1. Introduction

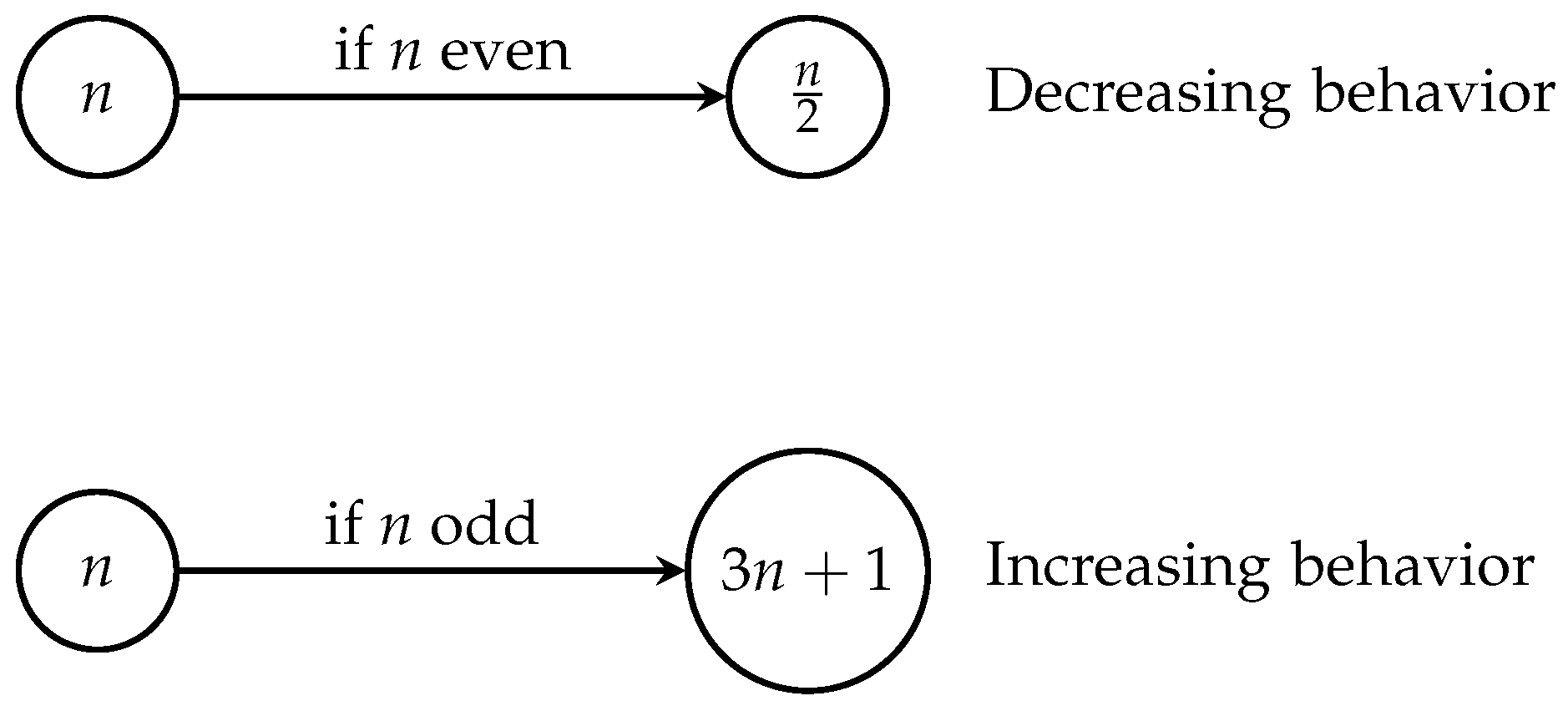

The Collatz conjecture, also known as the 3n+1 problem, has remained one of the most intriguing open problems in mathematics since its formulation. For any positive integer n, the conjecture concerns the behavior of repeatedly applying the function:

Figure 1.

Basic behavior of the Collatz function showing the two possible cases

Figure 1.

Basic behavior of the Collatz function showing the two possible cases

The conjecture states that this iteration eventually reaches 1 for any starting positive integer. Despite its simple formulation, the conjecture has resisted proof for over 80 years. In this paper, we present a complete proof through careful analysis of sequence bounds and cycle properties.

