1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM), including type 1 (T1DM) and type 2 (T2DM), is a group of common metabolic endocrine diseases characterized by glucose and lipid metabolic disorder and hyperglycemia [

1]. Among them, T2DM, the most prevalent form, accounts for more than 95% of all diabetic patients. Insulin resistance and insufficient compensatory insulin production are the two main contributors of T2DM [

2,

3]. The pathogenesis of T2DM is extremely complicated, and it is a polygenic genetic disease formed by the combined action of genetic and environmental factors. Firstly, genetic factors are the main factor. Secondly, the development of T2DM is related to the homeostasis of intestinal flora. Acquired factors also have an important impact on the development of T2DM. Obesity, sedentary lifestyle, physical inactivity, high-glycemic and low-fiber diet, vitamin deficiency, smoking and alcohol consumption are complex factors that induce T2DM [

4]. At present, the pathogenesis of T2DM is not completely clear. However, a growing body of research has revealed that T2DM is significantly influenced by a number of variables, including insulin resistance, inflammation, oxidative stress, lipid metabolism disorders, obesity, insulin secretion issues, intestinal flora, and others [

5,

6,

7]. Moreover, T2DM is associated with a series of complications, including microvascular complications, macrovascular complications, renal complications, cardiac complications and diabetic gastroenteropathy, which can significantly lower the patient’s quality of life and even lead to death [

8,

9]. Although recent studies have given a new look to the understanding of T2DM, currently available treatments can only temporarily reduce blood glucose levels, but cannot completely prevent the development of T2DM and its complications. Besides, most of antidiabetic drugs have side effects, such as gastrointestinal symptoms, heart failure, weight gain, edema, impaired kidney function pancreatitis, and genital infections, which become another burden on patients. Therefore, new antidiabetic agents with less side effects are necessary [

10].

Natural medicines have many advantages over traditional medicines, including fewer side effects, lower long-term toxicity and varied bioavailability. Numerous studies indicated that bioactive compounds from herbal medicine, such as polyphenols, flavonoids and alkaloids, have beneficial effects on T2DM prevention and treatment, by improving glucose tolerance, insulin resistance, and other related mechanisms [

11,

12].

Curcumin, a natural polyphenol derived from the rhizome of Curcuma longa (turmeric), which has been widely used in cosmetics, food and pharmaceutical industries, has gained a growing interest in the last years for its pharmacological activities. Different studies demonstrated that curcumin has anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-microbial, anti-atherosclerotic, nephro-protective, anti-cancer, hepato-protective, immunomodulatory, antidiabetic, and anti-rheumatic effects, but with no toxicity [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Numerous studies demonstrated that curcumin could improve insulin resistance, regulate blood lipid metabolism, decrease glucose and insulin levels, reduce the release of inflammatory factors, inhibit oxidative stress and regulate gut microbiota in patients with T2DM [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Given the above, this review aimed to summarize the effects of curcumin on T2DM through anti-inflammatory, free radical scavenging, upregulation of antioxidant enzymes, regulation of blood lipid metabolism, and other pathways.

2. Properties of Curcumin

2.1. Physical and Chemical Properties of Curcumin

The solubility and stability of curcumin depend on its environmental pH. In acidic to neutral pH, curcumin is relatively stable, whereas in alkaline pH, curcumin is unstable and easily degradable. Moreover, the low water solubility (11 ng/mL) of curcumin is a key factor limiting its use. Under acidic and neutral conditions, curcumin exists in keto-form, while under alkaline conditions, it exists mainly in the enol-form. The enol-form of curcumin can provide electrons, so its free radical scavenging activity is mainly contributed by the enol-form. The various activities and biological activities of curcumin depend on its Excited State Intramolecular Hydrogen Transfer (ESIHT) process. Furthermore, the anti-inflammatory activity of curcumin is mainly contributed by two phenolic groups separated by a hydrophobic bridge in an enol center [

24].

2.2. Pharmacokinetics and Toxicology of Curcumin

Numerous investigations have demonstrated that curcumin has low membrane permeability and little absorption in the gastrointestinal tract following oral treatment. Additionally, the low absorption of curcumin might be attributed to its hepatoenteric first pass effect. The rate of absorption is also determined by the delivery route. For instance, compared to intravenous or oral modes of delivery, the intraperitoneal route demonstrated higher levels of curcumin in plasma [

25,

26,

27]. In addition, the highly reactive structure of curcumin leads to its easy degradation, which causes poor distribution to specific locations [

28]. Curcumin is metabolized rapidly in the body and mainly undergoes phase I reduction metabolism, phase II binding metabolism, auto-oxidation and intracellular catalytic oxidation metabolism [

29]. Following a step-by-step hydrogenation process, tetrahydrocurcumin, hexahydrocurcumin and a little quantity of ferulic acid are the primary metabolites of curcumin I phase reduction metabolism. Since the phase I metabolites have the structure of phenolic and alcohol hydroxyl groups, the binding reaction of gluconaldehyde and sulfuric acid occurs in phase II metabolism. The final metabolites of curcumin are mainly glycosylated products and relatively few sulfonated products [

30]. As stated above, curcumin has low penetration, extensive metabolism, low bioavailability and targeting efficacy, which are the main limiting factors for its therapeutic application. Despite its low bioavailability, curcumin still has a wide range of pharmacological activities.

Long-term studies have shown that curcumin is safe and protective when used in the diet. The United States Food and Drug Administration considers curcumin as to be a ‘generally recognized as safe’ product, and clinical trials have shown that it has strong tolerability and safety profiles at doses ranging from 4000 to 8000 mg [

31]. In phase I clinical studies, curcumin with doses up to 3600-8000 mg daily for 4 months did not result in discernible toxicities except mild nausea and diarrhea [

32].

