Introduction

A subdural hematoma is a term used for an accumulation of blood in the subdural space, i.e., between the dura mater and the arachnoid membrane. Acute subdural hematoma (aSDH) is a life-threatening condition which develops rapidly, most often after a major traumatic event, and presents with significant neurological deterioration [

1]. On the other hand, chronic subdural hematoma (cSDH) develops over a longer timeframe (weeks), therefore the symptoms are usually present after a prolonged period [

2]. Patients suffering from cSDH present with a variety of signs and symptoms, some individuals are even asymptomatic [

2]. Clinical presentation is variable and includes headache, nausea, vomiting, instability, vertigo, aphasia, disorientation, hemiparesis or focal neurological deficit, and many others [

3]. It is not uncommon for patients to initially present with reduced Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) scores and altered consciousness, even to the degree of coma [

4]. After a comprehensive neurological examination, diagnosis is confirmed with non-contrast computed tomography (CT) of the brain as a gold standard, although in some cases magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) might be utilized [

5]. cSDH generally presents on the brain convexities and can be unilateral or bilateral. It is estimated that bilateral cSDH accounts for 9-22 % of all cSDH [

4,

6,

7,

8].

cSDH is among the most common neurosurgical entities affecting 1.72-20.6 patients per 100 000 individuals [

9]. It is projected that the incidence will rise in the near future due to the ageing population, as well as more frequent use of antithrombotic medications [

4]. Several studies have reported increased incidence in male patients, with at least two thirds of the patients with cSDH being men [

2,

4,

10]. The reported mean age of patients with cSDH varies considerably depending on the geographical region, ranging from 60 to 81 years of age [

6,

11]. Overall, cSDH is known for primarily affecting the elderly. In the majority of cases, patients can recall a minor head trauma that happened days to weeks prior to the diagnosis. The rise in traumatic events in recent years is also concerning [

12] and could exacerbate this issue. However, there is still a notable proportion of patients who did not experience any trauma to the head [

13,

14]. Although major progress has been made in understanding cSDH formation, its pathophysiology is still not fully elucidated. It is commonly believed that initial bleeding occurs due to tears of bridging veins [

15]. This can happen after a head injury, brain atrophy, intracranial hypotension or some other event [

2,

15]. Subsequently, subdural hemorrhage can trigger an inflammatory response which further supports the progression and enlargement of the subdural collection [

16].

The mainstay of treatment of cSDH is surgical evacuation of the hematoma or close observation with pharmacotherapy. Nonetheless, the controversies of the surgical approach still persist [

2]. Neurosurgical options include twist drill craniostomy (TDC), burr hole craniostomy (BHC), craniotomy (CO), endoscopic evacuation of the cSDH, and others [

17,

18]. Overall, BHC as a surgical approach is preferred in many departments [

19] but there is no consensus in neurosurgical community which approach should be advised. Despite the fact that the aforementioned surgical techniques are rather simple, patients who are surgically treated for cSDH can develop many complications [

20]. These can range from postoperative pneumocephalus, seizures, acute subdural and epidural hematoma, wound infections, up to lethal outcome [

21,

22]. Mortality of surgically treated patients for cSDH varies considerably—ranges from 0 to 32 % have been reported in the literature [

23,

24]. In addition, outcomes of these individuals are associated with their initial clinical status, comorbidities, as well as coagulation status [

21,

25,

26]. Consequently, less invasive approaches such as middle meningeal artery (MAA) embolization are being explored with promising results [

27]. Furthermore, pharmacological treatment for cSDH is also being studied—among pharmacological options, dexamethasone and atorvastatin have so far produced the best results for reducing recurrence and hematoma volume, respectively [

28]. More studies are much needed in this regard.

The primary aim of this multicenter study was to compare the overall outcomes during the hospitalization and the length of hospitalization of patients diagnosed with cSDH and surgically treated with either BHC or CO. As a secondary aim we examined quantities and qualities of postoperative complications between the two groups. Furthermore, we analyzed the general characteristics of these patients, their comorbidities, anticoagulant therapy administration, and initial presenting symptoms, as well as cSDH etiology and laterality of the hematoma.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

This multicenter prospective study was conducted at the Department of Neurosurgery, University Hospital Center Osijek, Croatia and Department of Neurosurgery, Clinical Center of Vojvodina, Novi Sad, Serbia. Patients included in the study were diagnosed with cSDH requiring neurosurgical intervention during the period starting with January 1st of 2017 until December 31st 2019 for both departments. During the study period, none of the neurosurgeons altered their surgical technique at either department. In total, there were 167 surgically treated patients, however due to missing data, 155 subjects were included in the final study population. All patient data was anonymized; therefore, no specific patient consent was obtained. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of University Hospital Center Osijek (R1-4012/2023, date of approval: 31st of May 2023).

Surgical Technique

Patients were surgically treated with either BHC or CO, depending on the neurosurgical preference and clinical experience. Surgeries were mostly performed in general anesthesia, except for some BHC approaches. Intraoperative subdural drain was routinely placed.

The BHC approach consisted of one or two burr holes which were planned with respect to CT scan findings. After the dural opening and incision of outer membrane, subdural hematoma was evacuated and generously irrigated through the burr-hole. A subdural drain was then inserted which utilized natural pressure gradient and was left in place depending on the drainage volume during the postoperative period.

