1. Introduction

Safety has become a paramount concern across industries, with particular emphasis in automotive and manufacturing sectors. The European Union’s implementation of more stringent regulations and requirements has significantly accelerated research and development in both vehicle and human monitoring systems. A central focus of this expanded research is the assessment of drowsiness and attention levels in drivers and workers. Various monitoring methods are currently deployed in industrial settings. For drivers specifically, the most widely adopted approach involves analyzing driving behavior through multiple parameters: evaluation of driving patterns, assessment of traffic response times, and monitoring of steering wheel inputs [

1]. Further solutions - used in the case of workers as well - measure physiological parameters and characteristics of the subject: one can measure yawning [

2], the rate of blinking, eyelid closure, head pose or the change of gaze direction and gaze duration [

3,

4] from the videofeed of a frontal camera. In addition to the previous ones, contact-based devices are used more frequently, such as a pulse oximeter or electrocardiography (ECG) to measure heart rate and heart rate variability [

5,

6]. These statistics also provide an additional feature as an early diagnostic tool for diseases or disease onset. There are examples for hybrid techniques as well using multiple methods at the same time which prove the effectiveness of mixing methods. Although there are other methods utilizing electroencephalography (EEG), electrooculography (EOG) and electromyography (EMG), the viability of these are questionable in industrial use due to uncomfortable and bulky setups.

This paper presents an integrated, real-time software solution for attention and drowsiness evaluation. Our system combines multiple state-of-the-art components into a unified pipeline, incorporating head pose estimation, yawning detection, gaze tracking, and blink pattern analysis. The software is optimized for GPU acceleration. We provide the complete implementation as open-source code under the GNU Public License, enabling further development and practical applications.

2. Methodology

Given the real-time performance requirements and potential resource constraints of target environments, we implemented our system in C++. The graphical user interface was developed using Qt Creator IDE ([

7]),

2.1. Face Detection

For the initial face detection, that precedes facial landmark detection, we chose an advanced RetinaFace of [

8] based on the survey [

9]. RetinaFace achieved top 2 score across the precision-recall curves on the WiderFace easy, medium and hard test sets, as well as on the ROC curve of FDDB benchmark. The face detected with the highest confidence is chosen in the camera image. Due to the nature of the training sets and the training methods, the image (detected face) in the bounding box is rescaled (stretched) to the input size of the facial landmark detection neural network, even if this means distortion of the face.

2.2. Facial Landmark Detection

The resulting face image is then used as the input of the facial landmark detector, for which we evaluated a number of networks available for C++ implementation, based on a facial landmark survey [

10]. Our first choice was the MobileFAN network [

11], which seemed fast and promising. It has an Encoder-Decoder architecture of a convolutional-deconvolutional network, employing knowledge distillation to reduce the size of a ResNet50 to a much smaller and faster MobileNetV2. The knowledge-distillation uses feature-similarity and feature-aligned distillation with heatmap regression. Based on [

10] it achieves a good 3.45 inter-ocular normalized mean error (NME) on the 300-W test dataset. Despite not being the best performing network, it was crucial to take runtime into account as well, where MobileFAN excelled with its 0.72 GFlops (giga floating-point operations). However, recreating the original training method on the same 300-W dataset [

12] with 68 facial landmarks, and even enhancing the training set visibly did not yield the expected results. Next, we tested the pretrained models of PFLD68 from [

13] and PIPNet68 from [

14] both being top contenders speedwise and achieving a 3.37 and 3.19 inter-ocular NME. While PFLD performed well on the 300-W dataset, PIPNet68 visibly outperformed it in the case of the critical landmarks around the eyes. It is worth mentioning that while Google’s MediaPipe Face Landmarker [

15] offers a well documented, easy-to-use neural network solution, according to our tests, it does not detect the landmark points of the eyes correctly: it does not take it into account, whether the eyes are closed or not. Both RetinaFace (MobileNet0.25 version) and the chosen landmark detector PIPNet68 were ultimately integrated using Lite Ai Toolkit [

16].

