Submitted:

26 April 2024

Posted:

28 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

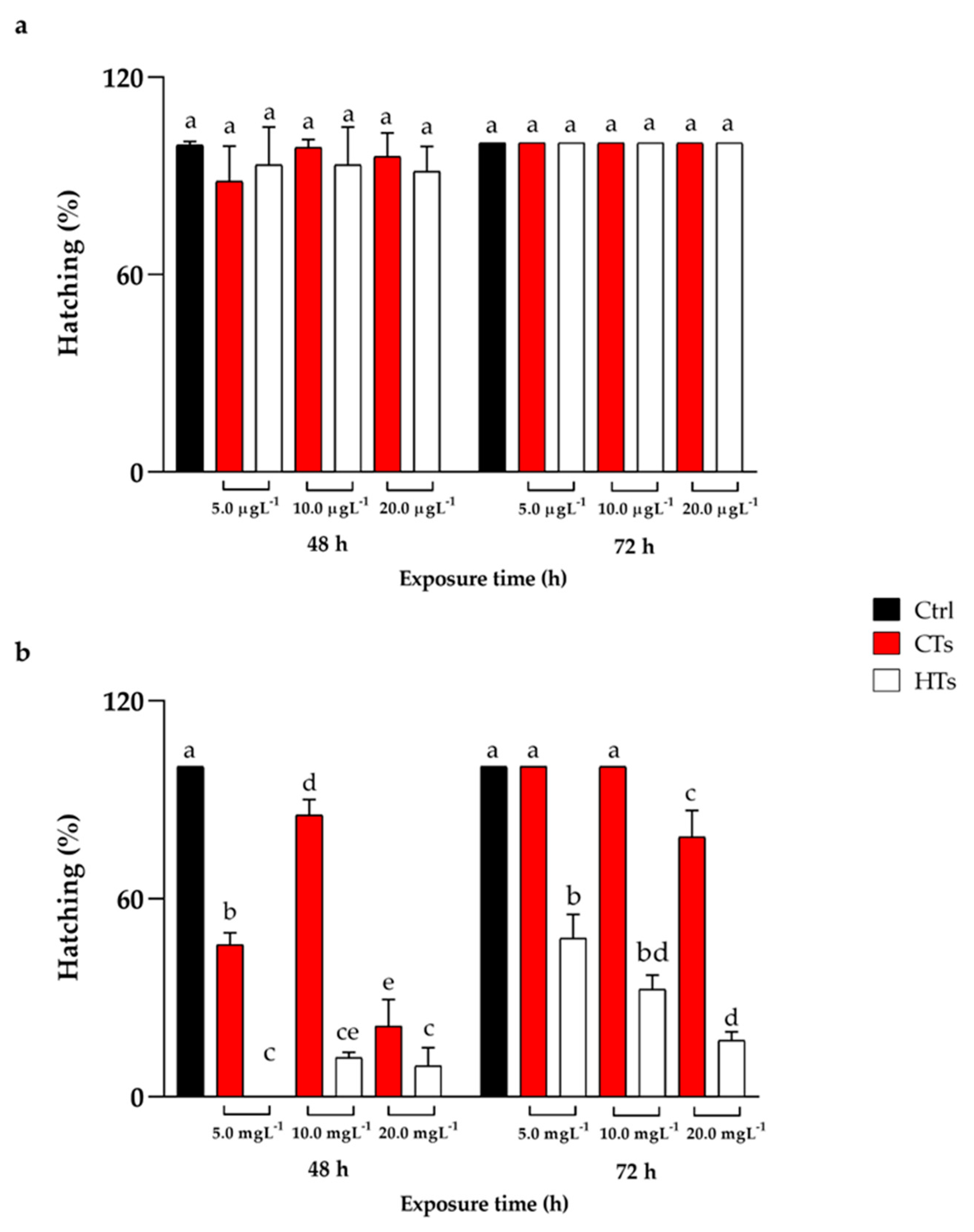

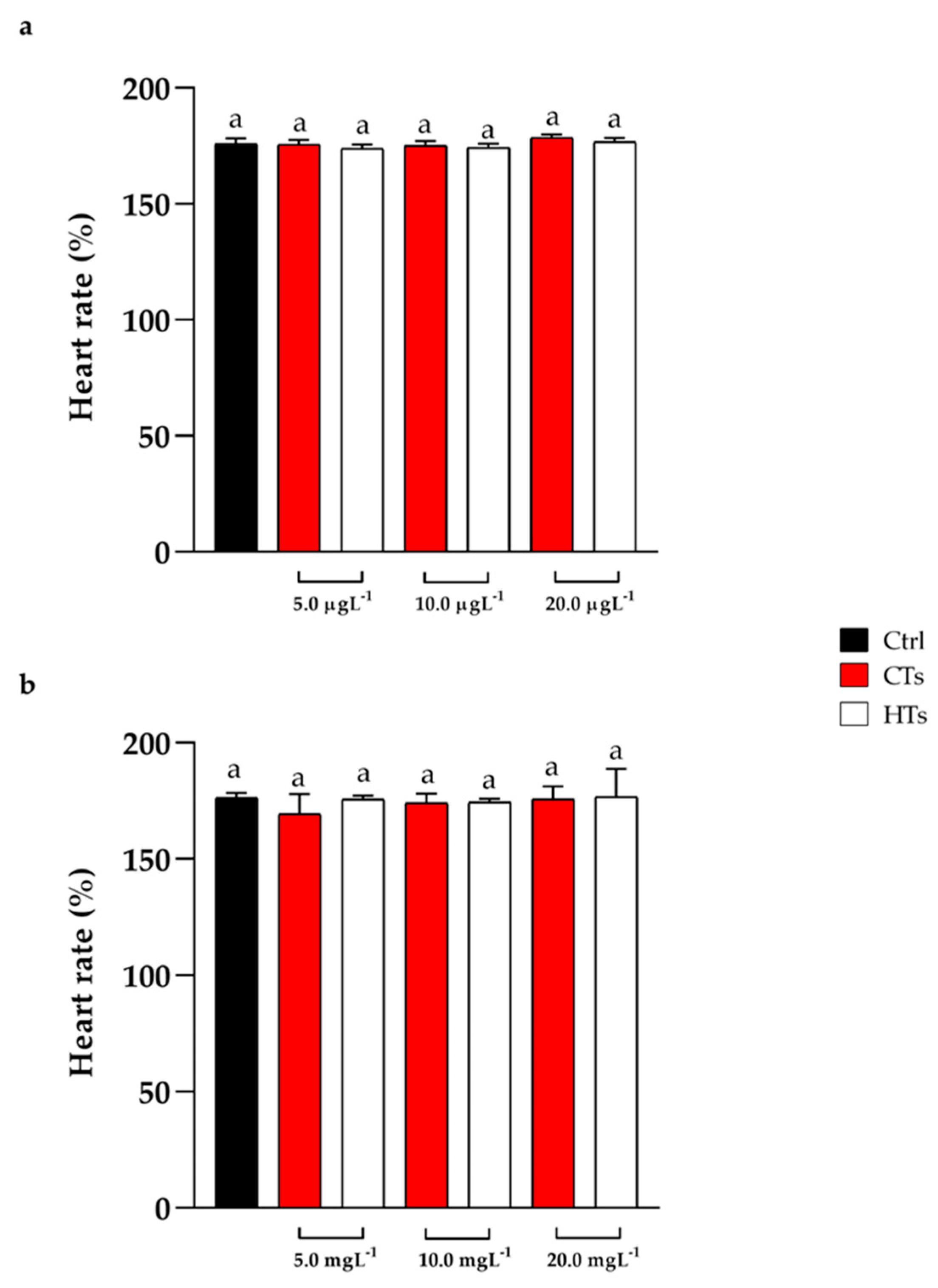

2.1. Survival, Hatching and Heart Rate

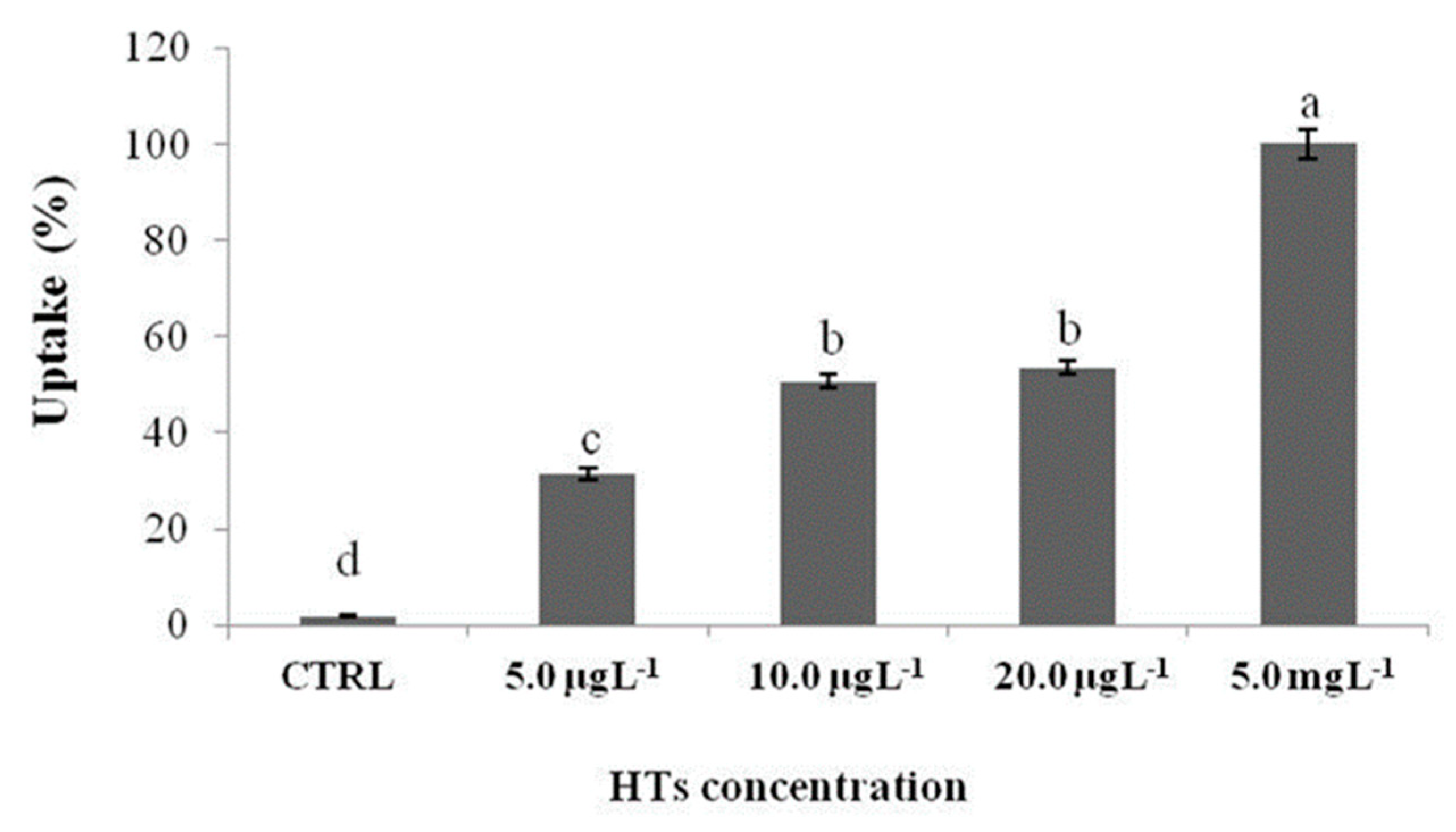

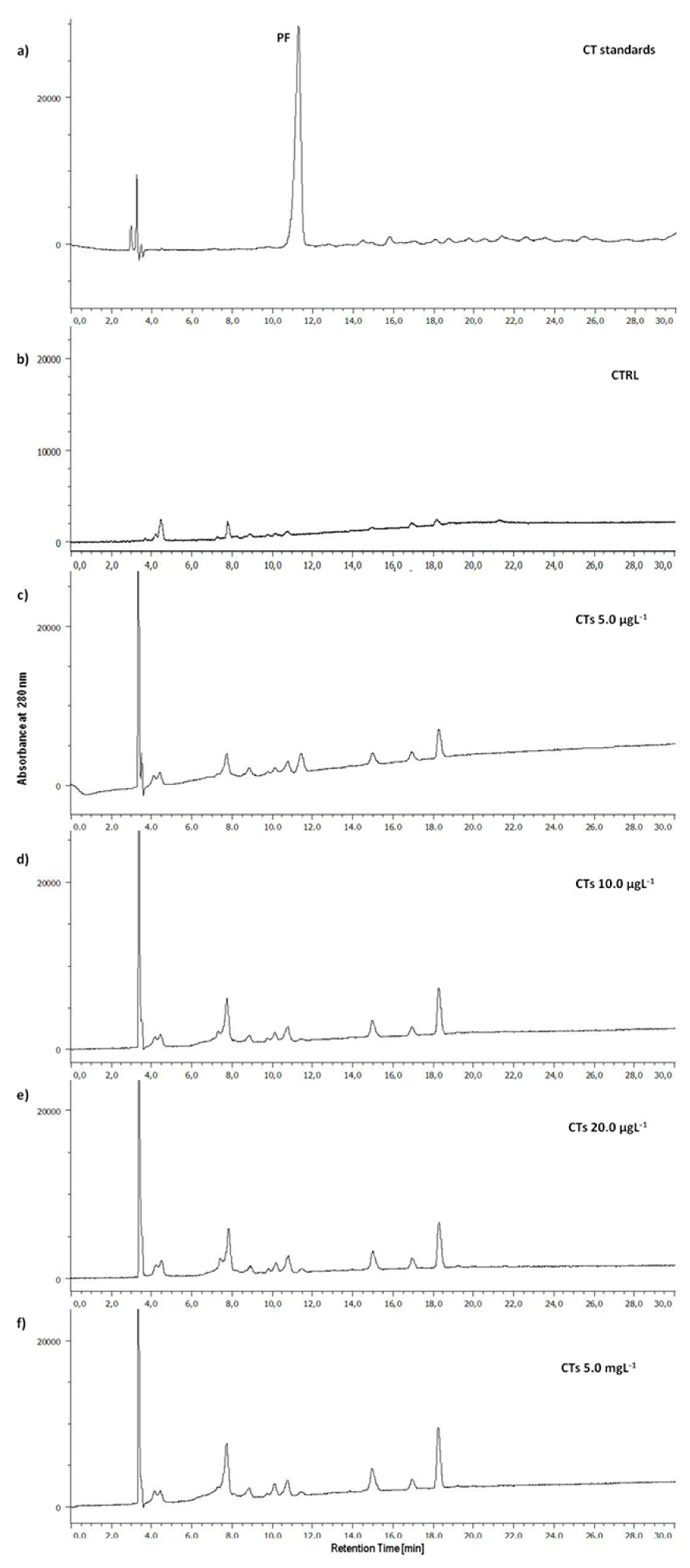

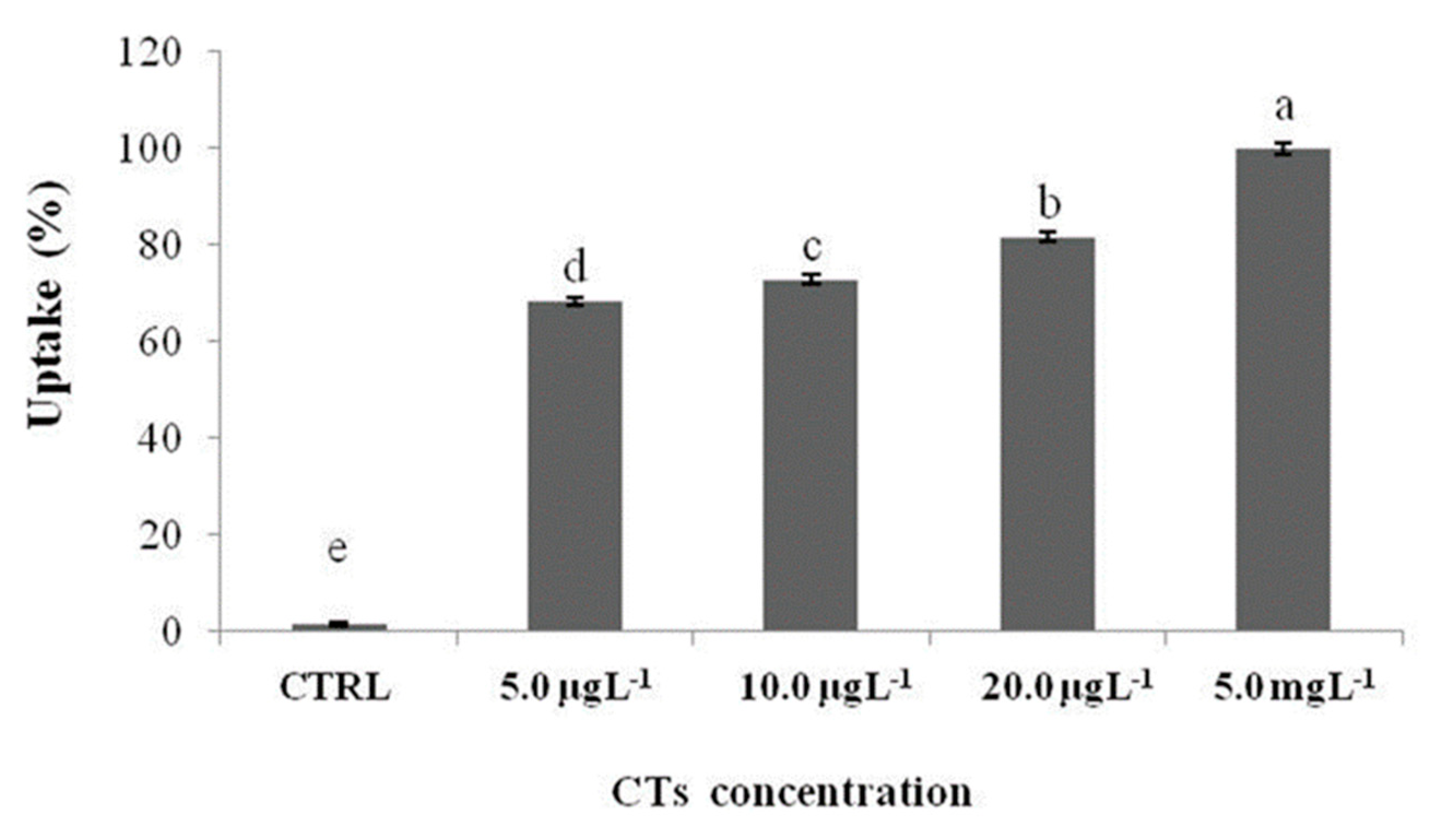

2.2. Uptake of HTs and CTs

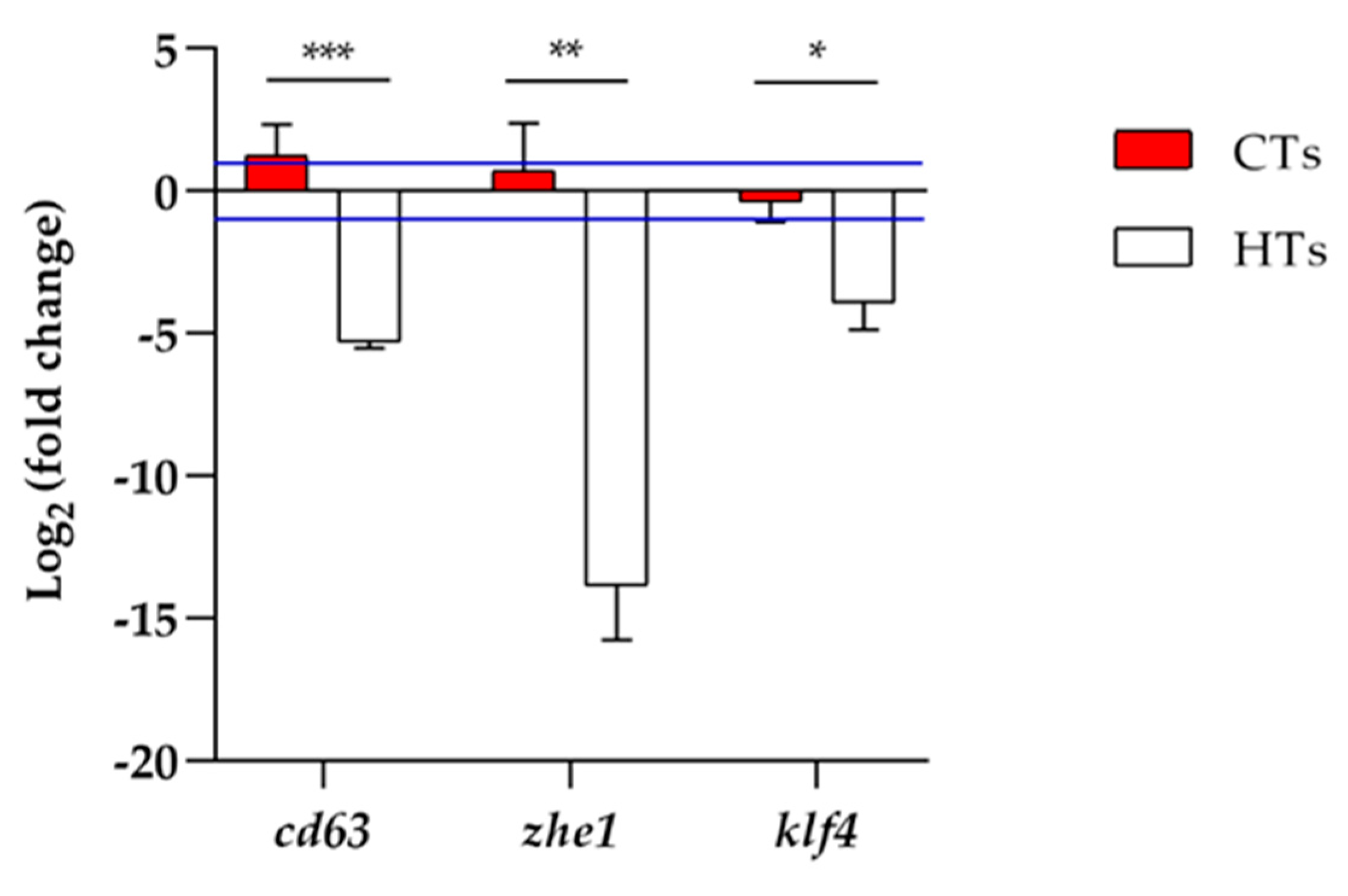

2.3. Analysis of Gene Expression

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Preparation of Solutions

4.2. Zebrafish Breeding

4.3. Embryos Treatment

4.4. Analysis of Development

4.5. Extraction of Tannins from Zebrafish Larvae

4.6. HPLC Analysis

