Submitted:

09 June 2024

Posted:

11 June 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

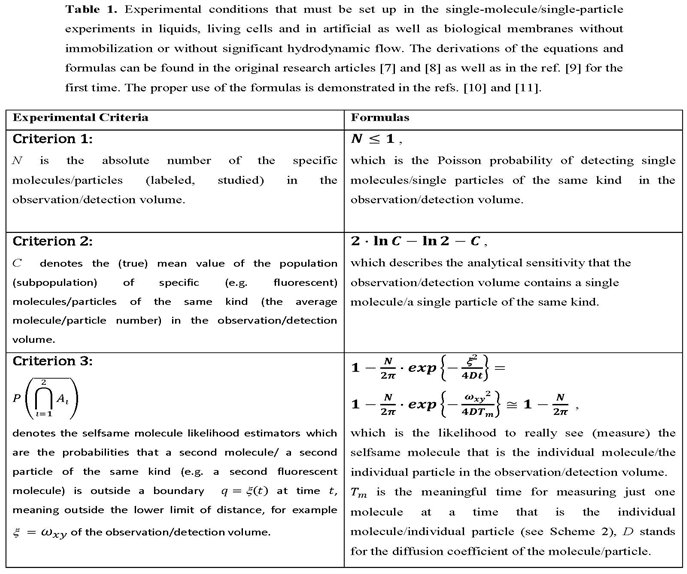

3.1. Evaluation of Single-Molecule Detection: A Brief Narrative on the Motivation of the Simulation Experiments and Their Design as Experimetnal Starting Point for the Obtained Results

