Submitted:

30 May 2024

Posted:

31 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. Insect Breeding

2.3. Extraction and Identification of Compounds

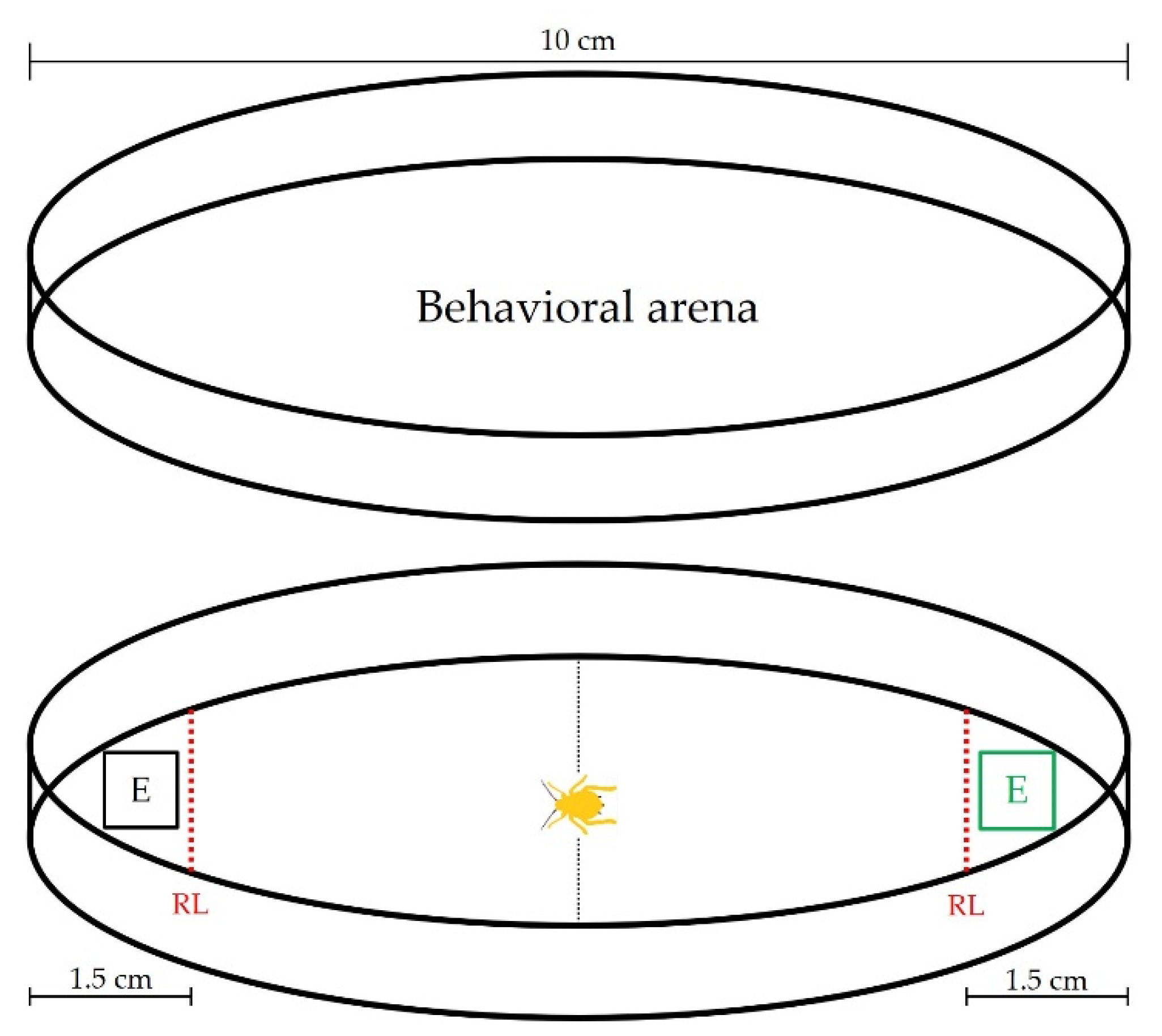

2.4. Bioassays Using Extracts from S. bicolor

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Extraction and Identification of Compounds

