1. Introduction

Cities have a central role to guarantee a sustainable future for the environment and citizens, as reflected by the 2030 Agenda [

1]. Strategic spatial planning can be considered as one of the key policies in guiding the sustainable development of urban areas, aiming at formulating a coherent spatial development strategy (territory-based or place-based integrating different agendas such as economic, environmental, cultural, social, and policy agendas) with expert knowledge [

2,

3]. As well defined by Albrechts, Balducci, and Hillier “Strategic spatial planning is a well-established transformative and integrative public-sector-led activity involving multi-level governance” [

4] and different actors during planning, decision-making, and implementation processes [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

In general, strategic planning emphasizes the dynamic nature of strategy-making for sustainable development and can be described as the systematic, integrated approach of policymaking, which considers context, resources, public administrations, territorial key stakeholders in a long-term horizon [

10]. As underlined by different scholars (among all, Salet & Faludi, 2000 and Sartorio,2005), it deals with theoretical and applied planning issue [

11,

12]: the first element is the concept of implementation, the long-term visions, and sustainable ideas about the potential future; the second element relates to the presence of one or more stakeholders on the territory, acting towards often opposite goals [

13].

Since the 1980s, strategic planning tried to construct a new “developmental decision science” as a response to the growing urban pressure [

5], defining practical steps used till now 1) context overview; 2) analysis and stakeholders’ participation; 3) definition of the vision, 4) strategy formulation, 5) definition and evaluation of actions and possible scenarios; 6) listing of actions through qualitative and quantitative analysis (ranking of priorities and timeline definition); and 7) monitoring.

Healey defines strategic planning as: “a social process through which a range of people in diverse institutional relations and positions come together to design plan-making processes and develop contents and strategies for the management of spatial change. This process generates […] a decision framework that may influence relevant parties in their future investments and regulatory activities” [

14].

Moreover, it is “a political as well as technical process - it is political not only in the sense of the politics in the process, but the concepts and ideas that we use in spatial planning are also political” [

15].

In recent years, sustainable development and environmental concerns have arisen and become important goals in urban and territorial planning [

16] and the awareness of landscape (its contribution to human well-being and its functioning) is clear in plans’ structural aspects [

2,

17,

18].

Therefore, strategic planning for territorial development is a key focus for local public administrations. Starting from the international context described above, it was introduced in Italy to provide a response to the crisis of the traditional urban planning system [

19]. It allows to move from the static and fixed state often associated with traditional urban planning methods, offering more dynamic and adaptable approaches to address contemporary challenges.

Considering different steps and issues in a unique methodology is the very purpose of strategic planning; at the local scale, it means to combine: the understanding of the own territory, the local political goals and the general priorities on a comprehensive sustainable and healthier future, guiding both public and private resources towards these priorities. Public administrations play a crucial role in this process. They must provide direction to ensure the construction of a shared vision and the implementation of a path that considers the overall interests of the community they serve [

19].

In Italy, the main law on town planning L. 1150/1942 identified a “cascade system” that involved a hierarchy among different territorial scales [

20], from the general to the particular, in a relationship of logical and functional continuity.

The territorial planning system was organized across three interconnected levels through hierarchical pathways:

- -

Supra-municipal planning (National, Regional, Provincial), which outlines the general land use guidelines,

- -

Municipal planning, which governs the organization of municipal territory,

- -

Implementation planning, which allows interventions on individual building uses.

In this sense municipal town planning assumed both the characteristics of a urban plan and an implementation plan: it contained structural elements for the medium to long term, as well as immediately enforceable. Therefore, the traditional municipal urban plan has proven to be ineffective over time due to the mismatch between the scale of predictions and the difficulty of adapting the tool to changing urban conditions. This is because of a “static” form of the plan and a procedural “cascade” process, leading to excessive inefficiencies and ineffectiveness. In other words, it relies on a plan format that doesn’t clearly distinguish between rules and procedures related to long-term objectives and choices, and those related to short-term forecasts and programmed actions [

21].

Subsequently, either a top-down process or a bottom-up process was used, thus adapting the contents of the various plans. The relationship between the various scale plans concerns the compatibility between the lower and upper levels, but it also implies a mutual evaluation of the choices made by the various levels in order to reach a consensus. [

22].

The urban planning law L. 1150/1942 initially focused on the layout and expansion of urban centers.

Subsequent legislation has embraced a broader view of urban planning, encompassing the entire territory for the localization and characterization of settlements and related infrastructures. This shift reflected an evolution noted by the Constitutional Court in 239/1982. Territorial governance is one of the areas specifically designated as concurrent legislation, with Regions responsible for legislation, except for determining fundamental principles, which is reserved for the State. Particularly, following the constitutional reform of 2001 (reform of Title V of the Constitution 3/2001) land governance is delegated to the regions.

The reference law for Lombardy Region is the Regional Law LR 12/2005.

LR 12/2005 introduces into municipal urban planning a plan called the Territorial Government Plan (PGT) [

23], replacing the traditional land-use plan of L. 1150/1942. This plan is divided into three documents: the Planning Document (PD), the Services Plan (SP), and the Rules Plan (RP).

This tripartition interprets the model proposed by the National Institute of Urbanism in 1995 [

24], which divides planning into structural time and operational time.

This duality corresponds to the metaphor of the different “speeds” of the components of the plan, explicitly indicating the need for an articulation of tools and procedures in municipal planning consistent with timeframes. Specifically, it involves identifying long-term choices and invariants, choices and actions to be programmed for medium or short-term implementation, and managing existing conditions with rules characterized by enduring qualities over time. [

21].

The structural plan and the operational plan are thus introduced. The Municipal Structural Plan represents the guiding tool through which the municipality defines urban-environmental strategies by identifying main issues and objectives to be achieved through the analysis of the infrastructure system, settlement system, and environmental system. The operational plan, on the other hand, contains public and private interventions to be carried out during an administrative term, assuming the significance of a technical-political document.

