Submitted:

07 May 2024

Posted:

10 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Highlights:

- Advancements in computational methods in in silico drug discovery have become a viable option.

- Artificial intelligence and machine learning improve in silico drug discovery by swiftly analyzing data, predicting interactions, and optimizing candidates with precision.

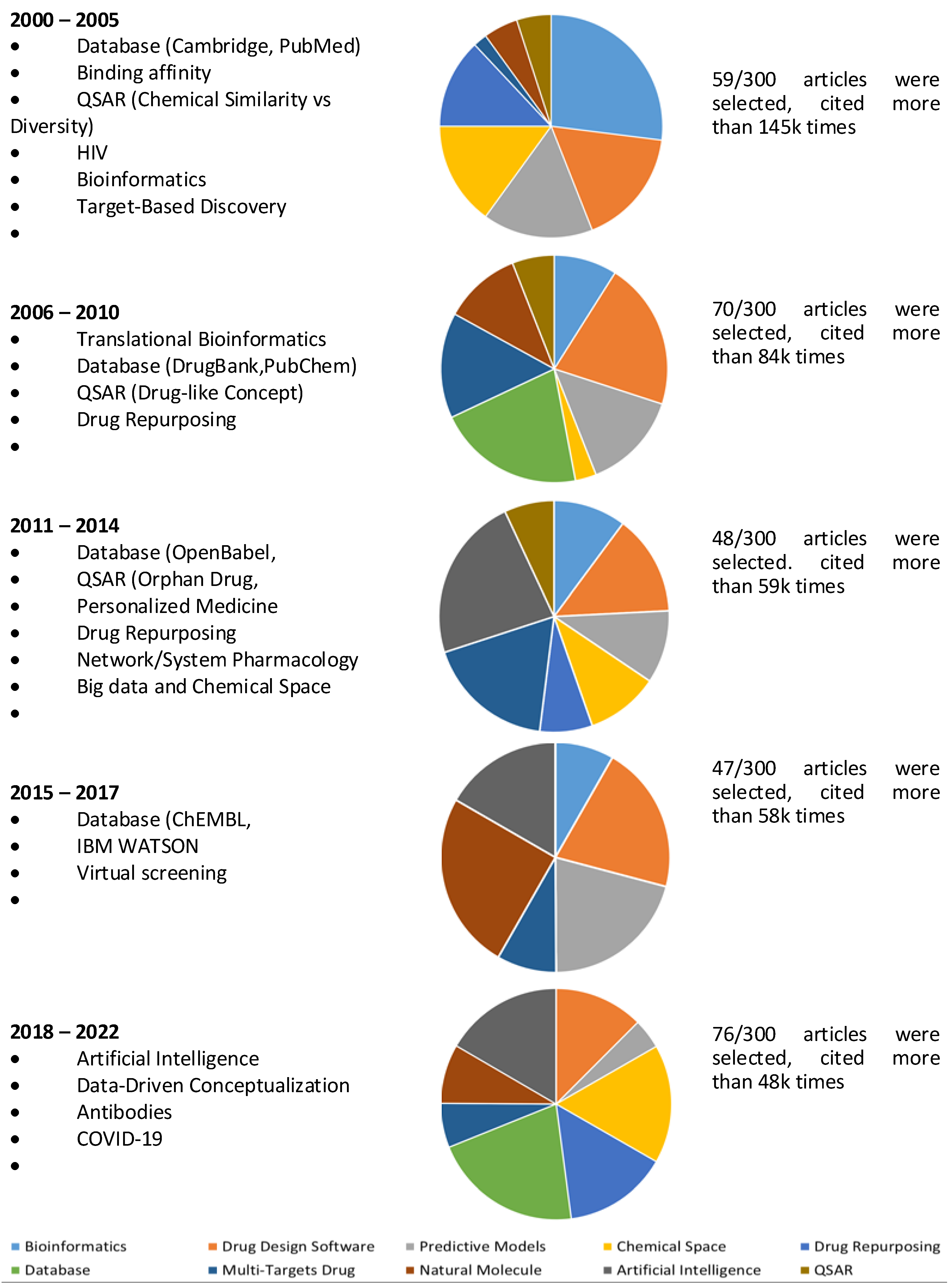

- The recent technological evolution from 1980 to 2024 of in silico methods is discussed.

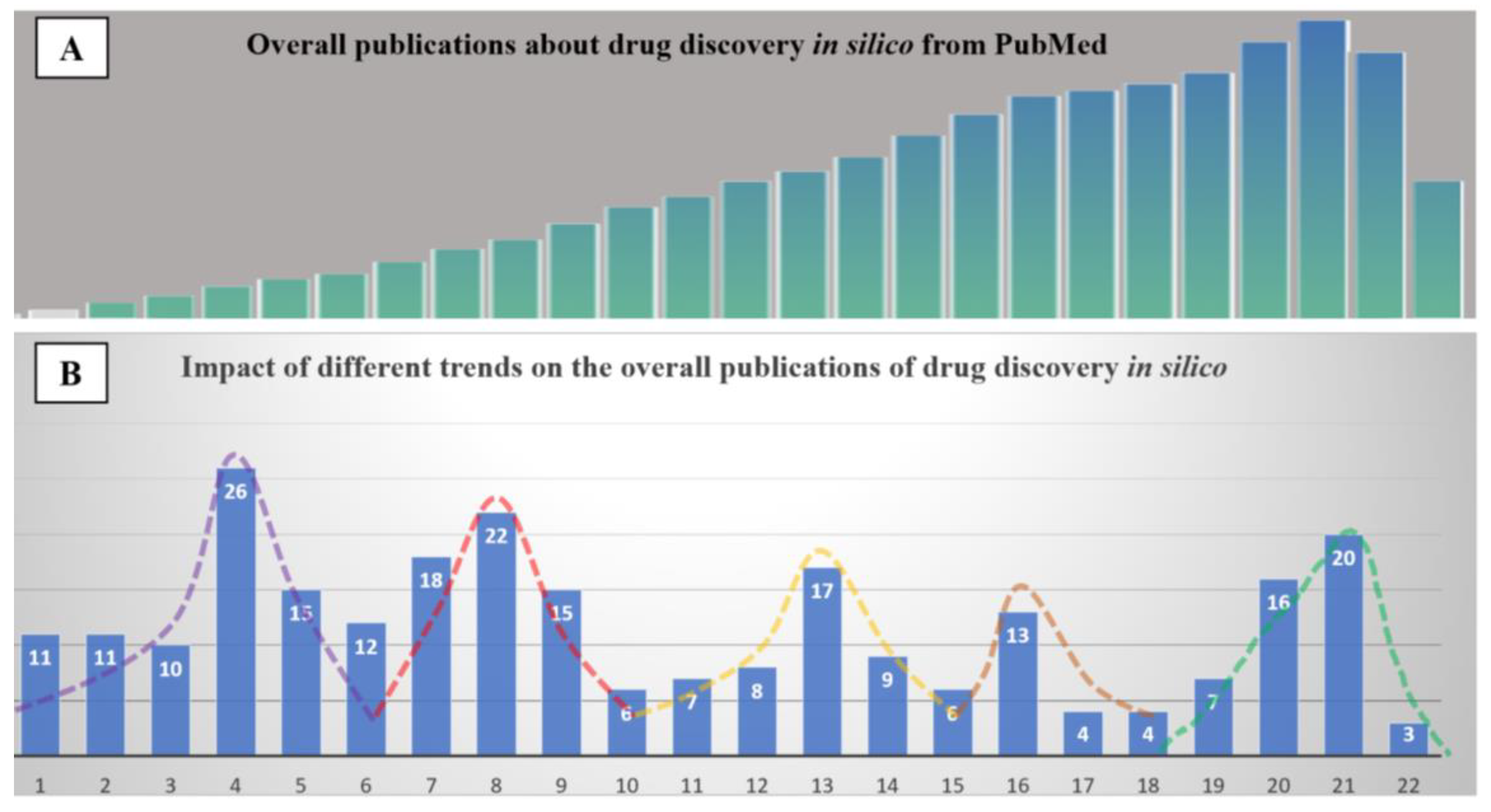

- We observed rising trends from big data to chemical space.

