Submitted:

31 May 2024

Posted:

06 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Growth Conditions

2.2. Cytokinin Analyses

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

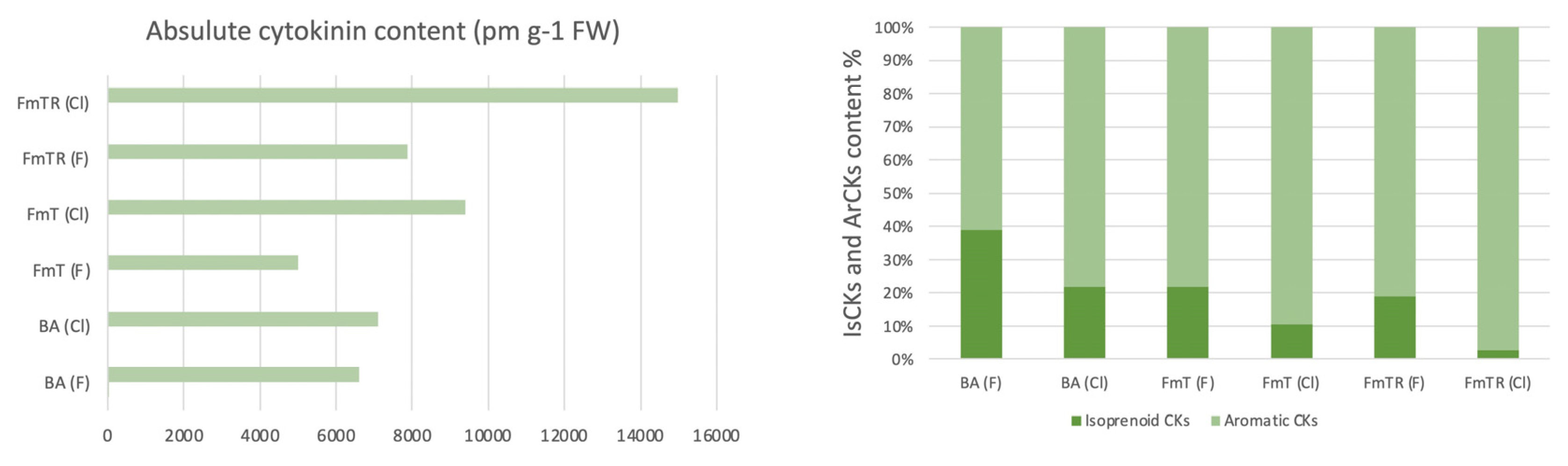

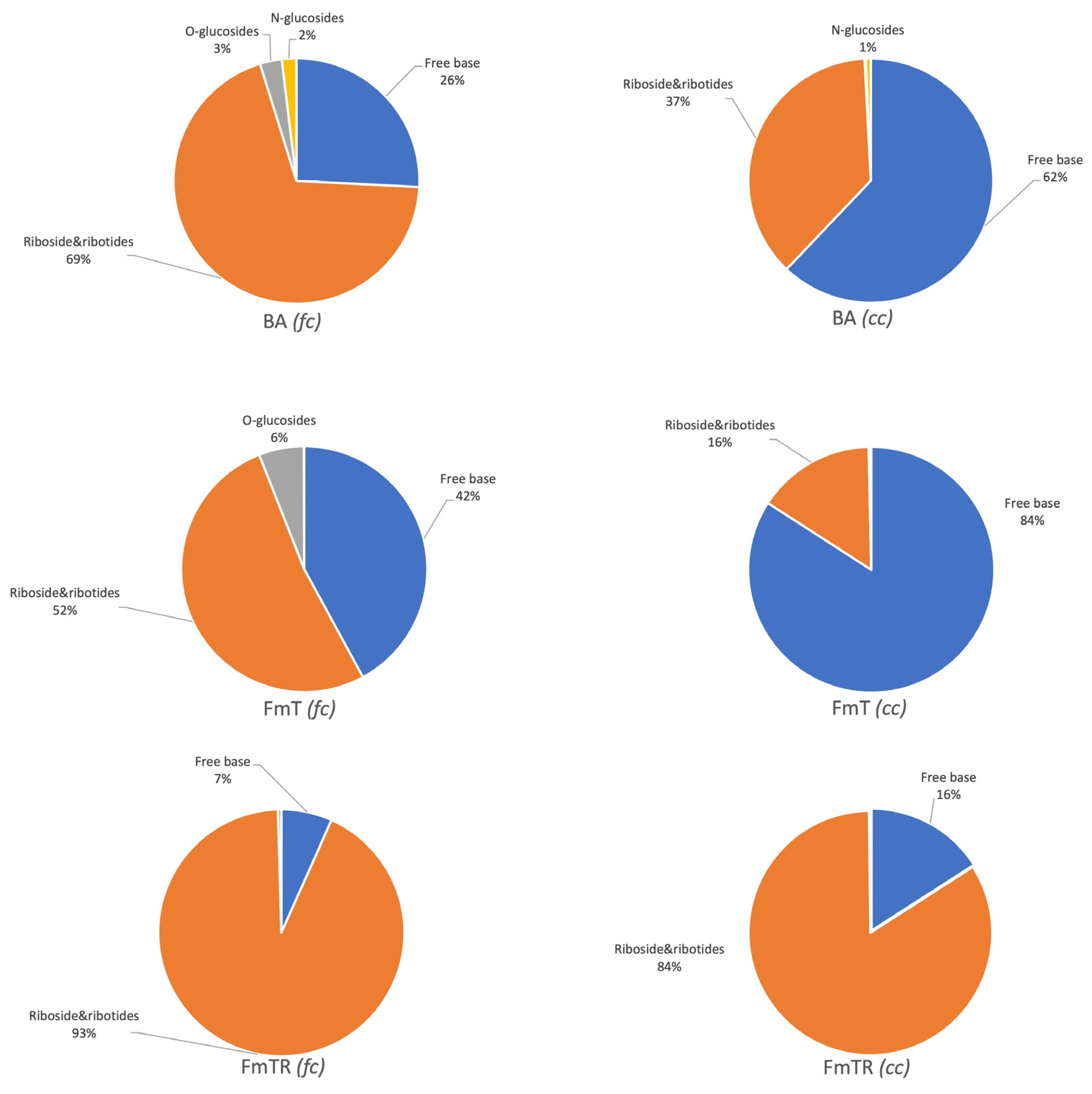

3.1. Effect of Exogenously Administered Cytokinins (CKs) on Total Quantified CK Levels and Their Metabolic Profile

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Murvanidze N, Doležal K, Werbrouck SP. Fluorine containing topolin cytokinins for Phalaenopsis Amabilis (L.) blume micropropagation. Propag Ornam Plants. 2019, 19, 48–51.

- Plíhalová L. Synthesis and chemistry of meta-Topolin and related compounds. Meta-topolin: A Growth Regulator for Plant Biotechnology and Agriculture. 2021, 11–22.

- Kieber JJ, Schaller GE. Cytokinin signaling in plant development. Development 2018, 145(4), dev149344. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh J, Sengar RS, Prasad M, Kumar A. Effect of Different Plant Growth Regulators on In-vitro Micropropagation of Banana Cultivar Grand Naine (Musa spp.). J Adv Biol Biotechnol. 2024, 27(3), 90–98.

- Mazri MA. Role of cytokinins and physical state of the culture medium to improve in vitro shoot multiplication, rooting and acclimatization of date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) cv. Boufeggous. J Plant Biochem Biotechnol. 2015, 24, 268–275. [CrossRef]

- Zürcher E, Müller B. Cytokinin synthesis, signaling, and function—advances and new insights. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2016, 324, 1–38.

