1. Introduction

The European Green Deal poses a two-pronged challenge for the automotive industry: migrating to solutions based in light structures, requiring light weight concepts and light materials, while at the same time avoiding dependence towards the importation of these advanced materials.

Aluminium is a lightweight and cost-effective material, that can successfully cover the requirements of many structural applications. The use of aluminium in vehicles has been steadily growing over the last decades [

1], substituting steel and cast iron and making vehicles more efficient and less fuel demanding [

2]. As a reference, weight reduction potential of up to 20-30% was estimated by making use of high-performance aluminium grades when compared to traditional steel-based construction [

3]. However, these high-performance parts need to be produced in primary aluminium alloys requiring bauxite, as well as other alloying elements classified as sensitive by the CRM alliance, the most common of those being metallic Silicon (Si) and Magnesium (Mg).

While aluminium recycling is spread in the automotive industry, recycled alloys are currently not able to fulfil the properties required by structural applications due to limitations in their formability and mechanical performance. As a reference, a study from 2011 quantified in one third the amount of scrap used in the making of high-performance aluminium alloys [

4]. Moreover, the parts traditionally produced with intensive use of recycled aluminium (motor blocks, gear boxes, oil pans, valve covers) [

5] are not present in electrical vehicles. Therefore, a better understanding of the how scrap affects aluminium properties is required, in order to develop new high performance, environmentally and strategically sustainable aluminium grades and their forming processes, is fundamental for sustainable electrification of the automotive industry.

The assessment of the purity of aluminium alloys is critical for both quality and process control and is defined by the number of inclusions (native and/or exogenous particles) present in the molten metal [

6,

7]. Depending on the size and proportion of inclusions, i.e., single large inclusions or a large number of small inclusions, these can have a negative effect on the mechanical and chemical properties of the final product.

For cast products, in order to be able to produce the highest possible quality aluminium alloy, liquid metal preparation processes are carried out first [

8,

9]. These processes require effective purification and refining procedures, for which salt additives are used and refining is carried out by degassing [

6,

8,

9,

10,

11].

In the case of wrought products, material improvement needs to be done during the production of the intermediate format; e.g., hot rolling for a sheet metal grade, extrusion of a cast ingot through a die or shaping a bulk material through hot forging. All these hot forming processes change the cast microstructure into a more homogeneous and textured recrystallized morphology; correcting segregation while at the same time fragmenting inclusions and closing small voids. Despite these measures, the impurity content still affects the mechanical properties of the material. In the particular case of sheet metal, intermetallic particles can be detrimental to the formability of the alloy, as discussed for instance in references [

7,

12].

On the other hand, alternative processing strategies exist for high purity alloys, such as filtration. In this case, the casting process is carried out by pouring the liquid metal through appropriately selected ceramic filters [

6,

10]. By using this procedure, a significant amount of solid inclusions are entrapped in the filter and do not reach the product. This process can also be used as an analytical device to characterize the inclusion profile in an alloy; work in this paper has used this technique.

Great deal of research has already been done on the subject of inclusion analysis, which has led to a division into the main groups of impurities: oxide films, carbides, magnesium oxides, refractory materials, metal treatments, others, and additives [

10]. In the case of casting alloys, it has been shown that oxide films in solid aluminium alloys are formed by the entrainment of the surface of the metal in the liquid state. The oxide layers act as substrates for the precipitation of other phases on their wetted external surfaces. Oxides observed in Al-11.5Si-0.4Mg casting alloys include Al

2MgO

4, Al

2O

3 and MgO. Oxide is one of the most deleterious and pervasive inclusion types in Al-Mg melts. They are generally formed by oxidative reactions due to high oxygen affinity of aluminium and magnesium. In Al-Mg alloys, the tendency to oxidize increases rapidly with increasing Mg content. The oxidation reaction path depends on the amount of Mg and probably starts with the formation of amorphous MgO, MgAl

2O

4 or Al

2O

3, which then transforms into crystalline MgO, MgAl

2O

4 or γ-Al

2O

3 films. The high concentration of Mg on the alloy surface promotes initial oxidation to MgO. Moreover, since MgAl

2O

4 is more thermodynamically stable than MgO, MgO gives way to MgAl

2O

4 with longer reaction times [

13,

14]. The MgAl

2O

4 spinels are the most detrimental inclusions in aluminium because of their large size and hardness. Spinel Al

2MgO

4 is the main type in the experimental alloys, mainly due to its magnesium content. Aluminium oxide Al

2O

3 is formed either under conditions of local magnesium depletion or is derived from the feedstock. The MgO film can come from the original ingots. SiO

2 inclusions are trapped either in the sand or in the refractory material and are themselves surrounded by an oxide film [

15].

These oxide layers and inclusions are also present in wrought alloys. Samples of AA5038 alloys taken in the Wagstaff plant at a temperature of 680-690°C show Al

2O

3 content, which may originate from the electrolysis raw material (aluminium oxide not dissolved in the salt bath), or from the refractory filter or from the casting ladle. Spherical agglomerates of magnesium and aluminium silicate and TiB

2 particles formed from AlTi

5B

1 mortars were observed at the interface between the ceramic filter and the 5038 alloy [

9,

16].

Microscopic analysis of the inclusions above the filter as well as the billet samples showed the presence of magnesium oxides and spinels due to the Mg content of 0.4 to 0.55% in the 6063 alloys. In addition to the dominant oxides, TiB

2 and Al

4C

3 inclusions have also been observed. The carbides are formed during the reduction of the pot cells in the aluminium smelting process. Al

4C

3 <3 μm inclusions are not considered harmful. TiB2 agglomerates were present in significant amounts and formed as a result of the addition of the AlTi5B1 grain refiner to the melt. For alloys purified by SNIF degassing, it has been shown that oxides greater than 50 μm and borides greater than 20 μm are removed while smaller borides agglomerate [

6].

