Abstract. There is significant need for development of a new environmentally friendly, extraction-free sample collection medium that can effectively preserve and protect genetic material for point-of-care, and/or self-collection, home-collection, and mail-back testing. Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment (SELEX) was used to create anti-ribonuclease (RNase) Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) aptamers against purified RNase A conjugated to paramagnetic carboxylated beads. Following 8 rounds of SELEX carried out under various stringency conditions, e.g., selection using Xtract-Free™ (XF) specimen collection medium, and elevated ambient temperature of 28 ºC, a panel of 5 aptamers was chosen following bioinformatic analysis using next-generation sequencing. The efficacy of aptamer inactivation of RNase was assessed by monitoring Ribonucleic acid (RNA) integrity by fluorometric and real-time RT-PCR analysis. Inclusion of aptamers in reaction incubations resulted in an 8,800 to 11,200-fold reduction of RNase activity, i.e., digestion of viral RNA compared to control. Thus, anti-RNase aptamers integrated into XF collection medium as well as other commercial reagents and kits have great potential for ensuring quality intact RNA for subsequent genomic analysis.

1. Introduction

Aptamers are short nucleic acid oligonucleotides (typically 20–100 bases) that like antibodies recognize and bind to biomolecular targets, including proteins [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. They are generated through a cyclic enrichment process known as Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment (SELEX) [1). During SELEX, a large chemically synthesized library of random nucleic acid sequences (approximately 10^15) is passed over an immobilized target molecule. Sequences that do not bind to the target are washed away, while those that do bind are subsequently teased off and amplified using polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Through repeated cycles of incubation with target, washing, and amplification, a subset of binding sequences with high target affinity is selected,

i.e., enriched [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6].

Aptamers offer several advantages over traditional antibodies. First, they can be produced

in vitro relatively easily and inexpensively in a standard molecular laboratory without need for animals or culturing techniques. Since they are oligonucleotides, they are safe, chemically stable, and can be modified with functional groups or reporter molecules. Additionally, aptamers are small (approximately 20 kDa), which enables them to bind to molecular locations that are inaccessible to antibodies due to their larger size (around 150 kDa). Consequently, aptamers have been used for a variety of applications, including biosensing, diagnostics, therapeutics, and basic research [

3,

7,

8,

9,

10]. However, to the best of our knowledge aptamers have not been used for preservation of ribonucleic acid (RNA) genomic targets in diagnostic sample collection media as described.

Nucleases are enzymes that cleave phosphodiester bonds in nucleic acids. RNases are one of many nucleases found in various microbes and cell types across all organisms, including prokaryotes and eukaryotes [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. They are widespread and pose a significant challenge to those laboratories that work with small quantities of RNA, especially from collected samples. Ribonucleases (RNases) can be introduced inadvertently as contaminants or, more likely, released endogenously from cells and microbes in medium used in sample collection and transport. RNase digestion in collected samples becomes even more problematic when biological specimens or environmental samples containing high levels of nucleases are collected at point-of-care,

i.e., home collection, or remote testing sites, pharmacies, or physician's offices where specimens often sit at ambient or higher temperatures until processed in the molecular diagnostic testing laboratory [

16,

17,

18]. Thus, there is an urgent need to protect collected sample RNA from degradation by RNases, as well as degradation from use of harsh chemicals dangerous to humans and the environment.

During routine respiratory collection, nasopharyngeal or nasal anterior swabs are often placed into viral or universal transport mediums (VTM and UTM). VTM and UTM are complex mixtures of sugars, salts, and buffers developed more than four decades ago for viral and bacterial culturing [

19,

20]. A major drawback of VTM and UTM is that they do not include any RNase-inactivating capacity. Thus, labile viral and host RNA from samples collected in VTM and UTM are susceptible to significant RNase degradation,

i.e., decrease in nucleic acid targets. More recently, molecular transport mediums (MTMs) such as PrimeStore (Longhorn Vaccines and Diagnostics, Bethesda, MD) and eNat (Copan Diagnostics, Brescia, Italy) were developed to disrupt cell membranes and inactivate/denature proteins including RNases [

21,

22,

23]. MTMs are similar in composition to standard cell lysis buffer and use the same chemical approach to shear and disrupt microbial lipid bilayers [

21]. However, the use of MTMs for sample collection presents four significant limitations: 1) Typically, MTMs contain toxic guanidine compounds that are extremely harmful if accidentally contacted via the skin or ingested [

24,

25]; 2) they are hazardous to the environment, and can release potentially toxic cyanide gas if contact with bleach products during cleanup occurs [

26,

27]; 3) they cannot be used for lateral flow, rapid antigen and protein detection tests, and 4) they require nucleic acid extraction prior to detection, a process that is laborious and costly, requiring additional nucleic acid extraction reagents.

Xtract-Free™ (XF) is a ‘next-generation’ biospecimen collection, storage, and transport medium recently developed for direct, extraction-free (extraction-less) use with quantitative PCR (qPCR) and other nucleic acid-based detection formats [

28]. XF is an optimized, non-toxic blend of reagents that preserves RNA, DNA, and proteins of collected samples at ambient temperature and above. The reagents in XF function to gently lyse membranes including those of viruses, and subsequently preserves labile RNA. Importantly, samples collected in XF can be analyzed directly using qPCR and non-qPCR methodologies without nucleic acid extraction [

28]. Furthermore, XF contains no alcohol, guanidine, or other hazardous surfactants making it ideal for use with lateral flow formats for at-home and self-testing use (Daum

et al., 2024, unpublished).

