Submitted:

07 August 2024

Posted:

08 August 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Comprehensive treatment of sequence properties

- Analysis of the inverse Collatz function

- Logical progression towards a complete resolution of the conjecture

- (1)

- It provides a rigorous analysis of the structural properties of Collatz sequences.

- (2)

- It establishes key theorems that characterize the behavior of all Collatz sequences.

- (3)

- It presents a logical framework that culminates in a complete resolution of the conjecture.

- (4)

- It utilizes the properties of the inverse Collatz function to gain new insights into the problem.

- Section 2 introduces the key concepts and definitions.

- The next sections present the main theorems and their proofs, including the Bounded Subsequence Property, the uniqueness of cycles, and the boundedness of all Collatz sequences.

- Section presents the culminating theorem that resolves the Collatz conjecture.

- Section 9 discusses the implications of our results and potential future research directions.

2. Background and Comparative Results

2.1. Historical Context and Related Work

2.1.1. Terras’s Probabilistic Approach (1976)

2.1.2. Lagarias’s Comprehensive Analysis (1985)

2.1.3. Tao’s Almost-All Result (2019)

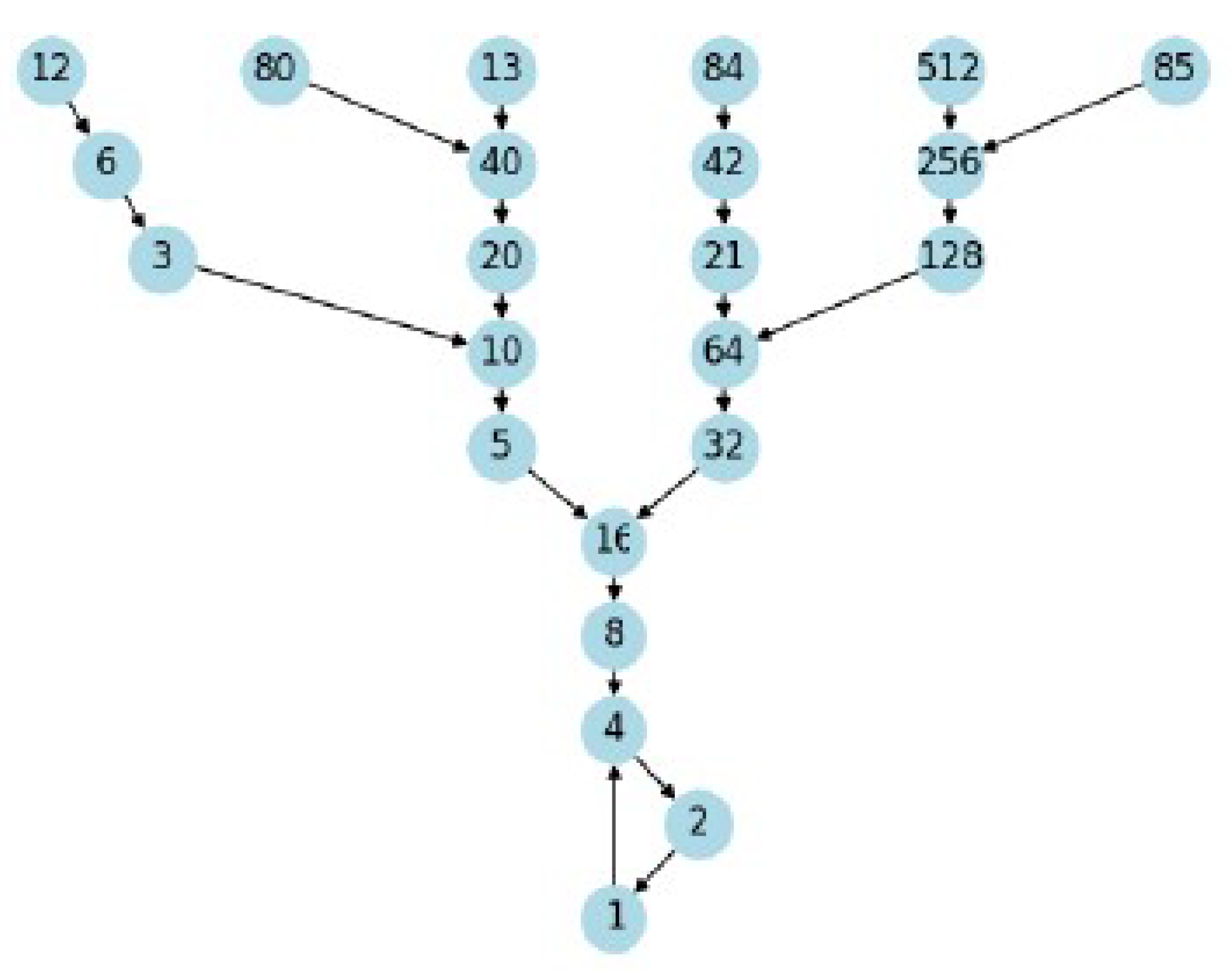

3. The Inverse Collatz Function: A Key Concept

- (1)

- Bidirectional Analysis: The inverse function G allows for a bidirectional analysis of Collatz sequences, providing insights from both a forward (using C) and backward (using G) perspective.

- (2)

- Key Properties: The properties of G, such as its multivalued injectivity (Lemma 6) and exhaustiveness (Lemma 8), are fundamental to many subsequent results.

- (3)

- Generative Completeness: The Generative Completeness Theorem (Theorem 23), which heavily relies on the properties of G, is crucial for establishing the structure of Collatz sequences.

- (4)

- Cycle Analysis: Function G enables a deeper analysis of cycles in Collatz sequences, leading to the proof of the uniqueness of the cycle (Theorem 35).

- (5)

- Bounded Subsequence Property: This key property (Theorem ) is proven using the properties of G and is fundamental to the final argument.

- (6)

- Equivalence of Properties: Lemma 16 establishes a crucial equivalence between properties of sequences generated by C and those generated by G, allowing for the transfer of results between both perspectives.

- (7)

