Submitted:

20 August 2025

Posted:

21 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Zebrafish Rearing and Experimental Diets

2.2. Histological and Immunohistochemical Analysis

2.3. Western Blotting

2.4. Proteomics

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

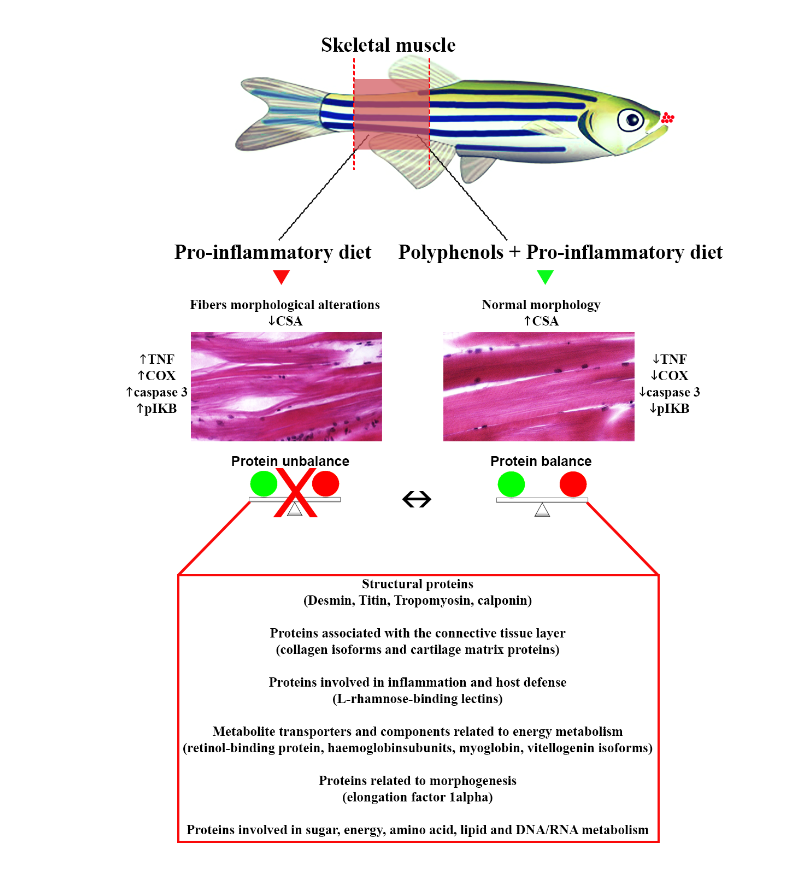

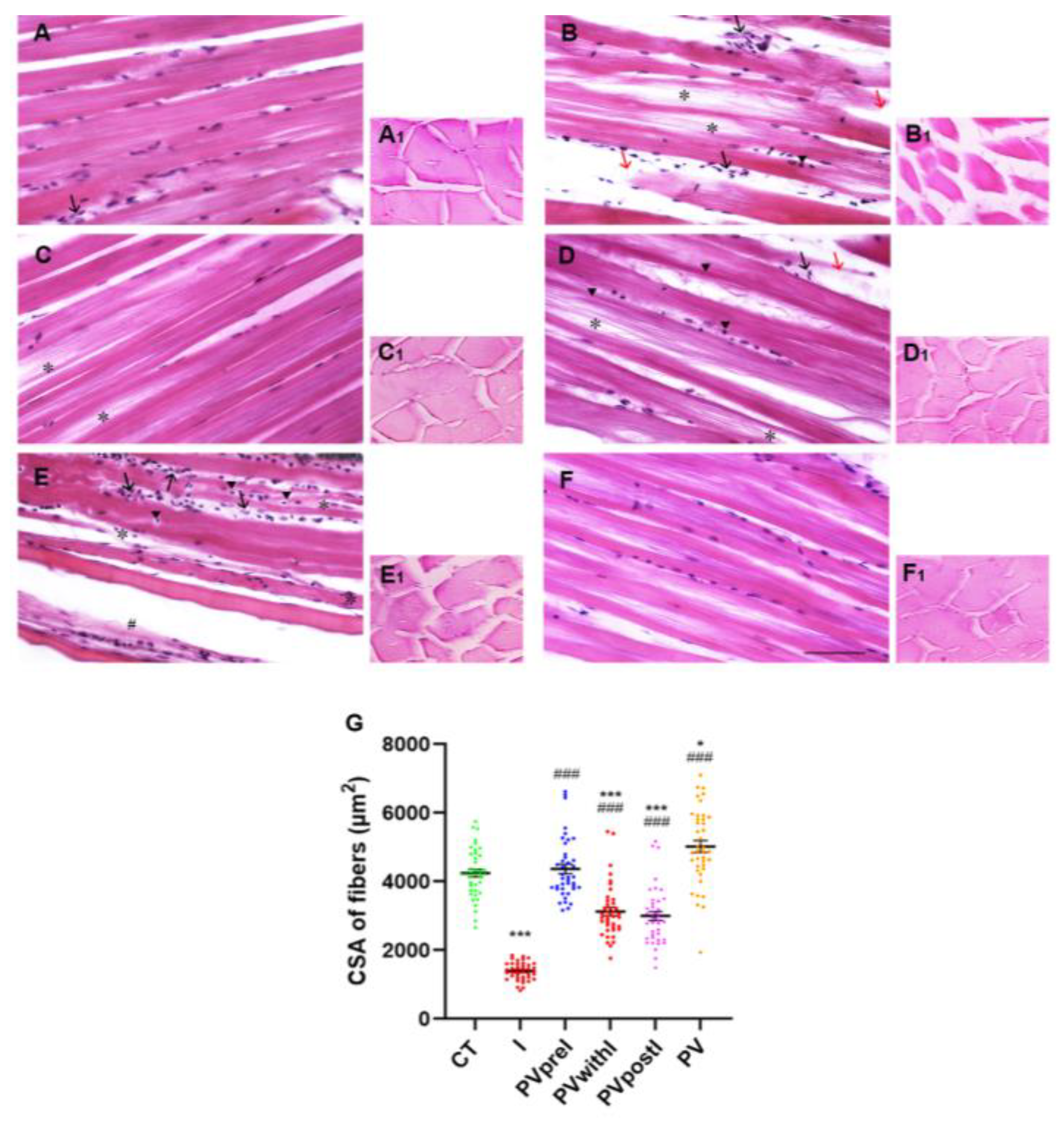

3.1. Polyphenol Effects on the White Muscle Tissue Morphology

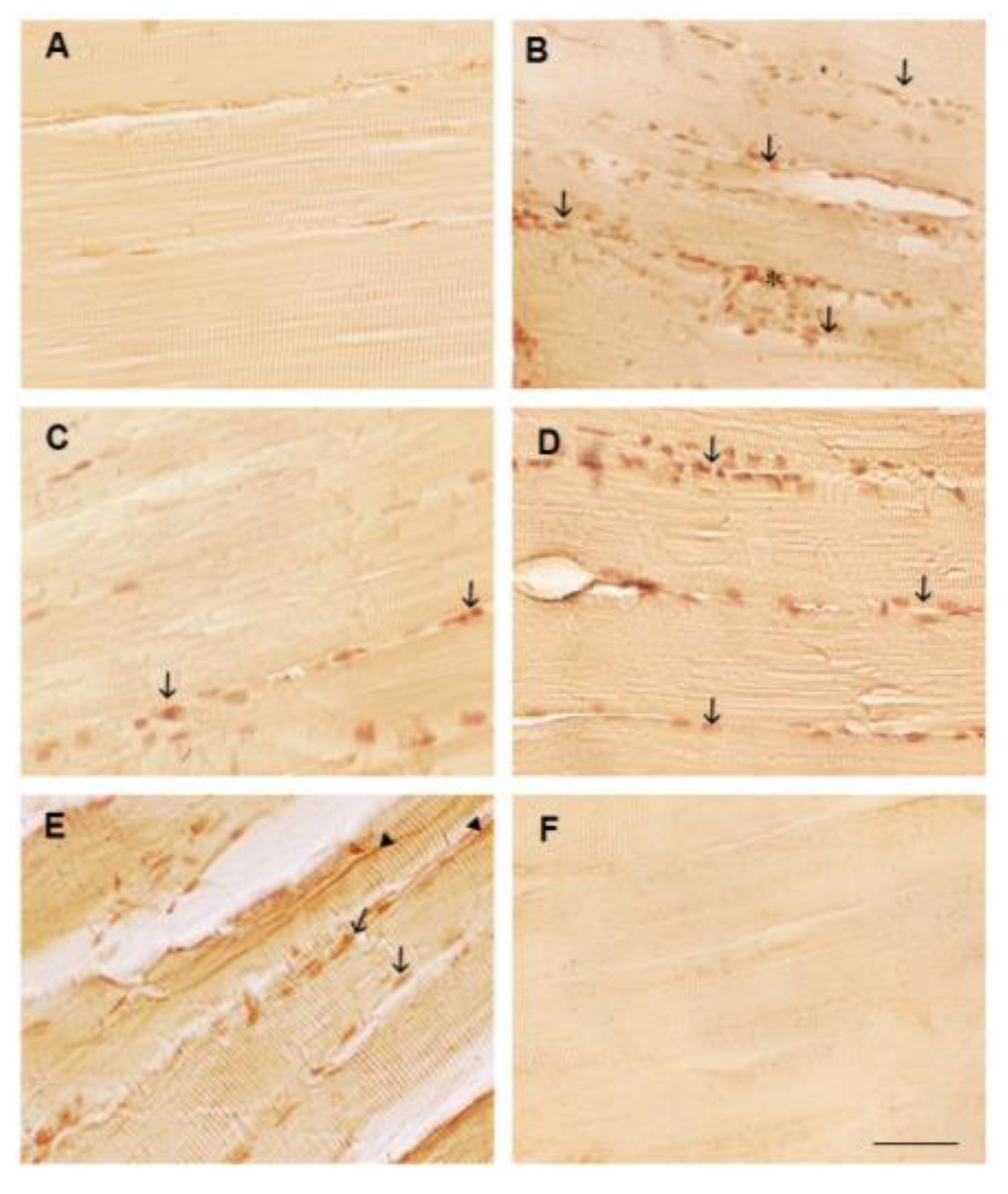

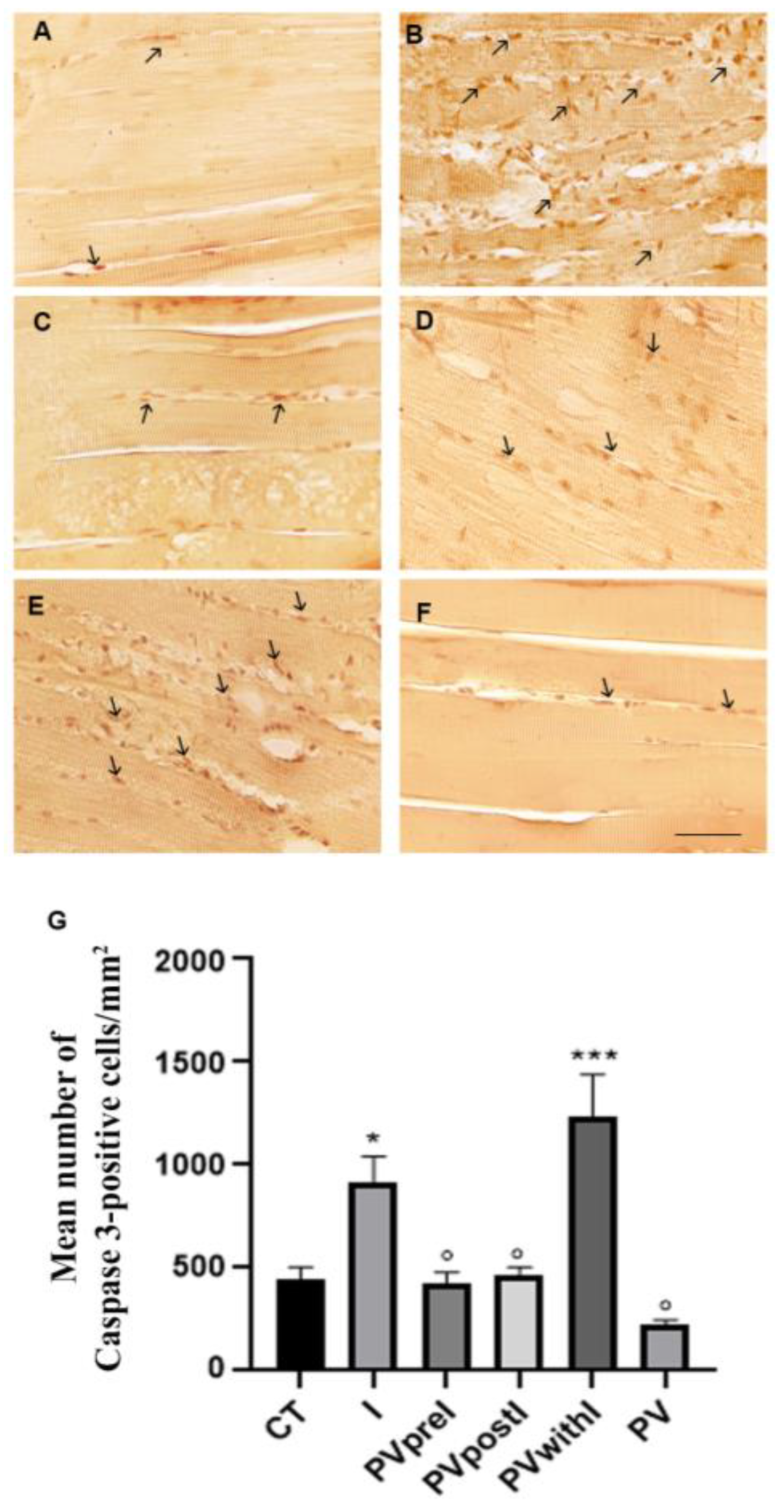

3.2. Polyphenol Effects on TNF-α, COX2 and Caspase 3 Immunoexpression in the White Muscle Tissue

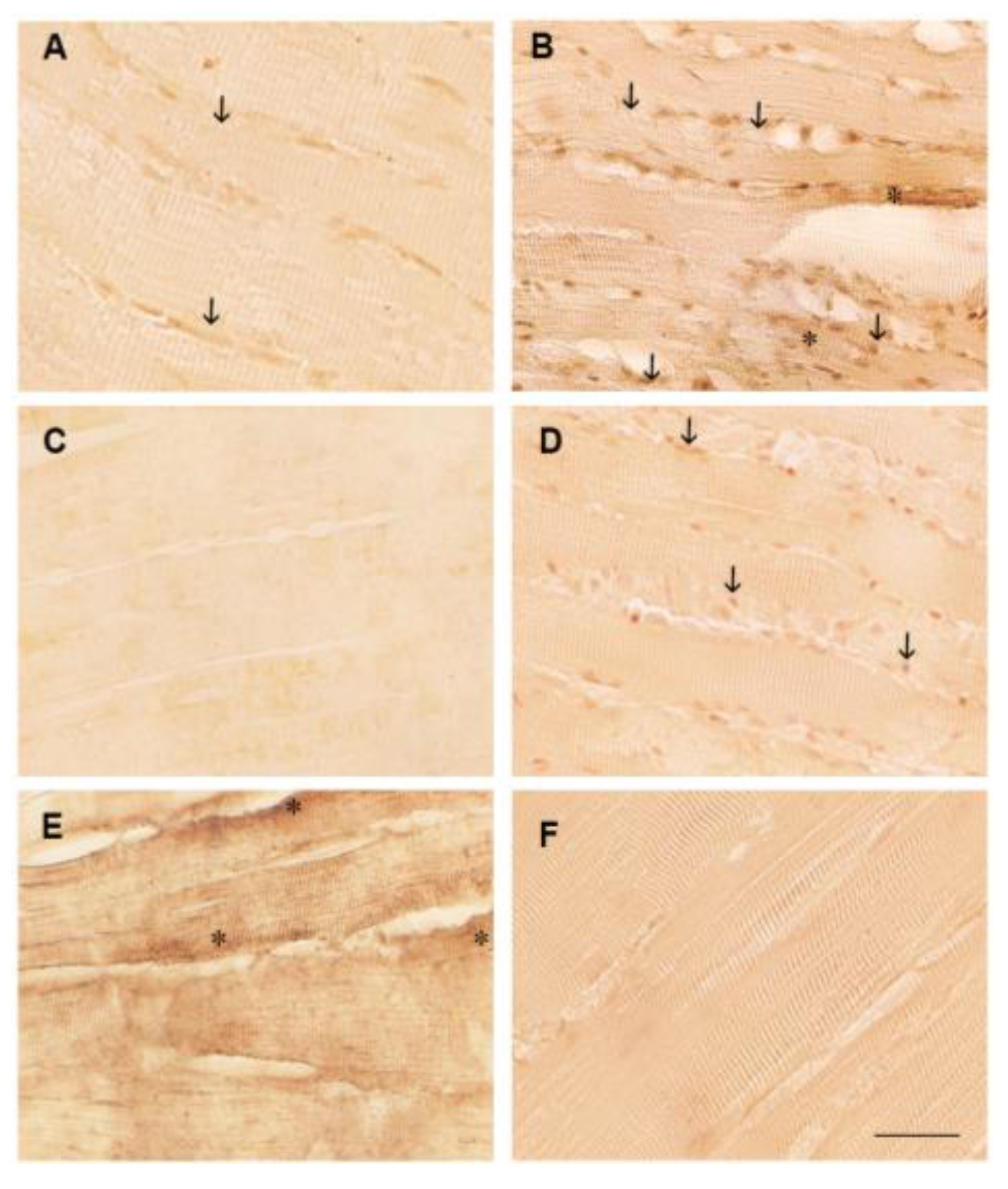

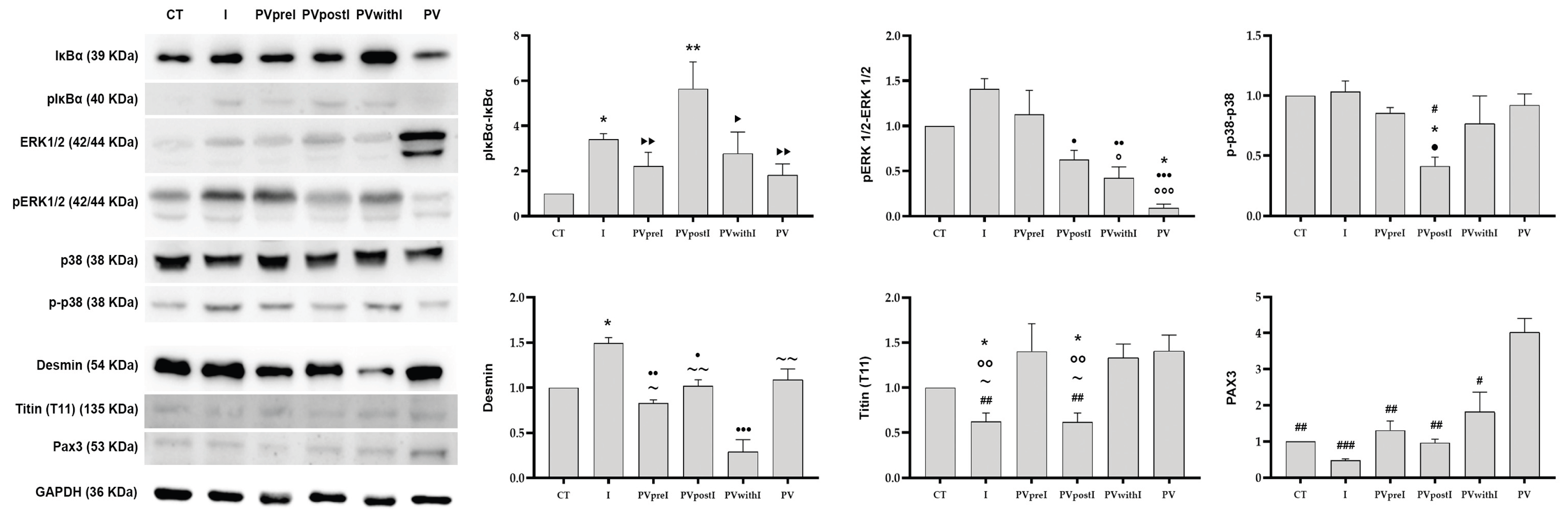

3.3. Polyphenol Effects on NF-κB and p38 MAPK, ERK 1/2 Signaling Pathway in the White Muscle Tissue

3.4. Polyphenol Effects on Desmin, Titin and PAX3 in the White Muscle Tissue

3.5. Polyphenol Effects on the White Muscle Proteomic Repertoire

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ji, Y.; Li, M.; Chang, M.; Liu, R.; Qiu, J.; Wang, K.; Deng, C.; Shen, Y.; Zhu, J.; Wang, W.; Xu, L.; Sun, H. Inflammation: Roles in Skeletal Muscle Atrophy. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022, 11, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Chen, X.; Fan, M. Signaling mechanisms involved in disuse muscle atrophy. Medical hypotheses. 2007, 69, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Li, N.; Jia, W.; Wang, N.; Liang, M.; Yang, X.; Du, G. Skeletal muscle atrophy: From mechanisms to treatments. Pharmacol Research. 2021, 72, 105807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powers, S.K.; Kavazis, A.N.; DeRuisseau, K.C. Mechanisms of disuse muscle atrophy: role of oxidative stress. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 2005, 288, R337–R344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzetti, E.; Leeuwenburgh, C. Skeletal muscle apoptosis, sarcopenia and frailty at old age. Exp Gerontol. 2006, 41, 1234–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaffney, C.J.; Pollard, A.; Barratt, T.F.; Constantin-Teodosiu, D.; Greenhaff, P.L.; Szewczyk, N.J. Greater loss of mitochondrial function with ageing is associated with earlier onset of sarcopenia in C. elegans. Aging. 2018, 10, 3382–3396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartori, R.; Romanello, V.; Sandri, M. Mechanisms of muscle atrophy and hypertrophy: implications in health and disease. Nat Commun. 