Introduction

An essential part of many ruminant operations is a well-managed grazing system. Goats provide a low-impact, high-forage efficiency grazing experience. They are partial to woody, weedy, and brush like forage [

1]. This makes goats desirable for grazing areas that would not be optimal for larger ruminants such as cattle. Goats have also been recognized as valuable in managing brush in pastures, farmland, and rangeland, leading to significant improvements in the growth of desirable grasses and legumes while reducing the presence of undesirable species [

2].

In the United States, continuous grazing is the most commonly used grazing practice, but there has been some exploration into rotational grazing practices [

3,

4]. Rotational grazing is a form of grazing that allows the use of multiple pastures during a grazing cycle. While continuous grazing may produce higher farm profitability with greater livestock productivity, rotational grazing over time may lead to higher quantity and quality of forage production, increased livestock product yield per acre, and suppressed weed growth [

4]. Soil quality was also reported to improve within a few years by using goats in a rotational grazing system, thereby assisting in soil regeneration [

5,

6]. Using rotational grazing, farmers can extend the grazing season, better control the timing and intensity of forage grazed by cattle, allow a rest period optimal for regrowth, renew carbohydrate stores, and improve persistency and yield [

7]. Previous studies reported that rotational grazing had an average of 7% higher forage production, and in humid regions, this increased to 20-30% higher forage production [

4]. However, rotational grazing requires more management, and longer rest periods compared to continuous grazing [

8]. It is important to understand the impact of rotational goat grazing practices in Kentucky to advise local small farmers the most suitable grazing practices. The objectives of this study are to observe the effects of rotational and continuous grazing on forage performance and goat performance. We hypothesized that rotational grazing would support higher forage production and better goat performance.

