1. Introduction

SARS-CoV-2 evolution to more transmissible and immune evasive variants has necessitated updating COVID-19 vaccine antigen compositions to more closely match circulating lineages [

1]. Currently, monovalent Omicron XBB.1.5-adapted COVID-19 vaccines are recommended. However, the proportion of cases attributed to the Omicron JN.1 sublineage, which evolved from BA.2.86, has rapidly increased and, as of April 2024, is predominant globally [

2,

3]. JN.1 shows higher immune evasion and diminished ACE2 binding affinity compared with its predecessors [

3]. SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing titers have generally corresponded with vaccine effectiveness [

4]; therefore, it is important to evaluate neutralizing activity against currently circulating lineages following vaccination with XBB.1.5-adapted vaccines.

Safety data 1 month after vaccination and preliminary Omicron XBB.1.5, BA.2.86, and EG.5.1 immunogenicity responses from a substudy of a clinical trial investigating the XBB.1.5-adapted BNT162b2 in vaccine-experienced individuals have already been reported [

5]. In this brief report, we present additional immunogenicity data against Omicron XBB.1.5, BA.2.86, and JN.1.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

The methods, eligibility criteria, and ethical conduct of this study have been described previously [

5]. Briefly, participants who were 12 years and older received a single, 30-μg dose of XBB.1.5-adapted BNT162b2 in a phase 2/3 study conducted in the United States (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05997290). This ongoing and open-label study enrolled healthy individuals who had already received 3 or more doses of a US Food and Drug Administration-authorized mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. The most recent dose was required to be a bivalent Omicron BA.4/BA.5-adapted vaccine administered ≥150 days before participants receiving the study vaccine. This report provides exploratory 1-month immunogenicity data from a subset of 40 participants 18 years and older.

2.2. Objectives, Endpoints, and Assessments

The current analysis evaluated immunogenicity in the same variant neutralization subset from the previous analysis [

5]. The randomly selected subset consisted of 40 participants (20 participants who were 18–55 years of age and 20 participants who were >55 years of age) who had evidence of previous SARS-CoV-2 infection. Sera collected at baseline and 1 month after vaccination were tested against Omicron XBB.1.5, BA.2.86, and JN.1 in a qualified fluorescent focus reduction neutralization test (FFRNT) assay. Geometric mean titers (GMTs) measured 1 month after vaccination, geometric mean fold rises (GMFRs) from before to 1 month after vaccination, and percentages of participants with seroresponses (ie, at least a 4-fold rise from baseline or at least 4 times the lower limit of quantitation (LLOQ) for baseline measurements that were less than the LLOQ) 1 month after vaccination are reported. At baseline and 1 month after vaccination, sera from a bivalent BA.4/BA.5-adapted BNT162b2 historical comparator group (N = 40; ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05472038) were tested concurrently. The bivalent BA.4/BA.5-adapted BNT162b2 and monovalent XBB.1.5 vaccine participants were matched by SARS-CoV-2 infection status, age, and sex. For the bivalent BA.4/BA.5-adapted cohort, the participant was to have received 3 or 4 previous 30-μg doses of the original BNT162b2 vaccine, with the last dose having been administered between 150 and 365 days before study vaccination. Baseline and 1-month samples from both studies were tested at the same time.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Data are presented descriptively. The GMTs and GMFRs were calculated through exponentiation of the mean and the mean of the difference between the 2 time points (baseline and 1 month after vaccination), respectively, of the logarithmically transformed assay results. The corresponding 2-sided 95% CIs were determined using the Student t distribution. Seroresponse data are presented as percentages and associated Clopper-Pearson 95% CIs. The evaluable immunogenicity population was comprised of individuals who received the study vaccine, had at least 1 valid and determinate immunogenicity result 1 month after vaccination visit (28 to 42 days following vaccination), and with no other major protocol deviations.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

In this analysis, among 40 participants who received XBB.1.5-adapted BNT162b2, 52.5% were female, 85.0% were White, 10.0% were Black, and 32.5% were Hispanic or Latino (

Table 1). Median age at vaccination was 35.5 years in the 18–55-year-old group, and 69.5 years in the >55-year-old group. The median time from the last mRNA COVID-19 vaccination to study vaccination was 9.5 months (range, 2‒12 months). Characteristics were generally similar for the 40 participants in the matched bivalent BA.4/BA.5-adapted cohort, apart from a lower percentage of participants with Hispanic or Latino ethnicity compared with the current study (17.5% vs 32.5%) and a slightly longer mean interval from the previous COVID-19 vaccine dose compared with the current study (11.2 months vs 9.1 months).

