1. Introduction

Driver safety holds significant importance due to its direct influence on the well-being of road users and overall public safety. Cognitive impairment is a crucial aspect when considering safe driving, as it can hinder an individual's capacity to process information, make prompt decisions, and react efficiently to ever-changing traffic scenarios. Recent studies have emphasized the vital significance of MWL and HRV in shaping the cognitive performance of drivers. MWL pertains to the cognitive challenges faced by drivers during different driving tasks, such as maneuvering through complex intersections or dealing with distractions on the road. Concurrently, HRV, which mirrors the adaptability of the autonomic nervous system, impacts the physiological responses to stressors and cognitive demands while driving. It is imperative to comprehend the intersection of MWL and HRV within the driving context to develop precise interventions, improve driver training schemes, and elevate road safety standards.

This study investigates the intricate correlation among cognitive impairment, MWL, HRV, and driver safety with the objective of proposing evidence-based approaches to enhance safe driving practices. By examining how these factors interplay, we aim to provide insights that can guide the implementation of strategies aimed at promoting safer driving behaviors. The paper presents a comprehensive review and in-depth analysis of cognitive dysfunction resulting from mental workload and variations in heart rate, delving into the intricate connection between cognitive impairment, mental workload, and physiological indicators like heart rate and eye movements. By investigating into this relationship, the study aims to gauge the mental workload experienced by drivers by utilizing data extracted from a heart rate monitoring system and an eye tracking system from prior studies, the outcomes of which could potentially revolutionize the development of innovative technologies geared towards mitigating cognitive dysfunction stemming from mental workload. The research methodology employed in the paper is distinguished by its methodical and rigorous approach, as it integrates the SPIDER and PRISMA frameworks for the purpose of collating and assessing pertinent literature.

The discoveries stemming from the study enrich the comprehension of cognitive impairments linked to mental workload and heart rate variability, furnishing valuable insights that can enhance driver safety and facilitate the development of efficacious interventions. This paper presents a review and analysis of cognitive impairment caused by MWL and HRV.

2. Literature Review

This literature review focused on cognitive impairment, mental workload, and physiological indicators like heart rate and eye movements in drivers. The reviewed studies can be categorized into three main areas:

2.1. Adaptive Interfaces And Driver Assistance Systems:

Several studies have explored the development and evaluation of adaptive interfaces and driver assistance systems to support drivers during cognitively demanding situations Chen et al. developed an adaptive multi-modal interface model was developed to assist drivers during a take-over request (TOR) from autonomous to manual driving, focusing on balancing convenience with safety risks [

1]. Roesener et al. proposed a comprehensive evaluation method for highly automated driving functions between SAE level 2-4, consisting of technical, user-related, in-traffic, and impact assessment components [

2]. Their methodology uniquely integrates various test tools and methods, including field tests, simulations, and user trials, to offer a holistic view of automated driving’s multifaceted implications. Once again, the cognitive and emotional impacts on drivers interacting with automated driving technologies have not been incorporated.

The effects of haptic assistive driving systems on driving behaviors studied by Tientcheu et al., highlighted the significance of a strong model-free controller for accommodating different driving styles. They ignore the high degree of uncertainties in human behavior [

10]. The impact of ambient lighting on driver performance and mental exertion during ten TORs have improved drivers' take-over performance. The sample collected with majority of young women may limiting the generalization [

3].

How behavioral measures impact the braking performance of older drivers under cognitive workloads, particularly focusing on the left foot position as a preventive strategy were studies by Murata et al., comparing simulated and real road environments to analyze braking errors and predict adaptive skills at intersections, achieving a 70% accuracy in forecasting adaptive skills by assessing the left foot posture of elderly drivers, enhancing the system's effectiveness and usefulness. [

4]. Perozzi et al. proposed the cooperative control strategy for lane-keeping enhanced cooperative driving quality by 9.4% and minimized conflict by 65.38% compared to the previous design without a sharing parameter, along with an 86.13% reduction in steering workload. [

5].

The research examined the acceptance of advanced safety features in Toyota Sienna and Prius models among 183 vehicle owners through telephone interviews, revealing a high level of interest in adaptive cruise control and forward collision avoidance, but slightly lower acceptance for lane departure warning and prevention, with variations observed based on drivers' age and gender, indicating potential differences in responses to emerging crash avoidance technologies in various vehicle models [

6].

Ma et al. study focuses on cognitive attributes impacting SA in driving scenarios, identifying eight cognitive states that influence drivers' SA. Their proposed guidelines show significant improvements in SA and decision-making through the new interface compared to existing systems [

7]. The research delves into the effects of training on drivers' capacity to engage with Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS) and Autonomous Vehicle (AV) technology, showcasing notable enhancements in precision, response time, and vehicle management post-training. [

8]. The research highlighted the significance of comparing video-based and text-based training methods for ADAS and AV functions, stressing the need for tailored training programs to ensure safe and competent operation of these technologies [9-10].

These studies generally highlight the motivation to enhance driver safety and performance through adaptive technologies, utilizing methods such as driving simulators, haptic assistive driving systems, and subjective workload measures. It will be interesting to see how these studies could be complemented by incorporating drivers’ mental workload.

2.2. Mental Workload Assessment Methods:

Researchers have investigated various methods to assess drivers' mental workload, including subjective measures, physiological indicators, and performance metrics.

Marquart et al. reviewed the increasing popularity of remote eye measurements as tools for evaluating driver workload without causing distraction, emphasizing the importance of using multiple assessment methods for increased validity and reliability [

11]. Chen et al. examined the effectiveness of eye-tracking metrics in evaluating a driver's cognitive load during semi-autonomous driving while performing non-driving tasks. They identified pupil diameter change, saccade characteristics, fixation duration, and 3D gaze entropy as consistent indicators of cognitive load in both visual and auditory multitasking situations. [

12]. Ji et al. studied the impact of NDRT on takeover performance in HAD contexts and the influence of workload on driver takeover performance. The study lacks details on sample size/participants, limiting generalizability. [

13]. They also study aims to analyze the relationship of driver reaction time, gaze-on time, road-fixation time, and take-over time. They solely examine the driver's reaction time, disregarding driving accuracy or safety [

14]. The study analyzed descriptive statistics and Friedman test results of pupil size under different HMI conditions at stop-sign intersections with and without traffic [

15].

In summary, these studies demonstrate the motivation to develop reliable and non-intrusive methods for assessing driver mental workload, employing techniques such as eye tracking, subjective questionnaires, and secondary task performance. However, limitations include the need for more diverse driving scenarios and the potential influence of individual differences on workload measures.

2.3. Relationship between Physiological Measures and Driver Cognitive States:

Several studies have explored the relationship between physiological measures, such as heart rate variability (HRV) and eye movements, and driver cognitive states, including mental workload, fatigue, and drowsiness.

Birrell et al. investigates the use of in-car physiological sensors to evaluate driver mental workload, with a specific focus on cardiovascular and respiratory measurements. They identified the changes in driving tasks that affect mental workload and the driver’s capacity to regain control of the vehicle. The investigation ignored the other relevant factors [

16]. The research paper proposes a methodology using mutual information from EEG and vehicular signals to create a feature set for assessing drivers' mental workload. This feature set shows promise for predicting and classifying tasks with low error and high accuracy, with SVM outperforming other classifiers. They left out the individual characteristics and experience [

17]. The research focuses on assessing drivers' cognitive workload using cognitive tests and physiological measures like heart rate variability and infrared thermal imaging. Machine learning models achieved high accuracies. A larger sample may influence the accuracy. [

18]. Biondi et al. investigated the use of heart rate detection for driver monitoring systems, highlighting the potential of HRV as an indicator of mental workload. The results indicate that average heart rate rises with increased demand in the secondary task, and younger drivers have a higher heart rate than older drivers [

19].