- Aremu AO, Bairu MW, Szüčová L, Doležal K, Finnie JF, Van Staden J. Genetic fidelity in tissue-cultured ‘Williams’ bananas–The effect of high concentration of topolins and benzyladenine. Sci Hortic. 2013, 161, 324–327. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad MZ, Hussain I, Roomi S, Zia MA, Zaman MS, Abbas Z, Shah SH. In vitro response of cytokinin and auxin to multiple shoot regeneration in Solanum tuberosum L. Am Eurasian J Agric Environ Sci. 2012, 12(11), 1522–1526.

- Sakakibara H. Cytokinins: activity, biosynthesis, and translocation. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2006; 57:431-449.

- Mok DWS, Mok MC. Cytokinin metabolism and action. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2001, 52, 89–118. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klemš M, Plačková L, Doležal K, Bettaieb T, Werbrouck SP. Changes in cytokinin levels and metabolism in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.) explants during in vitro shoot organogenesis induced by trans-zeatin and dihydrozeatin. Plant Growth Regul. 2011, 65, 427–437. [CrossRef]

- Abdouli D, Plačková L, Doležal K, Bettaieb T, Werbrouck SP. Topolin cytokinins enhanced shoot proliferation, reduced hyperhydricity and altered cytokinin metabolism in Pistacia vera L. seedling explants. Plant Sci. 2022, 322, 111360. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdouli M, Plačková L, Doležal K, Bettaieb T, Werbrouck SP. Cytokinin regulation in in vitro plant propagation. J Plant Growth Regul. 2022.

- Smykalova I, Plačková L, Doležal K, Bettaieb T, Werbrouck SP. The role of cytokinin regulation in micropropagation. Plant Cell Rep. 2019, 38, 123–132.

- Novák O, Hauserová E, Amakorová P, Doležal K, Strnad M. Cytokinin profiling in plant tissues using ultra-performance liquid chromatography–electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. Phytochemistry. 2008, 69(11), 2214–2224.

- Plačková L, Hrdlička J, Smýkalová I, Cvečková M, Novák O, Griga M, Doležal K. Cytokinin profiling of long-term in vitro pea (Pisum sativum L.) shoot cultures. Plant Growth Regul. 2015, 77, 125–132. [CrossRef]

- Schäfer M, Plačková L, Doležal K, Bettaieb T, Werbrouck SP. The role of cis-zeatin-type cytokinins in plant growth regulation and mediating responses to environmental interactions. J Exp Bot. 2015, 66(16), 4873–4884.

- Kamada-Nobusada T, Sakakibara H. Molecular basis for cytokinin biosynthesis. Phytochemistry 2009, 70(4), 444–449. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kieber JJ, Schaller GE. Cytokinins. The Arabidopsis Book/American Society of Plant Biologists. 2014;12.

- Werbrouck SP, Doležal K, Strnad M, Van Staden J. Meta-topolin, an alternative to benzyladenine in tissue culture? Physiol Plant. 1996, 98(2), 291–297. [CrossRef]

- Van Staden J, Drewes FE. The stability and metabolism of benzyladenine glucosides in soybean callus. J Plant Physiol. 1992, 140(1), 92–95. [CrossRef]

- Galuszka P, Popelková H, Werner T, Frébortová J, Pospíšilová H, Mik V, Köllmer I, Schmülling T, Frébort I. Biochemical characterization of cytokinin oxidases/dehydrogenases from Arabidopsis thaliana expressed in Nicotiana tabacum L. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation. 2007 Sep; 26:255-67.

- Holub J, Plačková L, Doležal K, Strnad M. Biological activity of cytokinins derived from ortho-and meta-hydroxybenzyladenine. Plant Growth Regul. 1998, 26, 109–115. [CrossRef]

| |

Cytokinin treatment | |||||

| BA | FmT | FmTR | ||||

| Cytokinin metabolites |

Container type | |||||

| Filtered | Closed | Filtered | Closed | Filtered | Closed | |

| tZ | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| tZOG | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| tZR | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| tZROG | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| tZ7G | 20.2 ± 2.07 | 4.9±0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.05 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| tZ9G | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| tZR5´MP | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| cZ | 20.8 ± 2.5 | 11.09 ± 1.4 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| cZOG | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| cZR | 2059.5 ± 96.3 | 1296.1 ± 9.8 | 743.5 ± 56.5 | 893.7 ± 77.0 | 1362.8 ± 129.3 | 270.5 ± 21.8 |

