1. Introduction

Interactions between surfactants and polymers is an important phenomenon relevant to several practical applications in paints and coatings, personal care products, chemical, pharmaceutical, mineral processing and petroleum industries [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. The simultaneous presence of polymer and surfactant molecules alter the rheological properties of solutions, adsorption characteristics at solid-liquid interfaces, stability of colloidal dispersions, the solubilization capacities in water for sparingly soluble molecules, and liquid-liquid interfacial tensions, and thereby impact either beneficially or adversely the practical applications. An important application that has occupied the attention of researchers over the last five decades is the enhanced recovery of petroleum from existing reservoirs by chemical flooding [

2,

3,

4,

5]. In the chemical flooding process for enhanced oil recovery (EOR), a surfactant slug (often composed of anionic petroleum sulfonates) is injected into the ground to displace the formation oil. It is followed by a polymer (typically anionic or nonionic)-thickened mobility buffer and drive water. The surfactant slug is designed to generate ultra-low interfacial tensions against the formation oil. The polymer buffer is designed to possess adequate mobility control characteristics. The simultaneous presence of polymer and surfactant molecules in the reservoir results in interactions between these molecules as well as with the minerals in the reservoir rocks. These interactions among polymer, surfactant and electrolytes can drastically alter the properties of the surfactant slug and/or of the polymer mobility buffer from their designed characteristics, specifically due to changes in their phase behavior, leading to significant reduction in the anticipated oil recovery.

Many experimental studies on the phase behavior of solutions containing anionic or nonionic polymer molecules and anionic surfactant molecules have been carried out since early 1970s, but surprisingly no theoretical treatment has been developed to date. Note that we are not concerned here with oppositely charged polymers and surfactants but polymers and surfactants, typically both being anionic. Most of the early phase behavior studies came from the petroleum industry in the course of the EOR research in laboratory as well as in large scale oilfield reservoirs. The earliest experimental work is that of Trushenski et al. [

7,

8], who studied the phase behavior of solutions containing mixtures of Mahogony AA sulfonate (a petroleum derived surfactant), isopropyl alcohol, water, sodium chloride and either of the two polymers, Pusher 700 (a hydrolyzed polyacrylamide) or Kelco's Xanflood (a Xanthan biopolymer). The interest was on identifying the domain of single-phase existence in the multicomponent system and the composition boundaries at which a phase separation occurs. They found that the phase behavior of the systems differed very little for the two polymers. The phase behavior was also not affected by the solution concentration of the polymer in the range 500 to 1500 ppm. The single-phase region in the composition space of the phase diagram expanded when the temperature increased from 110°F to 190°F. Further, the addition of small quantities of oil was found to stabilize an otherwise unstable (phase separating) polymer-surfactant-electrolyte system. Szabo [

9] examined systems constituted from polymers including Xanflood, hydroxyethyl and methyl celluloses, hydrolyzed and unhydrolyzed polyacrylamide, and polyacrylamido-methyl propane-sulfonate and four different petroleum sulfonate type surfactants. The phase behavior of solutions were monitored in systems containing 5 weight percent sulfonate and 2 weight percent NaCl. In all cases, phase separation into two liquid phases occurred on contacting the different components. The top phase was found to contain most of the polymer while the bottom phase contained most of the sulfonate. As the polymer concentration was increased, the volume fraction of the surfactant rich bottom phase decreased. The polymer concentration in the top phase and the sulfonate concentration in the bottom phase both increased. However, the polymer concentration in the bottom phase and the sulfonate concentration in the top phase remained constant. No systematic differences were seen with the variation in the type of polymer molecules.

Pope et al. [

10] studied the effect of salt concentration on the phase behavior of polymer-surfactant solutions. The amount of NaCl required to induce phase separation in polymer-surfactant solutions was measured for combinations of different polymers and surfactants and at various concentrations of them in solution. The electrolyte concentration at which phase separation occurs, designated as the critical electrolyte concentration (CEC), was found to be independent of the polymer type and polymer concentration (in the range 100 to 1000 ppm). No variation of CEC with the molecular weight of the polymer (in the range 4 x 10

5 to 5 x 10

6) was observed for polyethylene oxide.

Gupta [

11] examined the effect of calcium salts on the phase behavior of Pusher 700 - Mahogony AA sulfonate solution, containing 1600 ppm of the polymer. At 50 ppm concentration of calcium the solution was stable, whereas at 300 ppm the solution separated into a polymer-rich top phase and a surfactant-rich bottom phase. In general, the influence of the divalent electrolyte was more severe on the phase stability compared to that of the monovalent electrolyte.

Kalpakci [

12] investigated the phase behavior of several anionic and nonionic surfactant solutions in the presence of polymers. He found that the phase stability of the solutions decreased with increasing concentration of the surfactant and of the electrolyte as well as with increasing equivalent weight of the surfactant. The polymer size in the molecular weight range 7 x 10

4 to 2 x 10

6 and polymer concentration between 100 and 1500 ppm were found to have very little effect on the stability of the anionic sulfonate-polymer solutions. It was found that the polymer-surfactant solutions can be stabilized by the addition of low molecular weight additives such as alcohols or low molecular weight sulfonates a well as by the addition of small amounts of oil. Further, unstable polymer-surfactant solutions were stabilized if the solution was subjected to ultrasonication resulting in the breakdown of the molecular size of the polymer.

These experimental results available in the early EOR literature show that phase separation is a common phenomenon occurring in polymer-surfactant solutions in the presence of electrolytes, even at low concentrations of various components. The phase separation patterns are not significantly influenced by the molecular type or the molecular size of the polymer for the high molecular weight polymers studied and by the variations in polymer concentrations over the limited range of 100 to 1500 ppm typically investigated for EOR applications. The phase behavior is, however, critically affected by the equivalent weight of the surfactant and by the type and amount of the electrolyte added. The stability of the polymer-surfactant solution is enhanced if the polymer molecular weight is significantly reduced as in the ultrasonication experiment or by the addition of certain types of additives including small amounts of oil. Beyond these generalizations, little is known concerning the phase behavior of polymer-surfactant solutions from a predictive point of view, even after forty years. It is well recognized in recent oil field simulations, that reliable information on the polymer-surfactant phase behavior is needed for making realistic predictions of oil recovery efficiencies [

3,

4,

5].

The principal goal of this work is to develop a predictive approach to the phase behavior of aqueous solutions containing polymer, surfactant, and electrolyte molecules. Specifically, we seek to develop a thermodynamic treatment of phase behavior and compare the predictions of the treatment with experimental results obtained on reasonably well-defined chemical components in solution. Towards this goal, we postulate a novel approach to treat the four-component system of polymer, surfactant, electrolyte, and water by viewing it as a pseudo binary system. The essence of this approach is as follows. One component of the pseudo binary system is the polymer molecule, treated as the solute molecule. The other component, termed here pseudosolvent, is made up of water, the surfactant, and the electrolyte. The thermodynamics of this solute-pseudosolvent binary system is quantitatively described using the formalism of any suitable polymer solution theory available in the literature. The criterion of phase separation stipulated by the polymer solution theory is then applied to the pseudo binary system in order to find the composition boundary of the pseudo-components at which the solution undergoes phase separation. This composition boundary is then reinterpreted in terms of the actual concentrations of the surfactant and the electrolyte constituting the pseudosolvent.

In

Section 2, the experimental methods and the materials used, and the observed phase behavior are briefly described for some polymer and surfactant systems of interest to the enhanced oil recovery application. In

Section 3, the conceptual outline of the pseudosolvent model is presented. The pseudosolvent model is quantitatively developed in

Section 4 and the estimation of model parameters is detailed. Phase diagrams are computed and compared to the experimentally measured ones in

Section 5. Most importantly, for ease of practical applications, a simple approach to constructing phase diagrams using one experimentally measured surfactant-electrolyte composition lying at the phase boundary is proposed, without requiring any information on the polymer. The last section summarizes the principal conclusions from this work.

2. Experimental Study of Phase Behavior

2.1. Materials

The water-soluble polymers used in this study are listed in

Table 1. The polyacrylamide and the biopolymer have been explored both in laboratory and field applications for enhanced oil recovery [

2,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Flocon is an aqueous solution of the microbially produced heteropolysaccharide xanthan gum, with a molecular weight of about 2 x 10

6. Polyethylene oxide (PEO) has been used in several studies of polymer-surfactant interactions and is a well-defined polymer for modeling studies [

10,

12].

Commercially available low molecular weight anionic surfactants as well as deoiled petroleum sulfonates were employed in this study.

Table 2 lists the surfactants, their chemical structures, the names of suppliers.

The petroleum sulfonates supplied by Witco Chemical (TRS 40 and TRS 10-410) included a distribution of molecules as well as some amount of oil. These petroleum sulfonates were deoiled and fractionated into two parts, one with a low average equivalent weight (LEW) and the other with a high average equivalent weight (HEW). The HEW samples were used for the phase behavior measurements [

13]. Other surfactants were used as received. For the petroleum sulfonates, the chemical formula is given assuming the presence of a single monosulfonate having the measured equivalent weight.

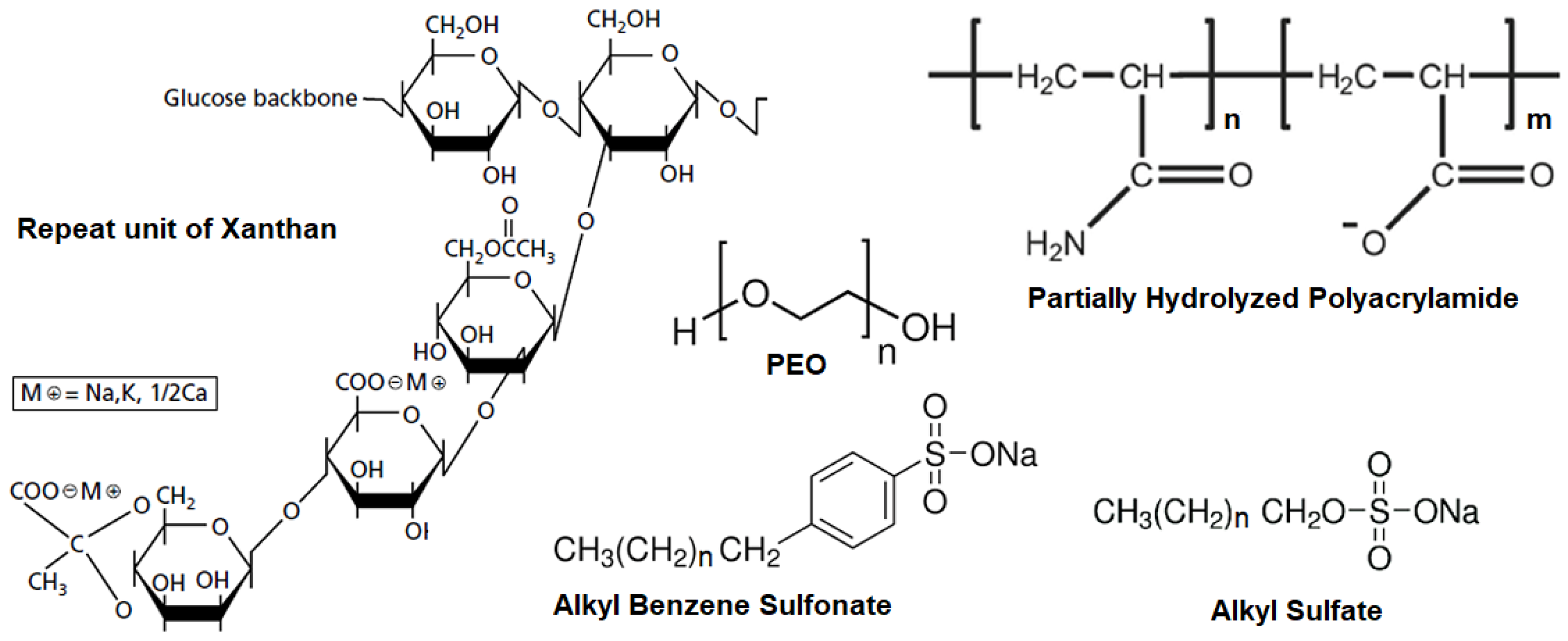

The chemical structures of the polymer repeat units and the surfactants used in this study are presented in

Figure 1.