2.2.1. Head Pose

The head pose estimation is used to correct the different metrics (yawning, eye closure) by the pitch and yaw of the face according to the camera view angle. It uses the detected 68 landmark points. First, the camera intrinsic parameters and lens distortion should be calibrated. For this a chessboard pattern can be used with OpenCV’s findChessboardCorners() and calibrateCamera() functions. Additionally, we use a generic 3D face model as the bases of 2D-3D point projection provided by [

17] (In-the-wild aligned model). The point projection uses OpenCV’s [

18] more robust solvePnPRansac perspective-n-point implementation with the default values and the calibrated parameters to get the translation and rotation vectors. Initializing an

,

,

as middlepoint - corresponding to the nose on the model - using OpenCV’s projectPoints with the translation and rotation vector, and yet again the calibrated camera parameters and distortion, one gets the point where the head is pointing towards. The resulting reprojected points show the direction of the face with values for the pitch, yaw and roll of the head. Using these values to modify an initial, generic attention box set to be in front of the face, the box mimics the attention field of the monitored worker or driver.

2.2.2. Yawning

Once the facial landmark points are acquired, yawning detection is performed using the landmarks of the mouth. The 3-3 points of the lower and the upper lips are normalized using the pitch and yaw of the face, then averaged to get the centroid of each lip. Finally, the Euclidean distance of the normalized centroids is calculated and divided by the Euclidean distance of the two normalized corner points of the mouth. The result is thresholded at an experimentally determined value, which means an open enough mouth for yawning. At the same time, a sliding window determines whether the mouth was open for at least 2 seconds to qualify for yawning, so that normal speech is avoided for detection. It should be kept in mind that covering or masking the mouth while yawning makes detection not possible, and so this measurement is only auxiliary.