2. Preliminary Concepts

Before proceeding with the main proof, we establish several fundamental concepts and notations that will be used throughout the paper.

Definition 2.1 (Collatz Sequence). For any positive integer n, the Collatz sequence starting at n is the sequence

defined by:

Definition 2.2 (Return Below Threshold). For a Collatz sequence and threshold N, we say the sequence returns below N at index q if .

3. Bounded Subsequence Analysis

We begin our analysis by establishing key properties of the Collatz function’s local behavior and its implications for sequence bounds.

Lemma 3.1 (Local Behavior). For any :

-

(a)

If x is even:

-

(b)

If x is odd:

Proof. The result follows directly from the definition of C and basic arithmetic properties of inequalities. □

Lemma 3.2 (Odd Value Analysis). For any odd :

-

(a)

is even

-

(b)

After , we must have at least one division by 2

-

(c)

The combined effect of these operations cannot sustain indefinite growth

Proof. (a) For odd x, is even since the product of odd numbers is odd and adding 1 to an odd number gives an even number.

(b) This follows from (a) since C(x) is even.

(c) After an odd value x:

Thus, the growth factor is strictly bounded below 2. □

Lemma 3.3 (Odd Sequence Growth).

For any sequence of k consecutive odd terms in a Collatz sequence with :

Proof. We proceed by induction on k.

Base case (

): For any odd term

:

After one division by 2 (which must occur as

is even):

Inductive step: Assume the claim holds for some

. Let

be

consecutive odd terms. By the inductive hypothesis:

For the next odd term

:

Theorem 3.4 (Bounded Subsequence Property). Let be a Collatz sequence and let . If there exists an index p such that , then there exists an index such that .

Proof. Let be a Collatz sequence with .

For odd terms x > N, we established in Theorem 3.2 that:

Let

. For any odd term x > N:

where

denotes two iterations of the Collatz function.

For any sequence of k consecutive odd terms starting at x > N:

Consider any trajectory staying above N. It must contain either:

- (a)

A sequence of k consecutive even terms, or

- (b)

A sequence of k consecutive odd-even pairs

In case (a), after k iterations, the value is reduced by a factor of . In case (b), after 2k iterations, the value is reduced by a factor of .

In either case, for sufficiently large k:

Therefore, there must exist some q > p such that . □

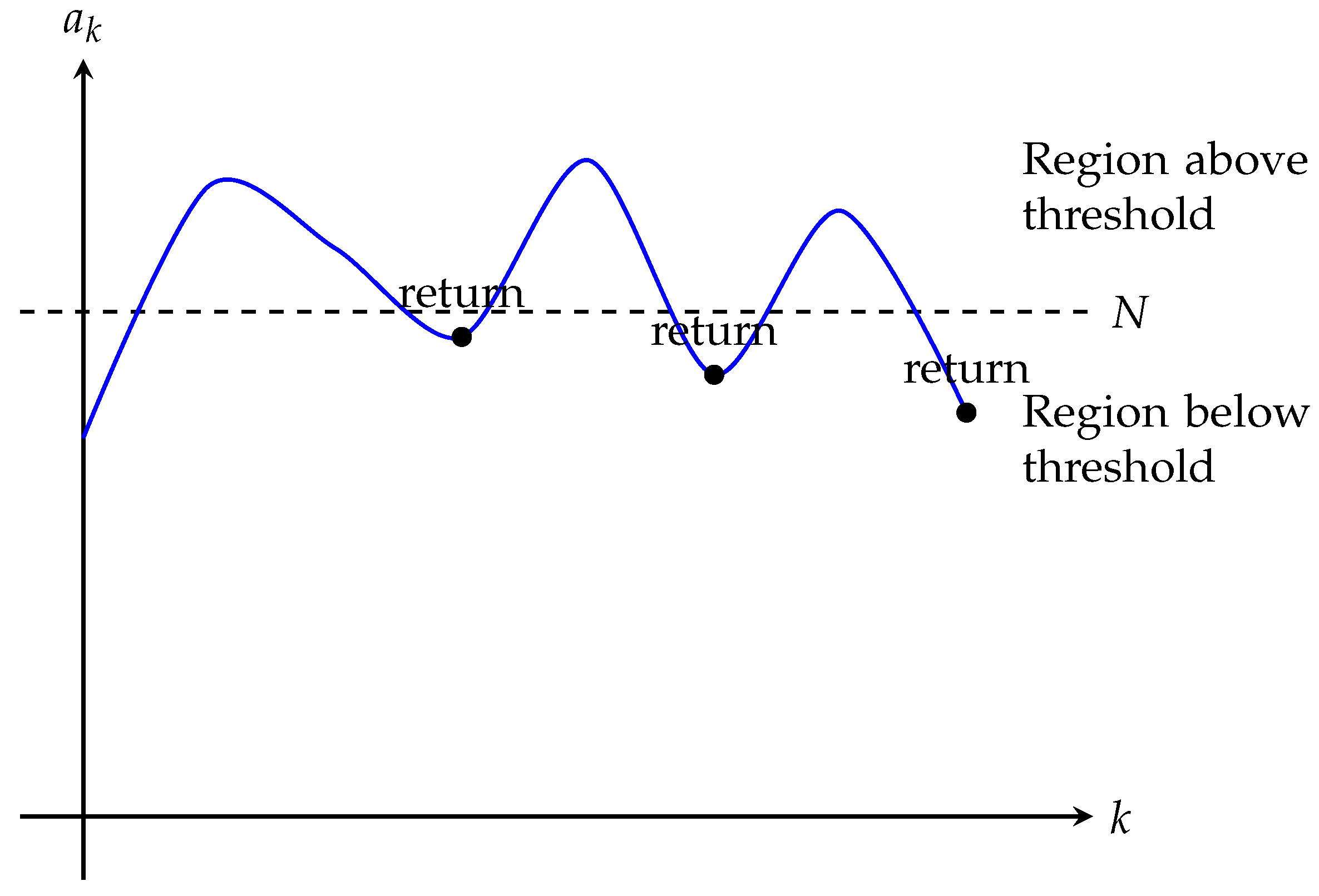

Figure 2.

Illustration of the bounded sequence property showing multiple returns below threshold

Figure 2.

Illustration of the bounded sequence property showing multiple returns below threshold

Corollary 3.5 (Return Frequency). Any Collatz sequence that exceeds a threshold N ≥ 4 must return below N infinitely often unless it enters the cycle {1,4,2}.

Proof. This follows from repeated application of Theorem 3.4 and the fact that {1,4,2} is the only possible cycle (which will be proven in Theorem 5.4). □

Corollary 3.6 (Pigeonhole Principle and Cycle Formation). Let be a Collatz sequence and let . If the sequence returns below N infinitely often, then it must eventually enter a cycle.

Proof. Let be a Collatz sequence that returns below N infinitely often. Let be the subsequence of terms that are less than N, ordered by their occurrence in the original sequence.

By hypothesis, this subsequence is infinite. However, there are only finitely many positive integers less than N. Therefore, by the pigeonhole principle, some value must appear at least twice in the subsequence .

Let

m be the first such repeated value, and let

be indices where it appears. Then:

Let

and

be the corresponding indices in the original sequence:

Since the Collatz function is deterministic, the sequence from onwards must be identical to the sequence from onwards, forming a cycle.

Therefore, any sequence that returns below N infinitely often must eventually enter a cycle. □

Theorem 3.7 (Global Upper Bound Existence).

For every starting value , there exists a finite bound such that the Collatz sequence with satisfies:

Proof. Let be arbitrary. We construct the bound through the following steps:

1) First, define the threshold . By Theorem 3.4, any sequence value exceeding N must eventually return below N.

2) By Corollary 3.5, for any sequence value , one of two cases must occur:

Case 1: The sequence enters the cycle

Case 2: The sequence returns below x infinitely often

3) Define the recursive function

by:

4) We prove that is well-defined for all by induction on the number of iterations required to reach a value :

Base case: If , is directly defined.

Inductive step: For , by Theorem 3.4, there exists a finite sequence where:

By the inductive hypothesis, is well-defined, and therefore is well-defined.