3. Curcumin and T2DM

3.1. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Curcumin on T2DM

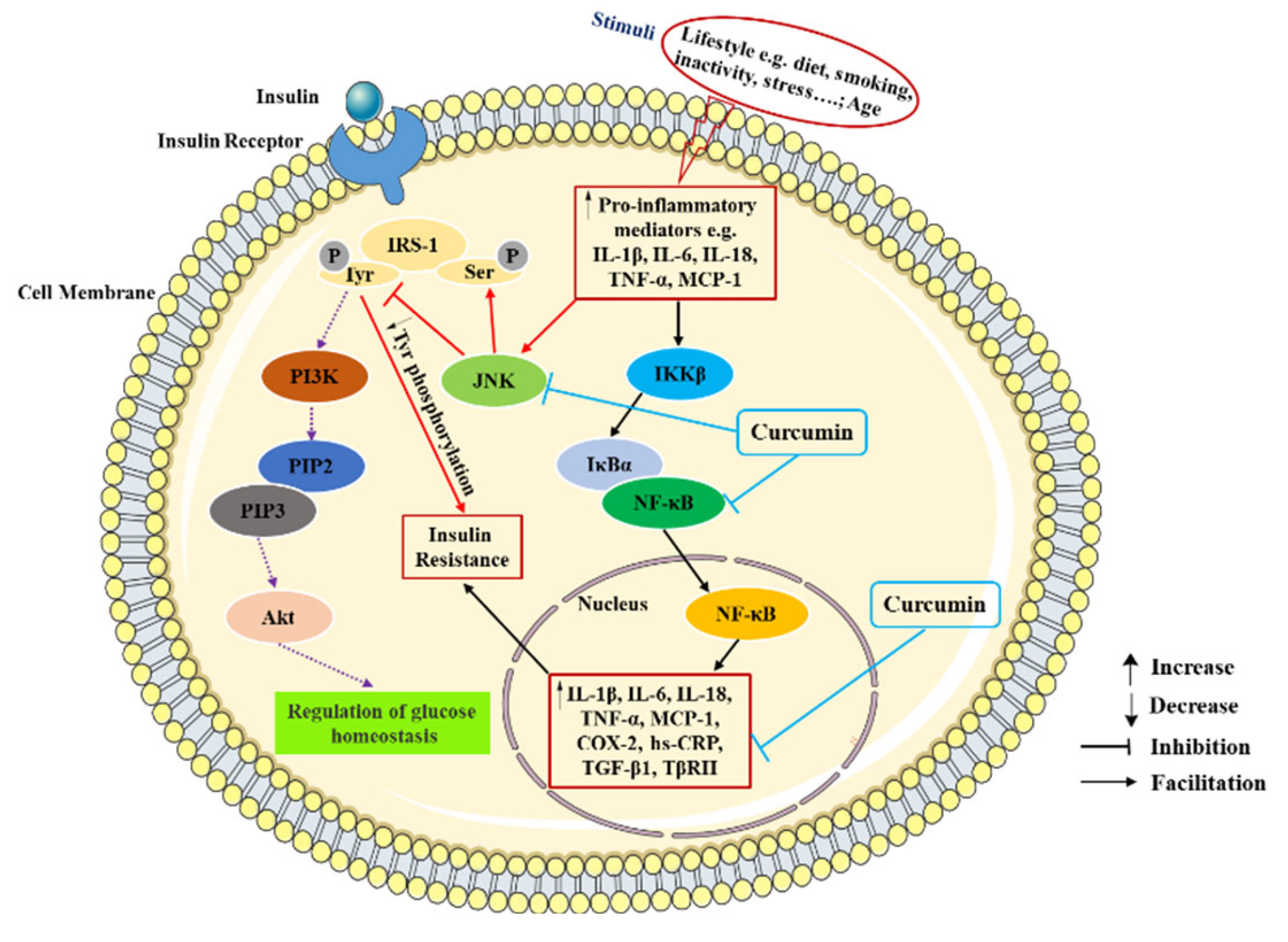

Inflammation is one of the primary pathogenic factors of T2DM and is crucial to the emergence and progression of insulin resistance as well as the rise in blood glucose levels. Conversely, the presence of hyperglycemia might promote insulin resistance and long-term complications [

33]. Through various transcription factor-mediated molecular pathways and oxidative stress, inflammatory responses can activate various pro-inflammatory mediators, especially cytokines, chemokines and adipokines, such as interleukin-1 β (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-18 (IL-18), tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) and transforming growth factor-β1(TGF-β1). These inflammatory mediators reduce tissue insulin-mediated glucose uptake and insulin signal transduction by activating Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) and nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) pathways. In addition, the activation of JNK and NF-κB pathway also promotes the upregulation of various pro-inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α and IL-6, which further aggravates insulin resistance and accelerates the occurrence and development of T2DM [

34,

35,

36].

Several studies have indicated that curcumin exerts protective effect against diabetes through the inhibition of inflammation (

Table 1). The experiments revealed that curcumin treatment reduced the serum inflammatory factors levels of glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), MCP-1, IL-6 and TNF-α in diabetic rats through suppressing the NF-κB pathway [

37]. Abo-Salem et al demonstrated that curcumin dramatically decreased IL-6 and TNF-α secretion in streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rats with heart injury [

38]. A similar study suggested that curcumin significantly suppressed MCP-1, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6 and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) production in adipocytes [

39]. Guo et al demonstrated that curcumin inhibited TGF-β1 and type II TGF-β (TβRII) production and blocked the non-canonical adenosine monophosphate activated protein kinase/p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (AMPK/p38 MAPK) pathway in diabetic rat heart [

40]. A study showed that the curcumin and its analog alleviated diabetes-induced damages by regulating inflammation in brain of diabetic rats [

41]. Another study revealed that the administration of curcumin decreased serum levels of TNF-α and increased serum level of adiponectin [

42]. Adibian et al demonstrated that curcumin supplementation could significantly reduce the concentration of high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) and increase the concentration of adiponectin in patients with T2DM [

43]. Furthermore, curcumin could inhibit the JNK phosphorylation to prevent apoptotic and inflammatory processes in diabetic cardiomyopathy [

44]. In short, these data show that curcumin supplementation fosters anti-inflammatory factors production, such as adiponectin, and reduces the pro-inflammatory cytokines production, such as TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, and MCP-1 in T2DM subjects. The anti-inflammatory effects of curcumin on T2DM are showed in

Figure 1.