The chemical reactivity leading to the formation of impurities, their decomposition and size is mainly due to small changes in the chemical composition of the alloy and the conditions under which the process of preparing the liquid metal for casting is carried out [

6,

17]. Therefore, in the current research to achieve a zero waste effect, it becomes extremely valuable to know how to remelt scrap with maximum contribution.

This paper presents an analysis of the effect of increasing scrap content on the microstructure and formability on alloys for HDPC, sheet metal and extrusion processes. A Prefil Footprinter® was used to control the level of impurities by assessing the liquid metal flow rate and the type and size of impurities appearing in the microstructure as a function of the scrap content. Specific performance tests were employed on the different materials, including flowability for HPDC, hot compression ductility for extrusion alloys and microstructural evolution for sheet metal.

4. Discussion

In this study, the following series of alloys were tested in the processes: AB-43500 alloy for HPDC, 6063 for extrusion and 6181A, 5754 for stamping with different scrap. The effects of compression test at elevated and reduced temperatures on microstructure and properties were also investigated.

The effect of increasing scrap content on the properties of the alloys studied was comparable. An increase in various types of impurities with increasing scrap content was found in all alloy grades tested. Large differences between the AB-43500 casting alloy and the alloys for plastics processing were found in the rates of liquid metal flow through the Prefil Footprinter

® filter (

Figure 5 and

Figure 10). This appears to be related to the flowability of the alloys. Casting alloys, especially for HPDC casting, are characterised by very good flowability [

21,

22], which is also confirmed by the tests carried out in this study (

Table 8). It can also be concluded that an increasing amount of scrap leads to a decrease in flowability. However, the general microstructural analysis of the specimens did not reveal the presence of new phases or big foreign particles that could be observed in the light microscope, neither for HPDC (