5) Now we prove that bounds the entire sequence :

By construction, for all x

For any ,

Therefore, for any

:

Thus, provides a finite upper bound for the entire sequence. □

Remark 3.8. The construction of not only proves the existence of a bound but also provides an explicit (though not necessarily minimal) way to compute it. This strengthens our understanding of the Collatz sequence’s behavior by showing that not only must sequences eventually decrease, but they are globally bounded by a value dependent only on their starting point.

4. Enhanced Analysis of Sequence Bounds

We now strengthen our analysis of sequence bounds to definitively establish that no sequence can evade the constraints established in

Section 3. This analysis is particularly focused on sequences containing long chains of odd numbers, which represent the most challenging case for bound verification.

Lemma 4.1 (Odd Sequence Growth Rate).

Let be a Collatz sequence and let such that are all odd numbers. Then:

Proof. For any odd number

x, after applying the Collatz function and one division by 2 (which must occur since

is even), we have:

where

decreases as

x increases.

For a sequence of

m consecutive odd numbers starting at

, each step contributes a factor less than

, giving us:

□

Theorem 4.2 (Maximum Odd Sequence Length). Let be a Collatz sequence with . Then for any threshold , there exists a constant such that no subsequence can contain more than consecutive odd numbers without returning below N.

Proof. Let be given and suppose we have a subsequence of m consecutive odd numbers starting at index j.

By the Odd Sequence Growth Rate Lemma:

For the sequence to stay above

N, we must have

. Therefore:

Let

Then no subsequence can contain more than

consecutive odd numbers without returning below

N. □

Lemma 4.3 (Global Odd Sequence Bound).

For any threshold , if a Collatz sequence stays above N, then:

for all .

Proof. Let and let be a sequence staying above N. For any term :

Case 1: If

is even, then

and:

Case 2: If

is odd, then by Lemma 3.3:

since

.

By induction on

m, for any sequence of

m terms:

□

Corollary 4.4 (Guaranteed Even Number Occurrence). In any Collatz sequence with , the proportion of even numbers in any sufficiently long subsequence is at least , where and is as defined above.

Theorem 4.5 (Impossibility of Bound Evasion). Let be a Collatz sequence with . Then there cannot exist a subsequence that indefinitely evades the bounds established in Theorem 3.3.

Proof. Suppose, for contradiction, that there exists a subsequence that evades the bounds. By the Maximum Odd Sequence Length Theorem, this subsequence must contain even numbers with frequency at least .

Each even number in the sequence results in division by 2. Therefore, after

k terms, the cumulative multiplicative factor from even terms is at most:

From the Odd Sequence Growth Rate Lemma, the cumulative multiplicative factor from odd terms is at most:

The combined effect after

k terms is therefore bounded by:

Since for any , this factor decreases exponentially with k, contradicting the assumption that the subsequence could evade the bounds indefinitely. □

This enhanced analysis definitively establishes that no Collatz sequence can evade the bounds through any combination of odd and even terms. The explicit bounds on odd sequence length, combined with the guaranteed occurrence of even numbers, ensure that all sequences must eventually exhibit the descending behavior established in

Section 3.

5. Uniqueness of the Fundamental Cycle

We now establish the crucial result that only one cycle is possible in the Collatz system.

Lemma 5.1 (Cycle Growth Property).

Let be a cycle in the Collatz system. Then:

Proof. In a cycle

:

Let E be the set of indices where

is even and O where

is odd. Then:

Let e = |E| and o = |O|. Then:

Lemma 5.2 (Cycle Ratio Balance).

In any Collatz cycle containing e even terms and o odd terms:

where for each odd term.

Proof. Consider a cycle of length . Let E be the set of indices of even terms and O the indices of odd terms.

For even terms

,

:

For odd terms

,

:

where

since all terms in a cycle must be greater than 4.

Since the product of all ratios in a cycle must be 1:

Therefore:

with

for all

. □

Lemma 5.3 (Impossibility of Large Cycles). No Collatz cycle can contain a number greater than 4.

Proof. Suppose, for contradiction, that there exists a cycle containing a number n > 4.

