Submitted:

06 June 2024

Posted:

10 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Growing Conditions

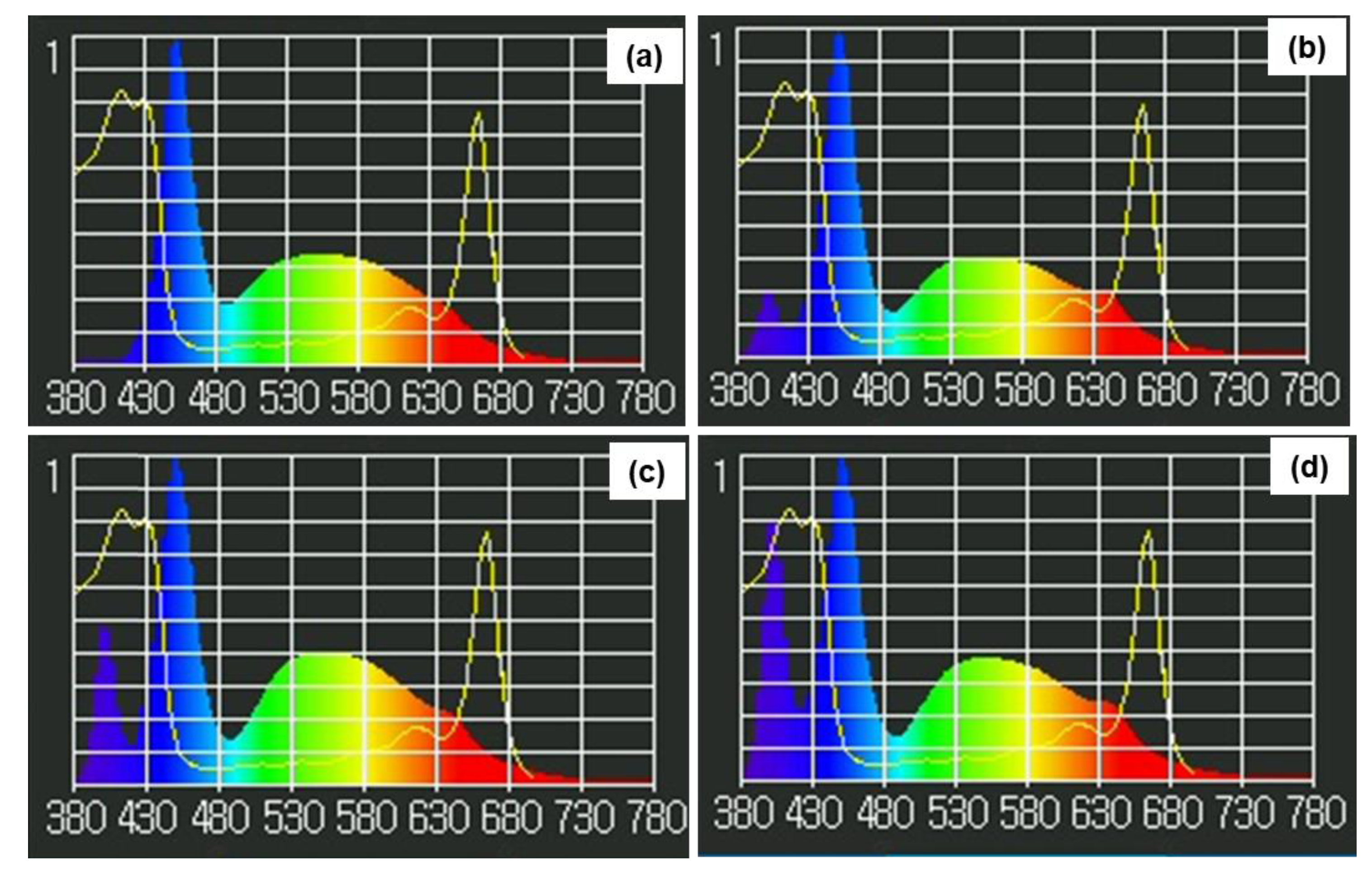

2.2. UV-A Treatment and Experimental Design

2.3. Growth and Biomass Measurements

2.4. Photosynthetic Pigment Content Evaluation

2.5. Photosynthetic Efficiency Measurement

2.6. Leaf Reflectance and Spectral Index Measurement

2.7. Phytonutrients Analysis

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effect of UV-A on Growth and Biomass of Kale Plant

