1. Introduction

The evolution trajectory of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has been characterized by uncertainty. Since 2020, there has been an acceleration in the diversity and changing prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 variants, primarily attributable to mutations in the spike protein of the virus. Some of these mutations have led to significant changes in the disease profile and the outcomes of COVID-19 [

1,

2,

3].

Recently, omicron EG.5 lineages of SARS-CoV-2 have shown increased prevalence, growth advantage, and immune escape properties [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. EG.5 evolved from the omicron XBB.1 subvariant and carries an additional F456L amino acid mutation in the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the spike protein [

11,

12]. Globally, the prevalence of COVID-19 linked to EG.5 reached 7.6% by June 25, 2023, and escalated swiftly to 17.4% by August 9, 2023 [

6]. In China, EG.5 and its subvariants accounted for 24.7% of COVID-19 cases in June, rising to 45% a month later, as reported by the World Health Organization (WHO) [

6]. In the United Kingdom, the UK Health Security Agency estimated that EG.5 and its subvariants constituted 14.6% of infections as August began [

6].

From August, 2023, EG.5 was associated with an alarming increase in hospitalizations and mortality due to COVID-19 in the United States. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States, as of August 19, 2023, EG.5 was responsible for the most common cases of COVID-19, accounting for 20.6% of total cases [

5,

6]. Concerns have also arisen about the efficacy of existing vaccines against EG.5, primarily due to a spike protein mutation, F456L [

13,

14]. Laboratory experiments have shown that this mutation can lead to enhanced immune evasion against bivalent mRNA vaccine-induced neutralizing antibodies [

10,

15]. Following a risk assessment by the WHO, EG.5 and its sublineages, which include EG.5.1, EG.5.1.1, and EG.5.2, were designated as Variants of Interest (VOIs) on August 8, 2023. Furthermore, the WHO and the Technical Advisory Group on SARS-CoV-2 Evolution (TAGVE) recommend that Member States continue to share information on the growth advantage of EG.5. They also suggest providing sequence information on a weekly or monthly basis, conducting neutralization assays, and regularly assessing the impact of variants such as EG.5 on the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines [

12].

SCTV01E is a tetravalent COVID-19 protein vaccine, composed of the trimeric spike extracellular domain (S-ECD) from four SARS-CoV-2 variants, specifically Alpha, Beta, Delta, and Omicron BA.1. Notably, in an immunogenicity trial (NCT 05323461), SCTV01E was shown to induce higher levels of nAb against Omicron BA.1 and BA.5 variants compared to the inactivated vaccine and BNT162b2 by day 28 [

16,

17]. Subsequently, a phase 3 trial, which enrolled 9196 participants from December 26, 2022, to January 15, 2023, demonstrated that SCTV01E displayed efficacies of 79.7% in preventing symptomatic infections and 82.4% in preventing all infections caused by SARS-CoV-2 14 post-vaccination (Data submitted).

On March 22, 2023, SCTV01E received Emergency Use Authorization from the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China, allowing its use as a booster dose for COVID-19 vaccination. SCTV01E-2, an updated version, is produced using the same manufacturing process as SCTV01E but incorporates a revised antigen formula that includes the S-ECD of the Beta, Omicron BA.1, BQ.1.1, and XBB.1 variants.

Here, we present the findings from a randomized phase 2 trial assessing the immunogenicity of SCTV01E and SCTV01E-2. The study aimed to evaluate nAb responses against EG.5 and XBB.1 in individuals who had previously completed the primary/booster series of COVID-19 vaccinations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

This ongoing randomized study is divided into two parts: Part A, which involves participants aged 18 years and older, and Part B, which includes participants aged 3-17 years. This report focuses on the results from Part A, which evaluates the safety and immunogenicity of SCTV01E-2 in adults and compares its immunogenicity to its parent vaccine, SCTV01E. Participants were recruited from the Anhui Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention, China. Eligible participants were adults aged ≥18 years who had previously received the COVID-19 vaccine, with a ≥6-month vaccination interval between the last dose COVID-19 vaccine and the signature of the informed consent form (ICF). Participants were excluded if they had a fever (temperature ≥37.3℃) within 72 hours before the study vaccination, a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection within 6 months, or a positive result for nasal/nasopharyngeal/throat swab nucleic acid test or rapid antigen test during screening. Full details related to the inclusion and exclusion criteria are provided in the trial protocol. Part B includes the participants of age from 3-17 years.

2.2. Randomization and Masking

Randomization and drug codes were generated and stored by a third party. The randomization codes were then delivered to the blind statistician by an independent third-party statistician upon the study’s completion.

The randomization plan was generated using SAS software (Version 9.4). An Interactive Network Response System (IWRS) was used to randomize the eligible participants prior to the study. Participants were stratified based on age (18-59 years and ≥60 years), their history of SARS-CoV-2 infection, and the time elapsed since their last vaccination/SARS-CoV-2 infection and the study vaccination (6-11 months and ≥12 months).

2.3. Procedures

Eligible adults were randomly allocated in a 1:1 ratio to receive either one dose of SCTV01E-2 or SCTV01E. Initially, a group of 14 individuals aged 18-59 years served as sentinels and underwent observation. After the Independent Data Monitoring Committee (IDMC) evaluated their 7-day safety profiles, additional participants were enrolled. The study aimed to maintain the proportion of participants aged 60 years and above at less than 40%.

Both SCTV01E-2 and SCTV01E were administered via intramuscular injections into the deltoid muscle on the outer upper arm. Following vaccination, all participants were monitored on-site for a minimum of 30 minutes. Solicited adverse events (AEs) within 7 days, unsolicited AEs within 28 days following the study vaccination, serious adverse events (SAEs), and adverse events of special interest (AESIs) within 365 days were documented. Participants were followed up every month 28-day post-vaccination.

Participants underwent testing on Days 0 (pre-vaccination), 14, and 180, which included assessments for anti-SARS-CoV-2 spike S1+S2 ECD IgG (only on Day 0), anti-spike receptor binding domain (RBD) IgM, and nAb tests. The geometric mean titer (GMT) for anti-spike RBD IgM were determined using a qualitative/semi-quantity enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit from Vazyme (Cat # DD3111), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The GMT for live virus nAb activity were measured through plaque reduction neutralization tests (PRNT), using the test kit as described in a previous study [

18,

19].