2.2. Phase Behavior Measurements

Aqueous solutions of polymers with specified amounts of salt were prepared using either a magnetic stirrer or a propeller-type mixer. Care was taken to ensure that maximum dispersion of polymer molecules was achieved without simultaneously causing any mechanical degradation. The viscosity of the polymer solution was measured prior to phase behavior studies to make sure that no polymer degradation had occurred. The solution of biopolymer (Flocon) was prefiltered through a Whatman No. 3 filter paper to remove any impurities and bacteria from the Flocon material before the phase behavior studies [

13].

Desired amounts of surfactants were weighed in glass containers (bottles) to which previously prepared polymer-electrolyte aqueous solution was added. The sample bottles were mixed with a magnetic stirrer. The solutions were kept at room temperature (24 ± 2°C) for phase behavior observations. The concentration boundaries which separate the one-phase region from the two-phase region for several polymer-surfactant systems were established based on two weeks of solution equilibration.

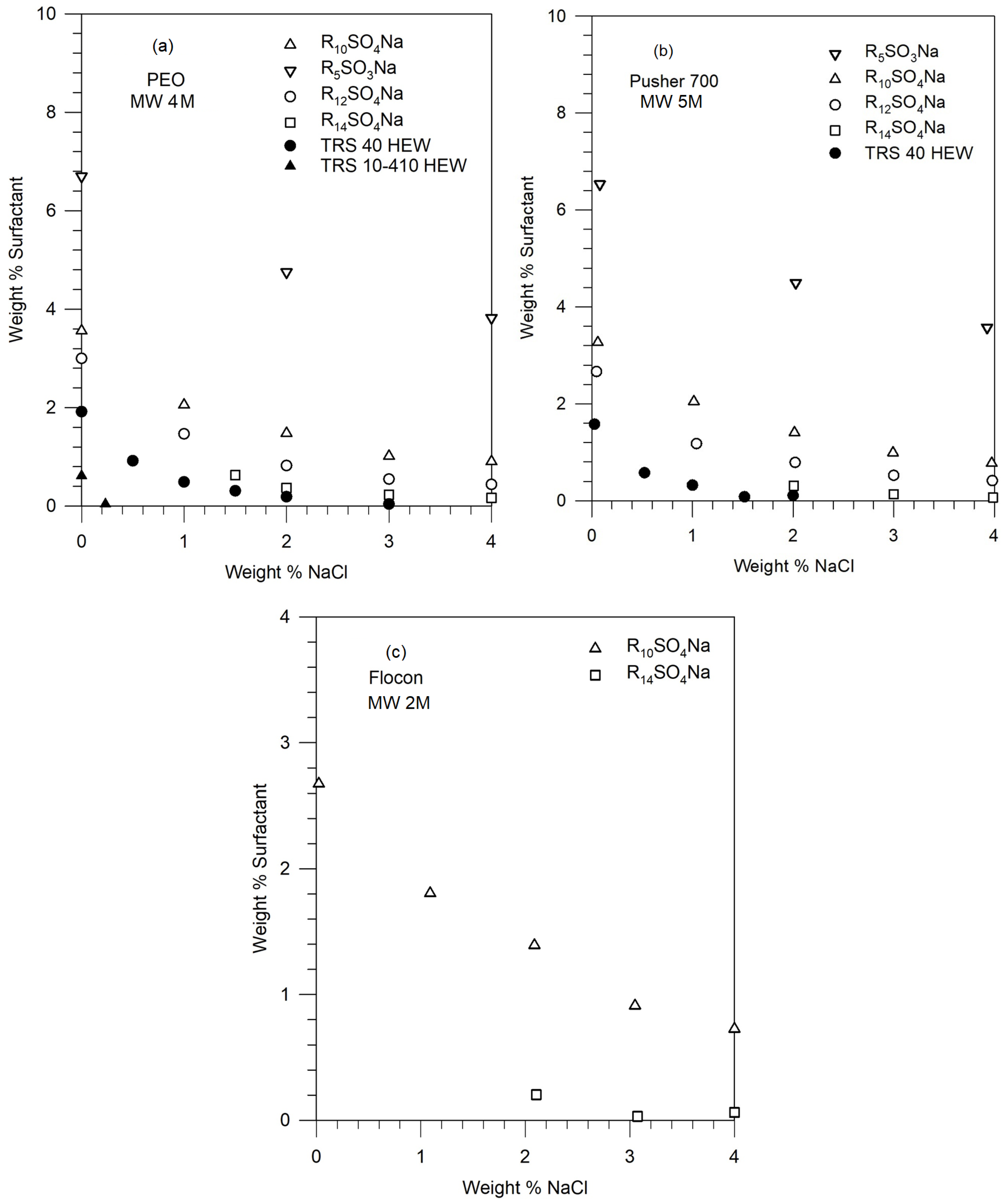

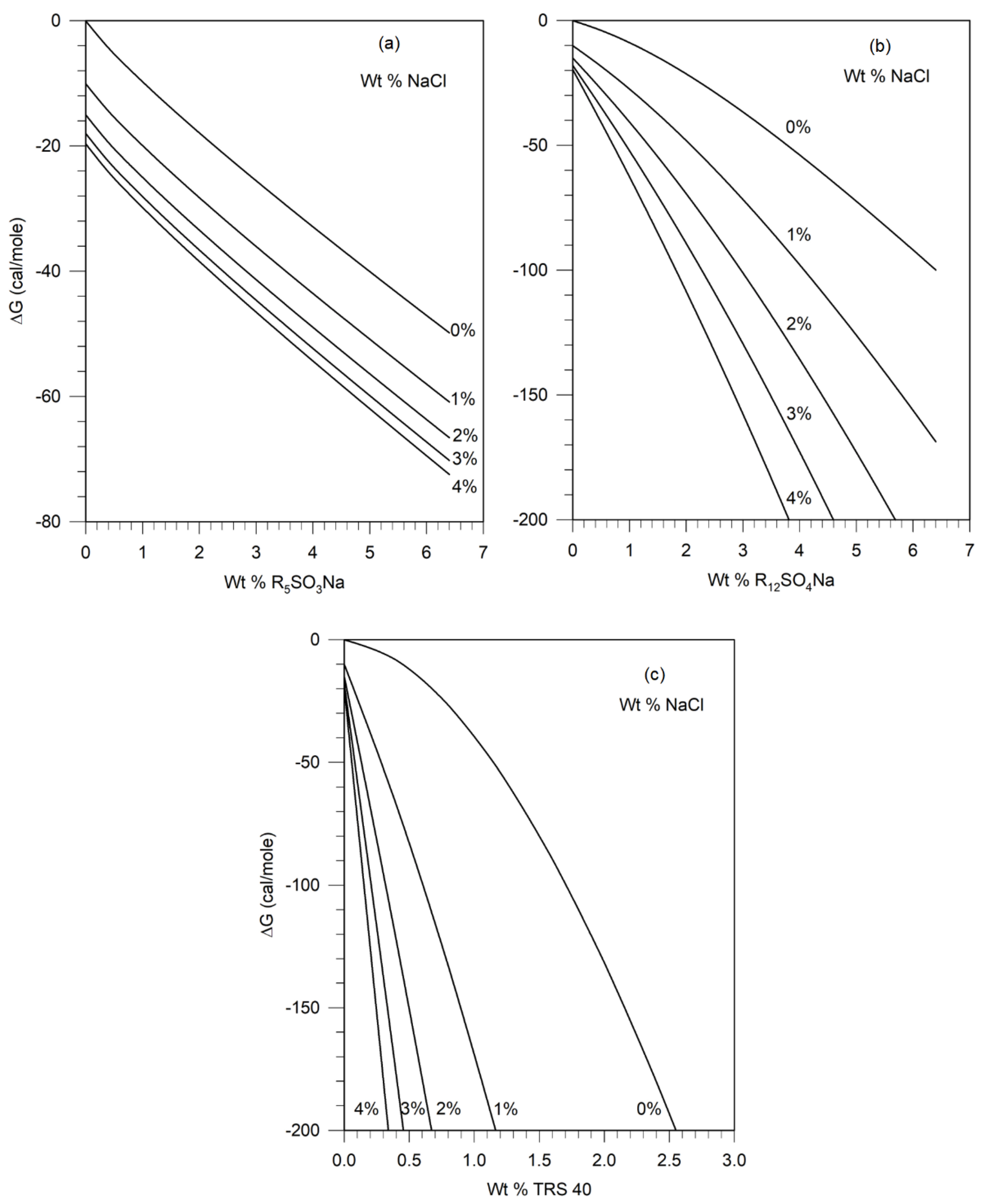

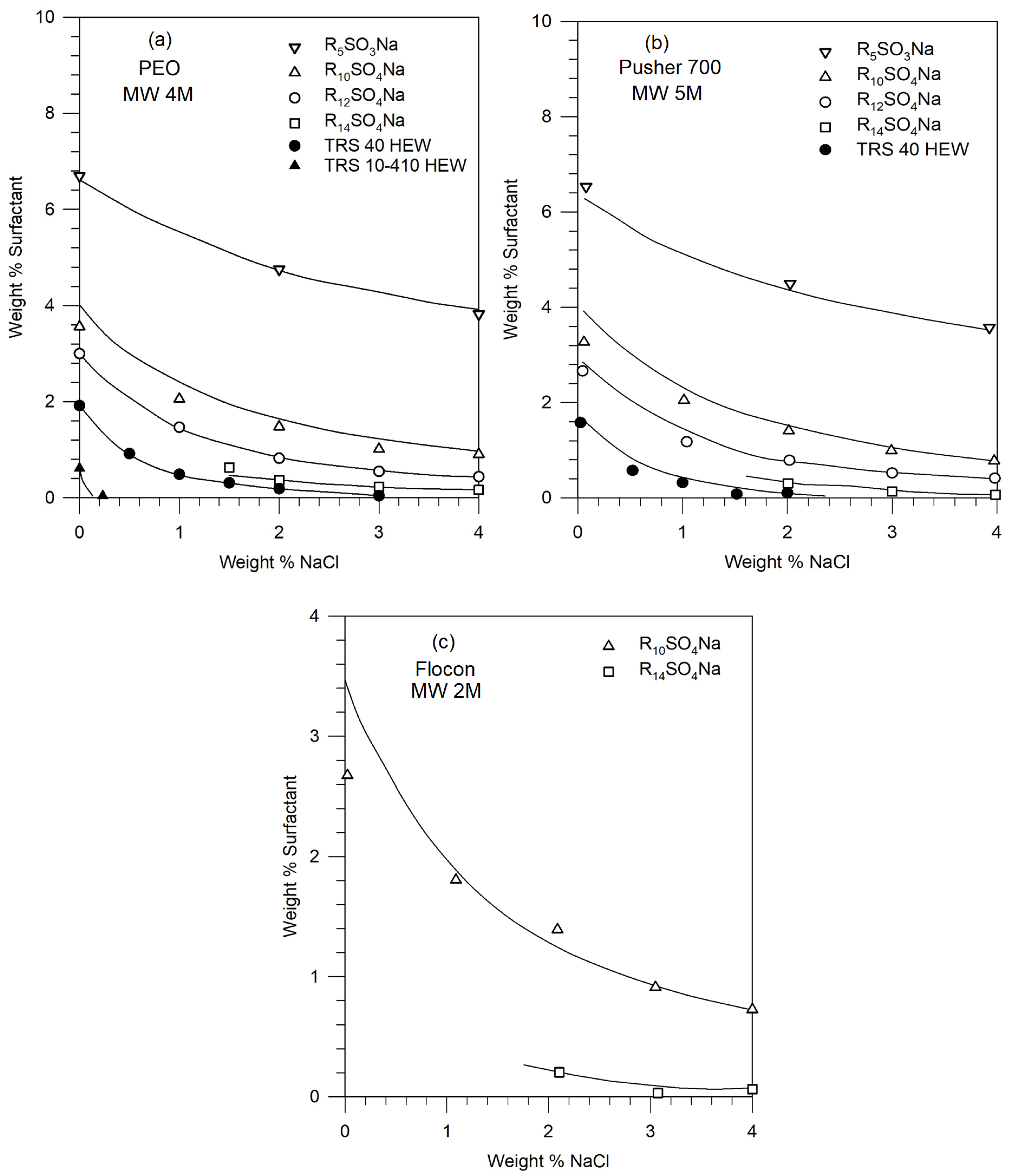

Figures 2 shows the phase boundaries for different surfactants in solutions of PEO (4M), Pusher 700 (5M), and Flocon (2M). The points represent the experimentally observed compositions at which phase separation occurred. Note that the salt and surfactant concentrations are expressed as weight percent, that is weight (in g) of the component in 100 g of the solution. These can be converted to molar concentrations assuming that the total volume of the solution is practically that of water, given that the concentrations of the surfactant and the salt are not very large.