2.2.3. Eye Closure

The Eye Aspect Ratio (EAR) defined in [

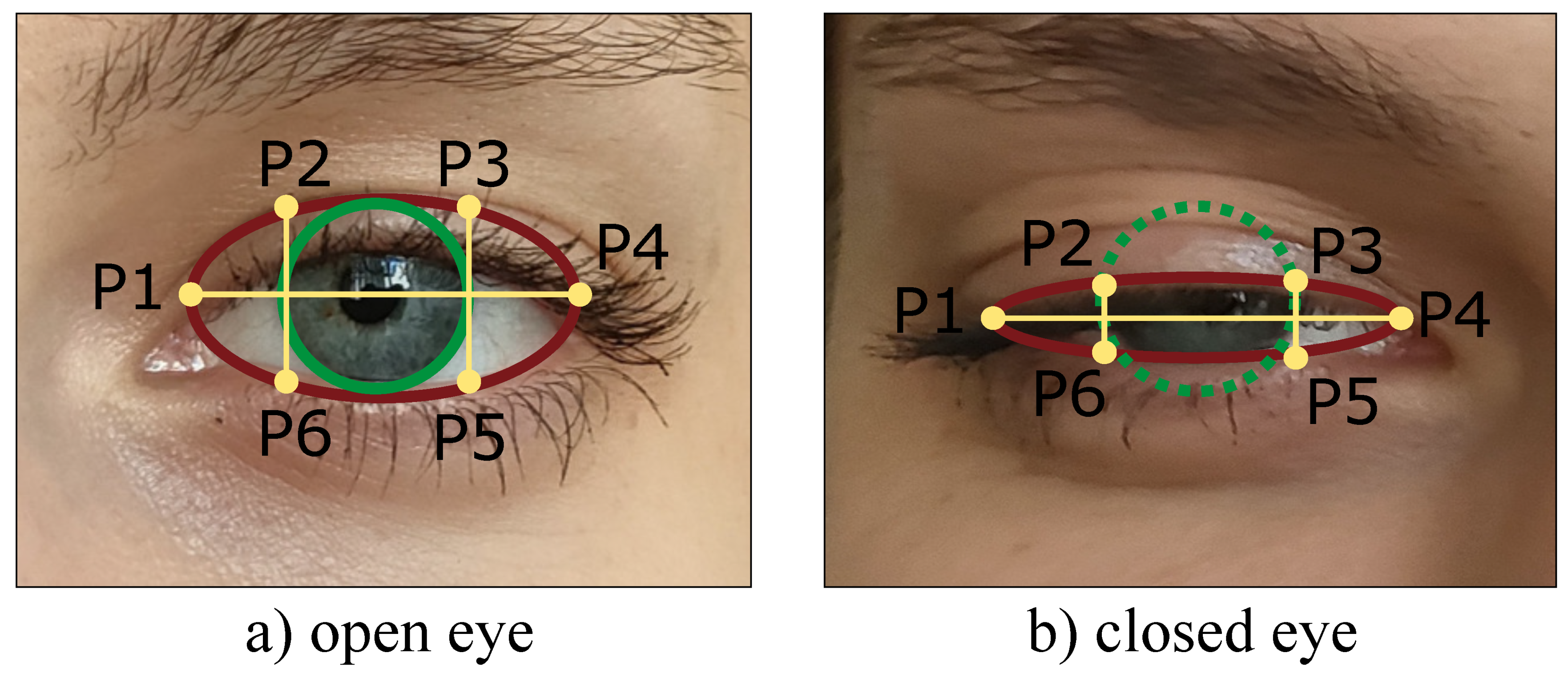

19] is used to distinguish between the open and closed states of the eye. It is a scalar value that indicates the degree of openness or closure of the eye. The EAR value is calculated using six landmarks around the eyes, as shown in

Figure 1. The formula for calculating EAR is given by Equation

1.

Once the facial landmarks are normalized according to the pitch and yaw of the face, the vertical center length is determined by averaging the distances between P2-P6 and P3-P5. This length is then divided by the distance between the horizontal centers (P1-P4) to obtain the EAR ratio. Then, the average of the EAR values of the two eyes is calculated. When comparing the resulting ratio with a chosen threshold, we can determine if the eye is open or closed. Experimental thresholds vary, and some sources, such as [

19], use values such as 0.2, 0.25, or 0.3 for closed eyes. However, based on our analysis of several samples, we found it more effective to use the threshold value of 0.25 in our setup.