Following vaccination, participants were regularly contacted via phone calls, text messages, emails, visits at site, or other means of communication to inquire about COVID-19-related symptoms. The frequency of follow-up was adjusted as per the study’s progression. Participants were also encouraged to spontaneously report any COVID-19 symptoms during the study. Rapid antigen or nucleic acid tests (nasal/nasopharyngeal/throat swabs) were conducted for individuals displaying symptoms suggestive of COVID-19.

2.4. Outcomes

In Part A, the primary endpoint was the 14-day post-vaccination GMT and seroresponse rate (SRR) of nAb against the primary circulating variants during the study, which was determined as the Omicron EG.5 sublineage. Secondary endpoints included the 14-day post-vaccination GMT and SRR of nAb against the SARS-CoV-2 variants that were adjusted as per the epidemic variants, and the 180-day post-vaccination GMT and SRR of nAb against current and other SARS-CoV-2 variants. Exploratory endpoints covered the first occurrence of symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection, of any severity, starting from 7 days post-vaccination.

Safety endpoints comprised the incidence and severity of solicited adverse events (AEs) of SCTV01E-2 from Day 0 to Day 7, unsolicited AEs from Day 0 to Day 28, and serious AEs and adverse events of special interest (AESIs) from Day 0 to Day 365. AE severity was graded according to guidelines for adverse event grading in preventive vaccine clinical trials [

20].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analyses were done with SAS software (version 9.4). The statistical analysis was carried out with descriptive and pre-specified statistical test methods. The sample size for the immunogenicity assessment was determined based on a superiority design intended to demonstrate that SCTV01E-2 was superior to SCTV01E in terms of the Geometric Mean Ratio (GMR) and seroresponse rate (SRR) of nAb against the current Omicron EG.5.

The statistical hypotheses for the primary endpoint assumed that the low boundary of GMR related to nAb against the current EG.5 variant between the SCTV01E-2 group and the SCTV01E group is greater than 1. Additionally, it assumed that the low boundary of difference in the SRR between the SCTV01E-2 and SCTV01E groups is greater than 0.

Safety assessments were done for those who received the study vaccine (Safety Set). Participants were grouped based on the vaccines they received. Immunogenicity assessments were carried out on the Immunogenicity Per-Protocol Set (I-PPS), which consisted of individuals who had a valid immunogenicity test result before and after receiving the study vaccines and had a negative result for the anti-spike receptor binding domain (RBD) IgM test at the beginning. Data on immunogenicity were not considered if participants had evidence of a SARS-CoV-2 infection before the visit.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Baseline Characteristics

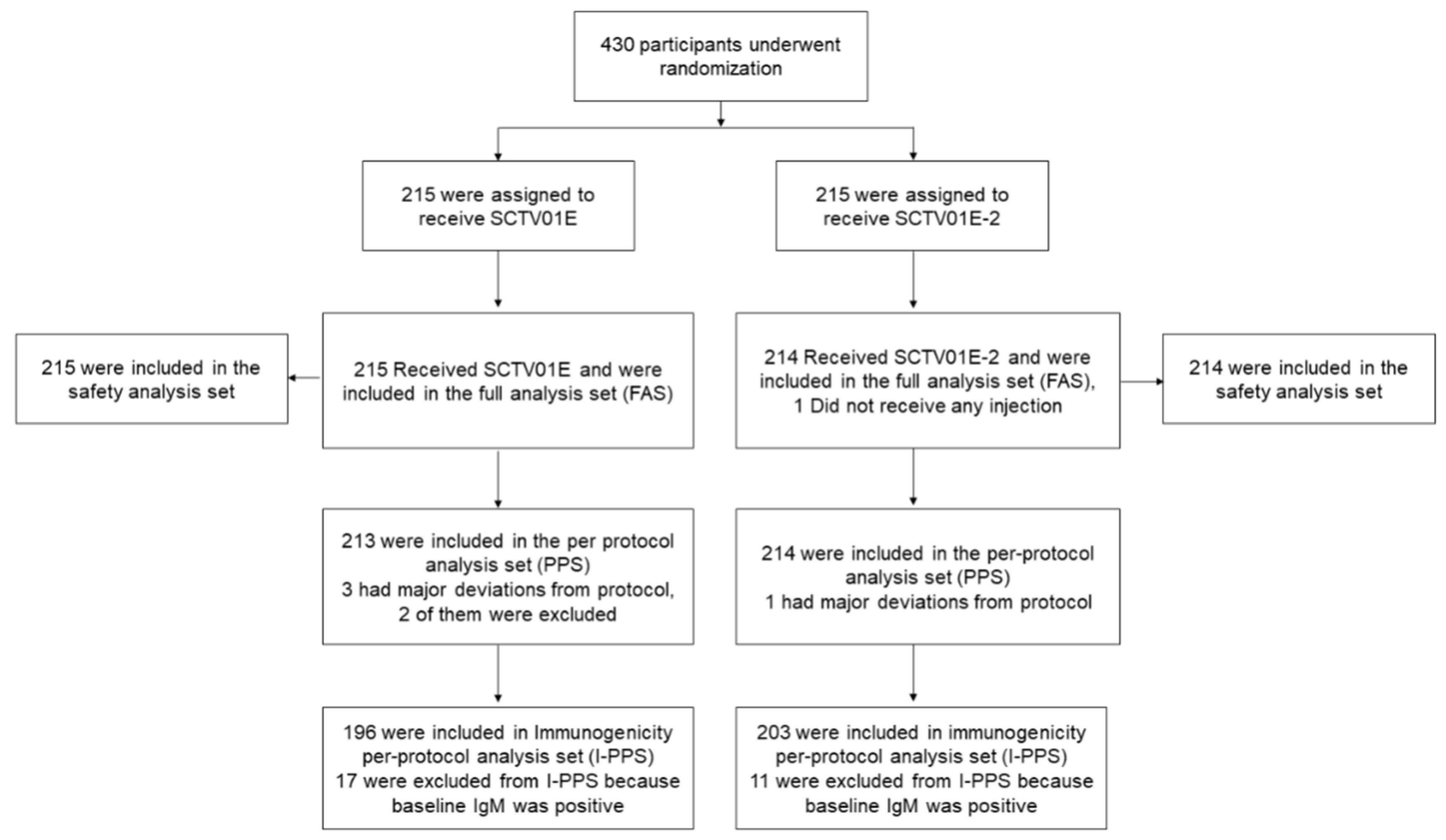

As of the September 12, 2023 cutoff date, 430 participants were enrolled in Part A. Out of these, 429 participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive either SCTV01E-2 (N=214) or SCTV01E (N=215) (

