1. Introduction

The famous quote “information is the resolution of uncertainty” is often attributed to Claude Shannon. What Shannon’s seminal 1948 article

A mathematical theory of communication and the above quote indicate is that information is a potential: unresolved order that can be perceived, filtered, deciphered and transformed. Shannon had previously equated information with the term “intelligence” in his 1939 correspondence with Vannevar Bush (

Rogers, 1994), though his observation is but one essential part of intelligence, the other being the ability to attain goals in diverse environments (

Legg and Hutter, 2007). By associating these concepts, one arrives at a simple, general description of intelligence: the ability to resolve uncertainty, producing a definable result or goal. Indeed, this statement contains two of the oft-cited definitions of intelligence: attaining goals, and the ability to attain goals. My objective is to unpack this general description and to propose an information-based framework to help guide our understanding of intelligence.

Intelligent entities have one or more models of the world (e.g.,

Albus, 1991,

Hawkins, 2021,

LeCun, 2022). Simply possessing a model however does not necessarily invoke what most humans would regard as intelligence. Thus, systems from atoms to molecules to gasses, liquids and solids are all governed by physical laws – models of a sort – but these laws are reactive: except under special circumstances, gasses, liquids and solids cannot generate structure spontaneously and they do not have the predictive ability and goal directedness usually associated with (human) intelligence. Nevertheless, the laws of physics and chemistry can be driven to a local reduction in entropy, that is, decreased uncertainty (

Brillouin, 1953) and therefore a most bare-bones instantiation of intelligence – the extraction and materialization of information (

Landauer, 1991). Natural (non-programmed) physical systems do not make goals, nor can they actively choose among alternative paths or check and rectify errors towards goals. Predicting environments and reducing errors at different organizational levels is part of what differentiates thinking from non-thinking systems such as computers and AI (

Tononi and Koch, 2015,

Hohwy, 2016). Computers and artificial intelligence – even if capable of impressive feats from a human perspective – have models (e.g., software, algorithms) that are far simpler than biological systems, and humans in particular (

Roitblat, 2020,

Goyal and Bengio, 2022). Among the features added in the many, huge and fuzzy steps from machine intelligence to human intelligence are dynamic environmental sensitivity and active inference (

Korteling et al., 2021).

These and other complexities present a major challenge to developing a general theory of intelligence (

Duncan et al., 2017,

Barbey, 2018,

Stemler and Naples, 2021) applicable to both biological (

Epstein, 2016) and artificial (

Carabantes, 2020,

Bodria et al., 2021) systems. Intelligence theory has largely focused on humans, identifying different milestones from simple reactions through to the more elaborate, multi-level processes involved in thought. Raymond Cattell distinguished acquired and active components of intelligence in humans, defining crystallized intelligence as the ability to accumulate and recall knowledge (much like a computer), and fluid intelligence as abilities to learn new skills and to apply knowledge to new situations (a thinking entity) (

Cattell, 1963). Though an oversimplification of the many factors and interactions forming intelligence (

McGrew and Wendling, 2010,

Flanagan and Dixon, 2014), this basic dichotomy is useful in differentiating the functional significance of storage/recall to familiar situations versus prediction and active decision making when faced with novel circumstances (

Parr et al., 2022). The more recent “network neuroscience theory” takes a mesoscopic approach in linking network structure with memory and reasoning components of intelligence (

Barbey, 2018), but is impractical for dissecting exhaustive pathways and more efficient short-cuts. Other theories of intelligence have been centered on one or more of system organization, functional processes, emergent behaviors or achievements (e.g.,

Albus, 1991,

Sternberg, 1984,

Goertzel, 1993,

Legg and Hutter, 2007,

Georgiou et al., 2020). Arguably, the main shortcoming of current theory is the view that the reference for intelligence is humans, thus ignoring structural features linking physics, different milestones and scales in biology and artificial or designed systems (

Levin, 2022), and, with notable exceptions (

Hendriks-Jansen, 1996,

Flinn et al., 2005,

Roth and Dicke, 2005,

Sterelny, 2007,

Reader et al., 2011,

Burkart et al., 2017,

Shreesha and Levin, 2023), ignoring the pivotal roles of history, transmission and evolution in intelligence.

I develop the idea that intelligence is a fundamental property of

all systems, and can be categorized in a small number of distinct, distinguishing forms. Previous research has explained intelligence in layers, levels or hierarchies (e.g.,

Albus, 1991,

LeCun, 2022,

Spearman, 1904,

Carroll, 1993,

Conrad, 1996,

Adams et al., 2012,

Deary, 2014,

Chollet, 2019,

Burgoyne et al., 2022,

Friston et al., 2024) and although focusing on humans, I employ this idea to account for intelligence phenomena in natural physical systems, biological ones and humans in particular, and artificial and designed systems. I define a system (also referred to as an agent or individual) as an out-of-equilibrium entity, possibly complex (

Ladyman et al., 2013), possibly capable of autonomy, that uses external energy sources to maintain or lower the entropy of structure, function or behavior, and/or of one or more external systems or objects (

Brooks et al., 1989). Generic examples include development, obtaining resources, reproducing, and maintaining homeostasis. When a system uses free energy to generate (and eventually maintain) order, it does so through intelligence embedded in the genotype, (extended) phenotype, or actively expressed by the entity (

Odling-Smee et al., 2013).

The framework for a Theory of Intelligences (TIS) connects several concepts and is developed in three parts, starting with temporal goal resolution, then recognizing challenges and micro-, meso- and macroscopic abilities, and finally accounting for system-life-long changes in intelligence and transmission through time, including the Darwinian evolution of intelligence traits. The key advances of TIS are (1) proposing information as the unit for intelligence; (2) the partitioning of intelligence into local (“solving”) and beyond-local (“planning”) strategies; (3) distinguishing challenges in the forms of non-mutually exclusive goal novelty (never before encountered) and surprisal (improbable); (4) recognizing not only the core system, but extra-object spaces, including past sources, present proxies (i.e., any support including extrinsic systems), environments, individual system history, present and near-future transmission, and longer-term evolution.

As a start towards a formalization of TIS, I present descriptions based on the quantifiable system features of solving and planning, difficulty, and efficient, accurate and complete goal resolution. Goals may be imposed by necessity, such as survival imperatives, and/or be opportunistic or actively defined by the system, such as preferences, learning new skills, or goal definition itself. Solving and planning have been extensively discussed in the intelligence literature, and the advance of TIS is to begin to formalize their contributions to intelligence and to represent how, together with efficiency, accuracy and completeness, they constitute a parsimonious representation of intelligence. The proposed partitioning of solving and planning is particularly novel since it suggests that paths to a goal not only function to achieve goals, but also may constitute experimentations leading to higher probabilities for future attainable goals and increased breadth to enter new goal spaces, and possibly serving as a generator of variations upon which future selection will act. These experimentations moreover are hypothesized to explain capacities and endeavors that do not directly affect Darwinian fitness, such as leisure, games and art.

My presentation is inspired to some extent by cybernetics and algorithmic intelligence, which evidently apply to certain artificial systems. But as I argue and has been recently discussed (

Goyal and Bengio, 2022,

Adami, 2023), even if underlying process and structures and observable behaviors differ considerably between biological and current artificial systems, both have in common the dynamics of information (

Brooks et al., 1989). I do not discuss in any detail specific natural physical, AI or biological systems. Nor do I present the many theories of intelligence or the many ways to quantify intelligence, the latter for which the recent overview by Hernández-Orallo (

Hernández-Orallo, 2017) sets the stage for AI, but also yields insights into animal intelligence and humans. Neither do I discuss in any detail the many important, complex phenomena in thinking systems such as cognition, goal directedness and agency (

Goyal and Bengio, 2022,

Pezzulo and Cisek, 2016,

Babcock and McShea, 2023). I recognize but only address part of the full spectrum of intelligences, including (1) in different systems with different behaviors and goals (natural physical, biological, AI); (2) in different layers of a given system (solving and planning); (3) at different scales (within-individual, individual, collective); (4) at different temporal scales (history, transmission, evolution); problem types (food acquisition, predator avoidance); (5) and intelligence types (emotion, problem solving, athletic, artistic...). Finally and importantly, my approach is to focus on single systems and single goals, and to represent the key notion of “information” as a single, bulk quantity. I leave more empirically-rooted approaches using for example statistical physics to modeling information (

Rivoire and Leibler, 2011) for future work.

1.1. The Idea

My argument is that goals and the means to attain them are informational constructs. The “means” are what we usually associate with intelligence, that is, correctly guessing the answer to a hard problem may bring recompense (e.g., survival), but the basis of the answer will not be retained for future reliable use (e.g., its fitness is zero). Thus, when I use the terms goal information or goal complexity below, I am referring to

the path to the goal, which may or may not associate with information or complexity in the objective itself (the so-called “depth” (

Lloyd and Pagels, 1988). Because the means to attain goals can be complex (modular, multidimensional, multi-scale), two fundamental macroscopic capacities potentially contribute to resolutions. These are: (1) the ability to resolve local uncertainty (“solving”) and (2) the ability to partition a complex goal into a set or sequence of subgoals fostering goal attainment (“planning”) (

