Submitted:

05 June 2024

Posted:

07 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. The Wildfire/Portuguese Rural Fire Dataset

2.3. The Climate/Atmospheric Dataset

- air temperature at 2 m height (hereafter, T2m);

- wind speed and direction at 10 m (hereafter, W10m);

- relative humidity at 850 hPa which corresponds to about 1500 m of altitude (hereafter, RH);

- total precipitation (hereafter, TP).

2.3. The Methodology

3. Results and Discussion

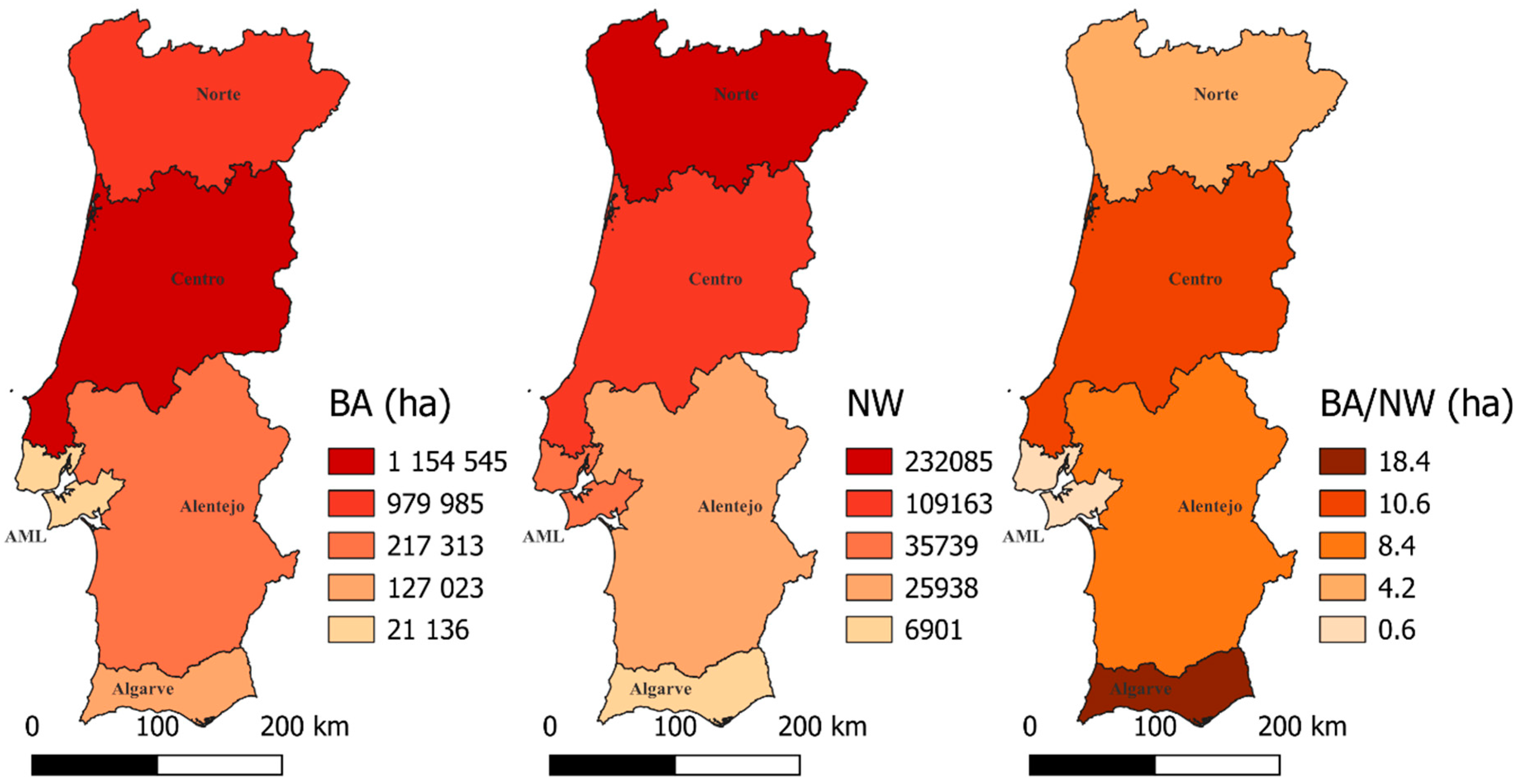

3.1. The Spatial Distribution of the Wildfire Incidence

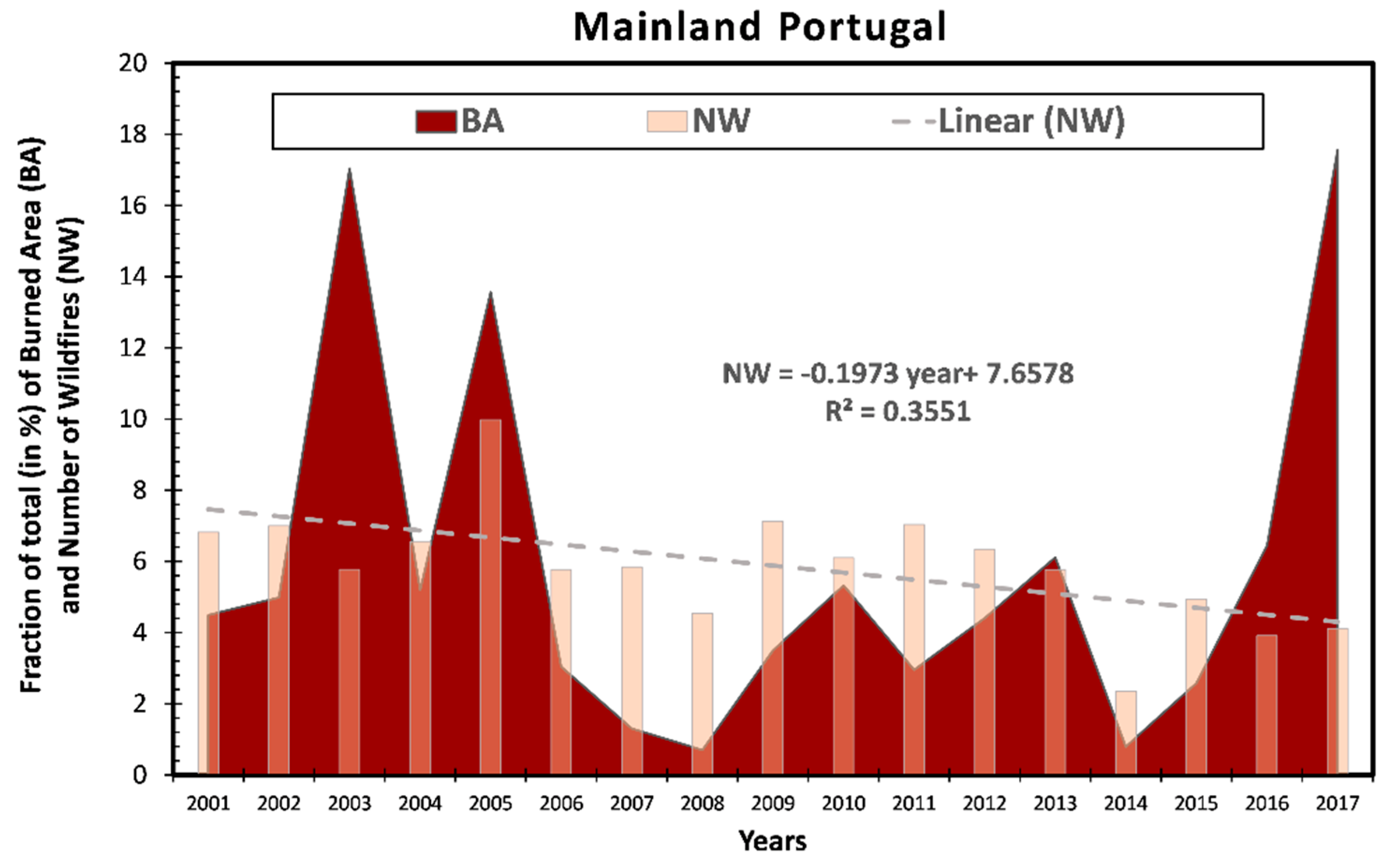

3.2. The Interannual Variability of Wildfire Incidence

3.3. The Intra-Annual Variability of Wildfire Incidence

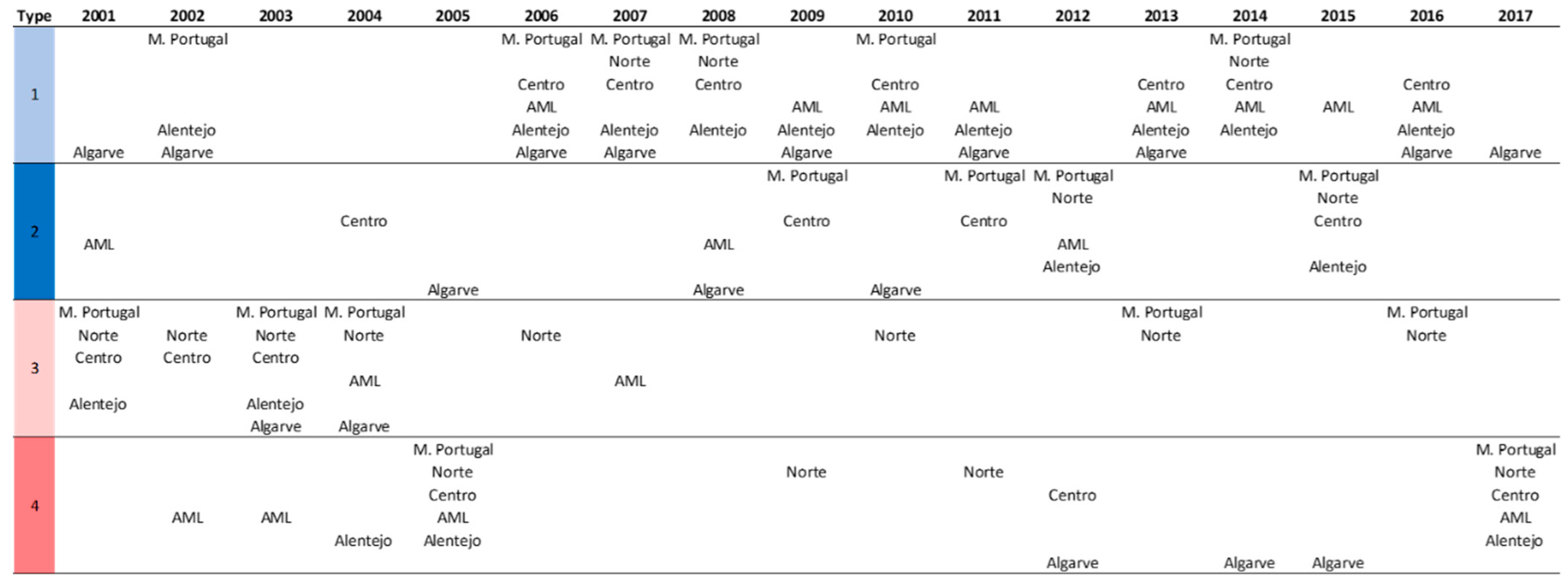

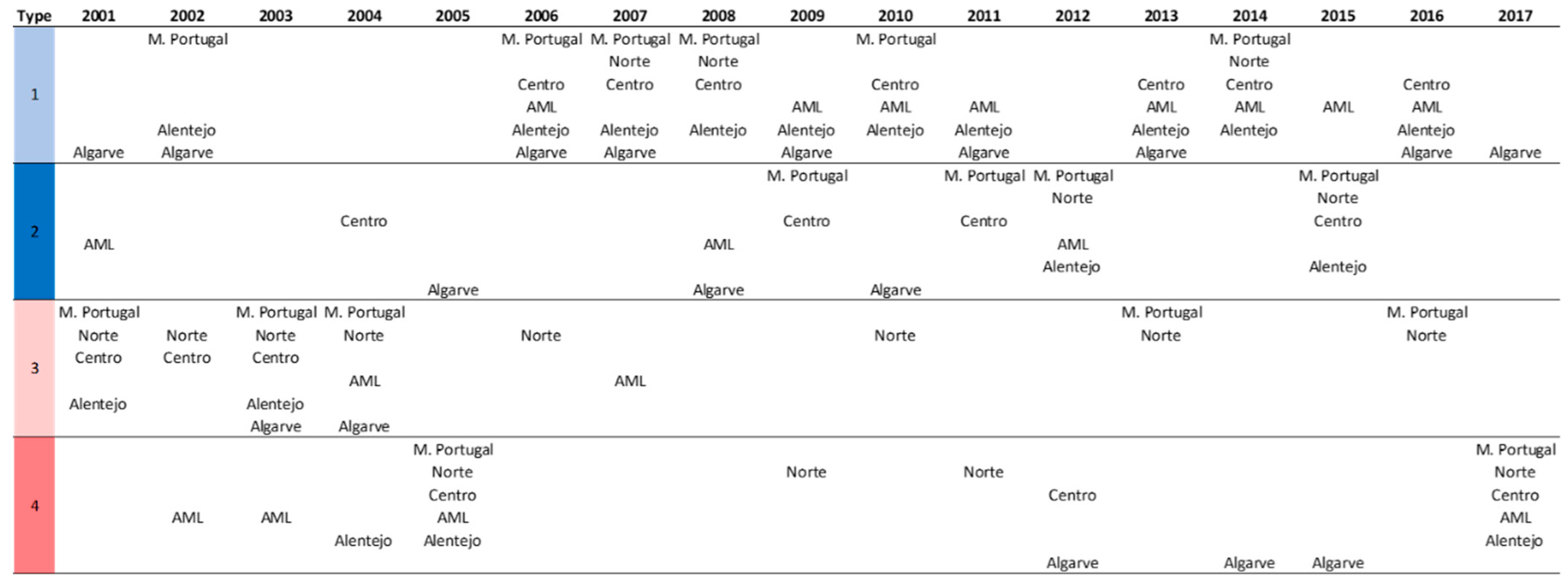

3.4. Variability of the Annual Cycle of the Wildfire Incidence