Materials and Method

2.1. Study Site

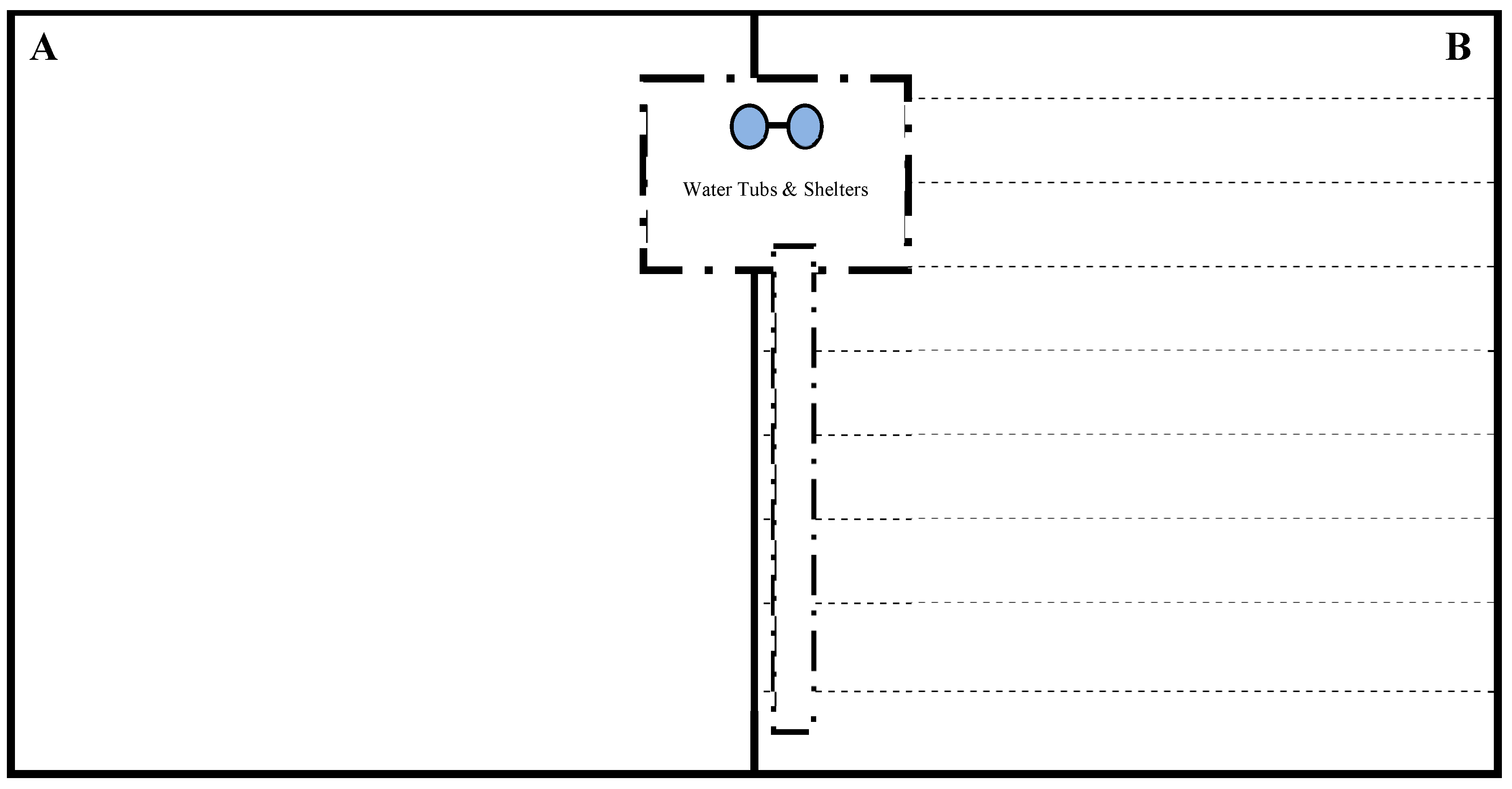

This study was conducted at Kentucky State University’s Harold R. Benson Research & Demonstration Farm from June 2016- September 2016. Two pastures, each measuring two acres (one hectare), side by side, and with similar forage and makeup, were the designated pastures for this study. The plot diagram is illustrated in

Figure 1. The continuous field, represented by

Figure 1A, used a perimeter fence, a watering tub, and a temporary shelter. The rotational field, represented by

Figure 1B, was set up with a watering tub, temporary shelter, a perimeter fence, and a temporary electrical fence for rotational plot borders, where the field was broken up into 9 equal smaller plots.

2.2. Treatments

The treatments consisted of rotational grazing and continuous grazing management, each involving a group of 10 mature does.

Rotational Grazing: The rotational field was split into nine sub-pastures inside the pasture. The goats in this pasture were limited to grazing the forage available in the section for seven days. The goats were provided with a temporary shade and shelter area. The watering tub was also placed in this area to keep the water cooler longer. A temporary electrical fence was used as a border and as a safety barrier from predators. The temporary fence and the goats were moved every seven days. Following the full rotation of all nine sub-pastures the goats rotated back to the first sub-pasture and began the rotation again. The rotational grazing system allowed each sub-pasture to have 8 weeks of rest and recovery. The project was conducted for 14 weeks. The project was terminated one month early when the forage on both pastures had not recovered enough to supply sufficient forage for the goats.

Continuous Grazing: Goats on the continuous grazing pasture had free access to the entire pasture during the project. The pasture on the continuous field was equally equipped with shade and water, with each shelter area parallel to the other. An electrical wire was carried along the inside perimeter of the fence to ensure that the goats stayed in, and predators stayed out. A herding dog stayed in this pasture the entire time for safety purposes. Due to the drought in the summer of 2016, this treatment was also terminated at the same time as the rotational treatment.

2.3. Forage Performance

Before the start of the project (June 9, 2016), a random sample of forage was collected in both fields. Measurements were obtained by throwing a one-foot square made of PVC pipe overhead; a sample was collected wherever the square landed. This was repeated six times to ensure randomization. The samples analyzed at the University of Kentucky for chemical composition.

The forage height in each field was measured on the first day of the project (06/16/16) and every seven days thereafter. One set of measurements was collected each week in the continuous field. In the rotational field, a set of measurements was collected weekly before the goats entered each rotational pasture and after the goats finished grazing in the same pasture. For each measurement, forage height was measured at 3 random spots with a grazing stick to acquire an average height. This measurement is an estimate of forage production in pounds. It was estimated that 10 inches of forage growth at 100 pounds per inch are equal to 1000 pounds of plant dry material per acre [

9]. In our study, the measurements were kept in inches rather than converting to pounds of plant dry material per acre.