3.1. Immunogenicity

The evaluable immunogenicity population comprised 36 participants in the XBB.1.5-adapted BNT162b2 cohort; 4 participants were excluded from this population because of protocol deviations occurring on or before the 1 month after vaccination visit (1 participant from the 18–55-year-old group; 3 participants from the >55-year-old group). In the matched bivalent BA.4/BA.5-adapted cohort there were 39 participants in the evaluable immunogenicity population; 1 participant was excluded from this population because the participant did not have at least 1 valid and determinate neutralization immunogenicity result obtained from 28 to 42 days of vaccination.

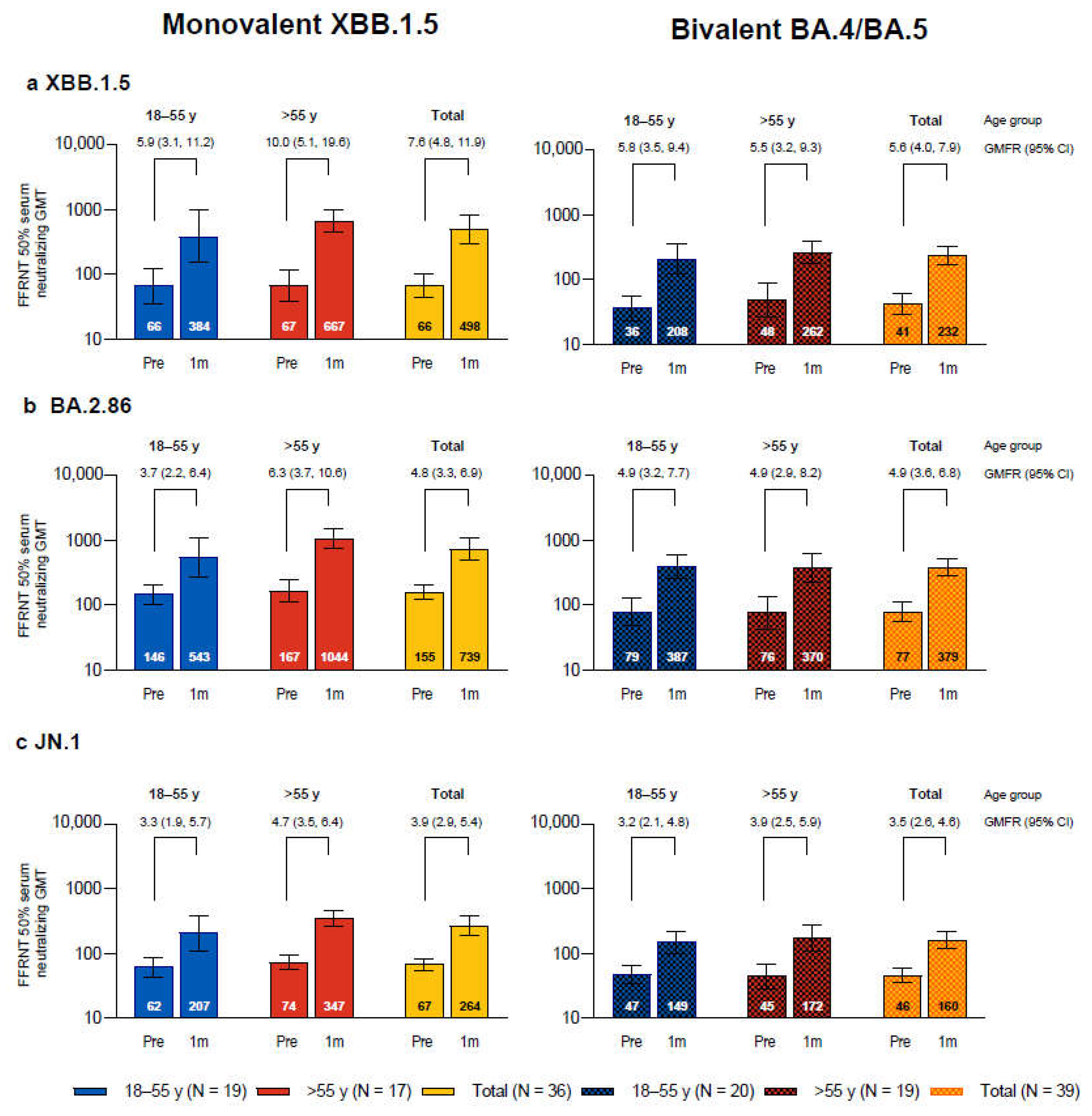

One month after vaccination with monovalent Omicron XBB.1.5-adapted BNT162b2, the SARS-CoV-2 FFRNT 50% neutralizing titers against Omicron XBB.1.5, BA.2.86, and JN.1 increased compared to baseline levels and were each higher than the bivalent Omicron BA.4/BA.5-adapted BNT162b2 matched comparator group (