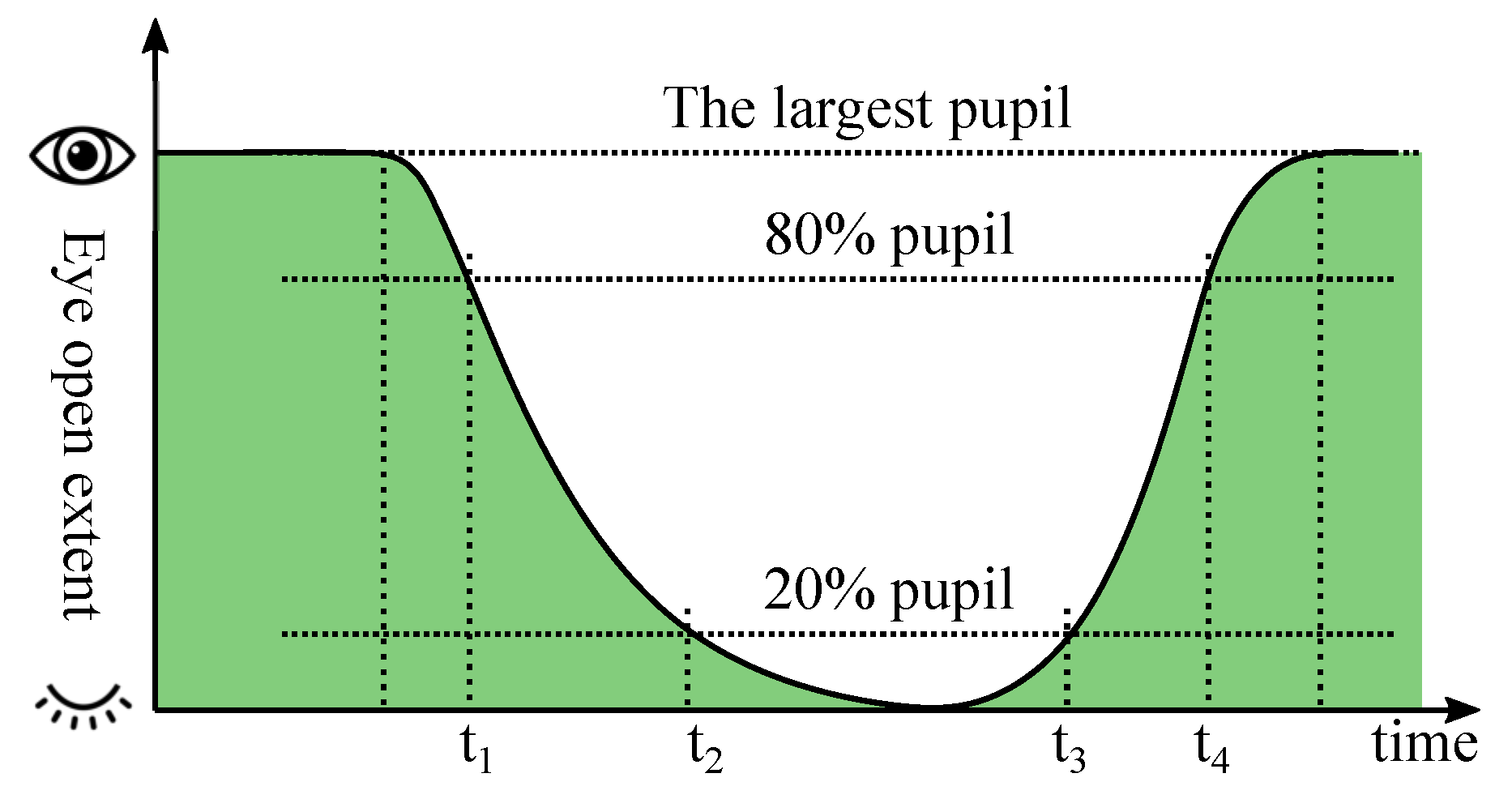

One significant dynamic visual cue for assessing fatigue is the measurement of the Percentage of Eye Closure (PERCLOS), as stated in [

20]. It focuses on extracting relevant information from the closure times between different openness percentages of the eyes. The PERCLOS metric is calculated as follows:

where

represents the PERCLOS value in percentage. Variables

,

,

, and

denote specific time intervals during eye closure and opening.

corresponds to the time it takes for the eyes to close from fully open to 80% closed,

measures the duration from 80% closed to 20% closed,

represents the time from 20% closed to 20% open, and

indicates the time spent with the eyes open from 20% to 0% closure. By computing the ratio of the time intervals multiplied by 100, PERCLOS is obtained as a percentage value.

Figure 2 illustrates the used variables in the context of the PERCLOS measurement.

In addition to PERCLOS, another parameter that can be measured to assess fatigue is the Average Eye Closure Speed (AECS), as used in [

21]. AECS is calculated as the average speed of eye closure or opening over a fixed time period. Relying on a single measurement of PERCLOS is not sufficient due to it being derived from facial landmarks with a possibility of errors. To obtain a more reliable and robust assessment of fatigue, a running average over 30 seconds is used both for PERCLOS and AECS.

2.3. Gaze Detection

Measuring the direction of the gaze is very important for attention evaluation. One can set work spaces to count gaze as "focused", measure out-of-workspace gazing, or apply security measurements if the worker is not watching their work. For this purpose, we added a state-of-the-art gaze estimation neural network called L2CS-Net [

22], which outperforms other SOTA methods [

23]. The network achieves an accuracy of 3.92°and 10.41°on MPIIGaze and Gaze360 datasets, respectively. Moreover, L2CS-Net is suitable for real-time running, as its backbone network is a lighter ResNet-50 architecture. Using yet again the bounding box provided by RetinaFace, we are running L2CS-Net at 50 FPS on GPU to get constant pitch and yaw values for the gaze.

2.4. Pulse Detection

Recent neural network based methods are generally more robust and reliable than classical ones. We chose the backbone of our candidate network to be the PhysNet architecture (see [

24]), which is a state-of-the-art network for pulse extraction. It is an end-to-end spatio-temporal 3D convolutional network, where the input is a sequence of RGB face images (without special pre-processing steps) and the output being the corresponding pulse signal extracted from the face. Once again, the face images are provided by RetinaFace. PhysNet is trained in a supervised manner. Both NTHU DDD ([

25]) and DROZY ([

26]) datasets include only near infrared images. With the lack of a suitable driver or robotcell worker drowsiness or rPPG RGB image database, we chose to use a non-specific, public rPPG database, MMSE-HR ([

27]). Furthermore, we started building our own dataset for the driving scenario to further train the network. Despite many non-public driver datasets being recorded using simulators, we decided to collect real-life recordings in an urban scenario.

