1. Introduction

Pragmatic randomized controlled trials differ from explanatory randomized controlled trials in that the objective of pragmatic trials is to evaluate efficacy, usually in the context of usual patient care, whereas explanatory trials seek to assess the efficacy of an intervention, often under controlled conditions[

1]. Despite observational studies being commonly used to approximate the effectiveness of an intervention, pragmatic trials are better at reliably answering questions of effectiveness since they can minimize confounding through randomization [

2].

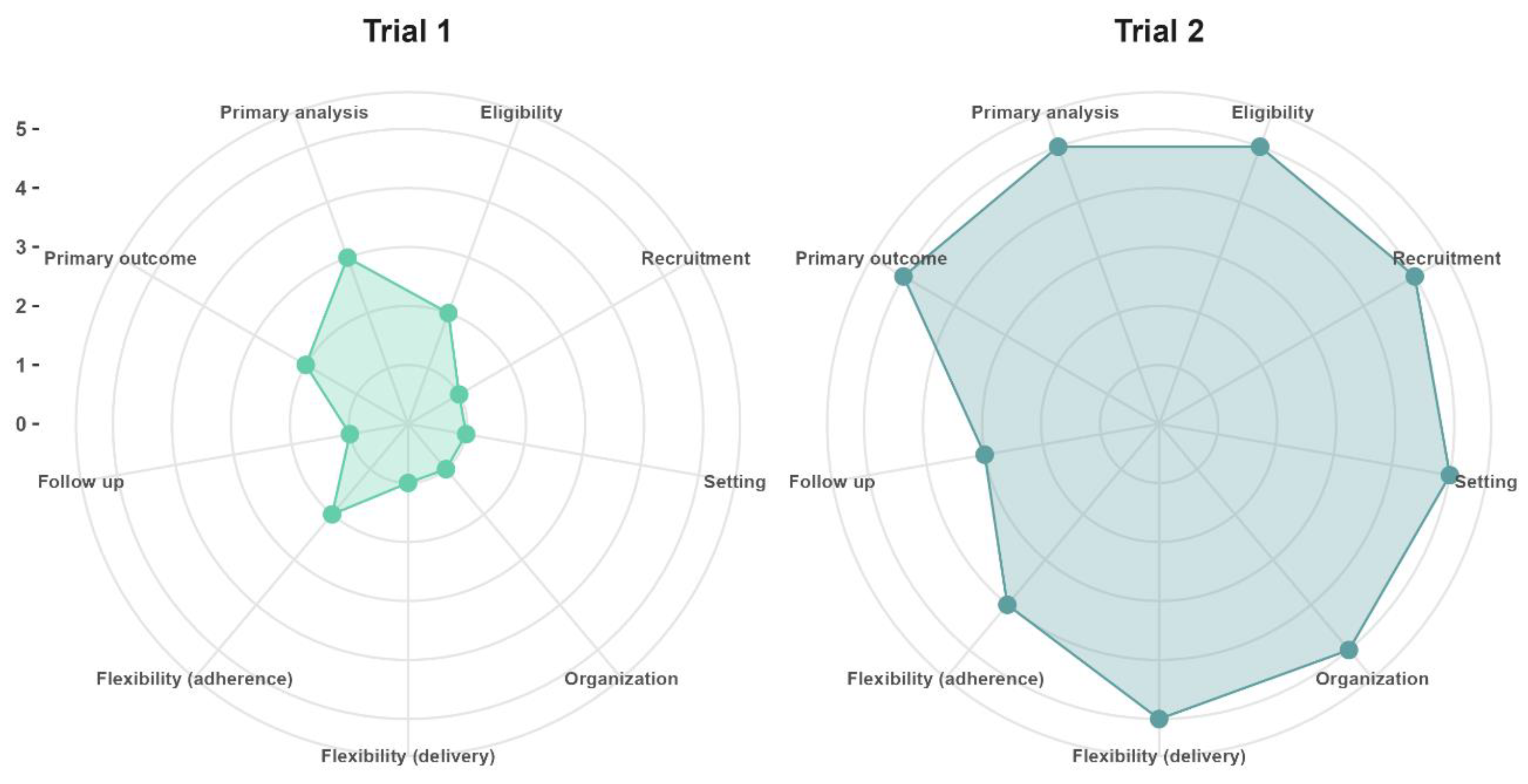

Although the distinction between explanatory trials and pragmatic trials could suggest there exists a dichotomy between these types of trials, in practice clinical trials can incorporate both explanatory and pragmatic elements. Therefore, the PRECIS-2 tool [