Figure 2 shows that for a given polymer molecule, the phase stability of the polymer-surfactant solution decreases (namely, phase separation occurs) with increasing equivalent weight of the surfactant, increasing salt concentration, and increasing surfactant concentration. For a given surfactant molecule, the phase stabilities for the polymers decrease in the following order: PEO (4M) ≥ Pusher 700 ≥ Flocon, but the difference among these high molecular weight polymers is not very significant.

3. Development of Pseudosolvent Model for Predicting Phase Behavior

3.1. Pseudosolvent and its Characteristic Energy

An evaluation of polymer solution theories in the literature makes it apparent that an adequate predictive theory for polymer-water system is presently not available [15,16]. The classical Flory-Huggins theory, given the original meaning of the Flory interaction parameter

[

14], cannot predict the characteristic lower critical solution temperature (LCST) behavior exhibited by many aqueous polymer solutions, including the PEO-water system. While using the classical Flory theory, usually, the interaction parameter is empirically fitted as a function of the temperature and the volume fraction of the polymer in solution to describe (not predict) the experimentally observed phase behavior of polymer-water systems [

15,

16,

17]. The development of models for aqueous polymer solutions with true predictive capabilities is an area of continuing interest [

18,

19]. When the aqueous polymer solution also includes surfactant and electrolyte molecules, a formal molecular level modeling of the four-component system becomes even more complex. Since the primary focus of this work is on predicting the phase behavior of these four component systems, a simplified approach tailored to treat phase behavior, is proposed here.

In this approach, the pure solvent (water) is replaced by a pseudosolvent made up of water, electrolyte, and surfactant (present as both singly dispersed surfactant molecules and micellar aggregates). The polymer molecule is the solute. In this manner, the four-component system is treated in terms of an equivalent pseudo two-component system. We then need a polymer solution model as a framework to describe this pseudobinary system and for this purpose we choose the lattice fluid model of polymer solutions developed by Sanchez and Lacombe [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. This model is chosen because it allows representation of the LCST behavior and is thus capable of at least qualitatively or semi-quantitatively describe aqueous polymer solutions. It should be noted that the LCST behavior in lattice fluid model emerges from the consideration of the presence of vacant sites in the lattice and the resulting entropic effects. This is in contrast to the LCST behavior in aqueous polymer solutions that arises from hydrogen bonding interactions. Indeed the lattice fluid model has been extended to account for hydrogen bonding [

25], but for our purposes of just needing a polymer solution model framework, the basic lattice fluid model is adequate. The lattice fluid model for pure fluids and polymer solutions is briefly summarized in the Appendix with all key equations used in this study.

In the lattice fluid model, a pure component is defined by three equation of state parameters, a characteristic energy

, a characteristic size of the component r and a characteristic lattice site of hard-core volume

. One can alternately use the characteristic pressure P*, characteristic temperature T* and the characteristic density

as the defining parameters (see Equations (A-1) to (A-4) in the Appendix). For small molecules, the equation of state parameters for the pure components are usually estimated from experimental saturation vapor pressure data. The characteristic parameters for water determined in this way [

20] are,

= 26,520 atm,

= 623

oK and

= 1.105 g/cm

3, or equivalently,

= 1.238 kcal/mol,

= 1.927 cm

3/mol and r = M/(

) = 8.45, the molecular weight of water M being 18. For high molecular weight polymers, vapor pressures are negligibly small and therefore, the equation of state parameters are usually determined from experimental density data. Alternately, when only limited density data are available, the equation of state parameters can be determined from a single experimental density ρ, thermal expansion coefficient α and isothermal compressibility β, at the same temperature and pressure, using Equations (A-6) and (A-7) in the Appendix. For polyethylene oxide of molecular weight M, the equation of state parameters estimated by this single point method [

13] are,

= 3,963 atm,

= 597

oK and

= 1.202 g/cm

3, or equivalently,

= 1.194 kcal/mol,

= 12.36 cm

3/mol and r = M/(

). Note that the characteristic size parameter r is obviously dependent on the molecular weight M of the polymer.

For the pseudosolvent composed of water, the surfactant, and the electrolyte as the actual components, we assume that two of its equation of state parameters, and , (subscript 1 denotes the solvent and 2 denotes the polymer) are identical to those of water. The third parameter, characteristic energy (the subscript 1P is introduced to distinguish it from 1 used for water) is taken to be different from that of water and is assumed to account for all the surfactant-electrolyte composition-dependent characteristics of the pseudosolvent. Thus the critical postulate underlying our pseudosolvent model is the assumption that a single characteristic energy parameter, contains all the information related to the type and amounts of surfactant and electrolyte molecules present in water. It should be mentioned that this is an ad hoc extra-thermodynamic postulate and is justified only a posteriori by the resulting simplicity of the thermodynamic approach and the usefulness of the results.

3.2. Polymer – Pseudosolvent Binary Parameters ξ and δ

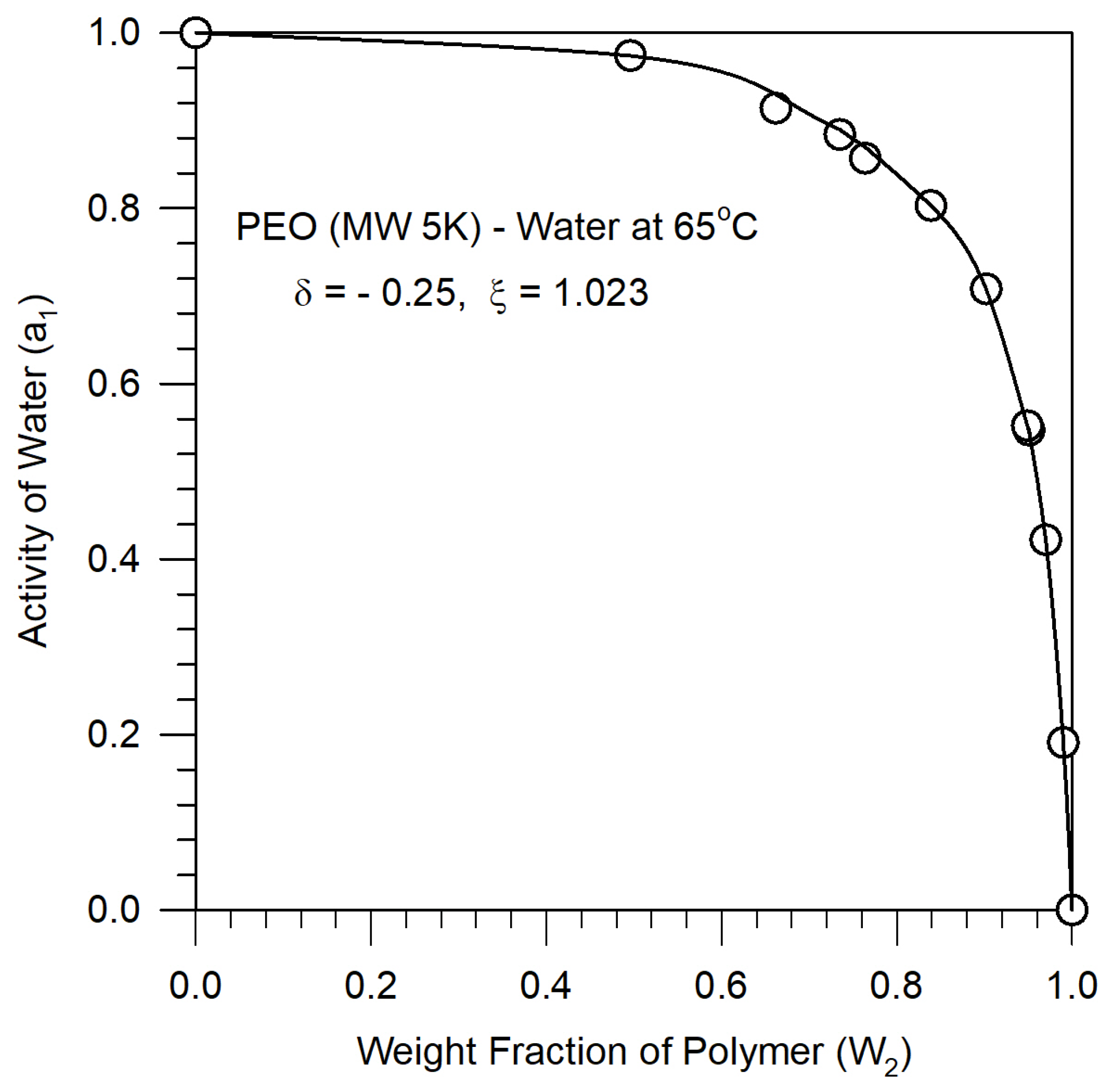

For the binary polymer-pseudosolvent solution two additional parameters characteristic of the mixture properties are introduced, as is common in many theories of solutions to account for non-idealities of mixture behavior. The binary energy parameter ξ represents the deviation of the interaction energy from the geometric mean rule and the binary volume parameter δ represents the deviation of the close packed mixture volume from the arithmetic additivity rule. The introduction of binary parameters ξ and δ adds considerable flexibility to the lattice fluid model for mixtures, as it does in all solution models in the literature. The binary parameters for the polymer-pseudosolvent are assumed to be the same as for polymer-water and determined from experimental thermodynamic data on polymer-water solutions. The estimates for the binary parameters obtained from different solution properties such as activity of the solvent, heat of mixing or volume change on mixing are generally not identical, reflecting the fundamental inadequacies in the current state of the theory of the liquid state. Since we are interested in the polymer solution phase behavior, we use the water activity data to estimate the binary polymer-water parameters. As shown in

Figure 3, the experimental activity data [

26] for a PEO-water system is fitted well by the theoretical water activity calculated from Equation (A-13) in the Appendix, for the binary parameter values ξ = 1.023 and δ = - 0.25. These binary parameters are taken to be independent of temperature.