4.7. Quantitative Real-Time PCR

4.8. Statistical Analyses

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Otegui, M.S. Imaging polyphenolic compounds in plant tissues. Recent advances in polyphenol research 2021, 7, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Rahaman, M.S.; Islam, M.R.; Rahman, F.; Mithi, F.M.; Alqahtani, T.; Almikhlafi, M.A.; Alghamdi, S.Q.; Alruwaili, A.S.; Hossain, M.S.; et al. Role of phenolic compounds in human disease: Current knowledge and future prospects. Molecules 2021, 27, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aatif, M. Current Understanding of Polyphenols to Enhance Bioavailability for Better Therapies. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orso, G.; Solovyev, M.M.; Facchiano, S.; Tyrikova, E.; Sateriale, D.; Kashinskaya, E.; Pagliarulo, C.; Hoseinifar, H.S.; Simonov, E.; Varricchio, E.; et al. Chestnut shell tannins: Effects on intestinal inflammation and dysbiosis in Zebrafish. Animals 2021, 11, 1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imperatore, R.; Fronte, B.; Scicchitano, D.; Orso, G.; Marchese, M.; Mero, S.; Licitra, R.; Coccia, E.; Candela, M.; Paolucci, M. Dietary Supplementation with a Blend of Hydrolyzable and Condensed Tannins Ameliorates Diet-Induced Intestinal Inflammation in Zebrafish (Danio rerio). Animals. 