3] aids the evaluation and design of elements in the pragmatic-explanatory continuum of trials. In

Figure 1, we provide an example of two different hypothetical trials in aging research with varying degrees of pragmatism, with an explanation of the design choices and PRECIS-2 scores provided in the

Supplementary Materials.

Figure 1 Trial 1 (mean PRECIS-2 score = 1.6) refers to the situation in which a primary healthcare practitioner who is also a researcher at an academic research center wants to assess if a new drug is safe and capable of preventing secondary cardiovascular events in older adults after recovering from acute myocardial infarction, whereas trial 2 (mean PRECIS-2 = 4.7) was designed after stakeholders commissioned a study to evaluate if implementing a new drug in all primary healthcare clinics of their jurisdiction will prevent secondary cardiovascular events under real-world conditions.

Pragmatic randomized controlled trials are increasingly being used in the aging research field due to the need of obtaining high-quality real-world evidence for interventions in the elderly who tend to have low representation in trials [

4] .Additionally, geriatric interventions are often complex in nature, reason why pragmatic trials are useful designs for the evaluation of interventions [

5] .Furthermore, pragmatic trials allow investigations in the context of regular clinical practice, with the advantages of being more accessible, less resource intensive, and placing minimal additional burden on participants [

6].

Despite the multiple advantages of pragmatic trials for the obtention of evidence for complex interventions in the elderly, there are several choices in the design of pragmatic trials that have important implications on the ability to obtain high quality evidence, while minimizing costs. Guidance on such design choices is provided by the GetReal trial tool [

7,

8]. Despite the existence of such tools, guidance, and explanations on the rationale for the design and analysis of pragmatic trials from a biostatistician’s perspective remains scarce. Therefore, we sought to review the statistical considerations for the design and analysis of pragmatic trials, including available resources for the sample size calculation and analysis of pragmatic trials. In this review we only cover statistical considerations from a frequentist approach.

2. Study unit and Randomization

Although the individuals are the ultimate unit of interest in both explanatory trials and pragmatic trials, clusters are commonly used in pragmatic trials as the unit of randomization. A cluster refers to any level of aggrupation of individuals (i.e., patients who receive care from one single practitioner, a clinic or hospital, a jurisdiction, etc.). Cluster randomized trials allow to estimate the broad population effects of an intervention [

9] . Randomization by clusters is also attractive in the context of pragmatic trials since they can allow to overcome logistical challenges of interventions delivered at very large number of patients, among other reasons.

A parallel cluster study in which different groups of individuals are assigned to receive an intervention or the comparator (i.e., placebo) without random assignment would be considered a quasi-experimental study and would have many sources of latent potential confounding. Fortunately, different randomization strategies have been envisioned and successfully applied: parallel randomized clusters, parallel randomized clusters with a baseline period, and stepped wedge cluster randomized studies [

10].

From a causal research perspective, the reason randomization is important in a conventional individual-level randomized study is that it allows for comparability of the prognosis of participants allocated to treatment groups [

11]. Confounders are said to be randomly distributed between groups. Thus, the group to which participants are assigned serves as an instrumental variable [

12] that can be used to approximate the effect of an intervention (assuming compliance with it).This is the principle of the intention-to-treat [

13] and the reason why the method of analysis should be Randomization-Based Inference [

14], meaning that the principle of intention-to-treat should be followed. In this approach, subjects are evaluated considering the original group to which they were randomly assigned, and data elimination due to lack of information, treatment changes, use of other medications, or lack of adherence should be strongly avoided[

3,

15].

