Submitted:

30 May 2024

Posted:

30 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

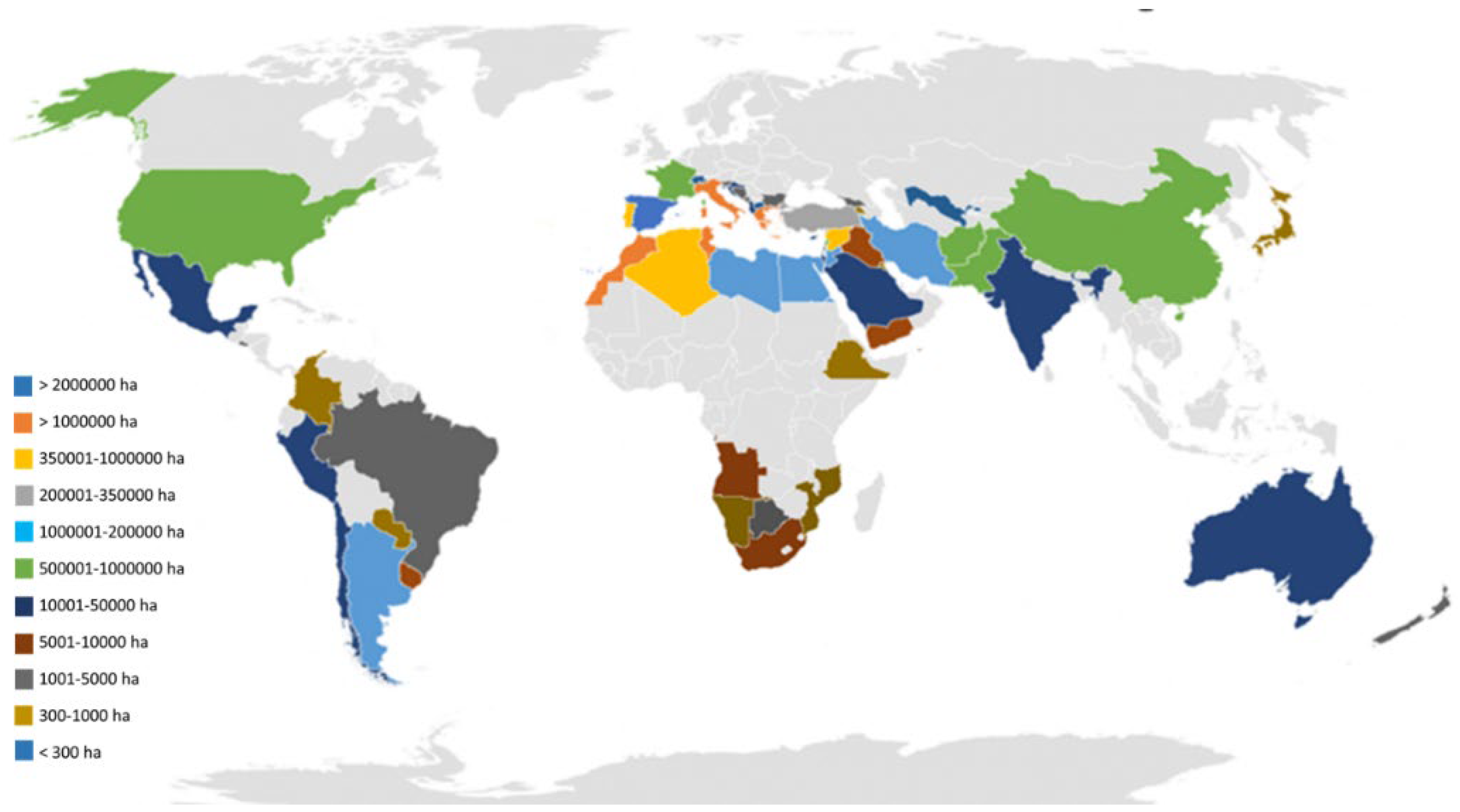

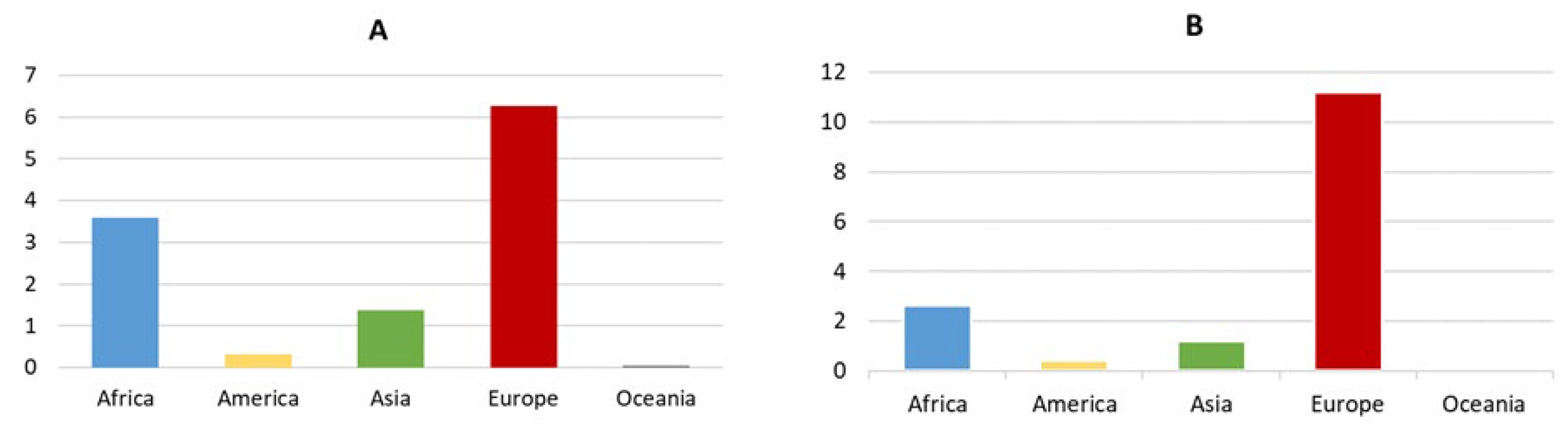

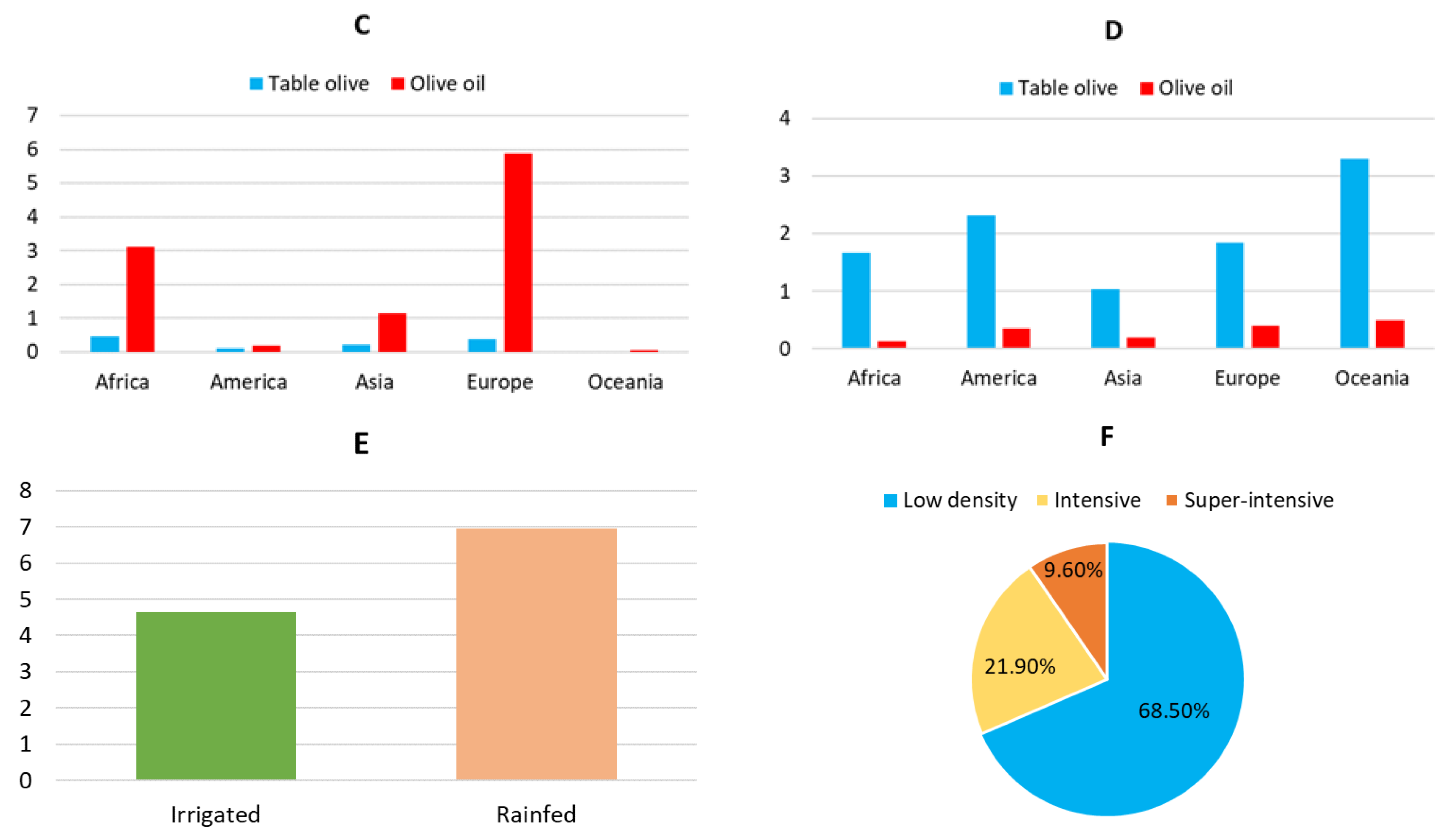

1.1. Olive Tree Cultivation

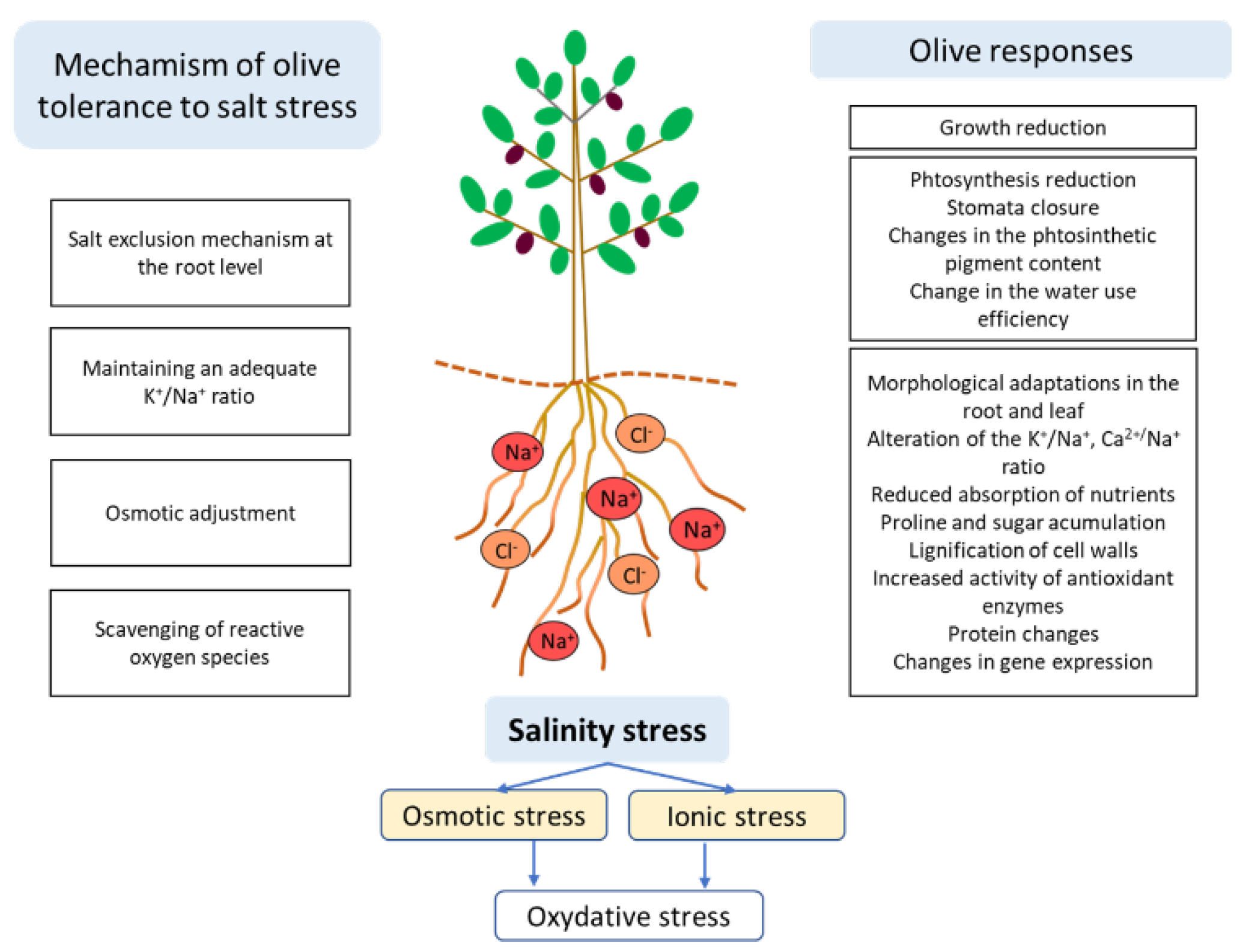

2. Mechanisms of Olive Tolerance to Salt Stress

3. Morphological, Anatomical and Physiological Adaptation of the Olive Tree to Salt Stress

3.1. Morphological and Anatomical Adaptation

3.2. Physiological Adaptation

3.3. Water Relations

4. Biochemical Mechanisms in Olive for Adaptation to Salt Stress

4.1. Mineral Nutrients

4.2. Osmotic Adjustment

4.2.1. Proline Accumulation

4.2.2. Sugar Accumulation

4.3. Cell Wall Modification

4.4. Antioxidant Defense Activity

4.5. Lipid Peroxidation

4.6. Adaptations at Protein Level

5. Molecular Mechanisms in Olive for Adaptation to Salt Stress

6. Factors Affecting Salinity Tolerance

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mukhopadhyay, R.; Sarkar, B.; Jat, H.S.; Sharma, P.C.; Bolan, N.S. Soil salinity under climate change: Challenges for sustainable agriculture and food security. J. Environ. Manage. 2021, 280, 111736. [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, M.; Wilmes, P.; Schrader, S. Measuring soil sustainability via soil resilience. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 626, 1484–1493. [CrossRef]

- Yuvaraj, M.; Bose, K.S.C.; Elavarasi, P.; Tawfik, E. Soil salinity and its management. In Soil Moisture Importance. Meena, R.S., Datta, R., Eds. IntechOpen, 2021; pp. 109–119. https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/72995.

- El hasini, S.; Halima, I.O.; Azzouzi, M.E.; Douaik, A.; Azim, K.; Zouahri, A. Organic and inorganic remediation of soils affected by salinity in the sebkha of sed el mesjoune – marrakech (Morocco). Soil Tillage Res. 2019, 193, 153–160. [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.; Regni, L.; Bocchini, M.; Mariotti, R.; Cultrera, N.G.M.; Mancuso, S.; Googlani, J.; Chakerolhosseini, M.R.; Guerrero, C.; Albertini, E.; Baldoni, L.; Proietti, P. Physiological, epigenetic and genetic regulation in some olive cultivars under salt stress. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1093. [CrossRef]

- Field, C.B.; Barros, V.R.; Mach, K.J.; Mastrandrea, M.D. Technical summary. In In: Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Field, C.B., Barros, V.R., Dokken, D.J., Mach, K.J., Mastrandrea, M.D., Bilir, T.E., Chatterjee, M., Ebi, K.L., Estrada, Y.O., Genova, R.C., Girma, B., Kissel, E.S., Levy, A.N., MacCracken, S., Mastrandrea, P.R., White, L.L., Eds. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 35-94.

- Chartzoulakis, K. Salinity and olive: Growth, salt tolerance, photosynthesis and yield. Agric. Water Manag. 2005, 78, 108–121. [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Motos, J.R.; Ortuño, M.F.; Álvarez, S.; Hernández, J.A.; Sánchez-Blanco, M.J. The use of reclaimed water is a viable and safe strategy for the irrigation of myrtle plants in a scenario of climate change. Water Supply. 2019, 19, 1741-1747. [CrossRef]

- Meena, M.D.; Yadav, R.K.; Narjary, B.; Gajender, Y.; Jat, H.S.; Sheoran, P.; Meena, M.K.; Antil, R.S.; Meena, B.L.; Singh, H.V.; Meena, V.S.; Rai, P.K.; Ghosh, A.; Moharana, P.C. Municipal solid waste (MSW): Strategies to improve salt affected soil sustainability: A review. Waste Manage. 2019. 84, 38-53. [CrossRef]

- Romero-Trigueros, C.; Vivaldi, G.A.; Nicolás, E.N.; Paduano, A.; Salcedo, F.P.; Camposeo, S. Ripening Indices, Olive Yield and Oil Quality in Response to Irrigation with Saline Reclaimed Water and Deficit Strategies. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1243. [CrossRef]

- Vivaldi, G.A.; Camposeo, S.; Lopriore, G.; Romero-Trigueros, C.; Salcedo, F.P. Using saline reclaimed water on almond grown in Mediterranean conditions: Deficit irrigation strategies and salinity effects. Water Supply. 2019, 19, 1413–142. [CrossRef]

