Introduction

Madagascar has an exceptionally high level of endemism (ca. 90% at the species level; Phillipson et al., 2006) resulting from over 100 million years of evolution in tectonic isolation. Situated almost entirely within the tropics, the island is widely recognized as one of the eight major biodiversity hotspots and as a global conservation priority (Myers et al., 2000). The diversification of this biota has been driven in part by a wide range of climates and varied topography, and is reflected in vegetation ranging from perhumid forests to dry spiny dry bush land (Hannah et al., 2008), all of which are threatened by human activities.

Forest cover decreased by almost 40% between 1950 and 2000 (Harper et al., 2007), and today primary vegetation covers less than 10% of the land area and is highly fragmented in most parts of the island. The main causes of deforestation are firstly the practice of swidden agriculture, and unsustainable exploitation for charcoal production, firewood and timber extraction (Casse et al., 2004).

Contemporary global environmental changes, largely the result of human activities, include climate change and habitat fragmentation (Vitousek, 1994; Willis et al., 2008). Their combined actions are major threats to biodiversity and their consequences are potentially disastrous (Travis, 2003). Tropical forests, which contain a significant portion of global biodiversity, are cleared in rural areas for farming, industry or mining (Aide et al., 2000). Habitat destruction resulting from deforestation threatens the survival of species and reduces biodiversity. This process also creates forest fragments that are often too small to maintain viable populations, and it increases edge effects at the interface between intact and cleared habitat (Aide et al., 2000; Köhler et al., 2003; Urech et al., 2011). Fragmentation also impedes the dispersal of species (Andreone, 1994) and therefore reduces their potential for adaptation to future climate change (Travis, 2003; Hannah et al., 2008; Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2008).

Malagasy frogs constitute one of the world’s richest groups of amphibians with about 300 species in late of 2015, but another 200 still wait to be formally described (Andreone et al. 2016). Non-marine reptiles also show high diversity (363 species) and endemism (92%) (Glaw and Vences, 2007; Vieites et al., 2009). Habitat destruction and fragmentation are the most important factors influencing extinction (Andreone et al., 2005a). Species diversity of rainforest herpetofauna generally responds negatively to fragmentation (decreasing diversity with decreasing fragment size; Ramanamanjato, 2000; Vallan, 2000), forming nested subsets in fragments. Herpetological diversity decreases in highly disturbed areas, e.g. where intense clearing and burning have produced degraded secondary forest, forest mosaic, or plantations (Glos et al., 2008b; Jenkins et al., 2003; Scott et al., 2006; Vallan, 2002; Vallan et al., 2004). However, when disturbances were low-level, and/or sufficiently long ago, no clear effect on diversity was found in rainforest amphibian (Vallan et al., 2004) and dry forest reptile communities (Penner, 2005). But again, species typical of pristine rainforest were replaced by species adapted to secondary habitats (Vallan et al., 2004).

Within the reptiles, studies of disturbance sensitivity are inconsistent. Tortoises are generally susceptible to disturbance (e.g., Pyxis planicauda, Bloxam et al., 1996; Young et al., 2008), however, this threat is outweighed by overexploitation and collecting (Leuteritz et al., 2005). Many chameleon species are true forest dwellers and habitat disturbance has negative effects on diversity and abundance (e.g., Brookesia; Brady and Griffiths, 1999; Jenkins et al., 2003), though this is not true for all chameleons (e.g., Furcifer pardalis; Andreone et al., 2005b). In dry forest, species higher in the food chain (e.g. snakes) decrease in presence and abundance in disturbed habitats (Glos et al., unpublished).

In amphibians, species that reproduce independently from running or standing waters are most vulnerable (i.e., microhylid frogs, some mantellid frogs; Vallan, 2000, 2002). Furthermore, species with narrow spatial and temporal niches are sensitive to microhabitat changes associated with disturbance (e.g., Aglyptodactylus laticeps, Glos et al., 2008a, 2008c).

It might seem paradoxical to appeal for intensive conservation where catastrophic declines have not yet been detected. Amphibian conservation efforts have the possibility of being pro-active, rather than reactive (Andreone et al., 2008). Efforts should focus on areas of high herpetological species richness, or areas of otherwise high conservation interest such as riverbeds and adjacent gallery forests (Jenkins et al., 2003; Paquette et al., 2007), montane areas (Raxworthy et al., 2008; Vences et al., 2002) and dry forest (Glos, 2003; Glos et al., 2008b). Although several surveys have been conducted but there are few studies show the effect of the vegetation structure change on amphibians and reptiles community.

One of the key elements in conservation efforts involves re-establishing connectivity between forest fragments and increasing their cover in order to improve landscape resilience. This could be accomplished in part by expanding the current protected areas network to ensure full inclusion of biodiversity and to mitigate against further disturbance (Aide et al., 2000; Lamb et al., 2005). Depending on the nature and degree of degradation, the process of secondary succession could offer an effective strategy for restoration of tropical forests (Aide et al., 2000). Forest patches that still contain moderate levels of biodiversity and a combination of residual trees, an abundant seed bank, and adequate biotic and abiotic conditions could facilitate re-colonization (Lamb et al., 2005). However, this process is often impeded because the landscape is overly fragmented and there are too many barriers to species dispersal and establishment (Zimmerman et al., 2000) for natural regeneration to take place fast enough to address conservation issues. Changes in land use have also resulted in an increase in abandoned cleared lands, which present another opportunity for ecological restoration (Anderson, 1995; Aide et al., 2000). These areas can play an important role for conservation (Dobson et al., 1997; Young, 2000) by contributing to the reconnection of isolated patches of habitat and the creation of corridors and stepping stones, thus facilitating the dispersal of plant and animal species (Anderson, 1995).

In this study we compare the herpetofauna’s community between five types of land uses such as closed canopy forest with others stage of natural regeneration (fallows succession), degraded land and restoration plots.

The questions addressed include (1) how does the herpetofauna community (species richness and composition) respond to land uses change? (2) How does population abundance differ between these habitats types?

Materials and Methods

Study Area

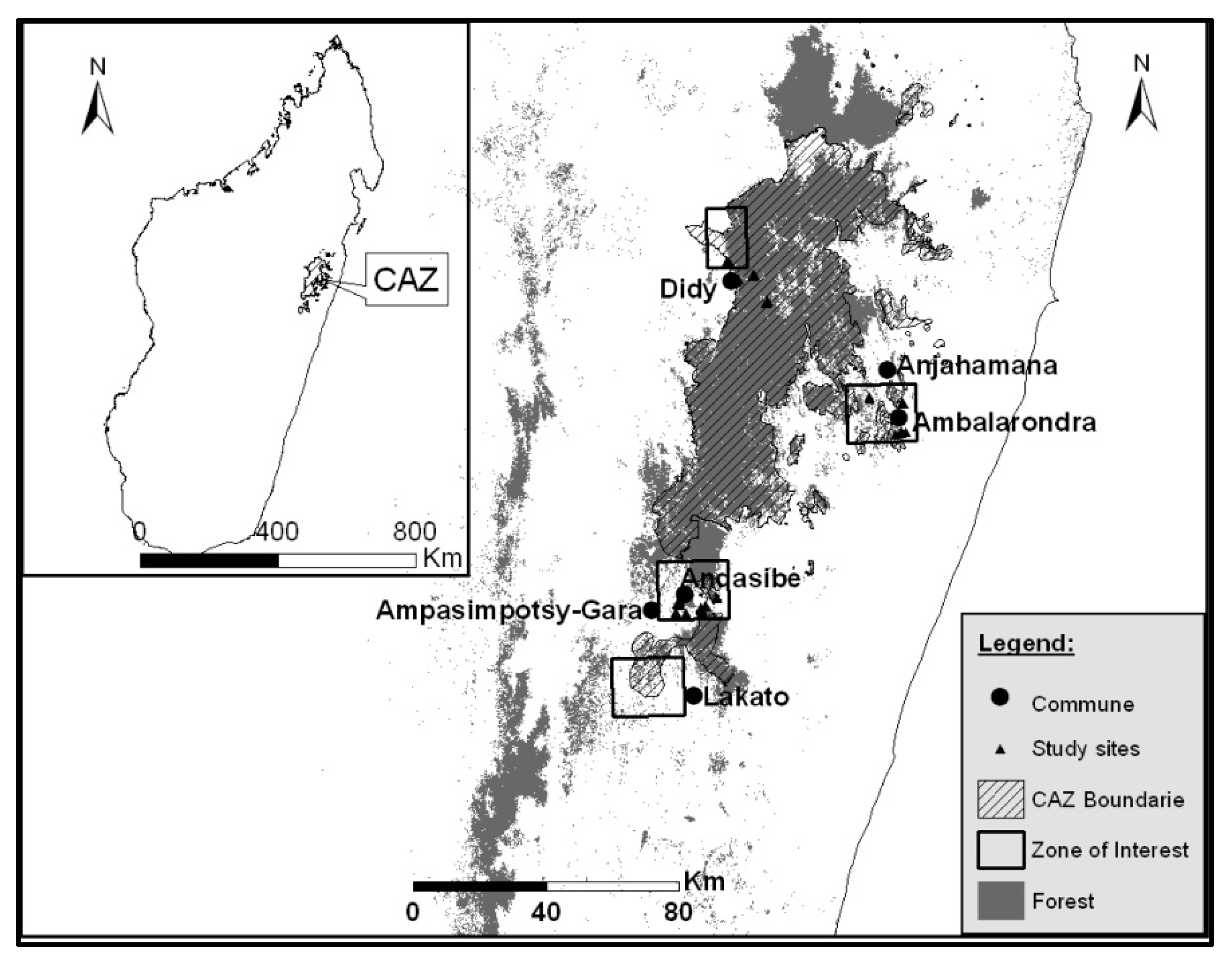

This study was performed in the largest remaining contiguous rainforest of the Ankeniheny-Zahamena Corridor (CAZ), located along the eastern region of Madagascar.