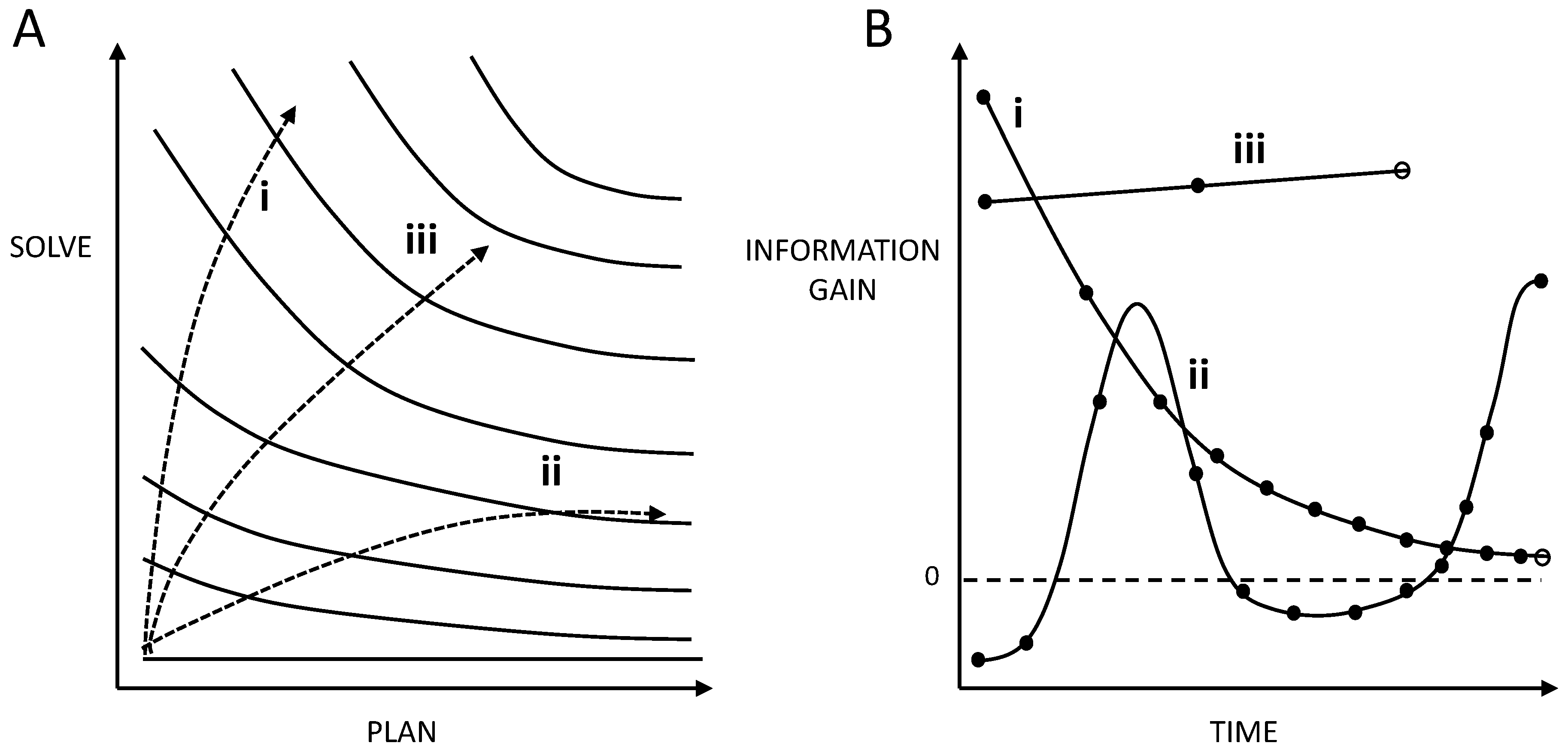

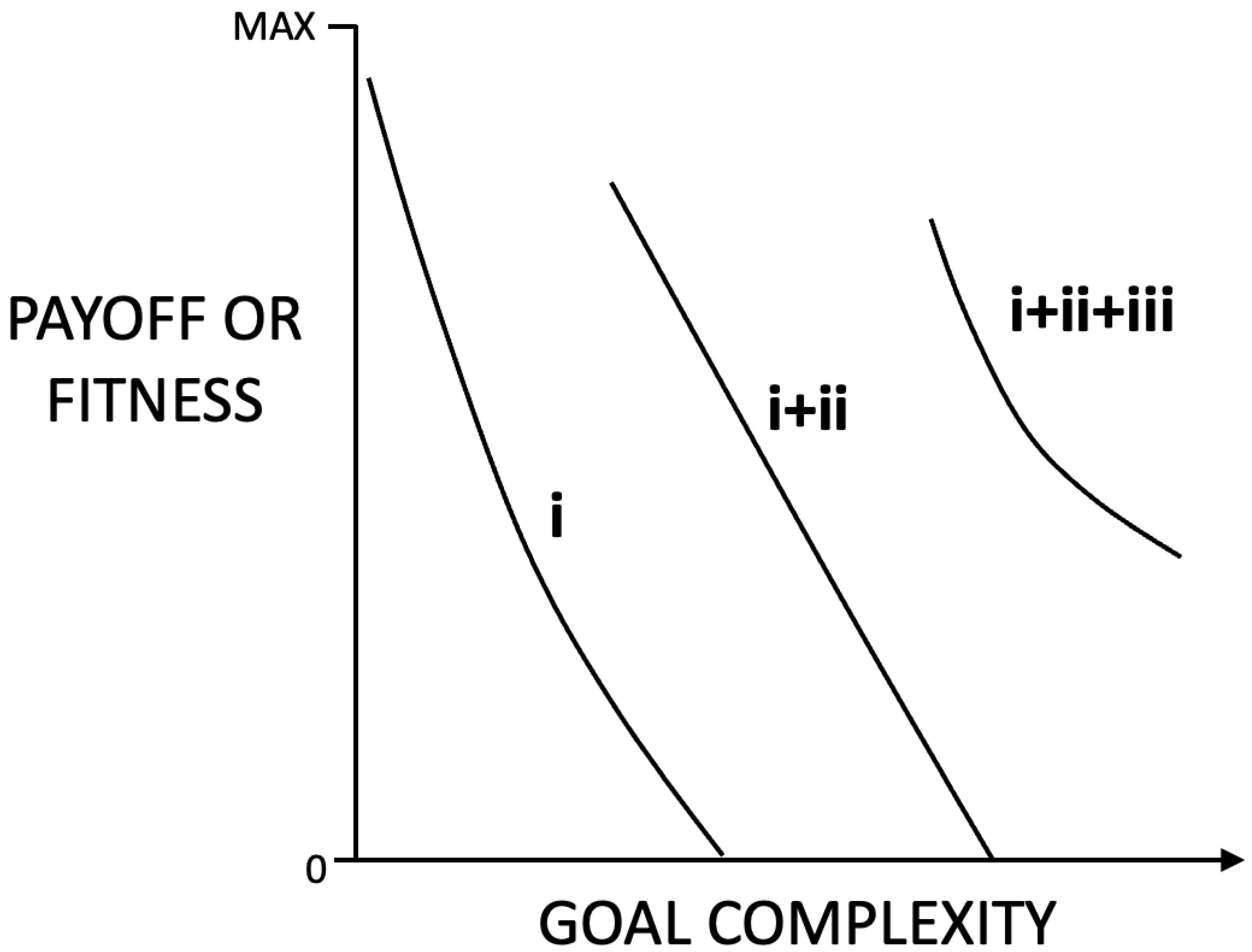

Figure 1).

Briefly, both solving and planning harness priors, knowledge and skills, but solving focuses on the myopic resolution of manageable, more or less distinct, goal elements, whereas planning is the broader assessment of alternative steps to attain goals. Thus solving and planning contribute to attaining goals, but a different scales. Planning is a manifestation of the “adjacent possible” (

Kauffman, 2000), whereby the cost of ever-future horizons is (hyper)exponentially increasing uncertainty. Not surprisingly therefore, planning is expected to require more working memory (and for hierarchical planning, causal representations of understanding) than does solving (

Albus, 1991,

Duncan et al., 2017,

Hommel et al., 2001). Planning could be influenced by a system’s ability to solve individual subgoals (including how particular choices affect future subgoals), though this does not mean that planning is necessarily harder than solving. And excellent solving ability alone could be sufficient to attain goals (i.e., solving is necessary and sometimes sufficient), whereas the capacity to identify the most promising path alone may or may not be necessary and is

not sufficient to resolve a goal (

Figure 1A). The value added of the latter capacity is increased efficiency, accuracy, precision and completeness (hereafter precision and completeness will usually be lumped into the related term, accuracy), and each of these become more difficult to achieve as goals become increasingly complex and therefore difficult to represent or understand (

Dolan and Dayan, 2013) (

Figure 1B). Moreover, although efficiency and accuracy are expected to correlate, they could also exhibit allocation tradeoffs, such that, for example, over-efficiency leads to error-prone and therefore inaccurate or partial resolutions. Here, we simplify by assuming these, together with precision, correlate, and constitute a measure of achievement (or payoff, fitness).

Based on the above observations, a sequence in the evolutionary emergence of intelligence

must begin with the capacity to resolve uncertainty (solving) and thereafter possibly expand into prediction of the relevance of alternative informational sets or sequences (planning). As discussed below, this is the basis for evolutionary reasoning to contribute to explaining differences in intelligence capacities between individual systems (trait variation, environment) and across system types (phylogeny), with natural physical systems (e.g., crystal formation) at the base and a hypothetical hierarchy in complexity as one goes from artificial (and subdivisions) to biological (and subdivisions) to human. I stress that partitioning systems in intelligence classes does not signify differences in performance (quality, value, or superiority). Rather, it relates to how these different systems adapt to their particular spectrum of environmental conditions and goals. Differences in the amplitude and spectrum of intelligence traits are therefore hypothesized to reflect differences in the

intelligence niche, that is environments, capacities and goals relevant to a system (e.g.,