Soil samples were taken before the start of the project (06/09/16) and sent to the University of Kentucky laboratory for analysis using the soil data 3.0 program. This soil test was performed to determine the properties of the soil in both pastures in order to establish a baseline for future studies.

2.4. Animal Performance

Ten mature does were used on each pasture. At the start of the project (June 9, 2016), the initial body weight of does was taken on a single-animal livestock scale. This was repeated a month later (July 14, 2016) and again at the end of the project (September 28, 2016). The Faffa Malan Chart, FAMACHA, score was determined with an eyelid scorecard by comparing a range of colors on the scorecard to the color of the goat’s eyelids [

10]. The colors on the scorecard were: 1 – Red, 2 – Red-pink, 3 – Pink, 4 – Pink-white, 5 – White. A score of 1-2 is optimal in showing healthy goats, while 4-5 shows the presence of anemia, which signals the presence of worms. If a goat is not dewormed, it can become severely anemic and have dire consequences. This is a primary way to determine if a goat or a herd needs dewormer treatments [

10].

Graphs were created to illustrate the results using Microsoft Excel (version 365; Redmond, WA, USA).

3.0. Results and Discussion3.1. Forage Performance

Table 1 shows the chemical composition of forage from both the continuous and rotational pastures.

Table 2 displays the chemical composition of forage from these pastures before the project began. Our results on soil chemical composition and forage quality are only preliminary and intended to serve as a reference for future studies. Nyakatawa et al. [

11] showed that goat grazing took several years to affect soil chemical properties such as pH and NH

4-N. A long-term study with at least 3 years is recommended to observe any soil regenerative process, such as soil enrichment and improving forage yields [

6].

