3.1. Chemistry

All nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopic data for 1H and 13C were recorded in deuterated chloroform, CDCl3 and deuterated methanol CD3OD using tetramethylsilane as a standard at room temperature on Bruker Avance 300 and 600 MHz spectrometers. For the full characterization of the targeted oximes, the additional techniques 2D-CH correlation (HSQC) and 2D-HH-COSY were used. The following abbreviations were used in the NMR spectra: s (singlet), d (doublet), t (triplet), q (quartet), dd (doublet of doublets) and m (multiplet). Chemical shifts were reported in parts per million (ppm). High-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) analyses were carried out on a mass spectrometer (MALDI TOF/TOF analyzer) equipped with an Nd:YAG laser operating at 355 nm with a fitting rate of 200 Hz in the positive (H+) or negative (-H) ion reflector mode. All of the compounds tested for reversible inhibition and oxime-assisted reactivation of cholinesterases were >95% pure by High Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS) or HPLC analyses (see Supplemental Information). The results of HRMS and HPLC analyses are included in the Supporting Information. All used solvents for the synthesis were purified by distillation and were commercially available. Anhydrous magnesium sulfate, MgSO4, was used for drying organic layers after extractions. The column chromatography was performed on columns with silica gel (Fluka 0.063–0.2 nm and Fluka 60 Å, technical grade) using the appropriate solvent system. Abbreviations used in experimental procedures were ACN – acetonitrile, EtOAc – ethyl acetate, PE – petroleum ether, E – diethylether, EtOH – ethanol, DCM – dichloromethane, DMF – dimethylformamide, POCl3 – phosphoryl chloride, NaOH – sodium hydroxide. All solvents were removed from the solutions by rotary evaporator under reduced pressure. The initial phosphonium salts were prepared in the laboratory from the corresponding bromides, while the other starting compounds used were purchased chemicals.