2021, 12, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochniewicz, E.; Thompson, L.V.; Thomas, D.D. Age-related decline in actomyosin structure and function. Exp Gerontol. 2007, 42, 931–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, I.H.; Chang, J.L.; Hua, K.; Huang, W.C.; Hsu, M.T.; Chen, Y.F. Skeletal muscle in aged mice reveals extensive transformation of muscle gene expression. BMC Genet. 2018, 19, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooley, N.J.; Tacchi, L.; Secombes, C.J.; Martin, S.A.M. Inflammatory responses in primary muscle cell cultures in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). BMC Genomics. 2013, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, M.; Kenney, P.B.; Rexroad, C.E.; Yao, J. Proteomic signature of muscle atrophy in rainbow trout. J Proteomics. 2010, 73, 778–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froehlich, H.E.; Runge, C.A.; Gentry, R.R.; Gaines, S.D.; Halpern, B.S. Comparative terrestrial feed and land use of an aquaculture-dominant world. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115, 5295–5300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Xia, J.; Zhang, X.; He, X.; Li, L.; Tang, R.; Chi, W.; Li, D. Diet affects muscle quality and growth traits of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus): A comparison between grass and artificial feed. Front Physiol. 2018, 9, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Luo, Z.; Chen, F.; Wei, C.; Wu, K.; Zhu, X.; Liu, X. Effect of fish meal replacement by Chlorella meal with dietary cellulase addition on growth performance, digestive enzymatic activities, histology and myogenic genes’ expression for crucian carp Carassius auratus. Aquac Res. 2017, 48, 3244–3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Liang, H.; Ge, X.; Zhu, J.; Wang, Y.; Ren, M.; Chen, X. Dietary chlorella (Chlorella vulgaris) supplementation effectively improves body color, alleviates muscle inflammation and inhibits apoptosis in largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2022, 127, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Médale, F.; Boucher, R.L.; Dupont-Nivet, M.; Quillet, E.; Aubin, J.; Panserat, S. Plant based diets for farmed fish. INRA Prod Anim. 2013, 26, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Zhang, C.; Dai, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, K.; Gao, Z.; Chen, X.; Yang, X.; Sun, H.; Yao, X.; Xu, L.; Liu, H. Nutritional Strategies for Muscle Atrophy: Current Evidence and Underlying Mechanisms. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2024, 68, e2300347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salucci, S.; Falcieri, E. Polyphenols and their potential role in preventing skeletal muscle atrophy. Nutr Res. 2020, 74, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, B.; Li, Y.P. Curcumin prevents lipopolysaccharide-induced atrogin-1/MAFbx upregulation and muscle mass loss. J Cell Biochem. 2007, 100, 960–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirasaka, K.; Saito, S.; Yamaguchi, S.; Miyazaki, R.; Wang, Y.; Haruna, M.; Taniyama, S.; Higashitani, A.; Terao, J.; Nikawa, T.; Tachibana, K. Dietary Supplementation with Isoflavones Prevents Muscle Wasting in Tumor-Bearing Mice. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol. 2016, 62, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabata, S.; Aizawa, M.; Kinoshita, M.; Ito, Y.; Kawamura, Y.; Takebe, M.; Pan, W.; Sakuma, K. The influence of isoflavone for denervation-induced muscle atrophy. Eur J Nutr. 2019, 58, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Huang, Z.; Zhu, J.; Qiu, J.; Ma, W.; Yang, X.; Ding, F.; Sun, H. Isoquercitrin Delays Denervated Soleus Muscle Atrophy by Inhibiting Oxidative Stress and Inflammation. Front Physiol. 2020, 11, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahazi, M.; Hoseinifar, S.H.; Jafari, V.; Hajimoradloo, A.; Doan, H.V.; Paolucci, M. Dietary supplementation of polyphenols positively affects the innate immune response, oxidative status, and growth performance of common carp, Cyprinus carpio L. Aquaculture 2020, 517, 734709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoseinifar, S.H.; Jahazi, M.; Nikdehghan, N.; Doan, H.V.; Volpe, M.G.; Paolucci, M. Effects of dietary polyphenols from agricultural by-products on mucosal and humoral immune and antioxidant responses of convict cichlid (Amatitlania nigrofasciata). Aquaculture. 2020, 517, 734790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safari, R.; Hoseinifar, S.H.; Imanpour, M.R.; Mazandarani, M.; Sanchouli, H.; Paolucci, M. Effects of dietary polyphenols on mucosal and humoral immune responses, antioxidant defense and growth gene expression in beluga sturgeon (Huso huso). Aquaculture. 