So the articulation into structural and operational of the municipal urban plan has been adopted differently by various regional laws, including Lombardy Region, as introduced before.

In particular, the PD defines the planning framework for economic and social development of the municipality, as well as the cognitive framework of the municipal territory and defines the objectives of planning.

The SP identifies the allocation of public areas and services.

The RP defines, within the entire municipal territory, the areas of the consolidated urban fabric, as the set of parts of territory on which building, or land transformation has already taken place.

In this sense, the PD includes strategic, programmatic, political and structural aspects, although it lasts for five years – actually a characteristic of the operational dimension. Therefore, it does not contain provisions that affect directly the regime of land, unlike Services and Rules Plan.

Each document, although with its own thematic autonomy, is indispensable for a single, coordinated planning process.

Moreover, considering its main strategic nature, the PD allows a deeper analysis on how political and administrative reforms within the municipal government could foster the well-being of individuals and places. Indeed, nowadays it’s fundamental to implement new decision-making frameworks that deal with the necessary political requirements for revitalizing the connection between urban planning and urban health to set health as a fundamental precondition for sustainable urban development [

25]. The evidence comes from what stated by the World Health Organization almost 80 years ago, considering health as an ongoing practice and not “merely [as] the absence of disease or infirmity” [

26]. The Ottawa Charter for health promotion, edited in 1986, further explains that health is a “resource for everyday life, not the objective of living” and “is a positive concept emphasizing social and personal resources, as well as physical capacities” [

27].

Nevertheless, health promotion requires the strict collaboration between the health sector and other non-health policy areas of government, such as social, economic, service, and environmental sectors [

28]. The concept of healthy city planning is considered by the authors as an integral element to be developed in the PD, encompassing not only the physical and social attributes that enhance human well-being, but also the programmatic actions that influence the distribution of such attributes in different areas. This aspect is understood more specifically in reference to the principles of the so-called “Healthy City” (HC).

The concept of the healthy city came to light in 1984 [

29]. This initiative aimed to put together a select group of European cities to collaborate on developing and implementing urban health promotion initiatives. The goal was to establish models and guidelines adaptable to various contexts, thus facilitating replication and future adjustments. The contemporary understanding of the HC concept is credited to Leonard Duhl and Trevor Hancock, both pivotal figures in the European healthy cities project from its beginning [

30]. They stated that HC is a place that is continually creating and improving the physical, social, and political environments and expanding the community resources that enable individuals and groups to support each other in performing all the functions of life and in developing themselves to their maximum potential [

31].

The present paper examines the methodology for drafting the urban PD as a strategic municipal document. In particular it will show the guidelines to define the strategies and the objectives applied to the city of Voghera, in Lombardy Region. It will outline what can be defined as strategic in shaping a more sustainable and healthier city. The definition of objectives is essential to track various dimensions of sustainability, including environmental, social, and economic aspects. These elements will help policymakers, urban planners, and stakeholders assess the effectiveness of policies and initiatives aimed at promoting sustainable development.

2. Materials and Methods

As shown in many studies, a city is a complex system considering the large number of agents and their interactions [

32,

33].

Furthermore, a city is a system that needs to evolve over time with the society and global changing. This implies that urban planning itself must adapt to the new conditions.

Creating livable and sustainable cities necessitates municipal planning strategies that prioritize promoting well-being and good health, responding to climate change, and creating a harmonious living environment, aligning with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [

34].

In this context, strategic planning comes into play, as it allows overcoming a merely reactive and contingent approach to understanding community issues and decision-making (the planning dimension). On the other hand, it incorporates forms of flexibility and stakeholder involvement within the planning process itself to avoid abstract simplifications of reality into overly deterministic and/or directive visions (the strategic dimension) [

19].

This knowledge brought to a renewed system of territorial planning in Lombardy Region, introducing the PD in the whole Municipal plan [

23]. Indeed, the PD, being bound by a defined time frame, allows flexibility in responding to rapidly changing territorial dynamics.

Today, it is necessary to rethink the city not exclusively as an organism that consumes the territory but as a system that enhances its potential and emphasizes its vocations, developing in a sustainable and resilient manner.

The PD explicitly outlines strategies, objectives, and actions necessary to pursue an overall framework of socio-economic and infrastructural development, considering environmental, landscape, and cultural resources as essential elements to be valued. So the PD contains the strategic planning of the city and its temporariness adapts to changing conditions and new challenges that emerge over time.

Indeed, strategic planning abandons the idea of addressing and controlling every single detail through comprehensive plans, opting instead for a pragmatic approach that selects specific problems to be solved and identifies the most relevant issues [

22]. This change of perspective in urban planning reflects a growing awareness of the complexity of urban challenges and the need to focus on what matters most. For example, population concentration can lead to challenges such as poverty, unemployment, health issues, education disparities, and more. Therefore, urban management must aim at sustainable development that encompasses the three dimensions of economic, social and environmental [

35]. Indeed, sustainable cities are defined as cities that aim to reduce their environmental impacts, aiming for social welfare and economic development [

36].

Therefore, the PD identifies the areas of greatest interest for urban development, maximizing the effectiveness and impact of planned actions and identifying quantitative and qualitative objectives for sustainable development.

In this sense, the main characteristic of the PD lies in its dual nature: it has both a strategic dimension, defining an overarching vision for the municipal territory and its development, and a more operational aspect. This operational aspect is characterized by the determination of specific objectives for various functional destinations and the identification of areas for urban transformation.

Considering the strategic and the operational interest, the involvement of various stakeholders, both from the public and private sectors, becomes more important. Active participation in the formation of the PD, including by the citizens themselves, becomes necessary to generate dialogue and collaboration, promoting a shared vision of the city’s future. The submission of suggestions and proposals can confirm or implement the city’s strategic planning lines. In addition, citizens’ involvement should not be underestimated in order to enhance the local quality of life in the city, as perceived by residents themselves [

37].

