1. Introduction

The act of methodically analysing a particular issue and coming up with an answer is known as computational thinking. It consists of a particular type of skill group that is predicated on approaches and abilities for solving problems. The goal of this skill set is to comprehend, analyse, and create solutions for difficult situations. According to [

1,

2,

3], people with computational thinking abilities are supposed to be able to process information like computer scientists and use this method of thinking in all fields. Consequently, it may be concluded that the development of 21st century skills and computational thinking ability are closely related. According to [

4], computational thinking aids in the understanding of computable problems as well as the selection of appropriate tools and approaches for problem solving.

Almost every field of study appears to have some connection to computational thinking, from biology to machine learning [

5,

6]. The term “computational thinking” was coined to refer to problem-solving techniques that also make it possible to use modern technologies efficiently in a variety of contexts [

1]. Organizations have acknowledged the necessity for problem solving and the efficient use of information and communication technology, notwithstanding the lack of agreement among them. In this context, information societies—the age and society of today—need computational thinking. In order for people to coexist peacefully in society, it is vital to identify the knowledge, skills, and abilities that we require. Such studies are necessary for addressing the obstacles that societies—students in particular—will encounter in the years ahead. It is observed that common components are employed in the literature, despite the fact that the term computational thinking and its components remain unaltered [

7,

8,

9].

In addition to explorations of computational thinking and its elements, another subject of research involves how to quantify these elements. It has been observed in previous research that several measurement instruments are used to assess computational thinking. Numerous other techniques have been used with various approaches, including scales, portfolio studies, programming, multiple choice exams, task-based tests, observations, and rubrics [

10,

11,

12]. However, some believe that current approaches of measuring computational thinking may not be adequate. In fact, a student who performs well on examinations could nevertheless be an incompetent or insensitive algorithm creator, according to [

13]. The author of [

13] further underlined that while we do not assess pupils’ competencies or sensitivity, we do know what they know. He advised treating the components of computational thinking as a talent and grading them accordingly. He stated that assessment of abilities in school is a pretty typical practice and cited examples that included language, athletics, music, and theatre. By using this study to create a valid and trustworthy performance-based assessment tool, the framework seeks to quantify computational thinking abilities. Upon reviewing the literature, it becomes evident that the studies used to assess computational thinking have several drawbacks, including being confined to a narrow framework and relying on computer software in a traditional and dull manner [

14,

15]. Moreover, the measurement of computational thinking abilities in many of these investigations requires the expertise of an expert.

Psychometric scales are among the most widely used instruments for assessing computational thinking [

12,

14,

15,

16,

17]. However, the foundation of psychometric measures is the idea that a subject provides accurate and complete information [

18]. It is anticipated that the person have an inner vision, nonetheless [

19]. Performance-based assessments can be more appropriate because psychometric scales have these drawbacks and computational thinking components should be treated as skills [

13]. Furthermore, research on computational thinking measurement using performance-based assessment has highlighted the significance of receiving feedback at the appropriate moment [

20,

21]. Performance-based assessments offer numerous benefits, including their capacity to evaluate intricate and advanced cognitive abilities, and connection to the educational process [

22,

23,

24].

As computational thinking is a relatively new and growing skill, there is currently no agreement on its description or its constituent parts [

6,

8,

9,

25,

26]. Therefore, the current theoretical framework was used to conduct this investigation. The purpose of this study was to find a method to effectively measure computational thinking abilities in CS university students. Numerous studies in the literature have found that the only instruments available for measuring computational thinking are limited perception-attitude scales, multiple choice tests, or simple coding tests [

10,

12,

14,

15,

16,

27,

28]. However a performance-based platform, CTScore, for evaluating computational thinking abilities was created in [

29]. Additionally, it has been determined that performance-based assessment instruments provide more accurate results than psychometric scales. It is stressed that computational thinking should not be viewed as theoretical knowledge, a product or portfolio, or an attitude or perception, but rather as a talent or set of skills.

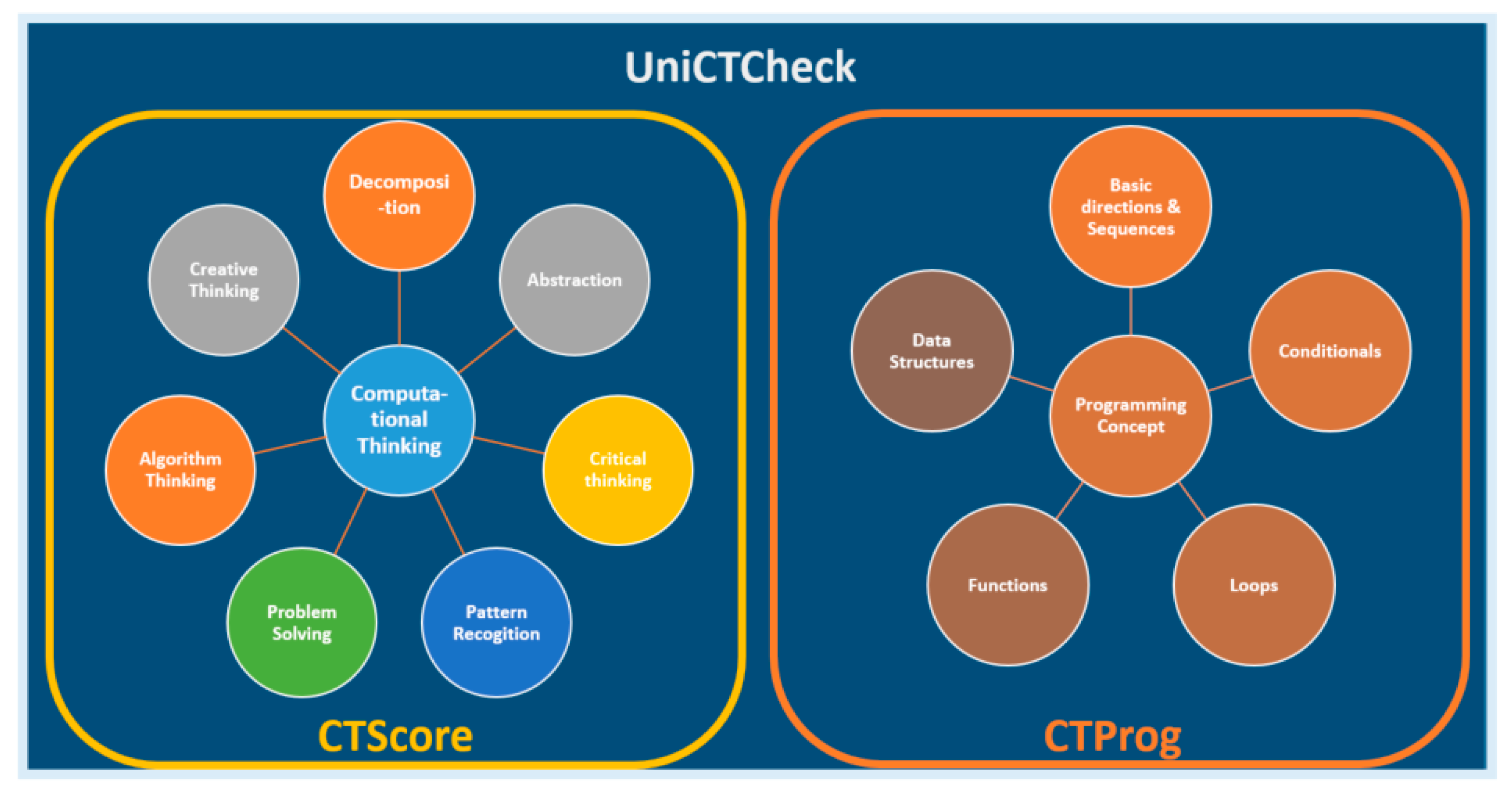

The goal of this research is to

develop UniCTChech, a method for measuring the main components of Computational Thinking in the context of CS University university courses

precisely measure 7 Computational Thinking components (Pattern Recognition, Creative Thinking, Algorithmic Thinking, Problem Solving, Critical Thinking, Decomposition and Abstraction) by using CTScore

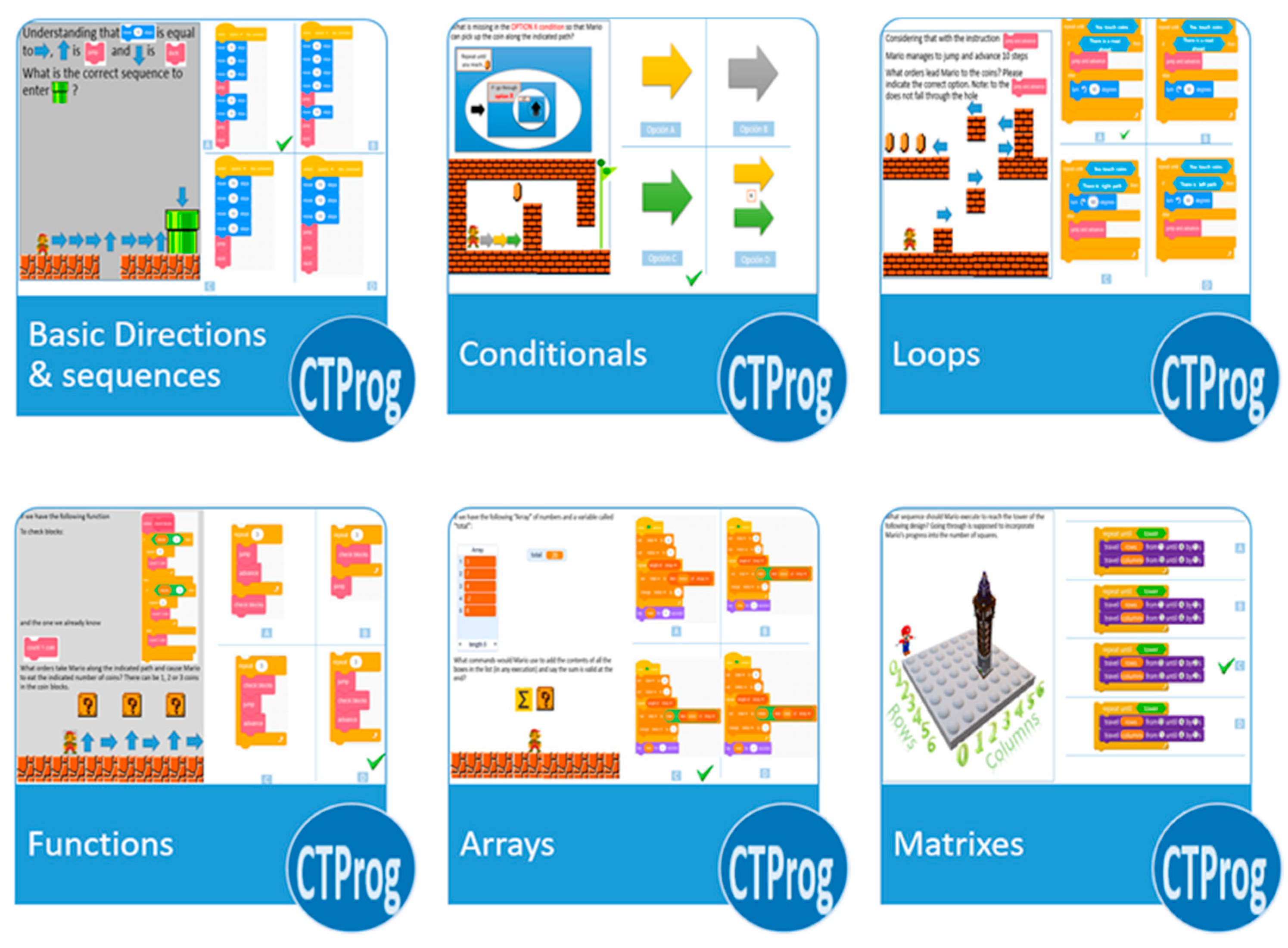

use a psychometric scale, CTProg, for measuring CT programming concepts skills that all CS university students should address sooner than later (Basic Directions & Sequences, Conditionals, Loops, Functions and Data Structures).