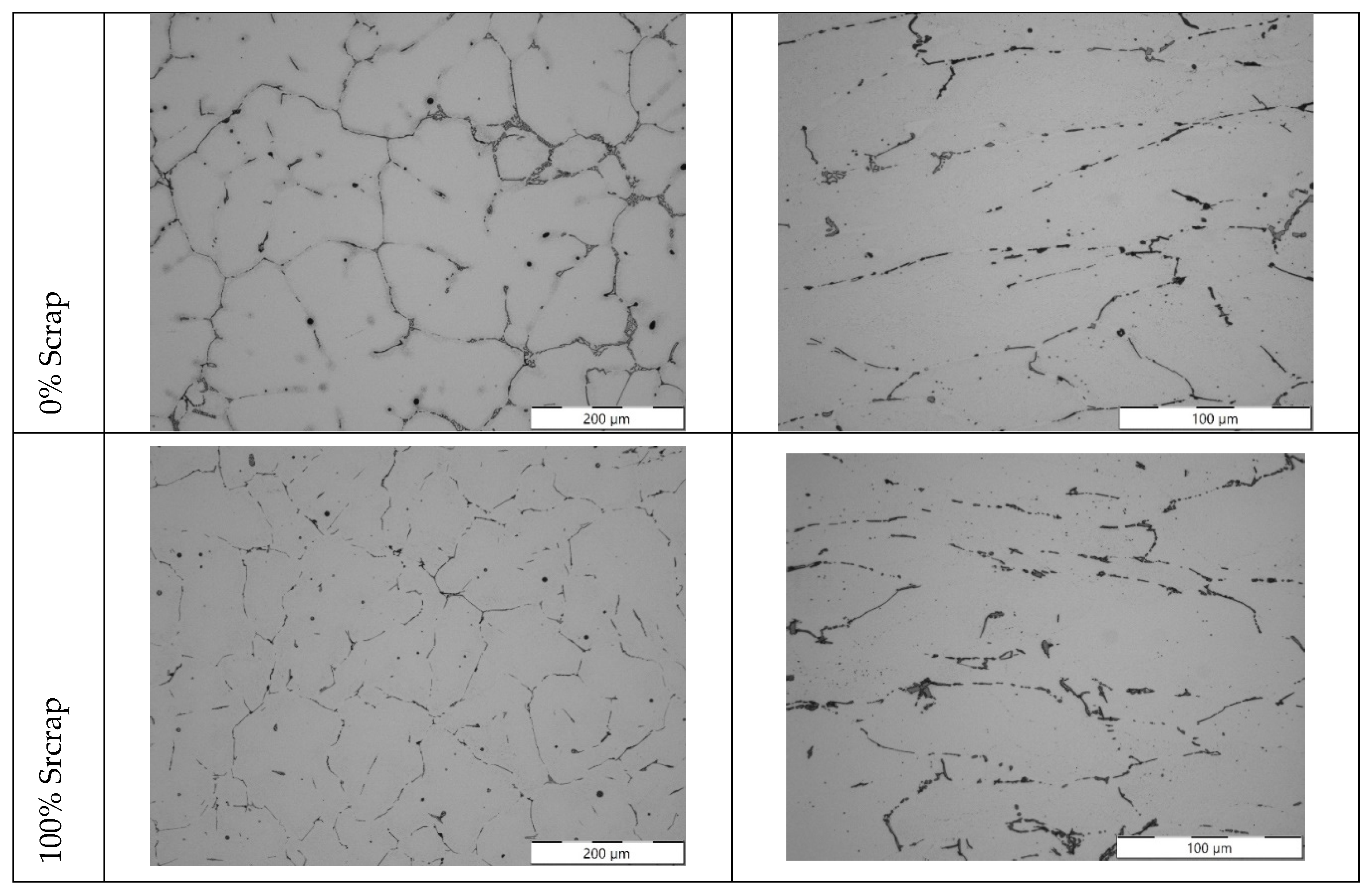

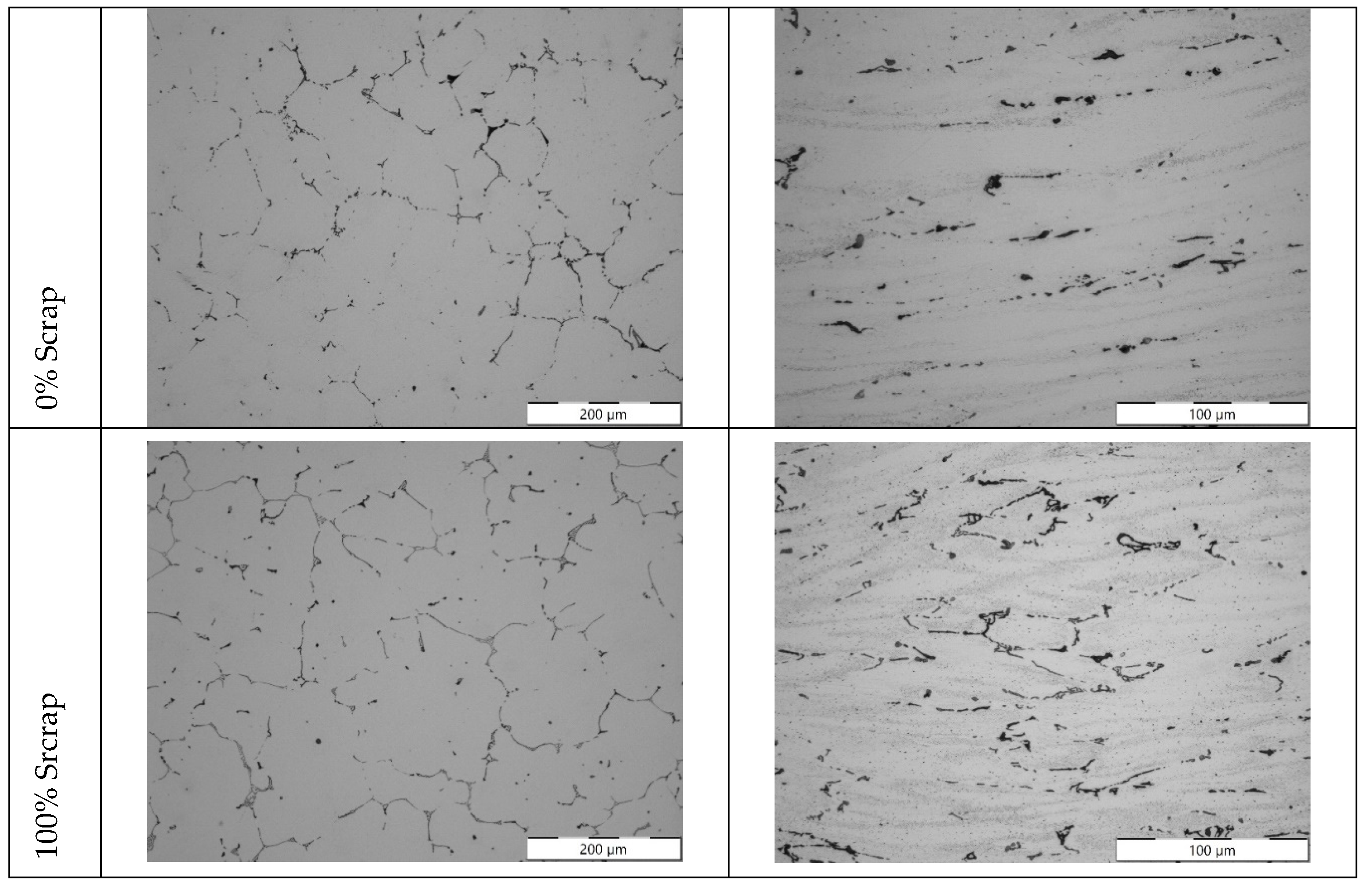

Figure 3) or the other processing routes investigated in the present work (

Figure 6,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12), even if these differences were detected in the more detailed Prefil Footprinter

® analysis, particularly in the case of HPDC. This suggests that the main difference is in the presence of small non-metallic particles, such as oxides, present in the scrap or generated by the oxidation produced during the melting process due to the presence of residues in the scrap. Even though this small contaminationdoes not translate into microstructural changes, it does highly affect alloy flowability.

Typical oxides in film and cuboid particle form were identified with different compositions. Metallographic examination of the filter for the AB-43500 alloy showed that the magnesium oxides content and refractory materials, which include Al

2O

3 and CaO, increased with the amount of scrap. According to studies [

6,

12,

22], these are typical impurities for this type of alloy due to the Mg content. The magnesium content increased with the addition of scrap. In the pure AB-43500 alloy it was 0.18 wt.%, while in the same alloy cast from 100% scrap it was 0.25 wt.%. Regarding to oxides from the refractory, they can enter the melt through abrasion of the furnace and channel lining, and are usually silicates or other complex oxides, which may also contain Na, K and Ca [

7,

15]. In addition to the prevalent oxides, (Ti,V)B2 inclusions also were observed. Especially in the case of alloys 6063 and 6181A, which are intended for extrusion and plastic stamping, despite the higher Mg content in the structure, additives, i.e., (Ti, V)B

2 agglomerations were present above the filter in a significant quantity. Their presence is confirmed by studies carried out by other researchers [

9]. In both our own research (

Figure 10) and that of others [

23,

24], borides have been found to inhibit the flow of liquid metal through the Prefil Footprinter

® filter. According to the authors of Yang et al. [

25] the reduction of efficiency is due to the strong adherence of TiB2 particles to oxide films in the filter. The adherence and agglomeration of heavy grain refiner particles onto light oxide films counter the gravitation number of oxide films, making them difficult to be filtrated [

25]. This can also lead to inhibition of the filtration process during alloy casting. TiB

2 inclusions are hard and have adverse effects on extrusion and machining tools [

6].