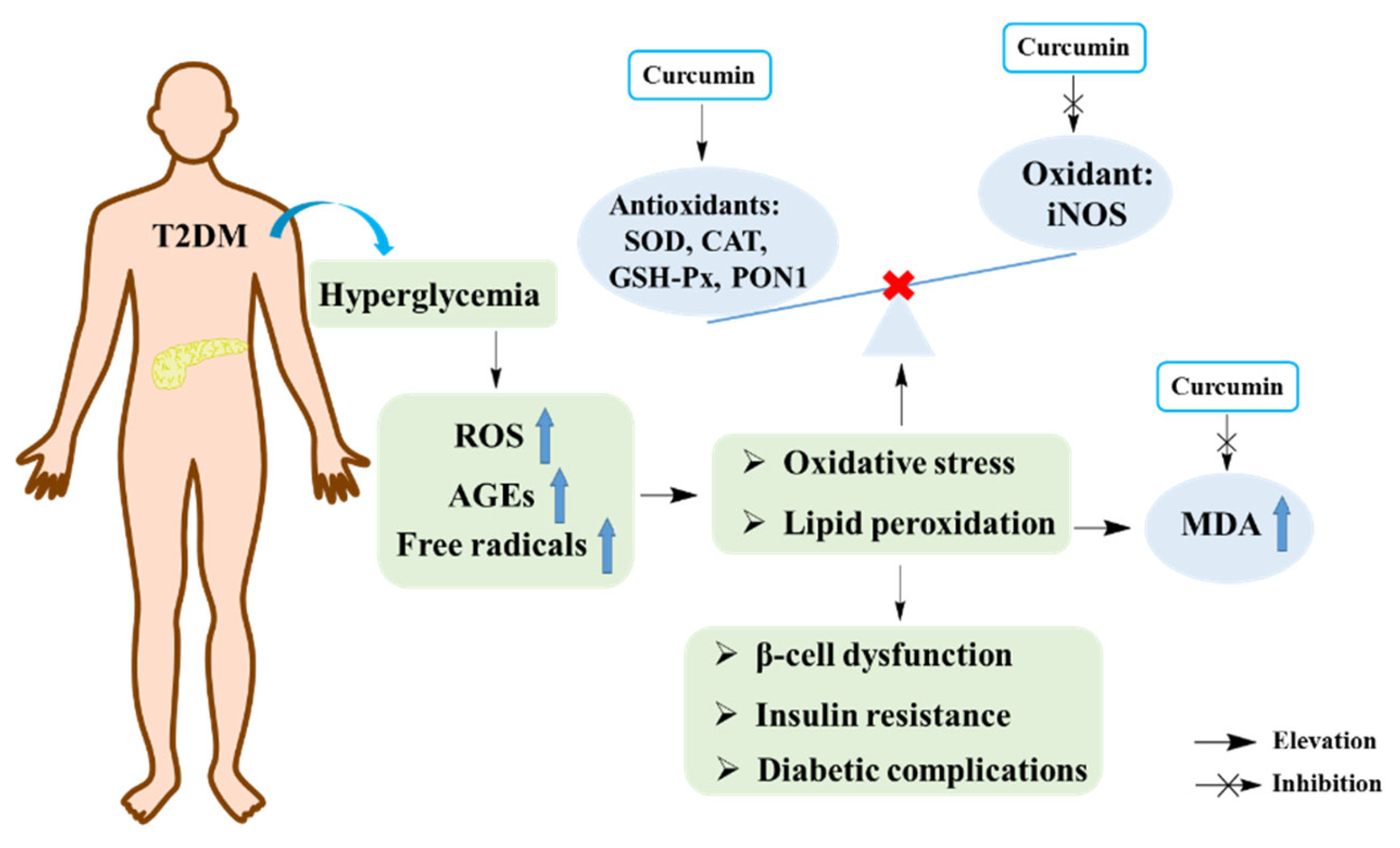

3.2. Anti-Oxidant Effects of Curcumin on T2DM

Many studies have shown that oxidative stress is closely related to the pathogenesis of T2DM [

45,

46]. Hyperglycemia can increase the production of free radicals, which further leads to the occurrence of oxidative stress. In turn, elevated production of free radicals can damage the antioxidant defense system and lead to the generation of glucose-derived advanced glycosylation end products (AGEs). The accumulation of AGEs in the body can induce oxidative damage of cell membranes, cell function damage, enhanced lipid peroxidation, and various complications of T2DM. All of these events eventually lead to pancreatic islet β-cell dysfunction, insufficient insulin secretion and insulin resistance, which aggravate the development of T2DM and its complications [

47,

48,

49]. Generally, the activities of antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) reflect the status of oxidative stress. In addition, the levels of malondialdehyde (MDA), a product of lipid peroxidation, was also used to reflect the level of oxidative stress. Moreover, nitric oxide (NO), a product of inducible nitric oxidesynthase (iNOS), could exacerbate oxidative stress [

48,

50].

Studies indicated that curcumin is a natural antioxidant. A study elucidated that curcumin decreased the amount of MDA and increased the level of SOD as well as diminished the ratio of apoptosis in alloxan (AXN) treated pancreatic islet cells, suggesting that curcumin could be a potential compound for protecting pancreatic islet cells and treating T2DM [

51]. Results from a meta-analysis showed that curcumin had antioxidant effect by lowering MDA levels and increasing SOD activity [

52]. Shafabakhsh et al reported that curcumin administration for 12 weeks in patients with T2DM could improve the values of total antioxidant capacity (TAC), glutathione (GSH), MDA, and the gene expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ) [

53]. In addition, curcumin could decrease lipid peroxidation, likely by increasing ATPase activity, restoring oxygen consumption and NO synthesis in liver and kidneys of diabetic mice, which suggested that curcumin could be a better substitute to prevent and/or treat oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction during obesity and diabetes [

54]. In a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial, the use of curcumin and curcuminoids dramatically lowered the level of MDA in T2DM patients while considerably increasing the activities of TAC and SOD [

55]. Additionally, it was demonstrated that curcumin could not only elevate the activities of SOD, CAT and paraoxonase-1 (PON1), but also increase the amounts of AGEs and detoxification system components (AGE-R1 receptor and glyoxalase-1) in STZ-induced diabetic rats [

56]. The anti-oxidation effects of curcumin on T2DM are exhibited in

Figure 2.