With an annual average temperatures of 21.5 and 20.4 C and a mean annual rainfall between 2550 mm (at 550 m a.s.l.) and 3450 mm (at 750 m a.s.l.) (Styger et al. 2007), tropical rainforest dominates the vegetation of the region. Different habitat types exist within the 505,734 ha of the corridor, over an elevation range of 400-1,500 m along, such as: coastal/littoral zones, marshes, and low, mid, and high-elevation forests. Mid-elevation humid forest is most frequently observed at a high between 550-1500m of the corridor. At a high less than 550m, a few remaining remnants of low elevation humid forest can be found on the eastern side of the corridor, where most of agricultural lands were established. This spectrum of habitat types yields an interesting mix of animals and plants. The Tavy or traditional slash-and-burn agriculture of the Betsimisaraka people characterized the study, and leads to the most forest cover loss and soil degradation of the eastern region. The soils, Inceptisols and Ultisolstypes (US Soil Taxonomy), are characterised by a high acidity (pH=3.5–5.0), an aluminum saturation between 60% and 90%, an extremely low nutrients on phosphorus in surface and subsoils, (Johnson, 1992; Brand and Rakotondranaly, 1997).

Three zone of interest (ZOI), including 44 sites from five land uses (10 closed canopy forest “CC”, 08 tree fallow “TF”, 11 shrub fallow “SF”, 10 degraded land “DL” and 05 reforestation “RF”) were sampled (

Figure 1).

Habitat Classification

- Closed Canopy Forest (CC)

Closed canopy forest is composed by the evergreen humid forest at low altitude (0–800 m) and mid altitude (800–1800 m) described in. In the low altitude, vegetation is constituted by three stratums: upper, middle and lower (Faramalala, 1988). Canopy is formed by the upper stratum and tree height is between 25-30 m which can be surmounted by some emerging trees to 30-40 m. The evergreen humid forest at low altitude has thick litter always humid and dense undergrowth (Faramalala, 1988). The original vegetation in the middle-altitude is characterized by a canopy layer in one stratum (Koechlin, 1972), with lower tree height (20–25 m) and species diversity than in lowland formations. The dominant tree genera are Tambourisa, Weinmannia, Symphonia, Dalbergia and Vernonia.

- Tree Fallow (TF)

In eastern Madagascar, tree fallow combines two land uses namely “Vaditakana” and “Savoka mody” in Styger et al. (2007). Vaditakana is the first fallow after deforestation (either primary forest or secondary forest) and follow the first rice crop (Styger et al. 2007). Savoka mody is the regenerated tree fallow after restoration of shrub fallow. The pioneer tree Trema orientalis sp. (Ulmaceae) is able to colonize and dominate only the first fallow cycle after deforestation (Styger and Fernandes, 2006). It is sometimes associated with Harungana madagascariensis (Clusiaceae) and the shrub Solanum mauritianum (Solanaceae) which has a rapid initial growth but dies back after 6-12 months giving way to Trema (Styger et al. 2007). On the other hand, Psiadia altissima (Asteraceae) dominates the first cycle if Trema and Harungana are absent.

- Shrub Fallow (SF)

Shrub fallow is the second fallow cycle after initial deforestation (Styger et al. 2007). It combines, after succession of slash and burn agriculture, three stage of regeneration which is Ramarasana, Dedeka and Savoka (Styger et al. 2007). Ramarasana is the initial fallow stage that starts from the moment when the rice panicles are manually harvested one by one until the left-behind standing rice straw is overgrown by the fallow and not visible anymore (Styger et al. 2007). This can take between 6 months and 2 years depending on location and soils. Species composition is characterised by herbaceous weed. After the disappearance of the rice straw, the fallow turns into a Dedeka. A Dedeka is an immature shrub fallow that is small in height (1–1.5 m). There, woody species progressively replace the herbaceous species present in the Ramarasana stage. The Dedeka stage takes longer more than 10 years (Styger et al. 2007). As soil degradation advances, Dedeka develops into a Savoka. Then, a Savoka is also a shrubby fallow but taller in height (2–4 m). The shrubby species are essentially the same as in the Dedeka. The second fallow cycle is most often dominated by the indigenous shrub species Psiadia altissima (Asteraceae). However, this species is in turn quickly outcompeted in subsequent fallows by Rubus moluccanus (Rosaceae) and/or Lantana camara (Verbenaceae), two exotic invasive species (Styger and Fernandes, 2006). Rubus is the most aggressive among all the shrubby fallow species and quickly forms a thick stand.

- Degraded Land (DL)

Continuation of high frequency of land use, degraded land occurs after the third and fourth Tavy cycle (Styger et al. 2007). Species composition is dominated by herbaceous plants, forbs, and grasses. In eastern Madagascar, Imperata cylindrica (Poaceae) and the ferns Pteridium aquilinum (Dennstaedtiaceae) and Sticherus flagellaris (Gleicheniaceae) replace Rubus as soil fertility levels decline through successive cycles of cropping and fallow (Styger and Fernandes, 2006).These species become dominant beyond the fifth cycle of slash and burn practice. A perennial herbaceous species, Aframomum angustifolium (Zingiberaceae) is another important fallow species but covers less ground (Styger et al. 2007). Associated species that hardly form single stands are Clidemia hirta (Melastomataceae) and Tristem mavirusanum (Melastomataceae). Land management, relief; soil fertility status and seed sources determine how quickly ferns and Imperata become the principal species (Styger et al. 2007). The ferns usually appear earlier in the succession than Imperata. In many cases, Imperata gradually replaces ferns within a sequence. In the last succession phase, grasslands replace ferns and Imperata. In tropical Asia, I. cylindrica is the most widespread and aggressive species (Garrity et al., 1996; Grist and Menz, 1997). Contrary to what is found in eastern Madagascar, I. cylindrical is not a persistent fire-climax species and does not represent the last stage in succession (Styger and Fernandes, 2006). Beyond the 6th cycle and after repeated burning it is replaced by a few grass species composed of Aristida similes, Aristida sp., Hyparrhenia rufa, Paspalum conjugatum, Paniicum brevifolium, and Pennisetum sp., among others (Dandoy, 1973; Pfund, 2000). Once herbaceous fallows are established, farmers cease upland rice cultivation and may plant root crops for one or two more seasons before the land is completely abandoned.

- Reforestation Plots

The reforestation plot is the planted tree fallows when fallow periods are longer than 5 years and when additional products such as wood or fruits can be produced as an added benefit of the short-fallow restoration. Reforestation is crucial in areas where connectivity has been interrupted. Reconnecting these areas is essential in order to permit animal movements and genetic exchange between populations. The corridors are important to assure viable populations of many endemic and endangered species. Reforestation plots were done in several currently isolated forests and protected areas in the Andasibe region, eastern Madagascar. Small rainforest fragments are being linked up by the planting of corridors. Most of trees are planted during the TAMS project (Tetik’Asa Mampody Savoka) since 2008. The project assists people in securing land tenure, in addressing livelihood issues, basically improving and diversifying agriculture. There are agroforestry plots being created in the buffer zones to the reforestation areas. Vegetation in these areas is composed by endemic species of rainforest trees and autochthon species such as Rhodoleana leroyana and “Lalona” with some secondary vegetation species such as Trema, Harungana and Psiadia.

Field Methods

Field work for this study was conducted in 2014 and 2015 during the rainy season and when herpetofaunal activity is at its highest (Raxworthy et al 1998; Nussbaum et al 1999; Raselimanana et al. 2000). Three standard techniques were used to sample amphibians and reptiles: pitfall trapping with drifts fences, opportunistic day and night searching, and refuge examination.

- Pitfall Traps

100m long pitfall trap lines of 11 buckets spaced at 10m intervals were used. The buckets were 275 mm deep, 290 mm to internal diameter, 220 mm bottom internal diameter, with the handles removed and small holes punched in the bottom to allow water drainage (Raxworthy et al. 1998; Nussbaum et al. 1999; Raselimanana et al. 2000; Andreone et al. 2000, 2001a, 2003; Ramanamanjato & Rabibisoa 2002; Rakotomalala & Raselimanana 2003; Raselimanana 2004; Rakotondravony 2006a, 2006b, 2007; Raselimanana & Andriamampionona 2007; D’Cruze et al. 2007). The buckets were sunk into the ground along a drift fence made from plastic sheeting (0.5m high) stapled to thin wooden stakes. The fence bottom was buried 50 mm deep into the ground using leaf litter. The drift fence (100 m in length) was positioned to run across the middle of each bucket. A bucket was placed at both ends of the drift fence, with nine additional buckets positioned along the drift fence at 10 m intervals. The trap lines were checked early in the morning and late afternoon, and captured animals (amphibian, reptiles and mammals) were brought to the camp site for identification, photography, morphometric measurements and tissue samples. One pitfall traps line (parallel to the slope) was used at each survey site. Whenever possible we sampled all target habitats (closed canopy, reforestation, tree fallow, shrub fallow and degraded land) around one camp site, and sampled as many as logistically possible (usually two or three habitats) at the same time to reduce the effect of variation in weather and season on the sampling.