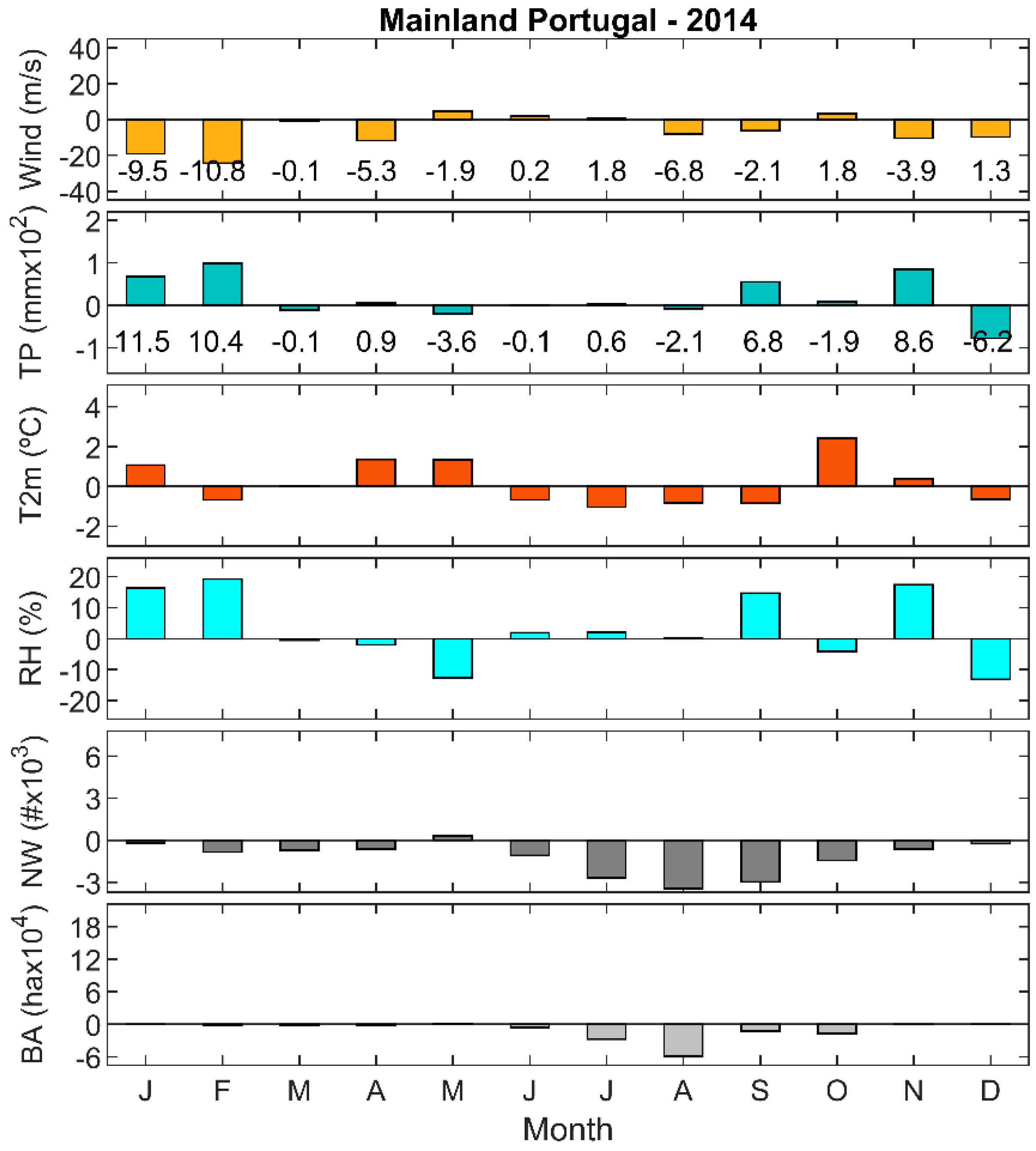

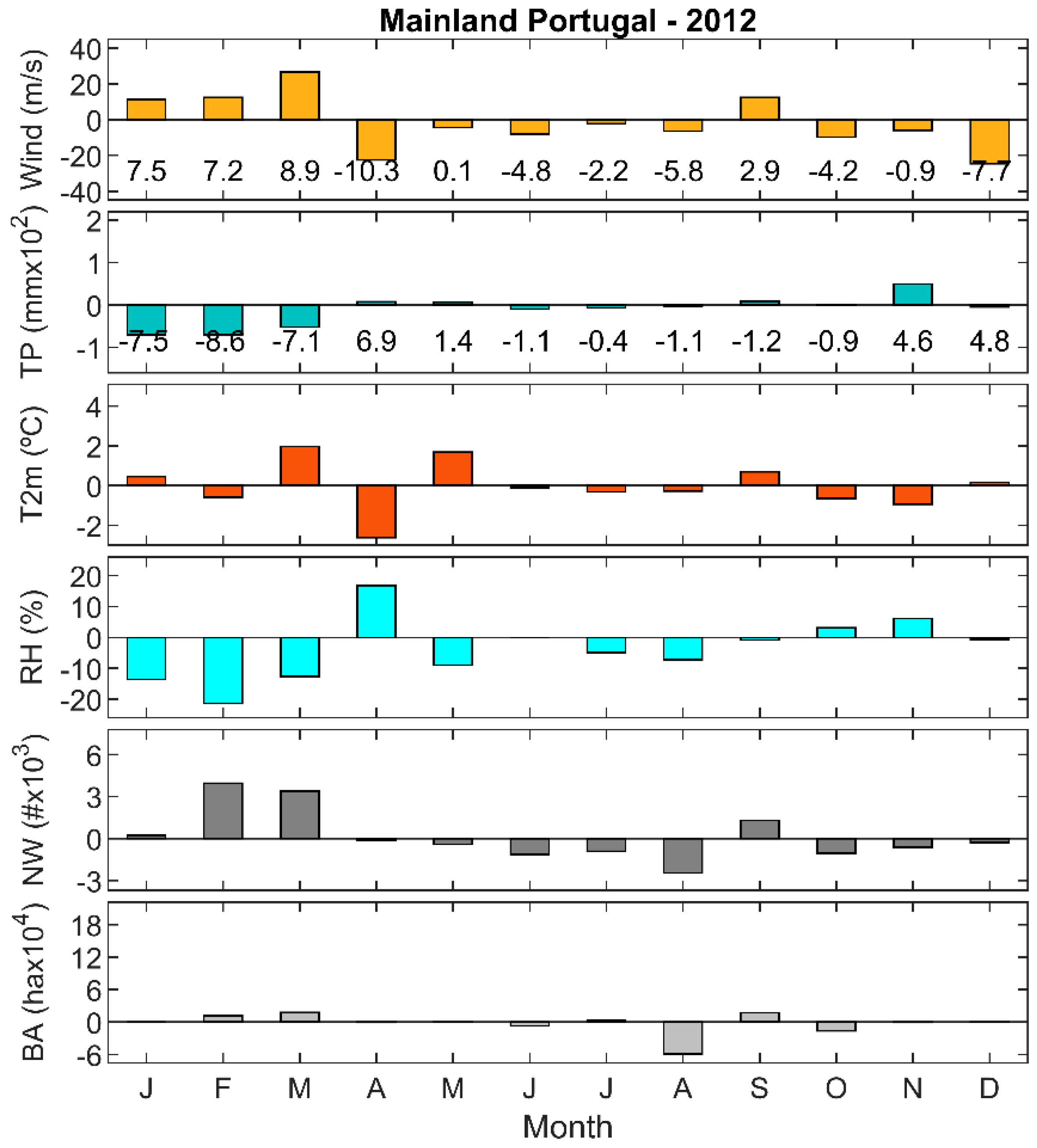

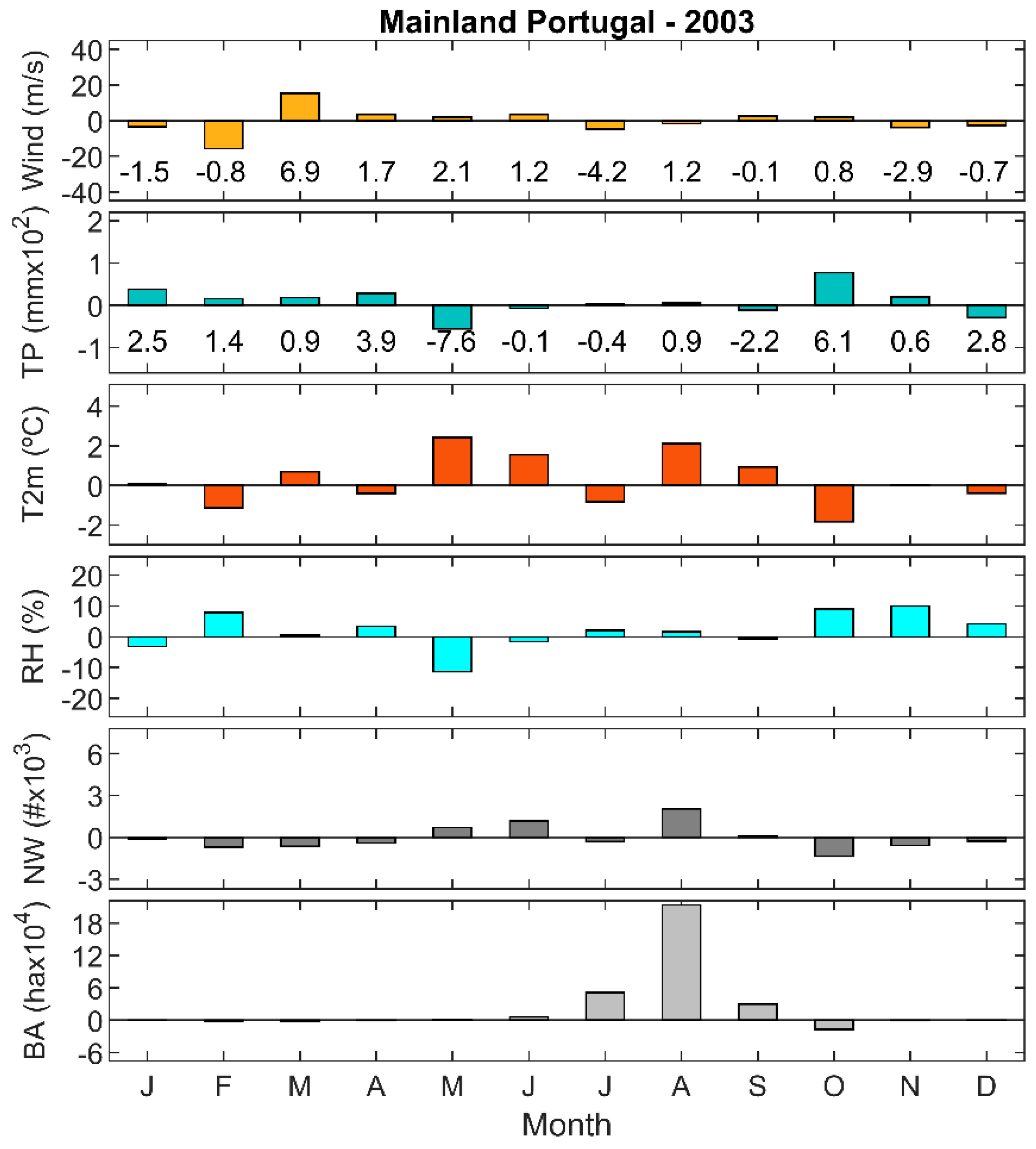

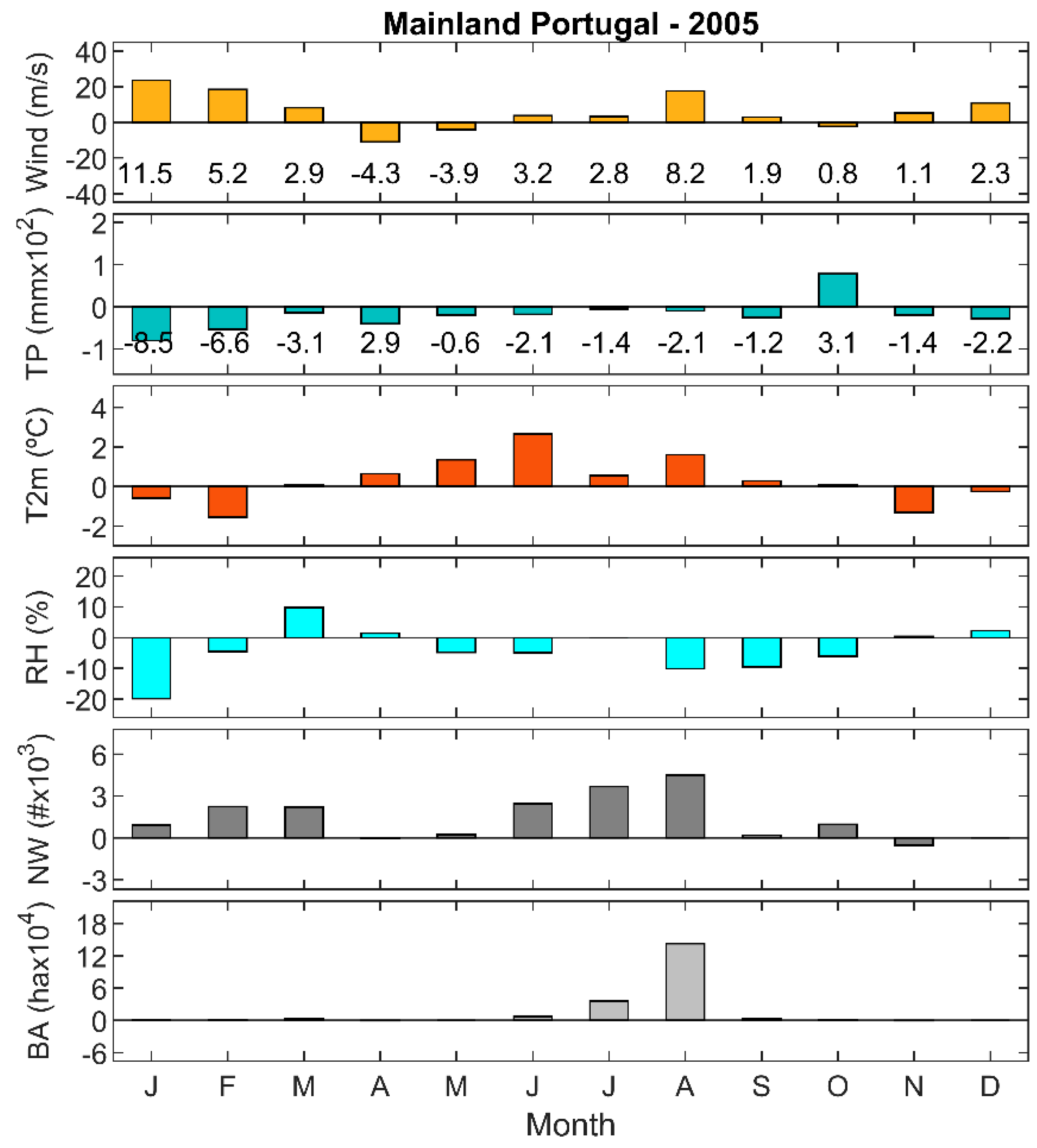

3.5. Cause of Inter-Annual Variability of Intra-Annual Variability in the Incidence of Wildfires

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pereira, M.G.; Parente, J.; Amraoui, M.; Oliveira, A.; Fernandes, P.M. The Role of Weather and Climate Conditions on Extreme Wildfires. Extrem. Wildfire Events Disasters Root Causes New Manag. Strateg. 2020, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizundia-Loiola, J.; Otón, G.; Ramo, R.; Chuvieco, E. A Spatio-Temporal Active-Fire Clustering Approach for Global Burned Area Mapping at 250 m from MODIS Data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 236, 111493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, V.; Stocker, T.; Qin, D.; Dokken, D.; Ebi, K.; Mach, K.; Plattner, G.; Allen, S.; Tignor, M.; Midgley, P. IPCC, 2012: Glossary of Terms. In Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation; Field, C.B., V. Barros, T.F. Stocker, D. Qin, D.J. Dokken, K.L. Ebi, M.D. Mastrandrea, K.J. Mach, G.-K. Plattner, S.K. Allen, M. Tignor, and P.M.M., Ed.; Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 555–564.

