Submitted:

17 April 2024

Posted:

18 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Membrane Preparation

2.3. Pure Water Flux and Wettability

2.4. Separation Performances of Membranes and Antifouling Test

2.5. Porosity

2.6. Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- N. Salim, A. 1. N. Salim, A. Siddiqa, S. Shahida, and S. Qaisar. PVDF based Nanocomposite Membranes: Application towards Wastewater treatment. Madridge J Nanotechnol Nanosci. [CrossRef]

- S. Kalogirou, Seawater desalination using renewable energy sources. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci., 2005, 31, 242–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 3. N. L. Le and S. P. Nunes. Materials and membrane technologies for water and energy sustainability. Sustain Mater Techno., 2016, 7, 1–28. . https://doi.org/. [CrossRef]

- C. Okello, B. Tomasello, N. Greggio, N. Wambiji, and M. Antonellini. Impact of Population Growth and Climate Change on the Freshwater Resources of Lamu Island, Kenya. Water, 2015, 7, 1264–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. K. Daud, M. 5. M. K. Daud, M. Nafees, S. Ali, M. Rizwan, R. Ahmad Bajwa, M.B.Shakoor, M. Umair Arshad, S. Ali Shahid Chatha, F.Deeba, W. Murad, F. Malook, S. J. Zhu. Drinking Water Quality Status and Contamination in Pakistan. Int. J. Biomed. Res,. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Iqbal, M. Imran, T. Hussain, M. Asif Naeem, A. A. Al-Kahtani, G. M. Shah, S. Ahmad, A. Farooq, M. Rizwan, A. Majeed, A. Rehman Khan, S. Ali. Effective sequestration of Congo red dye with ZnO/cotton stalks biochar nanocomposite: MODELING, reusability and stability. J. Saudi Chem. Soc., 2021, 25, 101176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Mao, T. Yan, J. Shen, J. Zhang, and D. Zhang. Capacitive Removal of Heavy Metal Ions from Wastewater via an Electro-Adsorption and Electro-Reaction Coupling Process. Environ. Sci. Technol, 2021, 55, 3333–3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- T. Haneef, B. Nur Karahan, Y. Akdag, M. Fakioglu, S. Korkut, H. Guven, M.E. Ersahin, H. Ozgun. Removal of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) from Produced Water by Ferrate (VI) Oxidation. Water, 2020, 12, 3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. Nur Karahan, Y. Akdag, M. Fakioglu, S. Korkut, Huseyin Guven a, Mustafa E. Ersahin, H. Ozgun. Coupling ozonation with hydrogen peroxide and chemically enhanced primary treatment for advanced treatment of grey water. J. Environ. Chem. Eng., 2023, 11, 110116–110116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Cristina, P. Chelme-Ayala, and Mohamed Gamal El-Din. Sludge-based activated biochar for adsorption treatment of real oil sands process water: Selectivity of naphthenic acids, reusability of spent biochar, leaching potential, and acute toxicity removal. J. Chem. Eng, 2023, 463, 142329–142329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Alrashedi,H. Kochkar, G. Berhault, M. Younas, A. Ali, N.A. Alomair, R. Hamdi, S.A. Abubshait, O. Alagha, M.F. Gondal, M. Haroun, C. Tratrat. Enhancement of the photocatalytic response of Cu-doped TiO2 nanotubes induced by the addition of strontium. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A, 2022, 428, 113858–113858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oulkhir, K. Lyamlouli, M. Danouche, and R. Benhida. Biosorption of a cationic dye using raw and functionalized Chenopodium quinoa pericarp biomass after saponin glycosides extraction. J. Environ. Chem. Eng., 2023, 11, 110419–110419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Li, X. Zhang, X. Liang, W. Liu, K. Guo, Z. Zhang, S. Wang, Y. Xing, Z. Li, J. Li, H. Wang. Simultaneous removal and conversion of silver ions from wastewater into antibacterial material through selective chemical precipitation. Arab. J. Chem., 2023, 16, 104836–104836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. F. Aboelfetoh, A. E. Aboubaraka, and E.-Z. M. Ebeid. Binary coagulation system (graphene oxide/chitosan) for polluted surface water treatment,” Environ. Manag., 2021, 288, 112481. [CrossRef]

- Y. Dong, H. 15. Y. Dong, H. Wu, F. Yang, and S. Gray. Cost and efficiency perspectives of ceramic membranes for water treatment. Water Res. 1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Zuo, K. Wang, R.M. DuChanois, Q. Fang, E.M. Deemer, X.Huang, R. Xin, I.,A. Said, Z.He, Y. Feng, W. Shane Walker, J. Lou, M. Elimelech,, Q. Li. Selective membranes in water and wastewater treatment: Role of advanced materials. Mater.Today, 2021, 50, 516–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Z. He, Y. Li, G. Liu, C. Wang, S. Chang, J. Hu, X. Zhang, Y.Vasseghian. Fabrication of a novel hollow wood fiber membrane decorated with halloysite and metal-organic frameworks nanoparticles for sustainable water treatment. Ind. Crops and Products, 2023, 202, 117082–117082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Daramola, E. Aransiola, and T. Ojumu. Potential Applications of Zeolite Membranes in Reaction Coupling Separation Processes. Mater., 2012, 5, 2101–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Mohammed, M. Soliman, S. Kandil, S. Ebrahim, and M. Khalil. Tailoring nanocomposite membranes of cellulose acetate/silica nanoparticles for desalination. J. Materiomics, 2022, 8, 1122–1130. [CrossRef]

- T. Guo-quan, L. Shengzhe, H. Yuxiao, L. Zhuo, L. Jie, L. Xin, L. Weiyi. Fabrication of chitosan membranes via aqueous phase separation: Comparing the use of acidic and alkaline dope solutions. J. Membr. Sci., 2022, 646, 120256–120256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Wei, R. Chen, and G. Li. Effect of chemical structure on the performance of sulfonated poly (arylene ether sulfone) as proton exchange membrane. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2015, 40, 14392–14397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Kwong, A. Abdelrasoul, and H. Doan. Controlling polysulfone (PSF) fiber diameter and membrane morphology for an enhanced ultrafiltration performance using heat treatment. Results Mater, 2019, 2, 100021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Amid, N. Nabian, and M. Delavar. Fabrication of polycarbonate ultrafiltration mixed matrix membranes including modified halloysite nanotubes and graphene oxide nanosheets for olive oil/water emulsion separation. Sep. Pur. Tech., 2020, 251, 117332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Z. Wu, X. Ji, Q. He, H. Gu, W. Zhang, and Z. Deng. Nanocelluloses fine-tuned polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane for enhanced separation and antifouling. Carbohydr. Polym, 2024, 323, 121383–121383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