- Opportunistic Day and Night Searching

Animals were sampled during the day and night, along 4 transects lines which are installed perpendicularly to the line of pitfall traps. Each transect line measures 50m and the distance between them was 20m. Transects lines were established 5m from the pitfall traps to avoid disturbance caused by traps survey. These lines were installed 24 hours before survey to minimize disturbance (Jenkins et al. 1999, 2003; Randrianantoandro et al. 2007, 2010a, 2010b) to the animals. One day of the survey is composed by one diurnal and one nocturnal search. In the main plot, transects were surveyed twice (with two diurnal and two nocturnal) but the two days of survey should be spaced at least by one day to avoid disturbance. Survey team was composed by three people with two experts on herpetofauna survey and one guide. Observers moved slowly along each line which one expert in charge of observing the animal in the left side and the others is responsible for searching in the right side. The third person (guide) was in charge of catching observed animals and taking care of them during the observation. Nocturnal survey was done using headlamp (Petzl MYO RXP) with a capacity of 10m but this distance changed depending vegetation density. The following information was recorded for each observed individual: time of observation, roosting (perch) height and the maximum height of the plant, roost type (e.g. twig, leaf) and state (dead or alive), types of the habitat (closed canopy, tree fallow, shrub fallow, degraded land, reforestation) and/or microhabitat (Tree, ground), and geographic coordinates. Each individual was placed in a clothing (for reptiles) or plastic (for amphibians) bag; brought to the camp for final identification and morphometric measurements the day after the nocturnal but the same day of the diurnal search before releasing the animal in their original habitat. Snout-vent and tail length were measured using dual calipers; however the body mass was taken using pesola with 0.01 of precision. In addition, sex and age were also identified. Photos and tissue samples (fingertip, or tip of tail, and/or buccal swab) were taken for all captured animals for final verification and genetic analysis later.

Parameters such as temperature, humidity, wind speed using kestrel material were recorded for at the start and end point of each transect during the survey to determine the general characteristics of transect. Voucher specimens were fixed and later transferred to alcohol. Collected material was deposited in research collection: the museum of the Department of Animal Biology, University of Antananarivo (UABDA).

- Refuge Examination

Microhabitats likely to be a refuge were examined: tree hole, under and in fallen logs and rotten tree stumps; under bark; under rocks; in leaf litter, root-mats, and soil; and in leaf axils of Pandanus screw palms and Ravenala traveller’s palm.

- Chameleon Surveys

During this study we conducted chameleons survey separately to others herpetofauna species. For this group, we used line transect on distance sampling method (see Andriantsimanarilafy et al. in prep for details). Madagascar is home of more than half of chameleon in the world with his 85 described species. This taxon is widely distributed in the island and occupies many types of habitat (Glaw & Vences, 2007).

Data Analysis

Relative abundance (RA), or the frequency of observation of each species for the same sampling effort, is calculated with the formula: , where ni: number of individuals of one species, N: total number of observed species. Each species will be classify as: very rare; rare; influential and abundant according classification made by Jolly in 1965 :

RA < 1 % : Very rare species (Vrs)

RA = [1-5 % [: Rare species (Rs)

RA = [5-15 % [: Influential species (Is)

RA ≥ 15 %: Abundant species (As)

The Shannon weaver index H’ is calculated by the formula:, (where ni: number of individuals of one species, N: total number of observed species) to qualify specific diversity.

The values of evenness E allow to evaluate equilibrium of a population in one site and identify the existence or not of dominant species that masks others with low numbers. It is the distribution analysis of individuals’ homogeneity that live in community. Evenness is calculated with the formula: , where H’: diversity index, S: total number of species. An ecosystem is considered in equilibrium if E is close to 1, and individuals’ distribution is homogeneous.

To analyse relationships between the habitat types (land uses) and species richness / relative abundance, we ran a Poisson distributed generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) in R 2.15.2 (R Development Core Team, 2012) using the packages: glmmADMB and Car (Bates et al., 2013). The dependent variables (richness and abundance) were analysed at the transect level, and survey site, and were included as random effects.

Results

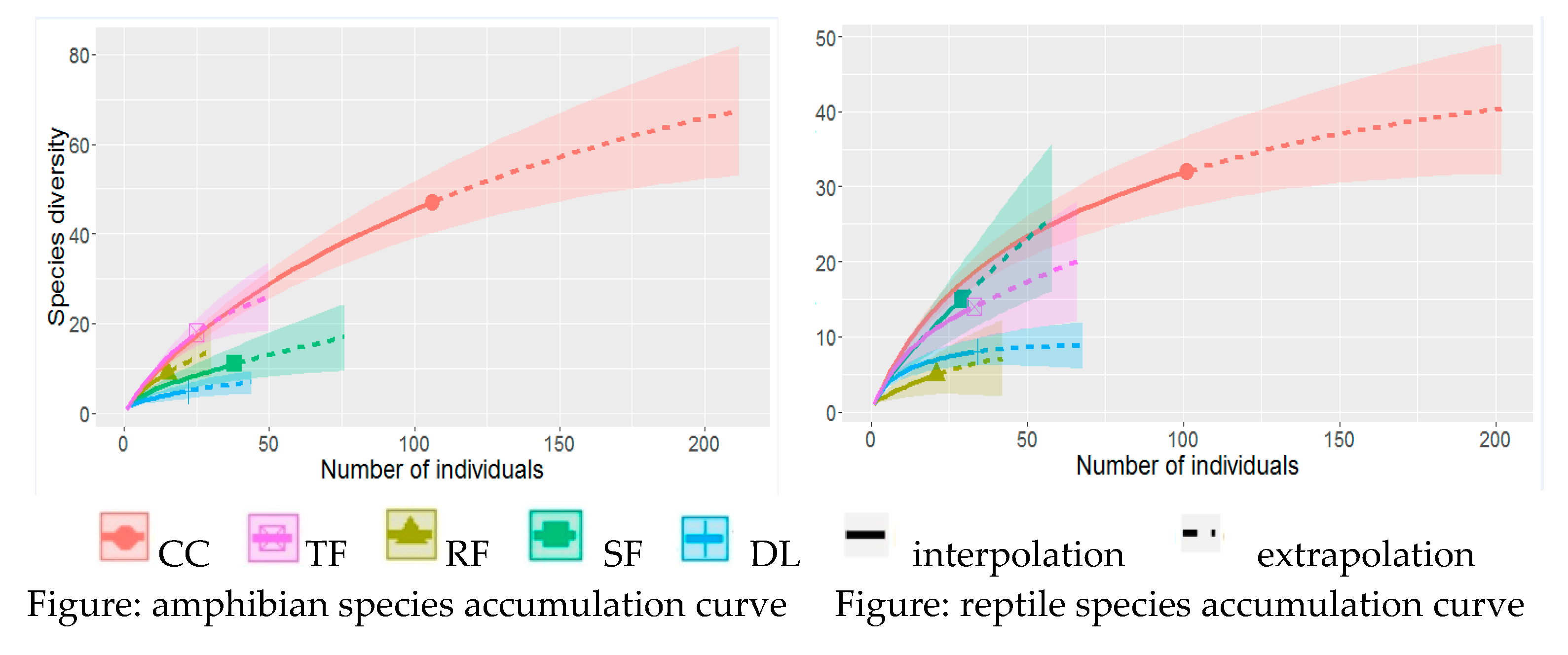

From 44 sites sampled 732 animals were observed, 376 reptiles representing 7 families of 63 species, and 356 amphibians that represent 6 families of 89 species. Five species observed during this research were classified En Danger (EN) and one Vulnerable (VU) in IUCN red list.

