Submitted:

12 May 2024

Posted:

13 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Endocannabinoids

2.1. Pain Perception

2.2. Inflammation

2.3. Mood and Emotion

2.4. Appetite and Metabolism

2.5. Immune Function

2.6. Neuroprotection and Neuropathy

3. Peripheral Nervous System

3.1. Manifestations

3.2. Diagnosis, Treatment and Management

3.3. Anandamide (AEA)

3.4. Two-Arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG)

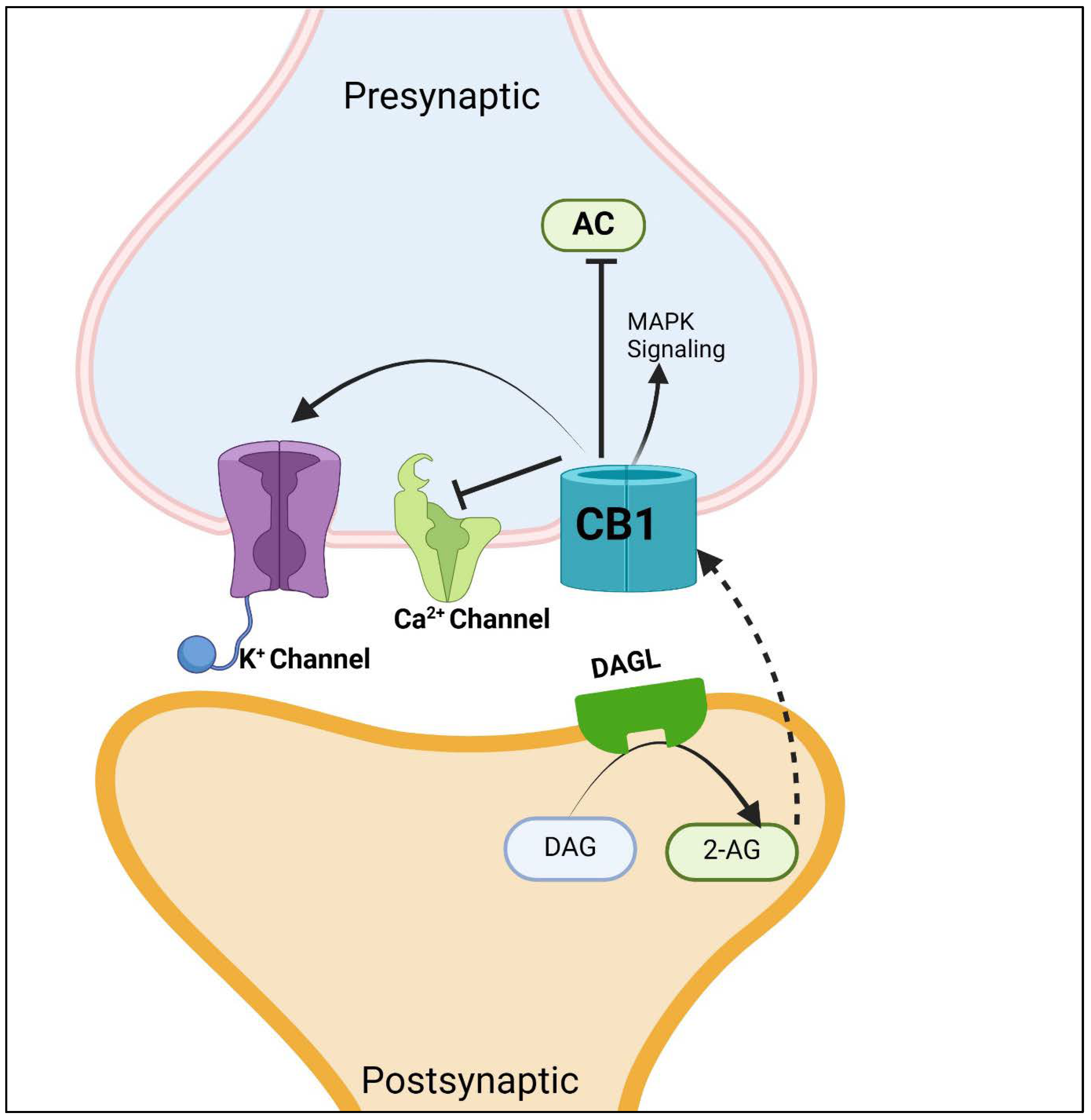

4. Endocannabinoid Receptor Type 1 (CB1)

4.1. The Role of CB1 Receptors in Inflammatory Disorders

4.2. Therapeutic Potential of CB1 Modulation

5. Endocannabinoid Receptor Type 2 (CB2)

5.1. CB2 Receptors and Inflammatory Disorders

5.2. Therapeutic Potential of CB2 Modulation

6. CB1 and CB2 Specific Neuropathies

6.1. Diabetic Neuropathy

6.2. Peripheral Neuropathy

6.3. HIV-Associated Neuropathy

6.4. Chemotherapy-Induced Neuropathy

6.5. Cannabis Hyperemesis Syndrome (CHS)

References

- Ramirez, C.E.M.; Ruiz-Pérez, G.; Stollenwerk, T.M.; Behlke, C.; Doherty, A.; Hillard, C.J. Endocannabinoid signaling in the central nervous system. Glia 2022, 71, 5–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutz, B. Neurobiology of cannabinoid receptor signaling. Dialog- Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 22, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greco, R.; Demartini, C.; Zanaboni, A.M.; Francavilla, M.; De Icco, R.; Ahmad, L.; Tassorelli, C. The endocannabinoid system and related lipids as potential targets for the treatment of migraine-related pain. Headache J. Head Face Pain 2022, 62, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chanda, D., Neumann, D. and Glatz, J.F., 2019. The endocannabinoid system: Overview of an emerging multi-faceted therapeutic target. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids, 140, pp.51-56.

- Komarnytsky, S.; Rathinasabapathy, T.; Wagner, C.; Metzger, B.; Carlisle, C.; Panda, C.; Le Brun-Blashka, S.; Troup, J.P.; Varadharaj, S. Endocannabinoid System and Its Regulation by Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Full Spectrum Hemp Oils. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilaru, A. and Chapman, K.D., 2020. The endocannabinoid system. Essays in Biochemistry, 64(3), pp.485-499.

- Finn, D.P.; Haroutounian, S.; Hohmann, A.G.; Krane, E.; Soliman, N.; Rice, A.S. Cannabinoids, the endocannabinoid system, and pain: A review of preclinical studies. Pain 2021, 162, S5–S25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, S., Gould, G.G., Antonucci, N., Brigida, A.L. and Siniscalco, D., 2021. Endocannabinoid system dysregulation from acetaminophen use may lead to autism spectrum disorder: Could cannabinoid treatment be efficacious? Molecules, 26(7), p.1845.

- Petrie, G., Balsevich, G., Fuzesi, T., Aukema, R., Wouter, D., Van der Stelt, M., Bains, J.S. and Hill, M.N., 2022. Disruption of Tonic Endocannabinoid Signaling Triggers the Generation of a Stress Response. bioRxiv, pp.2022-09.

