1. Introduction

The transport and binding of individual molecules to specific targets appear to be involved in the assembly and function of ordered supramolecular structures in living cells. There is broad consensus that the analysis of these processes in vitro and vivo is of central importance in the life sciences, including molecular sciences. In cellular compartments, transport is often driven by diffusion, which tends to equalize local concentration gradients. Diffusion behavior has been studied over the last decades using various experimental technologies, mainly based on fluorescence techniques using confocal or wide-field optics including laser scanning microscopy. Therefore, time-resolved protein mobility data are correlated with images of cellular structures from confocal fluorescence laser scanning microscopy to identify localization-specific dynamics and interactions of a fluorescently labeled species.The spatial resolution of mobility and interaction analysis in nanoscopy is no longer limited by the diffraction-limited size of the excitation volume (observation/detection volume) in a confocal fluorescence microscopy/spectroscopy setup. For many of these approaches, green fluorescent protein (GFP) and its spectral relatives are particularly well suited due to their high fluorescence yield and photobleaching properties in the intracellular environment [1]. And they can be fused to proteins in vivo [2]. As a result of these technological and biotechnological developments, single-molecule studies in liquids and live cells have emerged. Such studies refer to measurements of individual molecules (individual particles), but cannot be equated with them. Fortunately, for diffusion-controlled reactions or systems, there are physical criteria to make a clear decision, as summarized in Table 1.

Molecule number fluctuations are currently of interest. The fundamental results are due to Markov processes, which are the gateway to dynamic systems whose number of molecules fluctuates. The probability of separating two individual molecules or two individual particles as independent molecular entities during the measurement time is criterion 3 as found in ref. [7] (see Table 1 contained therein for various experimental measurement conditions) and in the Table 1 of this article. The probability of separating two individual molecules or two individual particles as independent molecular entities during the measurement time is criterion 3 as found in ref. [7] (see Table 1 contained therein for various experimental measurement conditions) and in the Table 1 of this article.