Species Richness

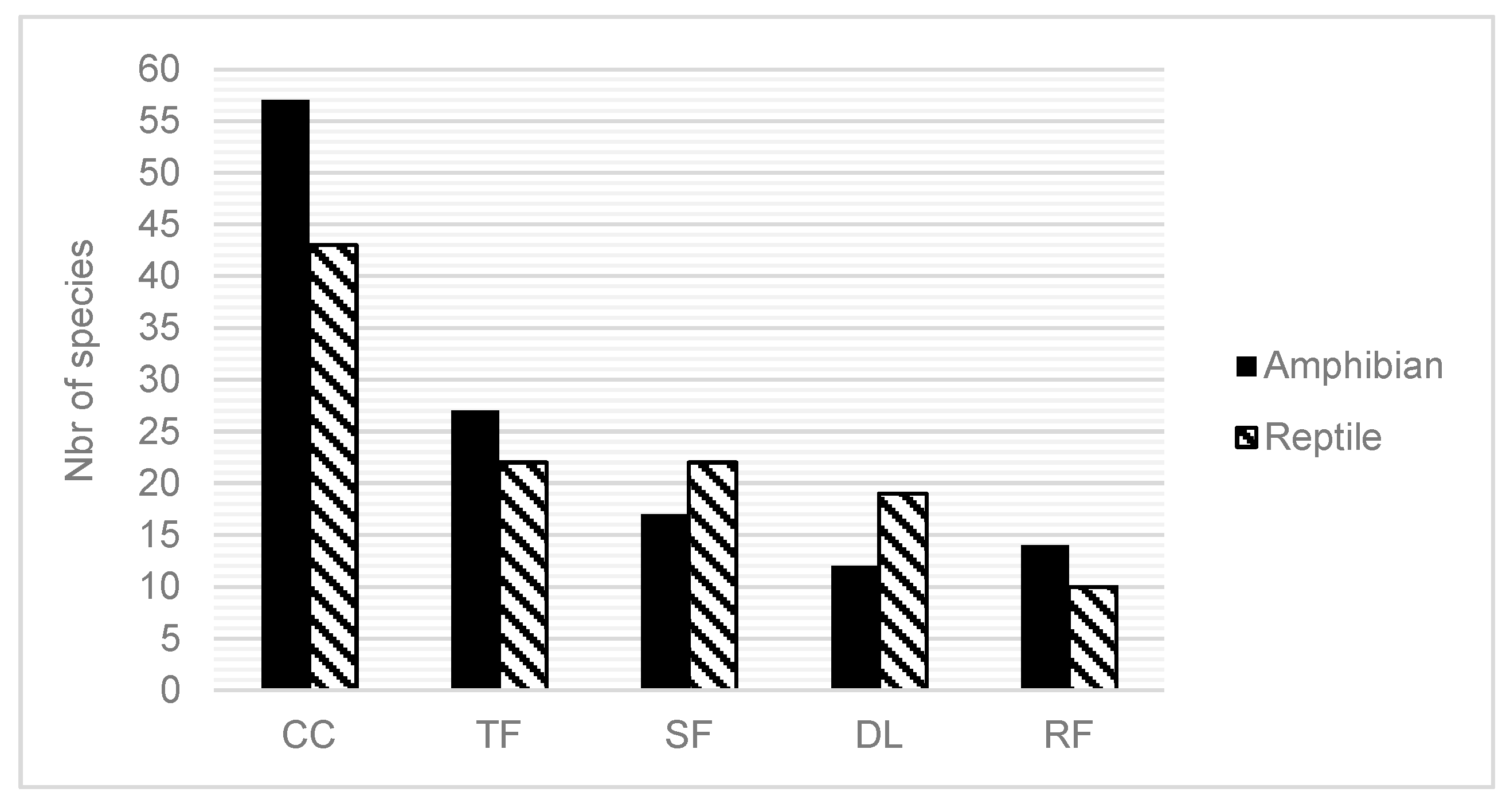

The figure below show the number of species found inside each land use.

Figure 2.

number of observed species between the five land uses.

Figure 2.

number of observed species between the five land uses.

This graphs shows the importance of closed canopy forest compared to others land uses.

Species richness declined dramatically from structurally complex habitat (Closed Canopy) toward structurally simple habitat or open areas (degraded land). In total degraded land has more species that the reforestation plots but it has more amphibians than the degraded land. We found more amphibians from habitat with more trees such as closed canopy, tree fallow and reforestion plots compared to the two others land uses with less trees. Boophis pyrrus, Sanzinia madagascariensis, Calumma nasutum, Phelsuma lineata, Zonosaurus madagascariensis, and Madascincus melanopleura were inventoried in all land uses. Sixty four species of amphibians and reptiles were observed only inside of the closed forest. Five species of reptiles: Stenophis gaimardi, Ramphotyphlops braminus, Bibilava lateralis, Madagascarophis colubrinus, Pseudoxyrhopus heterurus, and two amphibians were founded only in degraded land.

Abundance

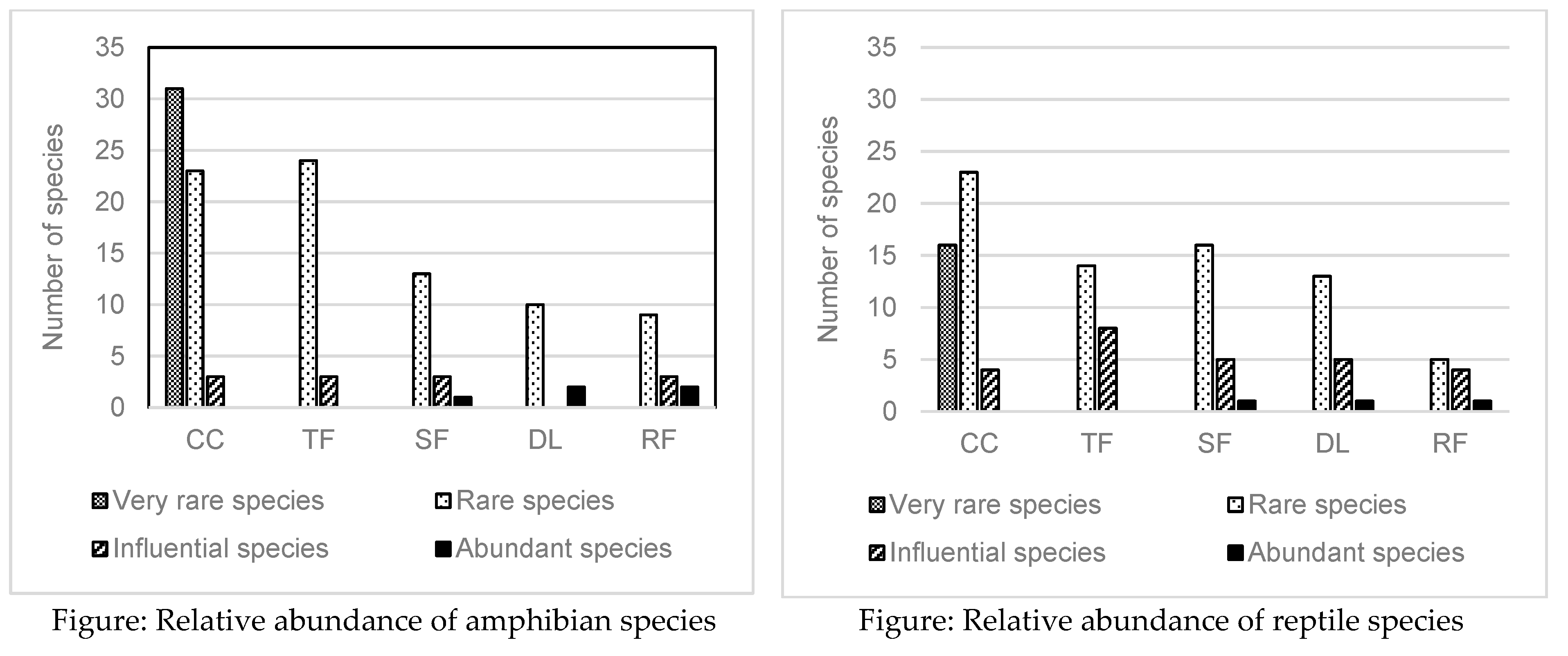

Amphibians and reptiles species distribution according to their abundance is given in the following figure.

These two graphs show the disproportion on the abundance of each species observed considering each land use. This disproportion was found especially in the three more disturbed areas such as shrub fallow, degraded land and reforestation. Species inside of the closed canopy forest can be considered as in good balance with the three first categories and without abundant species. Closed canopy forest is the only one land uses where we found very rare species that mean these species disappear after forest destruction.

Land use change result change on environments and ecological conditions which are favourable to the proliferation of such communities, and the dominance of the most favoured species. This dominance explains the high percentage of catching rate of some species in each site. During this investigation, one species of Madagascar day gecko Phelsuma lineata is frequently observed in shrub fallow and reforestation plots, and the chameleon Calumma nasutum is the abundant species in degraded land.

Trapping Rates

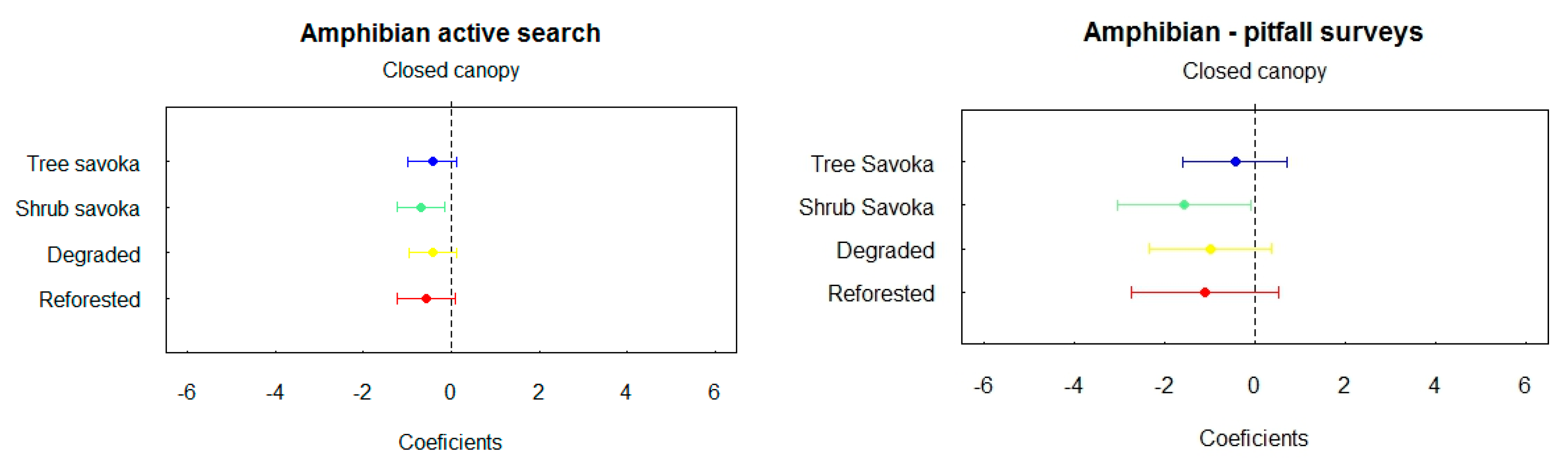

These two plots indicate that the active search is the best method for amphibians’ inventory.