2021, 13, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imperatore, R.; Orso, G.; Facchiano, S.; Scarano, P.P.; Hoseinifar, S.H.; Ashouri, G.; Guarino, C.; Paolucci, M. Anti-inflammatory and immunostimulant effect of different timing-related administration of dietary polyphenols on intestinal inflammation in zebrafish, Danio rerio. Aquac. 2023, 563, 738878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Kiloni, S.M.; Cáceres-Vélez, P.R.; Jusuf, P.R.; Cottrell, J.J.; Dunshea, F.R. Phytochemicals, Antioxidant Activities, and Toxicological Screening of Native Australian Fruits Using Zebrafish Embryonic Model. Foods 2022, 11, 4038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, A.K.; Islam, M.N.; Faruk, M.O.; Ashaduzzaman, M.; Dungani, R. Review on tannins: Extraction processes, applications and possibilities. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2020, 135, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, M.; Jain, S. Tannins: An antinutrient with positive effect to manage diabetes. Res. J. Recent Sci. 2012, 2277, 2502. [Google Scholar]

- He, M.; Tian, H.; Luo, X.; Qi, X.; Chen, X. Molecular progress in research on fruit astringency. Molecules 2015, 20, 1434–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, M.; Mondal, B.; Lata, M. Scope of utilization of tannin & saponin to improve animal performance. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 2021, 9, 2168–2179. [Google Scholar]