- Ansari, F.A.; Ahmad, I.; Pichtel, J. Growth stimulation and alleviation of salinity stress to wheat by the biofilm forming Bacillus pumilus strain FAB10. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2019, 143, 45–54. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, S.; Gaurav, A. K.; Srivastava, S.; Verma, J. P. Plant growth-promoting bacteria: Biological tools for the mitigation of salinity stress in plants. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1216. [CrossRef]

- Galicia-Campos, E.; Garcia-Villaraco, A.; Montero-Plamero, M.B.; Gutierrez-Mañero, F.J.; Ramos-Solano, B. Modulation of photosynthesis and ROS scavenging response by benficial bacteria in Olea europaea Plantlets under Salt Stress Conditions. Plants. 2022, 11, 2748. [CrossRef]

- Bhise, K.K.;Bhagwat, P.K.; Dandge, P.B. Synergistic effect of Chryseobacterium gleum sp. SUK with ACC deaminase activity to alleviate salt stress and promote plant growth in Triticum aestivum L. 3 Biotech. 2017, 7, 105. [CrossRef]

- Zamanzadeh-Nasrabadi, S.M.; Mohammadiapanah, F.; Sarikhan, S.; Shariati, V.; Saghafi, K.; Hosseini-Mazinani, M. Comprehensive genome analysis of Pseudomonas sp. SWRIQ11, a new plant growth-promoting bacterium that alleviates salinity stress in olive. 3 Biotech. 2023, 13, 347. [CrossRef]

- Shekafandeh, A.; Sirooeenejad, S.; Alsmoushtaghi, E. Influence of gibberellin on increasing of sodium chloride tolerance via some morpho-physiological changes in two olive cultivars. Agric. Conspec. Sci. 2017, 82, 367-373. https://acs.agr.hr/acs/index.php/acs/article/view/1225.

- Metheni, K.; Abdallah, M.B.; Nouairi, I; Smaoui, A.; Ammar, B.; Zarrouk, M.; Youssef, N.B. Salicylic acid and calcium pretreatments alleviate the toxic effect of salinity in the Oueslati olive variety. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 233, 349-358. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, B.; Huang, B. Mechanism of salinity tolerance in plants: Physiological, biochemical, and molecular characterization. Int. J. Genom. 2014, 2014, 701596. [CrossRef]

- Moula, I.; Boussadia, O.; Koubouris, G.; Hassine, MB; Boussetta, W.; van Labeke, MC; Braham, M. Ecophysiological and biochemical aspects of olive (Olea europaea L.) in response to salt stress and gibberellic acid-induced relief. S. Africa. J.Bot. 2020, 132, 38–44. [CrossRef]

- Cordovilla, M.P.; Aparicio, C.; Melendo, M.; Bueno, M. Exogenous application of indol-3-acetic and salicylic acid improves tolerance to salt stress in olive plantlets (Olea europaea L. cultivar Picual) in growth chamber environments. Agronomy, 2023, 13, 647. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, J.; Zhu, T., Zhao, C.; Li, L.; Chen, M. The Role of Melatonin in Salt Stress Responses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1735. [CrossRef]

- Zhan, H.; Nie, X.; Zhang, T.; Li, S.; Wang, X.; Du, X.; Tong, W.; Song W. Melatonin: A small molecule but important for salt stress tolerance in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 709. [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, S.M.; Hosseini, M.S.; Hoveizeh N.F.; Gholami, R.; Abdelrahman, M.; Phan Tran, L.S. Exogenous melatonin mitigates salinity-induced damage in olive seedlings by modulating ion homeostasis, antioxidant defense, and phytohormone balance. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 173, 1682-1694. [CrossRef]

- Khan, T.A., Saleem, M., Fariduddin, Q. Recent advances and mechanistic insights on Melatonin-mediated salt stress signaling in plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 188, 97-107. [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; He, F.; Wu, T.; Li, B.; Xiao, J.; Wang, Z. Breaking the salty spell: Understanding action mechanism of melatonin and beneficial microbes as nature’s solution for mitigating salt stress in soybean. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2023, 161, 555-567. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Decsi, K.; Tóth, Z. Different tactics of synthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles, homeostasis ions, and phytohormones as regulators and adaptatively parameters to alleviate the adverse effects of salinity stress on plants. Life 2022, 13, 73. [CrossRef]