During this investigation, 206 individuals of amphibians grouped in 67 species were observed during active surveys, and 62 of which were inventoried by night and 19 by day. Only 30 individuals of 16 amphibian species were captured in pitfall traps. Trapping rate is high in the closed canopy forest than in the others land uses but this difference isn’t significant except with shrub fallow where this rate is lower. There is no significant difference between tree fallow, shrub fallow, reforested area and degraded land.

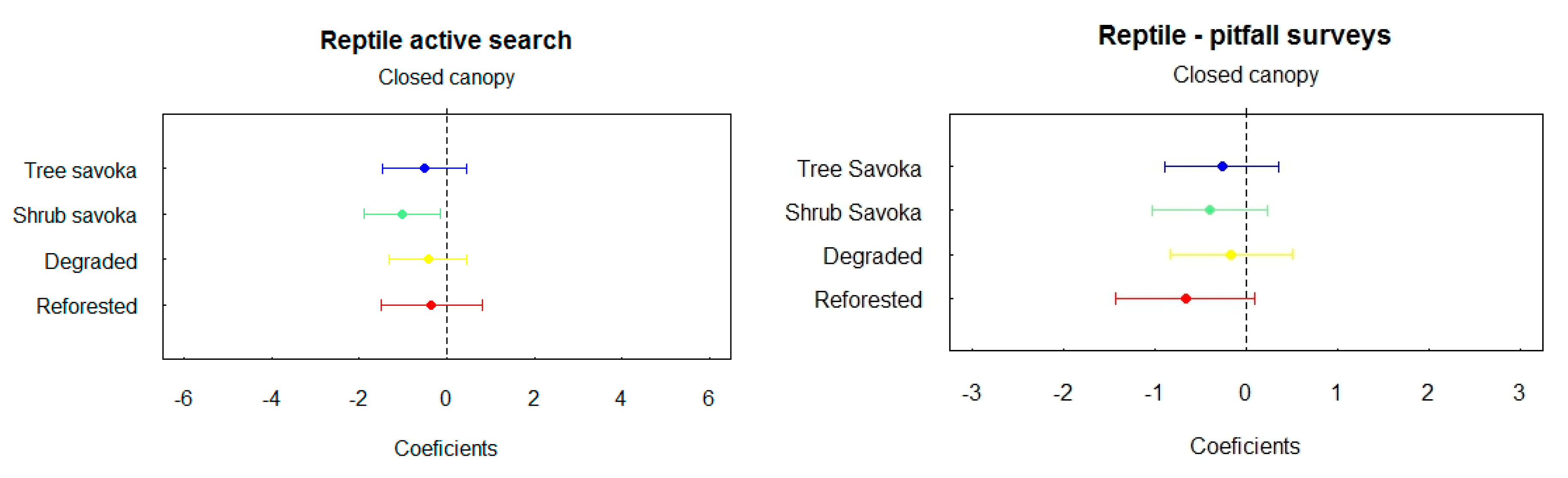

Like found in the amphibians, active search is also the best method for reptiles’ inventory.

For reptiles, 218 individuals of 47 species were inventoried from active surveys (37 by night, 23 by day) and 104 individuals of 12 species from pitfall traps. Trapping rate is higher inside of the closed canopy forest but only difference with shrub fallow in active search is the only significant.

Both encounter and trapping rates are lower in shrub fallow for the active search but this low value was observed from reforestation plot for pitfall traps. There is no significant difference between tree fallow, shrub fallow, reforested area and degraded land. No significant difference is observed between each land uses for pitfall data.

Discussions

- Species Richness

Our results show that amphibians and reptiles were affected by land uses change. For both classes number of species was decrease from closed canopy forest to degraded land. This result was already observed from many previous study and some of them give some explanation of this lost on species richness. Reductions in herpetofaunal species richness in response to disturbances have been largely explained in other studies by reduced forest leaf litter or decreasing canopy cover (Whitfield and Pierce, 2005; Faria et al. 2007; Gardner et al. 2007; Whitfield et al. 2007; Luja et al. 2008; Wagner et al. 2000, 2009; Bickford et al. 2010). Changes in leaf-litter thickness, that affect microhabitats, often explained these patterns (humidity and food-source abundance, Whitfield et al. 2007). Thick litter layers are important for the survival and the diversification of herpetofauna species. This may be related by the different modes of thermoregulation between the two groups (Wanger et al. 2000). The existence of several permanent water points in the forest ensures and maintains humidity and temperature’s equilibrium of the habitats. The presence of large trees and the closed structure of canopy offer a favourable biotope condition for these animals which are very sensitive to the variation of climate change. Forest conversion creates changes in the canopy structure and leaf-litter environment of tropical forests (Gardner et al. 2007). Land-use changes can result in the loss of microhabitats necessary for many amphibians and lizards (e.g., Lieberman 1986; Vitt & Caldwell 2001; Vallan 2002).

- Abundance

Relative abundance of amphibian species reveal that closed canopy forest presents only a very rare species. Rare species were found in all land uses but number of rare species was high in tree fallow and closed canopy forest. Influential species were also present in all land uses. Abundant species (e.g. Ptychadena mascareniensis) were observed only in degraded land, shrub fallow and reforestation because disturbance enables colonization of species not normally found in intact forests (Adum et al. 2013).

For reptiles, relative abundance shows that very rare species are found only in closed canopy forest. Therefore, rare species were observed in all land uses but closed canopy forest has a high number. Influential species were observed in all land uses. Abundant species were observed only in degraded land, shrub fallow and reforestation. It may be explained by the disturbance tolerant species. In this regard, the habitats with a higher degree of disturbance commonly support species with broader ecophysiological tolerances that allow them to adapt to extreme climates (Carnajal-Cogollo and Urbina-Cardona, 2015). Habitat parameters that are expected to be important and that are potentially affected by fragmentation are temperature and relative humidity, leaf litter depth, understory density, herbaceous cover, and canopy cover (Urbina-Cardona et al. 2006; Suazo-Ortuno et al. 2008). We think also that the size of each land use is one of the reasons of this inequality. In general closed canopy forest occupied one big space which we cannot survey all during our research and all the area can be used by the animal. Against for the others land uses which are represented by small size and species prefers this microhabitat should only use these small patches that mean the probability of the detection of these species is very high because our research plot occupied all the area.

The sensitivity of amphibians and reptiles to habitat spatial changes is known to be highly variable among species, depending on their life history traits and habitat requirements (Tocher et al. 1997; Gibbs 1998; Pineda and Halffter 2004; Urbina-Cardona et al. 2006; Hernandez-Ordonez et al. 2015; Meza-Parral and Pineda 2015).

- Trapping Rate

Results from this study indicate that the active search is the main method that allows finding many species of amphibians and reptiles. It means that this technic can be chosen from the others if the researcher have time and resources constraints but need to have a maximum of observation. However, using the standard method is critical to allow for comparative analysis on species richness and other ecological and natural history parameters (Raselimanana, 2010).

Conclusions

The change in land use may have a serious impact on amphibian and reptile species. Species could be affected directly by habitat loss and by habitat quality degradation resulting from selective tree cutting and traditional practices (slash-and-burn agriculture). Land use type had a strong effect on the richness, abundance and composition of herpetofauna (Kurz et al. 2014). Results of other studies highlighted the importance of some abiotic variables (Whitfield and Pierce, 2005; Faria et al. 2007; Gardner et al. 2007; Whitfield et al. 2007; Luja et al. 2008; Wagner et al. 2000, 2009; Bickford et al. 2010), future research could be studied in depth the multiple environmental gradients to understand the disturbance-tolerant species.

Slash and burn agriculture or Tavy, a traditional and predominant land use practice of the Betsimisaraka people, is the major cause of upland degradation and deforestation of the forest in the eastern region of Madagascar. Intensive Tavy practice not only leads to forest and biodiversity loss, but also degrades local and regional ecosystems. Madagascar biodiversity will continue to disappear, unless affordable and sustainable upland farming techniques are developed. The careful development of alternative agricultural practices should especially be done in collaboration with young farmers. Habitat restoration is important by planting tree and additional products such as fruits as an added benefit of people.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to ESPA because the p4ges project is supported by grants NE/K010220/1. We thank the Ministry of Environment, Ecology and Forest for permissions to do this research (research permit number: 192/14/MEF/SG/DGF/DCB.SAP/SCB on 24th July and 021/15/MEF/SG/DGF/DCB.SAP/SCB on 27th January 2015). We’d like to thank the Ecole Supérieur des Sciences Agronomiques for their help on administration procedure during this project. Many thanks to all P4GES biophysical work package team for their support on site selection and collaboration during the field work. We also thank all institutions around the study area for their collaboration such as Conservation International, the principal Manager of CAZ, Association Mitsinjo in Andasibe, GERP (Groupe des Experts sur la Recherche des Primates) in Maromizaha, Man And the Environment in Vohimana. We thank the regional and local authorities in Moramanga District, Tamatave and Didy for their assistances during the data collection. We’d like to thanks the local community around all study sites for their precious collaboration during the field work.