Burkart et al., 2017,

Godfrey-Smith, 2002,

Pinker, 2010) presently or in the near future (

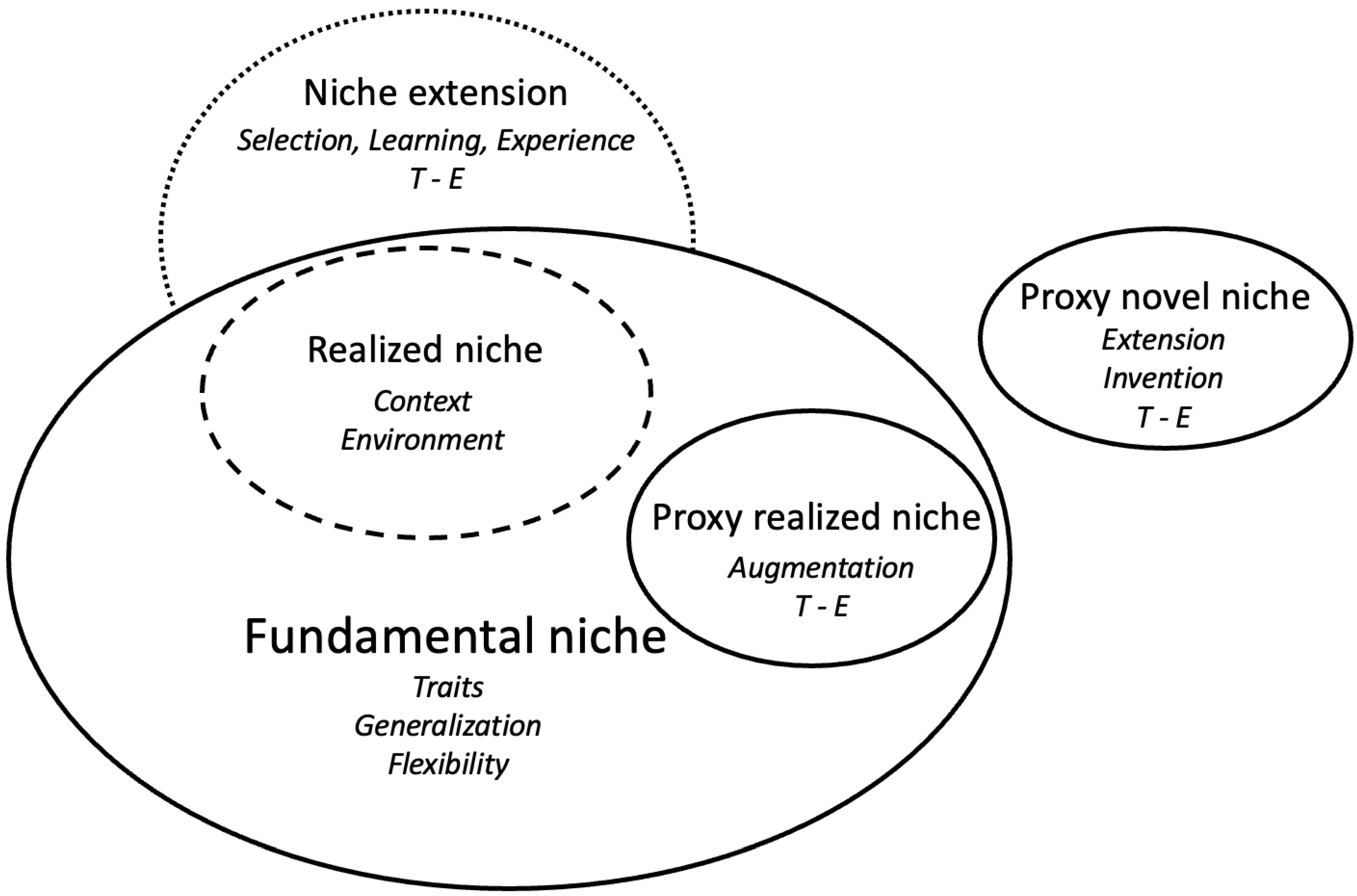

Figure 2).

Key to my idea is that selection, fitness, information, complexity, entropy, uncertainty and intelligence are interrelated. There is abundant precedent for such associations, going at least back to Shannon (

Shannon, 1948,

Shannon and Weaver, 1998), based on comparisons and analysis between subsets of these six phenomena (e.g.,

Adami, 2023,

Rivoire and Leibler, 2011,

Gottfredson, 1997,

Donaldson-Matasci et al., 2010,

Frank, 2012). One of my objectives is to begin to explore these interrelations, recognizing that an ecological perspective could yield important and general insights. Thus, intelligence crosses ecological scales, for example, from within systems to interactions between systems and their environment (sensing, probing, interacting, experimenting), to (social) interactions in populations of systems. Scales and the orthogonal concept of levels (or layers) within systems introduce notions of complexity, that is, the depth and heterogeneities in the structure and function of the system (

Lloyd and Pagels, 1988,

Collier and Hooker, 1999). I hypothesize that the complexification of intelligence across systems is a manifestation of innovations in capacities and more singular

transitions in intelligence, that is, from a baseline of the resolution of local uncertainty (all systems), to sequential relations among local uncertainties (most biological systems to humans), to the ability to integrate two or more local uncertainties so as to more accurately and efficiently achieve goals (higher biological cognitive systems to humans) and finally general intelligence in humans. Though largely unexplored (but see

Stanley and Miikkulainen, 2004,

Baluška and Levin, 2016,

Frank et al., 2022,

Fields and Levin, 2022), I suggest that the transitions from baseline uncertainty resolution to general intelligence reflect increased solving ability and for more complex goals, hierarchical planning, both requiring augmented existing and novel abilities (see

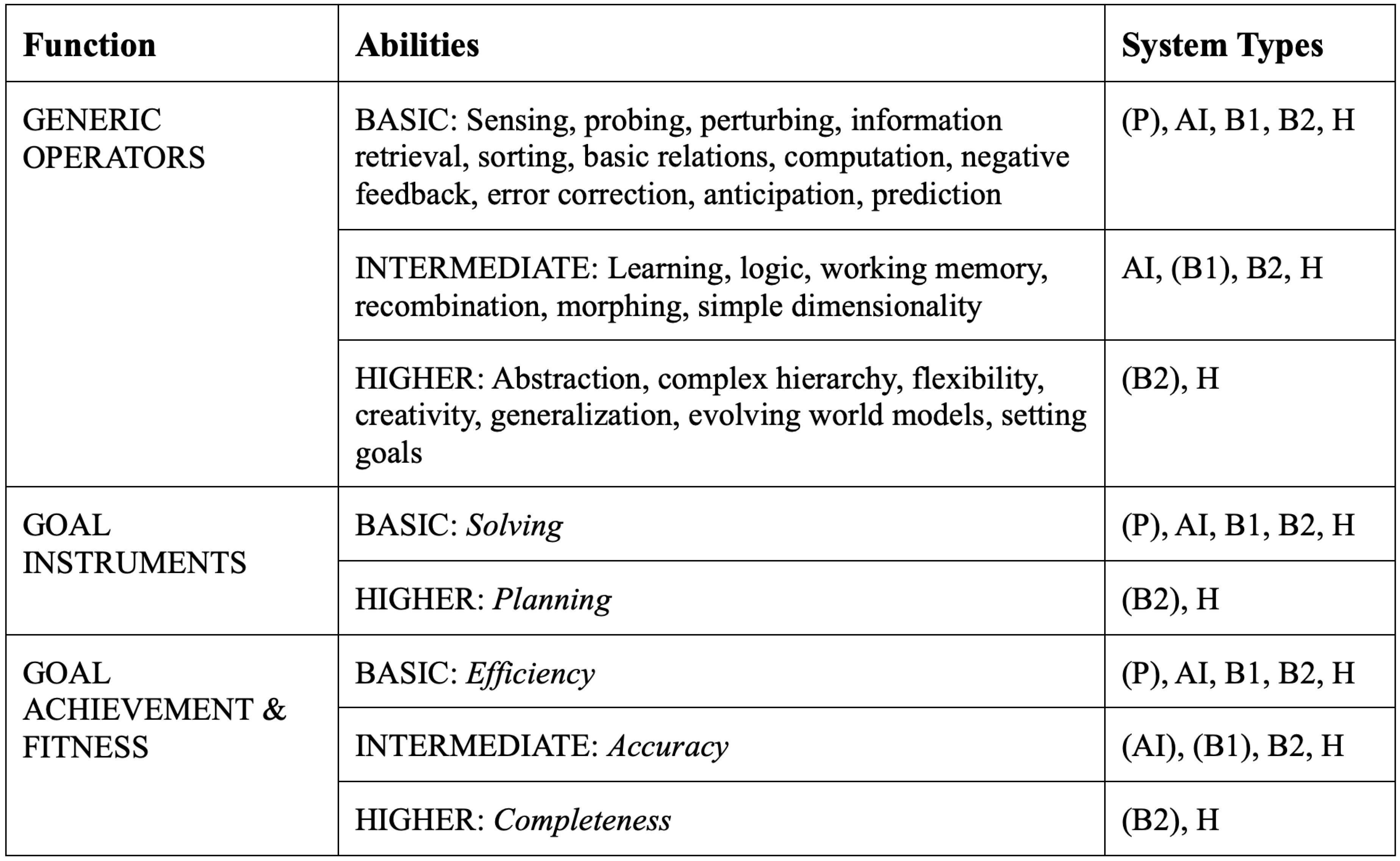

Table 1 for preliminary classifications).

That complexity and intelligence can be intertwined has important implications for explaining structure and function within and across systems. Insofar as systems evolve, so too do the intelligence traits employed to penetrate complexity (e.g., define and realize goals; (

De Martino and Cortese, 2023) and contribute to changes in complexity (e.g., generate novel information, structures, transitions in scales and levels), which, in turn, can require greater and different forms of intelligence in order to resolve, and so on, possibly as an auto-catalytic process (

Kauffman et al., 2007). Goal relevancy includes those actions affecting fitness (i.e., growth, survival and reproduction when faced with challenging environments, including limited resources, competitors and predators), well-being (e.g., sports, leisure, art in humans), or actions with no apparent objective at all. The goal can be within the gamut of previous experiences or an extension thereof, or be novel but realizable at least in part, despite its difficulty. To the extent that the universe of relevant, feasible goals is diverse, one expectation is that intelligence traits will not only evolve to improve fitness in existing niches, but also extend into new intelligence niches, which may or may not be more complex than existing ones (

Figure 2) (for ecological niche concepts see

Chase and Leibold, 2003).

In sum, we need a theoretical framework that recognizes the close interconnections between uncertainty, information, complexity and intelligence, and is built on ecological and evolutionary principles.

1.2. A Basic Framework

The above discussion equates intelligence with a system (or a collection of systems) engaging in a reactive challenge or a proactive opportunity, and doing one or more of sensing, extracting, interpreting, manipulating, transforming and assembling information, and rendering it in a different, possibly more complex form. (Note that below I distinguish reaction from active engagement, but more realistically the latter will include the former). An example of a complex finality is the structure of an architecturally novel, high-level functioning business center. An example of a simple goal outcome is to win, lose or draw in the game of chess. Both examples may have complex paths (requiring intelligence) despite differences in the information contained in their finalities.

Sensing, extracting, interpreting, experimenting, transforming and assembling – characteristic of biology and to a certain extent AI – employ logical associations (

Albus, 1991,

LeCun, 2022,

Goyal and Bengio, 2022,

LeCun et al., 2015) and as such, abstractly, they differentiate, correlate and integrate existing and new goal-useful information. This involves amassing and deconstructing complex and possibly disjoint ensembles, identifying their interrelationships, and reconstructing the ensembles and existing knowledge as goal-related information, so as to infer or deduce broader implications leading to a resolution (

Goyal and Bengio, 2022,

Adami, 2023,

Botvinick and Toussaint, 2012). Thus, metaphorically, intelligence is an operator or a

calculus of information.

The above coarse-grain perspective emerges from more microscopic, fine-grained levels with what are often viewed as traits associated with humans such as reasoning, abstraction, generalization and imagination. Unfortunately, there is no (single) objective way to represent these and other more microscopic features of intelligence and their interrelationships (e.g.,

Albus, 1991,

Adami, 2023,

LeCun et al., 2015,

Rosen, 1958,

Maturana, 1980,

McCarthy et al., 2006,

Gershman et al., 2015,

Scholkopf et al., 2021). Thus, to be manageable and useful, it is my view that a theoretical framework of intelligence needs to begin at higher-level macroscopic concepts. To accomplish this, I start by developing a series of increasingly complete conceptual definitions. Consider the following keyword sequence for intelligence:

Despite overlap between these descriptors,

A makes plain the temporal and dynamic nature of intelligence. The process requires integrating previous history, acquired information in the forms of priors and experience, including knowledge and skills, and the use of current data and information in an internal world model towards a future goal or in reaction to a challenge, producing a result. Key is the manipulation and application of raw data and more constructed information towards an objective. In what follows, I will focus on intentional goals, but the theoretical development is general to both reaction and intention. Furthermore, the quantitative definitions (“indicators” or “indices”) below are simple macroscopic representations of complex processes and behaviors, but nevertheless in being based on the general notions of information and entropy, can apply broadly across systems (e.g., in biology (

Adami, 2024).