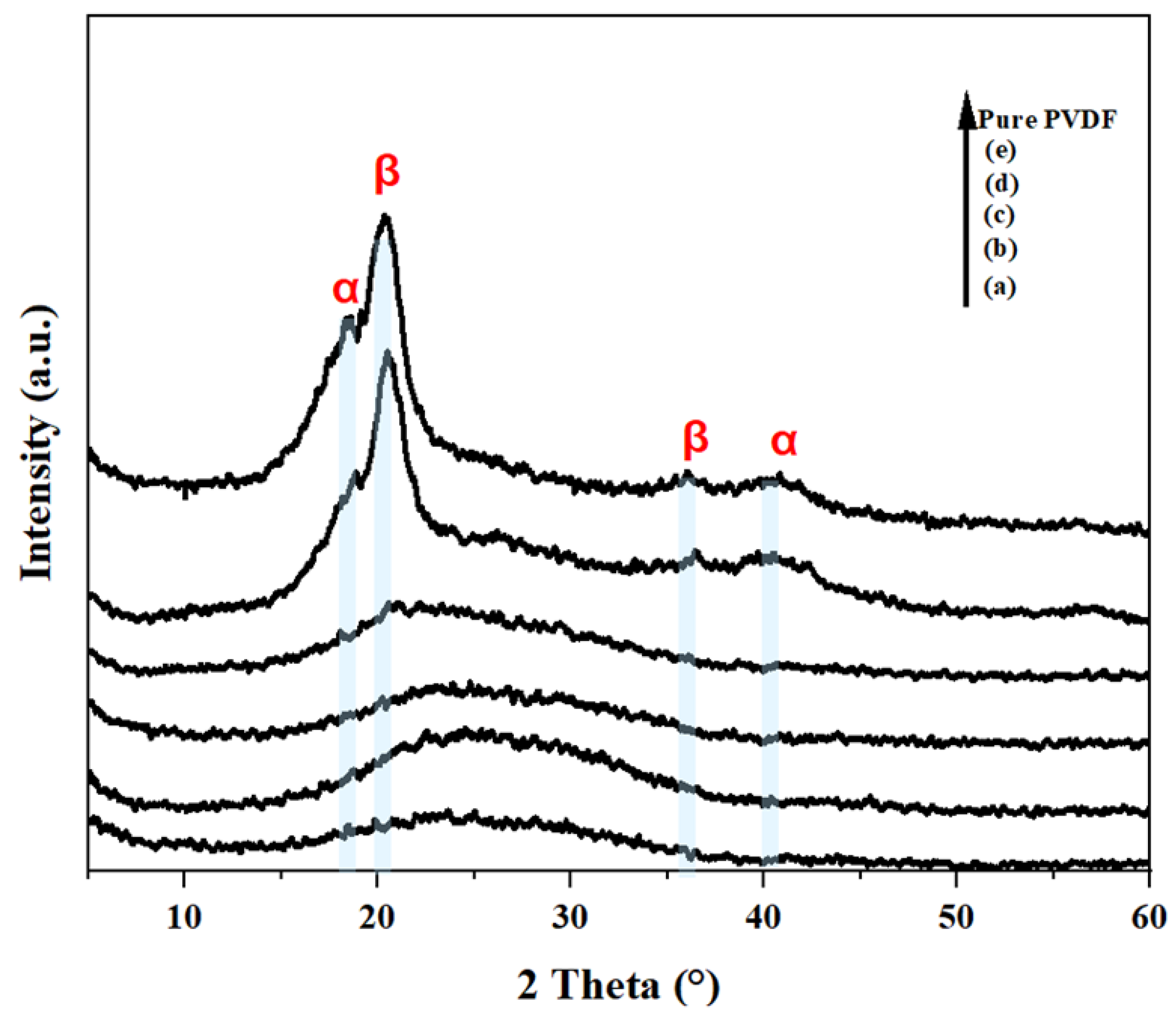

- N. Arshad, M. H. M. Wahid, M. Rusop, W. H. A. Majid, R. H. Y. Subban, and M. D. Rozana. Dielectric and Structural Properties of Poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) and Poly(vinylidene fluoride-trifluoroethylene) (PVDF-TrFE) Filled with Magnesium Oxide Nanofillers. J. Nanomater., 2019, 2019, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S. Haiting, W. Wei, P. Xiaoyuan, T. Kunyue, H. Yanli, X. Zhiwei, D. Hui, Q. Xiaoming. Improvement of PVDF nanofiltration membrane potential, separation and anti-fouling performance by electret treatment. Sci. Total Environ., 2020, 722, 137816–137816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. Li, I. Katsouras, C. Piliego, G. Glasser, I. Lieberwirth, P. W. M. Blomb, D..M. de Leeuw. Controlling the microstructure of poly(vinylidene-fluoride) (PVDF) thin films for microelectronics. J. Mater. Chem. C, 2013, 1, 7695–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- X. Wang, D. Chen, T. He, Y.Zhou, L. Tian, Z. Wang, Z. Cui. Preparation of Lateral Flow PVDF Membrane via Combined Vapor- and Non-Solvent-Induced Phase Separation (V-NIPS). Membr. J., 2023, 13, 91–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. Amini, S. A. Haddadi, S. Ghaderi, A. Ramazani, and Mohammad Hassan Ansarizadeh. Preparation and characterization of PVDF/Starch nanocomposite nanofibers using electrospinning method. Mater. Today Proc, 2018, 5, 15613–15619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Zhang, Y. Yang,Z. Sun, D. Zhao, Y. Gao, T. Shen, Y. Li, Z. Xie, Y.Huo, H. Li. Ag@BiOBr/PVDF photocatalytic membrane for remarkable BSA anti-fouling performance and insight of mechanism. J. Membr. Sci., 2023, 677, 121611–121611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Jiang, B. Ma, C. Yang, X. Duan, and Q. Tang. Fabrication of anti-fouling and photo-cleaning PVDF microfiltration membranes embedded with N-TiO2 photocatalysts. Sep. Purif. Technol., 2022, 298, 121673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Lik, C. C. Chou, and J. Chen. Hybrid model based expected improvement control for cyclical operation of membrane microfiltration processes. Chem. Eng. Sci, 2017, 166, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Sun, J. Liu, H. Chu, and B. Dong. Pretreatment and Membrane Hydrophilic Modification to Reduce Membrane Fouling. Membranes, 2013, 3, 226–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Zhang, L. Wu, F. Deng, D. Zhao, C. Zhang, and C. Zhang. Hydrophilic modification of PVDF porous membrane via a simple dip-coating method in plant tannin solution. RSC Adv., 2016, 6, 71287–71294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Xie, J. Li, T. Sun, W. Shang, W. Dong, M. Li, F. Sun. Hydrophilic modification and anti-fouling properties of PVDF membrane via in situ nano-particle blending. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res., 2018, 25, 25227–25242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- X. Meng, Y. Ji, G. Yu, and Y. Zhai. Preparation and Properties of Polyvinylidene Fluoride Nanocomposite Membranes based on Poly(N-Isopropylacrylamide) Modified Graphene Oxide Nanosheets. Polym., 2019, 11, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R. Gayatri, A. N. Syimir Fizal, E. Yuliwati, S. Hossain, J. Jaafar, M. Zulkifli, W. Taweepreda, A. Naim Ahmad Yahaya. Preparation and Characterization of PVDF–TiO2 Mixed-Matrix Membrane with PVP and PEG as Pore-Forming Agents for BSA Rejection. Nanomater., 2023, 13, 1023–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A. Koriem, M. S. Showman, A.H. El-Shazly, and M.F. Elkady. Cellulose acetate/polyvinylidene fluoride based mixed matrix membranes impregnated with UiO-66 nano-MOF for reverse osmosis desalination. Cellulose, 2022, 30, 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Pang, L. Xin, L. Jian-Sheng, L. Zhuang-Yu, H. Cheng, S. Xiu-Yun, W. Lian-Jun. In situ Preparation and Antifouling Performance of ZrO2/PVDF Hybrid Membrane. Acta Phys. -Chim. Sin., 2013, 29, 2592–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- X. Yue, X. Ji, H. Xu, B. Yang, M. Wang, and Y. Yang. Performance investigation on GO-TiO2/PVDF composite ultrafiltration membrane for slightly polluted groundwater treatment. Energy, 2023, 273, 127215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Alnairat, M. Abu Dalo, R. Abu-Zurayk, S. Abu Mallouh, F. Odeh, and A. Al Bawab. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles as an Effective Antibiofouling Material for Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF) Ultrafiltration Membrane. Polymers, 2021, 13, 3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Chen, Q. C. Chen, Q. Liu, W. Chen, F. Li, G. Xiao, C. Chen, R. Li, J. Zhou. A high absorbent PVDF composite membrane based on β-cyclodextrin and ZIF-8 for rapid removing of heavy metal ions. Separation and Purification Technology, 2022, 292, 120993–120993. [CrossRef]

