Submitted:

05 June 2024

Posted:

06 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains, Media and Experimental Animals

2.2. Protein Domain and Structure Analysis

2.3. Construction of ∆Vp-Porin Deletion Mutant and Phenotype Characterization

2.4. Proteolysis Activity Assay

2.5. Outer Membrane Permeabilization Assay

2.6. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing and Survival Assay

2.7. Motility Assay

2.9. Assessment of Strains Virulence using Tetrahymena thermophila

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Vp-Porin Sequence and Structural Analysis

3.2. Construction and Characterization of the Deletion Mutant of Vp-Porin Gene in V. parahaemolyticus

3.3. Permeabilization of Outer Membranes

3.4. Comparison of Antimicrobial Susceptibility between WT and ∆Vp-Porin Strain

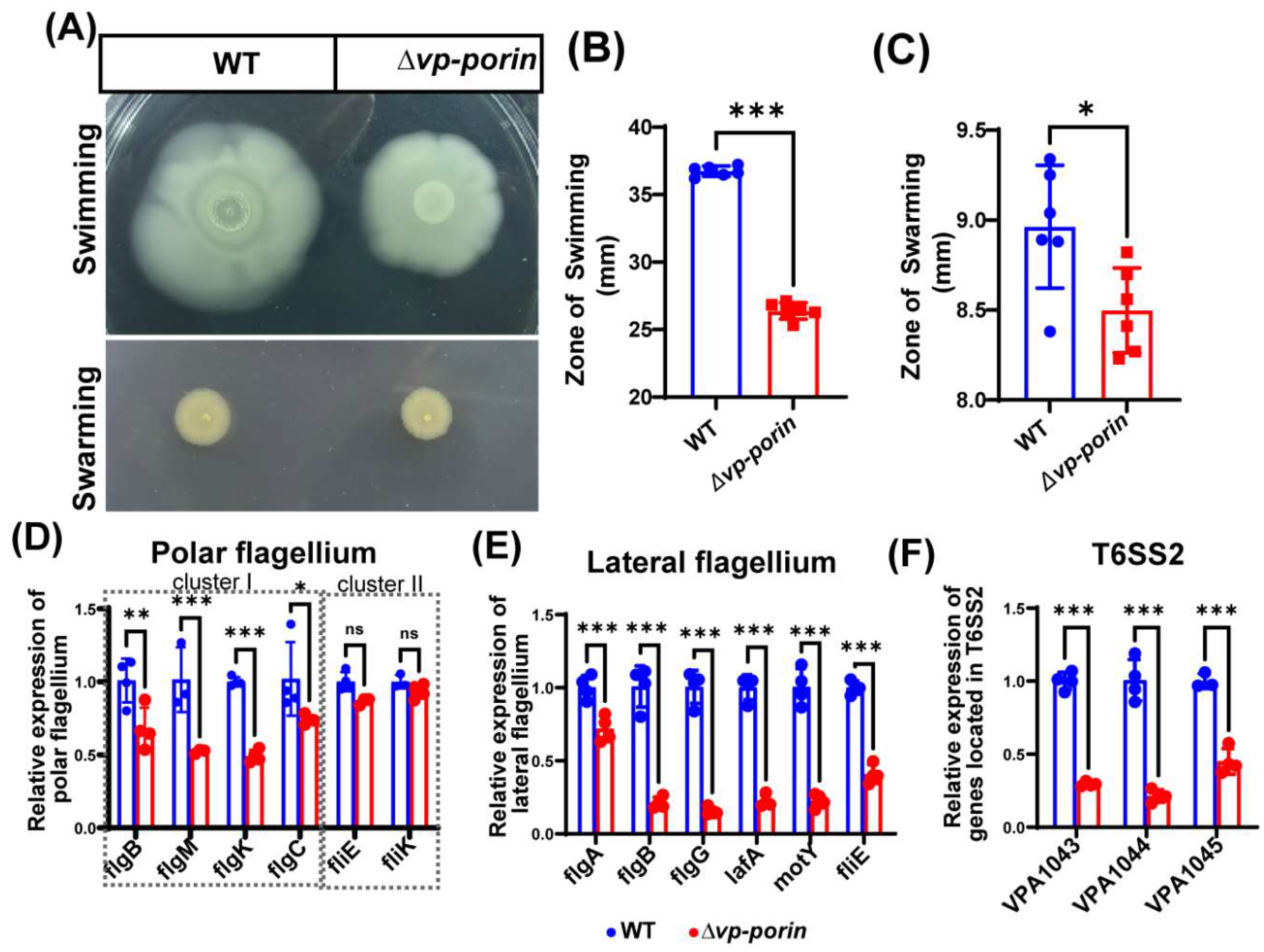

3.5. The Vp-Porin Mutant Exhibits Lower Motility and Decreases Transcription of Polar Flagellar Genes and Lateral Flagellar Genes in V. parahaemolyticus