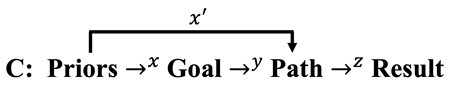

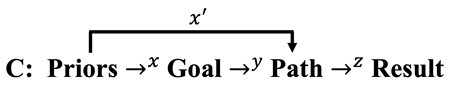

To integrate the above elements into a general schema we first focus on the core processing module:

System

B is simple but general. If

B is a mere reporter, then it simply uses input to find output from an existing list, or Goal → Result. If a system has more elaborate capacities, then

may be characterized by signal processing, simulation, interpretation and eventual reformulation of the problem, followed by engagement in the decided method of resolution to

, including prediction and checking for errors (

LeCun et al., 2015). This more elaborate system then decides whether to go back to

and possibly re-examine what previously appeared to be useless data, or continue on and render a result. Ultimately understanding intelligence in

B requires we have representations of its inner workings (

Collier and Hooker, 1999,

Rosen, 1986,

Cronin et al., 2006).

We can further extend B to how information is accessed, processed and used towards a goal:

The main addition is that both

and

are conditional on priors, knowledge and skills. In humans, necessities such as food and shelter impose on lower-level priors (e.g., reactions to hunger and fear; notions of causality), whereas opportunities such as higher education and economic mobility require high-level priors (e.g., causal understanding, associative learning, goal directedness) (

Chollet, 2019)). The contingencies of goals and paths on information in the forms of priors, knowledge and skills highlight the temporal process nature of intelligence that is central to the framework proposed here.

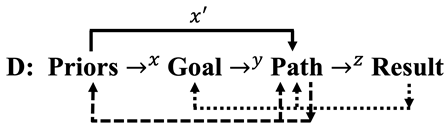

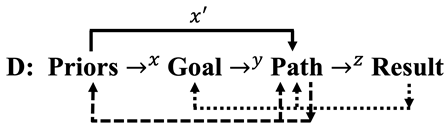

Finally, we can modify C to account for error-checking and prediction, that is, feedbacks and feedforwards in how information is marshaled towards goal resolution:

The dotted lines indicate how results can reinforce future paths for current goals and introduce novel set-points for future goals. Similarly, the dashed lines indicate how path experimentation (model flexibility, recombination of concepts) could influence future paths and knowledge and skills. Even if more realistic than the sequences in

A-

C, these additions are still massive oversimplifications of the sophistication of informational dynamics in artificial and particularly in biological systems. Thus, for humans, these feedbacks and feedforwards could reflect the ability to reflect on past actions and correct mistakes.

D simply makes the point that intelligence is a dynamic process with loops in the form of negative feedbacks (comparisons) and feedforwards enabling purpose and goals (

Rosen, 2012,

Wiener, 1948). Information change is a central feature of TIS and as developed below, important in describing differences in information processing among system types, including natural physical, biological, and artificial.

The above descriptions of temporal sequences say little about system features associated with goal definition and those promoting goal attainment. Despite considerable discussion (e.g.,

Albus, 1991,

Goyal and Bengio, 2022,

Cattell, 1963,

Spearman, 1904,

Chollet, 2019,

Adami, 2023,

LeCun et al., 2015,

Gershman et al., 2015,

Brooks, 1991,

Kabadayi et al., 2018,

Wang, 2019) there is no consensus on a process-based theory of intelligence, neither for biological divisions (

Levin, 2022,

Baluška and Levin, 2016,

Lyon, 2020), nor for artificial systems (

Goertzel, 1993,

Adams et al., 2012,

Friston et al., 2024,

Roli et al., 2022). This state of affairs stems in part from the lack of agreed first principles for candidate features and the ill-defined conceptual overlap among various traits influencing intelligence. A way forward is a more inclusive framework based on the resolution of information. I recognize that this still falls short of a readily testable framework and rather intend the developments below to stimulate discussion of next steps and refinements.

The TIS framework developed in the next section partitions a system into two main constructs – challenges and abilities. Challenges include (1) how agent capacities compare to goal complexity (difficulty) or novelty (surprisal, difficulty) (

Sternberg, 1984) and (2) the capacity to arbitrate the use of stored information (exploitation) versus acquiring additional information (exploration) (

Cohen et al., 2007,

Mehlhorn et al., 2015,

Del Giudice and Crespi, 2018). And to my knowledge not previously discussed, a related tradeoff in humans is between (3) the employment of stored information (crystallized intelligence) versus higher reasoning abilities (fluid intelligence). The basis for this latter tradeoff is costs and constraints in experiencing, learning, and efficiently and accurately storing and retrieving information in the form of knowledge and skills, either alone, together with, or replaced to some degree by fluid abilities such as reasoning and creativity.

Challenges are addressed based on abilities. Previous frameworks of intelligence in humans, biology and AI have emphasized hierarchical structure in abilities (e.g.,

LeCun, 2022,

Spearman, 1904,

Carroll, 1993,

Conrad, 1996,

Deary, 2014,

Chollet, 2019), but the framework presented here is unique in distinguishing generic abilities from those actually applied to goals and their occurrence in different system types (

Table 1). Generic abilities and goal abilities are each partitioned into multiple levels based on their hypothetical order in evolutionary appearance, that is, the necessary establishment of mechanisms on a given level for the emergence of more complex mechanisms at a “higher” level (

Figure 3). For instance, planning manageable sequences of subgoals serves little purpose unless there are existing capacities to solve component tasks along a sequence. Moreover, solving needs references (memory, objects or constructs, error correction) and at higher levels the ability to arbitrate or predict these references and self-assess. An expectation from evolutionary theory (

Maynard Smith, 1978) is that costly improvements to higher-level planning lag behind more essential abilities associated with baseline solving. Thus, the hierarchical categorizations in

Table 1 are not clear-cut (and solving and planning are discussed in more detail in the next sections). Identifying component levels for various abilities presents a considerable challenge, both because of their subjective nature and since abilities may articulate at more than one level and interact with environmental variables (e.g., affordances,

Pezzulo and Cisek, 2016,

Roli et al., 2022).

Table 1 also lists system types commonly associated with different abilities. Many exceptions exist, notably in biology, where for example, certain avian lineages and cephalopods match or even surpass some mammals in generic and goal-associated abilities (

Emery and Clayton, 2004,

Edelman and Seth, 2009,

Amodio et al., 2019). There are, nevertheless, regularities that characterize intelligence in the major system classes presented here. Perhaps the most controversial of these are non-living, physical and chemical systems. In such systems, events depend on the actions and influences of laws of physics and interactions with environments (

Anderson, 1972,

Frenkel, 2015). Natural physical systems do not have “abilities” as such, yet they can reactively assemble and disassemble information based, in part, on the laws of thermodynamics (

Kalantar-Zadeh et al., 2024). Thus, at least abstractly, natural physical systems are “able to react”, resulting in informational change.

2. A Framework for a Theory of Intelligences

Theoretical developments to characterize intelligence are found among many disciplines and diverse systems (e.g.,

Albus, 1991,

Sternberg, 1984,

Goertzel, 1993,

Wang, 2009,

Peraza-Vázquez et al., 2021). Explicit frameworks and measures in AI have described processes such as reinforcement learning based on rewards (

Legg and Hutter, 2006), temporal sequences from access to priors and accumulating knowledge and skills through to learning (

Chollet, 2019), prediction error-checking and correction in achieving goals (

LeCun, 2022,

LeCun et al., 2015), and reasoning via planning (

Hao et al., 2023). These and other recent advances have largely centered on artificial systems, both because of the rapid growth in AI and since these systems are more tractable than biological intelligence (and human intelligence in particular). The descriptive indices presented below, being based on the common currency of information, are sufficiently flexible to apply to a range of biological or AI systems and contexts. The indices accommodate possibilities that goals can be attained with little or no insight, or that intellectual capacities do not ensure goal realization (e.g.,

Mashburn et al., 2023). The former implies either outside help, luck, goal simplicity, or reapplying knowledge to the same problems.

The above developments set the stage for a framework incorporating temporal, multi-level and multi-scale factors, focusing on how intelligence

addresses uncertainty and complexity. I hypothesize that intelligence manifests across the different system types in

Table 1 as goal-related information gain relative to extractable information available. I stress that my approach is to describe the outcome of events and not the underlying processes (i.e., abilities in

Table 1) driving these events.

Building on the discussion in the previous section, local

solving is addressing an arbitrarily small (manageable or imposed) unit of what might be a global objective, an example being single moves in the game of chess. As a goal becomes increasingly complex, multiple abilities will be marshaled in achieving solving, but solving alone may be insufficient to address higher-dimension goals and particularly those where uncertainties themselves unpredictably change (e.g., an opponent in chess makes an unexpected move). To this, uncertainty in achieving high-dimensional goals is reduced through

planning. Planning – which appears to be a uniquely highly developed characteristic of humans (

Albus, 1991,

Sternberg, 1984), but see (

Roth and Dicke, 2005,

Roli et al., 2022,

Smith et al., 2014) – can involve (as does solving), one or more of the non-mutually exclusive capacities of computation, abstract reasoning, anticipation, prediction, mechanistic/causal understanding, and creativity (

Table 1). In the chess example, a current move decision is contingent on planning for future moves. Planning contributes to reducing uncertainty and is central to accurate and possibly efficient goal attainment. Efficient and accurate trajectories to goals become more difficult to attain as alternative paths become more numerous, more complex, and require more (limited) energy. In the extreme, non-planned, stepwise, myopic strategies cannot resolve inherent uncertainty in future paths (

Kauffman, 2000). As such, the agent assesses the current state of the resolution and the environment and dynamically adapts its future choices (

Rosen, 2012,

1991), thereby reducing surprises and achieving more efficient and/or valuable resolutions (

Maier et al., 2016,

Walker et al., 2013). Planning can also reduce goal difficulty by experimentation (e.g., evaluation of counterfactuals) or engineering the environment, or changing goals themselves on-route, meaning, for example, that satisficing as opposed to goal attainment may emerge as the most intelligent outcome (

Simon, 1956,

Hayes-Roth and Collinot, 1994,

Bossaerts and Murawski, 2017). Moreover, although not explicitly modeled below, depending on the system, environment and goal, solving and planning may each involve some combination of deterministic approaches (e.g., algorithms, computation) and probabilistic affordances (e.g., invention, short-cuts, creativity) (

Pezzulo and Cisek, 2016), the latter of which can “rig the jury” (

Roli et al., 2022) and to an observer, make hard problems look easy. Finally and importantly, solving and planning are not independent of one another. For example, in reinforcement learning, the system state is influenced by local (solving) value, and this in turn influences possible changes to policy (planning) so as to maximize future return (

Sutton and Barto, 2020).