3.2. Effect of UV-A on Photosynthetic Pigment Accumulation in Kale Plant

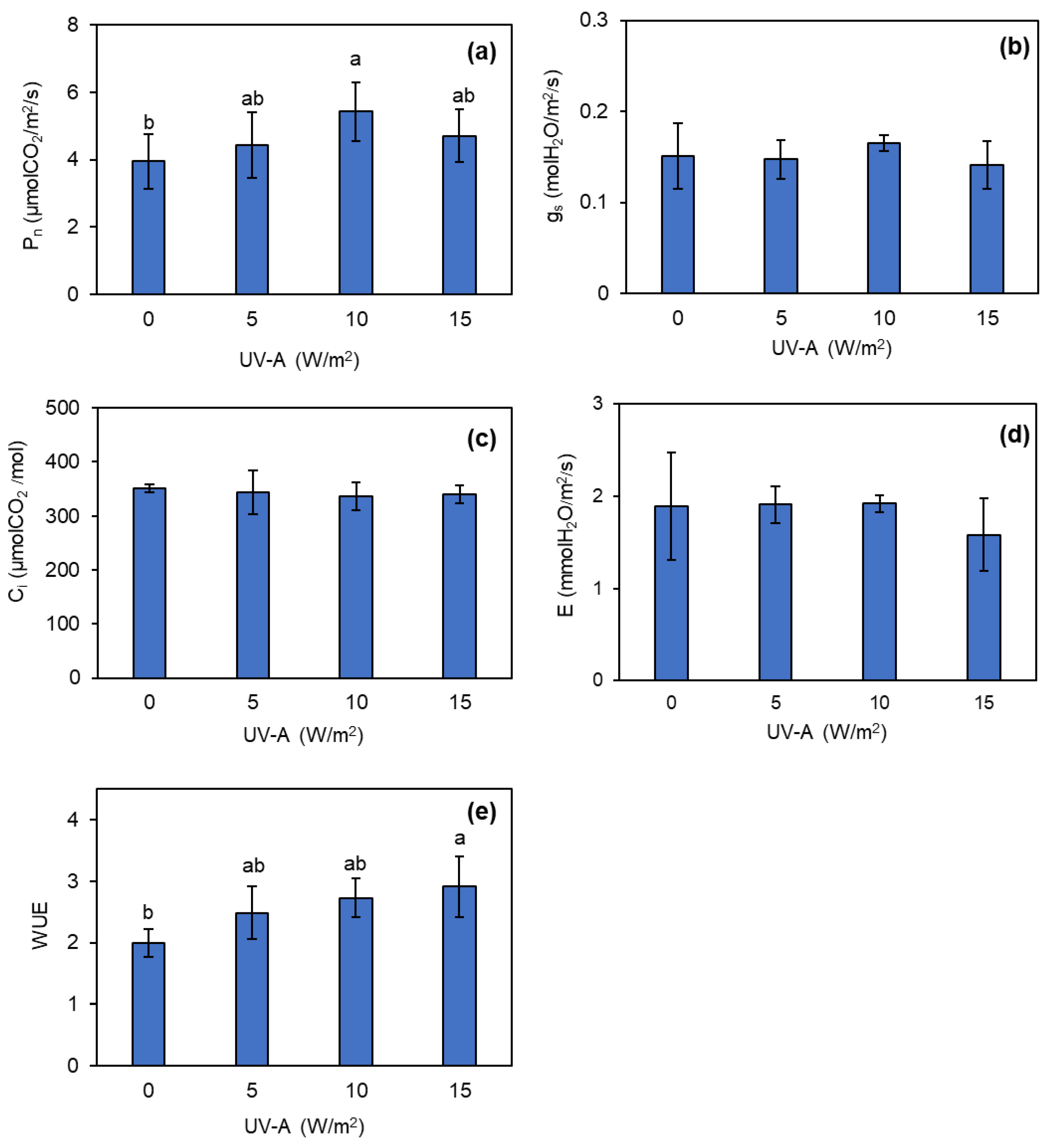

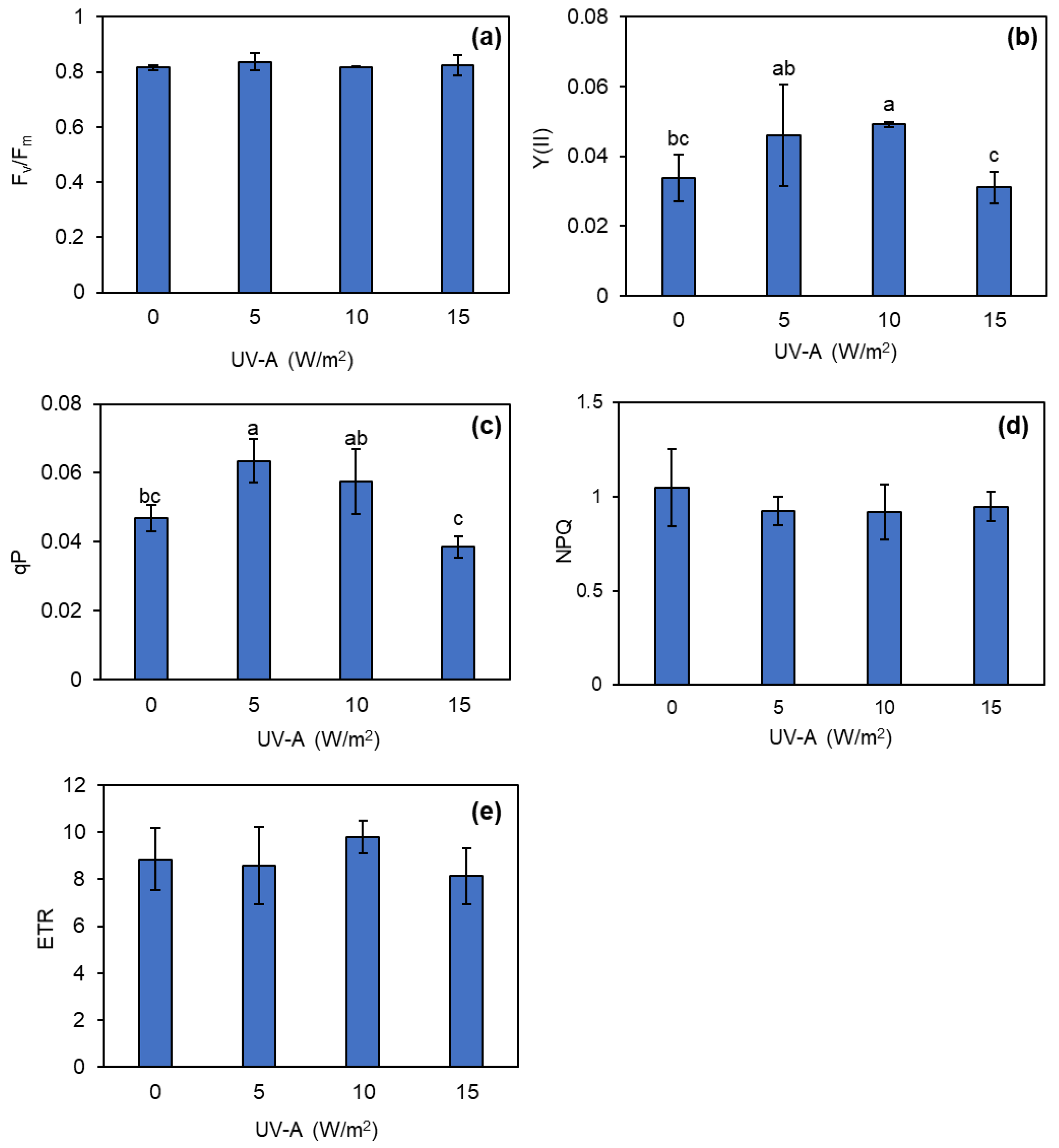

3.3. Changes in Photosynthetic Efficiency of Kale Plant Exposed to UV-A

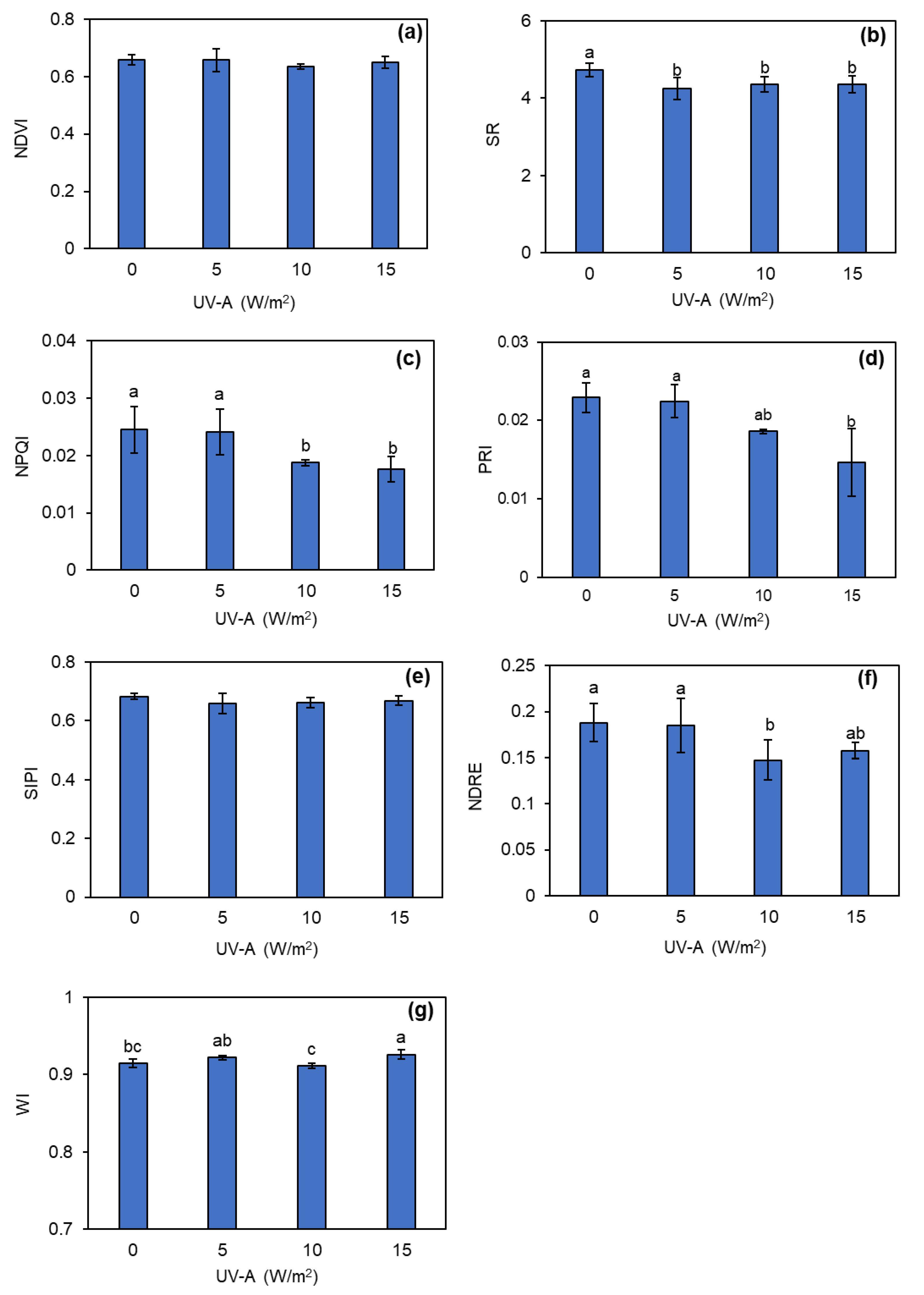