The CO approach was planned depending on the area of maximal hematoma thickness, based on CT scan findings. CO flap was then raised, and the dura was opened in routine fashion. After the dural opening, the outer membrane was excised as much as the craniotomy permitted. The inner membrane was then opened and coagulated. Subdural space was generously irrigated, and subdural drain was inserted, which utilized natural pressure gradient and was left in place depending on the drainage volume during the postoperative period.

Selected Variables and Statistical Analysis

Relevant data for this study were obtained with clinical examinations, comprehensive patient interviews, and accompanying electric medical records at both departments. Selected variables for this study were age, sex, comorbidities, usage of anticoagulation therapy, presenting symptoms, cSDH etiology (traumatic or spontaneous), laterality of the hematoma (left-sided, right-sided, or bilateral), GCS at the admission and demission, days of stay (DoS), reoperation rate, complications, and mortality. Reoperation rate, complications, and mortality were recorded only during the hospitalization period, and were not followed afterwards. Duration of subdural drainage was not uniform for all patients. Therefore, it was excluded as a variable of interest.

Continuous variables were summarized as means and standard deviation and analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U-test. Categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and proportions and compared with χ² test or Fischer’s exact test when applicable. GCS score differences between the admission and discharge were evaluated with paired t-test. All p values were two-sided, and the threshold for statistical significance was set to p ≤ 0.05.

Results

Age and Sex Characteristics

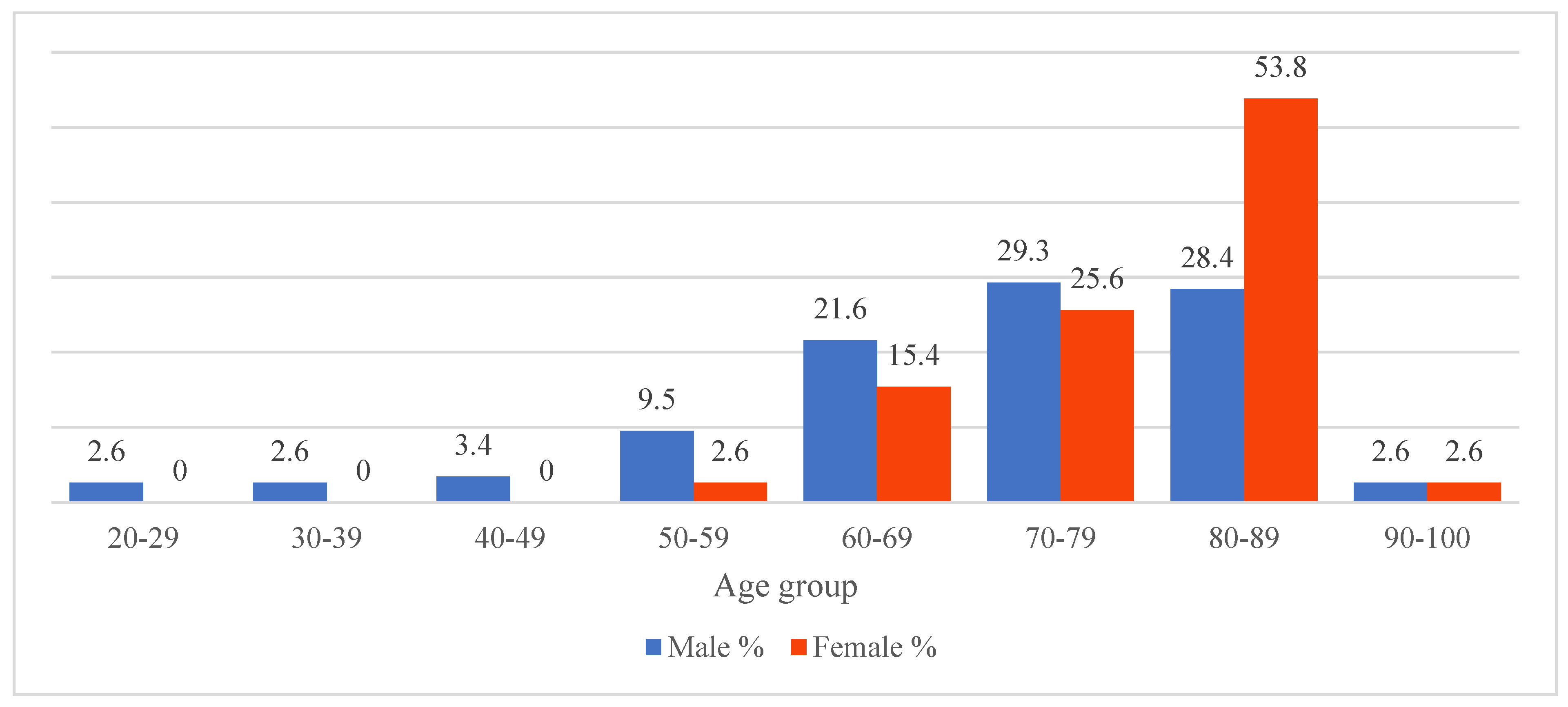

During the study period, there were a total of 155 patients diagnosed with cSDH who were surgically treated at either neurosurgical department. Of these, 124 (80 %) patients were treated with BHC and 31 (20 %) were treated with CO. The majority of patients were male (n = 122, 78.7 %) and the sex distribution between the two groups did not significantly differ. The mean age of patients in the BHC group was 72.2 years (range 22-92 years), whereas the average age of patients in the CO group was 72.8 years (range 46-91 years). This age difference was not statistically significant. Interestingly, more than half of all female patients were older than 80 years of age. Age distribution of all patients by sex is presented in

Figure 1.