Figure 1). 258 (60.1%) participants aged 18-59 years, and 199 (46.4%) participants were male. Demographic characteristics were well-balanced between the two groups (

Table S1). The mean (SD) BMI was 26.5 (3.5) in the SCTV01E-2 group and 26.2 (3.5) in the SCTV01E group. A small percentage of participants had positive anti-spike RBD IgM (5.1% in the SCTV01E-2 group, 7.9% in the SCTV01E group), while a similar proportion had a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection (26.2% in SCTV01E-2, 26.5% in SCTV01E). Pre-existing comorbidities were reported by 45.8% in the SCTV01E-2 group and 39.1% in the SCTV01E group.

Figure 1.

Randomization and Analysis Population. 430 participants were recruited and randomized in part A of this study, among them, the safety analysis population included 429 participants who had received the study vaccine. The immunogenicity per-protocol analysis population included 399 participants, who had a valid immunogenicity test result prior to the administration of study vaccines and after the administration of study vaccines and had a negative result of anti-spike receptor binding domain (RBD) IgM test at baseline but without major protocol deviations.

Figure 1.

Randomization and Analysis Population. 430 participants were recruited and randomized in part A of this study, among them, the safety analysis population included 429 participants who had received the study vaccine. The immunogenicity per-protocol analysis population included 399 participants, who had a valid immunogenicity test result prior to the administration of study vaccines and after the administration of study vaccines and had a negative result of anti-spike receptor binding domain (RBD) IgM test at baseline but without major protocol deviations.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Participants in the Full Analysis Set.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Participants in the Full Analysis Set.

| |

SCTV01E

(N = 215)

n (%) |

SCTV01E-2

(N = 214)

n (%) |

Total

(N = 429)

n (%) |

| Age (Years) |

|

|

|

| N |

215 |

214 |

429 |

| Mean (SD) |

56.1 (12.1) |

55.1 (11.5) |

55.6 (11.8) |

| Median (Min, Max) |

58.0 (20, 81) |

58.0 (19, 83) |

58.0 (19, 83) |

| Age subgroups-randomization, n (%) |

18-59 years

≥60years |

130 (60.5)

85 (39.5) |

128 (59.8)

86 (40.2) |

258 (60.1)

171 (39.9) |

| Sex, n (%) |

|

|

|

| Male |

101 (47.0) |

98 (45.8) |

199 (46.4) |

| Female |

114 (53.0) |

116 (54.2) |

230 (53.6) |

| Nation, n (%) |

|

|

|

| Han |

214 (99.5) |

214 (100.0) |

428 (99.8) |

| Others |

1 (0.5) |

0 |

1 (0.2) |

| BMI (kg/m2)‡ |

|

|

|

| N |

215 |

214 |

429 |

| Mean (SD) |

26.2 (3.5) |

26.5 (3.5) |

26.4 (3.5) |

| Median (Min, Max) |

26.0 (18.9, 38.6) |

26.50 (16.4, 39.8) |

26.20 (16.4, 39.8) |

| History of SARS-CoV-2 infection, n (%) |

| Yes |

57 (26.5) |

56 (26.2) |

113 (26.3) |

| No |

158 (73.5) |

158 (73.8) |

316 (73.7) |

| Previous vaccination/infection interval, n (%) |

| 6-11 months |

67 (31.2) |

67 (31.3) |

134 (31.2) |

| ≥12 months |

148 (68.8) |

147 (68.7) |

295 (68.8) |

| IgM at baseline |

|

|

|

| Positive |

17 (7.9) |

11 (5.1) |

28 (6.5) |

| Negative |

198 (92.1) |

203 (94.9) |

401 (93.5) |

| Booster dose of COVID-19 vaccine, n (%) |

| Yes |

157 (73.0) |

155 (72.4) |

312 (72.7) |

| No |

58 (27.0) |

59 (27.6) |

117 (27.3) |

| Type of last received COVID-19 vaccine-randomization, n (%) |

| Inactive vaccine |

98 (45.6) |

103 (48.1) |

201 (46.9) |

| Adenovirus vector vaccine |

42 (19.5) |

35 (16.4) |

77 (17.9) |

| Recombinant protein vaccine |

75 (34.9) |

76 (35.5) |

151 (35.2) |

| Other vaccines |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Pre-existing comorbidities, n (%) |

|

|

|

| Yes |

84 (39.1) |

98 (45.8) |

182 (42.4) |

| No |

131 (60.9) |

116 (54.2) |

247 (57.6) |

For the immunogenicity per-protocol set (I-PPS) analysis, 399 participants were included (203 in SCTV01E-2 and 196 in SCTV01E), and their demographic characteristics were also well-balanced (

Figures S1–S4).