We report here generation of anti-RNase DNA aptamers for preservation of collected biospecimen RNA in concert with Xtract-Free™ collection medium. Our results demonstrate successful RNase inactivation by RNase binding aptamers and their utility in a novel specimen collection medium. This is an important step for enhancement of RNA quality impacting detection/quantitation of specific targets of interest and downstream RNA molecular analysis from collection biospecimens.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Conjugation of RNase A to Carboxy Paramagnetic Beads

Sera-Mag™ Carboxylate-Modified Magnetic Particles (Cytiva, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) were used for conjugation of purified RNase A (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) by covalent linkage as described below. Carboxy beads stored at 5°C were allowed to come to ambient temperature and were mixed thoroughly prior to use. A total of 1 mL of beads (50 mg/mL) was added to 7.5 mL nuclease-free water and mixed by pipetting. The bead suspension was magnetically partitioned with a magnet stand for 1 minute until clear, after which the fluid was aspirated and discarded. Using nuclease-free water, beads were washed two times to remove trace bead solution, followed by addition of 7.5 mL 0.1 M NaOH two times by mixing, magnetic partitioning for 1 minute, aspiration, and discarding fluid. Beads were then washed an additional two times with 7.5 mL nuclease-free water to remove trace NaOH. A total of 7.5 mL 0.1 M 2-(N-Morpholino) ethanesulfonic acid (MES; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was then added, the bead suspension was removed from the stand, and the contents were thoroughly mixed. In a sterile 15-mL Falcon tube, 200 mg 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and 100 mg N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) were combined with 2 mL MES (0.1 M; pH 5) and mixed thoroughly. The carboxy bead suspension was partitioned magnetically, and the MES buffer was aspirated and discarded. To activate the carboxy beads, 2 mL EDC/NHS solution was added and the bead suspension, vortexed briefly, and placed on a mini-tube rotator for 1 hour. Following mixing, the bead suspension was placed on the magnet stand for 1 minute. The partitioned solution was aspirated, and the beads were resuspended in 1 mL MES (0.1 M; pH 5). In a separate sterile microcentrifuge tube, a solution of RNase A (3 mg/mL; Roche, Mannheim, Germany) was prepared by dilution in MES buffer (0.1 M, pH 5.0). To bind RNase to beads, 1 mL RNase protein (3 mg/mL) was added and mixed gently on a mini tube rotator for 1 hour. The reaction mixture was then placed on the magnet stand, and the magnetically partitioned fluid was removed and discarded. The bead-RNase conjugate was resuspended in 2 mL Trizma-HCl (0.1 M; Sigma, St. Louis, MO), and mixed thoroughly for 1 hour on a mini tube rotator. The suspension was then placed on the magnet stand for 1 minute, and the fluid was removed and discarded. The bead-RNase conjugate was washed twice using 7.5 mL PBS/0.1% (v/v) Tween-20 (Sigma; St. Louis, MO), and finally resuspended in 7.5 mL PBS/0.1% Tween-20, mixed well, and stored at 5ºC until used.

2.2. In Vitro SELEX Selection of Anti-RNase A Aptamers

The synthetic aptamer library was synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA, USA) and consisted of the following 86 nucleotides: 5’-TAG-GGA-ACA-GAA-GGA-CAT-ATG-AT-(N40)-TTG-ACT-AGT-ACA-TGA-CCA-CTT-GA-3’. A 40-nt randomized region (10^25 sequences) was flanked on both sides by a 23-nt forward and reverse primer region for polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Additionally, SELEX-Forward, 5’-TAG-GGA-AGA-GAA-GGA-CAT-ATG-AT, SELEX-Reverse, 5’-TCA-AGT-GGT-CAT-GTA-CTA-GTC-AA-3’, and a 5’-phosphorylated reverse, 5’-Phos-TCA-AGT-GGT-CAT-GTA-CTA-GTC-AA-3’ were utilized (IDT, Coralville, IA, USA). The aptamer library and all primers were diluted to 100 µM stocks. All primers were utilized at a 20 µM working dilution.