- An executive summary is structured according to the most cited articles.

- Milestones are assessed based on their respective timelines.

Executive Summary

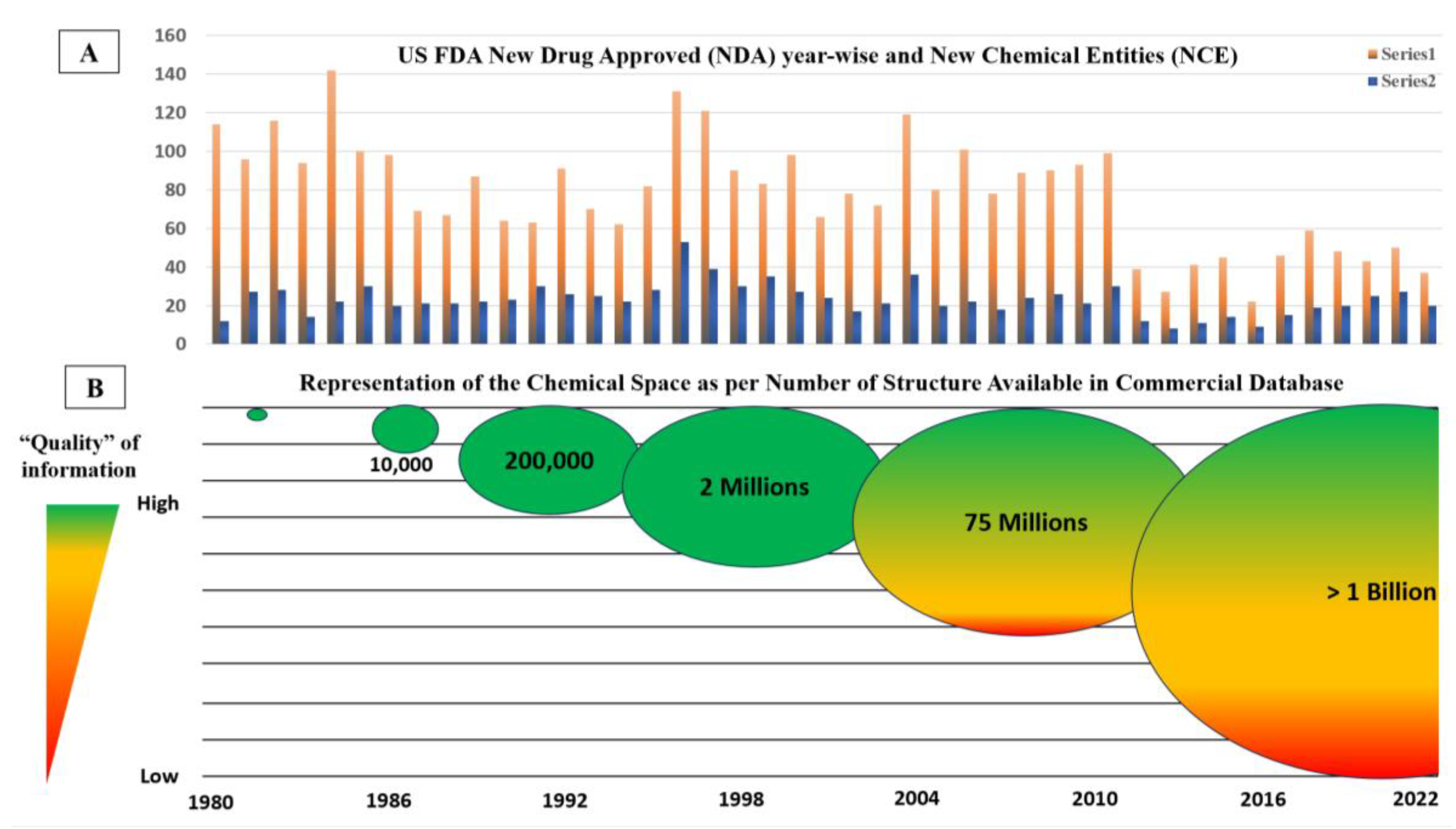

| Definition | Drug discovery is a multidisciplinary science mainly devoted to bringing new chemical entities (NCEs) to the market for already-known medical applications. However, this process is very time-consuming (10-12 years) and highly cost-sensitive (in the range of US $ billions). As a result, scientists have developed computational strategies to maximize the results and yield better and larger product portfolios using less time and less money. These computational strategies are referred to in silico methods (as well as computer-assisted methods) in the literature.

Integrating AI, data science, and machine learning into drug discovery streamlines processes, accelerating timelines and optimizing resource allocation. These technologies analyze vast datasets, predict drug efficacy and safety, and enhance accuracy by integrating diverse information sources. This synergy has the potential to revolutionize pharmaceuticals, making drug discovery faster, cost-effective, and more successful in delivering therapeutics to patients. |