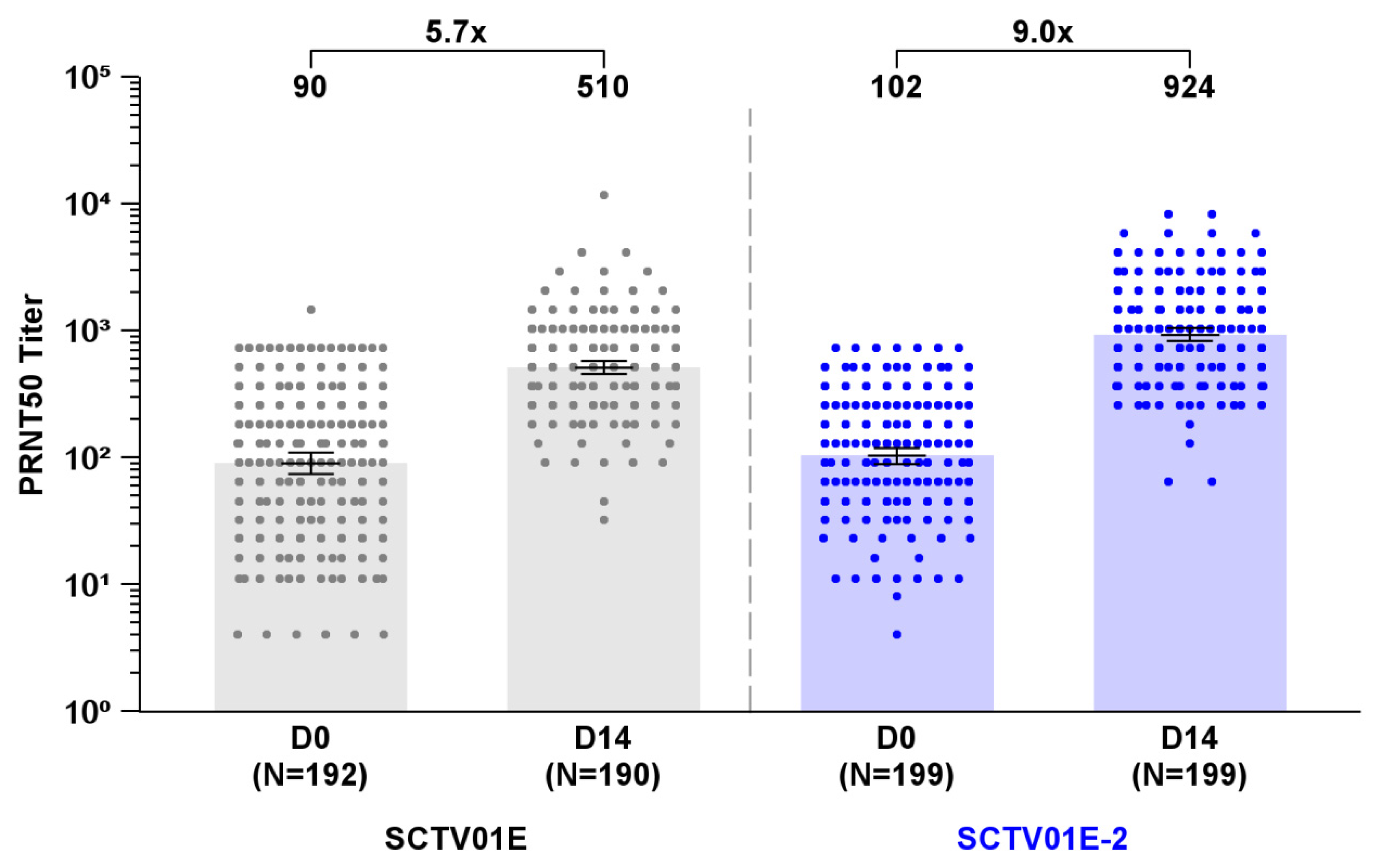

3.2. GMT and SRR of Live Virus nAb against Omicron EG.5

At Day 14 post-vaccination, the GMT of live virus neutralizing antibodies (nAb) against Omicron EG.5 subvariant was 924 (95% CI: 823, 1037) in the SCTV01E-2 group and 510 (95% CI: 454, 573) in the SCTV01E group, with a 9.0 and 5.7-fold change over baseline (

Figure 2). The Least Square Geometric Mean Ratio (LS GMR) of SCTV01E-2/SCTV01E was 1.8 (95% CI: 1.5, 2.1) (

P<0.001), meeting the predetermined criteria for superiority. The SRR for nAb against Omicron EG.5 was 78.9% (157/199) in the SCTV01E-2 group and 61.6% (117/190) in the SCTV01E group, resulting in a differential SRR of 17.3% (95% CI: 8.3%, 26.1%), which also met the predefined criteria for superiority.