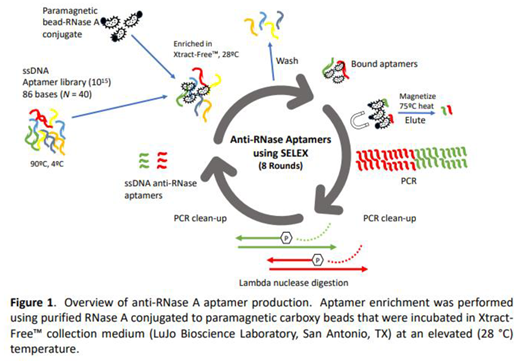

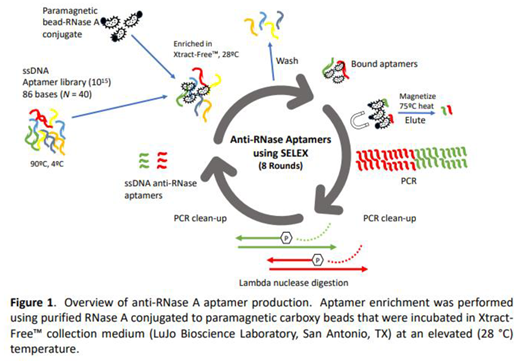

A total of 8 SELEX rounds were performed (Figure 1). A high SELEX stringency for aptamers was employed for RNase binding since selection was performed: 1) directly in Xtract-Free™ medium; and 2) at elevated ambient temperature (28 °C). For SELEX round 1, an aliquot of 100 µM aptamer library was diluted with nuclease-free water to a concentration of 10 nMol. The library was subsequently diluted to 2 nMol (10^15 molecules) by adding 20 µL ssDNA library to 80 µL Xtract-Free™ medium in a 0.2 PCR reaction tube. For proper folding, aptamers were first heated to 90 °C (10 minutes) and then cooled to 4 °C (15 minutes) using a standard PCR thermocycler (ABI 2720, Foster City, CA). Using a magnet stand, 100 µL bead-RNase A conjugate was washed three times with 400 µL of SELEX binding buffer and resuspended in 100 µL Xtract-Free™ collection medium. Next, 100 µL aptamer library was added to the tube containing 100 µL bead-RNase conjugate/Xtract-Free™ medium. The contents were pipetted up and down several times to mix and subsequently incubated in a heat block at elevated ambient temperature (28 °C) for 30 minutes with intermittent pipetting every 5 minutes. The mixture was magnetically partitioned and washed twice with 400 µL Xtract-Free™ to remove unbound aptamers. During each washing step, the tube was rotated 3-5 times manually to ensure bound aptamers were not inadvertently dislodged from the beads. After two washes, bead-RNase conjugate with bound aptamers (with no fluid) was briefly removed from the stand to allow beads to settle to the bottom of the 1.5 mL tube, placed back on the magnet stand, and any remaining residual volume was carefully removed. The tube with bound aptamers was left open on the stand and air-dried for 5 minutes. To elute bound aptamers, 200 µL nuclease-free water (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) was added to the dried bead tube, pipetted up and down, and incubated at 70 °C for 7 minutes. After incubation, the microcentrifuge was briefly vortexed, placed on the magnet stand and magnetically partitioned, and the solution containing eluted aptamers was transferred to a new microcentrifuge tube.

2.3. Polymerase Chain Reaction Amplification

PCR to amplify bound aptamers was performed during each SELEX round in a 50 µL reaction volume of “MasterMix” consisting of: 32 µL nuclease-free water (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA), 10 µL 5X PCR Buffer (Bioline, London, England), 2 µL forward and phosphate-labeled reverse primers (20 µM each), and 1 µL MyTaq polymerase (BioLine, London, England). The PCR reaction was performed in 0.2 mL PCR reaction tubes and consisted of an initial denature at 95 °C for 2 minutes, followed by 8 cycles of 94 °C for 30 seconds, 55 °C for 20 seconds, and 72 °C for 30 seconds. A final extension step was performed at 72 °C for 5 minutes. Positive and negative (no template) control reactions were included in each PCR run. A total of 10 µL of PCR product consisting of approximately 86 bp was visualized by UV illumination on a 2% agarose gel with ethidium bromide staining. Prior to visualization, gels were electrophoresed in TRIS borate EDTA (TBE) buffer at 90 volts for 1 hour. The remaining 40 µL PCR product was cleaned using the NEB Monarch PCR and DNA Cleanup Kit (NEB, Ipswich, MA) as specified in the user’s manual.

2.4. Lambda Nuclease Digestion

To recover single stranded DNA (ssDNA) for seven subsequent SELEX rounds, purified PCR amplicons were subjected to lambda nuclease digestion (NEB, Ipswich, MA). Briefly, 40 µL purified PCR product were added to 5 µL 10X Lambda exonuclease buffer, 1 µL enzyme, and 4 µL nuclease-free water, gently mixed by pipetting, and incubated at 37 °C for 30 minutes. After double stranded DNA (dsDNA) to ssDNA digestion, the reaction was heat-inactivated at 75 °C for 10 minutes. ssDNA was purified using the NEB Monarch PCR and DNA Cleanup Kit according to manufacturer’s instructions and eluted in a final volume of 20 µL. The resulting SELEX product was used in subsequent rounds or stored at -20 °C until used.