References

- Adum, G. B., Eichhorn, M. P., Oduro, W., Boateng, C. O., Rödel, M. O. (2013): Two-Stage Recovery of Amphibian Assemblages Following Selective Logging of Tropical Forests. Conservation Biology, Volume 27, No. 2, 354-363.

- Aide, M.T., Zimmerman, J.K., Pascarella, J.B., Rivera, L., Marcano-Vega, H., 2000. Forest regeneration in a chronosequence of tropical abandoned pastures: implications for restoration ecology. Restor. Ecol. 8, 328–338.

- Anderson, P., 1995. Ecological restoration and creation: a review. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 56 (Suppl.), 187–211.

- Andrén, H., 1994. Effects of habitat fragmentation on birds and mammals in landscapes with different proportions of suitable habitat: a review. Oïkos 71, 355–366.

- Andreone, F., Cadle, J.E., Cox, N.A., Glaw, F., Nussbaum, R.A., Raxworthy, C.J., Stuart, S.N., Vallan, D., Vences, M., 2005a. Species review of amphibian extinction risks in Madagascar: conclusions from the Global Amphibian Assessment. Conserv. Biol. 19, 1790–1802.

- Andreone, F., Carpenter, A.I., Cox, N., du Preez, L., Freeman, K., Furrer, S., Garcia, G., Glaw, F., Glos, J., Knox, D., Kohler, J., Mendelson, J.R., Mercurio, V., Mittermeier, R.A., Moore, R.D., Rabibisoa, N.H.C., Randriamahazo, H., Randrianasolo, H., Raminosoa, N.R., Ramilijaona, O.R., Raxworthy, C.J., Vallan, D., Vences, M., Vieites, D.R., Weldon, C., 2008. The challenge of conserving amphibian megadiversity in Madagascar. PLOS Biol. 6, 943–946.

- Andreone, F., Fabio, M., Riccardo, J. and Jasmin, E. R. (2001b): Two new chameleons of the genus Calumma from north-east Madagascar, with observations on hemipenial morphology in the Calumma furcifer group (Reptilia, Squamata, Chamaeleonidae). The Herpetological Journal 11 (2):53-68.

- Andreone, F., Glaw, F., Nussbaum, R.A., Raxworthy, C. J., Vences, M., & Randrianirina, J.E. (2003): The amphibians and reptiles of Nosy Be (NW Madagascar) and nearby islands: a case study of diversity and conservation of an insular fauna.Journal of Natural History, 37(17): 2119-2149.

- Andreone, F., Guarino, F.M., Randrianirina, J.E., 2005b. Life history traits, age profile, and conservation of the panther chameleon, Furcifer pardalis (Cuvier 1829), at Nosy Be, NW Madagascar. Trop. Zool. 18, 209–225.

- Andreone, F., Randrianirina, J.E., Jenkins, P.D., & Aprea, G. (2000): Species diversity of Amphibia, Reptilia and Lipotyphla (Mammalia) at Ambolokopatrika, a rainforest between the Anjanaharibe-Sud and Marojejy massifs, NE Madagascar. Biodiversity and Conservation, 9: 1587-1622.

- Andreone, F., Vences, M., &Randrianirina, J.E. (2001a): Patterns of amphibian and reptile diversity at Berara Forest (Sahamalaza Peninsula), NW Madagascar. Italian Journal of Zoology, 68: 235-241.

- Andreone, F., Dawson, J.S., Rabemananjara, F.C.E., Rabibisoa, N.H.C. & Rakotonanahary, T.F. (eds). 2016. New Sahonagasy Action Plan 2016–2020 / Nouveau Plan d'Action Sahonagasy 2016–2020. Museo Regionale di Scienze Naturali and Amphibian Survival Alliance, Turin.

- Bickford, D., Ng, T. H., Qie, L., Kudavidanage, E. P., & Bradshaw, C. J. A. (2010): Forest fragment and breeding habitat characteristics explain frog diversity and abundance in Singapore. Biotropica, 42, 119–125.

- Bloxam, Q.M.C., Behler, J.L., Rakotovao, E.R., Randriamahazo, H., Hayes, K.T., Tonge, S.J., Ganzhorn, J.U., 1996. Effects of logging on the reptile fauna of the Kirindy Forest with special emphasis on the flat-tailed tortoise (Pyxis planicauda). In: Ganzhorn, J.U., Sorg, J.-P. (Eds.), Ecology and Economy of a Tropical Dry Forest in Madagascar. Primate Report 46 (1), pp. 189–203.

- Brady, L.D., Griffiths, R.A., 1999. Status Assessment of Chameleons in Madagascar. IUCN.

- Brand, J., Rakotondranaly, N., 1997. Les caractéristiques et la fertilité des sols. In: BEMA/Projet Terre-Tany (Ed.), Un système agro-écologique dominé par le Tavy: la région de Beforona, Falaise-Est de Madagascar, vol. 6. Projet Terre-Tany/BEMA, Centre pour le Développement et l’Environnement CDE/GIUB, et FOFIFA/Madagascar, Antananarivo, Madagascar, pp. 34–48.

- Carvajal-Cogollo, J. E., Urbina-Cardona, N. (2015): Ecological grouping and edge effects in tropical dry forest: reptile-microenvironment relationships. Biodiversity Conservation 24: 1109-1130.

- Casse, T., Milho j, A., Rainaivoson, S., Randriamanarivo, J.R., 2004. Causes of deforestation in south western Madagascar: what do we know? Forest Pol. Econ. 6, 33–48.

- Chikoye, D., Manyong, V.M., Ekeleme, F. (2000): Characteristics of speargrass (Imperatacylindrica) dominated fields in West Africa: crops, soil properties, farmer perceptions and management strategies. CropProt. 19, 481–487.

- Cornet A., J. L. Guillaumet (1976) : Division floristiques et étages de végétation à Madagascar. Cah. ORSTOM, série. Biol., vol. XI, no 1, 1976 : 35-40.

- Dandoy, G. (1973) : Terroirs et économies villageoises de la région de Vavatenina (Côte Orientale Malgache). ORSTOM, Paris, France.

- D. Cruze, N., Sabel, J., Green, K., Dawson, J., Gardner, C., Robinson, J., Starkie, G., Vences, M., & Glaw, F. (2007): The first comprehensive survey of amphibians and reptiles at Montagne des Français. Madagascar. Herpetological Conservation and Biology, 2: 87-99.

- Dobson, A.P., Bradshaw, A.D., Baker, A.J.M., 1997. Hopes for the future: restoration ecology and conservation biology. Science 277, 515–522.

- Faramalala, M.H., (1988) : Etude de la Végétation de Madagascar à l’aide des Données spatiales. Doctoral Thesis, Univ. Paul Sabatier de Toulouse, 167 p.

- Faria, D., Paciencia, M.L.B., Dixo, M., Laps, R.R., Baumgarten, J., (2007): Ferns, frogs, lizards, birds and bats in forest fragments and shade cacao plantations in two contrasting landscapes in the Atlantic forest, Brazil. Biodivers. Conserv. 16, 2335–2357.

- Gardner, T. A., Ribeiro-Junior, M.A., Barlow, J., Avila-Pires, T.C. S., Hoogmoed, M. S., Peres. C. A. (2007): The Value of Primary, Secondary, and Plantation Forests for a Neotropical Herpetofauna. Conservation Biology, Volume 21, No. 3, 775-787.

- Garrity, D.P., Soekardi, M., VanNoordwijk, M., DelaCruz, R., Pathak, P.S., Gunasena, H.P.M., Vanso, N., Huijun, G., Majid, N.M. (1996): The Imperata grasslands of tropical Asia: area, distribution, and typology. Agrofor. Syst. 36, 3–29.

- Gibbs, J. P. (1998): Distribution of woodland amphibians along a forest fragmentation gradient. Landscape Ecol 13:263–268.

- Glaw, F., Schmidt, K., & Vences, M. (2003): Paroedura, Nachtgeckos aus Madagaskar DATZ, Die Aquarien- und Terrarienzeitschrift, 56(9): 6-11.

- Glaw, F., Vences, M. (1994): A Field guide to the Amphibians and Reptiles of Madagascar, 2nd edn. Köln: M. Vences and F. Glaw.

- Glaw, F., Vences, M., 2007. A Fieldguide to the Amphibians and Reptiles of Madagascar. Verlags GbR, Köln.

- Glos, J., 2003. The amphibian fauna of the Kirindy dry forest in western Madagascar. Salamandra 39, 75–90.

- Glos, J., Dausmann, K.H., Linsenmair, K.E., 2008a. Modelling the habitat use of Aglyptodactylus laticeps, an endangered dry-forest frog from Western Madagascar. In: Andreone, F. (Ed.), A Conservation Strategy for the Amphibians of Madagascar. Monografie del Museo Regionale di Scienze Naturali di Torino. XLV, Torino, pp. 125–142.

- Glos, J., Volahy, A.T., Bourou, R., Straka, J., Young, R., Durbin, J., 2008b. Amphibian conservation in Central Menabe. In: Andreone, F. (Ed.), A Conservation Strategy for the Amphibians of Madagascar, Monografie del Museo Regionale di Scienze Naturali di Torino. XLV, Torino, pp. 107–124.