2020, 528, 735494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrogiovanni, M.; Martínez-Navarro, F.J.; Bowman, T.V.; Cayuela, M.L. Inflammation in Development and Aging: Insights from the Zebrafish Model. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25, 2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, S.; Rasal, K.D.; Chandra, T.; Prabha, R.; Iquebal, M.A.; Rai, A.; Kumar, D. Proteomics in fish health and aquaculture productivity management: Status and future perspectives. Aquaculture. 2023, 566, 739159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imperatore, R.; Orso, G.; Facchiano, S.; Scarano, P.P.; Hoseinifar, S.H.; Ashouri, G.; Guarino, C.; Paolucci, M. Anti-inflammatory and immunostimulant effect of different timing-related administration of dietary polyphenols on intestinal inflammation in zebrafish, Danio rerio. Aquaculture. 2023, 563, 738878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orso, G.; Solovyev, M.M.; Facchiano, S.; Tyrikova, E.; Sateriale, D.; Kashinskaya, E.; Pagliarulo, C.; Hoseinifar, H.S.; Simonov, E.; Varricchio, E.; Paolucci, M.; Imperatore, R. Chestnut shell tannins: Effects on intestinal inflammation and dysbiosis in Zebrafish. Animals. 2021, 11, 1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imperatore, R.; Tunisi, L.; Mavaro, I.; D'Angelo, L.; Attanasio, C.; Safari, O.; Motlagh, H.A.; De Girolamo, P.; Cristino, L.; Varricchio, E.; Paolucci, M. Immunohistochemical Analysis of Intestinal and Central Nervous System Morphology in an Obese Animal Model (Danio rerio) Treated with 3,5-T2: A Possible Farm Management Practice? Animals (Basel). 2020, 10, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, A.E.; Mekkawy, I.A.; Mahmoud, U.M.; Nagiub, M. Histopathological and histochemical effects of silver nanoparticles on the gills and muscles of African catfish (Clarias garepinus). Scientific African. 2020, 7, e00230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, W.; Sun, C.; Chen, Z.; Yang, D.; Zhou, Z.; Peng, X.; Tang, C. Alcohol Induces Zebrafish Skeletal Muscle Atrophy through HMGB1/TLR4/NF-κB Signaling. Life (Basel, Switzerland). 