In summary, the process of forming the plan follows the steps defined by strategic plans and includes:

- -

Promotion of the plan

- -

Diagnosis phase

- -

Drafting of the document

The promotion phase marks the beginning of the Plan formation process, with the municipal administration defining the guiding document. The diagnosis phase involves analyzing the territory, identifying strengths and weaknesses, and assessing community needs. The drafting phase includes defining strategies for the city’s future development, setting objectives for each strategy, and outlining actions to achieve those objectives. [

38].

2.1. Study Area

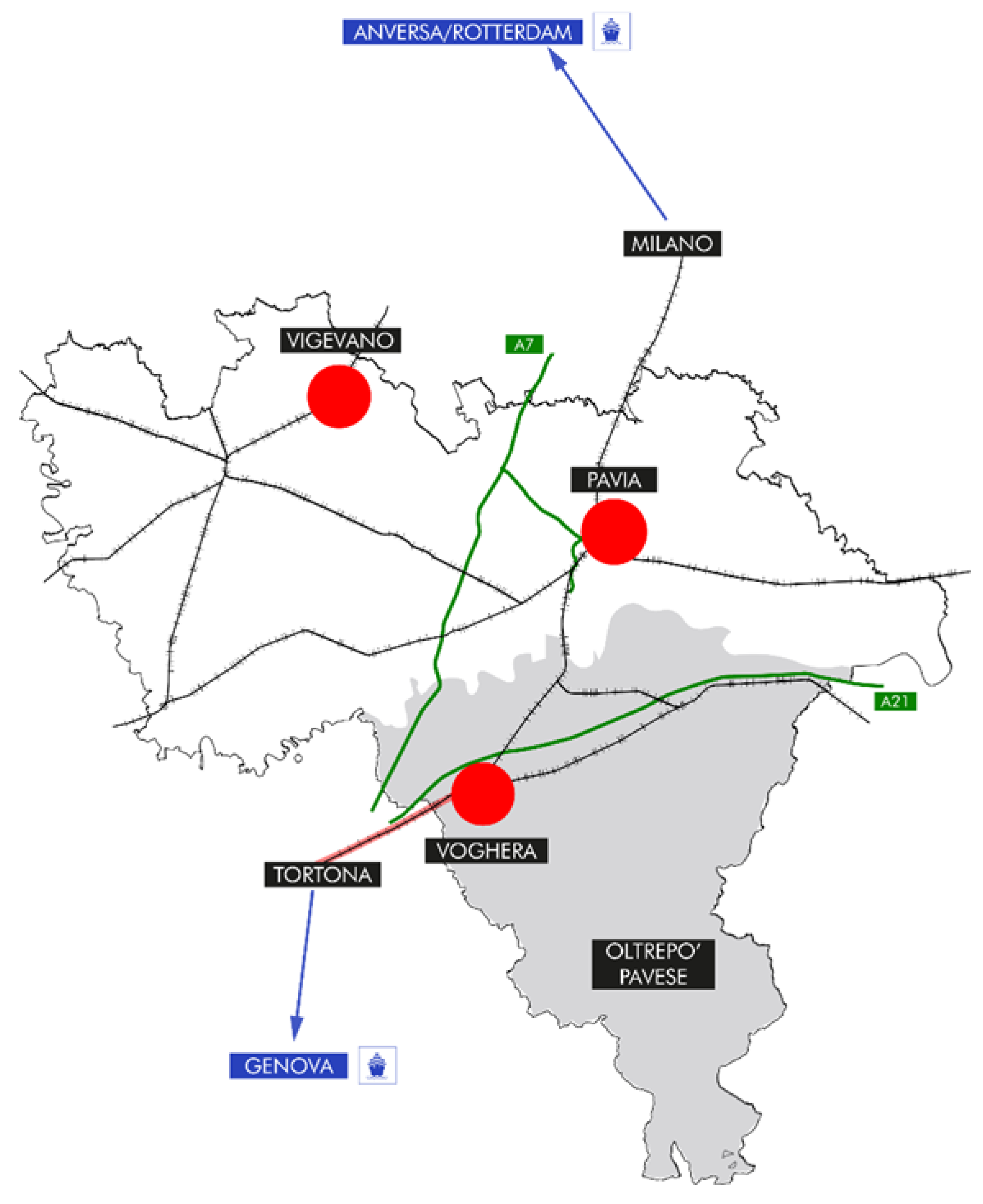

Voghera is a city located in the Province of Pavia (Lombardy region), in the north of Italy (

Figure 1).

The province of Pavia is one of the largest provinces with the highest number of municipalities (189) in the Region [

39].

The city of Voghera represents one of the main centers within the province, together with the provincial capital Pavia and the city of Vigevano. These three cities are recognized as provincial poles of attraction due to their size, location, number of inhabitants and presence of services.

The population density of the three municipalities is higher than the provincial average density, as shown in

Table 1.

Therefore, Pavia, Vigevano and Voghera are the main settlement areas surrounded by smaller municipalities or neighboring towns that rely on them for services, job opportunities, and other infrastructural amenities.

In particular Voghera plays a primary role within the provincial territory, representing the central hub for the entire

Oltrepò Pavese, the southern part of the province, under the Po river. This part of the territory is less urbanized, characterized by small or rural towns, and more anchored to a traditional agricultural development model. For this Voghera represents the leading city in terms of number of inhabitants and per capita income. The municipality covers 63.44 sq.km. and had a population of 39,109 inhabitants in 2021 [

39,

40].

The city serves as a wine-industrial hub and as a center that provides services for all municipalities in the surrounding area, in particular for the Oltrepò.

Additionally, Voghera is located in a strategic position at provincial level. It is a crucial infrastructure node, connecting to the national and international railway networks (

Figure 2). In particular, the transport network connects the city to various important destinations. The city is intersected by several state roads, including SS10 and SS35, and serves as the origin of SS461. Additionally, it is served by the A21 highway (Turin – Piacenza) and the A7 highway (Milan – Genoa).