3.3 Polymer – Pseudosolvent Phase Diagram in the Parametric Space of

Given the equation of state parameters

,

,

for the polymer, the two equation of state parameters,

,

for the pseudosolvent (assumed to be the same as for water) and the binary parameters, ξ, δ for the polymer-pseudosolvent (assumed to be the same as for polymer-water), one can calculate the phase behavior of the polymer solution for various pseudosolvents characterized by differing values for

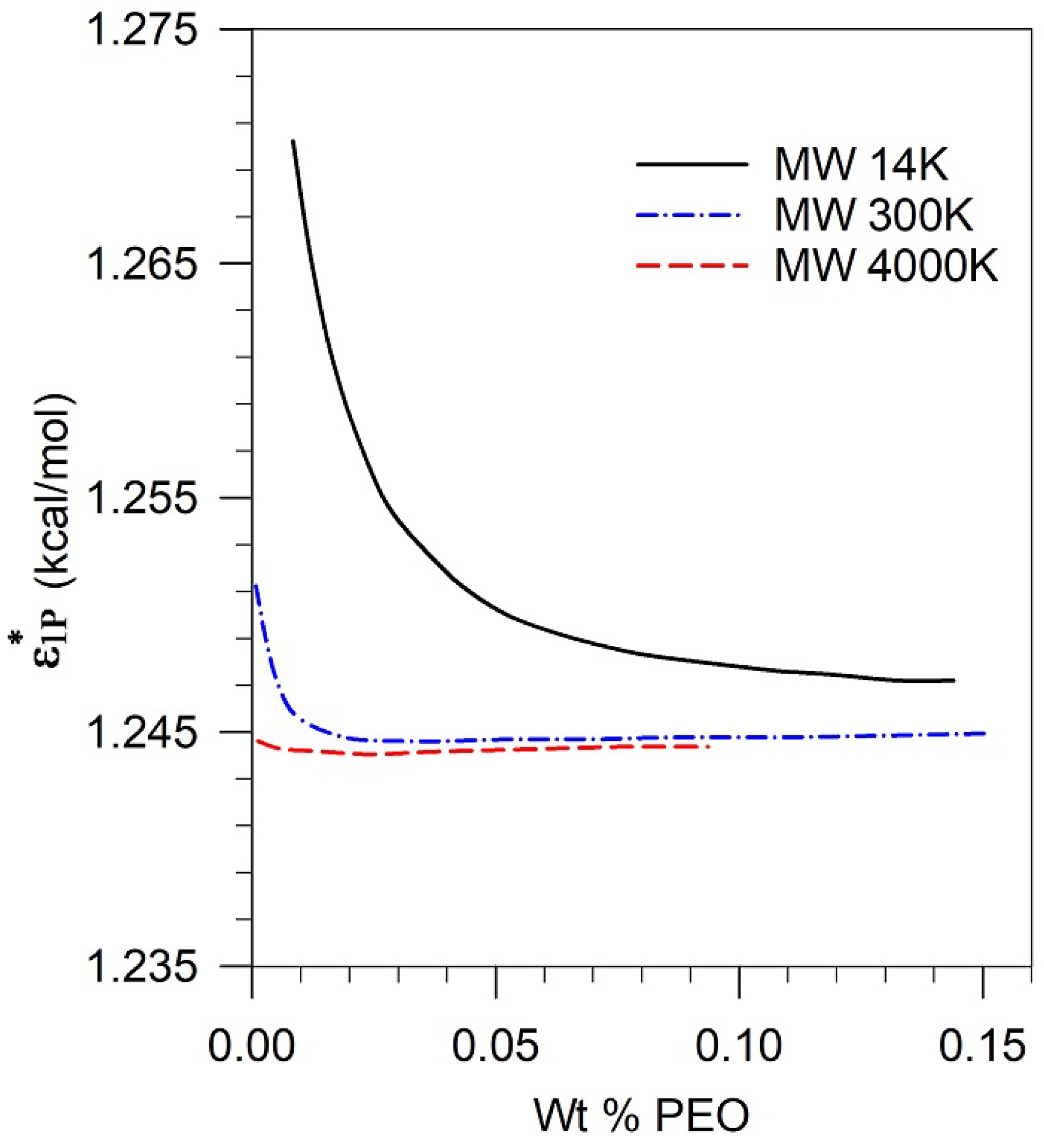

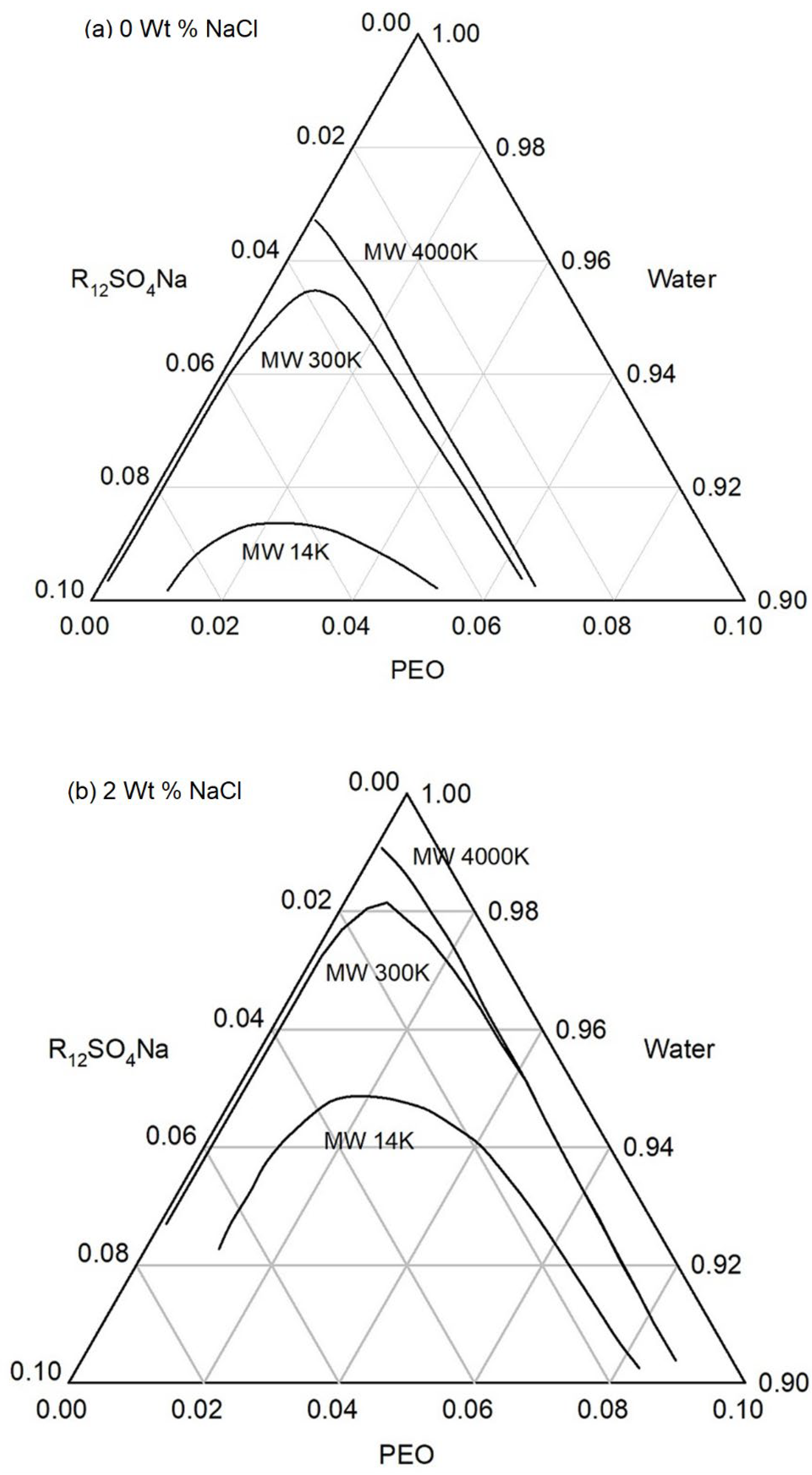

. The phase stability criteria are summarized in Equations (A-20) to (A-23) in the Appendix. Since the equation of state parameters as well as the binary polymer-water binary interaction parameters are known for polyethylene oxide, we were able to construct the polymer-pseudosolvent phase diagram shown in

Figure 4 for three different molecular weights of PEO (14 K, 300 K and 4 M) in the

vs polymer concentration space. The phase diagram shows that while the characteristic parameter

of the pseudosolvent is below a certain value, the polymer-pseudosolvent solution is stable; and when

is above a certain value, the solution is unstable. The characteristic energy of the pseudosolvent

at which phase separation occurs is a function of the polymer molecular weight, the concentration of the polymer in solution as well as the temperature. Similar phase diagrams can be constructed for other polymers of interest, knowing their equation of state parameters and their binary interaction parameters with water.

Figure 4 shows that for high molecular weights polymer, PEO (4M) and PEO (300K), the value of

at the phase boundary is almost constant in the polymer concentration range of 100 ppm to 1500 ppm (equivalently 0.01 wt% to 0.15 wt%). In contrast, for the low molecular weight polymer PEO (14K), the value of

is significantly higher than that for the high molecular weight polymer, especially at low polymer concentrations.

3.4. Mapping Characteristic Energy of the Pseudosolvent to its Composition

The characteristic energy

of the pseudosolvent needs to be translated to the actual composition of the pseudosolvent (namely the chemical structures and concentrations of the surfactant and the electrolyte). This is done by considering the free energy difference ΔG between the pseudosolvent and water. In the formalism of the lattice fluid model, given the equation of state parameters for a pure fluid, the free energy G of a pure fluid can be calculated using Equation (A-1) in the Appendix by introducing in it the fluid density calculated from the equation of state, Equation (A-4). Consequently, the free energy difference ΔG between the pseudosolvent and water is calculated as follows:

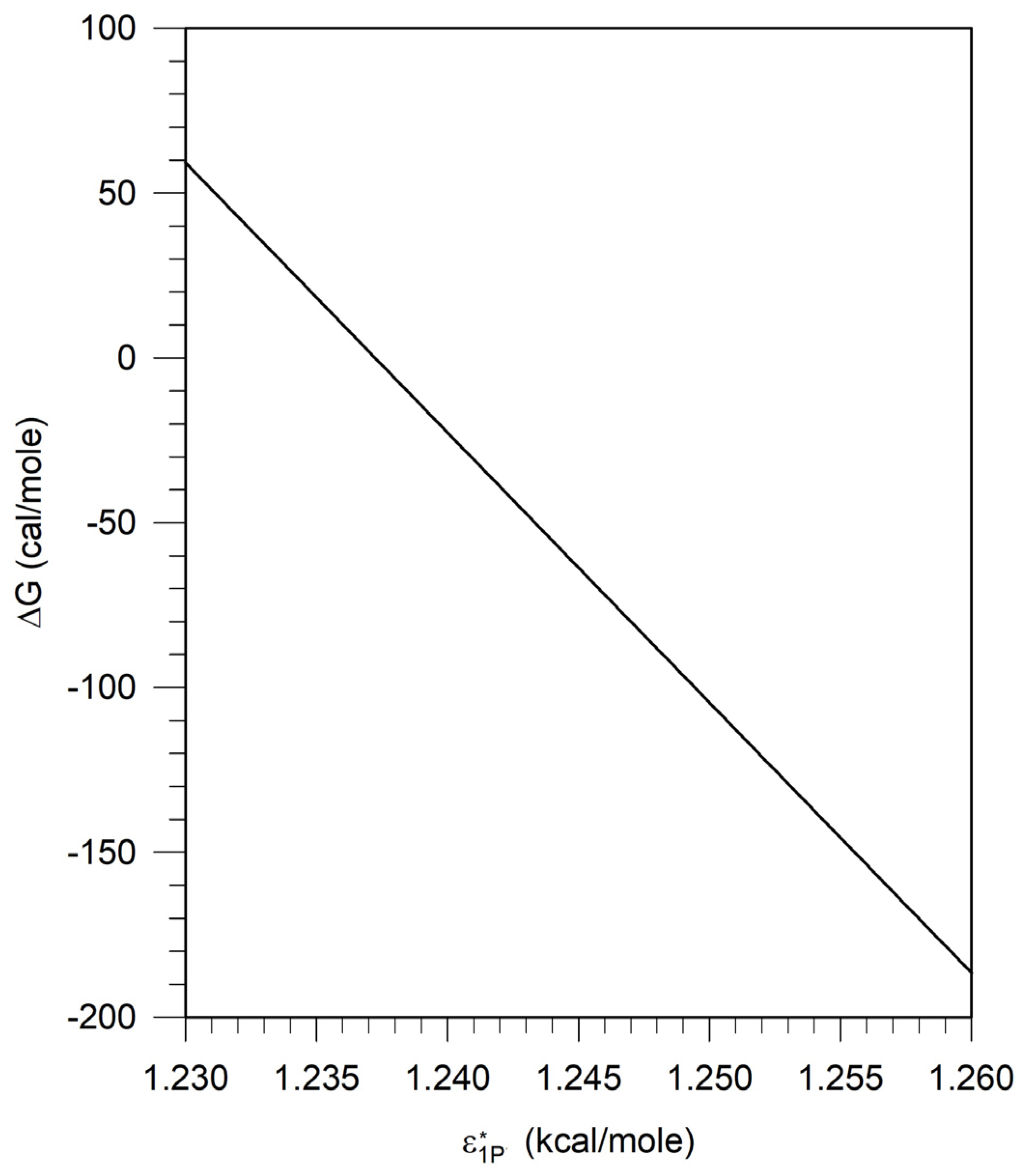

The calculated relation between ΔG and

is presented in

Figure 5. Note that this relation is independent of the polymer and is thus a universal relation for pseudosolvents in the framework of the lattice fluid model and can be used to explore the phase behavior involving any polymer.