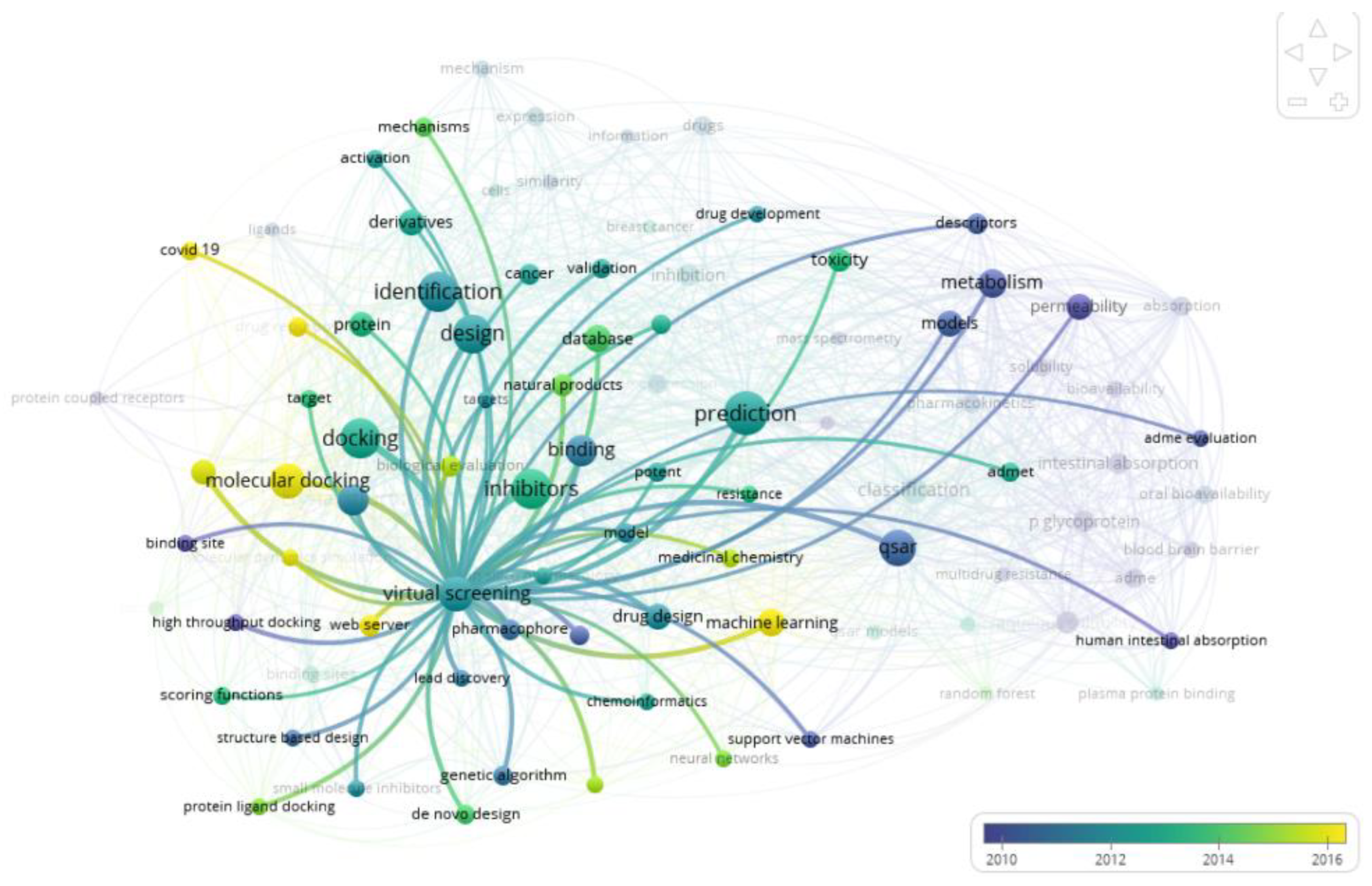

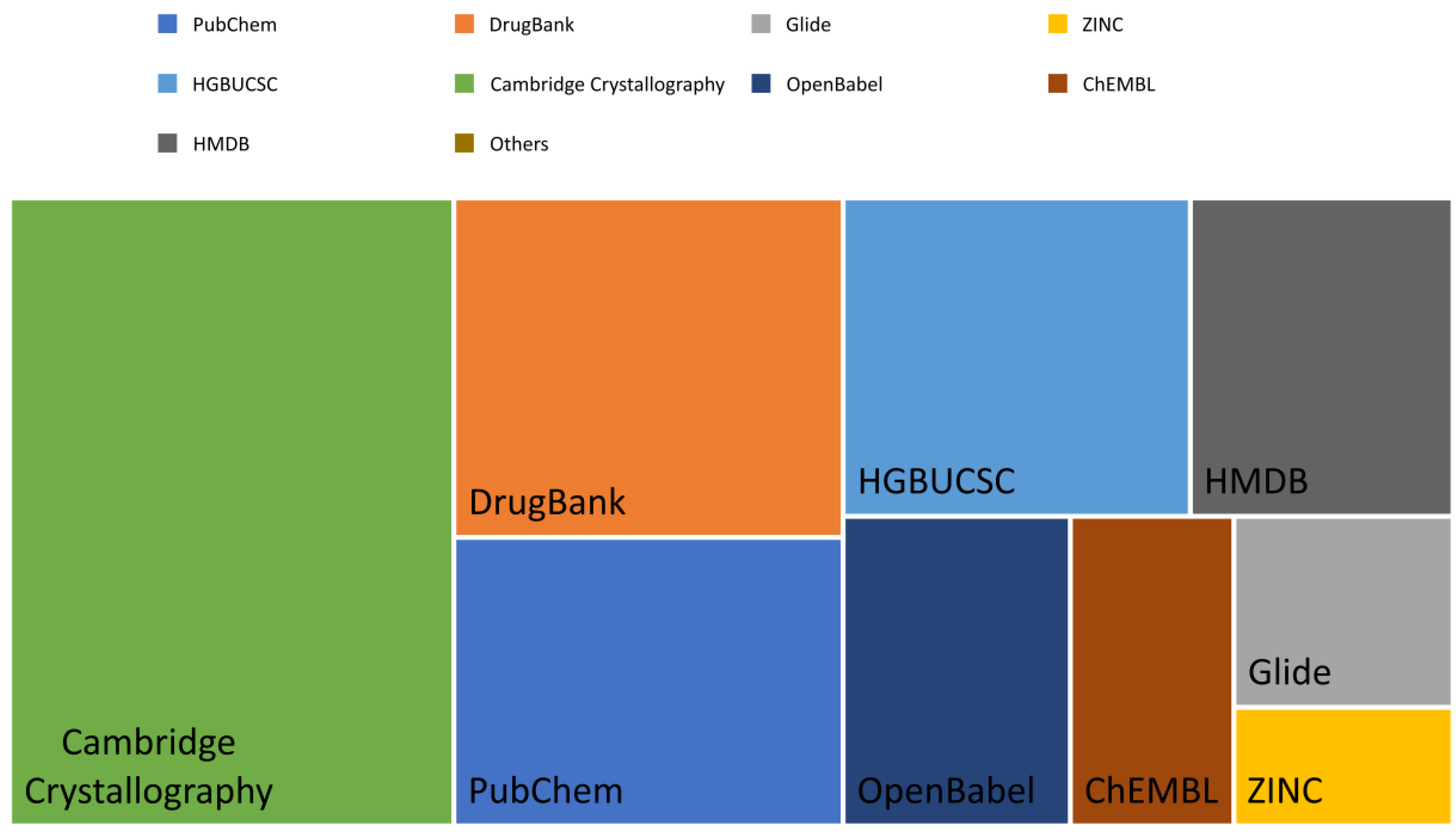

| Needs | The origin of in silico methods dates back to the late ’80s. At the time, medicinal chemists were required to produce evidence of structure-activity-relationship (SAR) from molecules within the same pharmacological class of therapeutical agents. This was, for all intents and purposes, essentially an academic exercise. In the ’90s, thanks to the advent of the graphical processor unit (GPU), researchers moved from 2D- to 3D- up to multidimensional SAR. This evolution allowed the boom of in silico methods mainly via two techniques: ligand-based fitting and target-based docking. The growing availability of commercial software as well as the open-approach to developing computer-assisted visualization allowed generating an enormous body of publications in this field from a few hundred per year in the late ’80s to 10,000 per year in the late ’90s. This exponential growth of data prompted the launch of PubMedTM and DrugBankTM in the early 2000s. Following this trend, the largest and most prominent collection of crystallographic structures from Cambridge University has evolved to host several million chemical items and their respective chemical-physical information. Involuntarily, drug discovery entered the big data era. |

| Opportunity | During the study of new chemical entities (NCEs), medicinal chemists have several possibilities at their disposal to bring NCEs to the market as quickly as possible. Sometimes, the success story arrives via serendipity, other times by trial-and- error and, most recently, during clinical investigations via drug repurposing. Drug repurposing is one of those strategies that has improved mostly in the past ten years. A good example of this is the number of new approved drugs (NADs) granted by the USFDA during the COVID-19 pandemic crisis: 90% of these NADs have emerged as a result of drug repurposing. |

| Gap | One of the main forces driving the advance in drug discovery was the search for high selectivity of biological targets, following the principle: one molecule for one specific binding site. However, the inevitable overlap of data stemming from computational visualization, clinical trials, and medical reports has confirmed that this principle of one molecule for one binding site is an excellent theory in a perfect world, but in reality, highly difficult to achieve. The most recent trend in drug discovery is the multi-target drug approach (MTD). In this type of approach, the in silico methods are suitable to discriminate via ab initio the relationship between molecular activity, specific end-user population, and drug-drug (and drug-receptor) interaction upstream of clinical investigations. Moreover, the evolution of databases via web-based server applications has created a brand-new field in the search for novel drugs, called chemical space. |

| Recommendation | For more than a century, the R&D departments of the major pharmaceutical companies were known to be a highly secretive environment with tens of thousands of chemists working on individual and personalized clean benches, and not communicating outside of their close circle of team members. Today’s setting is completely different. The loss of patent protections for the most important blockbusters, and the legal dispute surrounding patents relating to drug repurposing uses has reduced the necessity for this “special environment” in the pharmaceutical industry. Consequently, there has been a large layoff of highly skilled pharmaceutical professionals. Paradoxically, computer-assisted technologies have not produced the expected number of novel solutions, and the emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) now requires a new generation of skilled scientists in this new area going from data science to network pharmacology. Moreover, given the implicit difficulty in finding such multi-task medicinal chemists, the current R&D departments of the major pharmaceutical companies are increasingly becoming incubators/accelerators of start-ups and consortiums of public-private partnerships in which the various stakeholders are invited to interact and collaborate, especially in remote mode. In silico methods have not only brought out the digitalization of pharmaceutical science, but the entire manner in which scientists think about the definition of drug-biology interactions. The next step of in silico methods is the merging of chemical laboratory automation and synthetic tissues (organ-on-chip). At this juncture, even clinical trial investigations will become obsolete, and will run purely via computers: i. e. in silico medicine. |

