Submitted:

12 May 2024

Posted:

13 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Physiological Mechanisms

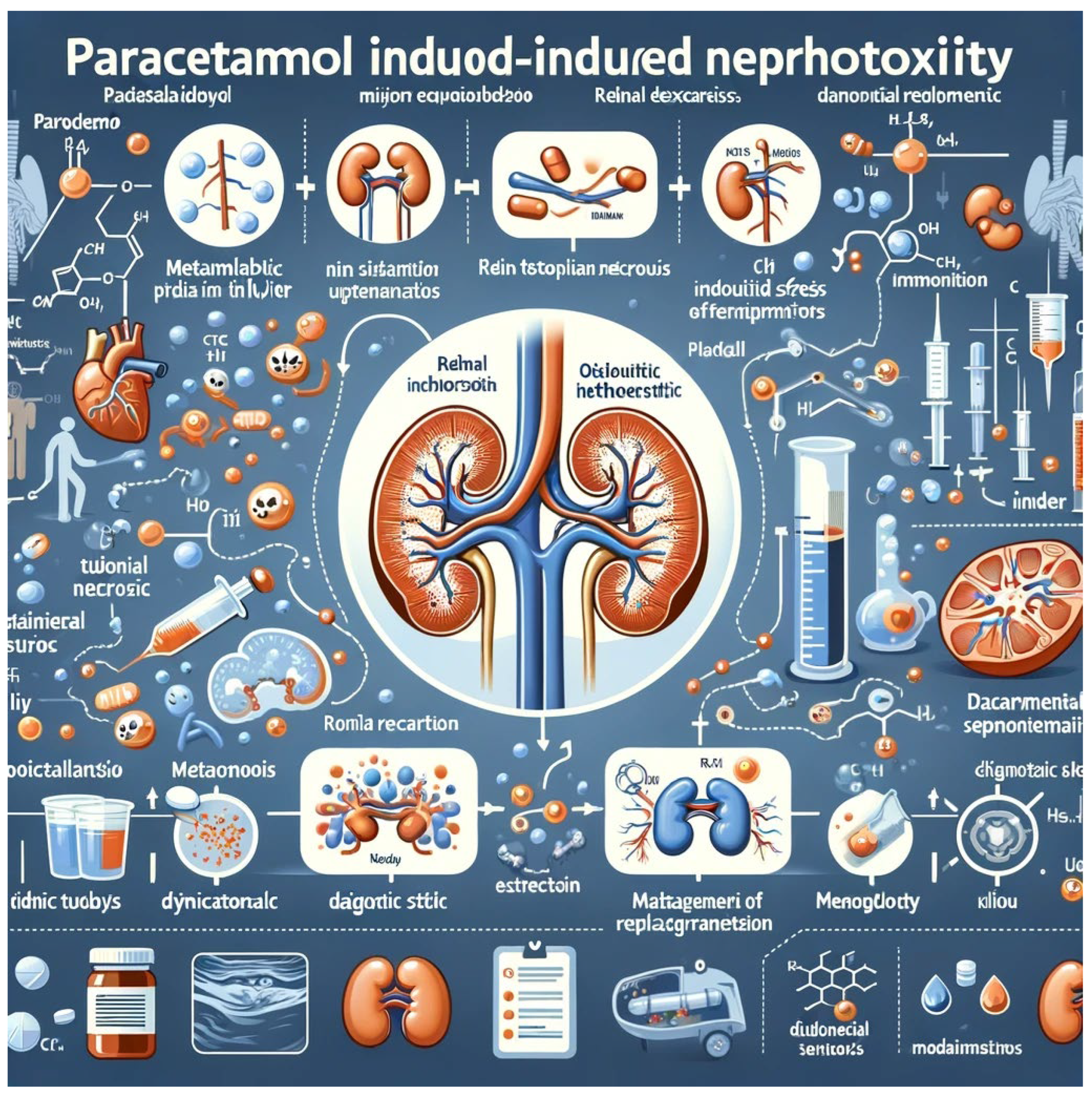

Organ-Specific Effects

- 1.