Clinical Presentation and Comorbidities

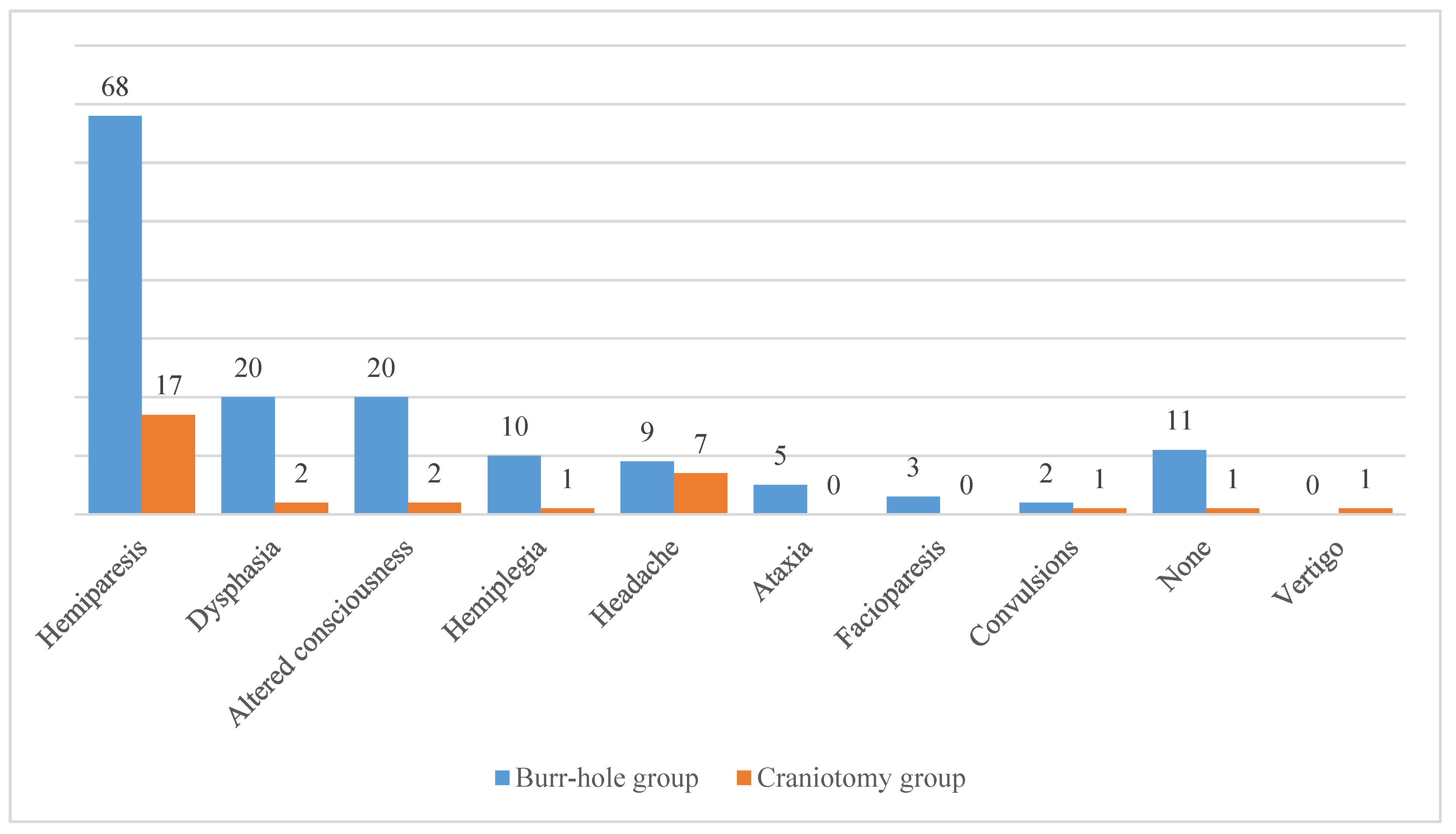

As previously stated, clinical signs and symptoms of patients with cSDH can vary significantly. Among the patients included in the BHC group the most common symptom was hemiparesis (n = 68, 54.8 %), which was followed by dysphasia (n = 20, 16.1 %) and altered consciousness (n = 20, 16.1 %). In addition, there were 11 patients (8.9 %) in the BHC group who did not present with any relevant symptom. Regarding the CO group, hemiparesis was also the leading symptom (n = 17, 54.8 %). It was followed by headache (n = 7, 22.6 %), dysphasia (n = 2, 6.5 %), and altered consciousness (n = 2, 6.5 %). There was only 1 patient (3.2 %) in the CO group who was asymptomatic. The comprehensive list of clinical signs and symptoms observed at the admission is presented in

Figure 2.