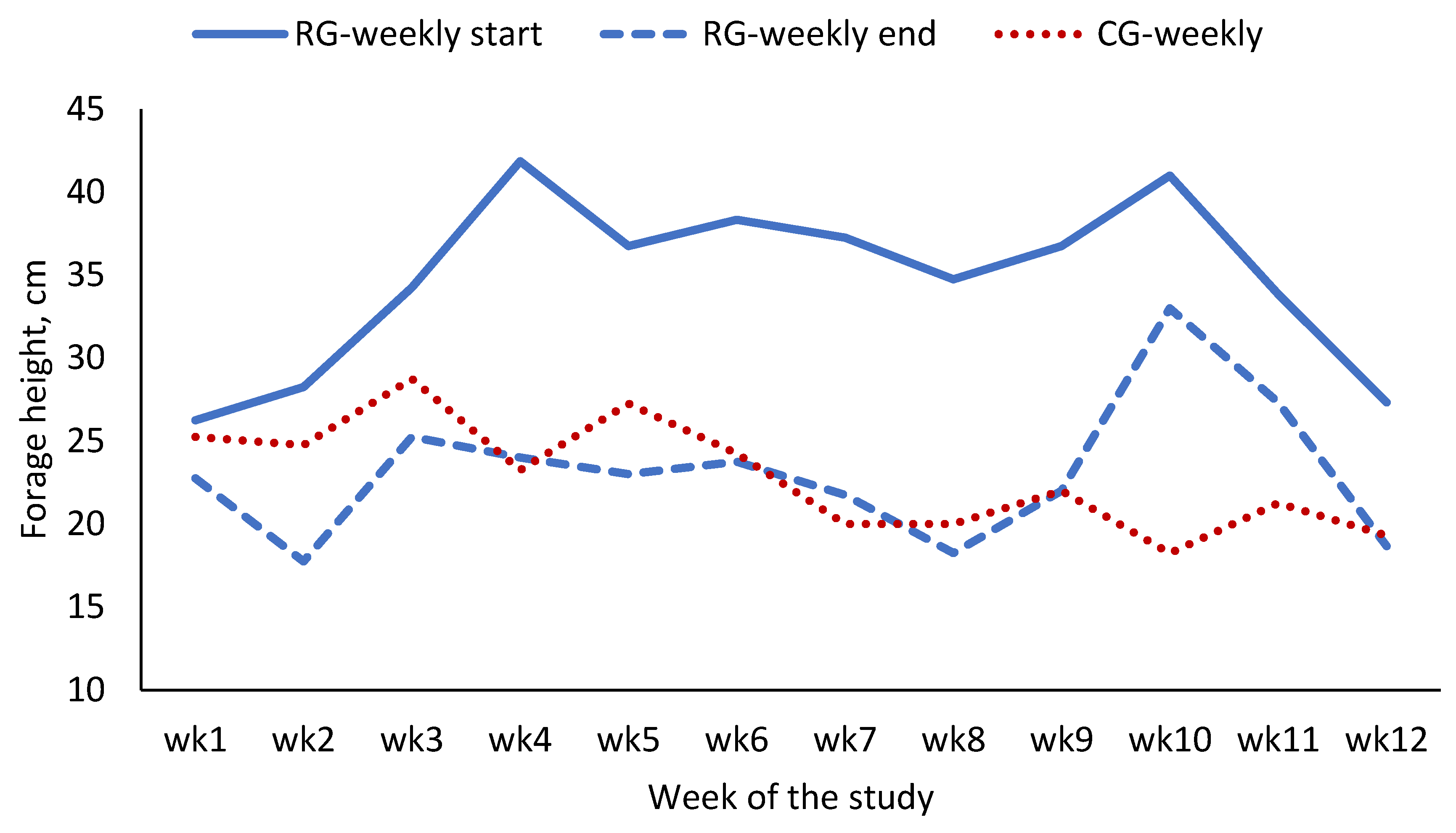

Figure 2 shows the weekly average forage height of the continuous pasture, as well as the weekly average forage height of the rotational pasture before and after goat grazing. The continuous pasture had minimum fluctuations in forage height across the weeks, while the rotational pasture had high forage height before goat grazing and low forage height after goat grazing, as anticipated. The rotational pasture experienced a more uniform grazing pattern across the limited area. Because this group was limited to a sub-area of the field, the goats in this group grazed the entirety of the section. At the end of each week, there were small areas that were overgrazed on the rotational field, but there were no bare areas. Overgrazed areas are areas with more desirable forage, which were the first choice of goats [

12]. On the continuous grazing pasture, the more desirable pasture areas experienced intense grazing pressure. This reduced the recovery time for the forage, leading to bare patches, wilted plants, and overly grazed areas.

