Submitted:

28 May 2024

Posted:

29 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. National Research Council and History of Nutrient Requirements in Sheep and Goats

3. Energy and Protein Requirements in Sheep

4. Energy and Protein Requirements in Goats

5. Macromineral Requirements in Sheep and Goats

6. Estimating Nutrient Requirements

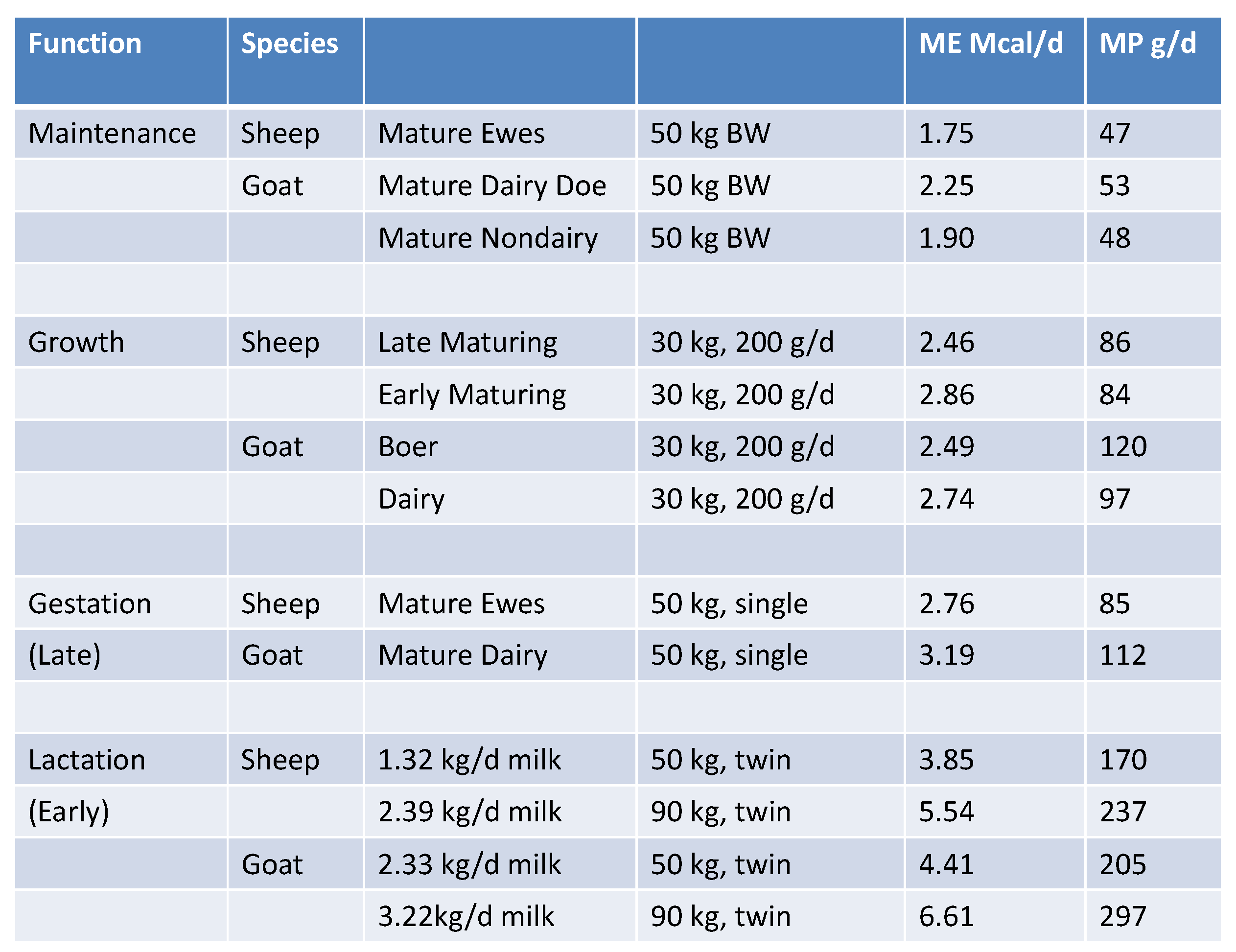

6.1. Physiological Functions and Classifications

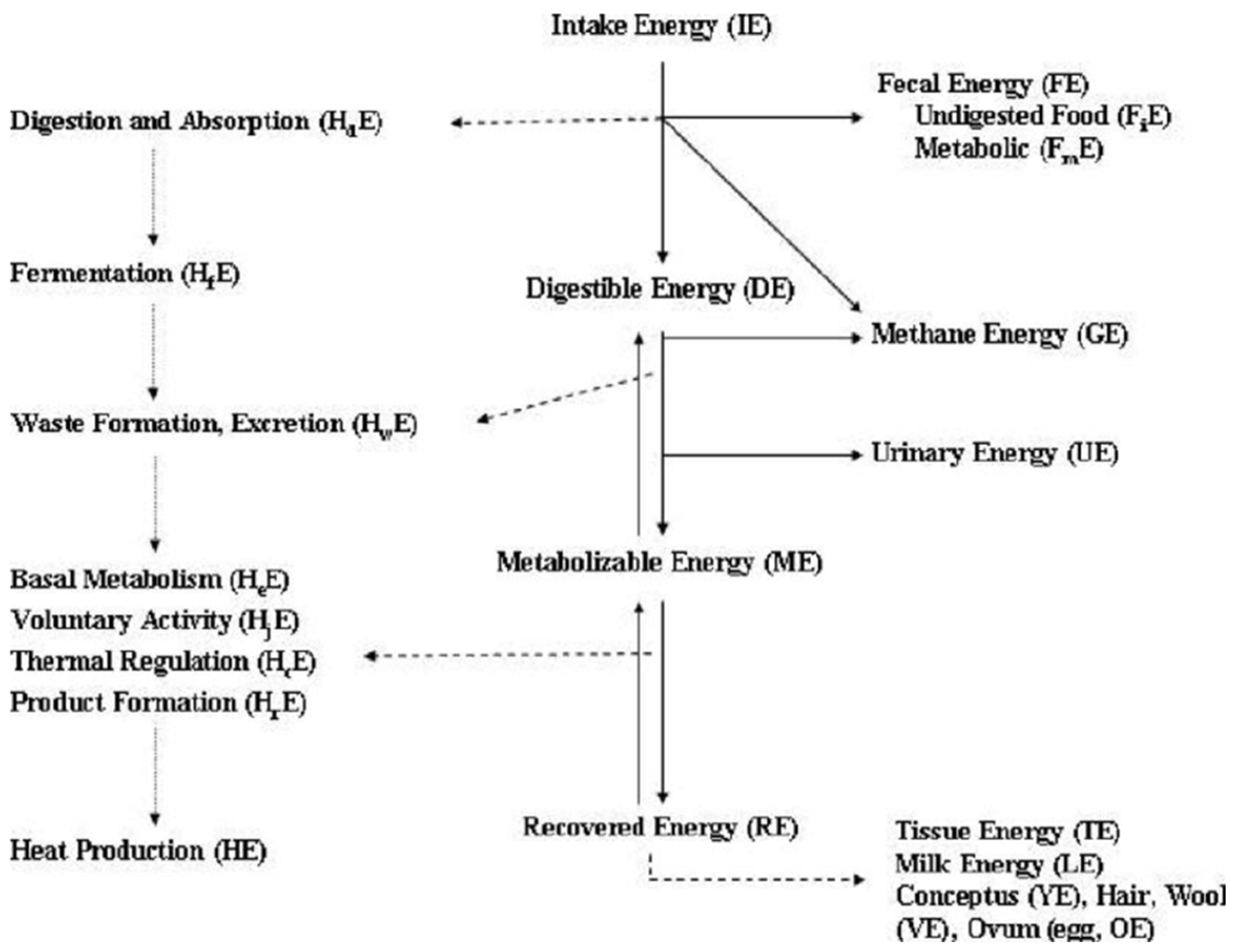

6.2. Estimating Energy Requirements

6.3. NRC Equations for Predicting Energy Requirements for Sheep and Goats

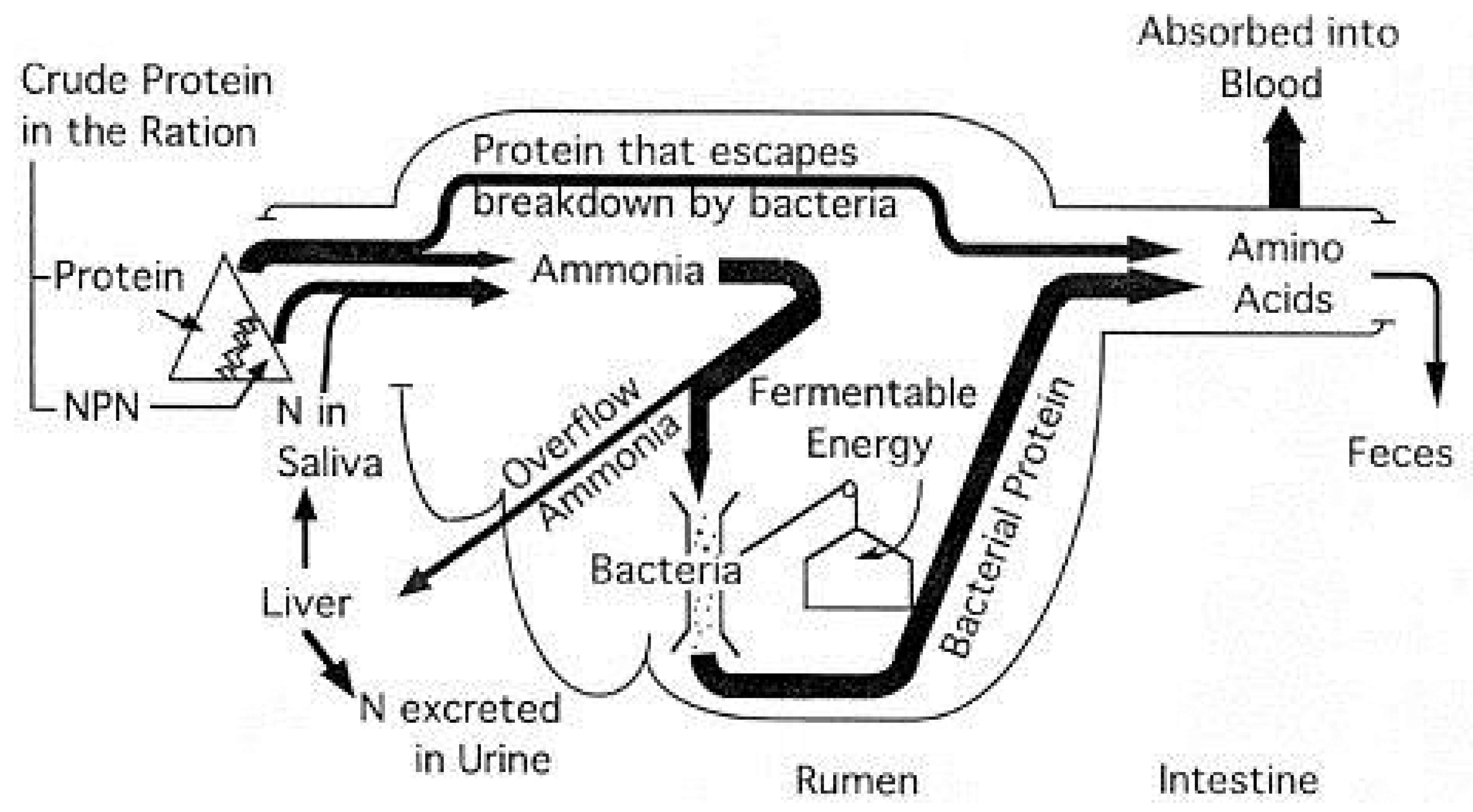

6.4. Estimating Protein Requirements

6.5. NRC Equations for Predicting Protein Requirements in Sheep and Goats

7. Limitations in Establishing Nutritional Standards

8. Nutrigenomics and Nutrient Requirements

9. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lu, C.D. The role of goats in the world: Society, science, and sustainability. Small Rumin. Res. 2023, 227, 107056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonza ́lez, L.A.; Kyriazakis, I.; Tedeschi, L.O. Review: Precision nutrition of ruminants: Approaches, challenges and potential gains. Animal 2018, 12, s246–s261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NRC (National Research Council). Nutrient Requirements of Small Ruminants: Sheep, Goats, Cervids, and New World Camelids; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, R. Nutrigenomics, individualism and public health. