Submitted:

22 May 2024

Posted:

23 May 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Objective

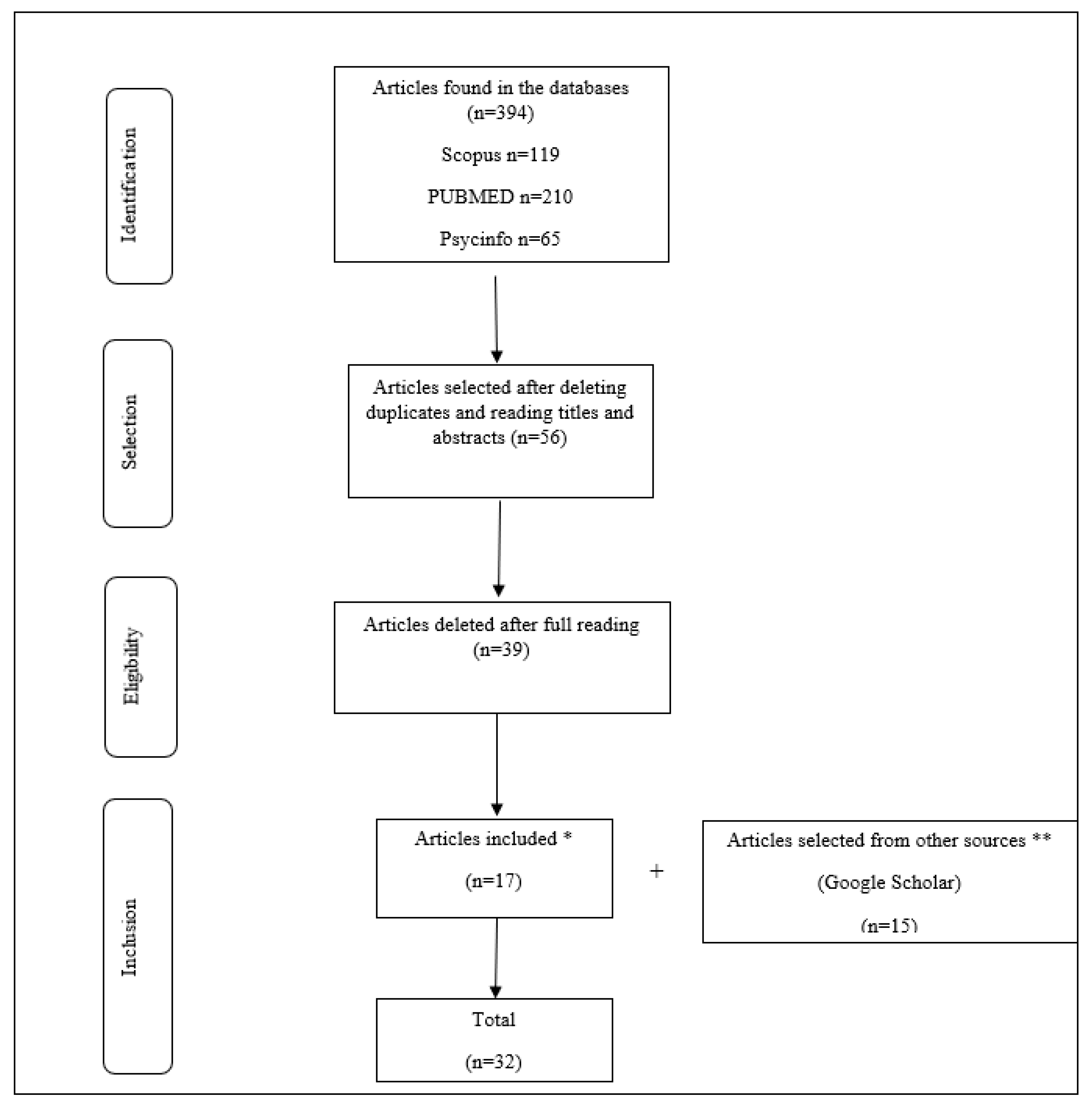

3. Methodology

| Date | Databases | Search strategy | Number of results |

|---|---|---|---|

| 17th June 2023 | APA PsycINFO | Search terms: empathy and morality Search options Expanders - Apply equivalent subjects Restrict by Subject: - empathy Restrict by Subject: - morality Search Modes - Boolean/Phrase |