- J. -F. Li, Z.-L. Xu, H. Yang, L.-Y. Yu, and M. Liu. Effect of TiO2 nanoparticles on the surface morphology and performance of microporous PES membrane. Appl. Surf. Sci., 2009, 255, 4725–4732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Roshani, F. Ardeshiri, M. Peyravi, and M. Jahanshahi. Highly permeable PVDF membrane with PS/ZnO nanocomposite incorporated for distillation process. RSC Adv., 2018, 8, 23499–23515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- X. Cao, J. Ma, X. Shi, and Z. Ren. Effect of TiO2 nanoparticle size on the performance of PVDF membrane. Appl. Surf. Sci., 2006, 253, 2003–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. Ardeshiri, S. Salehi, M. Peyravi, M. Jahanshahi, A. Amiri, and A. Shokuhi Rad. PVDF membrane assisted by modified hydrophobic ZnO nanoparticle for membrane distillation. Asia-Pac. J. Chem. Eng., 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Jiang, R. Simayi, Amatjan Sawut, J. Wang, T. Wu, and X. Gong. Modified β-Cyclodextrin hydrogel for selective adsorption and desorption for cationic dyes. Coll. Surf. Colloid Surf. Physicochem. Eng. Asp, 2023, 661, 130912–130912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Yamasaki, Aya Odamura, Yousuke Makihata, and K. Fukunaga. Preparation of new photo-crosslinked β-cyclodextrin polymer beads. Polymer J., 2017, 49, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Pereva, V. Nikolova, S. Angelova, T. Spassov, and T. Dudev. Water inside β-cyclodextrin cavity: Amount, stability and mechanism of binding. Beilstein J. Org. Chem., 2019, 15, 1592–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J. Xue, J. 50. J. Xue, J. Shen, R. Zhang, F.Wang, S. Liang, X. You, Q. Yu, Y. Hao, Y. Su, Z. Jiang. High-flux nanofiltration membranes prepared with β-cyclodextrin and graphene quantum dots. J. Membr. Sci. 8465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi and, P. Veisi. High adsorption performance of β-cyclodextrin-functionalized multi-walled carbon nanotubes for the removal of organic dyes from water and industrial wastewater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 4634; 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. C. Lee, S. L.Hulu, C. H. Park, C. S. Kim. Enhancing the anti-bacterial activity of nanofibrous polyurethane membranes by incorporating glycyrrhizic acid-conjugated β-Cyclodextrin. Mater. Lett., 2023, 338, 134030–134030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Lv, J. Ma, K. Liu, Y. Jiang, G. Yang, Y. Liu, C. Lin, X. Ye, Y. Shi, M. Liu, L. Chen. Rapid elimination of trace bisphenol pollutants with porous β-cyclodextrin modified cellulose nanofibrous membrane in water: Adsorption behavior and mechanism. J. Hazard. Mater., 2021, 403, 123666–123666. [CrossRef]

- Z. Yang, X. Liu, X. Liu, J. Wu, X. Zhu, Z. Bai, Z. Yu. Preparation of β-cyclodextrin/graphene oxide and its adsorption properties for methylene blue. Colloids Surfaces B., 2021, 200, 111605–111605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Janakiraman, A. Surendran, S. Ghosh, S. Anandhan, and A. Venimadhav. Electroactive poly(vinylidene fluoride) fluoride separator for sodium ion battery with high coulombic efficiency. Solid State Ion., 2016, 292, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Wu, B. Zhou, T. Zhu, J. Shi, Z. Xu, C. Hua, J. Wang. Facile and low-cost approach towards a PVDF ultrafiltration membrane with enhanced hydrophilicity and antifouling performance via graphene oxide/water-bath coagulation. RSC Adv., 2015, 5, 7880–7889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradeep Kumar Mahato, A. K. Seal, Samiran Garain, and S. Sen. Effect of fabrication technique on the crystalline phase and electrical properties of PVDF films. Mater. Sci.-Pol., 2015, 33, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Popa, D. 58. A. Popa, D. Toloman, M. Stan, M. Stefan, T. Radu, G. Vlad, S. Ulinici, G. Baisan, S. Macavei, L. Barbu-Tudoran, O. Pana. Tailoring the RhB removal rate by modifying the PVDF membrane surface through ZnO particles deposition. J.Inorg. Organomet. Polym., 1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Singh, H. Borkar, B. P. Singh, V. N. Singh, and A. Kumar. Ferroelectric polymer-ceramic composite thick films for energy storage applications. AIP Adv., 2014, 4, 087117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, J. Kang, J. Y. Chen, Y. Cao, and M. Xiang. Crystallization behavior, tensile behavior and hydrophilicity of poly(vinylidene fluoride)/poly(vinyl pyrrolidone) blends. Polym. Sci. Ser.A, 2014, 56, 864–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. Eren, E. Eren, M. Guney, Y.C. Jean, and J.Van Horn. Positron annihilation lifetime spectroscopy study of polyvinylpyrrolidone added polyvinylidene fluoride membranes: Investigation of free volume and permeation relationships. J. of Polym. Sci., 2020, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Bai, X. Wang, Y. Zhou, and L. Zhang. Preparation and characterization of poly(vinylidene fluoride) composite membranes blended with nano-crystalline cellulose. Prog. Nat. Sci.: Mater. Int., 2012, 22, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Kamaz, A. Sengupta, A. Gutierrez, Y.-H. Chiao, and R. Wickramasinghe. Surface Modification of PVDF Membranes for Treating Produced Waters by Direct Contact Membrane Distillation. IJERPH, 2019, 16, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. Kartohardjono, G. M. Salsabila, A. Ramadhani, I. Purnawan, and W. Jye Lau. Preparation of PVDF-PVP Composite Membranes for Oily Wastewater Treatment. Membranes, 2023, 13, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- H. M. Zidan, E.M. Abdelrazek, A.M. Abdelghany, and A. E. Tarabiah. Characterization and some physical studies of PVA/PVP filled with MWCNTs. JMST, 2019, 8, 904–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