The most common comorbidity of our patients was cardiovascular disease (n = 100, 64.5 %), followed by diabetes (n = 25, 16.1 %). Furthermore, there were 11 patients (7.1 %) who suffered from chronic alcoholism. 37 patients (23.9 %) had no known comorbidities. The complete list of documented comorbidities is listed in

Table 1.

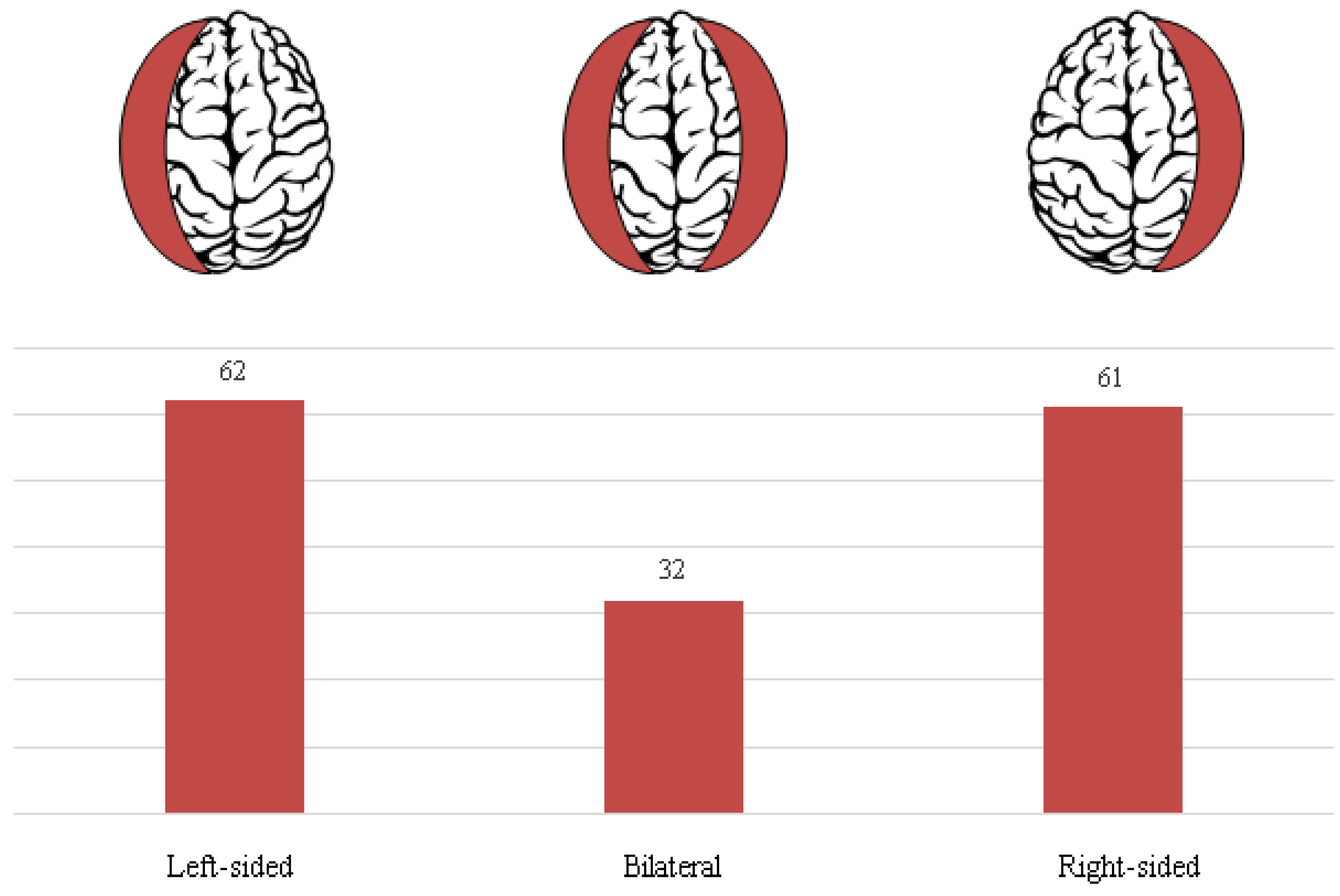

In our study population, traumatic head injury was confirmed in 92 patients (59.4 %). On the other hand, there were 63 patients (40.6 %) who were presented with a spontaneous cSDH onset. Based on the radiographic evaluation there were 62 left-sided (40.0 %), 61 were right-sided (39.4 %), and 32 were bilateral cSDH (20.6 %). Laterality of cSDH in our cohort is illustrated in

Figure 4.

Comparison of the Treatment Groups

As previously stated, there were 124 patients included in the BHC group and 31 in the CO group and the two groups did not significantly differ by age. Furthermore, there were 76 (61.3 %) cSDH of traumatic etiology in the BHC group, and 16 (51.6 %) in the CO group. This difference was not statistically significant. When analyzing the laterality of the hematoma, we did not detect any significance. In total, 37 (23.9 %) patients routinely administered some form of anticoagulation therapy, the ratio of these patients was not significantly different between the groups.