In pragmatic clinical trials, cluster randomization is recommended over individual randomization. Therefore, the number of clusters or the number of subjects per cluster should be determined a priori [

16]. It is common to assume an equal number of subjects in each cluster (cluster size), leading to statistical analysis using hypothesis testing for comparison of means or proportions, depending on the type of dependent variable chosen. However, when cluster sizes are not equitable, the use of mixed effects models (also called random effects models) or generalized estimating equations (GEE) is suggested[

17].

The evaluation of missing data should beimperative to detect the presence of non-random patterns of missing data. The use of imputation techniques may or may not be warranted, but it is imperative to assess if missing data exhibit a specific pattern, as non-random patterns could bias the interpretation of results [

18].

3. The Dependent Variable

The type of dependent variable in pragmatic clinical trials will guide the statistical treatment, i.e., whether the variable is a continuous quantitative outcome or a dichotomous or ordinal qualitative outcome. The choice of outcome variable should be made with caution because a variable that requires strict follow-up or subsequent clinic or hospital visits could interfere with "usual care" if the visit frequency differs from routine clinical care [

15]. The chosen outcome variable should align with the pragmatic concept, reflecting usual clinical practice. Therefore, a continuous outcome (reduction in HbA1c, decrease in serum lipids, fewer hospitalization days) can be commonly used to evaluate intervention effectiveness, as can a dichotomous outcome (achieving <7 units of HbA1c, having an LDL <150 mg/dL, recovery from illness)[

15]. It must be ensured that the choice of outcome represents the objective for which the usual treatment is utilized.

The most common study designs in pragmatic clinical trials or cluster trials are parallel designs. In these designs, the use of independent statistical tests (two-sample t-test, ANOVA, χ² test) is standard practice, while in crossover designs or designs where matching between clusters or individuals has been used, paired analyses (paired t-test, Friedman test, McNemar test) should be employed [

17].

Since maintaining homogeneous cluster sizes is not always feasible, even in explanatory cluster-crossover trials [

19], the use of mixed models and GEE is highly recommended. However, their use is not as widespread as expected, leading to heterogeneity in the types of statistical analyses[

20]. Mixed effects models and GEE are longitudinal data analyses that allow estimation of the effect of an intervention on the outcome, but they differ in how they generate an estimation of an effect.

Mixed models allow for modeling the effects of fixed factors, which assume a constant effect, and random factors, which presuppose variability among each subject. They are used when estimating the effect of an intervention considering the heterogeneity among the clusters to which subjects belong, and this heterogeneity can be modeled through a probability distribution. Estimates generated in mixed models are termed conditional estimates as the model provides a conditional estimate of the outcome given by the covariates or random effects[

21,

22].

4. Types of Statistical Model for Pragmatics Designs

Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) allow for estimating the average effect of a predictor variable across the entire study population, hence termed population average models or marginal models. GEE estimates the intervention effect averaged across all clusters, making them suitable for estimating the effect of a predictor variable when the effects of random factors are not of interest to the researcher. Therefore, GEE do not require assumptions about the distribution of data but necessitate larger sample sizes for precise estimations[

22,

23].

The use of mixed models is more widespread for cluster randomized trials due to their ability to model different random effects. In

Table 1, the main mixed models are presented, considering the intercept or slope as a random factor in the model. A brief description of their use in CRT, as well as the statistical model and its code in R software, are provided, considering the dependent variable as dichotomous, following previous recommendations regarding the use of dichotomous variables in pragmatic studies [

24].

It is important to consider that the type of dependent variable, whether quantitative or dichotomous, can be modeled using linear mixed models (LMM) or generalized linear mixed models (GLMM). GLMMs, which depend on the distribution of the dependent variable, are modeled with different link functions (binomial, logit, Poisson, log-log, etc.). Regardless of the data modeling approach, it is important to verify the statistical assumptions of the models and compare between models using information criteria (AIC, BIC) when constructing models incorporating various variables [

21].