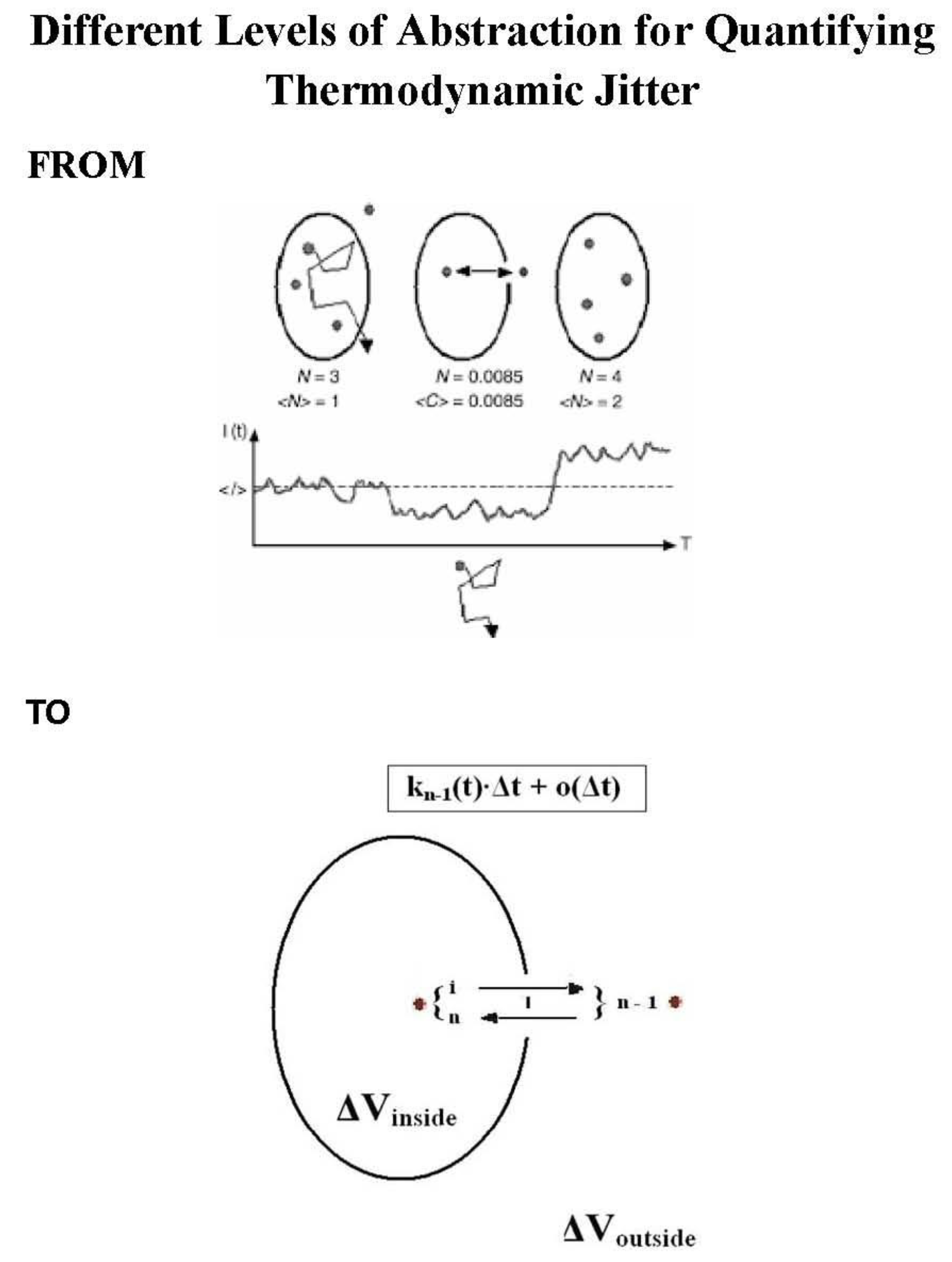

The

Scheme 1 and the

Scheme 2 are summarizing important theoretical results for the measurement of just one molecule at a time, e.g. in liquids at room temperature or in living cells under physiological conditions, without immobilization or hydrodynamic flow. We have already gained extensive experience with single-molecule detection in liquids and living cells (see subsection

2.1. Evaluation of single-molecule detection: A brief Narrative). Here, we want to make a contribution in the field of ‘single-molecule tracking’ for the benefit of researchers, for example in molecular sciences such as biophysics, physical chemistry and biochemistry.

Upper Panel: Molecular scenarios in dilute liquid are shown schematically for an observation/detection volume (upper part) and for observed intensity fluctuations (lower part). N denotes the molecule number in the probe region and <N> is the average molecule number. If the observed N value becomes1, then N stands for the Poisson probability of arrival of an individual particle in the observation/detection volume, criterion 1). Under the condition N 1, <C> = C is the average frequency that the observation/detection volume contains a single particle. For C << e-C, C equals N. I(t) is the fluorescence intensity, <I> stands for a mean intensity, and T is the measurement time for data collection. Completeness includes the criterion 2, that is the sensitivity for measuring just one and the same particle, which is. the ‘departure’ probability of an individual particle. For details see the original research articles [4] and [5] as well as the reference [6]. Particle measns physically each single molecule.

Lower Panel: An example of meaningful reentries is depicted. The molecule is inside the observation/detection volume ΔV and diffuses out from its moving state i to another moving state n - 1 outside the probe region. Then, it diffuses in from its moving state n – 1 to n. Hence, the random variable X(t) makes the transition from X(s) = I to X(t) = n - 1 during the time interval [s, t) and afterwards the transition from X(t) = n - 1 to X(t + Δt) = n during the time interval [t, t + Δt). These reentries (transitions) contribute to the fluorescence intensity fluctuations in the experiments. They are the number of reentries that result in a useful burst size. For details see the original research article [3].

