Submitted:

24 January 2025

Posted:

24 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

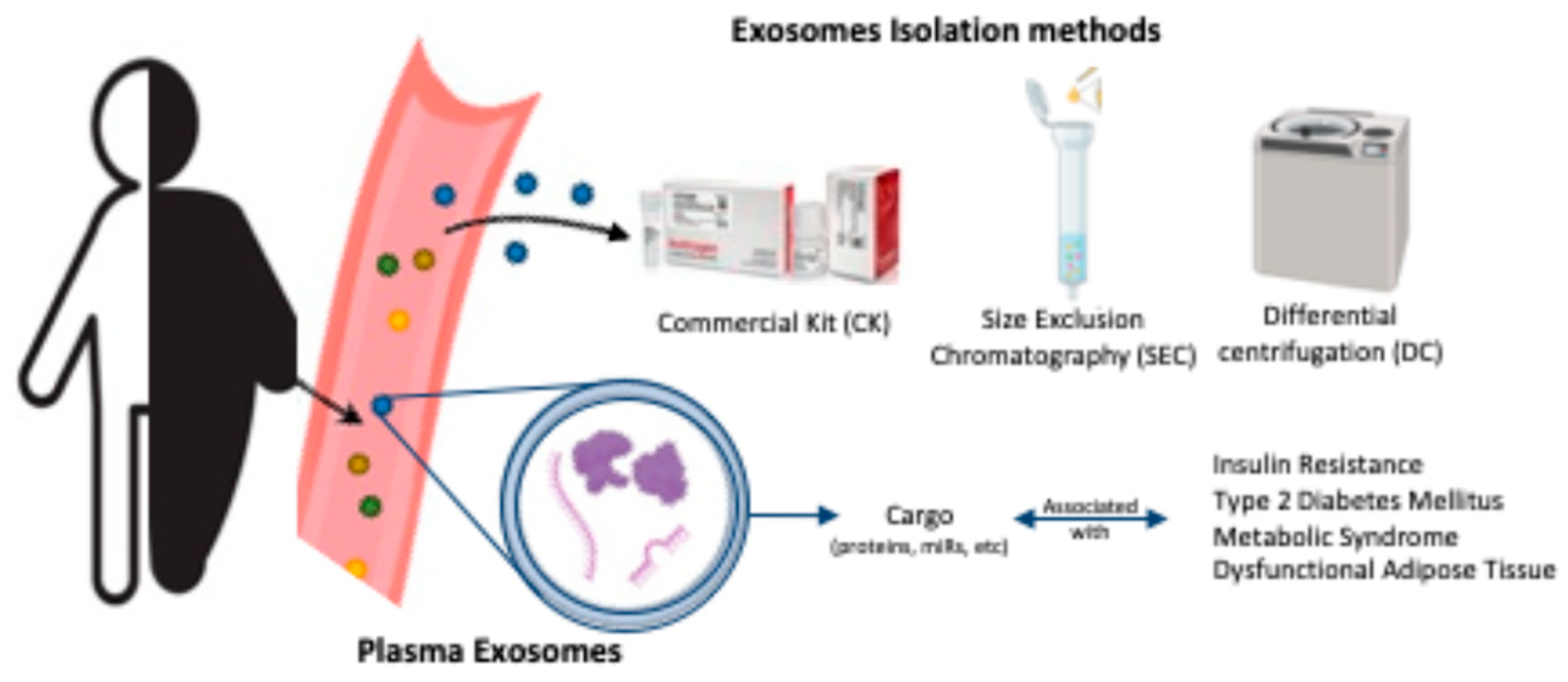

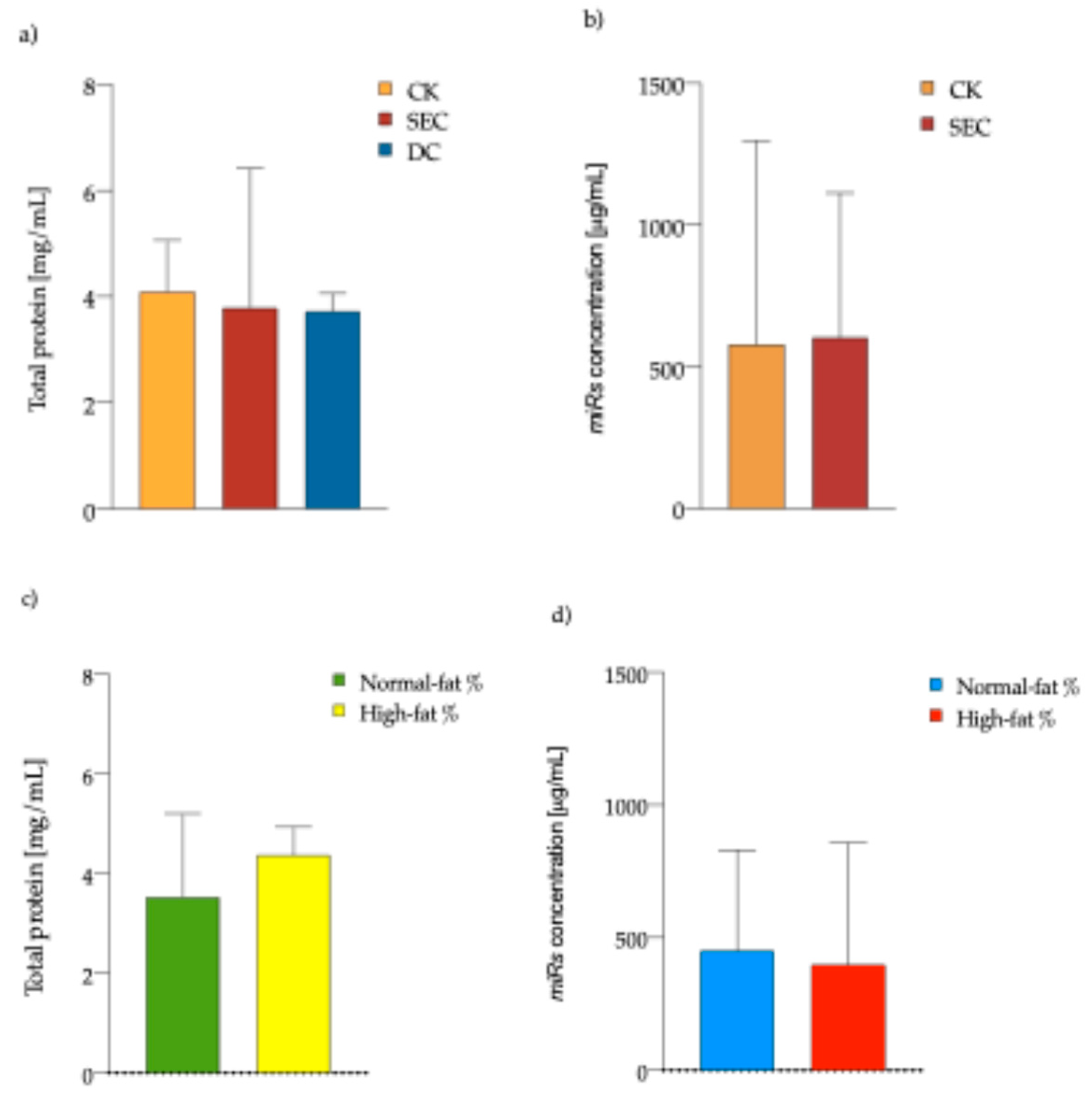

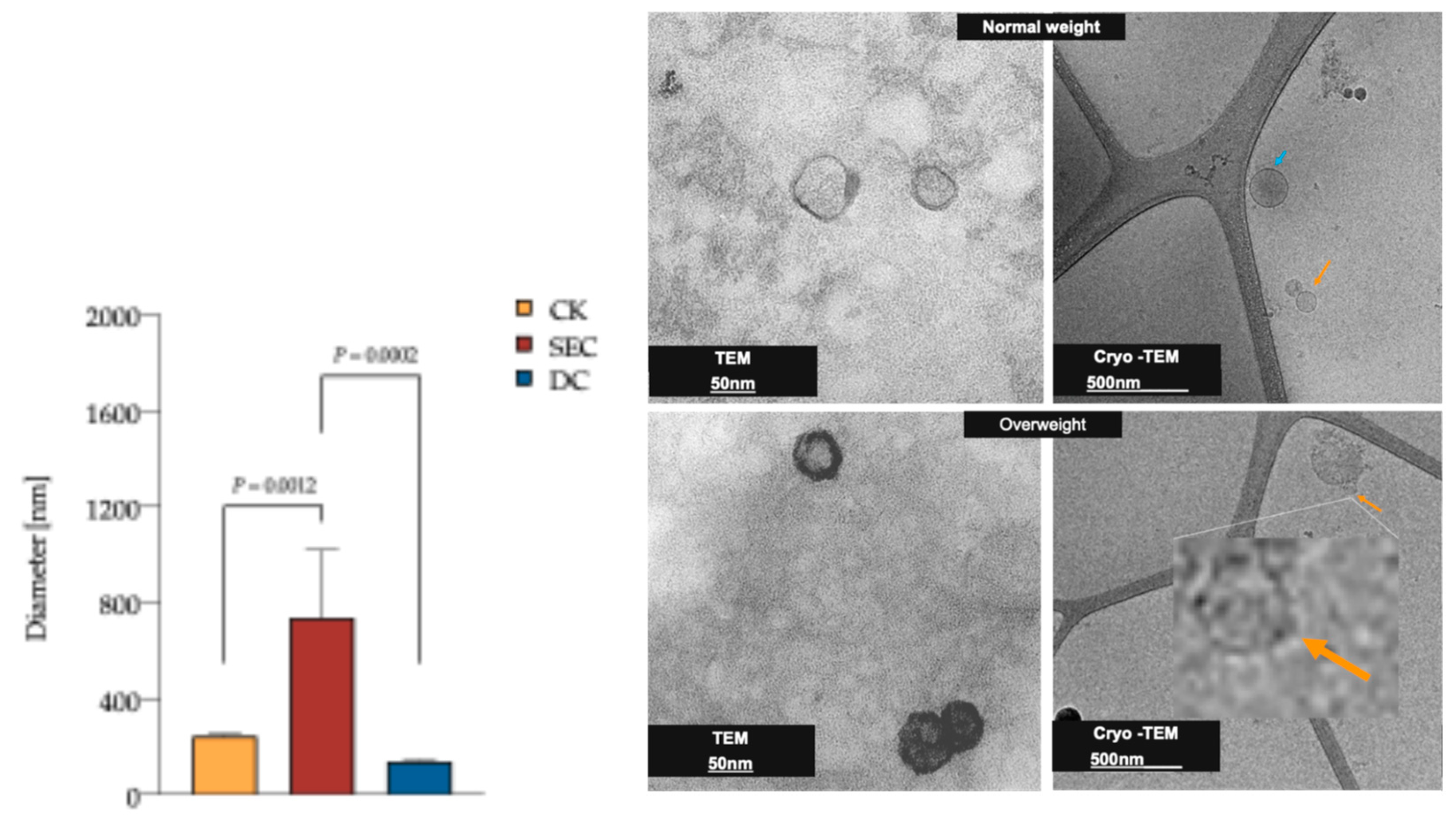

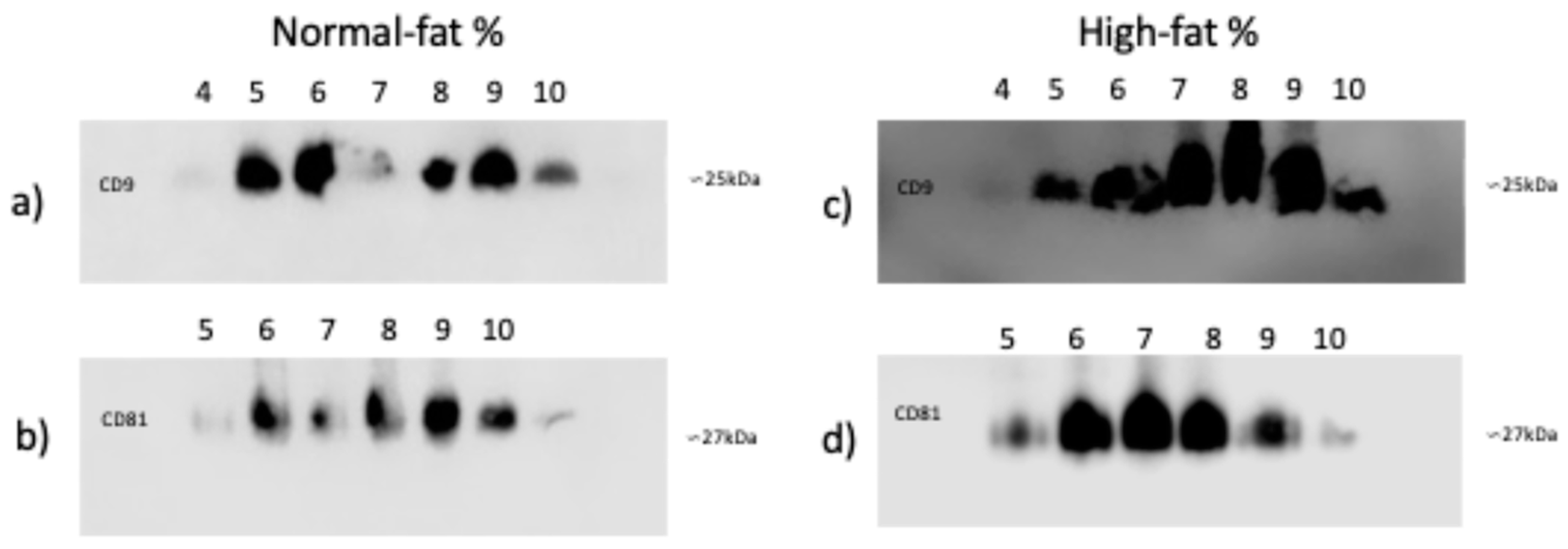

The adipose tissue is responsible for fat storage and is an important producer of extracellular vesicles (EVs). The biological content of exosomes, one kind of EVs, provides information such as immunometabolic alterations. This study aimed to compare three plasma exosome isolation methods and select the best. Plasma from 118 individuals, categorized by normal and high body fat percentage, and developing a 3T3-L1 cell line as an obesogenic model through continuous glucose exposure and a prolonged hypoxic