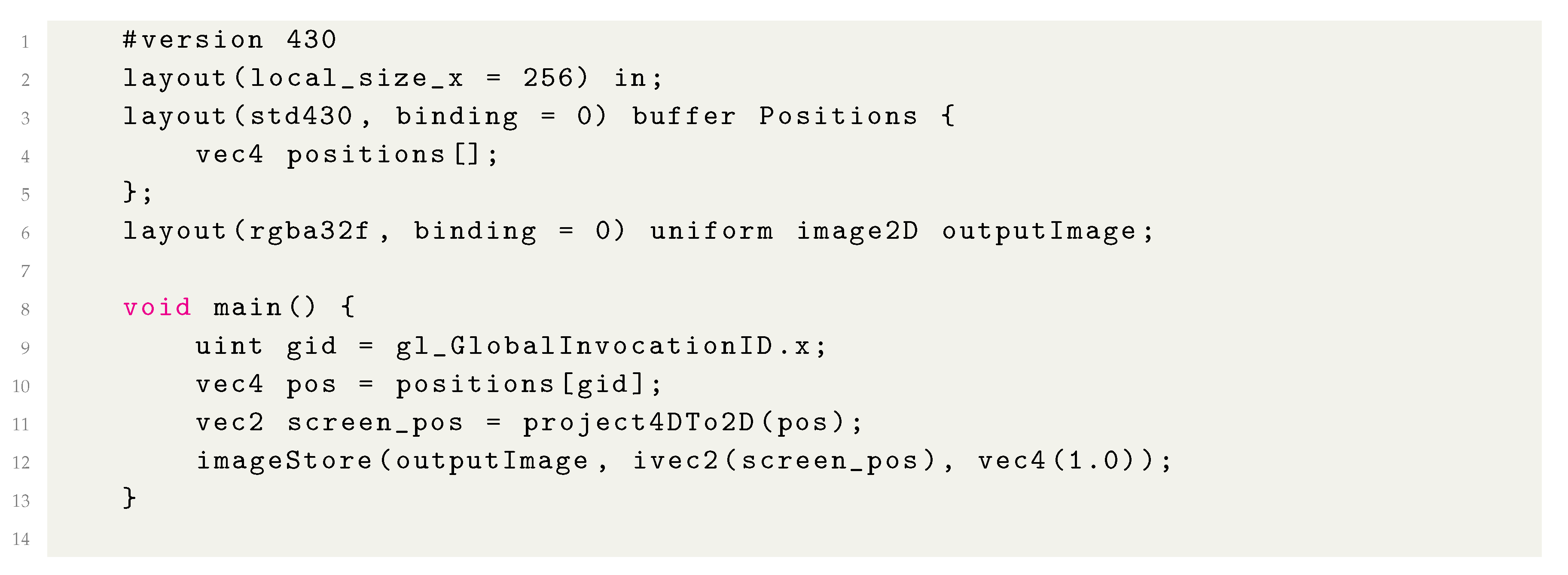

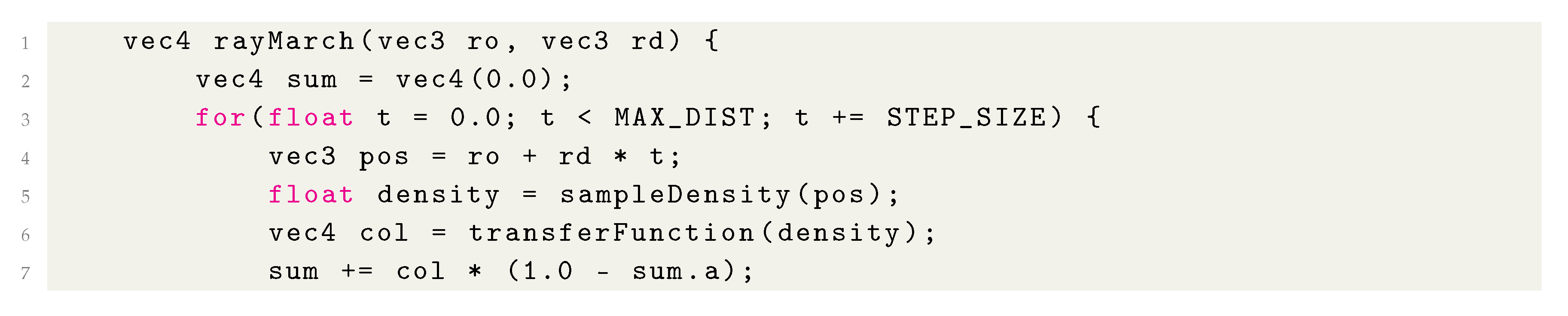

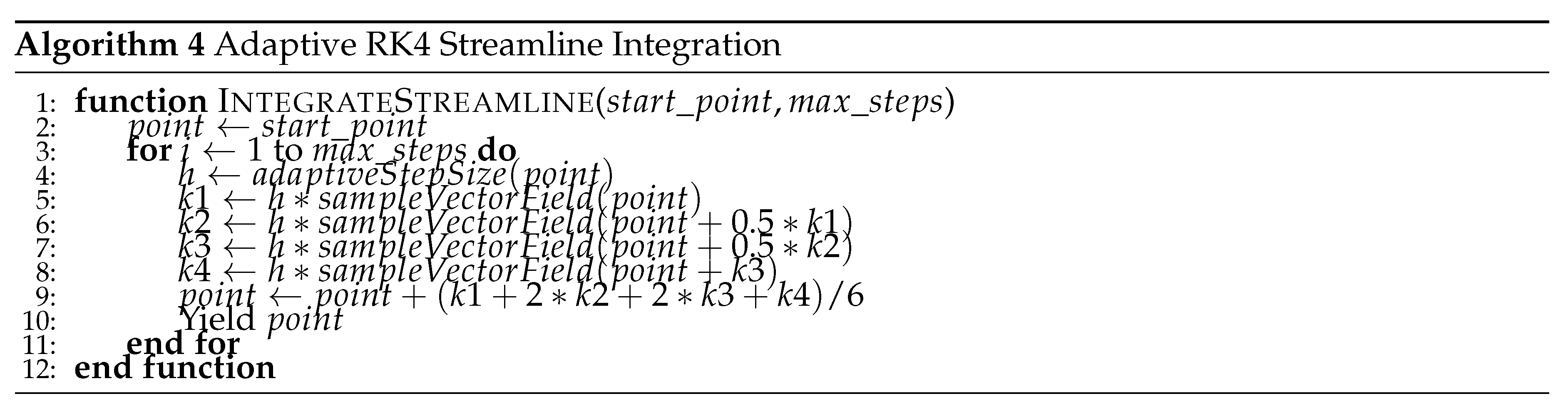

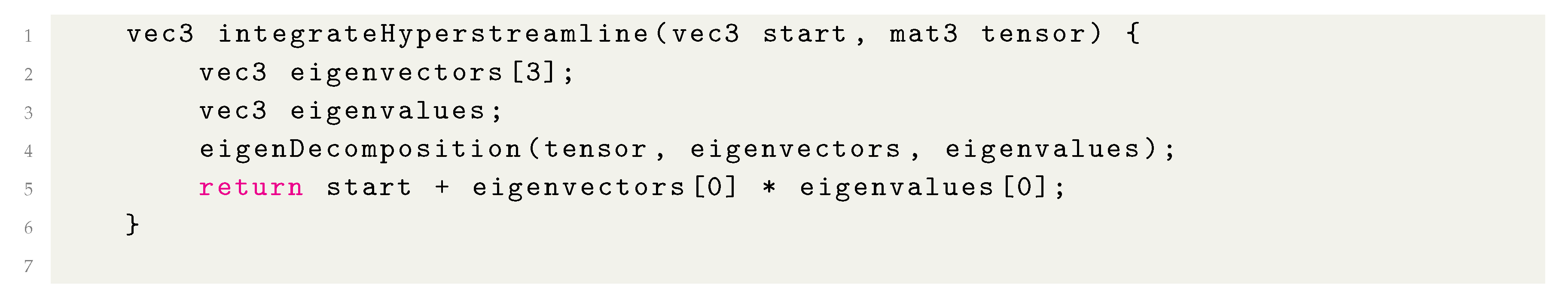

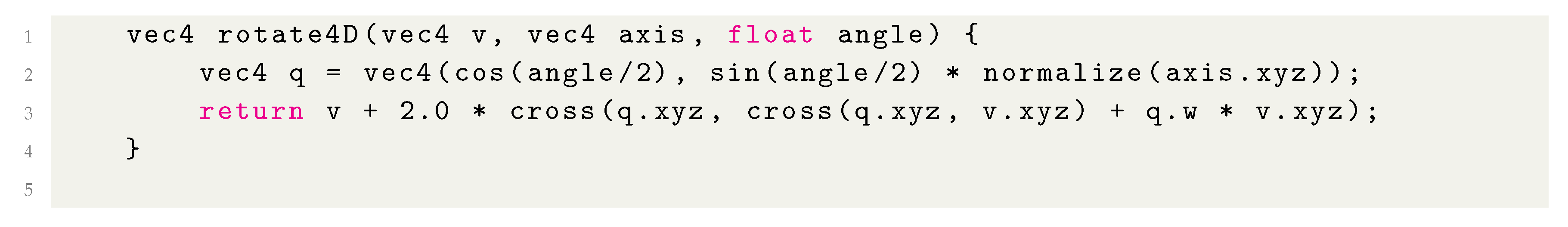

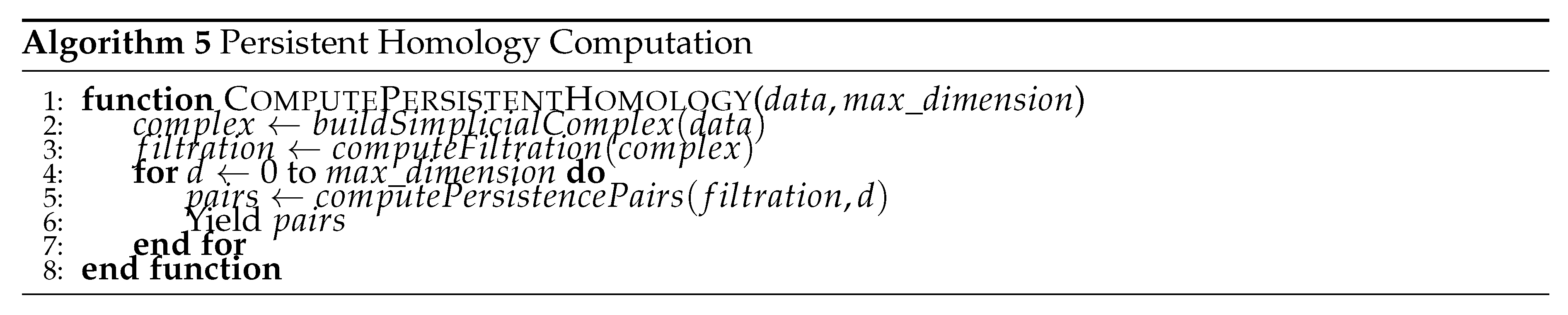

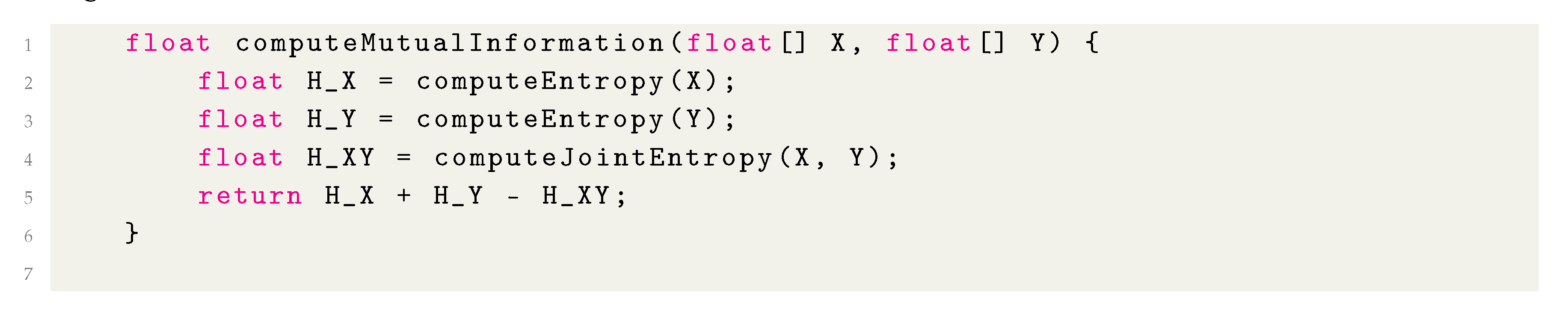

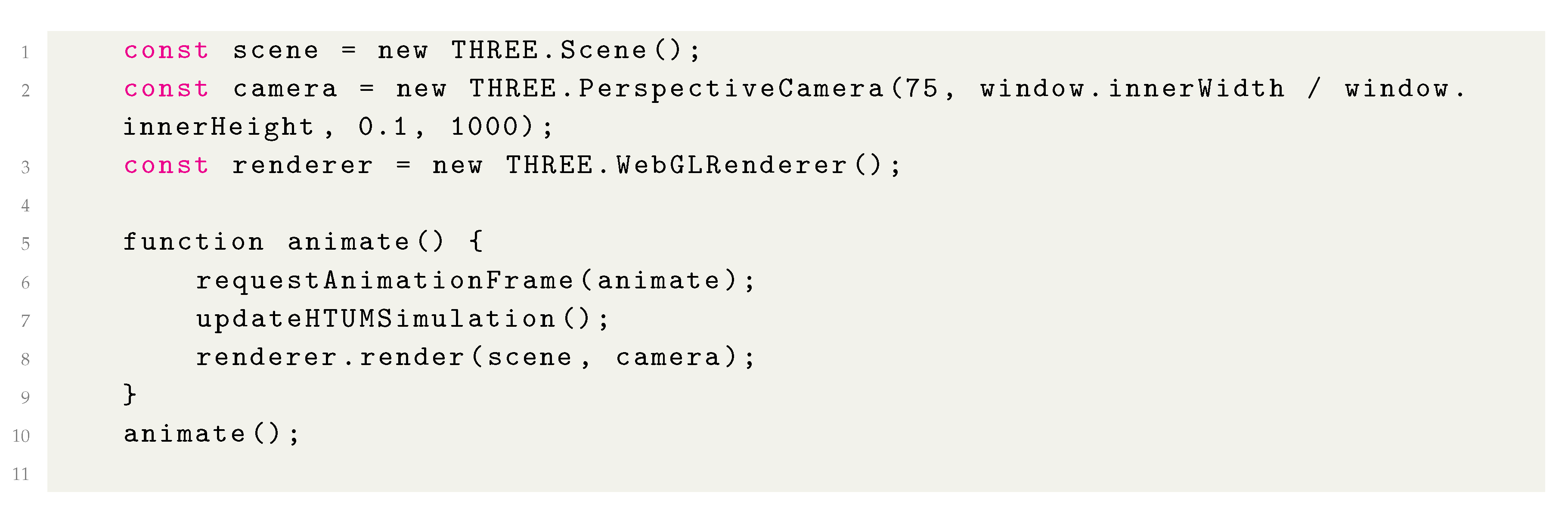

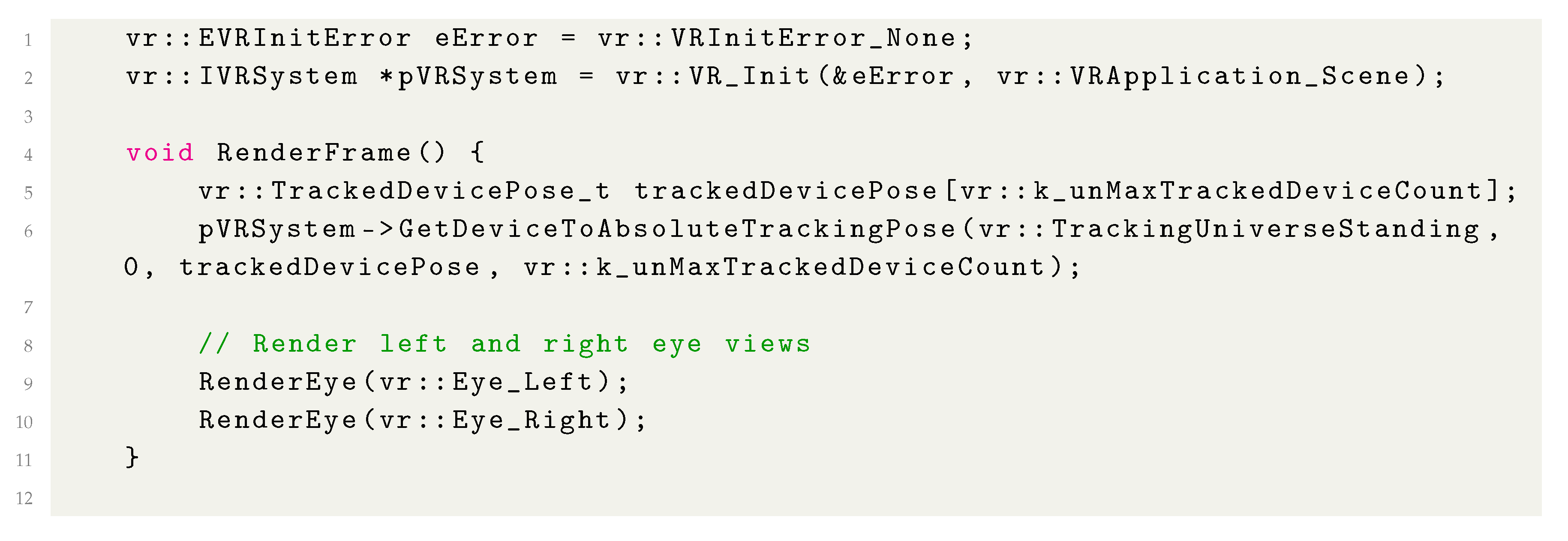

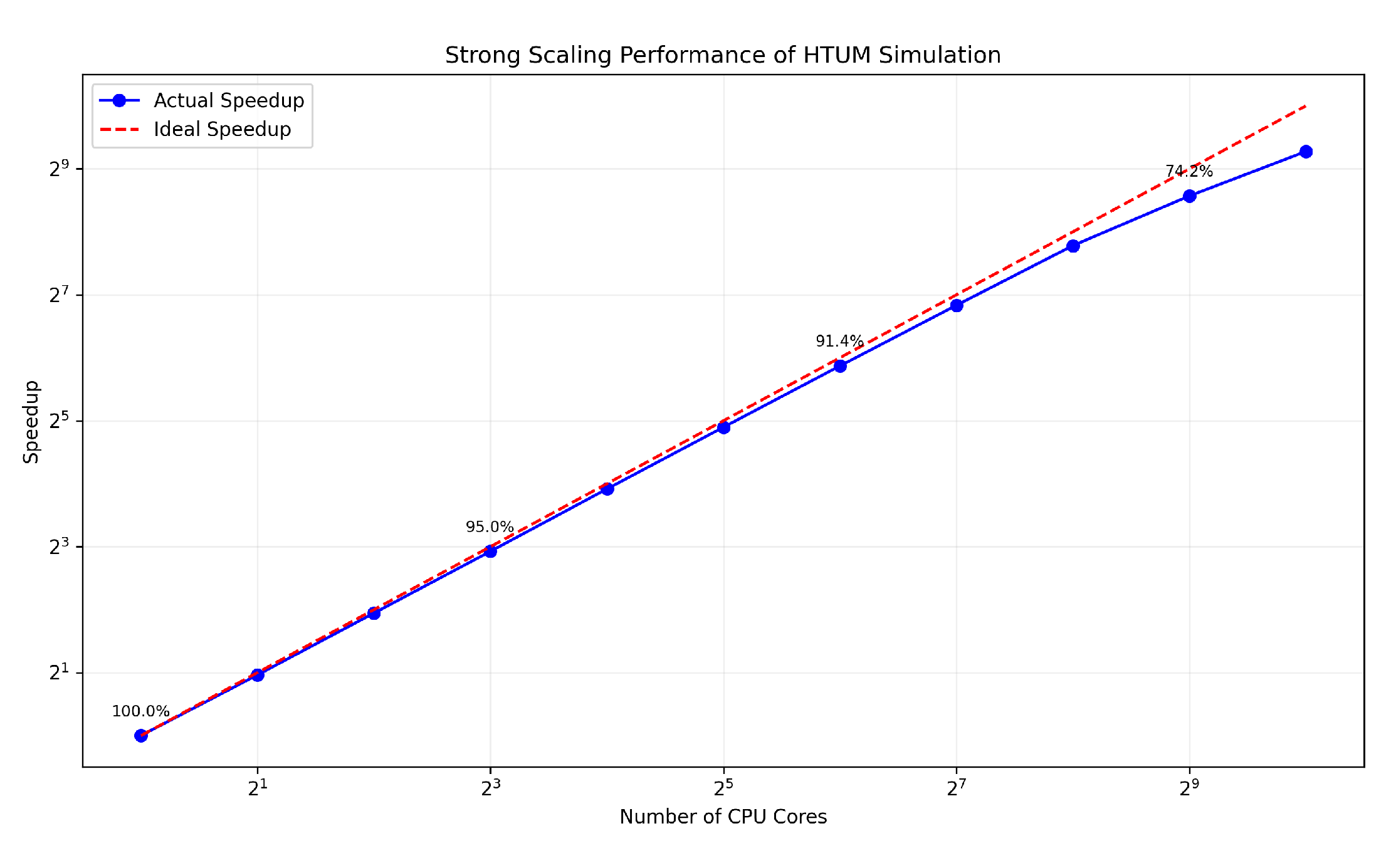

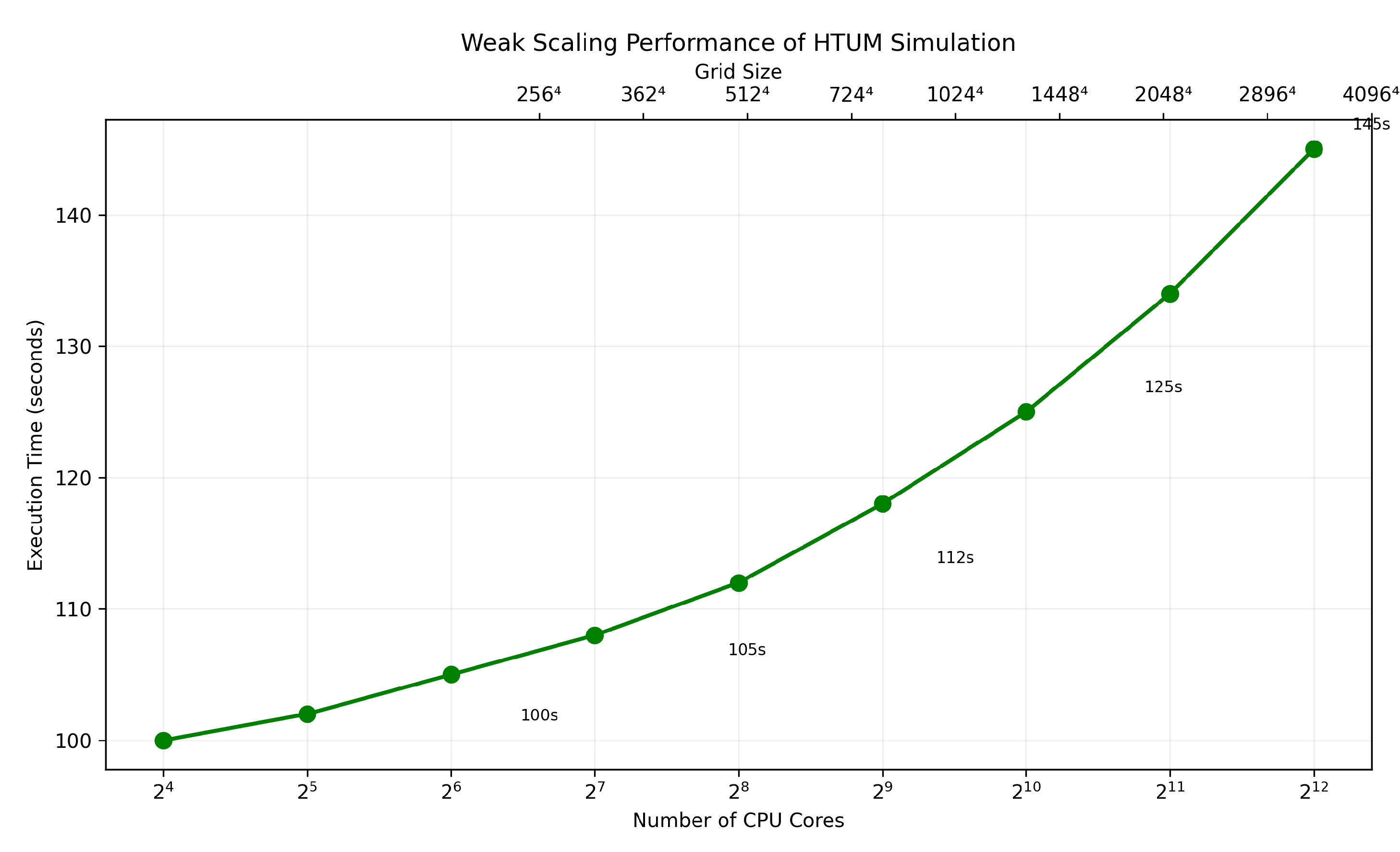

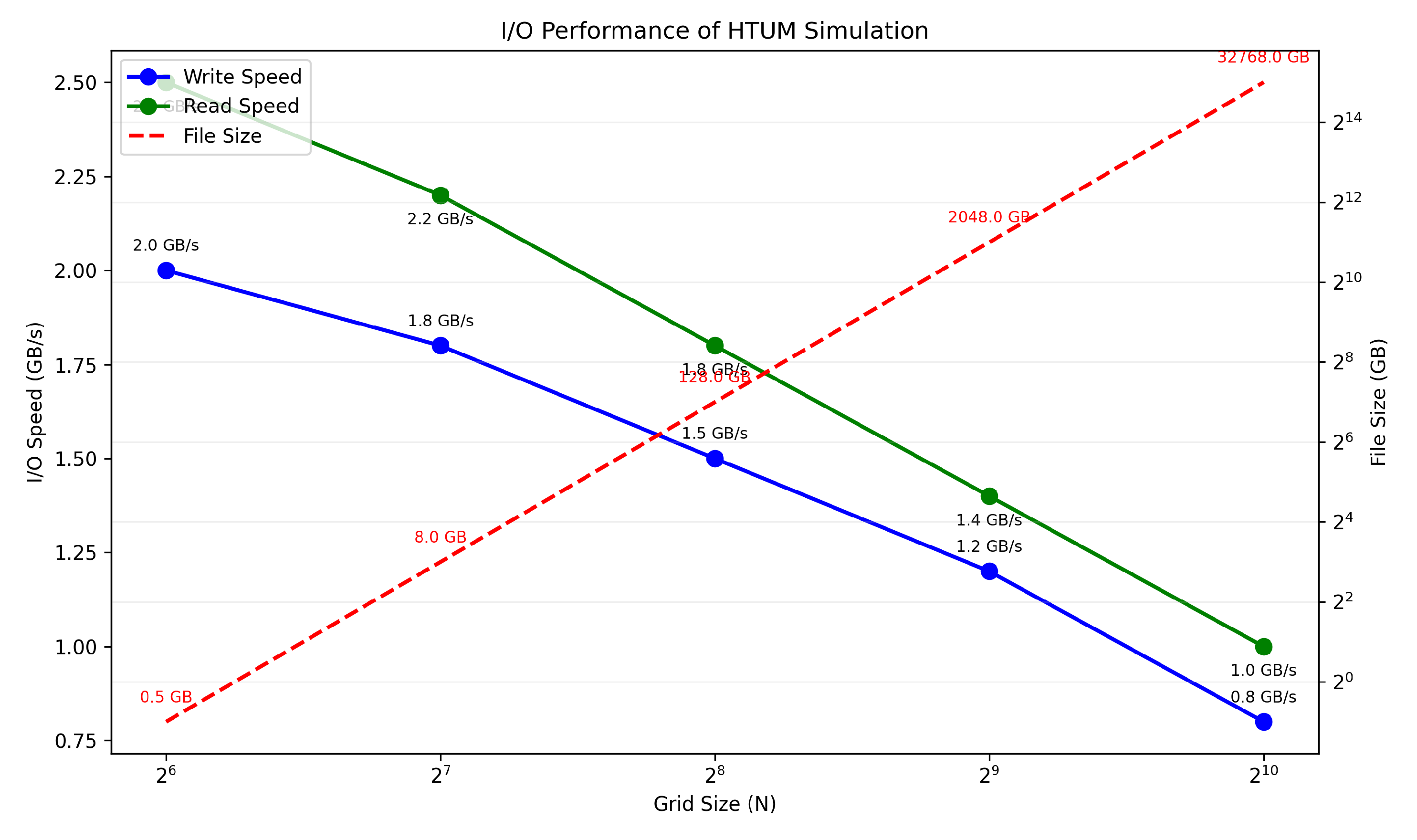

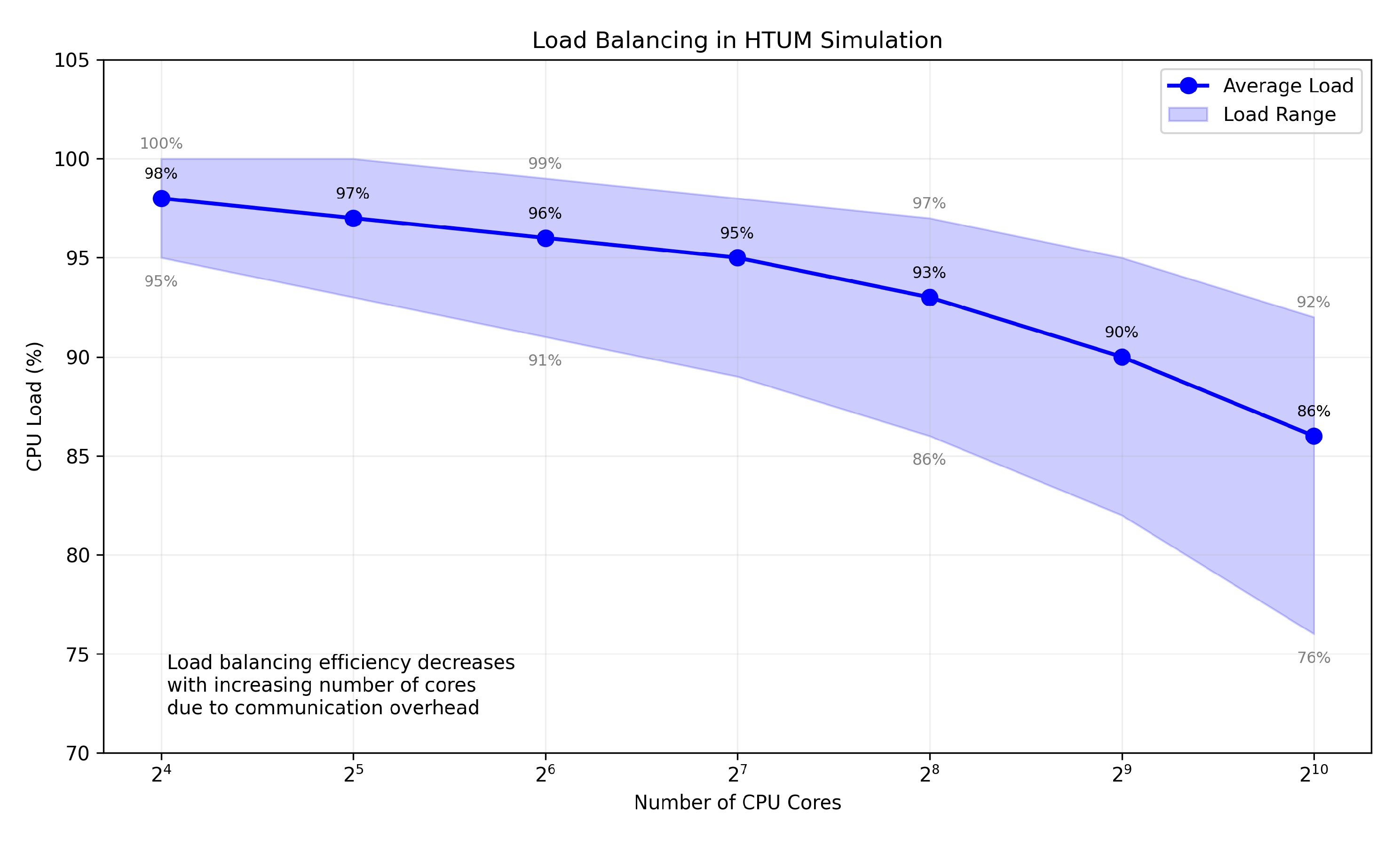

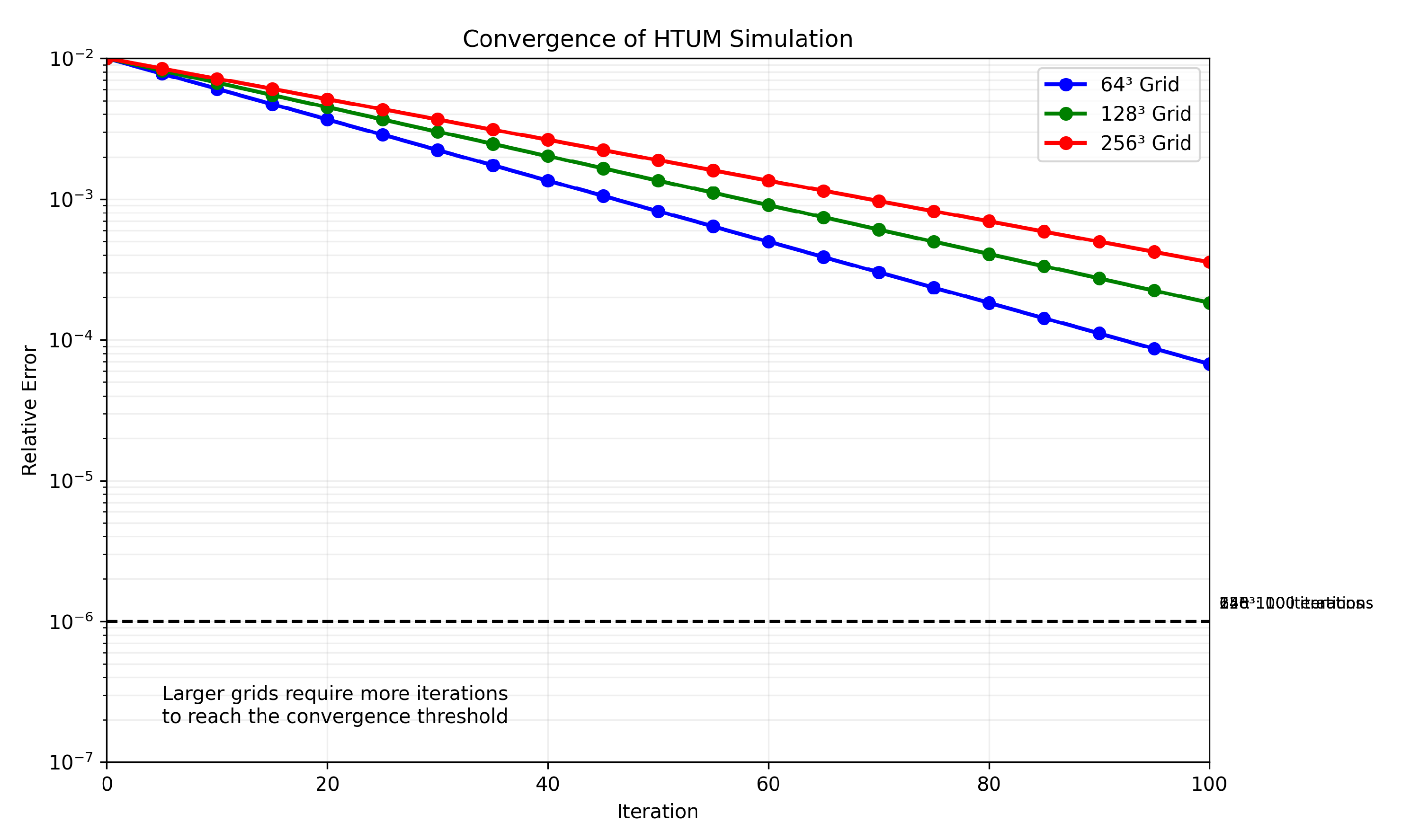

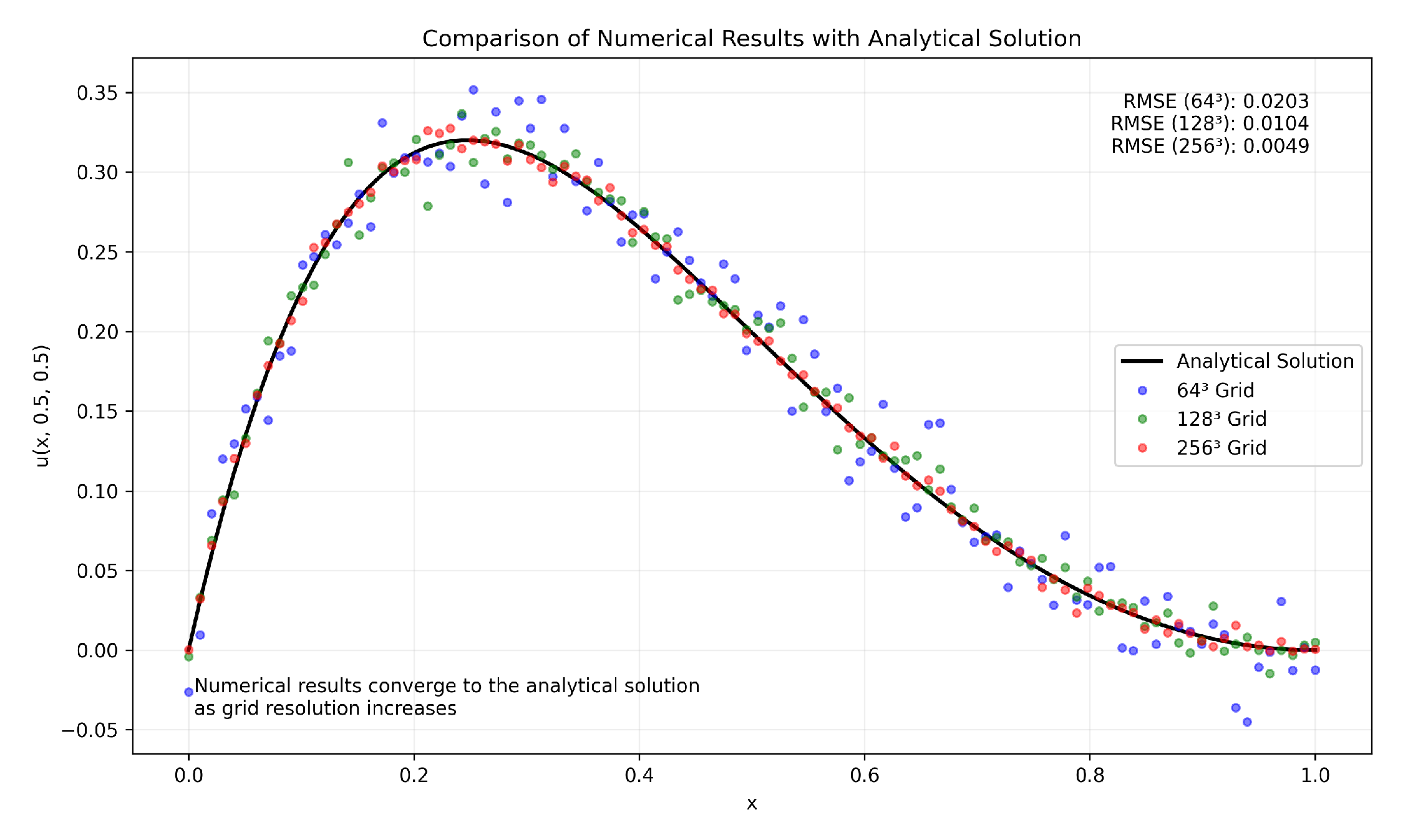

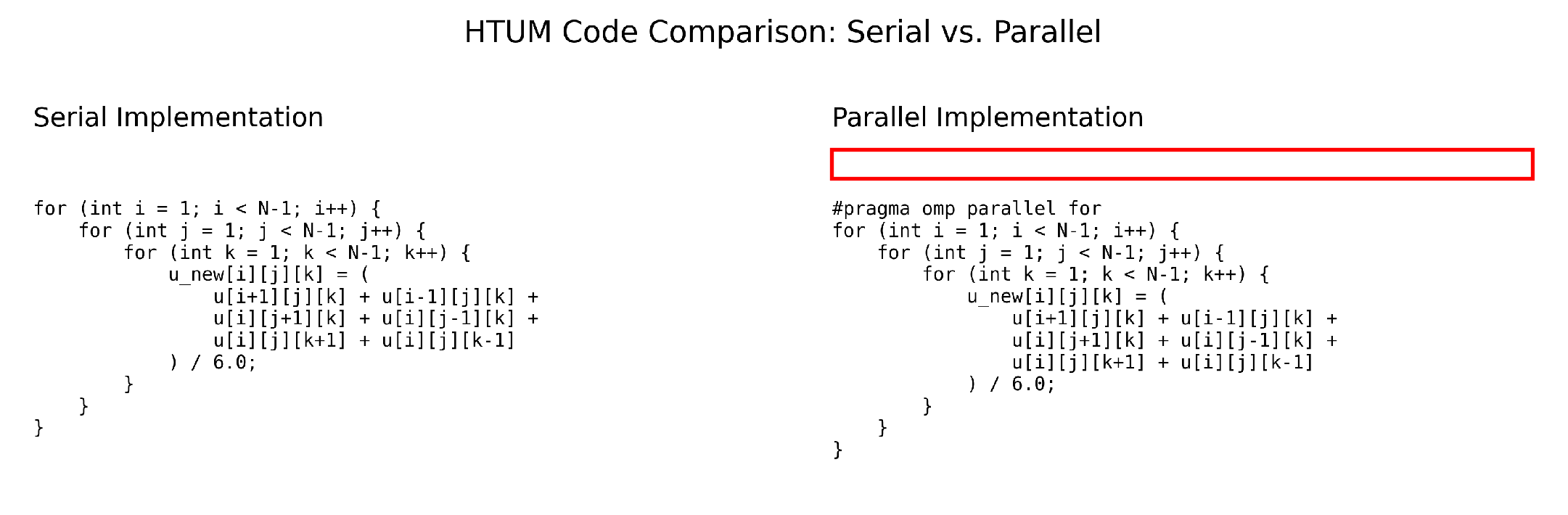

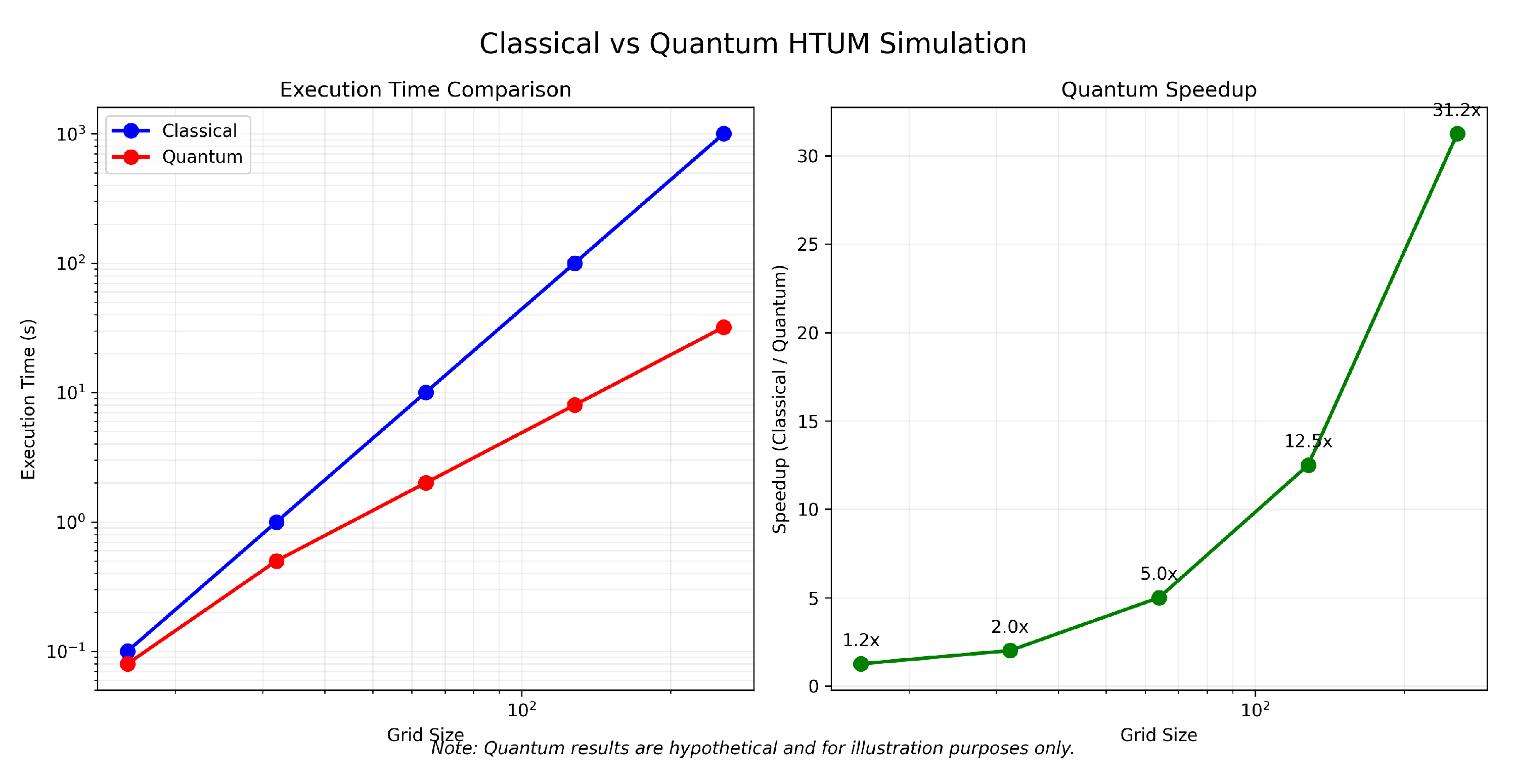

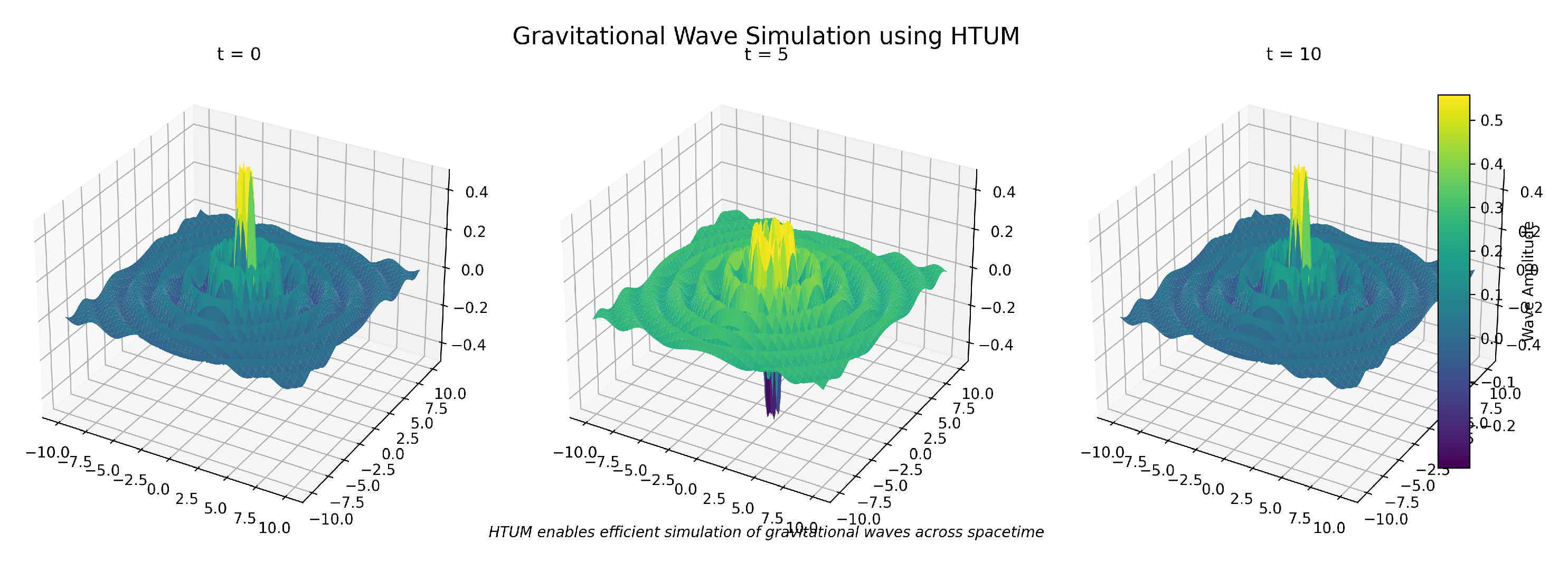

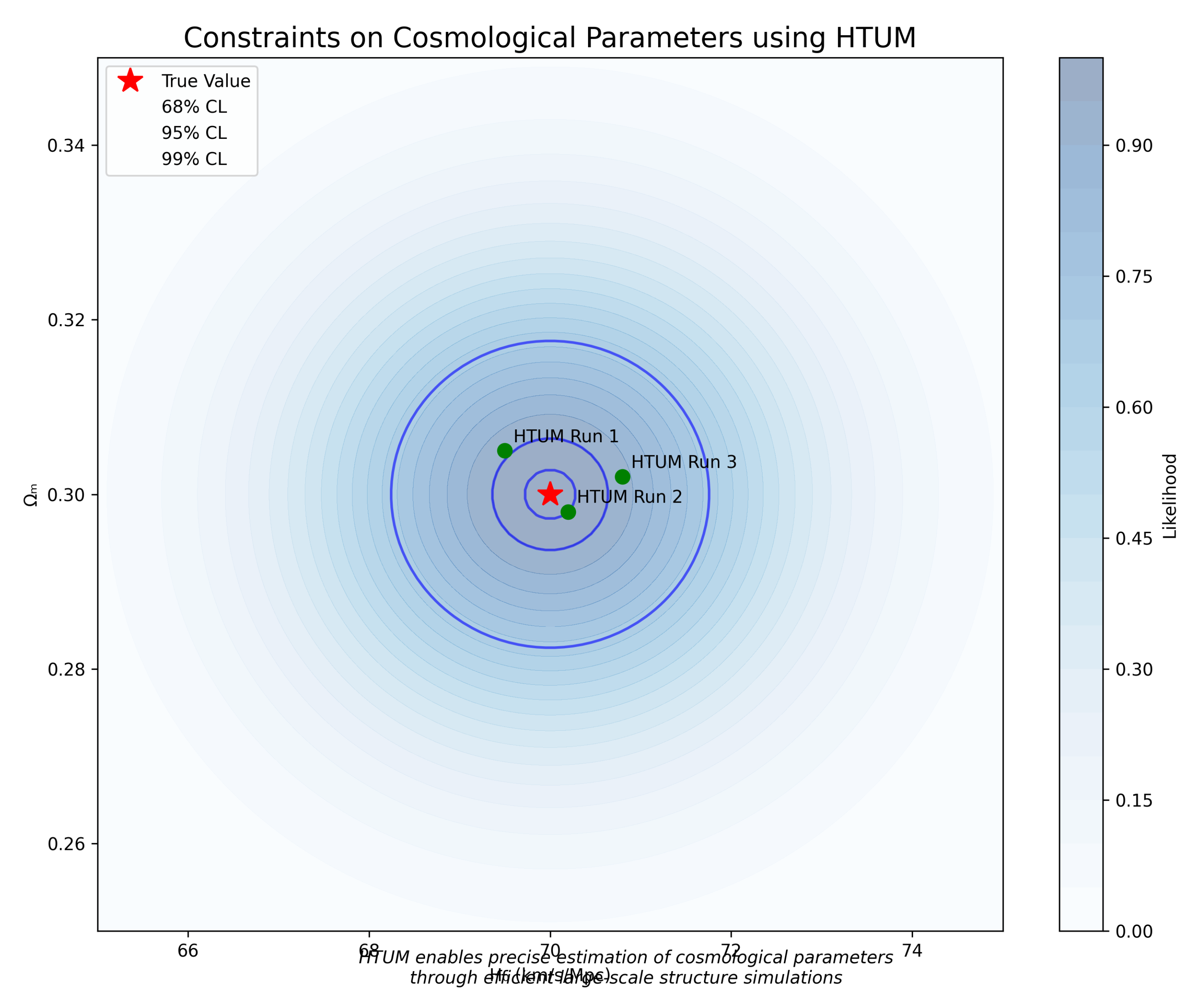

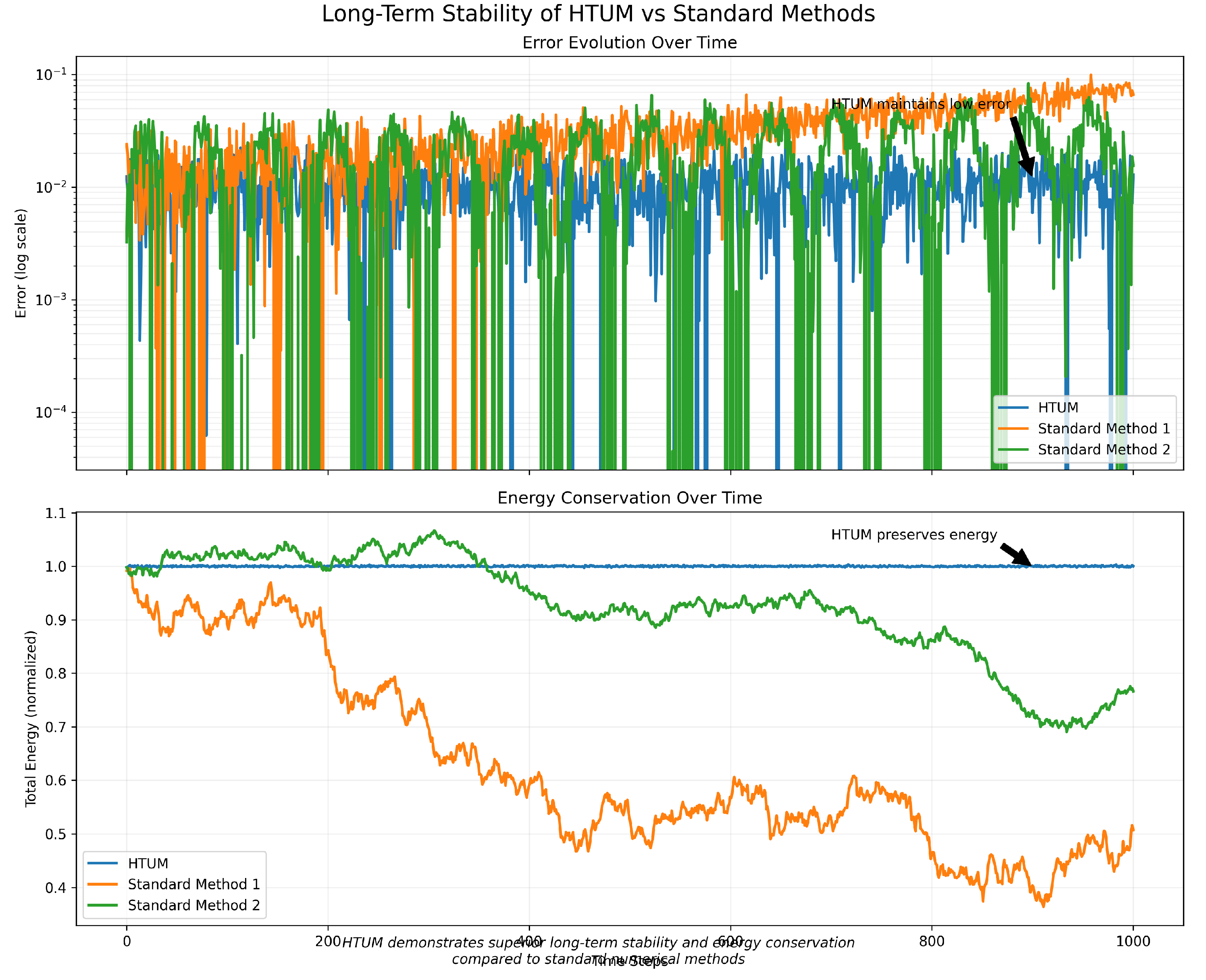

- Section 21: Numerical Simulation Framework - We present a comprehensive computational framework developed to simulate the complex dynamics of HTUM. This section details how we model the 4-dimensional toroidal structure (4DTS), incorporate quantum effects, gravitational dynamics, and the proposed mechanisms for dark matter and dark energy. We discuss our innovative approach to unified mathematical operations within the simulation, our numerical methods, and computational implementation strategies. The section also covers the various outputs generated by our simulation and the advanced visualization techniques we’ve developed. This framework serves as a crucial bridge between HTUM’s theoretical foundations and its empirical predictions, providing a powerful tool for exploring the model’s implications and generating testable hypotheses.

- Section 22: Testable Predictions and Empirical Validation - We discuss the challenges of testing HTUM’s predictions experimentally and provide a roadmap for future experimental work and collaborations.