Lu et al. conducted a systematic review on detecting driver fatigue using HRV, identifying inconsistencies in HRV metrics between alert and fatigued drivers and emphasizing the need for further research on the relationship between HRV and fatigue causes [

20]. The article presents a novel adaptive interface between humans and machines that, enabling the automatic redirection of incoming phone calls to the voicemail without notifying the driver, when the estimated workload surpasses a predetermined threshold value. They used NASA TLX self-report scales for mental workload [

21]. The paper examines the use of wavelet analysis of heart rate variability signals to classify alert and drowsy driving events, comparing it to the traditional fast Fourier transform method. The wavelet-based method is more effective in terms of classification performance, achieving 95% accuracy using leave-one-out validation [

22]. The aim of the research was to develop a heart rate monitoring system using an Arduino Kit and a heart rate sensor to assess drivers' mental workload and enhance road safety through timely alerts [

23]. The study aimed to assess the impact of mental workload changes on army drivers' brain activity in combat and non-combat situations using EEG. Higher theta EEG power spectrum in the frontal, temporal, and occipital areas during complex scenarios indicated increased mental workload. Data were analyzed to evaluate the effects of workload on brain activity and driving performance. [

24].

The study utilized a cohort design, the Taiwan Bus Driver Cohort Study (TBDCS), to investigate the effectiveness of HRV analysis in predicting the risk of cardiovascular disease among occupational drivers over an eight-year timeframe [

25]. A physiological recognition strategy is developed using HRV parameters for feature construction and selection. It employs the BIN search strategy, KBCS selection criterion, PCA, LDA for feature extraction, and k-NN algorithm for recognition [

26]. The study investigated the ability to detect drowsiness by analyzing HRV in drivers using a driving simulator, incorporating time-domain, frequency-domain, and fractal methods, as well as theta brain wave activity [

27]. The research examines how scenario-based explanations impact user trust and satisfaction in Automated Valet Parking systems, emphasizing the importance of tailored solutions for different user groups to enhance trust, user experience, and reduce cognitive load [

28]. The research investigates the efficacy of HRV in identifying driver sleepiness while driving through machine learning techniques, achieving 85% accuracy with the random forest classifier, but facing challenges due to confounding variables [

29]. The paper examines heart rate variability and subjective workload in simulated driving environments, particularly in work zones on highways. The findings reveal that participants had increased workload in work zone scenarios and with higher traffic density, but heart rate measures were mostly unaffected [

30].

These studies are motivated by the desire to develop reliable and non-invasive methods for monitoring driver cognitive states, utilizing physiological sensors and machine learning techniques. However, limitations include the need for larger sample sizes, real-world validation, and the consideration of individual differences in physiological responses.

3. Review Methodology

The review methodology employed in this paper combines the utilization of two distinct frameworks, namely the SPIDER framework and the PRISMA qualitative review methodology framework. The SPIDER framework, which stands for Sample population, Phenomenon of Interest, Design of Study, Evaluation, and Research Type, provides a structured approach to organizing and analyzing research studies. On the other hand, the PRISMA framework, which stands for Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses, offers guidelines for conducting systematic reviews and meta-analyses. By integrating these two frameworks, the review methodology adopted by the paper ensures a comprehensive and rigorous evaluation of the research articles under investigation.

To ensure a representative and diverse Sample population for the review, a total of 120 articles were sourced from various digital libraries. These digital libraries included reputable sources such as the Web of Science (WOS) core collection, ACM, IEEE Xplore, Elsevier, MDPI, Springer, Taylor Francis, and the Arxiv Digital Library. This wide-ranging selection of digital libraries helps to encompass a broad spectrum of research articles related to the topic at hand, thus enhancing the overall validity and generalizability of the review findings. To establish the Phenomenon of Interest a systematic and thorough approach to article inclusion, the study followed a well-defined process. This process involved several stages, including preliminary screening, exclusion of duplicate articles, and evaluation of article eligibility based on specific inclusion criteria.

The Design of study and inclusion criteria were carefully designed to ensure that only relevant and high-quality articles were incorporated into the review. These criteria encompassed factors such as publication in recognized journals or conference proceedings, publication year between 2014 and 2023, relevance to the review objectives, and adherence to established standards. By adhering to these stringent criteria, the review methodology ensures that the selected articles are of high quality and directly contribute to the research objectives.

A comprehensive search strategy was devised. To evaluate and identify the relevant articles for review. The strategy involved the use of connecting keywords that were closely aligned with the scope of the review. These keywords included terms such as "mental workload, heart rate variability, take over request, society of automotive engineers, driver cognitive impairment and human machine interface. By utilizing these targeted keywords, the review methodology aimed to capture a wide range of articles that are specifically related to driver safety and cognitive impairment. This comprehensive approach ensures that the review encompasses a holistic and in-depth analysis of the topic, thereby enhancing the overall validity and reliability of the review findings.

To ensure that the review is not solely reliant on academic literature, the review methodology also incorporated different Research types like gray literature, formal reports, and reputable news repositories. This inclusion of diverse sources of information helps to provide an up-to-date analysis of the trends and developments in MWL, driver safety and cognitive impairment. To identify these additional sources of information, the snowballing method was employed. The snowballing method involves systematically searching through reference lists, citations, and recommendations from existing articles to identify other relevant sources. By utilizing this method, the review methodology ensures that the analysis is comprehensive and reflective of the latest advancements in the field of MWL, driver safety and cognitive impairment.