2022, 12, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manai, M.; Fiorillo, A.; Matuozzo, M.; Li, M.; D'Ambrosio, C.; Franco, L.; Scaloni, A.; Fogliano, V.; Camoni, L.; Marra, M. Phenotypical and biochemical characterization of tomato plants treated with triacontanol. Sci Rep. 2024, 14, 12096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Kirsch, R.; Koutrouli, M.; Nastou, K.; Mehryary, F.; Hachilif, R.; Gable, A.L.; Fang, T.; Doncheva, N.T.; Pyysalo, S.; Bork, P.; Jensen, L.J.; von Mering, C. The STRING database in 2023: protein–protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D638–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorice, A.; Siano, F.; Capone, F.; Guerriero, E.; Picariello, G.; Budillon, A.; Ciliberto, G.; Paolucci, M.; Costantini, S.; Volpe, M.G. Potential anticancer effects of polyphenols from chestnut shell extracts: Modulation of cell growth, and cytokinomic and metabolomic profiles. Molecules. 2016, 21, 1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ELbialy, Z.I.; Atef, E.; Al-Hawary, I.I.; Salah, A.S.; Aboshosha, A.A.; Abualreesh, M.H.; Assar, D.H. Myostatin-mediated regulation of skeletal muscle damage post-acute Aeromonas hydrophila infection in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus L.). Fish Physiol Biochem. 2023, 49, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fürst, D.O.; Osborn, M.; Nave, R.; Weber, K. The organization of titin filaments in the half-sarcomere revealed by monoclonal antibodies in immunoelectron microscopy: a map of ten nonrepetitive epitopes starting at the Z line extends close to the M line. J Cell Biol. 1988, 106, 1563–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatsumi, R.; Maeda, K.; Hattori, A.; Takahashi, K. Calcium binding to an elastic portion of connectin/titin filaments. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 2001, 22, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatham, A.S.; Shewry, P.R. Elastomeric proteins: biological roles, structures and mechanisms. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2000, 25, 567–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaitlina, S.Y. Tropomyosin as a Regulator of Actin Dynamics. International Review of Cell and Molecular Biology. 2015, 318, 255–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.; Qu, X.; Yang, N.; Liu, Z.; Wu, X. Changes in structure and allergenicity of shrimp tropomyosin by dietary polyphenols treatment. Food Res. Int. 2020, 140, 109997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, S.; Dowling, P.; Ohlendieck, K. Comparative Skeletal Muscle Proteomics Using Two-Dimensional Gel Electrophoresis. Proteomes. 