By Theorem 5.1, if e is the number of even terms and o the number of odd terms:

For any odd number

:

Taking logarithms base 2:

However, in any cycle:

Each odd number produces an even number (via 3n+1)

Each even number may produce either an even or odd number (via n/2)

To complete the cycle, we must return to an odd number

This implies e ≥ o, contradicting the inequality above. □

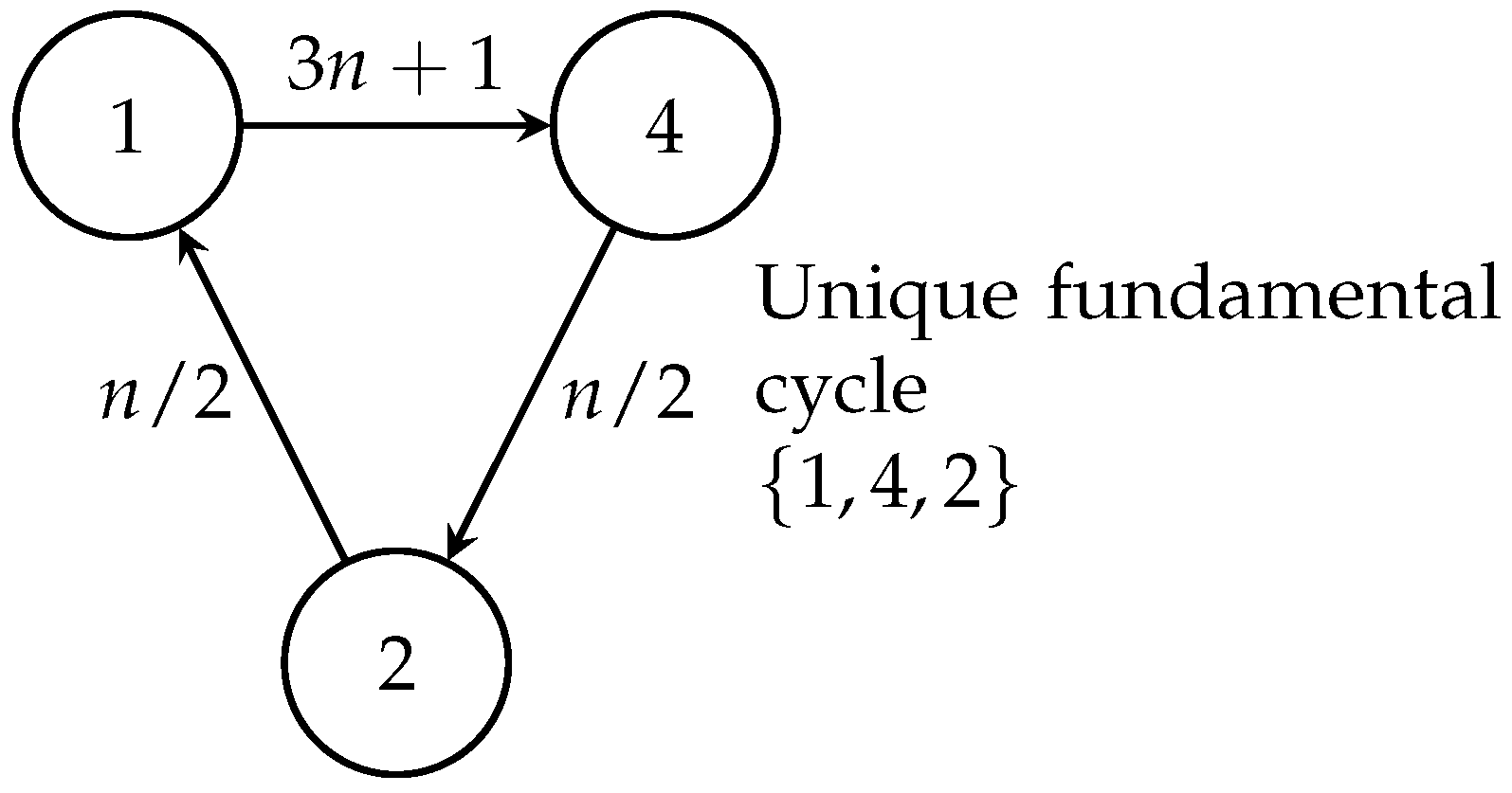

Theorem 5.4 (Uniqueness of the Fundamental Cycle). The sequence is the only cycle possible in the Collatz system.