Introduction

QSAR: Quantitative-Structure-Activity-Relationship

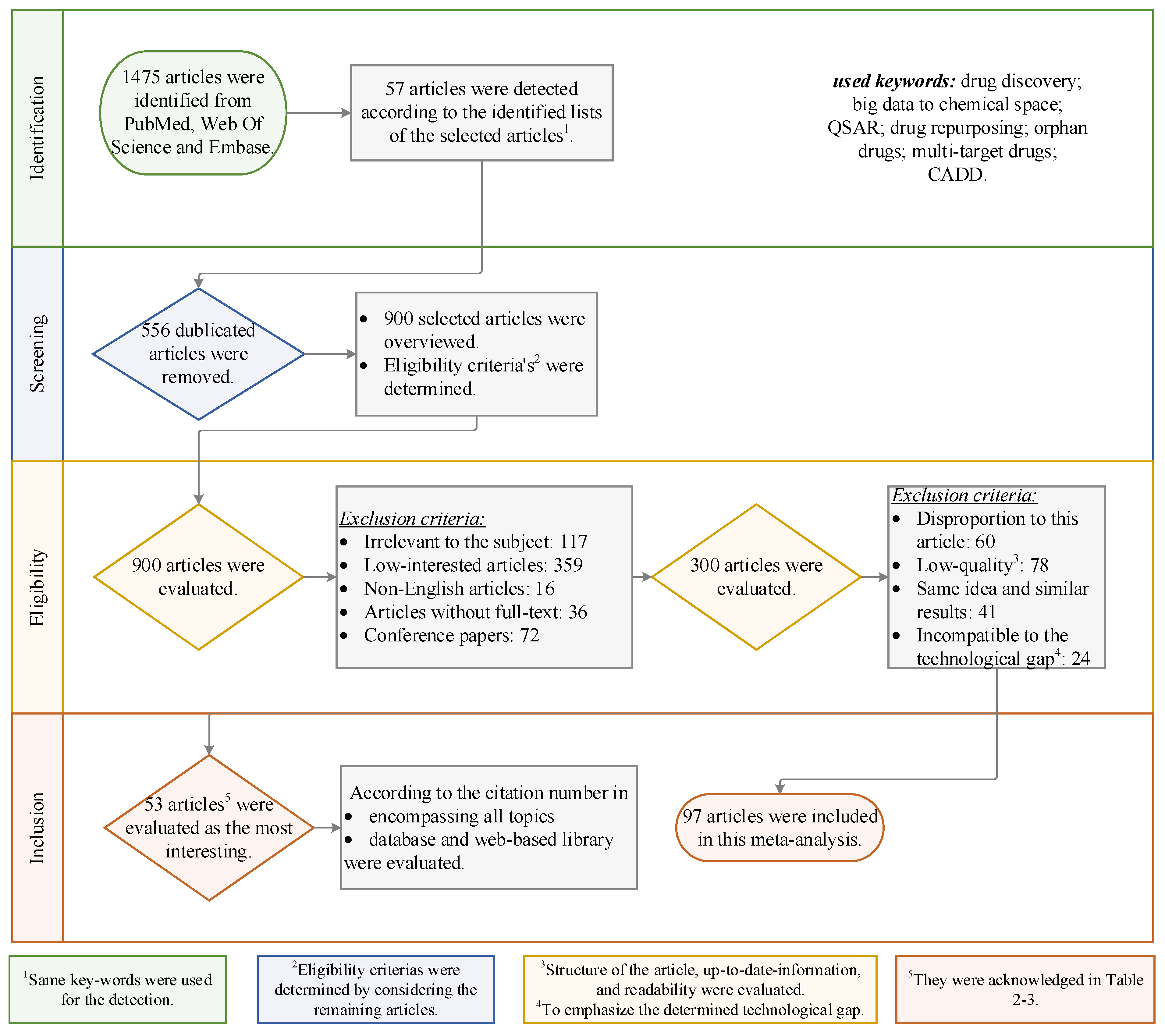

Methodology of the Meta-Analysis

Results

General Consideration: “Quality” of the Data

Validation of the Proposed Meta-Analysis

| Number | Topic | Title | First author | Year | Citations | Ref |

| 1 | Bioinformatics | Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome | HG Consortium | 2001 | 28696 | [35] |

| 2 | Database | The Cambridge Structural Database: a quarter of a million crystal structures and rising | FH Allen | 2002 | 14390 | [36] |

| 3 | Bioinformatics | Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics | RC Gentleman | 2004 | 13462 | [37] |

| 4 | Database | The human genome browser at UCSC | WJ Kent | 2002 | 10583 | [38] |

| 5 | Database | The Cambridge structural database | CR Groom | 2016 | 7366 | [39] |

| 6 | Database | OpenBabel: An open chemical toolbox | NM O Boyle | 2011 | 6735 | [40] |

| 7 | Bioinformatics | A review of feature selection techniques in bioinformatics | Y Saeys | 2007 | 5556 | [41] |

| 8 | Software | CHARMM General Force Field (CGenFF): A force field for drug-like molecules compatible with the CHARMM all-atom additive biological force fields | K Vanommeslaeghr | 2010 | 5130 | [42] |

| 9 | Bioinformatics | The Perseus computational platform for comprehensive analysis of omics data | S Tyanova | 2016 | 5068 | [43] |

| 10 | Database | DrugBank 5.0: a major update to the DrugBank database for 2018 | DS Wishart | 2018 | 4951 | [44] |

| 11 | Bioinformatics | Accurate whole human genome sequencing using reversible terminator chemistry | DR Bentley | 2001 | 4691 | [45] |

| 12 | Database | Glide: A New Approach for Rapid, Accurate Docking and Scoring. 2. Enrichment Factors in Database Screening | TA Halgren | 2004 | 4234 | [46] |

| 13 | Model Predict | Lead- and drug-like compounds: the rule-of-five revolution | CA Lipinski | 2004 | 4213 | [47] |

| 14 | Model Predict | Drug-like properties and the causes of poor solubility and poor permeability | CA Lipinski | 2000 | 3912 | [48] |

| 15 | Bioinformatics | Biopython: freely available Python tools for computational molecular biology and bioinformatics | PJA Cock | 2009 | 3885 | [49] |

| 16 | Database | PubChem substance and compound databases | S Kim | 2016 | 3853 | [50] |

| 17 | Bioinformatics | The druggable genome | AL Hopkins | 2002 | 3851 | [51] |

| 18 | Model Predict | Drug discovery: a historical perspective | J Drews | 2000 | 3582 | [52] |

| 19 | Database | New software for searching the Cambridge Structural Database and visualizing crystal structures | IJ Bruno | 2002 | 3581 | [53] |

| 20 | Database | DrugBank: resource in silico drug discovery and exploration | DS Wishart | 2006 | 3544 | [54] |