The way variability in modeled in the experiment can take various forms. In thismini-review, we provide methodological guidance for the statistical design of a pragmatic clinical trial. Therefore, we suggest readers explore forums and delve into deeper literature concerning the application of such models across different software platforms. Additionally, it is important to understand the requirements for data capture in data matrices, which differ from the conventional data matrices format where each row represents a different subject. Li F et al. [

14] provide a comprehensive compilation of packages for developing such models in software like R, Stata, and SAS.

5. Sample Size Estimation

The sample size calculation for pragmatic studies will depend on the chosen study designs, specificallywhether randomization of interventions is performed at the individual or cluster level. Sample size calculations have been described in multiple publications, and online calculators are available to estimate the required number of subjects based on whether the dependent variable is continuous or dichotomous [

25]. However, in the case of cluster-based studies, an adjustment must be made for a correction factor known as the "variance inflation ratio" or "design effect." This factor represents the multiplier by which the calculated sample size for individual randomization should be multiplied [

19]. This design effect is calculated as follows:

, where

is the number of subjects per cluster and ρ is the intracluster correlation coefficient (

), defined as the ratio of the variance of means between clusters (

) to the sum of the variance of subjects within the same cluster (

) and between clusters [

26]. The calculation of the design effect in designs comparing two means uses ρ, while in designs comparing two proportions, the calculation of the cluster concordance index (κ) is employed [

27]. It is important to mention that the calculation of the design effect assumes a homogeneous distribution of the number of subjects per cluster. Therefore, it may be considered to adjust the sample size calculation assuming unequal cluster sizes through the calculation of the "coefficient of variation of cluster size" (cv), which can be done by various methods explained in depth by Eldridge SM et al. [

19].

As mentioned in the "dependent variable" section, equitable cluster sizes are not always estimated in pragmatic studies, and there is a desire to control for the effect of variation within clusters and between subjects. Hence, mixed models or GEE are used, although these models serve to describe an effect size based on a different coefficient B different from the classic effect sizes with mean or proportion differences, which are typically employed in classic sample size calculations. These more complex statistical models can be used even if the sample size calculation was based on a difference in statistics; however, it is preferable to calculate the sample size based on the estimation of a conditional (LMM-GLMM) or marginal (GEE) model. Therefore, the design effect should also be specific to these models. Li F et al. [

14]compiles various packages for sample size calculation in specific situations for different software (R, SAS, STATA) for sample size calculations for various types of CRT.On the other hand, Hemming K et al. [

28] developed an online app for calculating sample sizes and statistical power for various CRT designs.In

Table 2 you will find links to online calculators for sample size calculations for various situations.

6. Multi-Arms Sample Size

Throughout the development of this paper, we have emphasized that the aim of pragmatic trials is to test interventions in real-world situations. In some cases, theremay be more than one usual care, multiple promising new treatments, or various waysto implement an intervention. This is where multi-arms studies become relevant. The most common form of analysis for multi-arms studies involves comparing means between 3 or more groups using a general linear model (ANOVA family). For such comparisons, sample size calculation is done considering an expected effect size (η

2 or Cohen's f) in the ANOVA model, statistical power (1-β), the alpha error probability (confidence level), and the number of groups to be included in the study [

28]. However, this methodology estimates the sample size considering only the null hypothesis of the test (no group mean difference), so it does not consider multiple group comparisons (post hoc tests), which ultimately results in a lower statistical power of this calculation, leading to a higher risk of type 2 error. Adjusting the alpha error using the Holm-Bonferroni method (α / number of pairwise comparisons) can help provide a better estimate of the sample size.As previously mentioned, it is more common for the outcome used in usual care to be a dichotomous rather thanquantitative, therefore, comparing3 or more proportions can be a pragmatic outcome. In this scenario, sample size calculation can be performedusing formulas for comparing two proportions and adjusting the alpha error using the Holm-Bonferroni method. Grayling MJ et al. [

29]. developed a sample size calculator for multi-arm clinical trials for various types of variables and sequences andemploying different multiple comparison correction methods.Additionally, it is important to note that adjustment for the design effect should also be considered if the sample size will be for a CRT, once the multi-arm sample size is calculated.

