Submitted:

02 May 2024

Posted:

07 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

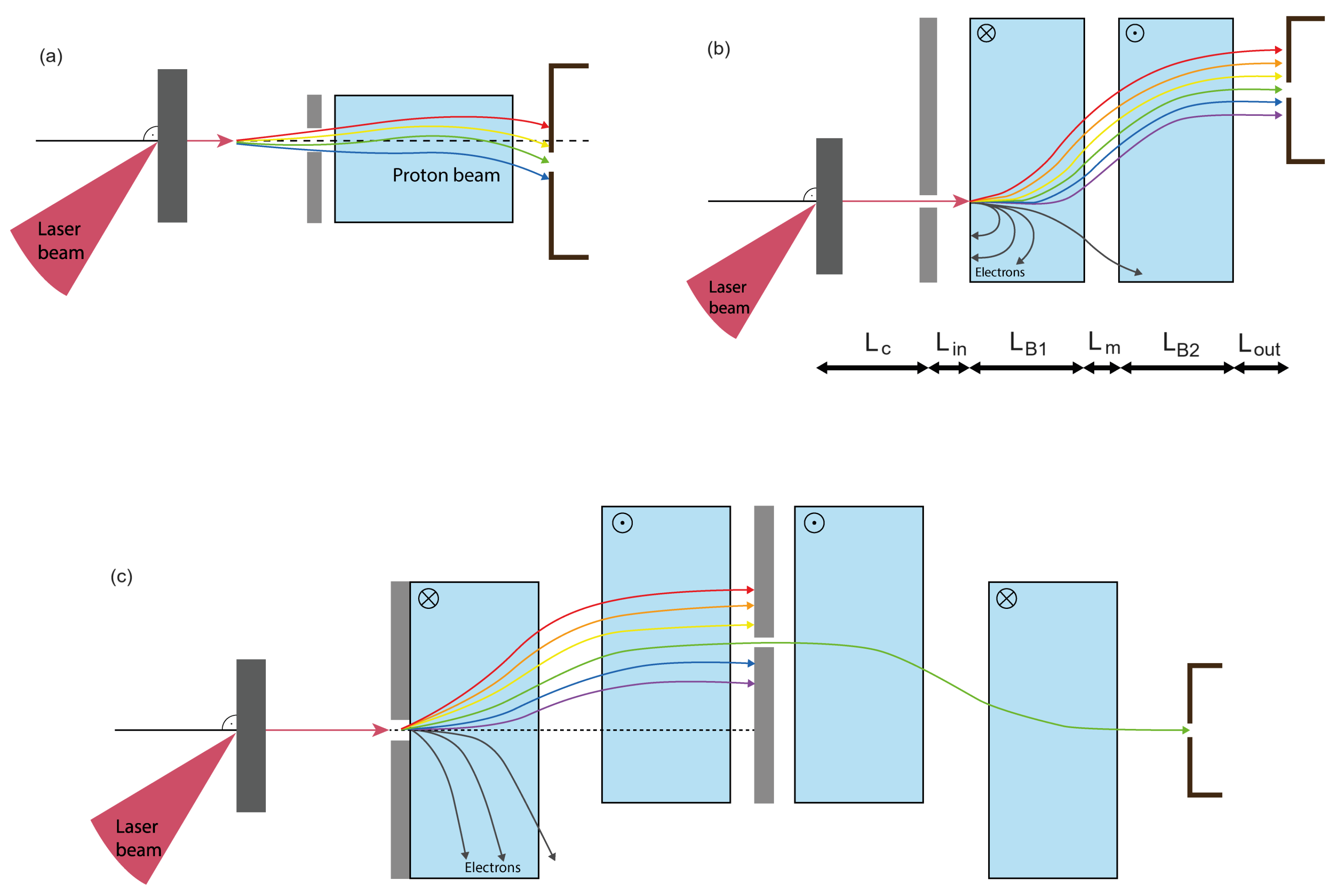

1. Introduction

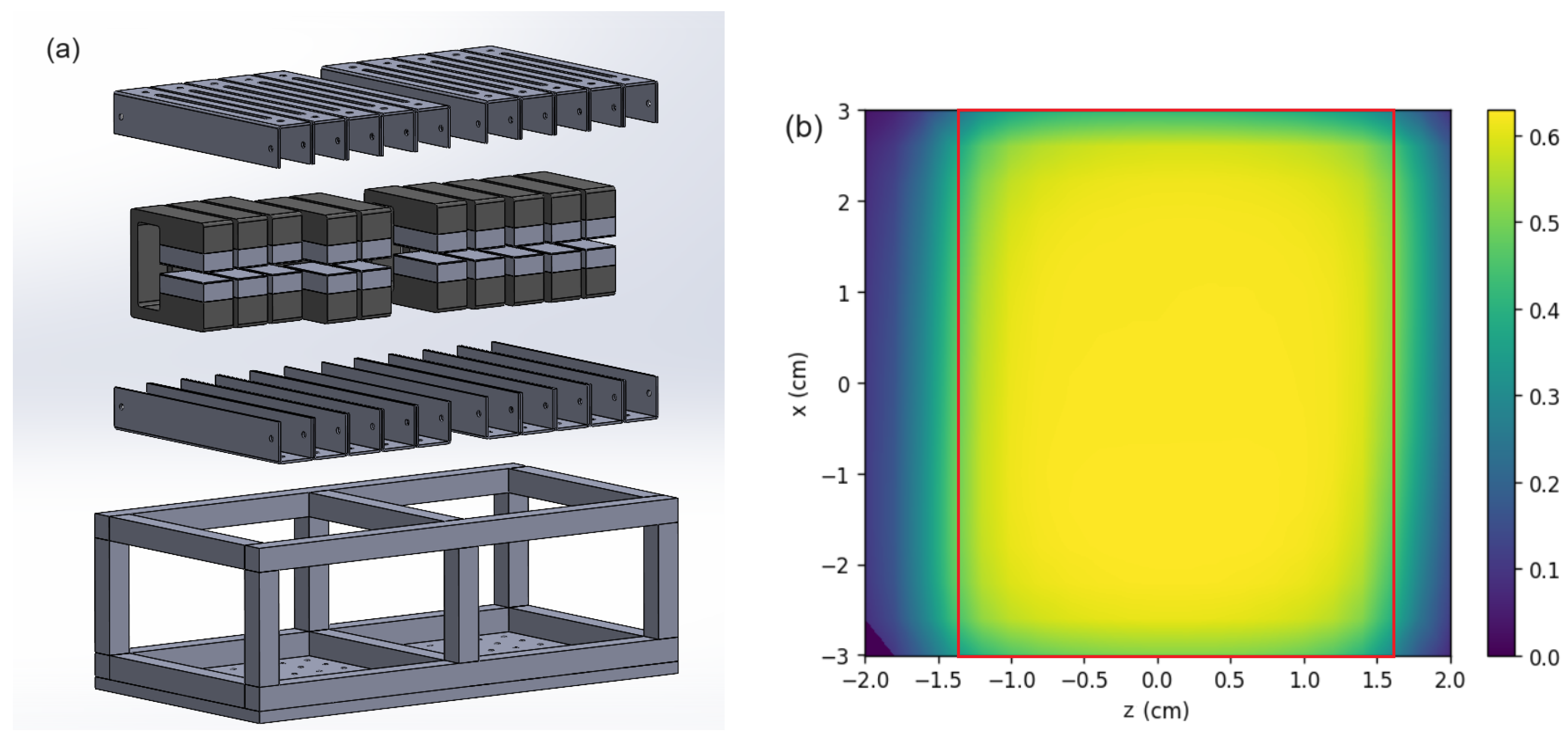