In the intelligence definitions below, I consider a single agent or system addressing uncertainty, either in reaction to a single challenge or to intentionally achieve a single goal. The definitions presented characterize extracted information change, inspired from macroscopic indicators of intelligence in artificial systems (

Chollet, 2019). Although not explicit, the indicators could permit en-route change (possibly via self-assessment) via more microscopic abilities, resulting in error-correction, altered planning or even model modification. Indeed, one interesting line for future inquiry is to know to what extent goal resolutions involve self-correction via internalized meta-cognitive processes (e.g., negative feedback) and/or external perturbations to escape rigid heuristics (e.g., use of affordances).

The indices presented below are based on units (e.g., bits) of information, but given their underlying complexity, will not be practical to estimate, particularly for biological systems. They are therefore intended as a start to formalize concepts for a Theory of Intelligences. The indicators define an informational landscape as a set of discrete, possibly dynamically changing, subgoals. Metaphorically, the agent embarks in the landscape, addressing individual subgoals (“nodes”), where the nodes are random variables in an uncertain state and their choices and information resolution reflect underlying intelligence abilities. The nodes sequentially discretize what is in reality a multi-layered (and for some systems, continuous) process. Moreover, the indicators are not explicit in how or why an agent chooses a specific set or sequence of subgoals. That is, alternatives to choices are not recorded and there is no mechanistic insight for choices beyond saying that events can be functions of past and future prospective choices, intrinsic abilities, current contexts and environmental conditions. The terms represent what an agent did and could have done, and thus the indicators are considerable oversimplifications of artificial and especially biological systems. Nevertheless as described below, they reveal some of the important interrelationships and challenges that could contribute to a predictive theory. As above, even if information can be quantified (e.g., test questions with minimal, efficient, logical paths to partial or complete solutions), the indices presented do not explicitly include abilities (

Table 1), contingencies (failure, stopping conditions) and dynamics (learning, changing policy or strategy). Moreover, if the agent dies in attempting to accomplish the goal, then although components of intelligence may be tallied for the nodes visited, the ultimate transmission of intelligence traits to others and to future generations could be curtailed.

Below, solving and planning are each represented by a single key variable. For solving it is Un, the useful information acquired at subgoal (node) n towards the ultimate goal or result, whereas for planning it is An, the accuracy and efficiency of the broader scale informational choices (i.e., strategy) to the ultimate goal itself. Nodes (units) form a sequence of subgoals that increasingly approach the ultimate goal if the system better solves and, for a complex goal, plans the sequence. Intelligence minimally requires that goal-relevant information is gained (i.e., uncertainty reduction) at one or more nodes. Monotonic gains in information do not ensure goal attainment and goals can be attained even if information is nil or lost at certain nodes.

2.1. Solving

We assume a goal can be represented by one or more alternative paths, each being a series of nodes (subgoals), and each node composed of potential information relative to the result or ultimate objective. The agent traces a single path and employs unspecified capacities and data to achieve some level of uncertainty resolution, measured as information useful for attaining a goal. The total information at given node n is based on information acquired from previous engaged node(s) and resolution of entropy (i.e., potential information) in the current node. The useful entropy in the current node is conditional on past information (e.g., the current potential information is redundant). The reverse is also possible: the acquired information at a past node can be conditional on future node events (e.g., the new information is superior and supplants existing information). The index below does not explicitly account for these dynamics, but rather tallies the total information in the path once the agent has stopped at n=N.

The solving component of intelligence reflects accuracy, that is the gain in information useful towards goal y:

where

and

are, respectively, the realized gain in useful (semantic) information at node

n for goal

y, and the amount of entropy of the random variable available at node

n.

is the total fraction of useful information towards the goal path contained in

. Thus, a goal-rich node will have some combination of high

and high

. Note that extraction of information from a source requires ability to differentiate goal-useful from goal-useless information and noise. Note too that

>0 does not ensure the system will succeed in extracting any useful information from the sub-goal.

is a function of agent abilities given environmental conditions (the commonsense notion of intelligence; hereafter the function notation

is dropped). Disruptive noise and inhospitable environments could, in principle, result in information loss (time course ii in

Figure 1B). Importantly, given possible redundancy or contingency in both useful (numerator) and potential (denominator) information across nodes, goal-related information gained at node

n will be a dynamic function of information gained at previous nodes

n-1... Note whereas

will be a complex function, the set or sequence of

is given (i.e., there is no explicit planning; this will be relaxed below). By definition

≥

and therefore

approaches 1 as

→

for all

n.

is normalized by the number of subgoals

N, which does not explicitly account for solving efficiency. Solving efficiency could be incorporated as a first approximation by dividing

by the energy invested or time elapsed on each subgoal

n.

We can modify (1a) to include the contribution of information at node n useful to goal completion, with the condition :

Thus,

as both information gain is maximal at each node (

/

→1)

and the sum of information gained at all nodes is accurate and complete (

→1). Goals can be attained through some combination of solving

, insight in nodes selected (

and

), and number of nodes visited

N. Importantly,

does not necessarily assume long-range planning (but can, see

Section 2.4), but rather reflects the quality of adjacent node choice (the lower limit of planning).

Note that is an indicator of that part of total goal complexity realized by the agent. can also be interpreted as part of a stopping condition, either an arbitrary goal-accuracy threshold (>) or a margin beyond or below a threshold (-). An example of a threshold is the game of chess where each move tends to reduce alternative games towards the ultimate goal of victory, but a brilliant move or sequence of moves does not necessarily result in victory. Examples of margins are profits in investments or points in sporting events, where there is both a victory threshold (gain vs loss, winning vs losing) and quantity beyond the threshold (profit or winning margin). We do not distinguish thresholds from net performance below, but rather highlight that goal resolution could involve one or both.

2.2. Planning

Solving alone can, but does not necessarily ensure goal attainment (

Firestone, 2020). This is because, for example, a system may either (1) correctly execute most of a series of computations, algorithmic functions, or inferences but introduce an error that results in a partial or substandard resolution or no resolution at all, or (2) choose nodes that, taken together, only contain a subset of the information necessary to accurately attain the goal. Either or both can be ameliorated through planning. Planning can involve the set of nodes and/or their sequential order. For some systems, planning can also be dynamically updated when faced with current goal-attainment contingencies. This might involve either adapting the planning strategy and/or modifying foundational internal system models.

We begin by defining planning accuracy and completeness on goal y as the potential goal-related information contained in the actual choices of path nodes relative to the nodal set comprising the maximal potential goal-related information . Maximal information does not ensure goal attainment, that is, for example, a problem may not be solvable based on available information, even if extraction is perfect. Moreover, complex goals may have more than one informational path to their resolution (possibly with different efficiencies). We do not represent such complex landscapes here and rather highlight this realism for future work.

We assume that planning can occur at multiple levels, here for illustration we assume two levels, where nodes at the lower level depend on strategic choices at the higher level. Below, the external summations h=1 to H and =1 to are the actual and maximal upper-level strategic sets, respectively. Similarly, n=1 to and =1 to are lower-level nodal sets. The paths actually taken in h and n space are therefore a consequence of planning. For example, in the game of chess, play epochs (H, ) may be partitioned into opening, middle and end games strategies. Evidently, the lower level (N, ) moves are contingent on opposing player moves and strategy, and higher level strategy may change based on contingencies as well.

where

is maximal potential goal information under optimal planning, and noting that

is now a function of unspecified planning abilities (

notation dropped below). Index (2a) relates the point that – even if focusing on the actual choices only (the numerator) – planning can occur on multiple levels, each of which manifests as both internal interactions and interactions with other levels. Moreover, current choices could be influenced by past and future prospective states, and the utility of past states could change with current choices. Therefore, for example, the numerator of (2a) could be a function of potential information (

), the fraction that is useful (

), and/or actual acquired information (

) from the past (1..

h-1; 1..

n-1) and/or predicted in the future (

h+1 ...;

n+1 ...). Thus, although not explicit in the indicators, solving and planning need not be independent of one another.

Index (2a) can be simplified by assuming that planning occurs at the lower level n,:

Note that one or more paths might result in having access to maximal potential goal information

.

A final index for goal accuracy

quantifies

solving based on no planning (1b), relative to that based on planning if the agent were to follow the maximal potential goal information path.

where

.

2.3. Intelligences

Any multifactorial definition of intelligence is frustrated by the arbitrariness of component weighting. In this respect, a central ambiguity is the relative importances of solving, planning, and goal attainment (

Kryven et al., 2021). Clearly, each node choice depends to some extent those preceding it and each choice may also depend on predictions of those environmental states not having yet occurred. For illustration of the basic issue, consider two different strategies available to an entity – an efficient one and an inefficient one – each yielding an answer to the same problem. There are two outcomes for each strategy: inefficient strategy, wrong answer (0,0); efficient strategy, but wrong answer (1,0); efficient, correct (1,1); And yes, especially for multiple choice questions, inefficient, correct (0,1). Undoubtedly, (1,1) and (0,0) are the maximal and minimal scores respectively. But what about (1,0)’s rank compared to (0,1)? If a multiple-choice test, then one gets full points for what may be a random guess and (0,1). If the path taken is judged much more important than the answer, then an interrogator would be more impressed by (1,0) than (0,1).

In addition to possible ambiguities between abilities and performance (

Firestone, 2020), key abilities themselves may or may not be correlated. Specifically,

and

are indicators of two complementary forms of intelligence in those systems employing both solving and planning. Although they can each serve as stand-alone assessments, they are ultimately interrelated by

, the entropy, or potential goal-useful information content at each node visited. Correlations between

and

are expected to increase with either few subgoals to accurate resolution, or many simple subgoals. See

Section 2.4 for how (1b) and (2b) are linked should planning occur.