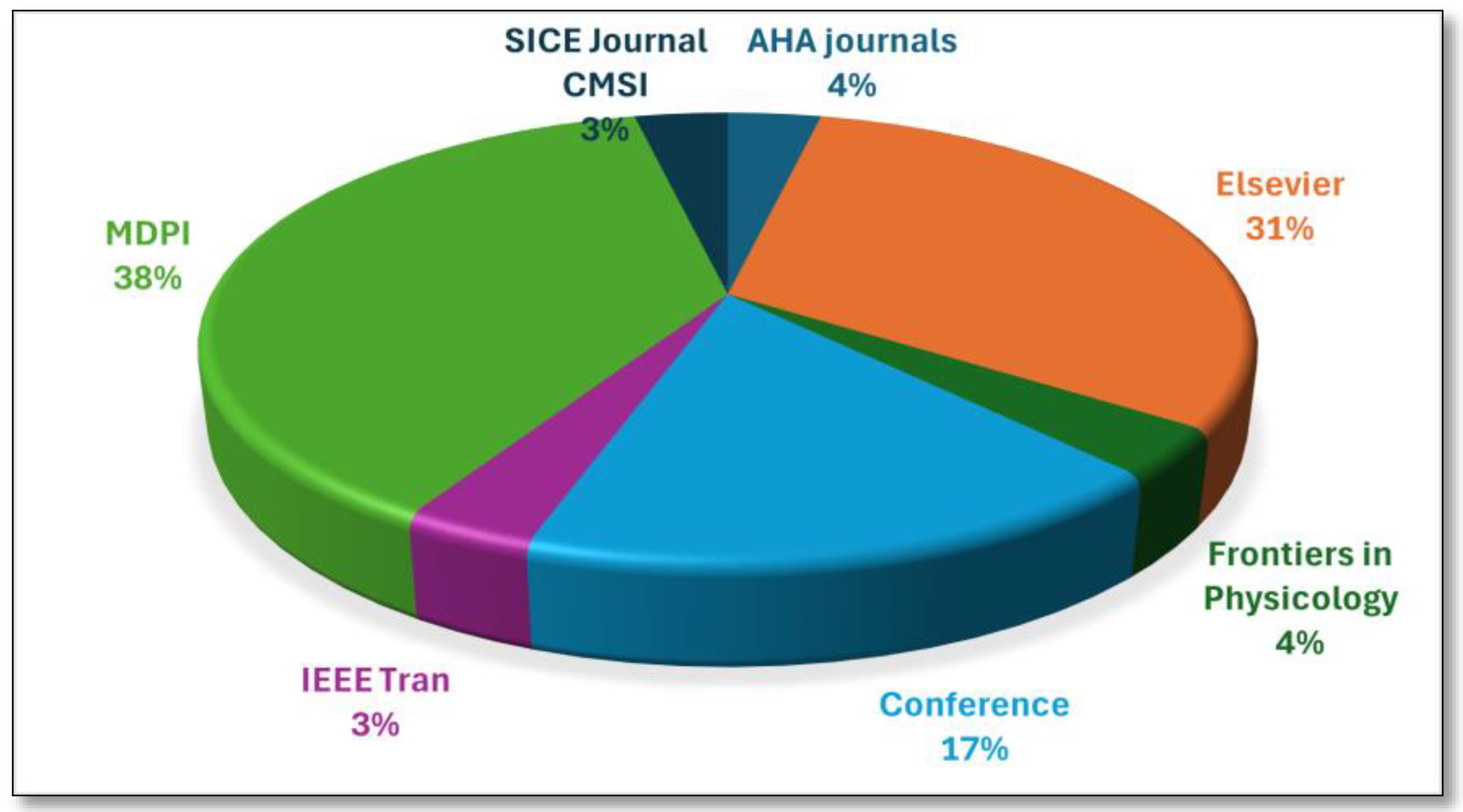

Figure 1 provides insights into the distribution of research papers across different platforms. MDPI stands out as the most prolific publisher, while Elsevier and conference proceedings also play significant roles. These findings contribute to our understanding of scholarly dissemination and academic impact. One article originating from each of the journals Frontiers in Physiology, American Heart Association (AHA), and IEEE Transactions has been included in the study, with each publication contributing to 3% of the total sample. Furthermore, a substantial portion of the literature included in the analysis comes from Elsevier, with a total of nine papers making up 31% of the overall dataset. In addition to journal articles, five papers sourced from conference proceedings were also integrated into the research, accounting for 17% of the total content reviewed. Notably, the highest number of papers, totaling eleven, were obtained from MDPI, making it the most significant contributor to the study with a representation of 38% of the entire dataset. The distribution of literature sources across various publishers and platforms demonstrates a diverse range of scholarly contributions that have been synthesized in this study. This comprehensive approach to selecting sources ensures a robust and well-rounded analysis of the topic under investigation.

4. Result

Heart Rate Variability (HRV), which measures the variation in time between successive heartbeats, has gained significant attention and recognition in the evaluation of Mental Workload (MWL). To comprehend the crucial role of HRV in understanding cognitive stress, it is essential to delve into the concept of MWL itself. When we talk about MWL, we are referring to the cognitive demands that are placed on an individual during the execution of a specific task. This concept encompasses various aspects such as mental effort, attention, and stress. The quantification of MWL plays a pivotal role in optimizing the design of tasks, enhancing overall performance, and ensuring the well-being of individuals.

HRV Metrics for MWL Assessment: When it comes to the assessment of MWL using HRV, there are various metrics that can be employed. One such set of metrics is the Time Domain Metrics, which involves the analysis of beat-to-beat intervals (RR intervals) over a certain period. Among these metrics, the Standard Deviation of RR Intervals (SDNN) is particularly important as it reflects the overall HRV. Additionally, the Root Mean Square of Successive Differences (RMSSD) is another metric that captures short-term variations in HRV.

Moving on to the Frequency Domain Metrics, these metrics focus on analyzing the frequency components of HRV. Low-Frequency (LF) Power is a metric that is linked to sympathetic activity, while the High-Frequency (HF) Power reflects the influence of the parasympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system. Lastly, the LF/HF Ratio is a metric that provides insights into the autonomic balance.

In addition to the above-mentioned metrics, Non-linear Metrics are also used to assess the complexity and adaptability of HRV. These metrics include the Correlation Dimension (D2), which tends to decrease during MWL, indicating reduced adaptability. Furthermore, Sample Entropy (SampEn) is another non-linear metric that measures the irregularity of HRV.

4.1. Investigating Methos, Features and Results. Part-1:

Numerous studies have been conducted to explore the relationship between HRV and MWL. These studies have consistently observed decreased HRV during mental tasks, particularly in the context of non-linear metrics such as D2. Additionally, alterations in HRV have been found to correlate with feelings of frustration and changes in myocardial oxygen consumption.

Considering the real-world applications of HRV, it has proven to be a valuable tool in assessing pilot workload, monitoring stress levels in healthcare professionals, and optimizing cognitive performance. By leveraging the insights provided by HRV, individuals and organizations can develop strategies to effectively manage and maintain well-being in demanding environments. In this extensive investigation of driving performance, in