- Sarraf, M.; Vishwakarma, K.; Kumar, V.; Arif, N.; Das, S.; Johnson, R. Metal/Metalloid-Based Nanomaterials for Plant Abiotic Stress Tolerance: An Overview of the Mechanisms. Plants 2022, 11, 316. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Tóth, Z.; Decsi, K. The Impact of Salinity on Crop Yields and the Confrontational Behavior of Transcriptional Regulators, Nanoparticles, and Antioxidant Defensive Mechanisms under Stressful Conditions: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2654. [CrossRef]

- Al-Saif, A.M.; Sas-Paszt, L.; Mosa, W.F.A. Olive performance under the soil application of humic acid and the spraying of titanium and zinc nanoparticles under soil salinity stress. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 295. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Singh, R.; Upadhyay, S.K.; Verma, K.K.; Tripathi, R.M.; Liu, H.; Dhankher, O.P.; Tripathi, R.D.; Sahi, S.V.; Seth, C.S. Review on interactions between nanomaterials and phytohormones: Novel perspectives and opportunities for mitigating environmental challenges. Plant Sci. 2024, 340, 111964. [CrossRef]

- Bernard, G.; Khadari, B.; Naavascues, M.; Fernandez-Mazuecos, M.; El Bakkali, A.: Arrigo, N.; Baali-Cherif, D.; Caraffa, B.B.; Santoni, S.; Vargas, P.; Savolainen, V. The complex history of the olive tree: From Late Quaternary diversification of Mediterranean lineages to primary domestication in the northern Levant. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2013, 280, 1756. [CrossRef]

- Zohary, D.; Hopf, M.; Weiss, E. Domestication of Plants in the Old World: The origin and spread of domesticated plants in Southwest Asia, Europe, and the Mediterranean Basin, 4th ed.; Oxford University Pres: Oxford, UK, 2012, pp. 193. [CrossRef]

- Vossen, P. Olive oil: History, production, and characteristics of the world’s classic oils. Hortscience 2007, 42, 1093–1100. [CrossRef]

- Schäfer-Schuchardt, H. Expansión cultural y artística. In VVAA, Enciclopedia Mundial del Olivo; Plaza and Jané: Barcelona, Spain, 1996, pp. 21-26.

- Besnard, G.; Terral, J.F.; Cornille, A. On the origins and domestication of the olive: A review and perspectives. Ana. Bot. 2018, 121, 385-403. [CrossRef]

- IOC. International Olive Council. 2018. Available online: https://www.internationaloliveoil.org (accesed on 11 April 2024).

- Vilar, J.; Pereira, J.E.; Urieta, D.; Menor, A.; Caño, S., Barreal, J.; Velasco, M.M.; Puentes, R. La olivicultura Internacional. Difusión histórica, análisis estratégico y visión descriptiva. Fundación Caja Rural: Jaén, Spain, 2018; pp. 153.

- IOC. International Olive Council. 2003. Available online: https://www.internationaloliveoil.org (accesed on 11 April 2024).

- IOC. International Olive Council. 2022. Available online: https://www.internationaloliveoil.org (accesed on 11 April 2024).

- Issaoui, M.; Flamini, G.; Brahmi, F.; Dabbou, S.; Ben Hassine, K.; Taamali, A.; Chehab, H.; Ellouz, M.; Zarrouk, M.; Hammami, M. Effect of the growing area conditions on differentiation between Chemlali and Chétoui olive oils. Food Chem. 2010, 119, 220-225. [CrossRef]

- Tous, J., Romero, A., Hermoso, J.F. New trends in olive orchard design for continuous mechanical harvesting. Adv. Hortic. Sci. 2010, 24, 43-52.

- Loumou, A.; Giourga, C. Olive groves: The life and identity of the Mediterranean. Agric. Human Values 2003, 20, 87-95.

- Pessoa, H.R.; Zago, L.; Chaves C.; Ferraz da Costa, D.C. Modulation of biomarkers associated with risk of cancer in humans by olive oil intake: A systematic review. J. Funct. Food. 2022, 98, 105275. [CrossRef]

- Fazlollahi, A.; Motlagh Asghari, K.; Aslan, C.; Noori, M.; Nejadghaderi, S.A.; Araj-Khodaei, M.; Sullman, M.J.M.; Karamzad, N., Kolahi; A.A.; Safiri S. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1218538. [CrossRef]

- Chrysant, S.G.; Chrysant, G.S. Olive Oil Consumption and Cardiovascular Protection: Mechanism of Action. Cardiol. Rev. 2024, 32, 57-61. [CrossRef]

- Therios, I.N. Olives; CABI: Oxfordshire, UK, 2009. Pp. 409.

- Munns, R.; Tester, M. Mechanisms of salinity tolerance. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2008, 59, 651-681. [CrossRef]

- Shabala S.; Wu, H.; Bose, J. Salt stress sensing and early signalling events in plant roots: Current knowlegde and hypothesis. Plant Sci. 2015, 241, 109–199. [CrossRef]

- Rugini, E.; Fedeli, E. Olive as an oilseed crop. In: Legumes and Oilseed Crops; Bajaj YPS ed.; Sorubger-Verlag: Berlín, Germany, 1990; pp 593-641.

- Gucci, R.; Tattini, M. Salinity tolerance in olive. Hortic. Rev. 1997, 21, 177-213.

- Chartzoulakis, K.; Loupassaki, M.; Bertaki, M.; Androulakis, I. Effects of NaCl salinity on growth, ion content and CO2 assimilation rate of six olive cultivars. Sci. Hortic. 2002, 96, 235–247. [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, C.; Urrestarazu, M.; Cordovilla, M.P. Comparative physiological analysis of salinity effects in six olive genotypes. HortScience 2014, 49, 901-904. [CrossRef]

- Regni, L.; Del Pino, AM; Mousavi, S.; Palmerini, California; Baldoni, L.; Mariotti, R.; Mairech, H.; Gardi, T.; D’Amato, R.; Proietti, P. Behaviour of four olive cultivars during salt stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 867. [CrossRef]

- Ayaz, M.; Varol, N.; Yolcu, S.; Pelvan, A.; Kaya,Ü.; Aydogdu, E.; Bor, M.; Ördemir, F.; Türkan, İ. Three (Turkish) olive cultivars display contrasting salt stress-coping mechanisms under high salinity. Trees. 2021. 35, 1283-1298. [CrossRef]

- Dbara, S.; Abboud, S.; Bchir, A. Foliar potassium nitrate spray induces changes in potassium-sodium balance and biochemical mechanisms in olive (Olea europaea L. cv Chemlali) plants submitted to salt stress. J. Hortic. Postharvest Res. 2022, 5, 309-322. [CrossRef]

- Boussadia, O.; Zgallai, H.; Mzid, N.; Zaabar, R.; Braham, M.; Doupis, G.; Koubouris, G. Physiological responses of two olive cultivars to salt stress. Plants 2023, 12, 1926. [CrossRef]

- Tattini, M. Ionic relations of aeroponically-grown olive plants during salt stress. Plant Soil. 1994. 161, 251-256. https://www.webofscience.com/wos/alldb/full-record/WOS:A1994NY60100011.

- Perica, S.; Goreta, S.; Selak, G.V. Growth, biomass allocation and leaf ion concentration of seven olive (Olea europaea L) cultivars under increased salinity. Sci. Hortic. 2008, 117, 123-129. [CrossRef]

- Bader, B.; Aissaoui, F.; Kmicha, I.; Ben Salem, A.; Chehab, H.; Gargouri, K.; Boujnah, D.; Chaieb, M. Effects of salinity stress water desalination, olive tree (Olea europaea L. cvs ’Picholine’, ’Meski’ and ’Ascolana’) growth and ion accumulation. Desalination. 2015, 364, 46-52. [CrossRef]

- Kchaou, H.; Larbi, A.; Gargouri, K.; Chaieb, M.; Morales, F.; Msallem, M. Assessment of tolerance to NaCl salinity of five olive cultivars, based on growth characteristics and Na+ and Cl- exclusion mechanisms. Sci. Hortic. 2010, 124, 306-315. [CrossRef]

- Palm, E.R.; Salzano, A.M.; Vergine, M., Negro, W.G.N.; Sabbatini, L.; Balestrini, R.; De Pinto, M.C.; Fortunato, S.; Gohari, G.; Mancuso, S.; Luvisi, A.; De Bellis, L.; Scaloni, A.; Vita, F. Response to salinity stress in four Olea europaea L. genotypes: A multidisciplinary approach. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2024, 218, 105586. [CrossRef]

- Soda, N.; Ephrath, J.E.; Dag, A.; Beiersdorf, I.; Presnov, E.; Yermiyahu, U.; Ben-Gal, A. Root growth dynamics of olive (Olea europaea L.) affected by irrigation induced salinity. Plant Soil 2017, 411, 305–318. [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Ben-Gal, A.; Shtein, I.; Bustan, A.; Dag, A.; Erel, R. Root structural plasticity enhances salt tolerance in mature olives. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2020. 179, 104224. [CrossRef]

- Horie, T.; Costa, A.; Kim, T.H.; Han, M.J.; Horie, R.; Leung, H.Y.; Miyao, A.; Hirochika, H.; An, G.; Schroeder, J.I. Rice OsHKT2;1 transporter mediates large Na+ influx component into K+-starved roots for growth. EMBO J. 2007, 26, 3003–3014. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, P.; Katschnig, D.; de Boer, A.H. HKT transporters—State of the art. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 20359–20385. [CrossRef]

- Hamamoto, S.; Horie, T.; Hauser, U.; Deinlein, U.; Schroeder, J.I.; Uozumi, N. HKT transporters mediate salt stress resistance in plants: From structure and function to the field. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2015, 32, 113–120. [CrossRef]

- Hao, H.; Wrang, Y.; Yan, V.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, S. A Review on Plant Responses to Salt Stress and Their Mechanisms of Salt Resistance. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 132. [CrossRef]

- Deinlein, U.; Stephan, A.B.; Horie, T.; Luo,W.; Xu, G.; Schroeder, J.I. Plant salt-tolerance mechanisms. Trends Plant Sci. 2014, 19, 371-379. [CrossRef]

- Connor, J.D.; Fereres, E. The physiology of adaptation and yield in olive. Hort. Rev. 2005, 31, 155–229.