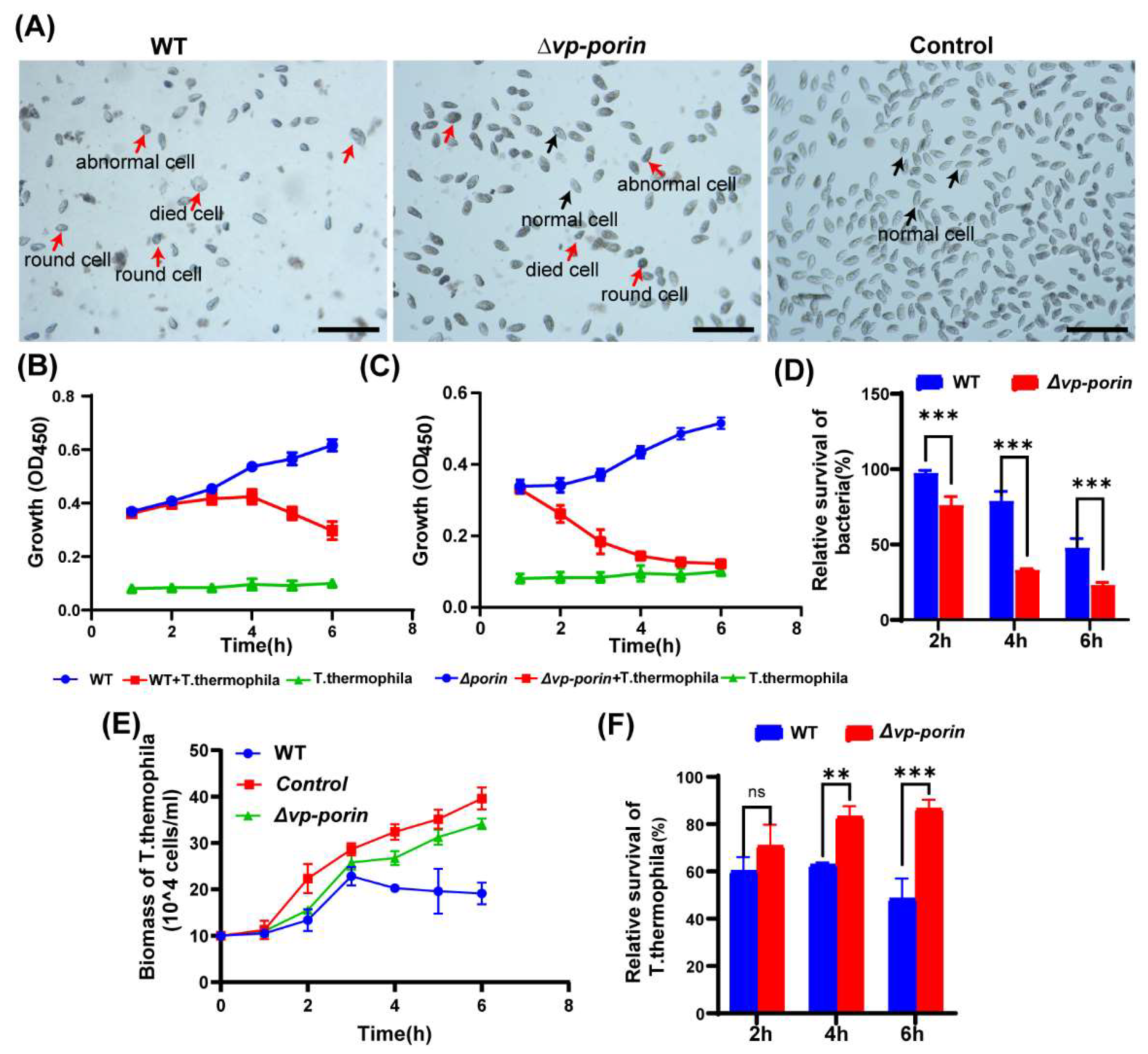

3.6. Assessment of Virulence of ∆Vp-Porin using Tetrahymena

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ghenem, L.; Elhadi, N.; Alzahrani, F.; Nishibuchi, M. Vibrio Parahaemolyticus: A Review on Distribution, Pathogenesis, Virulence Determinants and Epidemiology. Saudi J Med Med Sci 2017, 5, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Meng, H.; Gu, D.; Li, Y.; Jia, M. Molecular mechanisms of Vibrio parahaemolyticus pathogenesis. Microbiol Res 2019, 222, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Cheng, J.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Xie, T. Prevalence, characterization, and antibiotic susceptibility of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from retail aquatic products in North China. BMC Microbiol 2016, 16, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, R.; Sun, J.; Qiu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Xue, X.; Li, X.; Yang, W.; Zhou, D.; Hu, L.; Zhang, Y. The quorum sensing regulator OpaR is a repressor of polar flagellum genes in Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J Microbiol 2021, 59, 651–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haifa-Haryani, W.O.; Amatul-Samahah, M.A.; Azzam-Sayuti, M.; Chin, Y.K.; Zamri-Saad, M.; Natrah, I.; Amal, M.N.A.; Satyantini, W.H.; Ina-Salwany, M.Y. Prevalence, Antibiotics Resistance and Plasmid Profiling of Vibrio spp. Isolated from Cultured Shrimp in Peninsular Malaysia. Microorganisms 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, A.; Wang, Y.; Xu, H.; Jin, X.; Yan, B.; Zhang, W. Antibiotic Resistance and Epidemiology of Vibrio parahaemolyticus from Clinical Samples in Nantong, China, 2018-2021. Infect Drug Resist 2023, 16, 7413–7425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, L.; Hancock, R.E. Adaptive and mutational resistance: role of porins and efflux pumps in drug resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev 2012, 25, 661–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pazhani, G.P.; Chowdhury, G.; Ramamurthy, T. Adaptations of Vibrio parahaemolyticus to Stress During Environmental Survival, Host Colonization, and Infection. Front Microbiol 2021, 12, 737299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pages, J.M.; James, C.E.; Winterhalter, M. The porin and the permeating antibiotic: a selective diffusion barrier in Gram-negative bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol 2008, 6, 893–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLean, R.C.; San Millan, A. The evolution of antibiotic resistance. Science 2019, 365, 1082–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wen, X.; Peng, H.; Peng, R.; Shi, Q.; Xie, X.; Li, L. Outer Membrane Porins Contribute to Antimicrobial Resistance in Gram-Negative Bacteria. Microorganisms 