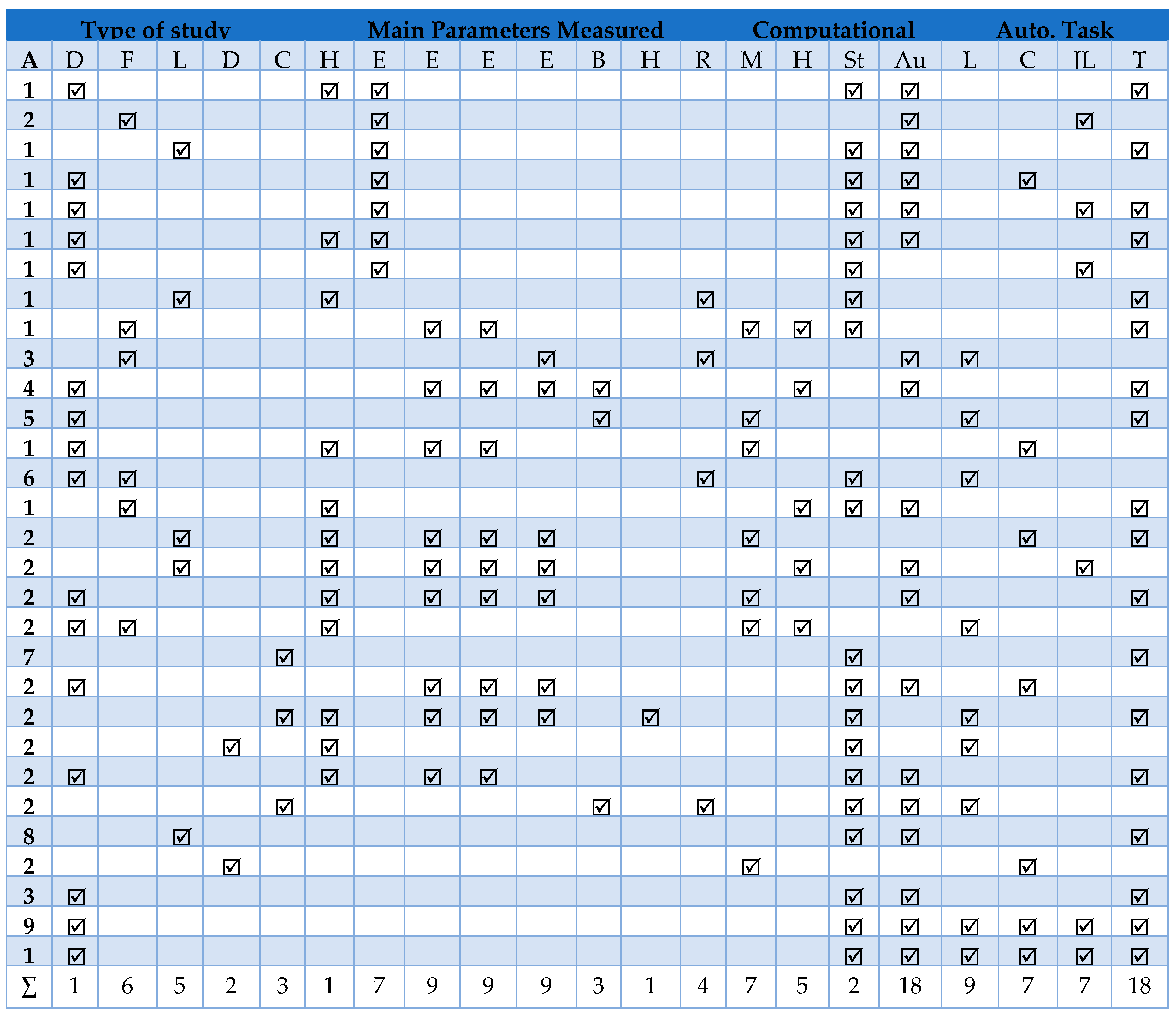

Table 1 a variety of methodologies have been utilized to uncover crucial insights regarding safety, workload management, and cognitive aspects. The EEG theta power activity as a reliable indicator of workload among military drivers, showing significant potential for implementation in practical training situations. The incorporation of wearable sensor technologies, like ear electrode arrays, has the potential to enhance the real-time monitoring of cognitive states, thus improving road safety. Additionally, metrics such as SDNN and LF levels have displayed independent predictive abilities concerning cardiovascular and hypertensive diseases, offering valuable information for evaluating long-term cardiovascular disease risk. The utilization of HRV-based recognition methods has demonstrated superior efficacy compared to other approaches, establishing it as a vital tool for identifying patterns in heart rate variability. Furthermore, biological signals such as RMSSD and SD1 have been recognized as sensitive parameters for detecting sleepiness, showing promise for the advancement of effective sleepiness detection systems. Particularly, explanations based on scenarios have proven to significantly boost situational trust, user experience, and mental workload management among drivers, resulting in quicker reaction times and reduced return times.

Moreover, higher situation awareness scores have been linked to more efficient decision-making processes, despite some lingering indecision in decision-making. Interestingly, driving experience has not shown significant impacts on situation awareness or decision-making questionnaire scores. Research has unveiled that ambient in-vehicle lighting can improve drivers' takeover performance, while EEG markers of mental workload have shown no significant differences between experimental and control groups. Furthermore, older drivers have demonstrated increased cognitive errors and mistakes in actions with age progression; however, their accident likelihood has decreased when faced with collision risks. The accurate prediction of coping abilities based on left foot posture near intersections has achieved a commendable accuracy level of 70%. Additionally, evaluations of fatigue and workload levels have heavily relied on heart rate variability and infrared measurements.

Adaptive phone settings have reduced mental workload for experienced drivers, with the SVM-based drowsiness detection system outperforming FFT-based methods, achieving an impressive accuracy of 95%. Lastly, heart rate readings during mental workload tasks have provided valuable insights into drivers' physiological reactions. Scholars have delved into methodologies related to heart rate variability and subjective workload in the driving realm, with the random forest classifier emerging as the preferred binary classification tool, despite a 20-percentage point decrease in performance for multi-class classification. Importantly, the development of personalized algorithms is crucial for the efficient monitoring of driver sleepiness based on HRV metrics. Additionally, weak correlations have been noted between heart rate variability measures and subjective workload, as well as between driving performance indicators and subjective workload.

4.2. Analysing Type, Parameters, Tool and Task. Part-2:

We have explored various methods and their impact on driving performance and workload. Notable findings include improved driving performance with specific interventions (e.g., DS, AOSPAN, PASAT), safety consequences during obstacle encounters (F&Tt, AdaptIVe), and the influence of lighting conditions (DS, F&Tt, EEG). Metrics such as heart rate, eye movement, and pupillary response were used to assess workload. Additionally, SVM demonstrated high accuracy in workload classification tasks. Overall, these studies contribute valuable insights for enhancing driving safety and efficiency.

In this comprehensive investigation encompassing diverse methodologies, in we have meticulously scrutinized critical parameters associated with driving performance. Notably, EEG theta power activity emerged as a robust workload indicator among army combat drivers, holding significant promise for real-world training scenarios. The integration of wearable sensor technologies, specifically around-the-ear electrode arrays, presents an avenue for real-time monitoring of cognitive states, thereby enhancing road safety. Furthermore, in

Table 2 the study delved into cardiovascular health, identifying independent predictors of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and hypertensive disease through parameters such as standard deviation of normal-to-normal intervals (SDNN) and low-frequency (LF) levels. These insights hold valuable implications for assessing long-term CVD risk.

The heart rate variability parameter-based recognition strategy outperformed alternative methods, positioning it as a valuable tool for identifying intricate patterns within heart rate variability. Additionally, biological signals, such as root mean square of successive RR interval differences (RMSSD) and standard deviation of Poincaré plot (SD1), exhibited sensitivity in detecting sleepiness, offering potential for the development of effective sleepiness detection systems