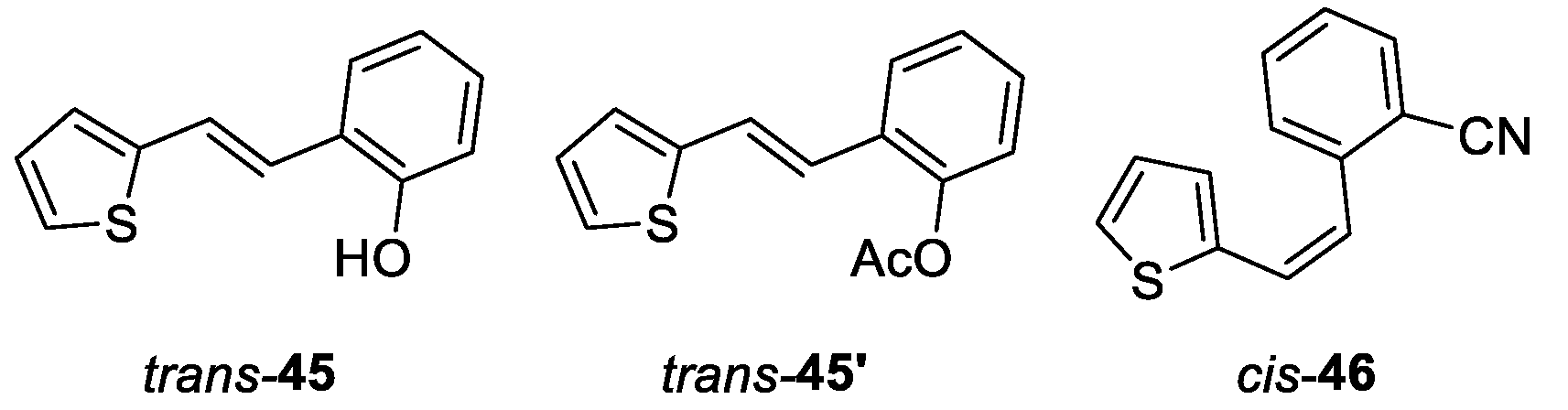

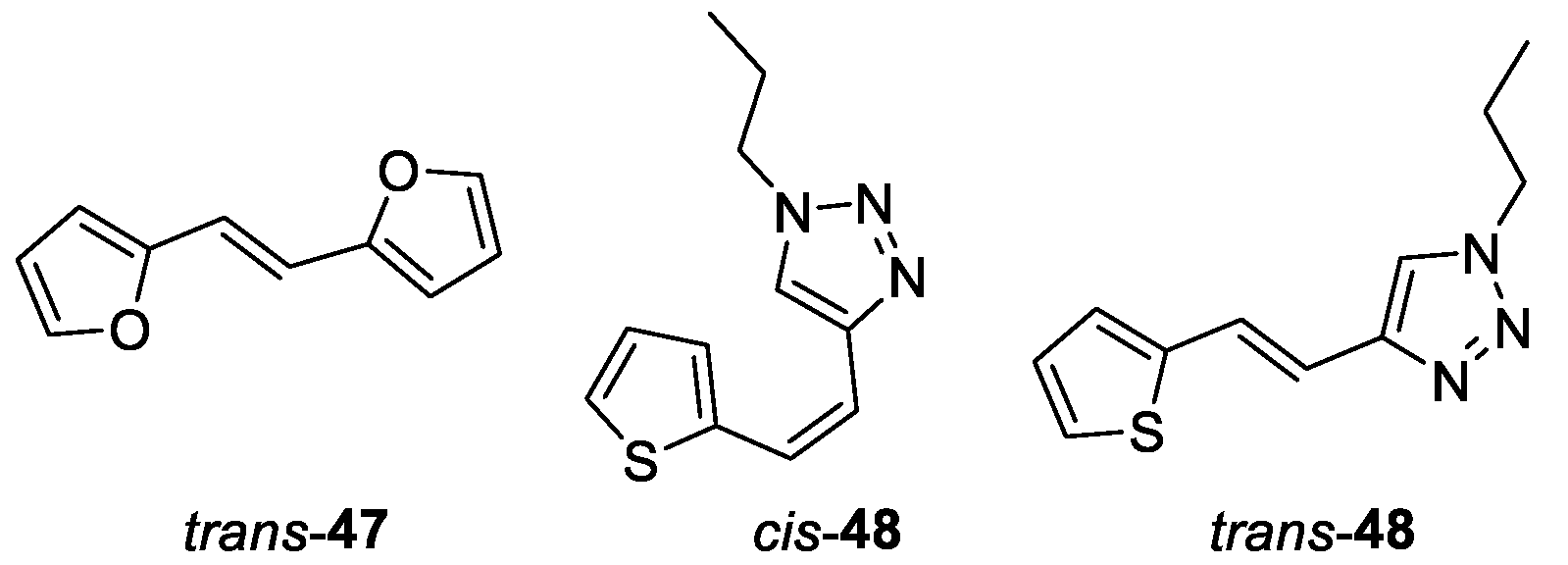

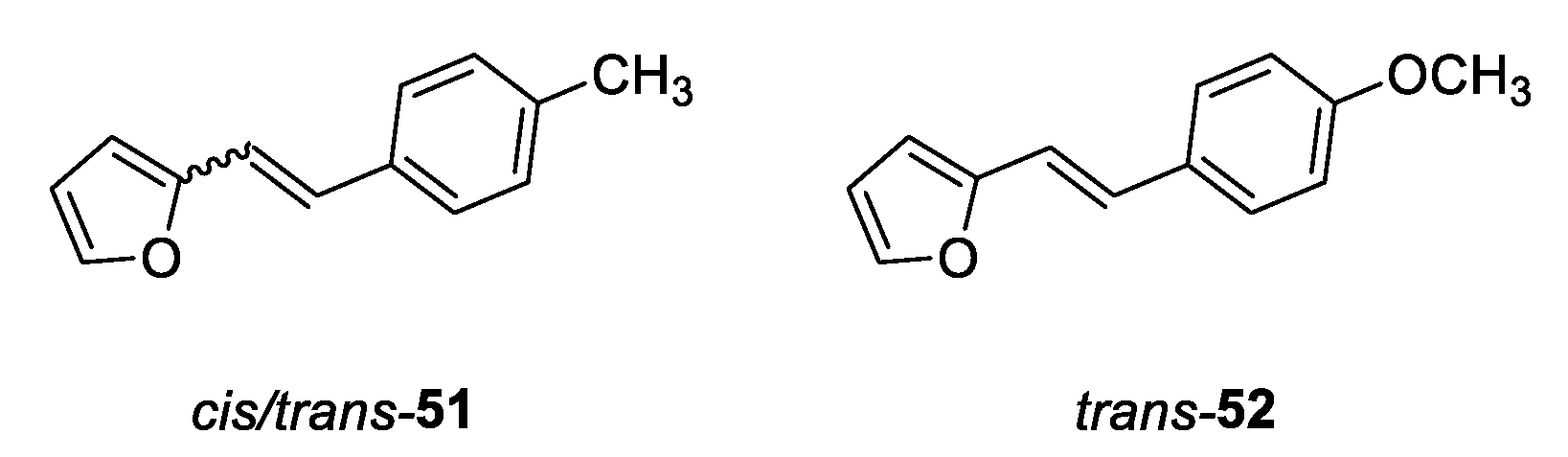

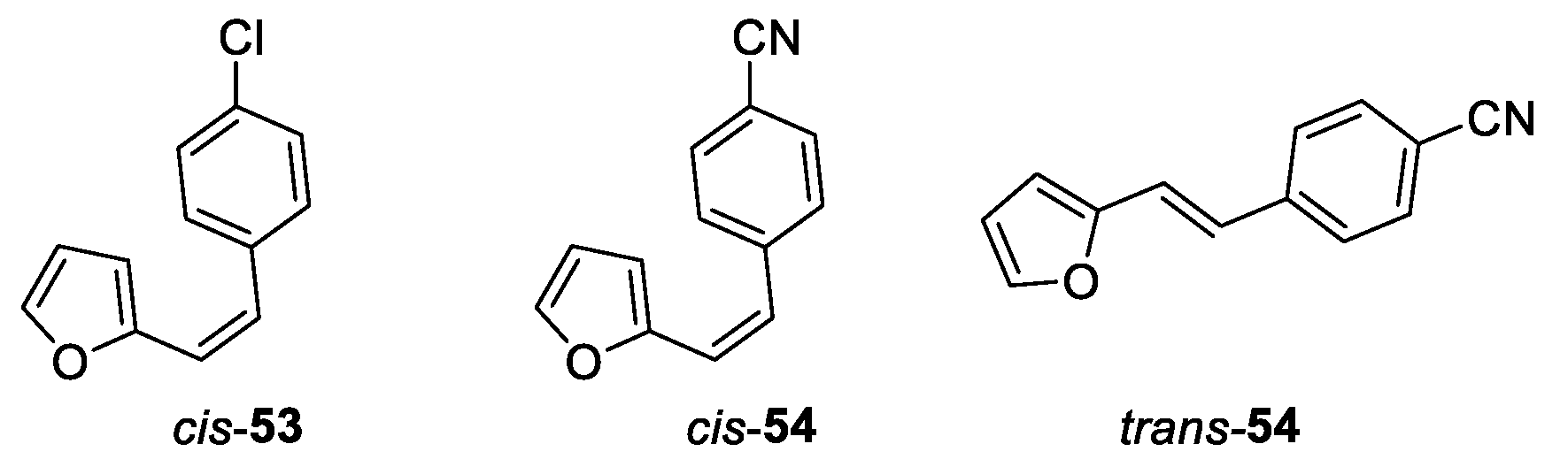

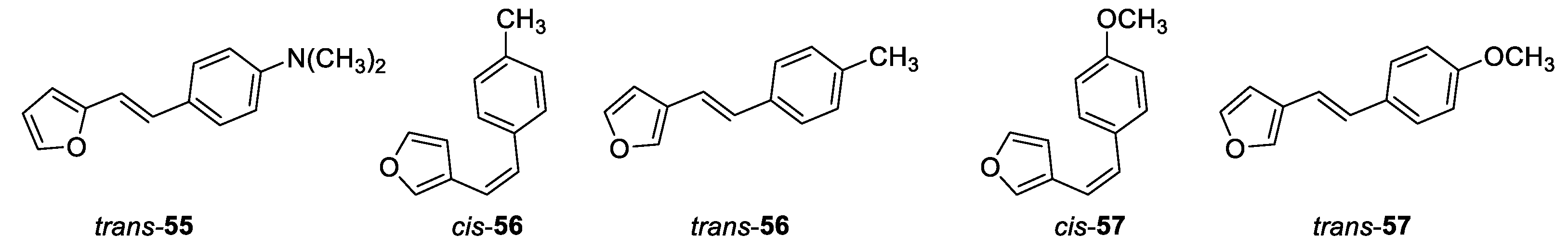

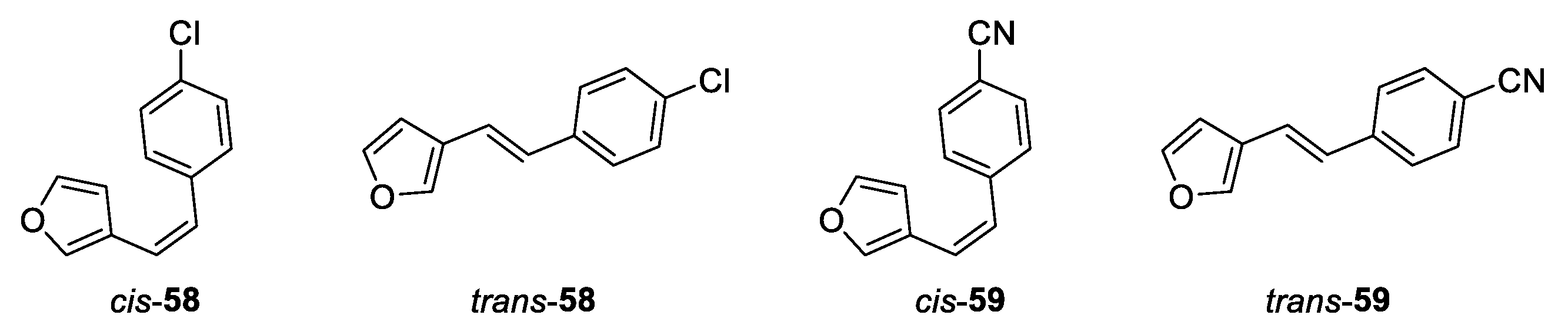

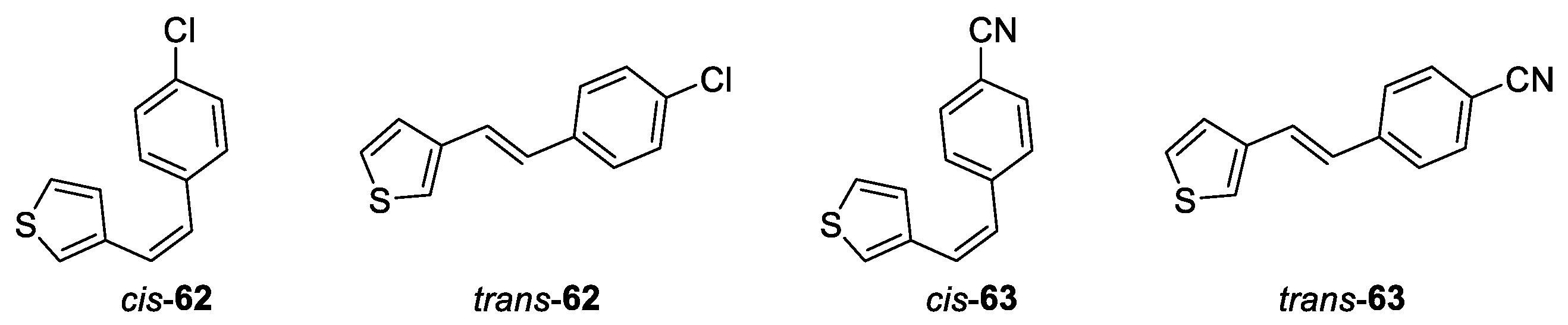

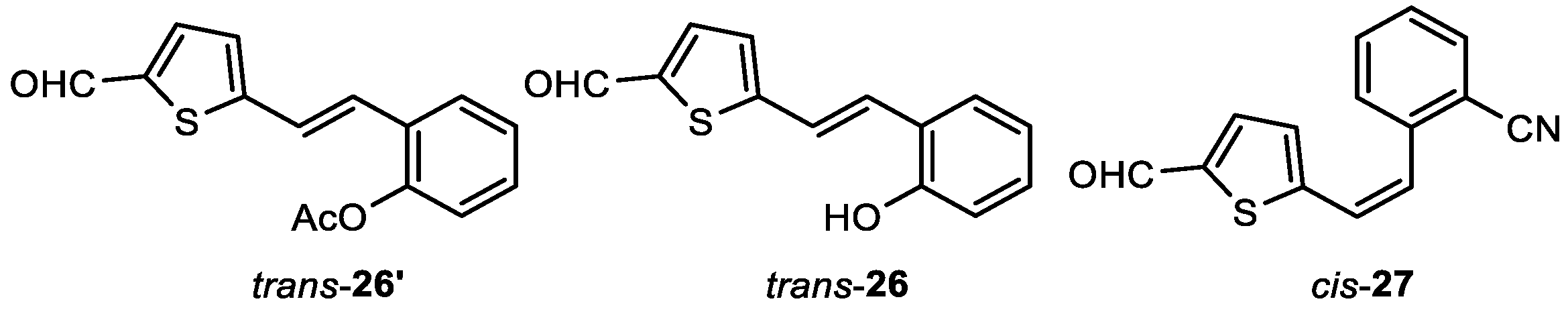

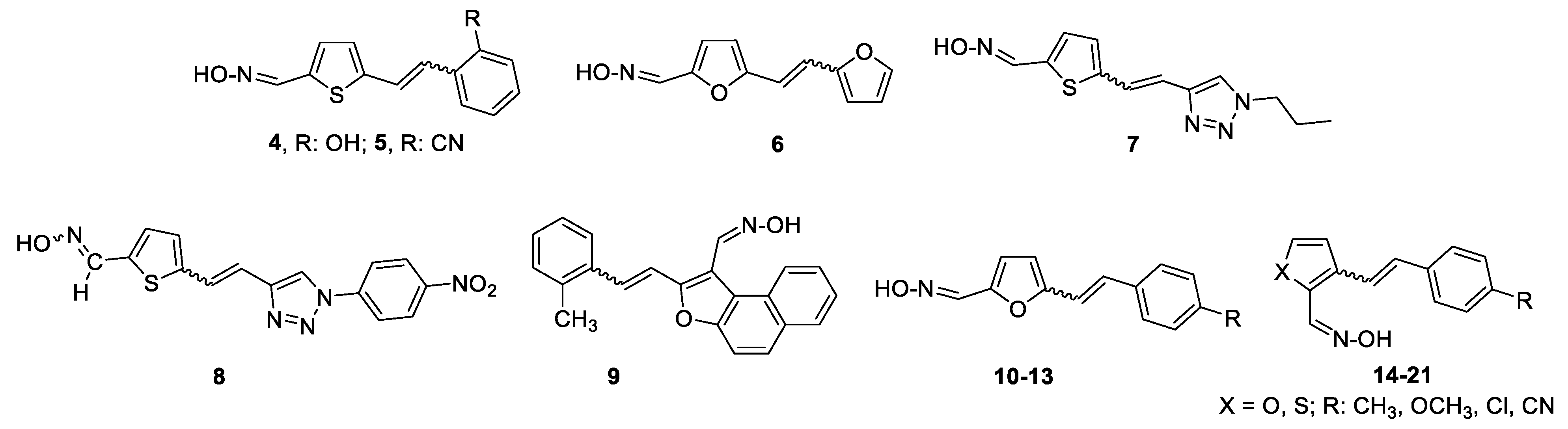

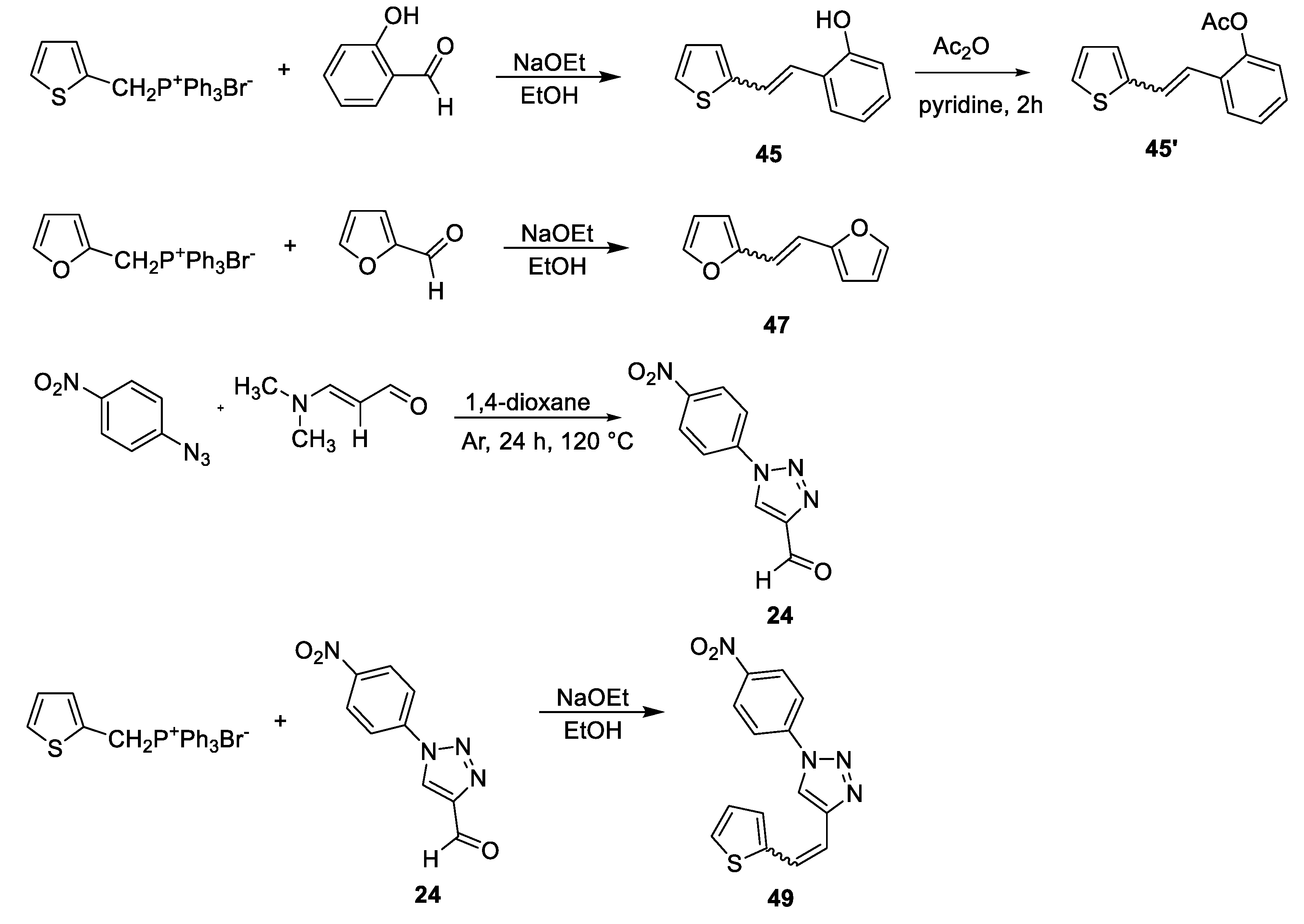

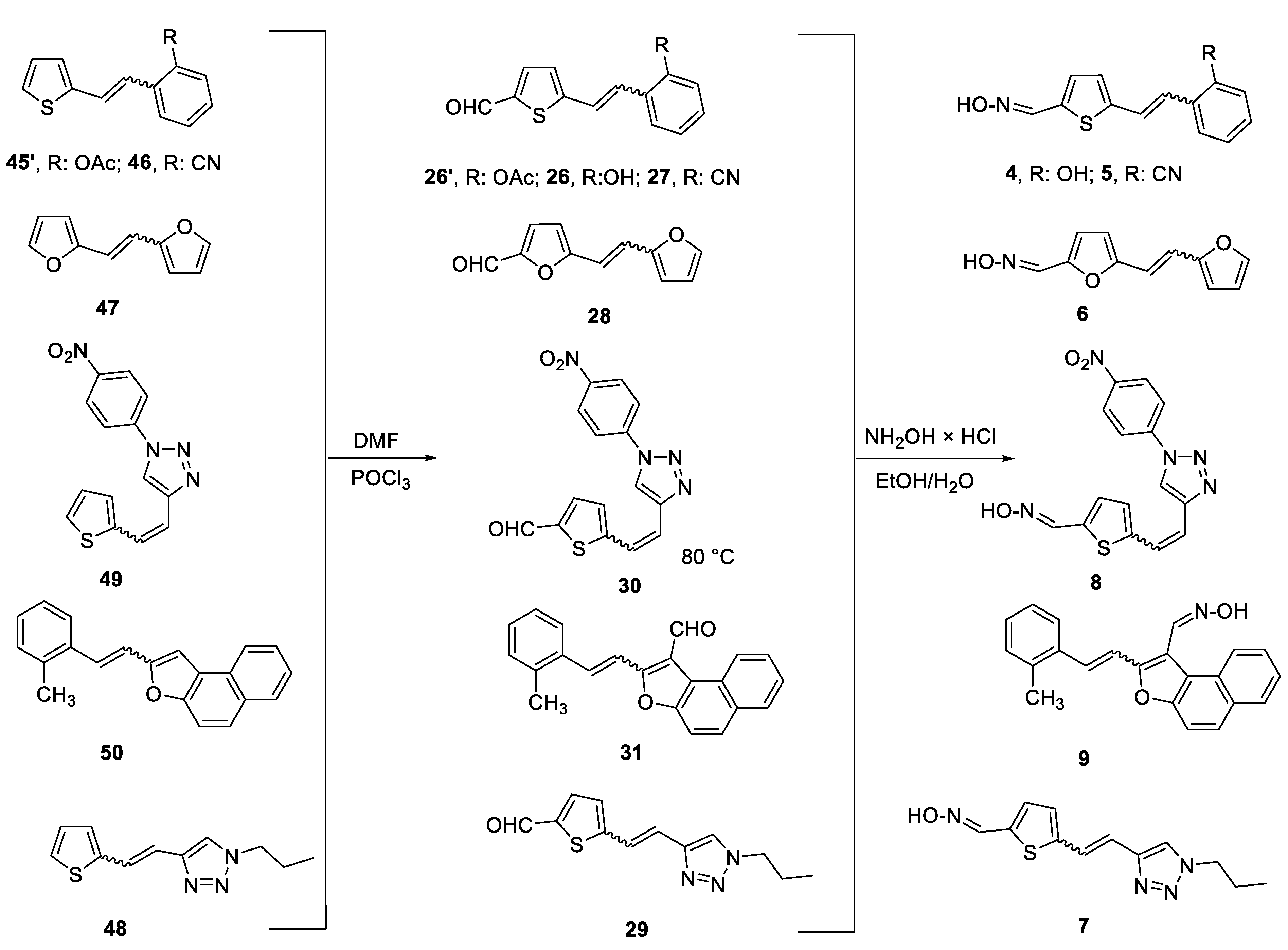

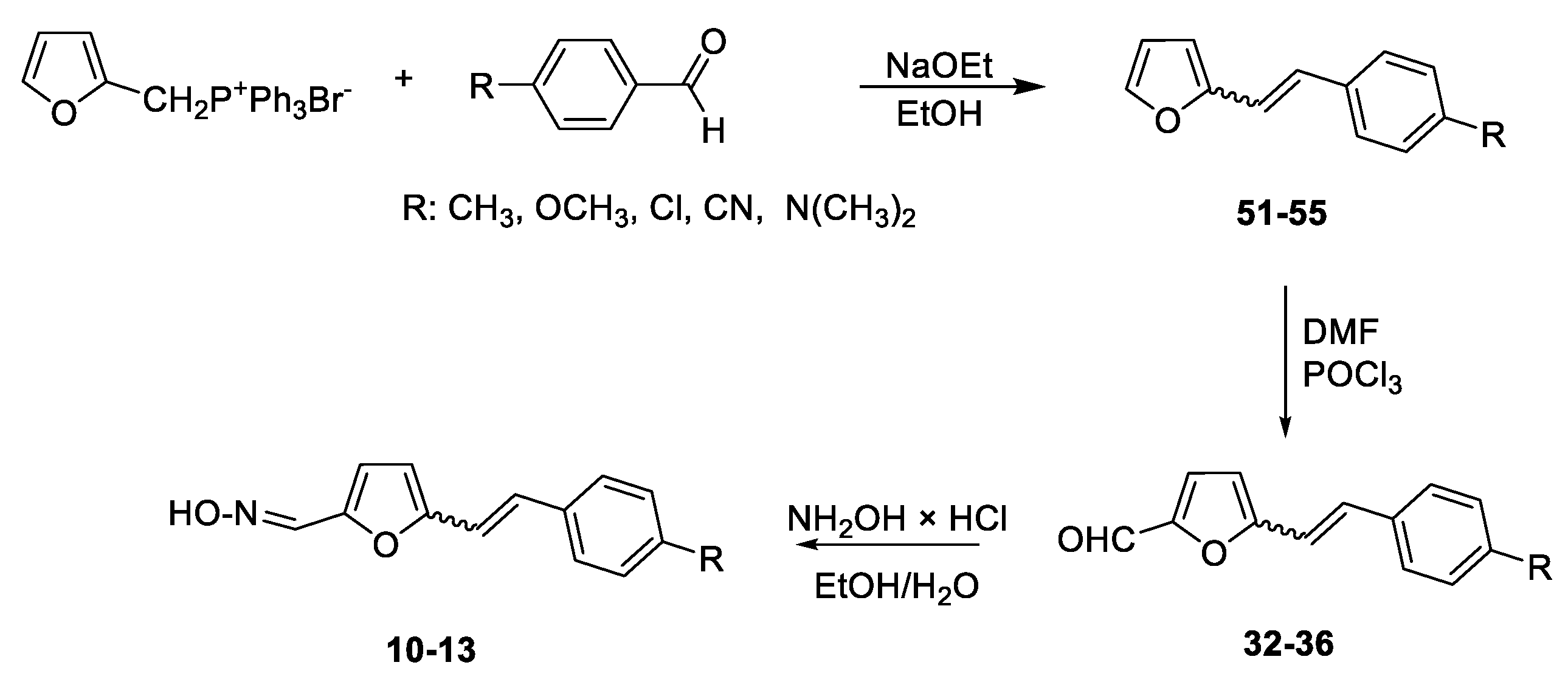

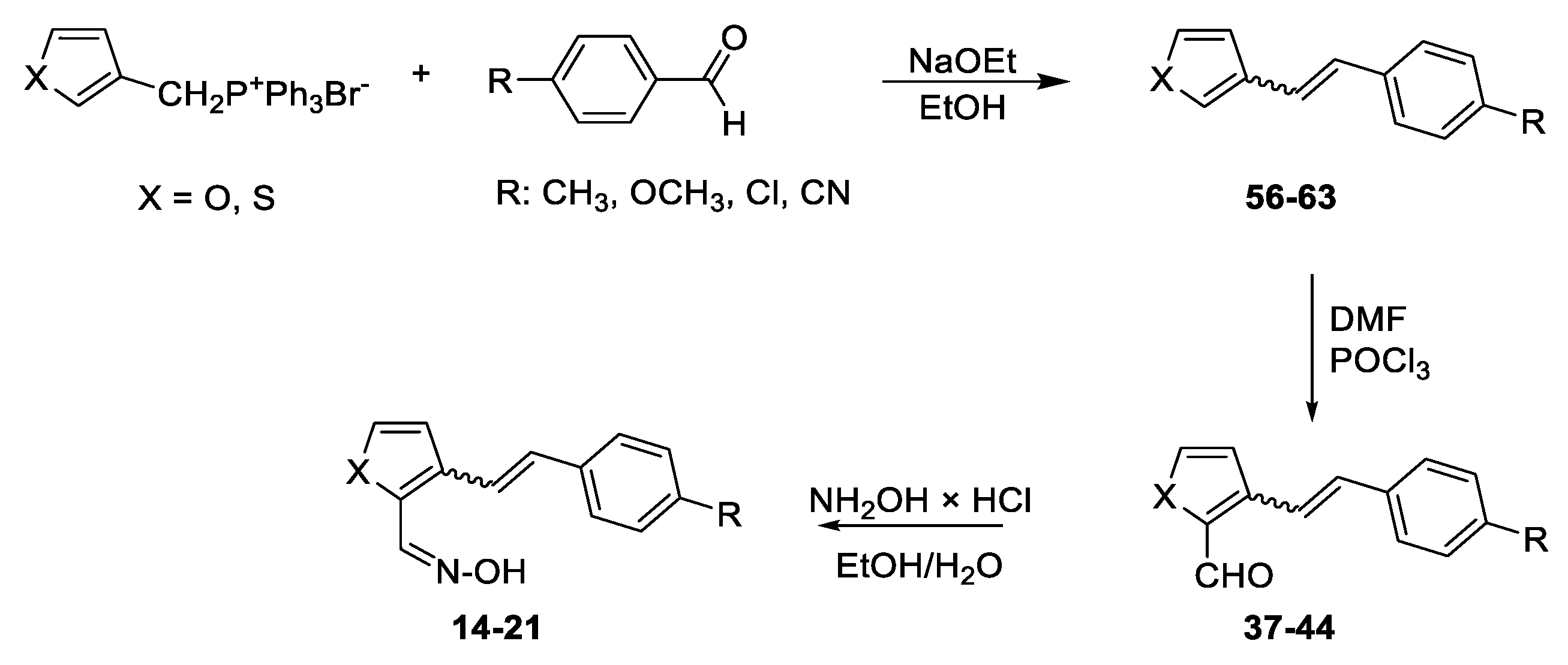

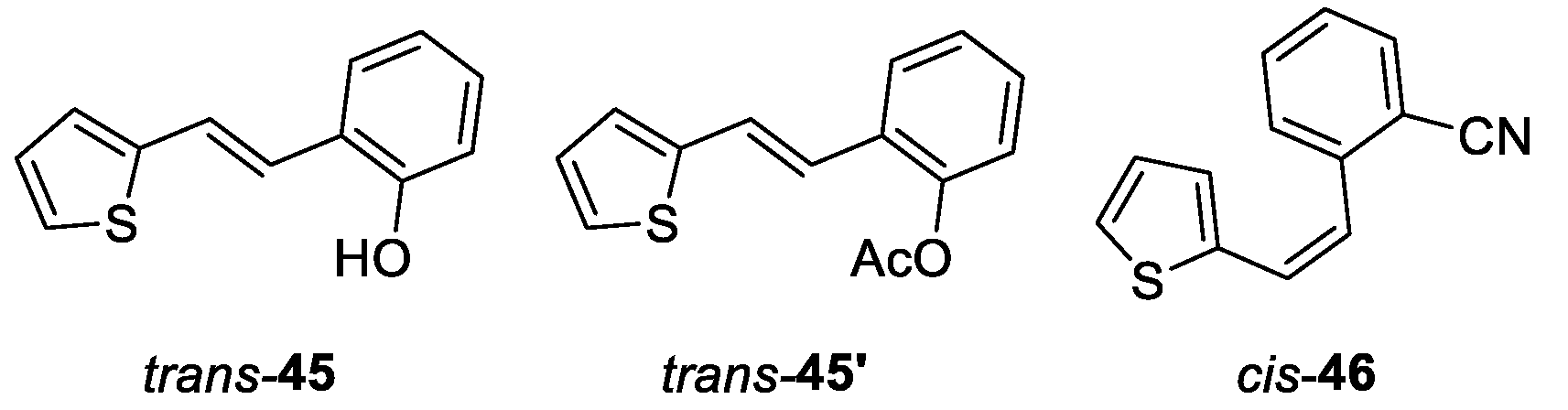

Heterostilbenes 45–63 were obtained as mixtures of cis- and trans-isomers ((11–97%) except in the case of 45, 45’, 47, 50 and 55 where only a trans-isomer was formed, or for the heterostilbene 49 when only a cis-isomer was obtained) using Wittig reaction. The reaction apparatus was purged with N2 for 15 min before adding the reactants. The reactions were carried out in three-necked flasks (100 mL) equipped with a chlorine-calcium tube and an N2 balloon connected. Phosphonium salts (5 mmol) were added to the 40 mL of EtOH, and mixtures were stirred with a magnetic stirrer. Solution of sodium ethoxide (5 mmol, 1.1 eq of Na dissolved in 10 mL of absolute ethanol) was added in strictly anhydrous conditions under N2 dropwise. The corresponding aldehydes (5 mmol) were then added to the reaction mixtures, which were allowed to stir for 24 h at room temperature. The reaction mixtures were evaporated on a vacuum evaporator and dissolved in toluene. Products were then extracted with toluene (3 × 15 mL). The organic layers were dried under anhydrous MgSO4. Products 45–63 were isolated by repeated column chromatography on silica gel using PE/E, PE/DCM, and E/EtOAc solvent systems. The first isomer to eluate was cis-isomer (but in some cases was not isolated), and the trans-isomer was isolated in the last fractions. The spectroscopic characterization of new isolated heterostilbenes is given below.

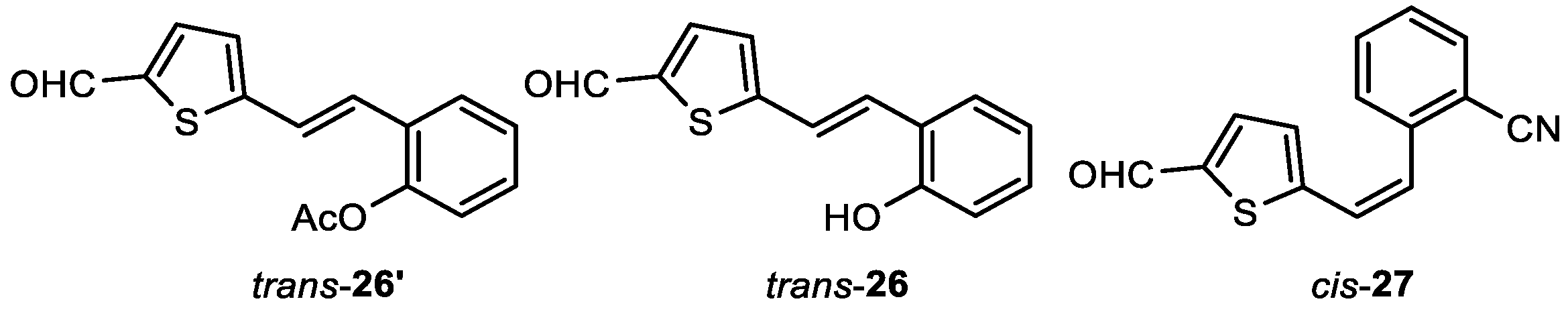

Compound trans-45 was converted to the aldehyde by Vielsmeier formylation, however, it did not give the product. After that, protection of its OH group was carried out in a round flask (25 mL) using acetic anhydride (1.5 mL) at room temperature overnight in pyridine. After that, a mixture of water, toluene and acetone (1:3:3) was added, and the reaction mixture was evaporated under reduced pressure, and a yellow solid remained in the flask (trans-45').