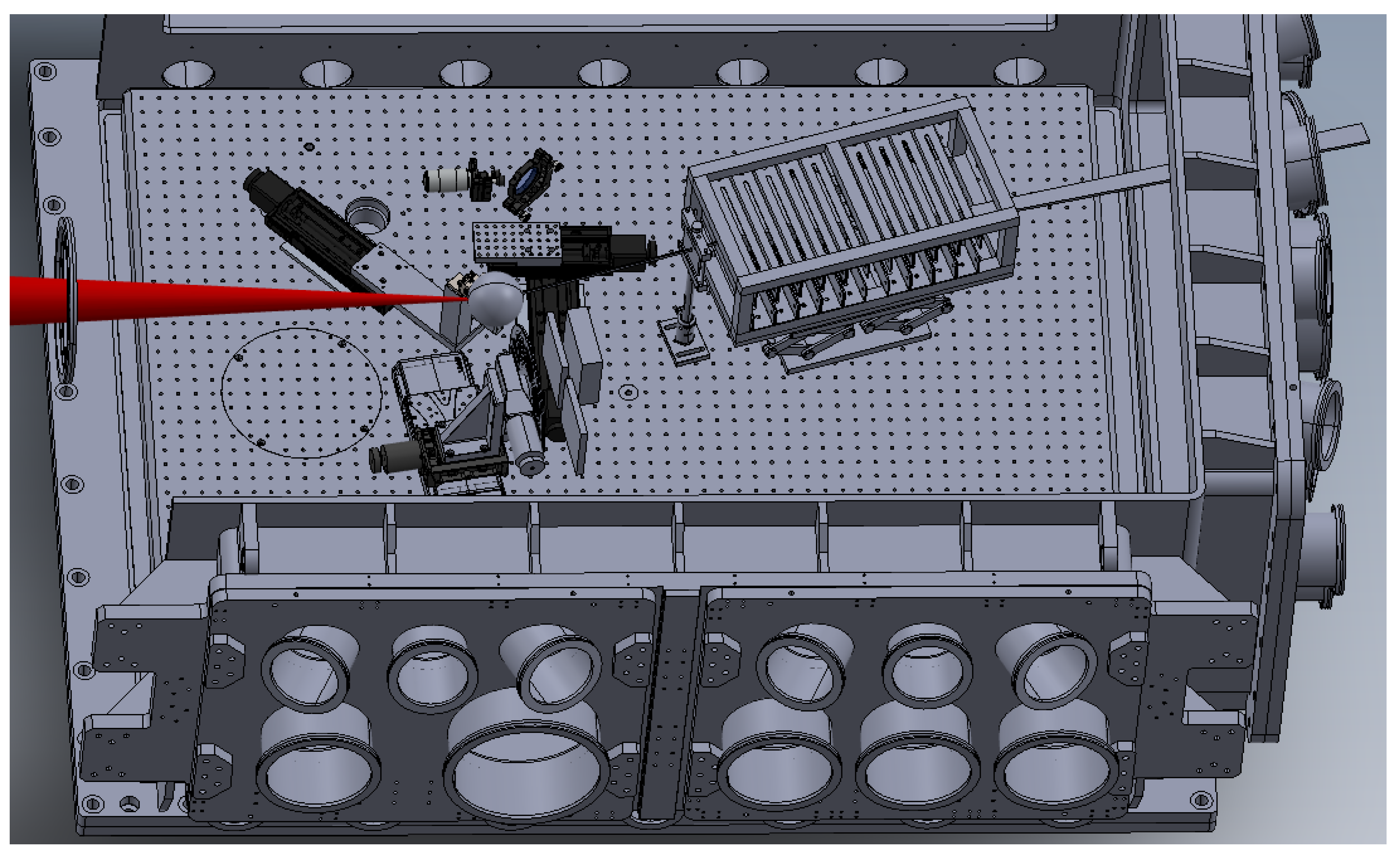

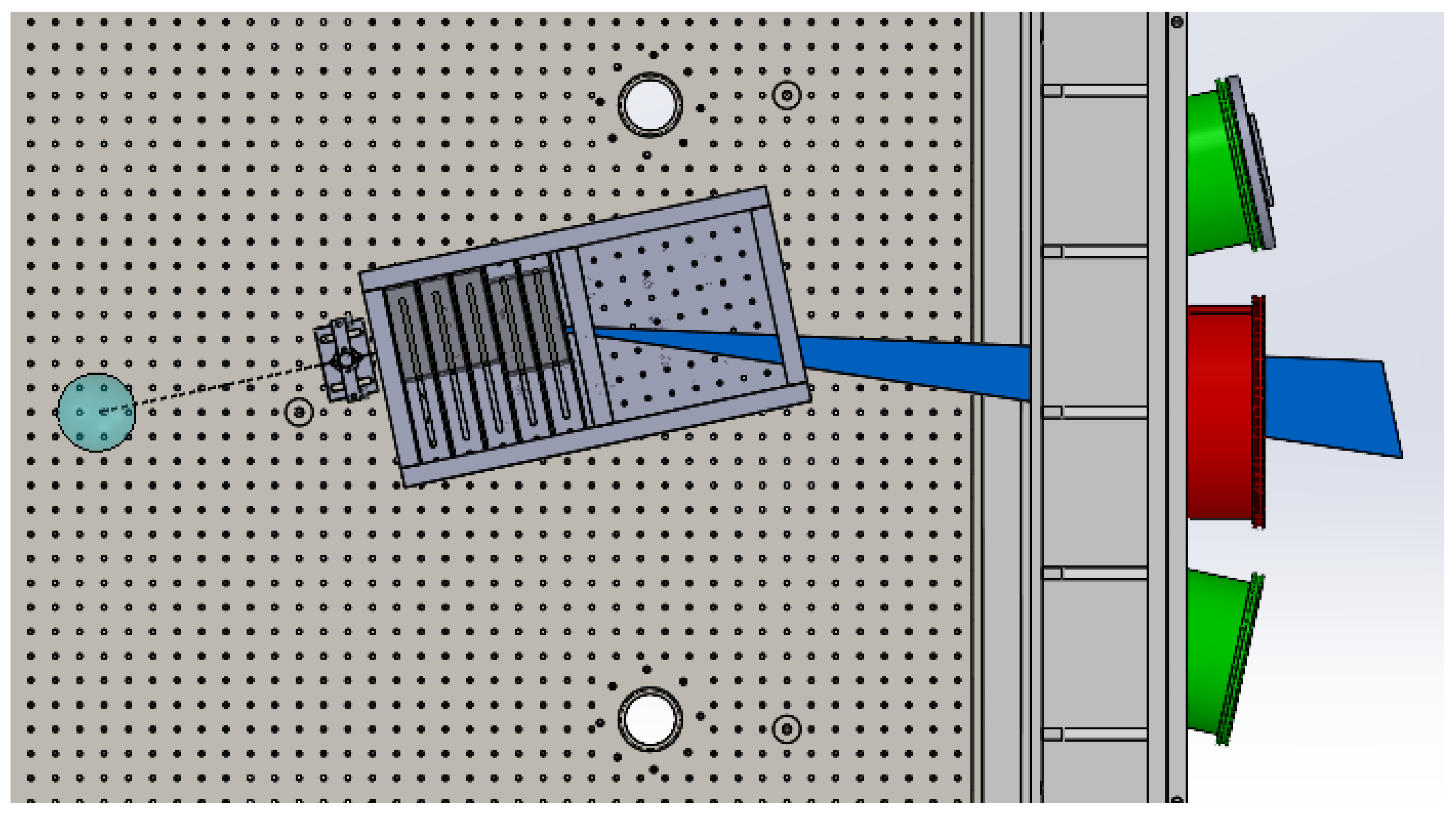

2. Materials and Methods

- The field orientations can be parallel or antiparallel.

- The minimum, longitudinal distance of adjacent magnet yokes is 5 mm.

- A maximum of ten C-magnets can be installed.

- The gaps can reach a maximum, lateral distance of mm from the central axis.