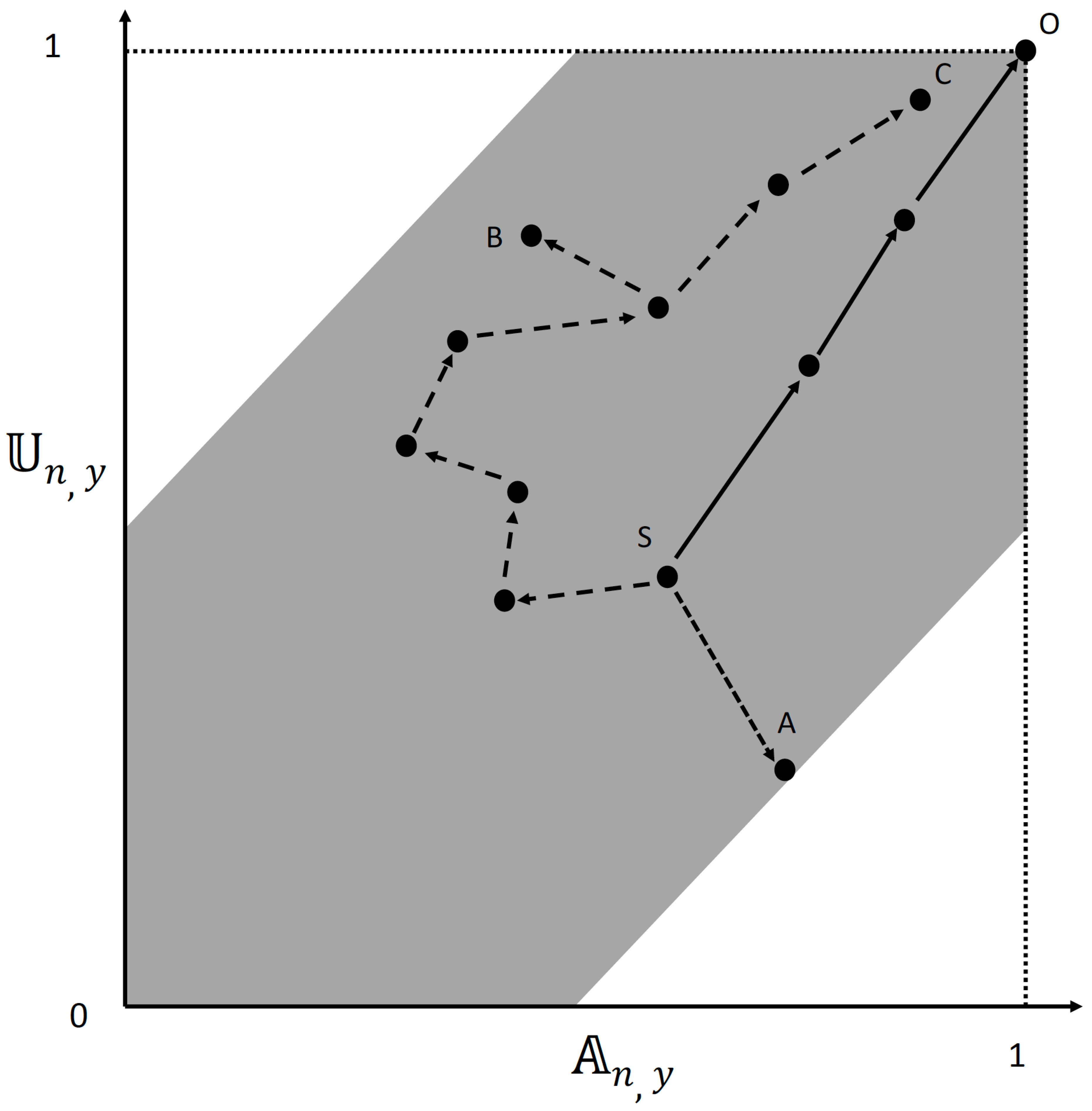

Figure 4 shows how an agent’s trajectory through information space hypothetically plots onto a space of achievements. Different nodal paths can produce a similar final outcome (S-C and S-O), and very similar paths can lead to different outcomes (S-B and S-C). Underscoring the importance to intelligence of solving and planning flexibility, one or the other of

and

might increase, decrease or remain unchanged as the agent proceeds through successive nodes. This relates to the expectation that the most efficient and accurate path (e.g., gradient decent in unconstrained systems) to goal completion will involve the allocation of solving and planning abilities (

cf trajectories i or ii vs iii in

Figure 1A).

Figure 4 also illustrates that solving and planning need not concord (e.g., path S-B in

Figure 4). Nevertheless, given likely correlations among intelligence components, we predict that there will be a feasible parameter space for a given agent’s abilities (shaded area,

Figure 4). We did not explicitly represent these co-dependencies in the indicators of intelligence and rather recognize that goal complexity will tend to lower overlaps between abilities to solve and plan.

2.4. Composite Indicators

The above discussions and expressions (1a-b) and (2a-c) provide a basis for a framework of intelligences. They characterize two central abilities, solving and planning, but as related above, overall goal performance does not necessarily require both. I propose a general composite index for intelligence based on the assumption that solving is necessary and planning only influences intelligence insofar as it interacts with solving. Noting that when the agent plans, and are equivalent at any node n, and the former can be substituted for the latter in (1b). We thus have a simple expression for the value of intelligence of an agent with capacities x addressing goal y, where capacities match goals as

where for notational simplicity =. Substituting from (1b) and (2b) we have

which can be simplified to

Intelligence is defined by (3c) as the goal-useful information actually gained relative to total potential information under optimal planning. It is interesting that the defining term for planning () drops out of this expression. Rather, planning in expression (3c) is implicitly contained in the choice of nodes n associated with the solving results in the numerator.

Although is relative to potential information, an additional step is necessary to address the issue of subjectivity in indicators of intelligence. That is, the resolution of a given goal may be effortless for one system and effortful for another. Moreover, the resolution of a goal may appear simple to one observer and hard to another. These contrasts – among intelligence as attaining goals regardless of difficulty, intelligence as overcoming difficult goals, or intelligence as the perception by others – are central to the issues of whether intelligence is a property of system performance, performance relative to goal difficulty, and/or the extent to which it is agent- or goal-intrinsic or observer-dependent.

A simple way to incorporate ability relative to challenge is to relate intelligence to goal difficulty. Difficulty can be defined and quantified in many ways (e.g.,

Beckmann et al., 2017,

Pelánek et al., 2022,

Benedetto et al., 2023), and we employ the idea that difficulty is intrinsic goal complexity relative to a baseline, for example the abilities of a specific agent to resolve that complexity (see discussion in

Chollet, 2019). A hard problem for a given agent need not be a novel or surprising problem for that agent; that is, even if the agent has the familiarity and capacities to solve the problem, considerable work may be required to solve it because of its intrinsic complexity (e.g., a high dimensional Sudoku puzzle).

Intelligence defined as achievement relative to difficulty can be quantified by first proposing an expression for difficulty based on concepts developed above

is a measure of the intrinsic complexity of goal

y, that is, the minimum amount of potential information required to achieve (or describe) the goal. Complexity could, alternatively, be represented as

, that is, the subgoals available to or actually addressed by the agent, or as

the realized complexity resolved by the agent.

Moreover, the quantity

> 0 is the expected ability of the agent with expertise

x to achieve goals in class

y. (Note that depending on the context,

can also be an estimate of random noise or of a benchmark). All else being equal,

will decrease as

x and

y diverge (i.e., greater novelty). Because actual experience on a goal reduces future surprisal and therefore increases

on similar goals,

will be challenging to estimate, necessitating for example a subjective, interrogator-based index (

Rosen, 1986), or for difficulty averaged over a population, an index based on benchmarked ability (

Bodria et al., 2021,

Hernández-Orallo, 2017).

Whereas from (3a-b) is an indicator of intelligence based on actual solving and planning, a complementary index based on the notion of difficulty is

High intelligence implies a high performance on a difficult goal

, whereas

signals lower than expected performance on an easy goal.

Index (3e) is both general and powerful. and are all composed of terms in units of information. By simple inversion of difficulty (3d) we have an expression for the expectation of intelligence for a given level of complexity . The mean and variance in over many similar tasks is a measure of positive impacts of training (e.g., performance of machine learning generative models in AI) or experience (biology), or negative impacts of environmental variation or noise. Moreover, could be taken at different points in system development (e.g., ChatGPT3 vs GPT4), different individual system ages (GPT4 through time), in different contexts, capacity of different observers, etc.

2.5. History, Transmission and Evolution

The above developments characterize intelligence as the resolution of subgoals – and possibly the resolution of a larger strategy – culminating in a reactive result or a purposeful objective. The indicators focus on information changes in a single system addressing a single challenge or goal and as such are unable to capture larger scale, variation or changes in intelligence, notably associated with experiential and social variables, that is, the history of the individual system and transmission of knowledge or skills, and changes stemming from the longer term, that is, population changes due to trait evolution.

2.5.1. History

Excepting in humans and select B2 species (

Table 1), we know little about how intelligence capacities evolve during the lifetime of an individual system. In B2 and human systems, and simplifying considerably, the evolution of abilities is associated with positive development and experience (learning) leading to new knowledge and skills, and generalization and refinement of the world model (in humans). Artificial systems currently lack the sophisticated development characteristics of biological systems, although large language models such as ChatGPT progressively “learn”. In contrast, natural physical systems, be they tending to order or disorder, are reactive and the dissipation associated with increased disorder is analogous in some ways to biological aging.

Capacities to react to challenges or address goals change with system history (

Hendriks-Jansen, 1996), and agents will experience many, possibly different difficulties and payoffs during their existence. Historical changes in intelligence address the fact that challenges may change through a lifetime and systems as well as populations adjust existing and introduce new capacities and strategies based on past, current and predicted future encounters. Capacities in most biological systems cannot be exhaustively programmed at system inception, nor can a system make a perfect map of all lived experiences. Thus, at least in some biological systems, increases in generalization abilities are expected throughout a life. For example, intelligence resources in humans are characterized by the growth of crystallized intelligence (knowledge, skills) into adulthood (

Horn and Cattell, 1967,

Nisbett et al., 2012) and gains in general intelligence faculties (

Chai et al., 2017) through childhood and adolescence. As individuals age, they may encounter fewer never-before seen problems and are less able to maintain working memory and processing speeds (

Salthouse, 2012). This suggests a strategy sequence in humans with a relative shift from dependence on others (parents, social) and experimentation, to crystallized (knowledge, skills) intelligence in youth, to fluid (thinking, creativity, flexibility) intelligence in youth and mid-life, and finally more emphasis on crystallized intelligence (possibly with more dependence on proxies, see below) into older ages. In other words, even if more nuanced (

Hartshorne and Germine, 2015,

Tucker-Drob et al., 2019), evidence points to the continual accumulation of reusable and modifiable motifs, knowledge and skills in youth enabling the ascension of novel reasoning in early and mid-life, the latter gradually being dominated by memory/recall into later life.