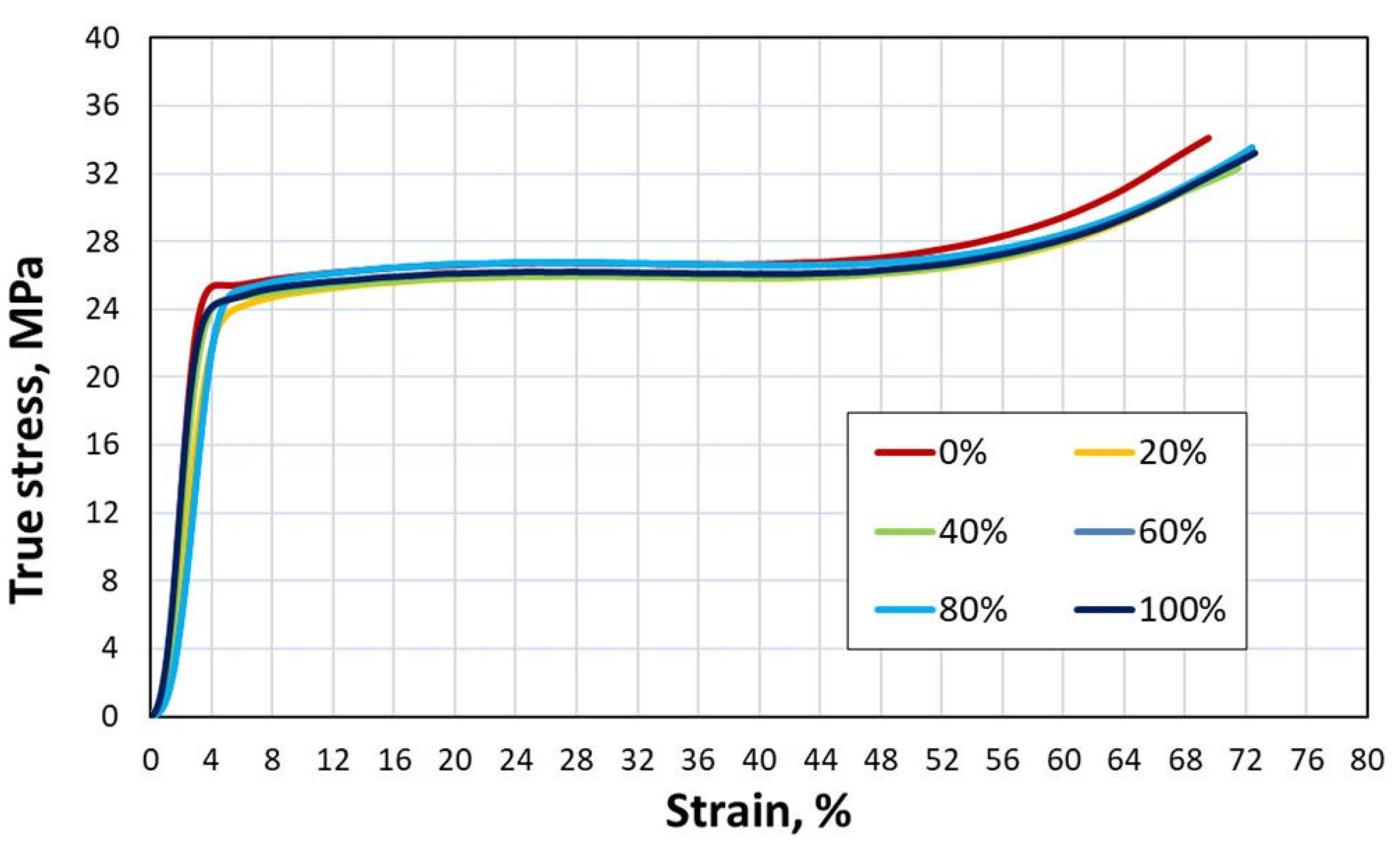

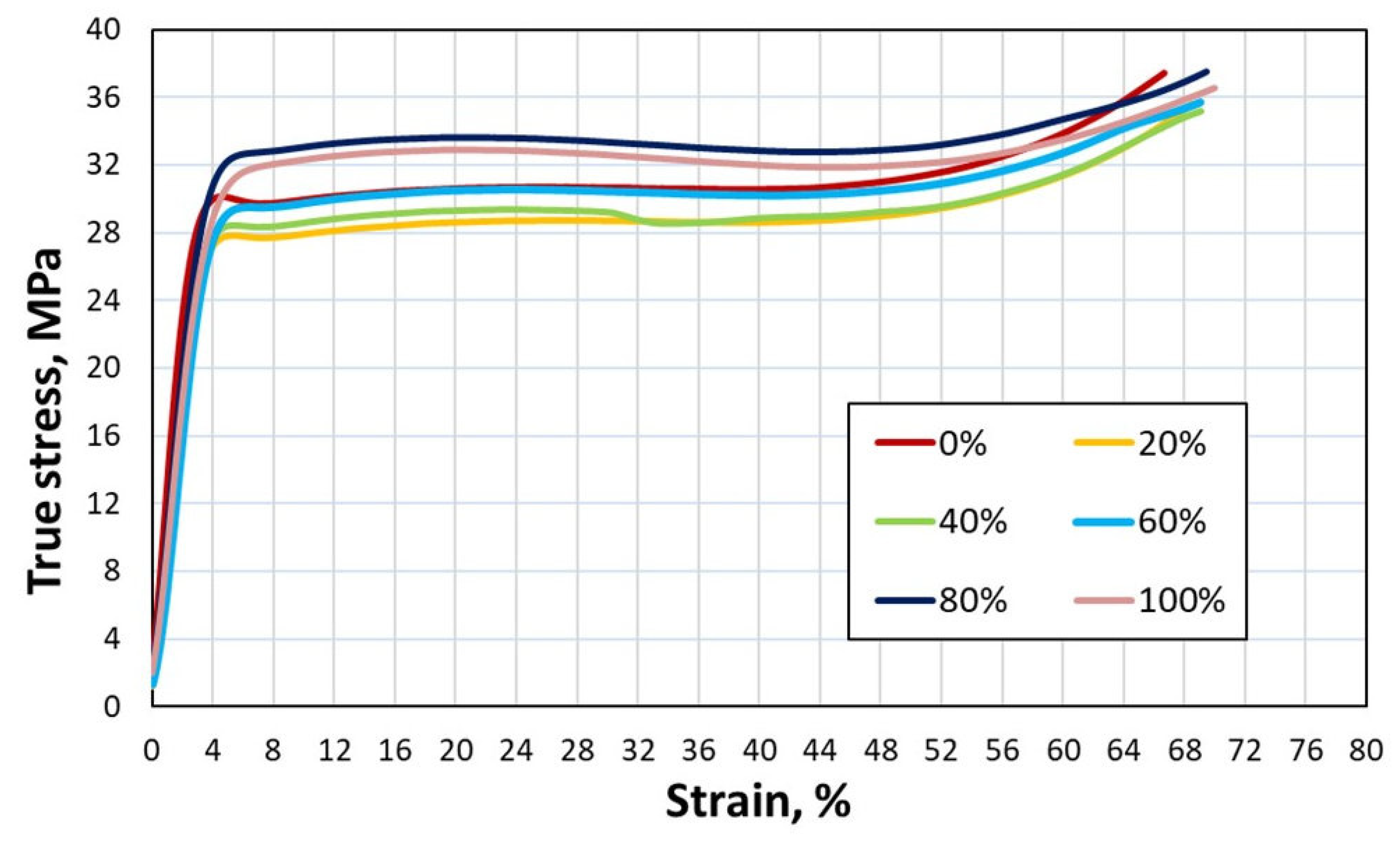

This can be confirmed by a slight increase in strength as the scrap content of the 6063 alloy increases during the compression test (

Figure 9 and

Figure 10). According to literature [

26] TiB

2 particles could tend to agglomerate which could lead to the formation of thick oxides. This is related to the presence of a superficial aluminide layer in Al-Ti-B. Therefore, it is necessary to check the chemical composition with regard to Ti and B content before the casting process to overcome particle agglomeration problems. In addition, 6181A alloy contained MgO due to its even higher Mg content.

In the 5754 and 6181A alloys, high levels of impurities such as magnesium and aluminium oxides and additives were found after the addition of 100% scrap. This is particularly true for 5754. In Al-Mg alloys, the tendency to oxidize increases rapidly with increasing Mg content [

13,

14]. The results obtained during the analysis (

Figure 15) are consistent considering the high magnesium content of this alloy, as can be observed in the chemical analysis of the ingots presented in

Table 8, where the Mg level decreased with each recycling step. It is likely that some of the added Mg, as well as the alloying elements already present in the melt, were lost to the slag during melting experiments.

In addition, presence of carbides was revealed (

Figure 15 and

Figure 16). According to literature [

7] melting scraps with organic contaminations can lead to an increased amount of carbide formation. During the smelting process, organic impurities can react with aluminium and other elements. These reactions can lead to the formation of carbides in the alloy. The recycling-friendly coating removal practices proposed by the authors [