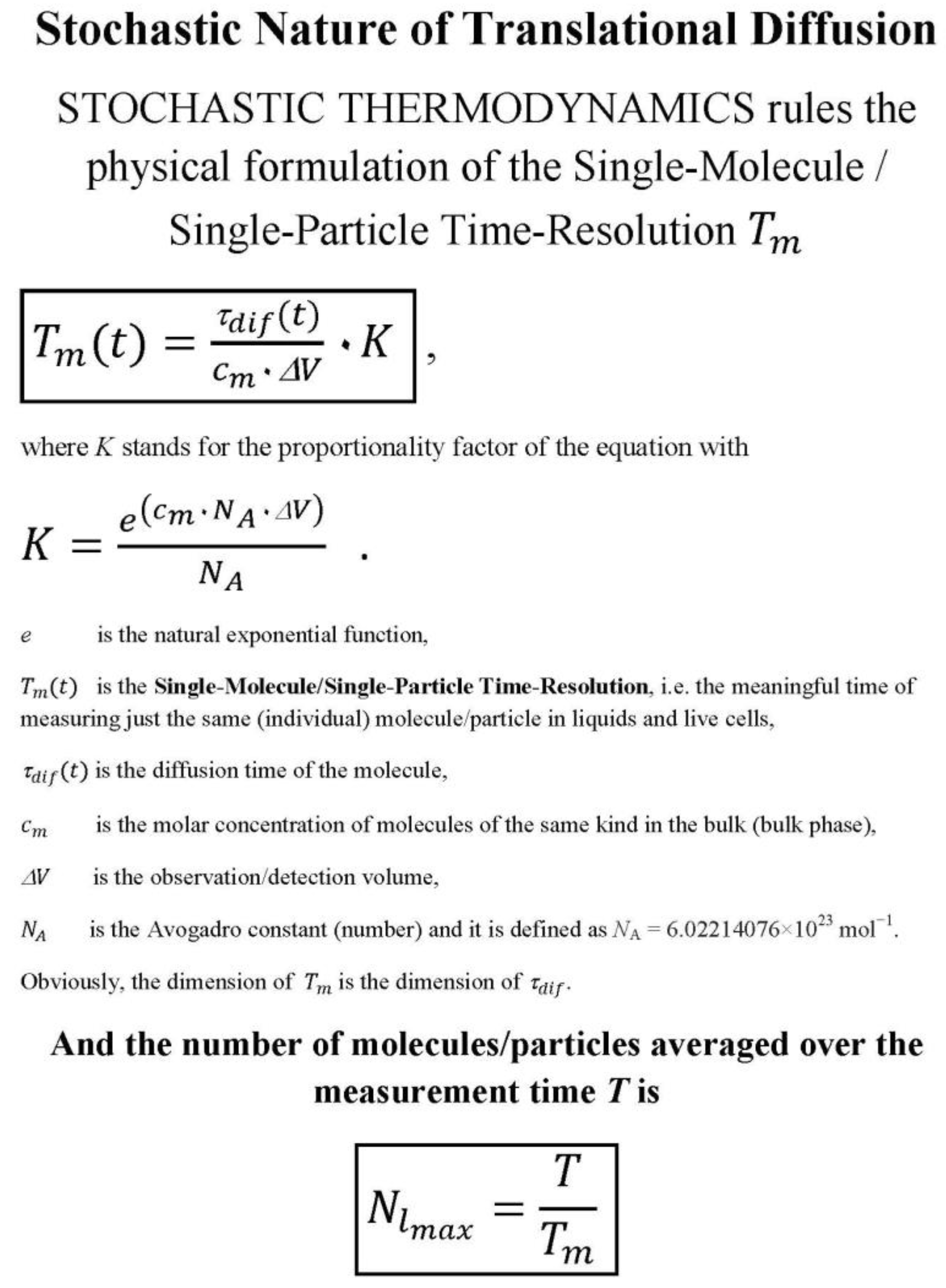

The scheme2 summarizes theoretical results for measuring just one molecule at a time in liquids or live cells without immobilization or hydrodynamic flow.. A head start is the proven theory, e.g. proven mathematically, that turns knowledge into strength, even at odds with mediocre mainstream (see also [7,8,9,10].

2. Results

2.1. Evaluation of Single-Molecule Detection: A Brief Narrative

The basic principle of single-molecule detection without immobilization on a surface or without hydrodynamic flow in liquids at room temperature or in livie cells under physiological conditions appears to be simple. A single molecule experiment is, strictly speaking, an experiment that examines the properties of a single molecule only. This means one probe molecule should diffuse in the excited detection volume and the light emitted from this molecule should be distinguishable from the experimental noise. It becomes much more difficult if such a scenario is quantified based on the temporal movement (time resolution) of individual molecules. The concept of thermodynamic jitter due to the individual molecule was first developed in refs.. [3,4,5,6,8]. The physical Theory based on the stochastic nature of diffusion is exemplified in refs. [11,12]. It was considered pioneering work [13].