The so-called "Adjustment for losses" used in sample size calculations must be justified to avoid unnecessarily exposing more subjects to risk, since in pragmatic nature, subjects should be included in the analysis regardless of their follow-up losses or incomplete data.Finally, since prior data on effect sizes and, in the case of CRT, intracluster correlation, are required to perform any sample size calculation, it is highly recommended that researchers report these statistics obtained in their study samples to assist future researchers in scaffolding their own sample size calculations. Otherwise, they may require conducting pilot studies, which would entail additional effort and expense to the pragmatic clinical trial itself.

7. Secondary or Ancillary Analyses

The population included in pragmatic studies can be very heterogeneous, which can lead to the desire to compare the results of the primary outcome among subgroups of the sample, thereby identifying in which population characteristics the intervention may be more effective [

30]. This practice is common in secondary analyses of clinical trials where secondary variables are sought to be evaluated beyond the original protocol due to possible hypotheses obtained during the main study or attempting to evaluate effects among participant subgroups [

31]. The issue with secondary or subgroup analyses is that they generally have fewer observations and hence less statistical power, increasing the risk of not detecting differences (type 2 error) or detecting them only by chance (type 1 error)[

32].

Sample size calculation allows us to identify the minimum number of subjects needed to achieve sufficient statistical power to detect a difference between study groups on the primary outcome. Therefore, the statistical inferences we make in a study regarding secondary outcomes may be biased if a sample size was not calculated a priori for such comparison [

15]. It is under this premise that secondary analyses of clinical trials should be approached with caution, and the possibility of committing type 1 and 2 errors should be considered when a proper sample size calculation was not performed or when subgroup comparisons are overused [

30]. If secondary analyses of a pragmatic clinical trial are to be conducted, efforts should prioritize the evaluation of outcomes relevant to clinical practice,while the use of surrogate markers is discouraged [

15].

While the primary focus of a pragmatic clinical trial is always on evaluating the effectiveness of an intervention in real-world settings, it is important to note that information on the safety of interventions is also collected[

33]. Greater care must be taken regarding the method of safety data collection, as an excessive burden on healthcare providers can compromise the pragmatism of the study. It is suggested to use a combined strategy of data collection present in clinical records, as well as case-form reports for serious adverse events [

33]. In geriatrics, there is often a scarcity of studies dedicated to assessing the safety of medications in older adults, highlighting the imperative need for acquiring real-world evidence [

34].