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2004, 63, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norheim, F.; Gjelstad, I.M.F.; Hjorth, M.; Vinknes, K.J.; Langleite, T.M.; Holen, T.; Jensen, J.; Dalen, K.T.; Karlsen, A.S.; Kielland, A.; et al. Molecular Nutrition Research—The Modern Way Of Performing Nutritional Science. Nutrients 2012, 4, 1898–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osorio, J.S.; Vailati-Ribonib, M.; Palladinoc, A.; Luo, J.; Loor, J.J. Application of nutrigenomics in small ruminants: Lactation, growth, and beyond. Small Rumin. Res. 2017, 154, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ul Haq, Z.; Saleem, A.; Khan, A.A.; Dar, M.A.; Ganaie, A.M.; Beigh, Y.A.; Hamadani, H.; Ahmad, S.M. Nutrigenomics in livestock sector and its human-animal interface-a review. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2022, 17, 100262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academic of Science. The organization of National Research Council. Retrieved on March 14, 2024 from: http://www.nasonline.org/about-nas/history/archives/milestones-in-NAS-history/organization-of-the-nrc.html.

- NRC. Recommended nutrient allowances for sheep. Recommended nutrient allowances for domestic animals. National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1945. [CrossRef]

- NRC. Recommended nutrient allowances for sheep. (1st ed.). Recommended nutrient allowances for domestic animals. National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1949. [CrossRef]

- NRC. Nutrient requirements of sheep, 2nd ed.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NRC. Nutrient requirements of sheep. Nutrient requirements of domestic animals, 3rd ed.; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- NRC. Nutrient requirements of sheep. Nutrient requirements of domestic animals, 4th ed.; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- NRC. Nutrient requirements of sheep. Nutrient requirements of domestic animals, 5th ed.; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NRC. Nutrient requirements of sheep. Nutrient requirements of domestic animals, 6th ed.; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- NRC. Nutrient Requirements of Goats: Angora, Dairy, and Meat Goats in Temperate and Tropical Countries, 1981. [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.D.; Sahlu, T.; Fernandez, J.M. Assessment of energy and protein requirements for growth and lactation in goats. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Goats, Brasilia, Brazil, 8–13 March 1987; Volume 2, pp. 1229–1248. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C.D. Energy and protein nutrition in lactating dairy goats. In Proceedings of the 24th Pacific Northwest Animal Nutrition Conference, Boise, Idaho, USA; 1989; pp. 133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C.D.; Potchoiba, M.J. Feed intake and weight gain of growing goats fed diets of various energy and protein levels. J. Anim. Sci. 1990, 68, 1751–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahlu, T.; Fernandez, J.M.; Lu, C.D.; Potchoiba, M.J. Influence of dietary protein on performance of dairy goats during pregnancy. J. Dairy Sci. 1992, 75, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahlu, T.; Fernandez, J.M.; Lu, C.D.; Manning, R. Dietary protein level and ruminal degradability for mohair production in Angora goats. J. Anim. Sci. 1992, 70, 1526–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, J.M.; Sahlu, T.; Lu, C.D.; Ivey, D.; Potchoiba, M.J. Production and metabolic aspects of nonprotein nitrogen incorporation in lactation rations of dairy goats. Small Rumin. Res. 1997, 26, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, K.; Lu, C.D. Sulfur and sulfur-containing amino acid requirements for meat, milk and mohair production in goats. In Proceeding of the 6th International Conference on Goats. Beijing, China. 1996, 2:537-548. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/307902682.