To decide experimentally whether it is a single molecule or not requires physical criteria, as we summarized in

Scheme 1. From these criteria 1 to 3 we then come to the time resolution of a single molecule, i.e. criterion 4, shown in

Scheme 2. This is merely the way to understand what occurs during diffusion of an individual molecule in the observation/detection volume embedded into a bulk phase [14,15]. Next, let us now shed some light in tracking of of single molecules foor live cells by simulations. In live cells or their compartments such as the nucleus or membranes, the movements of molecules are complicated due to the large crowding and expected heterogeneity of the intracellular environment compared to liquids. The simulation approaches that we use are continuous time random walks (CTRW) on a fractal support of a generalized 3D Sierpinski carpet representing a live cell, e.g. its cytoplasm (see

4. Methods).

2.2. Single- Molecule Tracking

Let us say, the single molecule diffused from another molecule (protein) to about 1 nanometer. The encounter has begun and in about a nanosecond the molecule can touch a surface or be repelled by another molecule (protein) due to molecular crowding in the cytoplasm. In

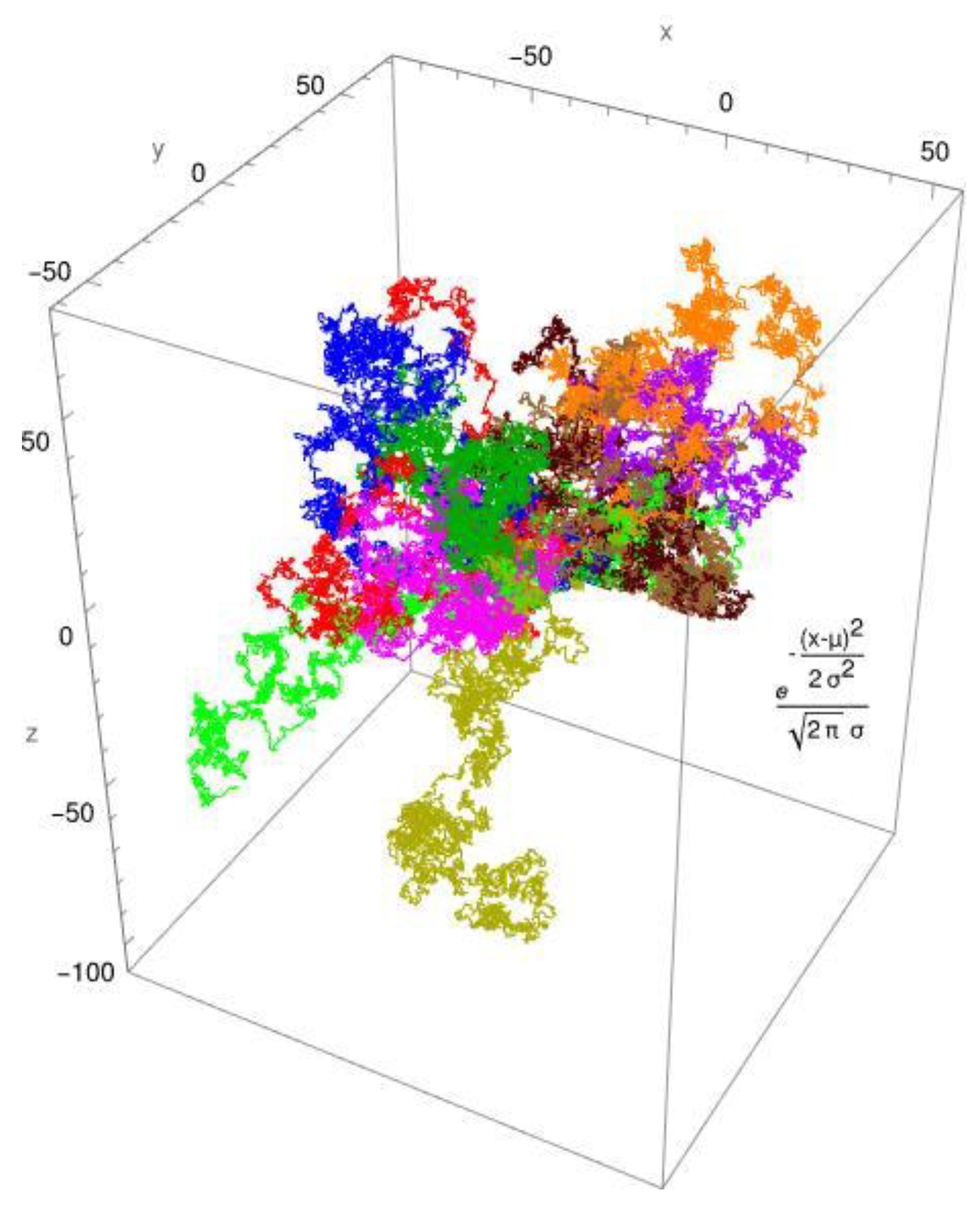

Figure 1, the simulated diffusion of a protein is shown for a Brownian motion. In