- Liver

- 2.

- Kidneys

- 3.

- Cardiovascular System

- 4.

- Gastrointestinal Tract

Risk Factors and Diagnostic Approaches

Management Strategies

Conclusion

References

- Ogemdi, I.K., A Review on the Properties and Uses of Paracetamol. International Journal of Pharmacy and Chemistry, 2019. 5(3): p. 31-35. [CrossRef]

- Brownson, R.C., et al., Measuring the built environment for physical activity: state of the science. American journal of preventive medicine, 2009. 36(4): p. S99-S123. e12. [CrossRef]

- Lindon, J.C., et al., Metabonomics technologies and their applications in physiological monitoring, drug safety assessment and disease diagnosis. Biomarkers, 2004. 9(1): p. 1-31. [CrossRef]

- Barbour, R.S. and M. Barbour, Evaluating and synthesizing qualitative research: the need to develop a distinctive approach. Journal of evaluation in clinical practice, 2003. 9(2): p. 179-186. [CrossRef]

- v. Wintzingerode, F., U.B. Göbel, and E. Stackebrandt, Determination of microbial diversity in environmental samples: pitfalls of PCR-based rRNA analysis. FEMS microbiology reviews, 1997. 21(3): p. 213-229.

- Graham, G.G., et al., The modern pharmacology of paracetamol: therapeutic actions, mechanism of action, metabolism, toxicity and recent pharmacological findings. Inflammopharmacology, 2013. 21: p. 201-232. [CrossRef]

- Graham, G.G., K.F. Scott, and R.O. Day, Tolerability of paracetamol. Drug safety, 2005. 28(3): p. 227-240. [CrossRef]

- Bessems, J.G. and N.P. Vermeulen, Paracetamol (acetaminophen)-induced toxicity: molecular and biochemical mechanisms, analogues and protective approaches. Critical reviews in toxicology, 2001. 31(1): p. 55-138. [CrossRef]

- Mazaleuskaya, L.L., et al., PharmGKB summary: pathways of acetaminophen metabolism at the therapeutic versus toxic doses. Pharmacogenetics and genomics, 2015. 25(8): p. 416-426.

- Vairetti, M., et al., Changes in glutathione content in liver diseases: an update. Antioxidants, 2021. 10(3): p. 364. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, E., et al., Acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity: a comprehensive update. Journal of clinical and translational hepatology, 2016. 4(2): p. 131. [CrossRef]

- Rotundo, L. and N. Pyrsopoulos, Liver injury induced by paracetamol and challenges associated with intentional and unintentional use. World journal of hepatology, 2020. 12(4): p. 125. [CrossRef]

- Locci, C., et al., Paracetamol overdose in the newborn and infant: a life-threatening event. European journal of clinical pharmacology, 2021. 77: p. 809-815. [CrossRef]

- FAthelrAhmAn, A.I., Ten challenges associated with management of paracetamol overdose: an update on current practice and relevant evidence from epidemiological and clinical studies. J Clin Diagnost Res, 2021. 15(3). [CrossRef]

- Squires, J.E., et al., North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition position paper on the diagnosis and management of pediatric acute liver failure. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition, 2022. 74(1): p. 138-158. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, A., et al., Current etiological comprehension and therapeutic targets of acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity. Pharmacological research, 2020. 161: p. 105102. [CrossRef]

- Gopinathan, S., Molecular mechanisms of liver injury induced by hepatotoxins. European Journal of Biomedical, 2016. 3(11): p. 229-237.