3.4. Changes in Leaf Spectral Indices of Kale Plant Treated with UV-A

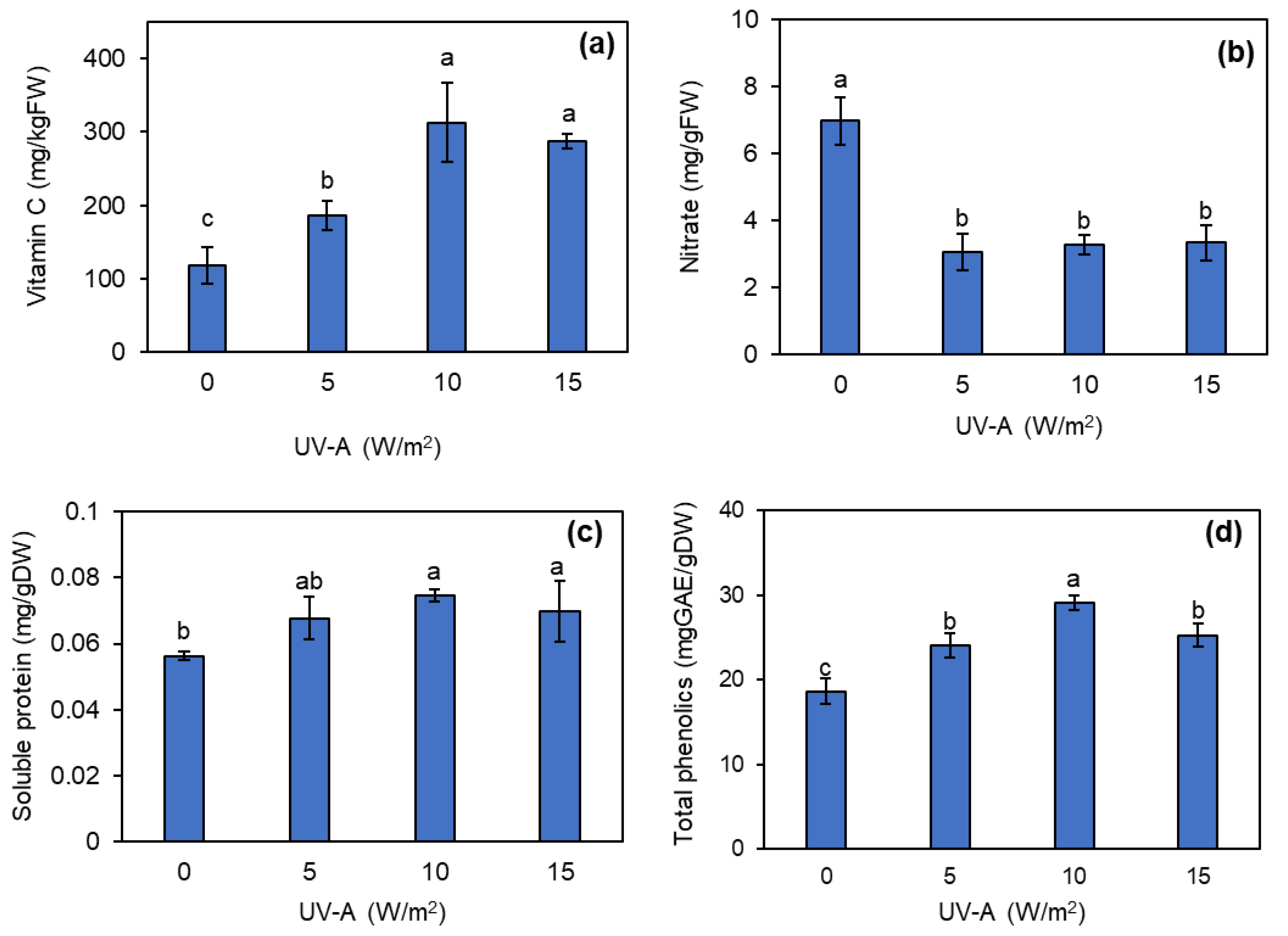

3.5. Effect of UV-A on Phytonutrients Contents in Kale

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, M.J.; Chiu, Y.; Hindawi, K.K. Glucosinolates, carotenoids, and vitamins E and K variation from selected kale and collard cultivars. J. Food Qual. 2017, 2017, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.; Kiraga, S.; 2, Islam, M. N.; Ali, M.; Reza, M.N.; Lee, W.; Chung, S. Effects of temperature, relative humidity, and carbon dioxide concentration on growth and glucosinolate content of kale grown in a plant factory. Foods 2021, 10, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terlaje, T.; Tuquero, J. Growing Kale Brassica oleracea. College of Natural & Applied Sciences (CNAS), University of Guam, Guam, USA, 2019; pp. 1–5.