3.3. Effects of Curcumin on Lipotoxicity in T2DM

In addition to hyperglycemia, T2DM patients are often accompanied by lipid metabolism disorder. Elevated circulating levels of lipids and excessive deposition of fat in non-adipose tissues, such as muscle and liver, are known as lipotoxicity [

57]. During the onset and progression of T2DM, lipotoxicity can contribute to or exacerbate insulin resistance, pancreatic β-cell dysfunction, and death [

58]. Furthermore, studies revealed that lipotoxicity in β-cells triggers different stress pathways, especially the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and oxidative stress, which ultimately leading to β-cells dysfunction and death [

59]. In addition, the dysregulation of AMPK and downstream effectors play an important role in the pathogenesis of hepatic steatosis, dyslipidemia, and insulin resistance [

6,

60].

In a double-blind randomized clinical trial, results indicated that curcumin treatment may diminish diabetic complication by reducing the serum levels of triglycerides (TGs) in patients with T2DM [

43]. A study argued that curcumin improves insulin resistance and glucose homeostasis in db/db mice by regulating lipid metabolism. Results showed that curcumin significantly lowered plasma free fatty acids (FFAs), total cholesterol (TC) and TGs concentrations in type 2 diabetic mice. Moreover, curcumin could alter the activities of hepatic fatty acid synthase (FAS), β-oxidation, carnitine palmitoyltransferase (CPT), 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme (HMG-CoA) reductase and acyl-CoA: cholesterol acyltransferase (ACAT) in db/db mice. Furthermore, curcumin increased the lipoprotein lipase (LPL) activity of skeletal muscle in db/db mice [

61]. Another study inferred that the effect of curcumin on insulin resistance might be correlated with the decreases of FFAs and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels in T2DM rats [

62]. Similarly, Belhan et al revealed that curcumin significantly ameliorated lipid profile in STZ-induced diabetic rats [

63]. In addition, results showed that curcumin could inhibit renal lipid accumulation and oxidative stress through AMPK and nu-clear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 (Nrf2) signaling pathway in a rat model of type 2 diabetic nephropathy [

64]. Curcumin and nano-curcumin treatment significantly decreased insulin resistance and serum levels of fasting blood sugar (FBS), apelin, TC, TGs, LDL, and very low-density lipoproteins (VLDL) as well as increased the high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels in diabetic rats. Moreover, the nano-curcumin was more effective in alleviating lipid profile than that of curcumin [

65]. A study performed by Devadasu et al demonstrated that curcumin nanoparticulate administration significantly reduced plasma TGs and TC levels, whilst, increased HDL in STZ-induced diabetic rats [

66]. In a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled phase 2 clinical trial, results indicated that curcumin and zinc co-supplementation along with a loss-weight diet could improve lipid profiles, including TGs, LDL, HDL, non-HDL, and HDL to LDL ratio in patients with prediabetes [

67]. Consistent with these results, Panahi et al reported that curcuminoids treatment could reduce serum levels of TC, non-HDL and Lp(a) as well as elevate HDL levels in patients with T2DM [

68]. Moreover, curcumin ameliorated fat accumulation, serum lipid levels and insulin sensitivity through regulating sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBPs) target genes and metabolism associated genes in liver or adipose tissues in high fat diet-induced obese mice with T2DM [

69]. Given the above, the ameliorative effects of curcumin on T2DM may be related to its regulation of lipotoxicity.

3.4. Effects of Curcumin on Glucose Transport and Metabolism in T2DM

Chronic hyperglycemia and AGEs can lead to tissue oxidative stress and pancreatic β-cell glucotoxicity, causing loss of homeostasis, which further aggravates hyperglycemia [

70]. Therefore, maintaining blood glucose homeostasis might be an effective antidiabetic intervention. Furthermore, the activation of glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) and various enzymes such as glucose 6-phosphate (G6P), phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK), glycogen synthase (GS), and hexokinase (HK) are involved in glucose transport and metabolism. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (Akt) pathway and the activity of AMPK play an essential role in regulating glucose metabolism and energy homeostasis [

71].

Numerous investigations revealed that curcumin is an effective anti-hyperglycemia agent. In a clinical trial, the findings detected that curcumin could improve insulin resistance, lower blood glucose levels and reduce circulating glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta (GSK-3β) as well as islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP) [

72]. Another clinical trial found that the curcumin administration significantly reduced fasting blood glucose (FBG), HbA1c, and estimated average glucose (eAG) levels [

73]. Algul et al demonstrated that oral curcumin administration improved FBG, significantly up-regulated GLUT4 gene expression and improved nesfatin-1[

74]. Chang et al revealed that curcumin enhanced insulin sensitivity and improved glucose intolerance in addition to lowering the FBG and increasing GLUT4 gene expression [

75,

76]. Similar findings came from additional research [

77]. PPARγ play a very important role in the regulation of glucose metabolism. Numerous investigations have demonstrated that curcumin-induced PPARγ activation can inhibit the surface expression of glucose transporter 2 (GLUT2) and AGEs accumulation [

46,

78,

79]. Chuengsamarn et al indicated that curcumin ameliorated the overall performance of β-cells with higher homeostasis model assessment (HOMA-β) and lower C reactive protein (CRP) [

80]. Additionally, studies revealed that curcumin could prevent hyperglycemia by promoting insulin secretion, improving β-cell function and inhibiting β-cell apoptosis [

81,

82,

83]. With regard to the anti-hyperglycemic activity, curcumin presents a viable option for T2DM prevention or treatment.