| cZROG | 26.1 ± 1.7 | 11.3 ± 0.5 | <LOD | 3.85 ± 0.2 | <LOD | 4.1 ± 0.1 |

| cZ7G | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| cZ9G | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 8.6 ± 0.2 | <LOD | 6.1 ± 0.4 |

| cZR5´MP | <LOD | 74.6 ± 5.3 | <LOD | 40.7 ± 3.6 | <LOD | 66.1 ± 3.9 |

| DHZ | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| DHZOG | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| DHZR | 5.7 ± 0.8 | 3.8 ± 0.3 | 3.4 ± 0.06 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | <LOD | <LOD |

| DHZROG | 164.1 ± 4.8 | <LOD | 296.6 ± 20.1 | <LOD | 34.9 ± 1.1 | <LOD |

| DHZ7G | <LOD | 3.3 ± 0.07 | <LOD | 2.4 ± 0.2 | <LOD | 3.8 ± 0.1 |

| DHZ9G | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| DHZR5´MP | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| iP | 8.6 ± 0.1 | 5.2 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 3.1 ± 0.2 | 3.1 ± 0.3 | 2.5 ± 0.2 |

| iPR | 272.9 ± 4.7 | 125.8 ± 5.3 | 53.2 ± 1.1 | 22.1 ± 0.4 | 87.07 ± 3.8 | 23.8 ±1.2 |

| iP7G | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| iP9G | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| iPR5´MP | <LOD | 21.5 ± 2.03 | <LOD | 14.4 ± 1.3 | <LOD | 20.01 ± 0.8 |

| BA | 1398.3 ± 151.1 | 4159.68 ± 497.2 | 9.03 ± 0.6 | 15.4 ± 3.1 | <LOD | <LOD |

| BAR | 84.04 ± 2.9 | 61.4 ± 1.3 | 0.5 ± 0.09 | <LOD | 1.1 ± 0.08 | 3.1 ± 0.3 |

| BA7G | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| BA9G | 106.5 ± 3.4 | 37.3 ± 1.3 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| BAR5´MP | <LOD | 19.1 ± 0.4 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| mT | 30.8 ± 1.9 | 16.1 ± 0.3 | <LOD | 9.1 ± 1,0 | <LOD | 19.4 ± 1.3 |

| mTR | 67.2 ± 6.3 | 17.5 ± 0.9 | 27.1 ± 1.3 | 7.8 ± 0. 2 | 32.2 ± 2.0 | 26.6 ± 1.8 |

| mT7G | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| mT9G | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 16.8 ± 0,1 | <LOD | 15.1 ± 1.3 |

| oT | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| oTR | 17.1 ± 1.5 | 4.7 ± 0.4 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| oT7G | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| oT9G | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| pT | 147.6 ± 9.4 | 27.8 ± 2.3 | 140.7 ± 10.6 | <LOD | 196.5 ± 6.1 | <LOD |

| pTR | 1242.2 ± 27.8 | 251.9 ± 17.8 | 1142.1 ± 24.9 | 21.6 ± 0.8 | 1346.1 ± 74.4 | 25.8 ±1.3 |

| pT7G | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| pT9G | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| K | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| KR | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| K9G | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| FmT | 99.2 ± 11.2 | 140.8 ± 11.4 | 1952.3 ± 220.9 | 7836.4 ± 713.3 | 326.1 ± 25.4 | 2350.7 ± 360.5 |

| FmTR | 844.4 ± 107.2 | 804.2 ± 88.6 | 627.4 ± 44.5 | 490.7 ± 41.03 | 4478.6 ± 150.7 | 12156.5 ± 1712.8 |

| Values are presented as mean ± SD; LOD = below detection limit | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).