microenvironment, were used. We perform three exo-some isolation methods: commercial kit (CK), size exclusion chromatography (SEC), and differ-ential centrifugation (DC), and characterized by DLS, cryo-TEM, TEM, and western blot CD9 and CD81 markers. In the DLS, cryo-TEM, and TEM analysis showed similar quality and mor-phology of exosomes. The CK and DC proved to comply with most of the advantages of an exo-some isolation method. Still, we emphasize the importance of selecting the appropriate method-ology depending on the specific research objectives. At the same time, no differences in exosome morphology, total protein, nor microRNAs concentration were observed between individuals categorized by body fat percentage, so we suggest that exosome cargo is the one that varies in in-dividuals with normal and high-fat percentages.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples

2.1.1. Plasma Sample

2.1.2. Cell Culture

2.2. Exosome Isolation and Characterization

2.2.1. Isolation by Differential Centrifugation (DC)

2.2.2. Isolation by Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC)

2.2.3. Isolation by Commercial KIT (CK)

2.2.4. Characterization by Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

2.2.5. Characterization by Cryo-TEM and TEM

2.2.6. Characterization by Western Blot

2.4. Statistical and Image Analyses

3. Results

3.1. The Exosome Isolation Methods Showed Equal Performance in Total Protein and microRNA Concentration, While an Inverse Pattern Is Observed Among Individuals with High-Fat Mass Content