65 |

| SCOPUS | ALL (“empathy and morality”) AND (LIMIT-TO (EXACT KEYWORD, “Empathy”) OR LIMIT-TO (EXACT KEYWORD, “Morality”)) | 119 | |

| PUBMED | “empathy” and “morality” | 210 | |

| Total | 394 | ||

a) Selection Criteria

b) Data Collection and Analysis

4. Results

| Article | Article type | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|

| Altuna, B. (2018b). Empatía y moralidad. Dimensiones psicológicas y filosóficas de una relación compleja. Revista De Filosofia, 43(2). https://doi.org/10.5209/resf.62029 * |

Narrative review |

“From empathy do not derive ethical principles related to impartiality or equity.” |

| Babcock, S. E., Li, Y., Sinclair, V. M., Thomson, C., & Campbell, L. (2017c). Two replications of an investigation on empathy and utilitarian judgement across socioeconomic status. Scientific Data, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.129 ** |

Study replication + Meta-analysis |

“Individuals with high socioeconomic status tend to make utilitarian decisions partly due to a lack of empathy.” |

| Bloom, P. (2017c). Empathy and its discontents. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 21(1), 24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2016.11.004 * |

Opinion article |

Describes empathy as an “experience of feeling what we think others are feeling” and states that (1) “individuals with low empathy are more rational and less biased moral decision-makers”; (2) “there are reasons to believe that when it comes to making the world better, we are better off without empathy.” |

| Cameron, C. D., Conway, P., & Scheffer, J. A. (2022b). Empathy regulation, prosociality, and moral judgment. Current Opinion in Psychology, 44, 188–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.09.011 * |

Comprehensive review |

Elements other than empathy are necessary for a moral decision. Focus on motivation and inter-relational empathic subjectivity as modulating mechanisms of moral judgment. |

| Churcher, M. (2016c). Can empathy be a moral resource? A Smithean reply to Jesse Prinz. Dialogue, 55(3), 429–447. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0012217316000688 * |

Opinion article |

It defends Adam Smith’s concept of the impartial spectator to argue for the importance of empathy in morality. |

| Cuff, B. M. P., Brown, S., Taylor, L. K., & Howat, D. (2014d). Empathy: A review of the concept. Emotion Review, 8(2), 144–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073914558466 ** |

Narrative revision |

It defines empathy as an emotional (affective) response dependent on the interaction between trait capabilities and state influences. The resulting emotion derives from the perception of the other’s state and its understanding, with the recognition that the origin of the emotion is outside the Self. |

| Decety, J., & Cowell, J. M. (2015c). Empathy, justice, and moral behaviour. Ajob Neuroscience, 6(3), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/21507740.2015.1047055 * |

Narrative revision |

“Empathy produces social preferences that may conflict with justice and equity.” |

| Decety, J., & Cowell, J. M. (2014c). The complex relation between morality and empathy. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 18(7), 337–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2014.04.008 * |

Opinion article |

It alludes to the need to “abandon the term empathy” and use more “precise” concepts, such as “emotional sharing, empathic concern and taking an affective perspective,” to better characterise the relation with morality. |

| Decety, J. (2010c). The neurodevelopment of empathy in humans. Developmental Neuroscience, 32(4), 257–267. https://doi.org/10.1159/000317771 * |

Revision article |

Defends the need to decompose the concept of empathy into sub-components and relate them to specific brain areas for a better understanding of human development |

| Decety, J., & Cowell, J. M. (2018b). The Social Neuroscience of Empathy and its Relationship to Moral Behavior. The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of Forensic Neuroscience, 145–169. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118650868.ch7 * |

Book article |

It argues that empathy can lead to bias in moral judgments and decisions. In evolutionary terms, it claims that empathy is vital in caring for offspring and facilitating group life. |

| Decety, J., & Cowell, J. M. (2014f). Friends or Foes. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 9(5), 525–537. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614545130 * |

Opinion article |

“While there is a relation between empathy and morality, it is not as linear as it might seem. In addition, distinguishing between the different facets of empathy is of the utmost importance, as each uniquely influences moral cognition, predicting differential moral behaviour. |

| Duan, C., & Sager, K. (2018c). Understanding Empathy. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199396511.013.62 * |

Book article |

Addresses the multidisciplinary of empathy and the difficulties of its conceptual definition and alludes to the concept of positive empathy |

| Ferrari, P. F. (2014b). The neuroscience of social relations. A comparative-based approach to empathy and the capacity to evaluate others’ action value. Behaviour, 151(2–3), 297–313. https://doi.org/10.1163/1568539x-00003152 * |