- Chartzoulaki, K.S. Salinity and olive trees: Growth, salt tolerance, photosynthesis and yield. Agric. Water Manage. 2005, 78, 108–121. [CrossRef]

- Møller, I.S.; Gilliham, M.; Jha, D.; Mayo, G.M.; Roy, S.J.; Coates, J.C.; Haseloff, J.; Tester, M. Shoot Na+ exclusion and increased salinity tolerance engineered by cell type-specific alteration of Na+ transport in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2009, 21, 63–78. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.L.; Flowers, T.J.; Wang, S.M. Mechanisms of sodium uptake by roots of higher plants. Plant Soil 2010, 326, 45–60. [CrossRef]

- Fernández, J. Understanding olive adaptation to abiotic stresses as a tool to increase crop performance. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2014, 103, 158-179. [CrossRef]

- Rossi, L.; Francini, A.; Minnocci, A.; Sebastiani, L. Salt stress modifies apoplastic barriers in olive (Olea europaea L.): A comparison between a salt-tolerant and a saltsensitive cultivar. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 192, 38–46. [CrossRef]

- Tattini, M.; Lombardi, L.; Gucci, R. The effect of NaCl stress and relief on gas exchange properties of two olive cultivars differing in tolerance to salinity. Plant Soil 1997, 197, 87-93. [CrossRef]

- Rossi, L.; Francini, A.; Minnocci, A.; Sebastini, L. Salt stress modifies apoplastic barriers in olive (Olea europaea L.): A comparison between a salt-tolerant and a salt-sensitive cultivar. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 192, 38-46. [CrossRef]

- Rossi, L.; Borghi, M.; Francini, A.; Lin, X.; Xie, D.Y.; Sebastiani, L. Salt stress induces differential regulation of the phenylpropanoid pathway in Olea europaea cultivars Frantoio (salt-tolerant) and Leccino (salt-sensitive). J. Plant Physiol. 2016, 204, 8–15. [CrossRef]

- Sodini, M.; Francini, A.; Sebastini, L. Early salinity response in root of salt sensitive Olea europaea L. cv Leccino. Plant Stress 2023, 10, 100264. [CrossRef]

- Tester, M.; Davemport, R. Na+ tolerance and Na+ transport in higher plants. Ann. Bot. 2003, 91, 503-527. [CrossRef]

- Hayat, S.; Hayat, Q._; Alyemeni, M. N.; Wani, A. S.; Pichtel, J.; Ahmad, A. Role of proline under changing environments: A review. Plant Signal. Behav. 2012, 7, 1456–1466. [CrossRef]

- Ben Abdallah, M.; Trupiano, D.; Polzella, A.; De Zio, E.; Sassi, M.; Scaloni, A.; Zarrouk, M.; Youssef, N.B., Scippa, G.S. Unraveling physiological, biochemical and molecular mechanisms involved in olive (Olea europaea L. cv. Chétoui) tolerance to drought and salt stresses. J. Plant Physiol. 2018, 220, 83-95. [CrossRef]

- Munns, R.; Passioura, J.B.; Colmer, T.D.; Byrt, C.S. Osmotic adjustment and energy limitations to plant growth in saline soil. New Phytol. 2020, 225, 1091–1096. [CrossRef]

- Ben Rouina, B., Ben Ahmed, C., Athar, H.R., Boukhris, M. Water relations, proline accumulation and photosynthetic activity in olive tree (Olea europaea L. cv. Chemlali) in response to salt stress. Pak. J. Bot. 2006, 38, 1397–1406. https://www.webofscience.com/wos/alldb/full-record/WOS:000203707400007.

- Ben Ahmed, C.; Ben Rouina, B.; Boukhris, M. Comparative responses of three Tunisian olive cultivars to salt stress: From physiology to management practice. In: Agricultural Irrigation Research Progress; Alonso, D., Iglesias, H.J. Eds.; Nova Science Publishers: New York, USA; 2008; pp. 109–129.

- Ben Ahmed, C.; Ben Rouina, B.; Boukhris, M. Changes in water relations, photosynthetic activity and proline accumulation in one-year-old olive trees (Olea europaea L. cv. Chemlali) in response to NaCl salinity. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2008, 154, 553–560. [CrossRef]

- Ben Ahmed, C.; Ben Rouina, B.; Sensoy, S.; Boukhris, M.; Abdallah, F.B. Changes in gas exchange, proline accumulation and antioxidative enzyme activities in three olive cultivars under contrasting water availability regimes. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2009, 67, 345–352. [CrossRef]

- Sofo, A.; Dichio, B.; Xiloyannis, C.; Masia, A. Lipoxygenase activity and proline accumulation in leaves and roots of olive tree in response to drought stress. Physiol. Plant. 2004, 121, 58–65. [CrossRef]

- Ayala-Astorga, G.I.; Alcaraz-Meléndez, L. Salinity effects on protein content, lipid peroxidation, pigments, and proline in Paulownia imperialis (Siebold & Zuccarini) and Paulownia fortunei (Seemann & Hemsley) grown in vitro. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2010, 13,13-14. [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Zhang, L.; Natarajan, S.K.; Becker, D.F. Proline mechanisms of stress survival. Redox Signal. 2013, 19, 998-1011. [CrossRef]

- Goel, P.; Singh, A.K. Abiotic stresses downregulate key genes involved in nitrogen uptake and assimilation in Brassica juncea L. PLoS ONE 2015. 10, e0143645. [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Singh, V.P.; Prasad, S.M. Nitrogen modifies NaCl toxicity in eggplant seedlings: Assessment of chlorophyll a fluorescence, antioxidative response and proline metabolism. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2016, 7, 76-86. [CrossRef]

- Szabados, L.; Savouré, A. Proline: A multifunctional amino acid. Trends Plant Sci. 2010, 15, 89-97. [CrossRef]

- Tattini, M.; Gucci, R.; Romani, A.; Baldi, A.; Everard, J.D. Changes in non-structural carbohydrates in olive (Olea europaea L.) leaves during root zone salinity stress. Physiol. Plant. 1996, 98, 117–124. [CrossRef]

- Roussos, P.A.; Assimakopoulou, A.; Nikoloudi, A.; Salmas, I.; Nifakos, K.; Kalogeropoulos, P.; Kostelenos, G. Intra- and inter-cultivar impacts of salinity stress on leaf photosynthetic performance, carbohydrates and nutrient content of nine indigenous Greek olive cultivars. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2017, 39, 136. [CrossRef]

- Gucci, R.; Lombardini, L.; Tattini, M. Analysis of leaf water relations in leaves of two olive cultivars (Olea europaea) differing in tolerance to salinity. Tree Physiol. 1997, 17, 13-21. [CrossRef]

- Chartzoulakis, K.; Psarras, G.; Vemmos, S.; Loupassaki, M.; Bertaki, M. Response of two olive cultivars to salt stress and potassium supplement. J. Plant Nutr. 2006, 29, 2063-2078. [CrossRef]

- Roussos, P.A.; Gasparatos, D.; Kechrologou, K.; Katsenos, P.; Bouchagier, P. Impact of organic fertilization on soil properties, plant physiology and yield in two newly planted olive (Olea europaea L.) cultivars under Mediterranean conditions. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 220, 11-19. [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.S.; Tuteja, N. Polyamines and abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Plant Signal. Behav. 2010, 5, 26–33. [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.S.; Tuteja, N. Reactive oxygen species and anti-oxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48, 909–930. [CrossRef]

- Kaya, C.; Sonmez, O.; Aydemir, S.; Ashraf, M.; Dikilitas, M. Exogenous application of mannitol and thiourea regulates plant growth and oxidative stress responses in salt-stressed maize (Zea mays L.). J. Plant Interact. 2013, 8, 234–241. [CrossRef]

- Das, K.; Roychoudhury, A. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and response antioxidant as ROS-scavengers during environmental stress in plants. Front. Environ. Sci. 2014, 2, 53. [CrossRef]

- Goreta, S.; Bučević-Popović, V.; Pavela-Vrančić, M.; Perica, S. Salinity-induced changes in growth, superoxide dismutase activity, and ion content of two olive cultivars. J. Plant Nutr. 2007, 170, 398-403. [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Wang, X.; Ma, B.; Du, C.; Zheng, L.; Wang, Y. Expression of a Na+/H+ antiporter Rtnhx1 from a recreto-halophyte Reaumuria Trigyna improved salt tolerance of transgenic Arabidopsis Thaliana. J. Plant Physiol. 2017, 218, 109–120. [CrossRef]

- Azimi, M.; Khoshzaman, T.; Taheri, M.; Dadras, A. Evaluation of salinity tolerance of three olive (Olea europaea L.) cultivars. J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 2021, 22, 571–581. [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, C. The olive tree (Olea europaea L.) and salt stress. Importance of growth regulators. University of Jaén (Spain), 2015. https://www.educacion.gob.es/teseo/mostrarRef.do?ref=1273335.

- Gholami, R.; Hashempour, A.; Hoveized, N.F.; Zahedi, S.M. Evaluation of salinity tolerance between six young potted elite olive cultivars using morphological and physiological characteristics. Appl. Fruit Sci. 2024, 66, 163-171. [CrossRef]

- Navarro, J.M.; Pérez-Tornero, O.; Morte, A. Alleviation of salt stress in citrus seedlings inoculated with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi depends on the rootstock salt tolerance. J. Plant Physiol. 2014. 171, 76–85. [CrossRef]

- Therios, I.N.; Misopolinos, N.D. Genotypic response to sodium chloride salinity of four major olive cultivars (Olea europea L.). Plant Soil 1988. 106, 105–111. [CrossRef]

- Bazakos, C.; Manioudaki, M.E.; Therios, I.; Voyiatzis, D.; Kafetzopoulos, D.; Awada, Kalaitzis, P. Comparative transcriptome analysis of two olive cultivars in response to NaCl-stress. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42931. [CrossRef]

- Karimi, H.R.; Hasanpour, Z. Effects of salinity and waters on growth and macro nutrients concentration of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.). J. Plant Nutr. 2012, 37, 1937-1951. [CrossRef]

- Poury, N.; Seifi, E.; Alizadeh, M. The effect of proline and salt stress on growth characteristics of three olive cultivars at three different stages of the growing season. J.Chem. Health Risks. 2019, 9, 133-147. [CrossRef]

- Tattini, M.; Bertoni, P.; Caselli, S. Genotypic responses of olive plants to sodium chloride. J. Plant Nutr. 1992. 15, 1467–1485. [CrossRef]

- Klein, I.; Ben-Tal, Y.; Lavee, S.; de Malach, Y.; David, I. Saline irrigation of cv. Manzanillo and Uovo di Piccione trees. Acta Hort. 1994, 356, 176-180.

- Rewald, B.; Leuschner, C.; Wiesman, Z.; Ephrath, J. Influence of salinity on root hydraulic properties of three olive varieties. Plant Biosyst. 2011, 145, 12–22. [CrossRef]

- Rewald, B.; Rachmilevitch, S.; Ephrath, J. Salt stress effects on root systems of two mature olive cultivars. Acta Hortic. 2011, 888, 109–118. [CrossRef]

- Rewald, B.; Shelef, O.; Ephrath, J.E.; Rachmilevitch, S. Adaptive plasticity of salts-tressed root systems. In Ecophysiology and Responses of Plants Under Salt Stress; Ahmad, P., Azooz, M.M., Prasad, M.N.V. Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2013; pp. 169–201.