- De Francesco, G.; Bravi, E.; Sanarica, E.; Marconi, O.; Cappelletti, F.; Perretti, G. Effect of addition of different phenolic-rich extracts on beer flavour stability. Foods 2020, 9, 1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raitanen, J.E.; Järvenpää, E.; Korpinen, R.; Mäkinen, S.; Hellström, J.; Kilpeläinen, P.; Liimatainen, J.; Ora, A.; Tupasela, T.; Jyske, T. Tannins of conifer bark as nordic piquancy—Sustainable preservative and aroma? Molecules 2020, 25, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Melo, L.F.M.; de Queiroz Aquino-Martins, V.G.; da Silva, A.P.; Rocha, H.A.O.; Scortecci, K.C. Biological and pharmacological aspects of tannins and potential biotechnological applications. Food Chem. 2023, 414, 135645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Guan, Q.; Jiang, J.; Khan, M.S. Tannin complexation with metal ions and its implication on human health, environment and industry: An overview. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 127485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haslam, E. Practical Polyphenolics: From Structure to Molecular Recognition and Physiological Function; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, K.; Kumar, V.; Kaur, J.; Tanwar, B.; Goyal, A.; Sharma, R.; Gat, Y.; Kumar, A. Health effects, sources, utilization and safety of tannins: A critical review. Toxin Rev. 2021, 40, 432–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzi, A. Tannins medical/pharmacological and related applications: A critical review. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2021, 22, 100481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Sun, J.T.; Cui, H.D.; Jiang, C.Q.; Zhang, Y.T.; Lee, S.; Liu, Z.H.; Jin, J.X. Tannin Supplementation Improves Oocyte Cytoplasmic Maturation and Subsequent Embryo Development in Pigs. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoriello, C.; Zon, L.I. Hooked! Modeling human disease in zebrafish. J. Clin. Invest. 2012, 122, 2337–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horzmann, K.A.; Freeman, J.L. Making Waves: New Developments in Toxicology with the Zebrafish. Toxicol. Sci. 2018, 163, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tal, T.; Yaghoobi, B.; Lein, P.J. Translational toxicology in zebrafish. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2020, 23, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capriello, T.; Di Meglio, G.; De Maio, A.; Scudiero, R.; Bianchi, A.R.; Trifuoggi, M.; Toscanesi, M.; Giarra, A.; Ferrandino, I. Aluminium exposure leads to neurodegeneration and alters the expression of marker genes involved to parkinsonism in zebrafish brain. Chemosphere 2022, 307, 135752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truong, L.; Harper, S.L.; Tanguay, R.L. Evaluation of embryotoxicity using the zebrafish model. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011, 691, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, K.; Clark, M.D.; Torroja, C.F.; Torrance, J.; Berthelot, C.; Muffato, M.; Collins, J.E.; Humphray, S.; McLaren, K.; Matthews, L. The zebrafish reference genome sequence and its relationship to the human genome. Nature 2013, 496, 498–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mektrirat, R.; Yano, T.; Okonogi, S.; Katip, W.; Pikulkaew, S. Phytochemical and safety evaluations of volatile terpenoids from Zingiber cassumunar Roxb. on mature carp peripheral blood mononuclear cells and embryonic zebrafish. Molecules 2020, 25, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, G.R.; Noyes, P.D.; Tanguay, R.L. Advancements in zebrafish applications for 21st century toxicology. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 161, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baran, A.; Köktürk, M.; Atamanalp, M.; Ceyhun, S.B. Determination of developmental toxicity of zebrafish exposed to propyl gallate dosed lower than ADI (Acceptable Daily Intake). Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2018, 94, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veeren, B.; Ghaddar, B.; Bringart, M.; Khazaal, S.; Gonthier, M.P.; Meilhac, O.; Diotel, N.; Bascands, J.L. Phenolic profile of herbal infusion and polyphenol-rich extract from leaves of the medicinal plant antirhea borbonica: Toxicity assay determination in zebrafish embryos and larvae. Molecules 2020, 25, 4482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annona, G.; Tarallo, A.; Nittoli, V.; Varricchio, E.; Sordino, P.; D’Aniello, S.; Paolucci, M. Short-term exposure to the simple polyphenolic compound gallic acid induces neuronal hyperactivity in zebrafish larvae. Euro. J. Neurosci. 2021, 53, 1367–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raharjeng, A.R.P.; Kusumaningtyas, A.A.; Widatama, D.A.; Zarah, S.; Pratama, S.F.; Dani, H.B. The effects of the plant extract on embryonic development of zebrafish (Danio rerio). Trop. Genet. 2021, 1, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Jezierska, B.; Witeska, M. Metal Toxicity to Fish, 2001. University of Podlasie Publisher, Siedlce, p 318.

- Sorolla, S.; Flores, A.; Canals, T.; Cantero, R.; Font, J.; Ollé, L.; Bacardit, A. Study of the Qualitative and Semi-quantitative Analysis of Grape Seed Extract by HPLC. J. Am. Leather Chem. Assoc. 2018, 113, 88–93. [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Vega, R.; Oomah, B.D.; Hernández-Arriaga, A.M.; Salazar-López, N.J.; Vázquez-Sánchez, K. Tannins. Phenolic Compounds in Food 2018, pp. 211–258.