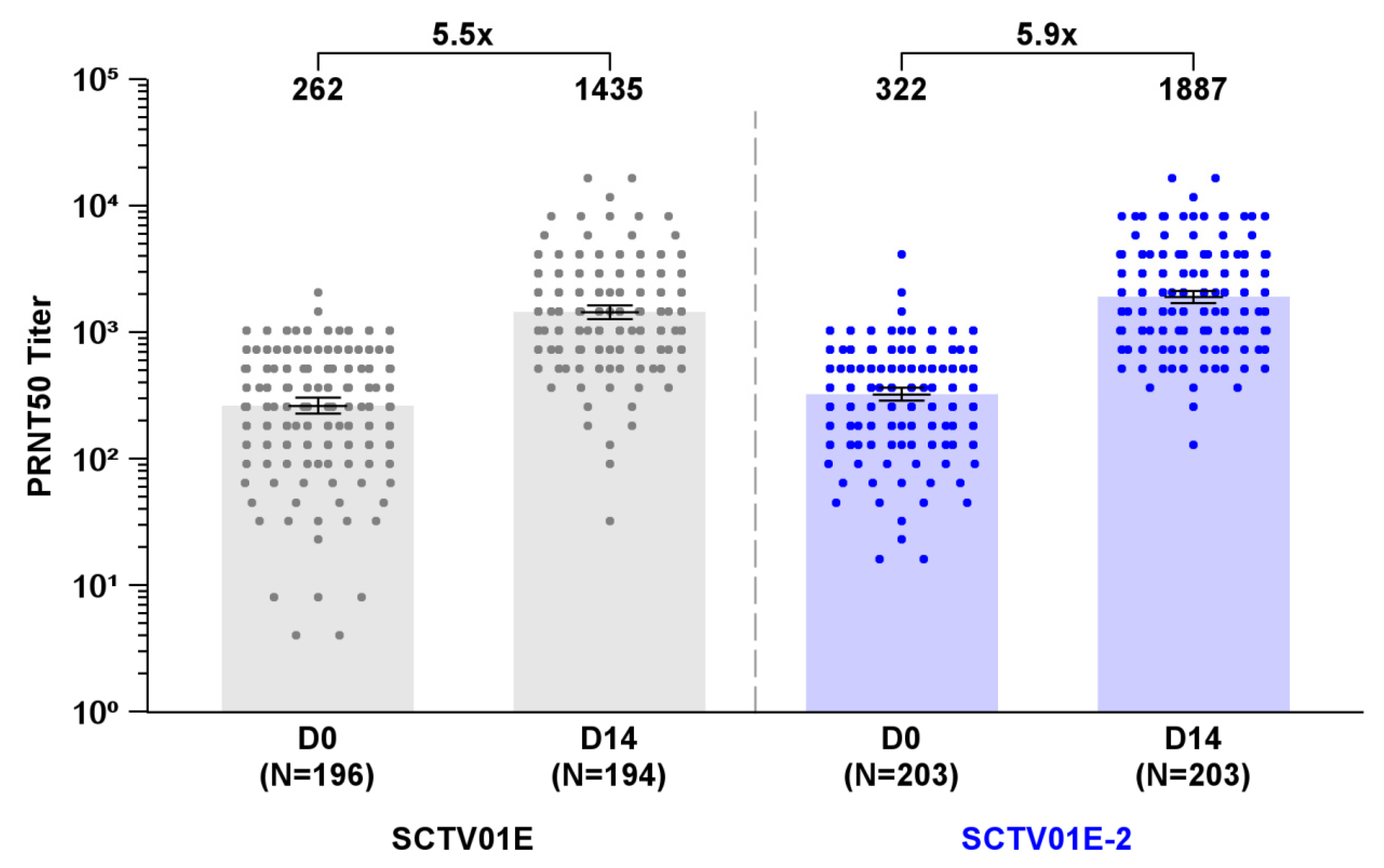

3.3. GMT and SRR of Live Virus nAb against Omicron XBB.1

The GMTs of live virus nAb against Omicron XBB.1 were 1887 (95% CI: 1686, 2112) in the SCTV01E-2 group and 1435 (95% CI: 1267, 1626) in the SCTV01E group, showing a 5.9 and 5.5-fold increase from baseline (

Figure 3). The LS GMR of SCTV01E-2/SCTV01E was 1.3 (95% CI: 1.1, 1.5) (

P = 0.005). The SRR of nAb against Omicron XBB.1 was similar between the two groups, with 68.5% (139/203) in the SCTV01E-2 group and 62.4% (121/194) in the SCTV01E group (

P = 0.206), respectively.

3.4. Subgroup Analyses of nAb Responses to Omicron EG.5 and XBB.1

Subgroup analyses were conducted by stratifying participants based on sex, age, history of SARS-CoV-2 infection, time intervals between the last dose vaccine/previous infection and study vaccine, whether they had received a booster dose of a COVID-19 vaccine or not, the type of the last COVID-19 vaccine dose, and the presence of pre-existing comorbidities. SCTV01E-2 consistently led to significantly higher GMT against Omicron EG.5 than SCTV01E in all subgroups. The only exception was that a similar GMT was observed between the two groups of participants who had previously received an adenovirus vector vaccine (

Supplementary Materials Figure S1). Similarly, significantly higher SRR was observed in most subgroups within the SCTV01E-2 group in comparison to the SCTV01E group, while in participants with a history of prior infection, those who hadn’t completed the booster immunization, or those who had previously received an adenovirus vector vaccine, the SRR appeared comparable between the two groups (

Supplementary Materials Figure S2).

For Omicron EG.5, SCTV01E-2 elicited a higher increase in the GMT (95% CI) among participants aged ≥60 years (1046 [863, 1269]) compared to those aged 18-59 years (850 [736, 981]). The vaccine exhibited similar GMT (95% CI) among participants with pre-existing comorbidities (937 [775, 1134]) and those without pre-existing comorbidities (914 [791, 1057]). Furthermore, the female group demonstrated a more substantial increase in GMT (95% CI) in comparison to the male group (female vs. male: 1061 [915, 1230] vs. 787 [658, 940]) (

Supplementary Materials Figure S1).

Regarding Omicron XBB.1, SCTV01E-2 demonstrated higher GMT levels among older participants (≥60 years) in comparison to younger participants (18-59 years) (2101 [1772, 2490] vs. 1754 [1509, 2039]). Similarly, participants with pre-existing comorbidities exhibited higher GMT levels than those without pre-existing comorbidities (1963 [1669, 2308] vs. 1828 [1561, 2141]). (

Supplementary Materials Figures S3 and S4).

3.5. Vaccine Efficacy

As of the September 12, 2023 cutoff date, no participant had reported symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Since the study is still in progress, the long-term efficacy of the study vaccine will continue to be monitored.