27] which involve thermal treatment (pyrolysis) of scrap before it is smelted, may avoid this problem.

Studies relating to the thermo-mechanical treatment of alloys for the stamping process did not reveal any effect of scrap content on properties, despite the variations in chemical composition. Alloy 5754 showed strengthening due to cold work, reaching about 95 HV1 hardness for the three compared compositions despite decreasing Mg content. Similarly, 6181A showed similar level of age hardening after a treatment cycle. The study shows that an alloy produced with 100% scrap content will not adversely affect the mechanical properties, as long as chemical composition is kept within reasonable ranges.

This observation is consistent with the results of reference [

12]: in that work, increased recycling content of alloy 6181 did not result in modification of monotonic mechanical properties, even though it did result in a loss of formability in terms of FLD curve.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.dS. (Manel da Silva) and J.P. (Jaume Pujante); methodology, M.dS, J.P., J.H.-W. (Joanna Hrabia-Wiśnios), B.A. (Bogusław Augustyn), D.K. (Dawid Kapinos), M.W. (Mateusz Węgrzyn); validation, M.dS, J.P., J.H.-W., S.B. (Sonia Boczkal); formal analysis, M.dS, J.P., S.B., J.H.-W.; investigation, M.dS, J.P., J.H.-W.; B.A., D.K., M.W. resources, M.dS., J.H.-W., S.B.; data curation, M.dS, J.P., J.H.-W, S.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.dS., J.P.; writing—review and editing, M.dS., J.P., S.B., J.H.-W., B.A., D.K.; visualization, M.dS., J.P., S.B., J.H.-W.; supervision, M.dS.; project administration, M.DS.; funding acquisition, M.DS. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Images of the different sample taken for the tests: square plate (left), small ingot (middle) and flowability test specimen (right).