2.5. Next-Generation Sequencing of SELEX Aptamer Rounds

The ssDNA pools from SELEX rounds 1 to 8 (R1-R8) that were bound to immobilized RNase were prepared for next-generation sequencing (NGS) analysis following an amplicon sequencing library preparation. In brief, PCR was used to attach 5’ Illumina adapter overhands to the SELEX forward primer (Ill-Adapter-Selex-Forward (56 bp)): 5’-TCG TCG GCA GCG TCA GAT GTG TAT AAG AGA CAG-TAG GGA AGA GAA GGA CAT ATG AT) and reverse primer (Ill-Adapter-Selex-Reverse (57 bp)): 5’-GTC TCG TGG GCT CGG AGA TGT GTA TAA GAG ACA G-TCA AGT GGT CAT GTA CTA GTC AA). PCR reactions were carried out in 50 µL reactions containing 32 µL of nuclease-free water (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA), 10 µL 5X PCR buffer (Bioline, London, England), and 2 µL forward and reverse primers (20 µM each). A total of 5 µL of ssDNA aptamer template was added to each reaction. PCR cycling conditions were 3 min at 95°C, followed by 11 cycles of 15s at 95°C, 15s at 55°C, 15s at 72°C, and a final extension step for 2 min at 72°C. Due to the high initial concentration of ssDNA in Round 1, only 8 cycles were used. The PCR products were checked using UV illumination on a 2% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. A second NGS-PCR used primers containing adapter sequences with Illumina-specific barcodes (i7 and i5) to attach the oligonucleotides to the flow cell. For the second PCR, reactions were carried out in a 25 µL reaction volumes containing: 1x High-Fidelity Master Mix and 1 µM NGS_PCR#2 primers (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Purified first NGS-PCR product (2.5 µL) was added to each reaction and cycled at 95°C for 30s, followed by 6 cycles of 10s at 95°C, 30s at 55°C, 30s at 72°C, and a final extension step for 2 minutes at 72°C. The PCR products were purified per manufacturer’s instructions using the Agencourt AMPure XP Purification System (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA). The final DNA concentration for each product was determined using a Qubit fluorometer 4.0 with the DNA Quantification Kit (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The eight samples (R1–R8) were mixed in an equimolar ratio to a final concentration of 4 nM, and the final NGS library was clustered at 8 pM with 10% of the 8 pM PhiX internal control added to the run. Sequencing was performed using an Illumina MiSeq platform (San Diego, CA) with the MiSeq Reagent Micro Kit v2 (150 cycles) cartridge in paired-end mode. Sequencing data were demultiplexed using bcl-2fastq2 v2.20 (Illumina, San Deigo, CA).

2.6. Evaluation of ssDNA Aptamers Using Substrate Nuclease Detection

An evaluation of RNase digestion and protection using anti-RNase aptamers was performed with the RNaseAlert Substrate Nuclease Detection System™ according to manufacturer’s guidelines (Integrated DNA Technology, Coralville, IA). Intact ssRNA does not fluoresce, but ssRNA cleavage by RNase gives rise to fluorescence which is: 1) visible under UV light, and 2) quantifiable using a fluorometer.

The assay was carried out by adding 5 µL 10X Buffer, 45 µL 100 µM aptamer, and a RNase at a final concentration of 20 µg/mL. Following addition of RNase, samples were immediately vortexed, and measurements at 470 nM were taken every 30 seconds for 5 minutes using a Qubit 4 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA). Visual inspection under UV light was conducted after 1 hour and on day 5.

2.7. Evaluation of ssDNA Anti-RNase Aptamers Using qPCR Analysis

Enzymatic digestion reactions using purified influenza A (H3N2) viral RNA in the presence of bead-RNase conjugate in the presence of anti-RNase aptamers was evaluated in a 25 µL reaction mixture consisting of: 5 µL bead-RNase conjugate or naked (control) beads, 10 µL Xtract-Free™ medium, and 10 µL purified vRNA (10^6 copies/mL). For reactions containing anti-RNase aptamers, a total of 10 µL aptamer (20 µM final concentration) was used in place of Xtract-Free™ medium. Samples were mixed, incubated for 15 minutes at 37 ºC, magnetically partitioned for 1 minute, and the soluble fraction was then transferred to new sterile 1.5 mL tube for analysis.

Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) was used to assess aptamer inhibition of RNase. The TaqPath 1-Step RT-qPCR Master Mix (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) was utilized following manufacturer's instructions. A universal influenza A virus assay targeting a conserved region of the matrix gene was used with a final concentration of 0.5 µM for forward and reverse primers, and 0.1 µM for internal hydrolysis (TaqMan) probe as previously described [

29]. Real-time detection was carried out using a QuantStudio 5 instrument (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA). Each qRT-PCR run included duplicate positive and negative control reactions. Lower C

T values indicate a higher initial viral RNA concentration, with a value >40 indicating no detection. The real-time thermocycling parameters were as follows: 50 ºC for 20 minutes (reverse-transcription), 95 ºC for 2 minutes (hot-start), followed by 40 cycles of 95 ºC for 15 seconds and 60 ºC for 30 seconds.

3. Results

Figure 1 provides a detailed overview of the multi-step process used to isolate and identify the highest affinity anti-RNase aptamers from a starting pool of 10^15 candidate sequences. The SELEX procedure involved 8 iterative cycles of incubation, washing, and amplification gradually enriching for aptamer sequences that bind to the target protein, RNase A. Incubation of aptamers that bind to the bead-RNase conjugate was performed in XF medium, and at an elevated temperature of 28°C, conditions similar to those for collection of biological samples in the field (Figure 1).