The mean GCS score at the admission for the BHC group was 13.5 ± 2.4, whereas for the CO group average GCS score was 14.4 ± 1.7. This difference between the two groups was statistically significant (U = 1452, p = 0.022). GCS score was also determined at the discharge—average GCS score was 13.7 ± 3.4 for BHC group and 12.6 ± 4.8 for CO group. There was a statistically significant decrease in GCS score at the discharge when compared to the GCS score at the admission for the CO group t(30) = 2.3, p = 0.031. On the other hand, this difference for the BHC group was not statistically significant.

Surgically treated patients in the CO group experienced significantly longer hospitalization compared to BHC group, 12.2 ± 7.1 days of stay vs 9.6 ± 7.9 days of stay (U = 1166, p < 0.001). During the hospitalization period, the number of complications, reoperation rate, and the mortalities did not significantly differ between the groups. Detailed characteristics of the two treatment groups are presented in

Table 2. Documented complications observed during the hospital stay are presented in

Table 3.

Discussion

Elderly and Male Predominance

In this study, we first examined the general characteristics of surgically treated patients diagnosed with cSDH at tertiary institutions in Croatia and Serbia. According to our results, the age group that is mostly affected by this disease are the elderly, as the mean age of our patients was 72.3 years which is in the range of previously published studies [

6,

11]. Furthermore, in our cohort we noted a male predominance, there was a total of 122 (78.7 %) male patients. This is also in line with the available literature [

7,

19,

29]. The reasoning behind the male bias is still debated [

30] but it could also be associated with male predominance for traumatic events [

12,

31]. As per

Figure 1, female patients affected by cSDH are generally older than male counterparts, although the exact reasoning is still not described which is discussed by Hotta et al. [

32].

As is the general case with the elderly [

33], patients in our cohort presented with a variety of comorbidities which are presented in

Table 1. The most common comorbidity in this study was cardiovascular disease, followed by diabetes and chronic alcoholism which was similar to other published research [

34]. Notably, there appears to be an association between pre-existing comorbidities and general outcomes, including the recurrence of cSDH [

35]. Furthermore, chronic alcoholism has been considered as a risk factor for developing cSDH [

20]. This can be both due to the head injuries related to alcohol intake [

2], as well as the so-called craniocerebral disproportion, i.e., brain atrophy due to chronic alcoholism [

36]. Less than a quarter of patients routinely took some form of anticoagulation therapy (

Table 2). Antithrombotic drugs usage has also been linked to increased risk of cSDH [

37]. Interestingly, compared to other published data [

38,

39], we had a relatively smaller proportion of patients who were routinely taking anticoagulants.

Regarding the initial clinical signs and symptoms, the most common was hemiparesis which was observed in more than half of all patients (

Figure 2). Indeed, limb weakness is considered as one of the most prominent symptoms of the cSDH [

40]. This is mostly mediated by the tension exerted by the hematoma on the motor cortex which is alleviated by surgical evacuation of the hematoma in a timely manner [

40]. Another common but non-specific symptom, i.e., headache which was observed in roughly 10 % of our patients, is generally a good prognostic factor [

3]. On the other hand, lower GCS scores at the admission are associated with poor outcomes [

41]. In our cohort, there were only 8 (5.2 %) patients with initial GCS score less than 9, and 17 (11 %) patients with GCS score between 9 and 12.

Craniotomy Is Associated with Worse Outcomes and Prolonged Hospitalization

In our study, a majority of patients underwent BHC and only a fifth of patients underwent CO. As the treatment options were not randomized, it shows a general surgical preference in our departments towards BHC over CO. Even though the initial GCS score and GCS score at the discharge did not differ much between the groups, the intra-group analysis revealed a significant clinical deterioration of patients in the CO group in terms of decreased GCS score (

Table 2). Similar findings were published by Ozevren et al. [

42]—patients who underwent BHC had better Glasgow outcome scale (GOS) score when compared to CO. Admittedly, the effect we observed of the CO treatment is relatively small, and a larger cohort of patients would be needed to better address this question. Even though the proportion of mortalities after CO in our study was notable (approximately every fifth patient died), this was not statistically significant (although it did approach significance level, p ≈ 0.06). The mortality in our study was comparable to rates reported by Tamura et al. [

20]. Interestingly, other studies did not find any significant differences regarding general outcomes between the two treatments, including mortalities [

29,

43,

44]. In addition, a systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by Huang et al. [

45] concluded that was not any significant difference in good outcomes and mortalities between these two treatment modalities. It should be noted that in this study we only followed patients during the hospital stay, and long-term outcomes were not accounted for. It would be of great interest to follow these patients over a prolonged period of time to get better insights into general outcomes. Another limitation of our study were other non-standardized variables, such as duration of subdural drainage, postoperative administration of dexamethasone and others which were decided by an individual neurosurgeon. Furthermore, the treatment-outcome discrepancies described in the literature could likely be due to some form of inherent neurosurgical bias: general preference of one surgical approach over the other, decision making based on preoperative imaging findings, health-status of a given patient etc. In order to gain more robust results, a non-randomized controlled trial would be of great value for this particular topic.