Research article |

It recognises the importance of multiple cognitive and emotional brain networks for empathy and decision-making. |

| Fowler, Z., Law, K. W., & Gaesser, B. (2021). Against empathy bias: the moral value of equitable empathy. Psychological Science, 32(5), 766–779. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797620979965 * |

Research article |

“Participants in two studies thought it was morally correct to empathise with people who were socially closer, although they felt it was morally more appropriate to show similar empathy and independent of social distance.” |

| Isern-Mas, C., & Sureda, A. (2019b). Why does empathy matter for morality? Análisis filosófico. https://doi.org/10.36446/af.2019.310 * |

Opinion article |

“Morality is not reduced to rational judgment, but necessarily presupposes prosocial preferences, motivation, and sensitivity to intersubjective demands.” |

| Johanson, M., Vaurio, O., Tiihonen, J., & Batalla, A. (2020). A systematic literature review of neuroimaging of psychopathic traits. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.01027 ** |

Systematic revision |

“Psychopathy has been associated with a dysfunction of the default mode network that has been linked to poor moral judgments”; “empathy-related brain regions were active in psychopaths when imagining themselves in pain, but inactive when imagining others in pain.” |

| Kauppinen, A. (2017b). Empathy as the moral sense? Philosophia. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11406-017-9816-1 * |

Opinion article |

Holds that a comprehensive, empathic process is a potential source of moral knowledge |

| Lambe, L. J., Della Cioppa, V., Hong, I. K., & Craig, W. M. (2019). Standing up to bullying: a social-ecological review of peer defending in offline and online contexts. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 45, 51–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.05.007 ** |

Systematic revision |

In the context of bullying, “defenders tend to have more empathy and less moral detachment.” |

| Lenzen, L. M., Donges, M. R., Eickhoff, S. B., & Poeppl, T. B. (2021). Exploring the neural correlates of (altered) moral cognition in psychopaths. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 39(6), 731–740. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.2539 ** |

Meta-analysis |

“The antisocial behaviour of psychopaths is due, at least in part, to structural brain dysfunctions of regions associated with moral cognition and emotion”; “Psychopaths have reduced activity in the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC) that has been implicated in social cognitions, which include empathy, morality, and theory of mind.” |

| Markowitz, A. J., Ryan, R., & Marsh, A. A. (2014). Neighbourhood income and the expression of callous–unemotional traits. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 24(9), 1103–1118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-014-0663-3 ** |

Cohort study |

The environment and experience shape behaviour and reward-seeking, leading to the development of more or less adaptive traits and strategies. Insensitive non-emotional traits, including poor empathy, represent a robust hereditary pattern of socio-emotional response associated with an increased risk of persistent delinquent behaviour. |

| Masto, M. (2015). Empathy and Its Role in Morality. The Southern Journal of Philosophy, 53(1), 74–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjp.12097 ** |

Opinion article |

“Empathy is indispensable to our moral lives.” |

| Maxwell, B., & Racine, E. (2010). Should empathic development be a priority in biomedical ethics teaching? A critical perspective. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0963180110000320 ** |

Narrative revision |

Compassionate empathy is a strong motivator of ethical behaviour, but empathic reactions often fall short of appropriate standards of moral judgment because they are so susceptible to familiarity bias |

| Pascal, E. A. (2017b). Being similar while judging right and wrong: The effects of personal and situational similarity on moral judgements. International Journal of Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12448 ** |

Cohort study |

Moral judgment depends on perceived personal and situational familiarity due to two mechanisms: motivational (where the goal is to avoid blame and harm) and non-motivational (through Empathy and Sympathy). |

| Passos-Ferreira, C. (2015). In defence of empathy: A response to Prinz. Abstracta, 8(2), 31–51. ** |

Opinion article |

“Empathy is a crucial element in morality and, in certain circumstances, is our best guide.” |

| Persson, I., & Savulescu, J. (2017b). The moral importance of reflective empathy. Neuroethics, 11(2), 183–193. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12152-017-9350-7 * |

Opinion article |

“Empathy can play an essential role in moral motivation, but it needs to be severely disciplined by other factors – in particular, Reason.” |

| Prinz, J. J. (2011). Is Empathy Necessary for Morality? Oxford University Press eBooks, 211–229. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199539956.003.0014 ** |