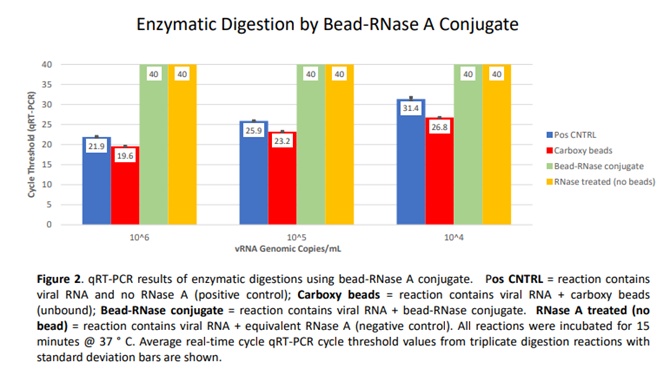

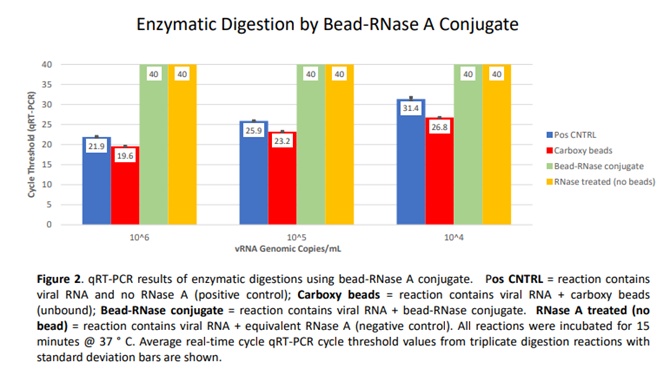

Prior to SELEX, an assessment was made on chemically immobilized RNase A, i.e., paramagnetic bead RNase conjugate using qRT-PCR analysis (Figure 2). Bead-RNase conjugate was magnetically partitioned and washed three times to ensure removal of unbound enzyme. Subsequently, three concentrations (10^6, 10^5, and 10^4 genomic copies/mL) of SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA were used as a substrate to confirm active enzymatic degradation by bead immobilized RNase A. Compared to Cycle threshold (CT) values from positive control vRNA alone (Avg CT = 21.9, 25.9, 31.4 for 10^6, 10^5, and 10^4 copies/mL, respectively), and positive control vRNA incubated with unmodified carboxy beads (Avg CT = 19.6, 23.2, and 26.8), equivalent vRNA from thrice-washed bead-RNase conjugate incubations revealed undetectable viral RNA (CT = 40) for all three target concentrations. A negative control containing free RNase A and viral RNA was also included. The data clearly indicate the complete digestion of target viral RNA by bead-RNase conjugate. The figure indicates triplicate averages with standard deviation shown (Figure 2).

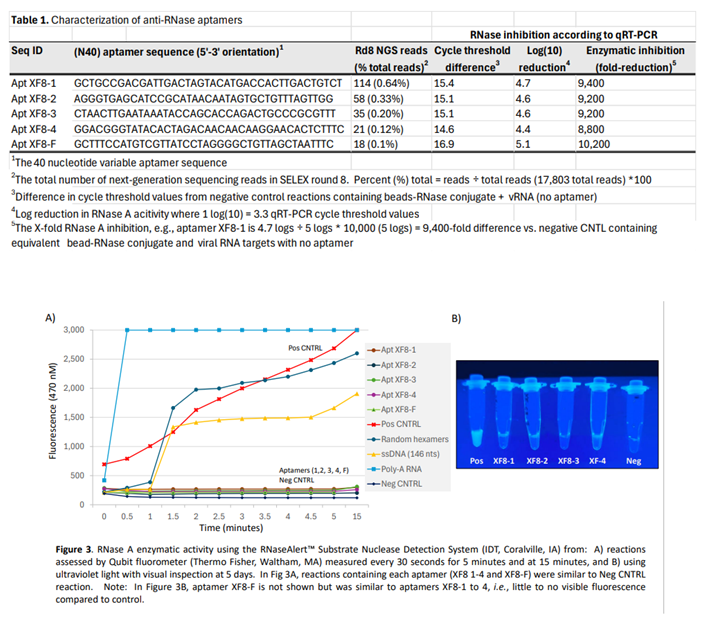

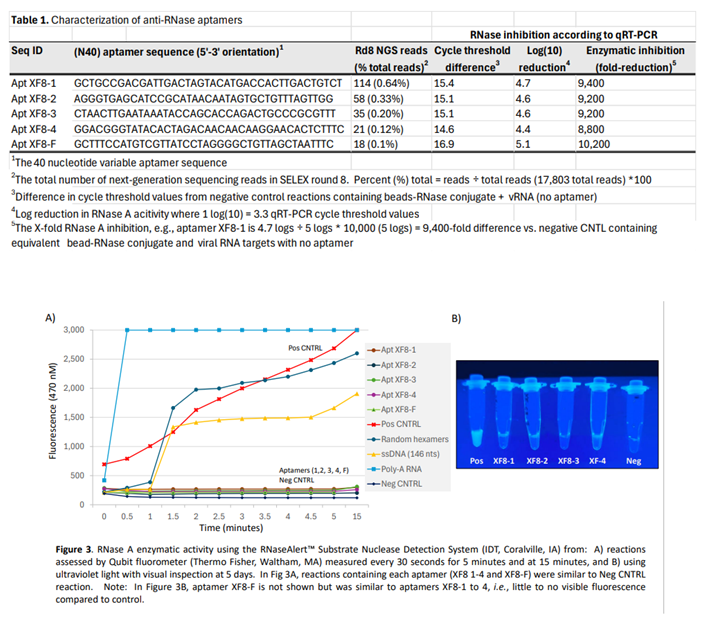

The top five anti-RNase aptamers were chosen based on their presence in all eight SELEX rounds (as determined by next-generation sequencing) and their highest frequency (unique reads ÷ total reads in round 8 x 100) based on total reads obtained in the final 8th round (Table 1). To assess inactivation of RNase by DNA aptamers, a single-stranded RNA substrate with a 5' fluorescein (reporter) and 3' dark quencher was monitored fluorometrically every 30 second for 5 minutes, and at t = 15 minutes. After 15-minutes, ssRNA targets in the presence of the five anti-RNase aptamers exhibited minimal to no degradation, similar to controls without RNase. In contrast, reactions containing random hexamers, a 'nonsense' ssDNA sequence (146 nucleotide ssDNA non-aptamer), and poly-A RNA incubated with RNase A were readily degraded (Figure 3, panel A). When examined visually under UV transillumination after 5 days, anti-RNase aptamers (XF8-1 to XF8-4) displayed minimal to no fluorescence in contrast to control reactions. This indicates that all 5 DNA aptamers effectively bind and inhibit RNase A, as evidenced by the absence of ssRNA digestion (Figure 3, panel B).