3. Results

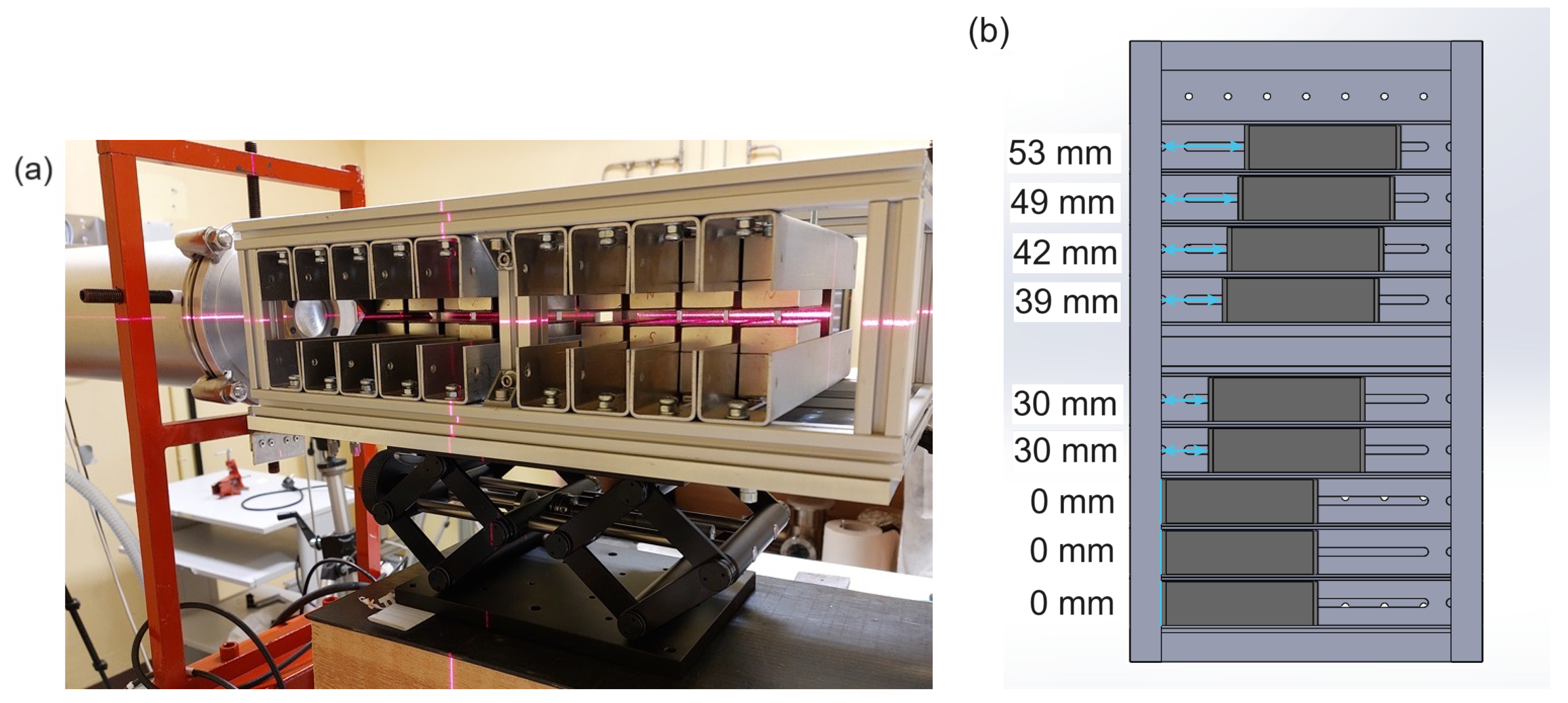

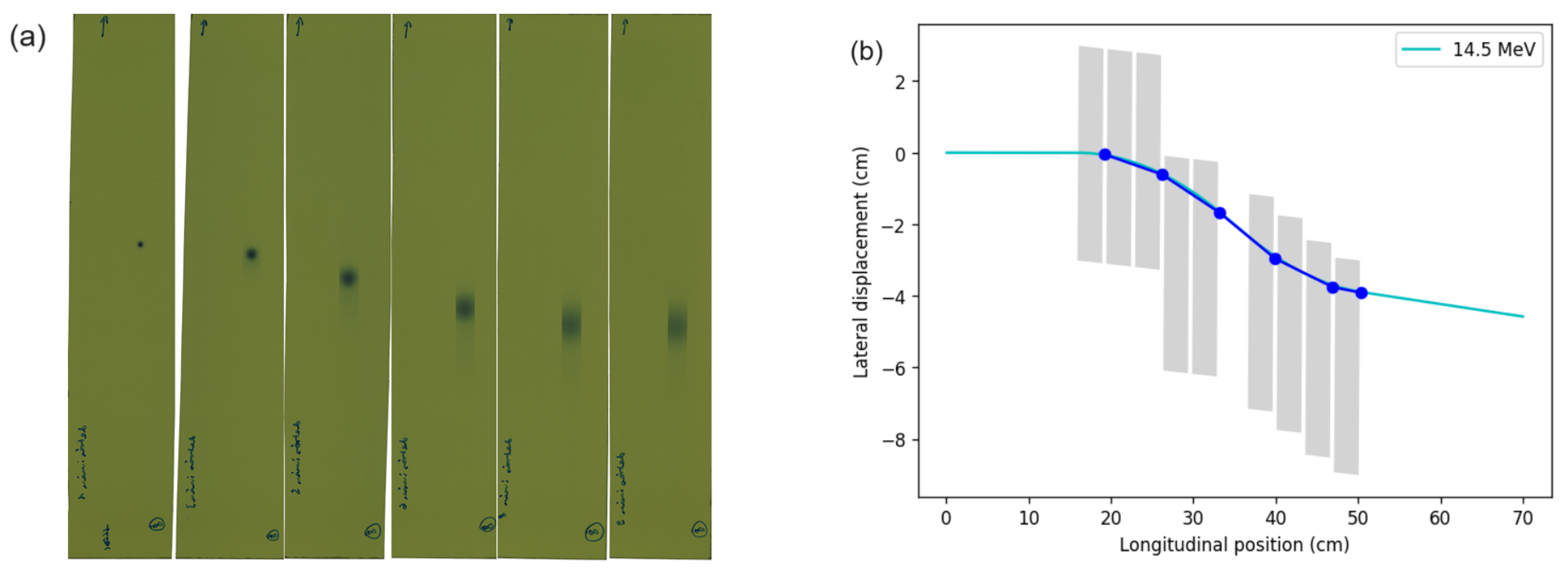

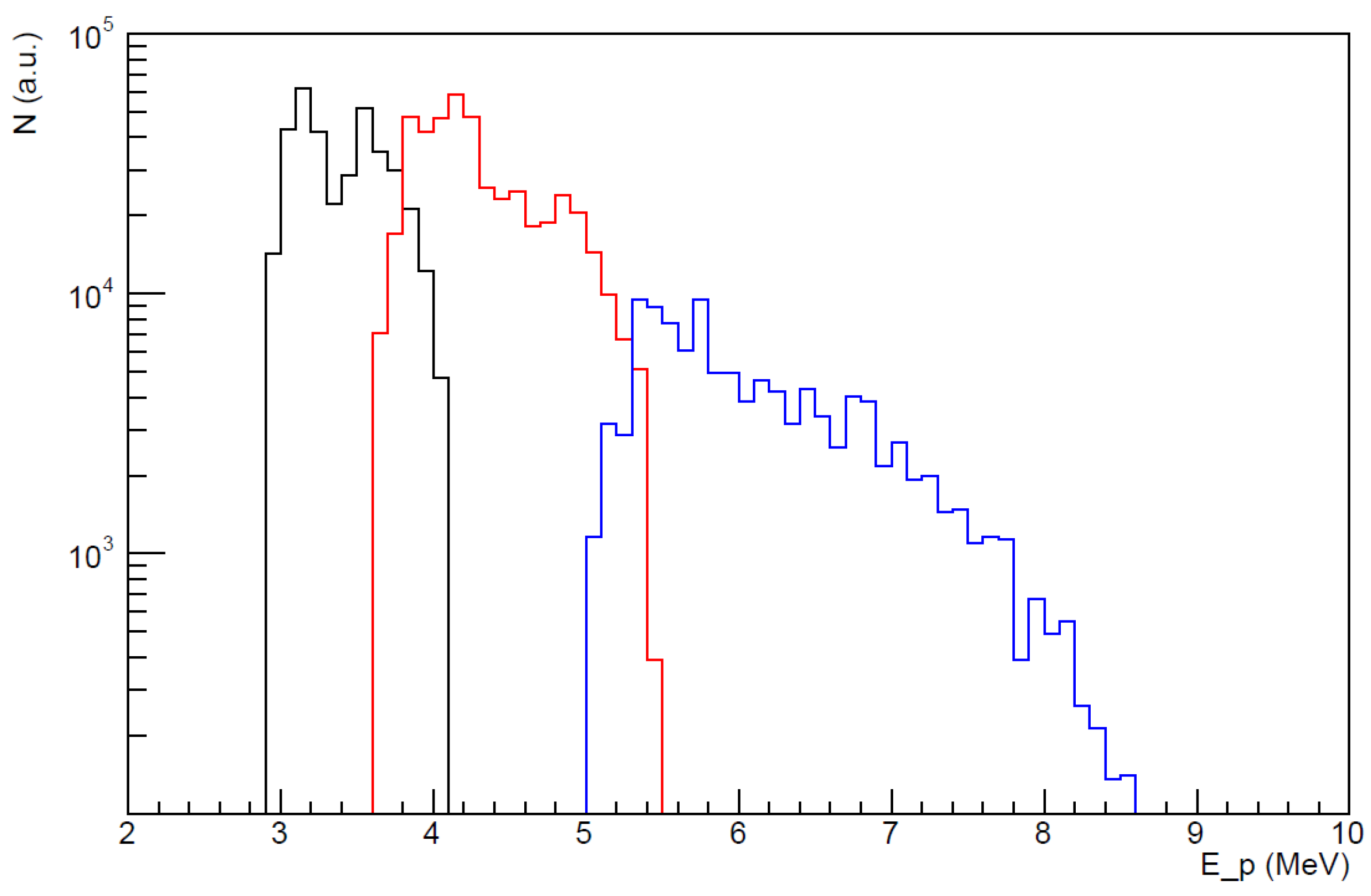

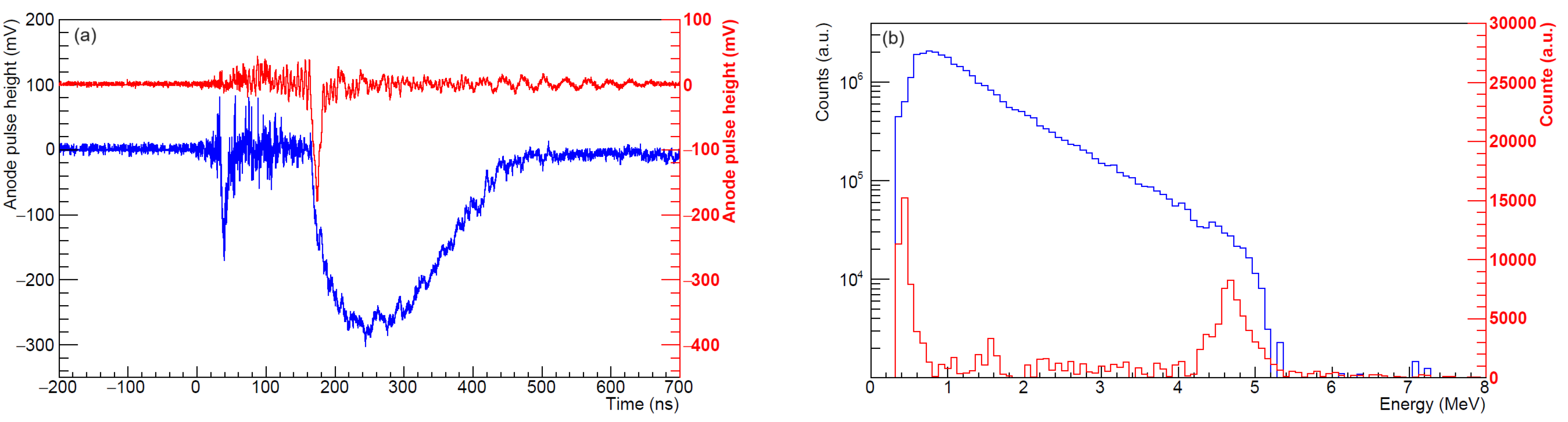

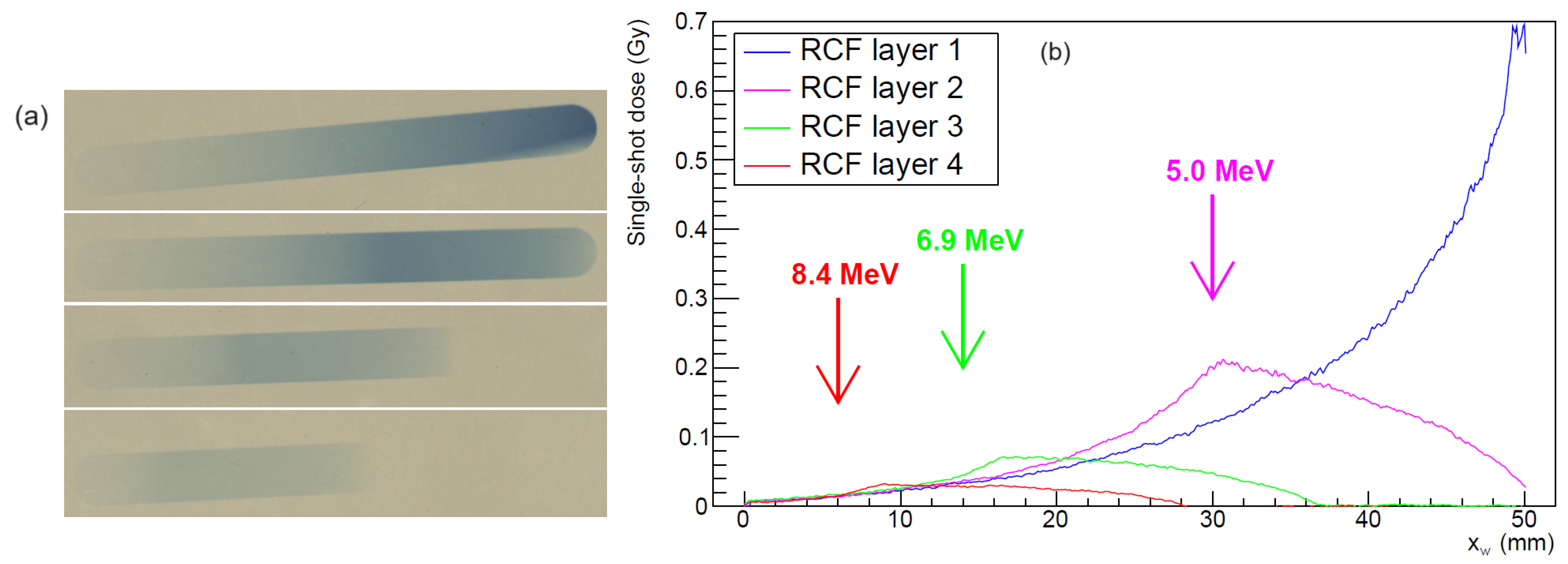

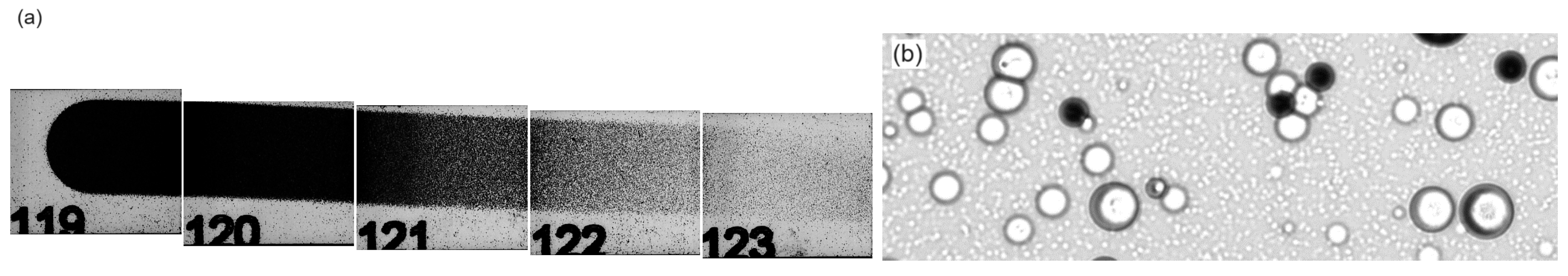

3.1. Test at CNA Cyclotron in Air

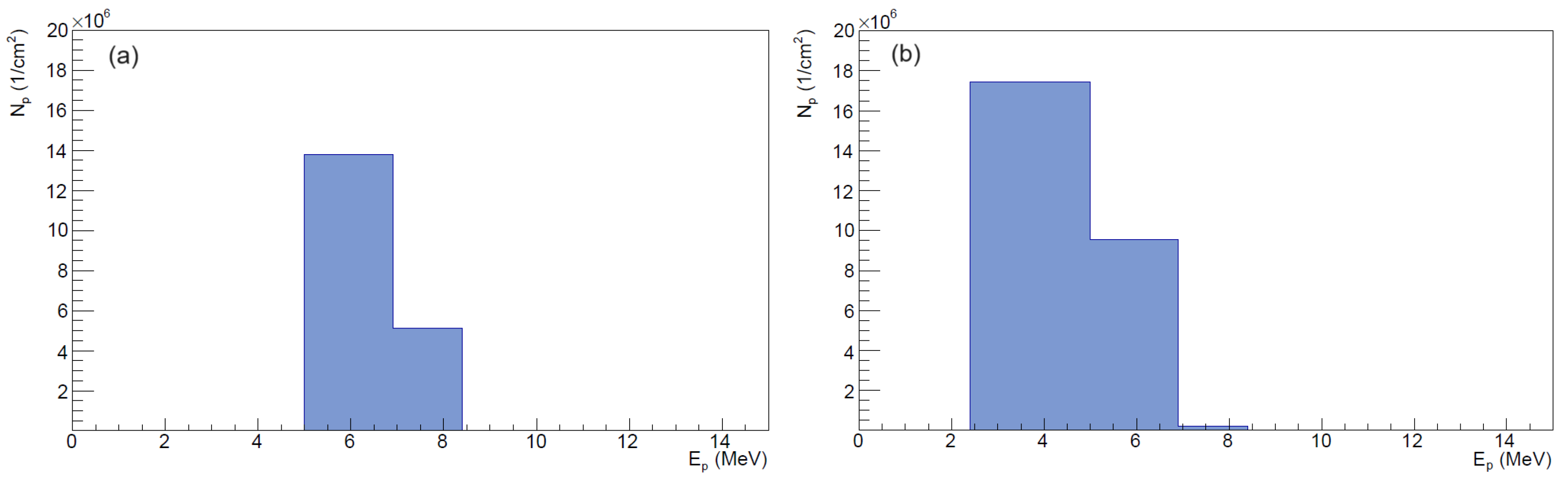

3.2. Specific Configuration for VEGA-3

3.3. Experiment at VEGA-3

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Daido, H.; Nishiuchi, M.; Pirozhkov, A.S. Review of laser-driven ion sources and their applications. Reports on Progress in Physics 2012, 75, 056401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macchi, A.; Borghesi, M.; Passoni, M. Ion acceleration by superintense laser-plasma interaction. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2013, 85, 751–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, M.; Schollmeier, M. Ion Acceleration-Target Normal Sheath Acceleration. CERN Yellow Reports 2016, 1, 231. [Google Scholar]