3.2. Animal Performance

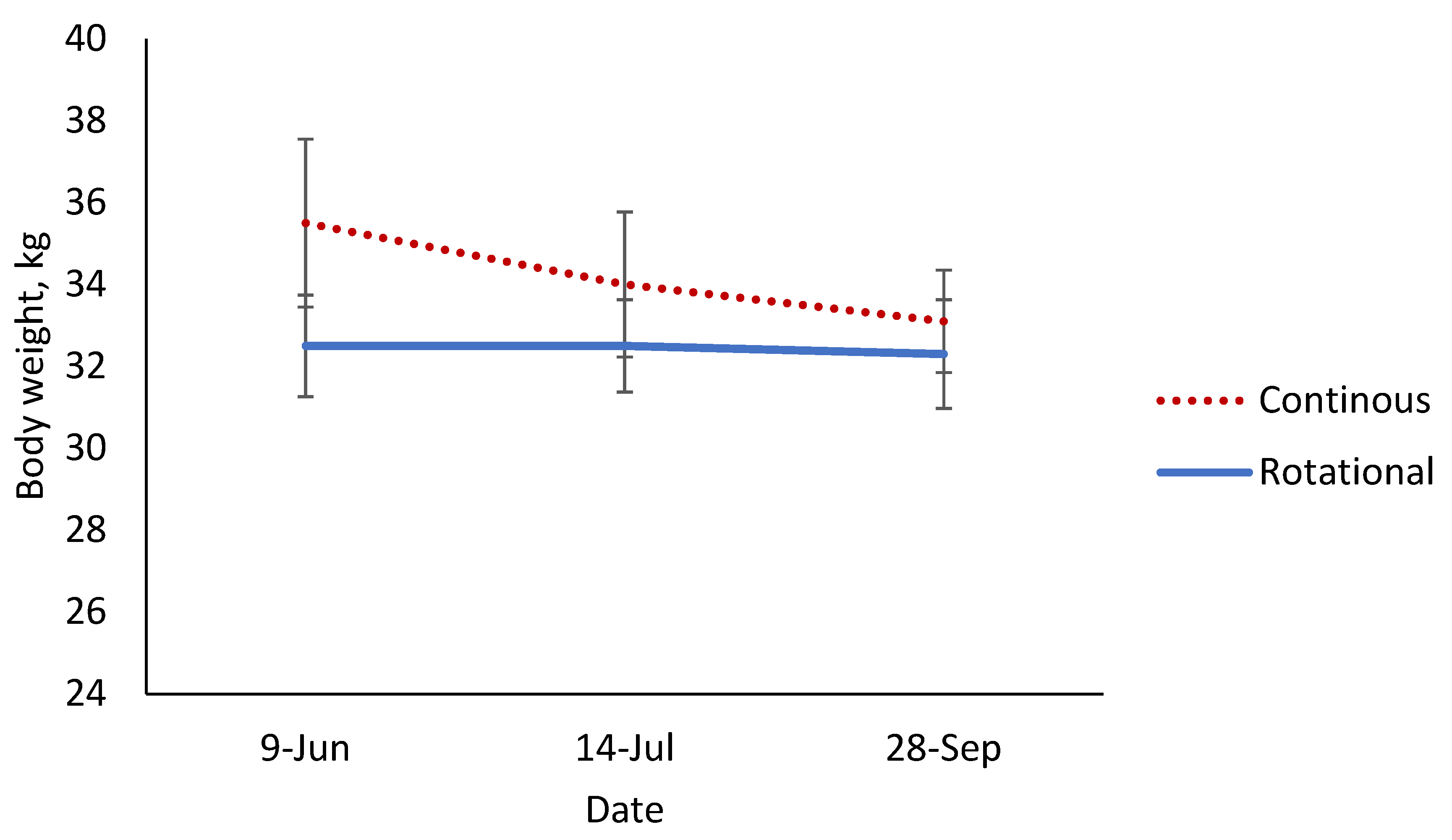

Figure 3 shows the average weight of the goats in each grazing field at the beginning, middle, and end of the study. Goats grazing the continuous field had average body weights 35.5, 34, and 33.1 kg. for the dates 06/09/2016, 07/14/2016, and 09/28/2016, respectively. For the rotational grazing group, the body weights were 32.5, 32.5, and 32.3 kg for the dates of 06/09/2016, 07/14/2016, and 09/28/2016, respectively. From the beginning to the end of the study, goats grazing the continuous field had a steady decline in body weight from 35.5 to 33.1 kg while goats grazing the rotational field had more consistent body weights. The continuous grazers had access to the entire field during the study, which allowed the goats to be more selective in what they were consuming, which resulted in bare spots with no forage, wilted forage, and over-foraged areas. Ideally, the goats would need to either maintain their weight or experience increased weight. The rotational field was better able to maintain the original weights of the goats.