- Qi, K.; Lu, C.D.; Owens, F.N. Sulfate supplementation of Alpine goats: Effects on milk yield and composition, metabolites, nutrient digestibilities and acid-base balance. J. Anim. Sci. 1992, 70, 3551–3560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, K.; Lu, C.D.; Owens, F.N. Sulfate supplementation of Angora goats: Sulfur metabolism and interactions with zinc, copper and molybdenum. Small Rumin. Res. 1993, 11, 209–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, K.; Lu, C.D.; Owens, F.N. Sulfate supplementation of growing goats: Effects on performance, acid-base balance, and nutrient digestibilities. J. Anim. Sci. 1993, 71, 1579–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, K.; Lu, C.D.; Owens, F.N. Effects of sulfate supplementation on performance, acid-base balance, and nutrient metabolism in Alpine kids. Small Rumin. Res. 1994, 15, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, K.; Lu, C.D.; Owens, F.N.; Lupton, C.J. Sulfate supplementation of Angora goats: Metabolic and mohair responses. J. Anim. Sci. 1992, 70, 2828–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, K.; Lu, C.D.; Owens, F.N.; Lupton, C.J. Effects of sulfate supplementation on performance, acid-base balance, and nutrient metabolism in Angora kids. Small Rumin. Res. 1994, 15, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Goetsch, A.L.; Nsahlai, I.V.; Johnson, Z.B.; Sahlu, T.; Moore, J.E.; Ferrell, C.L.; Galyean, M.L.; Owens, F.N. Maintenance energy requirements of goats: Predictions based on observations of heat and recovered energy. Small Rumin. Re. 2004, 53, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Goetsch, A.L.; Sahlu, T.; Nsahlai, I.V.; Johnson, Z.B.; Moore, J.E.; Galyean, M.L.; Owens, F.N.; Ferrell, C.L. Prediction of metabolizable energy requirements for maintenance and gain of preweaning, growing and mature goats. Small Rumin. Res. 2004, 53, 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Goetsch, A.L.; Nsahlai, I.V.; Sahlu, T.; Ferrell, C.L.; Owens, F.N.; Galyean, M.L.; Moore, J.E.; Johnson, Z.B. Prediction of metabolizable energy and protein requirements for maintenance, gain and fiber growth of Angora goats. Small Rumin. Res. 2004, 53, 339–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsahlai, I.V.; Goetsch, A.L.; Luo, J.; Johnson, Z.B.; Moore, J.E.; Sahlu, T.; Ferrell, C.L.; Galyean, M.L.; Owens, F.N. Metabolizable energy requirements of lactating goats. Small Rumin. Res. 2004. 53, 253–273. [CrossRef]

- Sahlu, T.; Goetsch, A.L.; Luo, J.; Nsahlai, I.V.; Moore, J.E.; Galyean, M.L.; Owens, F.N.; Ferrel, C.L.; Johnson, Z.B. Nutrient requirements of goats: Developed equations, other considerations and future research to improve them. Small Rumin. Res. 2004, 53, 191–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NRC. Nutrient Requirements of Beef Cattle, 8th rev. ed. National Academy Press, Washington, DC, 2016. [CrossRef]

- NRC. Nutrient Requirements of Dairy Cattle, 8th rev. ed. National Academy Press, Washington, DC, 2021. [CrossRef]

- AFRC (Agricultural and Food Research Council). Nutritive requirements of ruminant animals: Energy. AFRC Technical Committee on Responses to Nutrients, Report No. 5, Nutr. Abstr. Rev. Series B. 1990, 60:729-804.

- AFRC. Nutritive requirements of ruminant animals: Protein. AFRC Technical Committee on Responses to Nutrients, Report No. 9, Nutr. Abstr. Rev. Series B. 1992, 62:787-835.

- AFRC. Energy and protein requirements of ruminants. Advisory Manual, AFRC Technical Committee on Responses to Nutrients. 1993. CABI Publishing, Wallingford, Oxon, UK.

- AFRC. The nutrition of goats. AFRC Technical Committee on Responses to Nutrients. Report 10. 1998. CABI Publishing, Wallingford, UK, OCLC: 769705109.

- INRA (National Institute for Agricultural Research) Alimentation des Ruminants. R. Jarrige, ed. Versailles, France, 1978. INRA Publications.