- Schreiber, L.; Hartmann, K.; Skrabs, M.; Zeier, J. Apoplastic barriers in roots: Chemical composition of endodermal and hypodermal cell walls. J. Exp. Bot. 1999, 50, 1267–1280. [CrossRef]

- Stoláriková, M.; Vaculík, M.; Lux, A.; Di Baccio D.; Minnocci, A.; Andreucci, A.; Sebastiani, L. Anatomical differences of poplar (Populus × euramericana clone I-214) roots exposed to zinc excess. Biologia 2012, 67, 483–489. [CrossRef]

- Vigo, C.; Therios, I.N.; Bosabalidis, A.M. Plant growth, nutrient concentration, and leaf anatomy of olive plants irrigated with diluted seawater. J. Plant Nutr. 2005, 28, 1001–11021. [CrossRef]

- Melgar, J.C.; Syvertsen, J.P.; Martínez, V.; García-Sánchez, F. Leaf gas exchange, water relations, nutrient content and growth in citrus and olive seedlings under salinity. Biol. Plant. 2008, 52, 385–390. [CrossRef]

- Kchaou, H.; Larbi, A.; Chaieb, M.; Sagardoy, R.; Msallem, M.; Morales, F. Genotypic differentiation in the stomatal response to salinity and contrasting photosynthetic and photoprotection responses in five olive (Olea europaea L.) cultivars. Sci. Hortic. 2013, 160, 129-138. [CrossRef]

- Fayek, M.A.; Fayed, T.A.; Emtithal, H.; El-Sayed, E.; El-Hameed, A. Comparative impacts of salt stress on survival and leaf anatomy traits in olive genotypes. Biosci. Res. 2018, 15, 565-574. https://www.webofscience.com/wos/alldb/full-record/WOS:000441155500002.

- Saidana Naija, D.; Ben Mansour Gueddes, S.; Braham, M. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Na. 2021, 49, 12157. [CrossRef]

- Barba-Espín, G.; Clemente-Moreno, M.J.; Álvarez, S.; García-Legaz, M.F.; Hernandez, J.A.; Diaz-Vivancos, P. Salicylic acid negatively affects the response to salt stress in pea plants. Plant Biol. 2011, 13, 909–917. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, B.; Huang, B. Mechanism of salinity tolerance in plants: Physiological, biochemical, and molecular characterization. Int. J. Genom. 2014, 2014, 701596. [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Motos, J.R.; Ortuño, M.F.; Bernal-Vicente, A.; Díaz-Vivancos, P.; Sánchez-Blanco, M.J.; Hernández, J.A. Plant responses to salt stress: Adaptative mechanisms. Agronomy 2017, 7, 18. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H. Plant salt tolerance and Na+ sensing and transport. Crop J. 2018, 6, 215–225. [CrossRef]

- Tattini, M.; Gucci, R.; Coradeschi, M.A.; Ponzio, C.; Everarard, J.D. Growth, gas exchange and ion content in Olea europaea plants during salinity and subsequent relief. Physiol. Plant. 1995, 95, 203–210. [CrossRef]

- Bacelar, E.A.; Santos, D.L.; Moutinho-Pereira, J.M.; Lopes, J.I.; Gonçalvez, C.; Ferreira, T.C.; Corrira, C.M. Physiological behaviour, oxidative damage and antioxidative protection of olive trees grown under different irrigation regimes. Plant Soil 2007, 292, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Proietti, P.;Nasini, L.; Del Buono, D.; D’Amato, R.; Tedeschini, E.; Businelli, D. Selenium protects olive (Olea europaea L.) from drought stress. Sci. Hortic. 2013, 164, 165–171. [CrossRef]

- Del Buono, D.; Regni, L.; Del Pino, A.M.; Bartucca, M.L.; Palmerini, C.A.; Proietti, P. Effects of megafol on the olive cultivar ‘Arbequina’ grown under serve saline stress in terms of physiological traits, oxidative stress, antioxidant defenses, and cytosolic Ca2+. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 11, 603576. [CrossRef]

- Skodra, C.; Michailidis, M.; Dasenaki, M.; Ganopoulos, I.; Thomaidis, N.S.; Tanou, G.; Molassiotis, A. Unraveling salt-responsive tissue-specific metabolic pathways in olive tree. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 173, 13565. [CrossRef]

- Centritto, M.; Loreto, F.; Chartzoulakis, K. The use of low [CO2] to estimate diffusional and non-diffusional limitations of photosynthetic capacity of salt-stressed olive saplings. Plant Cell Environ. 2003, 26, 585-594. [CrossRef]

- Tabatabaei, S.J. Salinity Stress and Olive: An Overview. Plant Stress 2007, 1, 105–112.

- Iqbal, M.; Ashraf, M. Gibberellic acid mediated induction of salt tolerance in wheat plants: Growth, ionic partitioning, photosynthesis, yield and hormonal homeostasis. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2013, 86, 76-85. [CrossRef]

- Tattini, M.; Traversi, M.L. On the mechanism of salt tolerance in olive (Olea europaea L.) under low- or high-Ca2+ supply. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2009, 65, 72-81. [CrossRef]

- Ben Ahmed, C.; Ben Rouina, B.; Sensoy, S.; Boukhriss, M.; Ben Abdullah, F. Exogenous proline effects on Photosynthetic performance and antioxidant defense system of young olive tree. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 4216-4222. [CrossRef]

- Bongi, G.; Loreto, F. Gas-exchange properties of salt stressed olive (Olea europea L.) leaves. Plant Physiol. 1989. 90, 1408–1416. [CrossRef]

- Loreto, F.; Centritto, M.; Chartzoulakis, K. Photosynthetic limitations in olive cultivars with different sensitivity to salt stress. Plant Cell Environ. 2003, 26, 595–601. [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Ma, X.; Wan, P.; Liu, L. Plant salt-tolerance mechanism: A review. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 495, 286-291. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S. K.; and Reddy, K. R. Regulation of photosynthesis, fluorescence, stomatal conductance and water-use efficiency of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata [L.] Walp.) under drought. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2011, 105, 40–50. [CrossRef]

- Proietti, P.; Nasini, L.; Ilarioni, L. Photosynthetic behavior of Spanish arbequina and Italian Maurino olive (Olea europaea L.) cultivars under superintensive grove conditions. Photosynthetica 2012, 50, 239–246. [CrossRef]

- Yamane, K.; Mitsuya, S.; Taniguchi, M.; Miyake, H. Salt-induced chloroplast protrusion is the process of exclusion of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/ oxygenase from chloroplasts into cytoplasm in leaves of rice. Plant Cell Environ. 2012, 35, 1663-1671. [CrossRef]

- Munns, R.; James, R.A.; Lauchli, A. Approaches to increasing the salt tolerance of wheat and other cereals. J. Exp. Bot. 2006, 57, 1025–1043. [CrossRef]

- Kaouther, Z.; Mariem, B.F.; Fardaous, M.; Cherif, H. Impact of salt stress (NaCl) on growth, chlorophyll content and fluorescence of Tunisian cultivars of chili pepper (Capsicum frutescens L.). J. Stress Physiol. Biochem. 2012, 8, 236–252.

- Morales, F.; Abadía, A.; Abadía, J. 2006. Photoinhibition and photoprotection under nutrient deficiencies, drought and salinity. In: Photoprotection. Photoinhibition, Gene Regulation,and Environment. Demmig-Adams, B., Adams III, W.W., Mattoo, A.K., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 65-85.

- Shaheen, M.A.; Hegazi, A.A.; Hmmam, I.S.A. Effect of salinity treatments on vegetative characteristics and leaves chemical content of transplants of five olive cultivars. J. Horticult. Sci. Ornament. Plants. 2011, 3, 143–151.

- Yasar, F.; Ellialtioglu, S.; Yildiz, K. Effect of salt stress on antioxidant defense systems, lipid peroxidation, and chlorophyll content in green bean. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2008, 55, 782–786. [CrossRef]

- Saha, P.;Chatterjee, P.; Biswas, A. K. NaCl pretreatment alleviates salt stress by enhancement of antioxidant defense system and osmolyte accumulation in mungbean (Vigna radiata L. Wilczek). Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2010, 48, 593–600. https://www.webofscience.com/wos/alldb/full-record/WOS:000278586800011.

- Din, J.; Khan, S.U.; Ali, I.; Gurmani, A. R. Physiological and agronomic response of canola varieties to drought stress. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2011, 21, 78–82. https://www.webofscience.com/wos/alldb/full-record/WOS:000288250800016.

- Arjenaki, F. G.; Jabbari, R.; Morshedi, A. Evaluation of drought stress on relative water content, chlorophyll content and mineral elements of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) varieties. Int. J. Agric. Crop Sci. 2012, 4, 726–729.

- Sevengor, S.; Yasar, F.; Kusvuran, S.; Ellialtioglu, S. The effect of salt stress on growth, chlorophyll content, lipid peroxidation and antioxidative enzymes of pumpkin seedling. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2011, 6, 4920–4924. [CrossRef]

- Keshavkant, S.; Padhan, J.; Parkhey, S.; Naithani, S. C. Physiological and antioxidant responses of germinating Cicer arietinum seeds to salt stress. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2012, 59, 206–211. [CrossRef]

- Demming-Adams, B.; Adams III, W.W. Photoprotection and other responses of plants to high light stress. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 1992, 43, 599–626. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, S.; Badger, M.R. Photo protection in plants: A new light on photosystem II damage. Trends Plant Sci. 2011, 16, 53–60. [CrossRef]

- García-Plazaola, J.I.; Esteban, R., Fernández-Marín, B.; Kranner, I.; Porcar-Castell, A. Thermal energy dissipation and xanthophyll cycles beyond the Arabidopsis model. Photosynth. Res. 2012, 113, 89–103. [CrossRef]

- Syvertsen, J.P.; Melgar, J.C.; García-Sánchez, F. Salinity Tolerance and Leaf Water Use Efficiency in Citrus. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2010, 135, 33–39. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Hou, X.; Bertin, N.; Ding, R.; Du, T. Quantitative Responses of Tomato Yield, Fruit Quality and Water Use Efficiency to Soil Salinity under Different Water Regimes in Northwest China. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 277, 108134. [CrossRef]

- Larsen, F.S.; Higgins Wir, A. Diurnal water relations of apple, apricot, grape, olive and peach in an arid environment. Sci. Hortic. 1989, 39, 211–222. [CrossRef]

- Rhızopoulou, S.; Meletiou-Christou, M.S.; Diamandoglou, S. Water relations for sun and shade leaves of four Mediterranean evergreen sclerophytes. J. Exp. Bot. 1991, 42, 627–635. [CrossRef]

- Dichio, B.; Xiloyannis, C.; Angelopoulos, K.; Nuzzo, V.; Bufo, S.A.; Celano, G. Drought-induced variations of water relations parameters in Olea europea. Plant Soil 2003, 257, 381–389. [CrossRef]

- Vitagliano, C.; Sebastiani, L. Physiological and biochemical remarks on environmental stress in olive (Olea europaea L.). Acta Hortic. 2002, 586, 435–440. [CrossRef]

- Larbi, A.; Kchaou, H.; Gaaliche, B.; Gargouri, K.; Boulal, H.K.; Morales, F. Supplementary potassium and calcium improves salt tolerance in olive plants. Sci. Hortic.2020, 260, 108912. [CrossRef]

- Loupassaki, M.H.; Chartzoulakis, K.S.; Digalaki, N.B.; Androulakis, I.I. Effects of salt stress on concentration of nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium, and sodium in leaves, shoots, and roots of six olive cultivars. J. Plant Nutr. 2002, 25, 2457-2482. [CrossRef]

- Tattini, M.; Traversi, M.L. Responses to changes in Ca2+ supply in two Mediterranean evergreens, Phillyrea latifolia and Pistacia lentiscus, during salinity stress and subsequent relief. Ann. Bot. 2008, 102, 609-622. [CrossRef]

- Rus, A.; Yokoi, S.; Sharkhuu, A.; Reddy, M.; Lee, B.H.; Matsumoto, T.K et al. AtHKT1 is a salt tolerance determinant that controls Na+ entry into plant roots. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences, 2001, 98, 14150-14155. [CrossRef]

- Slama, F. Intervention des racines dans le sensibilite ou tolerance a NaCl des plantes cultivees. Agronomie 1986, 6, 651–658.