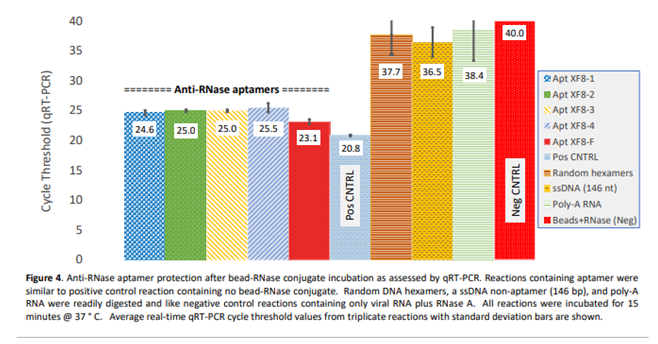

Similarly, the efficacy of anti-RNase aptamers to inactivate RNase A was evaluated by qRT-PCR. This was accomplished by exposing an abundance of RNase A enzyme to naked, purified influenza A viral RNA substrate (10^6 copies/mL) for a duration of 15 minutes at 37ºC. The results indicate when compared to control reactions containing equivalent RNA concentration but no RNase A enzyme, the five aptamers exhibited comparable levels of RNase inactivation as evidenced by qRT-PCR cycle threshold values. Furthermore, in comparison to negative control reactions (i.e., RNA plus RNase with no aptamers) which were not detected (cycle threshold value of 40), the reactions containing aptamers exhibited cycle-threshold values ranging from 14.6 to 16.9. These values translate to an 8,800- to 10,200-fold reduction in RNase A activity. Conversely, other oligos such as random hexamers, a 146-nucleotide ssDNA oligomer, and poly-A RNA did not indicate any significant inactivation of RNase A (Figure 4).

4. Discussion

RNase A is a small enzyme (13.7 kilodaltons) consisting of a single 124 amino acid polypeptide chain. The active site of RNase A contains highly conserved histidine, lysine, and tyrosine residues that form hydrogen bonds and electrostatic interactions with the phosphate backbone of RNA, enabling the enzyme to cleave phosphodiester bonds of RNA into component nucleotides [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. The enzyme predominantly targets single-stranded RNA regions rich in cytosine and uracil residues. RNases are particularly problematic in RNA detection and genomics applications since they are highly resistant to heat degradation. Additionally, RNases are abundant in secretions and skin as well as in copious amounts in the cells of collected biospecimens.

In a typical molecular diagnostic laboratory, special precautions are commonly used measures for minimizing the deleterious effects of ubiquitous contamination by RNases in reagents and kits used for genomics application. Some molecular procedures that involve RNA analysis employ the use of an RNase Inhibitor (RI), natural or recombinant proteins, that bind to and inhibit RNase enzymes. RNase inhibitors are often used in kits for isolating RNA from collected specimens. During the nucleic acid extraction and isolation process, cellular membranes are disrupted, releasing endogenous RNases that rapidly degrade target RNA. Adding an RI to RNA extraction buffers or other genomic steps prevents this degradation, enabling the integrity of high-quality, intact RNA for downstream applications including RT-PCR, RNA-Seq, and transcriptome analysis. However, the use of RI in sample collection mediums presents several insurmountable challenges. RNase inhibitors are relatively expensive reagents, thus an effective concentration ensuring complete inhibition is cost prohibitive, particularly in a collection medium where liquid volumes are usually 1 to 3 mL per vial. Furthermore, commercially available RI (recombinant enzymes) present signification stability challenges over extended shelf-life and temperature range.

Sample collection is the first and most critical step in molecular diagnostic testing. Thus, the appropriate transport medium is essential for maintaining the integrity of genomic targets. First-generation transport medium, known commonly as Viral and Universal Transport Media (VTM/UTM) were developed in the 1980’s for the purpose of maintaining microbial viability for culture detection techniques. Commercial VTM/UTM typically consist of identical formulation that include balanced salts, antibiotics to prevent bacterial and fungal growth, a buffer and indicator to maintain pH, and bovine serum albumin to support virus survival. In 2007, 2

nd-generation media, referred to commonly as Molecular Transport Medium (MTM), was developed to shear and disrupt cellular membranes for subsequent nucleic acid testing. Second generation transport mediums typically contain guanidine,

e.g., guanidine thiocyanate and one or more detergents,

e.g.,

N-lauroylsarcosine designed for chemical disruption of cellular lipid bilayers and stabilization of nucleic

acids making MTM suitable for use only in nucleic acid tests such as PCR [

21].