Figure 1). In participants who received XBB.1.5-adapted BNT162b2, GMTs at baseline were higher for Omicron BA.2.86 compared to XBB.1.5 and JN.1; baseline GMTs were also slightly higher in participants >55 years of age compared to those 18−55 years of age for all 3 sublineages. GMTs 1 month after vaccination were higher for XBB.1.5 and BA.2.86 compared with JN.1. GMFRs from baseline to 1 month after vaccination were higher for XBB.1.5 (overall GMFR, 7.6 (95% CI, 4.8, 11.9)) than for BA.2.86 (4.8 (3.3, 6.9)) and JN.1 (3.9 (2.9, 5.4)). Overall GMFRs from baseline to 1 month after vaccination were higher among participants who received XBB.1.5-adapted BNT162b2 than those who received bivalent BA.4/BA.5-adapted BNT162b2 for XBB.1.5 (7.6 vs 5.6), slightly higher for JN.1 (3.9 vs 3.5), and similar for BA.2.86 (4.8 vs 4.9). In participants who received XBB.1.5-adapted BNT162b2, postvaccination titers in participants >55 years of age (GMT range, 347‒1044) were generally higher compared to those from participants 18−55 years of age (207‒543).

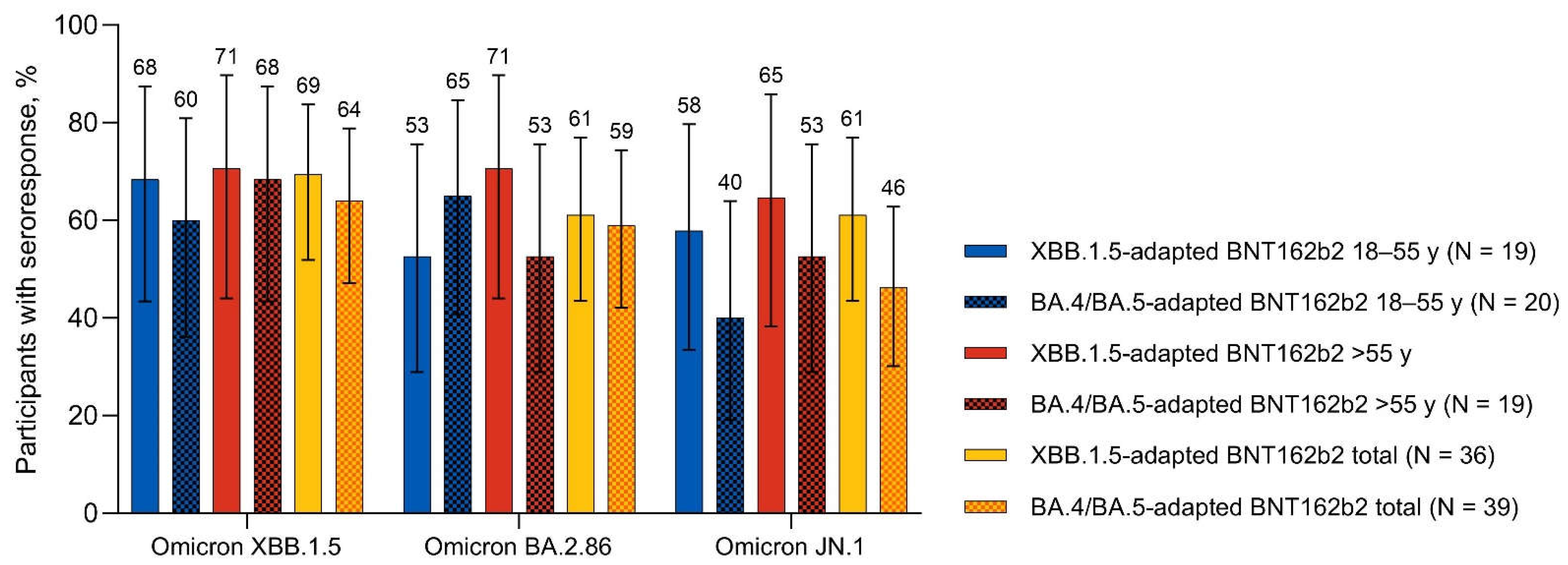

One month after vaccination, the percentages of participants overall with seroresponses in the XBB.1.5-adapted BNT162b2 group were numerically higher than the corresponding percentages of participants in the bivalent BA.4/BA.5-adapted BNT162b2 group for XBB.1.5 (69.4% vs 64.1%), BA.2.86 (61.1% vs 59.0%), and JN.1 (61.1% vs. 46.2%;

Figure 2). The percentages of participants with seroresponses 1 month after XBB.1.5-adapted BNT162b2 were generally similar in 18–55-year-old and >55-year-old participants for Omicron XBB.1.5 (68.4% and 70.6%, respectively) and JN.1 (57.9% and 64.7%). The percentages of participants with seroresponses to Omicron BA.2.86 were slightly lower for 18–55-year-olds (52.6%) than for >55-year-olds (70.6%).

Discussion

In this additional exploratory analysis from a phase 2/3 study, the monovalent Omicron XBB.1.5-adapted BNT162b2 vaccine in baseline-seropositive, vaccine-experienced adults ≥18 years of age induced substantial increases in neutralizing responses against Omicron XBB.1.5, BA.2.86, and JN.1. This subset is considered representative given that seropositivity in the general US population was over 96% by September 2022 [

6]. In the previously published report from this study, the XBB.1.5-adapted BNT162b2 vaccine induced robust neutralizing responses to Omicron XBB.1.5 and EG.5.1 and slightly lower responses to BA.2.86 at 1 month after vaccination in participants who were positive for previous SARS-CoV-2 infection at baseline [

5]. Similarly, in this additional analysis, the immune response to BA.2.86 was preserved in a SARS-CoV-2 baseline-positive subset of participants as previously reported in this subset [