4.3. Studies and Applications. Part-3:

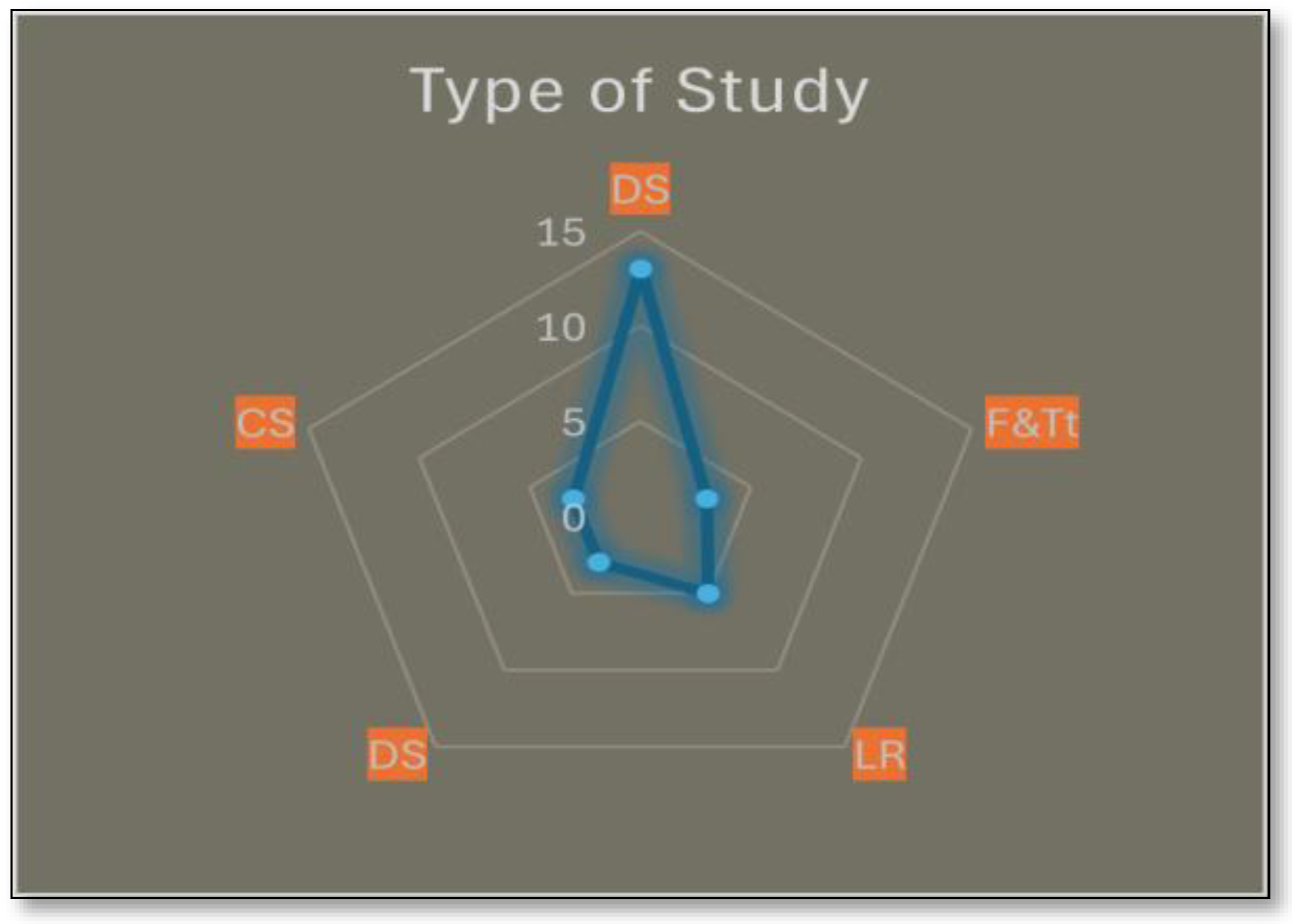

Driving simulator studies entail the observation and description of phenomena without manipulating variables, offering valuable insights into patterns and characteristics within a population. Thirteen studies in our analysis fall within this category, representing 46% of the total. Field and track test studies, on the other hand, investigate cause-and-effect relationships by manipulating variables in real-world settings, playing a crucial role in the assessment of interventions or treatments. Within our dataset, three studies (11%) are categorized as such. Literature reviews synthesize existing research to present a comprehensive overview of a topic, aiding in the identification of gaps, trends, and areas requiring further investigation. In our analysis, five studies (18%) contribute to this category. Case studies involve in-depth exploration of specific instances or individuals to comprehend unique phenomena, providing detailed insights that may not be broadly applicable. In the case of our analysis, three studies (11%) are classified as case studies.

Figure 2 provides an overview of the distribution of different study types within a review and analysis. Driving simulator (DS) constitute the largest proportion, followed by literature reviews (LR), field and track studies (F&Tt), and case studies (CS).

4.4. Investigation Physiological Parameters. Part-4:

Physiological Sensors and Mental Workload: Studies have utilized physiological sensors, including heart rate monitoring, in conjunction with other measures such as infrared (IR) thermal imaging and electroencephalography (EEG), to assess drivers' mental workload. Machine learning classifiers have been employed to analyse multimodal data, leading to promising outcomes in categorizing levels of mental workload. However, inconsistencies in results highlight the importance of refining methodologies and conducting thorough testing in real-life conditions.

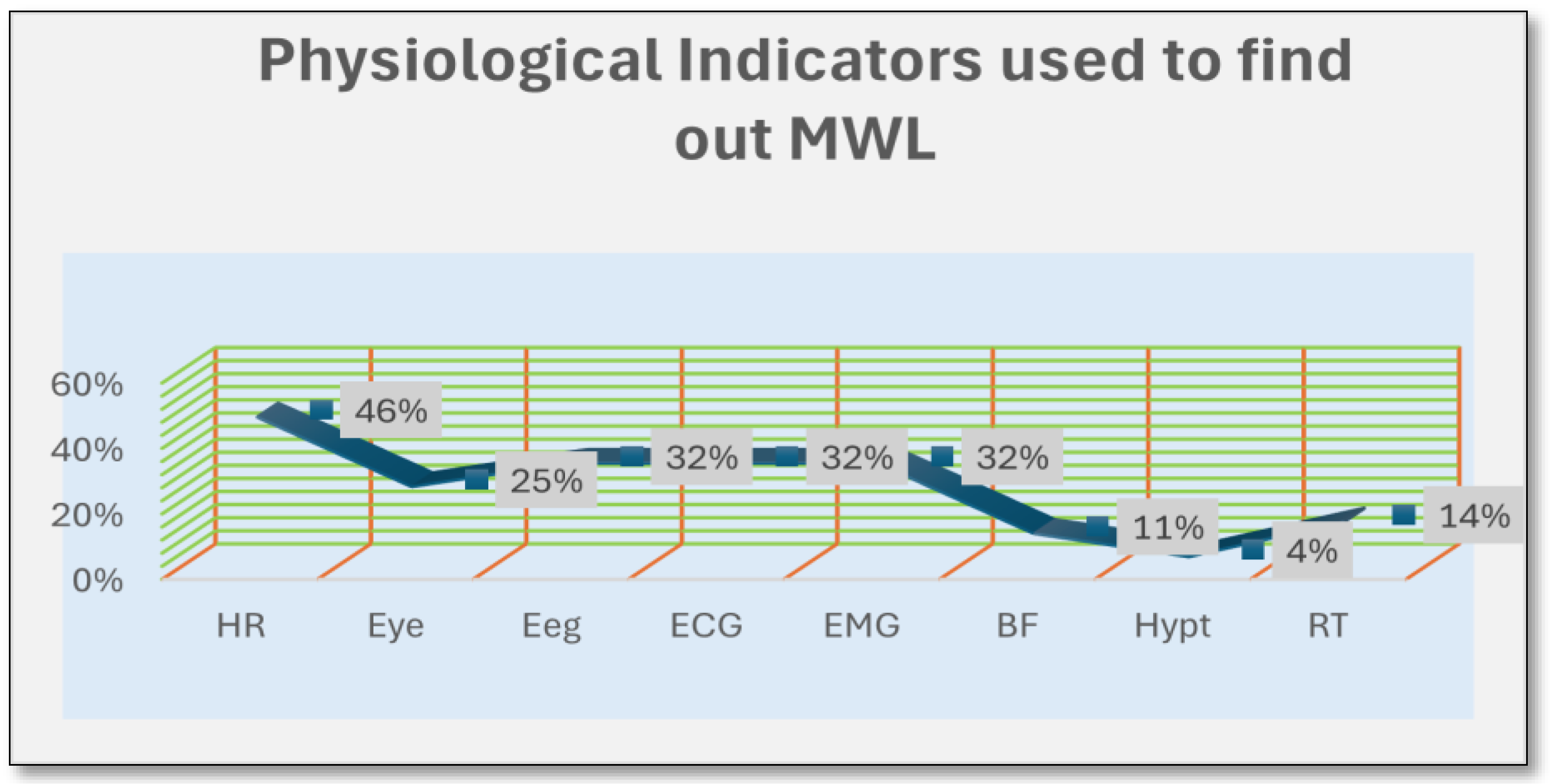

In this specific scenario, an investigation is carried out concerning the impacts of different physiological parameters. In

Figure 3 a comprehensive examination is performed regarding their individual contributions such as HR, Eye, ECG, and other parameters. Heart Rate (HR): With the most significant weightage of 46%, heart rate occupies a central position within the physiological framework. It potentially serves as an indicator of an individual's cardiovascular health or stress levels, thus representing a crucial aspect of their overall well-being. Eye: Holding a substantial 25% contribution, parameters related to the eye are important. These parameters may involve visual attention, eye movements, or cognitive processes, offering insights into various cognitive and visual functions. Electroencephalogram (EEG), Electrocardiogram (ECG), and Electromyogram (EMG): Each of these factors carries a 32% contribution, emphasizing their equal importance in the realm of physiology. EEG records the brain's electrical activity, ECG monitors heart function, while EMG assesses muscle activity levels, collectively providing essential insights into diverse bodily functions. Blood Flow (BF): Representing 11% of the overall impact, blood flow may seem less prominent compared to other parameters. Nevertheless, its interpretation within a particular context could yield valuable and detailed information concerning physiological responses. Hypertension (Hypt): Contributing minimally at only 4%, hypertension appears to exert a relatively minor influence on the ongoing physiological assessment. Reaction Time (RT): Playing a moderate role with a 14% contribution, reaction time introduces another layer to the thorough analysis of physiological parameters, underscoring the significance of prompt responses in various situations.