- Lowe, H.; Toyang, N.; Steele, B.; Bryant, J.; Ngwa, W. The Endocannabinoid System: A Potential Target for the Treatment of Various Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann, H.C., Wunderlich, G., Fink, G.R. and Sommer, C., 2020. Diagnosis of peripheral neuropathy. Neurological research and practice, 2, pp.1-7.

- Khan, Z.; Ahmad, U.; Ualiyeva, D.; Amissah, O.B.; Khan, A.; Noor, Z.; Zaman, N. Guillain-Barre syndrome: An autoimmune disorder post-COVID-19 vaccination? Clin. Immunol. Commun. 2022, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karjalanen, T.; Raatikainen, S.; Jaatinen, K.; Lusa, V. Update on Efficacy of Conservative Treatments for Carpal Tunnel Syndrome. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, R.M.P.; Aguiar, A.F.L.; Paes-Colli, Y.; Trindade, P.M.P.; Ferreira, B.K.; Reis, R.A.d.M.; Sampaio, L.S. Cannabinoid Therapeutics in Chronic Neuropathic Pain: From Animal Research to Human Treatment. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Behl, T.; Sharma, L.; Shah, O.P.; Yadav, S.; Sachdeva, M.; Rashid, S.; Bungau, S.G.; Bustea, C. Exploring the molecular pathways and therapeutic implications of angiogenesis in neuropathic pain. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 162, 114693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svensson, C.K., 2020. CBD for the treatment of pain: What is the evidence? Journal of the American Pharmacists Association, 60(6), pp.e80-e83.

- Prospéro-García, O.; Contreras, A.E.R.; Gómez, A.O.; Herrera-Solís, A.; Méndez-Díaz, M. Endocannabinoids as Therapeutic Targets. Arch. Med Res. 2019, 50, 518–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez-López, A.; Pastor, A.; de la Torre, R.; La Porta, C.; Ozaita, A.; Cabañero, D.; Maldonado, R. Role of the endocannabinoid system in a mouse model of Fragile X undergoing neuropathic pain. Eur. J. Pain 2021, 25, 1316–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, C.J. The endocannabinoid system – current implications for drug development. J. Intern. Med. 2020, 290, 2–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wołyniak, M.; Małecka-Wojciesko, E.; Zielińska, M.; Fabisiak, A. A Crosstalk between the Cannabinoid Receptors and Nociceptin Receptors in Colitis—Clinical Implications. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finn, D.P.; Haroutounian, S.; Hohmann, A.G.; Krane, E.; Soliman, N.; Rice, A.S. Cannabinoids, the endocannabinoid system, and pain: a review of preclinical studies. Pain 2021, 162, S5–S25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osafo, N., Yeboah, O.K. and Antwi, A.O., 2021. The endocannabinoid system and its modulation of the brain, gut, joint, and skin inflammation. Molecular biology reports, 48(4), pp.3665-3680.

- Hryhorowicz, S.; Kaczmarek-Ryś, M.; Zielińska, A.; Scott, R.J.; Słomski, R.; Pławski, A. Endocannabinoid System as a Promising Therapeutic Target in Inflammatory Bowel Disease – A Systematic Review. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 790803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheau, C.; Draghici, C.; Ilie, M.A.; Lupu, M.; Solomon, I.; Tampa, M.; Georgescu, S.R.; Caruntu, A.; Constantin, C.; Neagu, M.; et al. Neuroendocrine Factors in Melanoma Pathogenesis. Cancers 2021, 13, 2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, I.; Syamala, S.; Ayariga, J.A.; Xu, J.; Robertson, B.K.; Meenakshisundaram, S.; Ajayi, O.S. Modulatory Effect of Gut Microbiota on the Gut-Brain, Gut-Bone Axes, and the Impact of Cannabinoids. Metabolites 2022, 12, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garani, R., Watts, J.J. and Mizrahi, R., 2021. The endocannabinoid system in psychotic and mood disorders, a review of human studies. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 106, p.110096.

- Pinna, G. Endocannabinoids and Precision Medicine for Mood Disorders and Suicide. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stasiulewicz, A.; Znajdek, K.; Grudzień, M.; Pawiński, T.; Sulkowska, J.I. A Guide to Targeting the Endocannabinoid System in Drug Design. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arjmand, S.; Behzadi, M.; Kohlmeier, K.A.; Mazhari, S.; Sabahi, A.; Shabani, M. Bipolar disorder and the endocannabinoid system. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2019, 31, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, M.N.; Zachut, M.; Tam, J.; Contreras, G.A. A proposed modulatory role of the endocannabinoid system on adipose tissue metabolism and appetite in periparturient dairy cows. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2021, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behl, T.; Chadha, S.; Sachdeva, M.; Sehgal, A.; Kumar, A.; Dhruv; Venkatachalam, T.; Hafeez, A.; Aleya, L.; Arora, S.; et al. Understanding the possible role of endocannabinoid system in obesity. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2020, 152, 106520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Marzo, V. and Silvestri, C., 2019. Lifestyle and metabolic syndrome: Contribution of the endocannabinoidome. Nutrients, 11(8), p.1956.

- McDew-White, M.; Lee, E.; Premadasa, L.S.; Alvarez, X.; Okeoma, C.M.; Mohan, M. Cannabinoids modulate the microbiota–gut–brain axis in HIV/SIV infection by reducing neuroinflammation and dysbiosis while concurrently elevating endocannabinoid and indole-3-propionate levels. J. Neuroinflammation 2023, 20, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, L.; Shu, Z.; Gu, X.; Wu, Y.; Yang, J.; Deng, H. The Endocannabinoid System as a Potential Therapeutic Target for HIV-1-Associated Neurocognitive Disorder. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2023, 8, 445–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costiniuk, C.T. and Jenabian, M.A., 2019. Cannabinoids and inflammation: Implications for people living with HIV. Aids, 33(15), pp.2273-2288.

- Argenziano, M.; Tortora, C.; Bellini, G.; Di Paola, A.; Punzo, F.; Rossi, F. The Endocannabinoid System in Pediatric Inflammatory and Immune Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopustinskiene, D.M.; Masteikova, R.; Lazauskas, R.; Bernatoniene, J. Cannabis sativa L. Bioactive Compounds and Their Protective Role in Oxidative Stress and Inflammation. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, A.P., Patil, T.M., Shinde, A.R., Vakhariya, R.R., Mohite, S.K. and Magdum, C.S., 2021. Nutrition, lifestyle, and immunity: Maintaining optimal immune function and boosting our immunity. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical Research and Development, 9(3), pp.129-136.

- Dokalis, N. and Prinz, M., 2019, November. Resolution of neuroinflammation: Mechanisms and potential therapeutic option. In Seminars in immunopathology (Vol. 41, No. 6, pp. 699-709). Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Yang, H.; Zeng, Q.; Silverman, H.A.; Gunasekaran, M.; George, S.J.; Devarajan, A.; Addorisio, M.E.; Li, J.; Tsaava, T.; Shah, V.; et al. HMGB1 released from nociceptors mediates inflammation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien. K., Blair, P., O’Brien, K. and Blair, P., 2021. Endocannabinoid System. Medicinal Cannabis and CBD in Mental Healthcare.