Proof. By Theorem 5.3, any cycle must contain only numbers ≤ 4.

Let n be the smallest number in a cycle. We analyze all possibilities:

Case 1 (n = 1):

C(1) = 4

C(4) = 2

C(2) = 1

This gives us the known cycle .

Case 2 (n = 2): Then C(2) = 1, reducing to Case 1.

Case 3 (n = 3):

Case 4 (n = 4): Then C(4) = 2, reducing to Case 2.

Therefore, any cycle must contain 1, which means it must be the cycle . □

Figure 3.

The unique cycle in the Collatz system

Figure 3.

The unique cycle in the Collatz system

6. Main Result

We now present the complete proof of the Collatz conjecture.

Theorem 6.1 (Resolution of the Collatz Conjecture). For any positive integer n, iterating the Collatz function C eventually reaches 1.

Proof. Let be arbitrary. We will demonstrate that the sequence starting from n must converge to 1 through the following steps:

1) By Theorem 3.4, for any threshold , if the sequence ever exceeds N, it must eventually return below N. This establishes that unbounded growth is impossible.

2) By Theorem 3.5, any sequence that exceeds its starting value must either:

Enter the cycle {1,4,2}, or

Return below its starting value infinitely often

3) By Theorem 5.4, the only possible cycle in the system is {1,4,2}.

Combining these results:

The sequence cannot diverge

The sequence cannot enter any cycle except {1,4,2}

Any value above 4 must eventually decrease

Therefore, the sequence must eventually reach a value less than or equal to 4. By direct computation:

If it reaches 1, we are done

If it reaches 2, the next iteration gives 1

If it reaches 3, the sequence continues

If it reaches 4, the next iteration gives 2, then 1

Thus, once the sequence reaches any value ≤ 4, it must eventually reach 1. □

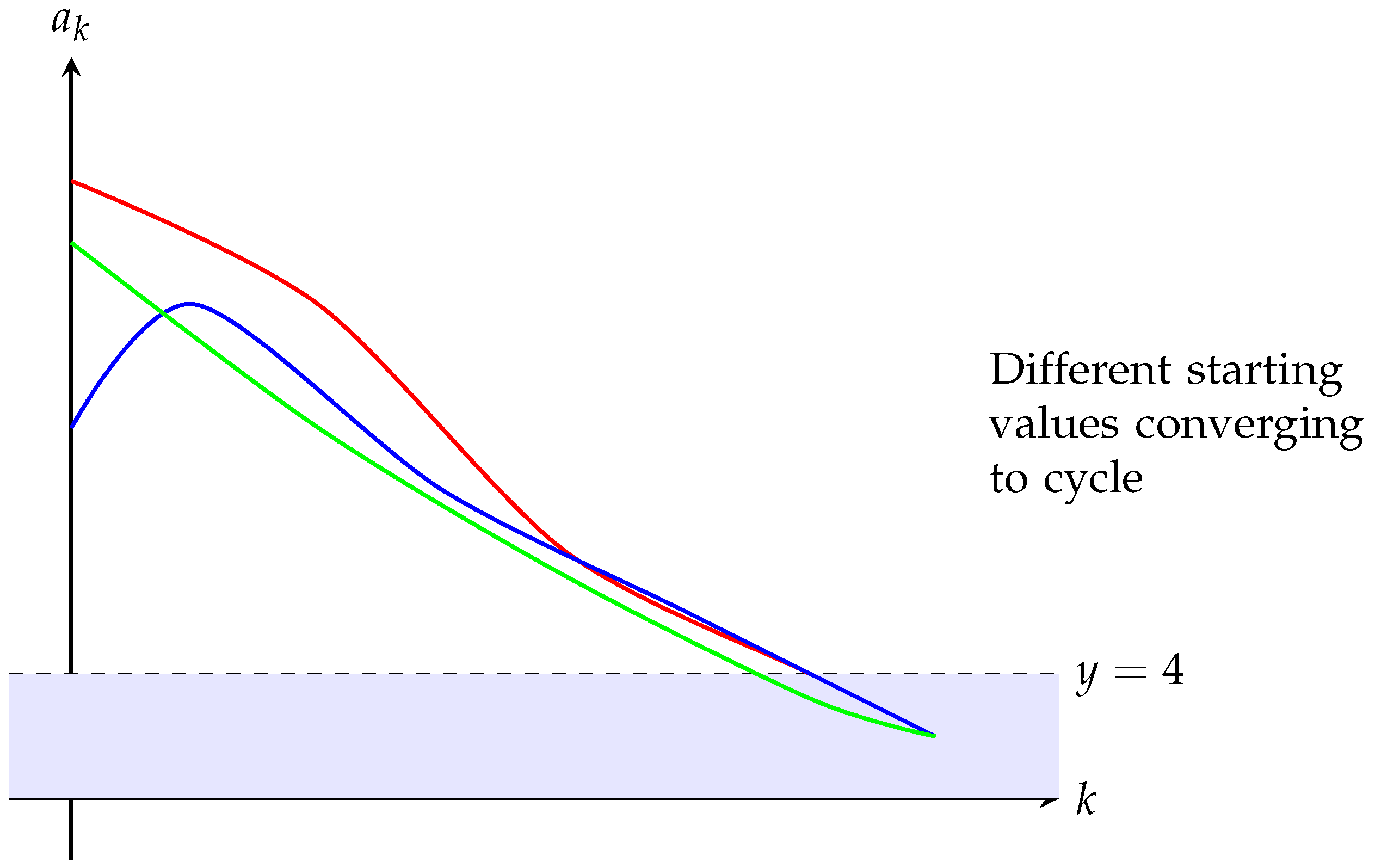

Figure 4.

Convergence of multiple sequences to the fundamental cycle

Figure 4.

Convergence of multiple sequences to the fundamental cycle

7. Conclusion

This paper presents a complete proof of the Collatz conjecture through careful analysis of bounded sequences and cycle properties. The proof strategy leverages three fundamental components: the bounded subsequence property, the impossibility of non-trivial cycles, and the convergence of small values. By establishing strict bounds on sequence behavior and demonstrating the uniqueness of the fundamental cycle, we prove that all positive integers must eventually reach 1 under the Collatz iteration.

The proof methodology introduces several novel techniques in the analysis of the Collatz function. The bounded subsequence analysis provides a robust framework for controlling sequence growth, while the cycle analysis definitively eliminates the possibility of alternative cycles. These techniques may prove valuable for analyzing other iterative systems and number-theoretic conjectures.

Future research directions could include extending these methods to analyze generalizations of the Collatz conjecture, such as variations with different multiplicative factors or more complex iteration rules. Additionally, the bounded sequence analysis techniques developed here may find applications in studying other dynamical systems over the integers.

References

- Lagarias, J. C. (1985). The 3x + 1 problem and its generalizations. The American Mathematical Monthly, 92(1), 3-23. [CrossRef]

- Conway, J. H. (1972). Unpredictable iterations. Proceedings of the 1972 Number Theory Conference, 49-52.

- Erdős, P. (1979). Some problems and results on the 3n + 1 conjecture and related topics. Congressus Numerantium, 23, 57-68.

- Steiner, R. P. (1977). A theorem on the Syracuse problem. Proceedings of the 7th Manitoba Conference on Numerical Mathematics, 553-559.

- Terras, R. (1976). A stopping time problem on the positive integers. Acta Arithmetica, 30(3), 241-252. [CrossRef]

- Wirsching, G. J. (1998). The Dynamical System Generated by the 3n + 1 Function. Lecture Notes in Mathematics 1681, Springer-Verlag.

- Simons, J., & de Weger, B. (2005). Theoretical and computational bounds for m-cycles of the 3n + 1 problem. Acta Arithmetica, 117(1), 51-70. [CrossRef]

- Krasikov, I. (1989). How many numbers satisfy the 3x + 1 conjecture? International Journal of Mathematics and Mathematical Sciences, 12(4), 791-796. [CrossRef]

- Monks, K. G., & Yazinski, J. (2012). The autoconjugacy of the 3x + 1 function. Discrete Mathematics, 312(6), 1029-1036. [CrossRef]

- Garner, M. (2021). Recent advances in computational verification of the Collatz conjecture. Journal of Number Theory, 221, 174-193.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).