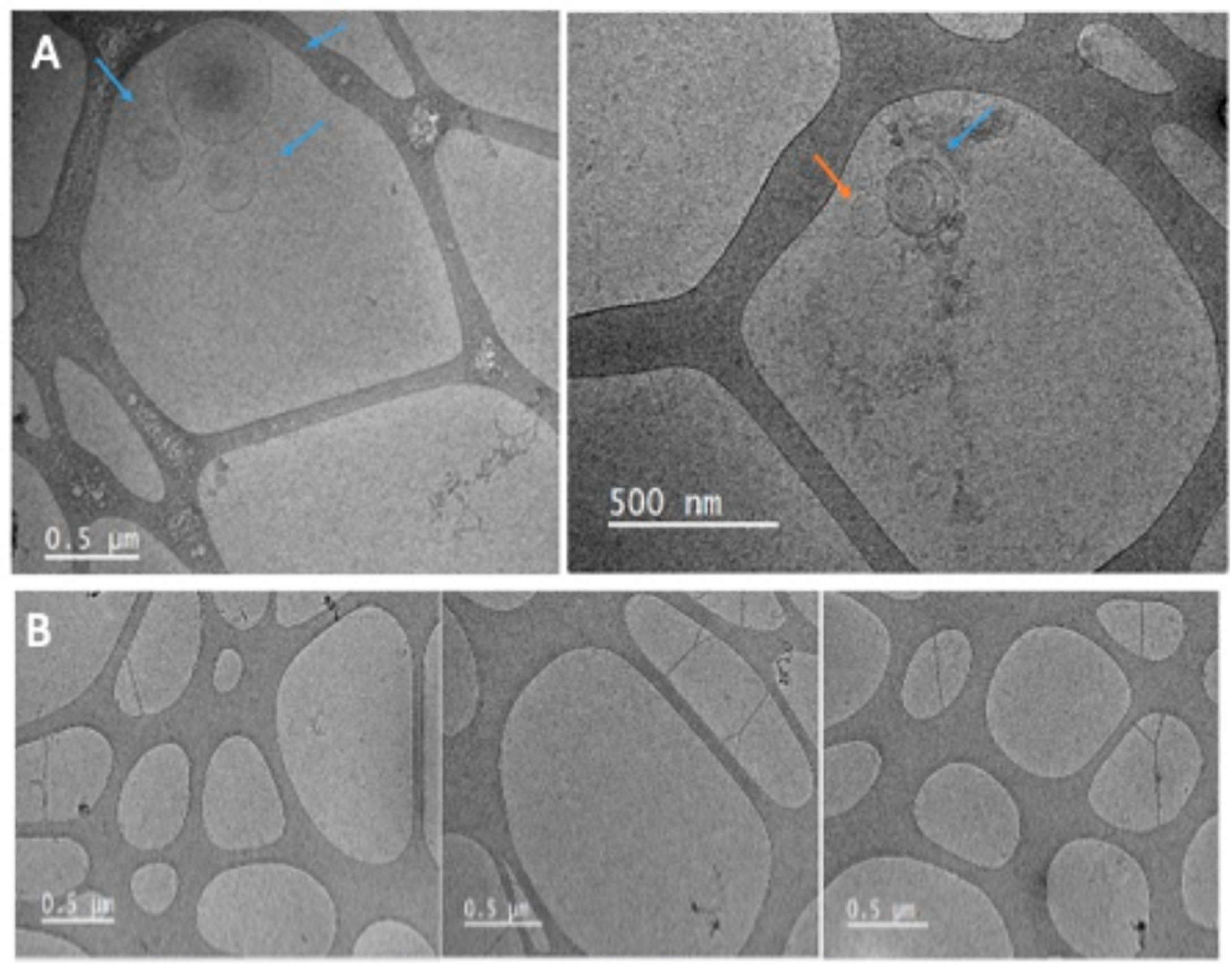

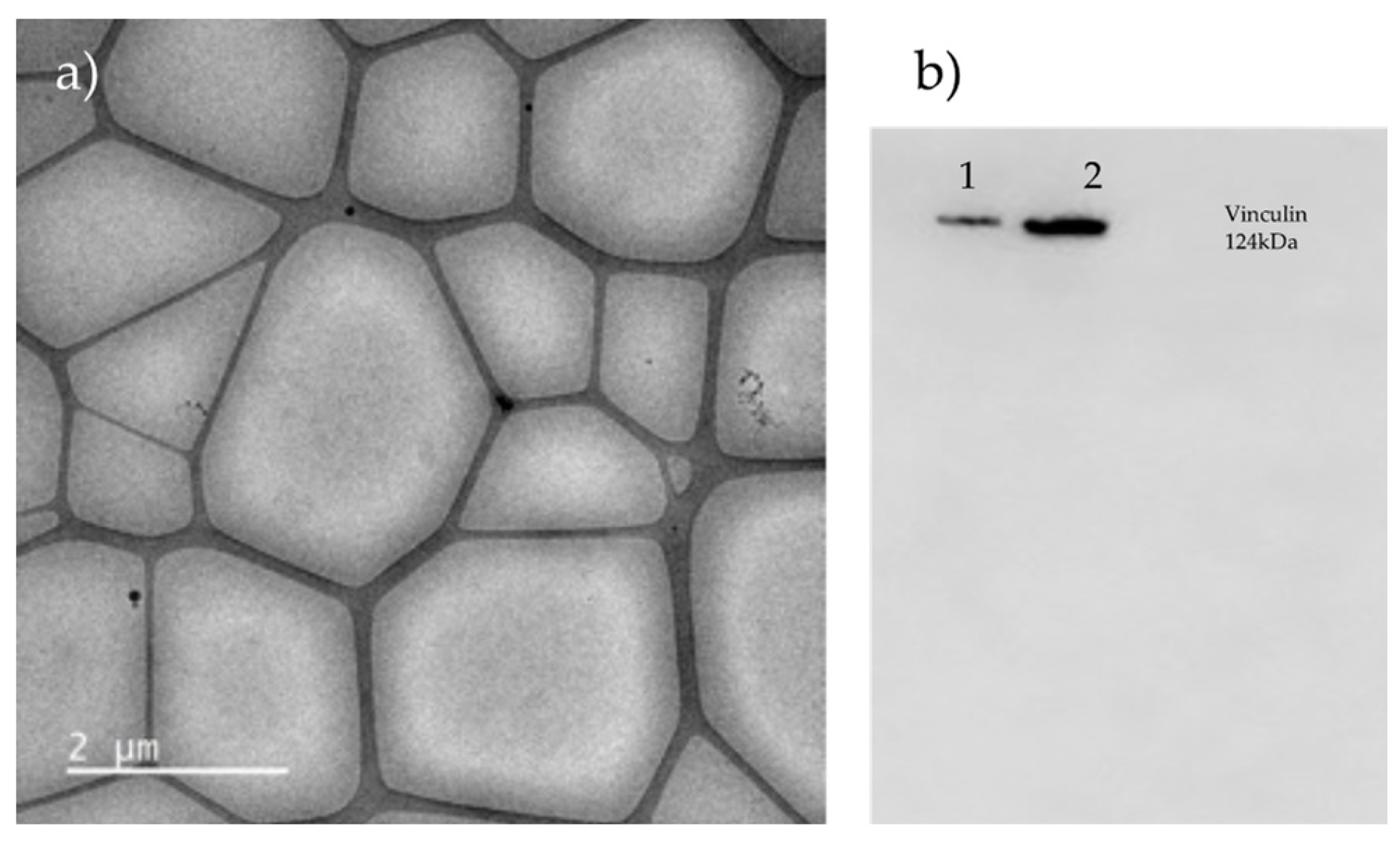

3.2. The Morphology and Quality of the Three Exosome Isolation Methods Were as Expected, with Inconsistencies in Purity

3.3. CD9 and CD81 Do Not Differ Between Normal and High-Fat Percentage Individuals in SEC Fractions

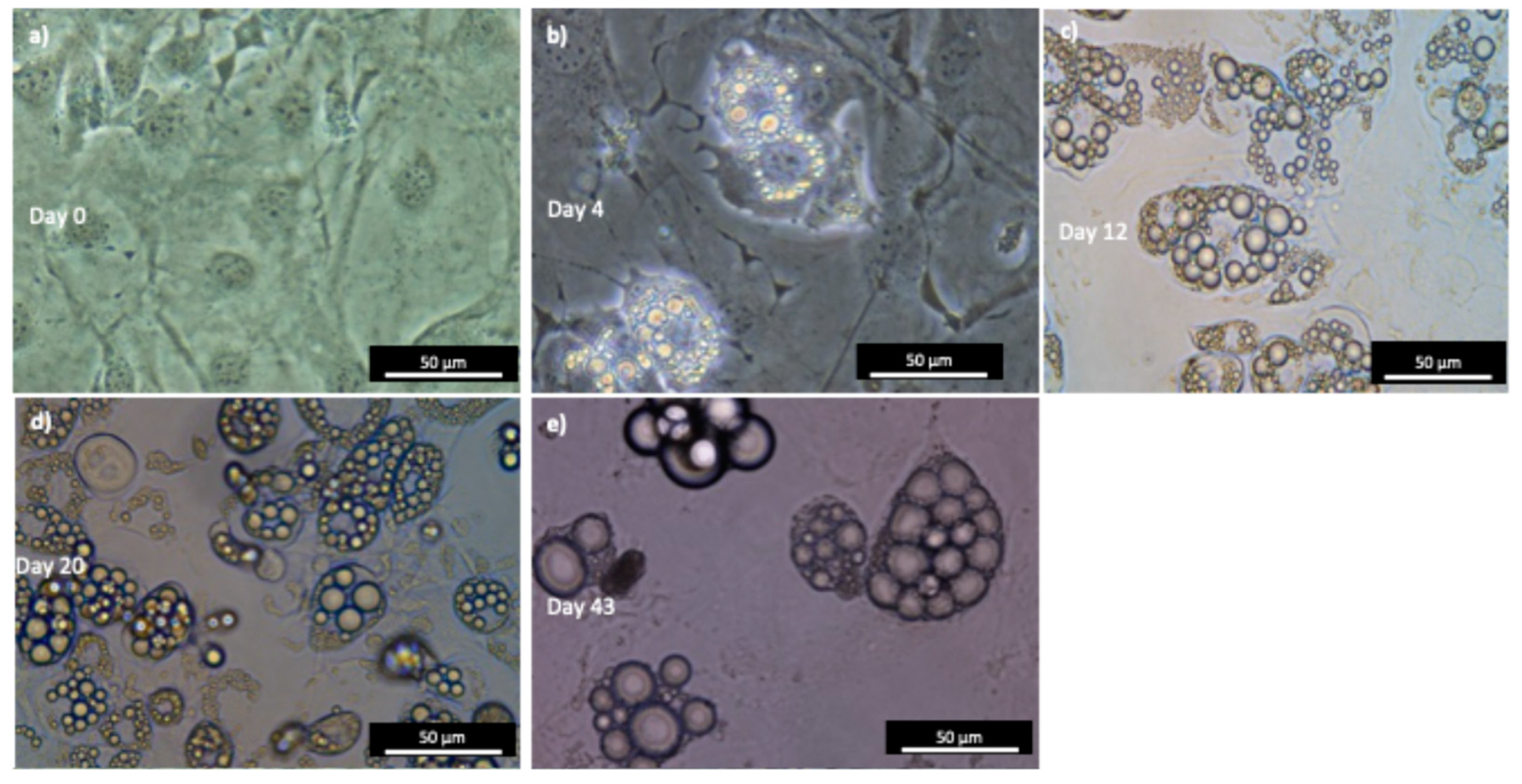

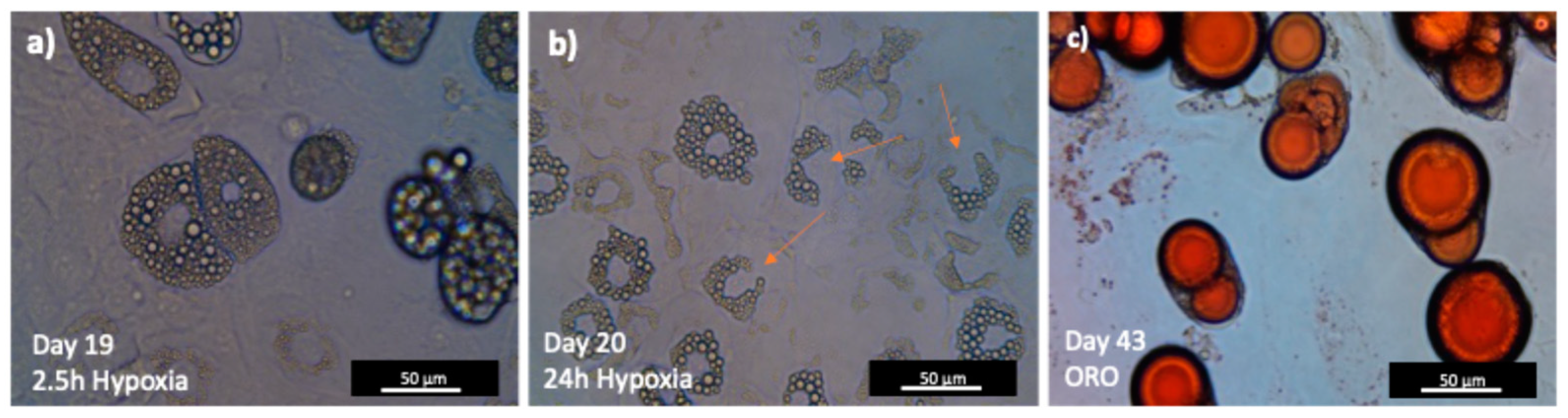

3.4. The Successful Differentiation of 3T3-L1 Cells Results in Acquiring a Mature Adipocyte Phenotype

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Thery C, Amigorena S, Raposo G, Clayton A: Isolation and characterization of exosomes from cell culture supernatants and biological fluids. Curr Protoc Cell Biol 2006, Chapter 3:Unit 3 22.