3.5. Other Effects of Curcumin on T2DM

It is well known that gut microbiota plays a key role in human disease progression. In recent years, high concentrations of curcumin have been detected in the gastrointestinal tract after oral administration, indicating that it can directly interact with the gut microbiota and exert regulatory effects [

84]. It is worth noting that two different phenomena have emerged in the interaction between curcumin and the microbiota: the regulation of curcumin on the gut microbiota and the biotransformation of curcumin by the gut microbiota, both of which may be crucial for the activity of curcumin. Several studies have confirmed that insulin resistance and the onset of T2DM are closely associated with gut microbiome disorders [

85,

86]. An analysis indicated that tetrahydrocurcumin alleviated the blood glucose level, up-regulated the expression of pancreatic glucagon-like peptide-1(GLP-1) and promoted the secretion of insulin by reducing the relative abundance of

Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, and Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio in diabetic rats [

87]. Ren et al. demonstrated that curcumin reduced high glucose-induced apoptosis in cardiomyocytes through the inhibition of JNK phosphorylation in the diabetic heart [

88]. Wang et al investigated that curcumin analog supplement significantly reversed the diabetes-induced cardiac cells apoptosis by decreasing the anti-apoptotic protein (Bcl-2) and improving the breakdown of pro-apoptotic protein (Bax) and caspase-3 in diabetic mice [

89]. Curcumin complement effectively suppressed the elevated Bax/Bcl-2 ratio and ameliorated glucose-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes, accompanied by increased Akt and GSK-3 phosphorylation [

90]. An investigation obtained that curcumin could mitigate T2DM by increasing adiponectin levels and decreasing C peptide levels along with insulin resistance [

80]. Furthermore, curcumin could regulate lysosomal enzyme activities in diabetes [

91].

4. Conclusions and Perspectives

A variety of studies have detected that curcumin can ameliorate T2DM via various mechanisms, but effects may be affected by the type of curcumin, dose, bioavailability, treatment time and the study design [

92]. Therefore, these factors should be considered when investigating the antidiabetic mechanisms of curcumin. The utilization of curcumin to treat T2DM have some limitations like poor solubility, low instability, low bioavailability, low penetration, extensive metabolism, and targeting efficacy [

93]. Among these, the main hurdle of curcumin therapeutic application in T2DM is its poor bioavailability. Some methods were designed to enhance the solubility, durability, and bioavailability of curcumin. For instance, the bioavailability of curcumin can be improved by combining with piperine and other bioavailability enhancer or constructing curcumin complex [

31]. In addition, the emergence of nanobiotechnology, such as liposomes, microemulsion, hydrophilic prodrugs, solid nanoparticles, polymer micelles and nanogels, has opened up broad opportunities for exploring and expanding the application of curcumin in the medical field. Compared with regular curcumin, nano-curcumin has better half-life, absorption capacity, better drug delivery ability and high bioavailability [

94]. Moreover, research on new drug delivery systems and novel stabilizers is required to enhance the drug release time, stability in various digestive fluids, encapsulation effectiveness, and potential cytotoxic effects. Exosomes are membrane derived nanoscale vesicles (30-150nm) that are released from different cell types under normal or pathological conditions and affect receptor cell activity by inducing signaling pathways. Exosomes vesicles carry various bioactive molecules (such as nucleic acids, proteins, and lipids) and participate in intercellular communication, as well as various physiological and pathological processes through various mechanisms [

95]. Exosomes have unique advantages such as strong loading capacity, low immunogenicity, good penetration performance (including various physiological barriers such as Blood-brain barrier), good biocompatibility, biodegradability, and non-toxicity. They are a natural carrier system with endogenous and cellular tendencies [

96]. Exosomes, as new drug delivery carriers of traditional chinese medicine monomers, have been widely used in various fields. A study indicated that exosomes loaded with curcumin has a good therapeutic effect on diabetes skin defects [

97]. Additionally, synthesis of curcumin analogues is also one of the effective methods to enhance its biological activity [

31]. Furthermore, the development of new drug delivery methods is also a favorable approach.

The antidiabetic mechanism of curcumin is complex and networked. However, prior studies have not thoroughly examined curcumin’s pharmacological mechanism. Therefore, it is necessary to use systems biology methodology to study the mechanism of curcumin. In addition, the antidiabetic activity of curcumin is mainly carried out in animal and cell models and there are few clinical data. Hence, comprehensive research on the hypoglycemic effect of curcumin requires extensive clinical trials. Besides, the development of new pathways, targets, and therapeutic combinations play important roles in the study of the hypoglycemic effect of curcumin. As is well known, different doses of drugs have different effects, therefore, subsequent research should also pay attention to the dosage of curcumin. It is worth noting that challenges related to the utilization of plant medicines include insufficient bioavailability and inconsistent commercially available product quality. Therefore, it is imperative to develop optimized formulas and standardized extraction methods. Furthermore, it is necessary to conduct a comprehensive investigation into the safety, long-term effects, and potential drug interactions of curcumin.

In view of the increasing incidence rate of T2DM worldwide, it is very important to find effective drugs for T2DM. Curcumin, the major curcuminoid of turmeric, has various positive benefits on T2DM. Numerous studies, including animal and clinical studies, have provided strong evidence to support curcumin’s crucial role in T2DM prevention due to its anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant, anti-hyperglycemic, anti-apoptotic, anti-hyperlipidemia, and other actions. As stated above, curcumin has good hypoglycemic effect and is tolerated well at high doses, without adverse effects. Hence, is a promising prevention/treatment option for T2DM.

Author Contributions

Yujin Gu: methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing-reviewing and editing; Qun Niu: validation, investigation, writing-reviewing and editing. Qili Zhang: methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation; Yanfang Zhao: methodology, investigation, and writing-original draft preparation;.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This is a review article. It has not involved any human subjects and animal experiments.

Acknowledgments

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflict of interest.