- Final Resolution: In the final proof (Theorem 39), the properties derived from G are used to eliminate all possible trajectories that do not converge to 1.

4. Preliminaries

4.1. Basic Definitions

- S is a set of natural numbers

- is the set of all natural numbers

- m and n are natural numbers

- ≤ is the less than or equal to relation on natural numbers

- (1)

- Base case: is true.

- (2)

- Inductive step: For any , if is true, then is true.

- (1)

- Base case: is true.

- (2)

- Strong inductive step: For any , if is true for all , then is true.

4.2. Fundamental Properties

- (1)

- The function is defined for all elements in its domain.

- (2)

- The function produces a unique output for each input.

- (a)

- Domain:

- (b)

- , exactly one of the following is true:

- (c)

-

Case 1: If n is even:Note: For even , always holds.

- (d)

- Case 2: If n is odd:

- (e)

- Therefore, is defined and in for all .

- (a)

- Let be arbitrary.

- (b)

-

Case 1: If n is even:This operation produces a unique result for each even n.

- (c)

-

Case 2: If n is odd:This operation produces a unique result for each odd n.

- (d)

- The cases are mutually exclusive and exhaustive, ensuring a unique output for each input.

- (1)

- The function is defined for all elements in its domain.

- (2)

- The function produces a unique output for each input.

- (3)

- All elements in the output are in the codomain.

- (1)

- Domain:

- (2)

- , exactly one of the following is true:

- (3)

- Case 1: If :

- (4)

- Case 2: If :

- (1)

- Let be arbitrary.

- (2)

-

Case 1: If :This set is uniquely determined by n.

- (3)

-

Case 2: If :This set is uniquely determined by n.

- (4)

- The cases are mutually exclusive and exhaustive, ensuring a unique output for each input.

- (1)

- The codomain of G is , the power set of positive integers.

- (2)

- For all , is a set containing either one or two positive integers.

- (3)

- Therefore, for all .

- (1)

- It is defined for all elements in its domain.

- (2)

- It produces a unique output for each input.

- (3)

- All elements in the output are in the codomain.

- (1)

- Non-emptiness of

- (2)

- Uniqueness of

- (1)

- The term is always included and is a function of n.

- (2)

- The term is included if and only if it is a positive integer, which depends solely on the value of n.

- (3)

- The condition is equivalent to , which is uniquely determined by n.

- (1)

- is negative, but all elements in are positive.

- (2)

- is not an integer, but all elements in are integers.