(

E)-2-(2-(thiophen-2-yl)vinyl)phenol (

trans-

45) [

45] 495 mg, 82% isolated yield; white powder; R

f (PE/DCM (50%)) = 0.33; UV (ACN)

λmax/nm (

ε/dm

3mol

-1cm

-1) 335 (27412);

1H NMR (CDCl

3, 600 MHz)

δ/ppm: 7.46 (dd,

J = 7.7, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.28 (d,

J = 16.1 Hz, 1H), 7.20 – 7.16 (m, 2H), 7.10 (t,

J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.07 (d,

J = 3.7 Hz, 1H), 6.99 (dd,

J = 5.1, 3.5 Hz, 1H), 6.93 (t,

J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 6.78 (dd,

J = 8.1, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 4.97 (s, 1H);

13C NMR (CDCl

3, 150 MHz)

δ/ppm: 152.9, 143.3, 128.6, 127.6, 127.2, 126.0, 124.4, 124.3, 123.3, 122.7, 121.2, 115.9; MS (ESI) (

m/z) (%, fragment): 202 (25), 105 (100).

(E)-2-(2-(thiophen-2-yl)vinyl)phenyl acetate (trans-45’): 286 mg, 95% isolated yield; colorless oil; Rf (DCM) = 0.75; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.62 (dd, J = 7.6, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.28 – 7.20 (m, 4H), 7.08 – 7.06 (m, 2H), 7.00 (dd, J = 5.2, 3.7 Hz, 1H), 6.94 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H), 2.37 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 169.3, 148.1, 142.7, 129.6, 128.4, 127.6, 126.6, 126.3, 124.7, 124.0, 122.8, 122.8, 121.5, 20.9.

(Z)-2-(2-(thiophen-2-yl)vinyl)benzonitrile (cis-46): 350 mg, 50% isolated yield; colorless oil; Rf (DCM) = 0.65; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.71 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.57 – 7.53 (m, 2H), 7.42 – 7.39 (m, 1H), 7.12 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 6.96 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H), 6.93 (d, J = 12.1 Hz, 1H), 6.90 (dd, J = 4.9, 3.6 Hz, 1H), 6.62 (d, J = 12.1 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 182.9, 147.6, 143.5, 140.0, 135.9, 133.5, 133.1, 130.3, 129.7, 128.9, 128.8, 126.4, 117.4, 112.3.

(E)-1,2-di(furan-2-yl)ethene (trans-47): 93 mg, 20% isolated yield; colorless powder; Rf (PE) = 0.58; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.42 (d, J = 17.7 Hz, 1H), 7.34 (d, J = 17.7 Hz, 1H), 6.81 (t, J = 19.4 Hz, 2H), 6.42 – 6.40 (m, 2H), 6.32 (d, J = 3.2 Hz, 2H).

(

Z)-1-propyl-4-(2-(thiophen-2-yl)vinyl)-1

H-1,2,3-triazole (

cis-

48) [

68]: 110 mg, 48% isolated, colorless oil; R

f (PE/E (40%)) = 0.34; UV (ethanol, 96%)

λmax/nm (

ε/dm

3mol

-1cm

-1) 296 (16418), 310 (14455, sh);

1H NMR (CDCl

3, 300 MHz)

δ /ppm: 7.53 (s, 1H), 7.25 (d,

J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 7.22 (d,

J = 3.7 Hz, 1H), 6.99 (dd,

J = 4.9, 3.4 Hz, 1H), 6.70 (d,

J = 12.1 Hz, 1H), 6.54 (d,

J = 12.1 Hz, 1H), 4.27 (t,

J = 14.2 Hz, 3H), 1.93 – 1.87 (m, 2H), 0.94 (t,

J = 14.6 Hz, 3H);

13C NMR (CDCl

3, 75 MHz)

δ /ppm: 143.8, 139.5, 128.5, 127.1, 126.0, 123.8, 122.1, 118.3, 51.9, 23.74, 11.1.

(

E)-1-propyl-4-(2-(thiophen-2-yl)vinyl)-1

H-1,2,3-triazole (

trans-

48) [

69]: 20 mg, 10% isolated; white powder; R

f (PE/E (40%)) = 0.29; UV (ethanol, 96%)

λmax/nm (

ε/dm

3mol

-1cm

-1) 314 (30210);

1H NMR (CDCl

3, 600 MHz)

δ /ppm: 7.51 (s, 1H), 7,44 (d,

J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 7.20 (d,

J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.07 (d,

J = 3.5 Hz, 1H), 7.00 (dd,

J = 5.1, 3.6 Hz, 1H), 6.89 (d,

J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 4.33 (t,

J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 1.95 (m,

J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 0.98 (t,

J = 7.4 Hz, 3H);

13C NMR (CDCl

3, 150 MHz)

δ /ppm: 145.2, 141.7, 127.1, 125.9, 124.2, 123.1, 119.6, 115.7, 51.4, 23.2, 10.6.

(Z)-1-(4-nitrophenyl)-4-(2-(thiophen-2-yl)vinyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazole (cis-49): 85 mg, 42% isolated yield; yellow oil; Rf (E) = 0.85; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 8.41 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 8.10 (s, 1H), 7.94 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 7.32 (d, J = 5.5 Hz, 1H), 7.28 (d, J = 3.3 Hz, 1H), 7.06 (t, J = 4.1 Hz, 1H), 6.86 (d, J = 12.2 Hz, 1H), 6.59 (d, J = 12.2 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz) δ/ppm: 147.2, 145.3, 141.5, 138.9, 129.2, 127.3, 126.6, 125.7, 125.6, 120.4, 119.8, 116.7.

(E)-2-(2-methylstyryl)naphtho[2,1-b]furan (trans-50): 210 mg, 95% isolated yield; yellow powder; Rf (PE/E (50%)) = 0.95; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ/ppm: 8.12 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.93 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.74 – 7.55 (m, 5H), 7.48 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.25 – 7.18 (m, 4H), 7.01 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 2.50 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz) δ/ppm: 154.9, 152.4, 136.2, 135.6, 130.6, 130.4, 128.8, 127.9, 127.5, 127.1, 126.2, 126.2, 125.6, 125.5, 125.0, 124.6, 124.5, 123.5, 117.5, 112.1, 104.2, 19.9.

(E)-2-(4-methoxystyryl)furan (trans-52): 750 mg, 36% isolated yield; white powder; Rf (PE/E (2%)) = 0.31; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.39 (d, J = 9.7 Hz, 2H), 6.99 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H), 6.87 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 6.75 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H), 6.41 – 6.39 (m, 1H), 6.29 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 3.81 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz) δ/ppm: 159.4, 153.7, 141.7, 129.8, 127.5, 126.7, 114.6, 114.5, 111.5, 107.7, 55.3.

(Z)-2-(4-chlorostyryl)furan (cis-53): 240 mg, 23% isolated yield; colorless oil; Rf (PE/E (2%)) = 0.95; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.38 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.28 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.29 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 6.40 (d, J = 12.5 Hz, 1H), 6.35 (d, J = 12.5 Hz, 1H), 6.35 – 6.32 (m, 1H), 6.26 (d, J = 3.2 Hz, 1H).

(Z)-4-(2-(furan-2-yl)vinyl)benzonitrile (cis-54): 170 mg, 9% isolated yield; colorless oil; Rf (PE/E (30%)) = 0.19; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.55 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 7.50 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.30 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 6.44 (d, J = 12.4 Hz, 1H), 6.40 (d, J = 12.5 Hz, 1H), 6.37 – 6.35 (m, 1H), 6.31 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 1H).

(E)-4-(2-(furan-2-yl)vinyl)benzonitrile (trans-54): 150 mg, 8% isolated yield; white powder; Rf (PE/E (30%)) = 0.22; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.54 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 7.51 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 7.44 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 7.01 (d, J = 16.3 Hz, 1H), 6.97 (d, J = 16.3 Hz, 1H), 6.45 (d, J = 3.3 Hz, 1H), 6.36 (dd, J = 1.9, 3.3 Hz, 1H).

(E)-4-(2-(furan-2-yl)vinyl)-N,N-dimethylaniline (trans-55): 79 mg, 11% isolated yield; yellow powder; Rf (PE/E (5%)) = 0.36; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.44 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 7.39 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 6.73 – 6.68 (m, 2H), 6.42 (d, J = 12.9 Hz, 1H), 6.33 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 2H), 6.18 (d, J = 12.9 Hz, 1H), 2.98 (s, 6H).

(Z)-3-(4-methylstyryl)furan (cis-56): 214 mg, 40% isolated yield; yellow oil; Rf (PE/E (10%)) = 0.86; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.36 (s, 1H), 7.22 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 7.23 (d, J = 1.4 Hz, 1H), 7.11 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 6.51 (d, J = 12.2 Hz, 1H), 6.33 (d, J = 12.2 Hz, 1H), 6.16 (d, J = 1.4 Hz, 1H), 2.35 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 142.5, 141.9, 136.9, 134.9, 129.5, 128.9, 128.6, 122.4, 119.5, 110.3, 21.2.

(E)-3-(4-methylstyryl)furan (trans-56): 219 mg, 41% isolated yield; white powder; Rf (PE/E (10%)) = 0.81; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.51 (s, 1H), 7.40 (t, J = 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.34 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 7.14 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 6.92 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 6.78 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 6.65 (d, J = 1.7 Hz, 1H), 2.34 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 143.6, 140.7, 137.2, 134.6, 129.3, 128.4, 126.0, 124.7, 117.4, 104.4, 21.2.

(Z)-3-(4-methoxylstyryl)furan (cis-57): 160 mg, 50% isolated yield; white oil; Rf (PE) = 0.80; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.36 (s, 1H), 7.27 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), , 6.85 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 6.48 (d, J = 12.8 Hz, 1H), 6.31 (d, J = 12.8 Hz, 1H), 6.18 (s, 1H), 3.81 (s, 3H).

(E)-3-(4-methoxylstyryl)furan (trans-57): 217 mg, 30% isolated yield; white powder; Rf (PE) = 0.75; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.50 (s, 1H), 7.38 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 3H), 6.88 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 6.84 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H), 6.76 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H), 6.64 (s, 1H), 3.82 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz) δ/ppm: 143.6, 140.5, 131.3, 130.2, 127.9, 127.3, 124.7, 116.4, 114.2, 107.4, 55.3.

(Z)-3-(4-chlorostyryl)furan (cis-58): 256 mg, 63% isolated yield; colorless oil; Rf (PE) = 0.64; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.36 (s, 1H), 7.30 – 7.26 (m, 4H), 7.25 (d, J = 1.3 Hz, 1H), 6.47 (d, J = 12.1 Hz, 1H), 6.39 (d, J = 12.1 Hz, 1H), 6.11 (d, J = 1.3 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 142.7, 142.2, 136.3, 132.9, 130.0, 128.4, 128.1, 121.9, 120.8, 110.0.

(E)-3-(4-chlorostyryl)furan (trans-58): 95 mg, 21% isolated yield; white powder; Rf (PE) = 0.43; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.54 (s, 1H), 7.41 (d, J = 1.1 Hz, 1H), 7.37 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.29 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 6.94 (d, J = 16.3 Hz, 1H), 6.75 (d, J = 16.3 Hz, 1H), 6.64 (d, J = 1.1 Hz, 1H).

(Z)-4-(2-(furan-3-yl)vinyl)benzonitrile (cis-59): 278 mg, 61% isolated yield; colorless oil; Rf (PE/E (5%)) = 0.54; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.60 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.44 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.39 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.27 (s, 1H), 6.53 (d, J = 12.4 Hz, 1H), 6.48 (d, J = 12.4 Hz, 1H), 6.06 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 143.1, 142.7, 132.5, 132.1, 129.5, 127.4, 126.5, 124.0, 122.7, 121.6, 109.8.

(E)-4-(2-(furan-3-yl)vinyl)benzonitrile (trans-59): 134 mg, 30% isolated yield; white powder; Rf (PE/E (5%)) = 0.33; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.61 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.51 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.60 (s, 1H), 7.44 (d, J = 1.3 Hz, 1H), 7.09 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 6.79 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 6.66 (d, J = 1.3 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 144.1, 142.1, 141.9, 134.5, 126.5, 124.0, 122.2, 119.1, 110.3, 107.2.

(Z)-3-(4-methylstyryl)thiophene (cis-60): 377 mg, 44% isolated yield; colorless oil; Rf (PE) = 0.32; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.19 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 7.14 – 7.11 (m, 2H), 7.09 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 6.89 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 6.54 (d, J = 12.3 Hz, 1H), 6.49 (d, J = 12.3 Hz, 1H), 2.34 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 138.4, 136.9, 134.8, 129.5, 129.0, 128.6, 128.1, 124.8, 123.8, 123.8, 21.3.

(E)-3-(4-methylstyryl)thiophene (trans-60): 289 mg, 33% isolated yield; white powder; Rf (PE) = 0.21; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.37 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 7.33 – 7.29 (m, 2H), 7.24 – 7.22 (m, 1H), 7.15 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.08 (d, J = 16.3 Hz, 1H), 6.92 (d, J = 16.3 Hz, 1H), 2.35 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 140.3, 137.3, 134.6, 129.4, 128.6, 126.2, 126.1, 124.9, 122.0, 121.9, 21.2.

(Z)-3-(4-methoxystyryl)thiophene (cis-61): 244 mg, 40% isolated yield; colorless oil; Rf (PE) = 0.80; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.37 (s, 1H), 7.26 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 2H), 7.25 (t, J = 1.7 Hz, 1H), 6.85 (d, 1H, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 6.48 (d, J = 11.8 Hz, 1H), 6.31 (d, J = 11.8 Hz, 1H), 6.18 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 3.81 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 158.7, 142.5, 141.8, 130.3, 129.8, 129.2, 122.4, 118.9, 113.6, 110.3, 100.0, 55.2.

(E)-3-(4-methoxystyryl)thiophene (trans-61): 248 mg, 41% isolated yield; white powder; Rf (PE) = 0.76; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.41 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 7.34 – 7.29 (m, 2H), 7.22 – 7.20 (m, 1H), 7.00 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 6.91 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 6.89 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 3.82 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz) δ/ppm: 159.2, 140.4, 130.2, 128.2, 127.5, 126.1, 124.9, 121.5, 120.9, 114.2, 55.3.

(Z)-3-(4-chlorostyryl)thiophene (cis-62): 222 mg, 41% isolated yield; colorless oil; Rf (PE) = 0.64; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.23 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 7.21 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.15 (dd, J = 5.1, 2.9 Hz, 1H), 7.11 (d, J = 2.9 Hz, 1H), 6.85 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 6.56 (d, J = 12.1 Hz, 1H), 6.48 (d, J = 12.1 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 137.9, 136.2, 132.9, 130.1, 128.5, 128.2, 127.8, 125.2, 125.1, 124.3.

(E)-3-(4-chlorostyryl)thiophene (trans-62): 186.1 mg, 34% isolated yield; white powder; Rf (PE) = 0.49; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.40 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 7.33 – 7.27 (m, 5H), 7.09 (d, J = 16.3 Hz, 1H), 6.89 (d, J = 16.3 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 139.8, 135.9, 133.0, 128.8, 127.4, 127.3, 126.3, 124.8, 123.5, 122.7.

(Z)-4-(2-(thiophen-3-yl)vinyl)benzonitrile (cis-63): 474 mg, 73% isolated yield; colorless oil; Rf (PE/E (15%)) = 0.69; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.56 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.39 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 7.18 (dd, J = 4.9, 3.0 Hz, 1H), 7.13 (d, J = 2.9 Hz, 1H), 6.81 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 6.68 (d, J = 12.1 Hz, 1H), 5.52 (d, J = 12.1 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz) δ/ppm: 142.6, 137.3, 132.0, 132.1, 129.5, 127.5, 127.1, 125.6, 125.0, 118.9, 110.6.

(E)-4-(2-(thiophen-3-yl)vinyl)benzonitrile (trans-63): 158 mg, 23% isolated yield; white powder; Rf (PE/E (15%)) = 0.48; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.62 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.54 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.36 (s, 2H), 7.26 (s, 1H), 7.23 (d, J = 16.3 Hz, 1H), 6.93 (d, J = 16.3 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz) δ/ppm: 142.0, 139.2, 132.5, 126.7, 126.6, 126.6, 126.4, 124.8, 124.3, 119.1, 110.4.

