Submitted:

22 April 2024

Posted:

23 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2.1. Materials

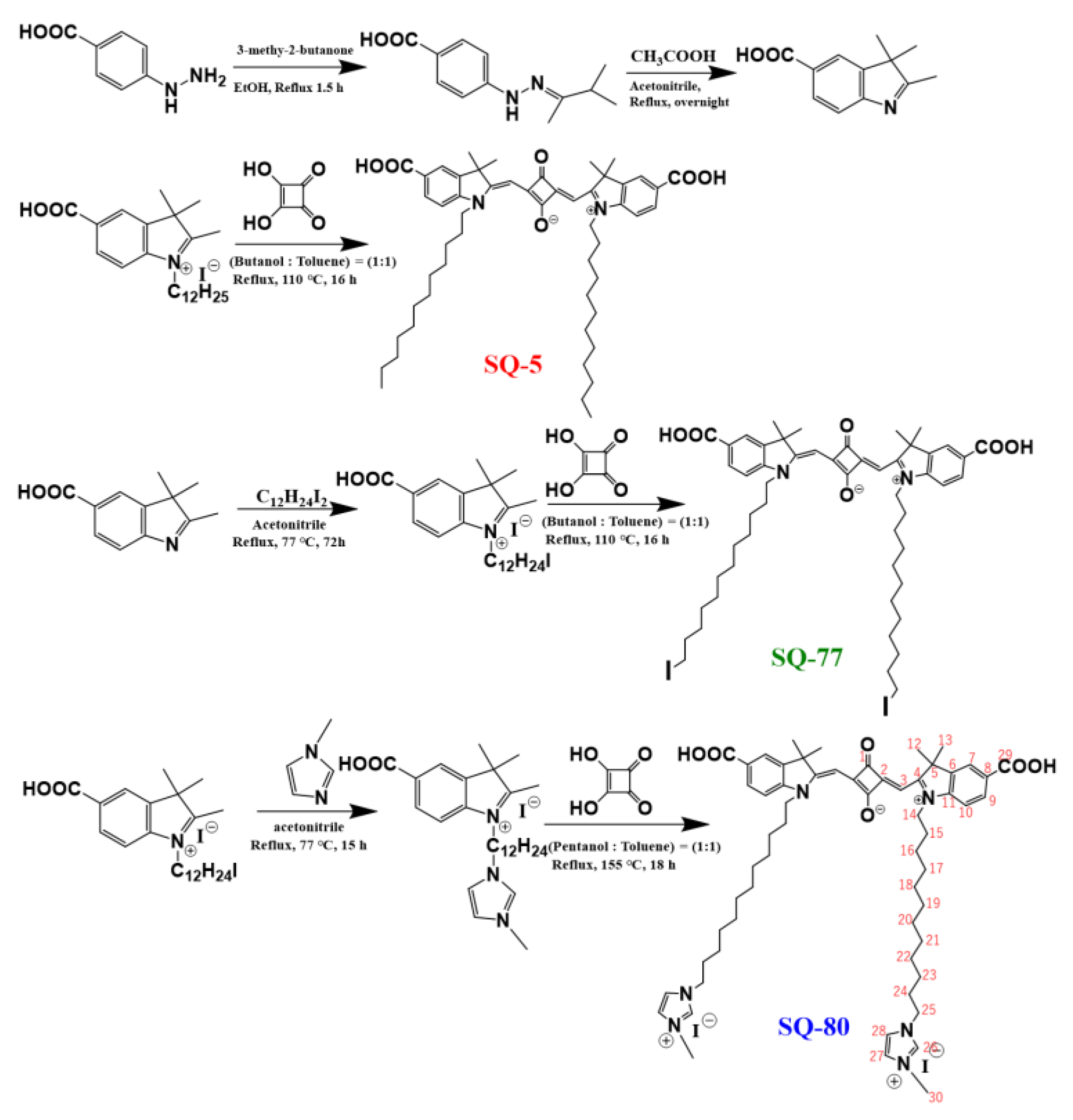

2.2. Intermediates and Dyes Synthesis

2.2.1. Synthesis of 5-Carboxy-2,3,3-trimethyl-1-(12-1-methylimidazoledodecyl)-3H-indolium Iodide

2.2.2. Synthesis of Symmetrical Squaraine Dye SQ-80

2.2.5. Characterizations of Synthesized SQ-80

2.3. Fabrication and Characterization of DSSCs

2.3.1. Device Fabrication

2.3.2. Device Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

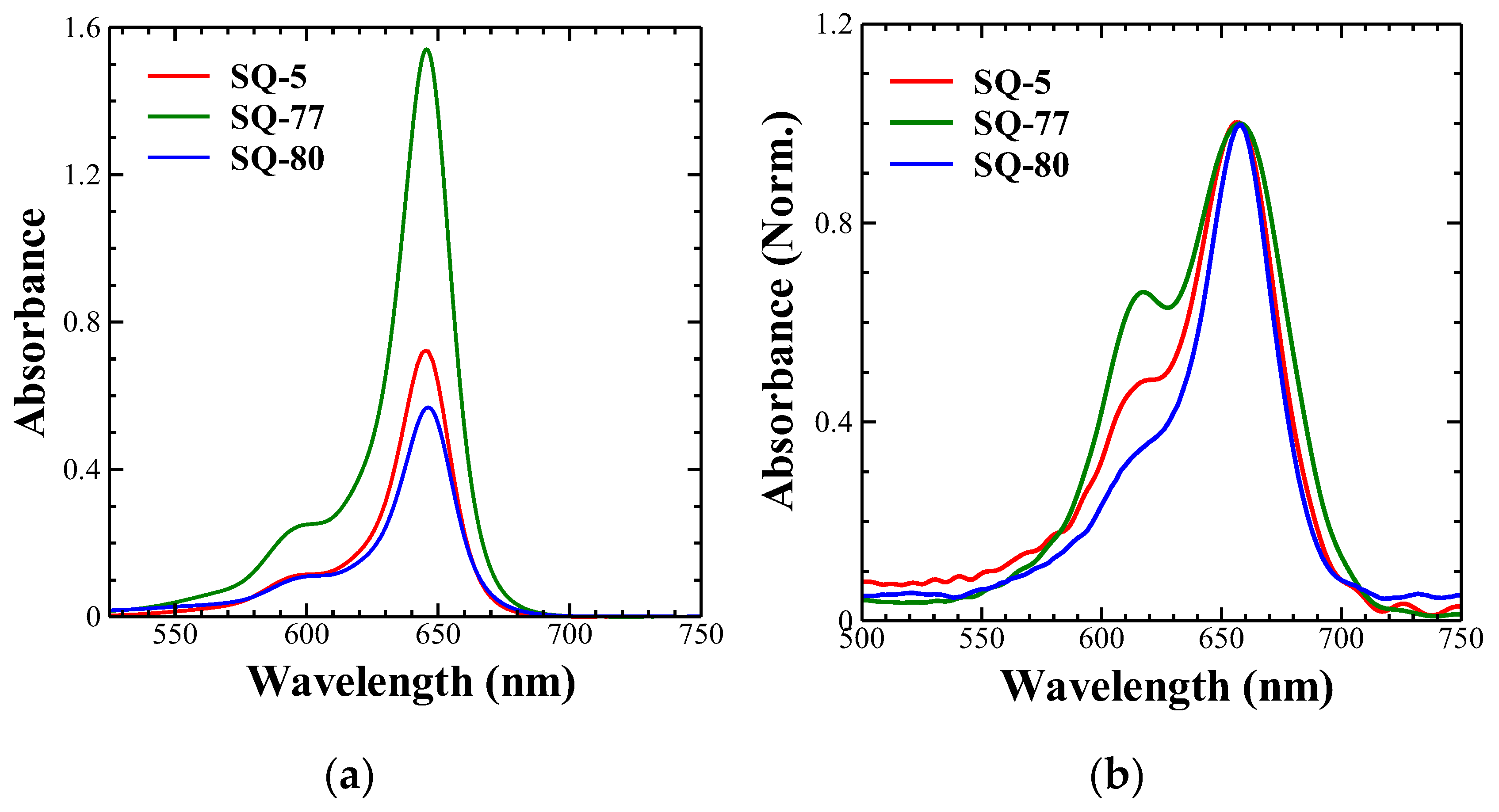

3.1. Electronic Absorption Spectra

3.2. Adsorption of Dye Molecules on TiO2

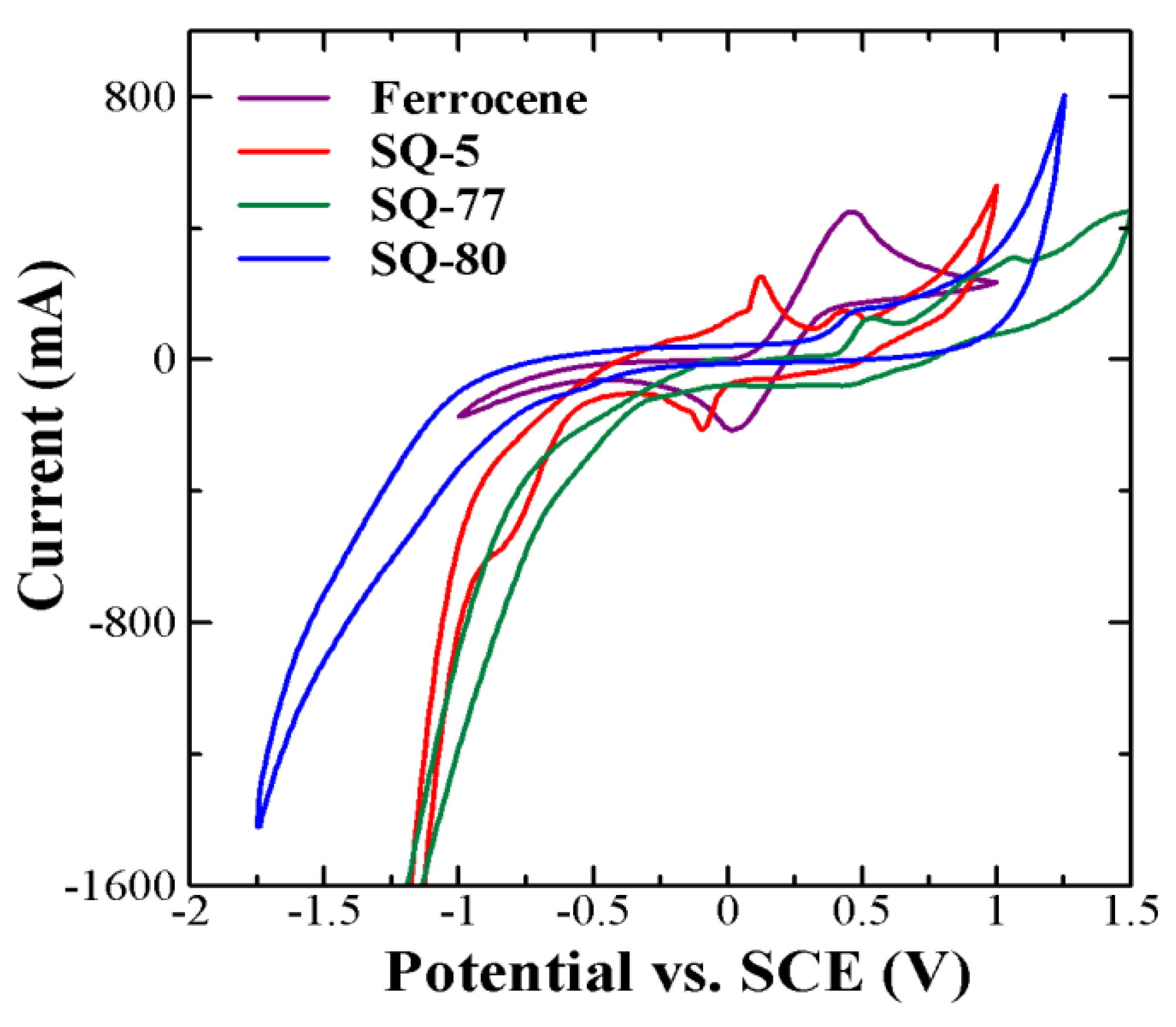

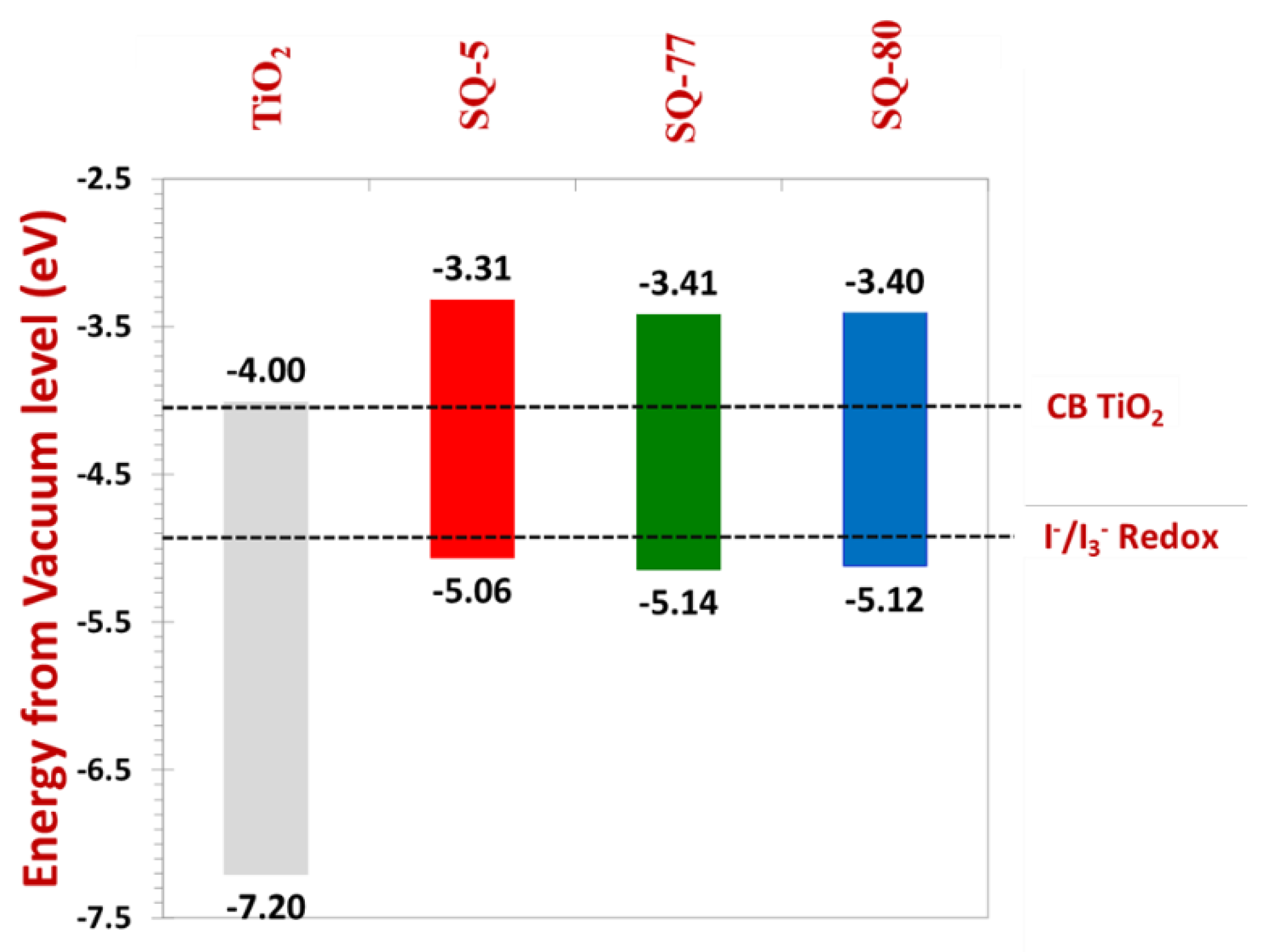

3.3. Cyclic Voltammetry

3.4. Energy Band Diagram

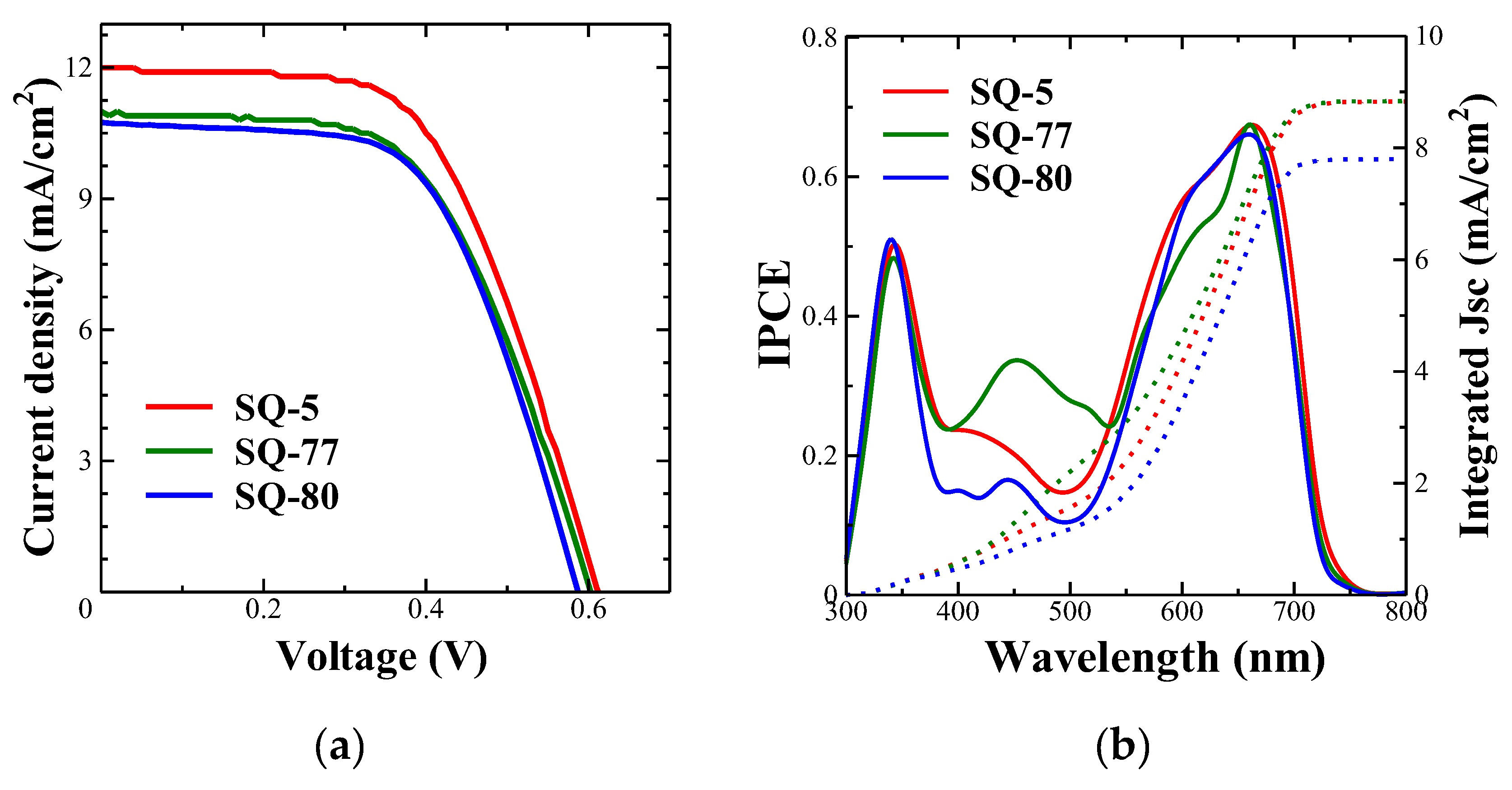

3.5. Photovoltaic Characterization

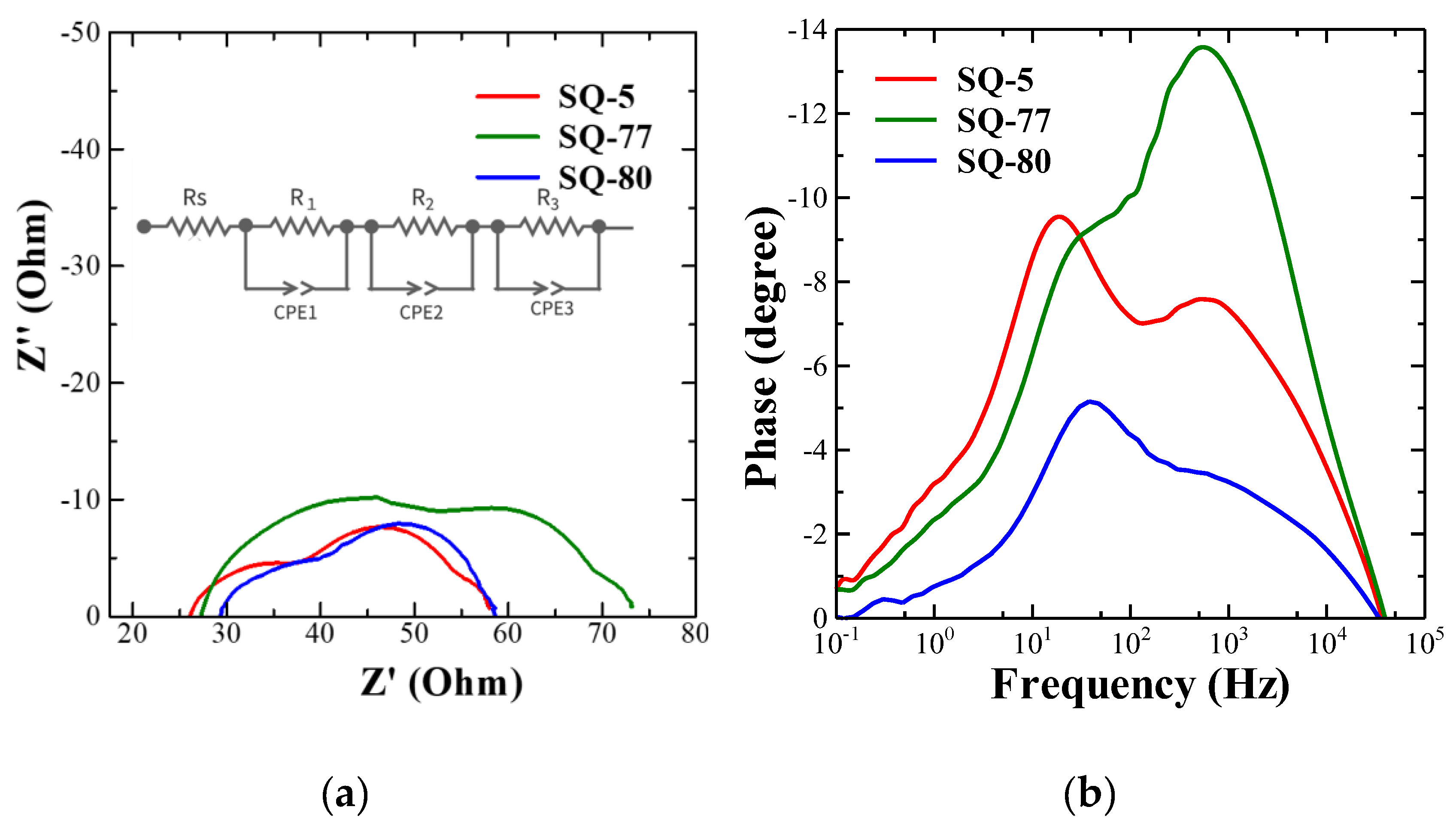

3.6. Electrochemical Impedance Spectra

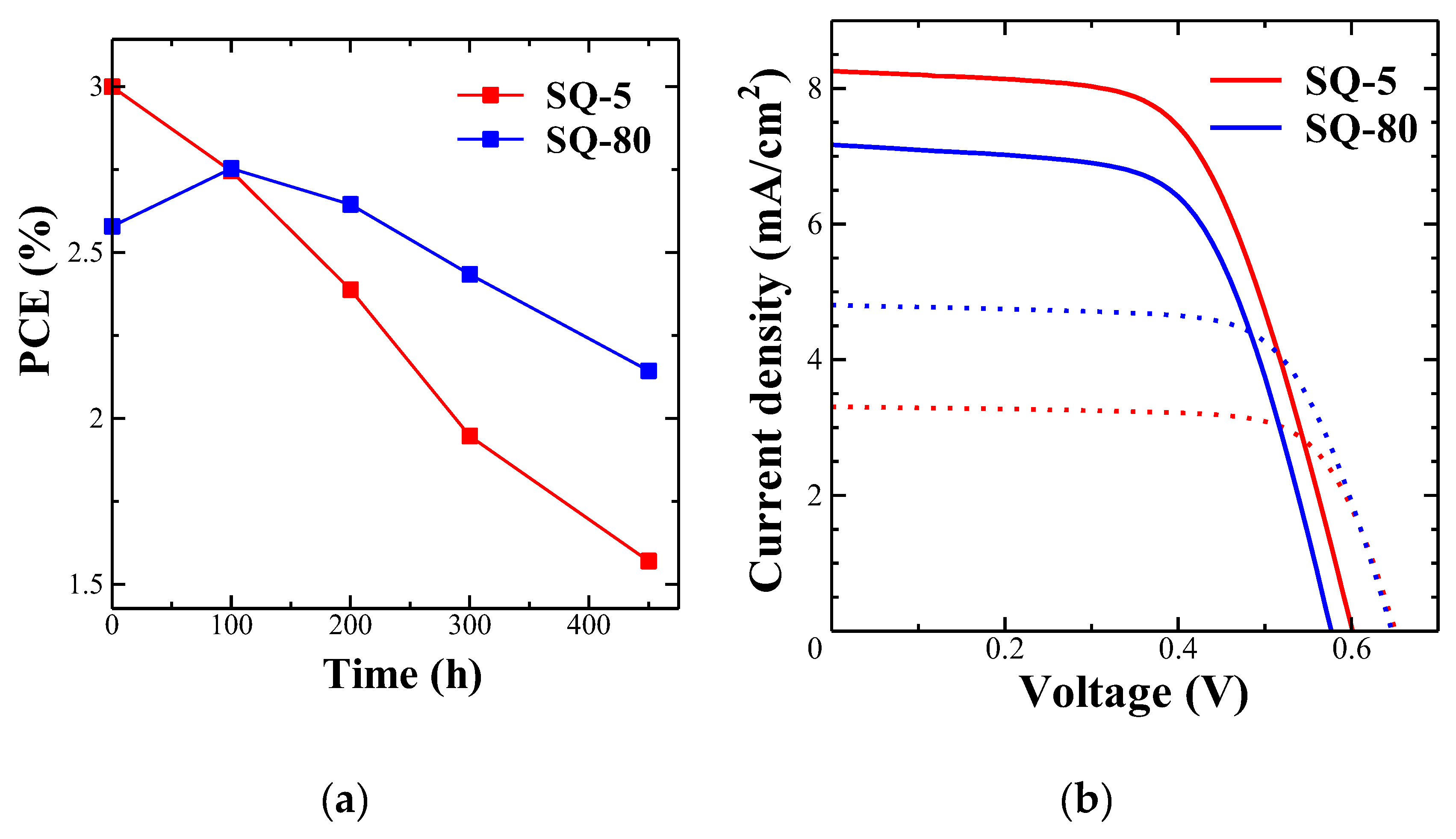

3.7. Relative Durability of DSSCs

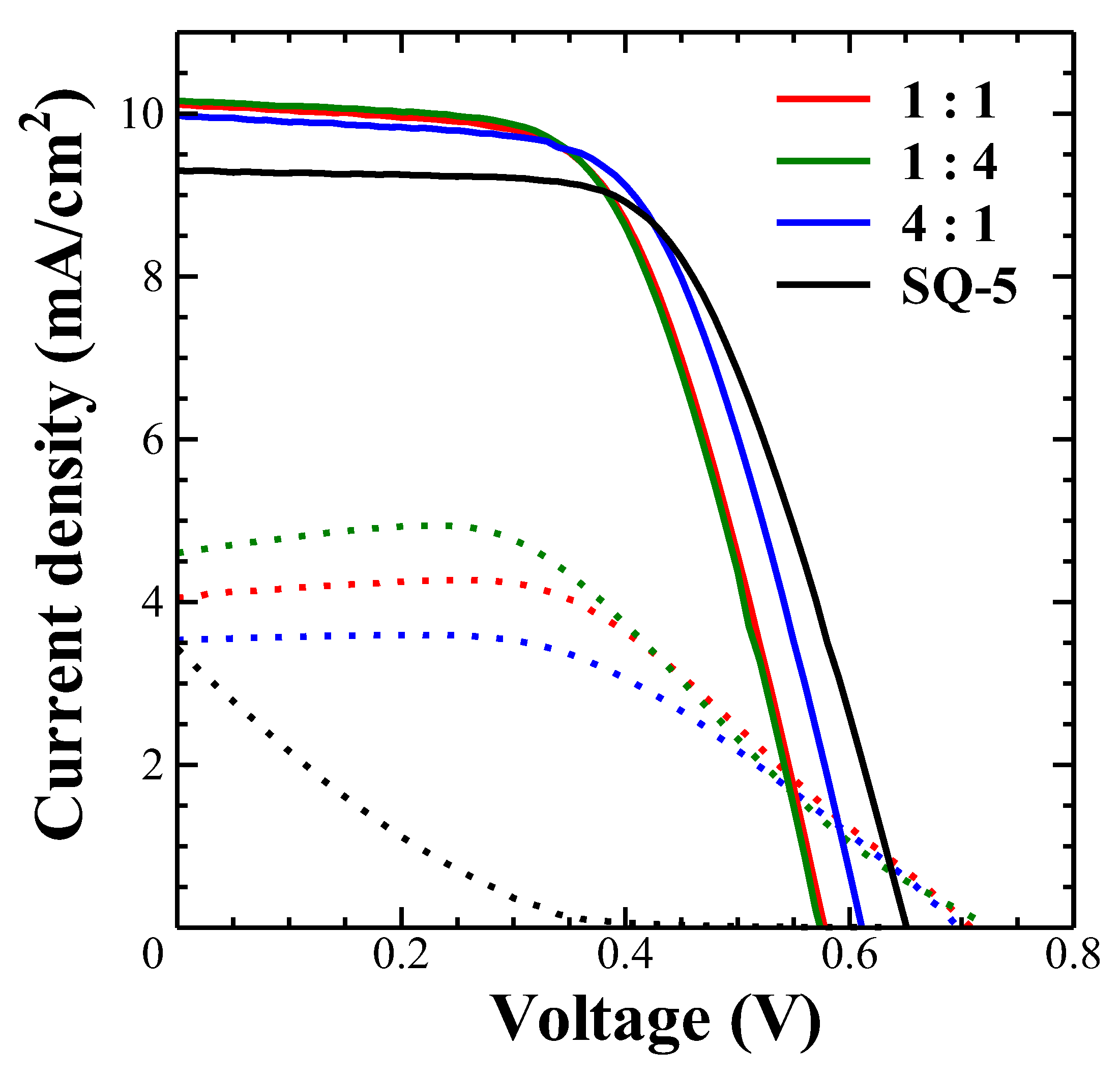