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koebnik, R.; Locher, K.P.; Van Gelder, P. Structure and function of bacterial outer membrane proteins: barrels in a nutshell. Mol Microbiol 2000, 37, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, G.E. The structure of bacterial outer membrane proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta 2002, 1565, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, U.; Lee, C.R. Distinct Roles of Outer Membrane Porins in Antibiotic Resistance and Membrane Integrity in Escherichia coli. Front Microbiol 2019, 10, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornet, C.; Davin-Regli, A.; Bosi, C.; Pages, J.M.; Bollet, C. Imipenem resistance of enterobacter aerogenes mediated by outer membrane permeability. J Clin Microbiol 2000, 38, 1048–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziervogel, B.K.; Roux, B. The binding of antibiotics in OmpF porin. Structure 2013, 21, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya-Torres, A.; Mulvey, M.R.; Kumar, A.; Oresnik, I.J.; Brassinga, A.K.C. The lack of OmpF, but not OmpC, contributes to increased antibiotic resistance in Serratia marcescens. Microbiology (Reading) 2014, 160, 1882–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Huang, D.; Zhou, Q.; Ji, F.; Tan, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, X. The Influence of Outer Membrane Protein on Ampicillin Resistance of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2023, 2023, 8079091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, T.A.; Lopez-Perez, M.; Haro-Moreno, J.M.; Almagro-Moreno, S. Allelic diversity uncovers protein domains contributing to the emergence of antimicrobial resistance. PLoS Genet 2023, 19, e1010490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Confer, A.W.; Ayalew, S. The OmpA family of proteins: roles in bacterial pathogenesis and immunity. Vet Microbiol 2013, 163, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirakawa, H.; Suzue, K.; Takita, A.; Kamitani, W.; Tomita, H. Roles of OmpX, an Outer Membrane Protein, on Virulence and Flagellar Expression in Uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun 2021, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, C.H.; Chang, C.L.; Huang, H.H.; Lin, Y.T.; Li, L.H.; Yang, T.C. Interplay between OmpA and RpoN Regulates Flagellar Synthesis in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Microorganisms 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, Y.; Wang, J.; Gao, H.; Wang, Z.; Dong, N.; Ma, Q.; Shan, A. Antimicrobial properties and membrane-active mechanism of a potential alpha-helical antimicrobial derived from cathelicidin PMAP-36. PLoS One 2014, 9, e86364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, A.W.; Kirby, W.M.; Sherris, J.C.; Turck, M. Antibiotic susceptibility testing