2016, 4, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikawa, T.; Ulla, A.; Sakakibara, I. Polyphenols and their effects on muscle atrophy and muscle health. Molecules. 2021, 26, 4887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnetti, G.; Herrmann, H.; Cohen, S. New roles for desmin in the maintenance of muscle homeostasis. FEBS J. 2022, 289, 2755–2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hnia, K.; Ramspacher, C.; Vermot, J.; Laporte, J. Desmin in muscle and associated diseases: beyond the structural function. Cell Tissue Res 2015, 360, 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csapo, R.; Gumpenberger, M.; Wessner, B. Skeletal Muscle Extracellular Matrix - What Do We Know About Its Composition, Regulation, and Physiological Roles? A Narrative Review. Front Physiol. 2020, 11, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairallah, R.J.; O’Shea, K.M.; Ward, C.W.; Butteiger, D.N.; Mukherjea, R.; Krul, E.S. Chronic dietary supplementation with soy protein improves muscle function in rats. PLoS ONE. 2017, 12, e0189246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purslow, P.P. The Structure and Role of Intramuscular Connective Tissue in Muscle Function. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, A.S.; Engel, L.D.; Page, R.C. The effect of chronic inflammation on the composition of collagen types in human connective tissue. Coll Relat Res. 1983, 3, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Adachi, S.; Ura, K.; Takagi, Y. Properties of collagen extracted from Amur sturgeon Acipenser schrenckii and assessment of collagen fibrils in vitro. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019, 137, 809–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y.; He, S.Q.; Hong, H.Q.; Cai, Y.P.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, M. High doses of (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate from green tea induces cardiac fibrosis in mice. Biotechnol. Lett. 2015, 37, 2371–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castejón, M.L.; Alarcón-de-la-Lastra, C.; Rosillo, M.Á.; Montoya, T.; Fernández-Bolaños, J.G.; González-Benjumea, A.; Sánchez-Hidalgo, M. A new peracetylated oleuropein derivative ameliorates joint inflammation and destruction in a murine collagen-induced arthritis model via activation of the Nrf-2/Ho-1 antioxidant pathway and suppression of MAPKs and NF-κB activation. Nutrients. 