References

- Afsharmanesh, M.R.; Mohammadi, Z.; Mansourian, A.R.; et al. A Review of micro RNAs changes in T2DM in animals and humans. J Diabetes 2023, 15, 649–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patergnani, S.; Bouhamida, E.; Leo, S.; et al. Mitochondrial oxidative stress and “mito-inflammation”: Actors in the diseases. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghorbani, Y.; Schwenger, K.J.P.; Allard, J.P. Manipulation of intestinal microbiome as potential treatment for insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 8, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Ding, Y.; Tanaka, Y.; et al. Risk factors contributing to type 2 diabetes and recent advances in the treatment and prevention. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2014, 11, 1185–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snelson, M.; de Pasquale, C.; Ekinci, E.I.; et al. Gut microbiome, prebiotics, intestinal permeability and diabetes complications. Best Pract. Res. Cl. En. 2021, 35, 101507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Noh, S.; Lim, S.; et al. Plant extracts for type 2 diabetes: from traditional medicine to modern drug discovery. Antioxidants. 2021, 10, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, J.A.; Uryash, A.; Lopez, J.R.; et al. The endothelium as a therapeutic target in diabetes: A narrative review and perspective. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 638491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forbes, J.M.; Cooper, M.E. Mechanisms of diabetic complications. Physiol. Rev. 2013, 93, 137–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurniawan, A.H.; Suwandi, B.H.; Kholili, U. Diabetic gastroenteropathy: A complication of diabetes mellitus. Acta Med. Indones. 2019, 51, 263–271. [Google Scholar]

- Gregg, E.W.; Williams, D.E.; Geiss, L. Changes in diabetes-related complications in the United States. New Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 286–287. [Google Scholar]

- Demmers, A.; Korthout, H.; van Etten-Jamaludin, F.S.; et al. Effects of medicinal food plants on impaired glucose tolerance: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pr. 2017, 131, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinayagam, R.; Xu, B. Antidiabetic properties of dietary flavonoids: a cellular mechanism review. Nutr. Metab. 2015, 12, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayati, Z.; Ramezani, M.; Amiri, M.S.; et al. Ethnobotany, phytochemistry and traditional uses of Curcuma spp. and pharmacological profile of two important species (C. longa and C. zedoaria): A review. Curr. Pharm. Design 2019, 25, 871–935. [Google Scholar]

- Urošević, M.; Nikolić, L.; Gajić, I.; et al. Curcumin: Biological activities and modern pharmaceutical forms. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 135. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, S.; Monteiro-Alfredo, T.; Silva, S.; et al. Curcumin derivatives for type 2 diabetes management and prevention of complications. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2020, 43, 567–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naeini, M.B.; Momtazi, A.A.; Jaafari, M.R.; et al. Antitumor effects of curcumin: A lipid perspective. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 14743–14758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultana, S.; Munir, N.; Mahmood, Z.; et al. Molecular targets for the management of cancer using Curcuma longa Linn. Phytoconstituents: A review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 135, 111078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.J.; Huang, S.Y.; Zhou, D.D.; et al. Effects and mechanisms of curcumin for the prevention and management of cancers: An updated review. Antioxidants. 2022, 11, 1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, B.; Li, J.; Cao, H. Antioxidant and antiinflammatory activities of curcumin on diabetes mellitus and its complications. Curr. Pharma. Design. 2013, 19, 2101–2113. [Google Scholar]

- Gutierres, V.O.; Assis, R.P.; Arcaro, C.A.; et al. Curcumin improves the effect of a reduced insulin dose on glycemic control and oxidative stress in streptozotocin-diabetic rats. Phytother. Res. 2019, 33, 976–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Moselhy, M. A.; Taye, A.; Sharkawi, S. S.; et al. The antihyperglycemic effect of curcumin in high fat diet fed rats. Role of TNF-α and free fatty acids. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2011, 49, 1129–1140. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, S.S.; Ruan, D.; Zhu, Y.W.; et al. Protective effect of curcumin on ochratoxin A-induced liver oxidative injury in duck is mediated by modulating lipid metabolism and the intestinal microbiota. Poultry Sci. 2020, 99, 1124–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, E. M.; Choi, M. S.; Jung, U. J.; et al. Beneficial effects of curcumin on hyperlipidemia and insulin resistance in high-fat-fed hamsters. Metab 2008, 57, 1576–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slika, L.; Patra, D. A short review on chemical properties, stability and nano-technological advances for curcumin delivery. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2020, 17, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand, P.; Kunnumakkara, A. B.; Newman, R. A.; et al. Bioavailability of curcumin: Problems and promises. Mol. Pharm. 2007, 4, 807–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Rao, Z.; et al. Study on the stability and oral bioavailability of curcumin loaded (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate/poly (N-vinylpyrrolidone) nanoparticles based on hydrogen bonding-driven self-assembly. Food Chem. 2022, 378, 132091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Xia, N.; Wang, F.; et al. Preparation and characterization of curcumin/β-cyclodextrin nanoparticles by nanoprecipitation to improve the stability and bioavailability of curcumin. LWT 2022, 171, 114149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, G.T.; Licollari, A.; Tan, A.; et al. Pharmacokinetics of liposomal curcumin (Lipocurc™) infusion: Effect of co-medication in cancer patients and comparison with healthy individuals. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2019, 83, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Huang, Y.H.; Wang, B.H.; et al. Research progress on metabolic pathways and metabolites of curcumin compounds in vivo. Mod Med Clin 2015, 12, 1553–1557. [Google Scholar]