by a standardized single disk method. Tech Bull Regist Med Technol 1966, 36, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, M.; Xie, X.; Dong, Y.; Du, H.; Wang, N.; Lu, C.; Liu, Y. Identification of novel virulence-related genes in Aeromonas hydrophila by screening transposon mutants in a Tetrahymena infection model. Vet Microbiol 2017, 199, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.H.; Siu, L.K.; Fung, C.P.; Lin, J.C.; Yeh, K.M.; Chen, T.L.; Tsai, Y.K.; Chang, F.Y. Contribution of outer membrane protein K36 to antimicrobial resistance and virulence in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Antimicrob Chemother 2010, 65, 986–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, B.J.; McCarter, L.L. Lateral flagellar gene system of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J Bacteriol 2003, 185, 4508–4518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Osei-Adjei, G.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, H.; Yang, W.; Zhou, D.; Huang, X.; Yang, H.; Zhang, Y. CalR is required for the expression of T6SS2 and the adhesion of Vibrio parahaemolyticus to HeLa cells. Arch Microbiol 2017, 199, 931–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro-Garcia, F.; Ruiz-Perez, F.; Cataldi, A.; Larzabal, M. Type VI Secretion System in Pathogenic Escherichia coli: Structure, Role in Virulence, and Acquisition. Front Microbiol 2019, 10, 1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, K.; Li, M.; Jiao, X. Characterization of the RpoN regulon reveals the regulation of motility, T6SS2 and metabolism in Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Front Microbiol 2022, 13, 1025960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadivelu, J.; Pang, M.-D.; Lin, X.-Q.; Hu, M.; Li, J.; Lu, C.-P.; Liu, Y.-J. Tetrahymena: An Alternative Model Host for Evaluating Virulence of Aeromonas Strains. PLoS ONE 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ly, T.M.; Muller, H.E. Ingested Listeria monocytogenes survive and multiply in protozoa. J Med Microbiol 1990, 33, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, B.L.; Leal, B.F.; Leyser, M.; de Barros, M.P.; Trentin, D.S.; Ferreira, C.A.S.; de Oliveira, S.D. Increased ompW and ompA expression and higher virulence of Acinetobacter baumannii persister cells. BMC Microbiol 2023, 23, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganie, H.A.; Choudhary, A.; Baranwal, S. Structure, regulation, and host interaction of outer membrane protein U (OmpU) of Vibrio species. Microb Pathog 2022, 162, 105267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haiko, J.; Westerlund-Wikstrom, B. The role of the bacterial flagellum in adhesion and virulence. Biology (Basel) 2013, 2, 1242–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strains | Genotype & Characteristics | Source |