- INRA (Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique) Alimentation des Bovins, Ovins et Caprins. INRA, Paris, France, 1988. INRA Publications.

- INRA (Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique). Ruminant Nutrition. Recommended Allowance and Feed Tables. R. Jarrige, ed. INRA, Paris, France, 1989. http://hdl.handle.net/102.100.100/256672?index=1.

- CSIRO. Feeding Standards for Australian Livestock. Ruminants. Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization Publications: Melbourne, Australia. 1990.

- CSIRO. Nutrient requirements of domesticated ruminants. Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization Publications: Collingwood, Victoria, Australia. 2007.

- Ma, T.; Deng, K.; Tu, Y.; Zhang, N.; Zhao, Q.; Li, C.; Jin, H.; Diao, Q. Recent advances in nutrient requirements of meat-type sheep in China: A review. J Integrative Agri 2022, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvani, D.B.; Pires, C.C.; Kozloski, G.V.; Wommer, T.P. Energy requirements of Texel crossbred lambs. J Anim Sci 2008, 86, 3480–3490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvani, D.B.; Pires, C.C.; Kozloski, G.V.; Sanchez, L.M.B. Protein requirements of Texel crossbred lambs. Small Rumin Res 2009, 81, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salah, N.; Sauvant, D.; Archimède, H. Nutritional requirements of sheep, goats and cattle in warm climates: A meta-analysis. Animal 2014, 8, 1439–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, H.T.; You, J.H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, F. Determination of energy and protein requirement for maintenance and growth and evaluation for the effects of gender upon nutrient requirement in Dorper × Hu crossbred lambs. Trop. Anim. Health Prod 2015, 47, 841–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, A.P.; Pereira, E.S.; Biffani, S.; Medeiros, A.N.; Silva, A.M.A.; Oliveira, R.L.; Marcondes, M.I. Meta-analysis of the energy and protein requirements of hair sheep raised in the tropical region of Brazil. J. Anim. Physio. Anim Nutr. 2018, 101, e52–e60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, E.S.; Lima, F.W.R.; Marcondes, M.I.; Rodrigues, J.P.P.; Campos, A.C.N.; Silva, L.P.; Bezerra, L.R.; Pereira, M.W.F.; Oliveira, R.L. Energy and protein requirements of Santa Ines lambs, a breed of hair sheep. Animal 2017, 11, 2165–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, E.S.; Pereira, M.W.F.; Marcondes, M.I.; Medeiros, N.A.; Oliveira, R.L.; Silva, L.P.; Mizubuti, I.Y.; Campos, A.C.N.; Heinzen, E.L.; Veras, A.S.C.; et al. Maintenance and growth requirements in male and female hair lambs. Small Rumin Res 2018, 159, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, M.S.; Souza, J.G.; Herbster, C.J.L.; Brito, N.A.S.; Silva, L.P.; Rodrigues, J.P.P.; Marcondes, M.I.; Oliveira, R.L.; Bezerra, L.R.; Pereira, E.S. Maintenance and Growth Requirements in Male Dorper × Santa Ines Lambs. Front Vet Sci 2021, 8, 676956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, M.H.M.R.; Resende, K.T.; Tedeschi, L.O.; Fernandes, J.S.; Silva, H.M.; Carstens, G.E.; Berchielli, T.T.; Teixeira, I.A.M.A.; Akinaga, L. Energy and protein requirements for maintenance and growth of Boer crossbred kids. J Anim Sci 2006, 85, 1014–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannas, A.; Tedeschi, L.O.; Fox, D.G.; Pell, A.N.; Van Soest, P.J. A mechanistic model for predicting the nutrient requirements and feed biological values for sheep. J Anim Sci 2004, 82, 149–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedeschi, L.O.; Cannas, A.; Fox, D.G. A nutrition mathematical model to account for dietary supply and requirements of energy and other nutrients for domesticated small ruminants: The development and evaluation of a Small Ruminant Nutrition System. Small Rumin Res 2010, 89, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, A.; Resende, K.; Teixeira, I.; Araújo, M.; Yáñez, E.; Ferreira, A. Energy Requirements for Maintenance and Growth of Male Saanen Goat Kids. Anim Biosci 2014, 27, 1293–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bompadre, T.F.; Neto, O.B.; Resende, K.T.; Teixeira, I.A.M.A. Energy requirements in early life are similar for male and female goat kids. Asian-Australas J Anim Sci 2014, 27, 1712–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, A.K.; Resende, K.T.; St