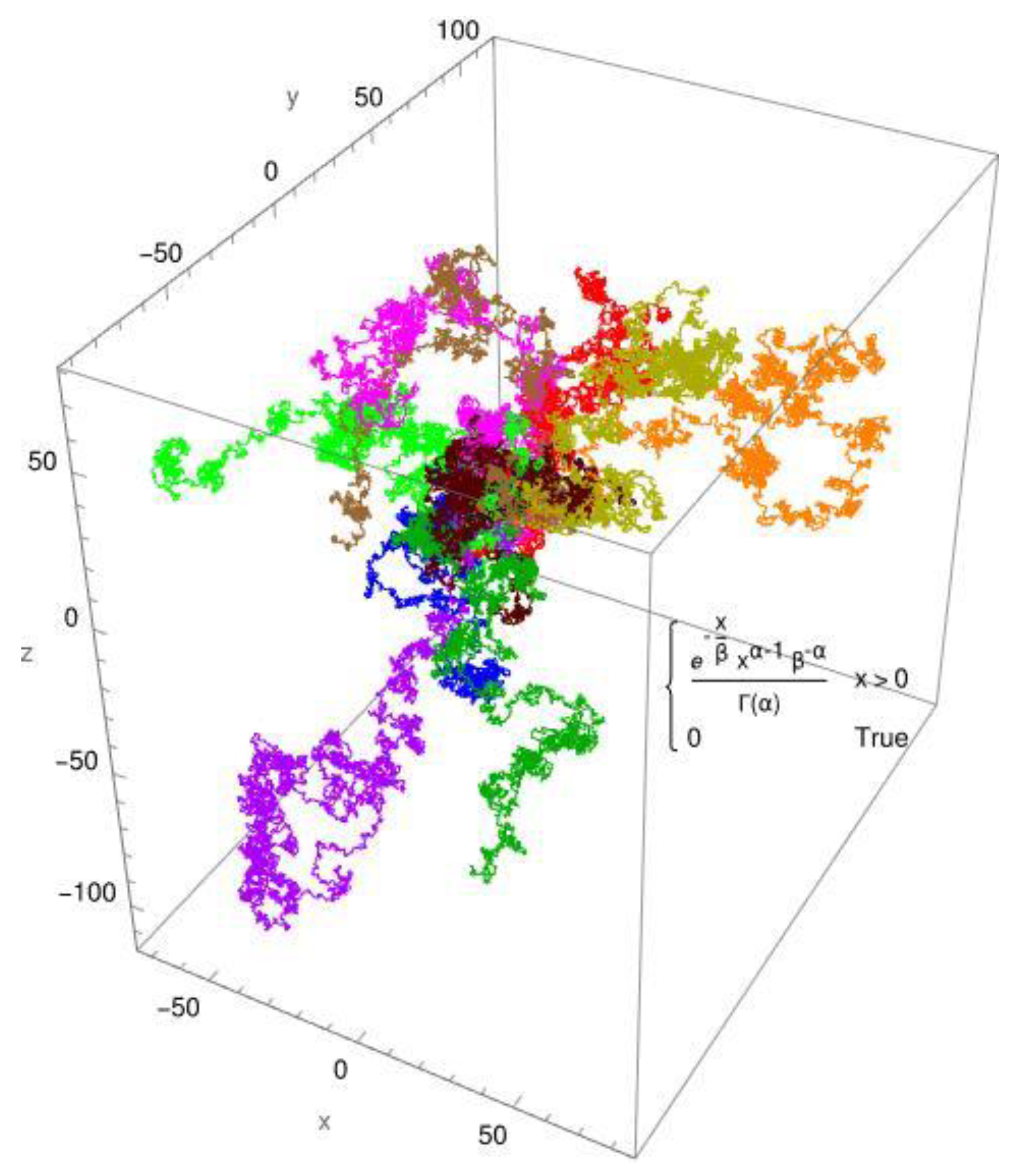

Figure 2, the simulated diffusion of a protein is shown for an anomalous diffusion. The colors indicate 10 different tracks for individual molecules/individual particles.