- Section 23: Implications for the Nature of Reality - This Section delves into the philosophical implications of HTUM, particularly concerning the nature of time and the mind-matter relationship.

- Section 24: Conclusion - The final Section discusses HTUM’s potential impact on cosmology and its relationship to other disciplines, emphasizing the importance of interdisciplinary research and collaboration.

-

Appendices A–E: Mathematical Foundations and Computational Methods - We provide five comprehensive appendices that delve into the mathematical and computational aspects of HTUM:

- Appendix A: A detailed exploration of the Topological Vacuum Energy Modulator (TVEM), including its foundations, mechanisms, and implications.

- Appendix B: A rigorous mathematical treatment of HTUM’s conceptual framework.

- Appendix C: An advanced formulation of quantum gravity within the HTUM framework.

- Appendix D: Formal mathematical proofs and derivations supporting key HTUM concepts.

- Appendix E: A comprehensive description of the numerical simulation framework developed for HTUM, including algorithms, implementation details, and validation methods.

These appendices provide the mathematical rigor and computational framework underpinning HTUM, offering deeper insights into its theoretical structure and practical implementation.

1.3. Significance of HTUM in Cosmology

- Unified framework for fundamental forces: HTUM provides a novel geometric approach to unifying quantum mechanics and gravity, a long-standing challenge in theoretical physics [34,322,465]. By leveraging the unique properties of its 4-dimensional toroidal structure, HTUM offers a natural framework for reconciling these seemingly incompatible theories. This unification could lead to a deeper understanding of the universe’s fundamental forces and potentially resolve paradoxes at the intersection of quantum theory and general relativity, such as the information paradox in black holes [267].

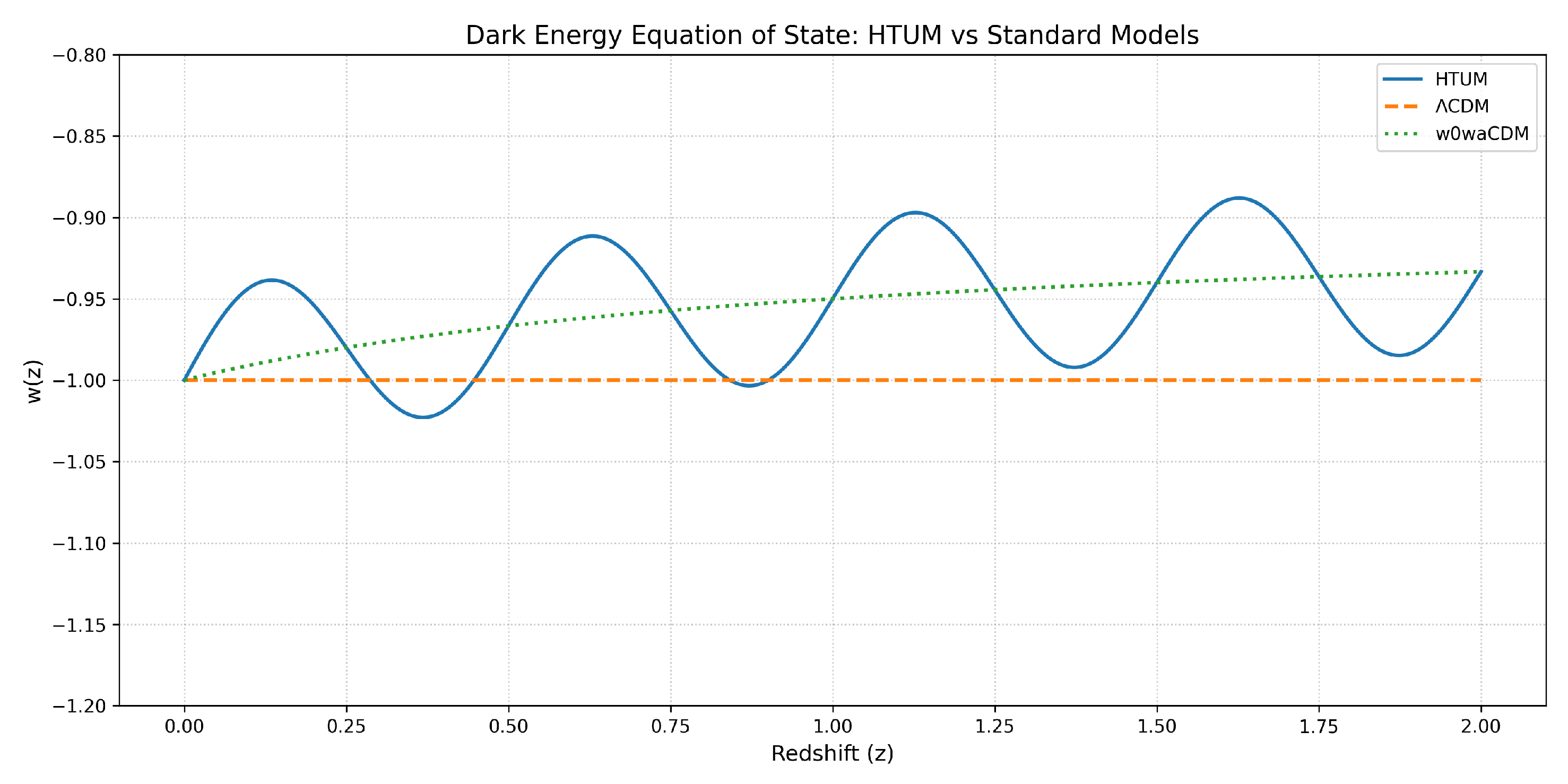