Given the paucity of research and advancement on the topic, it is believed that computational thinking has a vital role nowadays and that this study will significantly add to the body of literature. Therefore, we particularly try to address the following research problems in this work:

RQ1: Does UniCTCheck measure Computational Thinking main components and programming for CS University students?

RQ2: Is there a relationship between students’ computational thinking skill and programming abilities?

RQ3: Do students’ computational thinking skills and programming abilities vary by university level?

RQ4: Do students’ computational thinking skills and programming abilities vary by university location?

RQ5: Do students’ computational thinking skills and programming abilities vary by gender?

1.1. Computational Thinking

Despite lacking a precise definition yet, computational thinking has a rich history dating back to the early days of computer science. The phrase “computational thinking” first appeared in George Polya’s 1940 book How to Solve It, which discussed mental disciplines and techniques (Denning, 2017; Tedre & Denning, 2016). Then, in 1960, Alan Perlis coined the term “algorithmizing.” Perlis predicted that computers would automate procedures in every industry by using this word to describe practice and thought (Katz, 1960). Three of the field’s pioneers—Newell, Perlis, and Simon—discussed computer science in a 1967 publication. This published work considers “algorithmic thinking” to be a phrase that sets computer science apart from other disciplines [

30]. In 1980, Seymour Papert introduced the phrase “computational thinking” in his book Mindstorms: Children, computers, and powerful ideas [

31]. Even though Papert created the phrase first, no one had previously defined computational thinking in the very beginning. Papert used the phrase computational thinking a lot in his publications in the years that followed [

32,

33,

34]. In the 1950s and 1960s, in particular, “algorithmic thinking” was the term used before “computational thinking” [

35,

36,

37]. One of the fathers of computer science, Edsger Dijkstra, defined three characteristics of algorithmic thinking: the ability to move back and forth between semantic levels; the ability to reveal one’s own form and concept while solving problems; and the ability to use one’s mother tongue as a bridge between informal problems and formal solutions [

38].

The term “computational thinking” was originally used in Jeannette M. Wing’s widely read paper, Computational Thinking [

28,

39,

40,

41]. According to Wing, the phrase computational thinking encompasses problem-solving, system design, and behavioural analysis. Additionally, she said that not only computer scientists but everyone should use computational thinking [

1]. Despite being a seminal contribution to the area, Wing’s 2006 definition has drawn a great deal of criticism [

42]. Wing’s definition has drawn criticism for using an imprecise and confusing phrase [

26]. Moreover, her unverified assertions regarding the all-encompassing advantages of computational thinking have been deemed audacious [

39]. Wing’s article Computational Thinking and Thinking about Computing from 2008 brought the phrase computational thinking back into focus. Wing compared analytical and computational thinking in this paper. She pointed out that scientific, engineering, and mathematical reasoning are all entwined with computational thinking. Furthermore, she underlined once more that computational thinking applies to everyone and in all contexts [

2]. A variety of publications have been released in the years that have followed to provide a clearer definition of the phrase computational thinking. Thinking About Computational Thinking, is one of them [

43]. Rather than expressing criticism, Lu and Fletcher have declared their support for Wing’s 3R (writing, reading, and math) rule and for placing computational thinking at the centre of computer science. Nonetheless, debates over Wing’s concept persisted in the literature. Following this, Canadian computer scientist Alfred V. Aho wrote a piece on computational thinking for Alan Turing’s 100th birthday celebration in 2012. In this piece, Aho underlined the importance of precise and intelligible identification and the significance of settling on a scientific field’s nomenclature for the sake of comprehension [

44].

Educators have contributed to Wing’s development of the term computational thinking as well as Papert’s traditional formulation through hundreds of workshops, committees, research, polls, and public evaluations [

13,

45]. On the other hand, it is impossible to discuss a widely agreed upon definition and list of elements for computational thinking. Communities like CSTA, CAS, and ISTE, which are regarded as leading and respected organisations, have not been able to come to an agreement on the components of computational thinking [

46,

47,

48]. This disagreement is in addition to the divergent opinions of researchers regarding the definition of computational thinking. However, based on a review of the literature, it appears that there are recurring themes that are well acknowledged under the heading of the suggested definition [

9]. According to educators, computational thinking is particularly beneficial for enhancing logical reasoning, growing analytical thinking, and problem-solving abilities [

49].

1.2. Components of Computational Thinking

Problem-solving techniques are unquestionably a part of computational thinking [

3,

8]. Computational thinking is described by Wing in her well-known article as problem solving, system design, and behavioural analysis. She also said that, as opposed to thinking like a computer, computational thinking involves addressing issues in an efficient and original way. Nonetheless, she stressed that computational thinking encompasses methods like recursion, systematic testing, problem analysis, abstraction, and problem re-explanation [

1]. The concept of computational thinking and its constituent parts have sparked a great deal of discussion in the years that followed. The components have been recommended by communities, educators, and pioneering computer scientists (See

Table 1). Computational thinking include testing hypotheses, managing data, parallelism, abstraction, and debugging, according to the National Research Council [

50]. Barr and Stephenson provided an organised approach that allowed them to separate computational thinking into two types of concepts and abilities. According to [

51], capabilities include automation, abstraction, simulation, issue decomposition, data collecting, analysis, and representation. In [

52] the authors categorised computational thinking into three categories: views, applied methods, and concepts. However, this categorization only pertains to programming. Gouws et al. separated computational thinking into two categories in order to develop a framework. A set of abilities related to computational thinking is included in the first of these aspects. Processes and transformations, models and transformations, logic and inference, patterns and algorithms, assessments, and enhancements are some examples of these. The idea that various skills—such as identifying, comprehending, applying, and assimilating—have varying degrees of experience defines the second dimension [

53]. Another study [

54] classified computational thinking as abstraction, generalisation, and trial-and-error processes. Similar component recommendations were made in a study that sought to draw a link between learning theories and computational thinking. These elements encompass heuristic scanning, trial-and-error, abstract and divergent thinking, recursion, iteration, collaborative approaches, metacognition, patterns, and synectics [

55]. According to a recently released study, computer programmers frequently employ computational thinking as a problem-solving strategy. Problem analysis, pattern identification, abstraction, algorithm creation for answers, and evaluation of solutions (including debugging) are some of its constituents [

56].

Prominent organizations have also released research on computational thinking components, in addition to the academics (See

Table 2). Beyond contributing to the communities, studies on computational thinking published by well-known tech giant Google have also added to the body of literature. Pattern recognition, decomposition, pattern generalisation and algorithm design, and abstraction are the four areas into which Google separated computational thinking [

57]. The setting designed to gauge the degree of computational thinking and programming concepts in this study was centred around seven distinct elements (

Figure 1 left) with CTScore web app, and 5 computational programming concepts (

Figure 1 right) with CTProg psychometric scale test, conforming the UniCTCheck.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

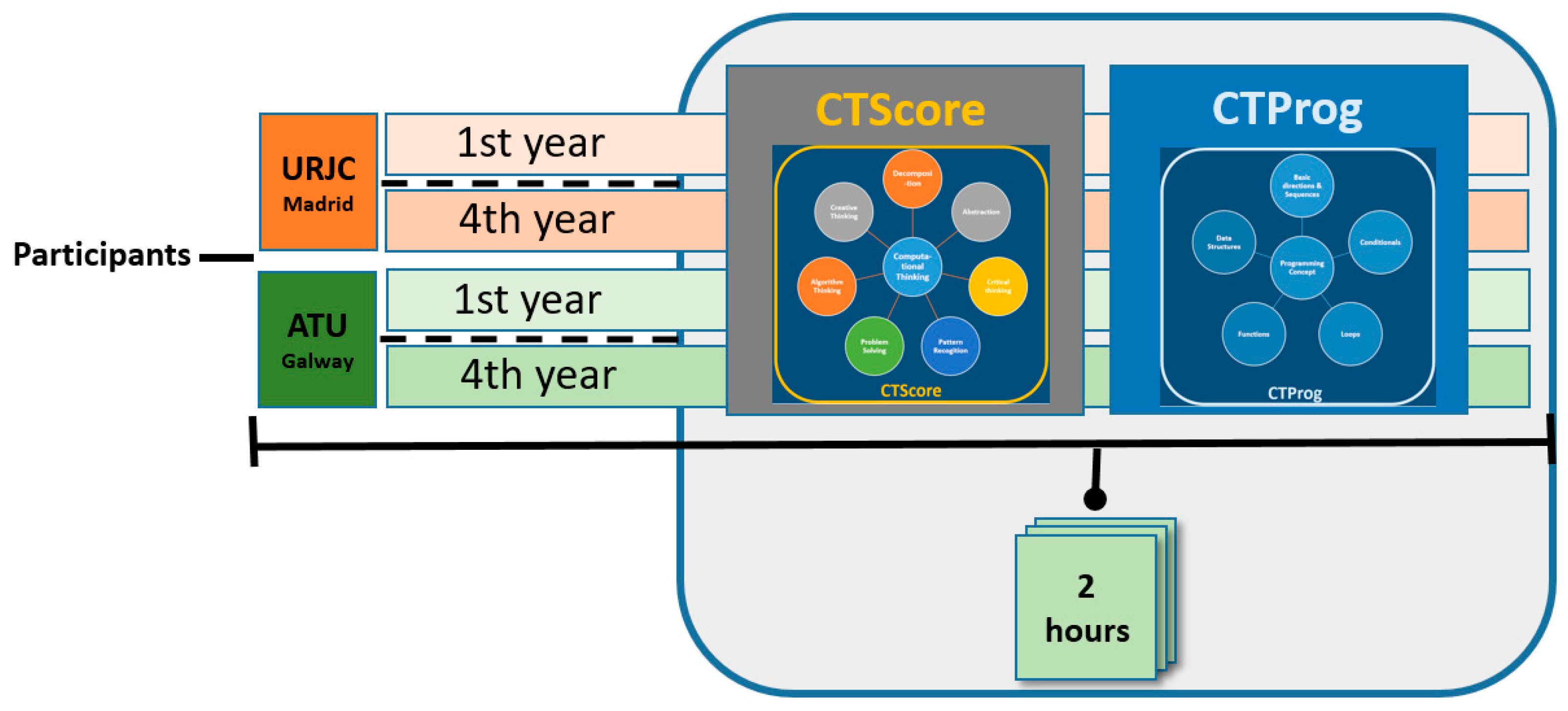

A quantitative study was conducted to measure the computational thinking ability of students studying the subjects “Visual Programming” and “Games for web and social networks” of the Video Games Degree of the ETSII, URJC, and of students studying the subjects of “Software Design and Program Development” and “Software Engineering” of the BSc in Software Development in the Atlantic Technological University (ATU), Galway, Ireland. A first year subject and a final year subject was selected at each university. The students used an interactive web application called CTScore for measuring Computational Thinking abilities [

29], and also a psychometric programming scale (CTProg), to measure programming skills, as a complement to the CTScore web application. CTProg, to complement the CTScore web app.