Figure 1.

Images of the different sample taken for the tests: square plate (left), small ingot (middle) and flowability test specimen (right).

Figure 2.

Images of the Prefil Footprinter

® equipment: scheme of the equipment [

8] with the different parts and steps of the test (left), picture of the crucible (middle) and picture of the screen (right).

Figure 2.

Images of the Prefil Footprinter

® equipment: scheme of the equipment [

8] with the different parts and steps of the test (left), picture of the crucible (middle) and picture of the screen (right).

Figure 3.

Microstructures obtained by light microscope for the most extreme batches produced for EN AB-43500 alloy: 0% scrap (left), and 100% scrap (right).

Figure 3.

Microstructures obtained by light microscope for the most extreme batches produced for EN AB-43500 alloy: 0% scrap (left), and 100% scrap (right).

Figure 4.

Microstructure (a) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) maps (b-i) of distribution of elements: Al, Si, Mg, O, Ti, V, C, Ca, SEM of the EN AB-43500 alloy.

Figure 4.

Microstructure (a) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) maps (b-i) of distribution of elements: Al, Si, Mg, O, Ti, V, C, Ca, SEM of the EN AB-43500 alloy.

Figure 5.

Analysis of inclusions in AB-43500 alloy variants: a) summary of identified inclusions and quantification of oxides; b) microstructure with identified types of inclusions in a sample containing 20% scrap; c) microstructure with identified types of inclusions in a sample containing 80% scrap; LM.

Figure 5.

Analysis of inclusions in AB-43500 alloy variants: a) summary of identified inclusions and quantification of oxides; b) microstructure with identified types of inclusions in a sample containing 20% scrap; c) microstructure with identified types of inclusions in a sample containing 80% scrap; LM.

Figure 6.

Microstructures obtained by light microscope for the most extreme batches produced for 6063 alloy: 0% scrap (left), and 100% scrap (right).

Figure 6.

Microstructures obtained by light microscope for the most extreme batches produced for 6063 alloy: 0% scrap (left), and 100% scrap (right).

Figure 7.

Analysis of inclusions in 6063 extrusion alloy variants: a) summary of identified inclusions and quantification of oxides; b) microstructure with identified types of inclusions in a sample containing 20% scrap; c) microstructure with identified types of inclusions in a sample containing 80% scrap; LM.

Figure 7.

Analysis of inclusions in 6063 extrusion alloy variants: a) summary of identified inclusions and quantification of oxides; b) microstructure with identified types of inclusions in a sample containing 20% scrap; c) microstructure with identified types of inclusions in a sample containing 80% scrap; LM.

Figure 8.

Microstructure (a) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) maps (b-i) of distribution of elements: Al, Si, Mg, O, Ti, V, C, Ca, SEM of the 6063 extrusion alloy.

Figure 8.

Microstructure (a) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) maps (b-i) of distribution of elements: Al, Si, Mg, O, Ti, V, C, Ca, SEM of the 6063 extrusion alloy.

Figure 9.

True stress-strain curves from compression tests crosshead speed 250 mm/min.

Figure 9.

True stress-strain curves from compression tests crosshead speed 250 mm/min.

Figure 10.

True stress-strain curves from compression tests crosshead speed 450 mm/min.

Figure 10.

True stress-strain curves from compression tests crosshead speed 450 mm/min.

Figure 11.

Microstructures for the different batches produced for 6181A alloy: extreme cases of 0 and 100% scrap as cast (left column) and after processing by 40 % hot deformation and 65 % cold reduction (left column).

Figure 11.

Microstructures for the different batches produced for 6181A alloy: extreme cases of 0 and 100% scrap as cast (left column) and after processing by 40 % hot deformation and 65 % cold reduction (left column).

Figure 12.

Microstructures for 5754 alloy: extreme cases of 0 and 100 % scrap as cast (left column) and after processing by 40 % hot deformation and 65 % cold reduction (left column).

Figure 12.

Microstructures for 5754 alloy: extreme cases of 0 and 100 % scrap as cast (left column) and after processing by 40 % hot deformation and 65 % cold reduction (left column).

Figure 13.

Microstructure (a) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) maps (b-i) of distribution of elements: Al, Si, Mg, O, Ti, V, C, Ca, SEM of the 6181 alloy.

Figure 13.

Microstructure (a) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) maps (b-i) of distribution of elements: Al, Si, Mg, O, Ti, V, C, Ca, SEM of the 6181 alloy.

Figure 14.

Analysis of inclusions in 6181A variants: a) Summary of identified inclusions and quantification of oxides; b) identification of refractory inclusions, carbides and additions on a 40% scrap sample; c) magnesium oxides (thin and layer-like) in 80% scrap sample.

Figure 14.

Analysis of inclusions in 6181A variants: a) Summary of identified inclusions and quantification of oxides; b) identification of refractory inclusions, carbides and additions on a 40% scrap sample; c) magnesium oxides (thin and layer-like) in 80% scrap sample.

Figure 15.

Microstructure (a) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) maps (b-i) of distribution of elements: Al, Si, Mg, O, Ti, V, C, Ca, SEM of the 5754 alloy.

Figure 15.

Microstructure (a) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) maps (b-i) of distribution of elements: Al, Si, Mg, O, Ti, V, C, Ca, SEM of the 5754 alloy.