2.5.2. Transmission

Transmission can be an important facilitator of capacities and come from diverse sources. Examples include horizontal code transfer (e.g.,

Hall et al., 2017), social interactions (e.g.,

Krause et al., 2010) and technology (e.g.,

Biro et al., 2013). Social interactions are pervasive as transmitters of knowledge and skills and range from interactions at different scales within and between systems (

McMillen and Levin, 2024), to a group where individuals exchange information and act collectively towards a goal (e.g., certain microbial or animal aggregations;

Couzin, 2009)), to a division of labor in intelligence where different functions in goal attainment are distributed among individual sub-units (e.g., social insects,

Pacala et al., 1996, human firms,

Tirole, 2011). The intelligence substrates provided by these and other sources could complement, substitute, enhance or extend an autonomous individual’s own facilities (

Lee et al., 2023). Thus, in some sense, capacities fostering intelligence are transmissible. For example, in human social learning, resolving tasks or goals is the raw material for others to observe, record and emulate, thereby contributing to the diffusion and cumulative evolution of knowledge (

Roli et al., 2022,

Migliano and Vinicius, 2022,

Henrich and Muthukrishna, 2023). In embodying knowledge, skills and their transmission, culture and society are at the foundation of intelligence in humans and many other animal species.

We can incorporate such “proxies” into index (3e) in a simple way by assuming they increase performance and reduce goal difficulty, whereby

where

i is reduction in difficulty given the action of the proxy, and the agent’s capacity is modified (increased) as per the function

. The balance of these two effects determines the net impact of proxies on intelligence as defined in (4); that is, proxies can either increase or decrease intelligence as measured in (4).

2.5.3. Evolution

Two other ways in which intelligence capacities can be transmitted are genetically or culturally (

Burkart et al., 2017). To the extent that inherited traits impinging on intelligence follow the same evolutionary principles as other phenotypic traits, one should expect that some or all of genetically influenced intelligence traits are labile and evolve.

Despite contentious discussion of heritable influences on intelligence in humans (

Gould, 1981,

Herrnstein and Murray, 1994), the more general question of the biological evolution of intelligence continues to receive dedicated attention (

Flinn et al., 2005,

Roth and Dicke, 2005,

Sterelny, 2007,

Burkart et al., 2017,

Pinker, 2010,

Wang, 2009,

Chiappe and MacDonald, 2005,

Lazer and Friedman, 2007,

Gabora and Russon, 2011). That intelligence traits present patterns consistent with evolutionary theory is evidenced by their influence on reproductive fitness (

Burkart et al., 2017) including assortative mating (

Plomin and Deary, 2015), and age-dependent (senescent) declines in fluid intelligence (

Craik and Bialystok, 2006). Nevertheless, one of the main challenges to a theory of the evolution of intelligence is identifying transmissible genetic or cultural variants that contribute to intelligence traits. Despite limited knowledge of actual gene functions that correlate with measures of intelligence (

Sabb et al., 2009,

Savage et al., 2018), a reasonable hypothesis is that intelligence is manifested not only as active engagement, but also embedded in phenotypes themselves, that is, evolution by natural selection

encodes intelligence in phenotypes at different biological levels (e.g., proteins, cells, organ systems…) and regulatory systems (e.g., homeostasis, hormesis, immune systems) (see also

Shreesha and Levin, 2023,

Adami, 2002,

Krakauer, 2011).

The development of how TIS relates to the evolution of intelligence will be investigated in a future study. As a start, we expect that the change in the mean level of intelligence trait x in a population will be proportional to the force of selection on associated task y. Simplifying this process considerably, for a quantitative trait x that positively correlates with intelligence indicators, we have

where

is the proportional contribution of task

y to mean population fitness and, from (3e),

and

are respectively mutant and mean intelligence fitness.

Information processing enters into the evolution of intelligence as the relative fitness of the modified trait (

Donaldson-Matasci et al., 2010). If task

y has minor fitness consequences (either

y is rarely encountered and/or of little fitness effect when encountered), then selection on trait

x will be low. Note that (5) can be generalized to one or more traits that impinge on one or more tasks (

Arnold, 1983). Moreover, note that intrinsic task complexity

appears in both numerator and denominator intelligence terms and hence cancels out of the expansion of index (5).

Finally, as discussed above, the indicators of intelligence developed here do not make explicit if and how goals are concluded. Rather the fitness consequences novel intelligence traits are assumed in expression (5) to be proportional to the implicit events comprising (3e). A more accurate representation of intelligence trait evolution would account for the temporal nature (accumulation) of payoffs. Thus, the payoff of a novel behavior to a bacterium could increase its geometric mean fitness, whereas accurate predictions for a human may only be concretized after a considerable time (if at all) and as such not impact long-term fitness or evolution. Future work should consider the evolutionary consequences of temporal goal dynamics.

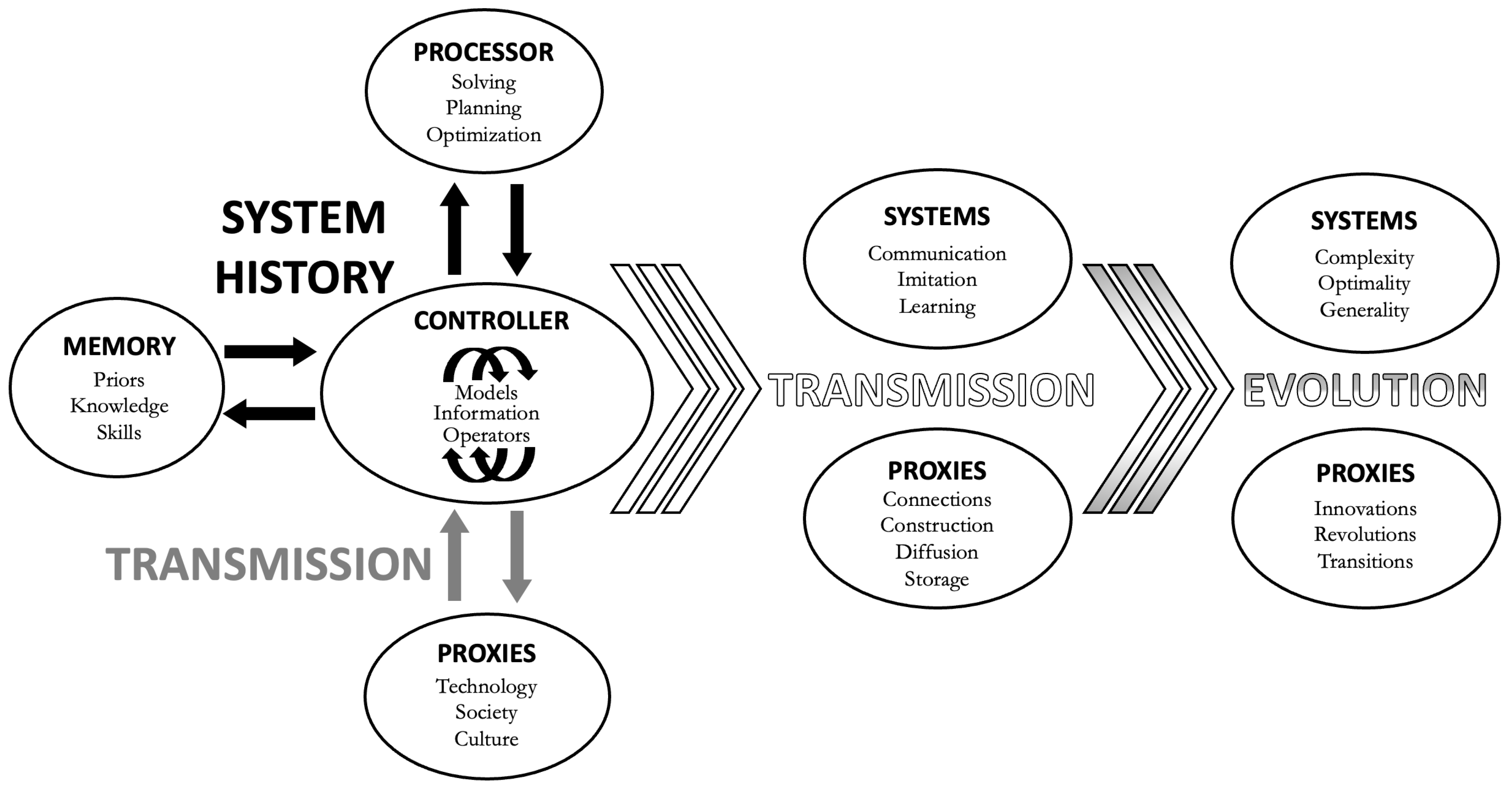

The full framework for TIS has a four-part structure (

Figure 5), now including history and transmission within an individual system’s lifetime and evolution in populations. A given system’s intelligence is thus the integration of (i) the core system (controller, processor, memory), (ii) extension to proxies (niche construction, social interactions, technologies), (iii) nascent, communicated or acquired abilities (

Table 1) and information (priors, knowledge, skills), and (iv) traits selected over evolutionary time. Indices (1-3) only (macroscopically) cover point (i). Index (4) incorporates how proxies (point (ii)) complement intrinsic system capacities, but not how they are actively used in solving and planning. (5) is a start to account for evolutionary changes in intelligence traits (point (iv)).

3. Discussion

Until relatively recently the study of intelligence focused on psychometrics in humans. With the development of AI and a greater emphasis on interdisciplinarity over the past few decades, progress has been made towards theory that spans humans and other systems, with the prospect of a general theory of intelligence based on first principles. Here, I survey recent advances towards conceptual unification of definitions of intelligence, arguing that intelligence is not a single-threshold phenomenon, but rather composed of hierarchical levels and scales and therefore applicable across all machine and biological system types and in its most primary forms, certain phenomena in physics and chemistry. Levels include capacities to perceive, sort, and recombine data, the employment of higher-level reasoning, abstraction and creativity, the application of capacities in solving and planning, and increasing accuracy and, in some contexts, efficiency. Scales enter in diverse ways, including but not limited to how intelligence becomes evolutionarily encoded in phenotypes from cells, to collective phenomena within an individual system, to the full system, and to system collectives; how abilities are acquired or lost over the life of a system (history and transmission); and abilities or capacities: the system organization, mechanisms, functions, reactive behaviors, and/or active behaviors applied to defining and achieving goals. Importantly, the indicators of intelligence presented here are inspired by, but not limited to, algorithmic systems. Thus, biological and especially human procedure is likely to be partly or completely non-algorithmic (including self-awareness), meaning that the formulae are at best approximate macroscopic indicators. The framework I propose for a Theory of Intelligences describes how these hierarchies function to extract and remodel information, either in reacting to the environment or in actively seeking goals.