- Cristino, L.; Bisogno, T.; Di Marzo, V. Cannabinoids and the expanded endocannabinoid system in neurological disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2020, 16, 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, K.M. and Piomelli, D., 2022. Cannabinoids and endocannabinoids. In Neuroscience in the 21st Century: From Basic to Clinical (pp. 2129-2157). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- van Egmond, N., Straub, V.M. and van der Stelt, M., 2021. Targeting endocannabinoid signaling: FAAH and MAG lipase inhibitors. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology, 61, pp.441-463.

- Ibrahim, I., Ayariga, J.A., Xu, J., Adebanjo, A., Robertson, B.K., Samuel-Foo, M. and Ajayi, O.S., 2023. CBD-resistant Salmonella strains are susceptible to epsilon 34 phage tailspike protein. Frontiers in Medicine, 10, p.1075698.

- Spiller, K.J., Bi, G.H., He, Y., Galaj, E., Gardner, E.L. and Xi, Z.X., 2019. Cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptor mechanisms underlie cannabis reward and aversion in rats. British Journal of Pharmacology, 176(9), pp.1268-1281.

- Feldman, E.L., Callaghan, B.C., Pop-Busui, R., Zochodne, D.W., Wright, D.E., Bennett, D.L., Bril, V., Russell, J.W. and Viswanathan, V., 2019. Diabetic neuropathy. Nature Reviews Disease primers, 5(1), p.41.

- Sloan, G.; Selvarajah, D.; Tesfaye, S. Pathogenesis, diagnosis and clinical management of diabetic sensorimotor peripheral neuropathy. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2021, 17, 400–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans-Martin, F., 2022. The nervous system. Infobase Holdings, Inc.

- Oaklander, A.L.; Mills, A.J.; Kelley, M.; Toran, L.S.; Smith, B.; Dalakas, M.C.; Nath, A. Peripheral Neuropathy Evaluations of Patients With Prolonged Long COVID. Neurol. - Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflammation 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvarajah, D.; Kar, D.; Khunti, K.; Davies, M.J.; Scott, A.R.; Walker, J.; Tesfaye, S. Diabetic peripheral neuropathy: Advances in diagnosis and strategies for screening and early intervention. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019, 7, 938–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finnerup, N.B.; Kuner, R.; Jensen, T.S. Neuropathic Pain: From Mechanisms to Treatment. Physiol. Rev. 2021, 101, 259–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, T.S.; Karlsson, P.; Gylfadottir, S.S.; Andersen, S.T.; Bennett, D.L.; Tankisi, H.; Finnerup, N.B.; Terkelsen, A.J.; Khan, K.; Themistocleous, A.C.; et al. Painful and non-painful diabetic neuropathy, diagnostic challenges and implications for future management. Brain 2021, 144, 1632–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisse, A.L., Motte, J., Grüter, T., Sgodzai, M., Pitarokoili, K. and Gold, R., 2020. Comprehensive approaches for diagnosing, monitoring, and treating chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. Neurological research and practice, 2(1), pp.1-14.

- Pop-Busui, R.; Ang, L.; Boulton, A.; Feldman, E.L.; Marcus, R.; Mizokami-Stout, K.; Singleton, J.R.; Ziegler, D. Diagnosis and Treatment of Painful Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy. ADA Clin. Compend. 2022, 2022, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaikh, M., 2023. Assessing Neuropathy Risk and Quality of Life in Sedentary Obese, Prediabetic, and Type 2 Diabetic Populations: A Comprehensive Questionnaire-Based Approach. Clinical Images and Case Reports, 1(01), pp.29-38.

- Matei, D.; Trofin, D.; Iordan, D.A.; Onu, I.; Condurache, I.; Ionite, C.; Buculei, I. The Endocannabinoid System and Physical Exercise. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryk, M.; Chwastek, J.; Kostrzewa, M.; Mlost, J.; Pędracka, A.; Starowicz, K. Alterations in Anandamide Synthesis and Degradation during Osteoarthritis Progression in an Animal Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yagin, N.L.; Aliasgharzadeh, S.; Alizadeh, M.; Aliasgari, F.; Mahdavi, R. The association of circulating endocannabinoids with appetite regulatory substances in obese women. Obes. Res. Clin. Pr. 2020, 14, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, D., Ramesh, S., Deruiter, J., Govindarajulu, M., Lowery, P., Moore, T., Agrawal, D.C. and Dhanasekaran, M., 2022. Neuropharmacological Approaches to Modulate Cannabinoid Neurotransmission. In Cannabis/Marijuana for Healthcare (pp. 35-52). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

- Silveira, K.M.; Wegener, G.; Joca, S.R.L. Targeting 2-arachidonoylglycerol signalling in the neurobiology and treatment of depression. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2021, 129, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hohmann, U., Pelzer, M., Kleine, J., Hohmann, T., Ghadban, C. and Dehghani, F., 2019. Opposite effects of neuroprotective cannabinoids, palmitoylethanolamide, and 2-arachidonoylglycerol on function and morphology of microglia. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 13, p.1180.

- Agrawal, I.; Lim, Y.S.; Ng, S.-Y.; Ling, S.-C. Deciphering lipid dysregulation in ALS: From mechanisms to translational medicine. Transl. Neurodegener. 2022, 11, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokona, D., Spyridakos, D., Tzatzarakis, M., Papadogkonaki, S., Filidou, E., Arvanitidis, K.I., Kolios, G., Lamani, M., Makriyannis, A., Malamas, M.S. and Thermos, K., 2021. The endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol and dual ABHD6/MAGL enzyme inhibitors display neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory actions in the in vivo retinal model of AMPA excitotoxicity. Neuropharmacology, 185, p.108450.

- Pete, D.D. and Narouze, S.N., 2021. Endocannabinoids: Anandamide and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG). In Cannabinoids and Pain (pp. 63-69). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Maia, J.; Fonseca, B.M.; Cunha, S.C.; Braga, J.; Gonçalves, D.; Teixeira, N.; Correia-Da-Silva, G. Impact of tetrahydrocannabinol on the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol metabolism: ABHD6 and ABHD12 as novel players in human placenta. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2020, 1865, 158807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simard, M.; Rakotoarivelo, V.; Di Marzo, V.; Flamand, N. Expression and Functions of the CB2 Receptor in Human Leukocytes. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 826400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahaman, O.; Ganguly, D. Endocannabinoids in immune regulation and immunopathologies. Immunology 2021, 164, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.S.; Paddibhatla, I.; Raghuwanshi, S.; Malleswarapu, M.; Sangeeth, A.; Kovuru, N.; Dahariya, S.; Gautam, D.K.; Pallepati, A.; Gutti, R.K. Endocannabinoid system: Role in blood cell development, neuroimmune interactions and associated disorders. J. Neuroimmunol. 2021, 353, 577501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuddihey, H.; MacNaughton, W.K.; Sharkey, K.A. Role of the Endocannabinoid System in the Regulation of Intestinal Homeostasis. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 14, 947–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terral, G.; Marsicano, G.; Grandes, P.; Soria-Gómez, E. Cannabinoid Control of Olfactory Processes: The Where Matters. Genes 2020, 11, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Moncada, I.; Rodrigues, R.S.; Fundazuri, U.B.; Bellocchio, L.; Marsicano, G. Type-1 cannabinoid receptors and their ever-expanding roles in brain energy processes. J. Neurochem. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.T.; Mackie, K.; Chiou, L. Alternative pain management via endocannabinoids in the time of the opioid epidemic: Peripheral neuromodulation and pharmacological interventions. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 180, 894–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, A.K., Renda, B. and Murray, J.E., 2019. Cannabinoids, interoception, and anxiety. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 180, pp.60-73.