The CTRW step (

continuous-time random walk step)

employs two distribution functions: the standard Gaussian distribution for Brownian diffusion (Figure 1) and, as an example, the gamma distribution for anomalous diffusion processes (Figure 2). The created pathways look similar, yet they differ in significant aspects. These are shown in Figure 1 and

Figure 2. It is evident that the Gaussian distribution yields pathways that are quite similar to each other. The gamma function, which produces a fractional diffusion, provides pathways that are quite diverse from one another and diverge significantly from those of the Gaussian distribution. However, the most remarkable feature is that the Gaussian distribution generates pathways that are close to the measurement origin and concentrated around it. The situation with the gamma distribution is fundamentally different; here, paths emerge that have a certain localization around the measurement origin but are also delocalized in more than 60%. In other words, the pathways become looser and have large leaps, which are typical of fractional diffusion. This form of unwinding is typical of fractional diffusion.

3. Discussion

What happens theoretically has been the subject of several publications. We specified the ergodic hypothesis, according to which the behavior of single molecules should not be extrapolated to the behavior of all molecules [14]. We previously established the minimum variation at which the number of randomly selected single molecule traces is Nℓmax = 32 by simulations [14]. All other values of Nℓ provided a local minimum instead of a global minimum.

The plots further showed (see Figure 1 in Ref. [14]) that the variation approaches a stable value as Nℓ approaches large values. Only a small subpopulation of individual molecules provides the minimal variation. The feature of ensemble averaging in sparse subpopulations of single molecules is the same average obtained in an ergodic system composed of many molecules when the number of randomly selected single molecule traces is Nℓmax = 32 [14].

Broken ergodicity and unbroken ergodicity can no longer be distinguished. If averaging procedures are performed without knowing whether the molecular system behaves in an ergodic or non-ergodic manner, any measurement may be associated with ergodic or non-ergodic behavior unless the single-molecule fingerprint of non-ergodic behavior. is demonstrated[14]. The thermodynamic jitter (signature) of an individual molecule is the single molecule fingerprint [10]. The new findings of this article provide the opportunity to analyze molecular behavior when individual biomacromolecules in living cells are trapped in their cellular compartments in interactions with their neighboring ligands or reactants [9]. The measurement of the individual molecule over several milliseconds to seconds and even minutes is considered one of the most demanding research trends in spectroscopy, microscopy and nanoscopy.

The measurement time for measuring just a single molecule (individual molecule) or a single particle (individual particle) is a meaningful time, in contrast to the measurement times for measuring multiple molecules. Using the mathematically derived physical relationships based on stochastic translational diffusion [9], we differentiate between three types of meaningful points in time:

- (i)

the meaningful time is the single-molecule time-resolution asdiscussed here (for mathematical details see: ref. [8]),

- (ii)

the meaningful times are limits of measurement times that should not be exceeded in order to track the individual molecule/particle with high probability in one, two or three dimensions (for mathematical details see: Table 1 in ref. [7]) and

- (iii)

the meaningful time is the quantitative measure for the meaningful reentries of the individual molecule/individual particle in the observation/detection volume (for mathematical details see: equation (12) in ref. [3] and equations (2a) – (2c) and (3) in ref. [4]).

The dimensions of the meaningful times are the dimensions of the diffusion times.

Individual molecules (oligonucleotides and single-stranded DNA sequences) were theoretically described in chemical oligonucleotide syntheses on solid supports after release from the solid phase as early as 1994 for the first time [16]. A head start is the mathematically proven theory on thermodymanical jitter of single moelcules as discussed in this article that turns knowledge into strength, even at odds with the mainstream. What new insights can be gained from the foundation of the theory on ‘Single-Molecule/Single Particle Biophysics & Biochemistry Based On the Stochastic Nature of Diffusion’ without immobilization on a surface or without hydrodynamic flow? For example, the thermodynamic signatures of single molecules and single particles in liquids and live cells (cytoplasm, membranes) as found in

ref. [10]