Figure 16.

Analysis of inclusions in 5754 variants: a) Summary of identified inclusions and quantification of oxides; b) identification of refractory inclusions, carbides and additions on a 40% scrap sample; c) high presence of magnesium oxides and oxide films in 100% scrap sample.

Figure 16.

Analysis of inclusions in 5754 variants: a) Summary of identified inclusions and quantification of oxides; b) identification of refractory inclusions, carbides and additions on a 40% scrap sample; c) high presence of magnesium oxides and oxide films in 100% scrap sample.

Table 1.

Average chemical composition (wt.%) of the alloys used in this work determined by mass spectrometry.

Table 1.

Average chemical composition (wt.%) of the alloys used in this work determined by mass spectrometry.

| n=5 |

Si |

Fe |

Cu |

Mn |

Mg |

Zn |

Cr |

Ni |

Pb |

Sn |

Ti |

| EN AB-43500 |

10.40 |

0.16 |

0.03 |

0.65 |

0.18 |

<0.01 |

<0.01 |

<0.01 |

<0.01 |

<0.01 |

0.07 |

| 6063 |

0.58 |

0.2 |

<0.03 |

0.03 |

0.48 |

|

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

|

<0.03 |

|

| 6181A |

0.91 |

0.027 |

0.14 |

0.3 |

0.76 |

0.06 |

0.02 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

| 5754 |

0.14 |

0.16 |

0.02 |

0.16 |

2.86 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

Table 2.

Average chemical composition (wt.%) of scrap used in this work as determined by mass spectrometry.

Table 2.

Average chemical composition (wt.%) of scrap used in this work as determined by mass spectrometry.

| n=5 |

Si |

Fe |

Cu |

Mn |

Mg |

Zn |

Cr |

Ni |

Pb |

Sn |

Ti |

| Die Casting scrap |

10.81 |

0.15 |

0.01 |

0.62 |

0.26 |

0.01 |

<0.01 |

<0.01 |

<0.01 |

<0.01 |

0.07 |

| “6XXX” scrap |

0.45 |

0.23 |

0.01 |

0.04 |

0.43 |

0.01 |

<0.01 |

<0.01 |

<0.01 |

<0.01 |

0.02 |

Table 3.

Average chemical composition (wt.%) determined by mass spectrometry of samples taken from the different batch produced from EN AB-43500 alloy.

Table 3.

Average chemical composition (wt.%) determined by mass spectrometry of samples taken from the different batch produced from EN AB-43500 alloy.

| n=5 |

Si |

Fe |

Cu |

Mn |

Mg |

Zn |

Cr |

Ni |

Pb |

Sn |

Ti |

| 0% scrap |

10.34 |

0.17 |

0.03 |

0.58 |

0.18 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.01 |

<0.01 |

0.06 |

| 20% scrap |

10.29 |

0.16 |

0.02 |

0.58 |

0.18 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.01 |

<0.01 |

0.06 |

| 40% scrap |

10.25 |

0.16 |

0.02 |

0.56 |

0.19 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.01 |

<0.01 |

0.06 |

| 60% scrap |

10.1 |

0.16 |

0.03 |

0.53 |

0.21 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.01 |

<0.01 |

0.06 |

| 80% scrap |

10.22 |

0.17 |

0.03 |

0.54 |

0.23 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.01 |

<0.01 |

0.06 |

| 100% scrap |

10.01 |

0.14 |

0.03 |

0.51 |

0.25 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.01 |

<0.01 |

0.06 |

| EN AB-43500 |

9-11.5 |

<0.20 |

<0.03 |

0.4-0.8 |

0.15-0.6 |

<0.07 |

<0.05 |

<0.05 |

<0.05 |

<0.05 |

<0.15 |

Table 4.

Average chemical composition (wt.%) determined by mass spectrometry of samples taken from the different batch produced from 6063 alloy.

Table 4.

Average chemical composition (wt.%) determined by mass spectrometry of samples taken from the different batch produced from 6063 alloy.

| n=5 |

Si |

Fe |

Cu |

Mn |

Mg |

Zn |

Cr |

Ni |

Pb |

Sn |

Ti |

| 0% scrap |

0.8 |

0.2 |

0.02 |

0.05 |

0.48 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

| 20% scrap |

0.72 |

0.21 |

0.02 |

0.05 |

0.47 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

| 40% scrap |

0.62 |

0.21 |

0.02 |

0.05 |

0.47 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

| 60% scrap |

0.51 |

0.23 |

0.01 |

0.05 |

0.45 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

| 80% scrap |

0.51 |

0.23 |

0.02 |

0.06 |

0.45 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

| 100% scrap |

0.5 |

0.23 |

0.02 |

0.06 |

0.43 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

Table 5.

Average chemical composition (wt.%) determined by mass spectrometry of samples taken from the different batch produced from 6181A alloy.

Table 5.

Average chemical composition (wt.%) determined by mass spectrometry of samples taken from the different batch produced from 6181A alloy.

| N=5 |

Si |

Fe |

Cu |

Mn |

Mg |

Zn |

Cr |

Ni |

Pb |

Sn |

Ti |

| 0% scrap |

0.88 |

0.32 |

0.13 |

0.29 |

0.74 |

0.06 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

| 20% scrap |

0.92 |

0.33 |

0.11 |

0.25 |

0.76 |

0.08 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

| 40% scrap |

0.95 |

0.32 |

0.10 |

0.22 |

0.71 |

0.08 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

| 60% scrap |

0.96 |

0.29 |

0.06 |

0.14 |

0.68 |

0.08 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

| 80% scrap |

1.00 |

0.27 |

0.05 |

0.10 |

0.66 |

0.08 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

| 100% scrap |

1.07 |

0.26 |

0.03 |

0.06 |

0.65 |

0.08 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

Table 6.