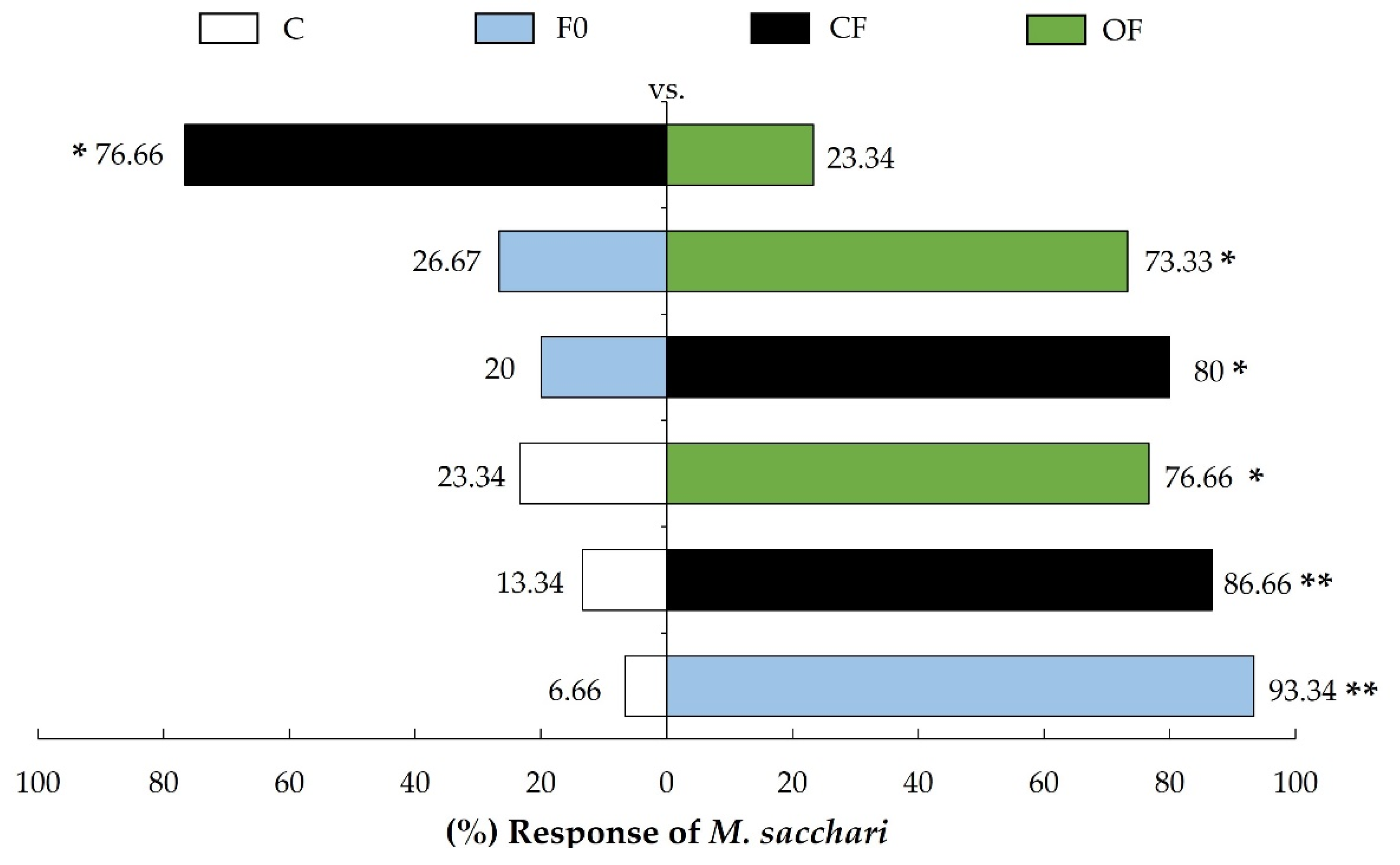

3.2. Bioassays Using Extracts from S. bicolor

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Peña-Martínez, R.; Brujanos-Muñiz, R.; Muñoz-Viveros, A.; Vanegas-Rico, J.; Salas, R.; Hernández-Torres, O.; Marín-Jarillo, A.; Ibarra, J.; Lomeli-Flores, R. Pulgón amarillo del sorgo, (PAS), Melanaphis sacchari (Zehntner, 1897), interrogantes biológicas y tablas de vida, 1st ed.; Fundación Produce Guanajuato A. C., Celaya Gto., México, 2018; pp 1-47.