- Schwoerer, H.; Pfotenhauer, S.; Jäckel, O.; Amthor, K.U.; Liesfeld, B.; Ziegler, W.; Sauerbrey, R.; Ledingham, K.; Esirkepov, T. Laser-plasma acceleration of quasi-monoenergetic protons from microstructured targets. Nature 2006, 439, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henig, A.; Steinke, S.; Schnürer, M.; Sokollik, T.; Hörlein, R.; Kiefer, D.; Jung, D.; Schreiber, J.; Hegelich, B.M.; Yan, X.Q.; et al. Radiation-Pressure Acceleration of Ion Beams Driven by Circularly Polarized Laser Pulses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 103, 245003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haberberger, D.; Tochitsky, S.; Fiuza, F.; Gong, C.; Fonseca, R.A.; Silva, L.O.; Mori, W.B.; Joshi, C. Collisionless shocks in laser-produced plasma generate monoenergetic high-energy proton beams. Nature Physics 2012, 8, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaniyappan, S.; Huang, C.; Gautier, D.C.; Hamilton, C.E.; Santiago, M.A.; Kreuzer, C.; Sefkow, A.B.; Shah, R.C.; Fernández, J.C. Efficient quasi-monoenergetic ion beams from laser-driven relativistic plasmas. Nature Communications 2015, 6, 10170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, P.; Milluzzo, G.; Ahmed, H.; Odlozilik, B.; McMurray, A.; Prise, K.M.; Borghesi, M. Radiobiology Experiments With Ultra-high Dose Rate Laser-Driven Protons: Methodology and State-of-the-Art. Frontiers in Physics 2021, 9, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brack, F.E.; Kroll, F.; Gaus, L.; Bernert, C.; Beyreuther, E.; Cowan, T.E.; Karsch, L.; Kraft, S.; Kunz-Schughart, L.A.; Lessmann, E.; et al. Spectral and spatial shaping of laser-driven proton beams using a pulsed high-field magnet beamline. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 9118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rösch, T.F.; Szabó, Z.; Haffa, D.; Bin, J.; Brunner, S.; Englbrecht, F.S.; Friedl, A.A.; Gao, Y.; Hartmann, J.; Hilz, P.; et al. A feasibility study of zebrafish embryo irradiation with laser-accelerated protons. Review of Scientific Instruments 2020, 91, 063303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, F.; Brack, F.E.; Bernert, C.; Bock, S.; Bodenstein, E.; Brüchner, K.; Cowan, T.E.; Gaus, L.; Gebhardt, R.; Helbig, U.; et al. Tumour irradiation in mice with a laser-accelerated proton beam. Nature Physics 2022, 18, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aymar, G.; Becker, T.; Boogert, S.; Borghesi, M.; Bingham, R.; Brenner, C.; Burrows, P.N.; Ettlinger, O.C.; Dascalu, T.; Gibson, S.; et al. LhARA: The Laser-hybrid Accelerator for Radiobiological Applications. Frontiers in Physics 2020, 8, 567738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirrone, G.A.P.; Petringa, G.; Catalano, R.; Schillaci, F.; Allegra, L.; Amato, A.; Avolio, R.; Costa, M.; Cuttone, G.; Fajstavr, A.; et al. ELIMED-ELIMAIA: The First Open User Irradiation Beamline for Laser-Plasma-Accelerated Ion Beams. Frontiers in Physics 2020, 8, 564907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.K.; Frigola, P.; Travish, G.; Rosenzweig, J.B.; Anderson, S.G.; Brown, W.J.; Jacob, J.S.; Robbins, C.L.; Tremaine, A.M. Adjustable, short focal length permanent-magnet quadrupole based electron beam final focus system. Phys. Rev. ST Accel. Beams 2005, 8, 072401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schollmeier, M.; Becker, S.; Geißel, M.; Flippo, K.A.; Blažević, A.; Gaillard, S.A.; Gautier, D.C.; Grüner, F.; Harres, K.; Kimmel, M.; et al. Controlled Transport and Focusing of Laser-Accelerated Protons with Miniature Magnetic Devices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 101, 055004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishiuchi, M.; Daito, I.; Ikegami, M.; Daido, H.; Mori, M.; Orimo, S.; Ogura, K.; Sagisaka, A.; Yogo, A.; Pirozhkov, A.S.; et al. Focusing and spectral enhancement of a repetition-rated, laser-driven, divergent multi-MeV proton beam using permanent quadrupole magnets. Applied Physics Letters 2009, 94, 061107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin, J.; Allinger, K.; Assmann, W.; Dollinger, G.; Drexler, G.A.; Friedl, A.A.; Habs, D.; Hilz, P.; Hoerlein, R.; Humble, N.; et al. A laser-driven nanosecond proton source for radiobiological studies. Applied Physics Letters 2012, 101, 243701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pommarel, L.; Vauzour, B.; Mégnin-Chanet, F.; Bayart, E.; Delmas, O.; Goudjil, F.; Nauraye, C.; Letellier, V.; Pouzoulet, F.; Schillaci, F.; et al. Spectral and spatial shaping of a laser-produced ion beam for radiation-biology experiments. Phys. Rev. Accel. Beams 2017, 20, 032801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandi, F.; Labate, L.; Palla, D.; Kumar, S.; Fulgentini, L.; Koester, P.; Baffigi, F.; Chiari, M.; Panetta, D.; Gizzi, L.A. A Few MeV Laser-Plasma Accelerated Proton Beam in Air Collimated Using Compact Permanent Quadrupole Magnets. Applied Sciences 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, F.; Schillaci, F.; Cirrone, G.; Cuttone, G.; Scuderi, V.; Allegra, L.; Amato, A.; Amico, A.; Candiano, G.; De Luca, G.; et al. The ELIMED transport and dosimetry beamline for laser-driven ion beams. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2016, 829, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scisciò, M.; Migliorati, M.; Palumbo, L.; Antici, P. Design and optimization of a compact laser-driven proton beamline. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 6299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busold, S.; Schumacher, D.; Deppert, O.; Brabetz, C.; Frydrych, S.; Kroll, F.; Joost, M.; Al-Omari, H.; Blažević, A.; Zielbauer, B.; et al. Focusing and transport of high-intensity multi-MeV proton bunches from a compact laser-driven source. Phys. Rev. ST Accel. Beams 2013, 16, 101302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzkes, J.; Cowan, T.; Karsch, L.; Kraft, S.; Pawelke, J.; Richter, C.; Richter, T.; Zeil, K.; Schramm, U. Preparation of laser-accelerated proton beams for radiobiological applications. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 2011, 653, 172–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doria, D.; Kakolee, K.F.; Kar, S.; Litt, S.K.; Fiorini, F.; Ahmed, H.; Green, S.; Jeynes, J.C.G.; Kavanagh, J.; Kirby, D.; et al. Biological effectiveness on live cells of laser driven protons at dose rates exceeding 109 Gy/s. AIP Advances 2012, 2, 011209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanton, F.; Chaudhary, P.; Doria, D.; Gwynne, D.; Maiorino, C.; Scullion, C.; Ahmed, H.; Marshall, T.; Naughton, K.; Romagnani, L. and Kar, S.; et al. DNA DSB Repair Dynamics following Irradiation with Laser-Driven Protons at Ultra-High Dose Rates. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 4471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milluzzo, G.; Ahmed, H.; Romagnani, L.; Doria, D.; Chaudhary, P.; Maiorino, C.; McIlvenny, A.; McMurray, A.; Polin, K.; Katzir, Y.; et al. Dosimetry of laser-accelerated carbon ions for cell irradiation at ultra-high dose rate. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2020, 1596, 012038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manti, L.; Perozziello, F.; Borghesi, M.; Candiano, G.; Chaudhary, P.; Cirrone, G.; Doria, D.; Gwynne, D.; Leanza, R.; Prise, K.M.; et al. The radiobiology of laser-driven particle beams: focus on sub-lethal responses of normal human cells. Journal of Instrumentation 2017, 12, C03084–C03084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogo, A.; Sato, K.; Nishikino, M.; Mori, M.; Teshima, T.; Numasaki, H.; Murakami, M.; Demizu, Y.; Akagi, S.; Nagayama, S.; et al. Application of laser-accelerated protons to the demonstration of DNA double-strand breaks in human cancer cells. Applied Physics Letters 2009, 94, 181502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raschke, S.; Spickermann, S.; Toncian, T.; Swantusch, M.; Boeker, J.; Giesen, U.; Iliakis, G.; Willi, O.; Boege, F. Ultra-short laser-accelerated proton pulses have similar DNA-damaging effectiveness but produce less immediate nitroxidative stress than conventional proton beams. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 32441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogo, A.; Maeda, T.; Hori, T.; Sakaki, H.; Ogura, K.; Nishiuchi, M.; Sagisaka, A.; Kiriyama, H.; Okada, H.; Kanazawa, S.; et al. Measurement of relative biological effectiveness of protons in human cancer cells using a laser-driven quasimonoenergetic proton beamline. Applied Physics Letters 2011, 98, 053701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, J.; Biersack, J. SRIM - The stopping range of ions in solids. Pergamon 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Baratto-Roldán, A.; Jiménez-Ramos, M.d.C.; Jimeno, S.; Huertas, P.; García-López, J.; Gallardo, M.I.; Cortés-Giraldo, M.A.; Espino, J.M. Preparation of a radiobiology beam line at the 18 MeV proton cyclotron facility at CNA. Physica Medica: European Journal of Medical Physics 2020, 74, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peñas, J.; Bembibre, A.; Cortina-Gil, D.; Martín, L.; Reija, A.; Ruiz, C.; Seimetz, M.; Alejo, A.; Benlliure, J. A multi-shot target-wheel assembly for laser-driven proton acceleration. High Power Laser Science and Engineering (accepted) 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seimetz, M.; Bellido, P.; Soriano, A.; García López, J.; Jiménez-Ramos, M.C.; Fernández, B.; Conde, P.; Crespo, E.; González, A.J.; Hernández, L.; et al. Calibration and Performance Tests of Detectors for Laser-Accelerated Protons. IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science 2015, 62, 3216–3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seimetz, M.; Bellido, P.; Mur, P.; Lera, R.; de la Cruz, A.R.; Sánchez, I.; Zaffino, R.; Benlliure, J.; Ruiz, C.; Roso, L.; et al. Electromagnetic pulse generation in laser-proton acceleration from conductive and dielectric targets. Plasma Physics and Controlled Fusion 2020, 62, 115008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seimetz, M.; Peñas, J.; Llerena, J.; Benlliure, J.; García López, J.; Millán-Callado, M.; Benlloch, J. PADC nuclear track detector for ion spectroscopy in laser-plasma acceleration. Physica Medica: European Journal of Medical Physics 2020, 76, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).