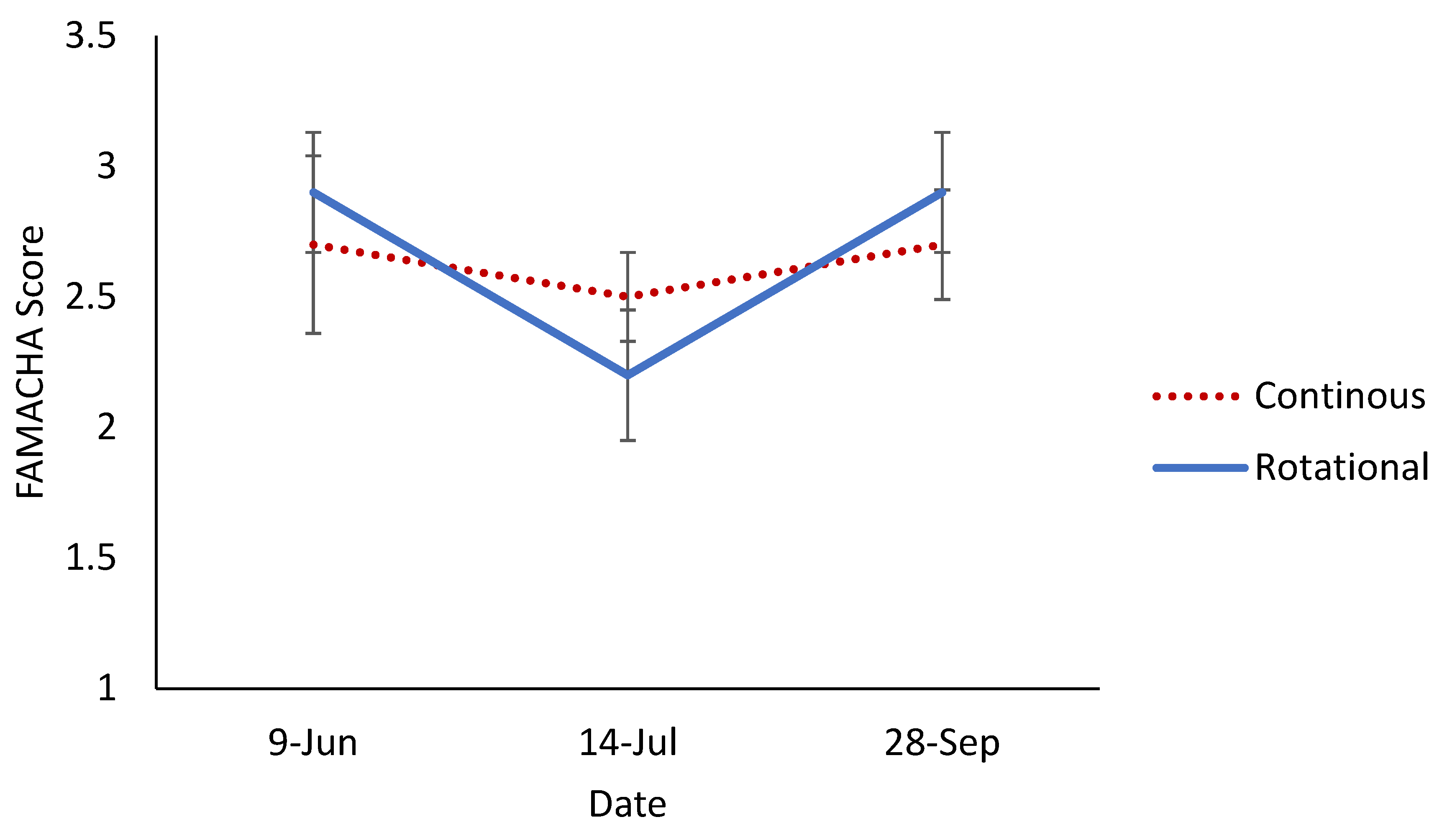

For the continuous grazing meat goats, the eye color scores (FAMACHA scores, Table 3,

Figure 4) were 2.7, 2.5, and 2.7 for the dates of 06/09/2016, 07/14/2016, and 09/28/2016, respectively, while for the rotational grazing goats, the FAMACHA scores were 2.9, 2.2, and 2.9 for the dates of 06/09/2016, 07/14/2016, and 09/28/2016, respectively. The goats were dewormed right before they were placed on the fields, which kept reoccurring worm infestations considerably low. The eye color scores on the continuous field were more consistent throughout the duration of the study. For the rotational field, the eye color scores began at 2.9, decreased to 2.2 at the midpoint, but increased back to 2.9 at the conclusion of the study. In the rotational grazing group, the decrease in eye color score in the middle of the project might be due to abundant forage available and less selectiveness in the pastures, which led to more even grazing and decreased worms and parasite infection. During the drought at the end of the study, some areas took longer to recover and did not fully recover to optimal forage heights, similar to those previously observed [

13]. Due to drought and insufficient forage, the FAMACHA score of goats in the rotational grazing system returned to its initial state by the end, suggesting that more comprehensive management and timely adjustments are essential for maintaining optimal goat performance.

Initially, the study was designed to continue into early fall, but the study was terminated early due to decreased forage yields and animal health. During this study, there were long periods of drought and record-high temperatures. Consequently, the health of the goats became the biggest concern. The goal was to minimize human intervention; however, there was an increase in the frequency of watering the goats and constant monitoring of the available forage. When forage was running low in the rotational pasture, the goats were moved a day earlier than expected. Toward the end of the project, there were a few days of rain and constant storms, which delayed the transitioning of the goats by one day. Weather conditions are always a factor in outdoor studies; therefore, it is important to include remediations for future studies.