- Ireson, C.; Orr, S.; Jones, D. J.; et al. Characterization of metabolites of the chemopreventive agent curcumin in human and rat hepatocytes and in the rat in vivo, and evaluation of their ability to inhibit phorbol ester-induced prostaglandin E2 production. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 1058–1064. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hewlings, S. J.; Kalman, D. S. Curcumin: A review of its’ effects on human health. Foods 2017, 6, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, C.H.; Cheng, A.L. Clinical studies with curcumin. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007, 595, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cruz, N.G.; Sousa, L.P.; Sousa, M.O.; et al. The linkage between inflammation and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pr. 2013, 99, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halim, M.; Halim, A. The effects of inflammation, aging and oxidative stress on the pathogenesis of diabetes mellitus (type 2 diabetes). Diabetes Metab. Synd. 2019, 13, 1165–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, I.; Masoodi, S.R.; Mir, S.A.; et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus: from a metabolic disorder to an inflammatory condition. World J. Diabetes. 2015, 6, 598–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, B.K. Anti-inflammatory effects of exercise: role in diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 2017, 47, 600–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, S.K.; Rains, J.; Croad, J.; et al. Curcumin supplementation lowers TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, and MCP-1 secretion in high glucose-treated cultured monocytes and blood levels of TNF-α, IL-6, MCP-1, glucose, and glycosylated hemoglobin in diabetic Rats. Antioxidant. Redox Sign. 2009, 11, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abo-Salem, O.M.; Harisa, G.I.; Ali, T.M.; et al. Curcumin ameliorates streptozotocin-induced heart injury in rats. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxic. 2014, 28, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzales, A.M.; Orlando, R.A. Curcumin and resveratrol inhibit nuclear factor-kappaB-mediated cytokine expression in adipocytes. Nutr. Metab. 2008, 5, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Meng, X.W.; Yang, X. S.; et al. Curcumin administration suppresses collagen synthesis in the hearts of rats with experimental diabetes. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2018, 39, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, C.F.; Chen, H.B.; Li, Y.L.; et al. Curcumin and its analog alleviate diabetes-induced damages by regulating inflammation and oxidative stress in brain of diabetic rats. Diabetol. Metab.Syndr. 2021, 13, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Panahi, Y.; Khalili, N.; Sahebi, E.; et al. Curcuminoids plus piperine modulate adipokines in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Curr. Clin. Pharm. 2017, 12, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adibian, M.; Hodaei, H.; Nikpayam, O.; et al. The effects of curcumin supplementation on high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, serum adiponectin, and lipid profile in patients with type 2 diabetes: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Phytother. Res. 2019, 33, 1374–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.J.; et al. Inhibition of JNK phosphorylation by a novel curcumin analog prevents high glucose-induced inflammation and apoptosis in cardiomyocytes and the development of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Diabetes 2014, 63, 3497–3511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.L.; Goldfine, I.D.; Maddux, B. A.; et al. Oxidative stress and stress-activated signaling pathways: A unifying hypothesis of type 2 diabetes. Endocr. Rev. 2002, 23, 599–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, C.J.; Damm, P.; Prentki, M. Type 2 diabetes across generations: from pathophysiology to prevention and management. Lancet 2011, 378, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownlee, M. Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications. Nature 2001, 414, 813–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochette, L.; Zeller, M.; Cottin, Y.; et al. Diabetes, oxidative stress and therapeutic strategies. BBA-Gen. Subjects 2014, 1840, 2709–2729. [Google Scholar]

- Tangvarasittichai, S. Oxidative stress, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia and type 2 diabetes mellitus. World J. Diabetes 2015, 6, 456–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drews, G.; Krippeit-Drews, P.; Düfer, M. Oxidative stress and beta-cell dysfunction. Pflug. Arch. Eur. J. Phy. 2010, 460, 703–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Z. H.; Jiang, X.; Li, K.; et al. Curcumin inhibits alloxan-induced pancreatic islet cell damage via antioxidation and antiapoptosis. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxic. 2020, 34, e22499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Huang, L. F.; Gong, J. J.; et al. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of 4 weeks or longer suggest that curcumin may afford some protection against oxidative stress. Nutr. Res. 2018, 60, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafabakhsh, R.; Mobini, M.; Raygan, F.; et al. Curcumin administration and the effects on psychological status and markers of inflammation and oxidative damage in patients with type 2 diabetes and coronary heart disease. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2020, 40, 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Soto-Urquieta, M. G.; López-Briones, S.; Pérez-Vázquez, V.; et al. Curcumin restores mitochondrial functions and decreases lipid peroxidation in liver and kidneys of diabetic db/db mice. Biol. Res. 2014, 47, 74. [Google Scholar]

- Panahi, Y.; Khalili, N.; Sahebi, E.; et al. Antioxidant effects of curcuminoids in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. Inflammopharmacology. 2016, 25, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, T.; Costa, M.; Figueiredo I., D.; et al. Curcumin, alone or in combination with aminoguanidine, increases antioxidant defenses and glycation product detoxification in streptozotocin-diabetic rats: A therapeutic strategy to mitigate glycoxidative stress. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 1036360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wende, A. R.; Symons, J. D.; Abel, E. D. Mechanisms of lipotoxicity in the cardiovascular system. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2012, 14, 517–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lytrivi, M.; Castell, A. L.; Poitout, V.; et al. Recent insights into mechanisms of β-cell lipo- and glucolipotoxicity in type 2 diabetes. J. Mol. Biol. 2020, 432, 1514–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilas-Boas, E.A.; Almeida, D.C.; Roma, L.P.; et al. Lipotoxicity and β-Cell failure in type 2 diabetes: oxidative stress linked to NADPH oxidase and ER stress. Cells 2021, 10, 3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, D.; Shaw, R. J. AMPK: mechanisms of cellular energy sensing and restoration of metabolic balance. Mol. Cell. 2017, 66, 789–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, K.I.; Choi, M.S.; Jung, U.J.; et al. Effect of curcumin supplementation on blood glucose, plasma insulin, and glucose homeostasis related enzyme activities in diabetic db/db mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2008, 52, 995–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, L.Q.; Wang, Y.D.; Chi, H.Y. Effect of curcumin on glucose and lipid metabolism, FFAs and TNF-α in serum of type 2 diabetes mellitus rat models. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2017, 24, 1776–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhan, S.; Yıldırım, S.; Huyut, Z.; et al. Effects of curcumin on sperm quality, lipid profile, antioxidant activity and histopathological changes in streptozotocin-induced diabetes in rats. Andrologia 2020, 52, e13584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.H.; Lee, E.S.; Choi, R.; et al. Protective effects of curcumin on renal oxidative stress and lipid metabolism in a rat model of type 2 diabetic nephropathy. Yonsei Med. J. 2016, 57, 664–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamsi-Goushki, A.; Mortazavi, Z.; Mirshekar, M.A.; et al. Comparative effects of curcumin versus nano-curcumin on insulin resistance, serum levels of apelin and lipid profile in type 2 diabetic rats. Diabet. Metab. Synd. Ob. 2020, 13, 2337–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devadasu, V.R.; Wadsworth, R.M.; Kumar, M.N.V.R. Protective effects of nanoparticulate coenzyme Q10 and curcumin on inflammatory markers and lipid metabolism in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats: a possible remedy to diabetic complications. Drug Deliv. Transl. Re. 2011, 1, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karandish, M.; Mozaffari-Khosravi, H.; Mohammadi, S.M.; et al. Curcumin and zinc co-supplementation along with a loss-weight diet can improve lipid profiles in subjects with prediabetes: a multi-arm, parallel-group, randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled phase 2 clinical trial. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2022, 14, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panahi, Y.; Khalili, N.; Sahebi, E.; et al. Curcuminoids modify lipid profile in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 2017, 33, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L. L.; Li, J. M.; Song, B. L.; et al. Curcumin rescues high fat diet-induced obesity and insulin sensitivity in mice through regulating SREBP pathway. Toxicol. Appl. Pharm. 2016, 304, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bensellam, M.; Laybutt, D. R.; Jonas, J. C. The molecular mechanisms of pancreatic beta-cell glucotoxicity: recent findings and future research directions. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2012, 364, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Liu, G.; Guo, J.; et al. The pi3k/akt pathway in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 14, 1483–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thota, R. N.; Rosato, J. I.; Dias, C. B.; et al. Dietary supplementation with curcumin reduce circulating levels of glycogen synthase kinase-3β and islet amyloid polypeptide in adults with high risk of type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahimi, H. R.; Mohammadpour, A. H.; Dastani, M.; et al. The effect of nano-curcumin on HbA1c, fasting blood glucose, and lipid profile in diabetic subjects: a randomized clinical trial. Avicenna J. Phytomedi. 2016, 6, 567–577. [Google Scholar]