5], while the immune response to JN.1 was reduced. Overall JN.1 GMFRs from before to 1 month after receiving XBB.1.5-adapted BNT162b2 were approximately 1.9 and 1.2 times lower for Omicron XBB.1.5 and BA.2.86, respectively. These results are consistent with the higher potential for immune escape of JN.1 compared to the BA.2.86 and XBB.1.5 sublineages [

3,

7]. One month after vaccination, GMTs, GMFRs, and seroresponses were overall numerically higher for XBB.1.5, BA.2.86, and JN.1 for participants who received XBB.1.5-adapted BNT162b2 than for those who received bivalent BA.4/BA.5-adapted BNT162b2. The higher neutralizing titers obtained for JN.1 with XBB.1.5-adapted BNT162b2 is also consistent with immune escape of distant lineages to vaccine antigens; ie, a closely matched vaccine antigen will likely elicit an improved neutralizing response, and thus better protection than a mismatched antigen [

8]. Although this analysis was not powered to detect a difference between studies, the results are nevertheless encouraging.

Emerging immunogenicity and real-world effectiveness data for XBB.1.5-adapted vaccines are consistent with these observations. Other assessments of neutralizing antibody responses against BA.2.86 and JN.1 in individuals vaccinated with the XBB.1.5-adapted BNT162b2 or the XBB.1.5-adapted mRNA-1273 vaccine were found to be comparable or diminished compared to responses against XBB.1.5 but were nonetheless still potent [

9,

10,

11]. These findings are also supported by emerging assessments of vaccine effectiveness against severe disease including hospitalizations, urgent care or emergency department encounters, and medically attended outpatient COVID-19 following several months of use of XBB.1.5-adapted mRNA vaccines in immunization programs in Europe and North America [

12,

13,

14,

15]. Two of these studies, in the Netherlands and Denmark, were conducted mostly during XBB predominance [

13,

14], while observations from the other 2 studies, from the United States and Canada, also included periods of JN.1 predominance [

12,

15]. Interestingly, a US study found that after approximately 4 months of use of XBB.1.5-adapted vaccines from September 2023 to January 2024, vaccine effectiveness against likely JN.1 lineages was 49% compared with 60% against non-JN.1 lineages with overlapping confidence intervals, thus providing support for the protection provided by XBB.1.5-adapted vaccines against a breadth of contemporary Omicron sublineages [

16]. In contrast, another US study found that XBB.1.5-adapted vaccines were associated with a significantly lower risk of COVID-19 before JN.1 became dominant and a lower but nonsignificant risk after JN.1 predominance with estimated vaccine effectiveness (95% CI) of 42% (32%, 51%) and 19% (–1%, 35%), for the 2 periods, respectively [

17].