- Garay, I.; Díaz, A.; Herrera, J.; Rubio, A.; Vázquez, C. Evaluación de cuatro híbridos de sorgo (Sorghum bicolor L), abonados con vermicompost en Úrsulo Galván, Ver. Braz. J. Anim. Environ. Res. 2021, 4, 1910–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xoconostle-Cázares, B.; Ramírez-Pool, J.A.; Núñes-Muñoz, L.A.; Calderón-Pérez, B.; Vargas-Hernández, B.Y.; Bujanos-Muñiz, R.; Ruiz-Medrano, R. The Characterization of Melanaphis sacchari Microbiota and antibiotic treatment effect on insects. Insects 2023, 14, 807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlickmann-Tank, J.; Morales-Galván, O.; Pineda-Pineda, J.; Espinosa-Vásquez, G.; Colinas-León, M.; Vargas-Hernández, M. Relationship between chemical fertilization in sorghum and Melanaphis sacchari/sorghi (Hemiptera: Aphididae) populations. Agronomía Colombiana 2020, 38, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudi, M.; Ruan, H.; Wang, L.; Lyu, J.; Sadler, R.; Connell, D.; Chu, C.; Phung, D. Agriculture development, pesticide application and its impact on the environment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, S.; Husain, T.; Prasad, S. Allelochemicals as biocontrol agents: Promising aspects, challenges and oppotunities. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2024, 166, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Vidal, G.; Bouysset, C.; Gévar, J.; Mbouzid, H.; Nara, C.; Delaroche, J.; Golebiowski, J.; Montagné, N.; Fiorucci, S.; Jacquin-Joly, E. Reverse chemical ecology in a moth: machine learning on odorant receptors identifies new behaviorally active agonists. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 78, 6593–6603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Ma, J.; Yang, F.; Zheng, H.; Lu, Z.; Qiao, F.; Zhang, K.; Gong, H.; Men, X.; Li, J.; Ouyang, F.; Ge, F. The hidden indirect environmental effect undercuts the contribution of crop nitrogen fertilizer application to the net ecosystem economic benefit. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 426, 139204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lescano, M.; Quintero, C.; Farji, A.; Balseiro, E. Excessive nutrient input an ecological cost for aphids by modifying their attractiveness toward mutualist ants. Funct. Ecol. 2022, 36, 2661–2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabroni, S.; Bontempo, L; Campanelli, G. ; Canali, S.; Montmurro, F. Innovative tools for the nitrogen fertilization traceability of organic farming products. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veromann, E.; Toome, M.; Kännaste, A.; Kaasik, R.; Copolovici, L.; Flink, J.; Kovács, G.; Narits, L.; Luik, A.; Niinemets, Ü. Effects of nitrogen fertilization on insect pests, their parasitoids, plant diseases and volatiles organic compounds in Brassica napus. Crop Prot. 2013, 43, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Jarosch, A.; Gauder, M.; Graeff-Hönninger, S.; Schnitzler, J.; Grote, R.; Rennenberg, H.; Kreuzwieser, J. VOC emissions and carbon balance of two bioenergy plantations in response to nitrogen fertilization: A comparison of Miscanthus and Salix. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 237, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, A.; Salas, N.; Parra, R.; González, A.; Soto, M.; Rodriguez, M.; Flores, M.; Chavez, A. Effect of conventional and organic fertilizers on volatile compounds of raspberry fruit. Not. bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2020, 48, 862–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paskovic, I.; Soldo, B.; Ban, S.; Rdic, T.; Lukic, M.; Urlic, B.; Mimica, M.; Bubola, K.; Colla, G.; Rouphael, Y.; Major, N.; Simpraga, M.; Ban, D.; Palcic, I.; Franic, M.; Grozic, K.; Lukic, I. Fruit quality and volatile compound composition of processing tomato as affected by fertilisation practices and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi application. Food Chem. 2021, 359, 129961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.; Jaafar, H.; Rahmat, A.; Rahman, Z. Effects of nitrogen fertilization on synthesis of primary and secondary metabolites in three varieties of Kacip Fatimah (Labisia Pumila Blume). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 5238–5254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, F.; Ribeiro, M.; Esteves, A.; delaCruz-Chacón, I.; Mayo, M.; Ferreira, G.; Fernandes, B. Nitrogen in the defense system of Annona emarginata (Schltdl.) H. Rainer. PLos ONE, 2019, 14, e0217930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becher, P.; Hagman, A.; Verschut, V.; Chakraborty, A.; Rozpedowska, E.; Lebreton, S.; Bengtsson, M.; Flick, G.; Witzgall, P.; Piskur, J. Chemical signaling and insect attraction is a conserved trait in yeast. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 8, 2962–2974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, W.; Yang, L.; Cao, H.; Pelosi, P.; Wang, G.; Wang. B. Aromatic volatiles and odorant receptor 25 mediate attraction of Eupeodes corollae to flowers. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 12212–12220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohonyai, Z.; Vuts, J.; Kárpáti, Z.; Koczor, S.; Domingue, M.; Fail, J.; Birkett, M.; Tóth, M.; Imrei, Z. Benzaldehyde: an alfalfa related compound for the spring attraction os pest weevil Sitona humeralis (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Pest. Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 3153–3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamwasa, I.; Li, K.; Zhang, S.; Yin, J.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Li, E.; Sun, X. Overlooked side effects of organic farming inputs attract soil insect crop pests. Ecol. Appl. 2020, 30, e02084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, N.; Weston, P.; Barrow, R.; Weston, L.; Gurr, G. Contrasting volatilomes of livestock dung drive preference of the dung beetle Bubas bison (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae). Molecules 2022, 27, 4152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobarak, S.; Koner, A.; Debnath, R.; Barik, A. The role of gram plant volatile blends in the behavior of arctiid moth, Spilosoma obliqua. J. Chem. Ecol. 2022, 48, 802–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokharel, S.; Zhong, Y.; Changning, L.; Shen, F.; Likun, L.; Parajulee, M.; Fang, W.; Chen, F. Influence of reduced N-fertilizer application on foliar chemicals and functional qualities of tea plants under Toxoptera aurantii infestation. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, D.; Meng, Z.; Dong, Z.; Lin, Y.; Chen, S.; Xia, Q.; Zhao, P. Wild silkworm cocoon contains more metabolites than domestic silkworm cocoon to improve its protection. J. Insect Sci. 2017, 17, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrigui, N.; Sari, D.; Sari, H.; Eker, T.; Cengiz, M.; Ikten, C.; Toker, C. Introgression of resistance to Leafminer (Liriomyza cicerina Rondani) from Cicer reticulatum Ladiz. to C. arietinum L. and relationships between potential biochemical selection criteria. Agronomy 2021, 11, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidambaram, K.; Alqahtani, T.; Alghazwani, Y.; Aldahish, A.; Annadurai, S.; Venkatesan, K.; Dhandapani, K.; Thilagam, E.; Venkatesan, K.; Paulsamy, P.; Vasudevan, R.; G. Kandasamy. Medicinal plants of Solanum species: the promising sources of phyto-insecticidal compounds. J. Trop. Med. 2022, 2022, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, J.; Vieira, E.; Riffel, A.; Birkett, M.; Bleicher, E.; Goulart, A. Differential preference of Capsicum spp. Cultivars by Aphis gossypii is conferren by variation in volatile semiochemistry. Euphytica 2010, 177, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dancewicz, K.; Kordan, B.; Gabrys, B.; Szumny, A.; Wawrzenczyk, C. Feeding deterrent activity of α-methylenelactones to pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum (Harris) and green peach aphid Myzus persicae (Sulzer). Pol. J. Nat. Sci. 2006, 20, 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, H.; Li, W.; Xu, M.; Xu, D.; Wan, P. The role of tetradecane in the identification of host plants by the mirid bugs Apolygus lucorum and Adelphocoris suturalis and potential application in pest management. Front. physiol. 2022, 13, 1061817. [Google Scholar]