- Ismail, H.; Maksimović, J.D.; Maksimović, V.; Shabala, L.; Živanović, B.D.; Tian, Y. et al. Rutin, a flavonoid with antioxidant activity, improves plant salinity tolerance by regulating K+ retention and Na+ exclusion from leaf mesophyll in quinoa and broad beans. Functional Plant Biology, 2015, 43, 75-86. [CrossRef]

- El-Shafey, N.M.; AbdElgawad, H. Luteolin, a bioactive flavone compound extracted from Cichorium endivia L. subsp. divaricatum alleviates the harmful effect of salinity on maize. Acta Physiol. Plant, 2012, 34, 2165-2177. [CrossRef]

- Parvin, K.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Bhuyan, M.B.; Mohsin, S.M.; Fujita, M. Quercetin mediated salt tolerance in tomato through the enhancement of plant antioxidant defense and glyoxalase systems. Plants, 2019, 8, 247. [CrossRef]

- Shenker, M.; Ben-Gal, A.; Shani, U. Sweet corn response to combined nitrogen and salinity environmental stresses. Plant soil, 2003, 256, 139-147. [CrossRef]

- Greenway, H.; Munns, R. Mechanisms of salt tolerance in nonhalophytes. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol, 1980, 31, 149-190. [CrossRef]

- Grattan, S.R.; Grieve, C.M.. Salinity–mineral nutrient relations in horticultural crops. Sci Hortic, 1998, 78, 127-157.

- Giorio, P.; Sorrentino, G.; d’Andria, R. Stomatal behaviour, leaf water status and photosynthetic response in field-grown olive trees under water deficit. Environ. Exp. Bot. 1999, 42, 95-104. [CrossRef]

- Chaves, M.M.; Flexas, J.; Pinheiro, C. Photosynthesis under drought and salt stress: Regulation mechanisms from whole plant to cell. Ann. Bot. 2009, 103, 551-560. [CrossRef]

- Boughalleb, F.; Mhamdi, M. Possible involvement of proline and the antioxidant defense systems in the drought tolerance of three olive cultivars grown under increasing water deficit regimes. Agric. J. 2011, 6, 378-391.

- Pierantozzi, P.; Torres, M.; Bodoira, R.; Maestri, D. Water relations, biochemical–physiological and yield responses of olive trees (Olea europaea L. cvs. Arbequina and Manzanilla) under drought stress during the pre-flowering and flowering period. Agric. Water Manag. 2013, 125, 13-25. [CrossRef]

- Trabelsi, L.; Gargouri, K.; Ghrab, M.; Mbadra, C.; Hassena, A.B.; Ncube, B. et al. (2024). The effect of drought and saline water on the nutritional behaviour of the olive tree (Olea europaea L.) in an arid climate. S. Afr. J. Bo., 2024, 165, 126-135. [CrossRef]

- Boualem, S.; Boutaleb, F.; Ababou, A.; Gacem, F. Effect of salinity on the physiological behavior of the olive tree (variety sigoise). J. Fundam. Appl. Sci. 2019, 11, 525-538. [CrossRef]

- Demiral, M.A.; Uygun, D.A.; Uygun, M.; Kasirğa, E.; Karagözler, A.A. Biochemical response of Olea europaea cv. Gemlik to short-term salt stress. Turk. J. Biol. 2011, 35, 433-442. [CrossRef]

- Ben Ahmed, C.; Ben Rouina, B.; Sensoy, S., Boukhriss, M.; Abdullah, F.B. Saline water irrigation effects on antioxidant defense system and proline accumulation in leaves and roots of field-grown olive. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 11484-11490. [CrossRef]

- Regni, L.; Del Pino, A.M.; Mousavi, S.; Palmerini, C.A.; Baldoni, L.; Mariotti, R.; et al. Physiological and biochemical traits of different olive tree cultivars during salt stress. In IX International Symposium on Irrigation of Horticultural Crops 2019, 1335, 171-178. [CrossRef]

- Ikbal, F.E.; Hernández, J.A.; Barba-Espín, G.; Koussa, T.; Aziz, A.; Faize, M.; Diaz-Vivancos, P. (2014). Enhanced salt-induced antioxidative responses involve a contribution of polyamine biosynthesis in grapevine plants. J. Plant Physiol. 2014, 171, 779-788. [CrossRef]

- Cardi, M.; Castiglia, D.; Ferrara, M.; Guerriero, G.; Chiurazzi, M.; Esposito, S. The effects of salt stress cause a diversion of basal metabolism in barley roots: Possible different roles for glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase isoforms. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 86, 44–54. [CrossRef]

- Ramanjulu, S.; Sudhakar, C. Proline metabolism during dehydration in two mulberry genotypes with contrasting drought tolerance. J. Plant Physiol. 2000, 157, 81-85. [CrossRef]

- De Lacerda, C.F.; Cambraia, J.; Oliva, M.A.; et al. Solute accumulation and distribution during shoot and leaf development in two sorghum genotypes under salt stress. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2003, 49, 107-120. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Cuin, T.A.; Zhou, M.; Twomey, A.; Naidu, B.P.; Shabala, S. Compatible solute accumulation and stress-mitigating effects in barley genotypes contrasting in their salt tolerance. J. Exp. Bot. 2007, 58, 4245-4255. [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, P.M.; Bressan, R.A.; Zhu, J.K.; Bohnert, H.J. Plant cellular and molecular responses to high salinity. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2000, 51, 463-499. [CrossRef]

- Khatkar, D.; Kuhad, M.S. Short-term salinity induced changes in two wheat cultivars at different growth stages. Biol. Plant. 2000, 43, 629-632. [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.; Foolad, M.R. Improving plant abiotic-stress resistance by exogenous application of osmoprotectants glycine betaine and proline. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2007, 59, 206-216. [CrossRef]

- Gholami, R.; Fahadi Hoveizeh, N.; Zahedi, S.M.; Gholami, H.; Carillo, P. Effect of three water-regimes on morpho-physiological, biochemical and yield responses of local and foreign olive cultivars under field conditions. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 477. [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, S.M.; Hosseini, M.S.; Meybodi, N.D.H.; Abadía, J.; Germ, M.; Gholami, R.; Abdelrahman, M. Evaluation of drought tolerance in three commercial pomegranate cultivars using photosynthetic pigments, yield parameters and biochemical traits as biomarkers. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 261, 107357. [CrossRef]

- Ben Hassine, A.; Ghanem, M.E.; Bouzid, S.; Lutts, S. An inland and a coastal population of the Mediterranean xero-halophyte species Atriplex halimus L. differ in their ability to accumulate proline and glycinebetaine in response to salinity and water stress. J. Exp. Bot. 2008, 59, 1315-1326. [CrossRef]

- Ben Ahmed, C.; Magdich, S.; Rouina, B.B.; Boukhris, M.; Abdullah, F.B. Saline water irrigation effects on soil salinity distribution and some physiological responses of field grown Chemlali olive. J. Environ. Manage. 2012, 113, 538-544. [CrossRef]

- Van den Ende, W.; Valluru, R. Sucrose, sucrosyl oligosaccharides, and oxidative stress: Scavenging and salvaging?. J. Exp. Bot. 2009, 60, 9-18. [CrossRef]

- Trabelsi, L.; Gargouri, K.; Hassena, A.B.; Mbadra, C.; Ghrab, M.; Ncube, B.; et al.. Impact of drought and salinity on olive water status and physiological performance in an arid climate. Agric. Water Manag. 2019; 213, 749-759. [CrossRef]

- Gargouri, K.; Influence of Soil Fertility on Olive (Olea europaea L.) Tree Nutritional Status and Production Under Arid Climates. Doctoral Thesis in Arboriculture, Universita Degli Studi Di Palermo, Italy. 2007.

- Ben Hassena, A.; Zouari, M.; Trabelsi, L.; Decou, R.; Amar, F.B.; Chaari, A.; et al. Potential effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in mitigating the salinity of treated wastewater in young olive plants (Olea europaea L. cv. Chetoui). Agric. Water Manage. 2021, 245, 106635. [CrossRef]

- Annabi, K.; Laaribi, I.; Gouta, H.; Laabidi, F.; Mechri, B.; Ajmi, L.; et al. Protein content, antioxidant activity, carbohydrates and photosynthesis in leaves of girdled stems of four olive cultivars. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 256, 108551. [CrossRef]

- Lama-Muñoz, A.; del Mar Contreras, M.; Espínola, F.; Moya, M.; Romero, I.; Castro, E. Characterization of the lignocellulosic and sugars composition of different olive leaves cultivars. Food Chem. 2000, 329, 127153. [CrossRef]

- Conde, A.; Silva, P.; Agasse, A.; Conde, C.; Gerós, H. Mannitol transport and mannitol dehydrogenase activities are coordinated in Olea europaea under salt and osmotic stresses. Plant Cell Physiol., 2011, 52, 1766-1775. [CrossRef]

- Žuna Pfeiffer, T.; Štolfa, I.; Hoško, M.; Žanić, M.; Pavičić, N.; Cesar, V.; Lepeduš, H. Comparative study of leaf anatomy and certain biochemical traits in two olive cultivars. Agric. Conspec. Sci. 2020, 75, 91-97.

- Barceló, A.R. Lignification in plant cell walls. Int. Rev. Cytol. 1997, 176, 87-132. [CrossRef]

- Espartero, J.; Pintor-Toro, J.A.; Pardo, J.M. Differential accumulation of S-adenosylmethionine synthetase transcripts in response to salt stress. Plant Mol. Biol. 1994, 25, 217-227. [CrossRef]

- Quiroga, M.; Guerrero, C.; Botella, M.A.; Barceló, A.; Amaya, I.; Medina, M.I.; et al. A tomato peroxidase involved in the synthesis of lignin and suberin. Plant Physiol. 2000, 122, 1119-1128. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Aguayo, I.; Rodríguez-Galán, J.M.; García, R.; Torreblanca, J.; Pardo, J.M. Salt stress enhances xylem development and expression of S-adenosyl-L-methionine synthase in lignifying tissues of tomato plants. Planta. 2004, 220, 278-285. [CrossRef]

- Ben Nja, R. Effet d’un stress salin sur la teneur en polymères pariétaux dans les feuilles de luzerne (Medicago sativacv Gabès) et sur la distribution dans les cellules de transfert des fines nervures. Doctoral dissertation, Faculté des Sciences et Techniques, Université de Limoges, France, 2014.