3.1. Summary of TIS

The framework for a Theory of Intelligences (TIS) views intelligence as operators in a complex system, incorporating key processes, levels and scales (

Table 1,

Figure 5). TIS contrasts notably with frameworks in which intelligence is partitioned into reflex/reaction and planning (

LeCun, 2022,

Mattar and Lengyel, 2022). Specifically, in LeCun’s Mode 1, the system reacts to perception, perhaps minimally employing reasoning abilities. In Mode 2, the system can use higher reasoning abilities to plan, possibly in a hierarchical fashion. TIS differs from this framework by conceptualizing reflex/reaction as part of both solving and planning, and rather distinguishes subgoal phenomena from abilities to identify two or more subgoals, the latter based on their accuracy relative to an objective. A priority for future work is to relate how the generic abilities in

Table 1 map onto the goal-specific abilities of solving and planning. More generally, a more inclusive theoretical framework of intelligence will need to incorporate system organization, intrinsic and emergent behavior, and link these to the information dynamics upon which TIS is based.

TIS is unique in taking an eco-evolutionary perspective to intelligence. An eco-evolutionary perspective recognizes that intelligence is not limited to efficiently reducing uncertainty. Addressing complexity could involve tradeoffs. Tradeoffs may emerge as active choices between strategies and/or from system or environmental constraints. For example, agents that seek fast, efficient or optimal solutions to problems may be under time constraints (e.g., escaping a predator), but many scenarios exist in which goal accuracy is important even should extra time be required. In such situations, an agent may sacrifice some efficiency and performance (exploitation) in favor of more exploratory, robust options, requiring for example, flexibility, adaptability and creativity (

Del Giudice and Crespi, 2018).

TIS is grounded in the idea that intelligence is an operator that differentiates, correlates and integrates data, rendering entropy into new information. The outcome differs from the data on which it was derived. Some goals, such as victory in chess resolve existing uncertainty in each move (solving subgoals), generate new uncertainty in some moves, can anticipate future moves (planning across subgoals), and occur in huge but defined spaces leading to one of three finishes (win, draw, lose). Other endeavors such as art occur in subjective spaces and produce novel form (sculpture) or novel observable routes to a finality (cinema). Yet other objectives such as military or political ones may have significant degrees of uncertainty and unpredictable outcomes. These general examples suggest that outcomes and the means to attain them are characteristic of different goal types. All have in common information extraction and processing. Interestingly, the above arguments parallel McShea’s (

McShea, 1996) classification of types of complexity, whereby complexity can be in one or more of process, outcome and/or the levels or hierarchies in each. TIS generalizes previous theoretical treatments (e.g.,

LeCun, 2022,

Chollet, 2019,

LeCun et al., 2015), providing initial steps towards their formalization in information theory (e.g.,

Rivoire and Leibler, 2011,

Adami, 2002,

Tkačik and Bialek, 2016).

Although a dedicated development of how information theory can be integrated into applicable measures of intelligence is left for future study, it is useful to note that regardless of whether estimating solving or planning, goal-useful information (in bits) can be represented as the negative logarithm of the probability that the system arrives to a given result q via solving-planning sequence i from n=1 to N. This can be represented as

which is also a measure of the complexity of the result (

Lloyd and Pagels, 1988). Note that, all else being equal, higher probability trajectories require less information and so are less likely to have value, i.e., intelligence. However, “value” can only be assessed as information relative to a reference, whence have a simple indicator of intelligence

which is the difference in information at a node

n, between the focal system

and the reference

(

Woodward, 1964,

Kharkevich, 1960); for fitness interpretations, see (

Rivoire and Leibler, 2011), (

Adami, 2023). Depending on the interval over

i, (6b) has analogy with indicator (3e). Thus,

I(

n) could be summed over two or more nodes (i.e.,

…) to arrive at indicators of intelligence or measures of complexity. Importantly,

can represent any baseline, for example, random noise, a benchmarked estimate, or the expected (past) ability of the agent. Note that (6b) can take on negative values (i.e., fewer bits than the baseline expectation). The above considerations are, like the previous indicators, massive oversimplifications of how to define or measure intelligence. Quantifying information, its transformations, and goal attainment forming intelligence will be highly challenging, particularly in biological systems (

Rosen, 1986).

TIS posits intelligence as a universal operator of uncertainty reduction in reaction to challenges or directed to attaining goals, producing informational change. This has interesting implications. First, natural and artificial selection are forms of intelligence, since they reduce variation, acquire information about the environment, and increase fitness (e.g.,

Frank, 2012). Inversely, in buffering environmental vagaries, certain intelligent behaviors may reduce natural selection (

Deffner, 2023). Inspired by life history theory (

Stearns, 2000,

Kaplan et al., 2000), selection is expected to act on heritable traits that can affect accuracy and/or efficiency in existing intelligence niches, and traits that affect flexibility, generalization and creativity in new intelligence niches. These either/or expectations of trait evolution will depend to some extent on contexts and tradeoffs (

Del Giudice and Crespi, 2018). Second, organizational change could involve some combination of assembly, disassembly, rearrangement, morphing and recombination. It is an open question as to how information dynamics via these and other modes affects complexity (

Adami, 2002,

Wong et al., 2023). According to TIS, intelligence decreases uncertainty, but it can also transiently increase it (either due to error or counter-intuitive but viable pathways), and intelligence can either increase, decrease or leave unchanged complexity. These observations do not contradict the prediction that intelligence is associated with increased information,

either in the path to a goal

and/or in the goal itself (see also

Adami, 2002). Together with the first implication (natural selection) this is consistent with the idea that the response to selection encodes intelligence into (multi-scale and multi-level) structures and functions. Thus, memory – a key component of intelligence – can be stored in one or more ways: inherited as phenotypes, stored electrochemically as short- or long-term memory, or stored in proxies such as society, collectives, technology, cultural artifacts and constructed niches (

Figure 5). The extent to which contemporary phenotypes and proxies are a compendium of “information past” and “intelligences past” is an interesting open question.

3.2. Characteristics

The framework for TIS is based on concepts, hypotheses and definitions. As such, rigorous testable predictions are not yet possible. Nevertheless, more speculative predictions readily emerge.

SOLVING, PLANNING AND COMPLEXITY. The interrelations between intelligence and complexity are at the foundation of TIS. Specifically, intelligence traits are expected to broadly concord with the complexity of attaining goals relevant to the fitness of the system, i.e., the intelligence niche (

Figure 2). The intelligence niches of any two individuals of the same system type could overlap in some abilities (e.g., musical ability), but possibly not in others (ability to play a specific musical instrument). Capacities are expected to have similar characteristics across niches (e.g., visual acuity in many animal species used both in foraging and avoiding predators), but also specificity in certain niches (ability to climb trees to escape predators). Solving is required for goals of any complexity, whereas only as goals become sufficiently complex relative to the abilities of the system does planning (which minimally entails costs in time and energy) become useful and even necessary (

Figure 3). I predict goal achievement will correlate with solving capacities over sufficiently low complexities, and more strongly with planning abilities over sufficiently high complexities (

Figure 1A,

Figure 3). Although I know of no evaluation of this prediction, the results of Duncan and colleagues (

Duncan et al., 2017) showed that proxy planning (an examiner separating complex problems into multiple parts) equalized performance among human subjects of different abilities.

PROXIES. Proxies are an underappreciated and understudied influence on intelligence and their specific roles in system intelligence remain largely unknown. Proxies such as tools, transportation and AI can function to help solve local, myopic challenges, and in augmenting the system’s own ability to solve, make planning logistically more feasible. Proxies that themselves are able to plan can be important in achieving complex goals out of the reach of individual systems (e.g., human interventions à la (

Duncan et al., 2017). Human social interactions have served this function for millennia and the eventual emergence of AGI could assume part of this capacity (

LeCun, 2022), possibly as proxy collectives (

Duéñez-Guzmán et al., 2023). I also predict that proxies coevolve with their hosts, and insofar as the former increases the robustness of the latter’s capacities, proxies could result in system trait dependence and degeneration of costly, redundant traits (

Edelman and Gally, 2001).

SYSTEM EVOLUTION. In positing that intelligence equates with increased efficiency on familiar goals and more of an emphasis on accuracy for novel goals, TIS provides a framework that can contribute to a greater understanding of system evolution including assembly, growth, diversification and complexity (e.g.,

Stanley and Miikkulainen, 2004,

Wong et al., 2023,

Barrett and Kurzban, 2006,

Tria et al., 2014). Empirical bases for change during lifetimes and through generations include (1) on lifetime scales, intelligence is influenced by sensing and past experience and influences current strategies and future goals (

Klyubin et al., 2005,

Pearl and Mackenzie, 2018), and (2) on multigenerational evolutionary scales, natural selection drives intelligence trait evolution in response to relative performance, needs and opportunities (

Burkart et al., 2017,

Pinker, 2010). There is also theoretical support that systems can evolve or coevolve in complexity with the relevance of environmental challenges (

Adami, 2002,

Klyubin et al., 2005,

Frank, 2009,

Zaman et al., 2014,

Xue et al., 2019). In contrast, excepting for humans and select animals (e.g.,

Li et al., 2004,

Whiten and Van Schaik, 2007), we lack evidence for how intelligence traits actually change during lifetimes given costs, benefits and tradeoffs, and suggest that life-history theory could provide testable predictions (

Stearns, 2000).

NICHE EVOLUTION. Depending on system type, different goals in the intelligence niche might vary relatively little (e.g., prokaryotes) or considerably (e.g., mammals) in complexity. This means that a system with limited capacities will – in the extreme – either need to solve each of a myopic sequence of uncertainties, or use basic, node-adjacent, planning abilities to achieve greater path manageability, efficiency and goal accuracy. Under the reasonable assumption that systems can only persist if a sufficient number of essential (growth, survival, reproduction) goals are attainable, consistent with the “competencies in development” approach (

Flavell, 1979), simple cognitive solving should precede metacognitive planning, both during the initial development of the system and in situations where systems enter new intelligence niches. Moreover, I predict that due to the challenges in accepting and employing proxies, the population distribution of proxy-supported intelligence should be initially positively skewed when a new proxy (e.g., the Internet) is introduced, gradually shifting towards negative skew when the majority of the population has access to, needs, and adopts the innovation (

Rogers, 2014).