- Dark matter and dark energy: HTUM reconceptualizes dark matter and dark energy as nonlinear probabilistic phenomena arising from the toroidal structure of the universe [79,210,218]. This approach offers a new pathway to understanding these mysterious components, which constitute about 95% of the universe’s content. By integrating dark matter and dark energy into the fabric of spacetime itself, HTUM provides a more cohesive explanation for their ubiquitous presence and effects on cosmic evolution.

- Cosmological constant problem: One of HTUM’s most significant contributions is its approach to the cosmological constant problem [564]. By introducing the TVEM function, HTUM offers a mechanism to naturally suppress the extreme vacuum energy values predicted by quantum field theory. This could resolve one of the most pressing issues in modern cosmology, providing a theoretically motivated solution to the vast discrepancy between observed and predicted vacuum energy densities.

- Early universe and inflation: HTUM presents a unique perspective on cosmic inflation and the early universe [250]. The model’s toroidal structure provides a natural mechanism for ending inflation, potentially resolving the "graceful exit" problem. Furthermore, HTUM’s approach to quantum cosmology offers new insights into the universe’s initial conditions and the emergence of classical spacetime from quantum fluctuations [261].

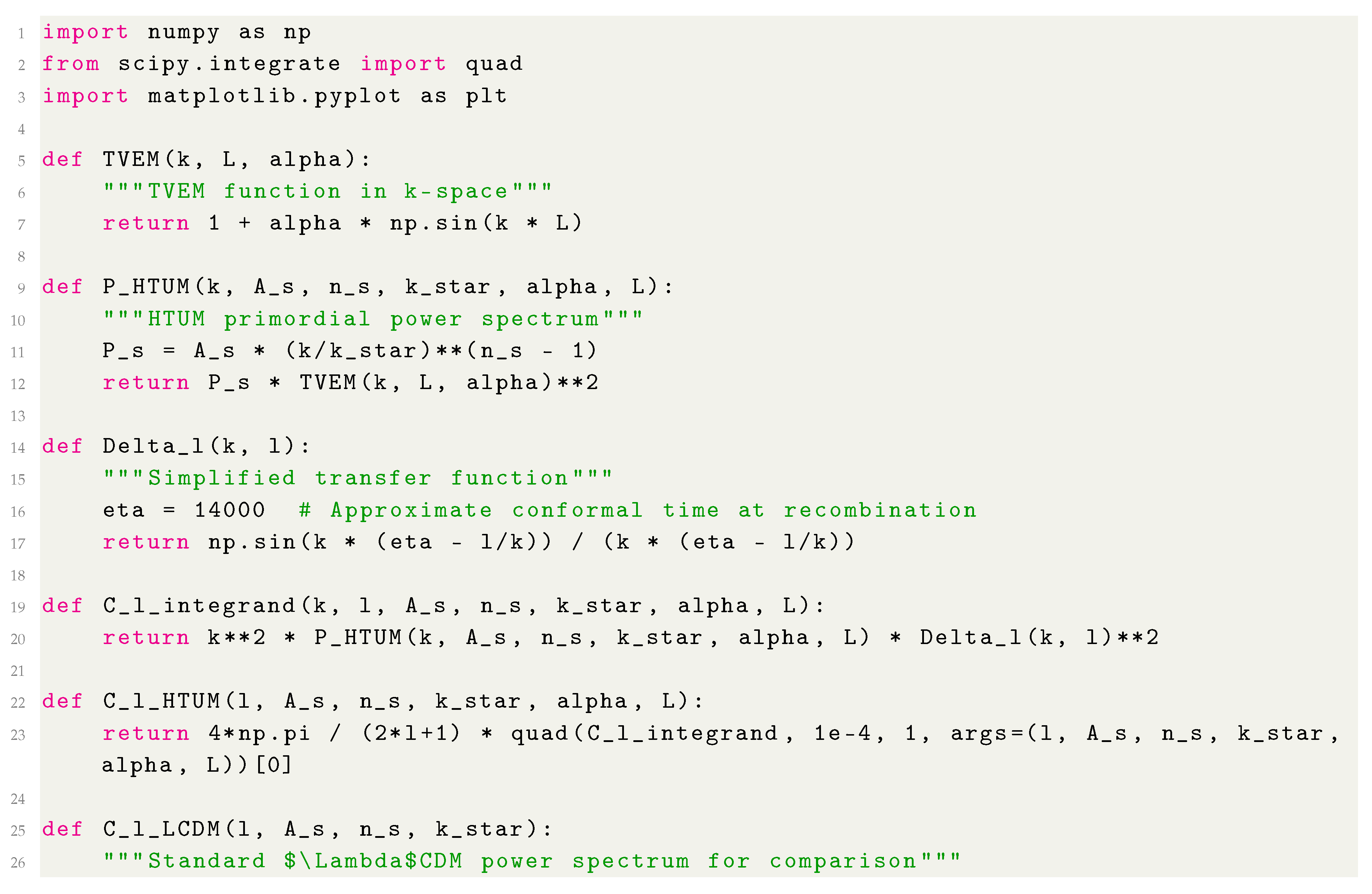

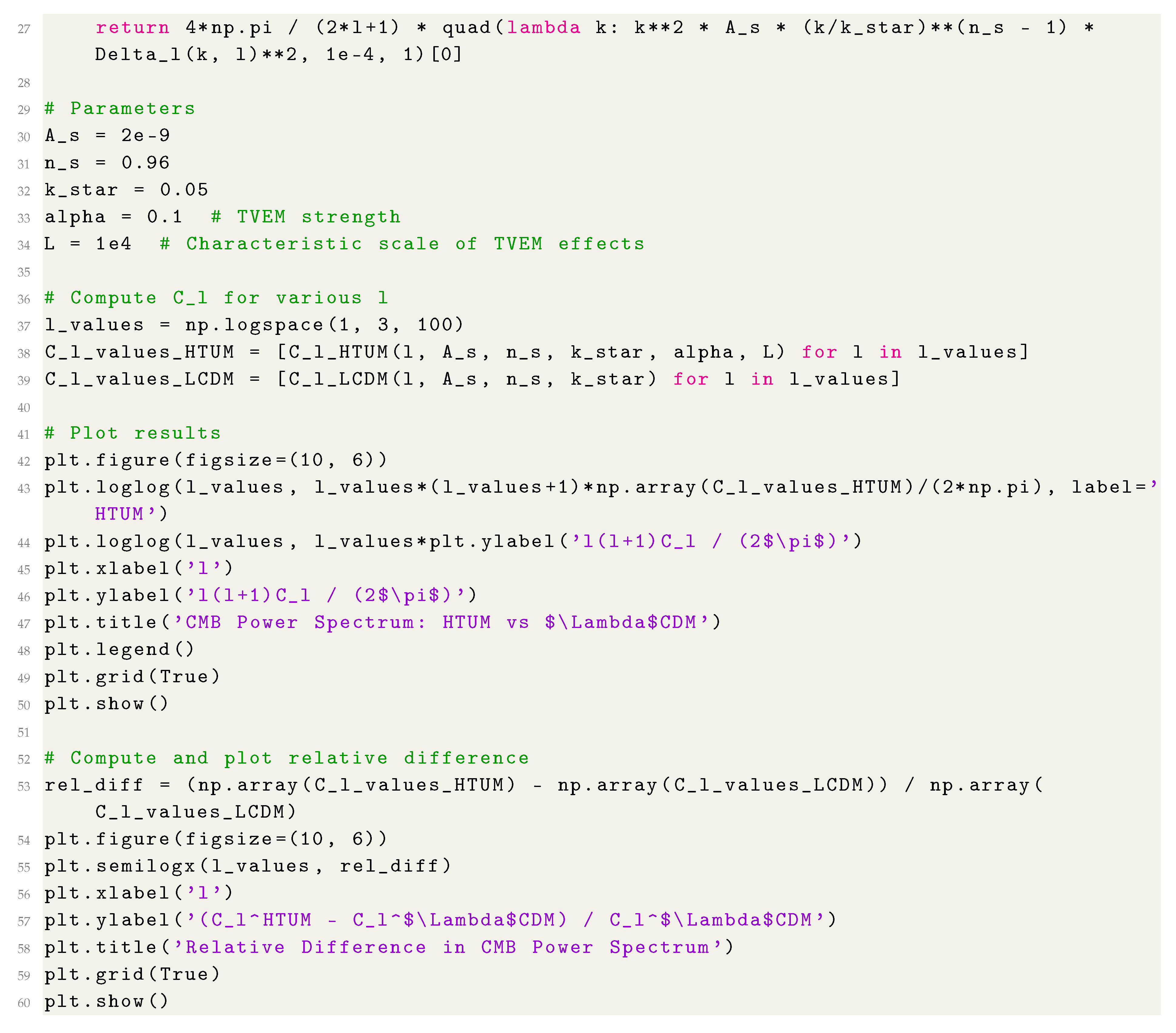

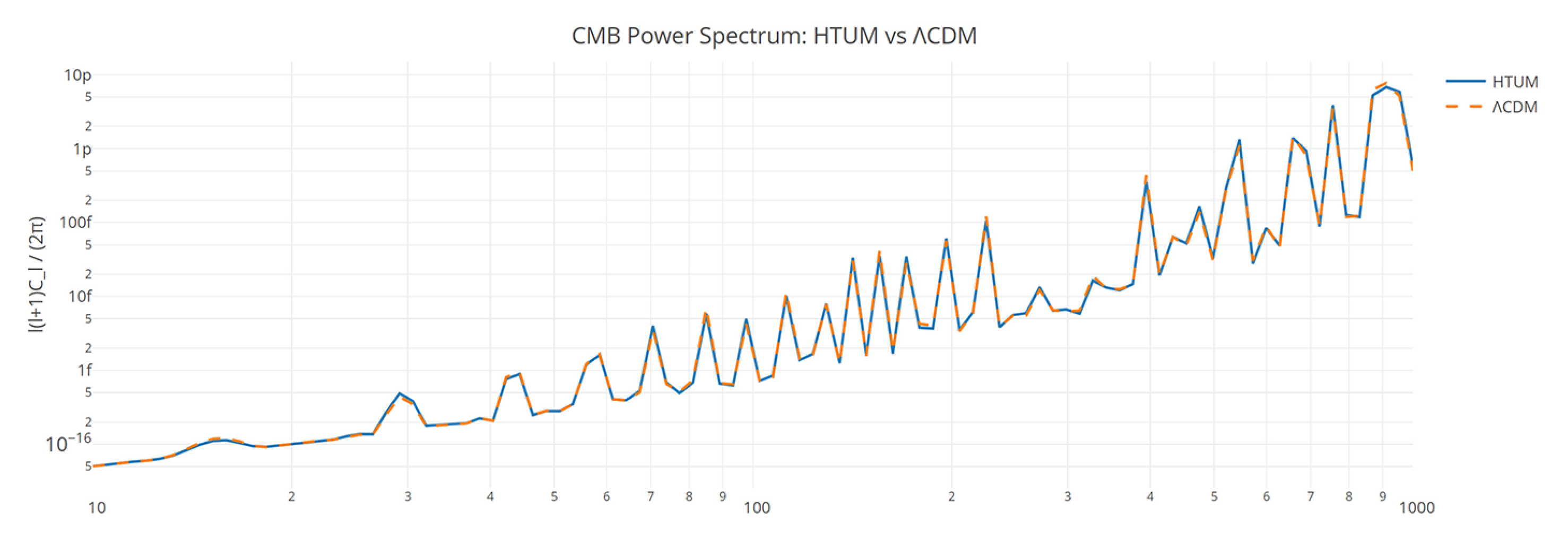

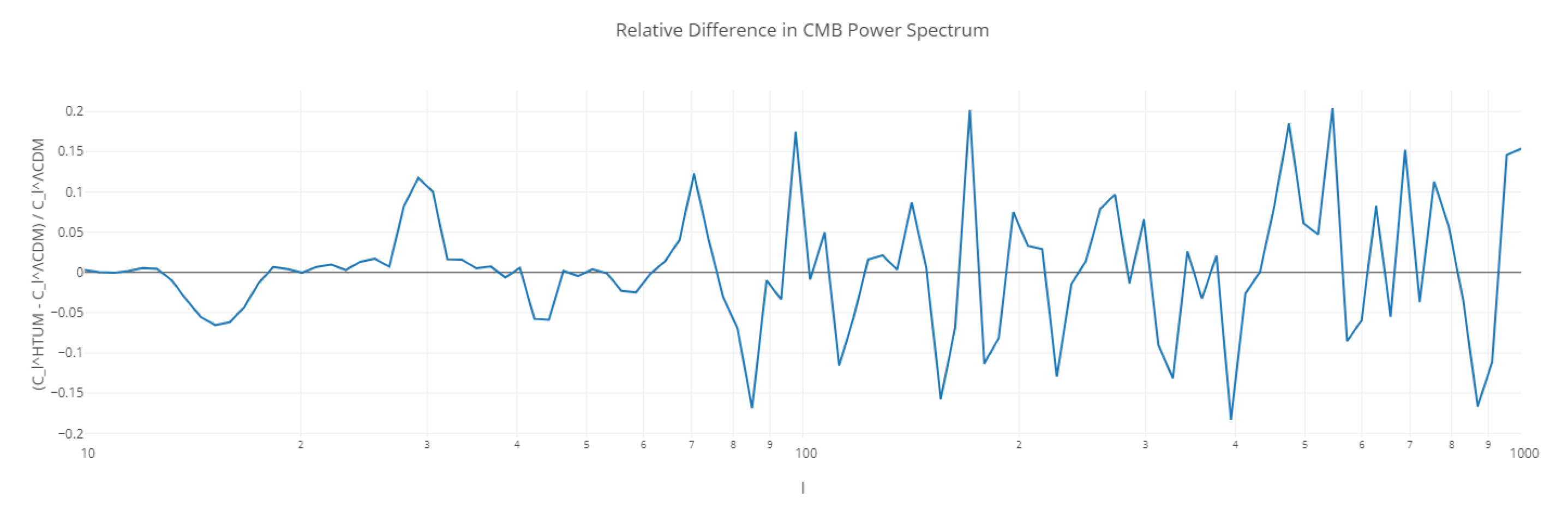

- Large-scale structure and CMB anomalies: HTUM’s toroidal geometry leads to specific predictions about the universe’s large-scale structure and potential anomalies in the CMB [149]. The model offers explanations for observed large-scale anomalies that are challenging to account for in standard cosmological models, providing testable predictions for future CMB experiments and large-scale structure surveys [350].