4.5. Computational Tools. Part-5:

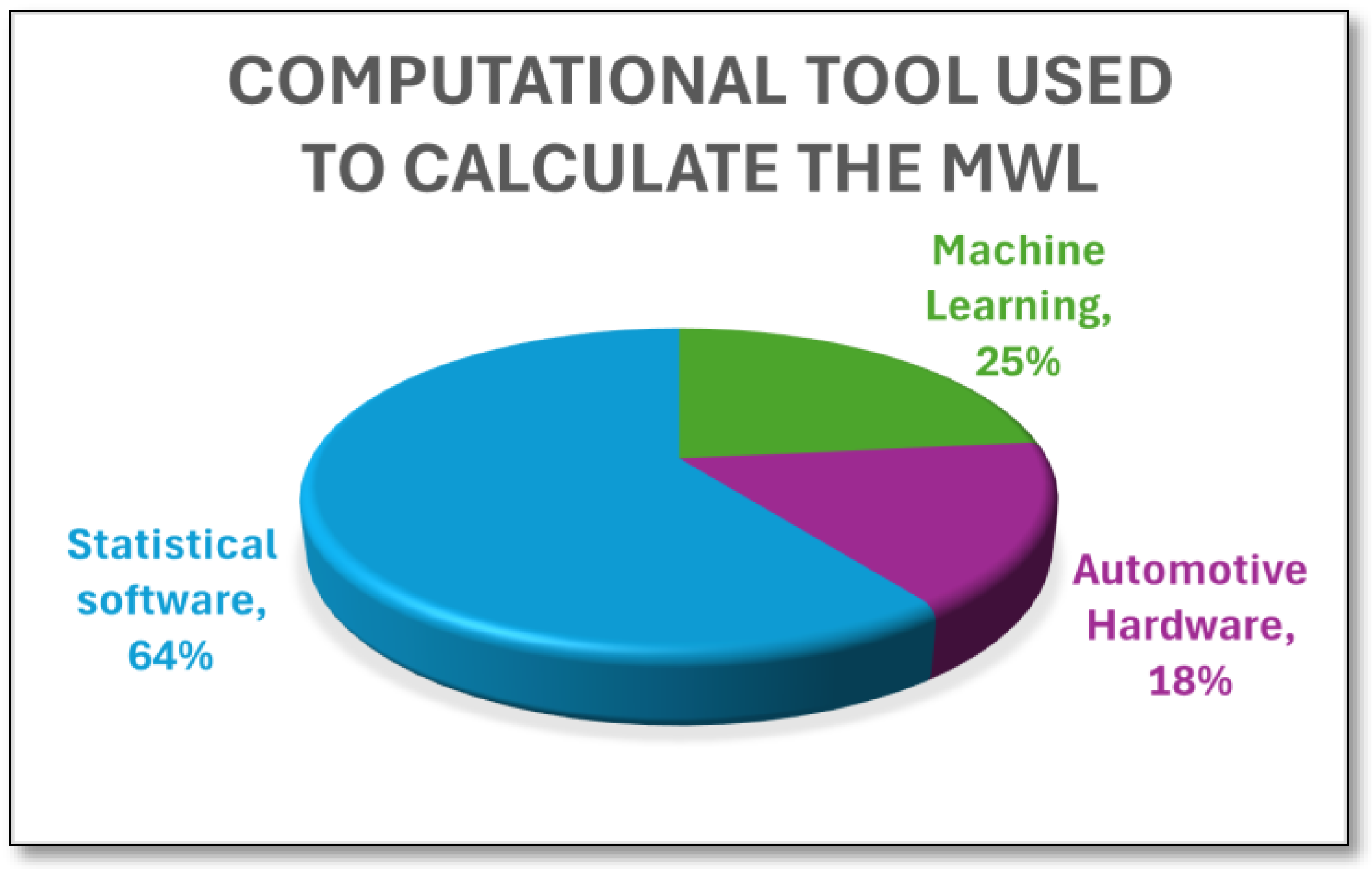

Statistical Software accounts for 64% of the computational tools utilized, making it the most dominant category. Professionals such as researchers and analysts heavily depend on statistical software for various data-related tasks including data analysis, hypothesis testing, and deriving meaningful insights from datasets. The widespread adoption of statistical packages can be attributed to their robustness and well-established methodologies that ensure reliable results. Statistical software stands out as a crucial tool in the realm of data analytics due to its versatility and effectiveness in handling complex statistical computations. Machine Learning techniques are another significant player in computational tasks, representing 25% of the tools used. These techniques find applications in diverse domains for tasks such as predictive modelling, classification, and pattern recognition. The adaptability and efficiency of machine learning algorithms make them highly valuable for solving complex problems across different industries and research areas. The utilization of machine learning tools continues to grow as more organizations recognize the potential benefits these techniques offer in improving decision-making processes and enhancing overall performance. Automotive Hardware tools, with an 18% usage rate, play a pivotal role in the automotive industry by supporting various functions. These tools encompass sensors, controllers, and embedded systems that are essential for vehicle control, safety mechanisms, and optimizing performance. The integration of automotive hardware components into vehicles ensures efficient operation and enhances the overall driving experience for users. The reliance on automotive hardware tools underscores their importance in modern vehicle design and manufacturing processes, highlighting their contribution to the advancement of automotive technology.

In

Figure 4, statistical software emerges as the frontrunner in computational tools, followed by machine learning and automotive hardware which also make substantial contributions to various computational tasks in different fields. The combination of these tools reflects the diverse technological landscape and the critical role they play in driving innovation and progress in today's data-driven world.

In summary the paper presented a thorough examination of the cognitive deficits resulting from mental workload and heart rate variability within the driving safety framework, emphasizing the relationship among cognitive impairment, workload, and physiological signals such as heart rate and eye movements. The research underscores the significance of understanding the interplay among cognitive abilities, workload requirements, and bodily reactions for ensuring driving safety. The results indicate the relevance of heart rate variability and infrared measurements in the assessment of fatigue and workload levels. Assessing fatigue and workload, heart rate variability (HRV) and infrared (IR) measurements emerged as critical tools, particularly with adaptable phone settings reducing mental workload for proficient drivers. A system for drowsiness detection based on Support Vector Machine (SVM) exhibited superior effectiveness when compared to methods based on Fast Fourier Transform (FFT), achieving a remarkable accuracy rate of 95%. Insights gained from heart rate (AHR) data collected during tasks involving mental workload proved to be invaluable, contributing to the enhancement of driving safety protocols and understanding human performance while driving. The investigation identified that an eco-safe driving Human-Machine-Interface (HMI) could notably encourage eco-friendly driving behaviors without excessively burdening drivers with mental and visual tasks. By summarizing existing literature on the analysis of driver mental workload (MWL) through in-vehicle physiological sensors, the paper focuses on cardiovascular and respiratory metrics. Notably, the research highlights the safety implications of durations ranging from 2 seconds to 17 seconds when a vehicle approaches an obstacle in the same lane.