- Du, K., A. Ramachandran, and H. Jaeschke, Oxidative stress during acetaminophen hepatotoxicity: Sources, pathophysiological role and therapeutic potential. Redox biology, 2016. 10: p. 148-156. [CrossRef]

- Jaeschke, H., et al., Mitochondrial damage and biogenesis in acetaminophen-induced liver injury. Liver research, 2019. 3(3-4): p. 150-156. [CrossRef]

- Urrunaga, N.H., et al., M1 muscarinic receptors modify oxidative stress response to acetaminophen-induced acute liver injury. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 2015. 78: p. 66-81. [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, A. and H. Jaeschke, A mitochondrial journey through acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Food and chemical toxicology, 2020. 140: p. 111282. [CrossRef]

- Mahadevan, S.B., et al., Paracetamol induced hepatotoxicity. Archives of disease in childhood, 2006. 91(7): p. 598-603.

- Craig, D.G., et al., Overdose pattern and outcome in paracetamol-induced acute severe hepatotoxicity. British journal of clinical pharmacology, 2011. 71(2): p. 273-282. [CrossRef]

- Burcham, P.C. and P.C. Burcham, Target-organ toxicity: liver and kidney. An Introduction to Toxicology, 2014: p. 151-187.

- Ramos-Tovar, E. and P. Muriel, Molecular mechanisms that link oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrosis in the liver. Antioxidants, 2020. 9(12): p. 1279. [CrossRef]

- Riordan, S.M. and R. Williams, Alcohol exposure and paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity. Addiction biology, 2002. 7(2): p. 191-206. [CrossRef]

- Tompkins, L.M. and H. Wang, Liver Drug Metabolism. Oral Bioavailability: Basic Principles, Advanced Concepts, and Applications, 2011: p. 127-144.

- Kholili, U., et al., Liver injury associated with Acetaminophen: A Review. Research Journal of Pharmacy and Technology, 2023. 16(4): p. 2006-2012. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, S., K. Sinha, and P. C Sil, Cytochrome P450s: mechanisms and biological implications in drug metabolism and its interaction with oxidative stress. Current drug metabolism, 2014. 15(7): p. 719-742. [CrossRef]

- Stefanello, S.T., et al., Acetaminophen Oxidation and Inflammatory Markers–A Review of Hepatic Molecular Mechanisms and Preclinical Studies. Current Drug Targets, 2020. 21(12): p. 1225-1236. [CrossRef]

- Karunarathna, I., B. Rathnayake, and D. Kumari, Advancements in the Management of Acute Liver Failure: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment Strategies. Uva Clinical Lab. Retrieved from ResearchGate, 2024.

- Angeli, P., et al., EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Journal of hepatology, 2018. 69(2): p. 406-460. [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, S., R.K. Dhiman, and J.K. Limdi, Evaluation of abnormal liver function tests. Postgraduate medical journal, 2016. 92(1086): p. 223-234. [CrossRef]

- Rumack, B.H. and D.N. Bateman, Acetaminophen and acetylcysteine dose and duration: past, present and future. Clinical toxicology, 2012. 50(2): p. 91-98. [CrossRef]

- Vipani, A., C.C. Lindenmeyer, and V. Sundaram, Treatment of severe acute on chronic liver failure: management of organ failures, investigational therapeutics, and the role of liver transplantation. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, 2021. 55(8): p. 667-676.

- Wang, X., et al., Paracetamol: overdose-induced oxidative stress toxicity, metabolism, and protective effects of various compounds in vivo and in vitro. Drug metabolism reviews, 2017. 49(4): p. 395-437.

- Whelton, A., Nephrotoxicity of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: physiologic foundations and clinical implications. The American journal of medicine, 1999. 106(5): p. 13S-24S. [CrossRef]

- Pakravan, N., Paracetamol poisoning and its treatment in man. 2008.