Figure 2.

Outline of the experiment settings and components.

Figure 2.

Outline of the experiment settings and components.

2.2. Sampling

The sample for this study was drawn from the students studying in two European universities, Universidad Rey Juan Carlos (URJC) in Madrid, Spain, and Atlantic Technological University (ATU) in Galway, Ireland. In both settings a Computer Science Degree where the researchers teach have been selected. From URJC, there have been 75 students enrolled in the 1st year subject of “Introduction to Programming”, and 90 students of the 4th year subject “Games for the web and social networks” both from the Design and Development of Video Games Degree. From ATU, 25 students enrolled in the subject of “Software Design and Program Development” and the 30 students enrolled in the subject “Software Engineering” in the BSc in Software Development at the Atlantic Technological University, Galway, Ireland.

2.3. Ethics Comitee

Research Ethics Committee of the Rey Juan Carlos University has favorably evaluated this research project with internal registration number 1909202332223.

2.4. Data Collection Tools

UniCTCheck collects data from two tools, CTScore and CTProg. In the following subsections their scope and characteristics will be explained.

2.4.1. CTScore

CTScore is a validated interactive web application for measuring Computational Thinking abilities in students [

30]. In this paper, the web app is offered in English (

https://emrecoban.com.tr/bd/) and Spanish (

https://emrecoban.com.tr/bd/es/) for the first time. CTScore measures seven computational thinking components, namely: abstraction, pattern recognition, critical thinking, decomposition, creative thinking, algorithm thinking and problem solving, by asking students to answer 12 questions (See

Figure 3). During the evaluation, students have been evaluated automatically with the same scoring key, where a maximum of 10 points and a minimum of 0 (zero) points can be obtained from each question. Accordingly, each question determines the total score of the component in which it is located. For example, since the abstraction component contains two questions, the maximum score that students can achieve in this component will be 20 points.

2.4.2. CTProg

CTProg is a psychometric scale test created by the authors to measure the conceptual understanding of 5 core programming fundamentals, not depending on any particular programming language. It is formed by 14 questions, providing a schematic block programming language university students can understand independently of their knowledge of specific programming languages. The tests have been used with university students and revised by the researchers over the course of three academic years (2017-18, 2018-19 and 2019-20), continually evolving during this period. The main concepts addressed by the 14 questions are: basic directions & sequences, conditions, loops, functions and data structures (arrays & matrixes). CTProg is offered both in English (

https://forms.office.com/e/JXDaTriwi9) and Spanish (

https://forms.office.com/e/3mbvMXw1vX). During the evaluation, students have been evaluated automatically with the same scoring key, where a maximum of 1 point and a minimum of 0 (zero) points can be obtained from each question. Accordingly, each question determines the total score of the programming concept in which it is located (See

Figure 4). Each of the main concepts addressed contains two questions, but the loop concept contains 4 questions, therefore, the maximum score that students can achieve in this component will be 14 points.

3. Results

This section will show the most relevant results of the study. This focuses on general results to later carry out a detailed study by different dimensions.

3.1. Relations Amongs Variables

Firstly, the possible relationship between the different variables studied is analysed. As the variables do not follow a normal distribution (Shapiro-Wilk test with p-value <0.01), a possible linear correlation is analyzed using Kendall’s Tau-b.

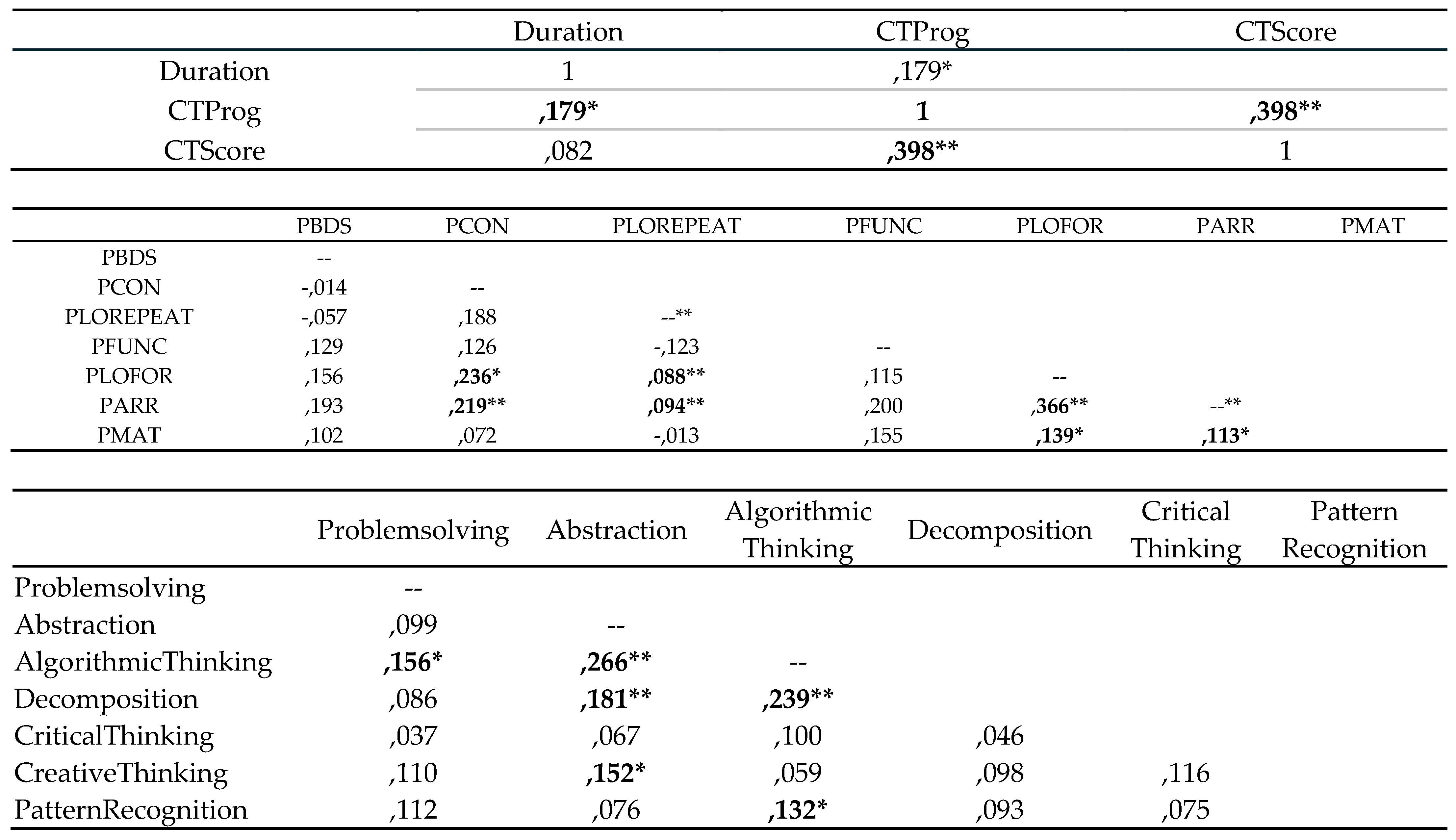

Table 3 marks the significant linear correlations in black. Thus it can be seen that:

-There is a positive linear correlation between the duration of the test and the total score on the Programming test (CTProg). This indicates that that more time spent by students in answering the test resulted in higher performance.

-There is a positive linear correlation between the total score on the Programming Test (CTProg) and total score on the CT Test (CTScore). This demonstrated that students that do well in the Programming Test, also do well in the CT Test. Thus it can be said that programming knowledge leads to CT skills adquisition.

-There is a positive linear relationship between students knowledge of for loops (PLOFOR) with their knowledge of conditionals (PCON) and repeat loops (PLOREPEAT). Thus it can be said that students learning of any type of loops leads to their learning of conditionals, and viceversa.

-There is a positive linear relationship between knowledge of the array data structure(PARR) with their knowledge of conditionals (PCON), and all types of loops, repeat loops (PLOREPEAT), and for loops (PLOFOR). Therefore, it can de deduced that students that are familiar with more advanced programming concepts such as arrays, have to have to previously mastered conditionals and loops.

-There is a positive linear relationship between knowledge of the matrix data structure (PMAT) with their knowledge of for loops (PLOFOR) and knowledge of arrays (PARR). Therefore, coomprehension of two dimensional arrays (matrices) requires knowledge and understanding of one dimensional arrays, and the for loop structures to to work effectively with them.

-There is a positive linear relationship between the CT Skill of Problem Solving (Problemsolving) with the CT Skill of algorithmic thinking (AlgorithmicThinking). This shows that students with good problem solving ability do well on the algorithm thinking test and viceversa.

-There is a positive linear relationship between the CT Skill of abstraction (Abstraction) with the CT skills of algorithm thinking (AlgorithmicThinking), decomposition (Decomposition) and creative thinking (CreativeThinking). As a consequence, students with a higher capacity of abstraction, perform as well or better in other CT skills suchs as, algorithm thinking, decomposition and creative thinking.

-There is a positive linear relationship between the CT Skill of algorithm thinking (AlgorithmicThinking) with the CT skill of decomposition (Decomposition) and pattern recognition (PatternRecognition). As shown, students overperforming in algorithm thinking, also do well in CT skills like decomposition and pattern recognition.

3.2. Comparative between Courses

The scores of each variable are compared between the first and fourth years. Firstly by the general score on either test, the CT Test (CTScore) and the Programming Test (CTProg); then by university, the Rey Juan Carlos University and the Atlantic Technological University.