The characteristic energy parameter for water is 1.238 at which ΔG = 0. For < , ΔG > 0 and for > , ΔG < 0. The characteristic energy parameter is a measure of the cohesive energy of the solvent. The higher the energy parameter, the larger the cohesive energy for the solvent, greater the probability of polymer exclusion and therefore the larger the likelihood of phase separation.

4. Calculation of ΔG from Thermodynamic Data on Surfactants and Electrolytes

The thermodynamic quantity of interest for predicting the phase behavior of polymer-surfactant-electrolyte-water system, in the framework of the pseudosolvent concept, is the free energy difference ΔG between the pseudosolvent and pure water. We need to develop a quantitative relation between ΔG (which is taken to represent through its magnitude all the essential characteristics of the pseudosolvent) and the actual chemical composition of the pseudosolvent. The free energy difference ΔG can be related to the actual chemical composition of the pseudosolvent using thermodynamic models and data (entirely independent of the polymers) available in the literature for surfactant and electrolyte solutions, as detailed in this section. ΔG can be calculated for different surfactant and electrolytes as:

In this manner, the actual composition of the pseudosolvent can be related to the free energy difference ΔG and thereby to the characteristic energy parameter of the pseudosolvent.

As mentioned earlier, the pseudosolvent consists of surfactant molecules, any electrolyte added and water. The surfactant molecules are present both in their singly dispersed state as well as in the form of micellar aggregates. The pseudosolvent can be thought as a mixture of water (component 1) in its pure water reference state with the other components, electrolyte counterion (component 2), electrolyte coion (component 3), surfactant counterion (component 4) and surfactant coion (component 5) in their infinitely dilute reference states. Since components 2 and 3 come from the salt and components 4 and 5 come from the surfactant, their mole fractions x or molar concentrations C are related as x2 = x3 and x4 = x5, or equivalently, C2 = C3 and C4 = C5. Expressions for estimating the magnitude of ΔG are developed in this section.

4.1. Water + Electrolyte Systems

For the aqueous electrolyte solutions, we adopt the treatment of Kawaguchi et al [

27] formulated based on the Analytic Solution of Group (ASOG) model [

28] to calculate the activity of the components. In this treatment, the electrolyte solution is considered to consist of free water molecules (W), hydrated cations (C) and hydrated anions (A). The electrolyte is assumed to be dissociated completely to produce the cations and the anions with which water molecules are bound. The structure of the hydrated ion is determined by the number of hydration water molecules around it. A hydration water molecule is distinguished from a free water molecule because the water of hydration is tightly bound such that its motion and intramolecular states are different from those of the free water. The hydrated cation (n

C water molecules and a cation) and the hydrated anion (n

A water molecules and an anion) are treated as the two solute components present in the solvent water. Using this visualization, the activities of the components of the electrolyte solution can be viewed as composed of (i) the ideal entropy of mixing, (ii) an excess entropic contribution arising from the presence of the hydrated anions, the hydrated cations, and the free water molecules, described using the Flory-Huggins expression [

14] and (iii) an enthalpic contribution arising from the interactions between the free water and the hydration water molecules that surround the ions. The long-range ion-ion electrostatic interactions were found to be relatively small and therefore neglected in the present study. Therefore, the activity of component i can be written as

where

is the mole fraction of component i (i refers to free water, hydrated cation and the hydrated anion),

is the activity coefficient and

and

are the excess entropic and enthalpic contributions due to the non-idealities.

The expression for the excess entopic contribution to the activity coefficient is given by the ASOG model [

27] as follows:

In Equation (4),

is the mole fraction of component i in the mixture, with the superscript h denoting that the water of hydration is treated as an integral part of the species.

is the number of atoms (other than hydrogen) in the component i and equals 1, (

+ 1), and (

+ 1), for free water, hydrated cation and hydrated anion respectively. Accounting for the hydrated water surrounding the ions, the mole fractions of free water (

), hydrated electrolyte cation (

) and hydrated electrolyte anion (

) are given by:

where

,

and

are the actual mole fractions of the water, the electrolyte cation, and the electrolyte anion in solution. If we consider only a water - electrolyte solution, in the notations introduced for all components of the pseudosolvent,

=

,

=

, and

=

. Equation (5) refers to a single cation and a single anion, but if there are multiple distinct ions, they can be accounted through additional terms for each distinct ion.

The enthalpic contribution to the activity coefficient in the ASOG model [

27] is expressed as:

where

is the number of interacting groups of kind k in component i,

is the activity coefficient of the interacting group k in the mixture,

is the standard state activity coefficient of group k. and

is the group fraction of group k. The expression for the activity coefficient for group k,

, follows the Wilson model [

29].

There are only two interacting groups in this system, namely free water (denoted by subscript k = OH) and the hydrated water (k = OH*) since the interaction between water molecules and ions is entirely accounted for, solely through this hydration. Each component has only one kind of group in it, k = OH in free water and k = OH* in hydrated cation and in hydrated anion. The group activity coefficients are given [

27] by

In Equation (7),

and

are the Wilson interaction energy parameters and

is the group mole fraction of group k. For water, the standard state is pure water and for the anion and the cation, the standard state is the infinite dilution condition. Therefore from Equation (7),

Kawaguchi [

27] has reported the hydration numbers of 11 ions and the interaction energy parameters (

and

) between the free water denoted by OH and the hydration water denoted by OH*. These parameter estimates were obtained by correlating the activities of water in electrolyte solutions very accurately, taking

in Equation (6) as 1.6 for free water,

for the hydrated cation and

for the hydrated anion [

27,

30]. For 14 electrolyte solutions with 1:1 and 2:1 electrolytes, the activities of water calculated by ASOG model using these optimized parameters were found to deviate on the average by less than 1% from the experimental data [

31] , for salt concentrations of up to 5 molality [

27]. Therefore, we directly make use of the parameter estimates reported in Kawaguchi’s work. The interaction energy parameters

and

where OH denotes a free water and OH* a hydration water were determined to be 1.82 and 1.78, respectively [

27,

30]. Note that the interaction parameters between identical groups will be unity, that is

=

= 1. The values of the hydration numbers

and

optimized by Kawaguchi by fitting the water activity data are presented in

Table 3. The value of

decreases with the increase of ionic radius. This tendency qualitatively coincides with that anticipated from the literature [

32].

In the Kawaguchi treatment of electrolyte solutions, the hydrated anion and cation are taken as the distinct chemical species to develop expressions for the activity coefficients. But in the pseudosolvent model, we treat the electrolyte ions in the unhydrated state as the components. Therefore, while writing an expression for the free energy difference ΔG between the pseudosolvent composed of water + electrolyte and water, we should introduce a correction term ΔG

ref to account for this difference in the reference states. On this basis, the free energy difference ΔG between the pseudosolvent composed of water + electrolyte and pure water can be written as

The correction term ΔG

ref accounts for the change in energy when unhydrated ions become hydrated with associated water molecules. This process involves breaking of water-water hydrogen bonds and replacement by ion-dipole interactions between the ion and water. The corresponding energy changes cannot be unambiguously estimated and we have assumed a value of 5000 cal/mole based on typical magnitudes for hydrogen bonding energies (which can range between 2 to 10 kcal/mole) and ion-dipole interactions reported in the literature. We present computed results that show the sensitivity of the calculated free energy difference ΔG between the pseudosolvent and water, to variations in this assumed value. All other parameters for calculating ΔG in Equation (9) have been established and validated by Kawaguchi [

27] based on accurate fitting of water activity data for numerous electrolyte solutions over a wide range of concentrations.

4.2. Water + Surfactant Systems

The surfactant solution is composed of water (component 1), surfactant counterion (component 4) and surfactant coion (component 5). The formation of micelles in the solution can be formally represented by the law of mass action as

where S

- represents the free surfactant ion (representing an anionic surfactant and can be similarly written for cationic surfactants), A

+ represents the free counterion, m is the aggregation number of the micelle, n is the number of counterions bound to the micelle surface. Below the critical micelle concentration (CMC), the surfactant molecules are present mostly in the singly dispersed form, and above the CMC the added surfactant molecules appear as micellar aggregates (denoted by the subscript mic). The singly dispersed surfactant is completely dissociated into surfactant counterion (denoted as 4S) and surfactant coion (denoted as 5S). The activity of the surfactant in solution is equal to the activity of the singly dispersed surfactant because of the monomer-micelle equilibrium.

The free energy difference ΔG between the surfactant solution (pseudosolvent) and pure water can be written similar to Equation (9), in the form

where the superscript S is added to indicated that these activity coefficients appear in surfactant solutions. In Equation (11),

and

refer to the mole fraction and activity coefficient for micelles. The monomer-micelle equilibrium, Equation (10), implies that the micelle activity can be related to the monomer activity in the form

Further, the concentration of singly dispersed surfactant and micelles can be related to the total concentration via the mass balance

Introducing Equations (12) and (13) into Equation (11), we get

The amount of the free surfactant ions

can be estimated from the critical micelle concentration, CMC. The mole fraction of surfactant in the solution near the CMC is generally quite small and hence the total moles in 1 liter of solution can be approximated as 55.5 moles based on water alone. Therefore, with the CMC expressed as a molar concentration (mole/liter), we can estimate

The CMC of homologous straight-chain ionic surfactants in aqueous medium, in the absence of any added salt (C

2 = 0), displays a dependence on the number of carbon atoms N in the hydrophobic chain in the form

where A and B are constants [

33].

The number of counterions binding on the micelles depends on the concentration of counterions in the solution. The binding of counterions on the micelles is assumed to follow the simple Langmuir adsorption isotherm. Correspondingly, the degree of dissociation of the micelle, denoted by α, can be written as

In equation (17), α* is the degree of dissociation of micelles in infinitely dilute solution, is the Langmuir adsorption equilibrium constant (liter/mole) for counterion binding to micelles, I is the ionic strength of the solution, are the mole fractions and are the molar concentrations of the counterion and coion of the free surfactant, respectively and is the molar concentration of micelles of aggregation number m. Below the CMC, . Above the CMC, = CMC/55.5 and .

In the absence of any added electrolyte, the ionic strength is determined by the concentration of the singly dispersed surfactant which is dissociated into surfactant coion and surfactant counterion (the first two terms in the expression for I) and the micelles which contain (αm) multiple charges (the last term in the expression for I). It is generally assumed that the charges on the micelles are partially shielded and the shielding factor δ < 1 is introduced to reduce the effect of the micellar charge on the ionic strength of the solution. It has been found that using δ = 1 is not in agreement with the experimentally determined values of activity and osmotic coefficients. For several ionic surfactants δ is estimated to be around 0.5 [

34] and that value is assumed in this work.

The activity coefficient of the surfactant coion and the surfactant counterion are difficult to determine independently and the experimental measurements usually focus on an average activity coefficient defined as

[

34,

35]. There is very little data in the literature on experimentally determined average activity coefficients for surfactants. The average activity coefficient of the surfactant in the presence of ionic species is attributed mainly to the "salting out" or "salting in" of the hydrophobic group of the surfactant in the aqueous solvent. For nonpolar solutes in aqueous electrolyte solutions of ionic strength I, McDevit and Long [

36] developed a theoretical expression for the activity coefficient in the form,

. This linear dependence is identical to the well-known empirical Setschenow relation [

37], with

designated as the Setschenow constant. Although the equation of McDevit and Long was developed for nonpolar solutes, it has been applied to various polar and polar organic compounds [

38] and nonionic surfactants [

39] as well. To retain simplicity, we will assume that this relation can be applied to calculate the average activity coefficient of the surfactant.