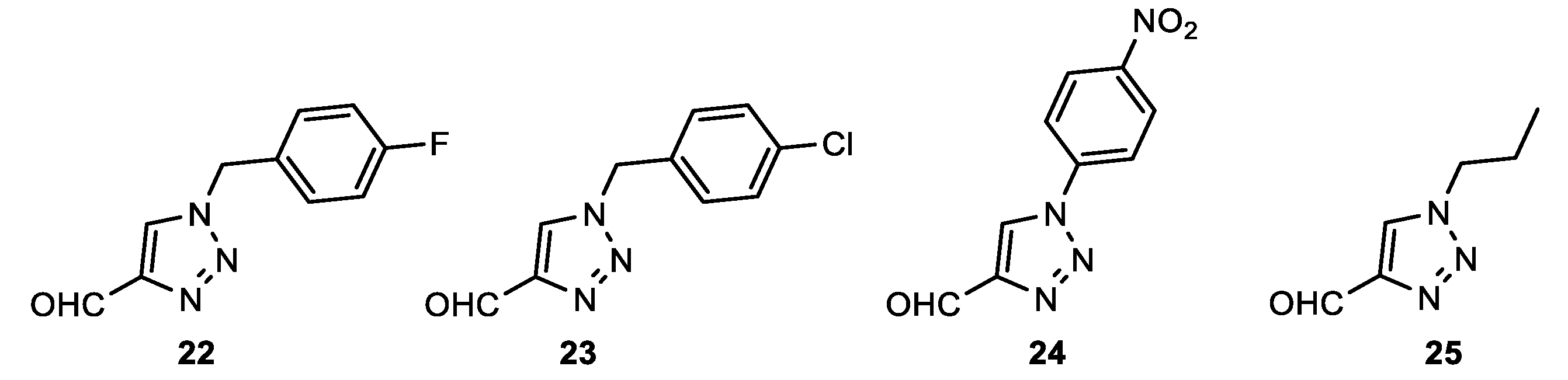

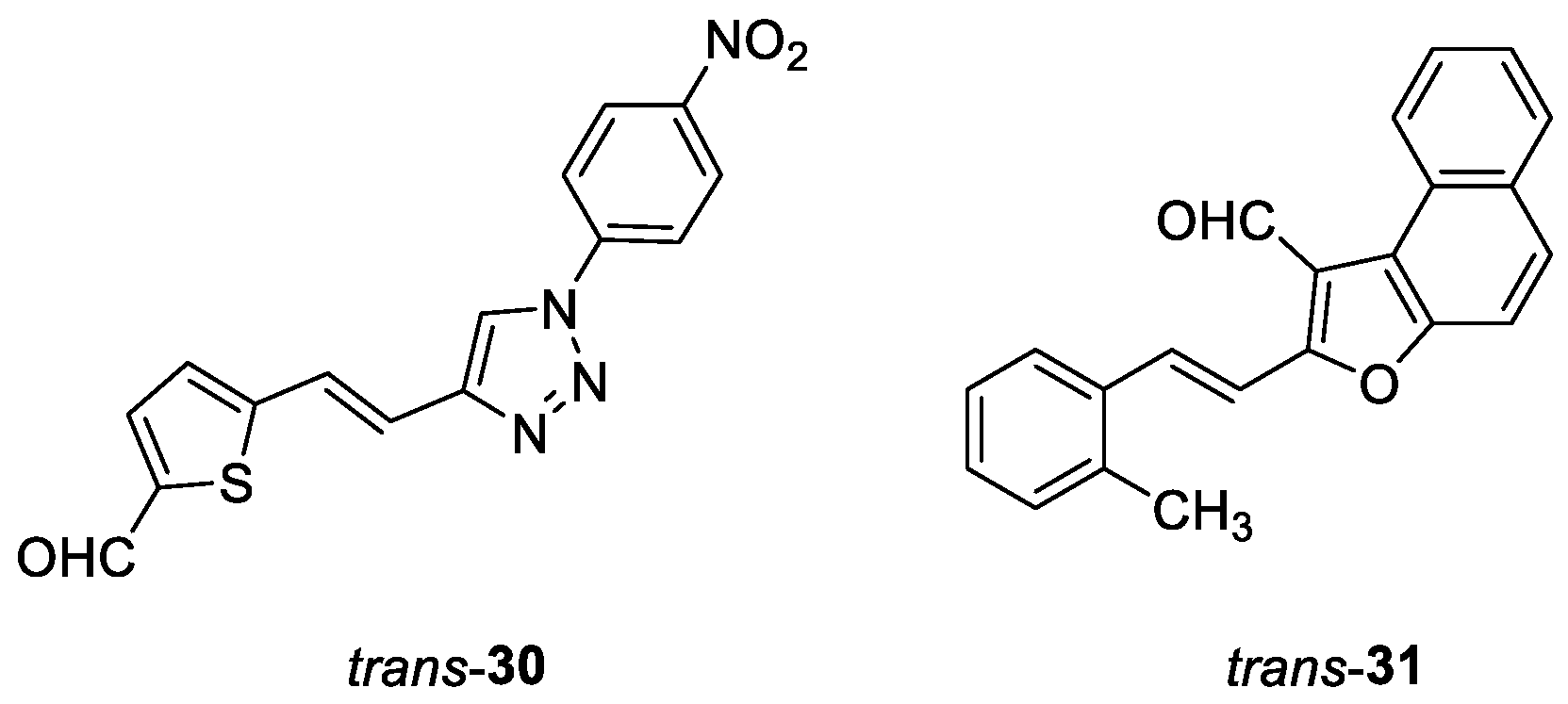

Corresponding amines (1.2 eq) were added to a solution of triazole nitro aldehyde

24 [

18,

19] (1 eq) in dry dioxane and purged with argon, Ar. Reaction mixtures were stirred at 130 °C. After overnight, reaction mixtures were cooled to room temperature and evaporated till dryness to obtain crude products

22, 23 and

25. Crude products were purified by a column chromatography using E/EtOAc solvent system.

1-(4-fluorobenzyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazole-4-carbaldehyde (22): 128 mg, 78% isolated yield; yellow oil; Rf (DCM/EtOAc (2%)) = 0.53; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 10.13 (s, 1H), 7.99 (s, 1H), 7.33 – 7.30 (m, 2H), 7.13 – 7.08 (m, 2H), 5.57 (s, 2H).

1-(4-chlorobenzyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazole-4-carbaldehyde (23): 85 mg, 68% isolated yield; yellow oil; Rf (DCM/EtOAc (2%)) = 0.50; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 10.13 (s, 1H), 8.01 (s, 1H), 7.41 – 7.38 (m, 4H), 5.57 (s, 2H).

1-(4-nitrophenyl)-1

H-1,2,3-triazole-4-carbaldehyde (

24) [

12,

70]: 720 mg, 72% isolated yield; yellow powder;

Rf (DCM/EtOAc (2%)) = 0.52;

1H NMR (CDCl

3, 600 MHz)

δ/ppm: 10.20 (s, 1H), 8.66 (s, 1H), 8.49 (d,

J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 8.04 (d,

J = 9.0 Hz, 2H).

1-propyl-1H-1,2,3-triazole-4-carbaldehyde (25): 100 mg, 40% isolated yield; yellow oil; Rf (DCM/EtOAc (2%)) = 0.55; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 10.14 (s, 1H), 8.15 (s, 1H), 4.95 – 4.88 (m, 1H), 1.65 (s, 3H), 1.64 (s, 3H).

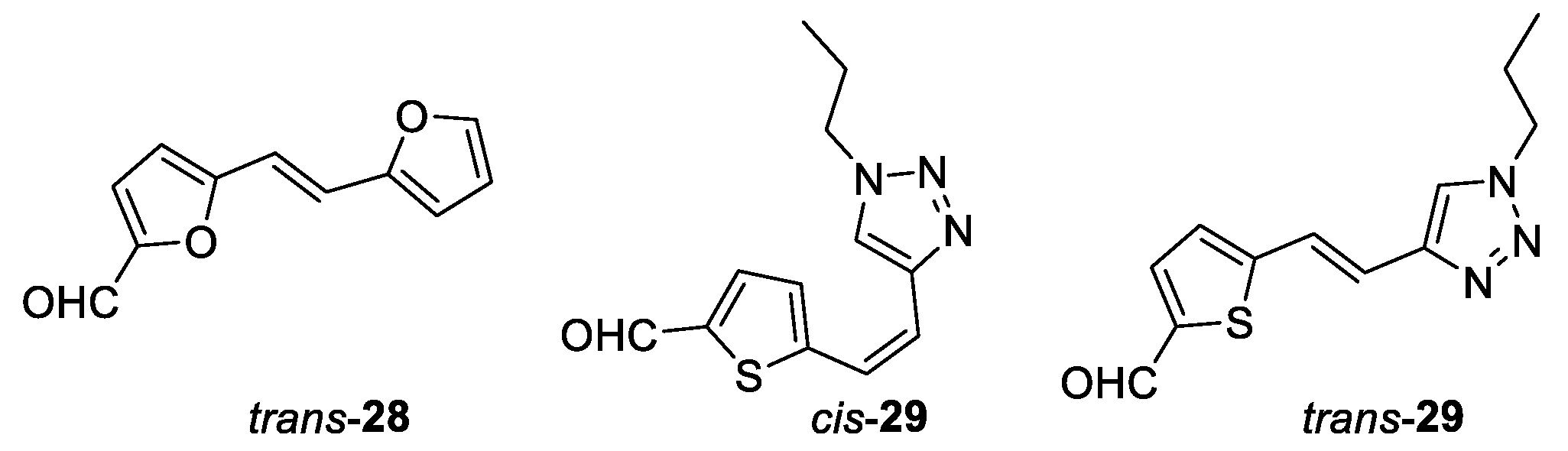

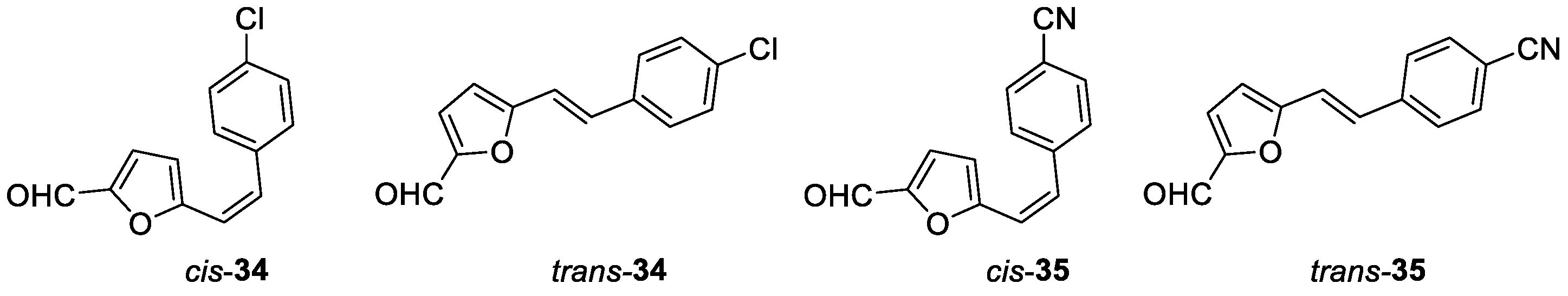

The obtained heterostilbenes 45–63 were subjected to Vilsmeier formylation reaction. The selected heterostilbenes, as mixtures of isomers, were dissolved in 2 mL of DMF and stirred for 10 min at 10 °C. This temperature was achieved using a water bath with a few ice cubes and monitored with a thermometer. The weighed amount of POCl3 was slowly added dropwise. After 30 min, the water bath was removed, and the reaction mixture was allowed to stir. Upon completion of the reaction, the reaction mixture was neutralized using 10% NaOH solution. When neutralization was achieved, extraction was carried using E and water. The combined organic layer was washed with water and dried over MgSO4, filtered, and the solvent was evaporated. The dry reaction mixture was purified by column chromatography on silica gel using a PE/E or PE/DCM variable polarity eluent. In the first fractions, the unreacted substrates were isolated (as cis-isomers), while in the last fractions, the desired formyl derivatives 26–44 were obtained (mainly as trans-isomers). They were further used in the preparation of oximes 4–21.

(E)-2-(2-(5-formylthiophen-2-yl)vinyl)phenyl acetate (trans-26'): 128 mg, 78% isolated yield; yellow oil; Rf (DCM) = 0.36; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 9.86 (s, 1H), 7.65 – 7.64 (m, 2H), 7.33 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.27 – 7.24 (m, 1H), 7.21 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H), 7.17 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H), 7.14 (d, J = 3.9 Hz, 1H), 7.11 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 2.39 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 182.7, 169.2, 152.1, 148.5, 141.9, 137.2, 129.6, 128.5, 127.2, 126.4, 125.9, 123.0, 122.9, 99.9, 20.9.

(E)-5-(2-hydroxystyryl)thiophene-2-carbaldehyde (trans-26): 60 mg, 50% isolated yield; yellow powder; Rf (E) = 0.26; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 9.85 (s, 1H), 7.67 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (dd, J = 7.7, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 7.47 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 7.31 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 7.19 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.16 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 1H), 6.96 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 6.82 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 5.38 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 182.8, 153.7, 153.5, 141.3, 137.5, 129.8, 128.0, 127.7, 126.4, 123.3, 121.8, 121.2, 116.2.

(Z)-2-(2-(5-formylthiophen-2-yl)vinyl)benzonitrile (cis-27): 10 mg, 20% isolated yield; yellow oil; Rf (DCM) = 0.40; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 9.79 (s, 1H), 7.75 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.61 (t, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.57 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H), 7.51 – 7.47 (m, 2H), 7.05 (d, J = 4.1 Hz, 1H), 6.96 (d, J = 11.9 Hz, 1H), 6.87 (d, J = 11.9 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 182.9, 147.6, 143.5, 140.1, 135.9, 133.5, 130.3, 129.6, 128.8, 126.4, 117.4, 112.3.

(E)-5-(2-(furan-2-yl)vinyl)furan-2-carbaldehyde (trans-28): 74 mg, 60% isolated yield; red oil; Rf (PE/E (20%)) = 0.85; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ/ppm: 9.57 (s, 1H), 7.44 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.26 – 7.23 (m, 1H), 7.16 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 6.82 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 6.49 – 6.45 (m, 3H).

(Z)-5-(2-(1-propyl-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)vinyl)thiophene-2-carbaldehyde (cis-29): 25 mg, 25% isolated yield; yellow oil; Rf (PE/E (9%)) = 0.25; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 9.89 (s, 1H), 7.69 (d, J = 4.1 Hz, 1H), 7.63 (s, 1H), 7.51 (d, J = 4.1 Hz, 1H), 6.72 (d, J = 12.4 Hz, 1H), 6.69 (d, J = 12.4 Hz, 1H), 4.36 – 4.33 (m, 2H), 2.00 – 1.93 (m, 2H), 1.00 – 0.96 (m, 3H).

(E)-5-(2-(1-propyl-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)vinyl)thiophene-2-carbaldehyde (trans-29): 25 mg, 25% isolated yield; yellow oil; Rf (PE/E (90%)) = 0.23; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 9.87 (s, 1H), 7.67 (d, J = 4.1 Hz, 1H), 7.57 (s, 1H), 7.51 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H), 7.17 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 7.11 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H), 4.36 – 4.33 (m, 2H), 2.00 – 1.93 (m, 2H), 1.00 – 0.96 (m, 3H).

(E)-5-(2-(1-(4-nitrophenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)vinyl)thiophene-2-carbaldehyde (trans-30): 12 mg, 10% isolated yield; yellow oil; Rf (DCM) = 0.15; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 9.82 (s, 1H), 8.45 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 2H), 8.11 (s, 1H), 8.00 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 2H), 7.69 (d, J = 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.68 (d, J = 14.1 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H), 7.68 (d, J = 14.1 Hz, 1H).

(E)-2-(2-methylstyryl)naphtho[2,1-b]furan-1-carbaldehyde (trans-31): 75 mg, 75% isolated yield; yellow powder; Rf (PE/E (50%)) = 0.75; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 10.67 (s, 1H), 9.30 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.97 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H), 7.95 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 7.86 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 1H), 7.75 – 7.63 (m, 4H), 7.58 – 7.54 (m, 2H), 7.31 – 7.29 (m, 2H), 2.55 (s, 3H).

(E)-5-(4-methylstyryl)furan-2-carbaldehyde (trans-32): 693 m, 76% isolated yield; white powder; Rf (PE/E (2%)) = 0.15; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 9.58 (s, 1H), 7.40 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.36 (d, J = 16.5 Hz, 1H), 7.24 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 1H), 7.18 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 6.88 (d, J = 16.5 Hz, 1H), 6.50 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 1H), 2.36 (s, 3H).

(Z)-5-(4-methylstyryl)furan-2-carbaldehyde (cis-33): 17 mg, 4% isolated yield; colorless oil; Rf (PE/E (1%)) = 0.27; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 9.54 (s, 1H), 7.42 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.13 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 1H), 6.89 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 6.73 (d, J = 12.4 Hz, 1H), 6.41 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 1H), 6.36 (d, J = 12.4 Hz, 1H), 3.84 (s, 3H) ; 13C NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 177.4, 159.7, 157.8, 151.1, 134.3, 130.2, 128.7, 115.9, 113.9, 111.6, 55.3.

(E)-5-(4-methoxystyryl)furan-2-carbaldehyde (trans-33): 90 mg, 17% isolated yield; white powder; Rf (PE/E (1%)) = 0.22; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 9.56 (s, 1H), 7.44 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.34 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H), 7.24 (d, J = 4.0 Hz, 1H), 6.90 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 2H), 6.78 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H), 6.47 (d, J = 4.0 Hz, 1H), 3.82 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 176.7, 160.3, 159.3, 151.4, 133.1, 133.2, 128.4, 114.3, 112.9, 109.9, 55.4.

(E)-2-(4-methoxystyryl)furan-3-carbaldehyde (trans-33'): 60 mg, 26% isolated yield; white powder; Rf (PE/E (1%)) = 0.15; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 9.91 (s, 1H), 7.57 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 7.49 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 2H), 7.47 (d, J = 16.9 Hz, 1H), 7.09 ( d, J = 16.9 Hz, 1H), 6.91 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 6.83 (d, J = 1.5 HZ, 1H), 3.84 (s, 3H).

(Z)-5-(4-chlorostyryl)furan-2-carbaldehyde (cis-34): 128 mg, 21% isolated yield; yellow oil; Rf (PE/E (1%)) = 0.23; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 9.54 (s, 1H), 7.38 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.34 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.13 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H), 6.73 (d, J = 13.1 Hz, 1H), 6.47 (d, J = 13.1 Hz, 1H), 6.34 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 177.3, 156.9, 151.4, 134.7, 134.2, 132.9, 129.9, 128.7, 117.9, 112.3.

(E)-5-(4-chlorostyryl)furan-2-carbaldehyde (trans-34): 62.7 mg, 11% isolated yield; white powder; Rf (PE/E (1%)) = 0.18; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 9.57 (s, 1H), 7.41 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 7.32 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 7.31 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H), 7.24 (d, J = 3.5 Hz, 1H), 6.88 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H), 6.53 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 176.9, 158.2, 151.8, 134.6, 134.3, 131.8, 129.1, 128.1, 115.5, 111.0.

(Z)-4-(2-(5-formylfuran-2-yl)vinyl)benzonitrile (cis-35): 21 mg, 3% isolated yield; white oil; Rf (PE/E (20%)) = 0.33; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 9.54 (s, 1H), 7.67 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 7.55 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.16 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 1H), 6.76 (d, J = 12.3 Hz, 1H), 6.56 (d, J = 12.3 Hz, 1H), 6.37 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 1H).

(E)-4-(2-(5-formylfuran-2-yl)vinyl)benzonitrile (trans-35): 62 mg, 9% isolated yield; white powder; Rf (PE/E (20%)) = 0.23; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 9.64 (s, 1H), 7.67 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 7.57 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.37 (d, J = 16.5 Hz, 1H), 7.28 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 1H), 7.03 (d, J = 16.5 Hz, 1H), 6.64 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 1H).

(Z)-5-(4-(dimethylamino)styryl)furan-2-carbaldehyde (cis-36): 10 mg; 2% isolated yield; yellow oil; Rf (PE/E (5%)) = 0.16; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 9.55 (s, 1H), 7.45 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.17 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 1H), 6.70 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 6.69 (d, J = 12.4 Hz, 1H), 6.52 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H), 6.23 (d, J = 12.4 Hz, 1H), 3.01 (s, 6H).

(E)-5-(4-(dimethylamino)styryl)furan-2-carbaldehyde (trans-36): 5 mg; 5% isolated yield; yellow powder; Rf (PE/E (5%)) = 0.15; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 9.53 (s, 1H), 7.41 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.33 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 7.24 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H), 7.20 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 6.70 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 6.43 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 1H), 3.01 (s, 6H).

(Z)-3-(4-methylstyryl)furan-2-carbaldehyde (cis-37): 151 mg, 43% isolated yield; orange oil; Rf (PE/E (5%)) = 0.40; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 9.81 (s, 1H), 7.43 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.18 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 7.11 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 6.85 (d, J = 12.4 Hz, 1H), 6.85 (d, J = 12.4 Hz, 1H), 6.27 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H), 2.35 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 178.2, 148.5, 146.8, 138.0, 135.7, 133.6, 129.1, 128.7, 127.0, 117.4, 112.9, 21.3.

(E)-3-(4-methylstyryl)furan-2-carbaldehyde (trans-37): 103 mg, 51% isolated yield; yellow powder; Rf (PE/E (5%)) = 0.26; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 9.91 (s, 1H), 7.58 (d, J = 1.3 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 7.45 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.19 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.11 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 6.85 (d, J = 1.3 Hz, 1H), 2.37 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 178.5, 147.7, 147.5, 139.0, 135.3, 133.4, 129.5, 129.1, 128.7, 127.1, 109.8, 21.3.

(Z)-3-(4-methoxystyryl)furan-2-carbaldehyde (cis-38): 90 mg, 30% isolated yield; yellow oil; Rf (PE/DCM (30%)) = 0.30; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ/ppm: 9.81 (s, 1H), 7.44 (s, 1H), 7.26 – 7.21 (m, 2H), 6.85 – 6.76 (m, 4H), 6.31 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 3.82 (s, 3H).