Voghera’s train station links the city to Milan, Genoa and other Italian and European cities, providing a variety of railway connections.

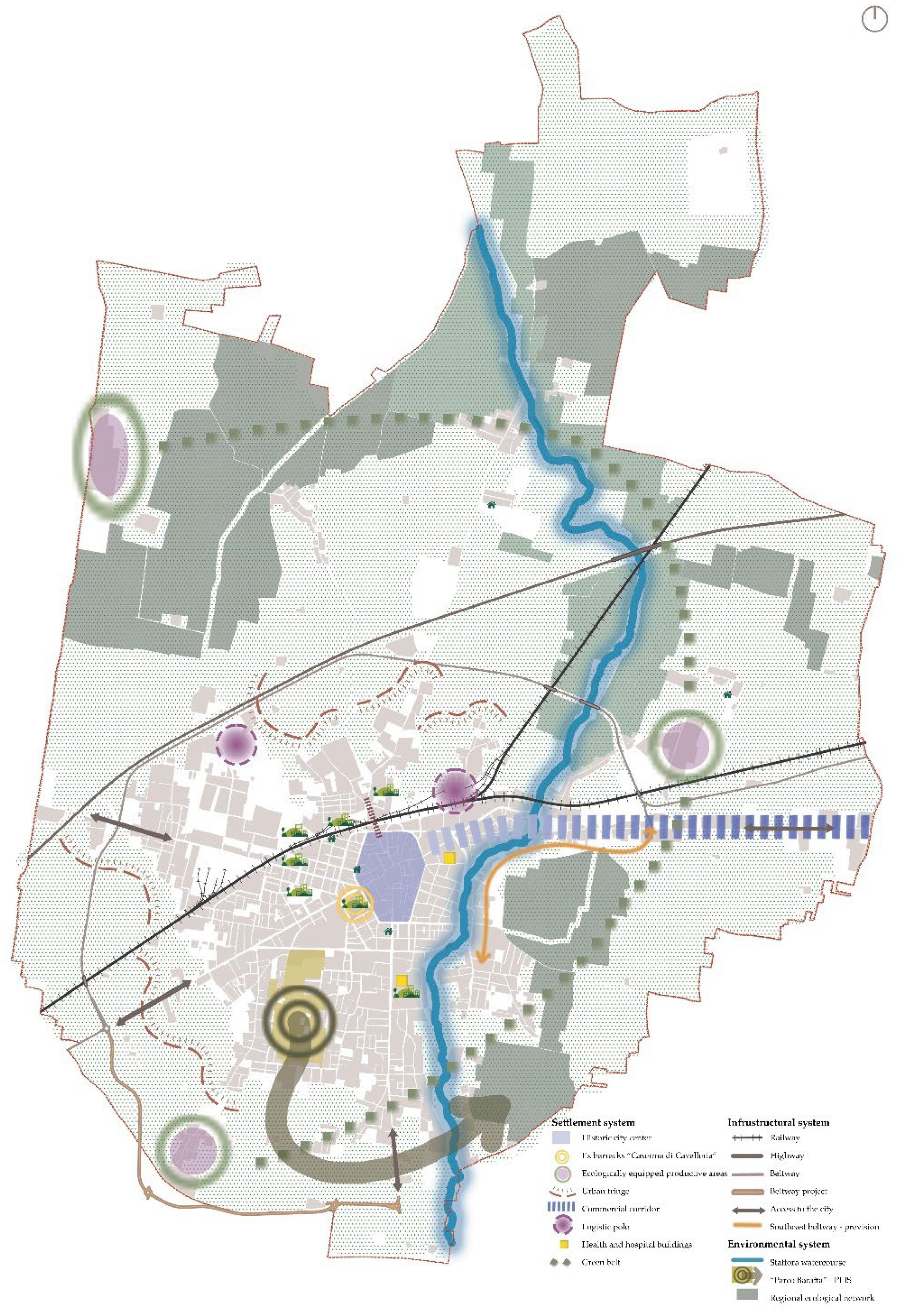

Despite the presence of a large infrastructure system, the territory of the Municipality of Voghera remains predominantly agricultural and natural. From an environmental perspective, the Staffora watercourse holds great importance at both the local and supra-local levels.

From a settlement perspective, the city developed starting from its historic center, characterized by its classic pear-shaped form. The urban area expanded to include autonomous villages Campoferro, Medassino, Torremenapace and Oriolo, that become neighborhoods of the city (

Figure 3).

The city’s development is governed by urban planning. In particular the municipality of Voghera has a PGT, published in the BURL (Regional Official Bulletin) Notices and Competitions Series No. 9 on 27/02/2013, containing acts approved by Municipal Council Resolution No. 61 on 19/12/2012. The urban plan of the city has not been modified for almost 10 years. For this the current PGT proposes a settlement development that is oversized to the current socio-economic situation.