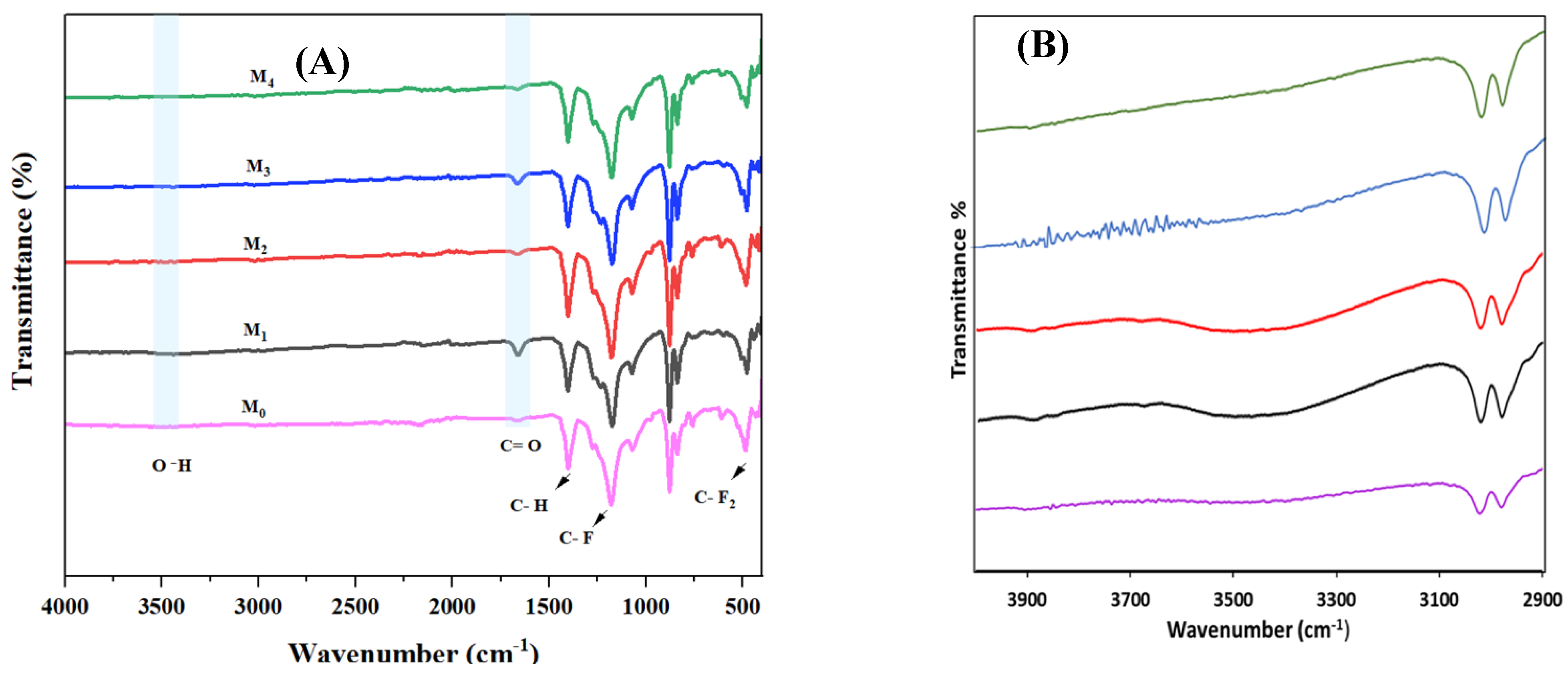

- H. Rachmawati, C. A. Edityaningrum, and R. Mauludin. Molecular Inclusion Complex of Curcumin–β-Cyclodextrin Nanoparticle to Enhance Curcumin Skin Permeability from Hydrophilic Matrix Gel. AAPS Pharm. Sci. Tech, 2013, 14, 1303–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. L. Abarca, F. J. Rodríguez, A. Guarda, M. J. Galotto, and J. E. Bruna. Characterization of beta-cyclodextrin inclusion complexes containing an essential oil component. Food Chem., 2016, 196, 968–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

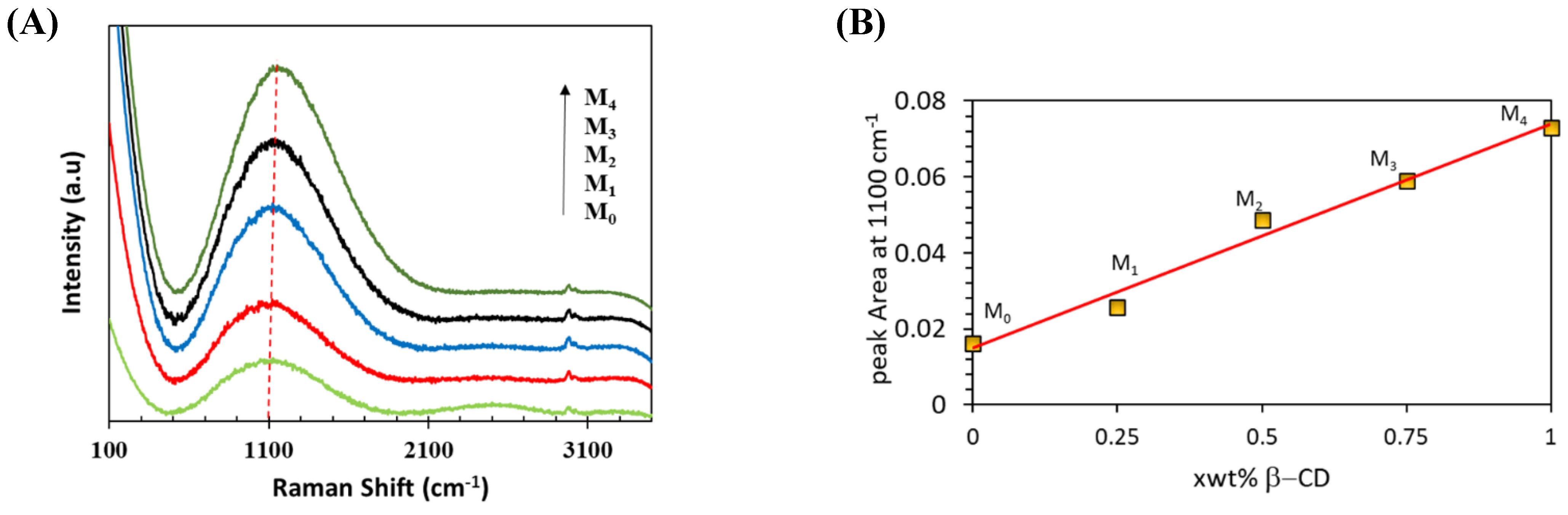

- Tijunelyte, N. Dupont, I. Milosevic, C. Barbey, E. Rinnert, N. Lidgi-Guigui, E. Guenin, M. Lamy de la Chapelle. Investigation of aromatic hydrocarbon inclusion into cyclodextrins by Raman spectroscopy and thermal analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res., 2017, 24, 27077–27089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. McNamara, N. R. Russell. FT-IR and Raman Spectra of a Series of Metallo-Cyclodextrin Complexes. J. Incl. Phenom. and Molec. Reco & Chem., 1991, 10, 485–495.

- A. C. D. Morihama and J. C. Mierzwa. Clay nanoparticles effects on performance and morphology of poly(vinylidene fluoride) membranes. Braz. J. Chem. Eng., 2014, 31, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. C. Sun, W. Kosar, Y. Zhang, and X. Feng. A study of thermodynamics and kinetics pertinent to formation of PVDF membranes by phase inversion. Desalination, 2013, 309, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Bărdacă Urducea, A. C. 72. C. Bărdacă Urducea, A. C. Nechifor, I. A. Dimulescu, O. Oprea, G. Nechifor, E. Eftimie Totu, I. Isildak, P. C. Albu, S. G. Bungău. Control of Nanostructured Polysulfone Membrane Preparation by Phase Inversion Method. Nanomaterials. [CrossRef]

- W. Lu, Z. Yuan, Y. Zhao, H. Zhang, H. Zhang, and X. Li. Porous membranes in secondary battery technologies. Chem. Soc. Rev., 2017, 46, 2199–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- H.-T. Yeo, S.-T. 74. H.-T. Yeo, S.-T. Lee, and M. Han. Role of a Polymer Additive in Casting Solution in Preparation of Phase Inversion Polysulfone Membranes. JCEJ. [CrossRef]

- X. Liu, H. 75. X. Liu, H. Yuan, C. Wang, S. Zhang, L. Zhang, X. Liu, F. Liu, X. Zhu, S.Rohani, C. Ching, J. Lu. A novel PVDF/PFSA-g-GO ultrafiltration membrane with enhanced permeation and antifouling performances. Sep. Pur. Tech. 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Safarpour, A. Khataee, and V. Vatanpour. Preparation of a Novel Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF) Ultrafiltration Membrane Modified with Reduced Graphene Oxide/Titanium Dioxide (TiO2) Nanocomposite with Enhanced Hydrophilicity and Antifouling Properties. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., 2014, 53, 13370–13382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Vatsha, J. C. 77. A. Vatsha, J. C. Ngila, and R. M. Moutloali. Preparation of antifouling polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP 40K) modified polyethersulfone (PES) ultrafiltration (UF) membrane for water purification. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C. [CrossRef]

- M. Baghbanzadeh, D. Rana, T. Matsuura, and C. Q. Lan. Effects of hydrophilic CuO nanoparticles on properties and performance of PVDF VMD membranes. Desalination, 2015, 369, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. S. Rameetse, O. Aberefa, and M. O. Daramola. Effect of Loading and Functionalization of Carbon Nanotube on the Performance of Blended Polysulfone/Polyethersulfone Membrane during Treatment of Wastewater Containing Phenol and Benzene. Membranes, 2020, 10, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Du, P. 80. Y. Du, P. Yang, Z. Mou, Hua Nan-ping, and L. Jiang. Thermal decomposition behaviors of PVP coated on platinum nanoparticles. J. Appl. Polym. Sci., 2005, 99, 23–26. . https://doi.org/. [CrossRef]