2021, 13, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Li, M.; Chang, M.; Liu, R.; Qiu, J.; Wang, K.; Deng, C.; Shen, Y.; Zhu, J.; Wang, W.; et al. Inflammation: Roles in Skeletal Muscle Atrophy. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, B.; Singh, P. Inflammation: Biochemistry, cellular targets, anti-inflammatory agents and challenges with special emphasis on cyclooxygenase-2. Bioorganic Chem. 2022, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ono, T.; Takada, S.; Kinugawa, S.; Tsutsui, H. Curcumin ameliorates skeletal muscle atrophy in type 1 diabetic mice by inhibiting protein ubiquitination. Exp. Physiol. 2015, 100, 1052–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.C.; Yen, J.C.; Liou, K.T. Ameliorative effects of caffeic acid phenethyl ester on an eccentric exercise-induced skeletal muscle injury by down-regulating NF-κB mediated inflammation. Pharmacol. 2013, 91, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dugdale, H.F.; Hughes, D.C.; Allan, R.; Deane, C.S.; Coxon, C.R.; Morton, J.P.; Stewart, C.E.; Sharples, A.P. The role of resveratrol on skeletal muscle cell differentiation and myotube hypertrophy during glucose restriction. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2018, 444, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasta, G.R.; Nita-Lazar, M.; Giomarelli, B.; Ahmed, H.; Du, S.; Cammarata, M.; Parrinello, N.; Bianchet, M.A.; Amzel, L.M. Structural and functional diversity of the lectin repertoire in teleost fish: Relevance to innate and adaptive immunity. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2011, 35, 1388–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tateno, H.; Ogawa, T.; Muramoto, K.; Kamiya, H.; Hirai, T.; Saneyoshi, M. A novel rhamnose-binding lectin family from eggs of steelhead trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) with different structures and tissue distribution. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2001, 65, 1328–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammarata, M.; Parisi, M.G.; Benenati, G.; Vasta, G.R.; Parrinello, N. A rhamnose-binding lectin from sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) plasma agglutinates and opsonizes pathogenic bacteria. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2014, 44, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, J.B.; Borodinsky, L.N. Injury-induced Erk1/2 signaling tissue-specifically interacts with Ca2+ activity and is necessary for regeneration of spinal cord and skeletal muscle. Cell Calcium. 2022, 102, 102540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, N.H.; Kim, C.S.; Park, T.; Park, J.H.; Sung, M.K.; Lee, D.G.; Hong, S.M.; Choe, S.Y.; Goto, T.; Kawada, T.; Yu, R. Quercetin protects against obesity-induced skeletal muscle inflammation and atrophy. Mediators Inflamm. 2014, 2014, 834294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.Y.; Kim, O.H.; Kim, H.T.; Choi, J.H.; Yeo, S.Y.; Kim, N.S.; Park, D.S.; Oh, H.W.; You, K.H.; De Zoysa, M.; Kim, C.H. Establishment of a transgenic zebrafish EF1α: Kaede for monitoring cell proliferation during regeneration. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2013, 34, 1390–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.L.; Dzhagalov, I.L. Metabolite Transporters—The Gatekeepers for T Cell Metabolism. Immunometabolism. 2019, 1, e190012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, L.A.J.; Kishton, R.J.; Rathmell, J. A guide to immunometabolism for immunologists. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 553–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, B.; Polansky, M.M.; Harry, D.; Anderson, R.A. Green tea polyphenols improve cardiac muscle mRNA and protein levels of signal pathways related to insulin and lipid metabolism and inflammation in insulin-resistant rats. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2010, 54, S14–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, Y.; Tamura, Y.; Kouzaki, K.; Nakazato, K. Dietary apple polyphenols enhance mitochondrial turnover and respiratory chain enzymes. Exp. Physiol. 2023, 108, 1295–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Wang, M.; Du, Z.; Li, Z.; Han, T.; Xie, Z.; Gu, W. Tea polyphenol EGCG enhances the improvements of calorie restriction on hepatic steatosis and obesity while reducing its adverse outcomes in obese rats. Phytomedicine. 2025, 141, 156744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obrenovich, M.; Li, Y.; Tayahi, M.; Reddy, V.P. Polyphenols and Small Phenolic Acids as Cellular Metabolic Regulators. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2022, 44, 4152–4166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).