- Bowman, D.M.J.S.; Balch, J.K.; Artaxo, P.; Bond, W.J.; Carlson, J.M.; Cochrane, M.A.; D’Antonio, C.M.; DeFries, R.S.; Doyle, J.C.; Harrison, S.P.; et al. Fire in the Earth System. Science (80-. ). 2009, 324, 481–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, K.; Touge, Y. Characterization of Global Wildfire Burned Area Spatiotemporal Patterns and Underlying Climatic Causes. Sci. Reports 2022 121 2022, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, Y. Global Fire Activity Patterns (1996–2006) and Climatic Influence: An Analysis Using the World Fire Atlas. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2008, 8, 1911–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillakis, M.; Voulgarakis, A.; Rovithakis, A.; Seiradakis, K.D.; Koutroulis, A.; Field, R.D.; Kasoar, M.; Papadopoulos, A.; Lazaridis, M. Climate Drivers of Global Wildfire Burned Area. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 045021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldersley, A.; Murray, S.; Cornell, S. Global and Regional Analysis of Climate and Human Drivers of Wildfire. Sci. Total Environ. 2011, 409, 3472–3481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hantson, S.; Pueyo, S.; Chuvieco, E. Global Fire Size Distribution Is Driven by Human Impact and Climate. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2015, 24, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannigan, M.D.; Krawchuk, M.A.; De Groot, W.J.; Wotton, B.M.; Gowman, L.M. Implications of Changing Climate for Global Wildland Fire. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2009, 18, 483–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.G.; Calado, T.J.J.T.; DaCamara, C.C.C.C.; Calheiros, T. Effects of Regional Climate Change on Rural Fires in Portugal. Clim. Res. 2013, 57, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parente, J.; Pereira, M.G.M.G.; Tonini, M. Space-Time Clustering Analysis of Wildfires: The Influence of Dataset Characteristics, Fire Prevention Policy Decisions, Weather and Climate. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 559, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venäläinen, A.; Korhonen, N.; Hyvärinen, O.; Koutsias, N.; Xystrakis, F.; Urbieta, I.R.; Moreno, J.M. Temporal Variations and Change in Forest Fire Danger in Europe for 1960-2012. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2014, 14, 1477–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telesca, L.; Pereira, M.G. Time-Clustering Investigation of Fire Temporal Fluctuations in Portugal. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2010, 10, 661–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parente, J.; Amraoui, M.; Menezes, I.; Pereira, M.G.G. Drought in Portugal: Current Regime, Comparison of Indices and Impacts on Extreme Wildfires. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 685, 150–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parente, J.; Pereira, M.G.; Amraoui, M.; Fischer, E.M. Heat Waves in Portugal: Current Regime, Changes in Future Climate and Impacts on Extreme Wildfires. Elsevier 2018, 631–632, 534–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.G.; Trigo, R.M.; Da Camara, C.C.; Pereira, J.M.C.; Leite, S.M. Synoptic Patterns Associated with Large Summer Forest Fires in Portugal. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2005, 129, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigo, R.M.; Pereira, J.M.C.; Pereira, M.G.; Mota, B.; Calado, T.J.; Dacamara, C.C.; Santo, F.E. Atmospheric Conditions Associated with the Exceptional Fire Season of 2003 in Portugal. Int. J. Climatol. 2006, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moritz, M.A.; Parisien, M.-A.; Batllori, E.; Krawchuk, M.A.; Van Dorn, J.; Ganz, D.J.; Hayhoe, K.; Moritz, M.A.; Parisien, M.-A.; Batllori, E.; et al. Climate Change and Disruptions to Global Fire Activity. Ecosphere 2012, 3, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawchuk, M.A.; Moritz, M.A.; Parisien, M.A.; Van Dorn, J.; Hayhoe, K. Global Pyrogeography: The Current and Future Distribution of Wildfire. PLoS One 2009, 4, e5102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, E.; Grégoire, J.-M.; Pereira, J.M.C. Climate and Vegetation as Driving Factors in Global Fire Activity. 2000, 171–191. [CrossRef]

- Bedia, J.; Herrera, S.; Gutiérrez, J.M.; Benali, A.; Brands, S.; Mota, B.; Moreno, J.M. Global Patterns in the Sensitivity of Burned Area to Fire-Weather: Implications for Climate Change. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2015, 214–215, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archibald, S.; Lehmann, C.E.R.; Gómez-Dans, J.L.; Bradstock, R.A. Defining Pyromes and Global Syndromes of Fire Regimes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013, 110, 6442–6447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abatzoglou, J.T.; Williams, A.P.; Boschetti, L.; Zubkova, M.; Kolden, C.A. Global Patterns of Interannual Climate–Fire Relationships. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2018, 24, 5164–5175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.; Parente, J.; Amraoui, M.; Pereira, M.; Fernandes, P. Global-Scale Analysis of Wildfires; 2018; Vol. 20;

- Wasserman, T.N.; Mueller, S.E. Climate Influences on Future Fire Severity: A Synthesis of Climate-Fire Interactions and Impacts on Fire Regimes, High-Severity Fire, and Forests in the Western United States. Fire Ecol. 2023 191 2023, 19, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeley, J.E.; Syphard, A.D. Different Historical Fire–Climate Patterns in California. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2017, 26, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgis, M.A.; Zeballos, S.R.; Carbone, L.; Zimmermann, H.; von Wehrden, H.; Aguilar, R.; Ferreras, A.E.; Tecco, P.A.; Kowaljow, E.; Barri, F.; et al. A Review of Fire Effects across South American Ecosystems: The Role of Climate and Time since Fire. Fire Ecol. 2021 171 2021, 17, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littell, J.S.; Gwozdz, R.B. Climatic Water Balance and Regional Fire Years in the Pacific Northwest, USA: Linking Regional Climate and Fire at Landscape Scales. 2011, 117–139. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhang, Z.; Ying, H.; Chen, J.; Zhen, S.; Wang, X.; Shan, Y. The Spatial Patterns of Climate-Fire Relationships on the Mongolian Plateau. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2021, 308–309, 108549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fréjaville, T.; Curt, T. Spatiotemporal Patterns of Changes in Fire Regime and Climate: Defining the Pyroclimates of South-Eastern France (Mediterranean Basin). Clim. Change 2015, 129, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeley, J.E.; Syphard, A.D. Climate Change and Future Fire Regimes: Examples from California. Geosci. 2016, Vol. 6, Page 37 2016, 6, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, E.Q.; Swetnam, T.W. Historical Fire–Climate Relationships of Upper Elevation Fire Regimes in the South-Western United States. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2013, 22, 588–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calheiros, T.; Nunes, J.P.; Pereira, M.G. Recent Evolution of Spatial and Temporal Patterns of Burnt Areas and Fire Weather Risk in the Iberian Peninsula. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2020, 287, 107923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.G.; Malamud, B.D.; Trigo, R.M.; Alves, P.I. The History and Characteristics of the 1980-2005 Portuguese Rural Fire Database. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2011, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Terrén, D.M.; Xanthopoulos, G.; Diakakis, M.; Ribeiro, L.; Caballero, D.; Delogu, G.M.; Viegas, D.X.; Silva, C.A.; Cardil, A. Analysis of Forest Fire Fatalities in Southern Europe: Spain, Portugal, Greece and Sardinia (Italy). Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2019, 28, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parente, J.; Pereira, M.G.J.M.G. Structural Fire Risk: The Case of Portugal. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 573, 883–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, H.E.; Zimmermann, N.E.; McVicar, T.R.; Vergopolan, N.; Berg, A.; Wood, E.F. Present and Future Köppen-Geiger Climate Classification Maps at 1-Km Resolution. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calheiros, T.; Pereira, M.G.; Nunes, J.P. Assessing Impacts of Future Climate Change on Extreme Fire Weather and Pyro-Regions in Iberian Peninsula. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 754, 142233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Chen, H.W. Using the Köppen Classification to Quantify Climate Variation and Change: An Example for 1901–2010. Environ. Dev. 2013, 6, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2012.