- Hussain, G.; Huang, J.; Rasul, A.; Anwar, H.; Imran, A.; Maqbool, J.; Razzaq, A.; Aziz, N.; Makhdoom, E.H.; Konuk, M.; et al. Putative roles of plant-derived tannins in neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatry disorders: An updated review. Molecules 2019, 24, 2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smeriglio, A.; Barreca, D.; Bellocco, E.; Trombetta, D. Proanthocyanidins and hydrolysable tannins: Occurrence, dietary intake and pharmacological effects. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 174, 1244–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuda, T.; Kimura, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Hatano, T.; Okuda, H.; Arichi, S. Studies on the activities of tannins and related compounds from medicinal plants and drugs. I. Inhibitory effects on lipid peroxidation in mitochondria and microsomes of liver. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1983, 31, 1625–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuolo, M.M.; Lima, V.S.; Junior, M.R.M. Phenolic compounds: Structure, classification, and antioxidant power. Bioactive compounds 2018, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Hoyos-Martínez, P.L.; Merle, J.; Labidi, J.; Charrier–El Bouhtoury, F. Tannins extraction: A key point for their valorization and cleaner production. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 206, 1138–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wätjen, W.; Michels, G.; Steffan, B.; Niering, P.; Chovolou, Y.; Kampkötter, A.; Tran-Thi, Q.H.; Proksch, P.; Kahl, R. Low concentrations of flavonoids are protective in rat H4IIE cells whereas high concentrations cause DNA damage and apoptosis. J. Nutr. 2005, 135, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żwierełło, W.; Maruszewska, A.; Skórka-Majewicz, M.; Goschorska, M.; Baranowska-Bosiacka, I.; Dec, K.; Styburski, D.; Nowakowska, A.; Gutowska, I. The influence of polyphenols on metabolic disorders caused by compounds released from plastics-Review. Chemosphere 2020, 240, 124901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimmel, C.B.; Ballard, W.W.; Kimmel, S.R.; Ullmann, B.; Schilling, T.F. Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev. dynam. 1995, 203, 253–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, H.F. Recognition of Gallotannins and the Physiological Activities: From Chemical View. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 888892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Guan, H.; Zhao, X.; Xie, Q.; Xie, Z.; Cai, F.; Dang, R.; Li, M.; Wang, C. Dietary gallic acid as an antioxidant: A review of its food industry applications, health benefits, bioavailability, nano-delivery systems, and drug interactions. Int. Food Res. 2024, 114068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, C.; Hou, Y.; Ai, X.; Chen, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Meng, X. Gallic acid: Pharmacological activities and molecular mechanisms involved in inflammation-related diseases. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 133, 110985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamed, M.; Soliman, H.A.; Said, R.E.; Martyniuk, C.J.; Osman, A.G.; Sayed, A.E.D.H. Oxidative stress, antioxidant defense responses, and histopathology: Biomarkers for monitoring exposure to pyrogallol in Clarias gariepinus. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 351, 119845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filgueira, D.; Moldes, D.; Fuentealba, C.; García, D.E. Condensed tannins from pine bark: A novel wood surface modifier assisted by laccase. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 103, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzi, A. Tannins: Major sources, properties and applications. Monomers, polymers and composites from renewable resources 2008, 179-199. [CrossRef]

- Fruet, A.P.B.; Giotto, F.M.; Fonseca, M.A.; Nörnberg, J.L.; de Mello, A.S. Effects of the Incorporation of Tannin Extract from Quebracho Colorado Wood on Color Parameters, Lipid Oxidation, and Sensory Attributes of Beef Patties. Foods 2020, 9, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kundap, U.; Jaiswal, Y.; Sarawade, R.; Williams, L.; Shaikh, M.F. Effect of Pelargonidin isolated from Ficus benghalensis L. on phenotypic changes in zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos. Saudi Pharm. J. 2017, 25, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, T.F.D.; Carneiro, W.F.; Reichel, T.; Fabem, S.L.; Machado, M.R.F.; de Souza, K.K.C.; Resende, L.V.; Murgas, L.D.S. The toxicological effects of Eryngium foetidum extracts on zebrafish embryos and larvae depend on the type of extract, dose, and exposure time. Toxicol. Res. 2022, 11, 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alafiatayo, A.A.; Lai, K.S.; Syahida, A.; Mahmood, M.; Shaharuddin, N.A. Phytochemical evaluation, embryotoxicity, and teratogenic effects of Curcuma longa extract on zebrafish (Danio rerio). J. Evid. Based Complementary Altern. Med. 2019. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.K.; Saber, S.P.; Taite, D.R.; Emadi, S.; Irving, R. The protective layer of zebrafish embryo changes continuously with advancing age of embryo development (AGED). J. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2017, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, H.F.; Hashim, Z.; Soon, W.T.; Ab Rahman, N.S.; Zainudin, A.N.; Majid, F.A.A. Comparative study of herbal plants on the phenolic and flavonoid content, antioxidant activities and toxicity on cells and zebrafish embryo. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2017, 7, 452–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraina, I.A.; Maret, W.; Bury, N.R.; Hogstrand, C. Hatching gland development and hatching in zebrafish embryos: A role for zinc and its transporters Zip10 and Znt1a. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 528, 698–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sano, K.; Inohaya, K.; Kawaguchi, M.; Yoshizaki, N.; Iuchi, I.; Yasumasu, S. Purification and characterization of zebrafish hatching enzyme–an evolutionary aspect of the mechanism of egg envelope digestion. FEBS J. 2008, 275, 5934–5946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amatruda, J.F.; Zon, L.I. Dissecting hematopoiesis and disease using the zebrafish. Dev. Biol. 1999, 216, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardiner, M.R.; Daggett, D.F.; Zon, L.I.; Perkins, A.C. Zebrafish KLF4 is essential for anterior mesendoderm/pre-polster differentiation and hatching. Dev. Dynam. 2005, 234, 992–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trikić, M.Z.; Monk, P.; Roehl, H.; Partridge, L.J. Regulation of zebrafish hatching by tetraspanin cd63. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gritsman, K.; Talbot, W.S.; Schier, A.F. Nodal signaling patterns the organizer. Dev. 2000, 127, 921–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coccia, E.; Siano, F.; Volpe, M.G.; Varricchio, E.; Eroldogan, O.T.; Paolucci, M. Chestnut Shell Extract Modulates Immune Parameters in the Rainbow Trout Oncorhynchus mykiss. Fishes 2019, 4, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, L.G. Antinutritional effects of condensed and hydrolyzable tannins. Basic Life Sci. 1992, 59, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.; Kim, W.K. Dietary Application of Tannins as a Potential Mitigation Strategy for Current Challenges in Poultry Production: A Review. Animals 2020, 10, 2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Earl, J.E.; Semlitsch, R.D. Effects of tannin source and concentration from tree leaves on two species of tadpoles. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2015, 34, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Techer, D.; Milla, S.; Fontaine, P.; Viot, S.; Thomas, M. Acute toxicity and sublethal effects of gallic and pelargonic acids on the zebrafish Danio rerio. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 5020–5029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Luo, S.; Wu, B.; Wang, J. Comparative developmental toxicity and stress protein responses of dimethyl sulfoxide to rare minnow and zebrafish embryos/larvae. Zebrafish 2017, 14, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerfield, M. The zebrafish book: A guide for the laboratory use of zebrafish (Danio Rerio), 2000. http://zfin. org/zf_info/zfbook/zfbk.