- Sideli, L.; Quigley, H.; La Cascia, C.; Murray, R.M. Cannabis Use and the Risk for Psychosis and Affective Disorders. J. Dual Diagn. 2019, 16, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niloy, N.; Hediyal, T.A.; Vichitra, C.; Sonali, S.; Chidambaram, S.B.; Gorantla, V.R.; Mahalakshmi, A.M. Effect of Cannabis on Memory Consolidation, Learning and Retrieval and Its Current Legal Status in India: A Review. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schurman, L.D., Lu, D., Kendall, D.A., Howlett, A.C. and Lichtman, A.H., 2020. Molecular mechanism and cannabinoid pharmacology. Substance Use Disorders: From Etiology to Treatment, pp.323-353.

- O’Sullivan, S.E., Yates, A.S. and Porter, R.K., 2021. The peripheral cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1) is a molecular target for modulating body weight in men. Molecules, 26(20), p.6178.

- Hurel, I., Muguruza, C., Redon, B., Marsicano, G. and Chaouloff, F., 2021. Cannabis and exercise: Effects of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol on mice’s preference and motivation for wheel-running. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 105, p.110117.

- Zhornitsky, S.; Pelletier, J.; Assaf, R.; Giroux, S.; Li, C.-S.R.; Potvin, S. Acute effects of partial CB1 receptor agonists on cognition – A meta-analysis of human studies. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol. Psychiatry 2020, 104, 110063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddad, M. The Impact of CB1 Receptor on Inflammation in Skeletal Muscle Cells. J. Inflamm. Res. 2021, 14, 3959–3967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillamat-Prats, R.; Rami, M.; Herzig, S.; Steffens, S. Endocannabinoid Signalling in Atherosclerosis and Related Metabolic Complications. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2019, 119, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, I.; Rehman, S.U.; Shahmohamadnejad, S.; Zia, M.A.; Ahmad, M.; Saeed, M.M.; Akram, Z.; Iqbal, H.M.N.; Liu, Q. Therapeutic Attributes of Endocannabinoid System against Neuro-Inflammatory Autoimmune Disorders. Molecules 2021, 26, 3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson-Poe, A.R.; Wiese, B.; Kibaly, C.; Lueptow, L.; Garcia, J.; Anand, P.; Cahill, C.; Moron, J.A. Effects of inflammatory pain on CB1 receptor in the midbrain periaqueductal gray. PAIN Rep. 2021, 6, e897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, A.T.; Rahmat, S.; Sangle, P.; Sandhu, O.; Khan, S. Cannabinoid Receptors and Their Relationship With Chronic Pain: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, E.Y.; Cha, H.J.; Min, H.K.; Yun, J. Pharmacology and adverse effects of new psychoactive substances: Synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2021, 44, 402–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thapa, D.; Cairns, E.A.; Szczesniak, A.-M.; Kulkarni, P.M.; Straiker, A.J.; Thakur, G.A.; Kelly, M.E.M. Allosteric Cannabinoid Receptor 1 (CB1) Ligands Reduce Ocular Pain and Inflammation. Molecules 2020, 25, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozdemir, E. The Role of the Cannabinoid System in Opioid Analgesia and Tolerance. Mini-Reviews Med. Chem. 2020, 20, 875–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, T., Li, X., Wu, L., Iliopoulos-Tsoutsouvas, C., Wang, Y., Wu, M., Shen, L., Brust, C.A., Nikas, S.P., Song, F. and Song, X., 2020. Activation and signaling mechanism revealed by cannabinoid receptor-Gi complex structures. Cell, 180(4), pp.655-665.

- Kędziora, M.; Boccella, S.; Marabese, I.; Mlost, J.; Infantino, R.; Maione, S.; Starowicz, K. Inhibition of anandamide breakdown reduces pain and restores LTP and monoamine levels in the rat hippocampus via the CB1 receptor following osteoarthritis. Neuropharmacology 2023, 222, 109304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mielnik, C.A.; Lam, V.M.; Ross, R.A. CB1 allosteric modulators and their therapeutic potential in CNS disorders. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol. Psychiatry 2020, 106, 110163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavalli, J.M.; Cservenka, A. Emotion Dysregulation Moderates the Association Between Stress and Problematic Cannabis Use. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarragon, E. and Moreno, J.J., 2019. Cannabinoids, chemical senses, and regulation of feeding behavior. Chemical senses, 44(2), pp.73-89.

- Ibrahim, N.A.M., Mansour, Y.S.E. and Sulieman, A.A., 2019. Antiemetic medications: Agents, current research, and future directions. International Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, pp.7-14.

- Landucci, E.; Berlinguer-Palmini, R.; Baccini, G.; Boscia, F.; Gerace, E.; Mannaioni, G.; Pellegrini-Giampietro, D.E. The Neuroprotective Effects of mGlu1 Receptor Antagonists Are Mediated by an Enhancement of GABAergic Synaptic Transmission via a Presynaptic CB1 Receptor Mechanism. Cells 2022, 11, 3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindner, T.; Schmidl, D.; Peschorn, L.; Pai, V.; Popa-Cherecheanu, A.; Chua, J.; Schmetterer, L.; Garhöfer, G. Therapeutic Potential of Cannabinoids in Glaucoma. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarrete, F.; García-Gutiérrez, M.S.; Gasparyan, A.; Navarro, D.; López-Picón, F.; Morcuende, Á.; Femenía, T.; Manzanares, J. Biomarkers of the Endocannabinoid System in Substance Use Disorders. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakotoarivelo, V.; Sihag, J.; Flamand, N. Role of the Endocannabinoid System in the Adipose Tissue with Focus on Energy Metabolism. Cells 2021, 10, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsicano, G. and Kuner, R., 2008. Anatomical distribution of receptors, ligands, and enzymes in the brain and the spinal cord: Circuitries and neurochemistry. In Cannabinoids and the Brain (pp. 161-201). Boston, MA: Springer US.

- Zhang, J.; Hoffert, C.; Vu, H.K.; Groblewski, T.; Ahmad, S.; O’Donnell, D. Induction of CB2 receptor expression in the rat spinal cord of neuropathic but not inflammatory chronic pain models. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2003, 17, 2750–2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onaivi, E.S.; Ishiguro, H.; Gong, J.P.; Patel, S.; Perchuk, A.; Meozzi, P.A.; Myers, L.; Mora, Z.; Tagliaferro, P.; Gardner, E.; et al. Discovery of the Presence and Functional Expression of Cannabinoid CB2 Receptors in Brain. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1074, 514–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiura, T.; Kishimoto, S.; Oka, S.; Gokoh, M. Biochemistry, pharmacology and physiology of 2-arachidonoylglycerol, an endogenous cannabinoid receptor ligand. Prog. Lipid Res. 2006, 45, 405–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascual, A.C.; Gaveglio, V.L.; Giusto, N.M.; Pasquaré, S.J. Cannabinoid receptor-dependent metabolism of 2-arachidonoylglycerol during aging. Exp. Gerontol. 2014, 55, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toguri, J.T., Lehmann, C., Laprairie, R.B., Szczesniak, A.M., Zhou, J., Denovan-Wright, E.M. and Kelly, M.E.M., 2014. Anti-inflammatory effects of cannabinoid CB2 receptor activation in endotoxin-induced uveitis. British Journal of Pharmacology, 171(6), pp.1448-1461.