- Abdulmalek O, Husain K, AlKhalifa H, Alturani M, Butler A, Moin A: Therapeutic Applications of Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25:3562.

- Welsh JA, Goberdhan DCI, O'Driscoll L, Buzas EI, Blenkiron C, Bussolati B, Cai H, Di Vizio D, Driedonks TAP, Erdbrugger U, et al.: Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles (MISEV2023): From basic to advanced approaches. J Extracell Vesicles 2024, 13:e12404. [CrossRef]

- Lei LM, Lin X, Xu F, Shan SK, Guo B, Li FX, Zheng MH, Wang Y, Xu QS, Yuan LQ: Exosomes and Obesity-Related Insulin Resistance. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9:651996.

- Dance A: The body’s tiny cargo carriers. In Knowable magazine. Edited by; 2019.

- Jiang X, You L, Zhang Z, Cui X, Zhong H, Sun X, Ji C, Chi X: Biological Properties of Milk-Derived Extracellular Vesicles and Their Physiological Functions in Infant. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2021, 9.

- Ragusa M, Barbagallo C, Statello L, Caltabiano R, Russo A, Puzzo L, Avitabile T, Longo A, Toro MD, Barbagallo D, et al.: miRNA profiling in vitreous humor, vitreal exosomes and serum from uveal melanoma patients: Pathological and diagnostic implications. Cancer Biol Ther 2015, 16:1387-1396. [CrossRef]

- Jan AT, Rahman S, Badierah R, Lee EJ, Mattar EH, Redwan EM, Choi I: Expedition into Exosome Biology: A Perspective of Progress from Discovery to Therapeutic Development. Cancers 2021, 13.

- Mei R, Qin W, Zheng Y, Wan Z, Liu L: Role of Adipose Tissue Derived Exosomes in Metabolic Disease. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2022, 13.