3.2.1. General Results

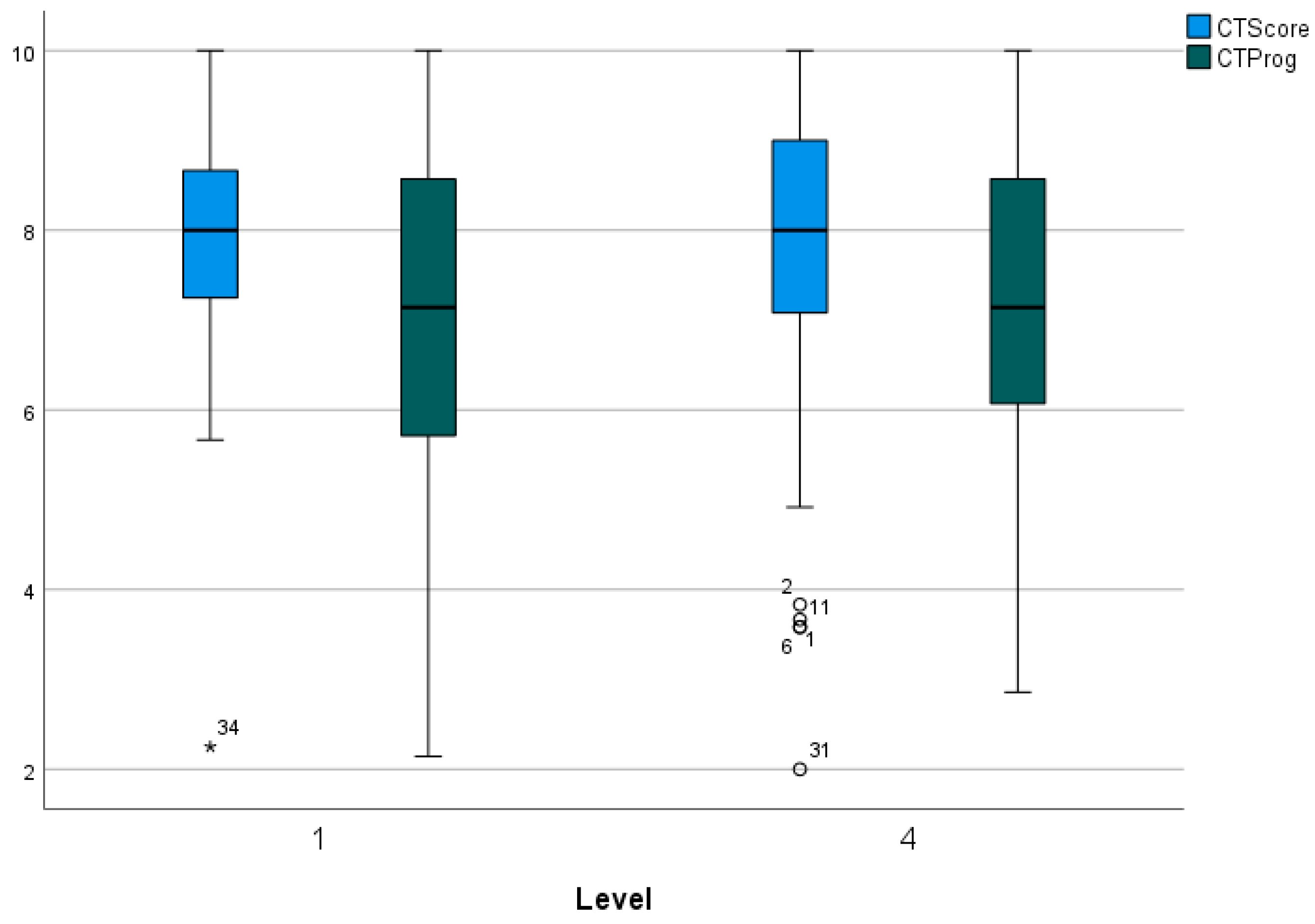

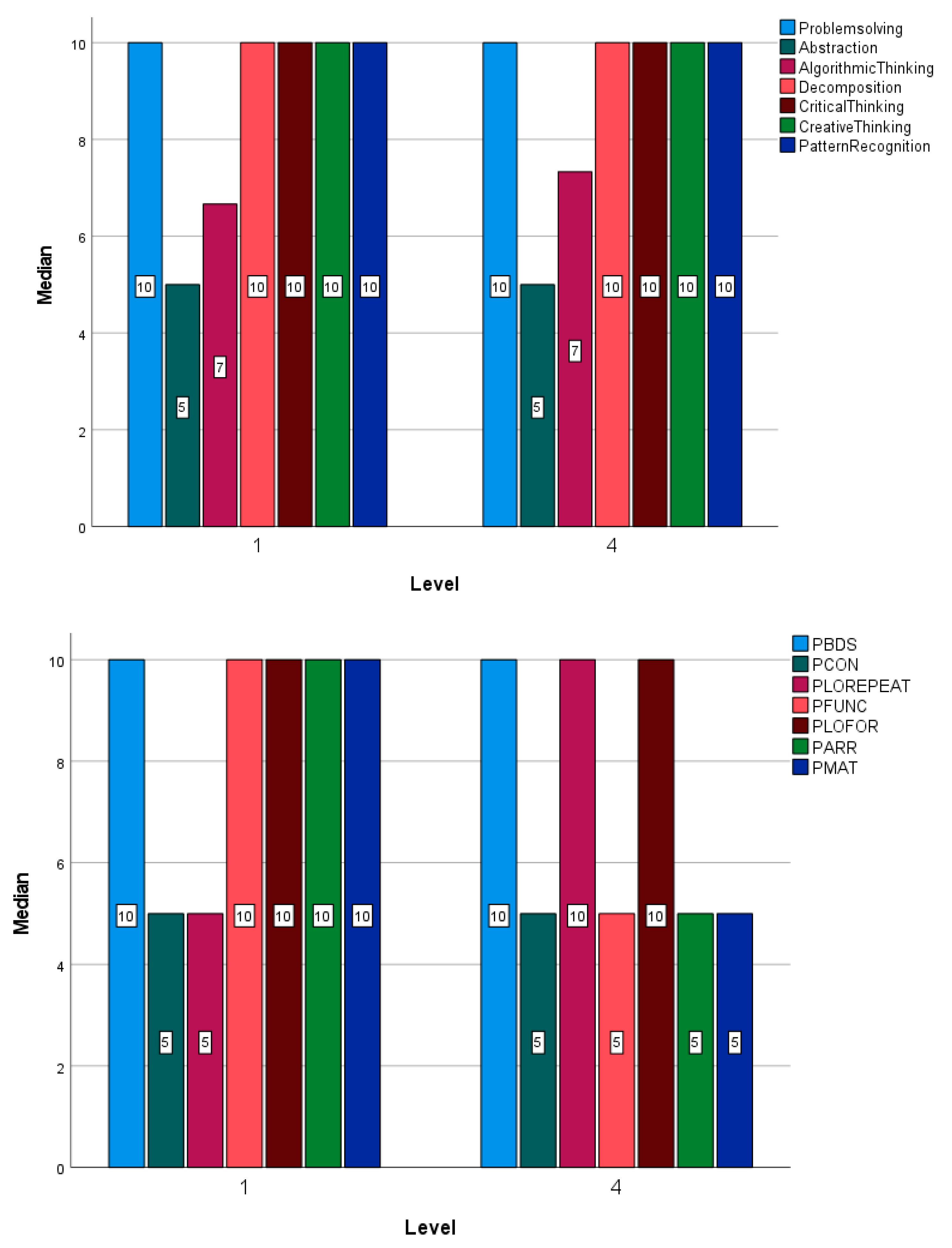

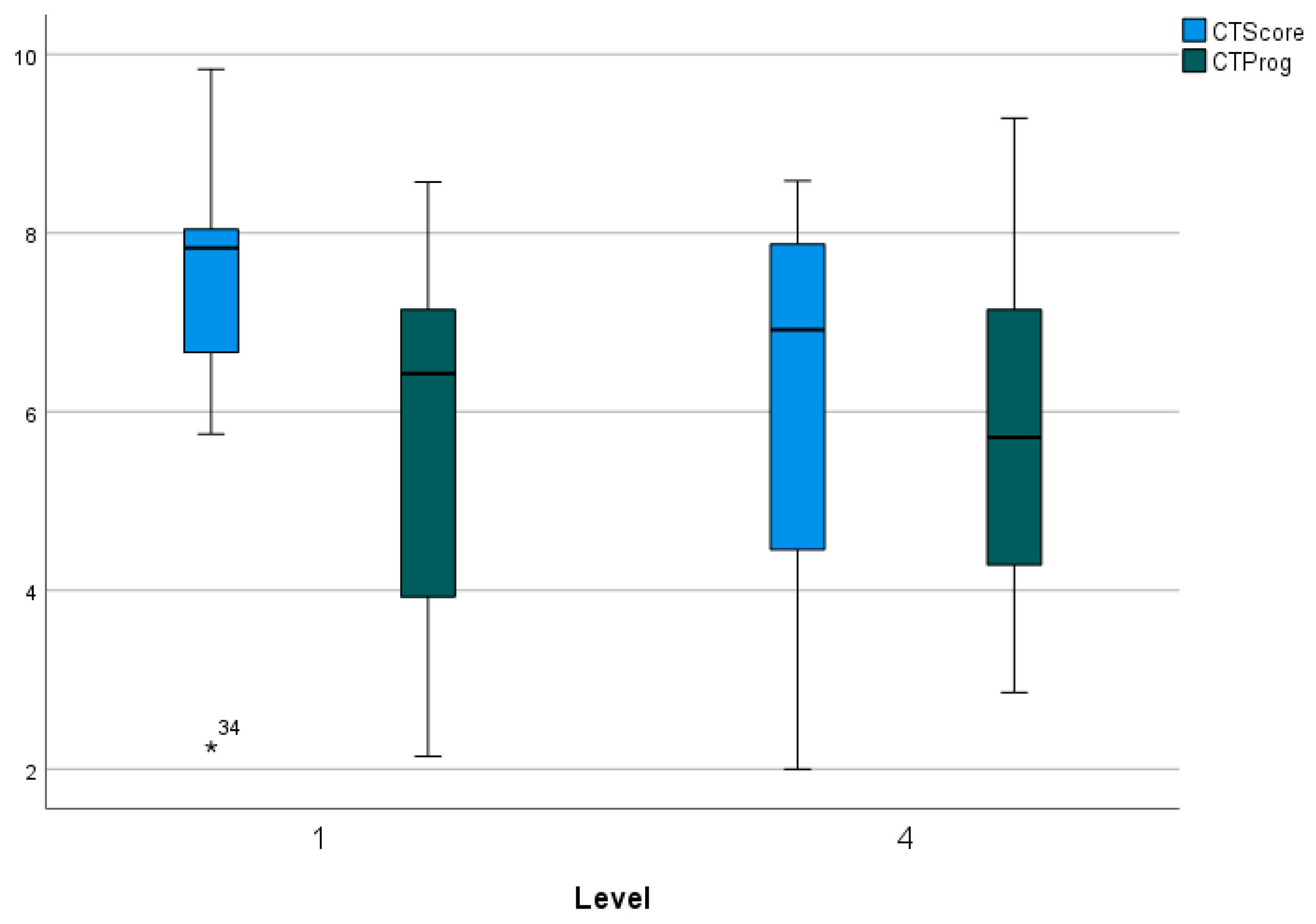

The

Figure 5 shows the box-plots for the CTScore and CTProg variables differentiated between the first and fourth years. As can be seen, the central values of both variables are maintained in both years, with greater dispersion being perceived for both in the fourth year. Using the Mann-Whitney U test (

Table 4), it can be seen that these minimal differences are, in effect, not significant, so it can be ensured that there are no significant differences between both courses.