| 21 | Bioinformatics | From genomics to chemical genomics: new developments in KEGG | M Kaneshisa | 2006 | 3473 | [55] |

| 22 | Chemical Space | Network pharmacology: the next paradigm in drug discovery | AL Hopkins | 2008 | 3438 | [56] |

| 23 | Database | ChEMBL: a large-scale bioactivity database for drug discovery | A Gaulton | 2012 | 3390 | [57] |

| 24 | Database | HMDB 3.0--The Human Metabolome Database in 2013 | DS Wishart | 2012 | 3061 | [58] |

| 25 | QSAR | Random forest: a classification and regression tool for compound classification and QSAR modelingD | V Svetnik | 2003 | 3052 | [59] |

| 26 | Database | HMDB 4.0: the human metabolome database for 2018 | DS Wishart | 2018 | 2928 | [60] |

| 27 | Drug Repositioning | Drug repositioning: identifying and developing new uses for existing drugs | TT Ashburn | 2004 | 2914 | [61] |

| 28 | Database | DrugBank: a knowledgebase of drugs, drug actions, and drug targets | DS Wishart | 2008 | 2785 | [62] |

| Number | Title | First Author | Year | Citation | Reference |

| 1 | The Cambridge Database: a quarter of a million structure and rising | FH Allen | 2002 | 14390 | [36] |

| 2 | The Human Genome Browser at UCSC | WJ Kent | 2002 | 10583 | [38] |

| 3 | New software for searching the Cambridge Structural Database and visualizing crystal structures | IJ Bruno | 2002 | 3581 | [53] |

| 4 | Glide: A New Approach for Rapid, Accurate Docking and Scoring. 2. Enrichment Factors in Database Screening | TA Halgren | 2004 | 4234 | [46] |

| 5 | DrugBank: a comprehensive resource for in silico drug discovery and exploration | DS Wishart | 2006 | 3544 | [54] |

| 6 | BindingDB: a web-accessible database of experimentally determined protein-ligand binding affinities | T Liu | 2007 | 1663 | [63] |

| 7 | ChEBI: a database and ontology for chemical entities of biological interest | K Deglyarenko | 2007 | 1155 | [64] |

| 8 | PubChem: Integrated platform of small molecules and biological actives | EE Bolton | 2008 | 1537 | [65] |

| 9 | DrugBank: a knowledgebase for drugs, drug actions, and drug targets | DS Wishart | 2008 | 2785 | [62] |

| 10 | PubChem: a public information system for analyzing bioactivities of small molecules | Y Wang | 2009 | 1317 | [66] |

| 11 | DrugBank 3.0: a comprehensive resource for ‘OMICS’ research on drugs | C Knox | 2010 | 2034 | [67] |

| 12 | Conformer Generation with OMEGA: Algorithm and Validation Using High Quality Structures from the Protein Databank and Cambridge Structural Database | PCD Hawkins | 2010 | 1367 | [68] |

| 13 | Open Babel: An open chemical toolbox | NM O Boyle | 2011 | 6735 | [40] |

| 14 | ChEMBL: a large-scale bioactivity database for drug discovery | A Gaulton | 2012 | 3390 | [57] |

| 15 | HMDB 3.0—The Human Metabolome Database in 2013 | DS Wishart | 2012 | 3061 | [58] |

| 16 | ZINC: a free tool to discover chemistry for biology | JJ Irwin | 2012 | 2481 | [69] |

| 17 | ChEMBL: a large-scale bioactivity database for drug discovery | A Gaulton | 2012 | 1782 | [57] |

| 18 | DrugBank 4.0: Shedding new light on drug metabolism | V Law | 2014 | 2103 | [70] |

| 19 | The Cambridge structural database | CR Groom | 2016 | 7366 | [39] |

| 20 | PubChem substance and compound databases | S Kim | 2016 | 3853 | [50] |

| 21 | The ChEMBL database in 2017 | A Gaulton | 2017 | 1731 | [71] |

| 22 | DrugBank 5.0: a major update to the DrugBank database for 2018 | DS Wishart | 2018 | 4951 | [44] |

| 23 | HMDB 4.0: the human metabolome database for 2018 | DS Wishart | 2018 | 2928 | [60] |

| 24 | PubChem 2019 update improved access to chemical data | S Kim | 2019 | 2380 | [72] |

| 25 | PubChem in 2021: new data content and improved web interfaces | S Kim | 2021 | 1657 | [73] |

Discussion, Limitations/Uncertainty

- (i)

- find a target of suitable function.

- (ii)

- identify the ‘best binder’ by high-throughput screening of large combinatorial libraries and/or by rational drug design based on the three-dimensional structure of the target.

- (iii)

- provide a set of proof-of-principle experiments.

- (iv)

- develop a technology platform that predicts potential clinical applications.

Conclusion

-

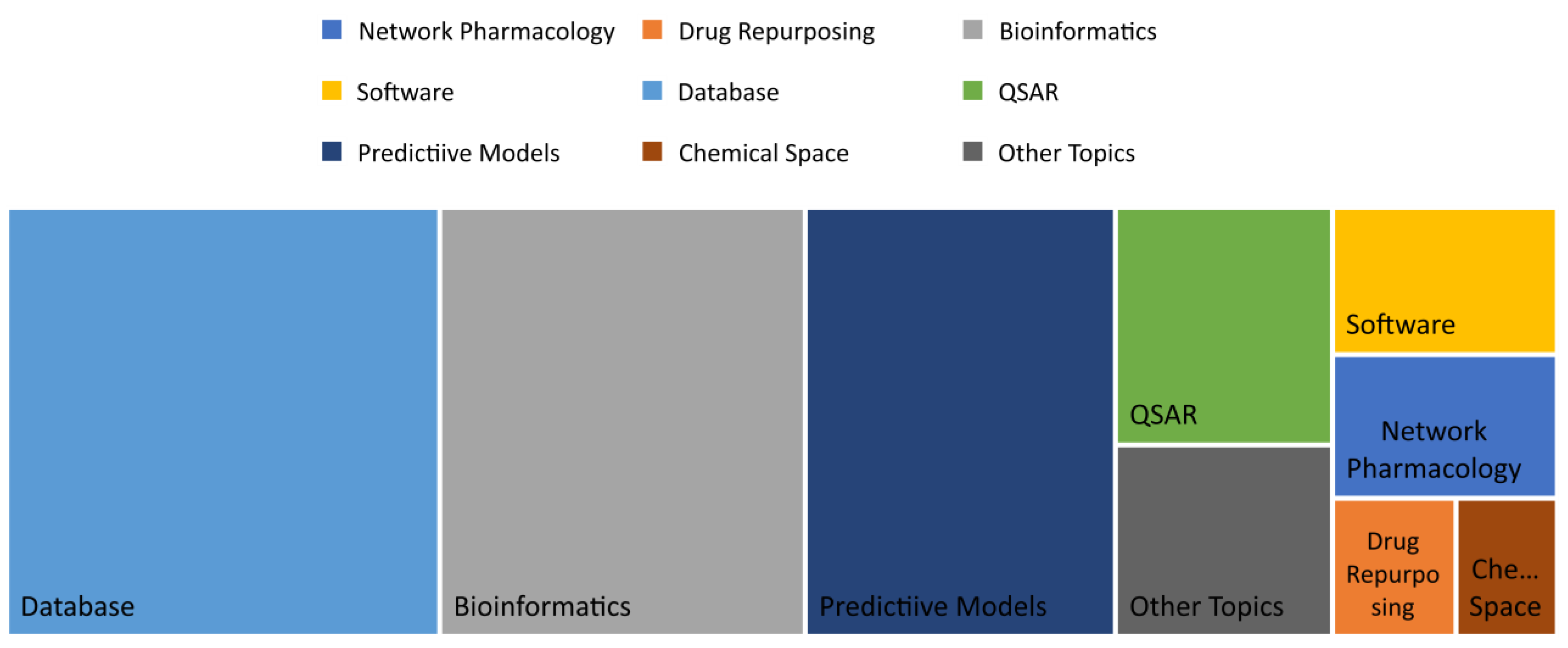

Big Data: Data Science, Data Integration and Data MiningThe result of these disciplines is the continuing improvement in IT infrastructure and software. Incorporating advanced AI and ML techniques can enhance in silico drug discovery by rapidly analyzing vast amounts of data, predicting molecular interactions, and optimizing drug candidates with higher precision and efficiency.