Additionally, patients in the CO group were on average hospitalized for a longer period of time than those who underwent BHC (

Table 2). This is in line with the findings of Sastry et al. [

46] and Mehta et al. [

47]. It seems that the prolonged hospitalization is mostly associated with preoperative frailty of these patients [

48]. It should be noted that we did not observe a difference in postoperative complications between the two groups (

Table 3), therefore the complications

per se were not the sole reason for an increase in days of stay for the CO group. Overall, the proportion of postoperative complications in our study was similar to previously published data [

49]. Interestingly, CO as an initial treatment option for cSDH generally produces more postoperative complications but is a recommended option for recurrent cSDH [

50]. Despite the fact that we did not include duration of surgery as a variable of interest, it is well accepted that the CO is more time consuming than BHC [

47]. Longer operation time with general anesthesia in frail patients disrupts the homeostasis of an individual and can contribute to prolonged hospitalization [

51]. The economic impact of the increase in hospitalization days also should not be overstated [

49].

During the hospitalization period, we did not observe a significantly different rate of reoperation between the two groups (

Table 2). However, a major limitation of our approach is confinement on a short postoperative period, hence we cannot draw conclusions regarding the recurrence rate of cSDH because it usually occurs after a longer follow-up period [

52]. Nonetheless, a systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by Almenawer et al. [

50] concluded that there was no difference in the recurrence rate between these treatment options.

Conclusions

Our study presents general characteristics and outcomes of surgically treated 155 patients diagnosed with cSDH at two tertiary institutions in Croatia and Serbia. Approximately one fifth of all patients presented with bilateral cSDH and the history of head trauma was documented in 59.4 % of all patients. Anticoagulant therapy was present in 37 (23.9 %) individuals. Majority of patients were elderly and of male sex. BHC was the treatment of choice in 124 (80 %) patients and 31 (20 %) patients underwent CO. The two groups did not significantly differ regarding age, but the patients in the CO group were presented with significantly higher GCS score at the admission to the hospital when compared to the BHC group. Notably, BHC produced better outcomes in terms of GCS score at the point of discharge from the hospital and was associated with reduced length of stay. Differences in complication, reoperation, and mortality rates were not statistically significant. Based on our study results, BHC produced better outcomes but further well-designed and well-controlled studies are warranted.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.K., D.D. and A.S.K.; methodology, N.K., V.K., T.R. and A.R.; software, T.T., S.Č., J.K. and M.P.; validation, N.K., T.I., V.F. and A.R.; formal analysis, N.K., S.Š. and A.R.; investigation, A.S.K., V.K. and A.R.; resources, N.K. and D.D.; data curation, T.R. and T.T.; writing—original draft preparation, A.R.; writing—review and editing, N.K., D.D., A.S.K., V.K., T.R., T.T., S.Č., J.K., M.P., T.I., V.F., S.Š. and A.R.; visualization, A.R.; supervision, N.K., D.D. and A.S.K.; project administration, N.K., D.D. and A.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of University Hospital Center Osijek (R1-4012/2023, date of approval: 31st of May 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