- Glos, J., Wegner, F., Dausmann, K.H., Linsenmair, K.E., 2008c. Oviposition-site selection in an endangered Madagascan frog: experimental evaluation of a habitat model and its implications for conservation. Biotropica 40, 646–652.

- Grist, P., Menz, K. (2000): Evaluation of fire versus non-fire methods for clearing Imperata fallow. In: Menz, K., Magcale-Macandog, D., Wayan Rusastra, I. (Eds.), Improving Smallholder Farming Systems in Imperata Areas of Southeast Asia: Alternatives to Shifting Cultivation, vol. 52. ACIAR, Canberra, Australia, pp. 25–34.

- Grist, P., Menz, K. (1997): On-site effects of Imperata burning by Indonesian smallholders: a bioeconomic model. Bull. Indonesian Econ. Stud. 33, 79–96.

- Hannah, L., Radhika, D., Lowry II, P.P., Andelman, S., Andrianarisata, M., Andriamaro, L., Cameron, A., Hijmans, R., Kremen, C., MacKinnon, J., Randrianasolo, H.H., Andriambololonera, S., Razafimpahanana, A., Randriamahazo, H., Randrianarisoa, J., Razafinjatovo, P., Raxworthy, C., Schatz, G.E., Tadross, M., Wilmé, L., 2008. Climate change adaptation for conservation in Madagascar. Biol. Lett. 4, 590–594.

- Harper, G.J., Steininger, M.K., Tucker, C.J., Juhn, D., Hawkins, F., 2007. Fifty years of deforestation and forest fragmentation in Madagascar. Environ. Conserv. 34, 325–333.

- Hartemink, A.E. (2001): Biomass and nutrient accumulation of Piper aduncum and Imperatacylindrica fallows in the humid lowlands of Papua New Guinea. For. Ecol. Manage. 144, 19–32.

- Hernandez-Ordonez, O., Urbina-Cardona, N., Martınez-Ramos, M. (2015): Recovery of amphibian and reptile assemblages during old-field succession of tropical rain forests. Biotropica 47:377–388.

- Hoegh-Guldberg, O., Hughes, L., McIntyre, S., Lindenmayer, D.B., Parmesan, C., Possingham, H.P., Thomas, C.D., 2008. Assisted colonization and rapid climate change. Science 321, 345–346.

- Jackman, T.R., Bauer, A.M., Greenbaum, E., Glaw, F., & Vences, M. (2008): Molecular phylogenetic relationships among species of the Malagasy-Comoran gecko genus Paroedura (Squamata: Gekkonidae). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 46(1): 74-81.

- Jenkins, R.K.B., Brady, L.D., Bisoa, M., Rabearivony, J., Griffiths, R.A. (2003): Forest disturbance and river proximity influence chameleon abundance in Madagascar. Biological Conservation. 109: 407-415.

- Jenkins, R.K.B., Brady, L.D., Huston, K., Kauffmann, J.L.D., Rabearivony, J., Raveloson, G., Rowcliffe, M. (1999): The population status of chameleons within Ranomafana National Park, Madagascar. Oryx 33: 38-47.

- Kelly M.H. (2012): Inventory and monitoring toolbox: herpetofauna. DeparDLent of Conservation Te Papa Atawhai. DOCDM-760240 Herpetofauna: pitfall trapping v1.0: 1-22.

- Koechlin, J. (1972): Flora and vegetation of Madagascar. Pp. 144–190 in Battistini, R. & Richard-Vindard, G. (eds). Biogeography and ecology of Madagascar Dr. W. Junk B. V., Publishers, The Hague.

- Köhler, P., Chave, J., Riéra, B., Huth, A., 2003. Simulating the long-term response of tropical wet forests to fragmentation. Ecosystems 6, 114–128.

- Kurz, D.J., Nowakowski, A. J., Tingley, M. W., Donnelly, M.A., Wilcove, D.S. (2014): Forest-land use complementarity modifies community structure of a tropical herpetofauna. Biological Conservation 170 (2014) 246–255.

- Lamb, D., Erskine, P.D., Parrotta, J.A., 2005. Restoration of degraded tropical forest landscapes. Science 310, 1628–1632.

- Leuteritz, T.E.J., Lamb, T., Limberaza, J.C., 2005. Distribution, status, and conservation of radiated tortoises (Geochelone radiata) in Madagascar. Biol. Conserv. 124, 451–461.

- Lieberman, S. S. (1986): Ecology of the leaf-litter herpetofauna of a neotropical rainforest. Acta Zoologica Mexicana 15:1–72.

- Luja, V. H., Herrando-Perez, S., Gonzalez-Solis, D., & Luiselli, L. (2008): Secondary rain forests are not havens for reptile species in tropical Mexico. Biotropica, 40, 747-757.

- Meza-Parral, Y., Pineda, E. (2015): Amphibian diversity and threatened species in a severely transformed Neotropical region in Mexico. PLoS ONE 10(3):e0121652.

- Nussbaum, R.A. & Raxworthy, C.J. (1994): A new rainforest gecko of the genus Paroedura GÜNTHER from Madagascar. Herpetological Natural History 2 (1): 43-49.

- Nussbaum, R.A., Raxworthy, C.J., Raselimanana, A.P., &Ramanamanjato, J.B. (1999): Amphibians and reptiles of the Réserve Naturelle Intégrale d'Andohahela, Madagascar. In S.M. Goodman (Ed.).A floral and faunal inventory of the Réserve Naturelle Intégrale d'Andohahela, Madagascar with particular reference to elevational variation. Fieldiana: Zoology, new series, 94: 155-173.

- Paquette, S.R., Behncke, S.M., O’Brien, S.H., Brenneman, R.A., Louis, E.E., Lapointe, F.J., 2007. Riverbeds demarcate distinct conservation units of the radiated tortoise (Geochelone radiata) in southern Madagascar. Conserv. Genet. 8, 797–807.

- Penner, J., 2005. Reptile Communities in the Kirindy Dry Forest (Western Madagascar) – What is the Pattern? PhD Dissertation, Würzburg University, Germany, 107 p.

- Pfund, J.-L., 2000. Culture sur bruˆ lis et gestion des ressources naturelles, évolution et perspectives de trois terroirs ruraux du versant est de Madagascar. Thèse de Doctorat. Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland.

- Phillipson, P.P., Schatz, G.R., Lowry, I.I.P.P., Labat, F.-N., 2006. A catalogue of the vascular plants of Madagascar. In: Ghazanfar, S.A., Beentje, H.J. (Eds.), Taxonomy and Ecology of African Plants: Their Conservation and Sustainable Use. Proceedings XVIIth AETFAT Congress. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

- Pineda, E., Halffter, G. (2004): Species diversity and habitat fragmentation: frogs in a tropical montane landscape in Mexico. Biol Conserv 117:499–508.

- Rakotomalala, D. & Raselimanana, A.P. (2003): Les amphibiens et les reptiles des massifs de Marojejy, d'Anjanaharibe-Sud et du couloir forestier de Betaolana. In S.M. Goodman & L. Wilmé (Eds.). Nouveaux résultats d'inventaires biologiques faisant référence à l'altitude dans la région des massifs montagneux de Marojejy et d'Anjanaharibe-Sud. Recherches pour le Développement. Série Sciences Biologiques. Centre d'Information et de Documentation Scientifique et Technique, Antananarivo, 19 : 147-202.

- Rakotondravony, H.A. (2006a) : Reptiles et amphibiens de la Réserve Spéciale de l'Analamerana et de la forêt classée d'Andavakoera dans l'extrême Nord de Madagascar. In S.M. Goodman & L. Wilmé (eds). Inventaires de la faune et de la flore du nord de Madagascar dans la région Loky-Manambato, Analamerana et Andavakoera. Recherches pour le Développement. Série Sciences Biologiques. Centre d'Information et de Documentation Scientifique et Technique, Antananarivo, 23 : 149-173.

- Rakotondravony, H.A. (2006b): Patterns de la diversité des reptiles et amphibiens de la région de Daraina, extrême Nord de Madagascar. In S.M. Goodman & L. Wilmé (eds). Inventaires de la faune et de la flore du nord de Madagascar dans la région Loky-Manambato, Analamerana et Andavakoera. Recherches pour le Développement. Série Sciences Biologiques. Centre d'Information et de Documentation Scientifique et Technique, Antananarivo, 23 : 101-148.

- Rakotondravony, H.A. (2007): Conséquences de la variation des superficies forestières sur les communautés de reptiles et d'amphibiens dans la région de Loky-Manambato, extrême nord-est de Madagascar. Revue d'Ecologie (Terre et Vie), 62 : 209-227.

- Ramanamanjato, J.B. &Rabibisoa, N. (2002): Evaluation rapide de la diversité biologique des reptiles et amphibiens de la Réserve Naturelle Intégrale d'Ankarafantsika, Madagascar. In Alonso, L.E., Schulenberg, T.S., Radilofe, S., &MiSF, O. (Eds). A Biological Assessment of the RéserveNaturelleIntégraled'Ankarafantsika, Madagascar. RAP Bulletin of Biological Assessment (#23). Conservation International, Washington, DC 98-103, 135-138.

- Ramanamanjato, J.-B., 2000. Fragmentation effects on reptile and amphibian diversity in the littoral forest of southeastern Madagascar. In: Rheinwald, G. (Ed.), Bonner Zoologische Monographien, pp. 297–308.