Average chemical composition (wt.%) determined by mass spectrometry of samples taken from the different batch produced from 5754 alloy.

Table 6.

Average chemical composition (wt.%) determined by mass spectrometry of samples taken from the different batch produced from 5754 alloy.

| n=5 |

Si |

Fe |

Cu |

Mn |

Mg |

Zn |

Cr |

Ni |

Pb |

Sn |

Ti |

| 0% scrap |

0.18 |

0.29 |

0.02 |

0.16 |

2.78 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

| 20% scrap |

0.23 |

0.28 |

0.03 |

0.18 |

2.72 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

| 40% scrap |

0.25 |

0.26 |

0.04 |

0.19 |

2.66 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

| 60% scrap |

0.35 |

0.28 |

0.06 |

0.21 |

2.49 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

| 80% scrap |

0.39 |

0.27 |

0.06 |

0.22 |

2.44 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

| 100% scrap |

0.43 |

0.28 |

0.07 |

0.23 |

2.37 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

<0.03 |

Table 7.

Length measured for the 6 strips of the flowability specimen and average value.

Table 7.

Length measured for the 6 strips of the flowability specimen and average value.

| |

1 mm |

3 mm |

5 mm |

7 mm |

9 mm |

11 mm |

Average |

| Ref. ingot |

0 |

135 |

35 |

135 |

60 |

85 |

75.00 |

| 20% scrap |

0 |

100 |

55 |

110 |

95 |

70 |

71.67 |

| 40% scrap |

0 |

90 |

40 |

80 |

65 |

60 |

55.83 |

| 60% scrap |

0 |

130 |

30 |

105 |

75 |

20 |

60.00 |

| 80% scrap |

0 |

40 |

5 |

70 |

20 |

0 |

22.50 |

| 100% scrap |

0 |

70 |

5 |

75 |

20 |

10 |

30.00 |

Table 8.

Values obtained from the Prefil Footprinter® test of the EN AB-43500 alloy.

Table 8.

Values obtained from the Prefil Footprinter® test of the EN AB-43500 alloy.

| Samples |

0%

scrap |

20%

scrap |

40%

scrap |

60%

scrap |

80%

scrap |

100% scrap |

| Weight (kg) |

1.416 |

1.432 |

1.406 |

1.415 |

1.403 |

1.402 |

| Duration (s) |

85 |

100 |

109 |

112 |

134 |

140 |

| Filtration rate (g/s) |

16.7 |

14.3 |

12.9 |

12.6 |

10.5 |

10.0 |

Table 9.

Values obtained from the Prefil Footprinter® test of the 6063 extrusion alloy.

Table 9.

Values obtained from the Prefil Footprinter® test of the 6063 extrusion alloy.

| Samples |

0%

scrap |

20%

scrap |

40%

scrap |

60%

scrap |

80%

scrap |

100%

scrap |

| Weight (kg) |

0.687 |

0.632 |

0.77 |

0.649 |

0.747 |

0.749 |

| Duration (s) |

150 |

150 |

150 |

150 |

150 |

150 |

| Filtration rate (g/s) |

4.6 |

4.2 |

5.1 |

4.3 |

5.0 |

5.0 |

Table 10.

Values obtained from the Prefil Footprinter® test in 6181A variants.

Table 10.

Values obtained from the Prefil Footprinter® test in 6181A variants.

| Samples |

0%

scrap |

20%

scrap |

40%

scrap |

60%

scrap |

80% s

crap |

100% scrap |

| Weight (kg) |

1.127 |

1.287 |

1.323 |

1.247 |

1.273 |

0.934 |

| Duration (s) |

150 |

150 |

150 |

150 |

150 |

150 |

| Filtration rate (g/s) |

7.5 |

8.6 |

8.8 |

8.3 |

8.5 |

6.2 |

Table 11.

Values obtained from the Prefil Footprinter® test in 5754 variants.

Table 11.

Values obtained from the Prefil Footprinter® test in 5754 variants.

| Samples |

0%

scrap |

20%

scrap |

40%

scrap |

60%

scrap |

80%

scrap |

100%

scrap |

| Weight (kg) |

1.115 |

1.272 |

1.236 |

1.217 |

1.232 |

1.278 |

| Duration (s) |

150 |

150 |

150 |

150 |

150 |

150 |

| Filtration rate (g/s) |

7.4 |

8.5 |

8.2 |

8.1 |

8.2 |

8.5 |

Table 12.

Hardness values measured on 6181A-based samples.

Table 12.

Hardness values measured on 6181A-based samples.

| |

Hot Formed |

Aged |

| Scrap level |

% Reduction |

HV1 |

Treatment |

HV1 |

| 0% |

42% |

66 ± 2 |

1h 200 °C |

86 ± 3 |

| 40% |

35% |

67 ± 3 |

1h 200 °C |

84 ± 3 |

| 100% |

44% |

67 ± 3 |

1h 200 °C |

82 ± 3 |

Table 13.

Hardness values measured on 5754-based samples.

Table 13.

Hardness values measured on 5754-based samples.

| |

Hot Formed |

Cold Worked |

| Scrap level |

% Reduction |

HV1 |

% Reduction |

HV1 |

| 0% |

35% |

71 ± 3 |

66% |

94 ± 3 |

| 40% |

35% |

71 ± 3 |

67% |

94 ± 3 |

| 100% |

42% |

85 ± 3 |

64% |

95 ± 3 |