- Capozzi, A.; Caissutti, D.; Mattei, V.; Gado, F.; Martellucci, S.; Longo, A.; Recalchi, S.; Manganelli, V.; Riitano, G.; Garofalo, T.; et al. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of a CB2 Selective Cannabinoid Receptor Agonist: Signaling and Cytokines Release in Blood Mononuclear Cells. Molecules 2021, 27, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turcotte, C.; Blanchet, M.-R.; LaViolette, M.; Flamand, N. The CB2 receptor and its role as a regulator of inflammation. Cell. Mol. life Sci. 2016, 73, 4449–4470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benito, C.; Tolón, R.M.; Pazos, M.R.; Núñez, E.; I Castillo, A.; Romero, J. Cannabinoid CB2 receptors in human brain inflammation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 153, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashton, J.C.; Glass, M. The Cannabinoid CB2 Receptor as a Target for Inflammation-Dependent Neurodegeneration. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2007, 5, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y. and Watkins, B.A., 2021. Endocannabinoids and aging—inflammation, neuroplasticity, mood and pain. In Vitamins and Hormones (Vol. 115, pp. 129-172). Academic Press.

- Cravatt, B.F.; Demarest, K.; Patricelli, M.P.; Bracey, M.H.; Giang, D.K.; Martin, B.R.; Lichtman, A.H. Supersensitivity to anandamide and enhanced endogenous cannabinoid signaling in mice lacking fatty acid amide hydrolase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2001, 98, 9371–9376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blesching, U., 2020. Your Cannabis CBD: THC Ratio: A Guide to Precision Dosing for Health and Wellness. Ed Rosenthal.

- Aziz, A.-I.; Nguyen, L.C.; Oumeslakht, L.; Bensussan, A.; Ben Mkaddem, S. Cannabinoids as Immune System Modulators: Cannabidiol Potential Therapeutic Approaches and Limitations. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2022, 8, 254–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gildea, L., Ayariga, J.A., Ajayi, O.S., Xu, J., Villafane, R. and Samuel-Foo, M., 2022. Cannabis sativa CBD extract shows promising antibacterial activity against Salmonella Typhimurium and S. newington. Molecules, 27(9), p.2669.

- Hashiesh, H.M.; Sharma, C.; Goyal, S.N.; Jha, N.K.; Ojha, S. Pharmacological Properties, Therapeutic Potential and Molecular Mechanisms of JWH133, a CB2 Receptor-Selective Agonist. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 702675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Docagne, F.; Mestre, L.; Loría, F.; Hernangómez, M.; Correa, F.; Guaza, C. Therapeutic potential of CB2 targeting in multiple sclerosis. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2008, 12, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, M.P., 2014. Cannabinoids in pain management: CB1, CB2 and non-classic receptor ligands. Expert opinion on investigational drugs, 23(8), pp.1123-1140.

- Guindon, J.; Hohmann, A.G. Cannabinoid CB2 receptors: a therapeutic target for the treatment of inflammatory and neuropathic pain. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 153, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desroches, J.; Beaulieu, P. Opioids and Cannabinoids Interactions: Involvement in Pain Management. Curr. Drug Targets 2010, 11, 462–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Docagne, F.; Muñetón, V.; Clemente, D.; Ali, C.; Loría, F.; Correa, F.; Hernangómez, M.; Mestre, L.; Vivien, D.; Guaza, C. Excitotoxicity in a chronic model of multiple sclerosis: Neuroprotective effects of cannabinoids through CB1 and CB2 receptor activation. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2007, 34, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morcuende, A.; García-Gutiérrez, M.S.; Tambaro, S.; Nieto, E.; Manzanares, J.; Femenia, T. Immunomodulatory Role of CB2 Receptors in Emotional and Cognitive Disorders. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 866052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.N. and Gorzalka, B.B., 2009. The endocannabinoid system and the treatment of mood and anxiety disorders. CNS & Neurological Disorders-Drug Targets (Formerly Current Drug Targets-CNS & Neurological Disorders), 8(6), pp.451-458.

- Preet, A., Qamri, Z., Nasser, M.W., Prasad, A., Shilo, K., Zou, X., Groopman, J.E. and Ganju, R.K., 2011. Cannabinoid receptors, CB1 and CB2, are novel targets for inhibiting non–small cell lung cancer growth and metastasis. Cancer prevention research, 4(1), pp.65-75.

- Nasser, M.W.; Qamri, Z.; Deol, Y.S.; Smith, D.; Shilo, K.; Zou, X.; Ganju, R.K. Crosstalk between Chemokine Receptor CXCR4 and Cannabinoid Receptor CB2 in Modulating Breast Cancer Growth and Invasion. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Marzo, V., Piscitelli, F. and Mechoulam, R., 2011. Cannabinoids and endocannabinoids in metabolic disorders with a focus on diabetes. Diabetes-Perspectives in Drug Therapy, pp.75-104.

- Scheen, A.J.; Paquot, N. Use of cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonists for the treatment of metabolic disorders. Best Pr. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 23, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steffens, S.; Pacher, P. Targeting cannabinoid receptor CB2 in cardiovascular disorders: Promises and controversies. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 167, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Sullivan, S.E., 2015. Endocannabinoids and the cardiovascular system in health and disease. Endocannabinoids, pp.393-422.

- Elmes, S.J.; Winyard, L.A.; Medhurst, S.J.; Clayton, N.M.; Wilson, A.W.; Kendall, D.A.; Chapman, V. Activation of CB1 and CB2 receptors attenuates the induction and maintenance of inflammatory pain in the rat. Pain 2005, 118, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikeda, H.; Ikegami, M.; Kai, M.; Ohsawa, M.; Kamei, J. Activation of spinal cannabinoid CB2 receptors inhibits neuropathic pain in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Neuroscience 2013, 250, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vera, G.; López-Miranda, V.; Herradón, E.; Martín, M.I.; Abalo, R. Characterization of cannabinoid-induced relief of neuropathic pain in rat models of type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2012, 102, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toth, C.C.; Jedrzejewski, N.M.; Ellis, C.L.; Frey, W.H. Cannabinoid-Mediated Modulation of Neuropathic Pain and Microglial Accumulation in a Model of Murine Type I Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathic Pain. Mol. Pain 2010, 6, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Challapalli, S.C.; Smith, P.J. Cannabinoid CB1 receptor activation stimulates neurite outgrowth and inhibits capsaicin-induced Ca2+ influx in an in vitro model of diabetic neuropathy. Neuropharmacology 2009, 57, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Xu, Z.; Carey, L.; Romero, J.; Makriyannis, A.; Hillard, C.J.; Ruggiero, E.; Dockum, M.; Houk, G.; Mackie, K.; et al. A peripheral CB2 cannabinoid receptor mechanism suppresses chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: Evidence from a CB2 reporter mouse. Pain 2021, 163, 834–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavaletti, G., Alberti, P., Frigeni, B., Piatti, M. and Susani, E., 2011. Chemotherapy-induced neuropathy. Current treatment options in neurology, 13, pp.180-190.