- Niederberger, V.; Purohit, A.; Oster, J.P.; Spitzauer, S.; Valenta, R.; Pauli, G. The allergen profile of ash (Fraxinus excelsior) pollen: Cross-reactivity with allergens from various plant species. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 2002, 32, 933-941. [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.H.; Cho, E.J.; Wi, S.G.; Bae, H.; Kim, J.E.; Cho, J.Y.; et al. Divergences in morphological changes and antioxidant responses in salt-tolerant and salt-sensitive rice seedlings after salt stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2013, 70, 325-335. [CrossRef]

- Mimmo, T.; Bartucca, M.L.; Del Buono, D.; Cesco, S. Italian ryegrass for the phytoremediation of solutions polluted with terbuthylazine. Chemosphere, 2015, 119, 31-36. [CrossRef]

- Del Buono, D.; Pannacci, E.; Bartucca, M.L.; Nasini, L.; Proietti, P.; Tei, F. Use of two grasses for the phytoremediation of aqueous solutions polluted with terbuthylazine. Int. J. Phytoremediation. 2016; 18, 885-891. [CrossRef]

- Bhaduri, A.M.; Fulekar, M.H. Antioxidant enzyme responses of plants to heavy metal stress. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2012, 11, 55-69. [CrossRef]

- Keunen, E.L.S.; Peshev, D.; Vangronsveld, J.; Van Den Ende, W.I.M; Cuypers, A.N.N. Plant sugars are crucial players in the oxidative challenge during abiotic stress: Extending the traditional concept. Plant Cell Environ. 2013, 36, 1242-1255. [CrossRef]

- López-Gómez, E.; San Juan, M.A.; Diaz-Vivancos, P.; Beneyto, J.M.; García-Legaz, M.F.; Hernández, J.A.. Effect of rootstocks grafting and boron on the antioxidant systems and salinity tolerance of loquat plants (Eriobotrya japonica Lindl.). Environ. Exp. Bot. 2007,60, 151-158. [CrossRef]

- Ertani, A.; Schiavon, M.; Muscolo, A.; Nardi, S. Alfalfa plant-derived biostimulant stimulate short-term growth of salt stressed Zea mays L. plants. Plant Soil, 2013, 364, 145-158. [CrossRef]

- Bano, S.; Muhammad Ashraf, M.A.; Akram, N.A.; Al-Qurainy, F. Regulation in some vital physiological attributes and antioxidative defense system in carrot (Daucus carota L.) under saline stress. J. Appl. Bot. Food Qual. Angew. Bol. 2012, 85, 105–115.

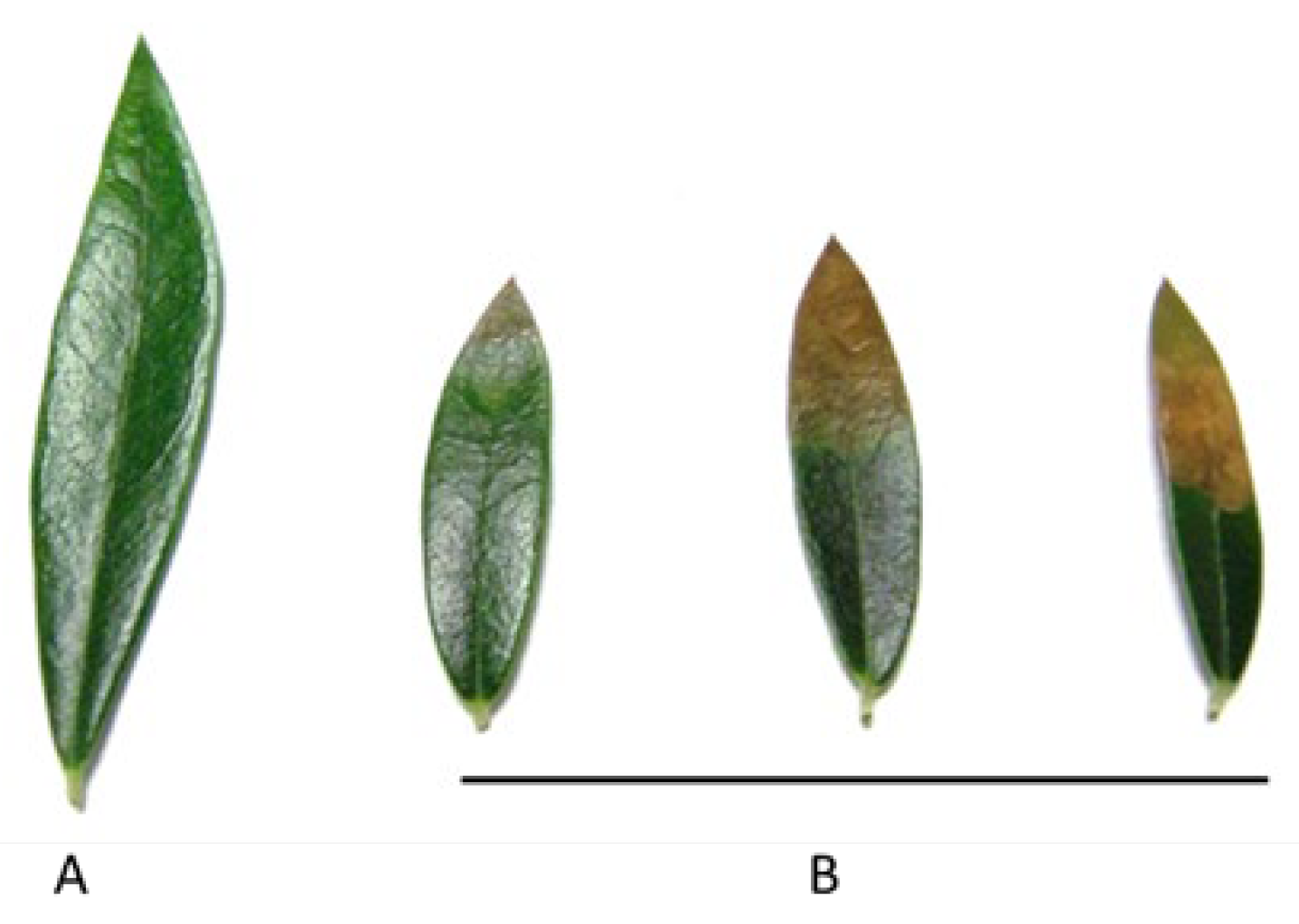

- Lima Cabello, E.; de Torres, S.; Torrellas López, E.; Medina-Correa, C.; León, I.; Bejarano, P.; et al. Resilience of olive tree cultivars to intensive salt stress. High School Students for Agricultural Science Research 2023, 12, 66-76.

- Tadić, J.; Dumičić, G.; Veršić Bratinčević, M.; Vitko, S.; Radić Brkanac, S. Physiological and biochemical response of wild olive (Olea europaea Subsp. europaea var. sylvestris) to salinity. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 712005. [CrossRef]

- Demir, S.; Cetinkaya, H. Effects of saline conditions on polyphenol and protein content and photosynthetic response of different olive (Olea europaea L.) cultivars. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2020, 18. 2599-2610. [CrossRef]

- Naczk, M.; Shahidi, F. Extraction and analysis of phenolics in food. J. Chromatogr. A 2004, 1054, 95-111. [CrossRef]

- Ranalli, A.; Contento, S.; Lucera, L.; Di Febo, M.; Marchegiani, D.; Di Fonzo, V. Factors affecting the contents of iridoid oleuropein in olive leaves (Olea europaea L.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 434-440. [CrossRef]

- Chutipaijit, S.; Cha-Um, S.; Sompornpailin, K. Differential accumulations of proline and flavonoids in indica rice varieties against salinity. Pak. J. Bot. 2009, 41, 2497-2506.

- Azariadis, A.; Vouligeas, F.; Salame, E.; Kouhen, M.; Rizou, M.; Blazakis, K.; et al. Response of Prolyl 4 Hydroxylases, Arabinogalactan Proteins and Homogalacturonans in Four Olive Cultivars under Long-Term Salinity Stress in Relation to Physiological and Morphological Changes. Cells 2023, 12, 1466. [CrossRef]

- Bashir, M.A.; Silvestri, C.; Coppa, E.; Brunori, E.; Cristofori, V.; Rugini, E. ; et al.. Response of olive shoots to salinity stress suggests the involvement of sulfur metabolism. Plants 2021, 10, 350. [CrossRef]

- Valderrama, R.; Corpas, F. J.; Carreras, A.; Fernández-Ocaña, A.; Chaki, M.; Luque, F.; et al. Nitrosative stress in plants. Febs Lett. 2007, 581, 453-461. [CrossRef]

- Parida, A.K., Das, A.B.; Mittra, B.; Mohanty, P. Salt-stress induced alterations in protein profile and protease activity in the mangrove Bruguiera parviflora. Z. Naturforsch. C. 2004, 59, 408-414. [CrossRef]

- Parida, A.K.; Das, A.B. Salt tolerance and salinity effects on plants: A review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2005, 60, 324-349. [CrossRef]

- Mansour, M.M.F. Nitrogen containing compounds and adaptation of plants to salinity stress. Biol. Plant. 2000, 43, 491-500. [CrossRef]

- Kouhen, M. Involvment of the cell wall arabinogalactan proteins in the salinity tolerance mechanism of four greek olive cultivars. Degree Master of Science, Department of Horticultural Genetics and Biotechnology CIHEAM-Mediterranean Agronomic Institute of Chania, Greece, 2019.