- Kozai, T.; Kubota, C.; Chun, C.; Afreen, F.; Ohyama, K. Necessity and concept of the closed transplant production system. In Transplant Production in the 21st Century, 1st ed.; Kubota, C., Chun, C., Eds.; Springer Dordrecht: Dordrecht, the Netherlands, 2000; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kopsell, D.A.; Kopsell, D.E.; Curran-Celentano, J. Carotenoid pigments in kale are influenced by nitrogen concentration and form. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2007, 87, 900–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Li, Y.; He, R.; Tan, J.; Liu, K.; Chen, Y.; Liu, H. Effect of supplemental UV-A intensity on growth and quality of kale under red and blue light. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefsrud, M.G.; Kopsell, D.A.; Augé, R. M.; Both, A.J. Biomass production and pigment accumulation in kale grown under increasing photoperiods. HortScience 2006, 41, 603–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefsrud, M.G.; Kopsell, D.A.; Sams, C.E. Irradiance from distinct wavelength light-emitting diodes affect secondary metabolites in kale. HortScience 2008, 43, 2243–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.I.; Kim, H.Y.; Kim, J.; Son, J.E. Quantitative analysis of UV-B radiation interception and bioactive compound contents in kale by leaf position according to growth progress. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 667456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, R.; Gao, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Song, S.; Su, W.; Liu, H. Supplemental UV-A affects growth and antioxidants of Chinese kale baby-leaves in artificial light plant factory. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdaguer, D.; Jansen, M.A.; Llorens, L.; Morales, L.O.; Neugart, S. UV-A radiation effects on higher plants: Exploring the known unknown. Plant Sci. 2017, 255, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellmann, E. UV radiation in photomorphogenesis. In Photomorphogenesis, 1st ed.; Shropshire, W., Mohr, H., Eds.; Springer Berlin: Heidelberg, Germany, 1983; Volume 16, pp. 745–756. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, C.R; Gies, H.P.; Lugg, D.J.; Toomey, S.; Tomlinson, D.W. The measurement of solar ultraviolet radiation. Mutat. Res. 1998, 422, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loconsole, D.; Santamaria, P. UV lighting in horticulture: A sustainable tool for improving production quality and food safety. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Oh, M.M.; Son, K.H. Short-term ultraviolet (UV)-A light-emitting diode (LED) radiation improves biomass and bioactive compounds of kale. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porra, R.J.; Thomson, W.A.; Kriedemann, P.E. Determination of accurate extinction coefficients and simultaneous equations for assaying chlorophylls a and b extracted with four different solvents: verification of the concentration of chlorophyll standards by atomic absorption spectroscopy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1989, 976, 384–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellburn, A.R. The spectral determination of chlorophyll a and b, as well total carotenoids, using various solvents with spectrophotometers of different resolution. J. Plant Physiol. 1994, 144, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, K.; Johnson, G.N. Chlorophyll fluorescence—a practical guide. J. Exp. Bot. 2000, 51, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Photon Systems Instruments. Instruction Guide PolyPen RP410; PSI: Drásov, Czech Republic, 2023; pp. 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ağlar, E.; Saraçoğlu, O. Role of the foliar fertilization treatments on quality attributes of sweet cherry fruits (Prunus avium). Akademik Ziraat Dergisi 2018, 7, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, S.E.; Irving, D.E.; Milham, P.J. A critical evaluation of on-farm rapid tests for measuring nitrate in leafy vegetables. Sci. Hortic. 2012, 134, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 7, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourith, N.; Kanlayavattanakul, M.; Chanpirom, S. Free radical scavenging efficacy of Tamarind seed coat and its cosmetics application. J. Health Res. 2009, 23, 159–162. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, S.R.; Langton, F.A. Photoperiod and plant growth: a review. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotech. 2005, 80, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, G. Inanimate Life, 1st ed; Milne Library Publishing: Geneseo, USA, 2021; pp. 390–404. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, S.; Kim, J.E.; Zhen, S.; Kim, J. Mild-intensity UV-A radiation applied over a long duration can improve the growth and phenolic contents of sweet basil. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 858433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.J.; Son, J.E.; Oh, M.M. Growth and phenolic compounds of Lactuca sativa L. grown in a closed-type plant production system with UV-A, -B, or -C lamp. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2014, 94, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.; Son, J.E.; Oh, M. Growth and phenolic content of sowthistle grown in a closed-type plant production system with a UV-A or UV-B lamp. Hort. Environ. Biotechnol. 2013, 54, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayakumar, M.; Amudha, P.; Kulandaivelu, G. Changes in growth and yield of Phaseolus mungo L. induced by UV-A and UV-B enhanced radiation. J. Plant Biol. 2003, 46, 59–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štroch, M.; Materová, Z.; Vrábl, D.; Karlický, V.; Šigut, L.; Nezval, J.; Špunda, V. Protective effect of UV-A radiation during acclimation of the photosynthetic apparatus to UV-B treatment. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 96, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yongcheng, C.; Li, T.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zou, J.; Bian, Z.; Wen, X. UVA radiation is beneficial for yield and quality of indoor cultivated lettuce. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1563. [Google Scholar]

- Tezuka, T.; Yamaguchi, F.; Ando, Y. Physiological activation in radish plants by UV-A radiation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 1994, 24, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohidi-Moghadam, H.R.; Ghooshchi, F.; Jamshidpour, F.; Zahedi, H. Effect of UV radiation and elevated CO2 on physiological attributes of canola (Brassica napus L.) grown under water deficit stress. Polish J. Environ. Stud. 2012, 21, 1417–1427. [Google Scholar]