Opinion article |

“Empathy is not necessary for the capabilities that are part of basic moral competence.” |

| Redford, L., & Ratliff, K. A. (2017). Empathy and humanitarianism predict preferential moral responsiveness to in-groups and out-groups. Journal of Social Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2017.1412933 * |

Research article |

Claims that empathy favours a preferential morality |

| Schoeps, K., Mónaco, E., Cotolí, A., & Montoya-Castilla, I. (2020b). The impact of peer attachment on prosocial behaviour, emotional difficulties and conduct problems in adolescence: The mediating role of empathy. PLOS ONE, 15(1), e0227627. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0227627 ** |

Cohort study |

It distinguishes emotional and cognitive empathy. It suggests that greater empathic capacity is associated with prosocial and altruistic behaviour and healthy socio-emotional functioning. |

| Simmons, A. T. (2013b). In defense of the moral significance of empathy. Ethical Theory and Moral Practice, 17(1), 97–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10677-013-9417-4 ** |

Opinion article |

“Empathy is necessary and sufficient for morality as long as the individual possesses it in its two dimensions, cognitive and affective.” |

| Slote, M. (2010). The mandate of empathy. Dao-a Journal of Comparative Philosophy, 9(3), 303–307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11712-010-9170-5 ** |

Opinion article |

“Empathy is central to the moral life.” |

| Slote, M. (2016). The many faces of empathy. Philosophia, 45(3), 843–855. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11406-016-9703-1 ** |

Opinion article |

“Empathy is a way of perceiving the moral virtues and vices of the people around us.” |

| Zucchelli, M. M., & Ugazio, G. (2019). Cognitive-emotional and inhibitory deficits as a window to moral decision-making difficulties related to exposure to violence. Frontiers in Psychology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01427 * |

Narrative revision |

“Empathic ability plays a vital role in the development of morality”; “Exposure to violence substantially increases the dysfunction of necessary mechanisms (such as empathy) for morally sound decision making.” |

a) Summary of the Results

- 1)

- Empathy is commonly presented as an exclusively or predominantly emotional process;

- 2)

- Empathy is frequently divided into subtypes;

- 3)

- Empathy is associated with certain specific brain areas;

- 4)

- Empathy is referred to as a source of bias in moral decisions;

- 5)

- It is stated that to be empathetic, one must feel what the other is feeling;

- 6)

- The partiality of empathy is presented as an evolutionary advantage.