-

Cheminformatics: classification, pattern recognition and clusteringThe result of these disciplines is the improvement in current knowledge regarding the mechanisms of actions of drugs owing to a better understanding of their QSAR.

-

Bioinformatics and Translational BioinformaticsThe result of these disciplines is the seeking of new molecular targets and alternative physio/pathological mechanisms downstream. In particular, these disciplines are pivotal for the understanding of epigenetics and meta-genomics phenomena.

-

Drug RepurposingThe primary scope of this discipline is the life extension of expired patent applications. In practice, the controversy related to patent issues and the ensuing transfer of Drug Master Files (DMF) have accelerated the need for collaborative models among pharmaceutical stakeholders. The result is the shrinking of the required internal R&D workforce.

-

Chemical SpaceThe chemical space is the ensemble of all possible chemical structures, which is believed to contain up to several billion molecules of potential interest for drug discovery as mentioned in this review. One proposed means to explore chemical space is based on the selection of virtual libraries of common scaffold-tree algorithms (grouping) that are overlapped to other “organized maps” of chemical-physical information (pharmacokinetics) and/or chemical interactions (pharmacodynamics). The result of this “spatial analysis” has been used in the last 20 years to generate a new discipline known as Network Medicine or Network Pharmacology. Conversely to drug repurposing strategies in which one molecule (“old API”) is investigated for a new medical indication following the principle of one drug for one targe the results in Network Pharmacology approaches to drug discovery are completely different. Indeed, in terms of the definition of chemical space, there are billions of potential drugs that could virtually match billions of targets. The best matching combinations are hence known as multi-target drugs (MTD), including in Food, Aroma, and other fields.

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

References

- Stanley, H. Nusim, Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients, vol. 205. 2005.

- A. S. Pina, A. Hussain, and A. C. A. Roque, “An Historical Overview of Drug Discovery,” in Ligand-Macromolecular Interactions in Drug Discovery: Methods and Protocols, A. C. A. Roque, Ed., Totowa, NJ: Humana Press, 2010, pp. 3–12. [CrossRef]

- Ban, T.A. The role of serendipity in drug discovery. Dialog- Clin. Neurosci. 2006, 8, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, S.; Grootendorst, P.; Lexchin, J.; Cunningham, C.; Greyson, D. The cost of drug development: A systematic review. Health Policy 2011, 100, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Ke, Z.; Liu, C.; Wang, Z.; Liu, D.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; He, W.; Xu, Z.; Li, Y.; et al. Systemic In Silico Screening in Drug Discovery for Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) with an Online Interactive Web Server. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020, 60, 5735–5745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pushpakom, S.; Iorio, F.; Eyers, P.A.; Escott, K.J.; Hopper, S.; Wells, A.; Doig, A.; Guilliams, T.; Latimer, J.; McNamee, C.; et al. Drug repurposing: progress, challenges and recommendations. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- How to improve R&D productivity: the pharmaceutical industry’s grand challenge | Nature Reviews Drug Discovery.” Accessed: Nov. 28, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.nature.com/articles/nrd3078.

- “CADD and Informatics in Drug Discovery | SpringerLink.” Accessed: Nov. 28, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-981-99-1316-9.

- Nag, S.; Baidya, A.T.K.; Mandal, A.; Mathew, A.T.; Das, B.; Devi, B.; Kumar, R. Deep learning tools for advancing drug discovery and development. 3 Biotech 2022, 12, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Gudivada, R.C.; Aronow, B.J.; Jegga, A.G. Computational drug repositioning through heterogeneous network clustering. BMC Syst. Biol. 2013, 7, S6–S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Kirchmair, J. Cheminformatics in Natural Product-Based Drug Discovery. Mol. Informatics 2020, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Liu, X.; Zhang, S.; Chen, S. Artificial intelligence for drug discovery: Resources, methods, and applications. Mol. Ther. - Nucleic Acids 2023, 31, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherkasov, A. The 'Big Bang' of the chemical universe. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2023, 19, 667–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H. Big Data and Artificial Intelligence Modeling for Drug Discovery. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2020, 60, 573–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, S.M.S.-F.; Contrepois, K.; Moneghetti, K.J.; Zhou, W.; Mishra, T.; Mataraso, S.; Dagan-Rosenfeld, O.; Ganz, A.B.; Dunn, J.; Hornburg, D.; et al. A longitudinal big data approach for precision health. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 792–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Butte, A. Leveraging big data to transform target selection and drug discovery. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 99, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neri, D.; Lerner, R.A. DNA-Encoded Chemical Libraries: A Selection System Based on Endowing Organic Compounds with Amplifiable Information. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2018, 87, 479–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadybekov, A.A.; Sadybekov, A.; Liu, Y.; Iliopoulos-Tsoutsouvas, C.; Huang, X.-P.; Pickett, J.; Houser, B.; Patel, N.; Tran, N.K.; Tong, F.; et al. Synthon-based ligand discovery in virtual libraries of over 11 billion compounds. Nature 2021, 601, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, J.; Irwin, J.J.; Shoichet, B.K. Modeling the expansion of virtual screening libraries. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2023, 19, 712–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, T.; Xie, L. Providing data science support for systems pharmacology and its implications to drug discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2016, 11, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, L.; Thakkar, A.; Mercado, R.; Engkvist, O. Molecular representations in AI-driven drug discovery: a review and practical guide. J. Chemin- 2020, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatansever, S.; Schlessinger, A.; Wacker, D.; Kaniskan, H. .; Jin, J.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, B. Artificial intelligence and machine learning-aided drug discovery in central nervous system diseases: State-of-the-arts and future directions. Med. Res. Rev. 2020, 41, 1427–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drug discovery with explainable artificial intelligence | Nature Machine Intelligence.” Accessed: Nov. 28, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.nature.com/articles/s42256-020-00236-4.

- Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Byrne, R.; Schneider, G.; Yang, S. Concepts of Artificial Intelligence for Computer-Assisted Drug Discovery. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 10520–10594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooller, S.K.; Benstead-Hume, G.; Chen, X.; Ali, Y.; Pearl, F.M. Bioinformatics in translational drug discovery. Biosci. Rep. 2017, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carracedo-Reboredo, P.; Linares-Blanco, J.; Rodriguez-Fernandez, N.; Cedron, F.; Novoa, F.J.; Carballal, A.; Maojo, V.; Pazos, A.; Fernandez-Lozano, C. A review on machine learning approaches and trends in drug discovery. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 4538–4558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segall, M.D.; Barber, C. Addressing toxicity risk when designing and selecting compounds in early drug discovery. Drug Discov. Today 2014, 19, 688–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuoco, D. Classification Framework and Chemical Biology of Tetracycline-Structure-Based Drugs. Antibiotics 2012, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, G.; Mjalli, A.M.M.; Kutz, M.E. Integrated Approaches to Perform In Silico Drug Discovery. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2006, 3, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halevi, G.; Moed, H.; Bar-Ilan, J. Suitability of Google Scholar as a source of scientific information and as a source of data for scientific evaluation—Review of the Literature. J. Inf. 2017, 11, 823–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radicchi, F.; Weissman, A.; Bollen, J. Quantifying perceived impact of scientific publications. J. Inf. 2017, 11, 704–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauvayre, R. Types of Errors Hiding in Google Scholar Data. J. Med Internet Res. 2022, 24, e28354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayo-Wilson, E.; Li, T.; Fusco, N.; Dickersin, K. ; for the MUDS investigators Practical guidance for using multiple data sources in systematic reviews and meta-analyses (with examples from the MUDS study). Res. Synth. Methods 2017, 9, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusenbauer, M.; Haddaway, N.R. Which academic search systems are suitable for systematic reviews or meta-analyses? Evaluating retrieval qualities of Google Scholar, PubMed, and 26 other resources. Res. Synth. Methods 2019, 11, 181–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lander, E.S.; Linton, L.M.; Birren, B.; Nusbaum, C. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature 2001, 409, 860–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, F.H. The Cambridge Structural Database: a quarter of a million crystal structures and rising. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B Struct. Sci. 2002, 58, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentleman, R.C.; Carey, V.J.; Bates, D.M.; Bolstad, B.; Dettling, M.; Dudoit, S.; Ellis, B.; Gautier, L.; Ge, Y.; Gentry, J.; et al. Bioconductor: Open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004, 5, R80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kent, W.J.; Sugnet, C.W.; Furey, T.S.; Roskin, K.M.; Pringle, T.H.; Zahler, A.M.; Haussler, D. The Human Genome Browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 2002, 12, 996–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groom, C.R.; Bruno, I.J.; Lightfoot, M.P.; Ward, S.C. The Cambridge Structural Database. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B Struct. Sci. 2016, 72, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Boyle, N.M.; Banck, M.; James, C.A.; Morley, C.; Vandermeersch, T.; Hutchison, G.R. Open babel: An open chemical toolbox. J. Cheminform. 2011, 3, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeys, Y.; Inza, I.; Larrañaga, P. A review of feature selection techniques in bioinformatics. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 2507–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanommeslaeghe, K.; Hatcher, E.; Acharya, C.; Kundu, S.; Zhong, S.; Shim, J.; Darian, E.; Guvench, O.; Lopes, P.; Vorobyov, I.; et al. CHARMM General Force Field: A Force Field for Drug-Like Molecules Compatible with the CHARMM All-Atom Additive Biological Force Fields. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 671–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyanova, S.; Temu, T.; Sinitcyn, P.; Carlson, A.; Hein, M.Y.; Geiger, T.; Mann, M.; Cox, J. The Perseus computational platform for comprehensive analysis of (prote)omics data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wishart, D.S.; Feunang, Y.D.; Guo, A.C.; Lo, E.J.; Marcu, A.; Grant, J.R.; Sajed, T.; Johnson, D.; Li, C.; Sayeeda, Z.; et al. DrugBank 5.0: A Major Update to the DrugBank Database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D1074–D1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, D.R.; Balasubramanian, S.; Swerdlow, H.P.; Smith, G.P.; Milton, J.; Brown, C.G.; Hall, K.P.; Evers, D.J.; Barnes, C.L.; Bignell, H.R.; et al. Accurate whole human genome sequencing using reversible terminator chemistry. Nature 2008, 456, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halgren, T.A.; Murphy, R.B.; Friesner, R.A.; Beard, H.S.; Frye, L.L.; Pollard, W.T.; Banks, J.L. Glide: A New Approach for Rapid, Accurate Docking and Scoring. 2. Enrichment Factors in Database Screening. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 1750–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipinski, C.A. Lead- and drug-like compounds: the rule-of-five revolution. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 2004, 1, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipinski, C.A. Drug-like properties and the causes of poor solubility and poor permeability. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 2000, 44, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cock, P.J.A.; Antao, T.; Chang, J.T.; Chapman, B.A.; Cox, C.J.; Dalke, A.; Friedberg, I.; Hamelryck, T.; Kauff, F.; Wilczynski, B.; et al. Biopython: freely available Python tools for computational molecular biology and bioinformatics. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1422–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Thiessen, P.A.; Bolton, E.E.; Chen, J.; Fu, G.; Gindulyte, A.; Han, L.; He, J.; He, S.; Shoemaker, B.A.; et al. PubChem substance and compound databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 44, D1202–D1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The druggable genome | Nature Reviews Drug Discovery.” Accessed: Dec. 09, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.nature.com/articles/nrd892.

- Drews, J. Drug Discovery: A Historical Perspective. Science 2000, 287, 1960–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruno, I.J.; Cole, J.C.; Edgington, P.R.; Kessler, M.; Macrae, C.F.; McCabe, P.; Pearson, J.; Taylor, R. New software for searching the Cambridge Structural Database and visualizing crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B Struct. Sci. 2002, 58, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wishart, D.S.; Knox, C.; Guo, A.C.; Shrivastava, S.; Hassanali, M.; Stothard, P.; Chang, Z.; Woolsey, J. DrugBank: A comprehensive resource for in silico drug discovery and exploration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, D668–D672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M. From genomics to chemical genomics: new developments in KEGG. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, D354–D357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, A.L. Network pharmacology: the next paradigm in drug discovery. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008, 4, 682–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaulton, A.; Bellis, L.J.; Bento, A.P.; Chambers, J.; Davies, M.; Hersey, A.; Light, Y.; McGlinchey, S.; Michalovich, D.; Al-Lazikani, B.; et al. ChEMBL: a large-scale bioactivity database for drug discovery. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, D1100–D1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wishart, D.S.; Jewison, T.; Guo, A.C.; Wilson, M.; Knox, C.; Liu, Y.; Djoumbou, Y.; Mandal, R.; Aziat, F.; Dong, E.; et al. HMDB 3.0—The Human Metabolome Database in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D801–D807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svetnik, V.; Liaw, A.; Tong, C.; Culberson, J.C.; Sheridan, R.P.; Feuston, B.P. Random Forest: A Classification and Regression Tool for Compound Classification and QSAR Modeling. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2003, 43, 1947–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wishart, D.S.; Feunang, Y.D.; Marcu, A.; Guo, A.C.; Liang, K.; Vázquez-Fresno, R.; Sajed, T.; Johnson, D.; Li, C.; Karu, N.; et al. HMDB 4.0: The human metabolome database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D608–D617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drug repositioning: identifying and developing new uses for existing drugs | Nature Reviews Drug Discovery.” Accessed: Dec. 09, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.nature.com/articles/nrd1468.