Pierre, N.; Silva, S.P.; Soares, D.C.; Fernandes, M.H.M.R.; Souza, A.P.; Silva, N.C.D.; Lima, A.R.C.; Teixeira, I.A.M.A. Energy requirements for growth in male and female Saanen goats. J. Anim. Sci 2015, 93, 3932–3940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.C.D.; Yáñez, E.A.; Medeiros, A.N.; Resende, K.T.; Filho, J.M.P.; Fernandes, M.H.M.R.; Almeida, A.K.; Teixeira, I.A.M.A. Protein and energy requirements of castrated male Saanen goats. Small Rumin Res 2015, 123, 1, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.K.; Resende, K.T.; Tedeschi, L.O.; Fernandes, M.H.M.R.; Regadas Filho, J.G.L.; Teixeira, I.A.M.A. Using body composition to determine weight at maturity of male and female Saanen goats. J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 94, 2564–2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, F.O.M.; Berchielli, T.T.; Resende, K.T.; Gomes, H.F.B.; Almeida, A.K.; Sakomura, N.K.; Teixeira, I.A.M.A. Energy requirements for growth of pubertal female Saanen goats. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. (Berl.) 2016, 100, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiredo, F.O.M.; Leite, R.F.; St- Pierre, N.R.; Resende, K.T.; Almeida, A.K.; Souza, A.P.; Teixeira, I.A.M.A. Energy and protein requirements of weaned male and female Saanen goats. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. (Berl.) 2017, 101, 1014–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, I.A.M.A.; Fernandes, M.H.M.R.; Filho, J.M.P.; Canesin, R.C.; Gomes, R.A.; Resende, K.T. Body composition, protein and energy efficiencies, and requirements for growth of F1 Boer x Saanen goat kids. J. Anim. Sci. 2017, 95, 2121–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harter, C.J.; Lima, L.D.; Silva, H.G.O.; Castagnino, D.S.; Rivera, A.R.; Resende, K.T.; Teixeira, I.A.M.A. Energy and protein requirements for maintenance of dairy goats during pregnancy and their efficiencies of use. J. Anim. Sci. 2017, 95, 4181–4193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, A.P.; St-Pierre, N.R.; Fernandes, M.H.R.M.; Almeida, A.K.; Vargas, J.A.C.; Resende, K.T.; Teixeira, I.A.M.A. Energy requirements and efficiency of energy utilization in growing dairy goats of different sexes. J Dairy Sci 2020, 103, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.P.; Vargas, J.A.C.; Fernandes, M.H.M.R.; Almeida, A.K.; Resende, K.T.; Teixeira, I.A.M.A. Metabolizable Protein: 2. Requirements for Maintenance in Growing Saanen Goats. Front Vet Sci 2021, 8, 650203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.A.; Carvalho, G.G.P.; Azevedo, J.A.G.; Zanetti, D.; Santos, E.M.; Pereira, M.L.A.; Pereira, E.S.; Pires, A.J.V.; Valadares, F.S.C.; Teixeira, I.A.M.A.; et al. Metabolizable protein: 1. Predicting equations to estimate microbial crude protein synthesis in small ruminants. Front Vet Sci 2021, 8, 650248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas, J.A.C.; Almeida, A.K.; Souza, A.P.; Fernandes, M.H.M.R.; Harter, C.J.; Resende, K.T.; Teixeira, I.A.M.A. Macromineral requirements for maintenance in male and female Saanen goats: A meta-analytical approach. Livestock Sci 2020, 235, 104003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, M.H.M.R.; Resende, K.T.; Tedeschi, L.O.; Teixeira, I.A.M.A.; Fernandes, J.S. Macromineral requirements for the maintenance and growth of Boer crossbred kids. J. Anim. Sci. 2012, 90, 4458–4466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, J.M.; Resende, K.T.; Teixeira, I.A.M.A.; Vargas, J.A.C.; Lima, A.R.; Leite, R.F.; Figueiredo, F.O.; Tedeschi, L.O.; Fernandes, M.H. Net macromineral requirements in male and female Saanen goats. J Anim Sci 2016, 9, 3409–3419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, J.A.C.; Almeida, A.K.; Souza, A.P.; Fernandes, M.H.M.R.; Resende, K.T.; Teixeira, I.A.M.A. Sex effects on macromineral requirements for growth in Saanen goats: A meta-analysis. J Anim Sci 2017, 95, 4646–4657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkens, M.R.; Breves, G.; Schröder, B. A goat is not a sheep: Physiological similarities and differences observed in two ruminant species facing a challenge of calcium homeostatic mechanisms. Anim Prod Sci 2014, 54, 1507–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NRC. Effect of Environment on Nutrient Requirements of Domestic Animals. National Academy Press, Washington, DC, 1981. [CrossRef]