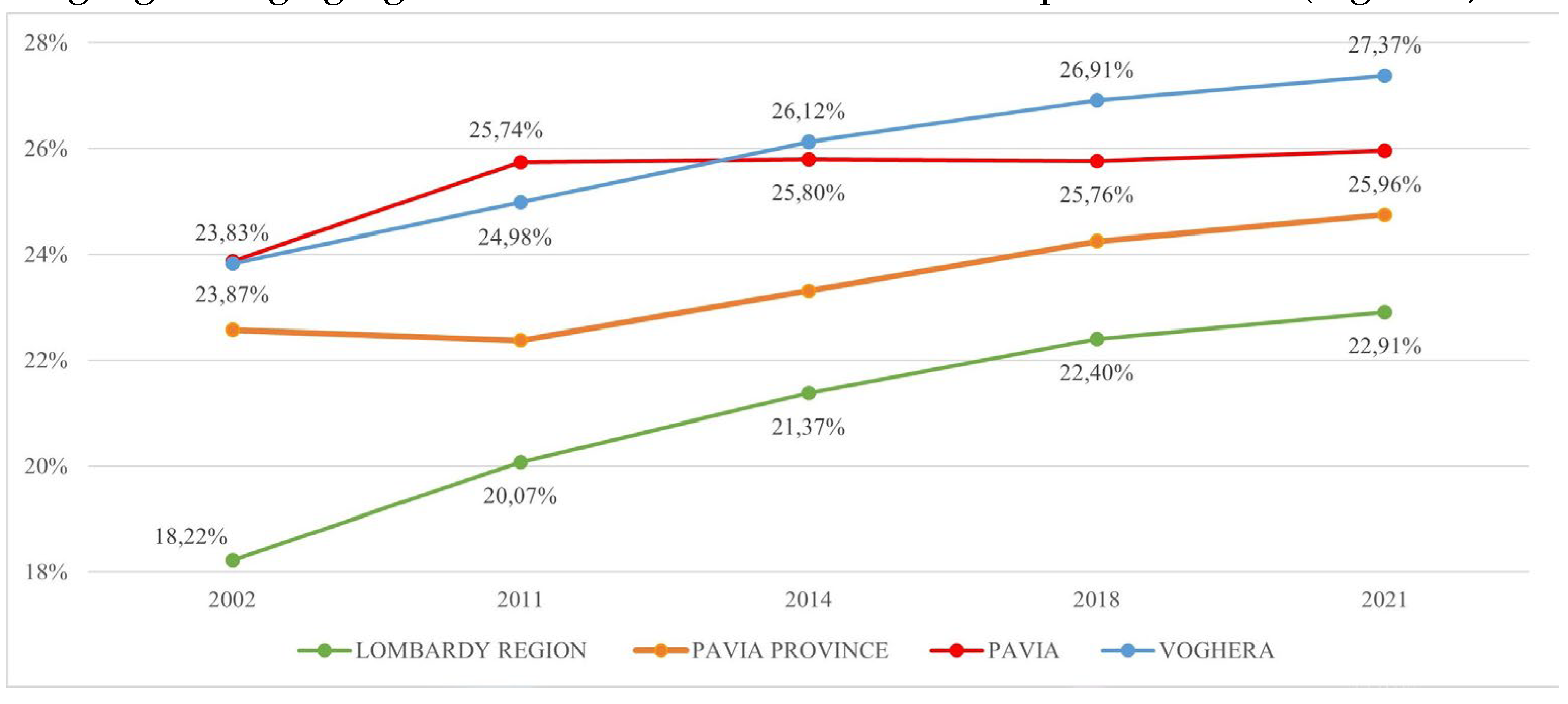

Indeed, in addiction to the poor state of implementation of the PGT, from the analysis of demographic data [

39,

40], the municipal population is decreasing, and, in particular, it is experiencing a growing aging trend, confirmed as well at the supralocal level (

Figure 4).

Furthermore, the presence of empty shops in the city center is increased in these years.

For these reasons, the new PGT has to be measured and focused on the main strategic objectives of the city.

The municipal administration started the procedure for the Variant of the PGT with the approval of the guiding document in 2021. In this way the municipal administration has set out the planning requirements, defining the guidelines for the development and drafting of the variant to the Voghera PGT. The guiding document identifies the main themes to be developed and explored, defining a series of strategic objectives.

Despite the declining social and economic trend, the Municipality’s ambition wants to invest in the existing heritage of the city, revitalize its main characteristics, like the historic center, and increase employment opportunities, due to the primary role in Oltrepò Pavese.

The flexibility in planning and governing the city has become an indispensable paradigm, driven by the well-known consequences of the economic and financial crisis of the years 2008-2010, which led to the need to chase a market that just a few years earlier was booming. The construction sector still faces significant challenges, as in the early 2000s, there was an oversupply compared to real demand, and investments in real estate and finance became increasingly intertwined.

For this reason, it is necessary today to rethink the city not as an organism that consumes the territory but as a system that enhances its potential and highlights its vocations, due to excessive optimism.

3. Strategies and Actions

Through a process that begins with the analysis of the social, economic, historical, and cultural context, the strategic framework involves guidelines and directions from higher-level plans, and, in particular, considers the needs of the city of Voghera.

Lombardy’s legislative innovations, particularly Regional Laws LR 31/2014 and LR 18/2019, highlight the necessity of curbing uncontrolled land consumption and promoting urban regeneration [

41,

42]. These laws underline the limited nature of land resources and emphasize the need to use them sensibly to maintain cities’ functionality in alignment with their context.

Various technical-political meetings were held to define the strategies of PGT. In addition, in order to confirm the city’s needs, a participation process was carried with stakeholders. During public events presenting the new PGT, relevant issues for the future of the city and its inhabitants were addressed, opening a direct dialogue with citizens.

Taking all this into consideration, the fundamental strategies of PGT of Voghera can be summarized as follows:

- I.

Flexibility in territorial planning and governance;

- II.

Reconfiguration of the functions of the historic city center towards a new collective identity, also in functional and architectural qualification;

- III.

Revitalization of local commerce in the historic city center and neighborhoods;

- IV.

Territorial, urban, and building regeneration to enhance existing heritage, both in already used or disused areas and buildings;

- V.

Reduction of soil consumption;

- VI.

Local identity and supra-local role of Voghera as the capital of Oltrepò Pavese;

- VII.

Sustainable mobility and accessibility for all population groups;

- VIII.

City FOR health: the city must become the place where the quality of life is expressed in all its components, starting from health;

- IX.

Definition of principles for the creation of energy communities within the city.

Each strategy envisaged in the new PGT is translated into specific urban actions geographically identified (

Figure 5).

In particular objectives I, V, VII, VIII and IX define sustainable guidelines for the city.