3.8. Verification of Electrolyte Functionality by Mixture of SQ-77 and SQ-80 Dyes

4. Conclusions

References

- 1. REN21. Renewables 2023 Global Status Report Collection, Global Overview.

- Deng, R.; Chang, N. L.; Ouyang, Z.; Chong, C. M. A Techno-Economic Review of Silicon Photovoltaic Module Recycling. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 2019, 109, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkonen, M.; Talebi, P.; Zhou, J.; Asgari, S.; Soomro, S. A.; Elsehrawy, F.; Halme, J.; Ahmad, S.; Hagfeldt, A.; Hashmi, S. G. Advanced Research Trends in Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Journal of Materials Chemistry A. 2021, 9, 10527–10545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Wang, J.; Jiao, J.; Huang, L.; Tang, J. Recent Advances of Polymer Acceptors for High-Performance Organic Solar Cells. Journal of Materials Chemistry C. 2019, 8, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, H.; Yan, H. Large-Area Perovskite Solar Cells-a Review of Recent Progress and Issues. RSC Advances. 2018, 8, 10489–10508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Regan, B.; Grätzel, M. A Low-Cost, High-Efficiency Solar Cell Based on Dye-Sensitized Colloidal TiO2 Films. Nature 1991, 353, 737–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddah, H. A.; Berry, V.; Behura, S. K. Biomolecular Photosensitizers for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells: Recent Developments and Critical Insights. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 2020, 121, 109678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bella, F.; Gerbaldi, C.; Barolo, C.; Grätzel, M. Aqueous Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Chemical Society Reviews. 2015, 44, 3431–3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, X.; Cao, D.; Yin, H.; Li, X.; Cheng, P.; Mi, B.; Gao, Z.; Deng, W. In Situ Preparation of Hierarchically Structured Dual-Layer TiO2 Films by E-Spray Method for Efficient Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Org. Electron. 