- Quantum-to-classical transition: HTUM provides a smooth and natural explanation for the emergence of classical reality from the quantum substrate [601]. This approach addresses the measurement problem in quantum mechanics and offers insights into the nature of wave function collapse, decoherence, and the role of consciousness in quantum measurements [420].

- Nature of time and causality: HTUM challenges conventional notions of time, presenting it as an emergent property arising from the causal relationships within the toroidal structure [51,468,500]. This perspective offers new insights into the arrow of time, the nature of causality, and the potential for closed timelike curves in extreme gravitational conditions [239].

- Black hole physics: HTUM’s framework provides novel approaches to understanding black hole physics, including potential resolutions to the information paradox and new perspectives on Hawking radiation [16,267]. The model’s toroidal structure uniquely preserves information across the event horizon, potentially reconciling quantum mechanics with general relativity in extreme gravitational scenarios.

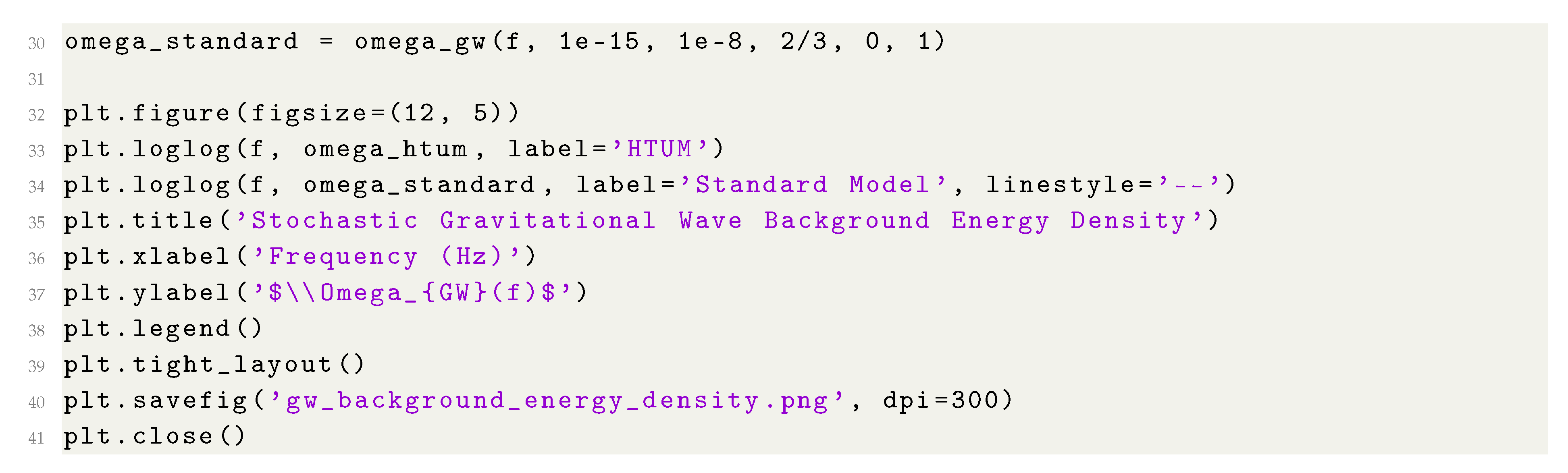

- Observational cosmology: HTUM makes specific, testable predictions across various cosmological observables, including the CMB power spectrum, gravitational wave signatures, and the distribution of large-scale structures [350]. These predictions offer multiple avenues for empirical validation, distinguishing HTUM from the standard CDM model and other alternative cosmological theories.

- Philosophical implications: Beyond its physical predictions, HTUM offers profound philosophical insights into the nature of reality, consciousness, and the role of observers in the universe [132,396,536]. By integrating consciousness into the fundamental fabric of the cosmos, HTUM provides a framework for addressing long-standing questions in the philosophy of mind and the nature of subjective experience.

- Computational cosmology: HTUM’s perspective on the universe as a vast information processing system opens new avenues for understanding cosmic evolution in terms of computation and information theory [360]. This could lead to novel approaches to simulating cosmic evolution and understanding the limits of predictability in complex systems.

2. Theoretical Foundations

2.1. The Lambda-CDM Model and Cosmic Evolution Scenarios

2.2. Historical Context

2.3. Limitations of the Lambda-CDM Model

- Singularity problem: The theory begins with a singularity, a point of infinite density and temperature, which current physics cannot adequately describe [270].

- Flatness problem: The observed spatial flatness of the universe requires fine-tuning initial conditions, which seems improbable [179].

- Dark matter and dark energy: While the Lambda-CDM model incorporates dark matter and dark energy as critical components, it does not fully explain their fundamental nature or origin [455,538]. The model describes their effects but leaves questions about their underlying physics and how they evolved throughout cosmic history.

2.4. The Cosmological Constant Problem

2.5. Addressing Limitations with HTUM

- Singularity and causality: HTUM redefines the singularity not as a point of infinite density but as a phase transition within the toroidal structure, potentially resolving the singularity problem [408,434]. In HTUM, the singularity is replaced by a smooth transition between cycles, maintaining the continuity of space-time and causality.

- Causal connectivity: The toroidal geometry of HTUM allows for a natural explanation of the horizon problem, as regions of the universe can remain in causal contact through the torus’s topology [346,364]. The compact nature of the torus ensures that light and information can propagate around the universe, maintaining causal connectivity and explaining the observed uniformity of the CMB.

- Spatial flatness: HTUM’s cyclical nature provides a mechanism for maintaining spatial flatness without requiring fine-tuning [53,508]. As the universe undergoes repeated cycles of expansion and contraction, any initial curvature is smoothed out over time, leading to the observed flatness of space. This concept is explored in more detail in Section 3.5, where we discuss how HTUM’s toroidal structure naturally addresses the flatness problem.

- Integration of dark matter and dark energy: HTUM incorporates dark matter and dark energy as fundamental components driving the universe’s cyclical behavior and structural evolution [53,508]. Dark matter plays a crucial role in the formation and stability of the toroidal structure, while dark energy drives the expansion and contraction phases of the cosmic cycle.

| Feature | Lambda-CDM | HTUM |

|---|---|---|

| Universe structure | Expanding | 4D toroidal, cyclical |

| Origin | Big Bang singularity | Phase transition |

| Flatness | Requires fine-tuning | Naturally flat |

| Horizon problem | Requires inflation | Causal connectivity |

| Dark matter | Unknown particle | Nonlinear phenomenon |

| Dark energy | Cosmological constant | Dynamic component |

| Future | Eternal expansion | Cyclic evolution |

| Singularities | Present | Avoided |

| Quantum gravity | Not integrated | Potentially unified |

2.6. HTUM and Cosmological Challenges

2.7. Implications and Future Directions

- Unification of quantum mechanics and gravity: HTUM’s toroidal geometry may provide a framework for reconciling quantum mechanics and general relativity, as the model naturally incorporates aspects of both theories [346,364]. The smooth transition between cycles in HTUM could potentially resolve the incompatibility between these two fundamental theories, leading to a more unified theory of quantum gravity.

- Experimental tests: The predictions of HTUM can be tested through various experimental methods, such as precision measurements of the CMB, gravitational wave observations, and studies of large-scale structure [346,364]. Future missions like the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST) could provide crucial data to validate or refine the model.

- Philosophical implications: HTUM challenges our understanding of the nature of reality, time, and the role of consciousness in the universe. The model’s cyclical nature and the interconnectedness of space, time, and matter raise profound questions about causality, determinism, free will, and the role of consciousness in the universe [346,364]. These philosophical implications invite interdisciplinary collaborations between physicists, philosophers, and other scholars to explore the deeper meaning of our existence.

- Technological advancements: The insights gained from HTUM could lead to technological advancements in fields such as energy production, space exploration, and computing [346,364]. Understanding the universe’s fundamental principles may inspire novel approaches to harnessing energy, developing more efficient propulsion systems, and creating advanced computational algorithms.

- Educational and public outreach: HTUM provides an exciting opportunity to engage the public in the wonders of cosmology and the scientific process. The model’s intuitive and visually appealing nature makes it accessible to a broad audience, fostering interest in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields. Educational programs, popular science books, and multimedia content based on HTUM could inspire the next generation of scientists and encourage public support for scientific research.

2.8. Conclusion

3. The Hyper-Torus Universe Model (HTUM)

3.1. Conceptual Framework

3.2. Toroidal Structure of the Universe

3.2.1. CMB Anomalies and Toroidal Topology

- The "Axis of Evil": An alignment of the quadrupole and octopole moments of the CMB along a specific axis [337].

- The cold spot: An unusually large and cold region in the CMB [162].

- Lack of large-scale power: A deficit in the CMB power spectrum at large angular scales [73].

- Hemispheric asymmetry: Differences in the CMB power spectrum between the northern and southern galactic hemispheres [206].

3.2.2. Scale-Dependent Topological Effects

- are spherical harmonics

- are the multipole coefficients

- is a mode-dependent function that depends on the torus size L

3.2.3. Symmetries and Alignments

3.2.4. The Cold Spot and Topological Defects

3.2.5. Comparison with Other Topological Models

- Simplicity: The toroidal structure is mathematically simpler and easier to model than more complex topologies.

- Naturalness: The torus emerges naturally from many quantum gravity theories [465].

- Comprehensive explanation: HTUM potentially explains multiple CMB anomalies within a single framework.

- Testability: The periodic nature of the torus leads to specific, testable predictions.

3.3. Mathematical Formulation of the Toroidal Structure

3.3.1. Embedding in Higher-Dimensional Space

3.3.2. Metric and Topology

3.3.3. Homology and Cohomology

3.3.4. Visualization Techniques

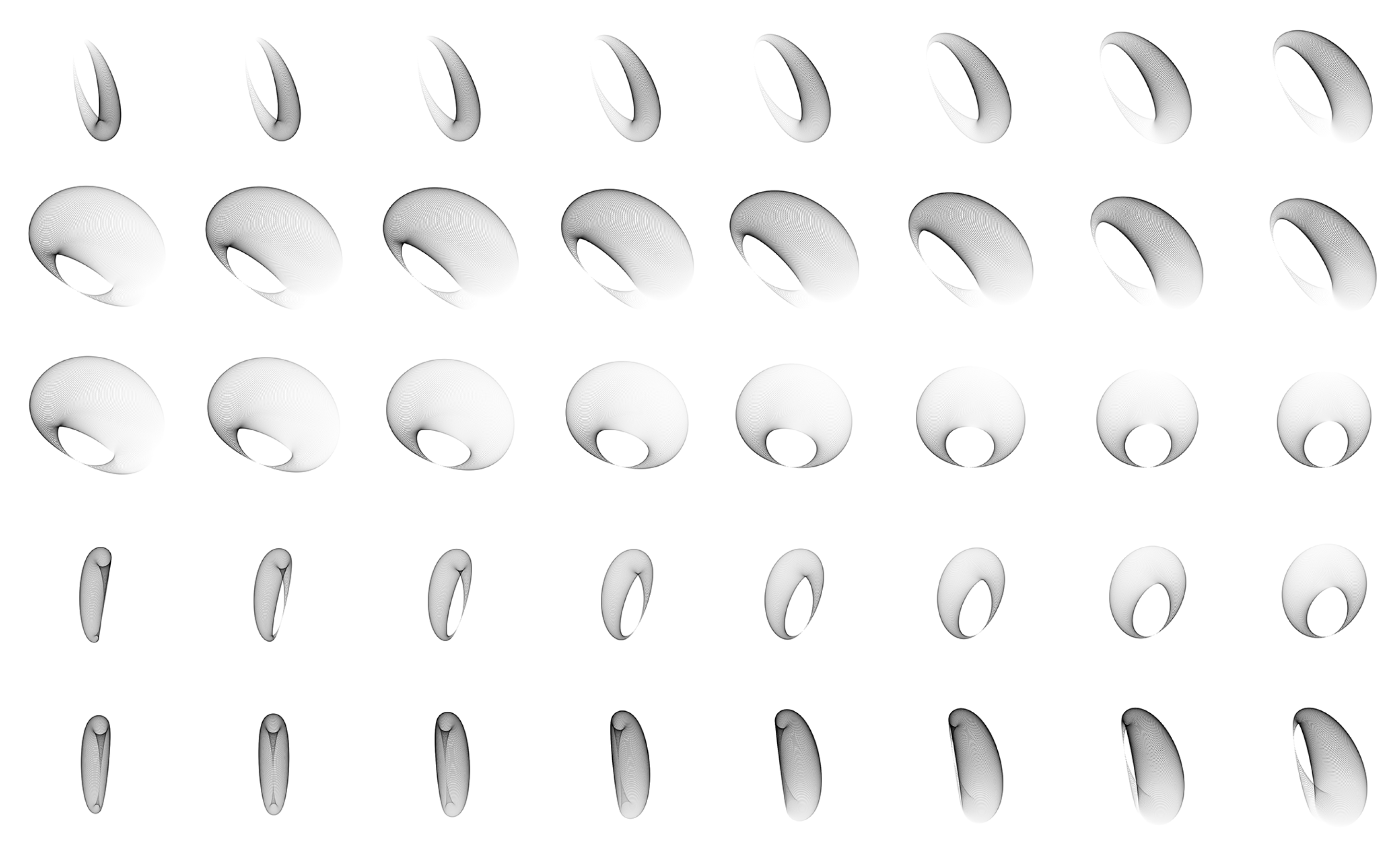

- Dimensional reduction: We can study lower-dimensional analogs, such as the 3-torus () or the 2-torus ().

- Slicing: We can examine 3D slices of the 4-torus, which would appear as a series of nested tori that change in size and position.

- Projection: We can project the 4-torus onto 3D space, resulting in a self-intersecting object known as a stereographic projection.

- Computer visualization: Advanced software can create interactive 4D visualizations that allow for rotation and manipulation in 4D space, with the results projected onto a 3D display [259].

3.3.5. Implications for HTUM

- Compactness: The 4-torus is a compact manifold, which aligns with the idea of a finite yet unbounded universe [364].

- Periodic boundary conditions: The toroidal structure implies periodic boundary conditions in all four dimensions, potentially explaining certain large-scale structures and symmetries in the universe [346].

- Multiple connectedness: The non-trivial topology of the 4-torus allows for multiple paths between points, which could have implications for the propagation of light and gravitational waves [158].

- Quantum entanglement: The interconnected nature of the 4-torus could provide a geometric framework for understanding quantum entanglement on a cosmic scale [12].

- Unification of forces: The complex topology of the 4-torus might offer a pathway for unifying the fundamental forces of nature within a single geometric structure [587].

3.4. Advanced Topological Concepts for the Toroidal Structure

3.4.1. Fiber Bundle Representation

- is the base space (our 4-dimensional torus)

- is the structure group (representing the phase of the wave function)

- is the projection map

3.4.2. Differential Forms on the 4-Torus

3.4.3. Connection and Curvature

3.4.4. Implications for HTUM

- It offers a mathematically rigorous framework for describing the geometry and topology of the 4-dimensional toroidal universe.

- It provides natural ways to incorporate quantum mechanical concepts (through the fiber bundle structure) and field theories (through differential forms and connections) into the model.

- It suggests new avenues for theoretical predictions and potential observational tests based on the topological and geometrical properties of the 4-torus.

- It connects HTUM to ongoing research in quantum gravity and topological quantum field theories, as explored in recent work by Gielen [234].

3.5. HTUM and the Flatness Problem

3.6. TQFT and the Hyper-Torus

3.7. Challenges in Visualizing and Conceptualizing a 4DTS

- Dimensional reduction: By studying lower-dimensional analogs, such as the three-dimensional torus () or the two-dimensional torus (), we can gain insights into the properties and behavior of the four-dimensional torus. These lower-dimensional models serve as stepping stones for understanding higher-dimensional structures [376].

- Mathematical visualization tools: Advanced mathematical software and visualization tools can help create representations of four-dimensional objects [258]. These tools can project higher-dimensional structures into three-dimensional space, allowing us to explore their properties interactively.

- Analogies and metaphors: Using analogies and metaphors can make abstract concepts more relatable [6]. For example, comparing the four-dimensional torus to a three-dimensional torus with an additional dimension of time or another spatial dimension can help bridge the gap in understanding.

- Educational resources: Developing educational resources, such as interactive simulations, videos, and detailed diagrams, can help teach and learn about higher-dimensional structures [376]. These resources can provide step-by-step explanations and visual aids to enhance comprehension.

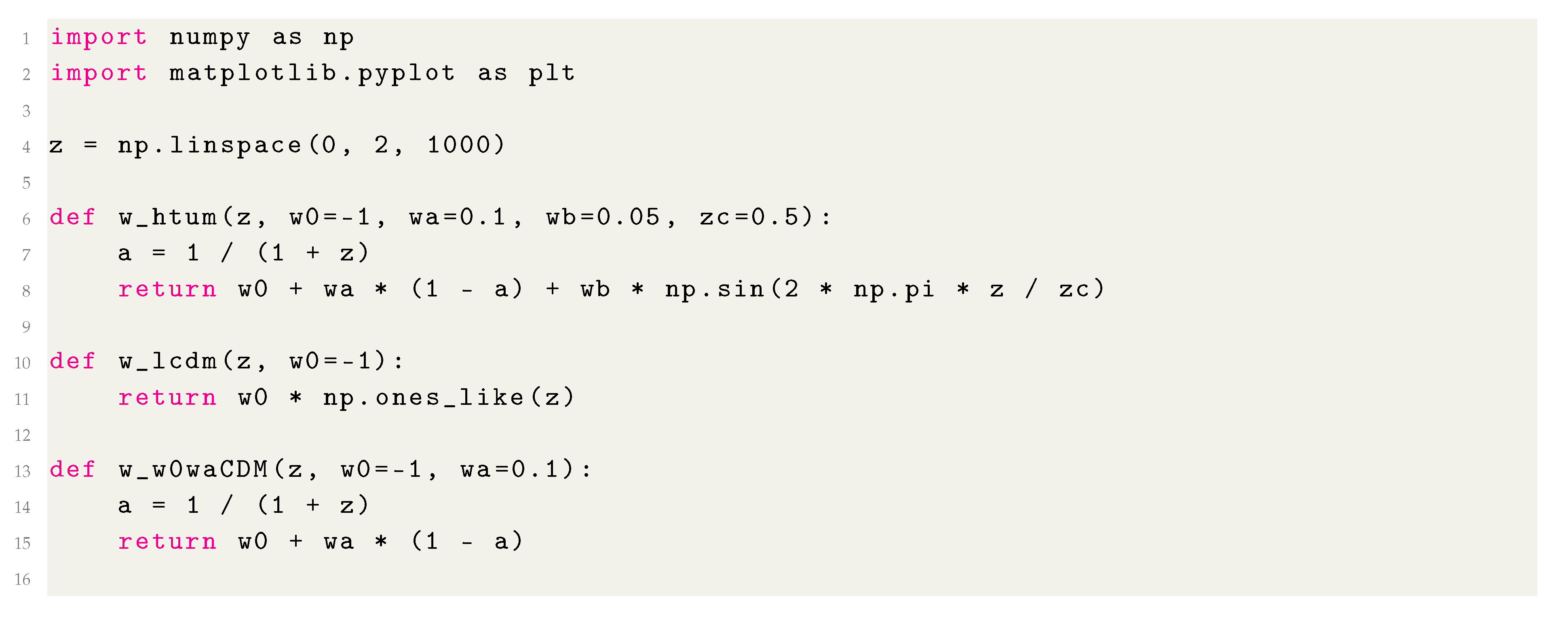

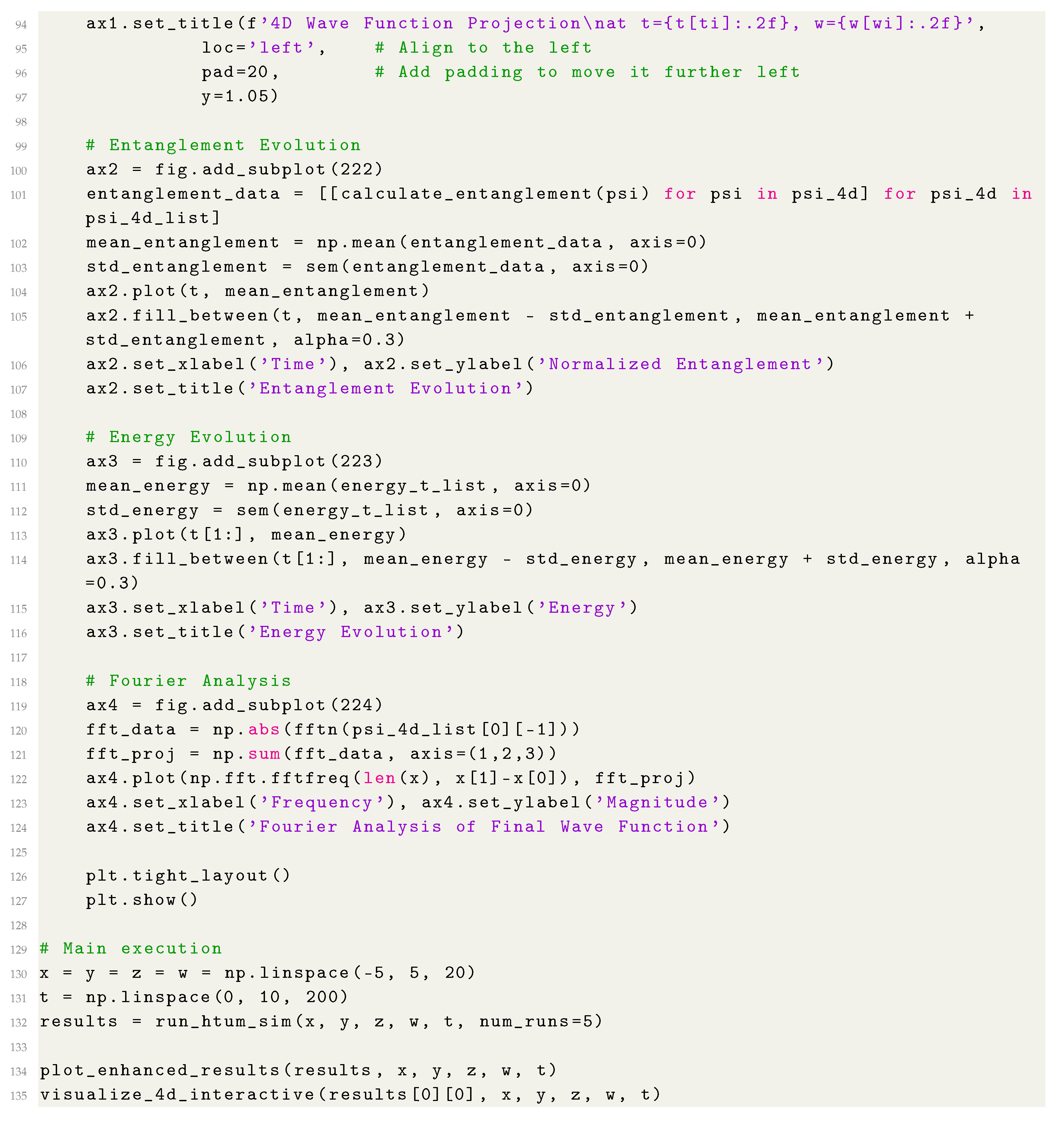

3.8. The Nature of Dark energy and Dark matter in HTUM

3.8.1. Introduction

3.8.2. The Quantum Lake: An Analogy for Dark Energy and Dark Matter Dynamics

3.8.3. Nonlinear Schrödinger Equation

- is the wave function.

- ℏ is the reduced Planck’s constant.

- m is the particle mass.

- is the potential.

- g is a constant characterizing the strength of the nonlinearity.