The activity coefficient of water

can then be derived through the Gibbs-Duhem equation. When the molar concentration of the surfactant

is less than the CMC, no micellization occurs. When

is greater than the CMC,

includes contributions arising from the presence of micelles. One thus gets the surfactant contribution to the activity coefficient of water to be

The free energy difference ΔG between the water + surfactant solution (pseudosolvent) and pure water can now be calculated from Equation (14) by introducing Equations (15) to (19) in it.

4.3. Water + Surfactant + Electrolyte Systems

For water-surfactant-electrolyte solutions, the expression for the free energy difference ΔG between the pseudosolvent and pure water can be written by extending Equation (9) for the free energy difference of the water + electrolyte system and Equation (14) for the free energy difference of the water + surfactant system. On this basis, we can write

As mentioned earlier, subscripts 2 and 3 refer to the counterion and the coion of the electrolyte. Subscripts 4 and 5 refer to the counterion and the coion of the surfactant. The

contribution is calculated from Equation (4), the

contribution from equation (6), the

contribution from Equation (18) and the

contribution from Equation (19). The ionic strength I now includes the added electrolyte.

The presence of electrolyte in aqueous solution causes a decrease in the CMC, which will influence the concentrations

and

. The depression of CMC in ionic surfactant solutions is due mainly to the decrease in the thickness of the ionic double layer surrounding the ionic head groups in the presence of the additional electrolyte and the consequent decrease in the electrostatic repulsions between them at the micelle surface. Experimental data [

40] suggest that for ionic surfactants, the effect of the concentration of electrolyte on the CMC is given by,

where a is a constant for a given ionic head group at a particular temperature and is independent of the hydrophobic tail length, and

is the concentration of the added electrolyte in mole per liter. Introducing Equation (16) into equation (22) we can calculate the CMC for a surfactant with N carbon atoms in the hydrophobic tail at an added electrolyte concentration of

from,

4.4. Estimation of Thermodynamic Parameters from Literature

For calculating the free energy difference ΔG between the pseudosolvent (composed of water-surfactant-electrolyte) and the pure water using Equation (20), the values of the following thermodynamic parameters for the surfactant-electrolyte solutions are needed.

- (a)

A and B in Equation (16) for the hydrophobic tail length dependence of the CMC

- (b)

a in Equation (22) for the ionic strength dependence of the CMC

- (c)

and α* in Equation (17) for counterion binding at micellar surface

- (d)

in Equation (18) for the activity coefficient of surfactant.

The parameters A and B in Equation (16) for calculating the critical micelle concentration as a function of surfactant chain length, in the absence of any added salt, are 3.45 and 0.69 for alkyl sulfates, and 3.68 and 0.67 for alkyl sulfonates and alkylbenzene sulfonates [

40]. The parameter a in Equation (22) to calculate the effect of salt on the CMC for sodium alkyl sulfate and sulfonates is 0.458 [40, 41]. All these parameter values are based on the CMC expressed in molar concentration (moles/liter). The CMC of surfactants with different hydrocarbon chain lengths and at various added salt concentrations can be readily calculated from Equation (23) incorporating the values for A, B, b, N and

.

The micelle aggregation number m appearing in Equations (17) and (23) is taken to be 50 for all surfactants considered here to avoid adding additional parameters. Changing the value of m does not significantly affect the computed free energy differences or the phase diagrams. The adsorption constant

in Equation (17) for the counter-ion adsorption at micellar surface is taken as 1.0 (mole/liter)

-1 and α* in Equation (17) is taken to be 0.5. Both the values of

and α* are chosen to agree with the experimental observation that the fraction of counter-ions dissociation on the micelle surface for alkyl sulfonates and alkyl sulfates is in the range of 0.3 to 0.6 for the surfactant and electrolyte concentrations studied [

33,

41,

42].

For alkyl sulfonate and alkyl sulfate surfactants, experimental average activity coefficient data are not available for the homologous series of surfactants. Experimental data for short chain alkyl carboxylates [

35] suggest that the mean molar activity coefficients for different carboxylate homologs approach a constant value of -0.25 at their critical micellar concentrations. If this behavior is displayed by the alkyl sulfates and sulfonates, the Setschenow constant

for differing hydrophobic chain lengths can be estimated from the following equation,

For the present study, the value of constant in Equation (24) for alkyl sulfate, alkyl sulfonate and alkyl benzene sulfonate surfactants is chosen as -0.5 since it is in the range of the experimental average activity coefficient for sodium dodecyl sulfate [

34,

42,

43]. Incorporating this constant value of -0.5 and the cmc calculated as described above, the Setschenow constant k

S is determined using Equation (24). The validity of Equation (24) for other surfactants (in other words, whether

at CMC is equal to a constant value for surfactant homologs) needs experimental verification. However, at the present time, due to lack of experimental activity coefficient data for various surfactant homologs, the validity of Equation (24) is assumed and a constant value of -0.5 is assigned to calculate the values of

for alkyl sulfate, alkyl sulfonate and alkyl benzene sulfonate surfactant homologs.

Since the parameters

, α* and

have been assigned values that are reasonable, but without any direct supporting experimental data for the specific molecular systems, we perform parametric sensitivity analysis in

Section 5.4 on how changes in these parameter values affect the calculation of the free energy difference ΔG, and thereby the phase diagram.

5. Phase Behavior Predictions and Construction of Phase Diagrams

5.1. Calculation of the Free Energy Difference Between the Pseudosolvent and Water

The free energy difference ΔG defined in Equation (20) has been calculated for sodium pentyl sulfonate (R5SO3Na), sodium decyl sulfate (R10SO4Na), sodium dodecyl sulfate (R12SO4Na), sodium tetradecyl sulfate (R14SO4Na), TRS 40 HEW (RB17SO3Na), TRS 10-410 HEW (RB24SO3Na), and TRS 18 HEW (RB34SO3Na) at different salt and surfactant concentrations using the parameter values provided above. For illustrative purposes, we have plotted in Figure 6, the calculated values of ΔG for the pseudosolvent containing sodium pentyl sulfonate, sodium dodecyl sulfate and TRS 40 as surfactants and sodium chloride as the electrolyte, in the concentration range of interest. Similar plots have been constructed for each of the surfactant mentioned above and, in all cases, using NaCl as the electrolyte.

Figures 5 discussed earlier in

Section 3.3 shows the relation between the characteristic energy parameter,

of the pseudosolvent, and the free energy difference ΔG between the pseudosolvent and water, calculated from Equation (A-1), in the framework of the lattice fluid theory.

Figure 5 shows that as

increases, ΔG decreases. The implication of this for the calculated results shown on Figure 6 is that the characteristic energy parameter

of the pseudosolvent increases as the concentration of surfactant and/or salt is increased. Since the increase in

results in phase separation in polymer solutions, we have the general conclusion that an increase in the concentration of surfactant and/or salt will lead to phase separation in aqueous solutions containing polymers. For any concentration of salt and surfactant, the value of ΔG can be found from Figure 6, then the corresponding value of

can be read off from

Figure 5, and thus one can obtain the equation of state parameters (

,

, r) of the pseudosolvent.

5.2. Construction of Ternary Phase Diagram from Theory Based on iso-ΔG values

To construct the ternary phase diagram for any polymer - pseudosolvent system, we start from

Figure 4 constructed for the polymer of interest (in this case, PEO). For a given polymer molecular weight and concentration, one can find the value of the characteristic energy parameter

when phase separation would occur from

Figure 4. The corresponding free energy difference ΔG is then determined from

Figure 5, which is a universal relation independent of the polymer. All water-surfactant-electrolyte compositions with free energy differing from water by the same magnitude of ΔG will lie at the polymer-pseudosolvent phase boundary, allowing us to construct the phase diagram in the actual compositional space of polymer + surfactant + electrolyte + water system. These iso-ΔG surfactant + electrolyte + water compositions are found from

Figure 6.

Ternary phase diagrams can thus be constructed in this manner by combining the results for polymer + water system such as in

Figure 4 obtained from the lattice fluid theory, the universal relation between the characteristic energy of the pseudosolvent and the free energy difference obtained in the framework of the lattice fluid model shown in

Figure 5 and the relation between and the actual composition of the solution obtained from the polymer independent models of surfactant + electrolyte systems, as shown on

Figure 6. The ternary phase diagram constructed in the manner are shown on

Figure 7 for polyethylene oxide + sodium dodecyl sulfate + NaCl + water system at two concentrations of the electrolyte, NaCl.

One can observe the influence of polymer molecular weight, polymer concentration, surfactant concentration, and electrolyte concentration from the ternary diagram. Both Figures 7a and 7b show that increasing surfactant concentration leads to phase separation. Comparing the two figures, we see that increasing the salt concentration reduces the single phase compositional domain. Similarly, increasing the equivalent weight of the surfactant (not shown in this figure) also decreases the single phase compositional domain.

In addition to predicting the effect of salt concentration, surfactant concentration, and the equivalent weight of surfactant on the phase behavior of the polymer-surfactant solutions in agreement with known experimental behavior, the pseudosolvent model also correctly describes the effect of polymer molecular weight and polymer concentration. Both Figures 7a and 7b show that for high molecular weight PEO samples, the phase behavior is not changed appreciably by the change in polymer concentration while for the lower molecular weight PEO, there is a change with polymer concentration. One can observe that as the polymer concentration is changed, the surfactant concentration at the phase boundary remains practically unchanged in both figures at the given salt concentrations. Both figures show that the compositional space of the single phase domain is not much altered by the polymer molecular weight, as long as the polymers have high molecular weights.

Both Trushenski et al. [

7,

8] and Pope et al. [

10] found that the influence of polymer concentration (in the range 100 to 1500 ppm) and polymer molecular weight (for molecular weights larger than 400K)on the phase behavior of the polymer-surfactant-electrolyte systems were negligible. Kalpakci [

6] made the same observation and further noted that as the high molecular weight polymer was degraded using an ultrasonic mixer and/or orifice mixer, the phase stability of the system improved and the aqueous solution remained stable at higher salt and surfactant concentrations.

Our calculated results in

Figure 7 are in agreement with these experimental observations. For the high molecular weight polymers, PEO (4M) and PEO (300K), for the polymer concentration in the range of 100 ppm to 1500 ppm (equivalently 0.01 wt% to 0.15 wt%), the phase behavior is the same, namely the phase boundaries have the same concentration of the surfactant and electrolyte. In contrast

Figure 7 shows that for the lower molecular weight polymer, PEO (14K), the higher the concentrations of surfactant and salt, at which phase separation would occur. This model prediction is in agreement with the experimental findings of Kalpacki that decreasing polymer molecular weight during ultrasonication resulted in enhanced phase stability at higher surfactant and salt concentration.

5.4. Construction of Phase Diagram Using a Single Experimental Data

In the absence of polymer equation of state parameters or the binary parameters of the polymer-water system, it will not be possible to calculate the phase diagram similar to

Figure 4. In the absence of knowledge of

values, it is not possible to construct the ternary phase diagram such as in

Figure 7. However, for these situations, we suggest a simple approach to constructing the phase diagram similar to

Figure 2. If we know from experiments one composition lying at the phase boundary (any one experimental point in

Figure 2), we can calculate the corresponding ΔG of the surfactant + electrolyte + water system from

Figure 6 (which can be constructed for that surfactant + electrolyte system). Various combinations of surfactant + electrolyte systems can give rise to identical magnitudes of ΔG (or to identical values of the characteristic energy parameter

) are expected to have similar phase behavior in the framework of the pseudosolvent model. All surfactant + electrolyte + water systems having iso-ΔG values can be identified from

Figure 6 in order to construct the phase diagram without requiring any information about the polymer. Illustrative phase diagrams calculated in this manner, using one experimental phase composition data lying at the phase boundary from

Figure 2 are shown on

Figure 8 for the three polymers considered in this work.

For example, one of the solution compositions on the phase boundary for the Pusher 700-R

12SO

4Na system contains 0.76 wt % surfactant and 2.0 wt % NaCl. It can be found from

Figure 6 that the free energy difference ΔG for this pseudosolvent is -33.6 cal/mol. This implies, in the framework of the pseudosolvent model, that all compositions of the pseudosolvent with the free energy difference of -33.6 cal/mol, which can be found from

Figure 6, must lie on the phase boundary for the Pusher 700 - surfactant- electrolyte system. The iso-ΔG also occurs at 0% NaCl and 2.82 wt% surfactant and 4% NaCl and 0.35 wt% surfactant for sodium dodecyl sulfate, providing other compositions lying at the phase boundary. This procedure has been used for the three polymer systems, to establish their predicted phase boundaries as shown by the continuous lines in

Figure 8. The predicted and experimental phase boundaries (shown as points) are found to be in reasonable agreement.