(E)-3-(4-methoxystyryl)furan-2-carbaldehyde (trans-38): 135 mg, 56% isolated yield; yellow powder; Rf (PE/DCM (30%)) = 0.25; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ/ppm: 9.90 (s, 1H), 7.57 – 7.44 (m, 4H), 7.09 (d, J = 15.0 Hz, 1H), 6.93 – 6.83 (m, 3H), 3.84 (s, 3H).

(Z)-3-(4-chlorostyryl)furan-2-carbaldehyde (cis-39): 187 mg, 67% isolated yield; orange oil; Rf (PE/E (10%)) = 0.30; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 9.83 (s, 1H), 7.44 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.29 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.22 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 6.94 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1H), 7.82 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1H), 6.22 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H).

(E)-3-(4-chlorostyryl)furan-2-carbaldehyde (trans-39): 58 mg, 23% isolated yield; yellow powder; Rf (PE/E (5%)) = 0.20; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 9.92 (s, 1H), 7.62 (d, J = 16.3 Hz, 1H), 7.59 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.48 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.35 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.08 (d, J = 16.3 Hz, 1H), 6.85 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 178.5, 147.6, 146.9, 134.2, 133.8, 130.1, 129.0, 128.7, 128.2, 112.8, 109.9.

(Z)-4-(2-(2-formylfuran-3-yl)vinyl)benzonitrile (cis-40): 175 mg, 68% isolated yield; yellow oil; Rf (PE/E (20%)) = 0.55; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 9.85 (s, 1H), 7.61 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.47 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.40 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.07 (d, J = 12.3 Hz, 1H), 6.85 (d, J = 12.3 Hz, 1H), 6.15 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 178.7, 148.9, 147.0, 133.2, 132.6, 132.3, 129.5, 127.4, 121.1, 112.6, 111.6, 109.9.

(E)-4-(2-(2-formylfuran-3-yl)vinyl)benzonitrile (trans-40): 119 mg, 45% isolated yield; yellow powder; Rf (PE/E (20%)) = 0.46; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 9.94 (s, 1H), 7.76 (d, J = 16.5 Hz, 1H), 7.66 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.63 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.62 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 7.12 (d, J = 16.5 Hz, 1H), 6.87 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 179.4, 148.4, 147.6, 140.6, 132.9, 132.6, 127.4, 120.6, 118.8, 111.7, 109.9.

(Z)-3-(4-methylstyryl)thiophene-2-carbaldehyde (cis-41): 110 mg, 27% isolated yield; Rf (PE/E (10%)) = 0.57; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ/ppm: 9.99 (s, 1H), 7.56 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 1H), 7.06 (t, J = 9.4 Hz, 4H), 6.92 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 6.84 (d, J = 12.1 Hz, 1H), 6.78 (d, J = 12.1 Hz, 1H), 2.31 (s, 3H).

(E)-3-(4-methylstyryl)thiophene-2-carbaldehyde (trans-41): 186 mg, 64% isolated yield; white powder; Rf (PE/E (10%)) = 0.42; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ/ppm: 10.21 (s, 1H), 7.65 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 7.63 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 7.43 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 3H), 7.20 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.14 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 2.37 (s, 3H).

(Z)-3-(4-methoxystyryl)thiophene-2-carbaldehyde (cis-42): 45 mg, 20% isolated yield; white oil; Rf (PE/DCM (60%)) = 0.55; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ/ppm: 9.99 (s, 1H), 7.57 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 7.12 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 2H), 6.94 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H), 6.82 – 6.71 (m, 4H), 3.78 (s, 3H).

(E)-3-(4-methoxystyryl)thiophene-2-carbaldehyde (trans-42): 130 mg, 52% isolated yield; white powder; Rf (PE/DCM (60%)) = 0.50; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ/ppm: 10.21 (s, 1H), 7.66 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 7.59 – 7.42 (m, 7H), 3.85 (s, 3H).

(Z)-3-(4-chlorostyryl)thiophene-2-carbaldehyde (cis-43): 98 mg, 41% isolated yield; white oil; Rf (PE/E (10%)) = 0.19; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ/ppm: 9.99 (s, 1H), 7.58 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 1H), 7.22 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.10 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 6.90 – 6.87 (m, 3H), 6.86 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 6.80 (d, J = 12.2 Hz, 1H).

(E)-3-(4-chlorostyryl)thiophene-2-carbaldehyde (trans-43): 96 mg, 40% isolated yield; white powder; Rf (PE/E (10%)) = 0.15; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ/ppm: 10.19 (s, 1H), 7.85 (d, J = 16.5 Hz, 1H), 7.72 – 7.60 (m, 5H), 7.48 (d, J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 7.15 (d, J = 16.5 Hz, 1H).

(E)-4-(2-(2-formylthiophen-3-yl)vinyl)benzonitrile (trans-44): 31 mg, 86% isolated yield; white powder; Rf (PE/E (10%)) = 0.24; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ/ppm: 10.19 (s, 1H), 7.86 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 7.71 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 7.68 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.63 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.48 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 7.16 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 181.9, 149.7, 140.8, 134.5, 139.5, 133.0, 132.6, 132.3, 129.5, 127.3, 123.1, 118.7.

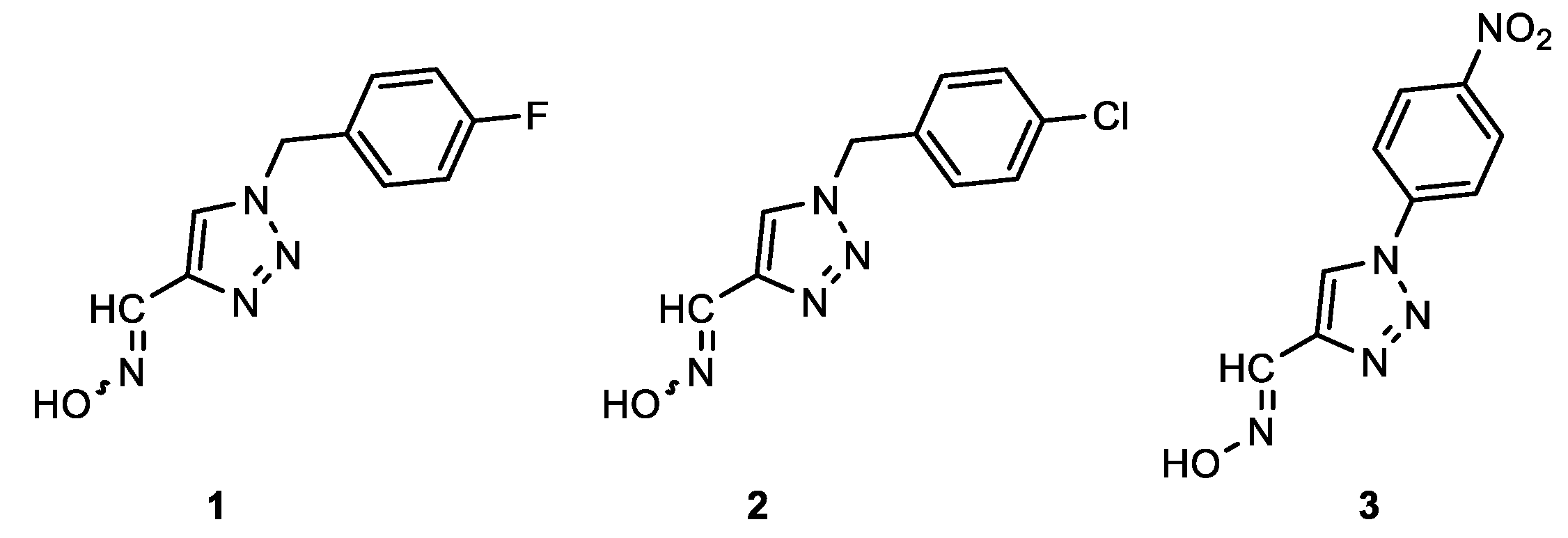

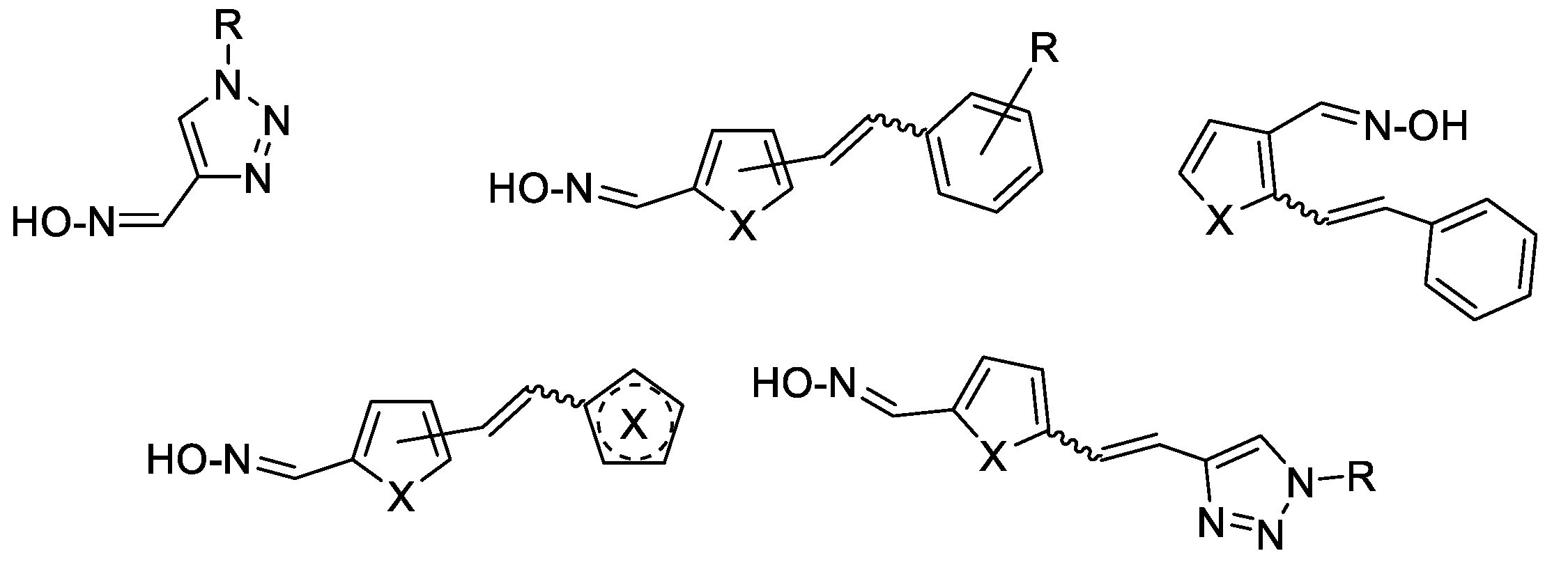

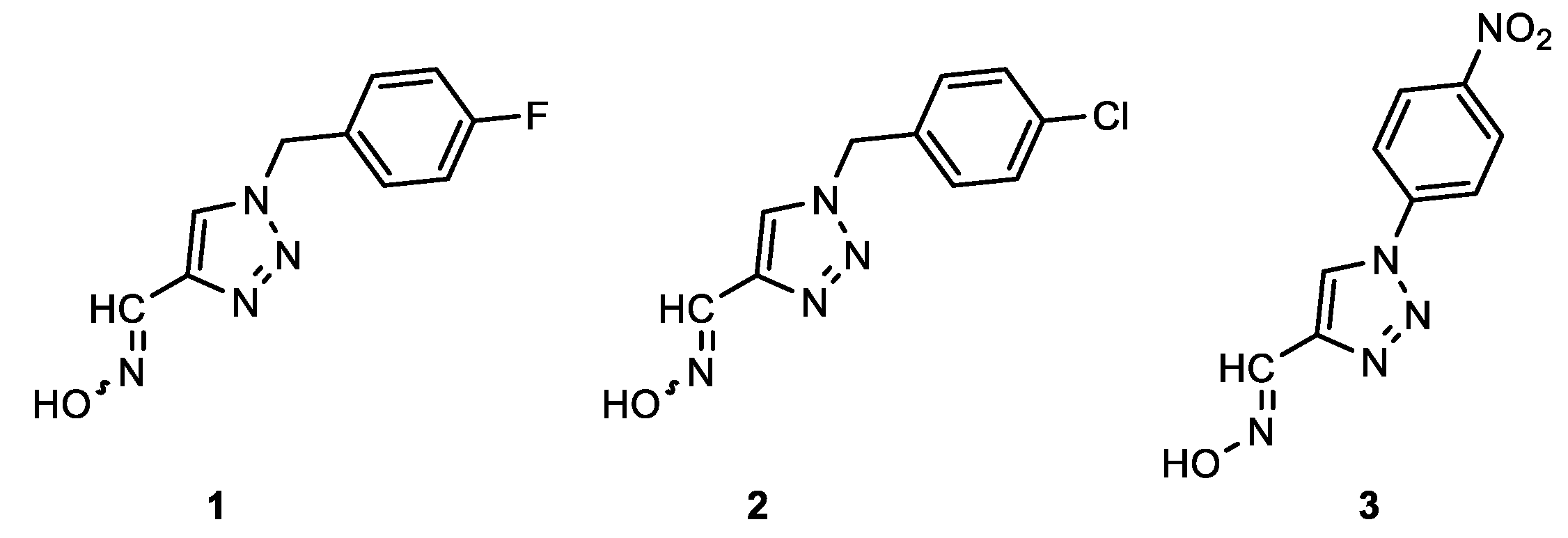

The obtained aldehydes

23–

25 were converted into oximes

1–

3 while aldehydes

26–

44 produced the corresponding oximes

4–

21 according to the literature [

20]. Crystals of NH

2OH × HCl were dissolved in a prepared mixture of 10 mL of EtOH and 3 mL of distilled water. After a homogeneous solution was obtained, the corresponding prepared heterostilbene aldehydes

26–

44 were added. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 h. When the reaction was completed, the solvent was evaporated on a rotavapor under reduced pressure. The reaction mixture was purified by repeated column chromatography on silica gel using PE/DCM and DCM/methanol variable polarity eluents. The targeted oximes

1–

21 were isolated and the spectroscopic data and yields of their pure isomers are given below.

1-(4-fluorobenzyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazole-4-carbaldehyde oxime (1): 30 mg, 16% isolated yield; yellow oil; Rf (DCM/MeOH (30%)) = 0.22; 1H NMR (CD3OD, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 8.48 (s, 1H), 8.44 (s, 1H), 8.12 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 2H), 6.87 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 5.68 (s, 2H). In the mixture, the ratio of the two isomers is approximately 1:1.

1-(4-chlorobenzyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazole-4-carbaldehyde oxime (2): 30 mg, 8% isolated yield; yellow oil; Rf (DCM/MeOH (30%)) = 0.21; 1H NMR (CD3OD, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 8.11 (s, 1H), 8.10 (s, 1H), 6.86 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 6.60 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 4.81 (s, 2H). In the mixture, the ratio of the syn- and anti-isomers is approximately 2:1.

1-(4-nitrophenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazole-4-carbaldehyde oxime (3): 70 mg, 50% isolated yield; yellow oil; Rf (DCM/MeOH (30%)) = 0.25; 1H NMR (CD3OD, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 9.29 (s, 1H), 8.48 (d, J = 9.4 Hz, 2H), 8.24 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 2H), 7.75 (s, 1H). The majority syn-isomer is formed. MS (ESI) m/z (%, fragment): 234 (5); 121 (100); HRMS (m/z) for C9H7N5O3: [M + H]+calcd = 233.0548, and [M + H]+measured = 233.0549.

(E)-5-((E)-2-hydroxystyryl)thiophene-2-carbaldehyde oxime (trans,syn-4): 18 mg, 25%; Rf (DCM/MeOH (10%)) = 0.52; 1H NMR (CDCl3, CD3OD, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 8.20 (s, 1H), 7.46 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.29 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 2H), 7.25 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H), 7.11 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 7.05 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 1H), 6.97 (d, J = 4.2 Hz, 1H), 6.87 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 6.81 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 153.9, 149.1, 145.6, 133.9, 132.4, 130.2, 128.9, 127.3, 125.9, 125.1, 122.2, 120.7, 116.0.

(Z)-5-((E)-2-hydroxystyryl)thiophene-2-carbaldehyde oxime (trans,anti-4): 41 mg, 52% isolated yield; white powder; m.p. = 173 – 175˚C; Rf (DCM/MeOH (10%)) = 0.45; 1H NMR (CDCl3, CD3OD, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.61 (s, 1H), 7.47 (dd, J = 7.6, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.38 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 7.30 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 7.24 (t, J = 3.7 Hz, 1H), 7.13 – 7.10 (m, 1H), 7.04 (d, J = 4.4 Hz, 1H), 6.88 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 6.81 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 158.6, 152.9, 144.8, 135.9, 133.1, 132.8, 130.8, 129.3, 128.5, 127.8, 125.5, 123.8, 119.6.

MS (ESI) m/z (%, fragment): 242 (100); 200 (30); HRMS (m/z) for C13H9NO2S: [M + H]+calcd = 243.0354, and [M + H]+measured = 243.0355.

2-((Z)-2-(5-((E)-(hydroxyimino)methyl)thiophen-2-yl)vinyl)benzonitrile (cis,syn-5): 38 mg, 33% isolated yield; white powder; m.p. = 171 – 173˚C; Rf (DCM/MeOH (5%)) = 0.65; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 8.12 (s, 1H), 7.72 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.60 – 7.55 (m, 2H), 7.43 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 7.09 (s, 1H), 6.99 (d, J = 4.1 Hz, 1H), 6.91 (d, J = 4.1 Hz, 1H), 6.88 (d, J = 12.1 Hz, 1H), 6.69 (d, J = 12.1 Hz, 1H); MS (ESI) m/z (%, fragment): 255 (100); HRMS (m/z) for C14H10N2OS: [M + H]+calcd = 254.0513, and [M + H]+measured = 254.0514.

(E)-5-((E)-2-(furan-2-yl)vinyl)furan-2-carbaldehyde oxime (trans,syn-6): 15 mg, 23%; Rf (DCM/MeOH (10%)) = 0.56; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.97 (s, 1H), 7.45 (s, 1H), 6.97 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 6.77 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 6.63 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H), 6.42 – 6.41 (m, 1H), 6.38 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 1H), 6.37 (d, J = 3.2 Hz, 1H).

(Z)-5-((E)-2-(furan-2-yl)vinyl)furan-2-carbaldehyde oxime (trans,anti-6): 34 mg, 48% isolated yield; white powder; m.p. = 150 – 153˚C; Rf (DCM/MeOH (10%)) = 0.53; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.51 (s, 1H), 7.41 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.31 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 1H), 6.93 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 6.79 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 6.46 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H), 6.44 – 6.43 (m, 1H), 6.40 (d, J = 3.4 Hz, 1H).

MS (ESI) m/z (%, fragment): 204 (100); HRMS (m/z) for C11H10NO3: [M + H]+calcd = 203.0582, and [M + H]+measured = 203.0586.