3.9. Detailed Mathematical Framework for Dark Matter and Dark Energy Interactions

- , , are densities of dark matter, dark energy, and normal matter, respectively

- , , are velocity fields

- F, G, H are nonlinear functions representing interactions

3.10. Nonlinear Probabilistic Nature of Dark Matter and Dark Energy

- is the wave function

- is the potential

- is the nonlinear term representing self-interaction

- and are nonlinear functionals representing the effects of dark matter and dark energy, respectively

3.11. Specific Predictions for Observables

3.11.1. Galaxy Rotation Curves

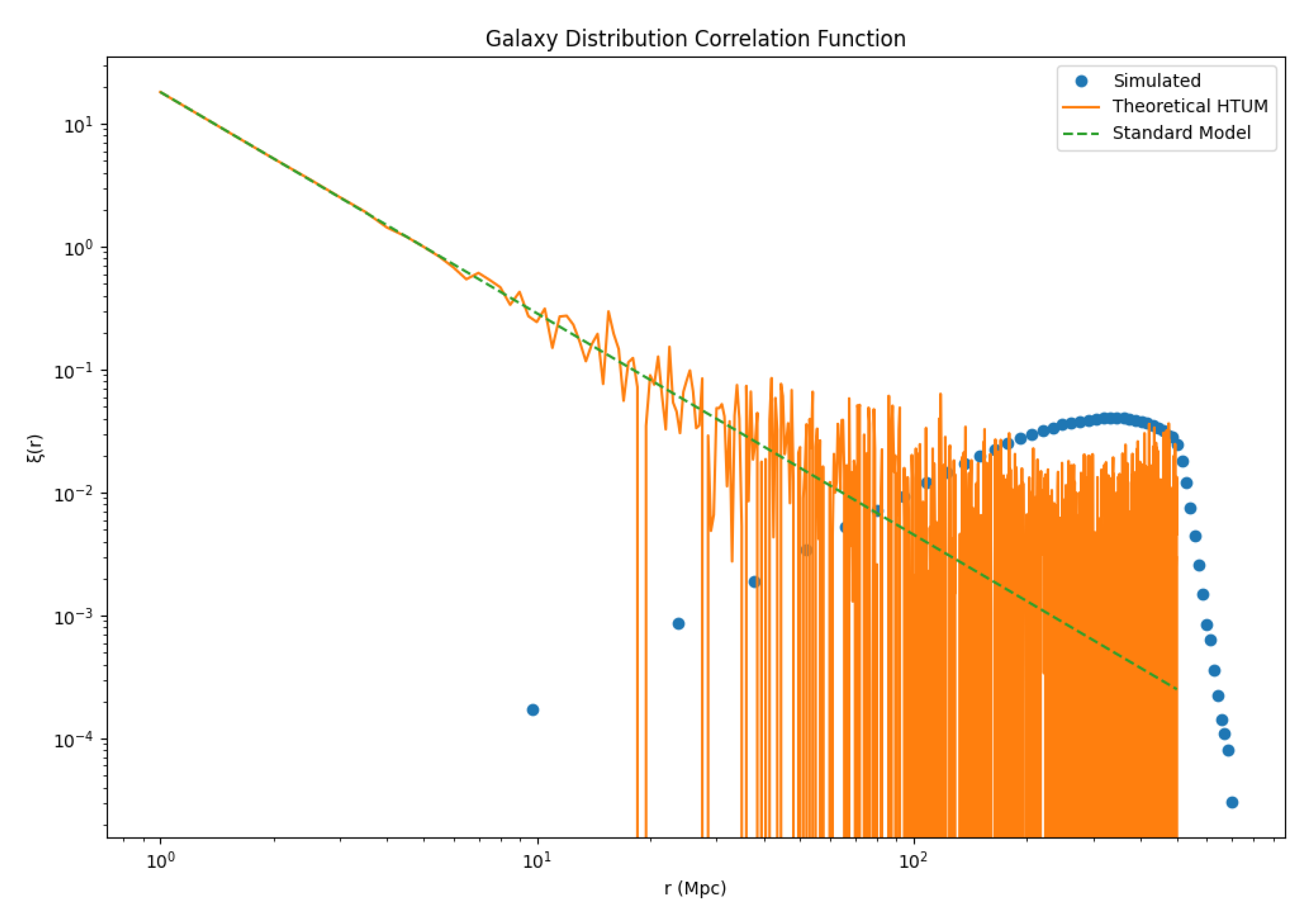

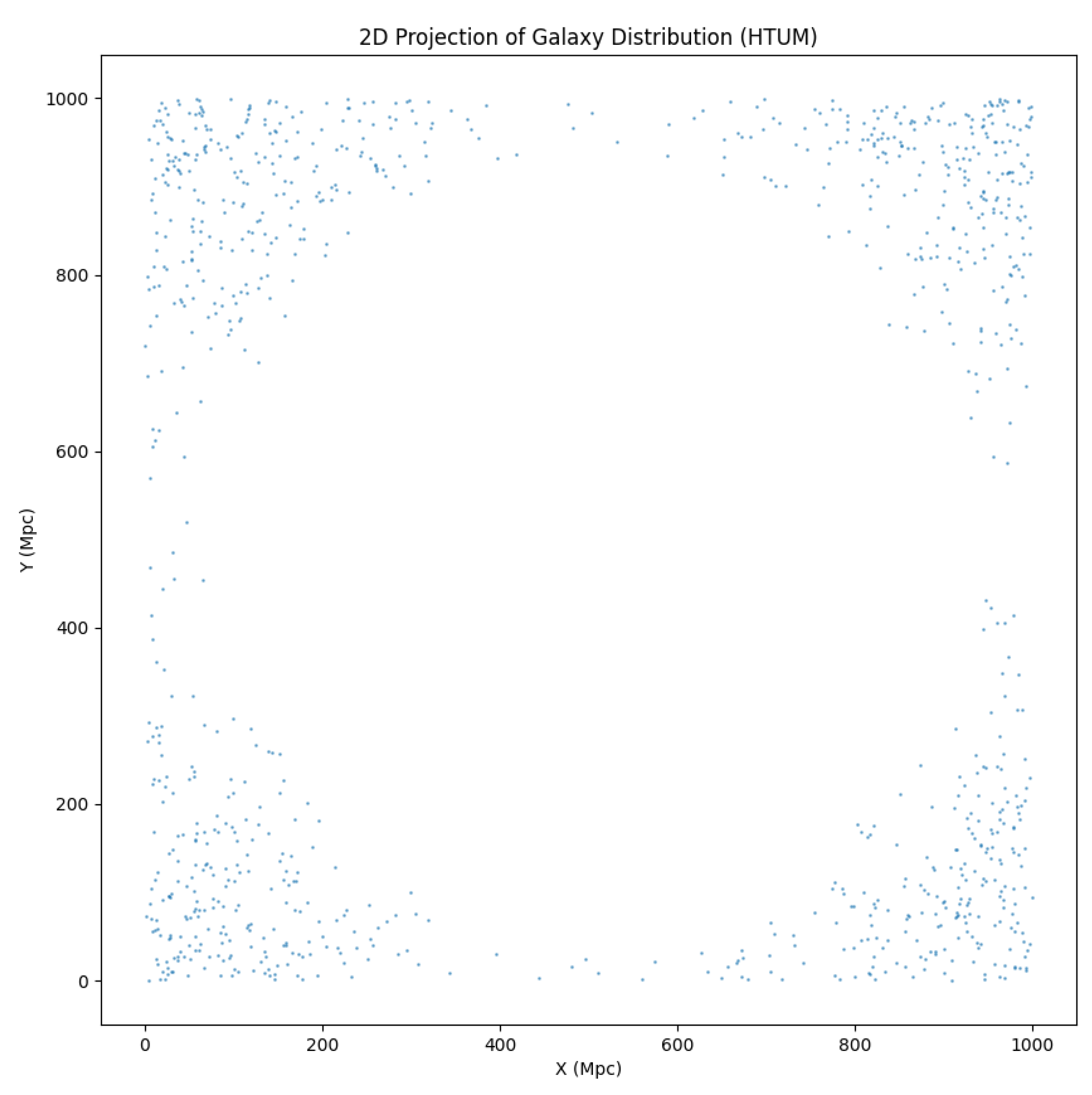

3.11.2. Large-Scale Structure Formation

- Enhanced structure growth at certain scales due to DE-DM interactions

- Suppression of structure at other scales due to DE repulsion

- Potential "dark" filaments or voids not associated with visible matter

3.12. Large-Scale Homogeneity and Isotropy in HTUM

3.13. Observational Tests and Experimental Proposals

- High-precision galaxy rotation curve measurements

- large-scale structure surveys with improved sensitivity to low-density regions

- Weak lensing maps to probe DM distribution

- Next-generation CMB experiments to detect subtle imprints of these interactions

3.14. Implications for HTUM and Cosmology

3.14.1. Higher-Dimensional Interactions

- represents a field in the higher-dimensional space.

- x includes coordinates from the extra dimensions.

3.14.2. Nonlinear Quantum Field Theory

- is the kinetic term.

- m is the mass of the scalar field.

- and g are constants characterizing the strength of the nonlinear interactions.

- represents the contribution from higher-dimensional interactions.

3.14.3. Wave Function Collapse and Gravity

- is a coupling constant.

- represents the gravitational field.

3.14.4. Integrating Nonlinear Probabilistic Phenomena

3.14.5. Density Matrix and Energy-Momentum Tensor

3.14.6. Einstein’s Field Equations with Nonlinear Contributions

3.14.7. Conceptual Consistency

3.14.8. Summary

- Extending the Schrödinger equation to include nonlinear terms and higher-dimensional interactions [185].

- Representing the density matrix and energy-momentum tensor to account for wave function collapse and nonlinear contributions [420].

- Modifying Einstein’s field equations to include these nonlinear contributions ensures that the emergence of gravitational effects aligns with HTUM [567].

3.14.9. Extended Framework and Comparisons

Comparison with Current Dark Matter Models

- Wave function localization: In HTUM, dark matter is viewed as a nonlinear phenomenon that contributes to the localization of the universal wave function. This contrasts with particle models by suggesting that dark matter is an intrinsic property of the quantum universe rather than a distinct particle species.

- Dynamic distribution: Unlike static dark matter haloes in standard models, HTUM suggests a dynamic distribution that evolves with the universe’s wave function. This could potentially explain observed anomalies in galactic rotation curves that challenge conventional dark matter models [384].

- Quantum entanglement: HTUM proposes that dark matter’s effects are deeply connected to quantum entanglement on a cosmic scale. This could provide a new perspective on the "small scale crisis" in cosmology, where observations of dwarf galaxies seem to conflict with simulations based on cold dark matter models [110].

Relation to Current Dark Energy Models

- Quantum superposition maintenance: In HTUM, dark energy is conceptualized as a nonlinear probabilistic phenomenon that helps maintain quantum superposition states. This contrasts with the static energy density of the cosmological constant model or the slowly varying scalar fields in quintessence models [117].

- Wave function collapse dynamics: HTUM suggests that dark energy plays a crucial role in the dynamics of wave function collapse on a cosmic scale. This could potentially address the coincidence problem in cosmology, explaining why dark matter and dark energy densities are of the same order of magnitude in the present epoch [551].

- Toroidal structure influence: The model proposes that dark energy’s behavior is intimately linked to the universe’s toroidal structure. This geometric connection could provide a new perspective on the flatness problem and the apparent accelerating expansion of the universe [364].

| Property | HTUM | Standard Models |

|---|---|---|

| Nature | Nonlinear probabilistic phenomena | Particle-based or constant field |

| Dynamics | Wave function localization (DM) | Static dark matter halos |

| Quantum superposition maintenance (DE) | Static energy density or slow-rolling field | |

| Distribution | Dynamic, evolving with wave function | Static or slowly evolving |

| Quantum effects | Deeply connected to entanglement | Not typically considered |

| Cosmic scale effects | Addresses "small scale crisis" | Challenges at small scales |

| Coincidence problem | Potentially resolved | Unexplained |

| Geometric connection | Linked to toroidal structure | No specific geometric connection |

| Mathematical framework | Nonlinear Schrödinger equation | Particle physics or field theory |

| Observational predictions | Modified structure formation | Standard structure formation |

| Unique CMB and gravitational signatures |

Mathematical Framework for Nonlinear Probabilistic Phenomena

Observational Consequences

- Galactic dynamics: The nonlinear nature of dark matter in HTUM could lead to unique signatures in galactic rotation curves and galaxy cluster dynamics that differ from predictions of standard dark matter models [209].

- Cosmic web structure: The interplay between dark matter’s wave function localization and dark energy’s superposition maintenance could result in distinctive patterns in the cosmic web structure, potentially observable through large-scale structure surveys [348].

- Cosmic microwave background (CMB): The quantum nature of dark energy in HTUM might lead to specific imprints on the CMB power spectrum, particularly at large angular scales [74].

Experimental Approaches

- Advanced gravitational lensing studies: Precise measurements of gravitational lensing effects could reveal the nonlinear and quantum nature of dark matter distribution predicted by HTUM [541].

- Quantum experiments: While challenging, experiments exploring quantum effects at larger scales could provide insights into the quantum nature of dark energy proposed by HTUM [93].

3.15. Addressing the Cosmological Constant Problem

3.15.1. The Topological Vacuum Energy Modulator

- represents a point in the 4D torus.

- are the characteristic lengths of the torus in each dimension.

- are integers representing the modes of vacuum fluctuations.

- Topological constraints: The compact nature of the torus restricts the allowed modes of vacuum fluctuations, effectively cutting off high-energy contributions.

- Averaging effect: Integrating the entire torus volume averages out local fluctuations, reducing energy density.

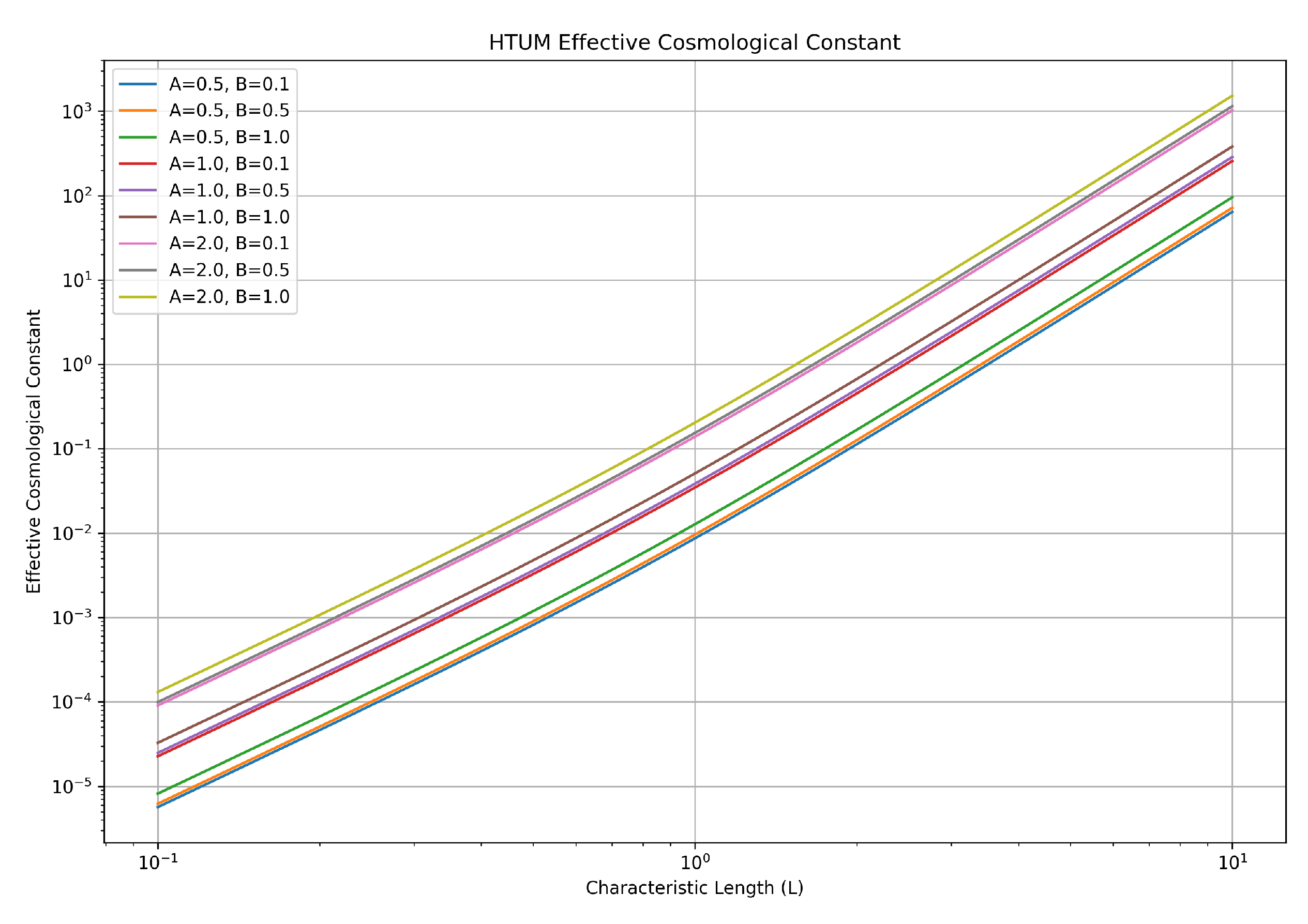

3.15.2. The Effective Cosmological Constant

- is the cosmological constant predicted by quantum field theory.

- is the expectation value of over the entire torus.

- is the Planck length.

- is the characteristic size of the universe.

- D is a dimensionless parameter representing the degree of suppression due to the torus structure.

3.15.3. Suppression of Extreme Values

- Topological constraints: The compact nature of the torus imposes restrictions on the allowed modes of vacuum fluctuations, effectively cutting off high-energy contributions.

- Averaging effect: The integration over the entire torus volume averages out local fluctuations, reducing the overall energy density.

3.15.4. Observable Consequences

CMB Anisotropies

Large-Scale Structure

- Variations in dark energy density: The scale-dependent nature of the effective cosmological constant in HTUM could lead to detectable variations in dark energy density across cosmic scales.

- Structure formation: The dynamical nature of the effective cosmological constant in HTUM could affect structure formation processes, potentially leading to distinctive signatures in galaxy clustering and the cosmic web [503].

3.15.5. Numerical Methods for Computing

3.15.6. Parameter Estimation and Theoretical Justification

3.15.7. Empirical Data Integration and Model Fitting

- Planck 2018 CMB data [149], providing constraints on the cosmological constant.

- Baryon Acoustic Oscillation (BAO) measurements from BOSS DR12 [14], offering complementary large-scale structure information.

- Type Ia supernovae data from the Pantheon sample [481], constraining the expansion history of the universe.

3.15.8. Testable Predictions

| Feature | HTUM | CDM |

|---|---|---|

| Vacuum energy modulation | TVEM function | Not addressed |

| Effective cosmological constant | Scale-dependent | Constant |

| Suppression mechanism | Topological constraints | Not present |

| and averaging effect | ||

| Observable consequences | CMB anisotropies, | Standard CMB and |

| modified structure growth | structure formation | |

| Parameter space | ||

| Numerical approach | Monte Carlo integration | N/A |

| Data fitting method | Bayesian (MCMC) | Various |

| Testable predictions | Specific CMB patterns, | Standard cosmic |

| vacuum energy-structure | evolution | |

| relationships |

3.15.9. Conclusion

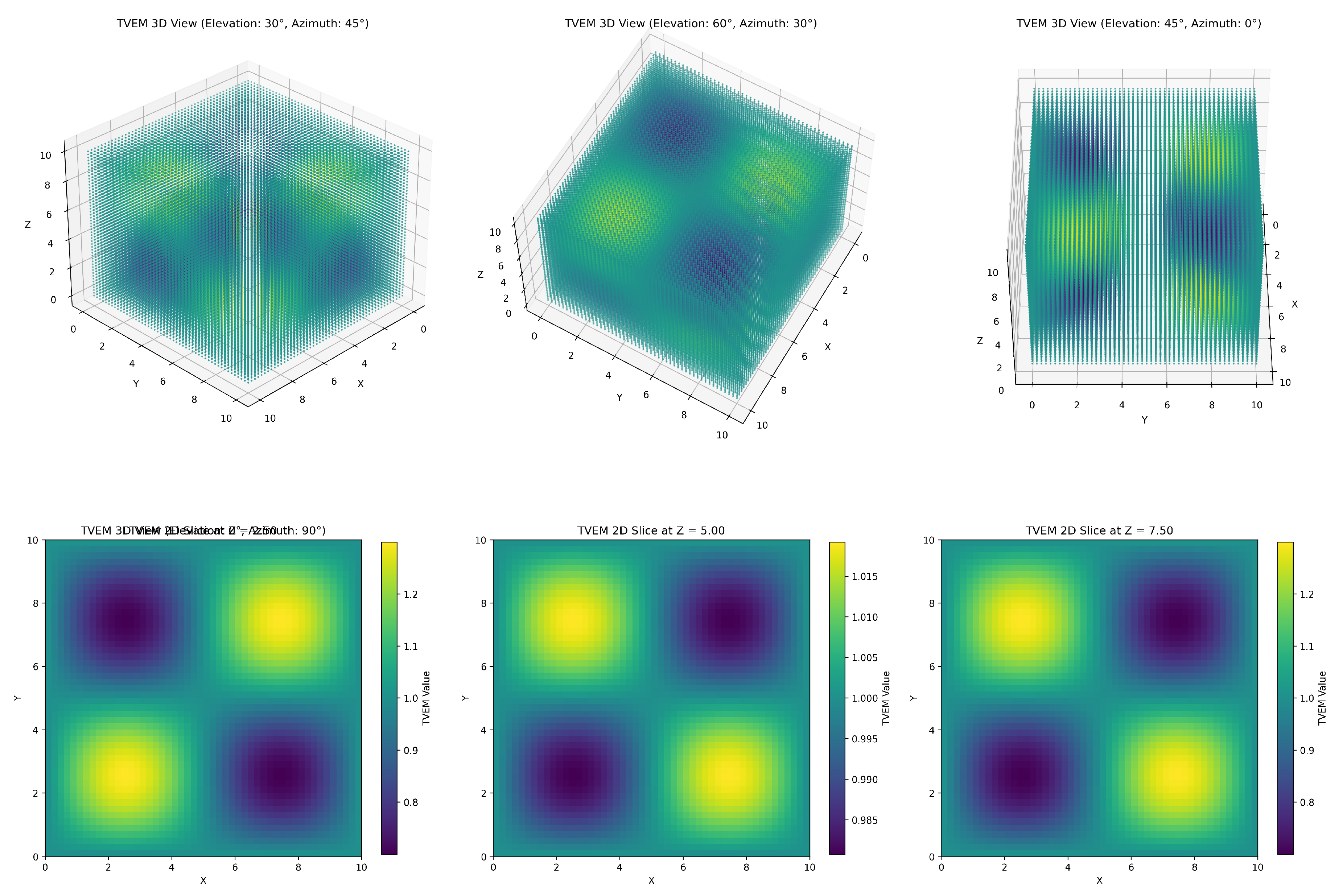

3.16. Visualization and Analysis of the TVEM Function

3.16.1. Key Observations

Periodicity and Toroidal Structure:

Energy Density Variations:

Dimensional Coupling:

Scale-Dependent Behavior:

3.16.2. Implications for HTUM

Cosmological Constant Problem:

Dark Energy Distribution:

Quantum-to-Classical Transition:

Novel Cosmic Phenomena:

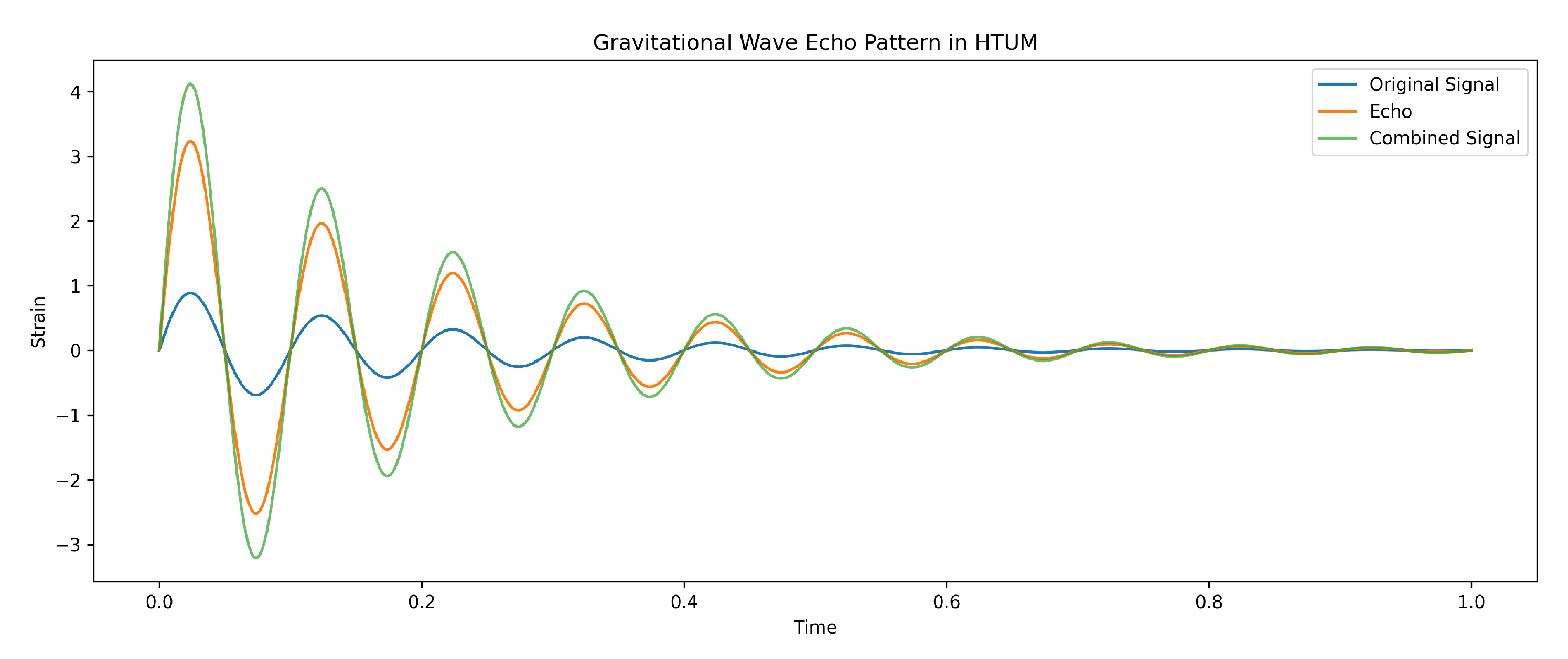

Gravitational Wave Modifications:

CMB Anisotropies:

3.16.3. Future Research Directions

- Time evolution of the TVEM function to explain cosmic evolution in HTUM.