- Dáder, B.; Gwynn-Jones, D.; Moreno, A.; Winters, A.; Fereres, A. Impact of UV-A radiation on the performance of aphids and whiteflies and on the leaf chemistry of their host plants. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2014, 138, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahandani, E.A.; Fazilati, M.; Boghozian, A.; Ahandani, M.A. Effect of ultraviolet (UV) radiation bonds on growth and chlorophyll content of Dracocephalum moldavica L Herb. J. Biomol. Res. Ther. 2019, 8, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Mahdavian, K.; Kalantari, K.M.; Ghorbanli, M.; Torkzade, M. The effects of salicylic acid on pigment contents in ultraviolet radiation stressed pepper plants. Biol. Plant. 2008, 52, 170–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teramura, A.H.; Sullivan, J.H. Effects of UV-B radiation on photosynthesis and growth of terrestrial plants. Photosynth. Res. 1994, 39, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lidon, F.J.; Reboredo, F.H.; Silva, M.M.A.; Duarte, M.P.; Ramalho, J.C. Impact of UV-B radiation on photosynthesis-an overview. Emir. J. Food Agric. 2012, 24, 546–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantha, S.V.; Johnson, G.A.; Day, T.A. Evidence from action and fluorescence spectra that UV-induced violet-blue-green fluorescence enhances leaf photosynthesis. Photochem. Photobiol. 2001, 73, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Erwin, J.; Gesick, E. Photosynthetic responses of swiss chard, kale, and spinach cultivars to irradiance and carbon dioxide concentration. HortScience 2017, 52, 706–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataria, S.; Guruprasad, K.N. Intraspecific variations in growth, yield and photosynthesis of sorghum varieties to ambient UV (280-400 nm) radiation. Plant Sci. 2012, 196, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llusia, J.; Llorens, L.; Bernal, M.; Verdaguer, D.; Penuelas, J. Effects of UV radiation and water limitation on the volatile terpene emission rates, photosynthesis rates, and stomatal conductance in four Mediterranean species. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2012, 34, 757–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björkman, O.; Demmig, B. Photon yield of O2 evolution and chlorophyll fluorescence characteristics at 77 K among vascular plant of diverse origins. Planta 1987, 170, 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolb, C.A.; Kaser, M.A.; Kopecký, J.; Zotz, G.; Riederer, M.; Pfundel, E.E. Effects of natural intensities of visible and ultraviolet radiation on epidermal ultraviolet screening and photosynthesis in grape leaves. Plant Physiol. 2001, 127, 863–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rochaix, J. Regulation of photosynthetic electron transport. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 2011, 1807, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamon, J.; Peñuelas, J.; Field, C. A narrow-waveband spectral index that tracks diurnal changes in photosynthetic efficiency. Remote Sens. Environ. 1992, 41, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsoulas, N.; Elvanidi, A.; Ferentinos, K.P.; Kacira, M.; Bartzans, T.; Kittas, C. Crop reflectance monitoring as a tool for water stress detection in greenhouses: A review. Biosyst. Eng. 2016, 151, 374–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soengas, P.; Madloo, P.; Lema, M. Spectral reflectance indexes reveal differences in the physiological status of brassica oleracea with contrasting glucosinolate content under biotic stress. Plants 2023, 12, 2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.H.; Fu, X.; Lu, M.; Wei, B.D. A transcriptomic perspective on the effect of UV irradiation on vitamin C content in pea sprouts. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 42, e09022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.Y.; Häder, D.P. UV-B-induced formation of reactive oxygen species and oxidative damage of the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp.: protective effects of ascorbic acid and N-acetyl-L-cysteine. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2002, 66, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Gui, M.; Tian, X.; Xin, X.; Wang, T.; Li, J. Effects of UV-B on vitamin C, phenolics, flavonoids and their related enzyme activities in mung bean sprouts (Vigna radiata). Int. J. Food Sci. Tech. 2017, 52, 827–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Zhang, Y.; Song, S.; Su, W.; Hao, Y.; Liu, H. UV-A and FR irradiation improves growth and nutritional properties of lettuce grown in an artificial light plant factory. Food Chem. 2021, 345, 128727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthria, D.L.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Krizek, D.T. Content of total phenolics and phenolic acids in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) fruits as influenced by cultivar and solar UV radiation. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2006, 19, 771–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, J.C.D.; Buide, M.L.; Whittall, J.B.; Valladares, F.; Narbona, E. UV radiation increases phenolic compound protection but decreases reproduction in Silene littorea. PloS One 2020, 15, e0231611. [Google Scholar]