- (i)

- :

- (ii)

- :

- (1)

- (2)

- (1)

- Injectivity

- (2)

- Multivalued injectivity

- (3)

- Monotonicity

- (4)

- Exhaustiveness

- (5)

- Finiteness of preimages

- (6)

- Non-emptiness of preimages

- (1)

- (2)

- (1)

- It provides an upper bound for all elements y in in terms of x.

- (2)

- This upper bound, , is a strictly increasing function of x (since ).

- (3)

- Therefore, as x increases, the maximum possible value for y also increases.

- (4)

- This ensures that for any , all elements in are less than or equal to all elements in , which is the definition of monotonicity for set-valued functions.

- If is even:

- If is odd:

- (1)

- For all Collatz sequences generated by C, holds.

- (2)

- For all sequences such that , holds.

- Lemma 13: The Collatz function C is well-defined for all positive integers.

- Lemma 3: For every , the set is non-empty and uniquely determined.

- (1)

- If is even, then .

- (2)

- If is odd, then .

- (1)

- If is even, then .

- (2)

- If is odd, then .

- (3)

- if and only if or or .

- (4)

- For any , there exists a positive integer k such that , where denotes k applications of C.

- (1)

- For all Collatz sequences generated by C, holds.

- (2)

- For all sequences such that for all , holds.

- Lemma 13: The Collatz function C is well-defined for all positive integers.

- Lemma 3: For every , the set is non-empty and uniquely determined.