All patient data was anonymized; therefore, informed consent was not obtained from subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wilberger, J.E.; Harris, M.; Diamond, D.L. Acute subdural hematoma: Morbidity, mortality, and operative timing. Journal of Neurosurgery 1991, 74, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nouri, A.; Gondar, R.; Schaller, K.; Meling, T. Chronic Subdural Hematoma (cSDH): A review of the current state of the art. Brain and Spine 2021, 1, 100300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blaauw, J.; Meelis, G.A.; Jacobs, B.; van der Gaag, N.A.; Jellema, K.; Kho, K.H.; Groen, R.J.M.; van der Naalt, J.; Lingsma, H.F.; den Hertog, H.M. Presenting symptoms and functional outcome of chronic subdural hematoma patients. 2022, 145, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauhala, M.; Luoto, T.M.; Huhtala, H.; Iverson, G.L.; Niskakangas, T.; Öhman, J.; Helén, P. The incidence of chronic subdural hematomas from 1990 to 2015 in a defined Finnish population. Journal of neurosurgery 2019, 132, 1147–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miah, I.P.; Tank, Y.; Rosendaal, F.R.; Peul, W.C.; Dammers, R.; Lingsma, H.F.; den Hertog, H.M.; Jellema, K.; van der Gaag, N.A.; on behalf of the Dutch Chronic Subdural Hematoma Research Group. Radiological prognostic factors of chronic subdural hematoma recurrence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroradiology 2021, 63, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayil, K.; Ramzan, A.; Sajad, A.; Zahoor, S.; Wani, A.; Nizami, F.; Laharwal, M.; Kirmani, A.; Bhat, R. Subdural hematomas: An analysis of 1181 Kashmiri patients. World Neurosurg 2012, 77, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, E.B.; Brandão, L.F.; Tavares, C.B.; Borges, I.B.; Neto, N.G.; Kessler, I.M. Epidemiological characteristics of 778 patients who underwent surgical drainage of chronic subdural hematomas in Brasília, Brazil. BMC surgery 2013, 13, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellani, R.J.; Mojica-Sanchez, G.; Schwartzbauer, G.; Hersh, D.S. Symptomatic Acute-on-Chronic Subdural Hematoma: A Clinicopathological Study. The American journal of forensic medicine and pathology 2017, 38, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Huang, J. Chronic Subdural Hematoma: Epidemiology and Natural History. Neurosurgery clinics of North America 2017, 28, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toi, H.; Kinoshita, K.; Hirai, S.; Takai, H.; Hara, K.; Matsushita, N.; Matsubara, S.; Otani, M.; Muramatsu, K.; Matsuda, S.; et al. Present epidemiology of chronic subdural hematoma in Japan: Analysis of 63,358 cases recorded in a national administrative database. Journal of neurosurgery 2018, 128, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhiyaman, V.; Chattopadhyay, I.; Irshad, F.; Curran, D.; Abraham, S. Increasing incidence of chronic subdural haematoma in the elderly. QJM: Monthly journal of the Association of Physicians 2017, 110, 375–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koruga, N.; Soldo Koruga, A.; Rončević, R.; Turk, T.; Kopačin, V.; Kretić, D.; Rotim, T.; Rončević, A. Telemedicine in Neurosurgical Trauma during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Single-Center Experience. 2022, 12, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stroobandt, G.; Fransen, P.; Thauvoy, C.; Menard, E. Pathogenetic factors in chronic subdural haematoma and causes of recurrence after drainage. Acta neurochirurgica 1995, 137, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindvall, P.; Koskinen, L.-O.D. Anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents and the risk of development and recurrence of chronic subdural haematomas. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience 2009, 16, 1287–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, R. Youmans and Winn Neurological Surgery. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Edlmann, E.; Giorgi-Coll, S.; Whitfield, P.C.; Carpenter, K.L.H.; Hutchinson, P.J. Pathophysiology of chronic subdural haematoma: Inflammation, angiogenesis and implications for pharmacotherapy. Journal of neuroinflammation 2017, 14, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solou, M.; Ydreos, I.; Gavra, M.; Papadopoulos, E.K.; Banos, S.; Boviatsis, E.J.; Savvanis, G.; Stavrinou, L.C. Controversies in the Surgical Treatment of Chronic Subdural Hematoma: A Systematic Scoping Review. 2022, 12, 2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rončević, A.; Splavski, B.; Mužević, D.; Vekić Mužević, M.; Blagus, G.J.; et al. High-speed drill craniostomy as a minimally invasive method of chronic subdural hematoma management. Preliminary results of a pilot study. Journal of Applied Health Sciences 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feghali, J.; Yang, W.; Huang, J. Updates in Chronic Subdural Hematoma: Epidemiology, Etiology, Pathogenesis, Treatment, and Outcome. World Neurosurgery 2020, 141, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, R.; Sato, M.; Yoshida, K.; Toda, M. History and current progress of chronic subdural hematoma. Journal of the neurological sciences 2021, 429, 118066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, K.; Maeda, M. Surgical treatment of chronic subdural hematoma in 500 consecutive cases: Clinical characteristics, surgical outcome, complications, and recurrence rate. Neurologia medico-chirurgica 2001, 41, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, T.H.; Park, Y.K.; Lim, D.J.; Cho, T.H.; Chung, Y.G.; Chung, H.S.; Suh, J.K. Chronic subdural hematoma: Evaluation of the clinical significance of postoperative drainage volume. Journal of neurosurgery 2000, 93, 796–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posti, J.P.; Luoto, T.M.; Sipilä, J.O.T.; Rautava, P.; Kytö, V. Prognosis of patients with operated chronic subdural hematoma. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 7020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, V.; Harward, S.C.; Sankey, E.W.; Nayar, G.; Codd, P.J. Evidence based diagnosis and management of chronic subdural hematoma: A review of the literature. Journal of clinical neuroscience: Official journal of the Neurosurgical Society of Australasia 2018, 50, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Havenbergh, T.; van Calenbergh, F.; Goffin, J.; Plets, C. Outcome of chronic subdural haematoma: Analysis of prognostic factors. British journal of neurosurgery 1996, 10, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramachandran, R.; Hegde, T. Chronic subdural hematomas--causes of morbidity and mortality. Surgical neurology 2007, 67, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudy, R.F.; Catapano, J.S.; Jadhav, A.P.; Albuquerque, F.C.; Ducruet, A.F. Middle Meningeal Artery Embolization to Treat Chronic Subdural Hematoma. 