Despite their continued use, both VTM/UTM and MTM have limitations. One drawback of VTM/UTM is that it can only preserve live viruses for a finite period,

i.e., typically 48-72 hours when kept refrigerated after which the viability of the virus significantly decreases, leading to possible false negative results [

30,

31,

32,

33]. Furthermore, most VTM/UTM usually require cold-chain transportation, and collected pathogens are potentially infectious, adding complexity and cost to sample handling, shipment, and transport [

30,

31,

32,

33]. Conversely, MTM contains harsh and hazardous chemicals, requires a nucleic acid extraction step, and does not maintain viral infectivity and protein structure which is essential for virological studies, culture-based detection methods, and rapid antigen/lateral flow tests.

The utilization of aptamers for the purpose of binding and inactivating RNases from collected samples represents a novel and innovative approach in sample collection. This method allows for the preservation of RNA integrity at ambient or elevated temperatures, eliminating the need for cold-chain transportation, and contributing to a safer and more environmentally friendly medium for point-of-care collection and shipping. Our study entailed 8 rounds of SELEX selecting for anti-RNase aptamers (Figure 1, Table 1) and was achieved using paramagnetic bead-RNase conjugate (Figure 2). Subsequently, we demonstrated binding and inhibition of bead-RNase conjugate by anti-RNase aptamers in Xtract-Free™ collection medium using direct enzymatic fluorometer assessment (Figure 3), and real-time qRT-PCR (Figure 4). Integration of harmless DNA aptamers into a chemically safe collection medium, i.e., XF significantly improves preservation of collected samples, especially in remote or field-based collection scenarios where rapid processing is not feasible.

In contrast to other mediums containing harsh chaotropic and surfactant agents for chemically inactivating nucleases, a DNA aptamer consists solely of a short and unique sequence of nucleic acid, which has no significant impact on downstream applications, including direct use of extraction-free PCR. Furthermore, the use of 'carrier RNA' during nucleic acid extraction has been demonstrated to improve the efficiency and yield of RNA and DNA [

34]. Nucleic acid carrier, utilized in some commercial MTMs and extraction kits, to increase extraction efficiency from low target samples during nucleic acid extraction [

34]. Including DNA aptamers in collection medium to enhance RNA preservation by inactivation of RNase may also contribute to improving the efficiency and yield of nucleic acids by the aptamer functioning as carrier for low target sample RNA during nucleic acid extraction.

The incorporation of DNA aptamers into Xtract-Free™, a chemically safe, and environmentally friendly 'third generation' collection medium, is a significant advancement in preserving RNA integrity. The targeting and inactivation of RNase by DNA aptamers was shown to effectively protect RNA, thereby improving the detection of RNA genomic targets.

5. Conclusions

This report introduces the first ever use of anti-RNase aptamers selected specifically to target and neutralize RNase A. Xtract-Free™ collection medium which incorporates these aptamers, offers a safe and environmentally friendly option for molecular and lateral flow diagnostic tests eliminating the need for nucleic acid extraction prior to PCR. Inclusion of anti-RNase aptamer in collection and transport mediums ensures preservation and stabilization of RNA for PCR and other RNA related genomic applications, e.g., RNA-Seq and transcriptome analysis. Xtract-Free™ medium, containing anti-RNA aptamers, expands the scope of collection mediums beyond conventional VTM/UTM and MTM to meet a growing need for safe medium for use in point-of-care, self-collection, return mail, and home collection formats.

References

- Ellington, A., Szostak, J. In vitro selection of RNA molecules that bind specific ligands. Nature 346, 818–822 (1990). [CrossRef]

- Wang T, Chen C, Larcher LM, Barrero RA, Veedu RN. Three decades of nucleic acid aptamer technologies: Lessons learned, progress and opportunities on aptamer development. Biotechnol Adv. 2019 Jan-Feb;37(1):28-50. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Lai BS, Juhas M. Recent Advances in Aptamer Discovery and Applications. Molecules. 2019 Mar 7;24(5):941. [CrossRef]

- Kolm C, Cervenka I, Aschl UJ, Baumann N, Jakwerth S, Krska R, Mach RL, Sommer R, DeRosa MC, Kirschner AKT, Farnleitner AH, Reischer GH. DNA aptamers against bacterial cells can be efficiently selected by a SELEX process using state-of-the art qPCR and ultra-deep sequencing. Sci Rep. 2020 Dec 1;10(1):20917. [CrossRef]

- Citartan, M., Tang, TH., Tan, SC. et al. Conditions optimized for the preparation of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) employing lambda exonuclease digestion in generating DNA aptamer. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 27, 1167–1173 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Kohlberger M, Gadermaier G. SELEX: Critical factors and optimization strategies for successful aptamer selection. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2022 Oct;69(5):1771-1792. [CrossRef]

- Afrasiabi S, Pourhajibagher M, Raoofian R, Tabarzad M, Bahador A. Therapeutic applications of nucleic acid aptamers in microbial infections. J Biomed Sci. 2020 Jan 3;27(1):6. [CrossRef]

- Sefah K, Phillips JA, Xiong X, Meng L, Van Simaeys D, Chen H, Martin J, Tan W. Nucleic acid aptamers for biosensors and bio-analytical applications. Analyst. 2009 Sep;134(9):1765-75. [CrossRef]