- WMO World Meteorological Organization. Guidelines on the Calculation of Climate Normals. 2017, 16.

- Gent, P.R. Climate Normals: Are They Always Communicated Correctly? Weather Forecast. 2022, 37, 1531–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MEFISTO Forest Fire Multilingual Glossary Portuguese Version 2018.

- Glossary of Wildland Fire, PMS 205 | NWCG Available online:. Available online: https://www.nwcg.gov/glossary-of-wildland-fire-pms-205 (accessed on 11 August 2021).

- Stacey, R. 2012.

- Bowman, D.M.J.S.; Kolden, C.A.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Johnston, F.H.; van der Werf, G.R.; Flannigan, M. Vegetation Fires in the Anthropocene. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020 110 2020, 1, 500–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.M.B.; Remenyi, T.A.; Williamson, G.J.; Bindoff, N.L.; Bowman, D.M.J.S. Climate–Vegetation–Fire Interactions and Feedbacks: Trivial Detail or Major Barrier to Projecting the Future of the Earth System? Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2016, 7, 910–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rundel, P.W.; Arroyo, M.T.K.; Cowling, R.M.; Keeley, J.E.; Lamont, B.B.; Vargas, P. Mediterranean Biomes: Evolution of Their Vegetation, Floras, and Climate. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2016, 47, 383–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, Z.J.; Pellegrini, A.F.A.; Refsland, T.K.; Andrioli, R.J.; Bowles, M.L.; Brockway, D.G.; Burrows, N.; Franco, A.C.; Hallgren, S.W.; Hobbie, S.E.; et al. Herbaceous Vegetation Responses to Experimental Fire in Savannas and Forests Depend on Biome and Climate. Ecol. Lett. 2023, 26, 1237–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Parisien, M.-A.; Taylor, S.W.; -, al; Hanan, E. J.; Ren, J.; Tague, C.L.; Alberta, in; Ellen Whitman, C.; Parks, S.A.; et al. Measurement of Inter- and Intra-Annual Variability of Landscape Fire Activity at a Continental Scale: The Australian Case. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 035003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, S.T.; Fornazari, T.; Cóstola, A.; Morellato, L.P.C.; Silva, T.S.F. Drivers of Fire Occurrence in a Mountainous Brazilian Cerrado Savanna: Tracking Long-Term Fire Regimes Using Remote Sensing. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 78, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amraoui, M.; Parente, J.; Pereira, M. Fire Seasons in Portugal: The Role of Weather and Climate. In Advances in forest fire research 2018; Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra, 2018; pp. 472–479.

- Saha, M. V.; Scanlon, T.M.; D’Odorico, P. Climate Seasonality as an Essential Predictor of Global Fire Activity. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2019, 28, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amraoui, M.; Pereira, M.G.; DaCamara, C.C.; Calado, T.J. Atmospheric Conditions Associated with Extreme Fire Activity in the Western Mediterranean Region. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 524–525, 524–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amraoui, M.; Liberato, M.L.R.; Calado, T.J.; DaCamara, C.C.; Coelho, L.P.; Trigo, R.M.; Gouveia, C.M. Fire Activity over Mediterranean Europe Based on Information from Meteosat-8. For. Ecol. Manage. 2013, 294, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calheiros, T.; Benali, A.; Pereira, M.; Silva, J.; Nunes, J. Drivers of Extreme Burnt Area in Portugal: Fire Weather and Vegetation. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2022, 22, 4019–4037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, C.; Couto, F.T.; Filippi, J.B.; Baggio, R.; Salgado, R. Modelling Pyro-Convection Phenomenon during a Mega-Fire Event in Portugal. Atmos. Res. 2023, 290, 106776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoinka, K.P.; Carvalho, A.; Miranda, A.I.; Hoinka, K.P.; Carvalho, A.; Miranda, A.I. Regional-Scale Weather Patterns and Wildland Fires in Central Portugal. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2009, 18, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turco, M.; Jerez, S.; Augusto, S.; Tarín-Carrasco, P.; Ratola, N.; Jiménez-Guerrero, P.; Trigo, R.M. Climate Drivers of the 2017 Devastating Fires in Portugal. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonini, M.; Pereira, M.G.; Parente, J.; Vega Orozco, C. Evolution of Forest Fires in Portugal: From Spatio-Temporal Point Events to Smoothed Density Maps. Nat. Hazards 2017, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottek, M.; Grieser, J.; Beck, C.; Rudolf, B.; Rubel, F. World Map of the Köppen-Geiger Climate Classification Updated. Meteorol. Zeitschrift 2006, 15, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peel, M.C.; Finlayson, B.L.; McMahon, T.A. Updated World Map of the Köppen-Geiger Climate Classification. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2007, 11, 1633–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubel, F.; Kottek, M. Observed and Projected Climate Shifts 1901-2100 Depicted by World Maps of the Köppen-Geiger Climate Classification. Meteorol. Zeitschrift 2010, 19, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasari, H.P.; Pozo, I.; Ferri-Yáñez, F.; Araújo, M.B. A Regional Climate Study of Heat Waves over the Iberian Peninsula. Atmos. Clim. Sci. 2014, 04, 841–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.M.; Lu, J. Expansion of the Hadley Cell under Global Warming: Winter versus Summer. J. Clim. 2012, 25, 8387–8393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Previdi, M.; Liepert, B.G. Annular Modes and Hadley Cell Expansion under Global Warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2007, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grise, K.M.; Davis, S.M. Hadley Cell Expansion in CMIP6 Models. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2020, 20, 5249–5268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Vecchi, G.A.; Reichler, T. Expansion of the Hadley Cell under Global Warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2007, 34, 6805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.G.; Caramelo, L.; Orozco, C.V.; Costa, R.; Tonini, M. Space-Time Clustering Analysis Performance of an Aggregated Dataset: The Case of Wildfires in Portugal. Environ. Model. Softw. 2015, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, P.M.; Trigo, R.M.; Pereira, M.G.; Bedia, J.; Gutiérrez, J.M. Different Approaches to Model Future Burnt Area in the Iberian Peninsula. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2015, 202, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigo, R.M.; Sousa, P.M.P.M.; Pereira, M.G.M.G.; Rasilla, D.; Gouveia, C.M.C.M.; Dacamara, C.C.; Sousa, P.M.P.M.; Pereira, M.G.M.G.; Rasilla, D.; Gouveia, C.M.C.M. Modelling Wildfire Activity in Iberia with Different Atmospheric Circulation Weather Types. Int. J. Climatol. 2016, 36, 2761–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Biavati, G.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Rozum, I.; et al. ERA5 Hourly Data on Single Levels from 1979 to Present. Copernicus Clim. Chang. Serv. Clim. data store 2018, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Hirahara, S.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Schepers, D.; et al. The ERA5 Global Reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2020, 146, 1999–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.S.C. dos The Role of Wind Direction on the Occurrence of Large Fire Events in Portugal. 2023.