- Liu Y, Wang C, Wei M, Yang G, Yuan L: Multifaceted Roles of Adipose Tissue-Derived Exosomes in Physiological and Pathological Conditions. Front Physiol 2021, 12:669429.

- Ji C, Guo X: The clinical potential of circulating microRNAs in obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2019, 15:731-743.

- Bond ST, Calkin AC, Drew BG: Adipose-Derived Extracellular Vesicles: Systemic Messengers and Metabolic Regulators in Health and Disease. Front Physiol 2022, 13:837001.

- Camino T, Lago-Baameiro N, Pardo M: Extracellular Vesicles as Carriers of Adipokines and Their Role in Obesity. Biomedicines 2023, 11:422.

- Fasshauer M, Bluher M: Adipokines in health and disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2015, 36:461-470.

- Zhao R, Zhao T, He Z, Cai R, Pang W: Composition, isolation, identification and function of adipose tissue-derived exosomes. Adipocyte 2021, 10:587-604. [CrossRef]

- Yang XX, Sun C, Wang L, Guo XL: New insight into isolation, identification techniques and medical applications of exosomes. Journal of Controlled Release 2019, 308:119-129.

- Muller L, Hong CS, Stolz DB, Watkins SC, Whiteside TL: Isolation of biologically-active exosomes from human plasma. J Immunol Methods 2014, 411:55-65.

- Cheng Y, Qu X, Dong Z, Zeng Q, Ma X, Jia Y, Li R, Jiang X, Williams C, Wang T, et al.: Comparison of serum exosome isolation methods on co-precipitated free microRNAs. PeerJ 2020, 8:e9434. [CrossRef]

- Chen J, Li P, Zhang T, Xu Z, Huang X, Wang R, Du L: Review on Strategies and Technologies for Exosome Isolation and Purification. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2021, 9:811971.

- Rech J, Getinger-Panek A, Gałka S, Bednarek I: Origin and Composition of Exosomes as Crucial Factors in Designing Drug Delivery Systems. Applied Sciences 2022, 12:12259.

- Koritzinsky EH, Street JM, Star RA, Yuen PS: Quantification of Exosomes. J Cell Physiol 2017, 232:1587-1590.

- Whitehead C, Luwor R, Morokoff A, Kaye A, Stylli S: Cancer exosomes in cerebrospinal fluid. Translational Cancer Research 2017, 6.

- Deng FY, Miller J: A review on protein markers of exosome from different bio-resources and the antibodies used for characterization. Journal of Histotechnology 2019, 42:226-239.

- Chernyshev VS, Rachamadugu R, Tseng YH, Belnap DM, Jia Y, Branch KJ, Butterfield AE, Pease LF, 3rd, Bernard PS, Skliar M: Size and shape characterization of hydrated and desiccated exosomes. Anal Bioanal Chem 2015, 407:3285-3301.

- Li D, Luo H, Ruan H, Chen Z, Chen S, Wang B, Xie Y: Isolation and identification of exosomes from feline plasma, urine and adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells. BMC Vet Res 2021, 17:272.

- Welsh JA, Goberdhan DCI, O'Driscoll L, Buzas EI, Blenkiron C, Bussolati B, Cai H, Di Vizio D, Driedonks TAP, Erdbrügger U, et al.: Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles (MISEV2023): From basic to advanced approaches. Journal of Extracellular Vesicles 2024, 13:e12404. [CrossRef]

- Etesami B, Ghaseminezhad S, Nowrouzi A, Rashidipour M, Yazdanparast R: Investigation of 3T3-L1 Cell Differentiation to Adipocyte, Affected by Aqueous Seed Extract of Phoenix Dactylifera L. Rep Biochem Mol Biol 2020, 9:14-25.

- Lobb RJ, Becker M, Wen SW, Wong CS, Wiegmans AP, Leimgruber A, Moller A: Optimized exosome isolation protocol for cell culture supernatant and human plasma. J Extracell Vesicles 2015, 4:27031.

- Paolo Fortina EL, Jason Y. Park, Larry J. Kricka: Acute Myeloid Leukemia - Methods and Protocols. In Springer Protocols. Edited by; 2017:258 - 266. vol Methods in Molecular Biology 1633.].

- Federation WO: World Obesity Atlas 2024. In World Obesity Federation. Edited by; 2024. vol 2024.].

- Zhou C, Huang YQ, Da MX, Jin WL, Zhou FH: Adipocyte-derived extracellular vesicles: bridging the communications between obesity and tumor microenvironment. Discov Oncol 2023, 14:92.

- Delgadillo-Velázquez J, Alday E, Aguirre-García MM, Canett-Romero R, Astiazaran-Garcia H: The association between the size of adipocyte-derived extracellular vesicles and fasting serum triglyceride-glucose index as proxy measures of adipose tissue insulin resistance in a rat model of early-stage obesity. Frontiers in Nutrition 2024, 11.

- Coughlan C, Bruce KD, Burgy O, Boyd TD, Michel CR, Garcia-Perez JE, Adame V, Anton P, Bettcher BM, Chial HJ, et al.: Exosome Isolation by Ultracentrifugation and Precipitation and Techniques for Downstream Analyses. Curr Protoc Cell Biol 2020, 88:e110. [CrossRef]

- Tang YT, Huang YY, Zheng L, Qin SH, Xu XP, An TX, Xu Y, Wu YS, Hu XM, Ping BH, et al.: Comparison of isolation methods of exosomes and exosomal RNA from cell culture medium and serum. Int J Mol Med 2017, 40:834-844. [CrossRef]

- Caradec J, Kharmate G, Hosseini-Beheshti E, Adomat H, Gleave M, Guns E: Reproducibility and efficiency of serum-derived exosome extraction methods. Clin Biochem 2014, 47:1286-1292.