These points emphasize the importance of flexibility, reducing land consumption, sustainable mobility, public health, and the creation of energy communities as fundamental elements for urban sustainability, in line with supra-regulatory objectives.

Achieving sustainability in cities is a complex task that requires concerted efforts across various sectors and levels of governance. The framework provided by the SDGs [

1], for example, offers a comprehensive approach to address the multifaceted challenges of urban sustainability.

Indeed the above objectives can be related to the Goals of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, as shown in

Table 2.

The following part of the text outlines the planned urban actions for the main strategic objectives, aiming at reducing environmental risk factors and improving lifestyle.

Given the rapid pace of societal changes, it is essential to promptly adapt both how citizens experience space and how the city is governed.

Flexibility in urban planning is crucial for cities to quickly adapt to social and economic changes. It involves preserving cultural heritage while adjusting to evolving socio-economic needs. This includes protecting historical sites, revitalizing city centers, and ensuring that building permissions can be adjusted based on public and private requirements. In essence, flexibility enables cities to remain dynamic and responsive to the evolving demands of their inhabitants and businesses.

In practical terms, it can be translated into:

- -

Preservation of historical heritage and territorial attractiveness;

- -

Rediscovery of the city’s landmarks (multifunctionality of the historic center, sequences of collective spaces, and enhancement of urban axes);

- -

Identification of mechanisms allowing for “fluid” transfer of building rights based on public and private needs;

- -

Generalized functional indistinctiveness with charges commensurate with the most valuable function.

The objectives of regeneration and reduction of land consumption are closely interconnected.

Indeed, to limit soil consumption, transformation areas on free areas have been reduced, promoting the regeneration of urbanized area.

The new PD defines potential areas for urban and territorial regeneration. These are areas that are either abandoned or underutilized, whether they are public or private. For each area, a summary sheet has been prepared, identifying the area and the potential/critical aspects to be considered for design development purposes. Each sheet includes:

- -

Identification of the area at both territorial and detailed levels;

- -

Urbanistic parameters and indices;

- -

Director plan proposing a conceptual project outline;

- -

SWOT analysis, identifying the strengths and weaknesses of the area, as well as the opportunities and threats that the implementation of the area may generate externally;

- -

Qualitative performance evaluation assessing the area in relation to specific targets for SDGs selected from the Agenda 2030 [

1].

Regarding sustainable mobility, the objective of the PGT promotes the pedestrianization of the historic center, with the creation of Limited Traffic Zones and new 30 km/h zones, along with the relocation of parking spaces in Piazza Duomo on an annual basis.

In Europe, the necessity of aligning EU mobility with sustainability criteria has been recognized for at least 30 years, marking a crucial milestone towards ecological transition. In Italy, significant strides were made in 2021 with the implementation of these objectives through the Recovery and Resilience Plan (RRP) [

43], propelled by the European Next Generation EU (NGEU) program. Two key pillars of the plan address issues concerning mobility and transportation modes in urban and territorial settings (Mission 2 and Mission 3). Moreover, a Healthy City advocates for the utilization of active and public transportation. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), active transportation encompasses walking, cycling [

44], and other modes of transportation that are both accessible and safe for the majority of users.

Indeed, new cycle paths are identified within the historic center with the inclusion of bike sharing stations near strategic points in the center (i.e., station, castle, ...).

Furthermore, it was considered the opportunity for Voghera to extend the work of the international healthy cities movement that originated in the European offices of the WHO [

31].

Not only the idea of a healthy city is not merely an idealistic, fictional one, but it is also a practical and implementable notion with relatively realistic dimensions [

45].

Implementing new effective strategies for making Voghera a “city for health” involves a multidisciplinary approach that considers at least three main fields of action. The latter are: air quality, lifestyle, and urban green spaces. In particular, the Staffora watercourse has been detected as a fundamental environmental resource to be enhanced in terms of healhty living conditions. Healthy proposals for enhancing the Staffora watercourse consider three key points of attraction:

Greeway: The development of a greenway along the stream offers residents and visitors a scenic route for walking, cycling, and enjoying nature. This initiative aims to promote eco-friendly transportation and encourage outdoor activities by providing accessible recreational opportunities in a natural setting.

Riqualification of the former psychiatric hospital: Potential revitalization of the hospital site to repurpose the area into a cultural or recreational space that complements the surrounding natural environment. The aim is to preserve historical elements while providing new amenities for the community. A similar redevelopment could include features supporting public health, such as community gardens, outdoor fitness areas, or educational spaces promoting mental health awareness.

Strengthening of the existing private activities that exploit the agricultural capital and that could incorporate health-oriented activities like horseback riding, outdoor yoga classes, or organic farming practices, promoting active and healthy lifestyles for both residents and tourists (such as, in example the Cowboys’ Guest Ranch).

The formulation of new actions is particularly focused on enhancing citizens’ use of the Supralocal Park with Municipal Interest (PLIS), supporting knowledge of the local territory, and safeguarding biodiversity. These proposed actions are considered reversible and non-invasive, such as using prefabricated containers. This method emphasizes sustainability and minimal disruption to the natural ecosystem while encouraging community engagement while creating a balance between progress conservation.

Energy Communities are a significant element of the energy transition towards low-carbon, where citizens own and participate in the production of energy, including renewable energy, or in energy efficiency projects; they focus on benefits for their members and the local community, financing social programmes, creating local employment local employment, addressing various community development needs and combating energy poverty. Similar initiatives not only reduce pollution and greenhouse gas emissions but also foster cleaner air and a more sustainable living environment. Moreover, they can empower local residents to take control of their energy consumption, leading to greater awareness of environmental issues and healthier lifestyle within cities.

The consumption of communal houses managed directly by the municipality was then analyzed. Clusters were defined as possible pilot projects that could be implemented. These clusters can either manage the energy produced internally or exchange it between them.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The strategic nature of a plan relies heavily on the boundary conditions, i.e., the socio-economic context, the environmental situation and in general the overall situation that exists in a given period of time.