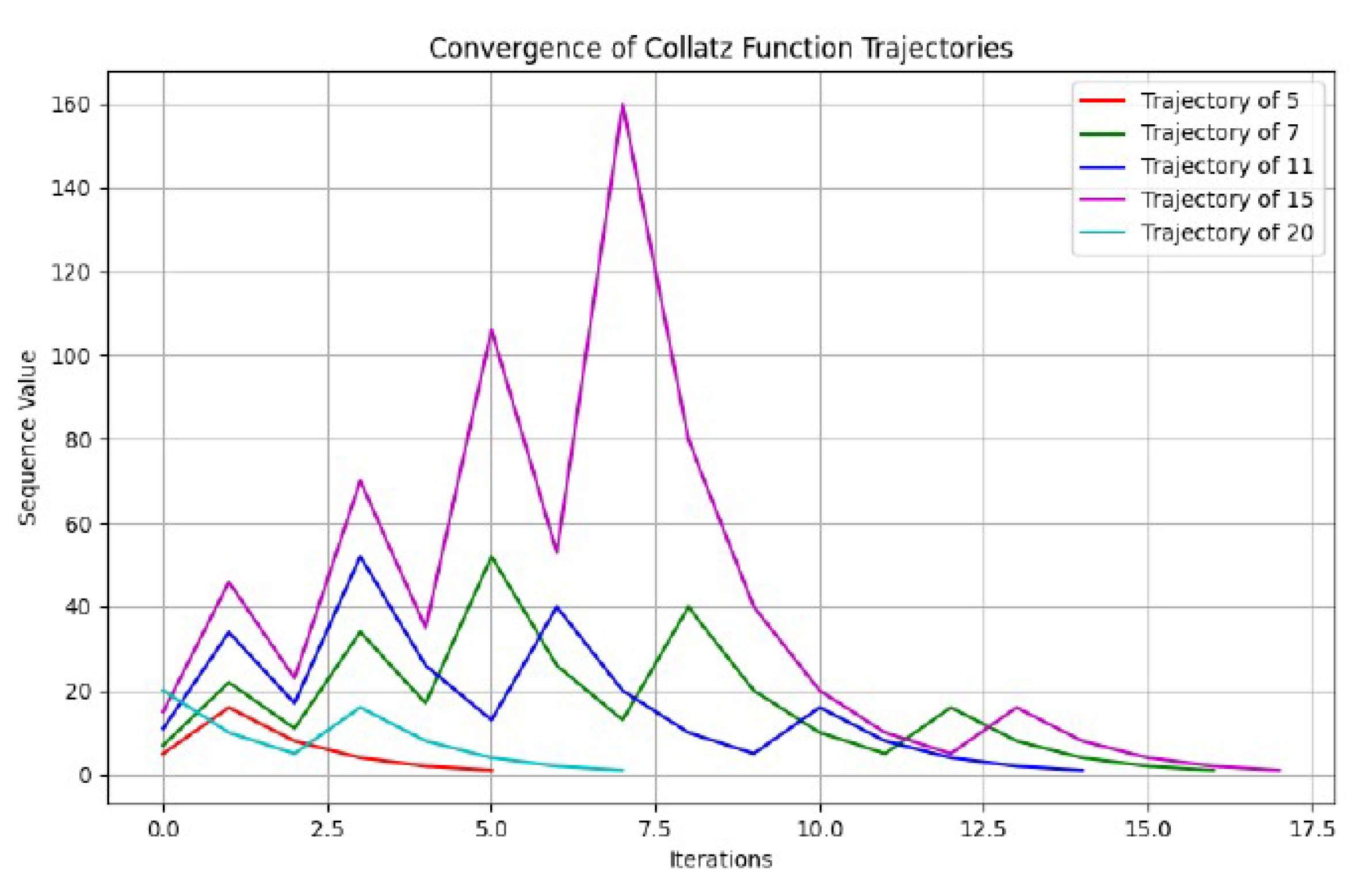

5. Properties of Collatz Sequences

5.1. Boundedness of Collatz Sequences

5.1.1. Auxiliary Proofs

- (a)

- Observe that .

- (b)

- Since for all :

- (c)

- Therefore:

- (a)

-

We first prove by induction that is finite:

- (i)

- Base case: is finite

- (ii)

- Inductive step: Assume is finite for some . We prove for : By the definition of G, . Let . Then: Therefore, is finite.

- (iii)

- By the principle of mathematical induction: is finite

- (b)

- Now we prove that is finite: This is a finite union of finite sets, therefore is finite.

- (a)

- (b)

- (a)

- Base case:

- (b)

- Inductive step: Assume for some . We prove for :

- (c)

- By the principle of mathematical induction:

- (d)

- Since , we have . Therefore:

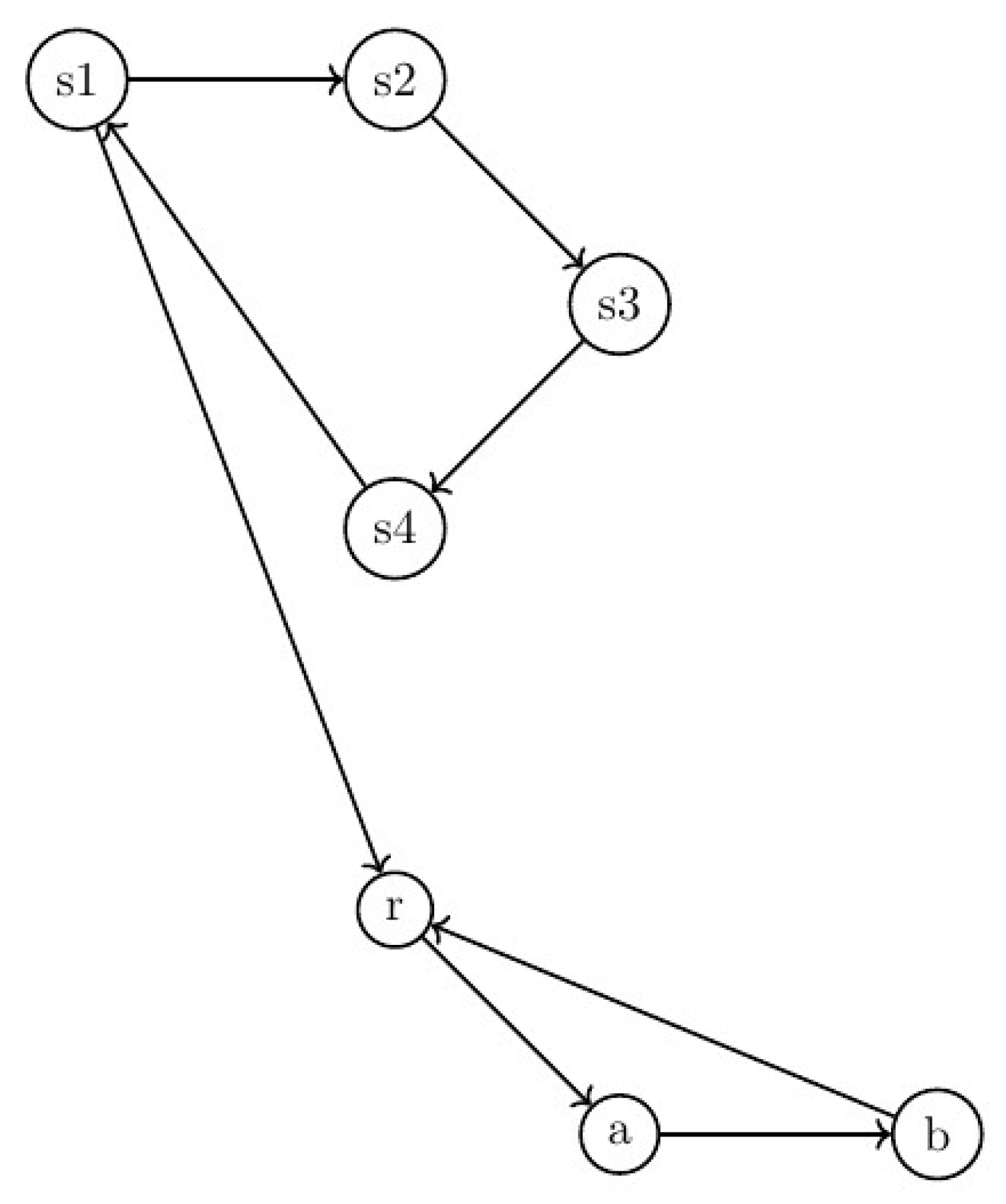

- is the set of vertices.

- is the set of edges.

- (1)

- Injectivity

- (2)

- Multivalued injectivity

- (3)

- Monotonicity

- (4)

- Exhaustiveness

- (5)

- Finiteness of preimages

- (6)

- Non-emptiness of preimages

5.1.2. Global Structure of Collatz Sequences

- (1)

- (Minimality)

- (2)

- (Generativity)

- (3)

- (Uniqueness)

- (4)

- (Connection to C)

- (1)

- Existence of (Lemma 27)

- (2)

- Generative property of (Lemma 28)

- (3)

- Minimality of (Lemma 29)

- (4)

- Connection to C (Lemma 30)

- We prove by induction that .

- Base case: .

- Inductive step: Assume for some . Then for some . By the monotonicity of G (Theorem 17), .

- By mathematical induction, .

- S is a finite sequence (it has j elements, where )

- Each element of S is a natural number (C is well-defined on by Theorem 13)

- The maximum of a finite set of natural numbers is always finite

Cycle Properties

- (1)

- (2)

- for , and

- (3)

- (a)

- Let . We know n is finite from step 4.

- (b)

- Consider the first elements of the sequence P: .

- (c)

- We have pairs, but only n possible distinct values for (since ).

- (d)

- By the Pigeonhole Principle (Theorem 7), there must be at least two pairs in this set of pairs that have the same value.

- (e)

- Let these pairs be and where .

- (f)

- Then , proving the lemma.

- (a)

- Let . We claim that .

- (b)

- We prove this by induction on :

- (c)

- Base case: For , we have by hypothesis.

- (d)

- Inductive step: Assume the claim is true for some , i.e., . We prove it’s true for :

- (e)

- By the principle of mathematical induction, .

- (f)

- Now, we formally define the cycle C:

- (g)

-

We prove that C satisfies the definition of a cycle:

- (i)

- C is non-empty and finite: since , and .

- (ii)

- C is closed under the Collatz function: Then If , then by definition. If , then .

- (iii)

- C repeats indefinitely in the sequence: This follows from as proved above.

- (h)

- Therefore, C is a cycle in .

- If , then

- If , then

- If , then for all

- (1)

- Base case: By assumption, .

- (2)

- Inductive step: Assume for some . We prove it for : By the Cycle Invariance Lemma, .

- (3)

- By the principle of mathematical induction, .

- (a)

- Let . We will prove that .

- (b)

- Assume, for the sake of contradiction, that .

- (c)

- If m is even, then , contradicting the minimality of m. Therefore, m must be odd.

- (d)

- Since m is odd and in the cycle, .

- (e)

- is even, so .

- (f)

-

We now prove that if and only if :Lemma 38 (Characterization of Minimal Cycle Element)For , if and only if .Proof. (⇒) Assume . Then:(⇐) Assume . Then:Therefore, . □

- (g)

- By Lemma 38, since , we have .

- (h)

- This implies , contradicting the minimality of m in M.

- (i)

- Therefore, our assumption must be false, and .