Limitations of the current analysis include the short follow-up through 1 month after vaccination. The exploratory immunogenicity analyses were also conducted in a small subset of adults ≥18 years of age who were predominantly White and only from the United States.

In conclusion, these additional immunogenicity data continue to support administration of the currently recommended XBB.1.5-adapted BNT162b2 vaccine while also highlighting the likely need to periodically update COVID-19 vaccines to match with circulating SARS-CoV-2 strains.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.G., X.X., V.B., F.M., K.A.S., A.S.A., K.M., A.G. and N.K.; methodology, J.G., X.X., V.B., M.C., K.M. K.A.S. and N.K.; data acquisition, M.C.; data interpretation, J.G, X.X., V.B., F.M., A.S.A., Ö.T., U.Ş., K.M., K.A.S., A.G. and N.K.; formal analysis, X.X., V.B., and M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.G.; writing—review and editing, all authors; project administration, J.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was sponsored by BioNTech and funded by Pfizer and BioNTech.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the WCG IRB (Puyallup, WA 98374, USA) on 28 July 2023 (Protocol C4591054). ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05997290.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Upon request, and subject to review, Pfizer will provide the data that support the findings of this study. Subject to certain criteria, conditions, and exceptions, Pfizer may also provide access to the related individual de-identified participant data. See

https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical-trials/trial-data-and-results for more information.

Acknowledgments

Editorial/medical writing support was provided by Sheena Hunt PhD, Tricia Newell PhD, and Erin O’Keefe, PhD, of ICON (Blue Bell, PA, USA) and was funded by Pfizer Inc. We thank the participants who volunteered for this study and the study site personnel for their contributions to this study. We thank Kena A. Swanson, Oyeniyi Diya, Francine S. Lowry, Claire Lu, Todd Belanger, David Cooper, Kenneth Koury, Cynthia Ingerick-Holt, Helen Smith, Rucha Dadhe, Pascale Nantermet, Georgina Keep, Ninika Kamra, Prajakta Chivate, Marie Hodrinsky, Pankaj Bhoir, Prathamesh Rode, Kat Vollmer, Julia Usenko, Karen Rosenzweig, Kim Cotton-West, Caroline Westgarth, Izabela Bialach-Lastowiecka, Sara Wren, Richa Kala, Naren Surampali, Jeff Lu, Carolyn Ryan, and John McLaughlin from Pfizer; Shon Remich, Nadine Salisch, Nicola Charpentier, and Ruben Rizzi from BioNTech; Jing Zou, Xuping Xie, and Yanping Hu from the University of Texas Medical Branch, and the Pfizer and BioNTech colleagues not named here who contributed to the success of this trial.

Conflicts of Interest

Özlem Türeci, Uǧur Şahin, and Federico Mensa are BioNTech employees and may hold stock or stock options. Özlem Türeci, Uǧur Şahin, and Kayvon Modjarrad report holding an interest in a patent relevant to this manuscript. All other authors are Pfizer employees and may hold stock or stock options.