2017, 49, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, M. L.; Dessì, A.; Zani, L.; Maranghi, S.; Mohammadpourasl, S.; Calamante, M.; Mordini, A.; Basosi, R.; Reginato, G.; Sinicropi, A. Combined LCA and Green Metrics Approach for the Sustainability Assessment of an Organic Dye Synthesis on Lab Scale. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaels, H.; Rinderle, M.; Freitag, R.; Benesperi, I.; Edvinsson, T.; Socher, R.; Gagliardi, A.; Freitag, M. Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells under Ambient Light Powering Machine Learning: Towards Autonomous Smart Sensors for the Internet of Things. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 2895–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Islam, A.; Chen, H.; Malapaka, C.; Chiranjeevi, B.; Zhang, S.; Yang, X.; Yanagida, M. High-Efficiency Dye-Sensitized Solar Cell with a Novel Co-Adsorbent. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 6057–6060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S. H.; Jeong, M. J.; Eom, Y. K.; Choi, I. T.; Kwon, S. M.; Yoo, Y.; Kim, J.; Kwon, J.; Park, J. H.; Kim, H. K. Porphyrin Sensitizers with Donor Structural Engineering for Superior Performance Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells and Tandem Solar Cells for Water Splitting Applications. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017, 7, 1602117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, S.; Yella, A.; Gao, P.; Humphry-Baker, R.; Curchod, B. F. E.; Ashari-Astani, N.; Tavernelli, I.; Rothlisberger, U.; Nazeeruddin, M. K.; Grätzel, M. Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells with 13% Efficiency Achieved through the Molecular Engineering of Porphyrin Sensitizers. Nat. Chem. 2014, 6, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakiage, K.; Aoyama, Y.; Yano, T.; Oya, K.; Fujisawa, J. I.; Hanaya, M. Highly-Efficient Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells with Collaborative Sensitization by Silyl-Anchor and Carboxy-Anchor Dyes. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 15894–15897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauri, L.; Colombo, A.; Dragonetti, C.; Roberto, D.; Fagnani, F. Recent Investigations on Thiocyanate-Free Ruthenium(II) 2,2′-Bipyridyl Complexes for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Molecules. 2021, 26, 7638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang Quang, L. N.; Kaliamurthy, A. K.; Hao, N. H. Co-Sensitization of Metal Based N719 and Metal Free D35 Dyes: An Effective Strategy to Improve the Performance of DSSC. Opt. Mater. (Amst). 2021, 111, 110589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmorsy, M. R.; Su, R.; Abdel-Latif, E.; Badawy, S. A.; El-Shafei, A.; Fadda, A. A. New Cyanoacetanilides Based Dyes as Effective Co-Sensitizers for DSSCs Sensitized with Ruthenium (II) Complex (HD-2). J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2020, 31, 7981–7990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younas, M.; Harrabi, K. Performance Enhancement of Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells via Co-Sensitization of Ruthenium (II) Based N749 Dye and Organic Sensitizer RK1. Sol. Energy 2020, 203, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 20. Singh A, Singh AK, Dixit R, Vanka K, Krishnamoorthy K, Nithyanandhan J. ACS Appl. Energy Mater, 1461.