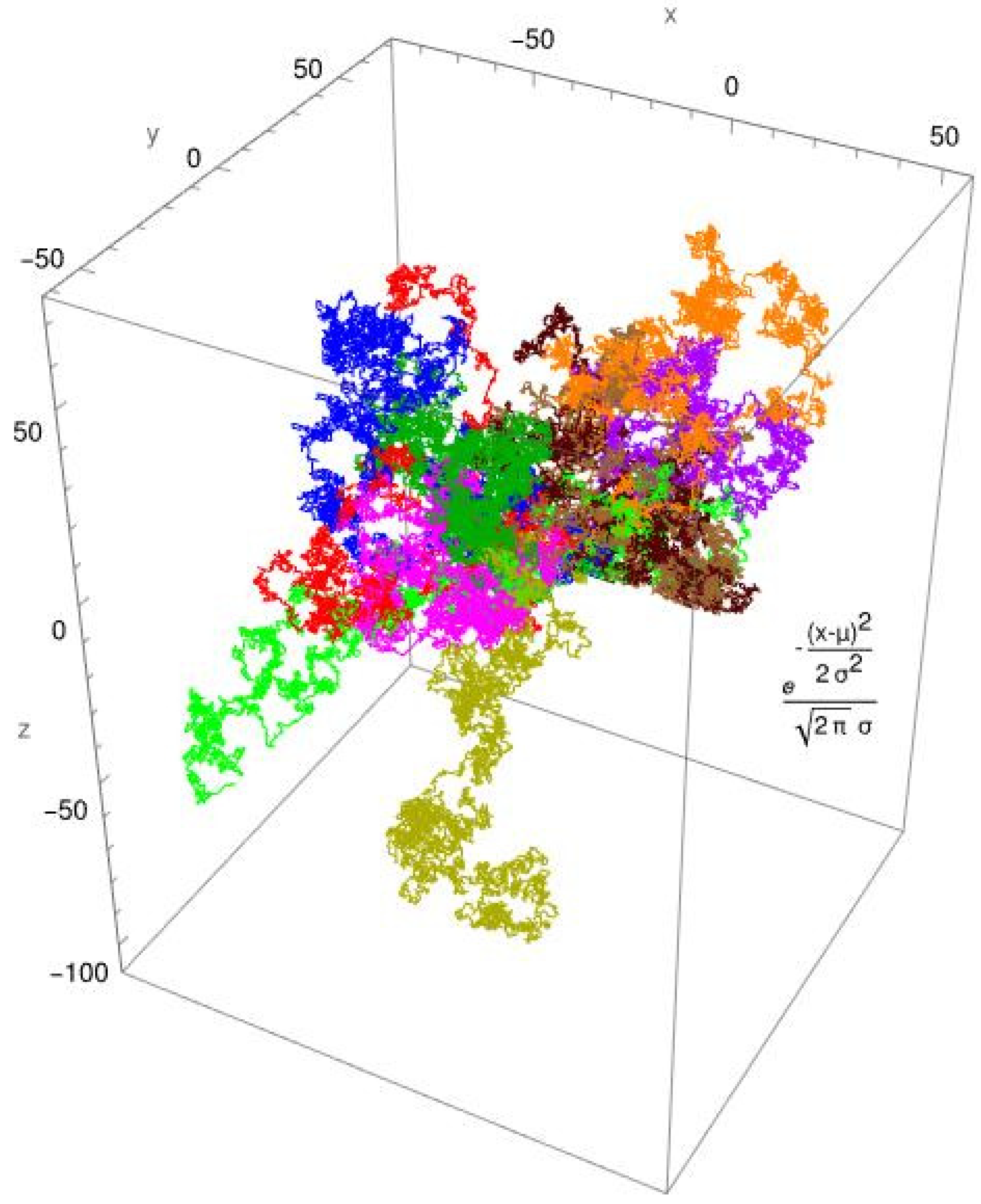

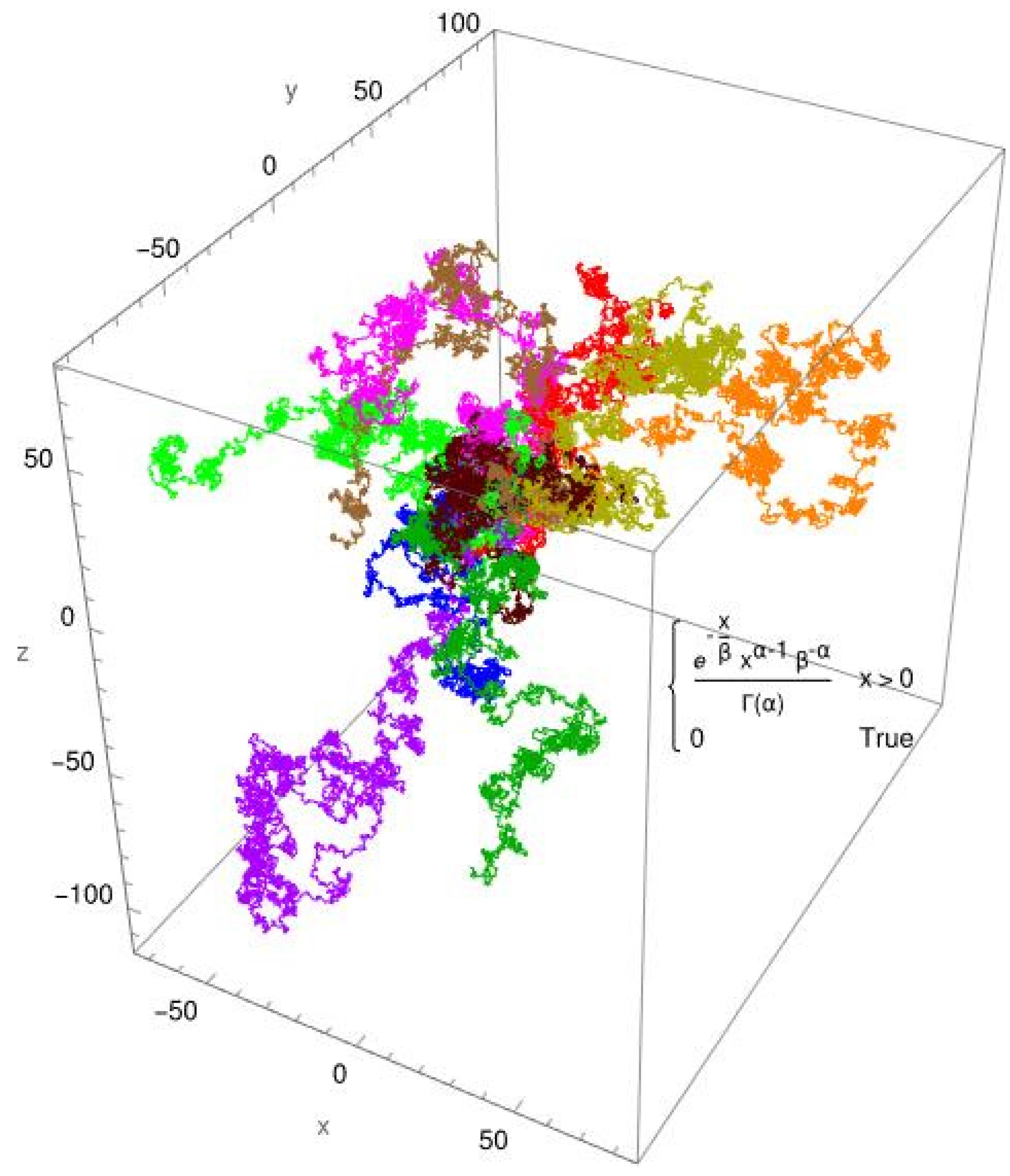

3.2. Single-Molecule Tracking

4. Discussion

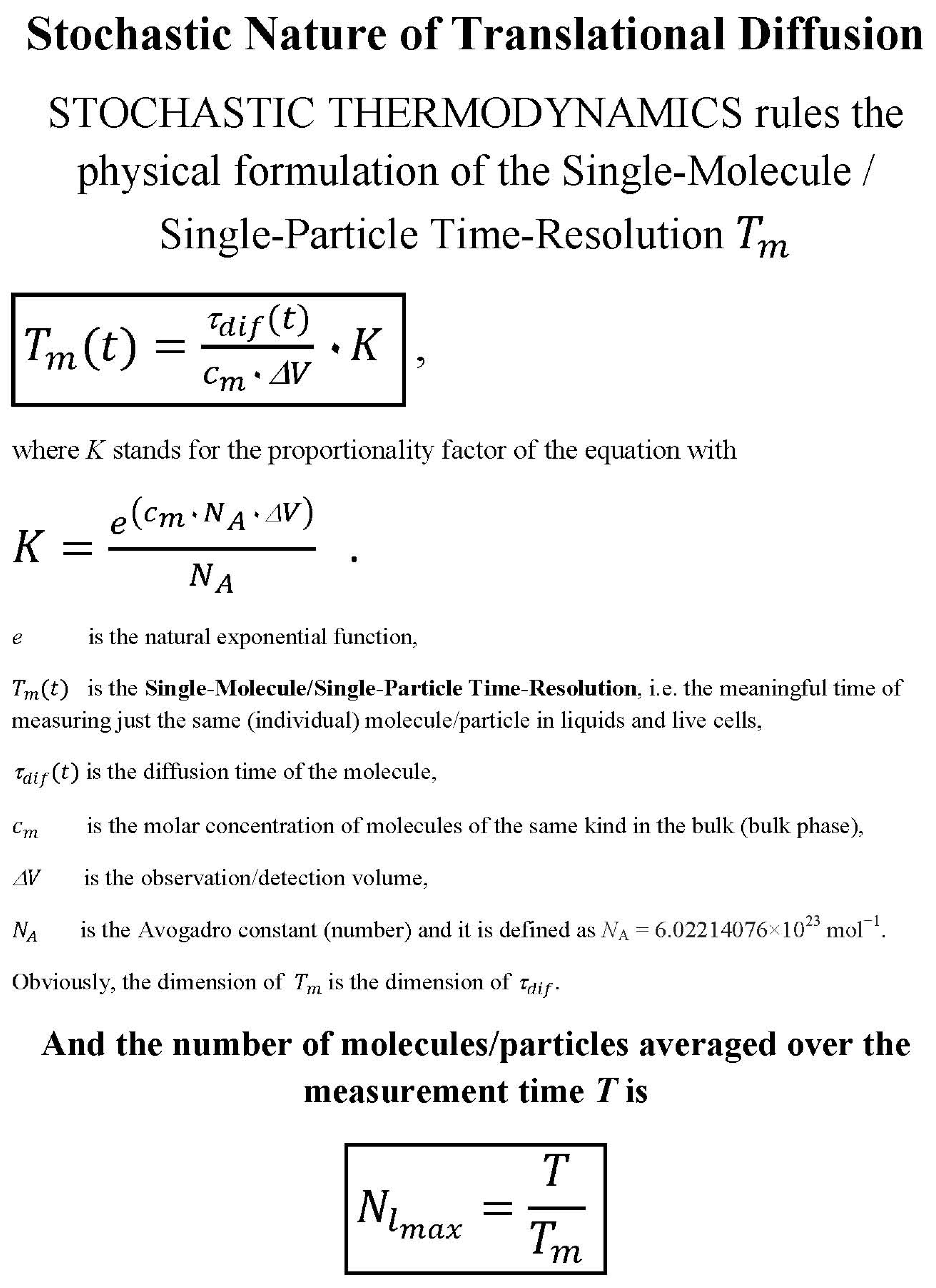

- (i)

- the meaningful time as single molecule/single particle time resolution is discussed here (for mathematical details see: ref. [12]),

- (ii)

- the meaningful times as limits of measurement time that should not be exceeded to follow the same single molecule/the same single particle with high probability in one, two or three dimensions (for mathematical details see: the Table 1 in ref. [11]) and

- (iii)

5. Conclusions

6. Addendum

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- DʼEste, E.; Lukinavičius, G.; Lincoln, R.; Opazo, F.; Fornasiero, E.F. Advancing cell biology with nanoscale fluorescence imaging: essential practical considerations. Trends Cell Biol. 2024, Jan 5, S0962-8924(23)00239-8. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loidolt-Krueger, M. New Confocal Microscope for quantitative fluorescence lifetime imaging with improved reproducibility. Microscopy Today. 2023, 31, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harms, G.S.; Cognet, l..; Lommerse, P.H.; Blab, G.A;, Schmidt, T. Autofluorescent proteins in single-molecule research: applications to live cell imaging microscopy. Biophys. J. 2001, 80, 2396–2408. .