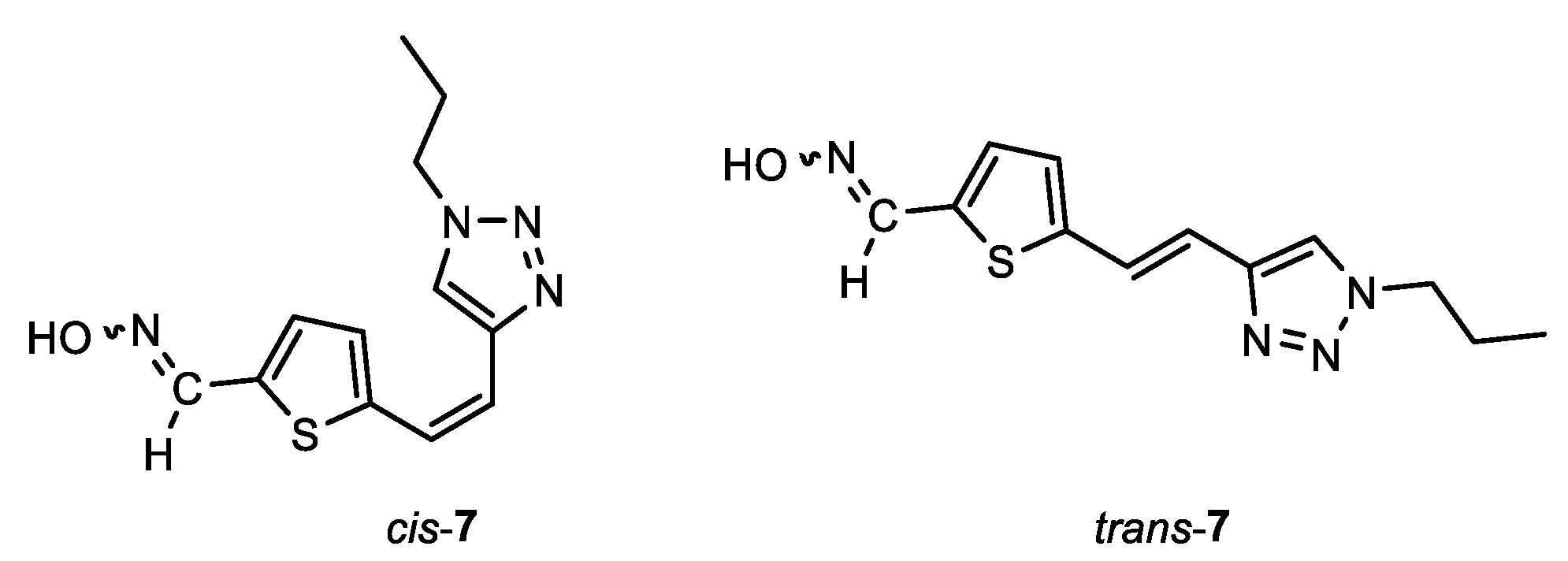

(E)-5-((Z)-2-(1-propyl-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)vinyl)thiophene-2-carbaldehyde oxime (cis,syn-7): 17 mg; 9%; Rf (DCM/MeOH (5%)) = 0.22; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 8.21 (s, 1H), 7.53 (s, 1H), 7.08 – 7.06 (m, 2H), 6.69 (d, J = 12.4 Hz, 1H), 6.63 (d, J = 12.4 Hz, 1H), 4.35 – 4.29 (m, 2H), 1.98 – 1.91 (m, 2H), 0.99 – 0.95 (m, 3H).

(Z)-5-((Z)-2-(1-propyl-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)vinyl)thiophene-2-carbaldehyde oxime (cis,anti-7): 20 mg; 11%; Rf (DCM/MeOH (5%)) = 0.22; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.64 (s, 1H), 7.63 (s, 1H), 7.10 (d, J = 3.2 Hz, 1H), 7.08 – 7.06 (m, 1H), 6.65 (d, J = 12.1 Hz, 1H), 6.58 (d, J = 12.1 Hz, 1H), 4.35 – 4.29 (m, 2H), 1.98 – 1.91 (m, 2H), 0.99 – 0.95 (m, 3H).

(E)-5-((E)-2-(1-propyl-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)vinyl)thiophene-2-carbaldehyde oxime (trans,syn-7): 22 mg; 12%; Rf (DCM/MeOH (5%)) = 0.21; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 8.22 (s, 1H), 7.53 (s, 1H), 7.47 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H), 7.31 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 1H), 7.29 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 1H), 7.01 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H), 4.35 – 4.29 (m, 2H), 1.98 – 1.91 (m, 2H), 0.99 – 0.95 (m, 3H).

(Z)-5-((E)-2-(1-propyl-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)vinyl)thiophene-2-carbaldehyde oxime (trans,anti-7): 19 mg; 10%; Rf (DCM/MeOH (5%)) = 0.21; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.65 (s, 1H), 7.61 (s, 1H), 7.42 (d, J = 15.4 Hz, 1H), 7.08 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 1H), 7.08 (d, J = 4.2 Hz, 1H), 6.92 (d, J = 15.4 Hz, 1H), 4.35 – 4.29 (m, 2H), 1.98 – 1.91 (m, 2H), 0.99 – 0.95 (m, 3H).

MS (ESI) m/z (%, fragment): 263 (100); HRMS (m/z) for C12H15N4OS: [M + H]+calcd = 262.0888, and [M + H]+measured = 262.0890.

5-(2-(1-(4-nitrophenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)vinyl)thiophene-2-carbaldehyde oxime (trans-8): 6 mg, 2%; Rf (DCM/MeOH (5%)) = 0.12; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 8.82 (s, 1H), 8.79 (s, 1H), 8.48 (d, J = 9.8 Hz, 2H), 8.19 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 2H), 7.67 (d, J = 16.6 Hz, 1H), 7.65 (d, J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 7.63 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 7.61 (d, J = 16.6 Hz, 1H); MS (ESI) m/z (%, fragment): 342 (30); 121 (100); HRMS (m/z) for C15H11N5O3S: [M + H]+calcd = 341.0583, and [M + H]+measured = 341.0574.

(E)-2-((E)-2-methylstyryl)naphtho[2,1-b]furan-1-carbaldehyde oxime (trans,syn-9): 38 mg, 40% isolated yield; yellow powder; m.p. = 148 – 152˚C; Rf (DCM) = 0.35; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.60 (s, 1H), 7.50 – 7.45 (m, 1H), 7.40 (d, J = 16.6 Hz, 1H), 7.30 (d, J = 16.6 Hz, 1H) 7.25 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 1H), 7.11 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.04 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 1H), 6.87 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 6.83 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 3.22 (s, 3H); MS (ESI) m/z (%, fragment): 328 (100); 121 (30); HRMS (m/z) for C22H17NO2: [M + H]+calcd = 327.1259, and [M + H]+measured = 327.1254.

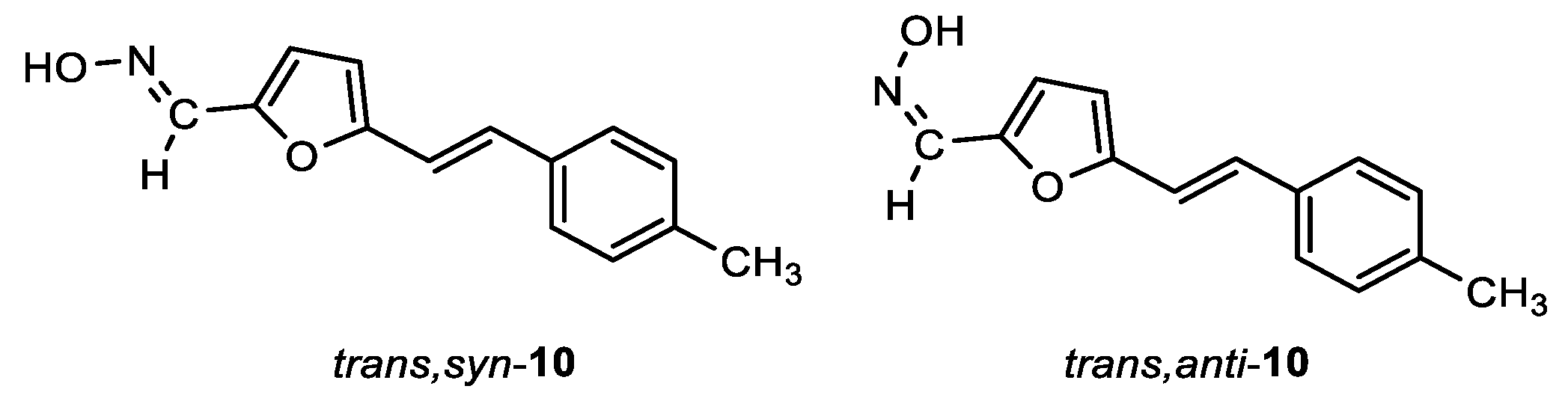

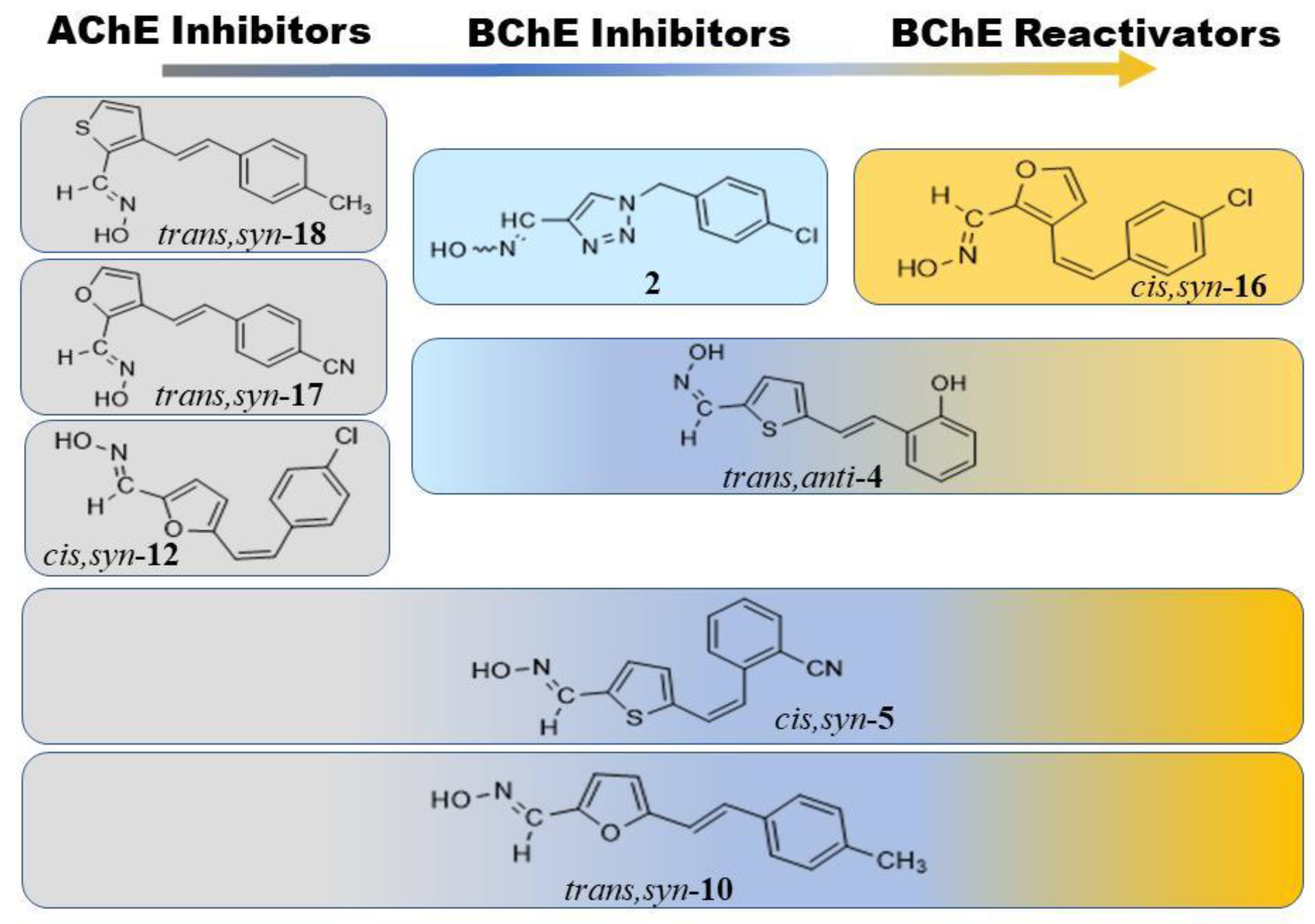

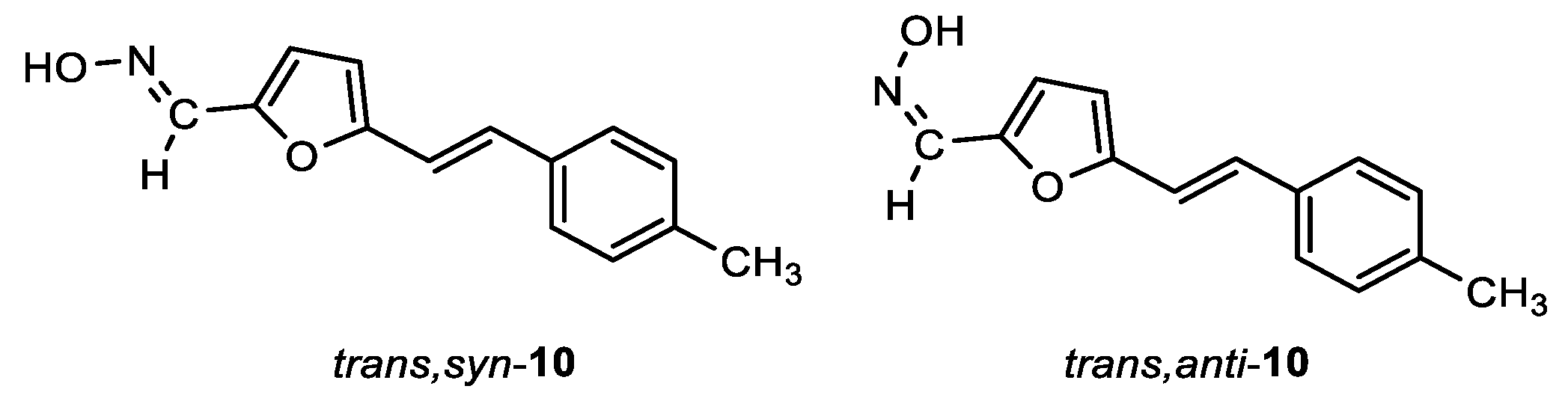

(E)-5-((E)-4-methylstyryl)furan-2-carbaldehyde oxime (trans,syn-10): 203 mg, 28% isolated yield; white powder; m.p. = 153 – 154˚C; Rf (DCM/MeOH (1%)) = 0.35; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.99 (s, 1H), 7.59 (s, 1H), 7.37 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.17 – 7.15 (m, 3H), 6.83 (d, J = 16.3 Hz, 1H), 6.68 (d, J = 3.5 Hz, 1H), 6.38 (d, J = 3.5 Hz, 1H), 2.35 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 155.3, 146.2, 140.2, 138.1, 133.8, 129.5, 129.5, 126.5, 115.4, 114.7, 109.9, 21.3; MS (ESI) m/z (%, fragment): 228 (100); HRMS (m/z) for C14H13NO2: [M + H]+calcd = 227.0946, and [M + H]+measured = 227.0947.

(Z)-5-((E)-4-methylstyryl)furan-2-carbaldehyde oxime (trans,anti-10): 168 mg, 23% isolated yield; yellow oil; Rf (DCM/MeOH (1%)) = 0.26; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.53 (s, 1H), 7.38 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 7.31 (d, J = 3.1 Hz, 1H), 7.16 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 7.15 (d, J = 16.5 Hz, 1H), 6.84 (d, J = 16.5 Hz, 1H), 6.46 (d, J = 3.3 Hz, 1H), 2.36 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 153.9, 144.0, 138.2, 137.4, 133.7, 129.7, 126.5, 120.3, 114.9, 110.8, 21.3.

(E)-5-((E)-4-methoxystyryl)furan-2-carbaldehyde oxime (trans,syn-11): 7 mg, 6% isolated yield; yellow powder; m.p. = 160 – 162˚C; Rf (DCM/E (1%)) = 0.26; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 8.20 (s, 1H), 7.861 (s, 1H), 7.43 – 7.41 (m, 3H), 7.03 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 6.91 – 6.84 (m, 3H), 6.71 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H), 3.82 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 159.1, 143.9, 142.4, 139.2, 130.3, 129.1, 127.3, 126.2, 114.4, 113.7, 108.4, 54.8.

(E)-5-((Z)-4-chlorostyryl)furan-2-carbaldehyde oxime (cis,syn-12): 39 mg, 42% isolated yield; white powder; m.p. = 178 – 180˚C; Rf (DCM/MeOH (1%)) = 0.73; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 8.0 (s, 1H), 7.91 (s, 1H), 7.40 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.31 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 6.56 (d, J = 3.4 Hz, 1H), 6.50 (d, J = 12.6 Hz, 1H), 6.38 (d, J = 12.6 Hz, 1H), 6.28 (d, J = 3.5 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 153.4, 146.0, 140.1, 135.3, 133.5, 130.0, 128.9, 128.5, 118.0, 114.2, 111.9; MS (ESI) m/z (%, fragment): 248 (100); HRMS (m/z) for C13H10ClNO2: [M + H]+calcd = 247.0400, and [M + H]+measured = 247.0401.

(Z)-5-((Z)-4-chlorostyryl)furan-2-carbaldehyde oxime (cis,anti-12): 15 mg, 14%; Rf (DCM/MeOH (1%)) = 0.50; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 8.63 (s, 1H), 7.39 (s, 1H), 7.38 – 7.28 (m, 4H), 7.23 (d, J = 3.2 Hz, 1H), 6.54 (d, J = 12.8 Hz, 1H), 6.38 (d, J = 3.4 Hz, 1H), 6.37 (d, J = 12.8 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 152.2, 143.8, 137.0, 135.3, 133.5, 130.1 129.3, 128.3, 119.7, 117.8, 113.0.

(E)-5-((E)-4-chlorostyryl)furan-2-carbaldehyde oxime (trans,syn-12): 19 mg, 20%; Rf (DCM/MeOH (1%)) = 0.44; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.98 (s, 1H), 7.49 (s, 1H), 7.39 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.31 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.13 (d, J = 16.3 Hz, 1H), 6.84 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 6.65 (d, J = 3.5 Hz, 1H), 6.42 (d, J = 3.5 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 154.7, 146.6, 140.2, 135.1, 133.7, 128.9, 128.0, 127.6, 116.1, 115.3, 110.7.

(Z)-5-((E)-4-chlorostyryl)furan-2-carbaldehyde oxime (trans,anti-12): 5 mg, 5%; Rf (DCM/MeOH (1%)) = 0.34; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 8.10 (s, 1H), 7.99 (s, 1H), 7.38 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.30 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 7.14 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H), 6.83 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H), 6.65 (d, J = 3.1 Hz, 1H), 6.42 (d, J = 3.4 Hz, 1H).

(E)-5-((E)-4-(dimethylamino)styryl)furan-2-carbaldehyde oxime (trans,syn-13): 10 mg, 5%; Rf (DCM/MeOH (5%)) = 0.65; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.96 (s, 1H), 7.38 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.37 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.09 (d, J = 16.5 Hz, 1H), 6.60 (d, J = 16.5 Hz, 1H), 6.62 (d, J = 3.5 Hz, 1H), 6.31 (d, J = 3.5 Hz, 1H), 2.99 (s, 6H).

(Z)-5-((E)-4-(dimethylamino)styryl)furan-2-carbaldehyde oxime (trans,anti-13): 11 mg, 7%; Rf (DCM/MeOH (5%)) = 0.59; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.51 (s, 1H), 7.38 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.37 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 7.31 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 1H), 7.13 (d, J = 16.4 Hz, 1H), 7.09 (d, J = 16.4 Hz, 1H), 6.39 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H), 2.99 (s, 6H).