The most significant feature of the pseudosolvent model is thus the possibility of constructing phase diagrams using knowledge of just one experimental phase composition lying at the phase boundary, without requiring any information about the polymer. Using this one experimental point available for any one surfactant and/or electrolyte, one can theoretically establish the phase boundary for the polymer with any other surfactant and electrolyte systems.

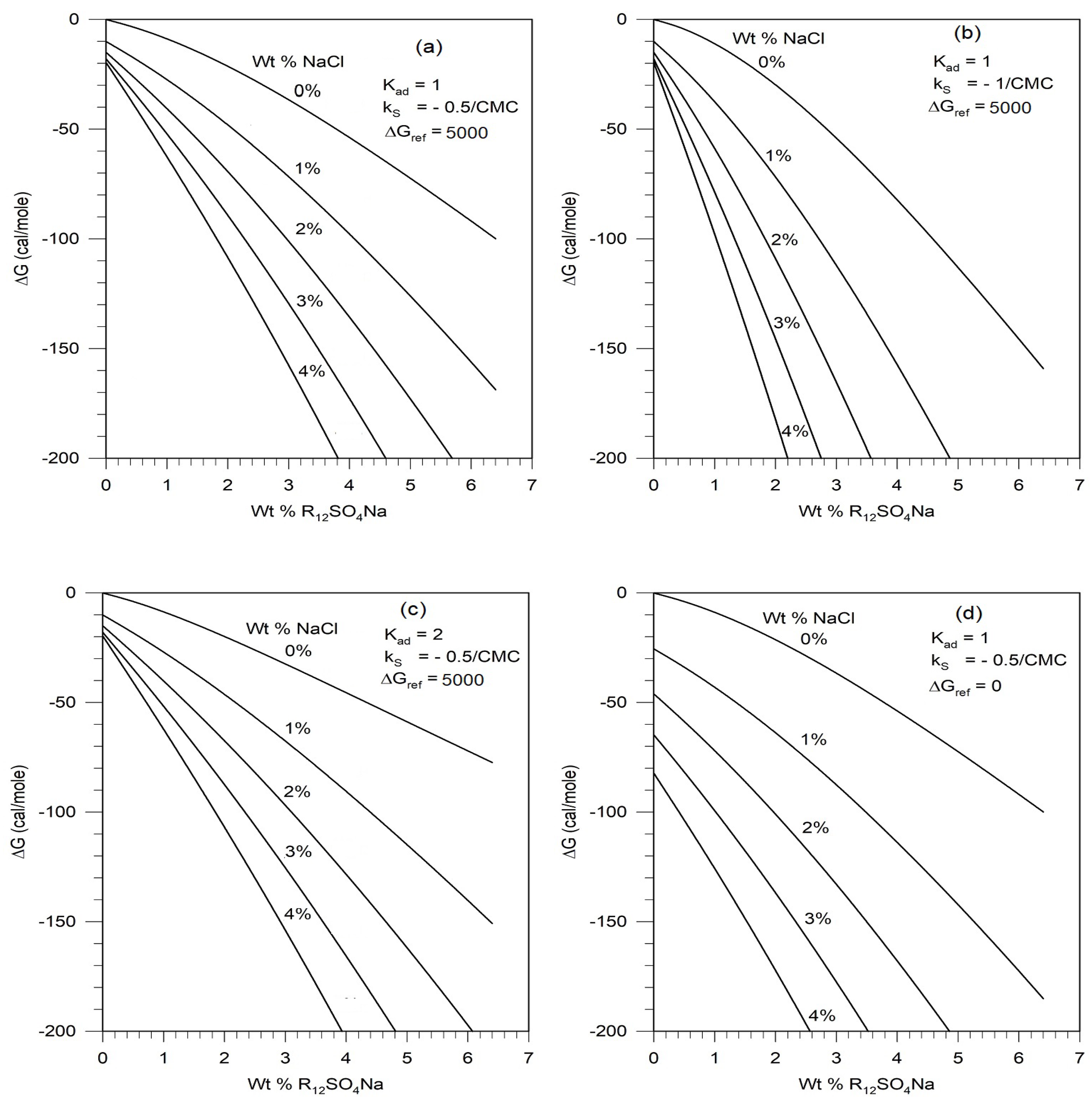

5.4. Assessment of Parametric Sensitivity to Predicted Results

To carry out predictive computations we have used estimated parameter values where direct experimental data for specific molecules are not available. The choice of values for the degree of dissociation on micelle surface at infinite dilution α* and the shielding parameter δ are reasonable based on available data for multiple surfactants. In contrast, the counterion adsorption equilibrium constant K

ad, the Setschenow constant to describe salt effect on surfactant activity k

S and the correction term ΔG

ref to account for the consideration of hydrated ions as the actual species in place of the unhydrated ions have all been assigned values based on limited or no direct experimental data. Therefore, we have performed illustrative calculations to assess the sensitivity of the free energy calculations to variations in these parameter values. The results are shown on

Figure 9.

Changes in the values of K

ad and k

S only change the free energy values to a small extent and therefore the phase diagrams will change only marginally. The correction term ΔG

ref does not affect the dependence of the free energy curve on the surfactant concentration but displaces the curves up or down, that is, to smaller or larger ΔG magnitudes. This will have the effect of shifting the phase boundary curves in

Figure 8 up or down. For quantitative comparisons of predictions against experiments, it would be possible to update the present calculations whenever the currently unavailable surfactant parameter values are determined experimentally

The free energy calculations show that the predominant contributions come from the ideal free energy of mixing and the non-ideal free energy contribution arising from the salt effect on the surfactant. All other terms are practically unimportant for the concentrations of salt and surfactant considered in this study, even though they have been rigorously included here. Therefore improved estimation of the Setschenow constant kS will assure that true predictions can be obtained.

6. Conclusions

Phase separation in four-component systems made up of polymer + surfactant + electrolyte + water, is treated by introducing the concept of a pseudosolvent. This concept transforms the problem to that of a pseudo-binary solution and thus avoids the unmanageability of the thermodynamic description of phase stability criteria in four-component systems. The pseudosolvent is taken to be made up of water, electrolyte, singly dispersed surfactant molecules, and micellar aggregates. The polymer molecule is regarded as the solute. The lattice fluid theory is then used to describe the phase behavior of the polymer + pseudosolvent system. All important characteristics of the pseudosolvent are assumed to be described by a single parameter, namely the characteristic energy parameter . This is an extra thermodynamic postulate underlying the pseudosolvent treatment. This characteristic energy parameter of the pseudosolvent is related to the free energy difference ΔG between the pseudosolvent and water. In order to calculate the free energy difference ΔG between the pseudosolvent and water, electrolyte solution theory and surfactant solution theory available in the literature have been used.

The free energy calculations show that the main contributions to the free energy difference ΔG between the pseudosolvent and water come from the ideal free energy of mixing and the non-ideal free energy contribution arising from the salt effect on the surfactant. All other terms are practically unimportant for the concentrations of salt and surfactant considered in this study. These terms which have been rigorously modeled in this work could become important at higher concentrations of electrolytes when studies focus on somewhat smaller polymer molecular weights.

Ternary phase diagrams have been constructed by combining the value of the characteristic energy parameter

when phase separation would occur from

Figure 4, the polymer-independent universal relation between

and the free energy difference ΔG between the pseudosolvent and water shown on

Figure 5, and the dependence of ΔG on the surfactant-electrolyte composition shown on

Figure 6. The ternary phase diagrams correctly show agreement with the observations in the literature that the phase behavior of polymer-surfactant solutions show only slight dependence on molecular weight of the polymer for high molecular weight polymers, they are not very sensitive to polymer concentrations for high molecular weight polymers at low polymer concentration range, the phase stability increases significantly as the polymer molecular weight is drastically decreased and the compositional domain of the single phase region decreases with increasing polymer molecular weight, increasing surfactant equivalent weight, increasing surfactant concentration and increasing added salt concentration.

More interestingly, we present an approach predicting the phase behavior without any information about the polymer, as long as a single experimental composition data for a system lying on the phase boundary is known. Using the appropriate parameter values in the pseudosolvent model, the free energy difference ΔG between the pseudosolvent and water is calculated. All other chemical compositions required to complete the phase boundary are then determined from surfactant-electrolyte compositions having iso- ΔG values. The comparison between the phase boundaries calculated in this manner from the pseudosolvent model and the experimental phase boundaries show satisfactory agreement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.N. and J.S.; experiments, J.S.; numerical computations, J.S.; analysis, J.S. and R.N.; writing—original draft preparation, J.S. and R.N.; independent numerical computations, R.N.; writing—review and editing, R.N.; supervision, R.N.; project administration, R.N.

Funding

This research received no directed external funding.

Acknowledgments

Support from The Pennsylvania State University for conducting the research and from the US Army CCDC Soldier Center for preparing the manuscript is gratefully acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Lattice Fluid Theory

A.1 Equation of State for Pure Fluids

The Lattice Fluid theory developed by Sanchez [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13] differs from other lattice models in the literature such as Flory-Prigogine equation of state model, by allowing for some of the lattice sites to be vacant. For a system consisting of N molecules each of which occupies r sites (a r-mer) and N

o vacant lattice sites (holes), the reduced Gibbs energy is given by

where the reduced variables are defined as

and ω is a molecular constant associated with molecular size and flexibility while k is the Boltzmann constant. The corresponding equation of state for a pure fluid is obtained from the condition,

and is given by

The equation of state parameters can be the characteristic pressure P*, characteristic temperature T* and the characteristic volume V*, or alternately, the characteristic energy ε*, the characteristic lattice size v* and the component molecular size r.

A.2 Estimation of Equation of State Parameters

The lattice fluid theory is applicable to liquid and gas phases. Therefore, the equation of state parameters for pure fluids can be estimated by using experimental liquid phase P-V-T data or by using the saturation vapor pressure data. By fitting available vapor pressure data to the equation of state, Equation (A-4), Sanchez obtained the equation of state parameters for water (the solvent is designated by subscript 1), to be:

For polymers, vapor pressure data are not generally available since high molecular weight polymers have negligible vapor pressures. Therefore the equation of state parameters are usually determined by fitting the experimental density data above the glass transition temperature to the equation of state. An alternate approach is to use information available at a single temperature for the density ρ, thermal expansion coefficient α and the isothermal compressibility β. From the equation of state, one can get expressions for α and β as follows:

For high molecular weight polymers (

) and at atmospheric pressure (

), the equation of state and the expressions for α and β reduce to ,

We start with experimental data for ρ, α, and β, available at one temperature. By fitting them to Equation (A-7), the equation of state parameters for the polymer can be estimated. Using available data for ρ, α, and β at 25

oC, we determine the equation of state parameters for PEO to be,

Note that r

2 is obviously dependent on the molecular weight M

2 of the polymer as shown in Equation (A-8).

A.3 Equation of State for Polymer Solution

In the framework of the lattice fluid theory, the reduced Gibbs energy of a polymer solution is given by

where

is a molecular constant associated with molecular size and flexibility for component i and is independent of the composition. In Equation (A-9), combining rules are invoked to describe the interaction energy, the closed packed volume per lattice site and the characteristic molecular size r, as a function of the mixture composition, represented by the volume fraction

. Denoting the volume fractions of the solvent and the polymer by

and

, respectively, the following combining rules are adopted:

Two binary parameters ξ and δ have been introduced to represent deviations from “ideal” behavior of the dissimilar lattice occupants.