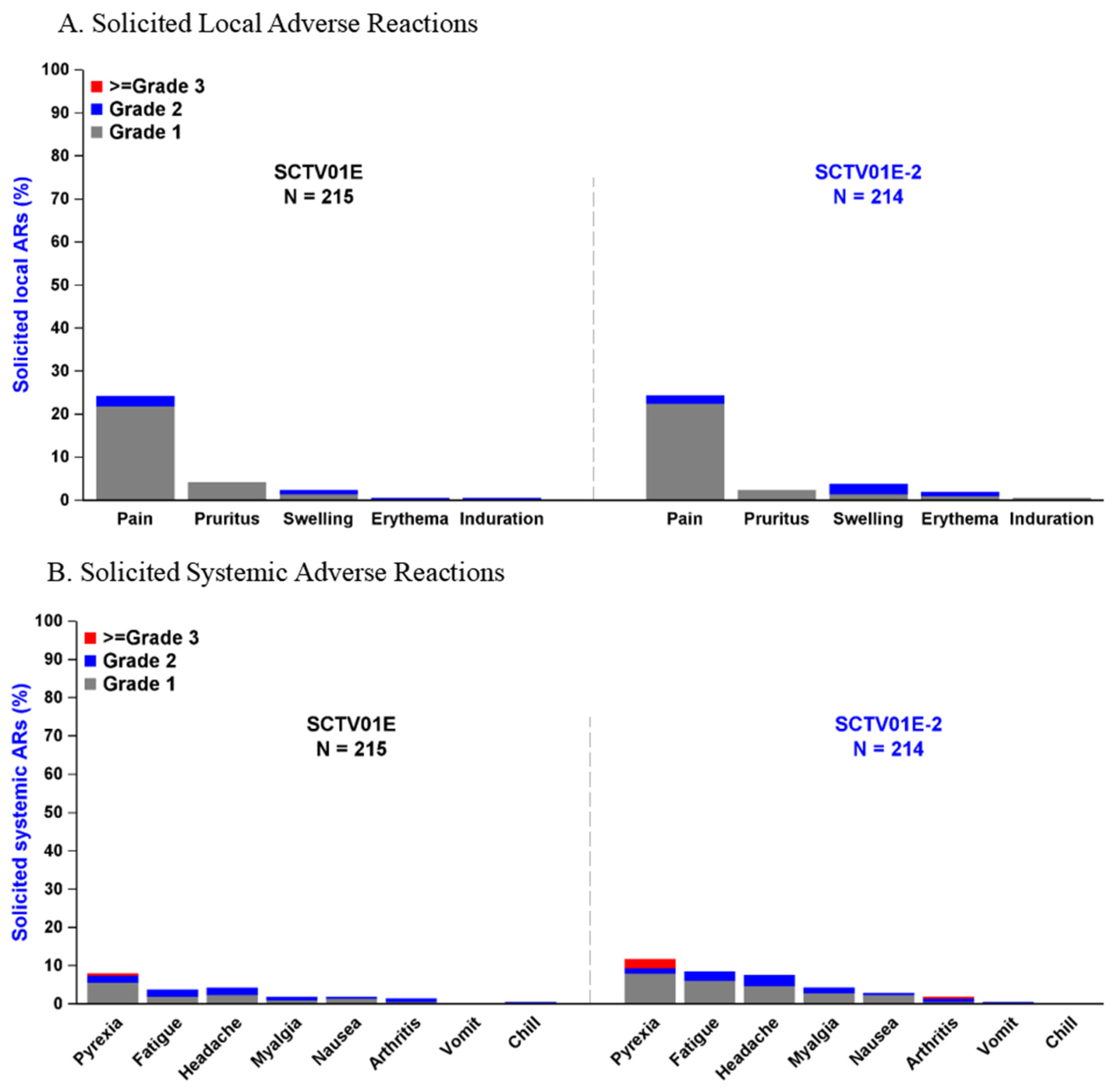

3.6. Adverse Events

A total of 429 participants were included in the safety set, with 214 in the SCTV01E-2 group and 215 in the SCTV01E group. The overall incidence of adverse events (AEs) was similar between the two groups (SCTV01E-2 vs. SCTV01E, 42.5% vs. 39.1%). The overall incidence of AEs was low within 30 minutes after vaccination, 0.9% in the SCTV01E-2 group, and 1.9% in the SCTV01E group. The incidence of treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) was 37.4% in the SCTV01E-2 group and 33.5% in the SCTV01E group. Within 7 days after injection, 27.6% of participants in the SCTV01E-2 group and 27.9% in the SCTV01E group reported solicited local adverse reactions (ARs), while 20.6% in the SCTV01E-2 group and 12.6% in the SCTV01E group reported solicited systemic ARs. Within 28 days post-vaccination, 0.5% of participants in the SCTV01E-2 group and 1.4% in the SCTV01E group reported unsolicited ARs. There were no treatment-related serious adverse events (SAEs), adverse events of special interest (AESIs), or reported deaths.

The most common solicited local ARs with an incidence of 1% or higher included injection site pain (SCTV01E-2 vs. SCTV01E, 24.3% vs. 24.2%), injection site pruritus (SCTV01E-2 vs. SCTV01E, 2.3% vs. 4.2%), injection site swelling (SCTV01E-2 vs. SCTV01E, 3.7% vs. 2.3%), and injection site erythema (SCTV01E-2 vs. SCTV01E, 1.9% vs. 0.5%) (

Figure 4A)

. The most frequent solicited systemic ARs included pyrexia (SCTV01E-2 vs. SCTV01E, 11.7% vs. 7.9%), fatigue (SCTV01E-2 vs. SCTV01E, 8.4% vs. 3.7%), headache (SCTV01E-2 vs. SCTV01E, 7.5% vs. 4.2%), myalgia (SCTV01E-2 vs. SCTV01E, 4.2% vs. 1.9%), nausea (SCTV01E-2 vs. SCTV01E, 2.8% vs. 1.9%), and arthritis (SCTV01E-2 vs. SCTV01E, 1.9% vs. 1.4%) (

Figure 4B). Most solicited ARs were Grade 1 or 2. 6 (2.8%) participants in the SCTV01E-2 group and 1 (0.5%) participant in the SCTV01E group reported Grade 3 or above solicited systemic ARs, including 6 participants reported Grade 3 or above pyrexia (SCTV01E-2 vs. SCTV01E, 5 [2.3%] vs. 1 [0.5%]), 1 (0.5%) participants in the SCTV01E-2 group reported Grade 3 or above arthralgia.

3.6. Subgroup Analyses of Adverse Events

Stratified analysis by age revealed that the occurrence of TRAEs was lower in participants aged ≥60 years compared to those aged 18-59 years. Specifically, in the SCTV01E-2 group, the incidence of TRAEs was 31.4% among participants aged ≥60 years, 41.4% among participants aged 18-59 years; in the SCTV01E group, the incidence was 32.9% among the participants aged ≥60 years, 33.8% among the participants aged 18-59 years. In the SCTV01E-2 group, 2 (2.3%) participants aged ≥60 years reported Grade 3 or above TRAEs (one each reported pyrexia and arthralgia), compared with 4 (3.1%) among the young participants (18-59 years) (pyrexia); in the SCTV01E group, only 1 (0.8%) participant aged 18-59 years reported Grade 3 or above TRAEs (pyrexia). The occurrence of TRAEs in participants with pre-existing comorbidities was similar to that observed in the overall safety analysis population, with 38.8% incidence in the SCTV01E-2 group and 38.1% incidence in the SCTV01E group.

4. Discussion

In this ongoing Phase II trial, SCTV01E-2 exhibited similar safety as its parent vaccine SCTV01E, and elicited a significant neutralizing response against the Omicron sublineages, EG.5 and XBB.1 when administrated as a booster dose. This study included a substantial high-risk population, with 40% of participants aged over 60 years and 42% with chronic comorbidities. The results indicated that SCTV01E-2 elicited comparable levels of nAb responses in these participants when compared to those who were younger or without underlying health conditions. Both SCTV01E-2 and SCTV01E were well-tolerated across all age groups and medical histories. The majority of AEs were mild and temporary, no vaccine related SAEs, AESIs or deaths were reported.