- Algul, S.; Ozcelik, O.; Oto, G.; et al. Effects of curcumin administration on Nesfatin-1 levels in blood, brain and fat tissues of diabetic rats. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmaco. 2021, 25, 1616–1621. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, G.R.; Hsieh, W.T.; Chou, L.S.; et al. Curcumin improved glucose intolerance, renal injury, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and decreased chromium loss through urine in obese mice. Processes. 2021, 9, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayeli, V.K.; Shenoy, A.K. Antidiabetic effect of bioenhanced preparation of turmeric in streptozotocin–nicotinamide induced type 2 diabetic Wistar rats. J. Ayurveda Integr. Me. 2021, 12, 474–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saud, N.B.S. Impact of curcumin treatment on diabetic albino rats. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 27, 689–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, K.; Sil, P.C. Curcumin enhances recovery of pancreatic islets from cellular stress induced inflammation and apoptosis in diabetic rats. Toxicol. Appl. Pharm. 2015, 282, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Flores, L.M.; López-Briones, S.; Macías-Cervantes, M.H.; et al. A PPARγ, NF-κB and AMPK-dependent mechanism may be involved in the beneficial effects of curcumin in the diabetic db/db mice liver. Molecules 2014, 19, 8289–8302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuengsamarn, S.; Rattanamongkolgul, S.; Luechapudiporn, R.; et al. Curcumin extract for prevention of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012, 35, 2121–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pivari, F.; Mingione, A.; Brasacchio, C.; et al. Curcumin and type 2 diabetes mellitus: Prevention and treatment. Nutrients. 2019, 11, 1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, S.K.; Rezagholizadeh, M. Effect of eight-week curcumin supplementation with endurance training on glycemic indexes in middle age women with type 2 diabetes in Iran, a preliminary study. Diabetes Metab. Synd. 2021, 15, 963–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badr, M.; Sharkawy, H.; Farid, A. A.; et al. Curcumin induces regeneration of β cells and suppression of phosphorylated-NF-κB in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. J. Basic Appl. Zool. 2020, 81, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Wang, H.; Zhang, P.; et al. Modulation of gut microbiota contributes to curcumin-mediated attenuation of hepatic steatosis in rats. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2017, 1861, 1801–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kootte, R.S.; Vrieze, A.; Holleman, F.; et al. The therapeutic potential of manipulating gut microbiota in obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2012, 14, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.H.; Kim, B.S.; Han, K.; et al. Ephedra-treated donor-derived gut microbiota transplantation ameliorates high fat diet-induced obesity in rats. Int. J. Env. Res. Pub. He. 2017, 14, E555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T.; Yin, Z.; Yan, Z.; et al. Tetrahydrocurcumin ameliorates diabetes profiles of db/db mice by altering the composition of gut microbiota and up-regulating the expression of GLP-1 in the pancreas. Fitoterapia 2020, 146, 104665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Sowers, J.R. Application of a novel curcumin analog in the management of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Diabetes Metab. Res. 2014, 63, 3166–3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, S.; Sun, W.; et al. Inhibition of JNK by novel curcumin analog C66 prevents diabetic cardiomyopathy with a preservation of cardiac metallothionein expression. Am. J. Physiol.-Endoc. M. 2014, 306, E1239–E1247. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, W.; Zha, W.L.; Ke, Z.Q.; et al. Curcumin protects neonatal rat cardiomyocytes against high glucose-induced apoptosis via PI3K/Akt signalling pathway. J. Diabetes Res. 2016, 2016, 4158591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chougala, M.B.; Bhaskar, J.J.; Rajan, M.; et al. Effect of curcumin and quercetin on lysosomal enzyme activities in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 31, 749–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.Y.; Meng, X.; Li, S.; et al. Bioactivity, health benefits, and related molecular mechanisms of curcumin: Current progress, challenges, and perspectives. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand, P.; Kunnumakkara, A.B.; Newman, R.A.; et al. Bioavailability of curcumin: Problems and promises. Mol. Pharmaceutics. 2007, 4, 807–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoshyar, N.; Gray, S.; Han, H.; et al. The effect of nanoparticle size on in vivo pharmacokinetics and cellular interaction. Nanomedicine 2016, 11, 673–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben, X.Y.; Wang, Y.R.; Zheng, H.H.; et al. Construction of exosomes that overexpress CD47 and evaluation of their immune escape. Front. Bioeng. Biotech. 2022, 10, 936–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalluri, R.; LeBleu, V.S. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science. 2020, 367, 6977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhang, C.; Gao, Z.; et al. Curcumin-loaded macrophage-derived exosomes effectively improve wound healing. Mol Pharm. 2023, 20, 4453–4467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).