- Maldonado, R.; Baños, J.E.; Cabañero, D. The endocannabinoid system and neuropathic pain. Pain 2016, 157, S23–S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svíženská, I., Dubový, P. and Šulcová, A., 2008. Cannabinoid receptors 1 and 2 (CB1 and CB2), their distribution, ligands and functional involvement in nervous system structures—a short review. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 90(4), pp.501-511.

- Benito, C.; Romero, J.P.; Tolón, R.M.; Clemente, D.; Docagne, F.; Hillard, C.J.; Guaza, C.; Romero, J. Cannabinoid CB1and CB2Receptors and Fatty Acid Amide Hydrolase Are Specific Markers of Plaque Cell Subtypes in Human Multiple Sclerosis. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 2396–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aly, E.; Masocha, W. Targeting the endocannabinoid system for management of HIV-associated neuropathic pain: A systematic review. IBRO Neurosci. Rep. 2021, 10, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eibach, L., Scheffel, S., Cardebring, M., Lettau, M., Özgür Celik, M., Morguet, A., Roehle, R. and Stein, C., 2021. Cannabidivarin for HIV-associated neuropathic pain: a randomized, blinded, controlled clinical trial. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 109(4), pp.1055-1062.

- Munawar, N.; Oriowo, M.A.; Masocha, W. Antihyperalgesic Activities of Endocannabinoids in a Mouse Model of Antiretroviral-Induced Neuropathic Pain. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahn, E.J.; Zvonok, A.M.; Thakur, G.A.; Khanolkar, A.D.; Makriyannis, A.; Hohmann, A.G. Selective Activation of Cannabinoid CB2 Receptors Suppresses Neuropathic Nociception Induced by Treatment with the Chemotherapeutic Agent Paclitaxel in Rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008, 327, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulpuri, Y.; Marty, V.N.; Munier, J.J.; Mackie, K.; Schmidt, B.L.; Seltzman, H.H.; Spigelman, I. Synthetic peripherally-restricted cannabinoid suppresses chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy pain symptoms by CB1 receptor activation. Neuropharmacology 2018, 139, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Galli, J., Andari Sawaya, R. and K Friedenberg, F., 2011. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. Current drug abuse reviews, 4(4), pp.241-249.

- Wallace, E.A., Andrews, S.E., Garmany, C.L. and Jelley, M.J., 2011. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: Literature review and proposed diagnosis and treatment algorithm. South Med J, 104(9), pp.659-664.

- Sorensen, C.J.; DeSanto, K.; Borgelt, L.; Phillips, K.T.; Monte, A.A. Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome: Diagnosis, Pathophysiology, and Treatment—a Systematic Review. J. Med Toxicol. 2016, 13, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, J.R.; Gordon, B.K.; Danielson, A.R.; Moulin, A.K. Pharmacologic Treatment of Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome: A Systematic Review. Pharmacother. J. Hum. Pharmacol. Drug Ther. 2017, 37, 725–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolson, S.E.; Denysenko, L.; Mulcare, J.L.; Vito, J.P.; Chabon, B. Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome: A Case Series and Review of Previous Reports. Psychosomatics 2012, 53, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapoint, J.; Meyer, S.; Yu, C.K.; Koenig, K.L.; Lev, R.; Thihalolipavan, S.; Staats, K.; Kahn, C.A. Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome: Public Health Implications and a Novel Model Treatment Guideline. WestJEM 21.2 March Issue 2018, 19, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, E.B.; Spooner, C.; May, L.; Leslie, R.; Whiteley, V.L. Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome Survey and Genomic Investigation. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2022, 7, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