- NRC. Nutritional Energetics of Domestic Animals and Glossary of Energy Terms. National Academy Press, Washington, DC, 1981. [CrossRef]

- NRC. Ruminant Nitrogen Usage. National Academy Press, Washington, DC, 1985. [CrossRef]

- Satter, L.D.; Roffler, R.E. Nitrogen requirement and utilization in dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 1975, 58, 1219–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlecht, E.; Richter, H.; Fernandez-Rivera, S.; Becker, K. Gastrointestinal passage of Sahelian roughages in cattle, sheep and goats, and implications for livestock-mediated nutrient transfers. Anim. Feed Sci. and Tech. 2007, 137, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.M.M.; Hervas, G.; Belenguer, A.; Celaya, R.; Rodrigues, M.A.M.; Garcia, U.; Frutos, P.; Osoro, K. Comparison of feed intake, digestion and rumen function among domestic ruminant species grazing in upland vegetation communities. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. (Berl). 2017, 101, 846–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SCA (Standing Committee on Agriculture, Ruminants Subcommittee). Feeding Standards for Australian Livestock. Ruminants. CSIRO Publications, East Melbourne, Australia, 1990.

- NRC. Nutrient Requirements of Dairy Cattle, 7th rev. ed. National Academy Press, Washington, DC, 2001. [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Goetsch, A.L.; Nsahlai, I.V.; Sahlu, T.; Ferrell, C.L.; Owens, F.N.; Galyean, M.L.; Moore, J.E.; Johnson, Z.B. Metabolizable protein requirements for maintenance and gain of growing goats. Small Ruminant Res. 2004, 53, 309–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NRC. Nutrient Requirements of Beef Cattle, 6th rev. ed. National Academy Press, Washington, DC, 1984. [CrossRef]

- NRC. Nutrient Requirements of Beef Cattle, 7th rev. ed. (Updated). National Academy Press, Washington, DC, 2000. [CrossRef]

- Hauschild, L.; Pomar, C.; Lovatto, P.A. Systematic comparison of the empirical and factorial methods used to estimate the nutrient requirements of growing pigs. Animal 2010, 4, 714–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedeschi, L.O. Mathematical modeling in ruminant nutrition: Approaches and paradigms, extant models, and thoughts for upcoming predictive analytics. Journal of Anim. Sci. 2019, 97, 1921–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, S.; Shao, Y.; Yu, Y.; Sha, K.; Jiang, Y.; Xian Zhang, X.; Zhong, Y.; Shi, H.; Li, W. The miR-214-5p/lactoferrin/miR-224-5p/ADAM17 axis is involved in goat mammary epithelial cell’s immune regulation. Animals 2023, 13, 2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal Akyüz, B.; Sohel, M.M.H.; Konca, Y.; Korhan Arslan, K.; Gürbulak, K.; Abay, M.; Kaliber, M.; White, S.N.; Cinar, M.U. Effects of low and high maternal protein intake on fetal skeletal muscle miRNAome in sheep. Animals Accepted for publication. 2024, 14. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).