Multivalent vaccine represents a significant strategy for the development of broad-spectrum vaccine, as each variant contributes unique neutralizing epitopes that expand the repertoire of neutralizing antibodies, collectively inducing cross-neutralizing antibody responses. SCTV01E-2 and SCTV01E are two examples of multivalent COVID-19 vaccines. SCTV01E, derived from the bivalent vaccine SCTV01C, while SCTV01E-2, designed as an antigen-adapted vaccine based on SCTV01E, adjusts its antigen composition to align with the emerging strains, which include the Beta, BA.1, BQ.1.1, and XBB.1 variants. This adaptive multivalent vaccine platform has the capacity to promptly adjust the vaccine formulation to address the continuously evolving nature of the virus.

Neutralizing antibody level is a key determinant and highly predictive of immune protection against symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection [

21]. In this study, SCTV01E-2 demonstrates superior neutralization against Omicron EG.5, with significantly higher fold-increases in GMT and seroresponse rates compared to SCTV01E. Considering that SCTV01E has already proven its efficacy in preventing symptomatic COVID-19 in a Phase III study and has received authorization for use in China, it is anticipated that SCTV01E-2 would also demonstrate efficacy against SARS-CoV-2 infection, particularly for the circulating EG.5 and its sublineages.

The current rapid spread of EG.5 suggests a competitive advantage, as indicated by its reproductive (R) number, and implies that EG.5 and its sublineages are likely to continue dominating in the coming months. In this study, SCTV01E-2 induced significant nAb responses against both antigen-matched variant XBB.1 and antigen-mismatched variant EG.5, aligning with similar results from Moderna’s XBB.1.5-containing mRNA COVID-19 vaccine, which also elicited neutralizing responses against XBB-lineage (XBB.1.5, XBB.1.6, XBB.2.3.2) and recent (EG.5.1, FL.1.5.1) variants [

22,

23]. These findings suggest that XBB-containing COVID-19 vaccines could induce nAb responses against XBB.1 subsequent lineages [

22,

23]. SCTV01E-2 may be a viable vaccine option to prevent the possible EG.5 and its sublineages outbreaks.

This report has a few limitations. First, it only presents the nAb response at day 14 post-vaccination and the short-term safety profile. The study will continue to monitor participants for a minimum of 12 months to evaluate the duration of nAb and long-term safety. Second, determining prior COVID-19 cases was relied on participant self-reporting, given the difficulty of distinguishing between infection and vaccination through serological tests, especially in the context of widespread use of inactivated COVID-19 vaccines [

24,

25]. This may lead to an underestimation of the percentage of participants with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Third, one of the study’s goals was to assess vaccine efficacy. However, at the time of the data cutoff, no cases of COVID-19 were identified in either group.

5. Conclusion

In summary, SCTV01E-2 demonstrated a robust nAb response against the latest SARS-CoV-2 variant of interest, EG.5, with no safety concerns. As an antigen-adapted vaccine derived from SCTV01E, SCTV01E-2 is a promising COVID-19 vaccine, providing comprehensive protection against SARS-CoV-2 variants, particularly for older adults and individuals with chronic comorbidities.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org. Table S1: Demographic Characteristics of Participants in the Immunogenicity Per-Protocol Set. Figure S1: Subgroup Analysis of GMT and LS GMR of Live Virus nAb against Omicron EG.5. Figure S2: Subgroup Analysis of SRR of Live Virus nAb against Omicron EG.5. Figure S3: Subgroup Analysis of GMT and LS GMR of Live Virus nAb against Omicron XBB.1. Figure S4: Subgroup Analysis of SRR of Live Virus nAb against Omicron XBB.1.

Author Contributions

J.T., Q.X., C.Z., K.X., T.L., Q.L., X.P. and H.X., contributed to the participant enrollment, progress and quality control, and center resources coordination. J.T., C.Z., and L.Q., as the investigators of this clinical trial, contributed to the participant management. G.W. contributed to sample management. The major study physician, L.Q. and C.Z., contributed to the participant management. J.T., K.X., Z.Z. and J.L. contributed to the process management of the whole study and the coordination of resources in the hospital (vaccine management, vaccination, participants screening management, communication and coordination with the sponsor, CRO, and ethics). Y.T. contributed to drug management and blind quality control. J.H. contributed to laboratory testing and assay development. C.G. and G.Q. contributed to manuscript drafting. C.G. contributed to the medical management, protocol writing. X.T. contributed to project management. L.X. contributed to the study conception, study design, project management, data interpretation. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. The authors assume responsibility for the accuracy and completeness of the data and for the fidelity of the trial to the protocol. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Sinocelltech Ltd. and funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China [2023YFC3042100], Beijing Science and Technology Planning Project [Z231100004823003] and National Key Research and Development Program of China [2022YFC0870600].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The protocol of this study, the written informed consent form, and other information related to participants were approved by the clinical research ethics board of the Anhui Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention (China), (protocol code: SCTV01E-2-CHN-1; date of approval: July, 20, 2023). This trial followed the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice (GCP) requirements, and related regulations issued by authorities.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The authors also declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the main manuscript or the

supplementary material. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed

to L.X. (

LX@sinocelltech.com).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients and their families and caregivers for participating in this trial, along with all investigators and site personnel. This study was sponsored by Sinocelltech Ltd. and funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China, Beijing Science and Technology Planning Project and National Key Research and Development Program of China.

Conflicts of Interest

C.G., G.Q., and X.T. are employees of Sinocelltech Ltd., and L.X. has potential stock option interests in the company. All authors declare no other conflicts of interest.