Strategic planning involves broad and diverse participation from multiple levels of governance and sectors of society, including the public, economic entities, and civil society during planning, decision-making, and implementation processes. It aims to create robust, long-term visions and strategies while considering various power structures, uncertainties, and competing values. The goal is to influence and manage spatial changes effectively. Strategic spatial planning isn’t merely a reaction to external forces but an active force in driving change [

5].

Consequently, the principle of plan flexibility, i.e., the plan’s ability to constantly adapt dynamically as context conditions change, without altering its reliability over time, is of particular importance.

In this regard, it is useful to establish general rules that identify performance objectives or targets. The approach relies on defining fewer regulatory constraints related to compatible land uses, temporary uses, and a time-scanned functional overlap [

46].

Considering sustainable development and the SDGs, development policies must restrict resource usage, reduce pollution, and protect the environment and people’s health. Therefore, urban planning must be careful of environmental consequences caused by potential transformations [

47].

The work on Voghera’s PD led to the proposal of new regulatory schemes, particularly in defining transformation areas.

The transformation areas represent a strategic interest as they constitute the key areas where the local administration intends to concentrate efforts for urban redevelopment and development. These zones are identified as fundamental for improving the livability and attractiveness of the city, promoting economic and social growth, as well as meeting the needs of the local community.

To delineate transformation areas, size criteria were applied, with actions categorized as strategic falling under the PD, including areas:

- -

for residential functions with a size greater than 5,000 sqm.

- -

for commercial functions with a size greater than 6,000 sqm.

- -

for manufacturing functions with a size greater than 10,000 sqm

To implement the flexibility, for each Transformation Area, specific sheets will be created that include information on the Land Use Index (It), the Coverage Ratio (Rc), the Biotope Area parameter (BAF) to assess environmental performance [

48], a list of the Public Works required for the intervention, a SWOT analysis of the area and a list of non-permitted functions.

Among the strategic areas, all abandoned or disused areas that may be subject to urban regeneration were also included. All regeneration areas, in addition to reclaiming underutilized spaces, must contribute to the realization of specific public works.

LR 18/2019 [

42] has made regeneration an essential theme for contemporary cities. However, at the same time, it has proposed significant fiscal incentives, reduction of charges, and other measures to encourage private intervention in areas where the overall cost of the project is higher than vacant areas.

The introduction of volumetric incentives within the local urban plan promotes all building and urban actions that enhance the city, both functionally and qualitatively. In particular, it promotes urban regeneration and sustainable development.

These incentives allow developers to obtain additional benefits, such as increased building volume or greater building height, in exchange for certain contributions or improvements to the community or the surrounding environment. For example, within the consolidated fabric, premium indices have been provided for any actions aimed at incorporating collective functions, improving energy quality, and the aesthetic quality of the area.

Moreover, it is possible to foresee the application of such incentives within strategic regeneration areas.

Strategic spatial planning is therefore multi-sectoral planning. The technical component and political decision-making, which assume a different weight depending on the system of government and the delegation of responsibility in effect, are mediated [

49].

In the specific case of Voghera, the definition of strategies aimed to translate the political program into practical actions with geographical boundaries. In urban studies, it is well known that some policies overcome specific spatial definitions and, moreover, in HC promotion some topics can be spatially defined while others depend on the life-style that citizen choose. In the end, with the Voghera PD the authors wanted to highlight that the nature of urban decisions born in a specific territorial definition, but they have a wider view and that interfere with many aspects of human life.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.P., M.S. and E.V.; methodology, R.D.L. and M.S.; investigation, R.D.L., C.P., M.S. and E.V.; resources, R.D.L. and M.S.; data curation, R.D.L. and M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S. and E.V.; writing—review and editing, R.D.L., C.P., M.S. and E.V.; supervision, R.D.L.; funding acquisition, R.D.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work derives from a scientific consultancy between Municipality of Voghera and Department of Civil Engineering and Architecture, University of Pavia (the group composed by the authors) aimed to develop strategies and actions for the new PGT of Voghera. The consultancy ended in June 2023.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- UN, The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals.

- Hersperger, A. M.; Bürgi, M.; Wende, W.; Bacău, S.; & Grădinaru, S. R. ; & Grădinaru, S. R., Does landscape play a role in strategic spatial planning of European urban regions?, Landscape and Urban Planning, 2020, 194, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Albrechts, L.; Healey, P.; Kunzmann, K. R. Strategic spatial planning and regional governance in Europe, Journal of the American Planning Association, 2003, 69, 113–129. 69.

- Albrechts, L.; Balducci, A.; Hillier, J. Situated practices of strategic planning: an international perspective. Routledge: London, England, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Albrechts, L.; Balducci, A. ; Practicing Strategic Planning: In Search of Critical Features to Explain the Strategic Character of Plans, disP – The Planning Review, 2013, 49, 16-27. 49.

- Martinelli, F. , La pianificazione strategica in Italia ed in Europa. Metodologie ed esiti a confronto, Franco Angeli: Milano, Italia, 2005.

- Balducci, A.; Fedeli, V. ; Pasqui, G, Strategic Planning for Contemporary Urban Regions, Routledge: London, UK, 2011.

- Gibelli, M. C. , Piano strategico e Pianificazione strategica: un’integrazione necessaria, Archivio di studi urbani e regionali, 2007, pp. 211–222.

- Mazza, L. , Ordine e cambiamento, regola e strategia, in Piano, progetti, strategie, Franco Angeli: Milano, Italia, 2004, pp. 29–48.

- Dimitrou, H.; Thomson, R. , Strategic Planning for Regional Development in the UK, Routledge: London, UK, 2007.

- Salet, W. ; Faludi, A, Three Approaches to Strategic Spatial Planning in The Revival of Strategic Spatial Planning, Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences: Amsterdam, 2000, pp. 1–10.