5. Discussion

a) We Are Brain

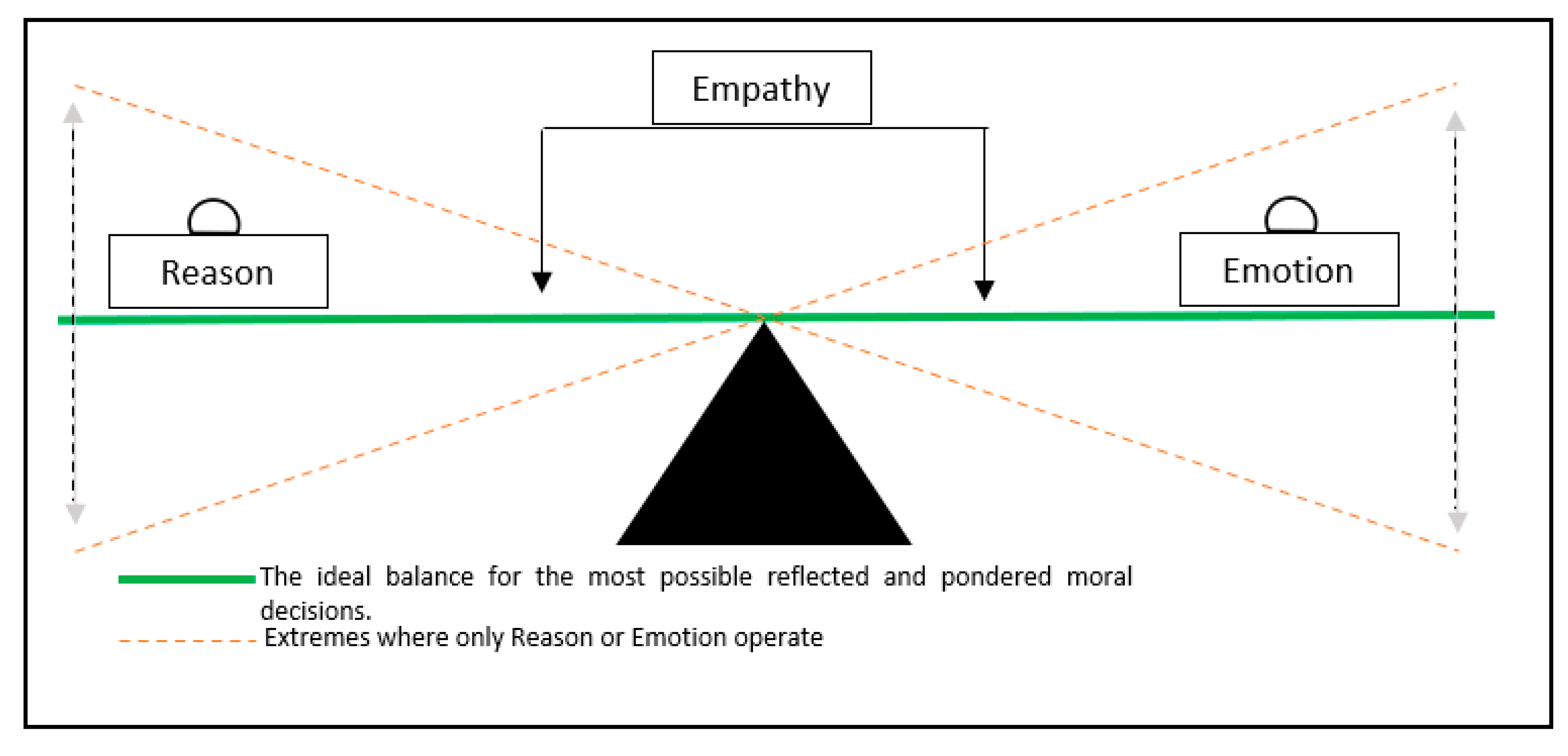

b) Conceptual Model of Empathy and Its Relation with Morality

c) Critical Reflection

6. Conclusion

Research Limitations

References

- Allen, L. (2015, 23rd July). The interaction of biology and environment. Transforming the Workforce for Children Birth Through Age 8 - NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK310546/.

- Blair, R. E. (2007). The amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex in morality and psychopathy. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(9), 387–392. [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, T. L., & Childress, J. F. (2019). Principles of Biomedical ethics. Oxford University Press, USA.

- Churcher, M. (2016). Can empathy be a moral resource? A Smithean reply to Jesse Prinz. Dialogue, 55(3), 429–447. [CrossRef]

- Coplan, A. (2011). WILL THE REAL EMPATHY PLEASE STAND UP? A CASE FOR A NARROW CONCEPTUALISATION. Southern Journal of Philosophy, 49, 40–65. [CrossRef]

- Cuff, B. M. P., Brown, S., Taylor, L. K., & Howat, D. (2014). Empathy: A review of the concept. Emotion Review, 8(2), 144–153. [CrossRef]

- Decety, J. (2010). The neurodevelopment of empathy in humans. Developmental Neuroscience, 32(4), 257–267. [CrossRef]

- Decety, J., & Cowell, J. M. (2014). The complex relation between morality and empathy. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 18(7), 337–339. [CrossRef]

- Decety, J., & Cowell, J. M. (2014b). Friends or foes. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 9(5), 525–537. [CrossRef]

- Decety, J., & Cowell, J. M. (2015). Empathy, justice, and moral behavior. Ajob Neuroscience, 6(3), 3–14. [CrossRef]

- De Vignemont, F., & Singer, T. (2006). The empathic brain: how, when and why? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 10(10), 435–441. [CrossRef]

- Engelen, E., & Röttger-Rössler, B. (2012). Current disciplinary and interdisciplinary debates on empathy. Emotion Review, 4(1), 3–8. [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, P. F. (2014). The neuroscience of social relations. A comparative-based approach to empathy and to the capacity of evaluating others’ action value. Behaviour, 151(2–3), 297–313. [CrossRef]

- Fairchild, G., Toschi, N., Sully, K., Sonuga-Barke, E. J., Hagan, C. C., Diciotti, S., Goodyer, I. M., Calder, A. J., & Passamonti, L. (2016). Mapping the structural organisation of the brain in conduct disorder: replication of findings in two independent samples. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57(9), 1018–1026. [CrossRef]

- Fowler, Z., Law, K. W., & Gaesser, B. (2021b). Against Empathy Bias: The Moral value of Equitable empathy. Psychological Science, 32(5), 766–779. [CrossRef]

- Ganczarek, J., Hünefeldt, T., & Belardinelli, M. O. (2018). From “Einfühlung” to empathy: exploring the relationship between aesthetic and interpersonal experience. Cognitive Processing, 19(2), 141–145. [CrossRef]

- Isern-Mas, C., & Sureda, A. (2019). Why does empathy matter for morality? Análisis Filosófico. [CrossRef]

- Jaspers, K. (2000). Psicopatologia Geral (8th ed.). Atheneu Editora.