- Waring, W.S. and A. Moonie, Earlier recognition of nephrotoxicity using novel biomarkers of acute kidney injury. Clinical toxicology, 2011. 49(8): p. 720-728. [CrossRef]

- Chambers, J.K., Fluid and electrolyte problems in renal and urologic disorders. Nursing Clinics of North America, 1987. 22(4): p. 815-826. [CrossRef]

- Mazer, M. and J. Perrone, Acetaminophen-induced nephrotoxicity: pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Journal of Medical Toxicology, 2008. 4: p. 2-6. [CrossRef]

- Mostbeck, G.H., T. Zontsich, and K. Turetschek, Ultrasound of the kidney: obstruction and medical diseases. European radiology, 2001. 11: p. 1878-1889. [CrossRef]

- Prowle, J.R., et al., Fluid balance and acute kidney injury. Nature Reviews Nephrology, 2010. 6(2): p. 107-115. [CrossRef]

- Paden, M.L., et al., Recovery of renal function and survival after continuous renal replacement therapy during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, 2011. 12(2): p. 153-158. [CrossRef]

- Alchin, J., et al., Why paracetamol (acetaminophen) is a suitable first choice for treating mild to moderate acute pain in adults with liver, kidney or cardiovascular disease, gastrointestinal disorders, asthma, or who are older. Current medical research and opinion, 2022. 38(5): p. 811-825. [CrossRef]

- Fanelli, A., et al., Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular risk with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitors: latest evidence and clinical implications. Therapeutic advances in drug safety, 2017. 8(6): p. 173-182. [CrossRef]

- Fulton, R.L., et al., Acetaminophen use and risk of myocardial infarction and stroke in a hypertensive cohort. Hypertension, 2015. 65(5): p. 1008-1014. [CrossRef]

- Moore, N., Coronary risks associated with diclofenac and other NSAIDs: an update. Drug safety, 2020. 43(4): p. 301-318. [CrossRef]

- Aksu, K., A. Donmez, and G. Keser, Inflammation-induced thrombosis: mechanisms, disease associations and management. Current pharmaceutical design, 2012. 18(11): p. 1478-1493.

- McCrae, J., et al., Long-term adverse effects of paracetamol–a review. British journal of clinical pharmacology, 2018. 84(10): p. 2218-2230. [CrossRef]

- Hassan-Ahmed, M., Renal function in a rat model of an analgesic nephropathy: Effect of chloroquine. 2002: The University of Manchester (United Kingdom). [CrossRef]

- Fokunang, C., et al., Overview of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (nsaids) in resource limited countries. Moj Toxicol, 2018. 4(1): p. 5-13.

- Graham, G. and M. Hicks, Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of paracetamol (acetaminophen), in Aspirin and related drugs. 2004, Taylor and Francis London. p. 181-213.

- Hassan, M.N., A Study on Drug’s Side Effects due to Using GIT Drugs Without Prescription in Lower Class People in Bangladesh. 2017, East West University.

- Pasupuleti, V.R., et al., Honey, propolis, and royal jelly: a comprehensive review of their biological actions and health benefits. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity, 2017. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Sostres, C., et al., Adverse effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs, aspirin and coxibs) on upper gastrointestinal tract. Best practice & research Clinical gastroenterology, 2010. 24(2): p. 121-132. [CrossRef]

- Penrose, A.J., Investigating the role of eyes absent homolog 1 (EYA1) in aspirin-induced gastric ulceration. 2019: The University of Liverpool (United Kingdom).

- Wehling, M., Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use in chronic pain conditions with special emphasis on the elderly and patients with relevant comorbidities: management and mitigation of risks and adverse effects. European journal of clinical pharmacology, 2014. 70: p. 1159-1172. [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.P., Drug management of visceral pain: concepts from basic research. Pain research and treatment, 2012. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Goodoory, V.C., et al., Willingness to accept risk with medication in return for cure of symptoms among patients with Rome IV irritable bowel syndrome. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 2022. 55(10): p. 1311-1319. [CrossRef]

- Kress, H.G. and G. Untersteiner, Clinical update on benefit versus risks of oral paracetamol alone or with codeine: still a good option? Current medical research and opinion, 2017. 33(2): p. 289-304.