- Vanhaelewyn, L.; Van Der Straeten, D. , De Coninck, B.; Vandenbussche, F. Ultraviolet radiation from a plant perspective: The plant-microorganism context. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 597642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharpless, C.M.; Linden, K.G. UV photolysis of nitrate: effects of natural organic matter and dissolved inorganic carbon and implications for UV water disinfection. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2001, 35, 2949–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nedunchezhian, N.; Annamalainathan, K.; Kulandaivelu, G. Induction of heat shock-like proteins in Vigna sinensis seedlings growing under ultraviolet-B (280-320 nm) enhanced radiation. Physiol. Plant. 1992, 85, 503–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Samraj, S.; Jiménez, J.; Gómez, C.; Liu, T.; Begcy, K. Genome-wide identification of heat shock factors and heat shock proteins in response to UV and high intensity light stress in lettuce. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, M.V.; Paliyath, G.; Ormrod, D.P. Ultraviolet-B- and ozone-induced biochemical changes in antioxidant enzymes of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant physiol. 1996, 110, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erkan, M.; Wang, S.Y.; Wang, C.Y. Effect of UV treatment on antioxidant capacity, antioxidant enzyme activity and decay in strawberry fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2008, 48, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berli, F.J.; Moreno, D.; Piccoli, P.; Hespanhol-Viana, L.; Silva, M.F.; Bresssan-Smith, R.; Cavagnaro, J.B.; Bottini, R. Abscisic acid is involved in the response of grape (Vitis vinifera L.) cv. Malbec leaf tissues to ultraviolet-B radiation by enhancing ultraviolet-absorbing compounds, antioxidant enzymes and membrane sterols. Plant Cell Environ. 2010, 33, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| UV-A (W/m2) | Shoot fresh weight (g) | Root fresh weight (g) | Shoot dry weight (g) | Root dry weight (g) | Fresh weight/Dry weight | Stem height (cm) | Canopy width (cm) | Stem diameter (mm) | Number of leaves | Leaf greenness index (SPAD unit) |

| 0 | 106.88 ± 22.31 b | 20.17 ± 3.89 ab | 7.98 ± 1.67 b | 1.08 ± 0.21 c | 14.02 ± 0.08 b | 36.80 ± 4.88 b | 44.00 ± 4.28 b | 8.37 ± 1.11 | 15.67 ± 2.16 ab | 43.13 ± 1.68 |

| 5 | 143.84 ± 24.41 a | 24.88 ± 4.25 ab | 10.53 ± 1.79 a | 2.12 ± 0.36 a | 13.36 ± 0.02 c | 41.00 ± 3.41 ab | 46.67 ± 6.30 ab | 9.52 ± 2.04 | 16.50 ± 1.97 a | 41.08 ± 4.75 |

| 10 | 157.90 ± 5.43 a | 17.58 ± 1.95 b | 11.72 ± 0.40 a | 1.69 ± 0.19 b | 13.09 ± 0.04 c | 44.82 ± 1.17 a | 54.54 ± 2.30 a | 9.13 ± 1.39 | 15.33 ± 1.63 ab | 41.02 ± 1.36 |

| 15 | 111.73 ± 24.29 b | 15.40 ± 2.19 b | 6.08 ± 1.32 b | 1.23 ± 0.18 c | 17.39 ± 0.22 a | 41.80 ± 4.34 ab | 48.04 ± 7.15 ab | 9.02 ± 2.03 | 14.50 ± 0.55 b | 43.55 ± 2.15 |

| Sig. | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | * | * | ns | * | ns |

| UV-A (W/m2) | Total Chl (mg/gFW) |

Chl a (mg/gFW) |

Chl b (mg/gFW) |

Chl a/b | Carotenoids (mg/gFW) |

| 0 | 8.90 ± 1.56 | 6.32 ± 1.14 | 2.58 ± 0.44 | 2.45 ± 0.14 | 0.94 ± 0.41 |

| 5 | 7.48 ± 0.67 | 5.52 ± 0.55 | 1.95 ± 0.17 | 2.83 ± 0.22 | 0.97 ± 0.08 |

| 10 | 7.60 ± 1.85 | 5.48 ± 1.34 | 2.12 ± 0.51 | 2.60 ± 0.21 | 1.03 ± 0.27 |

| 15 | 8.18 ± 0.76 | 5.96 ± 0.65 | 2.22 ± 0.15 | 2.68 ± 0.21 | 1.15 ± 0.16 |

| Sig. | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).