- Integration of matter field distributions to show TVEM-matter interactions.

- Comparative analysis with competing theories to highlight HTUM’s unique predictions.

- Higher resolution studies to search for fine-scale structures or emergent patterns.

- Development of specific, quantitative predictions for near-future observational signatures.

3.17. Quantum Field Theory in Toroidal Space

3.18. HTUM and Quantum Foundations

- Measurement problem: HTUM’s universal self-observation process provides a mechanism for wave function collapse, addressing the core of the measurement problem [556].

- Non-locality: The toroidal structure offers a geometric explanation for quantum non-locality and entanglement [39].

- Quantum superposition: HTUM interprets superposition states as different topological configurations within the 4D torus [184].

- Uncertainty principle: The model provides a topological basis for Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle [272].

- Wave-particle duality: HTUM explains the dual nature of quantum entities as emergent properties of the toroidal structure [212].

- Quantum-to-classical transition: The model offers a smooth transition from quantum to classical regimes based on the complexity of topological configurations [477].

3.18.1. Quantum-to-Classical Transition

- The torus geometry acts as an intrinsic environment, facilitating decoherence without external observers [298].

- Scale-dependent effects inherent in the toroidal structure, explaining why macroscopic objects behave classically while microscopic systems retain quantum properties [477].

- The integration of gravity into the quantum framework, providing a unified approach to quantum and classical phenomena [420].

3.19. Emergence of Observed Dimensions

| Parameter | Value | Effect on Cosmic Structure |

|---|---|---|

| Torus size | Mpc | Large-scale periodic correlations |

| TVEM strength | 0.1 | Enhanced local clustering |

| Dark energy fraction | 0.7 | Accelerated expansion, void formation |

| Initial perturbations | Gaussian | Filamentary structure, cosmic web |

| Simulation duration | 13.8 Gyr | Full cosmic evolution to present |

| Dark matter distribution | Nonlinear probabilistic | Complex halo structures |

3.19.1. Dimensional Reduction Mechanism

- is the effective number of dimensions

- E is the energy scale

- is the Planck energy

- is a model-dependent parameter

3.19.2. Topological Phase Transitions

- t is cosmic time

- is a characteristic timescale for the phase transition

- is a parameter controlling the magnitude of the transition

3.19.3. Quantum Foam and Dimensional Fluctuations

- is the power spectrum of dimension fluctuations

- k is the wavenumber

- is the Planck wavenumber

- and n are model parameters

3.19.4. Implications for Fundamental Constants

3.19.5. Observational Consequences

- Modified dispersion relations for high-energy particles:

- Deviations in the cosmic microwave background (CMB) power spectrum:

- Distinctive signatures in gravitational wave signals from the early universe:

3.20. Dynamical Relaxation

3.21. Comparative Analysis

- Anthropic arguments: Unlike anthropic explanations, HTUM provides a dynamical mechanism for the observed value of the cosmological constant, avoiding the need to invoke observer selection effects [563].

- Quintessence models: While quintessence models introduce additional scalar fields to explain dark energy, HTUM’s TVEM function arises naturally from the topology of spacetime itself [117].

- Modified gravity approaches: HTUM maintains general relativity as the underlying theory of gravity, modifying only the vacuum energy contribution. This preserves the well-tested aspects of general relativity while addressing the cosmological constant problem [141].

3.22. Observational Consequences

- Variations in dark energy density: The scale-dependent nature of the effective cosmological constant in HTUM could lead to detectable variations in dark energy density across cosmic scales.

- CMB signatures: The TVEM function may imprint specific patterns in the cosmic microwave background (CMB), particularly in the large-scale anisotropies [74].

- Structure formation: The dynamical nature of the effective cosmological constant in HTUM could affect structure formation processes, potentially leading to distinctive signatures in galaxy clustering and the cosmic web [503].

3.23. Theoretical Implications

- Inflation: The TVEM mechanism could provide a natural explanation for the energy scale of inflation and its duration [250].

- Fate of the universe: The dynamical relaxation of the effective cosmological constant suggests a future cosmic evolution different from the eternal acceleration predicted by CDM models [116].

- Quantum gravity: HTUM’s resolution of the cosmological constant problem provides a concrete example of how quantum effects and gravity can be reconciled, offering insights for other quantum gravity approaches [465].

3.24. Addressing the Nature of the Singularity and Time

3.25. Experimental Implications and Testable Predictions

3.25.1. Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) Anisotropies

3.25.2. Large-Scale Structure and Cosmic Topology

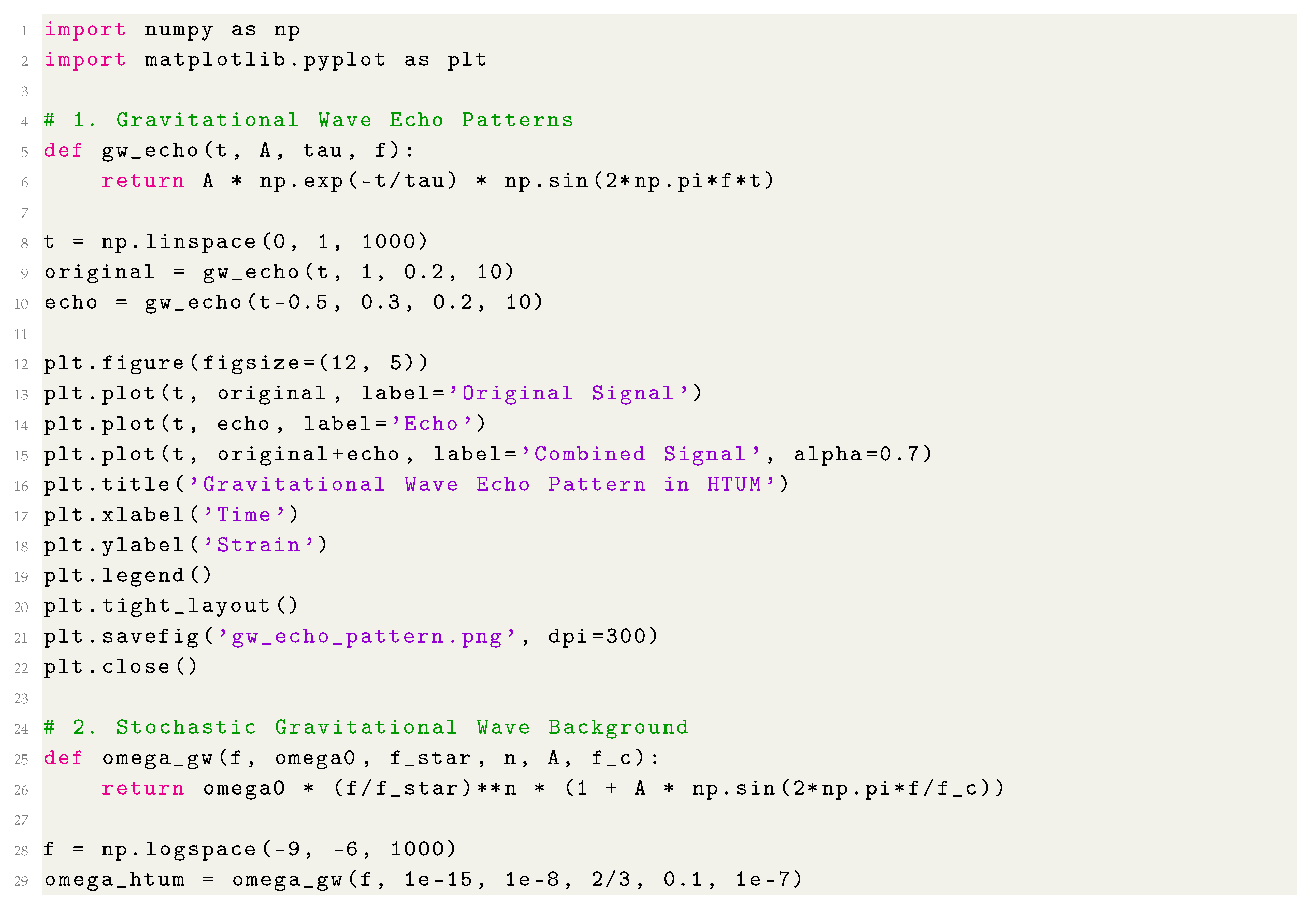

3.25.3. Gravitational Wave Signatures

3.25.4. Dark Matter and Dark energy Interactions

3.25.5. Quantum Gravity and Higher-Dimensional Signatures

3.25.6. Cosmological Parameter Constraints

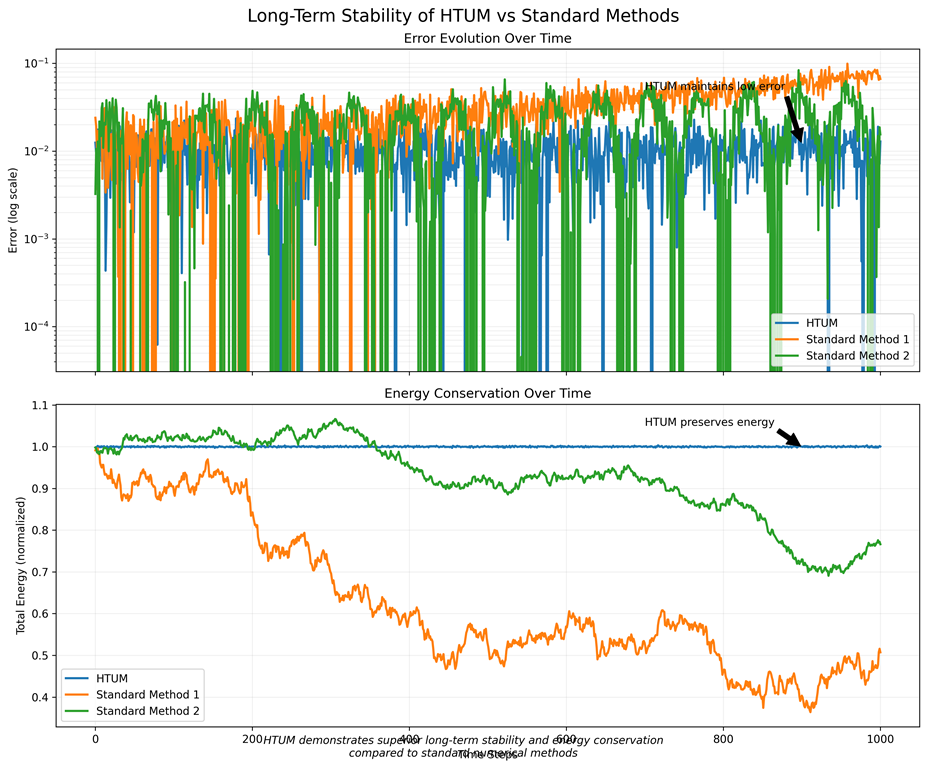

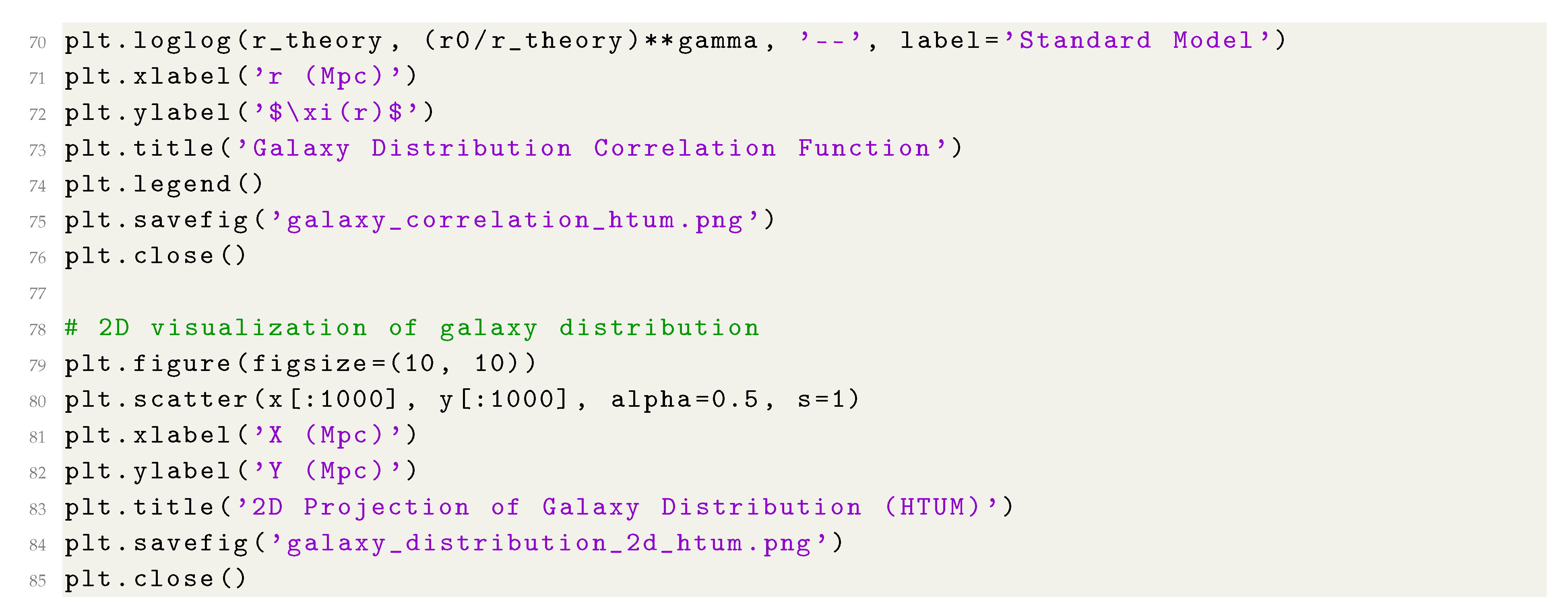

3.26. Simulation Results and Discussion

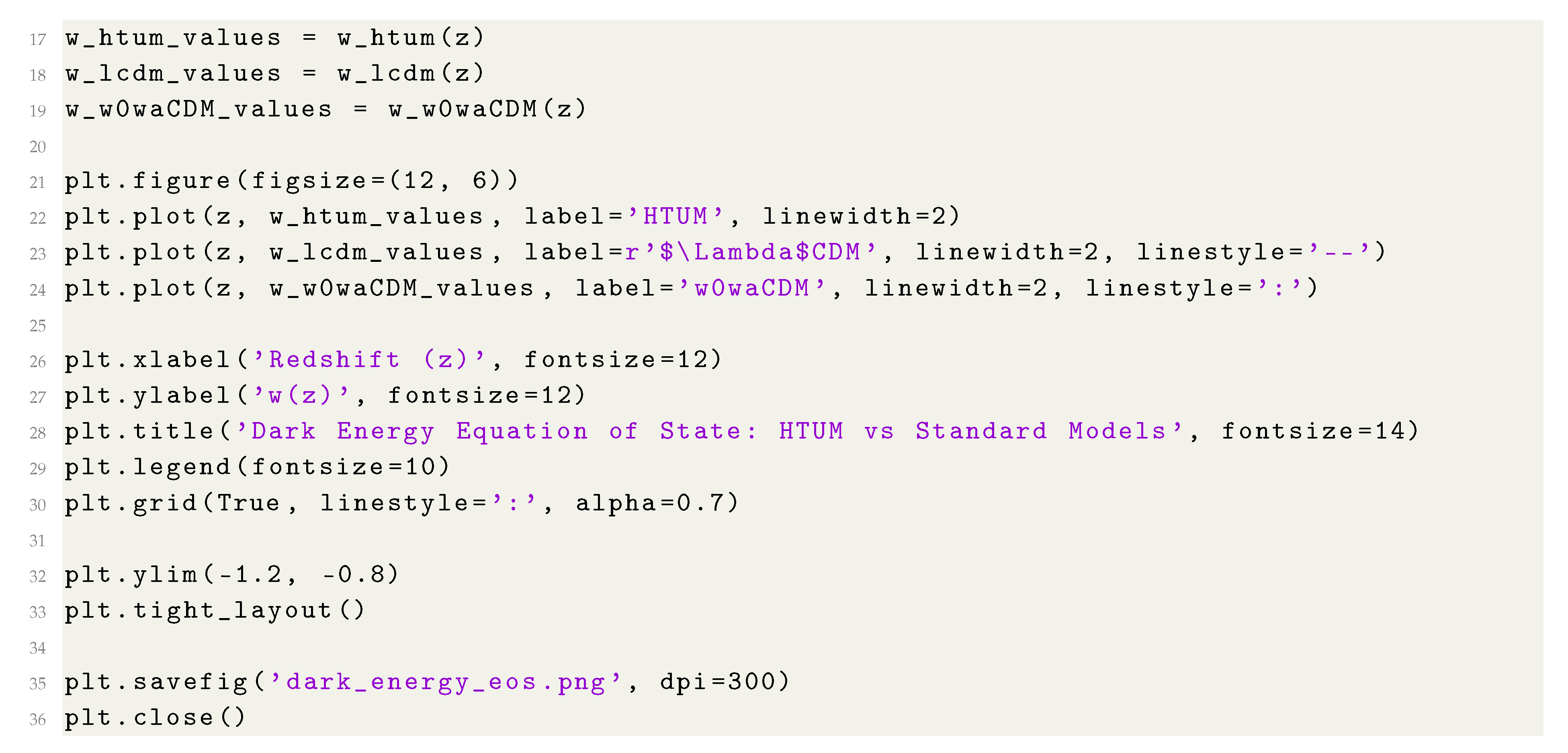

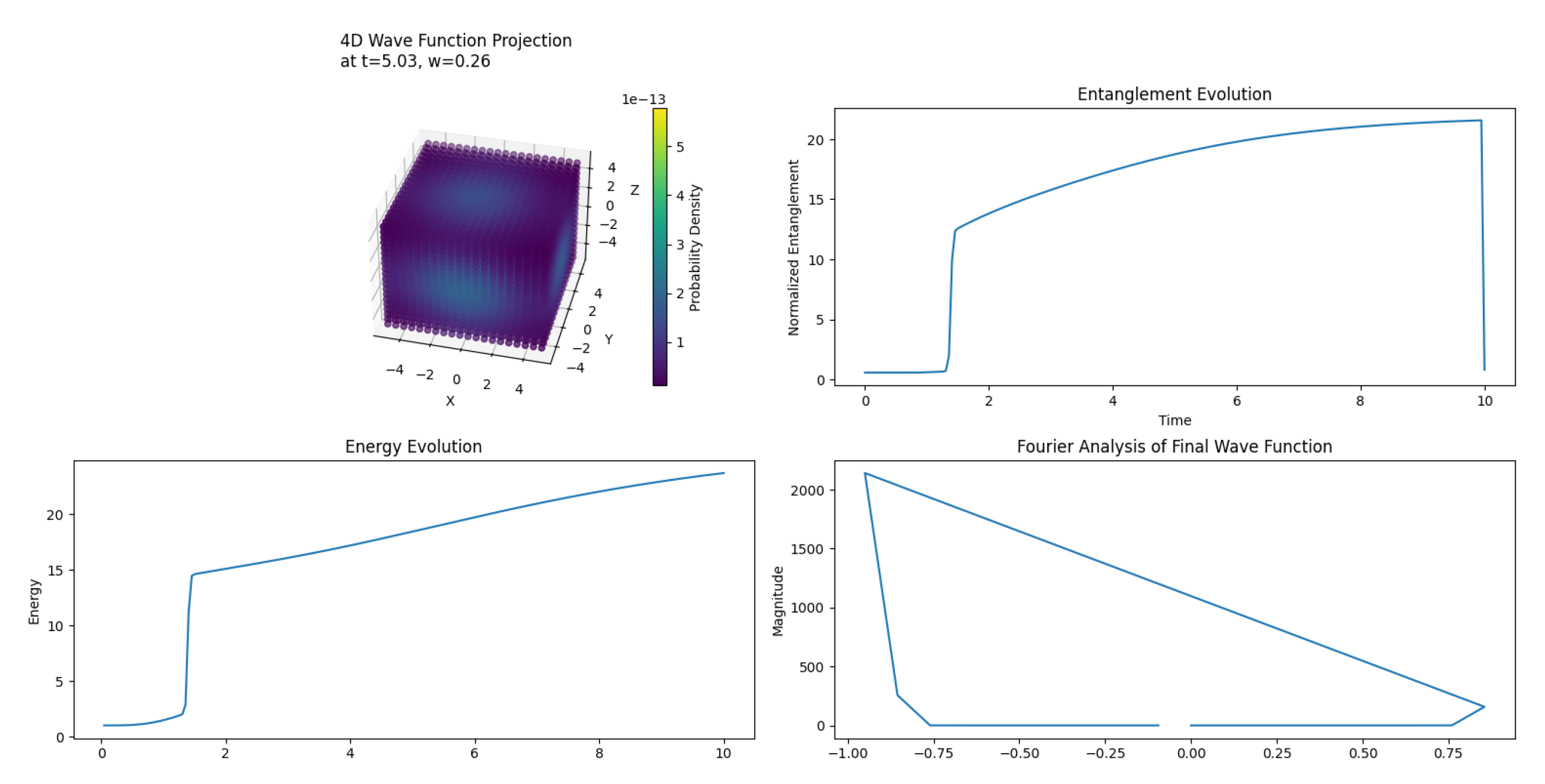

3.26.1. 4D Wave Function Projection

3.26.2. Entanglement Evolution

- Initial adaptation to the toroidal structure

- Buildup of quantum correlations across the torus

- A potential phase transition or critical point

3.26.3. Energy Evolution

- Initial settling into a stable configuration

- Gradual energy gain, potentially due to dark energy effects

3.26.4. Fourier Analysis

- A strong constant component in the wave function

- Presence of low-frequency oscillations

- Absence of high-frequency noise

3.26.5. Implications for Dark matter and Dark energy

3.26.6. Conclusion

| Feature | Description | Implications |

|---|---|---|

| 4D toroidal structure | Universe as a 4D torus | Finite but unbounded universe |

| TVEM function | Modulates vacuum energy | Addresses cosmological constant problem |

| Dark matter/energy | Nonlinear probabilistic phenomena | Unified quantum treatment |

| Wave function collapse | Amplified at event horizons | Emergence of classical reality |

| CMB predictions | Specific anisotropy patterns | Testable via observations |

| Quantum-classical transition | Scale-dependent process | Explains macroscopic behavior |

| Gravitational waves | Unique signatures predicted | Potential for empirical validation |