- Jasat, H., et al., Prolonged use of paracetamol and the prescribing patterns on rehabilitation facilities. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 2022. 31(23-24): p. 3605-3616. [CrossRef]

- Yew, W., Clinically significant interactions with drugs used in the treatment of tuberculosis. Drug safety, 2002. 25: p. 111-113. [CrossRef]

- Caparrotta, T.M., D.J. Antoine, and J.W. Dear, Are some people at increased risk of paracetamol-induced liver injury? A critical review of the literature. European journal of clinical pharmacology, 2018. 74: p. 147-160. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, S.J., A.E. Kane, and S.N. Hilmer, Age-related changes in the hepatic pharmacology and toxicology of paracetamol. Current gerontology and geriatrics research, 2011. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, L.E., Paracetamol self-poisoning among adolescents in a department of hepatology. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 2001. 13(4): p. 327-334. [CrossRef]

- Rabinovitz, M. and D.H. Van Thiel, Hepatotoxicity of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. American Journal of Gastroenterology (Springer Nature), 1992. 87(12).

- Kozer, E. and G. Koren, Management of paracetamol overdose: current controversies. Drug safety, 2001. 24: p. 503-512.

- Roberts, D.M. and N.A. Buckley, Pharmacokinetic considerations in clinical toxicology: clinical applications. Clinical pharmacokinetics, 2007. 46: p. 897-939.

- Gowda, S., et al., A review on laboratory liver function tests. The Pan african medical journal, 2009. 3.

- Tripodi, A., et al., The prothrombin time test as a measure of bleeding risk and prognosis in liver disease. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics, 2007. 26(2): p. 141-148. [CrossRef]

- Bora, A., et al., Assessment of liver volume with computed tomography and comparison of findings with ultrasonography. Abdominal imaging, 2014. 39: p. 1153-1161. [CrossRef]

- Pettie, J. and M. Dow, Assessment and management of paracetamol poisoning in adults. Nursing Standard (through 2013), 2013. 27(45): p. 39.

- Dart, R.C., et al., Acetaminophen poisoning: an evidence-based consensus guideline for out-of-hospital management. Clinical Toxicology, 2006. 44(1): p. 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Higgs, A., et al., Guidelines for the management of tracheal intubation in critically ill adults. British journal of anaesthesia, 2018. 120(2): p. 323-352. [CrossRef]

- Chomchai, S., et al., Sensitivity of dose-estimations for acute acetaminophen overdose in predicting hepatotoxicity risk using the Rumack-Matthew Nomogram. Pharmacology Research & Perspectives, 2022. 10(1): p. e00920. [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.L., Mechanism of action and value of N-acetylcysteine in the treatment of early and late acetaminophen poisoning: a critical review. Journal of Toxicology: Clinical Toxicology, 1998. 36(4): p. 277-285. [CrossRef]

- Tenório, M.C.d.S., et al., N-acetylcysteine (NAC): impacts on human health. Antioxidants, 2021. 10(6): p. 967.

- Thorpy, M.J. and Y. Dauvilliers, Clinical and practical considerations in the pharmacologic management of narcolepsy. Sleep medicine, 2015. 16(1): p. 9-18. [CrossRef]

- Thummel, K.E., et al., Design and optimization of dosage regimens: pharmacokinetic data. Goodman & Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics, 2006. 11: p. 1787-1888.

- Makin, A. and R. Williams, The current management of paracetamol overdosage. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 1994. 48(3): p. 144-148. [CrossRef]

- Schultze, A.E., D. Ennulat, and A.D. Aulbach, Clinical pathology in nonclinical toxicity testing, in Haschek and Rousseaux's Handbook of Toxicologic Pathology. 2022, Elsevier. p. 295-334.

- Taylor, B.E., et al., Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN). Critical care medicine, 2016. 44(2): p. 390-438.

- Karunarathna, I., et al., Advancements in the Management of Acute Liver Failure: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment Strategies. Uva Clinical Lab. Retrieved from Advancements in the Management of Acute Liver Failure: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment Strategies, 2024.

- Polson, J. and W.M. Lee, AASLD position paper: the management of acute liver failure. Hepatology, 2005. 41(5): p. 1179-1197. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).