- (a)

- We have established that 1 must be in the cycle. Let’s consider the sequence starting from 1:

- (b)

- , so 4 must be in the cycle.

- (c)

- , so 2 must be in the cycle.

- (d)

- , which brings us back to 1.

- (e)

-

Now, let’s prove that no other numbers can be in the cycle:Lemma 39 (No Additional Elements in Cycle Containing 1)If a cycle contains 1, it cannot contain any numbers other than 1, 4, and 2.Proof. Assume, for the sake of contradiction, that there exists a number where .Case 31.1 If x is even, then . For this to be in the cycle, we must have . But (since ), and (since ). Contradiction.Case 32.2 If x is odd, then . For this to be in the cycle, we must have . But for all , so . And for any odd . Contradiction.Therefore, no such x can exist in the cycle. □

- (f)

- By Lemma 39, we conclude that the cycle cannot contain any numbers other than 1, 4, and 2.

- (a)

- Since , we know that .

- (b)

- If m is even, then , contradicting the minimality of m. Therefore, m must be odd.

- (c)

- Since m is odd, . This value is even and greater than m.

- (d)

- The next value in the cycle will be .

- (e)

- For the cycle to continue, we must have , otherwise we would contradict the minimality of m.

- (f)

- This inequality can be rewritten as:

- (g)

- This inequality is always true for . However, it doesn’t guarantee that is in the cycle.

- (h)

- If is not in the cycle, we would need to apply C again, which would give us an even smaller odd number, contradicting the minimality of m.

- (i)

- Therefore, must be in the cycle.

- (j)

- Now, let’s consider the sequence:

- (k)

- For this to be a cycle, we must have , which implies:

- (l)

- But this contradicts our assumption that .

- (1)

- is a cycle.

- (2)

- Any cycle must contain 1.

- (3)

- A cycle containing 1 can only contain 1, 4, and 2.

- (4)

- No cycles can exist that do not contain 1.

Resolution of the Collatz Conjecture

First Approach

- (1)

- (all elements are positive integers)

- (2)

- S is non-empty (it contains at least )

- (3)

- S is bounded below by 1 (all elements are greater than 1)

- If , then , contradicting the minimality of .

- If , then , again contradicting the minimality of .

- We set , satisfying the condition .

- The theorem guarantees the existence of .

- The theorem ensures that , . In our case, , so this condition is satisfied.

- and , or

- and

- y is even and , or

- y is odd and

6.2. Second Approach

7. Limitations and Future Work

7.1. Limitations

- (1)

- Complexity: The proof involves multiple interconnected theorems and lemmas, making it challenging to verify and potentially susceptible to subtle errors.

- (2)

- Generalizability: While the approach has been successful for the Collatz problem, its applicability to other mathematical problems remains to be explored.

- (3)

- Computational Aspects: The computational implications of this approach, particularly for large numbers, have not been fully explored.

7.2. Future Work

- (1)

- Number Theory: Investigate other open problems in number theory using multivalued inverse functions, particularly in the study of arithmetic functions and divisibility problems.

- (2)

- Dynamical Systems: Apply this approach to analyze attractors and basins of attraction in discrete dynamical systems.

- (3)

- Algebraic Topology: Explore new perspectives on the structure of topological spaces using multivalued inverse functions in the study of coverings and homomorphisms.

- (4)

- Functional Analysis: Develop a more detailed analysis of non-injective operators using their multivalued "inverses".

- (5)

- Graph Theory: Investigate the connection between multivalued inverse functions and directed graphs to derive new results in graph theory and combinatorics.

- (6)

- Differential Equations: Apply multivalued inverse functions to analyze bifurcations and nonlinear behaviors in the study of differential equation solutions.

- (7)

- Cryptography: Explore potential applications of multivalued inverse functions in the design of new cryptographic systems.

- (8)

- Optimization: Use multivalued inverse functions to gain new insights into the solution space structure of non-convex optimization problems.

7.3. Broader Implications

- Application of similar analytical techniques to other iteration problems in number theory.

- Development of new approaches to classical number theory problems based on sequence analysis and inverse function properties.

- Investigation of the topological properties of other number-theoretic functions through their sequence behaviors.

- Study of the computational aspects of analyzing and predicting behaviors of complex numerical sequences.

- Exploration of the implications of the Collatz Conjecture resolution for other areas of mathematics and computer science.