|---|---|---|

| V.parahaemolyticus17802 | Cms, Kms, Ampr, Wild type strain, | ATCC |

| ∆Vp-porin | V.parahaemolyticus strain in-frame deletion in Vp-porin | This study |

| Escherichia coli | ||

| CC118 | λpir lysogen of CC118 (Δ(ara-leu) araD ΔlacX74galEgalKphoA20 thi-1rpsE rpoB argE (Am) recA1 | Our lab |

| CC118/pHelper | CC118 λpir harboring plasmid pHelper | Our lab |

| Plasmids | ||

| pSR47S | Bacterial allelic exchange vector with sacB, KanR | Our lab |

| pSR47S-∆Vp-porin | A 1689 bp fragment containing the upstream and downstream sequences of the ∆Vp-porin gene in pSR47S, KanR | This study |

| Primer Name | Primer Sequence (5’ to 3’) | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| UP-F | CGAGCTCCTTGATGGACTTCGCCAAC | Creation of ∆Vp-porin deletion fusion fragment |

| UP-R | CAACATTCGGTACTCAAGCAGCACTTGGTGCACGTTACTAC | |

| DOWN-F | GTAGTAACGTGCACCAAGTGCTGCTTGAGTACCGAATGTTG | |

| DOWN-R | GACTAGTGTACACACCGAATGCAGAC | |

| Vp-porin-T1 | GAACAACACTAGAACGCGC | Comfirmation of ∆Vp-porin deletion |

| Vp-porin-T2 | TCGGTTACCGAAGAGTCTTC | |

| Note: Restriction sites are italic. Complementary sites are underlined. | ||

| Primer name | Primer sequence (5' to 3') | Target |

|---|---|---|

| flgB-F | ACAAGGCACTAGGCATCC | polar flagellar cluster I genes |

| flgB-R | GACCATCTGTTCGGCTAAG | |

| flgC-F | GCGTCATGCTGTATTTGGTG | |

| flgC-R | AACCTGCACATTCGTTTGGT | |

| flgM-F | ATTCAAGTGCGACATCAAG | |

| flgM-R | CGGAGAAGCTGCCATATC | |

| flgK-F | GCCGTCAGTCAGTGATTC | |

| flgK-R | GTAGAGGACAGGTTGAGTTC | |

| fliE-F | CACTGTGCCCGTTTGCTTAC | polar flagellar cluster II genes |

| fliE-R | TCCGGCGGATGCTTCTATTC | |

| fliK-F | GTCGAGAAGAATGGCGAGAG | |

| fliK-R | CCAACTGAGCCTCTGACTCC | |

| flgA-F | TACCGACTGGCAAAGGTTGG | |

| flgA-R | TACCGACTGGCAAAGGTTGG | lateral flagellar cluster I genes |

| flgB-F | GCAGGTTCAGGCCCAGTATT | |

| flgB-R | TCATGTTGAGAAACGTCAGGCT | |

| flgG-F | AGATCTAGCGGTAATGGGGC | |

| flgG-R | GAGAAAGAGGTCGCGTTGTC | |

| lafA-F | GCTGGTGGCCTTATCGAAGA | |

| lafA-R | TACTGCGAAGTCTGCATCCAT | |

| motY-F | ATTAGTGAGGGTGCGCCTTT | |

| motY-R | GGTGAAGGGAAGGAATGGCA | |

| fliE-F | CGCTTGAGAAAACGACAGTGG | lateral flagellar cluster I genes |

| fliE-R | CCTACTAATGCGGTCTCGGC | |

| VPA1043-F | TCGAACAGCACGTAGAATCG | T6SS2 genes |

| VPA1043-R | GTGGCACTTCAGTTTCGTGA | |

| VPA1044-F | TCCTCAACCAAATCCTCGAC | |

| VPA1044-R | GCGTAGTTAGGCGTGTAGCC | |

| VPA1045-F | CCGATGCTCAATGGCTTAAT | |

| VPA1045-R | GCTGCTCTTTACCCAACTGC | |

| 16s rRNA-F | TTAAGTAGACCGCCTGGGGA | qPCR of 16s rRNA |

| 16s rRNA-R | GCAGCACCTGTCTCAGAGTT |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).