- White, J.; Stelzer, E. Photobleaching GFP reveals protein dynamics inside live cells. Trends Cell Biol. 1999, 9, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Exell, J.; Lin, H.; Zhang, C.; Welsher, K.D. Hour-long, kilohertz sampling Rate three-dimensional single-virus tracking in live cells enabled by StayGold fluorescent protein fusions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2024, online publication date May 29. [CrossRef]

- Foote, A.K.; Ishii, K.; Cullinane, B.; Tahara, T.; Goldsmith, R.H. Quantifying microsecond solution-phase conformational dynamics of a DNA hairpin at the single-molecule level. ACS Phys. Chem. 2024, online publication date May 29. [CrossRef]

- Földes-Papp, Z. Fluorescence fluctuation spectroscopic approaches to the study of a single molecule diffusing in solution and a live cell without systemic drift or convection: a theoretical study. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2007, 8, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Földes-Papp, Z. ‘True’ single-molecule molecule observations by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy and two-color fluorescence cross-correlation spectroscopy. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2007, 82, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Földes-Papp, Z.; Baumann, G.; Kinjo, M.; Tamura, M. Single-Phase Single-Molecule Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy (SPSM-FCS). In Encyclopedia of Medical Genomics & Proteomics; Fuchs, J., Podda, M., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: New York, USA, 2005; pp. 1-7.

- Földes-Papp, Z. What it means to measure a single molecule in a solution by fluorescence fluctuation spectroscopy. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2006, 80, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Földes-Papp, Z. Single-molecule time resolution in dilute liquids and live cells at the molecular scale: Constraints on the measurement time. Am. J. Transl. Med. 2021, 5, 154–165. [Google Scholar]

- Földes-Papp, Z. Measurements of Single Molecules in Solution and Live Cells Over Longer Observation Times Than Those Currently Possible: The Meaningful Time. Curr. Pharm Biotechnol. 2013, 14, 441–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumann, G.; Földes-Papp, Z. Study on Single-Molecule Biophysics and Biochemistry in dilute liquids and live cells without immobilization or significant hydrodynamic flow: The thermodynamic Single-Molecule DEMON. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2022, 23, 1750–1757. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Földes-Papp, Z. The thermodynamic signature of a single molecule or a single particle in dilute liquids and live cells: Single-Molecule Biophysics & Biochemistry based on the stochastic nature of diffusion. Am. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 7, 74–77. [Google Scholar]

- Baumann, G.; Place, R.F.; Földes-Papp, Z. Meaningful interpretation of subdiffusive measurements in living cells (crowded environment) by fluorescence fluctuation microscopy. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2010, 11, 527–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Földes-Papp, Z. Individual macromolecule motion in a crowded living cell. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2015, 16, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Földes-Papp, Z.; Baumann, G.; Li, L.-C. Visualization of subdiffusive sites in a live single cell. J. Biol. Methods 2021, 8, e142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Digman, M.A.; Gratton, E. Lessons in fluctuation correlation spectroscopy Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2011, 62, 645–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Földes-Papp, Z.; Baumann, G. Fluorescence molecule counting for single-molecule studies in crowded environment of living.

- cells without and with broken ergodicity. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2011, 12, 824–833.

- Földes-Papp, Z.; Herold, A.; Seliger, H.; Kleinschmid,t A.K. Error propagation theory of chemically solid phase synthesized.

- oligonucleotides and DNA sequences for biomedical application. In <i>Fractals in Biology and, Medicine</i>; Nonnenmacher, T.F. oligonucleotides and DNA sequences for biomedical application. In Fractals in Biology and Medicine; Nonnenmacher, T.F.

- Losa, G.A., Weibel, E.R., Eds.; Springer: Boston, USA,1994; Volume 1, pp. 165-173.

- Gaire, S.K.; Daneshkhah, A.; Flowerday, E.; Gong, R.; Frederick, J; Backman, V. Deep learning-based spectroscopic.

- single-molecule localization microscopy. J. Biomedical Optics, 2024, 29, 1-19.

- Xu, X.; Gao, C.; Emusani, R.; Jia, C.; Xiang, D. Toward Practical Single-Molecule/Atom Switches. Adv. Sci. (Weinh.), 2024, online publication day May 29, e2400877. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).