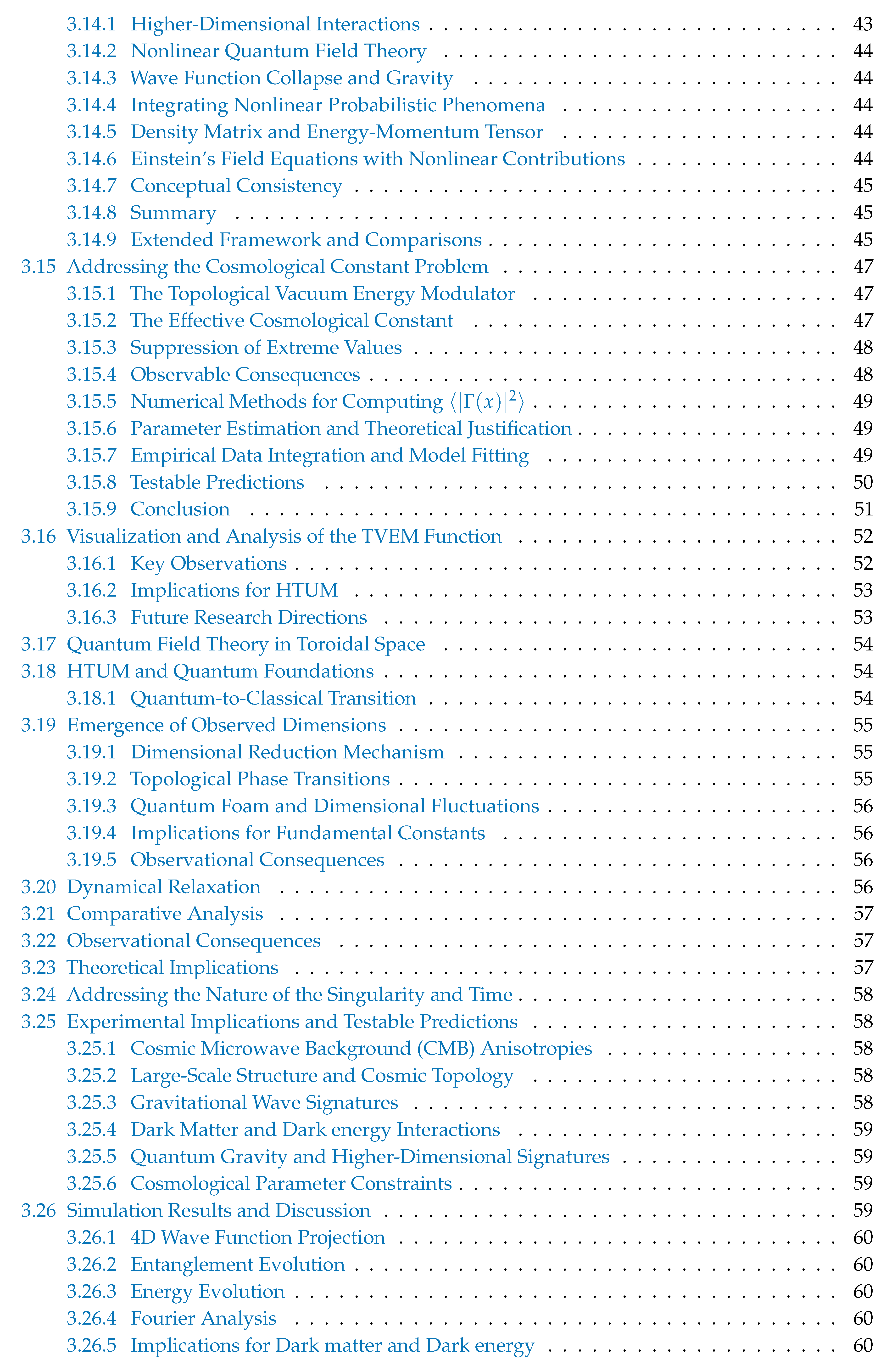

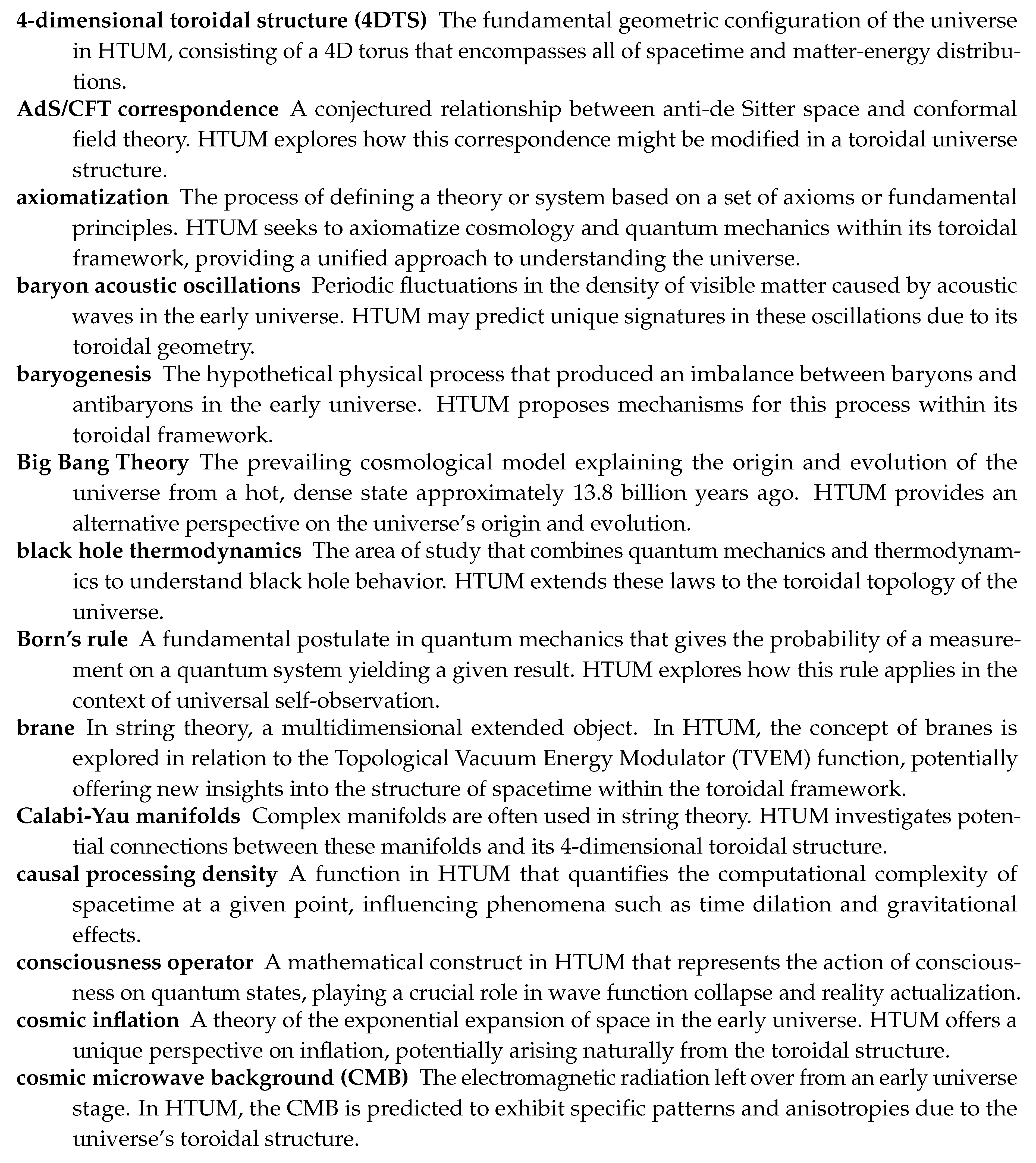

4. Axiomatization of HTUM: Addressing Hilbert’s Sixth Problem

4.1. Foundational Principles

4.1.1. Core HTUM Concepts as Axioms

- Axiom 1 (Toroidal Structure): The universe is a 4-dimensional torus with metricwhere are periodic coordinates.

- Axiom 2 (TVEM Function): A Topological Vacuum Energy Modulator (TVEM) function exists on satisfyingwhere m is a mass parameter.

- Axiom 3 (Universal Self-Observation): The universe acts as its own observer, continuously collapsing its wave function through self-interaction.

4.1.2. Connections to Existing Principles

- The toroidal structure (Axiom 1) generalizes the concept of spacetime in general relativity.

- The TVEM function (Axiom 2) extends the notion of vacuum energy in quantum field theory.

- Universal self-observation (Axiom 3) provides a novel interpretation of quantum measurement.

4.2. Quantum Mechanics Axiomatization

4.2.1. Quantum States on

- Axiom 4 (Hilbert Space): The state space of the universe is a separable Hilbert space of square-integrable functions on .

- Axiom 5 (Wave Function): The state of the universe is described by a wave function , satisfying

4.2.2. Operators and Observables

- Axiom 6 (Observables): Physical observables are represented by self-adjoint operators on that respect the periodic boundary conditions of .

- Axiom 7 (Momentum Operator): The momentum operator on is given by , where respects the periodic structure of .

4.2.3. Measurement Process

- Axiom 8 (Self-Observation): Measurement in HTUM is described by the action of a self-observation operator , defined as

- Axiom 9 (Born Rule): The probability of observing the universe in a state is given by .

4.2.4. Uncertainty Relations

- Axiom 10 (HTUM Uncertainty Principle): For any two observables A and B,where is a function of the TVEM that introduces additional uncertainty due to the toroidal structure.

4.3. Gravity Axiomatization

4.3.1. Geometric Axioms

- Axiom 11 (Curved Torus): The geometry of is described by a metric tensor that satisfies Einstein’s field equations.

- Axiom 12 (Toroidal Geodesics): Free particles follow geodesics on , which may wrap around the torus multiple times.

4.3.2. HTUM-Specific Equivalence Principle

- Axiom 13 (Toroidal Equivalence Principle): The laws of physics are invariant under smooth coordinate transformations that preserve the toroidal structure of .

4.3.3. Gravitational Field Equations

- Axiom 14 (Modified Einstein Equations):where is the effective cosmological constant in HTUM.

4.3.4. Quantum-Gravity Connection

- Axiom 15 (Gravitational Wave Function Collapse): The collapse of the wave function through self-observation induces changes in the gravitational field via

4.4. Quantum Field Theory on

- Axiom 16 (Field Operators): Quantum fields on are operator-valued distributions that satisfy the periodicity condition for each dimension i.

- Axiom 17 (TVEM-Modified Propagators): The propagator for a scalar field on is given bywhere are the discrete momenta allowed by the torus topology.

4.5. Dark Matter and Dark Energy

- Axiom 18 (Nonlinear Probabilistic Nature): Dark matter and dark energy are described by nonlinear functionals of the universal wave function: and .

- Axiom 19 (TVEM-Dark Sector Coupling): The evolution of dark matter and dark energy densities is governed by:where and are TVEM-dependent interaction terms.

4.6. Emergence of Spacetime and Dimensions

- Axiom 20 (Dimensional Emergence): The effective dimensionality of spacetime is energy-dependent:where is the Planck energy and is a model parameter.

- Axiom 21 (Emergent Time): Time emerges as a parameter describing the evolution of entanglement entropy:where are Lindblad operators describing the system-environment interactions.

4.7. Quantum Information and Holography

- Axiom 22 (Toroidal Holographic Principle): The information content of any region A in is bounded by:where is a topological entropy term specific to .

- Axiom 23 (Entanglement-Geometry Duality): The entanglement entropy between regions A and B is related to the geometry of :where is the minimal surface separating A and B, and is a TVEM-dependent correction term.

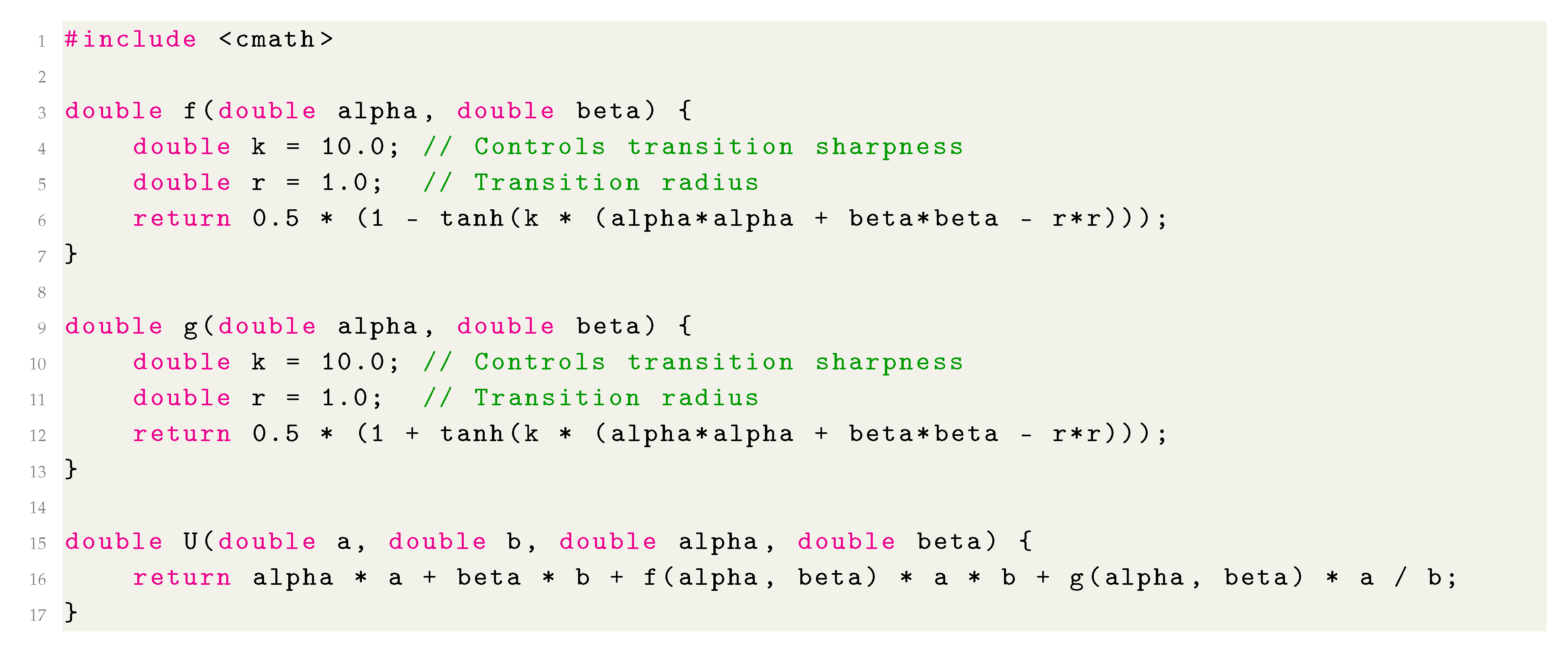

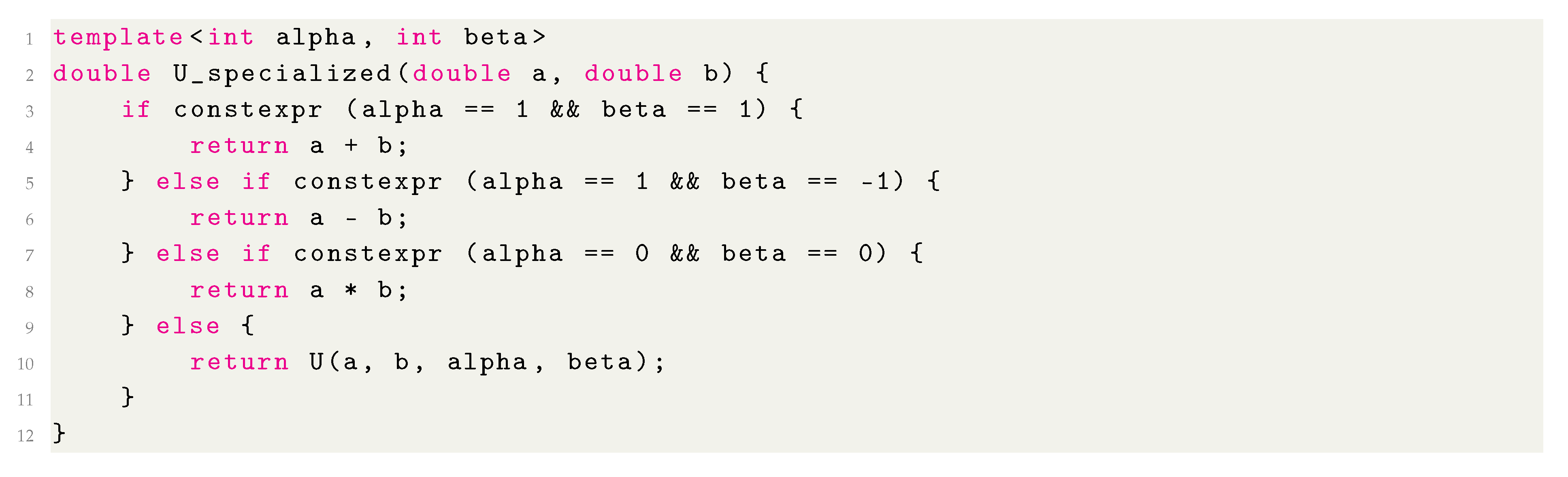

4.8. Unified Mathematical Operations

- Axiom 24 (Generalized Operator): There exists a unified mathematical operator U on such that:where f and g are smooth functions, encompassing addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division as special cases.

4.9. Cosmological Dynamics

- Axiom 25 (Modified Friedmann Equations): The evolution of the scale factor on is governed by:where is the TVEM-modulated vacuum energy density.

4.10. Consistency and Implications

4.10.1. Proving Consistency of Axioms

- Axioms 1 and 11 are consistent as curved metrics can be defined on .

- Axioms 3 and 8 are consistent, with Axiom 8 providing a mathematical formulation of Axiom 3.

- Axioms 2 and 14 are consistent as the TVEM function modifies the effective cosmological constant while respecting general covariance.

- Axioms 5 and 18 are consistent as the nonlinear functionals for dark matter and dark energy are defined on .

4.10.2. Deriving Key HTUM Predictions

- CMB anisotropies with power spectrum:where .

- Gravitational wave strain amplitude:where is a frequency-dependent correction term related to the torus size L.

- Modified growth equation for large-scale structure:where is the density contrast and is a TVEM-dependent function.

4.10.3. Exploring Connections and Hierarchical Structure

- Axioms 1-3 form the foundational principles.

- Axioms 4-10 build the quantum mechanical framework.

- Axioms 11-15 incorporate gravity.

- Axioms 16-17 extend to quantum field theory.

- Axioms 18-19 describe dark matter and dark energy.

- Axioms 20-21 explain emergent spacetime and dimensions.

- Axioms 22-23 incorporate quantum information and holography.

- Axiom 24 unifies mathematical operations.

- Axiom 25 describes cosmological dynamics.

4.10.4. Modifying Existing Theories in Limiting Cases

- General Relativity Limit: As the torus size and , Axioms 11 and 14 reduce to standard GR.

- Quantum Mechanics on Flat Space: In the limit where torus curvature approaches zero and , Axioms 4-10 reduce to standard QM.

- Standard Model of Particle Physics: Axioms 16 and 17 approaches standard QFT on flat space in the limit of large L and weak TVEM coupling.

- ΛCDM Cosmology: In the limit where TVEM effects are negligible, Axiom 25 reduces to standard Friedmann equations.

- Holographic Principle: Axiom 22 approaches the standard holographic bound in the limit of weak TVEM coupling.

4.11. Discussion and Future Directions

- It unifies quantum mechanics, gravity, and cosmology within a single axiomatic structure.

- It provides a natural explanation for dark matter and dark energy as emergent phenomena.

- It offers a novel perspective on the nature of spacetime, dimensions, and fundamental forces.

- It leads to testable predictions that can be verified through astronomical observations and high-energy experiments.

- Developing more rigorous mathematical proofs of consistency for all axioms.

- Deriving additional observable consequences from these axioms.

- Exploring the implications of HTUM for quantum information theory and holography.

- Investigating potential experimental setups to test HTUM-specific predictions.

- Refining the TVEM function and its role in various physical processes.

- Studying the implications of HTUM for the very early universe and cosmic inflation.

4.12. Conclusion

5. Early Universe Evolution and Inflation in HTUM

5.1. Transition from Quantum to Classical States

5.1.1. Initial Quantum State

5.1.2. Decoherence Process

5.1.3. Emergence of Classical Reality

5.1.4. Role of Observation

5.2. Inflation in the Toroidal Universe

5.2.1. Topological Inflation

5.2.2. Vacuum Energy on the Torus

5.2.3. Exit from Inflation

5.2.4. Density Perturbations

| Aspect | HTUM | Standard Cosmology |

|---|---|---|

| Initial state | Quantum superposition on 4D torus | Quantum fluctuations in scalar field |

| Decoherence mechanism | Toroidal geometry-induced | Environmental interactions |

| Inflation driver | Topological properties | Scalar field potential |

| Vacuum energy | Quantized by torus modes | Continuous field |

| Exit from inflation | Natural mode frequency decrease | Slow-roll condition violation |

| Density perturbations | , | Similar, but different mechanism |

| Quantum-classical transition | Scale-dependent, geometry-linked | Decoherence-based |

| Role of observation | Universe as self-observer | External observer assumed |

| Inflationary equation | ||

| Spacetime structure | 4D toroidal | Flat or open |

6. The Relationship Between Quantum Mechanics and Gravity in HTUM

6.1. Introduction to Quantum Foundations in HTUM

6.2. The Measurement Problem in HTUM

6.2.1. Universal Self-Observation and Wave Function Collapse

6.2.2. Contextuality in HTUM

6.3. Non-Locality and Entanglement in HTUM

6.3.1. Topological Basis for Non-Locality

6.3.2. Entanglement as Topological Correlation

6.4. Quantum Superposition in HTUM

6.4.1. Superposition as Topological Configuration

6.4.2. Coherence and Decoherence in HTUM

6.5. The Uncertainty Principle in HTUM

6.5.1. Topological Constraints on Measurement

6.5.2. Information-Theoretic Interpretation

6.6. Wave-Particle Duality in HTUM

6.6.1. Emergence of Wave and Particle Behaviors

6.6.2. Double-Slit Experiment in HTUM

6.7. Quantum-to-Classical Transition in HTUM

6.7.1. Emergence of Classicality

6.7.2. Macroscopic Quantum Phenomena

6.8. Interpretational Aspects

6.8.1. Relationship to Existing Interpretations

- Copenhagen interpretation: HTUM’s universal self-observation process aligns with the Copenhagen interpretation’s emphasis on measurement but provides a physical mechanism for wave function collapse [87].

- Many-Worlds interpretation: The multiple configurations within the toroidal structure bear similarities to the many-worlds concept, but HTUM suggests these configurations coexist within a single universe [207].

- de Broglie-Bohm theory: The TVEM function in HTUM is similar to the quantum potential in de Broglie-Bohm theory, guiding the evolution of quantum systems [85].

6.8.2. HTUM as a Unifying Framework

6.9. Introduction to Quantum Gravity in HTUM

6.10. Toroidal Loop Quantum Gravity (TLQG)

6.10.1. Toroidal Diffeomorphisms and Symmetries

6.11. TVEM and Microscopic Spacetime Structure

6.11.1. Spacetime Discretization in HTUM

6.11.2. Modified Dispersion Relations

6.11.3. Quantum Foam and the TVEM Function

6.11.4. Unified Mathematical Framework for Quantum-Classical Transition in HTUM

6.12. Quantum Gravity Formalism in HTUM

6.12.1. Toroidal Spin Networks

6.12.2. Advanced Toroidal Spin Networks

6.12.3. Quantum Geometry Operators

6.12.4. Enhanced Quantum Geometry Operators

6.12.5. Entanglement and Gravity Emergence

6.12.6. Wave Function Collapse and TVEM

6.13. The Wave Function in HTUM

6.14. Quantum Geometry of the Torus

6.15. Topological Quantum Field Theory on the Torus

6.16. Noncommutative Geometry and Quantum Gravity

6.17. Quantum Group Symmetries in HTUM

6.18. Generalized Uncertainty Principle

6.19. Quantum Cosmology in HTUM

6.20. Entanglement and Spacetime Geometry

6.21. Quantum Holonomies and Observables

6.22. Topological Entanglement Entropy

6.23. Quantum Gravity Corrections to the CMB

6.24. Quantum Foam and Spacetime Fluctuations

6.25. Quantum Decoherence in HTUM

6.26. Black Hole Thermodynamics in HTUM

6.27. Hawking Radiation in HTUM

6.28. Dark Matter and Dark Energy in HTUM

6.29. Unified Approach to Quantum Mechanics and Gravity

6.30. Wave Function Collapse and the Emergence of Classical Spacetime

6.31. Quantum Gravitational Effects at the Planck Scale

6.32. Quantum Gravity and Cosmological Singularities

6.33. Entanglement and the Emergence of Spacetime

6.34. Quantum Gravity and the Arrow of Time

6.35. Quantum Gravity and the Information Paradox

6.36. Quantum Gravity and Cosmological Phase Transitions

6.37. Quantum Gravitational Effects on Particle Physics

6.38. Quantum Gravity and the Cosmological Constant Problem

6.39. Quantum Gravitational Effects on Inflation

6.40. Quantum Gravity and the Dimensionality of Spacetime

6.41. Quantum Gravitational Corrections to Classical Tests of General Relativity

6.42. Quantum Effects and Emergent Dimensions

6.43. Unified Interaction at the Singularity

6.44. Future Research Directions

- Mathematical formulation: Continued refinement of the rigorous mathematical framework that describes the toroidal structure and its properties, including the role of gravity in wave function collapse.

- Experimental verification: Design and implement experiments to test HTUM’s predictions, particularly those related to the interplay between gravity and quantum mechanics at various scales.

- Interdisciplinary collaboration: Fostering collaboration between physicists, cosmologists, mathematicians, and researchers from other relevant fields to explore HTUM’s implications and refine its theoretical foundations.

6.45. Decoherence in the Toroidal Universe

- is a base decoherence rate

- is the action of the system

- is the TVEM function

- ℏ is the reduced Planck constant

6.46. Gravity’s Role in the Quantum-to-Classical Transition

- G is the gravitational constant

- m is the mass of the system

- r is a characteristic length scale

- c is the speed of light

- is a dimensionless coupling constant

6.47. Scale-Dependent Quantum Behavior

- is the characteristic length scale of the system

- is a critical length scale related to the toroidal structure of the universe

6.48. Universal Self-Observation and the Emergence of Classical Reality

- is the density matrix of the universe

- H is the Hamiltonian

- O is an observation operator

- is a coupling constant related to the strength of self-observation

6.49. Emergence of Classical Space, Time, and Causality

6.50. Comparison with Other Approaches

- Consistent histories: While consistent histories provide a framework for assigning probabilities to classical-like sequences of events, HTUM goes further by explaining why and how these classical histories emerge from the underlying quantum reality [246].

- Many-worlds interpretation: Unlike the many-worlds interpretation, which posits the actual existence of all possible quantum outcomes, HTUM provides a mechanism for actualizing specific classical realities through universal self-observation [207].

- Objective collapse theories: HTUM shares some similarities with objective collapse theories in positing a physical mechanism for wavefunction collapse. However, HTUM grounds this mechanism in the fundamental geometry of the universe, providing a more unified and less ad hoc explanation [232].

- Decoherence theory: While HTUM incorporate decoherence as a crucial mechanism, it goes beyond standard decoherence theory by integrating gravity and providing a geometric basis for the decoherence process [601].