and shown by simulations in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

4. Methods

Our simulations presented in this research article are based on the generator g24 from ref. [15], which simulates the fractal structure in a biological cell, e. g. in its cytoplasm [15]. A limited continuous time random walk (LCTRW) is then performed on this structure (generalized 3D Sierpinski carpet) to assess the statistical properties of the diffusion process. The continuous time random walk is based on a distribution function that is freely configurable. Theoretical considerations for simulation and analyzing mobility data in this way for live cells and their compartments such as the cytoplasm are given in detail in ref. [15]. To highlight the disparities in the distribution function on the fractal structure, we investigated in this article two scenarios, each consisting of typical tracks. All pathways have one thing in common: they are placed in the coordinate origin that we have chosen for utilization, which is within the femtoliter measurement chamber that is the focus of a laser used for excitation and detection of fluorescent molecules (for theoretical and simulation details see ref. [15]).

5. Conclusions

The formulas and physical relationships specified in this article apply. They are simple and safe for determining how many molecules are averaged during measurement times. The biggest breakthrough would be to further increase the sensitivity in the time domain of measurements in liquids at room temperature and living cells, including membranes at physiological conditions without immobilization or hydrodynamic flow.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated and analyzed in this study that supports the findings are included in this published article were not published before.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Harms, G.S.; Cognet, l.; Lommerse, P.H.; Blab, G.A; Schmidt, T. Autofluorescent proteins in single-molecule research: applications to live cell imaging microscopy. Biophys. J. 2001, 80, 2396–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, J.; Stelzer, E. Photobleaching GFP reveals protein dynamics inside live cells. Trends Cell Biol. 1999, 9, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Földes-Papp, Z. Fluorescence fluctuation spectroscopic approaches to the study of a single molecule diffusing in solution and a live cell without systemic drift or convection: a theoretical study. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2007, 8, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Földes-Papp, Z. ‘True’ single-molecule molecule observations by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy and two-color fluorescence cross-correlation spectroscopy. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2007, 82, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Földes-Papp, Z.; Baumann, G.; Kinjo, M.; Tamura, M. Single-Phase Single-Molecule Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy (SPSM-FCS). In Encyclopedia of Medical Genomics & Proteomics; Fuchs, J., Podda, M., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: New York, USA, 2005; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Földes-Papp, Z. What it means to measure a single molecule in a solution by fluorescence fluctuation spectroscopy. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2006, 80, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Földes-Papp, Z. Single-molecule time resolution in dilute liquids and live cells at the molecular scale: Constraints on the measurement time. Am. J. Transl. Med. 2021, 5, 154–165. [Google Scholar]

- Földes-Papp, Z. Measurements of Single Molecules in Solution and Live Cells Over Longer Observation Times Than Those Currently Possible: The Meaningful Time. Curr. Pharm Biotechnol. 2013, 14, 441–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumann, G.; Földes-Papp, Z. Study on Single-Molecule Biophysics and Biochemistry in dilute liquids and live cells without immobilization or significant hydrodynamic flow: The thermodynamic Single-Molecule DEMON. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2022, 23, 1750–1757. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Földes-Papp, Z. The thermodynamic signature of a single molecule or a single particle in dilute liquids and live cells: Single-Molecule Biophysics & Biochemistry based on the stochastic nature of diffusion. Am. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 7, 74–77. [Google Scholar]

- Földes-Papp, Z. Individual macromolecule motion in a crowded living cell. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2015, 16, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Földes-Papp, Z.; Baumann, G.; Li, L.-C. Visualization of subdiffusive sites in a live single cell. J. Biol. Methods 2021, 8, e142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Digman, M.A.; Gratton, E. Lessons in fluctuation correlation spectroscopy Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2011, 62, 645–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Földes-Papp, Z.; Baumann, G. Fluorescence molecule counting for single-molecule studies in crowded environment of living cells without and with broken ergodicity. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2011, 12, 824–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumann, G.; Place, R.F.; Földes-Papp, Z. Meaningful interpretation of subdiffusive measurements in living cells (crowded environment) by fluorescence fluctuation microscopy. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2010, 11, 527–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Földes-Papp, Z.; Herold, A.; Seliger, H.; Kleinschmid,t A.K. Error propagation theory of chemically solid phase synthesized oligonucleotides and DNA sequences for biomedical application. In Fractals in Biology and Medicine; Nonnenmacher, T.F., Losa, G.A., Weibel, E.R., Eds.; Springer: Boston, USA,1994; Volume 1, pp. 165–173.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).