- Alabi, O.; Onochie, I. Repellence and attraction properties of selected synthesized volatile organic compounds to flower bud thrips (Megalurothrips sjostedti Trybom). Adeleke University J. Eng. Technol. 2023, 6, 142–150. [Google Scholar]

- Barrios, M.; García, J.; Basso, C. Efecto de la fertilización nitrogenada sobre el contenido de nitrato y amonio en el suelo y la planta de maíz. Bioagro 2012, 24, 213–220. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, C; Lai, H. Comprehensive assessment of the influence of applying two kinds of chicken-manure-proccessed organic fertilizers on soil properties, mineralization of nitrogen, and yields of three crops. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Darshanee, H.; Khan, I.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, T. Host selection behavior of the green peach aphid, Myzus persicae, in response to volatile organic compounds and nitrogen contents of cabbage cultivars. Front. Plant Sci, 2019, 10, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamnqa, U.; Etsassala, N.; Akinpelu, E.; Nchu, F. Effects of varying nitrogen fertilization on growth, yield and flowering of Capsicum annuum (California wonder). 18th SOUTH AFRICA Int’l Conference on Agricultural, Chemical, Biological and Environmental Sciences (ACBES-20), Johannesburg, 16-17 nov, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Aqueel, M.; Leather, S. Effect of nitrogen fertilizer on the growth and survival of Rhopalosiphum padi (L.) and Sitobion avenae (F.) (Homoptera: Aphididae) on different wheat cultivars. Crop Protec. 2011, 30, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Hui, C.; He, D.; Li, B. Effects of agricultural intensification on ability of natural enemies to control aphids. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 8024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallahpour, F.; Ghorbani, R.; Nassiri, M.; Hosseini, M. Plant fertilization helps plants to compensate for aphid damage, positively affects predator efficiency and improves canola yield. J. Pest Sci. 2019, 93, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staley, J.; Stewar, A.; Pope, T.; Wright, D.; Leather, S.; Hadley, P.; Rossiter, J.; Emden, H.; Poppy, G. Varying responses of insect herbivores to altered plant chemistry under organic and conventional treatments. Proc. R. Soc. 2010, 277, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naroz, M.; Mahmoud, H.; El-Rahman, S. Influence of fertilization and plant density on population of some maize insects pests yield. J. Plant Prot. Pathol. 2021, 12, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, R.; Villa, P.; López, J.; Huerta, A.; Pacheco, J.; Ramos, M. Nitrogen fertilization sources and insecticidal activity of aqueous seeds extract of Carica papaya against Spodoptera frugiperda in maize. Cienc. Invest. Agrar. 2013, 40, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, R.; Schmidt, J.; Igwe, A.; Cheung, A.; Vannette, R.; Gaudin, C.; Casteel, C. Organic mangement promotes natural pest control through altered plant resistance to insects. Nat. Plants 2020, 6, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowen, E.; Tooker, J.; Blubaugh, C. Managing fertility with animal waste to promote arthropod pest suppression. Biol. Control 2019, 134, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parizad, S.; Bera, S. The effect of organic farming on water reusability, sustainable ecosystem, and food toxicity. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 30, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Xu, R.; Du, Z.; Ye, H.; Tian, J.; Huang, W.; Xu, S.; Xu, F.; Hou, M.; Zhong, F. Molecular regulation of volatile organic compounds accumulation in tomato leaf by different nitrogen treatments. Plant Growth Regul. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holopainen, J. Importance of olfactory and visual signals of autumn leaves in the coevolution of aphids and trees. Bioessays 2008, 30, 889–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrieri, E.; Digilio, M. Aphid-plant interactions: a review. J. Plant Interact. 2012, 3, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatments | Description |

|---|---|

| F0 | Soil (4.4% organic material; nitrogen 100 ppm; phosphorus 0.80 ppm; potassium 5.50 ppm and pH 7.4) |

| CF OF |

200 kg ha-1 N (ammonium sulfate) + soil 200 kg ha-1 N (poultry manure) + soil |

| Bioassay | Combinations extracts |

|---|---|

| 1 | CF vs. OF |

| 2 | F0 vs. OF |

| 3 | F0 vs. CF |

| 4 | C vs. OF |

| 5 | C vs. CF |

| 6 | C vs. F0 |

| Number | Compound | Area F0 (%) | Area CF (%) | Area OF (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Butyric acid | ND | 0.33 | ND |