5. Discussion

The findings from this review highlight the complex interplay between mental workload, cognitive impairment, and physiological indicators in the context of driving safety. The results suggest that HRV and IR measurements are crucial in assessing fatigue and workload levels, particularly among experienced drivers. This observation aligns with previous research that has identified HRV as a promising indicator of mental workload and cognitive stress [15-19]

Another key finding is the effectiveness of adaptive interfaces and driver assistance systems in promoting safe driving behaviors without excessively burdening drivers. This suggests that well-designed HMIs can help mitigate the cognitive demands placed on drivers, reducing the risk of cognitive impairment, and enhancing overall driving performance. However, it is important to note that the success of such systems may depend on factors such as driver experience, age, and individual differences in cognitive abilities [7-8]

The review also highlights the potential of ML techniques in analyzing multimodal data from physiological sensors to assess driver mental workload. The high accuracy achieved by SVM in classifying mental workload levels based on HRV and IR features suggests that these methods could be valuable for developing real-time monitoring systems. However, the inconsistencies in results across different studies demonstrated the need for further research to refine methodologies and validate the reliability of these approaches in real-world driving conditions.

One of the limitations of the current research is the lack of consideration for individual differences in cognitive and physiological responses to mental workload. Age, driving experience, and cognitive abilities may influence how drivers perceive and respond to cognitive demands. Future studies should investigate these individual differences to develop more personalized and adaptive interventions for enhancing driving safety.

Another limitation is the reliance on simulated driving environments in many reviewed studies. While driving simulators provide a controlled setting for assessing driver performance and cognitive states, they may not fully capture the complexities and unpredictability of real-world driving situations. Future research should aim to validate the findings from simulator studies in real-world driving conditions to ensure the generalizability and ecological validity of the results.

Despite these limitations, the findings from this review have important implications for the development of driver monitoring systems and the design of adaptive interfaces. By incorporating physiological measures such as HRV and IR, along with ML techniques, it is possible to create more effective and personalized interventions for managing driver mental workload and preventing cognitive impairment. However, successfully implementing these approaches will require close collaboration between researchers, industry partners, and policymakers to develop reliable, valid, and ethically sound solutions.

One of the main limitations of the current review is the scope of the literature search and the inclusion/exclusion criteria. While efforts were made to conduct a comprehensive review, some relevant studies may have been missed due to the search strategy employed or the databases accessed. Additionally, the quality of the reviewed studies varies, which may affect the reliability and comparability of the findings.

6. Conclusion and Future Work

This review highlights the complex relationship between mental workload, cognitive impairment, and physiological indicators in the context of driving safety. The findings suggest promising avenues for developing driver monitoring systems, adaptive interfaces incorporating physiological measures such as HRV and IR, and ML techniques. However, the research field faces several challenges, such as the lack of standardization in methodologies, the limited diversity in study populations, and the reliance on simulated driving environments. These limitations hinder the generalizability of the findings to real-world driving conditions and may overlook important individual differences in cognitive and physiological responses to mental workload.

Future research should focus on several key areas to address these limitations and advance the field. First, studies should aim to validate the findings from simulator studies in real-world driving conditions to ensure the ecological validity of the results. This may require developing novel methodologies and using advanced sensor technologies to capture driver performance and cognitive states in naturalistic settings. Second, future research should investigate individual differences in cognitive and physiological responses to mental workload, considering factors such as age, driving experience, and cognitive abilities. This will enable the development of more personalized and adaptive interventions for enhancing driving safety. Third, there is a need for greater standardization in methodologies and the development of validated tools for assessing driver mental workload and cognitive impairment. This will facilitate the comparison of findings across studies and the identification of robust patterns and trends. Finally, collaboration between researchers, industry partners, and policymakers is crucial for translating research findings into practical applications. This may involve developing guidelines for the design and implementation of driver monitoring systems and adaptive interfaces and establishing standards for data collection, analysis, and interpretation.The focus of the paper is on investigating the relationships between cognitive impairment, mental workload, and physiological indicators such as heart rate and eye movements in the context of drivers. However, it overlooks other potential factors that could contribute to cognitive impairment in drivers. The study relies on data from a heart rate monitoring system and an eye tracking system, which may not cover the full range of cognitive demands faced by drivers. Including alternative indicators of cognitive workload, like subjective self-assessments or task performance metrics, could provide further valuable insights. Despite the systematic and rigorous review methodology employed in the paper, it is still subject to biases in selecting and evaluating research articles. As a result, the implications and conclusions of the paper may be limited to drivers and may not be easily applied to broader populations or different fields of study.

Further investigation is necessary to explore the use of additional indicators of cognitive workload, such as subjective assessments or task performance metrics, to gain a more comprehensive understanding of mental workload and its effects on cognitive impairment. Future studies could examine the effectiveness of interventions or technologies aimed at reducing cognitive impairment caused by mental workload in drivers. This could involve developing and validating innovative technologies capable of monitoring and managing mental workload in real-time situations. There is a need for research that examines the generalizability of the findings beyond the specific driver-focused context. Exploration could be conducted to investigate the impacts of mental workload and cognitive impairment in other sectors like healthcare or aviation, with the goal of understanding broader implications and potential solutions. Longitudinal studies could be carried out to assess the long-term effects of mental workload on cognitive impairment and identify factors that may influence cognitive performance over time. Prospective research efforts could also explore the interactions between mental workload and factors like age or expertise, to improve our understanding of how these variables may affect cognitive impairment and develop tailored interventions. Despite progress in using physiological measures to assess mental workload, challenges persist in standardizing methodologies and understanding the complex relationship between physiological indicators and cognitive states. Further research is required to explore individual differences in physiological responses and create reliable fatigue detection systems for real-world driving conditions. While heart rate appears promising as an indicator of mental workload during driving, more research and refinement of methodologies are needed to establish its effectiveness across various driving situations and populations. Integrating multiple assessment approaches, such as physiological sensors and cognitive tests, can improve the accuracy and reliability of assessing mental workload in driving scenarios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M. and C.C.; methodology, M.R.; formal analysis, M.A and M.R; investigation, M.R; resources, C.C and B.M; writing—original draft preparation, M. R, M.A, M.M, C.C and B.M.; writing—review and editing, M.M, M.A, M.M, C.C and B.M.; visualization, C.C; supervision, C.C and B.M; project administration, C.C and B.M.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data was created.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviation

| Abbreviation |

Meaning |

| ACC |

Adaptive Cruise Control |

| A# |

Article number |

| ADASs |

Advanced Driver Assist Systems |

| AVP |

Automated Valet Parking |

| CA |

Collision Avoidance |

| CHF |

Congestive Heart Failure |

| CLM |

Conventional Lane Merge |

| CVD |

cardiovascular disease |

| DBMHGS |

Driving Behaviour Model in Haptic Guidance System |

| DiR |

Delays in Response |

| DMQ |

Decision-Making Questionnaire |

| DRT |

Detection Response Task |

| DS |

Driving Simulator |

| EMG |

Electromyography |

| FaTt |

Field & Track test |

| FCA |

Forward Collision Avoidance |

| FFT |

Fast Fourier Transform |

| HMI |

Human Machine Interface |

| HMM |

Hidden Markov Model |

| HR |

Heart Rate |

| IVIS |

In-Vehicle Infotainment System |

| JLM |

Joint Lane Merge |

| LF |

Low Frequency |

| LKA |

Lane-Keeping Assistance |

| LOO |

Leave-one-out |

| LR |

Literature Review |

| MANCOVA |

Multivariate Analysis of Covariance |

| MAT |

Mathematical Arithmetic Task |

| ML |

Machine learning |

| MMDRT |

Measured Maximum Driver Torque |

| MWL |

Mental Workload |

| NNM |

Neural Network Model |

| OSPAN |

Operation Span |

| PA |

Participants' Accuracies |

| PCA |

Principal Component Analysis |

| RMSE |

Root Mean Square Error |

| RMSSD |

Root-mean-square of the Successive Differences |

| ROC |

Receiver Operation Curve |

| RR |

Respiratory Rate |

| SA |

Situation Awareness scores |

| SALSA |

Sacramento Area Latino Study on Aging |

| SDNN |

Standard Deviation of N–N Intervals |

| Sw&AdT |

Shapiro-Wilk and Anderson-Darling tests |

| TOR |

Take-Over Request |

| VLP |

Vehicle Lateral Position |

| VS |

Vehicular Signals |

References

- Chen, W.; Sawaragi, T.; Hiraoka, T. Adaptive multi-modal interface model concerning mental workload in take-over request during semi-autonomous driving. SICE J. Control. Meas. Syst. Integr. 2021, 14, 10–21. [CrossRef]