Figure 5.

Box-plots for the CTScore and CTProg total scores by years (1st and 4th) in general.

Figure 5.

Box-plots for the CTScore and CTProg total scores by years (1st and 4th) in general.

| |

CTProg |

CTScore |

| |

1st |

4th |

1st |

4th |

| Mean |

7.03 |

7.09 |

7.81 |

7.85 |

| Median |

7.14 |

7.14 |

8.00 |

8.00 |

| SD |

1.54 |

1.74 |

1.27 |

1.54 |

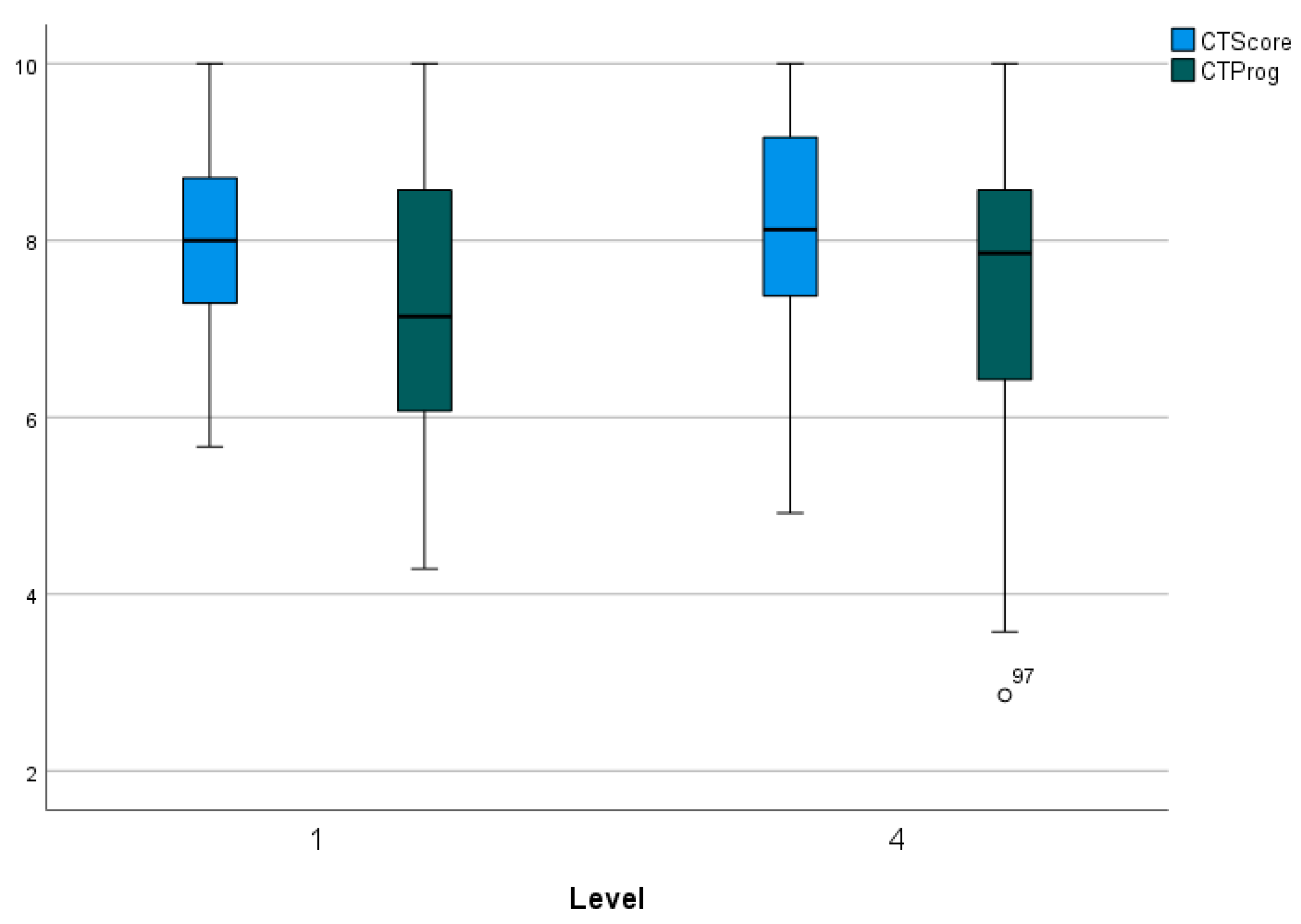

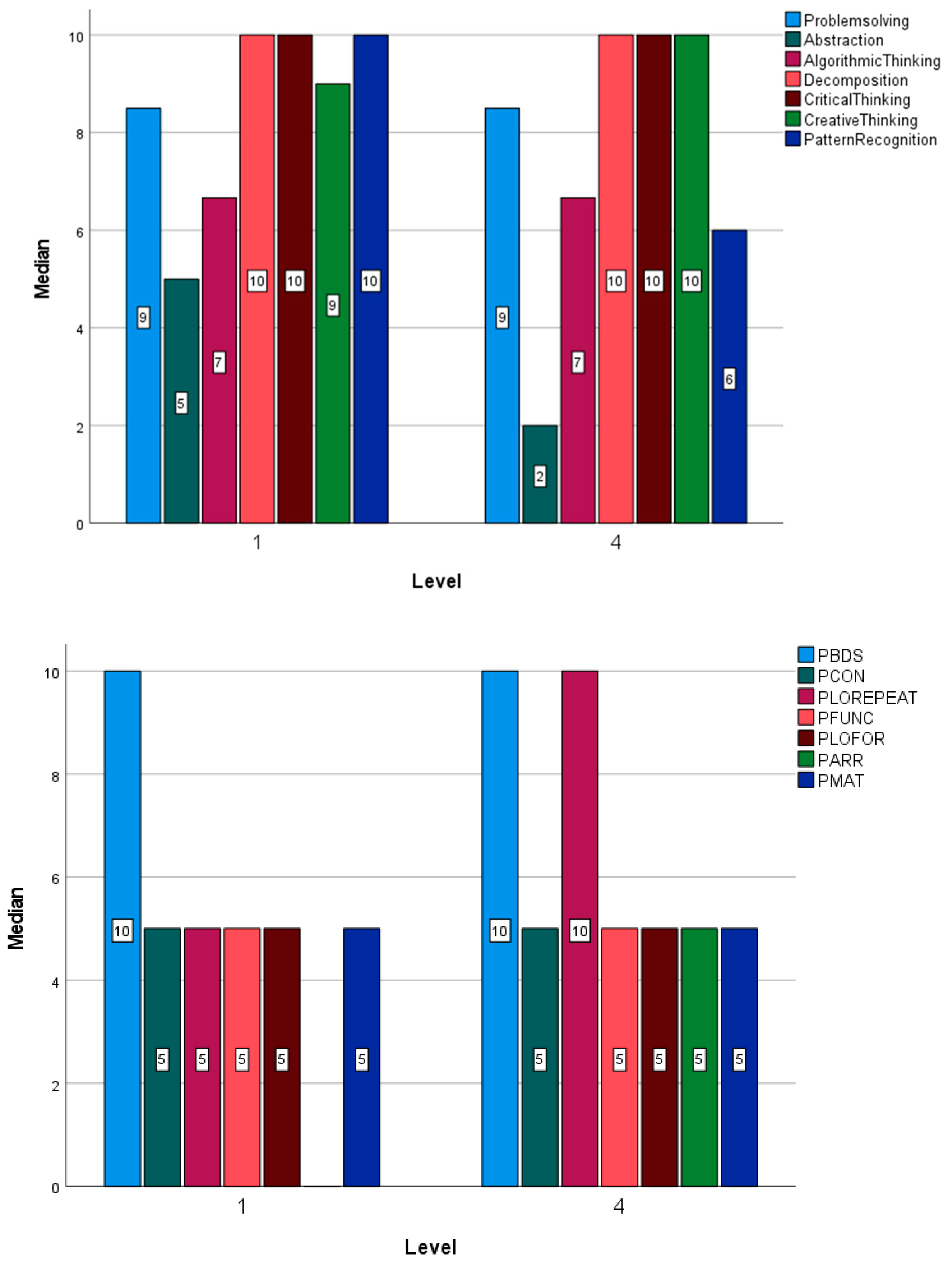

Now, the focus is on seeing the differences between each of the variables studied. The following graphs (

Figure 6, top and bottom) show the median of each of them, as a representative of the central tendency of the data. The median is used instead of the mean since there is no symmetry in the distribution of the data, with the median being a more robust measure. Although they are not statistically significant, changes can be seen between the first and fourth years in the variable for the programming concepts of Repeat loops (PLOREPEAT), functions (PFUNC), arrays (PARR) and matrixes (PMAT).

3.2.2. Rey Juan Carlos University (URJC)

This part of the study focuses on the Rey Juan Carlos University (URJC). In this case (see

Figure 7) the values obtained are similar in the first and fourth years for the two variables, the CT Test (CTScore) and for the Programming Test (CTProg). In the case of CTScore, the median has increased its value slightly, being 8 in the first year and 8.13 in the fourth year. Dispersion has clearly increased. In the case of CTProg, the median has increased its value, going from 7.14 to 7.85 from first to fourth, respectively. Again, the dispersion in the data has increased.

In the case of bar graphs (see

Figure 8) very little change is in the medians depending on the course, only in the Algorithm Thinking variable (AlgorithmicThinking) variable from the CTScore, where it goes from 7 to 10. In the case of the programming variables, the median has increased in the conditionals (PCON) and repeat loops (PLOREPEAT) and decreased in the matrixes (PMAT).