- Sartorio, S.F. , Strategic Spatial Planning, disP Journal, 2005, 162, 26–40. 162.

- Vasilevska, L. & Vasić, M, Strategic planning as a regional development policy mechanism: European context. Spatium, 2009, 21, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, P. ; The Revival of Strategic Spatial Planning in Europe, in Making Strategic Spatial Plans: Innovation in Europe, Healey, P., Khakee, A., Motte, A. and Needham, B., UCL Press: London, 1997, pp. 3–19.

- Nadin, V. , Spatial Planning and EU Competences in Spatial Planning and Spatial Development in Europe - Parallel or Converging Tracks? of the European Council of Town Planners Conference, 1 December 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, E. , Tobias, S. ; Hersperger, A., Can strategic spatial planning contribute to land degradation reduction in urban regions? State of the art and future research, Sustainability, 2018, 10, 949. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe, European landscape convention, 2000 Firenze, Italy.

- Steiner, F. , An ecological approach to landscape planning, Island Press: Washington, USA, 2008.

- Tanese, A.; Di Filippo, E.; Rennie, R. , La pianificazione strategica per lo sviluppo dei territori, Rubbettino: Soveria Mannelli, Italy, 2006.

- Law, n. 1150 of 1942, Norme per la disciplina dell’edilizia e dell’urbanistica, Gazzetta Ufficiale n. 244, 1942, Titolo II.

- Cappuccitti, A. Le diverse “velocità” del Piano urbanistico comunale e il Piano strutturale, Urbanistica Informazioni, 2006, 210.

- Novarina, G.; Zepf, M. , Territorial Planning in Europe: New concepts, new experiences, disP - The Planning Review, 2009, 45, 18–27.

- Regional Law of Lombardy, n. 12 of 2005, Legge per il governo del territorio, BURL n. 11, 2005, art. 6-14.

- INU – National Institute of Urbanism, XXI Congresso, La nuova legge urbanistica: i principi e le regole, Urbanistica Informazioni supplemento n. 141, 1995.

- Hancock, T. , Health, human development and the community ecosystem: three ecological models. Health Promo. Int. 1993, 8, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO, International Health Conference - Preamble to the WHO Constitution, 19--22 June 1946. New York: WHO. Available online: http://www.who.int/suggestions/faq/en/.

- WHO, The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion, 1986. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/data/ assets/pdf_file/0004/129532/Ottawa_Charter.pdf.

- WHO Regional Office for Europe, Health2020: Policy Framework and Strategy. EUR/RC62/8. WHO: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2012.

- Hancock, T. Beyond health care: from public health policy to healthy public policy. Proceedings of a working conference on Healthy public policy, Can J Public Health, 1985, 76, 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Duhl, L.J. , The Healthy city: Its function and its future, Health Promo. , 1986, 1, 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Duhl, L.; Hancock, T. , Promoting health in the urban context (WHO Healthy Cities Papers, No. 1). PADL Publishers: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1988.

- Batty, M. , Cities and complexity: understanding cities with cellular automata, agent-based models and fractals, The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, 2005.

- Batty, M.; Marshall, S. , Centenary paper: The evolution of cities: Geddes, Abercrombie and the new physicalism, Town Planning Review, 2009, 80, 551–574. 80.

- UN. Health as the Pulse of the New Urban Agenda: United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development. Quito: United Nations. 2016. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/250367/9789241511445-eng.pdf.

- Li, W.; Yi, P. Assessment of city sustainability—Coupling coordinated development among economy, society and environment, J. Clean. Prod., 2020, 256, 120453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santa, S.L.B.; Dias, F.T.; Soares, T.C.; Souza e Silva, R.S.M.d.; Basil, D.G.; Andrade Guerra, J.B.S.O.d. Measurement Model of Healthy and Sustainable Cities: The Perception Regarding the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability, 2023, 15, 15004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.-M.; Peng, H.-H. A Fuzzy Multi-Criteria Evaluation Framework for Urban Sustainable Development, Mathematics 2020, 8, 330. 8.

- Castello, C. , Il piano strategico, Liuc papers, 2003, 120.

- ISTAT. Istituto Nazionale di Statistica. Censimento Permanente Popolazione e Abitazioni. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/censimenti-permanenti/popolazione-e-abitazioni (accessed on June 2022).

- Municipality of Voghera, Censimento della popolazione, 2021, Voghera (unpublished data).

- Regional Law of Lombardy, n. 31 of 2014, Disposizioni per la riduzione del consumo di suolo e per la riqualificazione del suolo degradato, BURL n. 49, 2014.

- Regional Law of Lombardy, n. 18 of 2019, Misure di semplificazione e incentivazione per la rigenerazione urbana e territoriale, nonché per il recupero del patrimonio edilizio esistente., BURL n. 48, 2019.

- MEF, The National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), 2021. Available online: https://www.mef.gov.it/en/focus/The-National-Recovery-and-Resilience-Plan-NRRP/.

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. (2022). Walking and cycling: latest evidence to support policy-making and practice. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/354589. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Papoli Yazdi, M. H.; Rajabi Sanajerdi, H. , The theory of urban and surrounding, SAMT Publication: Tehran, Iran, 2010.

- De Lotto, R. , Elementi della città flessibile, Maggiolini editore: Italy 2022, p.67.

- Sugoni, G.; Assumma, V.; Bottero, M.C.; Mondini, G. , Development of a Decision-Making Model to Support the Strategic Environmental Assessment for the Revision of the Municipal Plan of Turin (Italy). Land, 2023, 12, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senate Department for the Environment. Transport and Climate Protection BAF–Biotope Area Factor. Available online: https://www.berlin.de/sen/uvk/en/nature-and-green/landscape-planning/baf-biotopearea-factor/.

- Abis, E.; Garau, C. , (2016) An Assessment of the Effectiveness of Strategic Spatial Planning: A Study of Sardinian Municipalities, European Planning Studies 2016, 24, 139-162. 24.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).