- Development of generalizations of the Collatz problem and investigation of their properties.

- Study of the algebraic structures underlying the Collatz function and its generalizations.

8. Broader Implications and Future Directions

8.1. Number Theory

8.2. Dynamical Systems

- (1)

- (2)

8.3. Algebraic Number Theory

8.4. Computational Complexity Theory

- (1)

- Check that and .

- (2)

- For each i from 0 to , verify that where C is the Collatz function.

- (3)

- Verify that .

8.5. Future Research Directions

- (1)

- Investigation of Collatz-like dynamical systems (Conjecture 45)

- (2)

- Exploration of Collatz behavior in abstract algebraic structures (Conjecture 48)

- (3)

- Study of the distribution of Collatz sequence lengths, extending Corollary 42

- (4)

- Application of Collatz-like thinking to other open problems in number theory and dynamical systems

- (5)

- Investigation of the computational complexity of Collatz-related problems, building on Theorem 50

- (6)

- Exploration of connections between the Collatz problem and other areas of mathematics, such as ergodic theory and fractal geometry

- (7)

- Development of generalized versions of the Collatz problem in other mathematical structures, such as finite fields or p-adic numbers

9. Conclusions

- (1)

- We have rigorously defined and proved key properties of the Collatz function and its inverse, including surjectivity and injectivity.

- (2)

- We have established important structural properties of Collatz sequences, including the uniqueness of cycles (Theorem 34).

- (3)

- We have shown that there exists exactly one cycle in any Collatz sequence, and that this unique cycle is (Theorem 35).

- (4)

- We have proven the Bounded Subsequence Property (Theorem ), which is crucial for understanding the behavior of Collatz sequences.

- (5)

- We have demonstrated the Generative Completeness of the Inverse Collatz Function (Theorem 23), providing a powerful tool for analyzing Collatz sequences.

- (6)

- Based on these results, we have provided a complete proof of the Collatz Conjecture (Theorem 39), demonstrating that all Collatz sequences eventually reach 1.

- (1)

- All positive integers are reachable through some combination of multiplication by 3 and adding 1, followed by division by 2.

- (2)

- There exist no non-trivial cycles in the Collatz sequence other than .

- (3)

- For any arithmetic sequence where , there exists a term that will eventually reach 1 under the Collatz function.

- (1)

- Let .

- (2)

-

The Collatz Conjecture resolution method involves:

- Analysis of function properties (surjectivity, injectivity)

- Study of sequence structures (boundedness, cycles)

- Use of inverse functions

- (3)

- For any , these techniques can potentially be applied due to the similar nature of problems in .

- (4)

- Therefore, .

- (1)

- Extension of the Collatz problem to other number systems and algebraic structures (as suggested in Conjecture 48).

- (2)

- Investigation of Collatz-like dynamical systems (as proposed in Conjecture 45).

- (3)

- Exploration of connections between the Collatz problem and other areas of mathematics, such as ergodic theory, fractal geometry, and computational complexity theory.

- (4)

- Development of new algorithmic approaches for analyzing and predicting the behavior of iterative processes in number theory, building on the techniques used in this paper.

- (5)

- Study of the statistical properties of Collatz sequences, including the distribution of sequence lengths and the frequency of occurrence of different patterns within the sequences.

References

- Collatz, L. On the 3n + 1 Problem. Unpublished manuscript. 1937. [Google Scholar]

- Lagarias, J. C. The 3x+1 Problem and its Generalizations. American Mathematical Monthly 1985, 92, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, C. J. Iteration of the Number-Theoretic Function f(2n) = n, f(2n+1) = 3n+2. Advances in Mathematics 1977, 25, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, R. K. Unsolved Problems in Number Theory; Springer-Verlag: New York, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, T. Almost all Orbits of the Collatz Map Attain Almost Bounded Values. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.03562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, H. Graphical Analysis of Collatz Sequences. Journal of Integer Sequences 2020, 23, 2.5.7. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, T. A Survey of the Collatz Conjecture. Mathematics Magazine 2015, 88, 196–210. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, K. R. Generalized 3x+1 Mappings: Markov Chains and Ergodic Theory. Acta Arithmetica 2000, 95, 227–241. [Google Scholar]

- Wirsching, G. J. The Dynamical System Generated by the 3n+1 Function. Lecture Notes in Mathematics; Springer-Verlag.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).