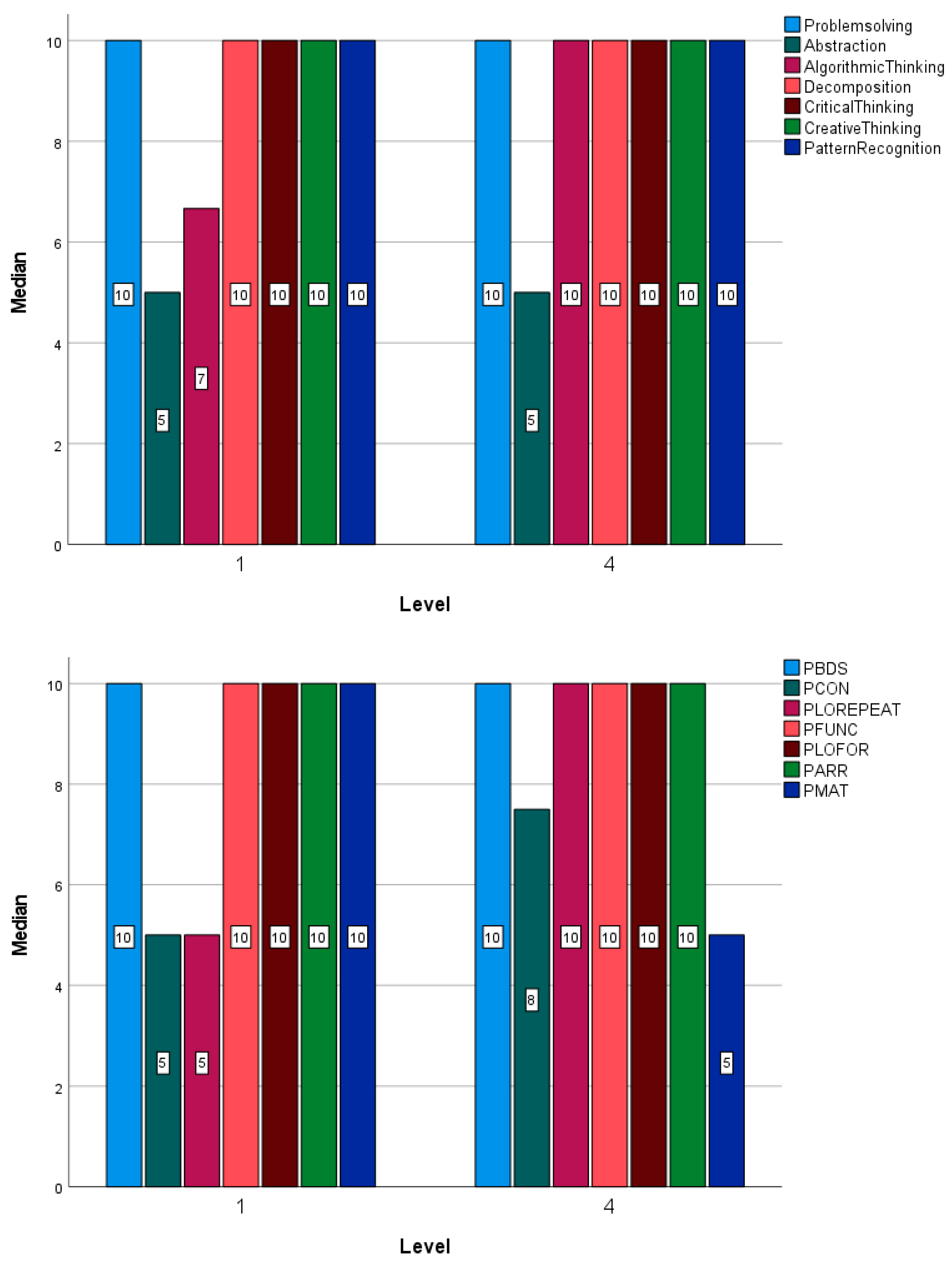

3.2.3. Atlantic Technological University (ATU)

The study now focuses on the Atlantic Technological University (ATU). It is observed that, although statistically the difference between medians is not significant, the medians of the two variables CTScore and CTProg have lowered their value from first to fourth year (

Figure 9). The dispersion, in the case of CTScore, has increased a lot, remaining similar in CTProg.

In the case of bar graphs,

Figure 10, very little change is seen in the medians depending on the course, only in the abstraction variable (Abstraction), where it decreases from 5 to 2, creative thinking (CreativeThinking) where increases slightly, and in the pattern recognition (PatternRecognition) variable, where it decreases from 10 to 6. Regarding, the programming concepts, in the case of repeat loops (PLOREPEAT) and arrays (PARR) the median has increased.

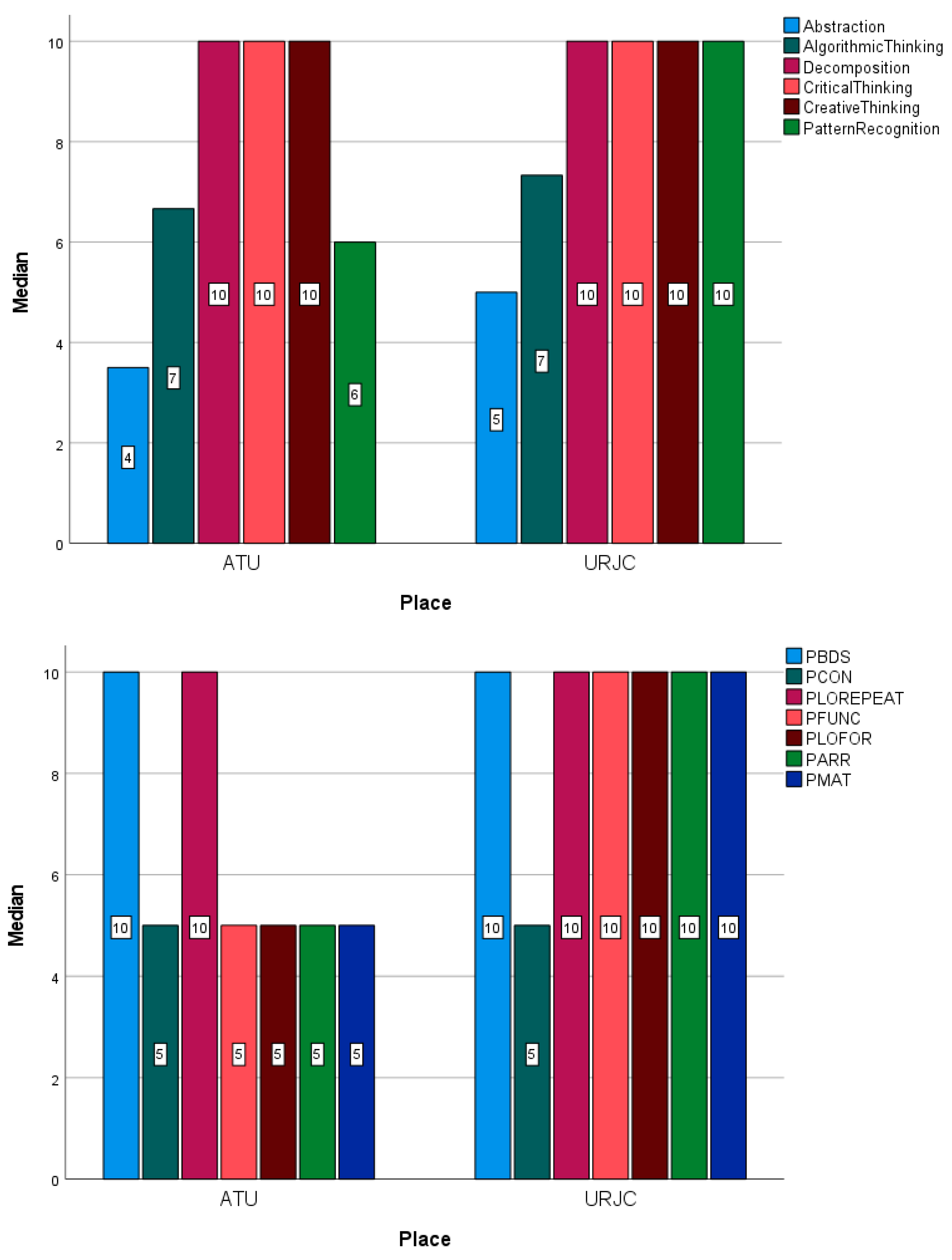

3.3. Comparative between Universities

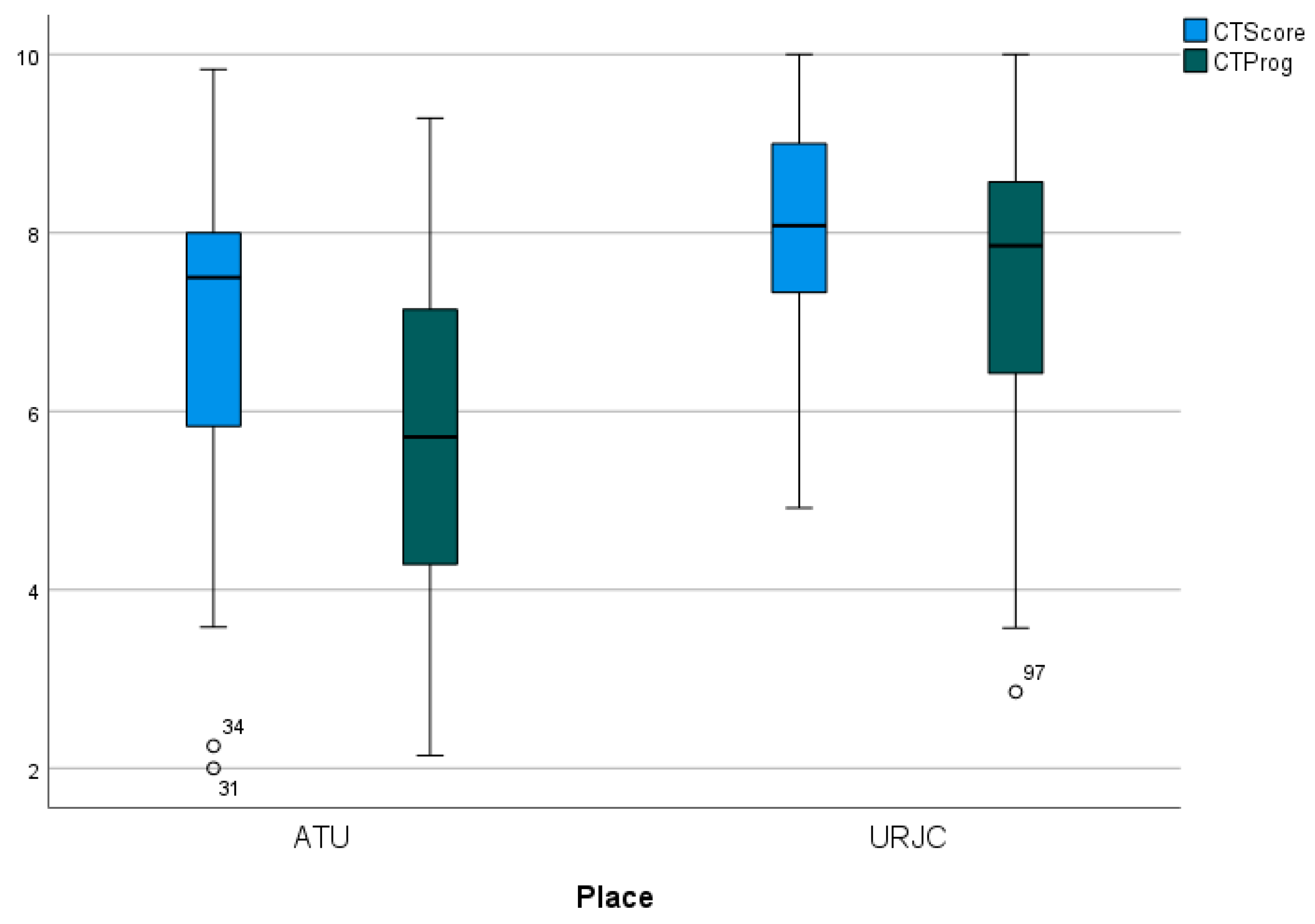

The box-plot in

Figure 11 shows the difference, by university, of the two global score on CTScore and CTProg. This significant difference (p<0.001 according to the Mann-Whitney U test) is manifested in significantly higher values on average in URJC (almost 2 points of difference in both mean and median), with the dispersion being lower in the URJC.