The corresponding equation of state for the polymer solution (polymer-solvent mixture) has a form identical to that for pure fluids and is given by

A.4 Estimation of Binary Parameters by Fitting Water Activity

The binary parameters ξ and δ are determined by fitting relevant experimental data for mixtures such as the activity or the heat and volume changes on mixing data. Since we are interested in phase behavior, we use the solvent (water) activity data to estimate the binary parameters. The activity of the solvent is derived from the mixture free energy and is given by

where

is given by

For a liquid mixture at atmospheric pressure, the two pressure terms in Equation (A-14) can be ignored. The variable

is calculated as follows:

All the solvent (water) and polymer (PEO) pure component parameters have already been estimated as described in Appendix A.2. By fitting the water activity data to Equations (A-13) to (A-18), the two unknown binary parameters are determined to be ξ = 1.023 and δ = - 0.25 for the PEO-water binary mixture.

A.5 Criteria for Phase Stability

At constant temperature and pressure, a necessary and sufficient condition for miscibility of a binary mixture over the entire composition range is for the Gibbs free energy per mole of the mixture to be a convex function of composition, i.e.,

This condition guarantees that the free energy of mixing is negative. The criteria for the mixture to be stable has been derived by Sanchez as,

where

The expression for X

21 in appearing in Equations (A-21) and (A-23) is obtained by interchange of the indices 1 and 2 in Equations (A-14) to (A-17) for X

12. Given the equation of state parameters for the polymer (PEO), and two of the equation of state parameters for the pseudosolvent (taken to be the same for water), and the binary parameters (taken to be the same for polymer-water), one can numerically solve Equations (A-14) to (A-23), to determine the characteristic energy parameter for the pseudosolvent when the stability criteria, Equation (A-20), is met, for any given polymer molecular weight and polymer concentration (volume or weight fraction). The calculations are repeated for various concentrations of the polymer and the results are shown on

Figure 4 of the main text. The calculations are also repeated for polymers of different molecular weights and the corresponding results are plotted in the same figure.

Nomenclature

| A |

Parameter in the equation for the CMC dependence of on chain length |

| a |

Parameter in the equation for the CMC dependence on salt concentration |

| a |

Parameter defined in Equation (A-16) |

| ai |

Activity of component i |

| aOH/OH*, aOH*/OH |

Wilson interaction parametersbetween hydrated water and free water |

| B |

Parameter in the equation for the CMC dependence of on chain length |

| b |

Parameter in the equation for the CMC dependence on salt concentration |

| b12 |

Parameter defined in Equation (A-17) |

| Ci |

Molar concentration of component i |

| CMC |

Critical micelle concentration, expressed as molar concentration |

| c12 |

Parameter defined in Equation (A-18) |

| G |

Free energy |

|

Reduced free energy |

| ΔG |

Free energy difference between pseudosolvent and water |

| ΔGref |

Correction to free energy change to account for the different reference states for electrilyte ions |

| I |

Ionic strength of the solution |

| Kad |

Adsorption equilibrium constant for counterion binding |

| k |

Boltzmann constant |

| kS |

Setschenow constant |

| M |

Molecular weight |

| M |

Micelle aggregation number |

| mi |

Molarity of component i |

| N |

Chain length of surfactant tail |

| N |

Number of molecules |

| No |

Number of vacant lattice sites |

| NA |

Avogadro number |

| n |

Number of counterions bound to the micelle |

| nC |

Hydration number of cation |

| nA |

Hydration number of anion |

| ni |

Number of moles of component i |

| P |

Pressure of system |

|

Reduced pressure |

|

Characteristic pressure parameter |

|

Characteristic pressure parameter of component i |

|

Group fraction of group k |

| R |

Universal gas constant |

| ri |

Number of sites occupied by component i |

| T |

Temperature of system |

|

Reduced temperature |

|

Characteristic temperature parameter |

|

Characteristic temperature parameter of component i |

| V |

Volume of system |

| V* |

Hard-core volume parameter |

| v |

Volume per segment |

|

Reduced volume |

|

Characteristic lattice site hardcore volume parameter for component i |

| xi |

Mole fraction of component i |

|

Mole fraction of component i including water of hyration |

| X12 |

Variable defined in Equation (A-15) |

| Zi |

Number of charges in species i |

| Greek Letters |

|

| α |

Thermal pressure coefficient of polymer |

| α |

Degree of counterion dissociation on micelle surface |

| α* |

Degree of counterion dissociation on micelle surface at infinite dilution |

| β |

Isothermal compressibility of polymer |

|

Activity coefficient of the interacting group k in the mixture |

|

Standard state activity coefficient of group k |

|

Activity coefficient of component i |

|

Activity coefficient of component i due to excess entropic contribution |

|

Activity coefficient of component i due to enthalpic contribution |

|

Activity coefficient contribution due to surfactant for component i |

|

Average activity coefficient of surfactant |

|

Total number of fundamental groups in species i |

| δ |

Polymer-solvent binary volume parameter correcting deviation from arithmetic mean |

| δ |

Shielding parameter for micelle surface charge |

|

Characteristic energy parameter of solvent (water) |

|

Characteristic energy parameter of pseudosolvent |

|

Characteristic energy parameter of polymer |

|

Chemical potential of component 1 |

| ν |

Ratio of characteristic hard core volumes appearing in Equation (A-16) |

|

Number of atoms other than H in component i |

|

Number of interacting groups of kind k in component i |

| ξ |

Polymer – solvent binary energy parameter correcting deviation from geomteric mean |

| ρ |

Density |

|

Reduced density |

|

Characteristic density parameter |

| τ |

Ratio of charcateristic energies appearing in Equation (A-16) |

|

Volume fraction of component i |

|

Interaction parameter defined by Equation (A-14) |

| ψ |

Parameter defined by Equation (A-22) |

| ω |

Molecular constant associated with molecular size and flexibility |

| Superscripts |

|

| h |

Hydration |

| ∞ |

Infinite dilution |

| Subscripts |

|

| 1 |

Water |

| 2 |

Polymer while discussing polymer-solvent systems |

| 2 |

Counterion of electrolyte |

| 3 |

Coion of electrolyte |

| 4 |

Counterion of surfactant |

| 4S |

Counterion of free (singly dispersed) surfactant |

| 5 |

Coion of surfactant |

| 5S |

Coion of free (singly dispersed) surfactant |

| A |

Anion including associated hydrated water |

| C |

Cation including associated hydrated water |

| i |

Component i |

| mic |

Micelle |

| w |

Free water |

References

- Hansson, P.; Lindman, B. Surfactant-polymer interactions. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci., 1996, 1, 604–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, D. O.; Schechter, R. S., Editors. Improved Oil Recovery by Surfactant and Polymer Flooding; Academic Press, New York, 1977.

- Druetta, P.; Picchioni, F. Surfactant−Polymer Flooding: Influence of the Injection Scheme. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 12231–12246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druetta, P.; Picchioni, F. Surfactant-Polymer Interactions in a Combined Enhanced Oil Recovery Flooding. Energies 2020, 13, 6520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamouma, M.; Delbos, A.; Dalmazzone, C.; Colin, A. Polymer Surfactant Interactions in Oil Enhanced Recovery Processes. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 9312–9321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradzielski, M. Polymer–surfactant interaction for controlling the rheological properties of aqueous surfactant solutions. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 63, 101662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trushenski, S. P.; Dauber, D. L.; Parris, D. R. Micellar Flooding - Fluid Propagation, Interaction, and Mobility. Soc. Pet. Eng. J. 1974, 14, 633–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trushenski, S. P. Micellar Flooding: Sulfonate-Polymer Interaction. In Improved Oil Recovery by Surfactant and Polymer Flooding, Shah, D. O.; Schechter, R. S., Eds.; Academic Press, New York, 1977. p.555-575.

- Szabo, M. T. The Effect of Sulfonate/Polymer Interaction on Mobility Buffer Design. Soc. Pet. Eng. J. 1979, 19, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, G. A.; Tsaur, K.; Schecter, R. S.; Wang, B. Effect of Several Polymers on the Phase Behavior of Micellar Fluids. Soc. Pet. Eng. J. 1982, 22, 816–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S. P. , Dispersive Mixing Effects on the Sloss Field Micellar System. SPE J. 1982, 22, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalpakci, B. Flow Properties of Surfactant Solution in Porous Media and Surfactant-Polymer Interactions, Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Chemical Engineering, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sheu, J-Z. Thermodynamics of Phase Separation in Aqueous Polymer-Surfactant-Electrolyte Solution, Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Chemical Engineering, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, 1983.

- Flory, P. J. Principles of Polymer Chemistry. Cornell Univ. Press, Ithaca, 1953.

- Dormidontova, E. E. Role of Competitive PEO-Water and Water-Water Hydrogen Bonding in Aqueous Solution PEO Behavior. Macromolecules 2002, 35, 987–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knychala, P.; Timachova, K.; Banaszak, M.; Balsara, N. P. 50th Anniversary Perspective: Phase Behavior of Polymer Solutions and Blends. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 3051–3065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkandawire, W. D.; Milner, S. T. Simulated Osmotic Equation of State for Poly(ethylene Oxide) Solutions Predicts Tension – Induced Phase Separation. Macromolecules 2021, 54, 3613–3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekiranov, S.; Bruinsma, R.; Pincus, P. Solution behavior of polyethylene oxide in water as a function of temperature and pressure, Phys. Rev. E 1996, 55, 577–585. [Google Scholar]

- Valsecchia, M.; Galindo, A.; Jackson, G. Modelling the thermodynamic properties of the mixture of water and polyethylene glycol (PEG) with the SAFT-γ Mie group-contribution approach. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2024, 577, 113952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, I. C.; Lacombe, R. H. An elementary molecular theory of classical fluids. Pure fluids. J. Phy. Chem. 1976, 80, 2352–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacombe, R. H.; Sanchez, I. C. Statistical thermodynamics of fluid mixtures. J. Phy. Chem. 1976, 80, 2568–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, I. C.; Lacombe, R. H. An elementary equation of state for polymer liquids. J. Polym. Sci., Polym. Lett. Ed. 1977, 15, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, I. C.; Lacombe, R. H. Statistical thermodynamics of polymer solutions. Macromolecules 1978, 11, 1145–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, I. C. Statistical thermodynamics of bulk and surface properties of polymer mixtures. J. Macromol. Sci., Phys 1980, B17, 565–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panayiotou, C.; Sanchez, I. C. Hydrogen Bonding in Fluids: An Equation-of-State Approach. J. Phys. Chem 1991, 95, 10090–10097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcolm, G. N.; Rowlinson, J. S. The thermodynamic properties of aqueous solutions of polyethylene glycol, polypropylene glycol and dioxane. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1957, 53, 921–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi, Y.; Kanai, H.; Kajiwara, H.; Arai, Y., J. Correlation for Activities of Water in Aqueous Electrolyte Solutions Using ASOG Model. J. Chem. Eng. Japan 1981, 14, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronc, M.; Ratcliff, G. A. Prediction of excess free energies of liquid mixtures by an analytical group solution model. Canadian J. Chem. Eng. 1971, 49, 825–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G. M. Vapor-Liquid Equilibrium. XI. A New Expression for the Excess Free Energy of Mixing. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964, 86, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, K.; Tochigi, K., Prediction of Vapor-Liquid Equilibria by the ASOG Method, Kodansha Ltd., Tokyo, Japan 1979.

- Robinson, R. A.; Stokes, R. H. Electrolyte Solutions, 2nd ed., Butterworths, London, 1965.

- Glueckauf, E. The influence of ionic hydration on activity coefficients in concentrated electrolyte solutions. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1955, 51, 1235–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, M. J. Surfactants and Interfacial Phenomena, 3rd Edition, Wiley-Interscience, New York, 2004.

- Burchfield, T. E.; Woolley, E. M. Model for Thermodynamics of Ionic Surfactant Solutions. 1. Osmotic and Activity Coefficients. J. Phys. Chem. 1984, 88, 2149–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauheret, G.; Viallard, A. Activity Coefficients and Micellar Equilibria. I. The Mass Action Law Model Applied to Aqueous Solutions of Sodium Carboxylates at 298.15 K. Fluid Phase Equilibria 1982, 8, 233–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, F. A.; McDevit, W. F. Activity Coefficients of Nonelectrolyte Solutes in Aqueous Salt Solutions. Chem. Rev. 1952, 51, 119–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]