Data for the isomers written from the 1H NMR of the mixture of isomers. MS (ESI) m/z (%, fragment): 239 (100); HRMS (m/z) for C14H10N2O2: [M + H]+calcd = 238.0742, and [M + H]+measured = 238.0741.

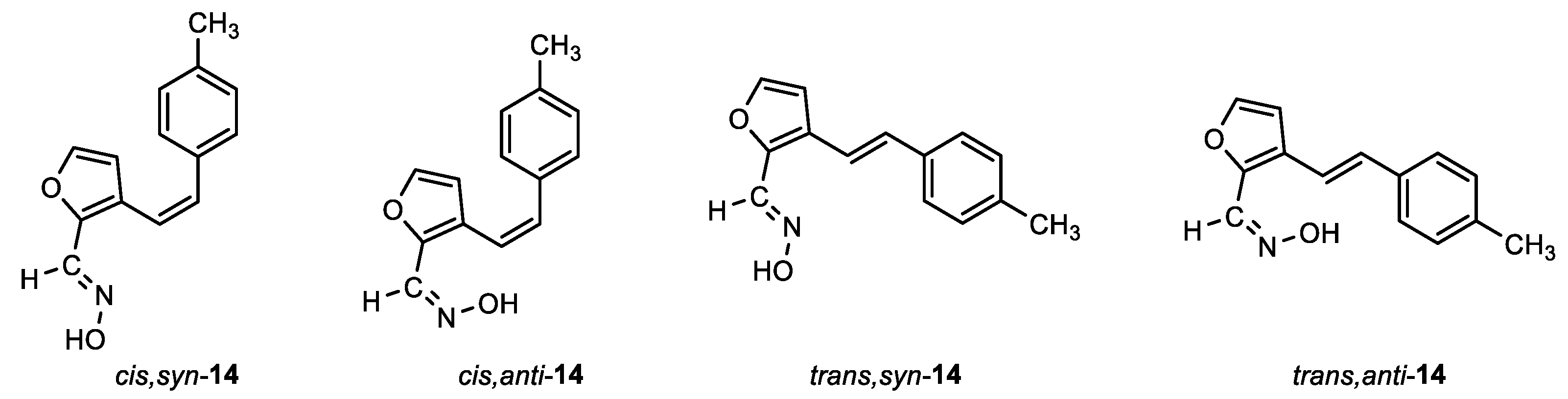

(E)-3-((Z)-4-methylstyryl)furan-2-carbaldehyde oxime (cis,syn-14): 113 mg, 38% isolated yield; white powder; m.p. = 145 – 148˚C; Rf (PE/E (15%)) = 0.27; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 9.08 (s, 1H), 8.11 (s, 1H), 7.27 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.19 (d, J = 8.0, 2H), 7.09 (d, J = 8.0, 2H), 6.65 (d, J = 12.2 Hz, 1H), 6.44 (d, J = 12.2 Hz, 1H), 6.17 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 2.33 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 144.1, 143.6, 139.4, 137.5, 134.0, 132.4, 129.0, 128.8, 124.3, 117.9, 111.9, 21.3.

(Z)-3-((Z)-4-methylstyryl)furan-2-carbaldehyde oxime (cis,anti-14): 2 mg, 1%; Rf (PE/E (15%)) = 0.22; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.43 (d, J = 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.26 (s, 1H), 7.18 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 7.09 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 6.70 (d, J = 11.8 Hz, 1H), 6.45 (d, J = 11.8 Hz, 1H), 6.22 (d, J = 1.7 Hz, 1H), 2.34 (s, 3H).

(E)-3-((E)-4-methylstyryl)furan-2-carbaldehyde oxime (trans,syn-14): 70 mg, 34% isolated yield; white powder; m.p. = 146 – 147˚C; Rf (PE/E (10%)) = 0.17; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 8.23 (s, 1H), 7.45 (s, 1H), 7.43 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 7.38 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.17 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.13 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 6.89 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 6.72 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 2.36 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 144.4, 143.2, 140.1, 138.0, 134.1, 131.2, 129.5, 126.5, 126.4, 116.1, 109.0, 21.3.

(Z)-3-((E)-4-methylstyryl)furan-2-carbaldehyde oxime (trans,anti-14): 5 mg, 2%; Rf (PE/E (10%)) = 0.10; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.49 (d, J = 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.44 (s, 1H), 7.32 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.19 (s, 1H), 7.10 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.05 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H), 6.84 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H), 6.67 (d, J = 1.7 Hz, 1H), 2.29 (s, 3H).

(E)-3-((Z)-4-methoxystyryl)furan-2-carbaldehyde oxime (cis,syn-15): 26 mg, 15%; Rf (PE/DCM (60%)) = 0.25; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 8.10 (s, 1H), 7.55 (s, 1H), 7.30 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.24 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 6.83 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 2H), 6.63 (d, J = 12.3 Hz, 1H), 6.42 (d, J = 12.3 Hz, 1H), 6.21 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 3.81 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 159.1, 143.9, 143.6, 140.1, 132.0, 130.2, 129.4, 124.8, 117.2, 113.7, 111.9, 55.2.

(E)-3-((E)-4-methoxystyryl)furan-2-carbaldehyde oxime (trans,syn-15): 36 mg, 15%; Rf (PE/DCM (60%)) = 0.15; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 8.23 (s, 1H), 7.84 (s, 1H), 7.42 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 3H), 7.03 (d, J = 16.6 Hz, 1H), 6.89 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 6.87 (d, J = 16.6 Hz, 1H), 6.71 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 3.83 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 159.6, 144.4, 142.9, 139.9, 130.8, 129.7, 127.8, 126.7, 114.9, 114.2, 108.9, 55.3; MS (ESI) m/z (%, fragment): 244 (100); HRMS (m/z) for C14H13NO3: [M + H]+calcd = 243.0895, and [M + H]+measured = 243.0901.

(Z)-3-((E)-4-methoxystyryl)furan-2-carbaldehyde oxime (trans,anti-15): 70 mg, 26% isolated yield; white powder; m.p. = 158 – 164˚C; Rf (PE/DCM (60%)) = 0.13; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 8.23 (s, 1H), 7.93 (s, 1H), 7.42 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 3H), 7.03 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H), 6.89 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 2H), 6.87 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H), 6.71 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 3.83 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 159.6, 144.4, 142.9, 139.9, 130.8, 129.7, 127.8, 126.7, 114.9, 114.2, 108.9, 55.3.

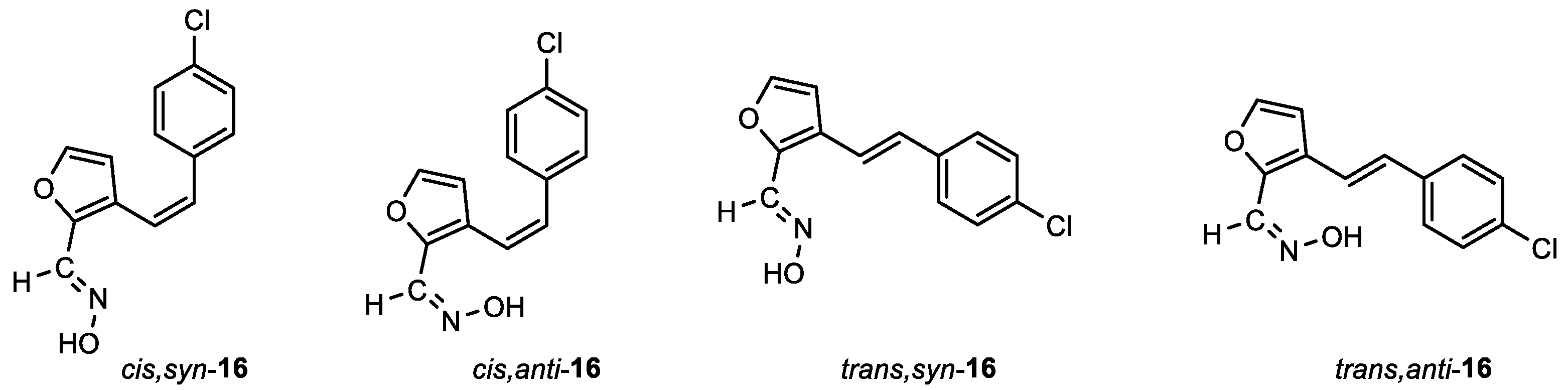

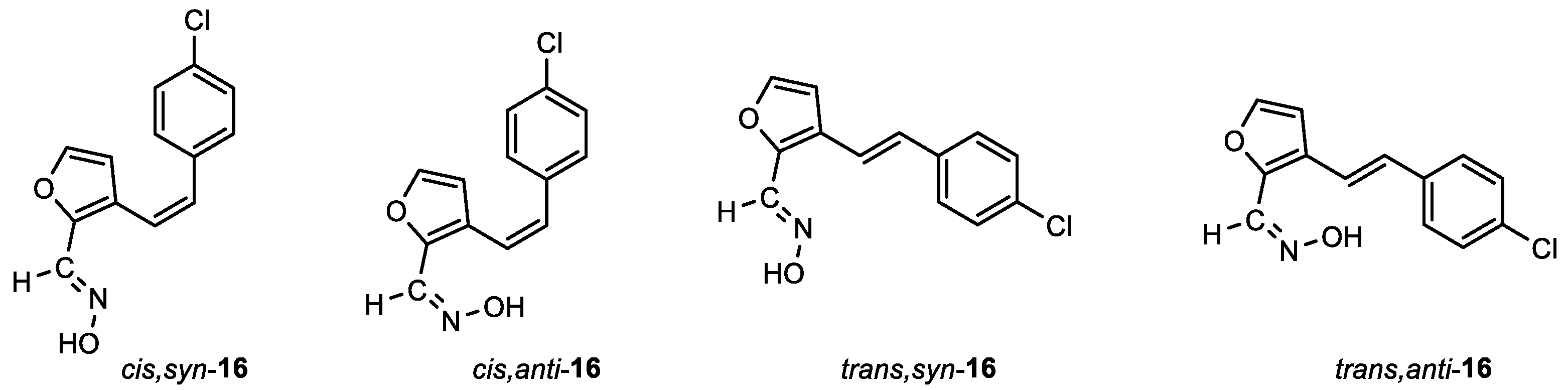

(E)-3-((Z)-4-chlorostyryl)furan-2-carbaldehyde oxime (cis,syn-16): 114 mg, 24% isolated yield; white powder; m.p. = 189 – 191˚C; Rf (PE/E (15%)) = 0.47; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 8.10 (s, 1H), 7.99 (s, 1H), 7.28 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.23 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 6.63 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1H), 6.55 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1H), 6.12 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 144.4, 143.7, 139.8, 135.5, 133.4, 130.9, 130.2, 128.5, 124.0, 119.4, 111.7; MS (ESI) m/z (%, fragment): 248 (100); HRMS (m/z) for C13H10ClNO2: [M + H]+calcd = 247.0400, and [M + H]+measured = 247.0405.

(Z)-3-((Z)-4-chlorostyryl)furan-2-carbaldehyde oxime (cis,anti-16): 5 mg, 1%; Rf (PE/E (15%)) = 0.28; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.44 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.35 (s, 1H), 7.26 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.21 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 6.66 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 2H), 6.53 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 2H), 6.16 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H).

(E)-3-((E)-4-chlorostyryl)furan-2-carbaldehyde oxime (trans,syn-16): 48 mg, 20% isolated yield; white powder; m.p. = 181 – 183˚C; Rf (PE/E (15%)) = 0.40; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 8.22 (s, 1H), 7.48 (s, 1H), 7.48 (s, 1H), 7.44 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.41 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.32 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.19 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H), 6.86 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H), 6.72 (d, J = 1.7 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 144.4, 143.7, 140.2, 135.4, 133.5, 129.8, 128.9, 127.6, 125.8, 118.0, 108.9.

(Z)-3-((E)-4-chlorostyryl)furan-2-carbaldehyde oxime (trans,anti-16): 12 mg, 3%; Rf (PE/E (15%)) = 0.25; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.61 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (s, 1H), 7.42 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.33 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.17 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H), 6.88 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H), 6.74 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 144.9, 144.5, 140.1, 135.4, 134.3, 130.3, 129.8, 129.0, 127.9, 117.9, 108.7.

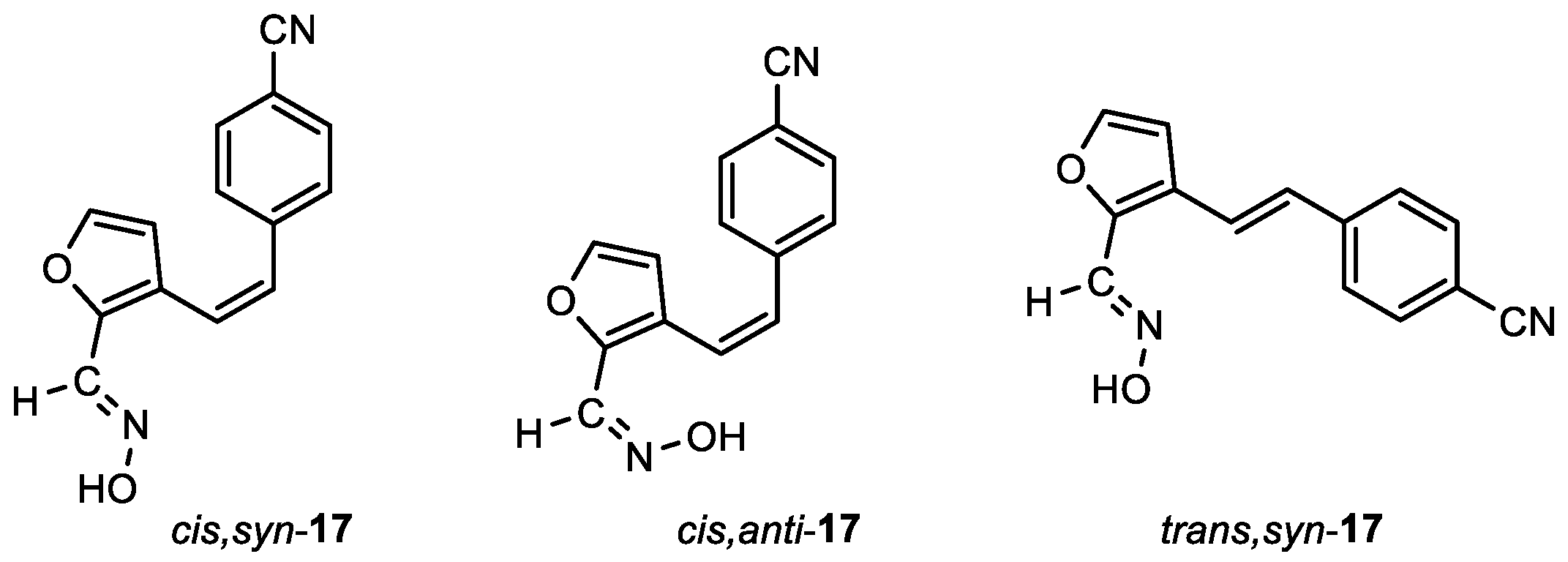

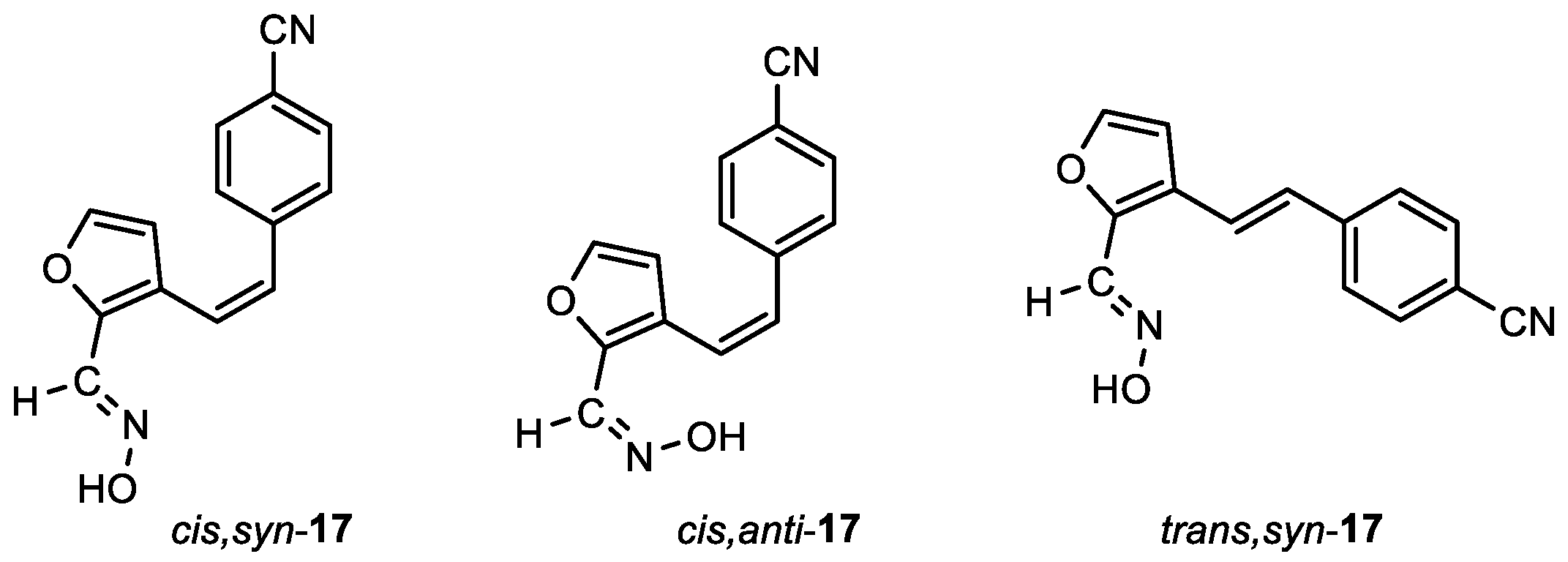

4-((Z)-2-(2-((E)-(hydroxyimino)methyl)furan-3-yl)vinyl)benzonitrile (cis,syn-17): 141 mg, 43% isolated yield; white powder; m.p. = 198 – 201˚C; Rf (PE/E (20%)) = 0.56; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 8.10 (s, 1H), 7.59 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.41 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.32 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 6.71 (d, J =12.1 Hz, 1H), 6.64 (d, J =12.1 Hz, 1H), 6.07 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 143.9, 140.2, 132.5, 132.2, 130.0, 129.9, 129.5, 126.8, 123.1, 121.7, 117.7, 111.6; MS (ESI) m/z (%, fragment): 239 (100); HRMS (m/z) for C14H10N2O2: [M + H]+calcd = 247.0400, and [M + H]+measured = 247.0405.

4-((Z)-2-(2-((Z)-(hydroxyimino)methyl)furan-3-yl)vinyl)benzonitrile (cis,anti-17): 17 mg, 6%; Rf (PE/E (20%)) = 0.34; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.58 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.45 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 7.39 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.33 (s, 1H), 6.69 (d, J = 12.3 Hz, 1H), 6.67 (d, J = 12.3 Hz, 1H), 6.11 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 144.5, 141.4, 134.2, 132.1, 130.7, 129.5, 125.5, 121.9, 118.7, 111.5, 111.1, 103.0.