2023, 3, e000490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Song, J.; He, Q.; You, C. Pharmacological Treatment in the Management of Chronic Subdural Hematoma. Frontiers in aging neuroscience 2021, 13, 684501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolfaghari, S.; Bartek, J.; Strom, I.; Djärf, F.; Wong, S.-S.; Ståhl, N.; Jakola, A.S.; Nittby Redebrandt, H. Burr hole craniostomy versus minicraniotomy in chronic subdural hematoma: A comparative cohort study. Acta neurochirurgica 2021, 163, 3217–3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshman, L.A.G.; Manickam, A.; Carter, D. Risk factors for chronic subdural haematoma formation do not account for the established male bias. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery 2015, 131, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, R.; Shen, J. Gender-Specific Differences in Chronic Subdural Hematoma. The Journal of craniofacial surgery 2023, 34, e124–e128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotta, K.; Sorimachi, T.; Honda, Y.; Matsumae, M. Chronic Subdural Hematoma in Women. World Neurosurgery 2017, 105, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Z.Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, C.H.; Yin, R.Y.; Tang, L.; Zhang, F. Prevalence and Patterns of Comorbidity Among Middle-Aged and Elderly People in China: A Cross-Sectional Study Based on CHARLS Data. International journal of general medicine 2021, 14, 1449–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Perez, R.; Tsimpas, A.; Rayo, N.; Cepeda, S.; Lagares, A. Role of the patient comorbidity in the recurrence of chronic subdural hematomas. Neurosurgical Review 2021, 44, 971–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atsumi, H.; Sorimachi, T.; Honda, Y.; Sunaga, A.; Matsumae, M. Effects of Pre-Existing Comorbidities on Outcomes in Patients with Chronic Subdural Hematoma. World Neurosurg 2019, 122, e924–e932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alderazi, Y.; Brett, F. Alcohol and the nervous system. Current Diagnostic Pathology 2007, 13, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamou, H.A.; Clusmann, H.; Schulz, J.B.; Wiesmann, M.; Altiok, E.; Höllig, A. Chronic Subdural Hematoma. Deutsches Arzteblatt international 2022, 119, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspegren, O.P.; Åstrand, R.; Lundgren, M.I.; Romner, B. Anticoagulation therapy a risk factor for the development of chronic subdural hematoma. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery 2013, 115, 981–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rust, T.; Kiemer, N.; Erasmus, A. Chronic subdural haematomas and anticoagulation or anti-thrombotic therapy. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience 2006, 13, 823–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomita, Y.; Yamada, S.M.; Yamada, S.; Matsuno, A. Subdural Tension on the Brain in Patients with Chronic Subdural Hematoma Is Related to Hemiparesis but Not to Headache or Recurrence. World Neurosurg 2018, 119, e518–e526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Vargas, P.M.; Thenier-Villa, J.L.; Calero Félix, L.; Galárraga Campoverde, R.A.; Martín-Gallego, Á.; de la Lama Zaragoza, A.; Conde Alonso, C.M. Factors that negatively influence the Glasgow Outcome Scale in patients with chronic subdural hematomas. An analytical and retrospective study in a tertiary center. Interdisciplinary Neurosurgery 2020, 20, 100606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozevren, H.; Cetin, A.; Hattapoglu, S.; Baloglu, M. Burr Hole and Craniotomy in the Treatment of Subdural Hematoma: A Comparative Study. 2022, 25, 1056–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, A.; Smith, G.; Onyewadume, L.; Peck, M.R.; Herring, E.; Pace, J.; Rogers, M.; Momotaz, H.; Hoffer, S.A.; Hu, Y.; et al. Morbidity and Mortality After Burr Hole Craniostomy Versus Craniotomy for Chronic Subdural Hematoma Evacuation: A Single-Center Experience. World Neurosurgery 2020, 134, e196–e203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vemula, R.C.; Prasad, B.C.M.; Koyalmantham, V.; Kumar, K. Trephine Craniotomy versus Burr Hole Drainage for Chronic Subdural Hematoma—An Institutional Analysis of 156 Patients. Indian Journal of Neurotrauma 2020, 17, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.W.; Yin, X.S.; Li, Z.P. Burr hole craniostomy vs. minicraniotomy of chronic subdural hematoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European review for medical and pharmacological sciences 2022, 26, 4983–4990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sastry, R.A.; Pertsch, N.; Tang, O.; Shao, B.; Toms, S.A.; Weil, R.J. Frailty and Outcomes after Craniotomy or Craniectomy for Atraumatic Chronic Subdural Hematoma. World Neurosurgery 2021, 145, e242–e251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, V.; Harward, S.C.; Sankey, E.W.; Nayar, G.; Codd, P.J. Evidence based diagnosis and management of chronic subdural hematoma: A review of the literature. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience 2018, 50, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleman, J.; Taussky, P.; Fandino, J.; Muroi, C. Evidence-based treatment of chronic subdural hematoma. Traumatic Brain Injury 2014, 249–281. [Google Scholar]

- Rauhala, M.; Helén, P.; Huhtala, H.; Heikkilä, P.; Iverson, G.L.; Niskakangas, T.; Öhman, J.; Luoto, T.M. Chronic subdural hematoma—Incidence, complications, and financial impact. Acta neurochirurgica 2020, 162, 2033–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almenawer, S.A.; Farrokhyar, F.; Hong, C.; Alhazzani, W.; Manoranjan, B.; Yarascavitch, B.; Arjmand, P.; Baronia, B.; Reddy, K.; Murty, N. Chronic Subdural Hematoma Management: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of 34829 Patients. 2014, 259, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Rismany, J.; Gidicsin, C.; Bergese, S.D. Frailty: The perioperative and anesthesia challenges of an emerging pandemic. Journal of Anesthesia 2023, 37, 624–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen-Ranberg, N.C.; Debrabant, B.; Poulsen, F.R.; Bergholt, B.; Hundsholt, T.; Fugleholm, K. The Danish chronic subdural hematoma study—Predicting recurrence of chronic subdural hematoma. Acta neurochirurgica 2019, 161, 885–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).