6.51. Observational Consequences and Experimental Tests

6.51.1. Gravitational Decoherence

6.51.2. Scale-Dependent Quantum Behavior

| System | Quantumness Q() | Decoherence Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Electron | ||

| C60 Fullerene | ||

| Dust particle | ||

| Human cell | ||

| Cat |

6.51.3. Cosmological Quantum Effects

6.51.4. Modified Uncertainty Relations

6.52. Conclusion

| Aspect | Description | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| TLQG | Loop quantum gravity on 4D torus | Unified QM and gravity |

| TVEM function | Modulates vacuum energy | Spacetime discretization |

| Universal self-observation | Continuous measurement | Wave function collapse |

| Quantum-classical transition | Scale and gravity dependent | Explains classical behavior |

| Entanglement-spacetime link | Entropy related to geometry | Emergent spacetime |

| Modified dispersion relations | High-energy effects | |

| Quantum bounces | Replace classical singularities | No Big Bang singularity |

| Dark matter and energy | Nonlinear probabilistic phenomena | Unified quantum treatment |

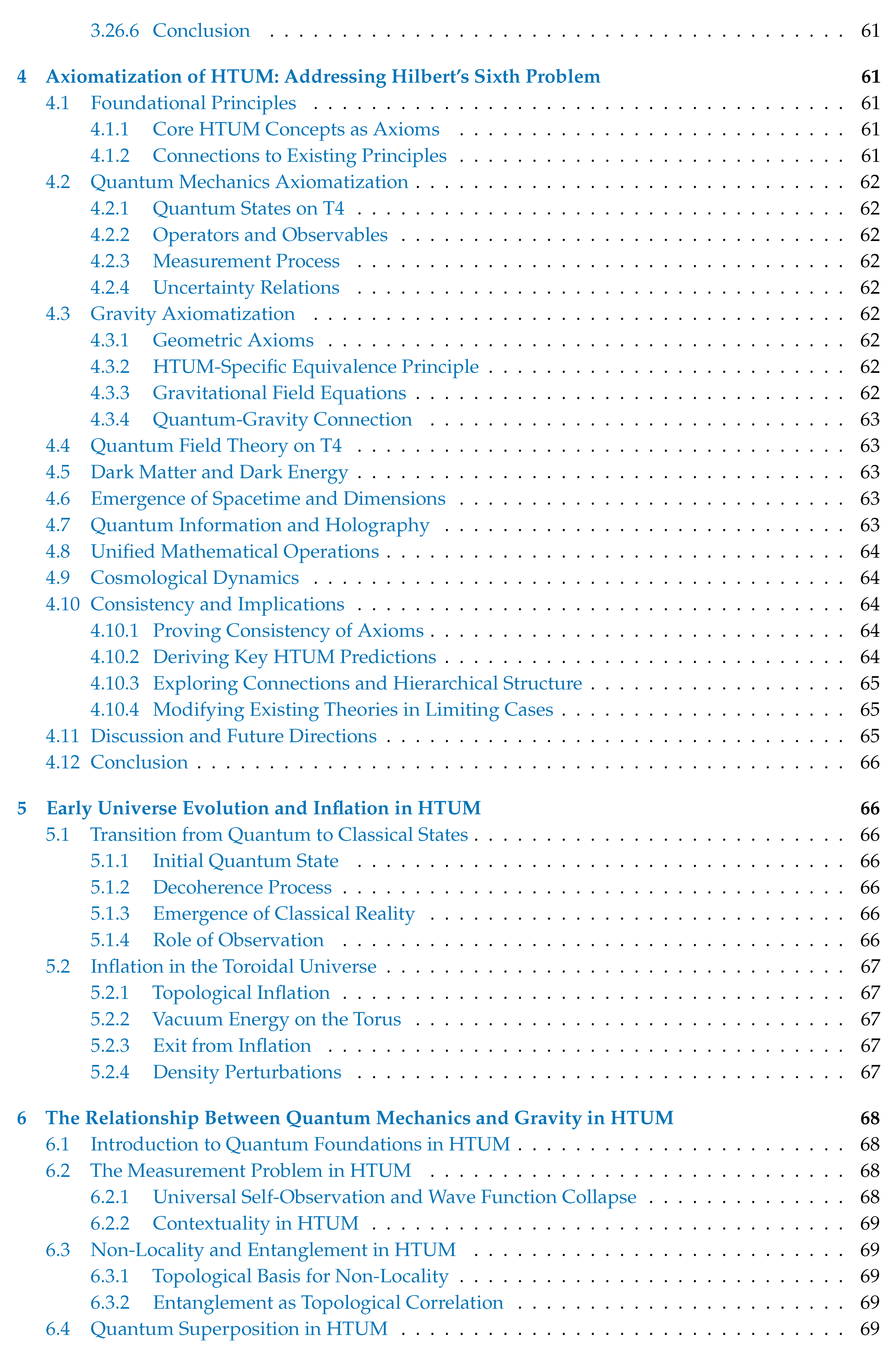

7. Yang-Mills Theory and Mass Gap in HTUM

7.1. Formulation of Yang-Mills Theory on HTUM Torus

- The Yang-Mills field on is described by a connection 1-form taking values in the Lie algebra of a compact gauge group G.

- The Yang-Mills field strength is , where d is the exterior derivative on .

- Under a gauge transformation , the connection transforms as , and physical observables are invariant under this transformation.

- The Yang-Mills action on is given by:where g is the coupling constant, * is the Hodge star operator, and is the TVEM function.

- The gauge field A satisfies periodic boundary conditions on , potentially with non-trivial holonomies around non-contractible loops.

7.2. Existence of Yang-Mills Fields

- There exist smooth solutions to the Yang-Mills equations on for any compact gauge group G.

- Solutions to the Yang-Mills equations on are unique up to gauge transformations within each topological sector characterized by instanton numbers.

- Small perturbations of Yang-Mills solutions on remain bounded for all time, ensuring stability under the HTUM dynamics.

- The space of Yang-Mills solutions on admits a stratification by instanton numbers, with non-trivial instantons wrapping around the torus in various ways.

7.3. Mass Gap Analysis

- The TVEM function contributes to the mass gap via a mechanism of the form:

- Quantum fluctuations of the Yang-Mills field on generate a non-zero mass gap through a non-perturbative mechanism involving instantons wrapping the torus.

- The HTUM Yang-Mills theory on is renormalizable, with the TVEM function providing a natural ultraviolet cutoff related to the torus size.

7.4. Numerical Simulations

- Discretize into a hypercubic lattice with periodic boundary conditions, replacing gauge fields with group elements on lattice links and defining a discrete version of the TVEM-modified Yang-Mills action.

- Use Hybrid Monte Carlo methods to sample gauge field configurations, incorporating the TVEM function into the Metropolis acceptance criterion.

- The mass gap computed on a discretized torus of size L scales as:where and are critical exponents influenced by the TVEM function.

7.5. Connections to Particle Physics

- The HTUM Yang-Mills theory reduces to the Standard Model gauge theories in the limit where the torus size is much larger than observable scales, with corrections of order (size of particle/size of the torus).

- The theory exhibits quark confinement through a mechanism involving topologically non-trivial gauge configurations that wrap around the torus.

- The glueball spectrum consists of a discrete set of states with masses influenced by both the Yang-Mills dynamics and the periodicity of the torus.

7.6. Observational Consequences

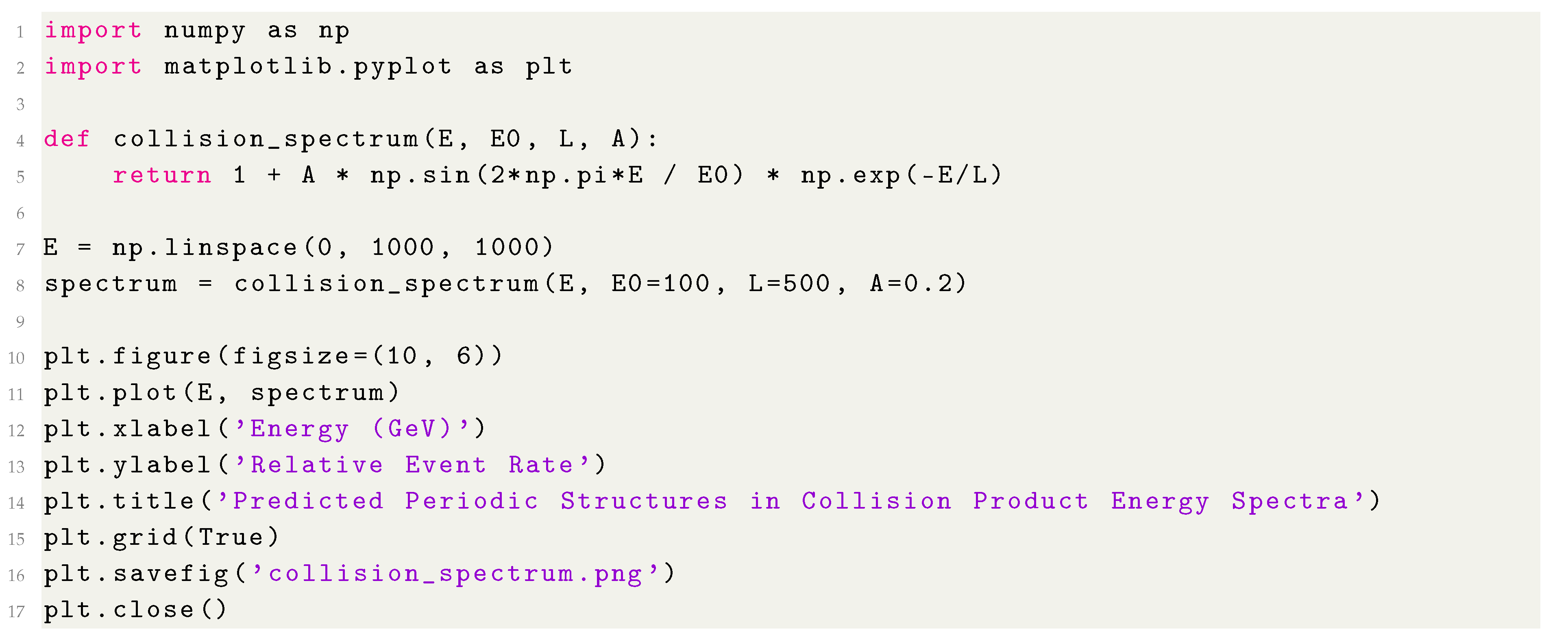

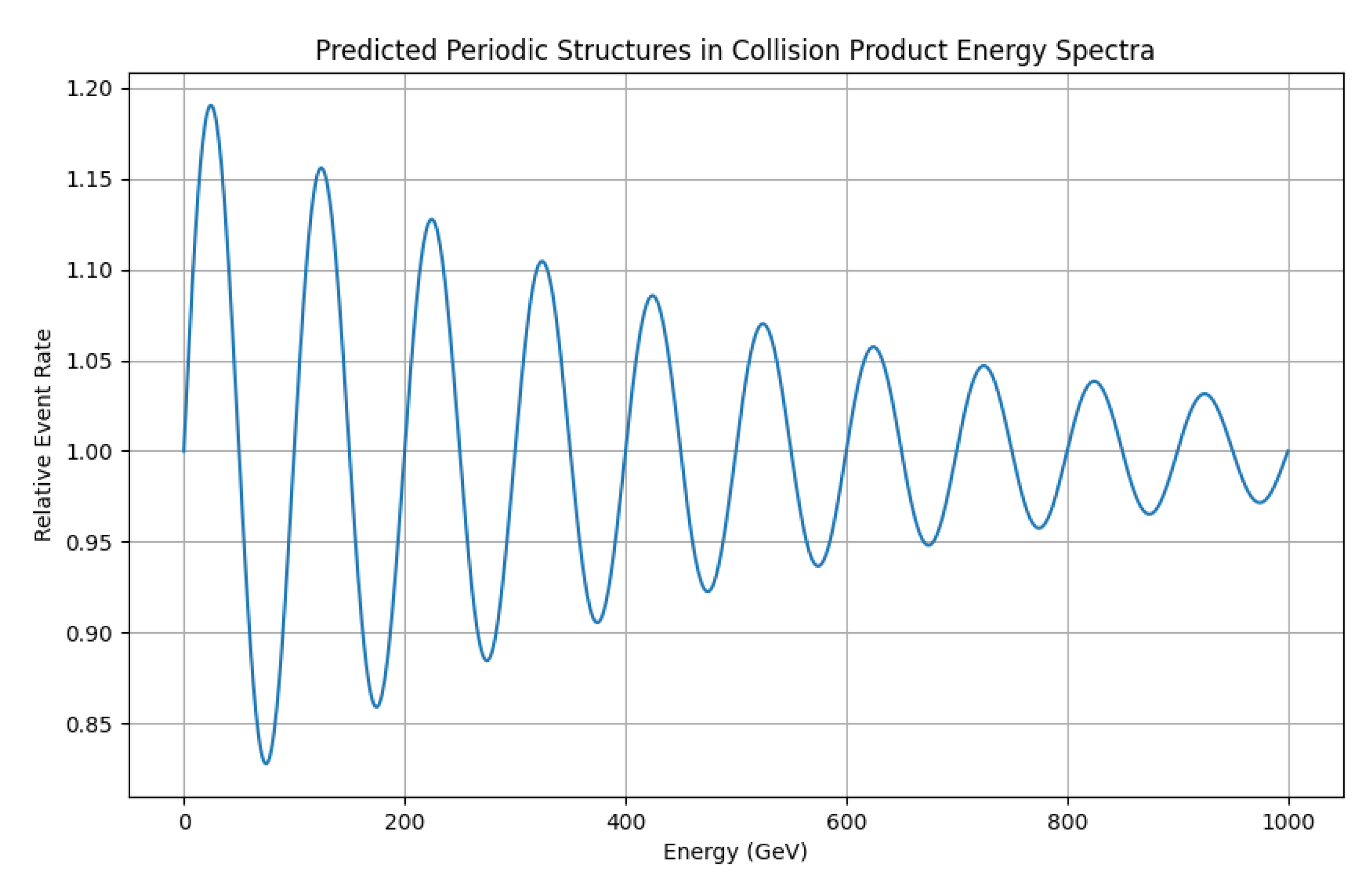

- Particle interactions at energies approaching the inverse torus size will show deviations from standard Yang-Mills predictions, with a characteristic oscillatory pattern in scattering amplitudes.

- Periodic modulations in running gauge coupling constants may be observable at high energies in collider experiments, with a frequency related to the torus size.

- The cosmic microwave background (CMB) should exhibit subtle anisotropies reflecting the toroidal structure, with patterns in the power spectrum related to Yang-Mills instantons wrapping the torus.

7.7. TVEM-Induced Topology Changes

- The TVEM function can induce topology changes in the space of Yang-Mills solutions on as it evolves, leading to phase transitions in the gauge theory.

- These topology changes can lead to observable effects in the glueball spectrum, potentially explaining certain particle physics anomalies.

7.8. Non-Abelian Gauge Holonomy

- The non-Abelian gauge holonomy around a non-contractible loop on is given by:

- The spectrum of gauge-invariant observables in HTUM Yang-Mills theory is entirely determined by the holonomies around all non-contractible loops on .

7.9. Entanglement Structure of Yang-Mills Vacuum

- The entanglement entropy of a region R in the Yang-Mills vacuum state on is:

- The entanglement entropy for a region R on satisfies an area law with TVEM-dependent corrections:where is the area of the boundary of R, and , , are constants.

7.10. Resurgence Theory and Transseries Expansions

- The partition function of HTUM Yang-Mills theory admits a resurgent trans-series expansion of the form:where is the instanton action, g is the coupling constant, and are coefficients encoding non-perturbative physics.

- This resurgent structure provides a framework for understanding the interplay between perturbative and non-perturbative effects in HTUM, potentially resolving renormalon ambiguities.

7.11. Quantum Yang-Mills Theory and Constructive Field Theory

- A rigorously defined quantum Yang-Mills theory on with the TVEM-modified action exists, satisfying Osterwalder-Schrader axioms of Euclidean quantum field theory.

- This construction provides a potential pathway for proving the existence of a mass gap in the continuum limit.

7.12. Higher Form Symmetries and Generalized Global Symmetries

- A q-form sameterized by closed q-forms on .

- HTUM Yang-Mills theory possesses a rich structure of higher form symmetries, including a 1-form center symmetry for SU(N) gauge groups, which are influenced by the toroidal geometry and TVEM function.

- These higher form symmetries lead to new selection rules and conservation laws for extended objects (strings, membranes) wrapping non-contractible cycles of .

7.13. Refined Numerical Methods

- Implement a tensor network renormalization scheme for HTUM Yang-Mills theory, using Matrix Product States (MPS) to efficiently represent the ground state on a discretized .

- The tensor network representation of the HTUM Yang-Mills ground state exhibits an entanglement structure that reflects both the toroidal geometry and the influence of the TVEM function.

7.14. Cosmological Phase Transitions

- As the universe described by HTUM expands and cools, it undergoes a series of phase transitions in its Yang-Mills sectors, potentially leaving observable imprints in gravitational waves and primordial black hole formation.

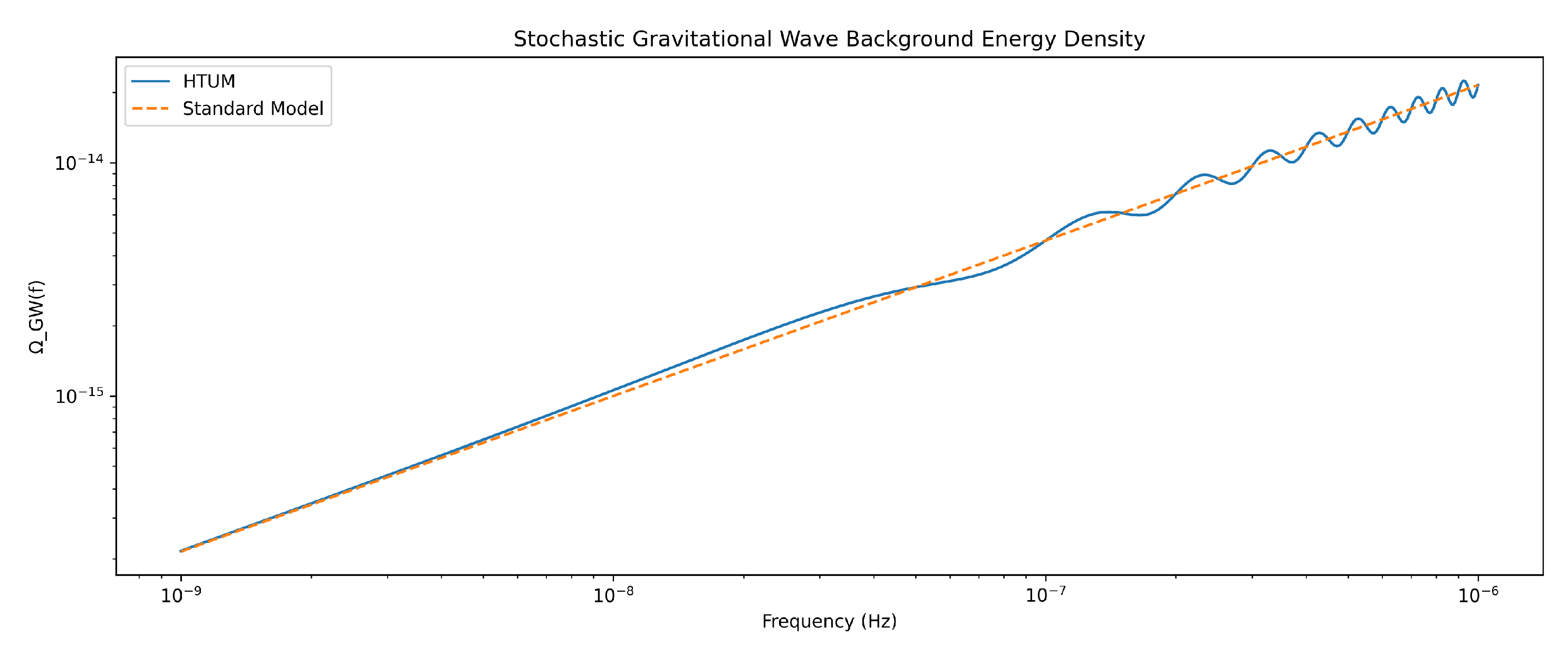

- Stochastic gravitational wave backgrounds with frequency spectra characteristic of first-order phase transitions modified by the TVEM function may be detectable in future experiments.

8. Time Dilation and Causal Processing: A Unifying Perspective

8.1. Causal Processing and Gravitational Fields

8.2. Relative Motion and Computational Capacity

8.3. Quantum Gravity Observatory Experiment

- is the baseline causal processing density

- and are coupling constants

- G is the gravitational constant

- M is the neutron star mass

- r is the distance from the neutron star’s center

- ℏ is the reduced Planck constant

- m is a characteristic mass scale (e.g., proton mass)

8.4. Experimental Observations and HTUM Predictions

8.4.1. Gravitational Time Dilation

8.4.2. Quantum Entanglement Experiment

8.4.3. Conscious Time Perception

8.4.4. Information Processing Speed

8.4.5. Quantum Decoherence Rates

8.5. Mathematical Formalism

8.6. Specific Predictions

8.6.1. Timelessness in Extreme Causal Processing Regimes

8.6.2. Causal Processing Density and the Emergence of Time

8.6.3. Quantum Realm and Singularities: A Unified Perspective

8.6.4. Implications for Physics

- Breakdown of classical physics: Classical equations assuming a standard flow of causality cease to apply as CPD approaches infinity.

- Non-locality and instantaneous effects: Extreme CPD regimes allow for apparently instantaneous causal relationships, explaining quantum non-locality and the acausal nature of singularities.

- Unification of quantum and gravitational phenomena: HTUM suggests that quantum effects and gravitational singularities are manifestations of the same underlying principle: the behavior of spacetime at maximum causal processing capacity.

8.6.5. Observational Predictions

- Quantum gravity effects: As systems approach extreme CPD, there should be observable transitions between quantum and classical behavior.

- Black hole information paradox: The apparent loss of information in black holes may be resolved by considering the timeless nature of processes at the singularity.

- Early universe phenomena: cosmic inflation and the emergence of classical spacetime from the quantum foam can be understood as transitions from extreme to moderate CPD regimes.

8.7. Comparative Analysis of Time Dilation Interpretations

- Basis: Spacetime curvature due to mass and energy

- Time dilation: Result of gravitational potential differences

- Key concept: Equivalence principle [194]

- Basis: Constancy of light speed in all reference frames

- Time dilation: Result of relative motion between observers

- Key concept: Lorentz transformations [193]

- Basis: All of spacetime exists as a four-dimensional block

- Time dilation: Differing "slices" through the 4D block

- Key concept: Eternalism [430]

- Basis: Time measured by quantum oscillations

- Time dilation: Changes in oscillation frequencies

- Key concept: Proper time as a quantum observable [393]

- Basis: Time’s arrow determined by entropy increase

- Time dilation: Local variations in entropy production rates

- Key concept: Second law of thermodynamics [468]

- Basis: Time as a measure of information processing

- Time dilation: Variations in information flow

- Key concept: Wheeler’s "It from Bit" [574]

- Unified framework: HTUM provides a single explanatory framework for time dilation effects observed in both gravitational and high-velocity scenarios and quantum systems.

- Consciousness integration: Unlike other interpretations, HTUM explicitly incorporates consciousness as a fundamental universe aspect, linking subjective time perception with objective time dilation [256].

- Computational cosmos: HTUM’s view of the universe as a vast information-processing system offers a novel perspective on why physical laws take the form they do, potentially leading to new insights into fundamental physics [359].

- Scalability: The HTUM interpretation seamlessly scales from quantum to cosmic levels, providing a consistent explanation across all scales of physics.

- Predictive power: By framing time dilation in causal processing, HTUM suggests new avenues for research and potential technological applications, such as manipulating local computational complexity to influence time flow.

- Philosophical implications: HTUM’s approach to time dilation raises intriguing questions about the nature of reality, free will, and the role of consciousness in the universe, encouraging interdisciplinary research [132].

8.8. Practical Challenges and Future Experimental Considerations

- Extreme environmental requirements: The proposed experiment requires placing precise instruments around a neutron star in close orbit. This presents significant engineering challenges regarding radiation shielding, temperature control, and maintaining stable orbits [332].

- Measurement precision: Detecting the subtle differences predicted by HTUM, especially in quantum entanglement fidelity and decoherence rates, requires measurement precision beyond current technological capabilities [95].

- Isolating HTUM effects: Distinguishing HTUM-specific effects from those predicted by standard general relativity and quantum mechanics will require careful experimental design and data analysis techniques [23].

- Long-term stability: Maintaining the experiment over extended periods to gather statistically significant data poses challenges regarding equipment longevity and data transmission [581].

- Consciousness measurements: Quantifying and standardizing subjective time perception in extreme gravitational environments presents unique challenges in experimental design and data interpretation [593].

- Developing advanced space-based precision measurement technologies, potentially utilizing quantum sensing techniques [91].

- Exploring alternative astrophysical systems that might offer similar conditions with less extreme engineering requirements, such as binary pulsars or supermassive black hole environments [439].

- Designing Earth-based experiments that could test aspects of HTUM predictions, such as advanced interferometry setups or quantum optics experiments in variable gravitational potentials [452].

- Collaborating with neuroscientists and psychologists to develop robust protocols for measuring subjective time perception in extreme conditions [253].

- Utilizing machine learning and advanced statistical techniques to isolate minor HTUM-specific effects from more significant background signals [229].

8.9. Future Directions and Implications

9. Information Theory and Holography in HTUM

9.1. Toroidal Encoding of Information

9.2. The Toroidal Holographic Principle

9.3. Black Hole Information Paradox in HTUM

9.4. Quantum Error Correction on the Torus

9.5. Entanglement and Causal Structure in HTUM

| Region | Size (relative to torus) | Entanglement Entropy |

|---|---|---|

| Small sphere | 0.01 | |

| Large sphere | 0.1 | |

| Thin slice | 0.01 (thickness) | |

| Half-torus | 0.5 |

9.6. Black Hole Information Paradox in HTUM

9.6.1. Modified Page Curve

9.6.2. Quantum Error Correction on the Torus

9.6.3. Black Hole Complementarity in HTUM

10. HTUM and the Computational Universe

10.1. Introduction to the Computational Universe Concept

10.2. The Universe as a Quantum Computer

10.2.1. Quantum Gates in the Toroidal Structure

10.2.2. Entanglement and Non-local Computations

10.3. Information Processing in HTUM

10.3.1. Wave Function Collapse as Information Processing

10.3.2. Emergence of Classical Reality

10.4. Algorithmic Complexity of the Universe

10.4.1. Kolmogorov Complexity in HTUM