Conclusion

The overarching purpose of this study was to investigate whether rotational grazing could improve goat performance and forage growth compared to continuous grazing. In our study, the goats in the continuous pasture experienced weight loss, raising concerns about forage availability and overgrazing in some areas using the continuous grazing practice. Rotational grazing supported more consistent forage yields and goat body weights but only temporarily improved the eye color scores in the middle of the project. Future studies should be conducted across multiple fields and over several years to provide more experimental units and increase statistical power. This study should be considered observational.

Author Contributions

T.C-C designed and carried out the experiment, analyzed the data and wrote the first draft manuscript. B.G and M.G contributed to the design of the experiment and reviewed the manuscript. H.J.A. contributed to the manuscript drafting and revision. Y.J. analyzed the data, reviewed, and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Luginbuhl, J. M.; Mueller, J. P.; Green, J. T., Jr.; Chamblee, D. S.; Glennon, H. M. Grazing and Browsing Behavior, Grazing Management, Forage Evaluation, and Goat Performance: Strategies to Enhance Meat Goat Production In North Carolina. In Strengthening the Goat Industry. Florida A&M University, Tallahassee, FL, September 12-15, 2010, 73-87. Availble online: https://smallruminants.ces.ncsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/LUGINBUHLGrazingBrowsing-Behavior-Management-Grazing-Research.pdf?fwd=no (Accessed on 27 April 2024).

- USDA, Natural Resources Conservation Service. Biological Weed and Brush Control With Sheep and Goats. MO-32. 2002. Available online: https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/cmis_proxy/https/ecm.nrcs.usda.gov%3A443/fncmis/resources/WEBP/ContentStream/idd_70BFF176-0000-C81D-9D7D-F105FE4F2ED3/0/Agronomy+Tech+Note+32.pdf (Accessed on 27 April 2024).

- Teague, R.; Kreuter, U. Managing Grazing To Restore Soil Health, Ecosystem Function, and Ecosystem Services. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 157. [CrossRef]

- Smith, T. Rotation Vs. Continuous Grazing. Hereford World 2007, 24-25. Available online: https://hereford.org/static/files/02_07_RotationVsContinuous.pdf (Accessed on 3 October 2023).

- Mellado, M.; Rodriguez, A.; Olvera, A. Age and Body Condition Score and Diets Of Grazing Goats. J. Range Manage. 2004, 57, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machmuller, M. B.; Kramer, M. G.; Cyle, K. T.; Hill, N.; Hancock, D. W.; Thompson, A. Emerging Land Use Practices Rapidly Increase Soil Organic Matter. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6. [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.; Amaral-Phillips, D.; Lehmkuhler, J. Rotational vs. Continuous Grazing. Master Grazer 2017. Available online: https://grazer.ca.uky.edu/rotational-vs-continuous-grazing (Accessed on 23 April 2023).

- Oregon State University. Forage Information System: National Forage and Grasslands Curriculum 2017. Available online: http://forages.oregonstate.edu/nfgc/eo/onlineforagecurriculum/instructormaterials/availabletopics/grazing/types (Accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Bauman, P. Using The ‘Grazing Stick’ To Assess Pasture Forage. South Dakota State University Extension 2021, 4, 1-4. Available online: https://extension.sdstate.edu/using-grazing-stick-assess-pasture-forage (Accessed on 7 June 2023).

- Wyk, J. V.; Bath, G. F. The FAMACHA System for Managing Haemonchosis In Sheep and Goats By Clinically Identifying Individual Animals For Treatment. Vet. Res. 2002, 33, 509–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyakatawa, E. Z.; Mays, D. A.; Naka, K.; Bukenya, J. O. Carbon, Nitrogen, And Phosphorus Dynamics In A Loblolly Pine-Goat Silvopasture System In The Southeast USA. Agrofor. Syst. 2012, 86, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahieu, M.; Arquet, R.; Fleury, J.; Bonneau, M.; Mandonnet, N. Mixed Grazing Of Adult Goats and Cattle: Lessons From Long-Term Monitoring. Vet. Parasitol. 2020, 280, 109087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, R.; Celaya, R.; García, U.; Osoro, K. Goat Grazing, Its Interactions With Other Herbivores, and Biodiversity Conservation Issues. Small Rumin. Res. 2012, 107, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).