Based on the paper [

24] we implemented PhysNet128-3DCNN-ED in PyTorch 1.10 ([

28]). We used a batch number of 16 during training on MMSE-HR. As a consequence to this relatively small batch number, to increase stability and inference performance, we changed all batch normalization layers to group normalization with a group number of 4. During training, we used recordings of the first 10 subjects of MMSE-HR (subject IDs F013-F018, F020, M010-M011), with measurements of all tasks done. Note, that for each subject we had to align the reference to the video manually. The training achieved best performance on the test set after 10 epochs. Next, we further trained the network on our own database consisting of 4 subjects with a total of 32 minutes in the training set - recorded on the streets of Budapest downtown - with the same hyperparameters for 8 epocs.

To create the database, we used a Basler acA1440-220uc camera (Basler AG, Ahrensburg, Germany) with Theia ML410M optics (Theia Technologies, Wilsonville, OR, USA) for the image acquisition. We first tested the commonly used Contec CMS50D+ pulse oximeter (Contec Medical Systems CO.,LTD, Qinhuangdao, Hebei Province, China) for the PPG reference, but then changed to the more precise, but less motion-robust, medical-grade APMKorea ICOM+ SpO2 modul (APMKorea, Daejeon, Hoseo region, Korea with a soft, reusable finger sensor. Because of safety reasons, participants were sitting in the passenger’s seat. They were asked to continuously mimic the driver - they were asked to turn their heads similarly, look around and talk. The camera was mounted in front of them on the windshield at around 10 cm below head-level, using a suction cup. The pulse oximeter was applied and tightly taped around the participants’ intermediate phalanx to fix it well against motion and to shield against light, but let blood circulate well.

3. Results and Discussion

Currently there is no universally defined metric for what is considered to be a yawn, or when a blink is slow or drowsy based on visual expressions. Therefore, we had to experimentally determine the threshold values. For yawning the threshold was determined to be best at

. We considered using a time constraint - the length of yawning - as well, but often the person tries to omit the yawning fast and so it turned out not to be useful. For EAR measurement, we found an optimal value of

indicating that the eyes are open. A typical blink duration ranges from 150 to 250 ms according to ([

29]). The PERCLOS measurement method is originally designed to be used on the pupil. Without a sufficient pupil detector integrated so far, we are using a calibration method at the start of the application consisting of three steps:

measuring normal open state for 5 seconds,

measuring fully open eyes for 5 seconds,

measuring closed eyes for 5 seconds.

During this, we calculate a baseline for average closed and open eye states. When measuring the average closed state of the eyes, we observe a slight offset of approximately 0.05 compared to a fully closed state (0 value). This offset is likely due to factors such as individual variations in eye behavior or measurement inaccuracies. To calculate the openness of 20% and 80% of the eye, we take this offset into account in Equations

3,

4. To determine the openness range, we start by subtracting the average EAR value for the fully closed state from the average EAR value for the fully open state. This difference reflects the extent of openness. Finally, to account for the observed offset during calibration, we add the offset value to the calculated values, which is exactly the fully closed average state value:

where

is the fully opened EAR value,

is the fully closed EAR value, and

is the offset value.

At 50 FPS on an NVidia Geforce RTX 3070 (laptop version) corresponding to 20ms between measurements, we record a state when the openness reaches (