- Kauppinen, A. (2017). Empathy as the moral sense? Philosophia. [CrossRef]

- Lenzen, L. M., Donges, M. R., Eickhoff, S. B., & Poeppl, T. B. (2021). Exploring the neural correlates of (altered) moral cognition in psychopaths. Behavioral sciences & the law, 39(6), 731–740. [CrossRef]

- Liberati, Alessandro, Douglas G. Altman, Jennifer Tetzlaff, Cynthia D. Mulrow, Peter C Gøtzsche, John P. A. Ioannidis, Mike Clarke, P. J. Devereaux, Jos Kleijnen, and David Moher. 2009. “The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration.” PLOS Medicine 6 (7): e1000100. [CrossRef]

- Martineau, J. T., Decety, J., & Racine, E. (2019). The Social Neuroscience of Empathy and Its Implication for Business Ethics. Advances in Neuroethics, 167–189. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascal, E. A. (2017). Being similar while judging right and wrong: The effects of personal and situational similarity on moral judgements. International Journal of Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Redford, L., & Ratliff, K. A. (2017). Empathy and humanitarianism predict preferential moral responsiveness to in-groups and out-groups. Journal of Social Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Riccelli, R., Toschi, N., Nigro, S., Terracciano, A., & Passamonti, L. (2017). Surface-based morphometry reveals the neuroanatomical basis of the five-factor model of personality. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, nsw175. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamseer, Larissa, David Moher, Mike Clarke, Davina Ghersi, Alessandro Liberati, Mark Petticrew, Paul G Shekelle, and Lesley Stewart. 2015. “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and Explanation.” BMJ 349 (jan02 1): g7647. [CrossRef]

- Schoeps, K., Mónaco, E., Cotolí, A., & Montoya-Castilla, I. (2020). The impact of peer attachment on prosocial behavior, emotional difficulties and conduct problems in adolescence: The mediating role of empathy. PLOS ONE, 15(1), e0227627. [CrossRef]

- Sherwood, C. C., Subiaul, F., & Zawidzki, T. W. (2008). A natural history of the human mind: tracing evolutionary changes in brain and cognition. Journal of Anatomy, 212(4), 426–454. [CrossRef]

- Simmons, A. T. (2013). In defense of the moral significance of empathy. Ethical Theory and Moral Practice, 17(1), 97–111. [CrossRef]

- Sporns, O. (2013). Structure and function of complex brain networks. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 15(3), 247–262. [CrossRef]

- Thibaut, F. (2018). The mind-body Cartesian dualism and psychiatry. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 20(1), 3. [CrossRef]

- Tost, H., Champagne, F. A., & Meyer-Lindenberg, A. (2015). Environmental influence in the brain, human welfare and mental health. Nature Neuroscience, 18(10), 1421–1431. [CrossRef]

- Ugazio, G., Majdandzić, J., Lamm, C., & Maibom, H. L. (2014). Are empathy and morality linked? In Oxford University Press eBooks (pp. 155–171). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Lobb-Rabe, M., Ashley, J. A., Anand, V., & Carrillo, R. A. (2021). Structural and Functional Synaptic Plasticity Induced by Convergent Synapse Loss in the DrosophilaNeuromuscular Circuit. The Journal of Neuroscience, 41(7), 1401–1417. [CrossRef]

- Wille, N., Bettge, S., & Ravens-Sieberer, U. (2008). Risk and protective factors for children’s and adolescents’ mental health: results of the BELLA study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 17(S1), 133–147. [CrossRef]

- Yoder, K. S., & Decety, J. (2017). The neuroscience of morality and social decision-making. Psychology Crime & Law, 24(3), 279–295. [CrossRef]

- Young, G. B. (2014). Diaschisis. In Elsevier eBooks (p. 995). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).