References

- World Health Organization. Statement on the Antigen Composition of COVID-19 Vaccines. Last updated December 13. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/13-12-2023-statement-on-the-antigen-composition-of-covid-19-vaccines (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- GISAID. Tracking of hCoV-19 Variants. Available online: https://gisaid.org/hcov19-variants/ (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- Yang, S.; Yu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Jian, F.; Song, W.; Yisimayi, A.; Wang, P.; Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Yu, L.; et al. Fast evolution of SARS-CoV-2 BA.2.86 to JN.1 under heavy immune pressure. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, e70–e72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, B.J.; Kilpatrick, A.M. Predicting Vaccine Effectiveness for Hospitalization and Symptomatic Disease for Novel SARS-CoV-2 Variants Using Neutralizing Antibody Titers. Viruses 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gayed, J.; Diya, O.; Lowry, F.S.; Xu, X.; Bangad, V.; Mensa, F.; Zou, J.; Xie, X.; Hu, Y.; Lu, C.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of the monovalent Omicron XBB.1.5-adapted BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccine in individuals ≥12 years old: a phase 2/3 trial. Vaccines (Basel) 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, J.M.; Manrique, I.M.; Stone, M.S.; Grebe, E.; Saa, P.; Germanio, C.D.; Spencer, B.R.; Notari, E.; Bravo, M.; Lanteri, M.C.; et al. Estimates of SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence and incidence of primary SARS-CoV-2 infections among blood donors, by COVID-19 vaccination status - United States, April 2021-September 2022. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2023, 72, 601–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaku, Y.; Okumura, K.; Padilla-Blanco, M.; Kosugi, Y.; Uriu, K.; Hinay, A.A., Jr.; Chen, L.; Plianchaisuk, A.; Kobiyama, K.; Ishii, K.J.; et al. Virological characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 JN.1 variant. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, e82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoury, D.S.; Docken, S.S.; Subbarao, K.; Kent, S.J.; Davenport, M.P.; Cromer, D. Predicting the efficacy of variant-modified COVID-19 vaccine boosters. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 574–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalkias, S.; McGhee, N.; Whatley, J.L.; Essink, B.; Brosz, A.; Tomassini, J.E.; Girard, B.; Edwards, D.K.; Wu, K.; Nasir, A.; et al. Interim report of the reactogenicity and immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 XBB-containing vaccines. J. Infect. Dis. 2024. [Epub ahead of print]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stankov, M.V.; Hoffmann, M.; Gutierrez Jauregui, R.; Cossmann, A.; Morillas Ramos, G.; Graalmann, T.; Winter, E.J.; Friedrichsen, M.; Ravens, I.; Ilievska, T.; et al. Humoral and cellular immune responses following BNT162b2 XBB.1.5 vaccination. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, e1–e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marking, U.; Bladh, O.; Aguilera, K.; Yang, Y.; Greilert Norin, N.; Blom, K.; Hober, S.; Klingstrom, J.; Havervall, S.; Aberg, M.; et al. Humoral immune responses to the monovalent XBB.1.5-adapted BNT162b2 mRNA booster in Sweden. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, e80–e81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skowronski, D.M.; Zhan, Y.; Kaweski, S.E.; Sabaiduc, S.; Khalid, A.; Olsha, R.; Carazo, S.; Dickinson, J.A.; Mather, R.G.; Charest, H.; et al. 2023/24 mid-season influenza and Omicron XBB.1.5 vaccine effectiveness estimates from the Canadian Sentinel Practitioner Surveillance Network (SPSN). Euro Surveill. 2024, 29, 2400076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Werkhoven, C.H.; Valk, A.W.; Smagge, B.; de Melker, H.E.; Knol, M.J.; Hahne, S.J.; van den Hof, S.; de Gier, B. Early COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness of XBB.1.5 vaccine against hospitalisation and admission to intensive care, the Netherlands, 9 October to 5 December 2023. Euro Surveill. 2024, 29, 2300703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, C.H.; Moustsen-Helms, I.R.; Rasmussen, M.; Soborg, B.; Ullum, H.; Valentiner-Branth, P. Short-term effectiveness of the XBB.1.5 updated COVID-19 vaccine against hospitalisation in Denmark: a national cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, e73–e74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeCuir, J.; Payne, A.B.; Self, W.H.; Rowley, E.A.K.; Dascomb, K.; DeSilva, M.B.; Irving, S.A.; Grannis, S.J.; Ong, T.C.; Klein, N.P.; et al. Interim effectiveness of updated 2023-2024 (monovalent XBB.1.5) COVID-19 vaccines against COVID-19-associated emergency department and urgent care encounters and hospitalization among immunocompetent adults aged ≥18 years - VISION and IVY Networks, September 2023-January 2024. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2024, 73, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Link-Gelles, R.; Ciesla, A.A.; Mak, J.; Miller, J.D.; Silk, B.J.; Lambrou, A.S.; Paden, C.R.; Shirk, P.; Britton, A.; Smith, Z.R.; Fleming-Dutra, K.E. Early estimates of updated 2023-2024 (monovalent XBB.1.5) COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness against symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection attributable to co-circulating Omicron variants among immunocompetent adults - increasing community access to testing program, United States, September 2023-January 2024. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2024, 73, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, N.K.; Burke, P.C.; Nowacki, A.S.; Gordon, S.M. Effectiveness of the 2023-2024 Formulation of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 mRNA Vaccine. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2024.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).