and

) or leaves the thresholds (

and

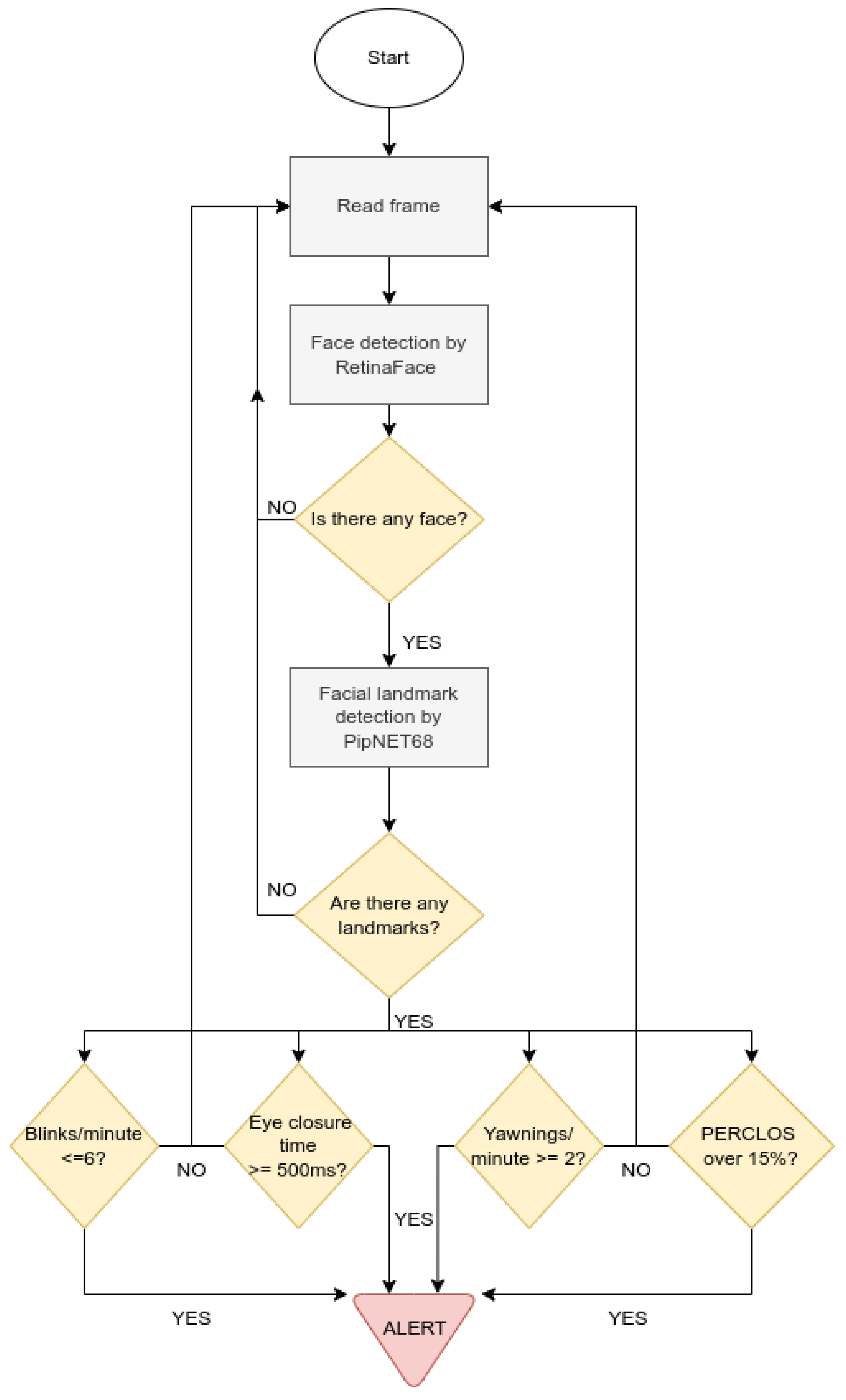

). The software makes a decision of being drowsy if either one of the followings apply: the number of blinks exceeds 6 per minute or the duration of the eye closure exceeds 500 milliseconds (set by [

30]), if the number of yawns exceeds 2 per minute (set by [

31]), or if the PERCLOS exceeds 15% per minute in accordance with [

32]), illustrated by

Figure 3.

Moreover, utilizing the face detection neural network, we are raising a warning when the worker or driver has another face detected too close to them, which is an indicator of someone who can be distracting. The proximity is simply measured in plane: it is in the field of view of the camera; and in dept: based on the similarity of the bounding box sizes namely if the disturbing person’s bounding box is at least 75% of the observed person.

The gaze detection can be used whether the observed person pays attention to the field of action. In our evaluation code this is done by setting an experimentally determined interval for both pitch and yaw, which essentially represents a space where the work is done, and the worker should focus. The results of the network is averaged in a ten-second sliding window, and if the average is outside of the set workspace, the observed person does not pay attention to the field of action and a warning is raised.