- DaCamara, C.C.; Trigo, R.M.; Viegas, D. Circulation Weather Types and Their Influence on the Fire Regime in Portugal. Adv. For. FIRE Res. 2018 2018, N/A, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, M.G. A Atmosfera Como Um Laboratório de Física: A Influência Meteorológica Nos Incêndios Rurais. Gaz. física 2022, 45, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Ballabio, D. A MATLAB Toolbox for Principal Component Analysis and Unsupervised Exploration of Data Structure. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2015, 149, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F. The Application of Electronic Computers to Factor Analysis. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1960, 20, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todeschini, R. Data Correlation, Number of Significant Principal Components and Shape of Molecules. The K Correlation Index. Anal. Chim. Acta 1997, 348, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parente, J.; Pereira, M.G.G.; Amraoui, M.; Tedim, F. Negligent and Intentional Fires in Portugal: Spatial Distribution Characterization. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 624, 424–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verde, J.C.; Zêzere, J.L. Assessment and Validation of Wildfire Susceptibility and Hazard in Portugal. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2010, 10, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellnou, M.; Guiomar, N.; Rego, F.; Fernandes, P.M. Fire Growth Patterns in the 2017 Mega Fire Episode of October 15, Central Portugal. Adv. For. fire Res. 2018, 447–453. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, A.M.; Russo, A.; DaCamara, C.C.; Nunes, S.; Sousa, P.; Soares, P.M.M.; Lima, M.M.; Hurduc, A.; Trigo, R.M. The Compound Event That Triggered the Destructive Fires of October 2017 in Portugal. iScience 2023, 26, 106141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beighley, M.; Hyde, A.C. 2018.

- Collins, R.D.; de Neufville, R.; Claro, J.; Oliveira, T.; Pacheco, A.P. Forest Fire Management to Avoid Unintended Consequences: A Case Study of Portugal Using System Dynamics. J. Environ. Manage. 2013, 130, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, M.G.; Nunes, J.P.; Silva, J.M.N.; Calheiros, T. Regional Issues of Fire Management: The Role of Extreme Weather, Climate and Vegetation Type. Fire Hazards Socio-economic Reg. Issues. [CrossRef]

- Nunes, S.A.; Dacamara, C.C.; Turkman, K.F.; Calado, T.J.; Trigo, R.M.; Turkman, M.A.A. Wildland Fire Potential Outlooks for Portugal Using Meteorological Indices of Fire Danger. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2019, 19, 1459–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, A.K.; Campagnolo, M.L.; Silva, J.M.N.; Pereira, J.M.C. A Landsat-Based Atlas of Monthly Burned Area for Portugal, 1984–2021. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2023, 119, 103321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparício, B.A.; Santos, J.A.; Freitas, T.R.; Sá, A.C.L.; Pereira, J.M.C.; Fernandes, P.M. Unravelling the Effect of Climate Change on Fire Danger and Fire Behaviour in the Transboundary Biosphere Reserve of Meseta Ibérica (Portugal-Spain). Clim. Change 2022, 173, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitzsche, N.; Nunes, J.P.; Parente, J. Assessing Post-Fire Water Quality Changes in Reservoirs: Insights from a Large Dataset in Portugal. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanevski, M.; Pereira, M.G.M. Local Fractality: The Case of Forest Fires in Portugal. Phys. A Stat. Mech. its Appl. 2017, 479, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parente, J.; Tonini, M.; Amroui, M.; Pareira, M. Socioeconomic Impacts and Regional Drivers of Fire Management: The Case of Portugal. In Fire Hazards: Socio-economic and regional issues; Rodrigo-Comino, J., Ed.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG, 2023.

- Parente, J.; Tonini, M.; Stamou, Z.; Koutsias, N.; Pereira, M. Quantitative Assessment of the Relationship between Land Use/Land Cover Changes and Wildfires in Southern Europe. Fire 2023, Vol. 6, Page 198 2023, 6, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermitão, T.; Páscoa, P.; Trigo, I.; Alonso, C.; Gouveia, C. Mapping the Most Susceptible Regions to Fire in Portugal. Fire 2023, 6, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Guisuraga, J.M.; Martins, S.; Fernandes, P.M. Characterization of Biophysical Contexts Leading to Severe Wildfires in Portugal and Their Environmental Controls. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trigo, R.M.; DaCamara, C.C. Circulation Weather Types and Their Influence on the Precipitation Regime in Portugal. Int. J. Climatol. A J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2000, 20, 1559–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, A.R.; Santos, J.A. High-Resolution Temperature Datasets in Portugal from a Geostatistical Approach: Variability and Extremes. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2018, 57, 627–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.; Trigo, R.M.; Vega-García, C.; Cardil, A. Identifying Large Fire Weather Typologies in the Iberian Peninsula. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2020, 280, 107789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.D.; Silva, P.; Carmo, M.; Rio, J.; Novo, I. Changes in the Seasonality of Fire Activity and Fire Weather in Portugal: Is the Wildfire Season Really Longer? Meteorol. 2023, Vol. 2, Pages 74-86 2023, 2, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).