- S. F. Mohamad, M. I. 81. S. F. Mohamad, M. I. Mustaqim Azzian, N. M. Hakimi, M. Abdul Manaf, D. Ramesh, T. Asogan, N.H. Ismail, W. Salleh, Physicochemical properties of poly (vinylidene fluoride) membrane grafted poly hydroxyethyl acrylates using radiation-induced graft admicellar polymerization. Mater. Tod. Proceedings, 7853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Z. Yu, Y. Pan, Y. He, G. Zeng, H. Shi, and H. Di. Preparation of a novel anti-fouling β-cyclodextrin–PVDF membrane. RSC Adv., 2015, 5, 51364–51370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

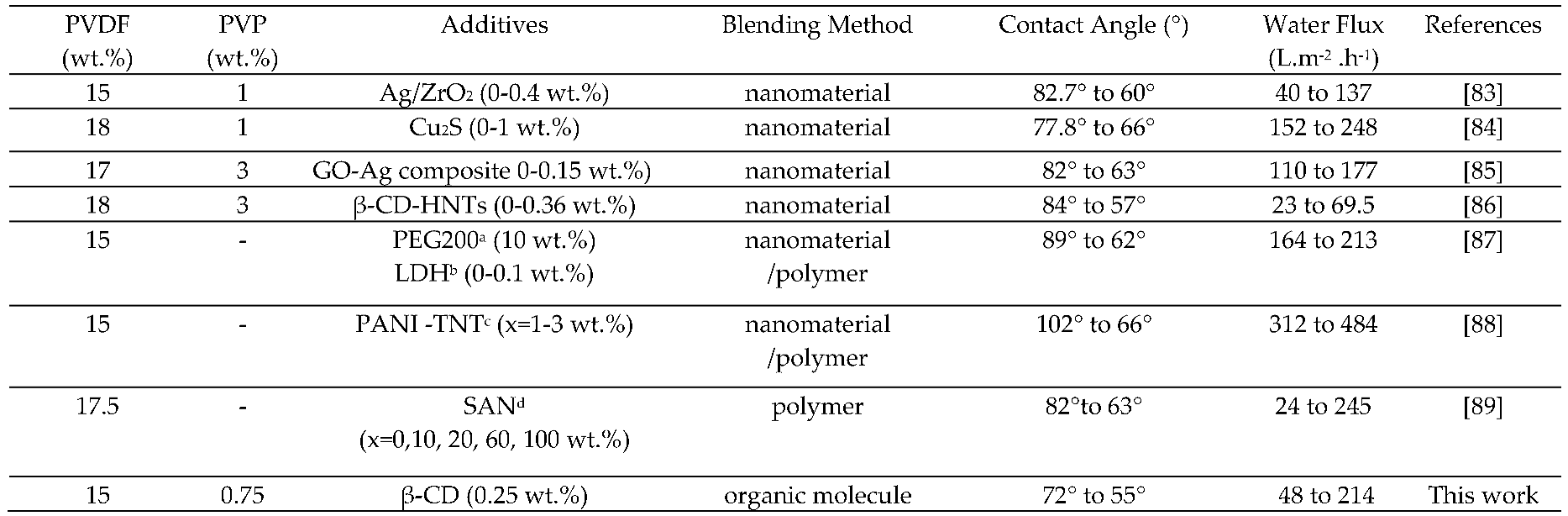

- Y. Lu, Y. Ma, T. Yang, and J. Guo. Hydrophilic modification of PVDF membranes by in situ synthesis of nano-Ag with nano-ZrO2. Green Process. Synth., 2021, 10, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Karimi, A. Khataee, A. Ghadimi, and V. Vatanpour. Ball-milled Cu2S nanoparticles as an efficient additive for modification of the PVDF ultrafiltration membranes: Application to separation of protein and dyes. J. Environ. Chem. Eng., 2021, 9, 105115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Li, X. 85. J. Li, X. Liu, J. Lu, Yudan Chen Wang, G. Li, and L. Liu. Anti-bacterial properties of ultrafiltration membrane modified by graphene oxide with nano-silver particles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. [CrossRef]

- J. Ma, Y. He, G. Zeng, X.Yang, X. Chen, L. Zhou, L. Peng, A. Sengupta. High-flux PVDF membrane incorporated with β-cyclodextrin modified halloysite nanotubes for dye rejection and Cu (II) removal from water. Polym. Adv. Technol., 2018, 29, 2704–2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Abdollahi, A. Heidari, T. Mohammadi, A. Asadi, and Maryam Ahmadzadeh Tofighy. Application of Mg-Al LDH nanoparticles to enhance flux, hydrophilicity and antifouling properties of PVDF ultrafiltration membrane: Experimental and modeling studies. Sep. Purif. Technol., 2021, 257, 117931–117931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Nawaz, M. Umar, I. Nawaz, Q. Zia, M. Tabassum, H, Razzaq, H. Gong, X. Zhao, X. Liu. Photodegradation of textile pollutants by nanocomposite membranes of polyvinylidene fluoride integrated with polyaniline–titanium dioxide nanotubes. J. Chem. Eng, 2021, 419, 129542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Srivastava, G. Arthanareeswaran, N. Anantharaman, V. Starov. Performance of modified poly(vinylidene fluoride) membrane for textile wastewater ultrafiltration. Desalination, 2011, 282, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H, Dalong, Y, Wang, S, Song, S, Liu, Y, Deng. Significantly Enhanced Dielectric Performances and High Thermal Conductivity in Poly(vinylidene fluoride)- Based Composites Enabled by SiC@SiO2 Core–Shell Whiskers Alignment. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2017, 51, 44839–44846. [Google Scholar]

- R. E. Kesting, Synthetic polymeric membranes: A structural perspective. New York: Wiley, 1985.