The accuracy of the pulse detection heavily depends on the illumination and the movement of the subject. We trained our implementation of the PhysNet128-3DCNN-ED version of the PhysNet architecture [

24] described in the paper as well as with modifications on the MMSE-HR dataset [

27], and fine-tuned it on our custom dataset collected from the passenger’s seat in a driving scenario on the streets of Budapest downtown using synchronised camera and PPG recordings. Our best performing model achieved a Pearson correlation of 0.66 between the ground truth and prediction on the independent validation set consisting of a total of 21 minutes recordings of two subjects in the urban driving scenario. However, it can perform much better in properly illuminated, near stationary scenarios, and as such, it is part of the open-source code. Pulse rate variability detection based on camera image is an unsolved problem due to inaccuracy of the pulsewave detection.

4. Conclusions

In this paper, we presented a real-time software pipeline that integrates state-of-the-art methods for monitoring driver and worker drowsiness and attention levels. The implementation is openly available on GitHub under the GNU Public License (GPL) (see Data Availability Statement). It can be used to evaluate the existing methods or compare new ones to them as well.

While our implementation demonstrates the potential of current technologies, it also reveals several limitations that highlight drowsiness detection remains an open research challenge. The current PERCLOS implementation was adapted to work with eye detection rather than pupil tracking, and future development will incorporate pupil detection to enhance both PERCLOS measurements and gaze tracking accuracy. Additionally, the pulse detection component requires far better performance and consistency for practical implementation. Although each component in our system represents validated state-of-the-art technology, comprehensive evaluation of the complete system’s precision requires an extensive database with annotated drowsiness and attention states. Furthermore, the current decision tree implementation has inherent vulnerabilities: yawning detection fails when subjects cover their mouths, and blinking detection - outside of a worker paradigm - cannot be used at all when subjects wear sunglasses. These limitations suggest the need for future research into an AI-based system capable of intelligently evaluating and integrating outputs from multiple components.

Funding

The research was supported by the ÚNKP-22-3 New National Excellence Program of the Ministry for Innovation and Technology from the source of the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund and by the European Union within the framework of the National Laboratory for Autonomous Systems (RRF-2.3.1-21-2022-00002).

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Arefnezhad, S.; Samiee, S.; Eichberger, A.; Nahvi, A. Driver drowsiness detection based on steering wheel data applying adaptive neuro-fuzzy feature selection. Sensors 2019, 19, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapik, M.; Cyganek, B. Driver’s fatigue recognition based on yawn detection in thermal images. Neurocomputing 2019, 338, 274–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamidele, A.A.; Kamardin, K.; Syazarin, N.; Mohd, S.; Shafi, I.; Azizan, A.; Aini, N.; Mad, H. Non-intrusive driver drowsiness detection based on face and eye tracking. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ed-Doughmi, Y.; Idrissi, N.; Hbali, Y. Real-time system for driver fatigue detection based on a recurrent neuronal network. Journal of Imaging 2020, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kundinger, T.; Sofra, N.; Riener, A. Assessment of the potential of wrist-worn wearable sensors for driver drowsiness detection. Sensors 2020, 20, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujiwara, K.; Abe, E.; Kamata, K.; Nakayama, C.; Suzuki, Y.; Yamakawa, T.; Hiraoka, T.; Kano, M.; Sumi, Y.; Masuda, F.; et al. Heart rate variability-based driver drowsiness detection and its validation with EEG. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2019, 66, 1769–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- TheQtCompany. Qt Creator - Embedded Software Development Tools & Cross Platform IDE. https://www.qt.io/product/development-tools, 2022. Accessed: 2023-07-06.

- Deng, J.; Guo, J.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, J.; Kotsia, I.; Zafeiriou, S. Retinaface: Single-stage dense face localisation in the wild, 2019.

- Minaee, S.; Luo, P.; Lin, Z.; Bowyer, K. A: Deeper Into Face Detection, 2021; arXiv:cs.CV/2103.14983].

- Khabarlak, K.; Koriashkina, L. Fast Facial Landmark Detection and Applications: A Survey. Journal of Computer Science and Technology 2022, 22, e02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Shen, C.; Gao, Y.; Xiong, S. Mobilefan: Transferring deep hidden representation for face alignment, 2019.