- Elmorsy, M. R.; Badawy, S. A.; Alzahrani, A. Y. A.; El-Rayyes, A. Molecular Design and Synthesis of Acetohydrazonoyl Cyanide Structures as Efficient Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells with Enhancement of the Performance of the Standard N-719 Dye upon Co-Sensitization. Opt. Mater. (Amst). 2023, 135, 113359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaoğlan, G. K.; Hışır, A.; Maden, Y. E.; Karakuş, M. Ö.; Koca, A. Synthesis, Characterization, Electrochemical, Spectroelectrochemical and Dye-Sensitized Solar Cell Properties of Phthalocyanines Containing Carboxylic Acid Anchoring Groups as Photosensitizer. Dye. Pigment. 2022, August 2022, 110390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koteshwar, D.; Prasanthkumar, S.; Singh, S. P.; Chowdhury, T. H.; Bedja, I.; Islam, A.; Giribabu, L. Effects of Methoxy Group(s) on D-π-A Porphyrin Based DSSCs: Efficiency Enhanced by Co-Sensitization. Mater. Chem. Front. 2022, 6, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Testoff, T. T.; Wang, L.; Zhou, X. Cause, Regulation and Utilization of Dye Aggregation in Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Molecules. 2020, 25, 4478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, L.; Wu, Y.; Jiang, J.; Guo, X.; Heng, P.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J. Rational Design of Phenothiazine-Based Organic Dyes for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells: The Influence of π-Spacers and Intermolecular Aggregation on Their Photovoltaic Performances. J. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124, 9233–9242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A. K.; Maibam, A.; Javaregowda, B. H.; Bisht, R.; Kudlu, A.; Krishnamurty, S.; Krishnamoorthy, K.; Nithyanandhan, J. Unsymmetrical Squaraine Dyes for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells: Position of the Anchoring Group Controls the Orientation and Self-Assembly of Sensitizers on the TiO2 Surface and Modulates Its Flat Band Potential. J. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124, 18436–18451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, M. M.; Vaghasiya, J. V.; Patil, D.; Soni, S. S.; Sekar, N. Synthesis of Novel Colorants for DSSC to Study Effect of Alkyl Chain Length Alteration of Auxiliary Donor on Light to Current Conversion Efficiency. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2019, 377, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, S.; Kurokawa, Y.; Shaban, S.; Pandey, S. S. Squaric Acid Core Substituted Unsymmetrical Squaraine Dyes for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells: Effect of Electron Acceptors on Their Photovoltaic Performance. Colorants 2023, 2, 654–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vats, A. K.; Roy, P.; Tang, L.; Hayase, S.; Pandey, S. S. Unravelling the Bottleneck of Phosphonic Acid Anchoring Groups Aiming toward Enhancing the Stability and Efficiency of Mesoscopic Solar Cells. Front. Chem. Sci. Eng. 2021, Published online 2021, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vats, A. K.; Pradhan, A.; Hayase, S.; Pandey, S. S. Synthesis, Photophysical Characterization and Dye Adsorption Behavior in Unsymmetrical Squaraine Dyes with Varying Anchoring Groups. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2020, 394, 112467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, A.; Sai Kiran, M.; Kapil, G.; Hayase, S.; Pandey, S. S. Synthesis and Photophysical Characterization of Unsymmetrical Squaraine Dyes for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells Utilizing Cobalt Electrolytes. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2018, 1, 4545–4553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butnarasu, C.; Barbero, N.; Viscardi, G.; Visentin, S. Unveiling the Interaction between PDT Active Squaraines with CtDNA: A Spectroscopic Study. Spectrochim. Acta - Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2021, 250, 119224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavileti, S.K.; Bila, G.; Utka, V.; Bila, E.; Kato, T.; Bilyy, R.; Pandey, S.S. ACS Appl Bio Mater. 2024, 7, 416–428.