Figure 11.

Box-plots for the CTScore and CTProg total scores by years (1st and 4th) in both universities.

Figure 11.

Box-plots for the CTScore and CTProg total scores by years (1st and 4th) in both universities.

| |

CTProg |

CTScore |

| |

ATU |

URJC |

ATU |

URJC |

| Mean |

5.69 |

7.39 |

6.74 |

8.09 |

| Median |

5.71 |

7.85 |

7.5 |

8.08 |

| SD |

1.93 |

1.51 |

1.98 |

1.12 |

| |

CTProg |

CTScore |

| U |

1220 |

14232 |

| p-value |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

The median graphs show a similar trend (

Figure 12), with the median values of the variables studied being greater or equal, in all cases, in the URJC.

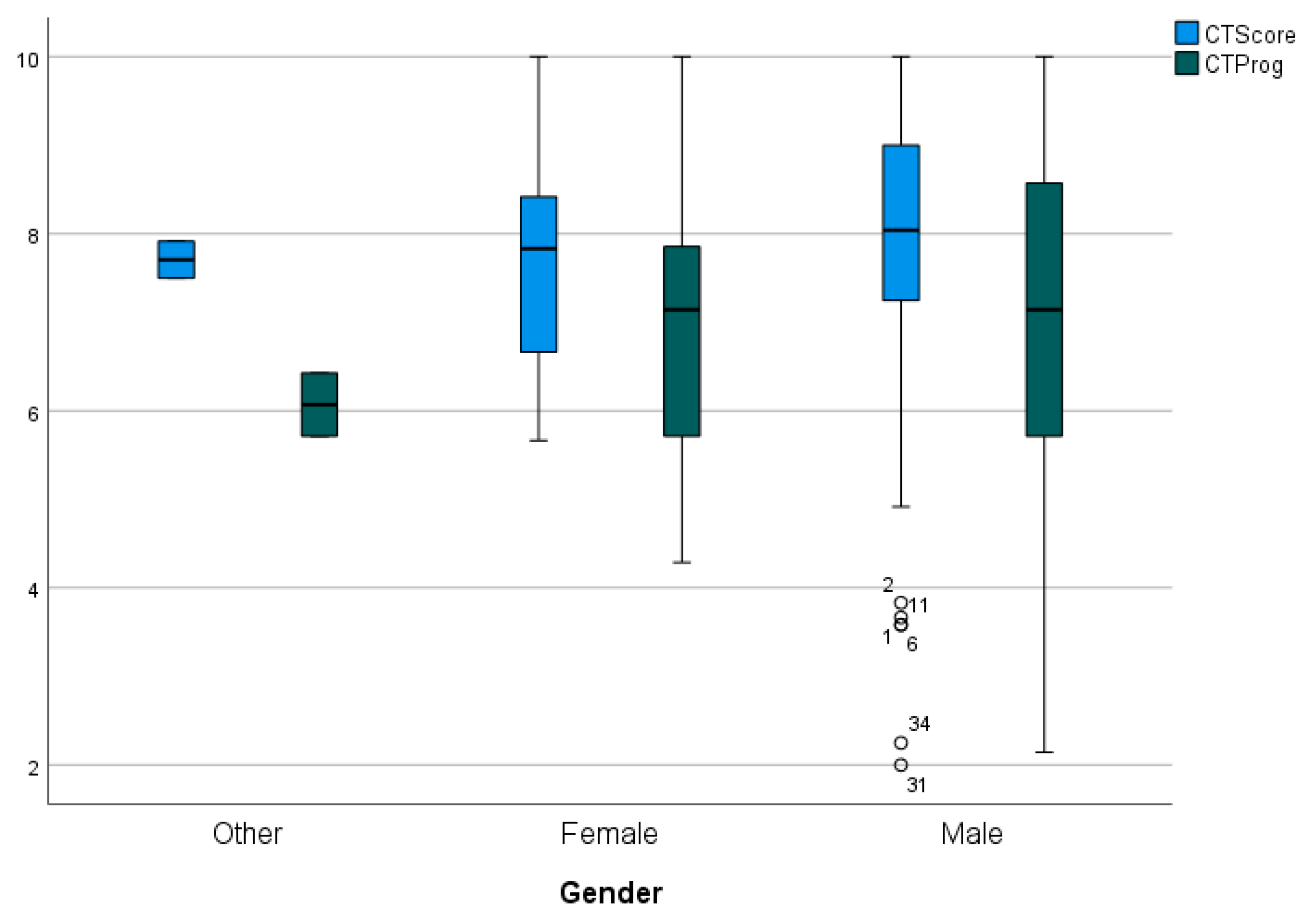

3.4. Comparative between Gender

Between genders,

Figure 13, there is no statistically significant difference. The box-plot figure shows the similarity in both median and dispersion for all genders. In the case of “Other” genres, given the small quantity (2 cases), their interpretation is not very relevant.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

This study makes a significant addition by providing a thorough examination of the methods for gauging differences in students’ programming and computational thinking abilities by geography, gender, and university level. This paper presents UniCTCheck, an innovative approach created to evaluate the fundamentals of computational thinking in computer science students. This study used two important tools, the web application CTScore and the psychometric scale CTProg, to measure seven fundamental aspects of computational thinking and six critical programming ideas for computer science students. To answer this, the following five research questions were formulated:

RQ1: Does the UniCTCheck measure Computational Thinking main components and programming for CS University students?

The results from the study indicate that UniCTCheck effectively measures the main components of computational thinking and programming for computer science university students. Through the use of CTScore and CTProg, a comprehensive assessment of Pattern Recognition, Creative Thinking, Algorithmic Thinking, Problem Solving, Critical Thinking, Decomposition, Abstraction, as well as programming concepts like Basic Directions & Sequences, Conditionals, Loops, Functions, and Data Structures was conducted. The data revealed that the UniCTCheck method provides a robust framework for evaluating students’ computational thinking abilities and programming skills accurately.

RQ2: Is there a relationship between students’ computational thinking skill and programming abilities?

The time expend by students on answering the Programming test (CTProg) is directly related to their higher performance on it. Also students that do well in the CTProg, do well in the CT Skills Test (CTScore), thus it can be said that programming knowledge leads to CT skills adquisition. It has been also proved that students learning of any type of loops leads to their learning of conditionals, and viceversa. Furthermore, students that know of more advanced programming concepts such as arrays, need to have previously mastered conditionals and loops. Moreover, comprehension of two dimensional arrays (matrices) requires knowledge and understanding of one dimensional arrays, and the for loops structures to work effectively with them. Regarding the CT Skill adquisition, students with the ability of problem solving do well on the algorithm thinking ability and viceversa. In the same maner, students with a higher capacity of abstraction perform as well or better in other CT skills suchs as, algorithmic thinking, decomposition and creative thinking. As shown, students overperforming in algorithm thinking, also do well in CT skills like decomposition and pattern recognition.

RQ3: Do students’ computational thinking skills and programming abilities vary by university level?

In general, there are no significant differences between both courses. Although they are not statistically significant, changes can be seen between the first and fourth years for the programming concepts of Repeat loops, functions, arrays and matrixes.

When the study focuses on the Rey Juan Carlos University (URJC), in the case of CTScore, the median has increased slightly in the fourth year, also dispersion has clearly increased. In the case of CTProg, the median has also increased from first to fourth, again, the dispersion in the data has increased. Also very little change occurs in the medians depending on the course, only in the Algorithm Thinking skill from the CTScore. In the case of the programming variables, the median has increased in the conditionals and repeat loops and decreased in the matrixes.

Whe the study focuses on the Atlantic Technological University (ATU), it is observed that, although statistically the difference between medians is not significant, the medians of the two variables CTScore and CTProg have lowered their value from first to fourth year. The dispersion, in the case of CTScore, has increased a lot, remaining similar in CTProg. Very little change is seen in the medians depending on the course, only in the CT Skills of abstraction, where it decreases, creative thinking, where it increases slightly, and in pattern recognition, where it decreases. Regarding, the programming concepts, in the case of repeat loops and arrays the median has increased.

RQ4: Do students’ computational thinking skills and programming abilities vary by university location?

There exists significant difference, by university, of the two global score on CTScore and CTProg. This significant difference is manifested in significantly higher values on average (almost 2 points of difference in both mean and median), with the dispersion being lower in the URJC. Also the median values of the variables studied being greater or equal, in all cases, in the URJC.

RQ5: Do students’ computational thinking skills and programming abilities vary by gender?

The examination of computational thinking skills and programming abilities by gender revealed no statistically significant difference. While there were minor variations in performance between male and female students, the data indicated that both genders displayed similar levels of competency overall. This suggests that computational thinking skills and programming abilities are not inherently gender-specific and can be developed by students regardless of gender.

In conclusion, the data-driven responses to the research questions provide valuable insights into the nuances of students’ computational thinking skills and programming abilities in the context of gender, university level, and geography. By leveraging the UniCTCheck method and the assessment tools CTScore and CTProg, this study has shed light on the diverse competencies of computer science students and highlighted the importance of tailored educational interventions to enhance their skills effectively.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, R.H.N, C.P., J.F., D.P.A. and E.C.; methodology, R.H.N., C.P., J.F., D.P.A. and E.C; software, R.H.N., D.P.A. and E.C.; validation, R.H.N., C.P., J.F., and E.C..; formal analysis, R.H.N. and C.P.; investigation, R.H.N., C.P., J.F.; resources, R.H.N., D.P.A. and E.C.; data curation, R.H.N. and C.P.; writing—original draft preparation, R.H.N. and C.P.; writing—review and editing, R.H.N., C.P. and J.F.; visualization, R.H.N., C.P., D.P.A. and E.C; supervision, R.H.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by research Grants PID2022-137849OB-I00 funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by ERDF, EU.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Research Ethics Committee of the Rey Juan Carlos University with internal registration number 1909202332223.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to ethical reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wing, J. M. (2006). Computational thinking. Communications of the ACM, 49(3), 33–35. [CrossRef]

- Wing, J. M. (2008). Computational thinking and thinking about computing. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering.

- Cuny, J., Snyder, L. & Wing, J.M. (.2010). Demystifying computational thinking for non-computer scientists. Unpublished manuscript in progress, referenced in.

- Mohaghegh, M., & McCauley, M. (2016). Computational Thinking: The Skill Set of the 21st Century. International Journal of Computer Science and Information.