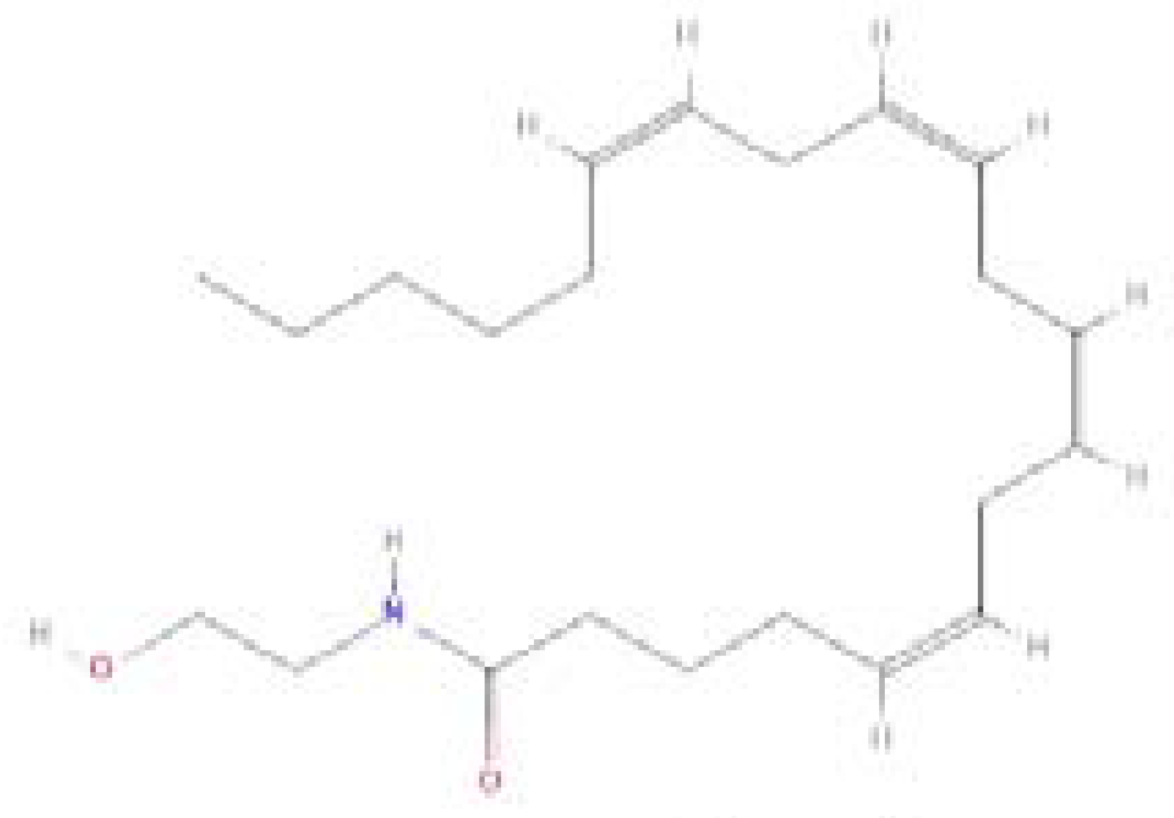

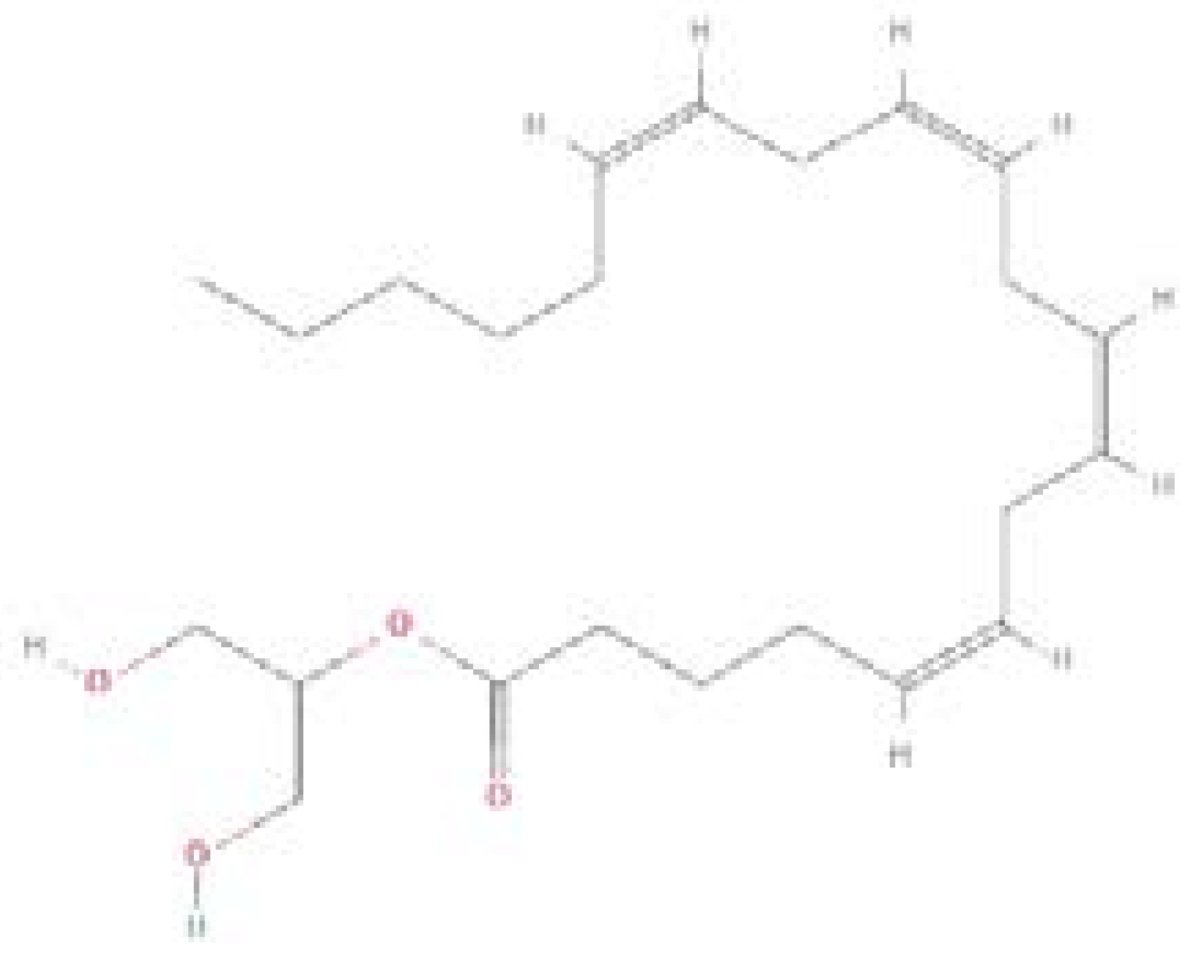

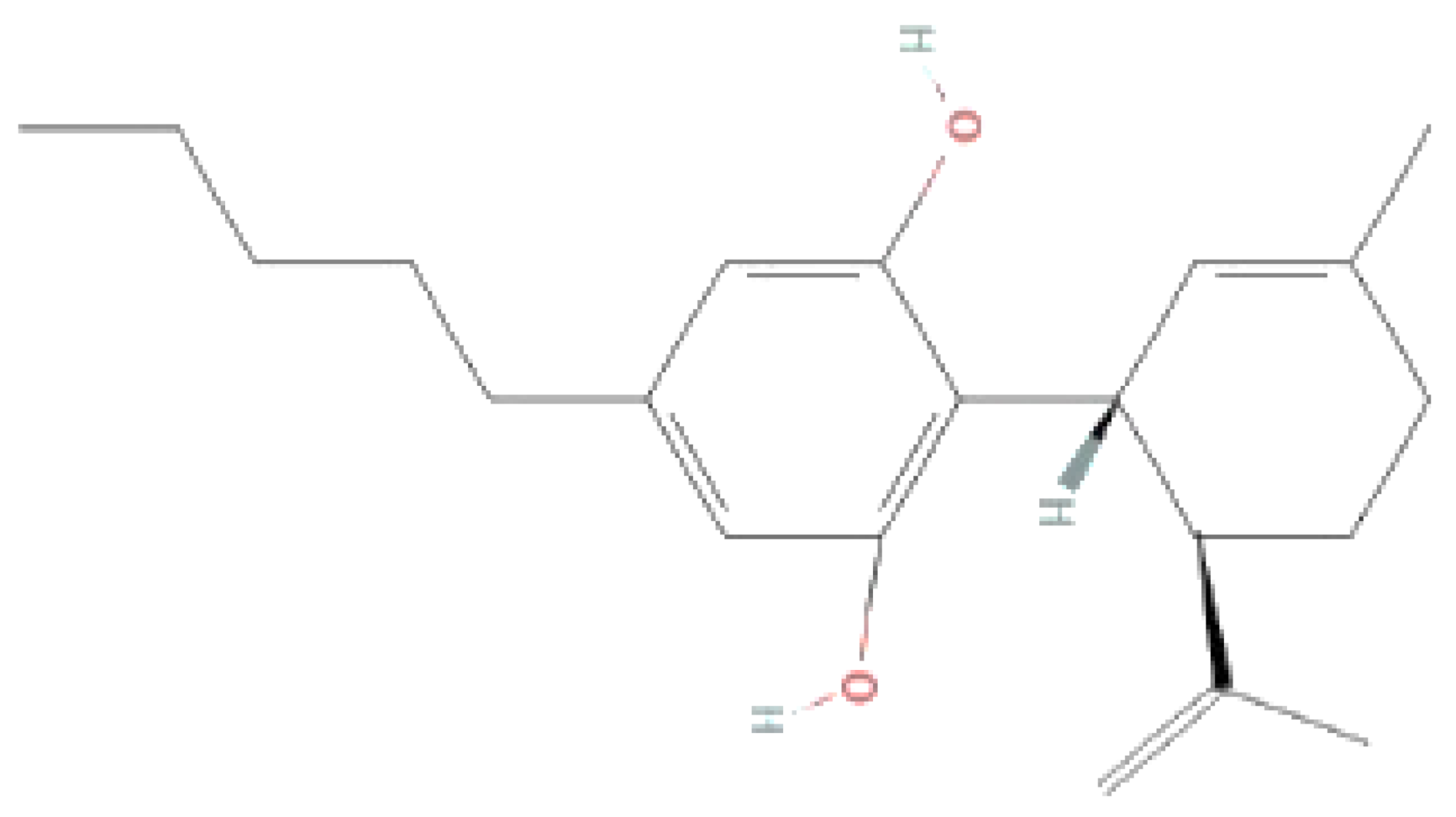

| Endocannabinoids/Phytocannabinoids | Structure | Molecular Formula | Molecular weight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anandamide amidohydrolase (AEA) |  |