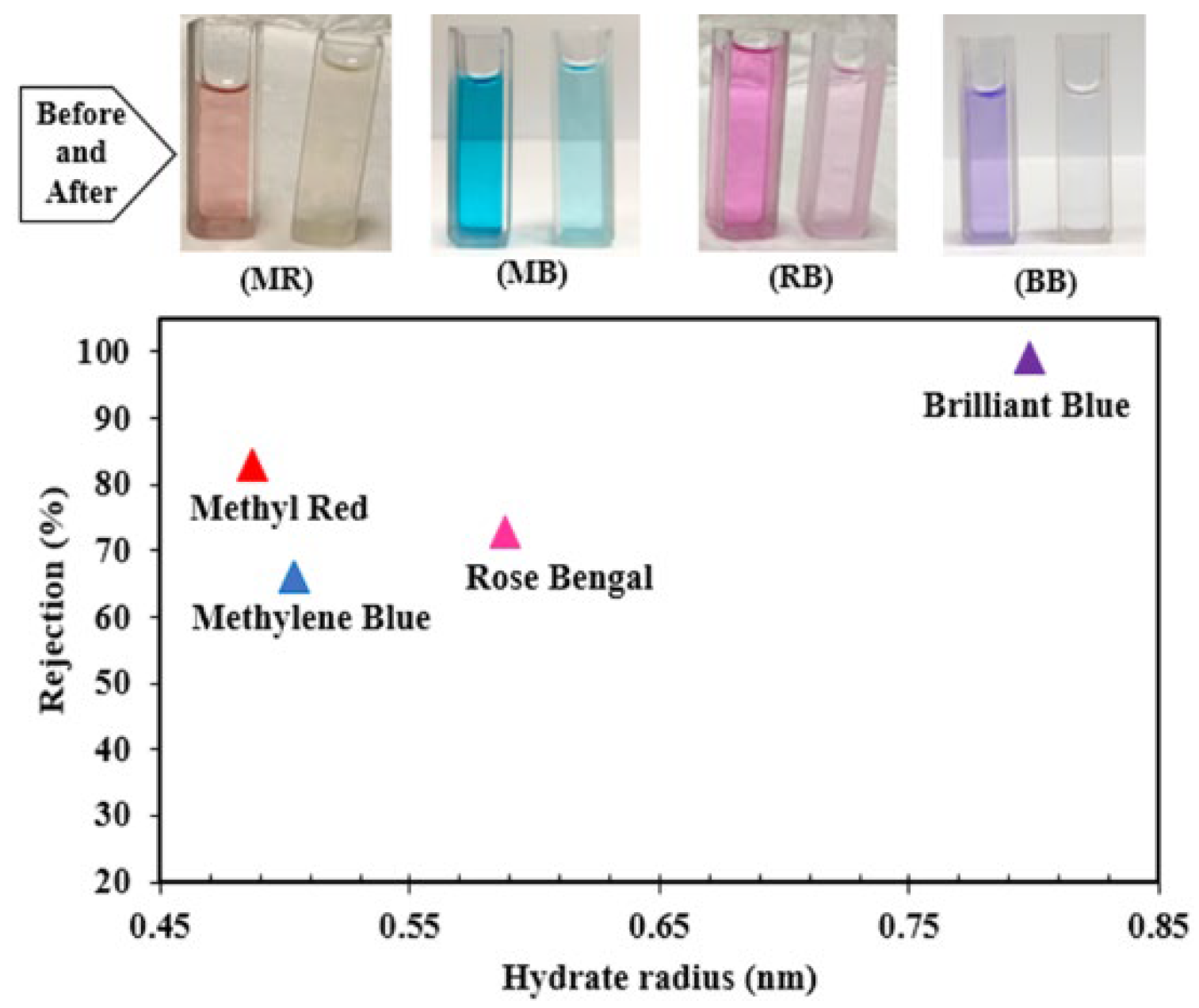

- X. Li, L. Xie, X. Yang, and X. Nie. Adsorption behavior and mechanism of β-cyclodextrin–styrene-based polymer for cationic dyes. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 40321–40329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J. Liu, G. Liu, W. Liu. Preparation of water-soluble β-cyclodextrin/poly(acrylic acid)/graphene oxide nanocomposites as new adsorbents to remove cationic dyes from aqueous solutions. J. Chem. Eng, 2014, 299–308, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Wang, L. Dai, Y. Liu, R. Li, X. Yang, G. Lan, H. Qiu, B. Xu. Adsorption properties of β-cyclodextrin modified hydrogel for methylene blue. Carbohydr. Res., 2021, 501, 108276–108276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V R, K. Murthy, T.A. Prasada Rao, J. Sobhanadri. Dielectric properties of some dyes in the radio-frequency region. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys., 1977, 10, 2405–2409. [Google Scholar]