8. Conclusions

In this review, we have covered relevant aspects for the design and statistical analysis of pragmatic randomized controlled trials from a frequentist approach. The methodological design, the distribution of the dependent variable, the correct calculation of sample size, and the choice of the number of secondary analyses to be carried out are important statistical considerations that, alongside other important choices in the design of pragmatic trials,are of utmost importance for the validity of the estimation of the effect of interventions in the elderly, delivered in real-world conditions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K.G. and J.M.G.; methodology, A.K.G. and J.M.G.; software, J.M.G.; validation, A.K.G. and J.M.G; writing—original draft preparation, A.K.G., J.M.G and L.A.F.U; writing—review and editing, A.K.G., J.M.G, J.A.G.D. and L.A.F.U.; visualization, J.A.G.D. and J.M.G; supervision, A.K.G. and J.M.G; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lurie, J. D.; Morgan, T. S. Pros and Cons of Pragmatic Clinical Trials. J Comp Eff Res 2013, 2, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuidgeest, M. G. P.; Goetz, I.; Groenwold, R. H. H.; Irving, E.; van Thiel, G. J. M. W.; Grobbee, D. E. Series: Pragmatic Trials and Real World Evidence: Paper 1. Introduction. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2017, 88, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loudon, K.; Treweek, S.; Sullivan, F.; Donnan, P.; Thorpe, K. E.; Zwarenstein, M. The PRECIS-2 Tool: Designing Trials That Are Fit for Purpose. BMJ 2015, 350 (may08 1), h2147–h2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Gonzalez, C. A.; Cunha, M. T.; Menjak, I. B. Bridging Research Gaps in Geriatric Oncology: Unraveling the Potential of Pragmatic Clinical Trials. Current Opinion in Supportive & Palliative Care, 2024; 18, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heim, N.; van Stel, H. F.; Ettema, R. G.; van der Mast, R. C.; Inouye, S. K.; Schuurmans, M. J. HELP! Problems in Executing a Pragmatic, Randomized, Stepped Wedge Trial on the Hospital Elder Life Program to Prevent Delirium in Older Patients. Trials 2017, 18, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nipp, R. D.; Yao, N. (Aaron); Lowenstein, L. M.; Buckner, J. C.; Parker, I. R.; Gajra, A.; Morrison, V. A.; Dale, W.; Ballman, K. V. Pragmatic Study Designs for Older Adults with Cancer: Report from the U13 Conference. Journal of Geriatric Oncology, 2016; 7, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuidgeest, M. G. P.; Goetz, I.; Meinecke, A. K.; Boateng, D.; Irving, E. A.; van Thiel, G. J. M.; Welsing, P. M. J.; Oude-Rengerink, K.; Grobbee, D. E. The GetReal Trial Tool: Design, Assess and Discuss Clinical Drug Trials in Light of Real World Evidence Generation. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2022, 149, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boateng, D.; Kumke, T.; Vernooij, R.; Goetz, I.; Meinecke, A. K.; Steenhuis, C.; Grobbee, D.; Zuidgeest, M. G. P. Validation of the GetReal Trial Tool – Facilitating Discussion and Understanding More Pragmatic Design Choices and Their Implications. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 2023; 125, (December 2022). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R. Choosing the Unit of Randomization — Individual or Cluster? NEJM Evidence, 2024; 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemming, K.; Haines, T. P.; Chilton, P. J.; Girling, A. J.; Lilford, R. J. The Stepped Wedge Cluster Randomised Trial: Rationale, Design, Analysis, and Reporting. BMJ 2015, 350 (feb06 1), h391–h391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, R.; Walter, S. D.; Guyatt, G.; Devereaux, P. J.; Walsh, M.; Thorlund, K.; Thabane, L. Assessment and Implication of Prognostic Imbalance in Randomized Controlled Trials with a Binary Outcome – A Simulation Study. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e36677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heckman, J. J. Randomization as an Instrumental Variable. The Review of Economics and Statistics 1996, 78, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussman, J. B.; Hayward, R. A. An IV for the RCT: Using Instrumental Variables to Adjust for Treatment Contamination in Randomised Controlled Trials. BMJ 2010, 340 (may04 2), c2073–c2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wang, R. Stepped Wedge Cluster Randomized Trials: A Methodological Overview. World Neurosurg 2022, 161, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsing, P. M.; Oude Rengerink, K.; Collier, S.; Eckert, L.; van Smeden, M.; Ciaglia, A.; Nachbaur, G.; Trelle, S.; Taylor, A. J.; Egger, M.; Goetz, I. ; Work Package 3 of the GetReal Consortium. Series: Pragmatic Trials and Real World Evidence: Paper 6. Outcome Measures in the Real World. J Clin Epidemiol, 2017; 90, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuidgeest, M. G. P.; Welsing, P. M. J.; van Thiel, G. J. M. W.; Ciaglia, A.; Alfonso-Cristancho, R.; Eckert, L.; Eijkemans, M. J. C.; Egger, M. ; WP3 of the GetReal consortium. Series: Pragmatic Trials and Real World Evidence: Paper 5. Usual Care and Real Life Comparators. J Clin Epidemiol, 2017; 90, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussey, M. A.; Hughes, J. P. Design and Analysis of Stepped Wedge Cluster Randomized Trials. Contemp Clin Trials 2007, 28, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinecke, A.-K.; Welsing, P.; Kafatos, G.; Burke, D.; Trelle, S.; Kubin, M.; Nachbaur, G.; Egger, M.; Zuidgeest, M. ; work package 3 of the GetReal consortium. Series: Pragmatic Trials and Real World Evidence: Paper 8. Data Collection and Management. J Clin Epidemiol, 2017; 91, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldridge, S. M.; Ashby, D.; Kerry, S. Sample Size for Cluster Randomized Trials: Effect of Coefficient of Variation of Cluster Size and Analysis Method. Int J Epidemiol 2006, 35, 1292–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, C. A.; Lilford, R. J. The Stepped Wedge Trial Design: A Systematic Review. BMC Med Res Methodol 2006, 6, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurka, M. J.; Edwards, L. J. 8 Mixed Models. In Handbook of Statistics; Rao, C. R., Miller, J. P., Rao, D. C., Eds.; Epidemiology and Medical Statistics; Elsevier, 2007; Vol. 27, pp 253–280. [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, A. E.; Ahern, J.; Fleischer, N. L.; Van der Laan, M.; Lippman, S. A.; Jewell, N.; Bruckner, T.; Satariano, W. A. To GEE or Not to GEE: Comparing Population Average and Mixed Models for Estimating the Associations between Neighborhood Risk Factors and Health. Epidemiology 2010, 21, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X. Methods and Applications of Longitudinal Data Analysis; Elsevier, 2015.