- Ouyang, B.; Yang, T.; Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; et al. Identification of early salt stress response genes in tomato root by suppression subtractive hybridization and microarray analysis. J. Exp. Bot. 2007, 58, 507-520. [CrossRef]

- Olmos, E.; García De La Garma, J.; Gomez-Jimenez, M. C.; Fernandez-Garcia, N. Arabinogalactan proteins are involved in salt-adaptation and vesicle trafficking in tobacco by-2 cell cultures. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 274585. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Zayed, O.; Zeng, F.; Liu, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, P.; et al. Arabinose biosynthesis is critical for salt stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2019, 224, 274-290. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, S.; Genty, B. Mapping intercellular CO2 mole fraction (C i) in Rosa rubiginosa leaves fed with abscisic acid by using chlorophyll fluorescence imaging: Significance of C i estimated from leaf gas exchange. Plant Physiol., 116, 1998, 947-957. [CrossRef]

- Seeber, F.; Aliverti, A.; Zanetti, G. The plant-type ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase/ferredoxin redox system as a possible drug target against apicomplexan human parasites. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2005, 11, 3159-3172. [CrossRef]

- Badger, M.R.; Price, G.D. The role of carbonic anhydrase in photosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 1994, 45, 369-392. [CrossRef]

- Park, S. W.; Kaimoyo, E.; Kumar, D.; Mosher, S.; Klessig, D.F. Methyl salicylate is a critical mobile signal for plant systemic acquired resistance. Science, 2007, 318, 113-116. [CrossRef]

- Rivas-San Vicente, M.; Plasencia, J. Salicylic acid beyond defence: Its role in plant growth and development. J. Exp. Bot., 2011, 62, 3321-3338. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I.R.; Fatma, M.; Per, T.S.; Anjum, N. A.; Khan, N.A. Salicylic acid-induced abiotic stress tolerance and underlying mechanisms in plants. Front Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 135066. [CrossRef]

- Cabane, M.; Afif, D.; Hawkins, S. Lignins and abiotic stresses. In Advances in botanical research. Academic Press. 2012, 61, 219-262. [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Lopez, J.C.; Kotchoni, S.O.; Hernandez-Soriano, M.C.; Gachomo, E. W.; Alché, J.D. Structural functionality, catalytic mechanism modeling and molecular allergenicity of phenylcoumaran benzylic ether reductase, an olive pollen (Ole e 12) allergen. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2013, 27, 873-895. [CrossRef]

- Castro, L.; Crespo, J.F.; Rodríguez, J.; Rodríguez, R.; Villalba, M. Immunoproteomic tools are used to identify masked allergens: Ole e 12, an allergenic isoflavone reductase from olive (Olea europaea) pollen. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Proteins Proteomics. 2015, 1854, 1871-1880. [CrossRef]

- Mansour, M.M.F.; Salama, K.H. Cellular basis of salinity tolerance in plants. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2004, 52, 113-122. [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.P.J.C.; Harris, P.J. Potential biochemical indicators of salinity tolerance in plants. Plant Sci. 2004, 166, 3-16. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.M.; Cardoso, L.A.; Santos, D.M.; Torné, J.M.; Fevereiro, P.S. Trehalose and its applications in plant biotechnology. In Vitro Cell Dev. Biol. Plant. 2007, 43, 167-177. [CrossRef]

- Said, E.M. Expression analysis of AtTPS1 gene coding for trehalose-6-phosphate synthase in salt stressed olive (Olea eurropaea L.). Biosci. Res. 2017, 14, 809-816. https://www.webofscience.com/wos/alldb/summary/3f514112-e14b-4a82-909a-1737254acf2b-e9cc0e08/relevance/1.

- Bray, E.A. Plant responses to water deficit. Trends Plant Sci. 1997, 2, 48-54. [CrossRef]

- Seki, M.; Kamei, A.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Shinozaki, K. Molecular responses to drought, salinity and frost: Common and different paths for plant protection. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2003, 14, 194-199. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Huang, Z.; Xie, B.; Chen, Q.; Tian, X.; Zhang, X.; et al. The ethylene-, jasmonate-, abscisic acid-and NaCl-responsive tomato transcription factor JERF1 modulates expression of GCC box-containing genes and salt tolerance in tobacco. Planta 2004, 220, 262-270. [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, T.; Fujita, Y.; Sayama, H.; Kidokoro, S.; Maruyama, K.; Mizoi, J.; et al. AREB1, AREB2, and ABF3 are master transcription factors that cooperatively regulate ABRE-dependent ABA signaling involved in drought stress tolerance and require ABA for full activation. Plant J. 2010, 61, 672-685. [CrossRef]

- Bazakos, C.; Manioudaki, M.E.; Sarropoulou, E.; Spano, T.; Kalaitzis, P. 454 pyrosequencing of olive (Olea europaea L.) transcriptome in response to salinity. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143000. [CrossRef]

- Mantri, N. L., Ford, R., Coram, T. E., & Pang, E. C. (2007). Transcriptional profiling of chickpea genes differentially regulated in response to high-salinity, cold and drought. BMC genomics 2007, 8, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Qing, D.J.; Lu, H.F.; Li, N.; Dong, H.T.; Dong, D. F.;Li, Y.Z. Comparative profiles of gene expression in leaves and roots of maize seedlings under conditions of salt stress and the removal of salt stress. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009, 50, 889-903. [CrossRef]

- Ehlting, J.; Provart, N.J.; Werck-Reichhart, D. Functional annotation of the Arabidopsis P450 superfamily based on large-scale co-expression analysis. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2006, 34, 1192-1198. [CrossRef]

- Gálvez, F.J.; Baghour, M.; Hao, G.; Cagnac, O.; Rodríguez-Rosales, M.P.; Venema, K. Expression of LeNHX isoforms in response to salt stress in salt sensitive and salt tolerant tomato species. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2012, 51, 109-115. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.E.; Youssef, E.A.; Kord, M.A.; Qaid, E.A. Trehalose accumulation in wheat plant promotes sucrose and starch biosynthesis. Jordan J. Biol. Sci. 2013, 6, 143-149. [CrossRef]

- Blázquez, M.A.; Santos, E.; Flores, C.L.; Martínez-Zapater, J.M.; Salinas, J.; Gancedo, C. Isolation and molecular characterization of the Arabidopsis TPS1 gene, encoding trehalose-6-phosphate synthase. Plant J. 1998, 13, 685-689. [CrossRef]

- Vogel, G.; Aeschbacher, R.A.; Müller, J.; Boller, T.; Wiemken, A. Trehalose-6-phosphate phosphatases from Arabidopsis thaliana: Identification by functional complementation of the yeast tps2 mutant. Plant J. 1998, 13, 673-683. [CrossRef]

- Leyman, B.; Van Dijck, P.;Thevelein, J.M. An unexpected plethora of trehalose biosynthesis genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Trends Plant Sci. 2001, 6, 510-513. [CrossRef]

- Penna, S. Building stress tolerance through over-producing trehalose in transgenic plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2003, 8, 355-357. [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.; Mariotti, R.; Valeri, M.C.; Regni, L.; Lilli, E.; Albertini, E.; et al. Characterization of differentially expressed genes under salt stress in olive. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 23, 154. [CrossRef]

- Reddy, P.S.; Jogeswar, G.; Rasineni, G.K.; Maheswari, M.; Reddy, A.R.; Varshney, R.K.; Kishor, P.K. Proline over-accumulation alleviates salt stress and protects photosynthetic and antioxidant enzyme activities in transgenic sorghum [Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench]. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 94, 104-113. [CrossRef]

- Guan, C.; Cui, X.; Liu, H.Y.; Li, X.; Li, M.Q.; Zhang, Y.W. Proline biosynthesis enzyme genes confer salt tolerance to switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L.) in cooperation with polyamines metabolism. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 46. [CrossRef]

- Pakzad, R.; Goharrizi, K.J.; Riahi-Madvar, A.; Amirmahani, F.; Mortazavi, M.; Esmaeeli, L. Identification of Lepidium draba Δ 1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase (P5CS) and assessment of its expression under NaCl stress: P5CS identification in L. draba plant. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. India Sect. B: Biol. Sci. 2021, 91, 195-203. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Hu, M.; Wang, Q.; Cheng, L.; Zhang, Z. Role of papain-like cysteine proteases in plant development. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1717. [CrossRef]

- Joaquín-Ramos, A.; Huerta-Ocampo, J.Á.; Barrera-Pacheco, A.; De León-Rodríguez, A.; Baginsky, S.; de la Rosa, A.P.B. Comparative proteomic analysis of amaranth mesophyll and bundle sheath chloroplasts and their adaptation to salt stress. J. Plant Physiol. 2014, 171, 1423-1435. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. J.; Ding, L.; Liu, X.H.; Liu, J.X. Two B-box domain proteins, BBX28 and BBX29, regulate flowering time at low ambient temperature in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. 2021; 106, 21-32. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, Q.; Zhou, P.; Zhang, Q.; Fang, Y. NaCl-induced changes in vacuolar H+-ATPase expression and vacuolar membrane lipid composition of two shrub willow clones differing in their response to salinity. Plant Growth Regul. 2018, 86, 445-453. [CrossRef]

- Balasubramaniam, T.; Shen, G.; Esmaeili, N.; Zhang, H. Plants’ response mechanisms to salinity stress. Plants 2023, 12, 2253. [CrossRef]

- Shabala, S.; Hariadi, Y.; Jacobsen, S.E. Genotypic difference in salinity tolerance in quinoa is determined by differential control of xylem Na+ loading and stomatal density. J. Plant Physiol. 2013, 170, 906-914. [CrossRef]

- Seidel, T. The Plant V-ATPase. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 931777. [CrossRef]

- El Yamani. M.; Sakar, E.H.; Boussakouran, A.; Rharrabti, Y. Physiological and biochemical responses of young olive trees (Olea europaea L.) to water stress during flowering. Arch. Biol. Sci. 2019, 71, 123-132. [CrossRef]

- El Yamani, M.; Sakar, E.H., Boussakouran, A.; Rharrabti, Y. Leaf water status, physiological behavior and biochemical mechanism involved in young olive plants under water deficit. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 261, 108906. [CrossRef]

- Abd El Rahman, A.; Sharkawi, M.H. Effect of salinity and water supply on olive. Plant Soil 1968, 280-290. [CrossRef]

- Gucci, R.; Tattini, M.; Lombardini, L. Meccanismi di resistenza allo stress osmosalino in olivo. In Olivicoltura mediterranea: Stato e rpospettive della coltura e della ricerca. La Grafica Commerciale. 1996, pp. 305-312.

- Sadok, W.; Lopez, J.R.; Smith, K.P. Transpiration increases under high-temperature stress: Potential mechanisms, trade-offs and prospects for crop resilience in a warming world. Plant Cell Environ. 2021, 44, 2102-2116. [CrossRef]

| Continents | Area (Mha) |

|---|---|

| Africa | 80.44 |

| America | 144.73 |

| Asia | 316.50 |

| Europe | 30.70 |

| Oceania | 357.33 |

| World | 931.70 |

| Continents | Main Cultivars |

|---|---|

| Africa | Picholine, Marroqui, Hacuzia, Meslala, Menara, Arbosana, Arbequina, Koroneiki, Woira, Mission, Kalamata |

| America | Arbequina, Azapá, Criolla, Coratina, Barouni, Manzanilla, Ascolana, Mision, Arauco, Picus |

| Asia | Arjosi, Barmagui, Basica, Kikkam, Kasb, Souri, Nabal Baladi, Mehravia, Muhasan, Mastoidis |

| Europe | Arbequina, Picual, Hojiblanca, Koroneiki, Arbosana, Alentajana, Frantoio, Verdial, Picudo, Carbonella |

| Oceania | Hardy’s, Mammoth, Fs17, Dai21, Azapa, Picual, Hojiblanca, Manzanilla, Barnea, Frantoio, Koroneiki |

| World | Arbequina, Arbosana, Koroneiki, Picual, Frantoio, Leccino, Hojiblanca, Verdial, Kalamata, Picholine, Alentajana, Nabal Baladi |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).