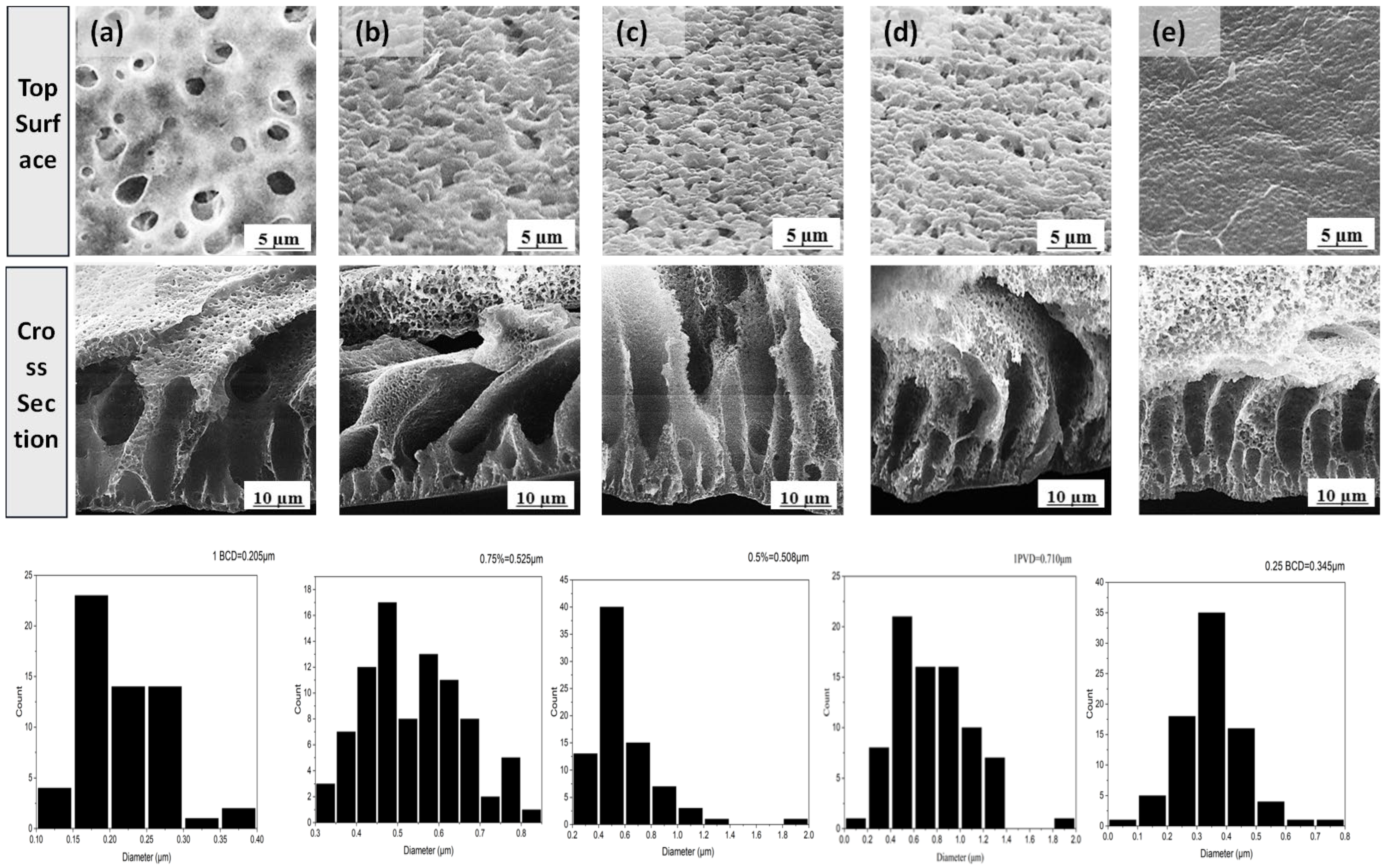

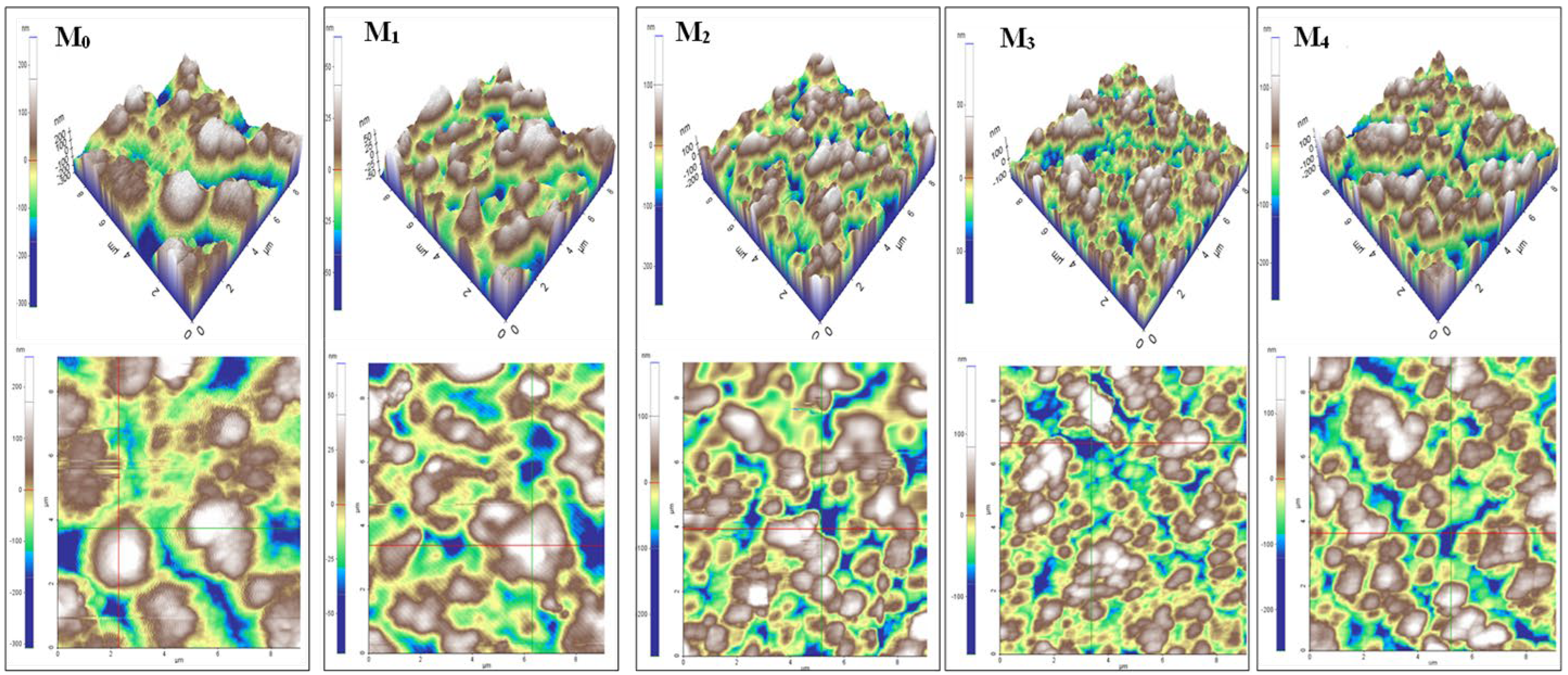

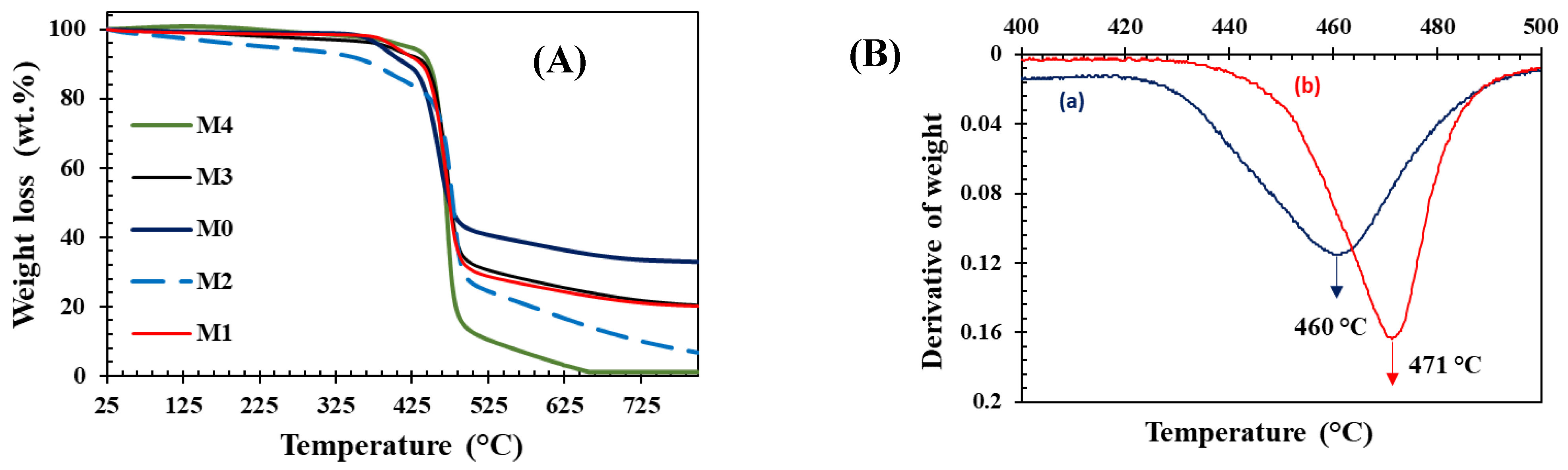

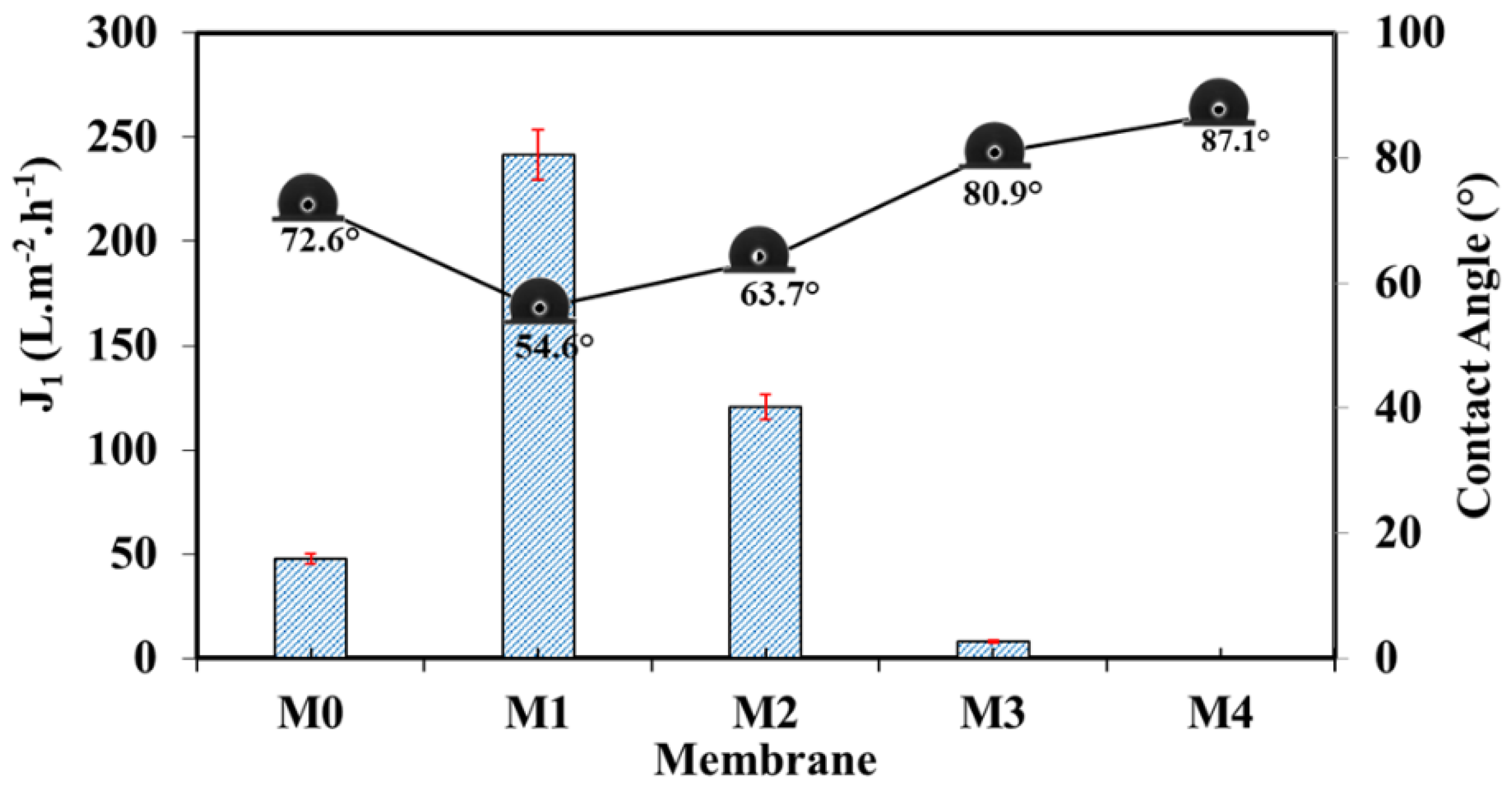

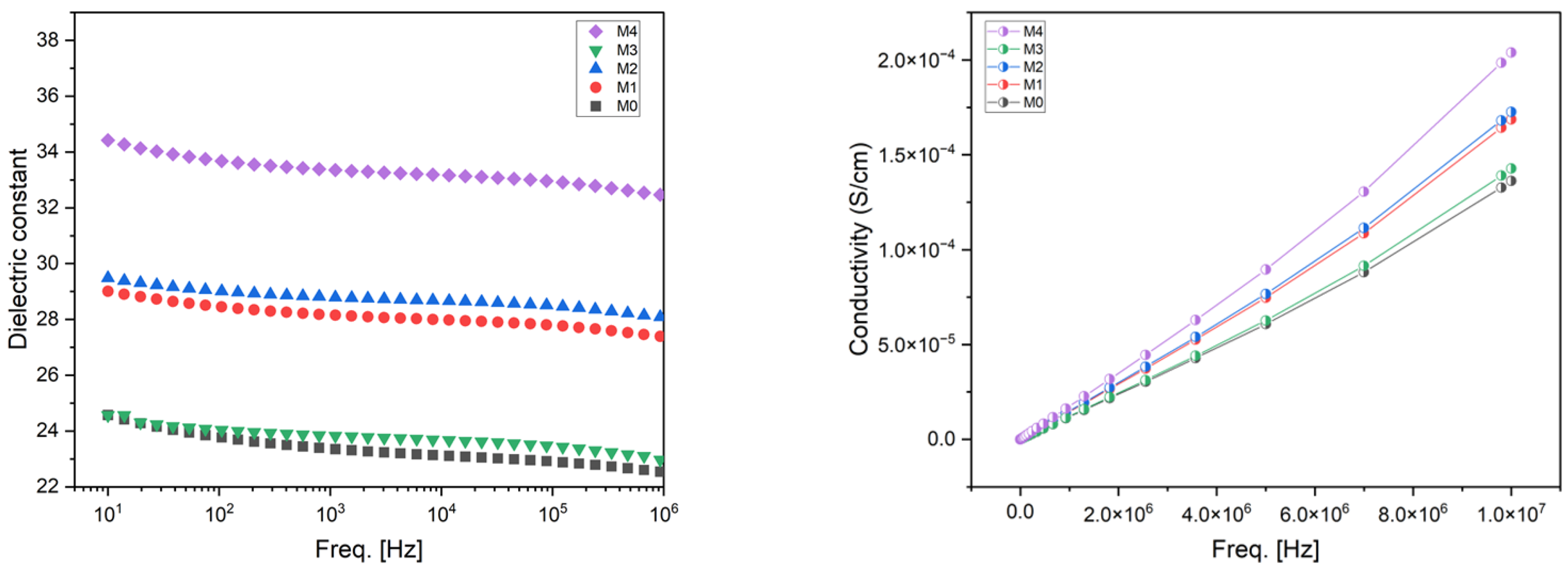

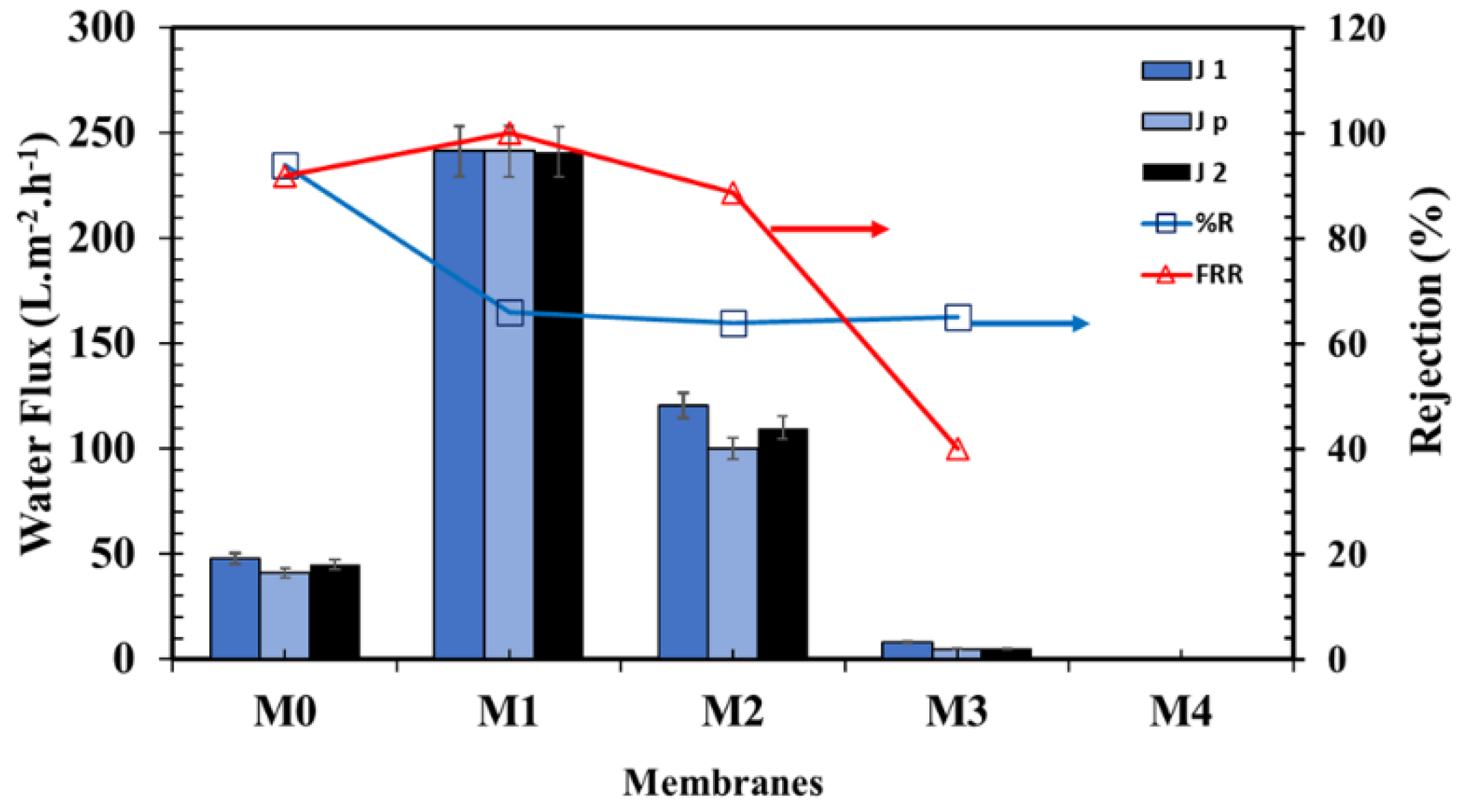

| Membrane | b-CD (wt.%) |

PVP (wt.%) |

Thickness (mm) |

Porosity (%) |

Contact angle (°) | Average pore diameter (nm) | Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEM* | Elford-Ferry equation | Ra (nm) | Rq (nm) | Rpv (nm) | |||||||

| M0 | 0 | 1.00 | 110 ±1 | 47 | 72.6±1.8 | 710 | 500 | 81-101 | 99-118 | 417-437 | |

| M1 | 0.25 | 0.75 | 110 ±1 | 72 | 54.6±1.8 | 345 | 913 | 29-26 | 31-33 | 115-124 | |

| M2 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 100 ±1 | 38 | 63.7±0.8 | 508 | 835 | 50-59 | 66-68 | 281-334 | |

| M3 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 89 ±1 | 31 | 80.9±1.1 | 525 | 176 | 47-52 | 57-63 | 217-28 | |

| M4 | 1.00 | 0 | 80 ±1 | 16 | 87.1±1.5 | 205 | - | 58 | 71-72 | 304-310 | |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).