- Kim TH, Lee SW. Aptamers for Anti-Viral Therapeutics and Diagnostics. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Apr 17;22(8):4168. [CrossRef]

- González VM, Martín ME, Fernández G, García-Sacristán A. Use of Aptamers as Diagnostics Tools and Antiviral Agents for Human Viruses. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2016 Dec 16;9(4):78. [CrossRef]

- Yang, W. Nucleases: Diversity of structure, function and mechanism. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2011, 44, 1–93. [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg HF. RNase A ribonucleases and host defense: an evolving story. J Leukoc Biol. 2008 May;83(5):1079-87. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1107725. Epub 2008 Jan 22. PMID: 18211964; PMCID: PMC2692241. [CrossRef]

- McPherson A, Brayer G, Cascio D, Williams R. The mechanism of binding of a polynucleotide chain to pancreatic ribonuclease. Science. 1986 May 9;232(4751):765-8. doi: 10.1126/science.3961503. PMID: 3961503. [CrossRef]

- Nichols NM, Yue D. Ribonucleases. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2008 Oct; Chapter 3: Unit3.13.

- Neira JL, Rico M. Folding studies on ribonuclease A, a model protein. Fold Des. 1997;2(1):R1-11. [CrossRef]

- Strom SP. Fundamentals of RNA Analysis on Biobanked Specimens. Methods Mol Biol. 2019; 1897:345-357.

- Bai H, Zhao J, Ma C, Wei H, Li X, Fang Q, Yang P, Wang Q, Wang D, Xin L. Impact of RNA degradation on influenza diagnosis in the surveillance system. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021 Aug;100(4):115388. [CrossRef]

- Fleige S., Pfaffl M.W. RNA integrity and the effect on the real-time qRT-PCR performance. Mol. Aspects Med. 2006; 27:126–139.

- Lennette WEH, Halonen P, Murphy FA, et al. Laboratory Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases Principles and Practice_ VOLUME II Viral, Rickettsial, and Chlamydial Disease, n.d.).

- Schaeffer M. Manual of clinical microbiology. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1971;20(3):508–508. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1971. [CrossRef]

- Daum LT, Worthy SA, Yim KC, Nogueras M, Schuman RF, Choi YW, Fischer GW. A clinical specimen collection and transport medium for molecular diagnostic and genomic applications. Epidemiology and Infection. 2011 Nov;139(11):1764-1773. [CrossRef]

- Banik S, Saibire K, Suryavanshi S, Johns G, Chakravorty S, Kwiatkowski R, Alland D, Banada PP. Inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 virus in saliva using a guanidium based transport medium suitable for RT-PCR diagnostic assays. PLoS One. 2021 Jun 11;16(6): e0252687.

- Mosscrop L, Watber P, Elliot P, Cooke G, Barclay W, Freemont PS, Rosadas C, Taylor GP. Evaluation of the impact of pre-analytical conditions on sample stability for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA. J Virol Methods. 2022 Nov; 309:114607.

- Drygin YF, Butenko KO, Gasanova TV. Environmentally friendly method of RNA isolation. Anal Biochem. 2021 May 1; 620:114113. [CrossRef]

- Ertell. K. A Review of Toxicity and Use and Handling Considerations for Guanidine, Guanidine Hydrochloride, and Urea. 2006. Available at: www.pnnl.gov/main/publications/external/technical_reports/PNNL-15747.pdf.

- Crotti. N. (June, 2020). FDA warns of cyanide gas danger with improper use of Hologic COVID-19 tests. Available at: www.massdevice.com/fda-warns-of-cyanide-gas-danger-with-improper-use-of-hologic-covid-19-tests/.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). CDC’s Laboratory Outreach Communication System (LOCS). Available at: www.cdc.gov/locs/2020/mtm_and_cyanide_gas.html.

- Daum, LT; Rodriguez, JD.; Ward, SR.; Chambers, JP. Extraction-Free Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Viral RNA Using LumiraDx’s RNA Star Complete Assay from Clinical Nasal Swabs Stored in a Novel Collection and Transport Medium. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 3010.

- Daum LT, Canas LC, Arulanandam BP, Niemeyer D, Valdes JJ, Chambers JP. Real-time RT-PCR assays for type and subtype detection of influenza A and B viruses. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2007 Jul;1(4):167-75. [CrossRef]

- Kim N, Kwon A, Roh EY, Yoon JH, Han MS, Park SW, Park H, Shin S. Effects of Storage Temperature and Media/Buffer for SARS-CoV-2 Nucleic Acid Detection. Am J Clin Pathol. 2021 Feb 4;155(2):280-285.

- Miller JM, Binnicker MJ, Campbell S, et al. A guide to utilization of the microbiology laboratory for diagnosis of infectious diseases: 2018 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Society for Microbiology. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67: e1-e94. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, 2020. Laboratory testing for coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in suspected human cases: interim guidance, 19 March 2020. World Health Organization. Accessed 6th April 2021.

- Dsa, O. C., Kadni, T. S., & N, S. (2023). From cold chain to ambient temperature: transport of viral specimens- a review. Annals of Medicine, 55(2). [CrossRef]

- Shaw KJ, Thain L, Docker PT, Dyer CE, Greenman J, Greenway GM, Haswell SJ. The use of carrier RNA to enhance DNA extraction from microfluidic-based silica monoliths. Anal Chim Acta. 2009 Oct 12;652(1-2):231-3. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).