- Fisher, J., & Henzinger, T. A. (2007). Executable cell biology. Nature biotechnology, 25(11), 1239–1249.

- Qin, H. (2009). Teaching computational thinking through bioinformatics to biology students. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 40th ACM technical symposium on Computer science education.

- García-Peñalvo, F. J., & Mendes, A. J. (2018). Exploring the computational thinking effects in pre-university education. Computers in Human Behavior, 80, 407–411. [CrossRef]

- Higgins, C., O’Leary, C. H., & O. Mtenzi, F. (2017). A conceptual framework for a software development process based on computational thinking. In Proceedings of the 11th international technology, education and development conference (INTED17) (pp. 455–464). [CrossRef]

- Selby, C., & Woollard, J. (2013). Computational thinking: The developing definition University of Southampton (E-prints) 6pp. Retrieved from http://eprints.soton.ac.uk/id/eprint/356481.

- de Araujo, A. L. S. O., Andrade, W. L., & Guerrero, D. D. S. (2016, October). A systematic mapping study on assessing computational thinking abilities (pp. 1–9). IEEE.

- Kong, S.-C. (2019). Components and methods of evaluating computational thinking for fostering creative problem-solvers in senior primary school education. Computational thinking education (pp. 119–141). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Román-González, M., Moreno-León, J., & Robles, G. (2019). Combining assessment tools for a comprehensive evaluation of computational thinking interventions. In Computational Thinking Education (pp. 79–98). Springer.

- Denning, P. J. (2017). Remaining trouble spots with computational thinking. Communications of the ACM, 60(6), 33–39. [CrossRef]

- Haseski˙, H. I., & Ilic, U. (2019). An Investigation of the Data Collection Instruments Developed to Measure Computational Thinking. Informatics in Education, 18(2), 297.

- Tang, X., Yin, Y., Lin, Q., Hadad, R., & Zhai, X. (2020). Assessing computational thinking: A systematic review of empirical studies. Computers & Education, 148, Article 103798. [CrossRef]

- Varghese, V. V., & Renumol, V. G. (2021). Assessment methods and interventions to develop computational thinking—A literature review. In 2021 International conference on innovative trends in information technology (ICITIIT) (pp. 1–7). IEEE.

- Poulakis, E., & Politis, P. (2021). Computational Thinking Assessment: Literature Review. Research on E-Learning and ICT in Education: Technological. Pedagogical and Instructional Perspectives, 111–128.

- Alan, Ü. (2019). Likert tipi Olçeklerin Çocuklarla kullaniminda yanit kategori sayisinin psikometrik Ozelliklere etkisi [effect of number of response options on psychometric properties of likert-type scale for used with children] (Master Thesis,. Hacettepe University.

- Arıkan, R. (2018). Anket yöntemi üzerinde bir degerlendirme. Haliç Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimleri. Dergisi, 1(1), 97–159.

- Guenaga, M., Eguíluz, A., Garaizar, P., & Gibaja, J. (2021). How do students develop computational thinking? Assessing early programmers in a maze-based online game. Computer Science Education, 1–31. [CrossRef]

- Kong, S.-C., & Liu, B. (2020). A performance-based assessment platform for developing computational thinking concepts and practices: EasyCode. Bulletin of the Technical Committee on Learning Technology (ISSN: 2306-0212), 20(2), 3–10. https://ieeecs-media.computer.org/tc-media/sites/5/2020/06/07190536/bulletin-tclt-2020-0201001.pdf.

- Bikmaz-Bilgen, Ö. (2019). Tamamlayici Ölçme ve Degerlendirme Teknikleri II: Portfolyo Degerlendirme [complementary measurement and evaluation techniques II: Portfolio evaluation]. In N. Dogan (Ed.), Egitimde Ölçme ve degerlendirme [measurement and evaluation in education] (pp. 182–214). Ankara: Pegem Akademi.

- Gültekin, S. (2017). Performans Dayanali Degerlendirme [performance based evaluation]. In R. N. Demirtas¸ li (Ed.), Egitimde Ölme ve de gerlendirme [measurement and evaluation in education] (pp. 233–256). Ankara: Ani Pub.

- Sahin, M. G. (2019). Performansa Dayali Degerlendirme. In B. Çetin (Ed.), Egitimde Ölme ve de gerlendirme [measurement and evaluation in education]. Ankara: Ani Pub.

- Grover, S., & Pea, R. (2013). Computational thinking in K–12: A review of the state of the field. Educational researcher, 42(1), 38–43.

- Mannila, L., Dagiene, V., Demo, B., Grgurina, N., Mirolo, C., Rolandsson, L., et al. (2014). Computational thinking in K-9 education. Proceedings of the working group reports of the 2014 on innovation & technology in computer science education conference. ITICSE ’14: Innovation and technology in computer science education conference 2014. [CrossRef]

- Kong, S.-C. (2019). Components and methods of evaluating computational thinking for fostering creative problem-solvers in senior primary school education. Computational thinking education (pp. 119–141). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Martins-Pacheco, L. H., von Wangenheim, C. A. G., & Alves, N. (2019). Assessment of computational thinking in K-12 context: Educational practices, limits and possibilities-a systematic mapping study. In Proceedings of the 11th international conference on computer supported education (CSEDU 2019) (pp. 292–303).

- Çoban, E., & Korkmaz, Ö. (2021). An alternative approach for measuring computational thinking: Performance-based platform. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 42, 100929.

- Newell, A., Perlis, A. J., & Simon, H. A. (1967). Computer science. Science, 157(3795), 1373–1374.

- Papert, S. (1980). Mindstorms: Children, computers, and powerful ideas Basic Books.

- Papert, S. (1996). An exploration in the space of mathematics educations. International Journal of Computers for Mathematical Learning, 1(1), 95–123. [CrossRef]

- Papert, S., & Harel, I. (1991). Situating constructionism. Constructionism, 36(2), 1–11.

- Turkle, S., & Papert, S. (1990). Epistemological pluralism: Styles and voices within the computer culture. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 16(1), 128–157. [CrossRef]

- Denning, P. J. (2009). The profession of IT Beyond computational thinking. Communications of the ACM, 52(6), 28–30. [CrossRef]

- Denning, P. J. (2010). Ubiquity symposium ’what is computation?’: Opening statement. Ubiquity, 2010 (November) http://doi.org/10.1145/1880066.1880067.

- Easton, T. A. (2006). Beyond the algorithmization of the sciences. Communications of the ACM, 49(5), 31–33. [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, E. W. (1974). Programming as a discipline of mathematical nature. The American Mathematical Monthly, 81(6), 608–612. [CrossRef]

- Guzdial, M. (2015). Learner-centered design of computing education: Research on computing for everyone. Synthesis Lectures on Human-Centered Informatics, 8(6), 1–165. [CrossRef]

- Lee, I., Martin, F., Denner, J., Coulter, B., Allan, W., Erickson, J., et al. (2011). Computational thinking for youth in practice, 2 pp. 32–37). ACM Inroads. [CrossRef]

- Shute, V. J., Sun, C., & Asbell-Clarke, J. (2017). Demystifying computational thinking. Educational Research Review, 22, 142–158. [CrossRef]

- Tedre, M., & Denning, P. J. (2016). The long quest for computational thinking. In Proceedings of the 16th Koli calling international conference on computing education research (pp. 120–129). [CrossRef]

- Lu, J. J., & Fletcher, G. H. L. (2009). Thinking about computational thinking. In Proceedings of the 40th ACM technical symposium on computer science education - SIGCSE ’09. The 40th ACM technical symposium. [CrossRef]

- Aho, A. V. (2012). Computation and computational thinking. The Computer Journal, 55(7), 832–835. 10.1093/comjnl/bxs074.

- Kong, S.-C., Abelson, H., & Lai, M. (2019). Introduction to computational thinking education. Computational thinking education (pp. 1–10). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Csizmadia, Andrew, Curzon, Paul, Dorling, Mark, Humphreys, Simon, Ng, Thomas, Selby, Cynthia, & Woollard, John (2015). Computational thinking - a guide for teachers. Swindon: Computing At School. ttps://eprints.soton.ac.uk/424545/. (Accessed 11 May 2020).

- CSTA. (2011). Operational definition of computational thinking for K–12 education. National Science Foundation.

- ISTE standards for students. Retrieved April 14, 2020, from http://www.iste.org/standards/standards/for-students-2016.

- Riley, D. D., & Hunt, K. A. (2014). Computational thinking for the modern problem solver. CRC Press. ISBN: 978-1-4665-8777-9.

- NRC. (2010). Committee for the workshops on computational thinking. Paper presented at the. In Report of a workshop on the scope and nature of computational thinking. Natl Academy Pr.

- Barr, V., & Stephenson, C. (2011). Bringing computational thinking to K-12: What is Involved and what is the role of the computer science education community? ACM Inroads, 2(1), 48–54. [CrossRef]

- Brennan, K., & Resnick, M. (2012). New frameworks for studying and assessing the development of computational thinking In Proceedings of the 2012 annual meeting of the American educational research association (p. 25). Retrieved from http://scratched.gse.harvard.edu/ct/files/AERA2012.pdf.

- Gouws, L. A., Bradshaw, K., & Wentworth, P. (2013). Computational thinking in educational activities: An evaluation of the educational game light-bot. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM conference on Innovation and technology in computer science education (pp. 10–15). [CrossRef]

- Bers, M. U., Flannery, L., Kazakoff, E. R., & Sullivan, A. (2014). Computational thinking and tinkering: Exploration of an early childhood robotics curriculum. Computers & Education, 72, 145–157. [CrossRef]

- Zapata-Ros, M. (2015). Pensamiento computacional: Una nueva alfabetización digital [computational thinking: A new digital literacy]. Distance Education Journal, 46. Retrieved from https://revistas.um.es/red/article/view/240321.

- Anderson, N. D. (2016). A call for computational thinking in undergraduate psychology. Psychology Learning & Teaching, 15(3), 226–234, 10.1177/1475725716659252.

- Google for education: Computational thinking. Retrieved February 21, 2020, from https://edu.google.com/resources/programs/exploring-computational-thinking/.

- Dierbach, C., Hochheiser, H., Collins, S., Jerome, G., Ariza, C., Kelleher, T., et al. (2011). A model for piloting pathways for computational thinking in a general education curriculum. In Proceedings of the 42nd ACM technical symposium on Computer science education (pp. 257–262). [CrossRef]

- Berland, M., & Lee, V. R. (2011). Collaborative strategic board games as a site for distributed computational thinking. International Journal of Game-Based Learning (IJGBL), 1(2), 65–81. http://doi.org/10.4018/ijgbl.2011040105.

- Akkaya, A. (2018). The effects of serious games on students’ conceptual knowledge of object-oriented programming and computational thinking skills (Master Thesis. Bogaziçi University.

- CAS: https://community.computingatschoolorg.uk/resources/2324; K12CS: https://k12cs.org.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).