References

- Markov, P.V.; Ghafari, M.; Beer, M.; Lythgoe, K.; Simmonds, P.; Stilianakis, N.I.; Katzourakis, A. The evolution of SARS-CoV-2. Nat Rev Microbiol 2023, 21, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viana, R.; Moyo, S.; Amoako, D.G.; Tegally, H.; Scheepers, C.; Althaus, C.L.; Anyaneji, U.J.; Bester, P.A.; Boni, M.F.; Chand, M.; et al. Rapid epidemic expansion of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant in southern Africa. Nature 2022, 603, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hachmann, N.P.; Miller, J.; Collier, A.Y.; Ventura, J.D.; Yu, J.; Rowe, M.; Bondzie, E.A.; Powers, O.; Surve, N.; Hall, K.; et al. Neutralization Escape by SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Subvariants BA.2.12.1, BA.4, and BA.5. N Engl J Med 2022, 387, 86–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parums, D.V. Editorial: A Rapid Global Increase in COVID-19 is Due to the Emergence of the EG.5 (Eris) Subvariant of Omicron SARS-CoV-2. Med Sci Monit 2023, 29, e942244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbasi, J. What to Know About EG.5, the Latest SARS-CoV-2 “Variant of Interest”. JAMA 2023, 330, 900–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyer, O. COVID-19: Infections climb globally as EG.5 variant gains ground. BMJ 2023, 382, 1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zappa, M.; Verdecchia, P.; Andolina, A.; Angeli, F. The old and the new: The EG.5 (‘Eris’) sub-variant of Coronavirus. Eur J Intern Med. [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, F.; Darvishi, M.; Bezmin Abadi, A.T. ‘The end’ - or is it? Emergence of SARS-CoV-2 EG.5 and BA.2.86 subvariants. Future Virol 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Kempf, A.; Nehlmeier, I.; Cossmann, A.; Dopfer-Jablonka, A.; Stankov, M.V.; Schulz, S.R.; Jack, H.M.; Behrens, G.M.N.; Pohlmann, S.; et al. Neutralisation sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 lineages EG.5.1 and XBB.2.3. Lancet Infect Dis 2023, 23, e391–e392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faraone, J.N.; Qu, P.; Goodarzi, N.; Zheng, Y.M.; Carlin, C.; Saif, L.J.; Oltz, E.M.; Xu, K.; Jones, D.; Gumina, R.J.; et al. Immune Evasion and Membrane Fusion of SARS-CoV-2 XBB Subvariants EG.5.1 and XBB.2.3. Emerg Microbes Infect 2023, 2270069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarpa, F.; Pascarella, S.; Ciccozzi, A.; Giovanetti, M.; Azzena, I.; Locci, C.; Casu, M.; Fiori, P.L.; Quaranta, M.; Cella, E.; et al. Genetic and structural analyses reveal the low potential of the SARS-CoV-2 EG.5 variant. J Med Virol 2023, 95, e29075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. W.H.O. EG.5 initial risk evaluation. 9 August 2023.

- Wang, Q.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, R.M.; Ho, J.; Mohri, H.; Valdez, R.; Manthei, D.M.; Gordon, A.; Liu, L.; Ho, D.D. Antibody neutralisation of emerging SARS-CoV-2 subvariants: EG.5.1 and XBC.1.6. Lancet Infect Dis 2023, 23, e397–e398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaku, Y.; Kosugi, Y.; Uriu, K.; Ito, J.; Hinay, A.A., Jr.; Kuramochi, J.; Sadamasu, K.; Yoshimura, K.; Asakura, H.; Nagashima, M.; et al. Antiviral efficacy of the SARS-CoV-2 XBB breakthrough infection sera against omicron subvariants including EG.5. Lancet Infect Dis 2023, 23, e395–e396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurhade, C.; Zou, J.; Xia, H.; Liu, M.; Chang, H.C.; Ren, P.; Xie, X.; Shi, P.Y. Low neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.2.75.2, BQ.1.1 and XBB.1 by parental mRNA vaccine or a BA.5 bivalent booster. Nat Med 2023, 29, 344–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannawi, S.; Yan, L.; Saifeldin, L.; Abuquta, A.; Alamadi, A.; Mahmoud, S.A.; Hassan, A.; Zhang, M.; Gao, C.; Chen, Y.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of multivalent SARS-CoV-2 protein vaccines: a randomized phase 3 trial. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 64, 102195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannawi, S.; Saifeldin, L.; Abuquta, A.; Alamadi, A.; Mahmoud, S.A.; Hassan, A.; Xu, S.; Li, J.; Liu, D.; Baidoo, A.A.H.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a tetravalent and bivalent SARS-CoV-2 protein booster vaccine in men. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 4043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, S.; Ganesan, S.; Al Kaabi, N.; Naik, S.; Elavalli, S.; Gopinath, P.; Ali, A.M.; Bazzi, L.; Warren, K.; Zaher, W.A.; et al. Immune response of booster doses of BBIBP-CORV vaccines against the variants of concern of SARS-CoV-2. J Clin Virol 2022, 150-151, 105161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannawi, S.; Saifeldin, L.; Abuquta, A.; Alamadi, A.; Mahmoud, S.A.; Hassan, A.; Liu, D.; Yan, L.; Xie, L. Safety and immunogenicity of a bivalent SARS-CoV-2 protein booster vaccine, SCTV01C, in adults previously vaccinated with mRNA vaccine: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 1/2 clinical trial. EBioMedicine 2023, 87, 104386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guidelines for grading adverse events in preventive vaccine clinical trials. (https://www.nmpa.gov.cn/xxgk/ggtg/ypggtg/ypqtggtg/20191231111901460.html). 2019.

- Khoury, D.S.; Cromer, D.; Reynaldi, A.; Schlub, T.E.; Wheatley, A.K.; Juno, J.A.; Subbarao, K.; Kent, S.J.; Triccas, J.A.; Davenport, M.P. Neutralizing antibody levels are highly predictive of immune protection from symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med 2021, 27, 1205–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalkias, S.; McGhee, N.; Whatley, J.L.; et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of XBB.1.5-Containing mRNA Vaccines. medRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COVID-19 Vaccines for 2023-2024. (https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/covid-19-vaccines-2023-2024).

- Poon, R.W.; Chan, B.P.; Chan, W.M.; Fong, C.H.; Zhang, X.; Lu, L.; Chen, L.L.; Lam, J.Y.; Cheng, V.C.; Wong, S.S.Y.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 IgG seropositivity after the severe Omicron wave of COVID-19 in Hong Kong. Emerg Microbes Infect 2022, 11, 2116–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, P.; Ujjainiya, R.; Prakash, S.; Naushin, S.; Sardana, V.; Bhatheja, N.; Singh, A.P.; Barman, J.; Kumar, K.; Gayali, S.; et al. A machine learning-based approach to determine infection status in recipients of BBV152 (Covaxin) whole-virion inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine for serological surveys. Comput Biol Med 2022, 146, 105419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).