- Randrianantoandro, J.C, Razafimahatratra, B., Soazandry, M., Ratsimbazafy, J., Jenkins, R.K.B. (2010b): Habitat use by chameleons in a deciduous forest in western Madagascar. Amphibia-Reptilia 31: 27-35.

- Randrianantoandro, J.C., Andriantsimanarilafy, R.R., Rakotovololonalimanana, H., Fideline, H.E.,Rakotondravony, D., Ramilijaona, R.O., Ratsimbazafy, J., Razafindrakoto, G.F., & Jenkins, R.K.B. (2010a): Population assessments of chameleons from two montane sites in Madagascar. Herpetological Conservation and Biology 5(1):23-31.

- Randrianantoandro, J.C., Randrianavelona, R., Andriantsimanarilafy, R.R., Fideline, H.E., Rakotondravony, D., & Jenkins, R.K.B. (2007): Roost site characteristics of sympatric dwarf chameleons (genus Brookesia) from western Madagascar. Amphibia-Reptilia 28: 577-581.

- Raselimanana, A.P. & Andriamampionona R. (2007): Inventaires de la faune et de la flore du couloir forestier d’Anjozorobe-Angavo.. In S.M. Goodman & L. Wilmé (eds). Recherches pour le Développement. Série Sciences Biologiques. Centre d'Information et de Documentation Scientifique et Technique, Antananarivo, 24: 111-139.

- Raselimanana, A.P. (2004): L'herpétofaune de la forêt de Mikea. In Goodman, S.M. & A.P. Raselimanana (Eds.).Inventaire floristique et faunistique de la forêt de Mikea : Paysage écologique et diversité biologique d'une préoccupation majeure pour la conservation. Recherches pour le Développement. Série Sciences Biologiques. Centre d'Information et de Documentation Scientifique et Technique, Antananarivo, 21 : 37-52.

- Raselimanana, A.P., Raxworthy, C.J., & Nussbaum, R.A. (2000): Herpetofaunal species diversity and elevational distribution within the Parc National de Marojejy, Madagascar. In S.M. Goodman (Ed). A floral and faunal inventory of the Parc National de Marojejy, Madagascar: with reference to elevational variation. Fieldiana: Zoology, new series, 97: 157-173.

- Raselimanana, A. P. (2010): The amphibians and reptiles of the Ambatovy-Analamay region. In Biodiversity, exploitation, and conservation of the natural habitats associated with the Ambatovy project, eds S. M. Goodman & V. Mass. Malagasy Nature, 3 : 99-123.

- Raxworthy, C. J. & Nussbaum R. A. (1994): A rainforest survey of amphibians, reptiles and small mammals at Montagne d’Ambre, Madagascar. Biological Conservation, 69: 65-73.

- Raxworthy, C. J. & Nussbaum R. A. (1996): Amphibians and reptiles of the Reserve NaturelleIntegraled'Andringitra, Madagascar: A study of elevational distribution and local endemicity, pp. 158-170. In Goodman, S. M., ed., A Floral and Faunal Inventory of the Eastern Slopes of the Reserve Naturelle Integrale d'Andringitra, Madagascar: with reference to elevational variation.

- Raxworthy, C.J., Andreone, F., Nussbaum, R.A., Rabibisoa, N., &Randriamahazo, H.(1998): Amphibians and Reptiles of the Anjanaharibe-SudMassif, Madagascar: elevational distribution and regional endemicity. In S.M. Goodman (Ed.). A floral and faunal inventory of the RéserveSpéciale d'Anjanaharibe-Sud, Madagascar: with reference to elevational variation. Fieldiana: Zoology, new series, 90: 79-92.

- Raxworthy, C.J., Pearson, R.G., Rabibisoa, N., Rakotondrazafy, A., Ramanamanjato, J.- B., Raselimanana, A.P., Wu, S., Nussbaum, R.A., Stone, D.A., 2008. Extinction vulnerability of tropical montane endemism from warming and upslope displacement: a preliminary appraisal for the highest massif in Madagascar. Global Change Biol. 14, 1703–1720.

- Schmid, J. & Alonso, L.E. (Eds.) (2005) : Une évaluation biologique rapide du corridor Mantadia-Zahamena à Madagascar. Bulletin RAP d’Evaluation Rapide 32. Conservation International. Washington, DC, 32 :1-202.

- Scott, D.M., Brown, D., Mahood, S., Denton, B., Silburn, A., Rakotondraparany, F., 2006. The impacts of forest clearance on lizard, small mammal and bird communities in the arid spiny forest, southern Madagascar. Biol. Conserv. 127, 72–87.

- Styger, E., Rakotondramasy, H.M., Pfeffer, M.J., Fernandes, E.C.M., &Bates D.M. (2007): Influence of slash-and-burn farming practices on fallow succession and land degradation in the rainforest region of Madagascar. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 119 (2007) 257–269.

- Suazo-Ortuno, I., Alvarado-Diaz, J., Martinez-Ramos, M. (2008): Effects of conversion of dry tropical forest to agricultural mosaic on herpetofaunal assemblages. Conserv Biol 22:362–374.

- Tocher, M., Gascon, C., Zimmerman, B. (1997): Fragmentation effects on a central Amazonian frog community: a ten year study. In: Laurance WF, Bierregaard RO (eds) Tropical Forest Remnants: Ecology, Management and Conservation of Fragmented Communities. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 124–137.

- Travis, J.M.J., 2003. Climate change and habitat destruction: a deadly anthropogenic cocktail. Proc. R. Soc. B 270, 467–473.

- Urbina-Cardona, J.N., Olivares-Pérez, M.I., Reynoso, V.H. (2006): Herpetofauna diversity and microenvironment correlates across the pasture-edge-interior gradient in tropical rainforest fragments in the region of Los Tuxtlas. Veracruz Biol Conserv 132:61–75.

- Urech, Z.L., Rabenilalana, M., Sorg, J.-P., Felber, H.R., 2011. Traditional use of forest fragments in Manompana, Madagascar. In: Colfer, C.J.P., Pfund, J.-L. (Eds.), Collaborative Governance of Tropical Landscapes. Earthscan, pp. 131–155.

- Vallan, D., 2000. Influence of forest fragmentation on amphibian diversity in the nature reserve of Ambohitantely, highland Madagascar. Biol. Conserv. 96, 31– 43.

- Vallan, D., 2002. Effects of anthropogenic environmental changes on amphibian diversity in the rain forests of eastern Madagascar. J. Trop. Ecol. 18, 725–742.

- Vallan, D., Andreone, F., Raherisoa, V.H., Dolch, R., 2004. Does selective wood exploitation affect amphibian diversity? The case of An’Ala, a tropical rainforest in eastern Madagascar. Oryx 38, 410–417.

- Vences, M., Andreone, F., Glaw, F., Raminosoa, N., Randrianirina, J.E., Vieites, D.R., 2002. Amphibians and reptiles of the Ankaratra Massif: reproductive diversity, biogeography and conservation of a montane fauna in Madagascar. Ital. J. Zool. 69, 263–284.

- Vieites, D.R., Wollenberg, K., Andreone, F., Kohler, J., Glaw, F., Vences, M., 2009. Vast underestimation of Madagascar’s biodiversity evidenced by an integrative amphibian inventory. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 8267–8272.

- Vitousek, P.M., 1994. Beyond global warming: ecology and global change. Ecology 75, 1861–1876.

- Vitt, L. J., and J. P. Caldwell (2001): The effects of logging on reptiles and amphibians of tropical forests. Pages: 239–260 in R. A. Fimbel, A. Grajal, and J. Robinson, editors. The cutting edge. Columbia University Press, New York.

- Wagner, T. C., Anger, Iskandar D. T., Motzke, I., Brook, B. W., Sodhi, N. S.,Clough Y., Tscharntke, T. (2000): Effects of Land-Use Change on Community Composition of Tropical Amphibians and Reptiles in Sulawesi, Indonesia. Conservation Biology, Volume 24, No. 3, 795–802.

- Wanger, T.C., Saro, A., Iskandar, D.T., Brook, B.W., Sodhi, N.S., Clough, Y., Tscharntke, T. (2009): Conservation value of cacao agroforestry for amphibians and reptiles in South-east Asia: combining correlative models with follow-up field experiments. J. Appl. Ecol. 46, 823–832.

- Whitfield, S.M., Bell, K.E., Philippi, T., Sasa, T., Bolanos, F., Chaves, G., Savage, J.M., Donnelly, M.A. (2007): Amphibian and reptile declines over 35 years at La Selva, Costa Rica. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104, 8352–8356.

- Whitfield, S.M., Pierce, M.S.F. (2005): Tree buttress microhabitat use by a neotropical leaf-litter herpetofauna. J. Herpetol. 39, 192–198.

- Willis, S.G., Hole, D.G., Collingham, C.Y., Hilton, G., Rahbek, C., Huntley, B., 2008. Assessing the impacts of future climate change on protected area networks: a method to simulate individual species’ responses. Environ. Manage. 43, 836–845.

- Young, R.P., Volahy, A.T., Bourou, R., Lewis, R., Durbin, J., Fa, J.E., 2008. Estimating the population of the endangered flat-tailed tortoise Pyxis planicauda in the deciduous, dry forest of western Madagascar: a monitoring baseline. Oryx 42, 252–258.

- Young, T.P., 2000. Restoration ecology and conservation biology. Biol. Conserv. 92, 73–83.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).