| 2 | Tridecyl trifluoroacetate | ND | 0.15 | ND |

| 3 | (R)-2-octanol | ND | 0.21 | ND |

| 4 | Propanoic acid | ND | 0.36 | ND |

| 5 | 1-Methyldecylamine | 1.43 | ND | ND |

| 6 | Ethylamine | ND | 0.28 | ND |

| 7 | 4-methyl-2-Pentanamine | ND | 0.33 | ND |

| 8 | 4-fluorohistamine | ND | 0.61 | ND |

| 9 | 1-undecanol | 7 | ND | 2.69 |

| 10 | 2H-pyran-2-one | ND | 5.48 | ND |

| 11 | 2-heptanol | ND | 0.35 | ND |

| 12 | Acetic acid | ND | 0.63 | ND |

| 13 | (2,3-dimethyloxiranyl) methanol | ND | 0.39 | ND |

| 14 | 2,3-diethoxy-propionic acid, ethyl ester | ND | 0.42 | ND |

| 15 | 2-nonanol | ND | 0.24 | ND |

| 16 | Butanedioic acid | 2.24 | 1.83 | 1.09 |

| 17 | 1-tetradecene | 6.36 | 5.47 | 2.5 |

| 18 | 1-(1-propynyl)-cyclohexene | ND | 0.42 | ND |

| 19 | (Z)-7-hexadecene | 3.4 | 2.85 | 1.46 |

| 20 | Phenol | 22.64 | 23.35 | 14.01 |

| 21 | 4-(2-methylamino)ethyl)pyridine | ND | 0.04 | ND |

| 22 | 2-fluoro-2′,4,5-trihydroxy-N-methyl-benzenethanamine | ND | 0.89 | ND |

| 23 | (E)-5-octadecene | ND | 0.93 | 0.55 |

| 24 | N,N′-dimethyl-2-butene-1,4-diamine | 0.68 | ND | ND |

| 25 | 1-dodecanamine | ND | 1.53 | ND |

| 26 | 4-hydroxy-benzeneacetonitrile | ND | 5.29 | ND |

| 27 | N,N-dimethyl-dimethylphosphoric amide | ND | 0.39 | ND |

| 28 | 2-Octyl benzoate | ND | 0.72 | ND |

| 29 | Benzophenone | ND | 1.06 | 0.69 |

| 30 | N-(3-pyridinylmethylene)benzenamine | 1.09 | ND | ND |

| 31 | 4-amino-2-oxy-furazan-3-carboxylic acid | ND | 0.20 | ND |

| 32 | Piperidin-4-ol, 1,3,3-trimethyl-4phenyl | ND | 0.37 | ND |

| 33 | Benzene, 4-bromo-1,3-dimethoxy-6-(4-acetylphenyliminomethyl) | ND | ND | 0.93 |

| 34 | Phthalic acid, isobutyl 4-isopropylphenyl ester | ND | 0.24 | ND |

| 35 | 9-hydroxy-3,4-dihydro-2H-1,4-ethanoquinoline-9-carboxylic acid | ND | ND | 1.14 |

| 36 | 5,6-dihydro-2-(4-nitrophenyl)-4H-1,3-oxazin-5-one | ND | 0.11 | ND |

| 37 | 1H-pyrrolo [1,2-a]benzimidazolium,2,3-dihydro-4-(1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-6-hydroxy-1,3-dimethyl-2,4-dioxo-5-pyrimidinyl)-, hydroxide | ND | ND | 1.07 |

| 38 | 5-[[[3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl]imino]methyl]-2,4-pyrimidinediamine | ND | 37.73 | ND |

| 39 | (4-methoxy-phenyl)-(5-p-tolyl-furan-2-ylmethylene)-amine | 46.89 | ND | 68.02 |

| 40 | 1,2-benzenedicarboxylic acid | ND | 0.77 | 1.62 |

| 41 | 2-methyl-benzothiazole | 0.55 | ND | ND |

| 42 | 2-bromo-N-methyl-2-propen-1-amine | ND | 0.35 | ND |

| 43 | 4-methyl-2-pentanamine | 0.83 | ND | ND |

| 44 | (2,2-dichlorocyclopropyl)methanol | 0.06 | ND | ND |

| 45 | 1,3-benzenedicarboxylic acid | ND | 0.34 | ND |

| 46 | 4-phenoxy-2-phenyl-1-naphthalenol | ND | ND | 1.06 |

| 47 | 3-methyl-1-(4-toluidino)pyrido [1,2-a]benzimidazole-4-carbonitrile | ND | ND | 0.2 |

| 48 | 5-(p-aminophenyl)-4-(p-nitrophenyl)-2-thiazolamin | ND | ND | 0.3 |

| 49 | 2-oxo-1,4,5-triphenyl-4-imidazolin | ND | ND | 0.68 |

| Number of compounds detected per treatment | 12 | 34 | 16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).