- Aziz MA, Seo B, Hussaini HM, Hibma M, Rich AM: Comparing Two Methods for the Isolation of Exosomes. J Nucleic Acids 2022, 2022:8648373.

- Wang Y, Wu Y, Yang S, Chen Y: Comparison of Plasma Exosome Proteomes Between Obese and Non-Obese Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 2023, 16:629-642.

- Kwan HY, Chen M, Xu K, Chen B: The impact of obesity on adipocyte-derived extracellular vesicles. Cell Mol Life Sci 2021.

- Son T, Jeong I, Park J, Jun W, Kim A, Kim O-K: Adipose tissue-derived exosomes contribute to obesity-associated liver diseases in long-term high-fat diet-fed mice, but not in short-term. Frontiers in Nutrition 2023, 10.

- Lai JJ, Chau ZL, Chen SY, Hill JJ, Korpany KV, Liang NW, Lin LH, Lin YH, Liu JK, Liu YC, et al.: Exosome Processing and Characterization Approaches for Research and Technology Development. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2022, 9:e2103222. [CrossRef]

- Dilsiz N: A comprehensive review on recent advances in exosome isolation and characterization: Toward clinical applications. Transl Oncol 2024, 50:102121.

- Davidson SM, Boulanger CM, Aikawa E, Badimon L, Barile L, Binder CJ, Brisson A, Buzas E, Emanueli C, Jansen F, et al.: Methods for the identification and characterization of extracellular vesicles in cardiovascular studies: from exosomes to microvesicles. Cardiovasc Res 2023, 119:45-63. [CrossRef]

- Sakha S, Muramatsu T, Ueda K, Inazawa J: Exosomal microRNA miR-1246 induces cell motility and invasion through the regulation of DENND2D in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Sci Rep 2016, 6:38750.

- Akbar N, Pinnick KE, Paget D, Choudhury RP: Isolation and Characterization of Human Adipocyte-Derived Extracellular Vesicles using Filtration and Ultracentrifugation. J Vis Exp 2021.

- Sharif S, Mozaffari-Jovin S, Alizadeh F, Mojarrad M, Baharvand H, Nouri M, Abbaszadegan MR: Isolation of plasma small extracellular vesicles by an optimized size-exclusion chromatography-based method for clinical applications. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2023, 87:104796.

- Lee MJ, Wu Y, Fried SK: A modified protocol to maximize differentiation of human preadipocytes and improve metabolic phenotypes. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012, 20:2334-2340.

- Jackson HC, Pheiffer C, Jack B, Africander D: Time- and glucose-dependent differentiation of 3T3-L1 adipocytes mimics dysfunctional adiposity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2023, 671:286-291.

- Vogler M, Vogel S, Krull S, Farhat K, Leisering P, Lutz S, Wuertz CM, Katschinski DM, Zieseniss A: Hypoxia modulates fibroblastic architecture, adhesion and migration: a role for HIF-1alpha in cofilin regulation and cytoplasmic actin distribution. PLoS One 2013, 8:e69128.

- Synowiec A, Brodaczewska K, Wcisło G, Majewska A, Borkowska A, Filipiak-Duliban A, Gawrylak A, Wilkus K, Piwocka K, Kominek A, et al.: Hypoxia, but Not Normoxia, Reduces Effects of Resveratrol on Cisplatin Treatment in A2780 Ovarian Cancer Cells: A Challenge for Resveratrol Use in Anticancer Adjuvant Cisplatin Therapy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24:5715. [CrossRef]

- Gesmundo I, Pardini B, Gargantini E, Gamba G, Birolo G, Fanciulli A, Banfi D, Congiusta N, Favaro E, Deregibus MC, et al.: Adipocyte-derived extracellular vesicles regulate survival and function of pancreatic beta cells. JCI Insight 2021, 6.

- Nakatani E, Naito Y, Ishibashi K, Ohkura N, Atsumi GI: Extracellular Vesicles Derived from 3T3-L1 Adipocytes Enhance Procoagulant Activity. Biol Pharm Bull 2022, 45:178-183.

- Sidhom K, Obi PO, Saleem A: A Review of Exosomal Isolation Methods: Is Size Exclusion Chromatography the Best Option? International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21:6466.

| Isolation Method | Advantage | Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|

| Commercial Kit (CK) | Fast procedure Many samples at the same time (centrifugation rotor tubes capacity) No expensive or complicated equipment Easy technique High yield Exosome integrity is maintained |

Relative economic Kit stability No high purity (for further proteomic analysis) |

| Size exclusion chromatography (SEC) | Economical material Non-destructive High yield Exosome integrity is maintained |

More time-consuming procedure Limit the sample’s quantity to work at the same time |

| Differential centrifugation (DC) | Purity (exosome size) Many samples at the same time (ultracentrifugation rotor tube capacity) High yield |

More time-consuming procedure Expensive equipment Pressure damages the exosome's integrity Induce aggregation of exosome |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).