- Wishart, D.S.; Knox, C.; Guo, A.C.; Cheng, D.; Shrivastava, S.; Tzur, D.; Gautam, B.; Hassanali, M. DrugBank: a knowledgebase for drugs, drug actions and drug targets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, D901–D906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Lin, Y.; Wen, X.; Jorissen, R.N.; Gilson, M.K. BindingDB: a web-accessible database of experimentally determined protein-ligand binding affinities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, D198–D201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degtyarenko, K.; de Matos, P.; Ennis, M.; Hastings, J.; Zbinden, M.; McNaught, A.; Alcantara, R.; Darsow, M.; Guedj, M.; Ashburner, M. ChEBI: a database and ontology for chemical entities of biological interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 36, D344–D350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E. E. Bolton, Y. Wang, P. A. Thiessen, and S. H. Bryant, “Chapter 12 - PubChem: Integrated Platform of Small Molecules and Biological Activities,” in Annual Reports in Computational Chemistry, vol. 4, R. A. Wheeler and D. C. Spellmeyer, Eds., Elsevier, 2008, pp. 217–241. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xiao, J.; Suzek, T.O.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Bryant, S.H. PubChem: A public information system for analyzing bioactivities of small molecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37 (Suppl. 2), W623–W633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, C.; Law, V.; Jewison, T.; Liu, P.; Ly, S.; Frolkis, A.; Pon, A.; Banco, K.; Mak, C.; Neveu, V.; et al. DrugBank 3.0: a comprehensive resource for 'Omics' research on drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 39, D1035–D1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, P.C.D.; Skillman, A.G.; Warren, G.L.; Ellingson, B.A.; Stahl, M.T. Conformer Generation with OMEGA: Algorithm and Validation Using High Quality Structures from the Protein Databank and Cambridge Structural Database. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2010, 50, 572–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irwin, J.J.; Sterling, T.; Mysinger, M.M.; Bolstad, E.S.; Coleman, R.G. ZINC: A Free Tool to Discover Chemistry for Biology. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2012, 52, 1757–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, V.; Knox, C.; Djoumbou, Y.; Jewison, T.; Guo, A.C.; Liu, Y.; Maciejewski, A.; Arndt, D.; Wilson, M.; Neveu, V.; et al. DrugBank 4.0: shedding new light on drug metabolism. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 42, D1091–D1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaulton, A.; Hersey, A.; Nowotka, M.; Bento, A.P.; Chambers, J.; Mendez, D.; Mutowo, P.; Atkinson, F.; Bellis, L.J.; Cibrián-Uhalte, E.; et al. The ChEMBL database in 2017. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Chen, J.; Cheng, T.; Gindulyte, A.; He, J.; He, S.; Li, Q.; Shoemaker, B.A.; Thiessen, P.A.; Yu, B.; et al. PubChem 2019 update: Improved access to chemical data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D1102–D1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Chen, J.; Cheng, T.; Gindulyte, A.; He, J.; He, S.; Li, Q.; Shoemaker, B.A.; Thiessen, P.A.; Yu, B.; et al. PubChem in 2021: new data content and improved web interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D1388–D1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthews, H.; Hanison, J.; Nirmalan, N. “Omics”-Informed Drug and Biomarker Discovery: Opportunities, Challenges and Future Perspectives. Proteomes 2016, 4, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S. Getting the most out of PubChem for virtual screening. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2016, 11, 843–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D. Fuoco, “Hypothesis for changing models: current pharmaceutical paradigms, trends and approaches in drug discovery,” PeerJ, vol. 3, Feb. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Parsons, A.B.; Brost, R.L.; Ding, H.; Li, Z.; Zhang, C.; Sheikh, B.; Brown, G.W.; Kane, P.M.; Hughes, T.R.; Boone, C. Integration of chemical-genetic and genetic interaction data links bioactive compounds to cellular target pathways. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003, 22, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csermely, P.; Agoston, V.; Pongor, S. The efficiency of multi-target drugs: the network approach might help drug design. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2005, 26, 178–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolini, G.V.; Shapland, R.H.B.; van Hoorn, W.P.; Mason, J.S.; Hopkins, A.L. Global mapping of pharmacological space. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006, 24, 805–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lill, M.A. Multi-dimensional QSAR in drug discovery. Drug Discov. Today 2007, 12, 1013–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourches, D.; Muratov, E.; Tropsha, A. Trust, But Verify: On the Importance of Chemical Structure Curation in Cheminformatics and QSAR Modeling Research. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2010, 50, 1189–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthyala, R. Orphan/rare drug discovery through drug repositioning. Drug Discov. Today: Ther. Strat. 2011, 8, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusher, S.J.; McGuire, R.; van Schaik, R.C.; Nicholson, C.D.; de Vlieg, J. Data-driven medicinal chemistry in the era of big data. Drug Discov. Today 2014, 19, 859–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuoco, D. A New Method for Characterization of Natural Zeolites and Organic Nanostructure using Atomic Force Microscopy. Nat. Précéd. [CrossRef]

- D. Fuoco et al., “Identifying nutritional, functional, and quality of life correlates with male hypogonadism in advanced cancer patients,” ecancermedicalscience, vol. 9, 2015, Accessed: Feb. 04, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4544574/.

- D. Fuoco, “Cytotoxicity induced by tetracyclines via protein photooxidation,” Advances in Toxicology, vol. 2015, 2015, Accessed: Feb. 04, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://downloads.hindawi.com/archive/2015/787129.pdf.

- Talevi, A. Multi-target pharmacology: possibilities and limitations of the “skeleton key approach” from a medicinal chemist perspective. Front. Pharmacol. 2015, 6, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavecchia, A.; Cerchia, C. In silico methods to address polypharmacology: current status, applications and future perspectives. Drug Discov. Today 2016, 21, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Desai, R.J.; Handy, D.E.; Wang, R.; Schneeweiss, S.; Barabási, A.-L.; Loscalzo, J. Network-based approach to prediction and population-based validation of in silico drug repurposing. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viana, J.d.O.; Félix, M.B.; Maia, M.d.S.; Serafim, V.d.L.; Scotti, L.; Scotti, M.T. Drug discovery and computational strategies in the multitarget drugs era. Braz. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, R.R.; Popovic-Nikolicb, M.R.; Nikolic, K.; Uliassi, E.; Bolognesi, M.L. A perspective on multi-target drug discovery and design for complex diseases. Clin. Transl. Med. 2018, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buenz, E.J.; Verpoorte, R.; Bauer, B.A. The Ethnopharmacologic Contribution to Bioprospecting Natural Products. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2017, 58, 509–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesiti, F.; Chavarria, D.; Gaspar, A.; Alcaro, S.; Borges, F. The chemistry toolbox of multitarget-directed ligands for Alzheimer's disease. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 181, 111572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geerts, H.; Wikswo, J.; van der Graaf, P.H.; Bai, J.P.; Gaiteri, C.; Bennett, D.; Swalley, S.E.; Schuck, E.; Kaddurah-Daouk, R.; Tsaioun, K.; et al. Quantitative Systems Pharmacology for Neuroscience Drug Discovery and Development: Current Status, Opportunities, and Challenges. CPT: Pharmacometrics Syst. Pharmacol. 2019, 9, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namdar, D.; Anis, O.; Poulin, P.; Koltai, H. Chronological Review and Rational and Future Prospects of Cannabis-Based Drug Development. Molecules 2020, 25, 4821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.-X.; Furtos, A.; Fuoco, D.; Boumghar, Y.; Patience, G.S. Meta-analysis and review of cannabinoids extraction and purification techniques. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2023, 101, 3108–3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullowney, M.W.; Duncan, K.R.; Elsayed, S.S.; Garg, N.; van der Hooft, J.J.J.; Martin, N.I.; Meijer, D.; Terlouw, B.R.; Biermann, F.; Blin, K.; et al. Artificial intelligence for natural product drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2023, 22, 895–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Big Data | |||||||

| Data Source |

Data Collection |

Data Integration |

Data Validation |

Data Application |

Data Visualization |

Data Real-World Evidence |

|

| Disciplines and sub-disciplines by relevance |

in vivo | Diseases | Translational Bioinformatics | Quantitative and Qualitative Structure Activity Relationship (QSAR) |

Active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) “One drug for one molecular target” |

Pharmacophore and molecular target |

Current use of API in clinical practice “One drug for many molecular targets, simultaneously” |

| Clinical outcome | |||||||

| ex vivo | Gene therapy | Bioinformatics | |||||

| Metabolites | |||||||

| in vitro | OMICS | ||||||

| Biochemistry | |||||||

| in silico | Medicinal chemistry | Cheminformatics | Virtual screening and 3D models |

||||

| Chemical physics | |||||||

| Predictive models | |||||||

| Key technologies | DATABASE: • Web-based server • IT-cloud • Extremely fast computing systems |

Data mining coupled with • Machine learning • Deep learning • Artificial intelligence |

Graphical processing unit (GPU): • Dedicated CRO |

Drug repurposing • IND |

Network pharmacology | Multi-target drugs | |

| Chemical Space | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).