- Bates, D.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using Lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 2015, 67, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, L. M.; Furberg, C. D.; DeMets, D. L.; Reboussin, D. M.; Granger, C. B. Fundamentals of Clinical Trials; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Liddy, C.; Hogg, W.; Taljaard, M. Intracluster Correlation Coefficients for Sample Size Calculations Related to Cardiovascular Disease Prevention and Management in Primary Care Practices. BMC Res Notes 2015, 8, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donner, A.; Birkett, N.; Buck, C. Randomization by Cluster. Sample Size Requirements and Analysis. Am J Epidemiol 1981, 114, 906–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemming, K.; Kasza, J.; Hooper, R.; Forbes, A.; Taljaard, M. A Tutorial on Sample Size Calculation for Multiple-Period Cluster Randomized Parallel, Cross-over and Stepped-Wedge Trials Using the Shiny CRT Calculator. Int J Epidemiol 2020, 49, 979–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grayling, M. J.; Wason, J. M. A Web Application for the Design of Multi-Arm Clinical Trials. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oude Rengerink, K.; Kalkman, S.; Collier, S.; Ciaglia, A.; Worsley, S. D.; Lightbourne, A.; Eckert, L.; Groenwold, R. H. H.; Grobbee, D. E.; Irving, E. A. ; Work Package 3 of the GetReal consortium. Series: Pragmatic Trials and Real World Evidence: Paper 3. Patient Selection Challenges and Consequences. J Clin Epidemiol, 2017; 89, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marler, J. R. Secondary Analysis of Clinical Trials--a Cautionary Note. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2012, 54, 335–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothwell, P. M. Treating Individuals 2. Subgroup Analysis in Randomised Controlled Trials: Importance, Indications, and Interpretation. Lancet, 2005; 365, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irving, E.; van den Bor, R.; Welsing, P.; Walsh, V.; Alfonso-Cristancho, R.; Harvey, C.; Garman, N.; Grobbee, D. E. ; GetReal Work Package 3. Series: Pragmatic Trials and Real World Evidence: Paper 7. Safety, Quality and Monitoring. J Clin Epidemiol. [CrossRef]

- Lau, S. W. J.; Huang, Y.; Hsieh, J.; Wang, S.; Liu, Q.; Slattum, P. W.; Schwartz, J. B.; Huang, S.-M.; Temple, R. Participation of Older Adults in Clinical Trials for New Drug Applications and Biologics License Applications From 2010 Through 2019. JAMA Netw Open 2022, 5, e2236149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).