C22H37NO2 | 347.5 g/mol |

| 2-Arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) |  |

C23H38O4 | 378.5 g/mol |

| Cannabinoid (CBD) |  |

C21H30O2 | 314.5 g/mol |

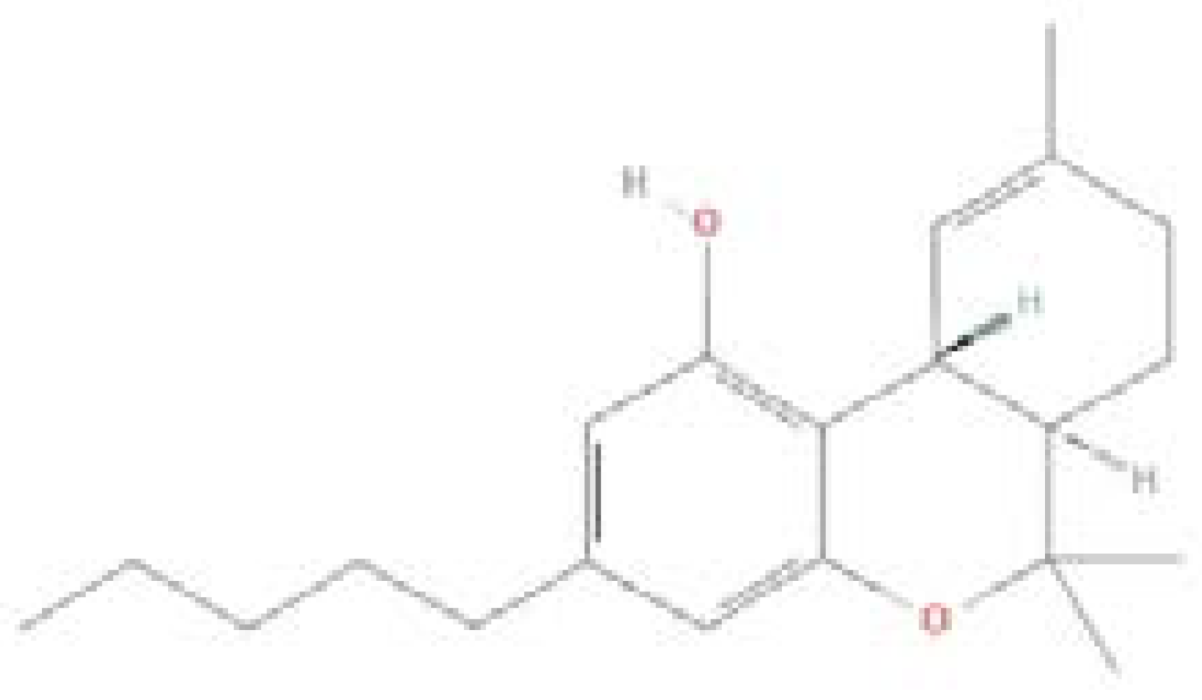

| Delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) |  |

C21H30O2 | 314.5 g/mol |

| Therapeutic Potential | Description | Specific Examples | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain Management (CB2) | CB2 modulation shows promise in alleviating various types of pain, particularly neuropathic pain, inflammatory pain, and chronic pain conditions. It may offer an alternative or adjunct to traditional analgesics, with potentially fewer side effects. | - Neuropathic pain relief#break#- Alleviation of inflammatory pain#break#-Management of chronic pain conditions | [115,116] |

| Inflammation (CB2) | CB2 receptors play a crucial role in regulating immune responses and inflammation. Modulating CB2 activity has been investigated for its therapeutic effects in inflammatory diseases such as arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and neuroinflammatory conditions. | - Reduction of arthritis symptoms#break#- Management of inflammatory bowel disease#break#- Attenuation of neuroinflammation | [110,111,113] |

| Neuroprotection (CB2) | Activation of CB2 receptors has been linked to neuroprotection in various neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and multiple sclerosis. CB2 modulation may help reduce neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, and neuronal damage, thereby slowing disease progression and preserving cognitive function. | - Protection against neuronal damage in Alzheimer’s disease #break#- Attenuation of neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s disease#break#- Preservation of cognitive function in multiple sclerosis | [117,118] |

| Mood Disorders (CB2) | CB2 modulation has shown potential in regulating mood and emotional responses, suggesting a role in the treatment of mood disorders such as anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Emerging research indicates that CB2 activation may exert anxiolytic and antidepressant effects through modulation of neurotransmitter systems and neuroinflammatory pathways. | - Reduction of anxiety symptoms#break#- Alleviation of depressive symptoms#break#- Improvement in PTSD symptoms | [119,120] |

| Cancer (CB2) | CB2 receptors are overexpressed in certain cancer types, and their modulation has been explored for anticancer effects. Preclinical studies suggest that CB2 activation inhibits tumor growth, metastasis, and angiogenesis, while inducing apoptosis in cancer cells. CB2 agonists may also enhance the efficacy of chemotherapy and radiation therapy, offering potential synergistic effects in cancer treatment. | - Inhibition of tumor growth and metastasis#break#- Induction of cancer cell apoptosis#break#- Enhancement of chemotherapy efficacy | [121,122] |

| Metabolic Disorders (CB2) | CB2 activation has been implicated in regulating metabolic processes such as appetite, energy balance, and glucose metabolism. Modulating CB2 activity may hold therapeutic potential in metabolic disorders like obesity, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome. CB2 agonists have been shown to reduce food intake, body weight, and adiposity, as well as improve insulin sensitivity and lipid profiles in preclinical models. | - Reduction of food intake and body weight#break#- Improvement of insulin sensitivity#break#- Regulation of lipid metabolism | [123,124] |

| Cardiovascular Health (CB2) | Modulation of CB2 receptors may have protective effects on the cardiovascular system. CB2 activation has been associated with reduced inflammation, oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction, and atherosclerotic plaque formation, suggesting potential therapeutic benefits for cardiovascular diseases such as atherosclerosis, hypertension, and myocardial infarction. | - Reduction of inflammation and oxidative stress in atherosclerosis#break#- Improvement of endothelial function#break#- Prevention of atherosclerotic plaque formation | [125,126] |

| Pain Management (CB1) | CB1 receptors are involved in the modulation of pain perception, particularly in the central nervous system. Activation of CB1 receptors can suppress pain signaling pathways, offering potential therapeutic benefits in the management of acute and chronic pain conditions. | - Suppression of pain signaling pathways in the CNS | [115,127] |

| Neuroprotection (CB1) | CB1 receptor activation has been associated with neuroprotective effects in various neurological conditions, including epilepsy, ischemic stroke, and traumatic brain injury. CB1 modulation may help mitigate neuronal damage, excitotoxicity, and neuroinflammation, thereby preserving neuronal integrity and function. | - Protection against neuronal damage in epilepsy#break#- Attenuation of neuroinflammation in stroke#break#- Preservation of neuronal function in traumatic brain injury | [120,121] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).