- Capriello, T.; Monteiro, S.M.; Félix, L.M.; Donizetti, A.; Aliperti, V.; Ferrandino, I. Apoptosis, oxidative stress and genotoxicity in developing zebrafish after aluminium exposure. Aquat. Toxicol. 2021, 236, 105872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Pietra, A.; Fasciolo, G.; Lucariello, D.; Motta, C.M.; Venditti, P.; Ferrandino, I. Polystyrene microplastics effects on zebrafish embryological development: Comparison of two different sizes. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2024, 106, 104371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tannenbaum, J.; Bennett, B.T. Russell and Burch's 3Rs then and now: The need for clarity in definition and purpose. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 2015, 54, 120–132. [Google Scholar]

- Monaco, A.; Grimaldi, M.C.; Ferrandino, I. Aluminium chloride-induced toxicity in zebrafish larvae. J. Fish Dis. 2017, 40, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Lv, M.; Zhao, X.; Ji, Y.; Han, X.; Wang, X.; Chen, L. The combined toxic effects of polyvinyl chloride microplastics and di (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate on the juvenile zebrafish (Danio rerio). J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 440, 129711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfaffl, M.W. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT–PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001, 29, e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaffl, M.W.; Horgan, G.W.; Dempfle, L. Relative expression software tool (REST©) for group-wise comparison and statistical analysis of relative expression results in real-time PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, e36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babich, R.; Van Beneden, R.J. Effect of arsenic exposure on early eye development in zebrafish (Danio rerio). J. Appl. Toxicol. 2019, 39, 824–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Kim, M.J.; Sellaththurai, S.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.; Lee, J. Generation of cd63-deficient zebrafish to analyze the role of cd63 in viral infection. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2021, 111, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyam, A.; Singh, P.P.; Afonso, L.O.; Schultz, A.G. Exposure to biogenic phosphorus nano-agromaterials promotes early hatching and causes no acute toxicity in zebrafish embryos. Environ. Sci. Nano 2022, 9, 1364–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesterlund, L.; Jiao, H.; Unneberg, P.; Hovatta, O.; Kere, J. The zebrafish transcriptome during early development. BMC Dev. Biol. 2011, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| HTs | PY concentration (ng/larva) | GA concentration (ng/larva) |

|---|---|---|

| CTRL | - | - |

| 5.0 μgL-1 | 40.7 ± 3.1 b | 11.7 ± 1.3 b |

| 10.0 μgL-1 | 38.5 ± 2.9 b | 2.8 ± 0.7 c |

| 20.0 μgL-1 | 43.9 ± 2.3 b | 4.7 ± 0.8 c |

| 5.0 mgL-1 | 594.6 ± 7.3 a | 45.9 ± 1.2 a |

| CTs | PY concentration (ng/larva) | GA concentration (ng/larva) |

|---|---|---|

| CTRL | - | - |

| 5.0 μgL-1 | 386.2 ± 5.2 a | 16.9 ± 0.9 a |

| 10.0μgL-1 | 382.7 ± 4.9 a | 4.3 ± 1.5 b |

| 20.0μgL-1 | 383.3 ± 5.1 a | 7.8 ± 1.8 b |

| 5.0 mgL-1 | 380.3 ± 6.2 a | 8.3 ± 1.6 b |

| Gene | Primers | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-actin | F | CGAGCAGGAGATGGGAACC | [75] |

| R | CAACGGAAACGCTCATTGC | ||

| cd63 | F | GGAAACTCCTCTAGTGATTGGGTG | [76] |

| R | CGGTGGGTTTCGTCATAGCTC | ||

| zhe1 | F | GCCCGGTCTGGAAACCA | [77] |

| R | GTCCGATCTGCACGTTTTCA | ||

| klf4 | F | TTAAGCCCAGAAGACAGCAAG | [78] |

| R | GCATGTGCGCTTTCAAAT | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).