4-((E)-2-(2-((E)-(hydroxyimino)methyl)furan-3-yl)vinyl)benzonitrile (trans,syn-17): 47 mg, 16% isolated yield; white powder; m.p. = 193 – 195˚C; Rf (PE/E (30%)) = 0.53; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 8.23 (s, 1H), 7.76 (s, 1H), 7.63 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.56 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.47 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.37 (d, J = 16.3 Hz, 1H), 6.90 (d, J = 16.3 Hz, 1H), 6.74 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 144.6, 144.5, 141.4, 140.3, 132.6, 132.5, 126.9, 125.0, 121.2, 118.9, 110.8, 108.9.

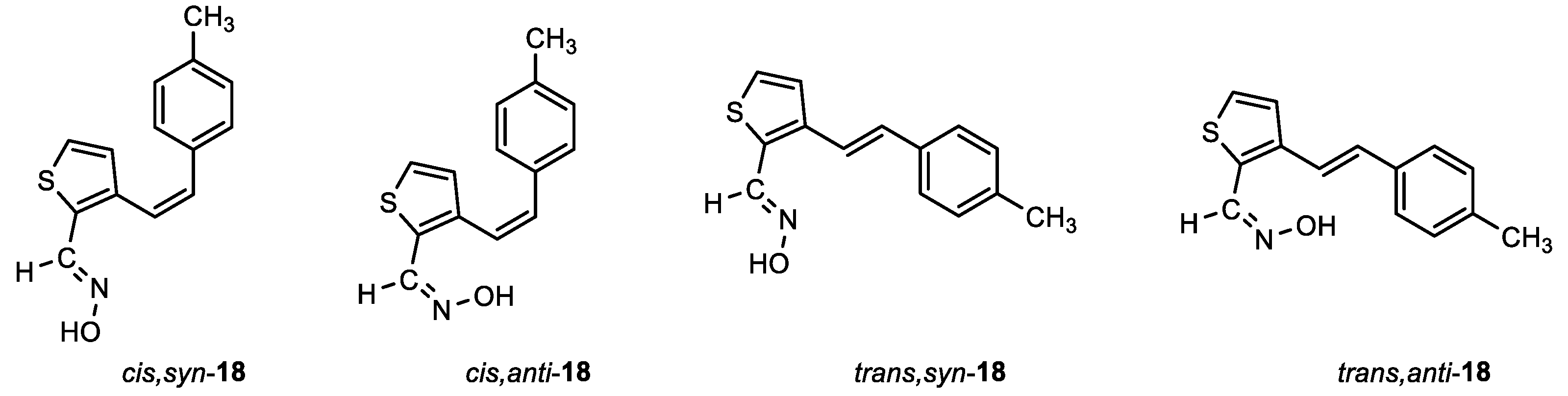

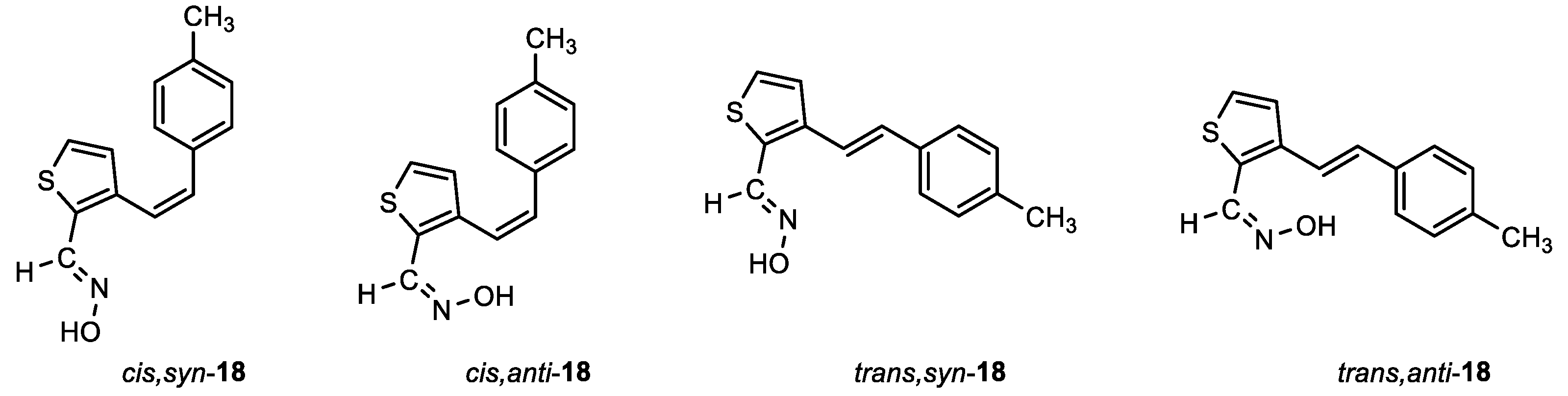

(E)-3-((Z)-4-methylstyryl)thiophene-2-carbaldehyde oxime (cis,syn-18): 72 mg, 28% isolated yield; white powder; m.p. = 158 – 160˚C; Rf (PE/E (10%)) = 0.53; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ/ppm: 8.32 (s, 1H), 7.15 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 2H), 7.09 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.04 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 6.79 (d, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H), 6.68 (d, J = 12.1 Hz, 1H), 6.50 (d, J = 12.1 Hz, 1H), 2.31 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 144.5, 140.0, 137.6, 132.8, 130.4, 129.0, 128.9, 128.8, 126.4, 121.6, 121.1, 21.2; MS (ESI) m/z (%, fragment): 244 (100); HRMS (m/z) for C14H13NOS: [M + H]+calcd = 243.0718, and [M + H]+measured = 243.0717.

(Z)-3-((Z)-4-methylstyryl)thiophene-2-carbaldehyde oxime (cis,anti-18): 58 mg, 23% isolated yield; white powder; m.p. = 155 – 156˚C; Rf (PE/E (10%)) = 0.34; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.81 (s, 1H), 7.42 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 7.05 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 7.01 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 6.87 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 6.73 (d, J = 12.1 Hz, 1H), 6.58 (d, J = 12.1 Hz, 1H), 2.29 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 141.5, 140.1, 137.6, 133.5, 133.5, 130.4, 129.0, 128.9, 127.6, 125.8, 121.5, 99.9, 21.2.

(E)-3-((E)-4-methylstyryl)thiophene-2-carbaldehyde oxime (trans,syn-18): 87 mg, 34% isolated yield; white powder; m.p. = 151 – 153˚C; Rf (PE/E (10%)) = 0.40; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ/ppm: 8.55 (s, 1H), 7.39 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.34 (s, 1H), 7.30 (k, 2H), 7.18 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 3H), 6.98 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H), 2.37 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 144.0, 140.6, 138.2, 134.1, 131.4, 129.8, 129.5, 127.2, 126.5, 125.6, 118.9, 21.3.

(Z)-3-((E)-4-methylstyryl)thiophene-2-carbaldehyde oxime (trans,anti-18): 43 mg, 13%; Rf (PE/E (10%)) = 0.23; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ/ppm: 8.02 (s, 1H), 7.52 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 7.42 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.37 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 7.29 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.19 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 7.04 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H), 2.37 (s, 3H).

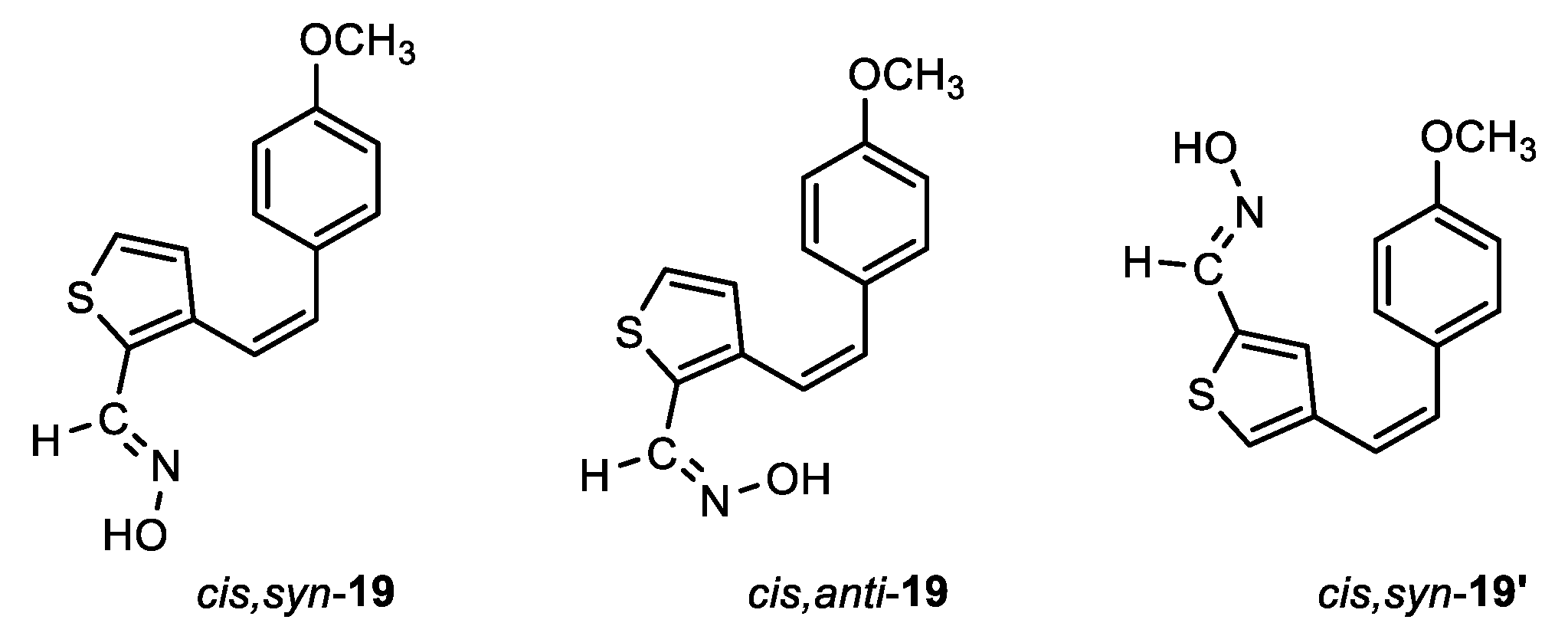

(E)-3-((Z)-4-methoxystyryl)thiophene-2-carbaldehyde oxime (cis,syn-19): 7 mg, 6%; Rf (DCM) = 0.55; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 8.32 (s, 1H), 7.69 (s, 1H), 7.16 (d, J = 4.3 Hz, 1H), 7.13 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 6.81 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 6.80 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 6.64 (d, J = 11.8 Hz, 1H), 6.45 (d, J = 11.8 Hz, 1H), 3.78 (s, 3H).

(Z)-3-((Z)-4-methoxystyryl)thiophene-2-carbaldehyde oxime (cis,anti-19): 16 mg, 13%; Rf (DCM) = 0.45; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.81 (s, 1H), 7.44 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 7.08 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 6.89 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 6.74 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 6.69 (d, J = 11.9 Hz, 1H), 6.52 (d, J = 11.9 Hz, 1H), 3.77 (s, 3H).

(E)-4-((Z)-4-methoxystyryl)thiophene-2-carbaldehyde oxime (cis,syn-19'): 100 mg, 78% isolated yield; white powder; m.p. = 159 – 160 ˚C; Rf (DCM) = 0.60; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 600 MHz) δ/ppm: 9.26 (s, 1H), 8.11 (s, 1H), 7.30 (d, J = 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 6.82 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 2H), 6.61 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1H), 6.39 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1H), 6.19 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 3.79 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz) δ/ppm: 159.2, 144.7, 143.1, 138.7, 131.4, 129.8, 123.7, 117.3, 113.7, 111.4, 54.3.

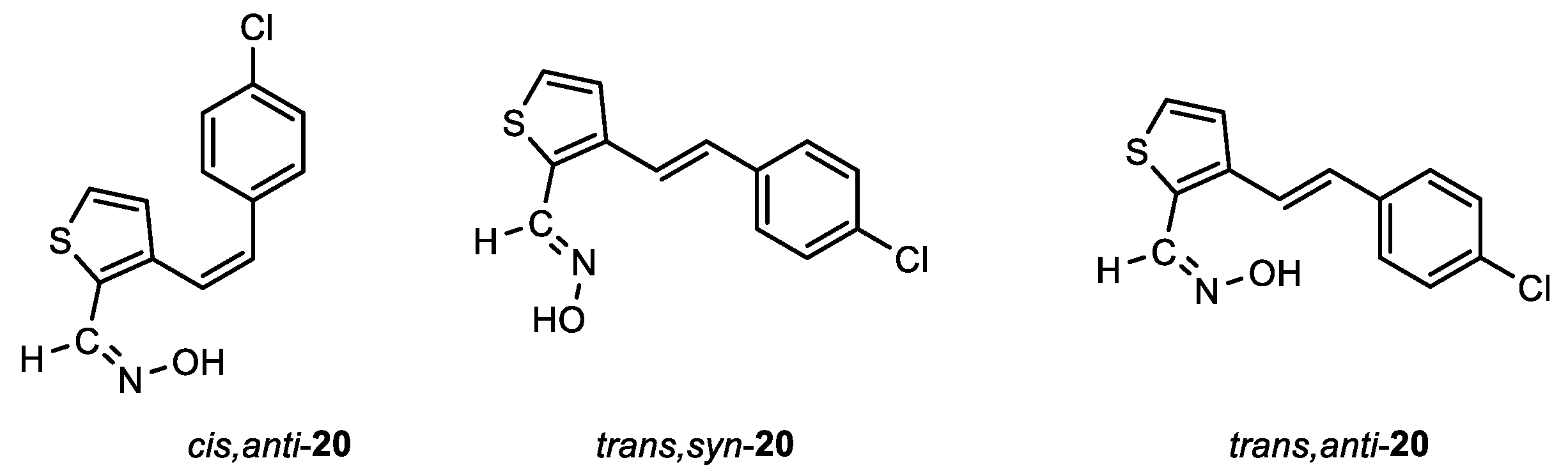

(Z)-3-((Z)-4-chlorostyryl)thiophene-2-carbaldehyde oxime (cis,anti-20): 8 mg, 29%; Rf (PE/E (20%)) = 0.35; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ/ppm: 8.29 (s, 1H), 7.21 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.17 (d, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H), 7.12 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 6.74 (d, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H), 6.65 (d, J = 12.1 Hz, 1H), 6.58 (d, J = 12.1 Hz, 1H).

(E)-3-((E)-4-chlorostyryl)thiophene-2-carbaldehyde oxime (trans,syn-20): 6 mg, 21%; Rf (PE/E (20%)) = 0.62; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ/ppm: 8.54 (s, 1H), 7.42 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.33 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.30 (s, 2H) 7.22 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H), 6.95 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 143.8, 139.9, 135.4, 133.7, 130.0, 129.0, 127.7, 127.4, 125.5, 124.3, 120.5.

(Z)-3-((E)-4-chlorostyryl)thiophene-2-carbaldehyde oxime (trans,anti-20): 8 mg, 29%; Rf (PE/E (20%)) = 0.27; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.93 (s, 1H), 7.53 (s, 2H), 7.42 – 7.38 (m, 2H), 7.35 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H), 7.30 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.24 – 7.17 (m, 2H), 6.96 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H).

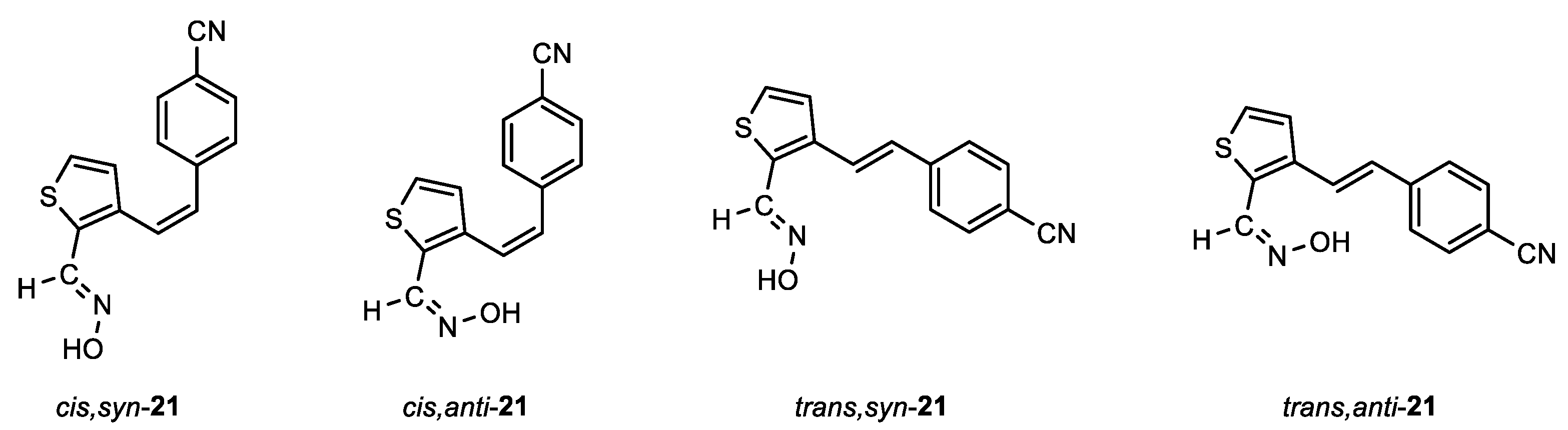

4-((Z)-2-(2-((E)-(hydroxyimino)methyl)thiophen-3-yl)vinyl)benzonitrile (cis,syn-21): 62 mg, 34% isolated yield; yellow powder; m.p. = 169 – 171˚C; Rf (PE/E (25%)) = 0.58; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ/ppm: 8.25 (s, 1H), 7.53 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.34 (s, 1H), 7.29 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.20 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 6.74 – 6.66 (m, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 138.6, 136.0, 133.0, 126.9, 126.7, 125.5, 124.2, 123.0, 121.9, 119.9, 113.5, 105.8; MS (ESI) m/z (%, fragment): 255 (100); HRMS (m/z) for C14H10N2OS: [M + H]+calcd = 254.0514, and [M + H]+measured = 254.0512.

4-((Z)-2-(2-((Z)-(hydroxyimino)methyl)thiophen-3-yl)vinyl)benzonitrile (cis,anti-21): 52 mg, 27% isolated yield; yellow powder; m.p. = 170 – 171˚C; Rf (PE/E (25%)) = 0.24; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ/ppm: 7.75 (s, 1H), 7.50 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.47 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 7.24 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 6.83 (d, J = 12.2 Hz, 1H), 6.79 (d, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H), 6.75 (d, J = 12.2 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 143.8, 141.1, 139.8, 138.3, 132.1, 130.8, 129.5, 128.3, 127.1, 125.7, 118.7, 111.0.

4-((E)-2-(2-((E)-(hydroxyimino)methyl)thiophen-3-yl)vinyl)benzonitrile (trans,syn-21): 11 mg, 5%; Rf (PE/E (25%)) = 0.47; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ/ppm: 8.53 (s, 1H), 7.65 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.57 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.36 – 7.35 (m, 4H), 6.98 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 150 MHz) δ/ppm: 148.7, 143.6, 141.4, 132.6, 129.2, 127.6, 126.9, 125.5, 123.4, 121.2, 118.9, 111.1.

4-((E)-2-(2-((Z)-(hydroxyimino)methyl)thiophen-3-yl)vinyl)benzonitrile (trans,anti-21): 15 mg, 7%; Rf (PE/E (25%)) = 0.22; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ/ppm: 8.05 (s, 1H), 7.72 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.69 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.64 (s, 1H), 7.60 (s, 1H), 7.49 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H), 7.46 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 7.14 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H).