- Roesener, C., Sauerbier, J., Zlocki, A., Fahrenkrog, F., Wang, L., Várhelyi, A., ... & Lanati, J. (2017, June). A comprehensive evaluation approach for highly automated driving. In 25th International Technical Conference on the Enhanced Safety of Vehicles (ESV) National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

- Tientcheu, S.I.N.; Du, S.; Djouani, K. Review on Haptic Assistive Driving Systems Based on Drivers’ Steering-Wheel Operating Behaviour. Electronics 2022, 11, 2102. [CrossRef]

- Figalová, N.; Chuang, L.L.; Pichen, J.; Baumann, M.; Pollatos, O. Ambient Light Conveying Reliability Improves Drivers’ Takeover Performance without Increasing Mental Workload. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2022, 6, 73. [CrossRef]

- Kajiwara, Y.; Murata, E. Effect of Behavioral Precaution on Braking Operation of Elderly Drivers under Cognitive Workloads. Sensors 2022, 22, 5741. [CrossRef]

- Perozzi, G.; Oudainia, M.R.; Sentouh, C.; Popieul, J.-C.; Rath, J.J. Driver Assisted Lane Keeping with Conflict Management Using Robust Sliding Mode Controller. Sensors 2022, 23, 4. [CrossRef]

- Eichelberger, A.H.; McCartt, A.T. Toyota drivers' experiences with Dynamic Radar Cruise Control, Pre-Collision System, and Lane-Keeping Assist. J. Saf. Res. 2016, 56, 67–73. [CrossRef]

- Park, D.; Yoon, W.C.; Lee, U. Cognitive States Matter: Design Guidelines for Driving Situation Awareness in Smart Vehicles. Sensors 2020, 20, 2978. [CrossRef]

- Murtaza, M.; Cheng, C.-T.; Fard, M.; Zeleznikow, J. Preparing drivers for the future: Evaluating the effects of training on drivers’ performance in an autonomous vehicle landscape. Transp. Res. Part F: Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2023, 98, 280–296. [CrossRef]

- Murtaza, M.; Cheng, C.-T.; Fard, M.; Zeleznikow, J. Assessing Training Methods for Advanced Driver Assistance Systems and Autonomous Vehicle Functions: Impact on User Mental Models and Performance. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2348. [CrossRef]

- Marquart, G.; Cabrall, C.; de Winter, J. Review of Eye-related Measures of Drivers’ Mental Workload. Procedia Manuf. 2015, 3, 2854–2861. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Sawaragi, T.; Hiraoka, T. Comparing eye-tracking metrics of mental workload caused by NDRTs in semi-autonomous driving. Transp. Res. Part F: Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2022, 89, 109–128. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S. H., & Ji, Y. G. (2019). Non-driving-related tasks, workload, and takeover performance in highly automated driving contexts. Transportation research part F: traffic psychology and behaviour, 60, 620-631.

- Ko, S.M.; Ji, Y.G. How we can measure the non-driving-task engagement in automated driving: Comparing flow experience and workload. Appl. Ergon. 2018, 67, 237–245. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Vaezipour, A.; Rakotonirainy, A.; Demmel, S.; Oviedo-Trespalacios, O. Exploring drivers’ mental workload and visual demand while using an in-vehicle HMI for eco-safe driving. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2020, 146, 105756. [CrossRef]

- Sriranga, A.K.; Lu, Q.; Birrell, S. A Systematic Review of In-Vehicle Physiological Indices and Sensor Technology for Driver Mental Workload Monitoring. Sensors 2023, 23, 2214. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Barua, S.; Ahmed, M.U.; Begum, S.; Aricò, P.; Borghini, G.; Di Flumeri, G. A Novel Mutual Information Based Feature Set for Drivers’ Mental Workload Evaluation Using Machine Learning. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 551. [CrossRef]

- Cardone, D.; Perpetuini, D.; Filippini, C.; Mancini, L.; Nocco, S.; Tritto, M.; Rinella, S.; Giacobbe, A.; Fallica, G.; Ricci, F.; et al. Classification of Drivers’ Mental Workload Levels: Comparison of Machine Learning Methods Based on ECG and Infrared Thermal Signals. Sensors 2022, 22, 7300. [CrossRef]

- Biondi, F., Coleman, J. R., Cooper, J. M., & Strayer, D. L. (2017). Heart rate detection for driver monitoring systems. In Transportation Research Board 96th Annual Meeting Washington DC, United States.

- Lu, K.; Dahlman, A.S.; Karlsson, J.; Candefjord, S. Detecting driver fatigue using heart rate variability: A systematic review. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2022, 178, 106830. [CrossRef]

- Piechulla, W., Mayser, C., Gehrke, H., & König, W. (2003). Reducing drivers’ mental workload by means of an adaptive man–machine interface. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 6(4), 233-248.

- Li, G.; Chung, W.-Y. Detection of Driver Drowsiness Using Wavelet Analysis of Heart Rate Variability and a Support Vector Machine Classifier. Sensors 2013, 13, 16494–16511. [CrossRef]

- Makhtar, A.K.; Sulaiman, M.I. Development of Heart Rate Monitoring System to Estimate Driver’s Mental Workload Level. IOP Conf. Series: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 834, 012057. [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Piedra, C.; Sebastián, M.V.; Di Stasi, L.L. EEG Theta Power Activity Reflects Workload among Army Combat Drivers: An Experimental Study. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 199. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-C.; Wang, C.-C.; Yao, Y.-H.; Wu, W.-T. Identification of a High-Risk Group of New-Onset Cardiovascular Disease in Occupational Drivers by Analyzing Heart Rate Variability. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 11486. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. S., Chung, P. C., Wang, W. H., & Lin, C. W. (2010, October). Driving conditions recognition using heart rate variability indexes. In 2010 Sixth International Conference on Intelligent Information Hiding and Multimedia Signal Processing (pp. 389-392). IEEE.

- Mahachandra, M., Sutalaksana, I. Z., & Suryadi, K. (2012, July). Sensitivity of heart rate variability as indicator of driver sleepiness. In 2012 Southeast Asian Network of Ergonomics Societies Conference (SEANES) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- Ma, J.; Feng, X. Analysing the Effects of Scenario-Based Explanations on Automated Vehicle HMIs from Objective and Subjective Perspectives. Sustainability 2023, 16, 63. [CrossRef]

- Persson, A.; Jonasson, H.; Fredriksson, I.; Wiklund, U.; Ahlstrom, C. Heart Rate Variability for Classification of Alert Versus Sleep Deprived Drivers in Real Road Driving Conditions. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2020, 22, 3316–3325. [CrossRef]

- Shakouri, M.; Ikuma, L.H.; Aghazadeh, F.; Nahmens, I. Analysis of the sensitivity of heart rate variability and subjective workload measures in a driving simulator: The case of highway work zones. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2018, 66, 136–145. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).