- Yang, D.; Jiao, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhuang, T.; Yang, L.; Lu, Z.; Pu, X.; Sasabe, H.; Kido, J. Two Different Donor Subunits Substituted Unsymmetrical Squaraines for Solution-Processed Small Molecule Organic Solar Cells. Org. Electron. 2016, 32, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananda Rao, B.; Kim, H.; Son, Y. A. Synthesis of Near-Infrared Absorbing Pyrylium-Squaraine Dye for Selective Detection of Hg2+. Sensors Actuators, B Chem. 2013, 188, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, B.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, W.; Liu, X.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, N.; Wang, F.; Shangguan, D. Dicyanomethylene-Functionalized Squaraine as a Highly Selective Probe for Parallel G-Quadruplexes. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 7063–7070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, K.; Kurokawa, Y.; Mavileti, S. K.; Pandey, S. S. Design, Synthesis, and Photophysical Characterization of Multifunctional Far-Red Squaraine Dyes for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Phys. Status Solidi Appl. Mater. Sci. 2023, 220, 2300254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, W.; Lai, W. F.; Weissleder, R.; Tung, C. H. High Efficiency Synthesis of a Bioconjugatable Near-Infrared Fluorochrome. Bioconjug. Chem. 2003, 14, 1048–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S. S.; Inoue, T.; Fujikawa, N.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Hayase, S. Substituent Effect in Direct Ring Functionalized Squaraine Dyes on near Infra-Red Sensitization of Nanocrystalline TiO2 for Molecular Photovoltaics. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2010, 214, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Periyasamy, K.; Sakthivel, P.; Venkatesh, G.; Vennila, P.; Sheena Mary, Y. Synthesis and Design of Carbazole-Based Organic Sensitizers for DSSCs Applications: Experimental and Theoretical Approaches. Chem. Pap. 2024, 78, 447–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Behera, R. K.; Behera, P. K.; Mishra, B. K.; Behera, G. B. Cyanines during the 1990s: A Review. Chem. Rev. 2000, 100, 1973–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yum, J. H.; Moon, S. J.; Humphry-Baker, R.; Walter, P.; Geiger, T.; Nüesch, F.; Grätzel, M.; Nazeeruddin, M. D. K. Effect of Coadsorbent on the Photovoltaic Performance of Squaraine Sensitized Nanocrystalline Solar Cells. Nanotechnology 2008, 19, 424005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, B.; Park, M. S.; Kim, K. Ferrocene and Cobaltocene Derivatives for Non-Aqueous Redox Flow Batteries. ChemSusChem 2015, 8, 310–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogomi, Y.; Kato, T.; Hayase, S. Dye Sensitized Solar Cells Consisting of Ionic Liquid and Solidification. J. Photopolym. Sci. Technol. 2006, 19, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, T.; Fujikawa, N.; Ogomi, Y.; Pandey, S. S.; Ma, T.; Hayase, S. Design of Far-Red Sensitizing Squaraine Dyes Aiming towards the Fine Tuning of Dye Molecular Structure. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2016, 16, 3282–3288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khazraji, A. C.; Hotchandani, S.; Das, S.; Kamat, P. V. Controlling Dye (Merocyanine-540) Aggregation on Nanostructured TiO2 Films. An Organized Assembly Approach for Enhancing the Efficiency of Photosensitization. J. Phys. Chem. B 1999, 103, 4693–4700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, P.; Pandey, K.; Yadav, P.; Tripathi, B.; Kumar, M. Impedance Spectroscopic Investigation of the Degraded Dye-Sensitized Solar Cell Due to Ageing. Int. J. Photoenergy 2016, 2016, 8523150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, S.; Ahammad, A. J. S.; Seo, H. W.; Kim, D. M. Electrochemical Impedance Spectra of Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells: Fundamentals and Spreadsheet Calculation. International Journal of Photoenergy. 2014, 2014, 851705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, F.; Lin, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhuang, D.; Liu, Y.; Li, J. Influence of Iodine Concentration on the Photoelectrochemical Performance of Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells Containing Non-Volatile Electrolyte. Electrochim. Acta 2010, 55, 7225–7229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, A.; Anand, V.; Rao, G. M.; Munichandraiah, N. Effect of Iodine Concentration on the Photovoltaic Properties of Dye Sensitized Solar Cells for Various I2/LiI Ratios. Electrochim. Acta 2013, 87, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, J.; Bhattacharya, A.; Kundu, K. K. Relative Standard Electrode Potentials of I3−/I−, I2/I3−, and I2/I− Redox Couples and the Related Formation Constants of I3− in Some Pure and Mixed Dipolar Aprotic Solvents. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1988, 61, 1735–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, I. V.; Iwamoto, R. T. Voltammetric Evaluation of the Stability of Trichloride, Tribromide, and Triiodide Ions in Nitromethane, Acetone, and Acetonitrile. J. Electroanal. Chem. 1964, 7, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dye | λmax (solution) | ε (solution) (dm3.mol-1.cm-1) |

λmax (TiO2) |

Absorption Edge nm (eV) | Aggregation index | Dye loading (nmol/cm2) | Dye desorption rate (nmol/cm2/min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SQ-5 | 646 nm | 1.45 x 105 | 658 nm | 710 nm (1.75 eV) |

0.48 | 29.3 | 5.86 |

| SQ-77 | 646 nm | 3.08 x 105 | 658 nm | 715 nm (1.73 eV) |

0.66 | 54.0 | 6.00 |

| SQ-80 | 646 nm | 1.18 x 105 | 658 nm | 720 nm (1.72 eV) |

0.32 | 35.6 | 2.09 |

| Dye | Jsc (mA/cm2) | Voc (V) | FF | PCE (%) |

| SQ-5 | 12.0 | 0.62 | 0.57 | 4.21 |

| SQ-77 | 11.0 | 0.61 | 0.56 | 3.77 |

| SQ-80 | 10.7 | 0.59 | 0.59 | 3.74 |

| Dye | Rs (Ω) | R1 (Ω) | R2 (Ω) | R3 (Ω) | fp (Hz) | Ʈs (ms) |

| SQ-5 | 27.5 | 9.42 | 20.3 | 1.30 | 18.9 | 8.41 |

| SQ-77 | 24.0 | 26.7 | 18.0 | 3.35 | 30.0 | 5.31 |

| SQ-80 | 29.2 | 12.0 | 16.9 | 0.53 | 37.8 | 4.22 |

| Dye | Time (h) | Jsc (mA/cm2) | Voc (V) | FF | PCE (%) |

| SQ-5 | 0 | 8.26 (± 0.90 ) |

0.61 (± 0.01) |

0.60 (± 0.02) |

3.00 (± 0.23) |

| 450 | 3.31 (± 0.18) |

0.66 (± 0.01) |

0.72 (± 0.002) |

1.57 (± 0.11) |

|

| SQ-80 | 0 | 7.17 (± 0.32) |

0.583 (± 0.005) |

0.618 (± 0.02) |

2.58 (± 0.12) |

| 450 | 4.81 (± 0.46) |

0.65 (± 0.01) |

0.67 (± 0.031) |

2.14 (± 0.14) |

| SQ-77: SQ-80 | I2 and LiI conc. (mM) |

Jsc (mA/cm2) | Voc (V) | FF | PCE (%) |

| 1 : 1 | 50, 100 | 10.1 | 0.58 | 0.59 | 3.48 |

| 1 : 4 | 10.0 | 0.62 | 0.60 | 3.68 | |

| 4 : 1 | 10.2 | 0.58 | 0.59 | 3.46 | |

| SQ-5 | 9.30 | 0.66 | 0.60 | 3.70 | |

| 1 : 1 | 0, 0 | 4.05 | 0.71 | 0.51 | 1.45 |

| 1 : 4 | 4.60 | 0.73 | 0.45 | 1.52 | |

| 4 : 1 | 3.87 | 0.70 | 0.52 | 1.41 | |

| SQ-5 | 3.43 | 0.64 | 0.11 | 0.24 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).