- Sagonas, C.; Tzimiropoulos, G.; Zafeiriou, S.; Pantic, M. 300 Faces in-the-Wild Challenge: The First Facial Landmark Localization Challenge. In 2013 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops; 2013; pp. 397–403. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. PyTorch Face Landmark: A Fast and Accurate Facial Landmark Detector, 2021.

- Jin, H.; Liao, S.; Shao, L. Pixel-in-Pixel Net: Towards Efficient Facial Landmark Detection in the Wild. International Journal of Computer Vision 2021, 129, 3174–3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugaresi, C.; Tang, J.; Nash, H.; McClanahan, C.; Uboweja, E.; Hays, M.; Zhang, F.; Chang, C.L.; Yong, M.G.; Lee, J.; et al. MediaPipe: A Framework for Building Perception Pipelines. arXiv 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, Y. lite.ai.toolkit: A lite C++ toolkit of awesome AI models., 2021. Open-source software available at https://github.com/DefTruth/lite.ai.toolkit.

- Baltrusaitis, T.; Zadeh, A.; Lim, Y.C.; Morency, L.P. OpenFace 2.0: Facial Behavior Analysis Toolkit. 2018 13th IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face; Gesture Recognition (FG 2018). [CrossRef]

- Bradski, G. The OpenCV Library. Dr. Dobb’s Journal of Software Tools.

- Dewi, C.; Chen, R.C.; Chang, C.W.; Wu, S.H.; Jiang, X.; Yu, H. Eye aspect ratio for real-time drowsiness detection to improve driver safety. Electronics 2022, 11, 3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Shi, J.; Wang, G.; Yang, J.; Zhang, G. Effective Driver Fatigue Monitoring through Pupil Detection and Yawing Analysis in Low Light Level Environments. Journal of Signal Processing Systems 2014, 77, 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Q.; Yang, X. Real-Time Eye, Gaze, and Face Pose Tracking for Monitoring Driver Vigilance. Real-Time Imaging 2002, 8, 357–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelrahman, A.A.; Hempel, T.; Khalifa, A.; Al-Hamadi, A.; Dinges, L. L2CS-net: Fine-grained gaze estimation in unconstrained environments. 2023 8th International Conference on Frontiers of Signal Processing (ICFSP) 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Wu, C.; Lin, K.; Liu, T. HG-Net: Hybrid Coarse-Fine-Grained Gaze Estimation in Unconstrained Environments. In Proceedings of the 2023 9th International Conference on Virtual Reality (ICVR); 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Li, X.; Zhao, G. Remote Photoplethysmograph Signal Measurement from Facial Videos Using Spatio-Temporal Networks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.02419. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, C.H.; Lai, Y.H.; Lai, S.H. Driver drowsiness detection via a hierarchical temporal deep belief network. Computer Vision – ACCV 2016 Workshops. [CrossRef]

- Massoz, Q.; Langohr, T.; Francois, C.; Verly, J.G. The ULG multimodality drowsiness database (called DROZY) and examples of use. 2016 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV) 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Girard, J.M.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, P.; Ciftci, U.; Canavan, S.; Reale, M.; Horowitz, A.; Yang, H.; et al. Multimodal spontaneous emotion corpus for human behavior analysis. 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam Paszke, Sam Gross, S.C.G.C. PyTorch: An Imperative Style, High-Performance Deep Learning Library. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32; Wallach, H.; Larochelle, H.; Beygelzimer, A.; d’Alché-Buc, F.; Fox, E.; Garnett, R., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc., 2019; pp. 8024–8035.

- Kurylyak, Y.; Lamonaca, F.; Mirabelli, G. Detection of the eye blinks for human’s fatigue monitoring. In 2012 IEEE International Symposium on Medical Measurements and Applications Proceedings; 2012; pp. 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.; Rahaman, N.; Ahad, M.A.R. A study on tiredness assessment by using eye blink detection. Jurnal Kejuruteraan 2019, 31, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Wu, R. Real-time driver-drowsiness detection system using facial features. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 118727–118738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Chew, M.T.; Demidenko, S. Eye tracking system to detect driver drowsiness. ICARA 2015 - Proceedings of the 2015 6th International Conference on Automation, Robotics and Applications. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).